Clive Wearing (Amnesia Patient)

Imagine waking up every day without remembering anything from your past and then immediately forgetting that you woke up at all. This life without memories is the reality for British musician Clive Wearing who suffers from one of the most severe case of amnesia ever known.

Who is Clive Wearing?

Clive Wearing was born on 11 May 1938. He was an accomplished musicologist, keyboardist, conductor, music producer, and professional tenor at the Westminster Cathedral. When on 27 March 1985 he contracted a virus that attacked his central nervous system resulting in a brain infection, Clive’s life was changed forever.

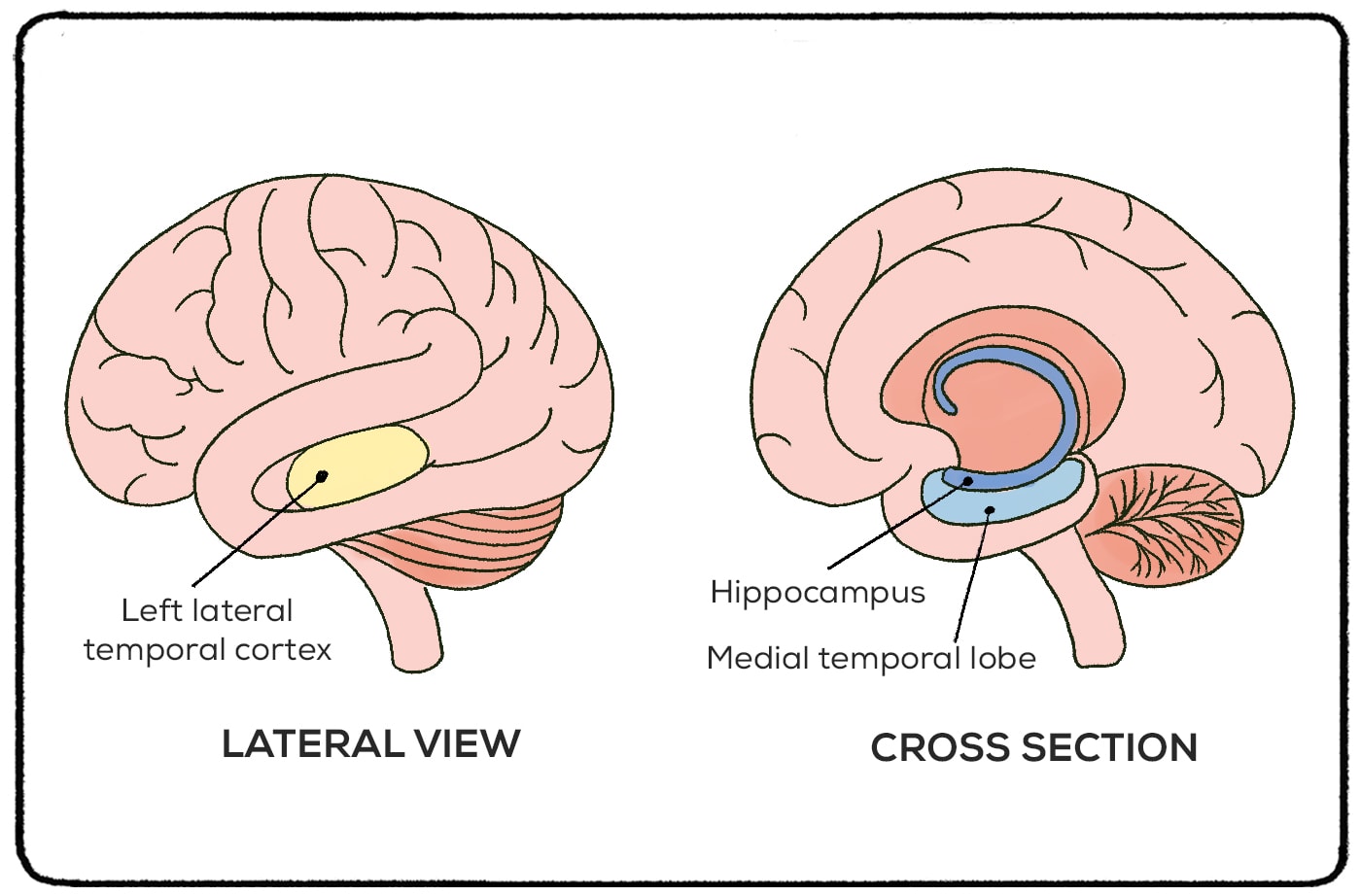

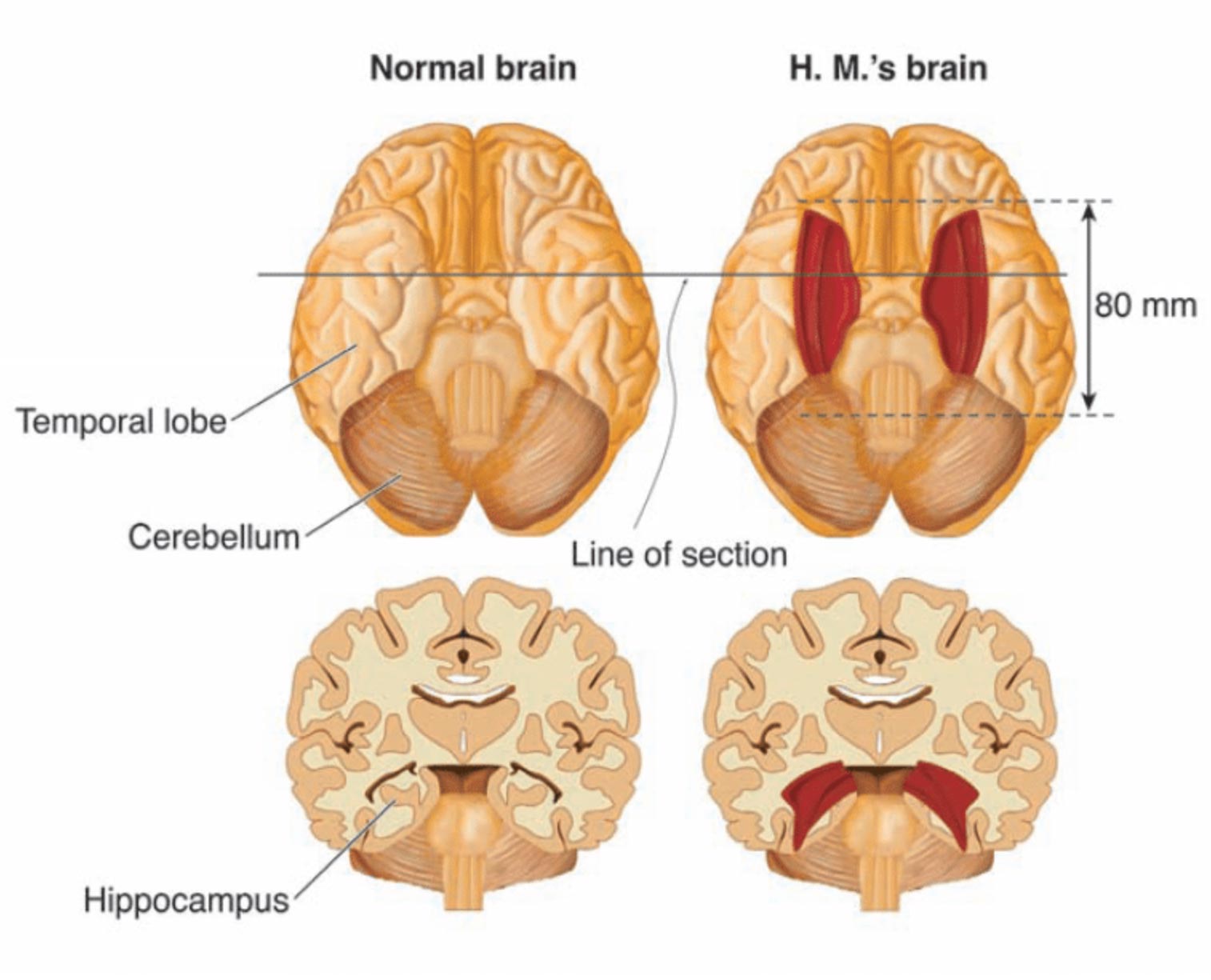

The rare neurological condition called herpes encephalitis caused profound and irreparable damage to Clive’s hippocampus. The hippocampus is a part of the brain that plays an important role in consolidating short-term memory into long-term memory. It is essential for recalling facts and remembering how, where, and when an event happened.

Clive’s hippocampus and medial temporal lobes where it is located were ravaged by the disease. As a consequence, he was left with both anterograde amnesia, the inability to make or keep memories, and retrograde amnesia, the loss of past memories. Most patients suffer one or the other, so it's notable that Clive suffered both.

Clive Wearing and Dual Retrograde-Anterograde Amnesia

Clive’s rare dual retrograde-anterograde amnesia, also known as global or total amnesia, is one of the most extreme cases of memory loss ever recorded. In psychology, the phenomenon is often referred to as "30-second Clive" in reference to Clive Wearing’s case.

Anterograde amnesia

Anterograde amnesia is the loss of the possibility to make new memories after the event that caused the condition, such as an injury or illness. People with anterograde amnesia don’t recall their recent past and are not able to retain any new information. (If you have ever seen the movie 50 First Dates, you might be familiar with this type of condition.)

