A Quick Overview: Differences Among Desk, Literature, and Learning Reviews

November 12, 2020

By: Chelsie Kuhn, MEL Associate, Headlight Consulting Services, LLP

This is the first post in a series of two about Learning Reviews .

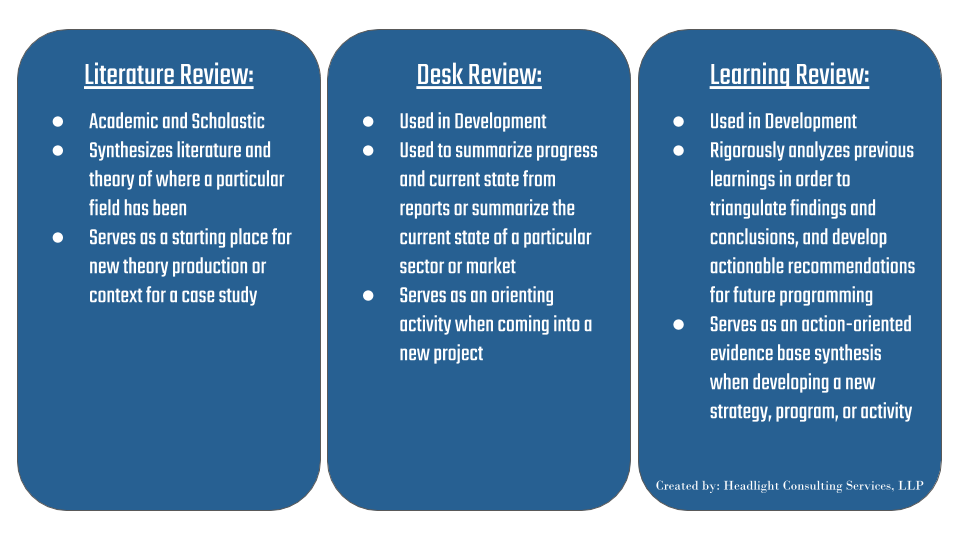

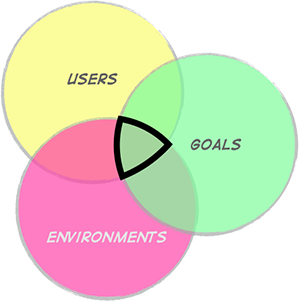

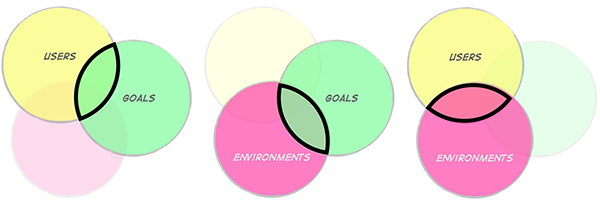

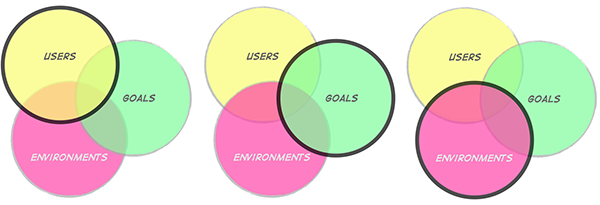

In order to chart the wisest path forward, we need to understand where we have been. Reflecting on past learning can ensure more effective and efficient efforts in the future, regardless of discipline or field. But different information needs require different tools. Literature, Desk, and Learning Reviews are three ways to integrate evidence into decision-making and design processes. Each tool uses varying degrees of information and rigor, and each is best suited for different applications, as described in the visual below.

A Literature Review traditionally focuses on academic journal articles and published books, giving readers a theoretical or case-based frame of reference. A Literature Review may be appropriate for researchers looking to set up an experiment or randomized control trial in a location or those looking at theoretical development over time. This kind of review is all about synthesis of what we know research-wise up to the current point, and what potential gaps exist yet to be filled.