The duration of Clive’s short-term memory is anywhere between 7 seconds and 30 seconds. He can’t remember what he was doing only a few minutes earlier nor recognize people he had just seen. By the time he gets to the end of a sentence, Clive may have already forgotten what he was talking about. It is impossible for him to watch a movie or read a book since he can’t remember any sentences before the last one.

Because he has no memory of any previous events, Clive constantly thinks that he has just awoken from a coma. In a way, his consciousness is rebooted every 30 seconds. It restarts as soon as the time span of his short-term memory has elapsed.

Retrograde amnesia

Retrograde amnesia is a loss of memory of events that occurred before its onset. Retrograde amnesia is usually gradual and recent memories are more likely to be lost than the older ones .

Due to his severe case of retrograde amnesia, however, Clive doesn’t remember anything that has happened in his entire life. He completely lacks the episodic or autobiographical memory, the memory of his personal experience.

But although he can’t remember them, Clive does know that certain events have occurred in his life. He is aware, for example, that he has children from a previous marriage, even though he doesn’t remember their names or any other detail about them. He knows that he used to be a musician, yet he has no recollection of any part of his career.

Clive also knows that he has a wife. In fact, his second wife Deborah is the only person he recognizes. Whenever Deborah enters the room, Clive greets her with great joy and affection. He has no episodic memories of Deborah, and no memory of their life together. For him, each meeting with her is the first one. But he knows that she is his wife and that he is happy to see her. His memory of emotions associated with Deborah provokes his reactions even in the absence of the episodic memory.

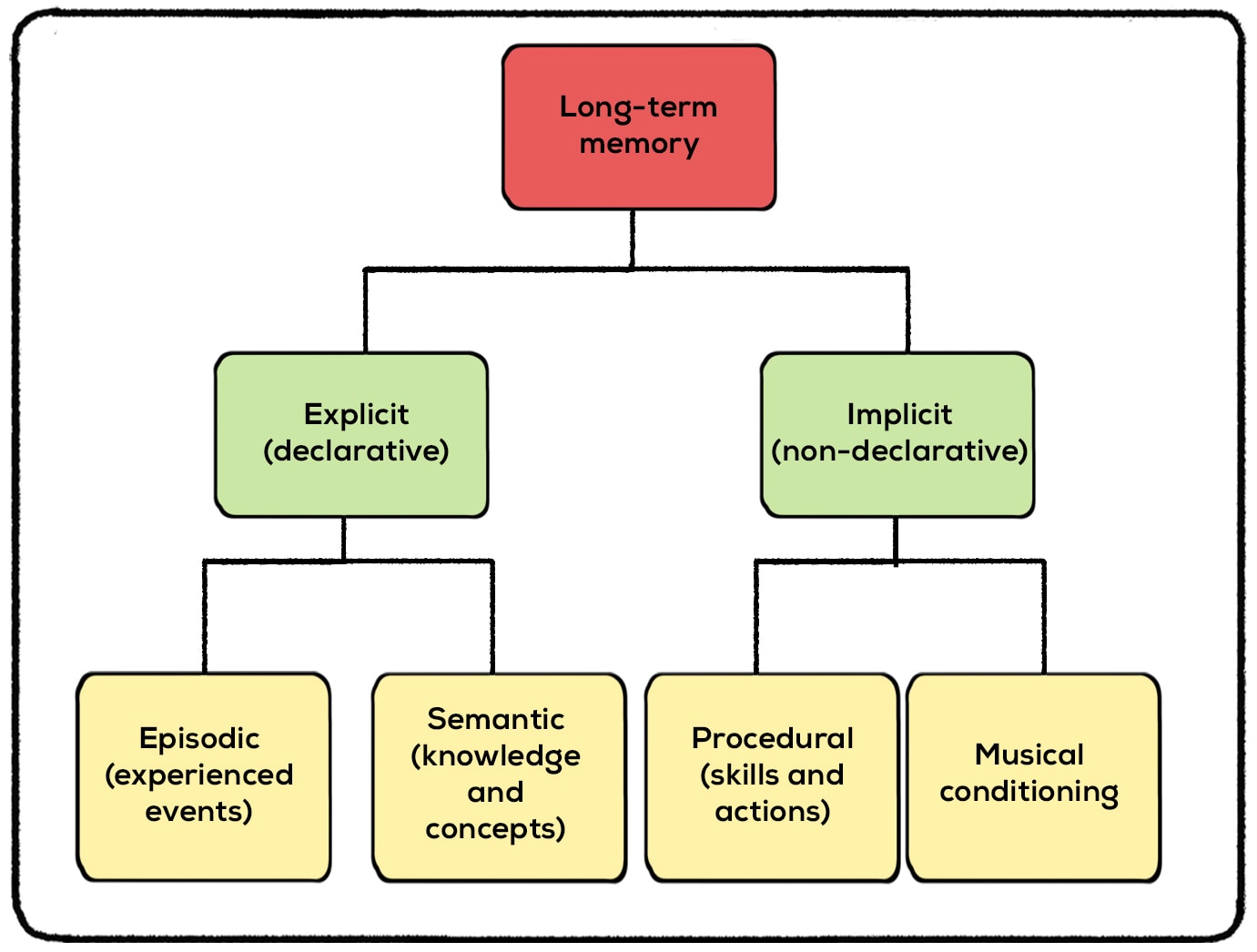

In spite of his complex amnesia, Clive still has some types of memories that remain intact, including semantic and procedural memory.

Clive Wearing’s Semantic and Procedural Memories

Clive Wearing’s example shows that memory is not as simple as we might think. Although the physical location of memory remains largely unknown, scientists believe that different types of memories are stored in neural networks in various parts of the brain.

Semantic memory

Semantic memory is our general factual knowledge, like knowing the capital of France, or the months of the year. Studies show that retrieving episodic and semantic memories activate different areas of the brain. Despite his amnesia, therefore, Clive still has much of his semantic memory and retains his humor and intelligence.

Procedural memory

Clive may not have any episodic memories of his life before the illness, but he has a largely unimpaired procedural memory and some residual learning capacity.

Procedural or muscle memory is remembering how to perform everyday actions like tying shoelaces, writing, or using a knife and fork. People can retain procedural memories even after they have forgotten being taught how to do them. This is why Clive’s procedure memory including language abilities and performing motor tasks that he learned prior to his brain damage are unchanged.

Using procedural memory, Clive can learn new skills and facts through repetition. If he hears a piece of information repeated over and over again, he can eventually retain it although he doesn’t know when or where he had heard it.

While episodic memory is mainly encoded in the hippocampus, the encoding of the procedural memory takes place in different brain areas and in particular the cerebellum, which in Clive’s case has not been damaged.

Musical memory

What’s more, Clive’s musical memory has been perfectly preserved even decades after the onset of his amnesia. In fact, people who suffer from amnesia often have exceptional musical memories. Research shows that these memories are stored in a part of the brain separate from the regions involved in long-term memory.

That’s why Clive is capable of reading music, playing complex piano and organ pieces, and even conducting a choir. But just minutes after the performance, he has no more recollection of ever having played an instrument or having any musical knowledge at all.

Is Clive Wearing Still Alive?

Yes! Clive Wearing is in his early 80s and lives in a residential care facility. Recent reports show that he continues to approve. He renewed his vows with his wife in 2002, and his wife wrote a memoir about her experiences with him.

You can take a look at Clive Wearing's diary entry, as well as access a documentary on him, by checking out this Reddit post .

Not Just Clive Wearing: Other Cases of Amnesia

Clive Wearing is one of the most famous patients with amnesia, but he is far from the only one. Amnesia can affect people temporarily or permanently, and it doesn’t discriminate. Famous authors, former NFL players, and just regular people going to the dentist may deal with a bout of amnesia at one point in their lives. And some of these stories are so stranger than fiction that they are doubted by medical professionals and the general public!

Neuroscientists have been carefully studying amnesia since the 1950s. One of their first notable patients was a man named Henry Molaison, or “H.M.” H.M. suffered amnesia after having surgery at the age of 27. H.M. forgot things almost as soon as they took place. His condition was the subject of studies for decades until he died in 2008. Many scientists still refer to his case when discussing amnesia and other memory disorders.

Scott Bolzan

Imagine waking up one day in the hospital with little to no memories of your life. You’re 47, the woman by your bedside is telling you that you have been married for 25 years. The terms “marriage” and “wife” don’t even register in your brain! As your family tells you about your life, you learn that you spent two years playing in the NFL, have two teenage children, and have decades of memories that just aren’t accessible. This is what happened to Scott Bolzan.

Scott Bolzan developed retrograde amnesia after a simple slip and fall. Little to no blood flow and damaged brain cells in the right temporal lobe erased many of Bolzan’s long-term memories. He knew basic skills, like eating with utensils, but memories of people and events completely disappeared. His case is one of the most severe cases of retrograde amnesia in history, but even his story is doubted by some neurologists. Since his fall, he has written a book about his memory loss and is now a motivational speaker.

Agatha Christie

The story of Agatha Christie’s amnesia is largely buried under her other accomplishments. She’s one of the world’s best-selling authors (only outsold by the Bible and Shakespeare!) Her brain was always in use as she wrote 66 detective novels, but before that, she may have suffered great memory loss. Did she have total amnesia? The jury is actually out on that. I’ll explain why.

Christie found out that her husband was cheating on her shortly after the death of Christie’s mother. The stress was tough for Christie to handle, so it’s not surprising that she fled home after an argument with her husband. Her car turned up in a ditch, and after 11 days of searching, she was found at a hotel. Christie had checked into the hotel using the same name as the “other woman” in her husband’s affair.

Upon discovering Christie, her husband reported that she was suffering from amnesia and had no idea who she was. Two doctors confirmed the diagnosis, but it did not debilitate her for life, like Clive Wearing. This alleged bout with amnesia happened in 1926, years before she wrote the genius novels that we still know today. Some sources are not sure whether she suffered amnesia, was faking the condition to seek revenge on her husband or was simply experiencing a dissociative state after traumatic events. It would not be completely unusual if she did experience memory loss while staying in that hotel. Dissociative amnesia can affect anyone who has been through trauma or extreme levels of stress.

One patient, identified only as “ WO ,” started living the life of Drew Barrymore’s character in 50 First Dates after a…root canal? While anterograde amnesia was the result of a car crash in the popular movie, other types of trauma or events can bring on this condition. For WO, it was a routine root canal. Nothing dramatic happened during the procedure. Nothing dramatic took place in WO’s brain after they went home. And yet, the patient wakes up every day believing it is March 14, 2005. They were 38 years old at the time of the root canal.

Every day, the patient must wake up and remind themselves that it is not 2005, but much later. An electronic journal keeps them up to date with their life and the events of the past years. Although the cause behind their amnesia is truly baffling, it goes to show that our brains can be fragile and there is still a lot to learn about them!

Related posts:

- Long Term Memory

- Semantic Memory (Definition + Examples + Pics)

- Memory (Types + Models + Overview)

- Short Term Memory

- Declarative Memory (Definition + Examples)

Reference this article:

About The Author

Free Personality Test

Free Memory Test

Free IQ Test

PracticalPie.com is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

Follow Us On:

Youtube Facebook Instagram X/Twitter

Psychology Resources

Developmental

Personality

Relationships

Psychologists

Serial Killers

Psychology Tests

Personality Quiz

Memory Test

Depression test

Type A/B Personality Test

© PracticalPsychology. All rights reserved

Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

- Abnormal Psychology

- Assessment (IB)

- Biological Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminology

- Developmental Psychology

- Extended Essay

- General Interest

- Health Psychology

- Human Relationships

- IB Psychology

- IB Psychology HL Extensions

- Internal Assessment (IB)

- Love and Marriage

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

- Prejudice and Discrimination

- Qualitative Research Methods

- Research Methodology

- Revision and Exam Preparation

- Social and Cultural Psychology

- Studies and Theories

- Teaching Ideas

If you’re interested: Clive Wearing

Travis Dixon September 26, 2017 Cognitive Psychology

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

There’s never enough time to cover everything in our IB Psychology course, so here are a few resources that might not fit in normal classes, but you might find interesting nonetheless.

Clive Wearing is very similar to the famous case of HM (Henry Molaison). However, whereas HM’s hippocampus was damaged due to surgery, Wearing’s was damaged due to an illness. The results were similar though: Wearing has no short-term memory but his procedural memory remains in-tact.

You can learn more about Mr Wearing by watching the following video from 44:02-57:40.

There are no documentaries (that I’m aware of) that feature filmed footage of HM. Wearing, on the other hand, has been the subject of multiple documentaries. This is perhaps due to the fact that his wife is able to sign consent forms to appear in such films, whereas HM was never married.

Here is another documentary on Clive Wearing from 1986:

This article in the New Yorker called “The Abyss” also explores the case of Wearing.

Deborah Wearing also wrote a book about her and Clive’s experiences, called “Forever Today,” which is available on Amazon.

A Word of Warning about Wearing

You might be tempted to use details of Clive Wearing’s case in an exam, just as you would HM’s. However, you need to be careful. The above documentaries are not peer-reviewed academic literature, so we need to be wary of basing our conclusions on this evidence. I would recommend using details of HM’s case study (Milner, 1957 and Corkin, 1997) in IB exam answers.

Travis Dixon is an IB Psychology teacher, author, workshop leader, examiner and IA moderator.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Musical memory in a patient with severe anterograde amnesia

Sara cavaco.

1 Division of Behavioral Neurology and Cognitive Neuroscience, University of Iowa, USA

2 Laboratory of Neurobiology of Human Behavior, Centro Hospitalar do Porto, Portugal

Justin S. Feinstein

4 Department of Psychology, University of Iowa

Henk van Twillert

3 Escola Superior de Música e das Artes do Espectáculo do Porto, Portugal

Daniel Tranel

The ability to play a musical instrument represents a unique procedural skill that can be remarkably resilient to disruptions in declarative memory. For example, musicians with severe anterograde amnesia have demonstrated preserved ability to play musical instruments. However, the question of whether amnesic musicians can learn how to play new musical material despite severe memory impairment has not been thoroughly investigated. We capitalized on a rare opportunity to address this question. Patient SZ, an amateur musician (tenor saxophone), has extensive bilateral damage to his medial temporal lobes following herpes simplex encephalitis, resulting in a severe anterograde amnesia. We tested SZ’s capacity to learn new unfamiliar songs by sight-reading following three months of biweekly practices. Performances were recorded and then evaluated by a professional saxophonist. SZ demonstrated significant improvement in his ability to read and play new music, despite his inability to recognize any of the songs at a declarative level. The results suggest that it is possible to learn certain aspects of new music without the assistance of declarative memory.

Introduction

Patients with dense amnesia due to bilateral medial temporal lobe damage ( Wilson, Baddeley, & Kapur, 1995 ; Anderson et al., 2007 ) or due to dementia of the Alzheimer’s type ( Schacter, 1983 ; Beatty et al., 1988 , 1994 , 1999 ; Crystal, Grober & Masur, 1989 ; Cowles et al., 2003 ; Fornazzari et al., 2006 ; for a review see Baird & Samson, 2009 ) have demonstrated a remarkable ability to continue to perform certain types of activities that they learned prior to brain injury (e.g., driving, playing a musical instrument, and playing golf). The ability to learn and retain new perceptual or motor skills (e.g., rotary pursuit, mirror-tracing, and mirror-reading) and the ability to learn new habits (e.g., probabilistic-learning) are also known to be intact in amnesic patients (e.g., Milner, 1962 ; Cohen & Squire, 1980 ; Gabrieli, Corkin, Mickel, & Growdon, 1993 ; Tranel, Damasio, Damasio, & Brandt, 1994 ; Hay, Moscovitch & Levine, 2002 ; Cavaco, Anderson, Allen, Castro-Caldas & Damasio, 2004 ). Cohen and Squire (1980) found that amnesic patients were able to acquire the mirror reading skill at a normal rate despite poor memory for the words that they had read. This dissociation led these authors to distinguish between declarative forms of memory (dependent on the medial temporal lobe system), and procedural, nondeclarative forms of knowledge which are often spared in amnesic patients. Declarative memory refers to the capacity for conscious recollection about facts and events, whereas nondeclarative memory is expressed through performance rather than recollection ( Squire, 2004 ). Nondeclarative memory includes different forms of learning and memory abilities, including the perceptual and motor skills involved in musical performance. Even though some aspects of the musical performance can be declared, the actual skills are often carried into action without conscious retrieval of information regarding the procedural aspects of music.

Understanding how the brain processes music and how music can help neurological patients heal and overcome adversity is a rapidly growing field of study ( Levitin, 2007 ; Sacks, 2008 ). A series of case reports have described patients with significant declarative memory impairments who can still play musical instruments somewhat skillfully ( Beatty et al., 1988 , 1994 , 1999 ; Crystal et al., 1989 ; Wilson et al., 1995 ; Beatty, Brumback, & Vonsattel, 1997 ; Baur, Uttner, Ilmberger, Fesl & Mai, 2000 ; Cowles et al., 2003 ; Fornazzari et al., 2006 ). All of these reports describe instances of amnesic musicians who are able to perform songs that they had learned how to play prior to the onset of their amnesia. Perhaps the most well-known of these cases is Clive Wearing, a renowned musicologist with severe amnesia after sustaining bilateral medial temporal lobe damage due to herpes simplex encephalitis ( Wilson et al., 1995 ). According to the authors, Clive demonstrated an intact ability to “sight-read, obey repeat marks within a short page, and understand the significance of a metronome mark… ornament, play from a figured bass, transpose, and extemporize.” This description of Clive’s musical skills was the first non-neurodegenerative evidence of relatively preserved ability to perform a musical instrument despite severe multi-modal declarative memory impairment. It is currently unknown, however, whether or not Clive is able to learn how to play new songs.