Another type of review widely known is a Desk Review, which serves to provide readers with an introduction into a project’s context and priorities, but often not the past learnings or in-depth challenges needed to inform strategy development. A Desk Review can also serve as an entry point to understanding a particular market or an effective way to organize and summarize disparate types of information. Doing a Desk Review might be appropriate to bring a new team member up to speed on projects or learn about the current state and environment concerning a particular type of intervention.

While Literature and Desk Reviews may be more commonly known, one of the offerings that Headlight specializes in is a Learning Review. A Learning Review is a way to systematically look at past assessments, evaluations, reports, and any other learning documentation in order to inform recommendations and strategy, program, or activity design efforts. Unlike Desk Reviews, Learning Reviews focus on coding and analyzing data instead of summarizing it. With layers of triangulation and secondary analysis built into the process, we can confidently draw findings and conclusions knowing that the foundation of the process is built with rigor. Recommendations stemming from these findings and conclusions serve as the best use of an existing evidence base in designing or revisiting strategies, programs, and activities. Each of these three tools are useful at different points, but as we see more and more emphasis placed on learning and adaptive management, Learning Reviews offer a more rigorous and application focused use of available evidence.

As a synthesis of past evaluations and assessments, Learning Reviews should also be used to feed into new MEL or CLA plans. Having extra information on what has worked in the past, what information was useful, and where more-nuanced information would be beneficial enables us to set better targets and understand potential barriers to measurement. Recommendations may even point to specific indicators to consider or CLA actions to integrate into programming moving forward. Learning Reviews can also be used to appropriately scope and identify future evaluative efforts that will evolve the evidence base.

In the next post in the series, we will expand further on Learning Reviews as a process and walk readers step-by-step through how to conduct one. If you need help implementing any of these above tools, but in particular a Learning Review, Headlight would love to support you! We have the breadth and depth of expertise, experience, and toolbox to tailor-meet your needs. For more information about our services please email [email protected] . Headlight Consulting Services, LLP is a certified women-owned small business and therefore eligible for sole source procurements. We can be found on the Dynamic Small Business Search or on SAM.gov via our name or DUNS number (081332548).

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

no comments found.

Subscribe to Blog via Email

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Email Address

Recent Posts

- Evaluation Rigor in Action — The Qualitative Comparative Analysis Methods Memo

- 2023 in Review: Headlight’s Values in Action

- The Small Business Chrysalis: Reflections on Becoming a Prime

- Choose Your Own Adventure: Options for Adapting the Collaborating, Learning & Adapting (CLA) Maturity Self-assessment Process

- Evaluation for Learning and Adaptive Management: Connecting the Dots between Developmental Evaluation and CLA

Recent Comments

- Maxine Secskas on What is a USAID Performance Management Plan?

- Anonymous on What is a USAID Performance Management Plan?

- Getasew Atnafu on The Small Business Chrysalis: Reflections on Becoming a Prime

- Anonymous on The Small Business Chrysalis: Reflections on Becoming a Prime

- Anonymous on Why Embeddedness Is Crucial For Use-Focused Developmental Evaluation Support

- February 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- January 2023

- November 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- December 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- Uncategorized

- Opportunities

Desk research

What is it and how do you conduct it properly, deskresearch.

- Research method

View our services

Language check

Have your thesis or report reviewed for language, structure, coherence, and layout.

Plagiarism check

Check for free if your document contains plagiarism.

APA-generator

Create your reference list in APA style effortlessly. Completely free of charge.

What is desk research?

Desk research vs. literature reviews, desk research as a research method, how do you properly tackle desk research, where do you find information for desk research.

Desk research means that you use previously collected data for your research instead of collecting it yourself. You answer your research question based on the existing data you analyze. This might include previous literature, company information, or other available data. What exactly is desk research and how do you conduct it properly?

When you do desk research, you collect existing data and use it to learn more about your research topic. You are not collecting quantitative or qualitative data yourself through things like surveys, interviews or observations.