Two early case reports described attempts to teach unfamiliar songs to piano players with dementia of the Alzheimer’s type; one by sight-reading ( Beatty et al., 1988 ) and the other by ear ( Beatty et al., 1999 ). Even though both patients were able to play familiar songs that had been learned premorbidly, their ability to learn a new composition was rather limited. However, the patients’ significant non-amnestic cognitive impairments may have hampered their ability to engage with the training process. Cowles and colleagues (2003) later described the case of a moderately demented patient with probable Alzheimer’s disease who was able to play a new song on the violin and demonstrated some limited capacity to play parts of the song by request (i.e., playing without sheet music) at delays of 0 and 10 minutes. The attempts to cue the patient’s performance by providing the first measures of the new song were found unsuccessful. Fornazzari and colleagues (2006) assessed the ability of a professional pianist with probable Alzheimer’s disease to learn unfamiliar musical pieces and observed “gradual improvements in overall performance and in rhythm, field elements, harmony, melodic accuracy, and sophistication in the accompaniment of the left hand” over a seven day period. However, the authors did not provide any quantification of the improvements. Baur and colleagues (2000) described a herpes simplex encephalitis patient (CH) who learned how to play the accordion, autodidactically, after the onset of her amnesia. Patient CH did not have any premorbid sight-reading training nor did she have any experience of playing a musical instrument. Yet, remarkably, she was able to learn how to play 90 pieces of Austrian and German folk music after listening to the songs on the radio or on tape. Moreover, she was able to play a song when cued with the song title, and she was also able to provide the song title when cued with a recording of the music. This suggests that CH had preserved declarative memory for the music, despite her overall poor performance on a battery of standardized memory tests. Thus, at least some of CH’s intact ability to learn new music could be explained by her reservoir of preserved declarative memory for music. Taken together, the results of the five aforementioned case studies are mixed. Two of the Alzheimer’s patients were unable to learn new music, whereas two other Alzheimer’s patients showed some residual learning. In addition, the findings in encephalitic patient CH are confounded by the patient’s ability to learn new declarative information about music.

To date, then, available research does not provide a definitive conclusion about whether the ability to learn and play unfamiliar music can be preserved in the context of a severe impairment in declarative memory. Here, we explored the capacity of an amateur musician, who had dense multi-modal anterograde amnesia, to perform and learn a series of new songs after three months of intense practice.

Patient SZ is a 51-year-old, fully left-handed man (-100 on the modified Geschwind-Oldfield Handedness Questionnaire) with 16 years of education and a bachelor’s degree in engineering. He had a normal developmental history and no neurologic problems until developing herpes simplex encephalitis at age 42. SZ’s MRI scans reveal large bilateral lesions affecting the hippocampus, amygdala, temporal poles, and insular cortices ( Figure 1 ). The damage is more extensive in the left hemisphere, completely destroying the hippocampus, amygdala, temporal pole, adjacent sectors of the anterior temporal lobe, and most of the insular cortex, especially the anterior portion. In addition, the left hemisphere damage extends anteriorly into the basal forebrain and posterior surface of the orbitofrontal cortex. In the right hemisphere, the damage is not as severe and is largely circumscribed to the medial temporal lobe, medial temporal pole, and insular cortex.

Lateral views of the left hemisphere (left) and right hemisphere (right) are shown in the upper section of the figure, and axial (A–C, middle row) and coronal (D–E, bottom row) slices are shown below. (A) Axial slice depicting bilateral damage to the medial temporal lobe, medial temporal poles, and unilateral damage to a large region of the left temporal lobe. (B & C) Axial slices depicting bilateral damage to the insular cortex and left-sided damage to the basal forebrain and posterior orbitofrontal cortex. (D) Coronal slice depicting bilateral damage to the temporal poles (with only the medial temporal pole affected on the right side), and unilateral damage in the region of the left basal forebrain. (E) Coronal slice depicting bilateral damage to the amygdala and insula, and unilateral damage to a large region of the left temporal lobe. (F) Coronal slice depicting bilateral hippocampal damage and some damage to the left temporal cortices and left posterior insula. All images use radiological convention (i.e., right side of image = left hemisphere and vice versa).

On the neuropsychological evaluation ( Tranel, 2009 ), SZ revealed a profound anterograde amnesia ( Table 1 ). He was unable to recall or recognize any declarative information, verbal or visual, even after repeated presentations. Despite his severe declarative memory impairment, SZ has shown relatively preserved premorbid driving abilities (participant #2 in Anderson et al., 2007 ) and has demonstrated normal ability to acquire and retain a series of new perceptual-motor skills (subject #2 in Cavaco et al., 2004 ), suggesting intact procedural memory. Likewise, he also demonstrated intact performances on measures of working memory. His overall general intellectual functioning falls in the low average range, somewhat below expectations given his educational background. Some of his IQ scores were artificially reduced by his inability to remember the task instructions and his slowed processing speed. However, when examining specific measures that are known to be good indicators of premorbid intellectual functioning (e.g., reading ability, vocabulary, similarities, and matrix reasoning) his scores are in the average to above average range, well within normal expectations. His block design score and arithmetic achievement score are below expectations given his engineering background, a finding which might be partially related to the time constraint imposed by both tests that negatively affected his performance due to his slowed processing speed and poor memory for the task instructions. SZ’s basic language functioning, including naming and comprehension, is preserved (likely due to his left-handedness) despite extensive damage to critical language areas in the left hemisphere. His speech is fluent, well-articulated, and nonparaphasic, with normal rate, volume, and prosody. He does have a tendency to perseverate during conversations, often times repeating the same phrases multiple times. Additionally, he performed poorly on a test of verbal associative fluency. His basic visuospatial, visuoperceptual, and visuoconstructional abilities are mostly intact, although, once again, his slowed processing speed and tendency to forget task instructions at times adversely affected his test performance. He reported no signs of any depression or anxiety. He displayed a normal range of affect, including laughter and irritability. His anger is usually triggered by situations where he feels his independence is being hindered or his intelligence is being questioned. SZ displays a profound lack of awareness for his memory impairment (i.e., anosognosia), and will typically deny having any problems, or even weaknesses, in the domain of memory.

Neuropsychological evaluation

Scores are presented in standard/scaled scores (*) or as raw scores (**). The WAIS-III subtest scores are age-corrected scaled scores. The z-scores were calculated with reference to demographically matched normative samples ( Tranel, 2009 ). Results that are below expectations or that are defective in comparison to demographically matched normative samples are marked with an X (i.e., scores greater than 2 standard deviations from the normative mean).

Musical experience

SZ received musical training on his saxophone between the ages of 12 and 18. In high school, SZ played in a jazz band that at one time competed at the national level and won the second place prize. After graduating from high school, he stopped playing the saxophone and did not resume playing until three years after his brain injury (i.e., over 27 years later). Both of SZ’s parents stated that they were impressed with how seamlessly he was able to play the saxophone again after such a long hiatus. For the past six years, SZ has been playing in an amateur orchestra. The conductor considers him an average saxophonist, rating him a 5 on a 10 point scale when compared to the other members of the orchestra (all of whom are healthy and without any notable memory problems or brain damage). According to the conductor, SZ is a good sight-reader and his main difficulties are maintaining a consistent tempo and staying in time with the band. The conductor stated that while most members of the orchestra tend to fall behind when playing, SZ tends to play too fast. Additionally, SZ will often skip repeat signs while reading sheet music. Consequently, no one has ever observed SZ enter into a never-ending loop, where he would continuously repeat a section of a song, forgetting each time that he had already repeated that same section. In order to reduce his rapid playing tempo and make sure he properly follows repeat signs, SZ’s mother accompanies him to all practices and concerts, and helps him follow along on the sheet music. An interesting feature of SZ’s personality and playing style is that he will only play music on his saxophone when provided with sheet music. He claims that he is unable to “play by ear” and consistently refuses any request to improvise a song or complete a song when cued or primed with the beginning notes. The one exception to this rule is his warm-up song, “Windy”, which he knows by heart and will routinely and spontaneously play without any sheet music. Of note, this song was written in 1967 by The Associations, over three decades before the onset of his brain injury.

In terms of music preferences, SZ stated that he likes “all styles” of music and has no particular preference. He often says, “music is the universal language… for children of all ages.” Interestingly, since his brain injury, music has become part of his identity. When asked about his dream job, he replied that he would like to be “a professional musician.” Moreover, he has stated that “music is empowering” and brings him immense joy in life. Both of his parents agree with this sentiment and have observed that music has a calming effect on SZ’s mood and has helped reduce occurrences of agitation and irritability.

Several anecdotes vividly illustrate the severity of SZ’s memory impairment while playing music. One example occurred at the end of a concert that SZ and his orchestra performed in front of an audience of approximately 500 people. A few minutes after the show was over, the audience congregated in the concert hall’s main entrance, waiting for the musicians to join them for a post-concert celebratory reception. One of the study’s co-investigators (J.S.F) approached SZ and inquired about when the concert would start. SZ, completely unaware that he and his orchestra had just finished performing a nearly 2-hour long concert, replied, “I think we’ll probably start here in a few minutes.” In a previous unpublished experiment, SZ was asked to play the song, “You Raise Me Up” (as performed by Josh Groban) eight consecutive times in a 22-minute period, taking a 30–60 second break in between each rendition. At the beginning and end of each of the 8 trials, SZ was asked whether he recognized the song and whether he had played the song before. In all cases, he denied having seen or played the song before. His amnesia was so dense that he would forget having played the song within a mere 30 seconds of completion. Of note, the song “You Raise Me Up” was written after the onset of his amnesia. This particular version was contained on one page of sheet music and could be played in approximately two minutes. Thus, even with a massive amount of exposure over a short period of time, SZ was unable to remember the music.

Informed written consent was obtained from SZ and his family prior to participating in the study. The University of Iowa Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures. The conductor of SZ’s orchestra provided us with the sheet music (11 songs in total) that the orchestra would be learning once they returned from a holiday period. These 11 songs comprised our target condition. Based on his parents report, SZ had never seen nor played any of the target songs at anytime in his life. We also included sheet music for 5 control songs, all of which were only played during the testing sessions (i.e., he never practiced or played these songs in-between testing sessions). Blinded to the stimulus condition, the expert rater (author H.v.T.) classified the songs from 1 to 10, according to its level of difficulty for an amateur musician ( Table 2 ).

Play list and assessment results comparing change from Time 1 to Time 2

Assessment results (−) Time 2 < Time 1; (+) Time 2 > Time 1; (=) Time 2 = Time 1.

SZ’s musical performances were recorded during two separate testing sessions (time 1 and time 2) separated by 100 days. Time 1 occurred one week before the orchestra started rehearsing. Time 2 occurred after three months of continuous rehearsals during which the orchestra met twice a week for at least one hour per rehearsal. In total, SZ practiced the target songs for at least 30 hours between time 1 and time 2. During each testing session, SZ performed 16 different songs in a room by himself (i.e., without the orchestra). All songs were played by sight-reading using sheet music. The songs were presented in the same order each time (see Table 2 ). At the beginning of each song, the examiner presented SZ with the sheet music and asked him whether he recognized the name of the song and whether he remembered having played the song before. SZ then proceeded to play the song using a tenor saxophone (key of B b ). All performances were recorded using a digital audio recorder.

Each song was judged by a professional saxophonist (author H.v.T.; http://www.saxunlimited.com ) who was blinded to both the song order (i.e., before versus after three months of practice) and type of song (i.e., target versus control song). SZ’s performances at time 1 and time 2 were rated on five different measures (intonation, sound quality, rhythmic awareness, notes awareness, and overall sight-reading accuracy). All ratings were provided on a 10-point scale with 0 being extremely poor performance and 10 being an adequate performance for an amateur musician. Intonation corresponds to the pitch accuracy between played intervals (with A=440Hz as reference). Sound quality depends on the flow of air and the pressure on the mouthpiece. Rhythmic awareness refers to the correct identification of the notated rhythm and the immediate correction when the duration of sound does not correspond to what is expected. Notes awareness refers to the correct identification of the written notes and the immediate correction when the sound does not correspond to what is expected based on the sheet music. The overall sight-reading accuracy refers to compliance with the sheet music instructions regarding: notes, rhythm, and tempo (e.g., Adagio-slow, Allegro-fast, Presto-very fast), dynamics (e.g., PP-very soft, FF-very loud, crescendo-get gradually louder, decrescendo-get gradually softer), and repeat signs.

Declarative memory

SZ did not recognize any of the target or control songs at time 1 or time 2. In all cases, he completely denied having any memory or recognition for the song. The one exception was target song #7, “If Thou Be Near” by Bach. In both testing sessions, he recognized the name Bach on the sheet music and claimed that he “thinks” he has played the song before. As previously stated, both of his parents claim that he never played any of the target songs prior to Time 1. Therefore, we believe that his claim for recognizing this particular song is purely due to his recognition of the composer.

Musical performance

The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the performance on the target songs and the control songs at time 1 (i.e., before he had any practice playing the target songs). No significant differences (p>0.05) were found on any of the five measures ( Figure 2 ). Additionally, there were no significant differences (Mann-Whitney U=27; p=0.954) on the level of difficulty between the target (median=4; mean rank=8.5) and the control (median=4.5; mean rank=8.6) songs ( Table 2 ).

The results are presented as median scores. The error bars represent the range between minimum and maximum scores. Time 1 corresponds to dark grey bars and Time 2 to the light grey bars. No significant differences were found between target and control songs at Time 1 on any of the measures. SZ’s performance improved significantly on the target songs from Time 1 to Time 2, as measured by Notes Awareness and Overall Sight-Reading Accuracy indices. His performance on the control songs did not change significantly from Time 1 to Time 2.

SZ demonstrated improvement from Time 1 to Time 2 on notes awareness (for 7/11 target songs) and overall sight-reading accuracy (for 6/11 target songs), and neither of these measures showed any decline over time for any of the target songs (see Table 2 for a song by song breakdown). Positive changes over time were also found on intonation (1/11), sound quality (3/11), and rhythmic awareness (6/11). For the control songs, positive changes over time were found on notes awareness (for 4/5 control songs), overall sight reading accuracy (2/5), intonation (1/5), sound quality (1/5), and rhythmic awareness (1/5).

The Wilcoxon test for paired samples was applied to compare the expert’s scoring of each song at time 1 and time 2. According to the professional musician’s evaluation, after three months of intense exposure to the music during biweekly orchestra practices, patient SZ demonstrated significant improvement on the performance of the target songs, as measured by notes awareness (median=7 at Time 1 and median=9 at Time 2; mean of the negative ranks=0; mean of the positive ranks=4; Z=−2.414, p=0.016, r =−0.51) and overall sight-reading accuracy (median=7 at Time 1 and median=8 at Time 2; mean of the negative ranks=0; mean of the positive ranks=3.5; Z=−2.214, p=0.027, r =−0.47;) ( Figure 2 and Table 2 ). No significant improvements were found on the other measures (i.e., intonation, sound quality, and rhythm awareness).

The comparisons between time 1 and time 2 for the control songs did not reveal any significant changes. For three indices (intonation, sound quality, rhythmic awareness), his performance on the control songs was numerically lower at Time 2; this never occurred on the target songs. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the level of difficulty of the songs that showed improvement versus those that did not. No significant difference (p>0.05) was found.

Patient SZ showed significant improvement when learning a series of new unfamiliar songs over a three-month period of intensive training despite his complete inability to consciously remember having played any of the music. The learning was confined to measures tapping into perceptual-motor aspects of saxophone playing, including notes awareness and sight-reading accuracy. In essence, he demonstrated content specific sight-reading improvements such that his ability to read musical notations on sheet music and translate these notations into movements became more accurate for the practiced songs.

Different brain regions have been shown to play a role in the perceptual-motor aspects of music. For example, playing a musical instrument by sight-reading has been found to activate the superior parietal cortex, bilaterally, both in professional musicians ( Sergent, Zuck, Terriah & MacDonald, 1992 ) and in musically-naive individuals after training ( Stewart et al., 2003 ). The basal ganglia and the cerebellum have been found to be engaged in the performance of a memorized musical composition by blindfolded pianists ( Parsons , Sergent, Hodges, & Fox, 2005 ). Human lesion studies have also implicated these brain regions in the acquisition of new perceptual and motor skills (e.g., Laforce & Doyon, 2001 ; Cavaco et al., 2011 ). High-resolution MRI images clearly indicate that the superior parietal cortex, the basal ganglia, and the cerebellum are not damaged in SZ, and thus, may be contributing to his improved musical performance on perceptual-motor aspects of learning.

While SZ demonstrated significant learning on perceptual-motor aspects of music, the effect was modest in size. The professional musician that scored his performance speculated that most of his students would have shown a much greater improvement (compared to SZ) if they had repeatedly practiced the material over a three month time period. However, the present study was not designed to ascertain whether the magnitude of SZ’s learning was within or below the “normal” range. The normality of learning, vis-à-vis whether a patient with severe anterograde amnesia is capable of learning to perform new music at a normal rate, is a completely separate issue from whether any new musical learning can take place in such a patient. The absence of a healthy “control” group narrows the scope of the discussion, but does not compromise the main finding — the contrast between SZ’s learning to play new music, and his inability to remember the music at a declarative level is clear and robust.

The assessment of SZ’s learning may have been altered due to the testing environment, which differed substantially from his practice environment with his orchestra. Since on both testing sessions SZ played the saxophone by himself, it is unclear whether his performance would be enhanced when playing with the full orchestra. Notably, the training of the target songs was accomplished in the context of orchestra practice. During this training, SZ received extra visual and auditory cues from the conductor, his mother, and the other musicians in the orchestra. These immediate external references may have facilitated better pitch correction and rhythmic awareness, and this is certainly something that can be tested in a future study. Non-declarative knowledge has been suggested to be essentially inflexible and non-relational, and the expression of this type of memory is potentiated when the conditions at the assessment mirror the original learning conditions ( Cohen, Poldrack & Eichenbaum, 1997 ). Additionally, SZ’s training process did not avoid the occurrence of errors. Error elimination is known to be particularly problematic in amnesic patients ( Baddeley & Wilson, 1994 ). In the absence of declarative (explicit) recollection of prior training experiences, an amnesic patient tends to make the same errors over and over. It is reasonable to speculate that a longer training period, individually tailored and based on an errorless approach, would have produced better learning results in SZ.

The piecemeal improvement in SZ’s musical memory is likely to reflect the complexity of cognitive processes necessary to learn a new musical piece. The acquisition, integration, and retrieval of both declarative and non-declarative knowledge are all part of the musical learning process. Healthy musicians benefit from the conscious recollection of prior exposure to a particular song. With repeated exposure, a normal musician tends not to read all the written information on a piece of sheet music, but rather, develops a “feel” for the song’s progression and over time develops a “muscle memory” for the song itself. This combination of declarative and procedural learning may contribute to more efficient eye-hand spans (i.e., the separation between eye position and hand position when sight-reading music; Furneaux & Land, 1999 ), and subsequently to better and smoother performances.