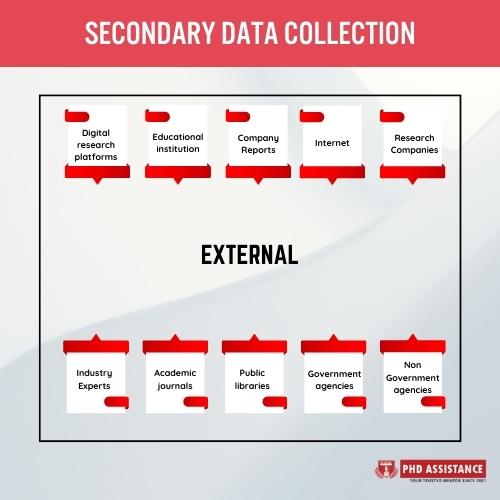

In desk research, you work with secondary data (data collected by someone else). In field research, on the other hand, you work with primary data (data you collected yourself).

Desk research is an especially relevant research method if a lot of information on a topic is already available and/or if it is difficult to collect this data yourself. This type of research is less appropriate if you are one of the first to research the topic.

Often the terms "desk research" and "literature review" are used interchangeably. However, they don't mean exactly the same thing.

A literature review (also called "narrative review") is designed to gain more theoretical knowledge about a topic.

In desk research you collect existing research results or factual results in order to use them to explain a certain phenomenon. In doing so, you often answer an explanatory research question. You investigate a possible connection between variables.

You can use desk research as a research method on its own in your thesis. Your entire thesis research will then consist of desk research. In that case, you describe the results of the desk research in the results chapter. In the method chapter you explain how you approached the research.

It is also possible for you to use desk research as a stepping stone to a study that you will conduct yourself with data you have collected yourself. You arrive at hypotheses or theories through desk research that you then test through your own data collection. When you use desk research in this way, you incorporate its results into the theoretical framework. This type of research is called deduction .

You can also use desk research to supplement, for example, surveys, interviews , an experiment, or observations. In these cases, desk research can help explain the results you found.

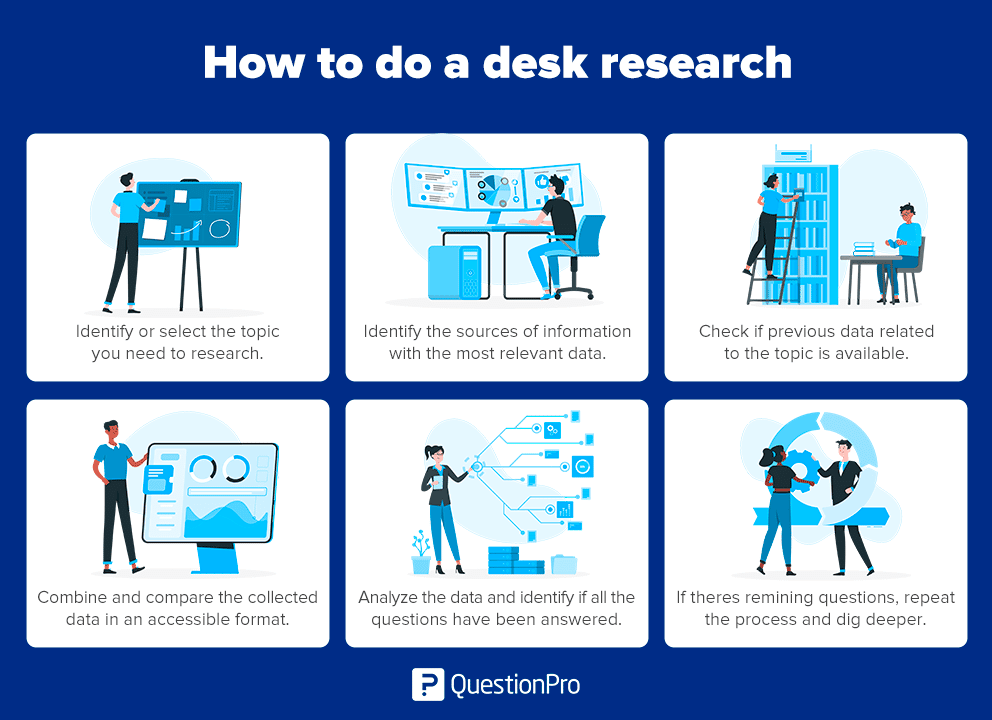

If you are going to conduct desk research, you need to go through a number of stages to do so. For example, it is important that you select the right sources and report on the sources in a logical way. To do this, take the following steps:

Determine appropriate search terms. First, determine what search terms you will use to find sources through, for example, your educational institution's online library or Google Scholar. Often, you will use terms that appear in your problem statement or research question. Search for English search terms and any other languages you may want to include.