SZ did not show significant improvement on some of the indices, namely sound quality, intonation, and rhythmic awareness. The sound quality of a musician is a relatively stable non-declarative skill, i.e., it is less dependent on content specific training than all the other measures and significant changes are more likely to require extensive training. Intonation and rhythmic awareness are partially related to a musician’s ability to convey the emotional undertone or “prosody” of the song’s melody in such a manner that the timing and inflection of each note seamlessly merges with the subsequent note, creating a coherent musical piece that conveys a distinct “feeling.” When SZ’s music recordings were played to professional and amateur musicians, those listeners commented that the sound was somewhat “robotic” or “machine-like” in nature. SZ’s basic perception of music and his processing of emotions in musical stimuli were not explored. Likewise, we did not specifically measure whether SZ’s saxophone playing is generally “flat” with regard to emotion for all music that he plays. However, there are indications that he is able to convey at least some emotion while playing the saxophone. During his warm-up song, “Windy,” the sound was much more vibrant and filled with emotion. Likewise, during testing, all measures were above the floor (see Figure 2 ) suggesting that at least some aspects of emotion were present when he played the saxophone. Future studies examining the learning of new musical material in amnesic patients could consider using experimental designs with similar assessment and training conditions, multiple expert raters, and the inclusion of foil excerpts for the raters (i.e., clips played by different musicians interspersed with those played by the patient).

In summary, the ability to play a musical instrument represents a unique procedural skill that appears to be resilient to disruption of declarative memory. Previous studies have not answered definitively the question of whether amnesic musicians are capable of learning new music. The present study capitalized on a rare opportunity to address this issue by exploring the capacity to learn new songs in an amateur musician with severe non-progressive anterograde memory impairment. The patient’s performance, before and after three months of prolonged exposure and practice, highlighted the distinction between some preserved capacity to acquire non-declarative memories for new musical material and the complete inability to learn any declarative information about the songs. The magnitude of this new learning was relatively modest and appeared to be confined to the perceptual-motor aspects of playing new music.

Acknowledgments

We are greatly indebted to SZ and his family for their unwavering support and continued commitment to brain research. We also would like to thank SZ’s caregivers and his orchestra for allowing us to observe. Nicolau Pinto Coelho, Mikiko Kanemitsu, Gilberto Bernardes, and Fernando Ramos provided important musical expertise, Kenneth Manzel contributed with the neuropsychological evaluation, and Steven W. Anderson provided invaluable comments on earlier versions of this manuscript. This research was supported by NIH P50 NS19632 and the Kiwanis Foundation.

- Anderson SW, Rizzo M, Skaar N, Stierman L, Cavaco S, Dawson J, et al. Amnesia and driving. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2007; 29 :1–12. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Baddeley A, Wilson BA. When implicit learning fails: amnesia and the problem of error elimination. Neuropsychologia. 1994; 32 :53–68. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Baird A, Samson S. Memory for music in Alzheimer’s disease: Unforgettable? Neuropsychological Review. 2009; 19 :85–101. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Baur B, Uttner I, Ilmberger J, Fesl G, Mai N. Music memory provides access to verbal knowledge in a patient with global amnesia. Neurocase. 2000; 6 :415–421. [ Google Scholar ]

- Beatty WW, Brumback RA, Vonsattel JP. Autopsy-proven Alzheimer disease in a patient with dementia who retained musical skill in life. Archives of Neurology. 1997; 54 :1448. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Beatty WW, Zavadil KD, Bailly RC, Rixen GJ, Zavadil LE, Farnham N, et al. Preserved musical skill in a severely demented patient. International Journal of Clinical Neuropsychology. 1988; 10 :158–64. [ Google Scholar ]

- Beatty WW, Winn P, Adams RL, Allen EW, Wilson DA, Prince JR, et al. Preserved cognitive skills in dementia of the Alzheimer type. Archives of Neurology. 1994; 51 :1040–6. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Beatty WW, Rogers CL, Rogers RL, English S, Testa JA, Orbelo DM, et al. Piano playing in Alzheimer’s disease: Longitudinal study of a single case. Neurocase. 1999; 5 :459–69. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cavaco S, Anderson SW, Allen JS, Castro-Caldas A, Damasio H. The scope of preserved procedural memory in amnesia. Brain. 2004; 127 :1853–1867. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cavaco S, Anderson SW, Correia M, Magalhães M, Pereira C, Tuna A, et al. Task-specific contribution of the human striatum to perceptual-motor skill learning. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2011; 33 :51–62. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cohen NJ, Squire LR. Preserved learning and retention of pattern analyzing skill in amnesia: dissociation of knowing how and knowing that. Science. 1980; 210 :207–209. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cohen NJ, Poldrack RA, Eichenbaum H. Memory for items and memory for relations in the procedural/declarative memory framework. Memory. 1997; 5 :131–178. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cowles A, Beatty WW, Nixon SJ, Lutz LJ, Paulk J, Paulk K, et al. Musical Skill in Dementia: A Violinist Presumed to Have Alzheimer’s Disease Learns to Play a New Song. Neurocase. 2003; 9 :493–503. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Crystal H, Grober E, Masur D. Preservation of musical memory in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 1989; 52 :1415–1416. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fornazzari L, Castle T, Nadkarni S, Ambrose M, Miranda D, Apanasiewicz, et al. Preservation of episodic musical memory in a pianist with Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006; 66 :610–611. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Furneaux S, Land MF. The effects of skill on the eye-hand span during musical sight-reading. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B. 1999; 266 :2435–2440. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gabrieli JDE, Corkin S, Mickel SF, Growdon JH. Intact acquisition and long-term retention of mirror-tracing skill in Alzheimer’s disease and in global amnesia. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1993; 107 :899–910. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hay JF, Moscovitch M, Levine B. Dissociating habit and recollection: evidence from Parkinson’s disease, amnesia and focal lesion patients. Neuropsychologia. 2002; 40 :1324–1334. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Laforce R, Doyon J. Distinct contribution of the striatum and cerebellum to motor learning. Brain & Cognition. 2001; 45 :189–211. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Levitin DJ. This is your brain on music. New York: Plume; 2007. [ Google Scholar ]

- Milner B. Colloques Internationaux du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique. Physiologie de L’Hippocampe, colloques internationaux. 107. Paris: Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique; 1962. Les troubles de la mémoire accompagnant des lésions hippocampiques bilatérales; pp. 257–272. [ Google Scholar ]

- Parsons LM, Sergent J, Hodges DA, Fox PT. The brain basis of piano performance. Neuropsychologia. 2005; 43 :199–215. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sacks O. Musicophilia: Tales of music and the brain. New York: Random House; 2008. [ Google Scholar ]

- Schacter DL. Amnesia observed: remembering and forgetting in a natural environment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1983; 92 :236–242. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sergent J, Zuck E, Terriah S, MacDonald B. Distributed neural network underlying musical sight-reading and keyboard performance. Science. 1992; 257 :106–109. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Squire LR. Memory systems of the brain: a brief and current perspective. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2004; 82 :171–177. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stewart L, Henson R, Kampe K, Walsh V, Turner R, Frith U. Brain changes after learning to read and play music. Neuroimage. 2003; 20 :71–83. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tranel D. The Iowa-Benton school of neuropsychological assessment. In: Grant I, Adams KM, editors. Neuropsychological assessment of neuropsychiatric disorders. 3. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 66–83. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tranel D, Damasio AR, Damasio H, Brandt JP. Sensorimotor skill learning in amnesia: Additional evidence for the neural basis of nondeclarative memory. Learning and Memory. 1994; 1 :165–179. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wilson BA, Baddeley AD, Kapur N. Dense amnesia in a professional musician following herpes simplex virus encephalitis. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 1995; 17 :668–81. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

Find anything you save across the site in your account

By Oliver Sacks

In March of 1985, Clive Wearing, an eminent English musician and musicologist in his mid-forties, was struck by a brain infection—a herpes encephalitis—affecting especially the parts of his brain concerned with memory. He was left with a memory span of only seconds—the most devastating case of amnesia ever recorded. New events and experiences were effaced almost instantly. As his wife, Deborah, wrote in her 2005 memoir, “Forever Today”:

His ability to perceive what he saw and heard was unimpaired. But he did not seem to be able to retain any impression of anything for more than a blink. Indeed, if he did blink, his eyelids parted to reveal a new scene. The view before the blink was utterly forgotten. Each blink, each glance away and back, brought him an entirely new view. I tried to imagine how it was for him. . . . Something akin to a film with bad continuity, the glass half empty, then full, the cigarette suddenly longer, the actor’s hair now tousled, now smooth. But this was real life, a room changing in ways that were physically impossible.

In addition to this inability to preserve new memories, Clive had a retrograde amnesia, a deletion of virtually his entire past.

When he was filmed in 1986 for Jonathan Miller’s extraordinary documentary “Prisoner of Consciousness,” Clive showed a desperate aloneness, fear, and bewilderment. He was acutely, continually, agonizingly conscious that something bizarre, something awful, was the matter. His constantly repeated complaint, however, was not of a faulty memory but of being deprived, in some uncanny and terrible way, of all experience, deprived of consciousness and life itself. As Deborah wrote:

It was as if every waking moment was the first waking moment. Clive was under the constant impression that he had just emerged from unconsciousness because he had no evidence in his own mind of ever being awake before. . . . “I haven’t heard anything, seen anything, touched anything, smelled anything,” he would say. “It’s like being dead.”

Desperate to hold on to something, to gain some purchase, Clive started to keep a journal, first on scraps of paper, then in a notebook. But his journal entries consisted, essentially, of the statements “I am awake” or “I am conscious,” entered again and again every few minutes. He would write: “2:10 P.M : This time properly awake. . . . 2:14 P.M : this time finally awake. . . . 2:35 P.M : this time completely awake,” along with negations of these statements: “At 9:40 P.M. I awoke for the first time, despite my previous claims.” This in turn was crossed out, followed by “I was fully conscious at 10:35 P.M. , and awake for the first time in many, many weeks.” This in turn was cancelled out by the next entry.

This dreadful journal, almost void of any other content but these passionate assertions and denials, intending to affirm existence and continuity but forever contradicting them, was filled anew each day, and soon mounted to hundreds of almost identical pages. It was a terrifying and poignant testament to Clive’s mental state, his lostness, in the years that followed his amnesia—a state that Deborah, in Miller’s film, called “a never-ending agony.”

Another profoundly amnesic patient I knew some years ago dealt with his abysses of amnesia by fluent confabulations. He was wholly immersed in his quick-fire inventions and had no insight into what was happening; so far as he was concerned, there was nothing the matter. He would confidently identify or misidentify me as a friend of his, a customer in his delicatessen, a kosher butcher, another doctor—as a dozen different people in the course of a few minutes. This sort of confabulation was not one of conscious fabrication. It was, rather, a strategy, a desperate attempt—unconscious and almost automatic—to provide a sort of continuity, a narrative continuity, when memory, and thus experience, was being snatched away every instant.

Though one cannot have direct knowledge of one’s own amnesia, there may be ways to infer it: from the expressions on people’s faces when one has repeated something half a dozen times; when one looks down at one’s coffee cup and finds that it is empty; when one looks at one’s diary and sees entries in one’s own handwriting. Lacking memory, lacking direct experiential knowledge, amnesiacs have to make hypotheses and inferences, and they usually make plausible ones. They can infer that they have been doing something, been somewhere , even though they cannot recollect what or where. Yet Clive, rather than making plausible guesses, always came to the conclusion that he had just been “awakened,” that he had been “dead.” This seemed to me a reflection of the almost instantaneous effacement of perception for Clive—thought itself was almost impossible within this tiny window of time. Indeed, Clive once said to Deborah, “I am completely incapable of thinking.” At the beginning of his illness, Clive would sometimes be confounded at the bizarre things he experienced. Deborah wrote of how, coming in one day, she saw him

holding something in the palm of one hand, and repeatedly covering and uncovering it with the other hand as if he were a magician practising a disappearing trick. He was holding a chocolate. He could feel the chocolate unmoving in his left palm, and yet every time he lifted his hand he told me it revealed a brand new chocolate. “Look!” he said. “It’s new!” He couldn’t take his eyes off it. “It’s the same chocolate,” I said gently. “No . . . look! It’s changed. It wasn’t like that before . . .” He covered and uncovered the chocolate every couple of seconds, lifting and looking. “Look! It’s different again! How do they do it?”

Within months, Clive’s confusion gave way to the agony, the desperation, that is so clear in Miller’s film. This, in turn, was succeeded by a deep depression, as it came to him—if only in sudden, intense, and immediately forgotten moments—that his former life was over, that he was incorrigibly disabled.

As the months passed without any real improvement, the hope of significant recovery became fainter and fainter, and toward the end of 1985 Clive was moved to a room in a chronic psychiatric unit—a room he was to occupy for the next six and a half years but which he was never able to recognize as his own. A young psychologist saw Clive for a period of time in 1990 and kept a verbatim record of everything he said, and this caught the grim mood that had taken hold. Clive said at one point, “Can you imagine one night five years long? No dreaming, no waking, no touch, no taste, no smell, no sight, no sound, no hearing, nothing at all. It’s like being dead. I came to the conclusion that I was dead.”

The only times of feeling alive were when Deborah visited him. But the moment she left, he was desperate once again, and by the time she got home, ten or fifteen minutes later, she would find repeated messages from him on her answering machine: “Please come and see me, darling—it’s been ages since I’ve seen you. Please fly here at the speed of light.”

To imagine the future was no more possible for Clive than to remember the past—both were engulfed by the onslaught of amnesia. Yet, at some level, Clive could not be unaware of the sort of place he was in, and the likelihood that he would spend the rest of his life, his endless night, in such a place.

But then, seven years after his illness, after huge efforts by Deborah, Clive was moved to a small country residence for the brain-injured, much more congenial than a hospital. Here he was one of only a handful of patients, and in constant contact with a dedicated staff who treated him as an individual and respected his intelligence and talents. He was taken off most of his heavy tranquillizers, and seemed to enjoy his walks around the village and gardens near the home, the spaciousness, the fresh food.

For the first eight or nine years in this new home, Deborah told me, “Clive was calmer and sometimes jolly, a bit more content, but often with angry outbursts still, unpredictable, withdrawn, spending most of his time in his room alone.” But gradually, in the past six or seven years, Clive has become more sociable, more talkative. Conversation (though of a “scripted” sort) has come to fill what had been empty, solitary, and desperate days.

Though I had corresponded with Deborah since Clive first became ill, twenty years went by before I met Clive in person. He was so changed from the haunted, agonized man I had seen in Miller’s 1986 film that I was scarcely prepared for the dapper, bubbling figure who opened the door when Deborah and I went to visit him in the summer of 2005. He had been reminded of our visit just before we arrived, and he flung his arms around Deborah the moment she entered.

Deborah introduced me: “This is Dr. Sacks.” And Clive immediately said, “You doctors work twenty-four hours a day, don’t you? You’re always in demand.” We went up to his room, which contained an electric organ console and a piano piled high with music. Some of the scores, I noted, were transcriptions of Orlandus Lassus, the Renaissance composer whose works Clive had edited. I saw Clive’s journal by the washstand—he has now filled up scores of volumes, and the current one is always kept in this exact location. Next to it was an etymological dictionary with dozens of reference slips of different colors stuck between the pages and a large, handsome volume, “The 100 Most Beautiful Cathedrals in the World.” A Canaletto print hung on the wall, and I asked Clive if he had ever been to Venice. No, he said. (Deborah told me they had visited several times before his illness.) Looking at the print, Clive pointed out the dome of a church: “Look at it,” he said. “See how it soars—like an angel!”

When I asked Deborah whether Clive knew about her memoir, she told me that she had shown it to him twice before, but that he had instantly forgotten. I had my own heavily annotated copy with me, and asked Deborah to show it to him again.

“You’ve written a book!” he cried, astonished. “Well done! Congratulations!” He peered at the cover. “All by you? Good heavens!” Excited, he jumped for joy. Deborah showed him the dedication page: “For my Clive.” “Dedicated to me?” He hugged her. This scene was repeated several times within a few minutes, with almost exactly the same astonishment, the same expressions of delight and joy each time.

Clive and Deborah are still very much in love with each other, despite his amnesia. (Indeed, Deborah’s book is subtitled “A Memoir of Love and Amnesia.”) He greeted her several times as if she had just arrived. It must be an extraordinary situation, I thought, both maddening and flattering, to be seen always as new, as a gift, a blessing.

Clive had, in the meantime, addressed me as “Your Highness” and inquired at intervals, “Been at Buckingham Palace? . . . Are you the Prime Minister? . . . Are you from the U.N.?” He laughed when I answered, “Just the U.S.” This joking or jesting was of a somewhat waggish, stereotyped nature and highly repetitive. Clive had no idea who I was, little idea who anyone was, but this bonhomie allowed him to make contact, to keep a conversation going. I suspected he had some damage to his frontal lobes, too—such jokiness (neurologists speak of Witzelsucht, joking disease), like his impulsiveness and chattiness, could go with a weakening of the usual social frontal-lobe inhibitions.

He was excited at the notion of going out for lunch—lunch with Deborah. “Isn’t she a wonderful woman?” he kept asking me. “Doesn’t she have marvellous kisses?” I said yes, I was sure she had.

As we drove to the restaurant, Clive, with great speed and fluency, invented words for the letters on the license plates of passing cars: “JCK” was Japanese Clever Kid; “NKR” was New King of Russia; and “BDH” (Deborah’s car) was British Daft Hospital, then Blessed Dutch Hospital. “Forever Today,” Deborah’s book, immediately became “Three-Ever Today,” “Two-Ever Today,” “One-Ever Today.” This incontinent punning and rhyming and clanging was virtually instantaneous, occurring with a speed no normal person could match. It resembled Tourettic or savantlike speed, the speed of the preconscious, undelayed by reflection.

When we arrived at the restaurant, Clive did all the license plates in the parking lot and then, elaborately, with a bow and a flourish, let Deborah enter: “Ladies first!” He looked at me with some uncertainty as I followed them to the table: “Are you joining us, too?”

When I offered him the wine list, he looked it over and exclaimed, “Good God! Australian wine! New Zealand wine! The colonies are producing something original—how exciting!” This partly indicated his retrograde amnesia—he is still in the nineteen-sixties (if he is anywhere), when Australian and New Zealand wines were almost unheard of in England. “The colonies,” however, was part of his compulsive waggery and parody.

At lunch he talked about Cambridge—he had been at Clare College, but had often gone next door to King’s, for its famous choir. He spoke of how after Cambridge, in 1968, he joined the London Sinfonietta, where they played modern music, though he was already attracted to the Renaissance and Lassus. He was the chorus master there, and he reminisced about how the singers could not talk during coffee breaks; they had to save their voices (“It was often misunderstood by the instrumentalists, seemed standoffish to them”). These all sounded like genuine memories. But they could equally have reflected his knowing about these events, rather than actual memories of them—expressions of “semantic” memory rather than “event” or “episodic” memory. Then he spoke of the Second World War (he was born in 1938) and how his family would go to bomb shelters and play chess or cards there. He said that he remembered the doodlebugs: “There were more bombs in Birmingham than in London.” Was it possible that these were genuine memories? He would have been only six or seven, at most. Or was he confabulating or simply, as we all do, repeating stories he had been told as a child?

At one point, he talked about pollution and how dirty petrol engines were. When I told him I had a hybrid with an electric motor as well as a combustion engine, he was astounded, as if something he had read about as a theoretical possibility had, far sooner than he had imagined, become a reality.

In her remarkable book, so tender yet so tough-minded and realistic, Deborah wrote about the change that had so struck me: that Clive was now “garrulous and outgoing . . . could talk the hind legs off a donkey.” There were certain themes he tended to stick to, she said, favorite subjects (electricity, the Tube, stars and planets, Queen Victoria, words and etymologies), which would all be brought up again and again:

“Have they found life on Mars yet?” “No, darling, but they think there might have been water . . .” “Really? Isn’t it amazing that the sun goes on burning? Where does it get all that fuel? It doesn’t get any smaller. And it doesn’t move. We move round the sun. How can it keep on burning for millions of years? And the Earth stays the same temperature. It’s so finely balanced.” “They say it’s getting warmer now, love. They call it global warming.” “No! Why’s that?” “Because of the pollution. We’ve been emitting gases into the atmosphere. And puncturing the ozone layer.” “ OH NO ! That could be disastrous!” “People are already getting more cancers.” “Oh, aren’t people stupid! Do you know the average IQ is only 100? That’s terribly low, isn’t it? One hundred. It’s no wonder the world’s in such a mess.” Clive’s scripts were repeated with great frequency, sometimes three or four times in one phone call. He stuck to subjects he felt he knew something about, where he would be on safe ground, even if here and there something apocryphal crept in. . . . These small areas of repartee acted as stepping stones on which he could move through the present. They enabled him to engage with others.

I would put it even more strongly and use a phrase that Deborah used in another connection, when she wrote of Clive being poised upon “a tiny platform . . . above the abyss.” Clive’s loquacity, his almost compulsive need to talk and keep conversations going, served to maintain a precarious platform, and when he came to a stop the abyss was there, waiting to engulf him. This, indeed, is what happened when we went to a supermarket and he and I got separated briefly from Deborah. He suddenly exclaimed, “I’m conscious now . . . . Never saw a human being before . . . for thirty years . . . . It’s like death!” He looked very angry and distressed. Deborah said the staff calls these grim monologues his “deads”—they make a note of how many he has in a day or a week and gauge his state of mind by their number.

Deborah thinks that repetition has slightly dulled the very real pain that goes with this agonized but stereotyped complaint, but when he says such things she will distract him immediately. Once she has done this, there seems to be no lingering mood—an advantage of his amnesia. And, indeed, once we returned to the car Clive was off on his license plates again.

Back in his room, I spotted the two volumes of Bach’s “Forty-eight Preludes and Fugues” on top of the piano and asked Clive if he would play one of them. He said that he had never played any of them before, but then he began to play Prelude 9 in E Major and said, “I remember this one.” He remembers almost nothing unless he is actually doing it; then it may come to him. He inserted a tiny, charming improvisation at one point, and did a sort of Chico Marx ending, with a huge downward scale. With his great musicality and his playfulness, he can easily improvise, joke, play with any piece of music.

His eye fell on the book about cathedrals, and he talked about cathedral bells—did I know how many combinations there could be with eight bells? “Eight by seven by six by five by four by three by two by one,” he rattled off. “Factorial eight.” And then, without pause: “That’s forty thousand.” (I worked it out, laboriously: it is 40,320.)

I asked him about Prime Ministers. Tony Blair? Never heard of him. John Major? No. Margaret Thatcher? Vaguely familiar. Harold Macmillan, Harold Wilson: ditto. (But earlier in the day he had seen a car with “JMV” plates and instantly said, “John Major Vehicle”—showing that he had an implicit memory of Major’s name.) Deborah wrote of how he could not remember her name, “but one day someone asked him to say his full name, and he said, ‘Clive David Deborah Wearing—funny name that. I don’t know why my parents called me that.’ ” He has gained other implicit memories, too, slowly picking up new knowledge, like the layout of his residence. He can go alone now to the bathroom, the dining room, the kitchen—but if he stops and thinks en route he is lost. Though he could not describe his residence, Deborah tells me that he unclasps his seat belt as they draw near and offers to get out and open the gate. Later, when he makes her coffee, he knows where the cups, the milk, and the sugar are kept. He cannot say where they are, but he can go to them; he has actions, but few facts, at his disposal.

I decided to widen the testing and asked Clive to tell me the names of all the composers he knew. He said, “Handel, Bach, Beethoven, Berg, Mozart, Lassus.” That was it. Deborah told me that at first, when asked this question, he would omit Lassus, his favorite composer. This seemed appalling for someone who had been not only a musician but an encyclopedic musicologist. Perhaps it reflected the shortness of his attention span and recent immediate memory—perhaps he thought that he had in fact given us dozens of names. So I asked him other questions on a variety of topics that he would have been knowledgeable about in his earlier days. Again, there was a paucity of information in his replies and sometimes something close to a blank. I started to feel that I had been beguiled, in a sense, by Clive’s easy, nonchalant, fluent conversation into thinking that he still had a great deal of general information at his disposal, despite the loss of memory for events. Given his intelligence, ingenuity, and humor, it was easy to think this on meeting him for the first time. But repeated conversations rapidly exposed the limits of his knowledge. It was indeed as Deborah wrote in her book, Clive “stuck to subjects he knew something about” and used these islands of knowledge as “stepping stones” in his conversation. Clearly, Clive’s general knowledge, or semantic memory, was greatly affected, too—though not as catastrophically as his episodic memory.

Yet semantic memory of this sort, even if completely intact, is not of much use in the absence of explicit, episodic memory. Clive is safe enough in the confines of his residence, for instance, but he would be hopelessly lost if he were to go out alone. Lawrence Weiskrantz comments on the need for both sorts of memory in his 1997 book “Consciousness Lost and Found”:

The amnesic patient can think about material in the immediate present. . . . He can also think about items in his semantic memory, his general knowledge. . . . But thinking for successful everyday adaptation requires not only factual knowledge, but the ability to recall it on the right occasion, to relate it to other occasions, indeed the ability to reminisce.

This uselessness of semantic memory unaccompanied by episodic memory is also brought out by Umberto Eco in his novel “The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana,” in which the narrator, an antiquarian bookseller and polymath, is a man of Eco-like intelligence and erudition. Though amnesic from a stroke, he retains the poetry he has read, the many languages he knows, his encyclopedic memory of facts; but he is nonetheless helpless and disoriented (and recovers from this only because the effects of his stroke are transient).

It is similar, in a way, with Clive. His semantic memory, while of little help in organizing his life, does have a crucial social role: it allows him to engage in conversation (though it is occasionally more monologue than conversation). Thus, Deborah wrote, “he would string all his subjects together in a row, and the other person simply needed to nod or mumble.” By moving rapidly from one thought to another, Clive managed to secure a sort of continuity, to hold the thread of consciousness and attention intact—albeit precariously, for the thoughts were held together, on the whole, by superficial associations. Clive’s verbosity made him a little odd, a little too much at times, but it was highly adaptive—it enabled him to reënter the world of human discourse.

In the 1986 film, Deborah quoted Proust’s description of Swann waking from a deep sleep, not knowing at first where he was, who he was, what he was. He had only “the most rudimentary sense of existence, such as may lurk and flicker in the depths of an animal’s consciousness,” until memory came back to him, “like a rope let down from heaven to draw me up out of the abyss of not-being, from which I could never have escaped by myself.” This gave him back his personal consciousness and identity. No rope from Heaven, no autobiographical memory will ever come down in this way to Clive. F rom the start there have been, for Clive, two realities of immense importance. The first of these is Deborah, whose presence and love for him have made life tolerable, at least intermittently, in the twenty or more years since his illness. Clive’s amnesia not only destroyed his ability to retain new memories; it deleted almost all of his earlier memories, including those of the years when he met and fell in love with Deborah. He told Deborah, when she questioned him, that he had never heard of John Lennon or John F. Kennedy. Though he always recognized his own children, Deborah told me, “he would be surprised at their height and amazed to hear he is a grandfather. He asked his younger son what O-level exams he was doing in 2005, more than twenty years after Edmund left school.” Yet somehow he always recognized Deborah as his wife, when she visited, and felt moored by her presence, lost without her. He would rush to the door when he heard her voice, and embrace her with passionate, desperate fervor. Having no idea how long she had been away—since anything not in his immediate field of perception and attention would be lost, forgotten, within seconds—he seemed to feel that she, too, had been lost in the abyss of time, and so her “return” from the abyss seemed nothing short of miraculous. As Deborah put it:

Clive was constantly surrounded by strangers in a strange place, with no knowledge of where he was or what had happened to him. To catch sight of me was always a massive relief—to know that he was not alone, that I still cared, that I loved him, that I was there. Clive was terrified all the time. But I was his life, I was his lifeline. Every time he saw me, he would run to me, fall on me, sobbing, clinging.

How, why, when he recognized no one else with any consistency, did Clive recognize Deborah? There are clearly many sorts of memory, and emotional memory is one of the deepest and least understood.