Find appropriate sources. You do this with the chosen search terms, but also, for example, by looking in the list of found sources. Perhaps there is another useful source cited by one of the articles you read through. Save all sources in one convenient folder and put them in your bibliography so you don’t forget them.

Determine which sources are relevant. Not all sources found are equally relevant to your topic. You also want to avoid having so many sources that you cannot see the forest for the trees. Check whether the sources you have found actually match your problem, research question, and research goal. Also check the reliability of the source. Ideally you should mostly use sources from leading journals and from authors who are affiliated with a scientific institute.

Incorporate the sources you found into your text. Are you doing a quantitative analysis? If so, you will first use SPSS or Excel. Are you referring verbatim to content from the sources? Then it's mainly a matter of putting relevant content together correctly in your thesis. Make sure you create a logical thread, for example by discussing sources by topic or in chronological order.

Review the bibliography. Make sure all sources from your desk research are correctly listed in the bibliography. Also, check the source citation. Make sure your sources are formatted in APA style (or the source citation style that applies to your course).

The sources you use must be relevant and reliable. You cannot use sources like Wikipedia. In terms of sources, consider, for example:

scholarly articles (which you can find through Google Scholar and your university or college's online library, among others);

statistics from organizations such as the Central Bureau of Statistics or other reputable research institutions;

LexisNexis: a database of newspapers where you can find all kinds of news sources;

reliable databases within your field;

collections published with an academic publisher;

annual reports or corporate reports;

reports from other agencies;

literature;

documents from archives;

reports from the municipality, for example;

photographs or art objects.

Sometimes you can use very different types of sources for your research. For example, are you doing research on Instagram posts? Then, of course, you can collect existing Instagram posts on social media for that purpose and they count as sources.

Getting your sources checked

For desk research you often use a large number of sources. Unfortunately, it is easy to make an error when citing your sources. Do you want to prevent errors from creeping in unnoticed? Have your sources checked by one of our editors. They will review every source manually and ensure that all sources are correctly listed in your bibliography.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing - try for free!

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Skip navigation

- Log in to UX Certification

World Leaders in Research-Based User Experience

Secondary research in ux.

February 20, 2022 2022-02-20

- Email article

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share on Twitter

You don’t have to do all the user-research work yourself. If somebody else already ran a study (and published it), grab it!

Have you ever completed a project only to find out that something very similar has already been done in your organization a couple of years ago? That situation is common, especially with rising employee-churn rates, and fueled the popularity of research repositories (e.g., Microsoft Human Insights System) and the growth of the research-operations community . It should also inspire practitioners to do more secondary research.

Secondary research, also known as desk research or, in academic contexts, literature review, refers to the act of gathering prior research findings and other relevant information related to a new project. It is a foundational part of any emerging research project and provides the project with background and context. Secondary research allows us to stand on the shoulders of giants and not to reinvent the wheel every time we initiate a new program or plan a study.

This article provides a step-by-step guide on how to conduct secondary research in UX. The key takeaway is that this type of research is not solely an intellectual exercise, but a way to minimize research costs, win internal stakeholders and get scaffolding for your own projects.

Academic publications include a literature review at the beginning to showcase context or known gaps and to justify the motivation for the research questions. However, the task of incorporating previous results is becoming more and more challenging with a growing number of publications in all fields. Therefore, practitioners across disciplines (for instance in eHealth, business, education, and technology) develop method guidelines for secondary research.

In This Article:

When to conduct secondary research, types of secondary research, how to conduct secondary research.

Secondary research should be a standard first step in any rigorous research practice, but it’s also often cost-effective in more casual settings. Whether you are just starting a new project, joining an existing one, or planning a primary research effort for your team, it is always good to start with a broad overview of the field and existent resources. That would allow you to synthesize findings and uncover areas where more research is needed.

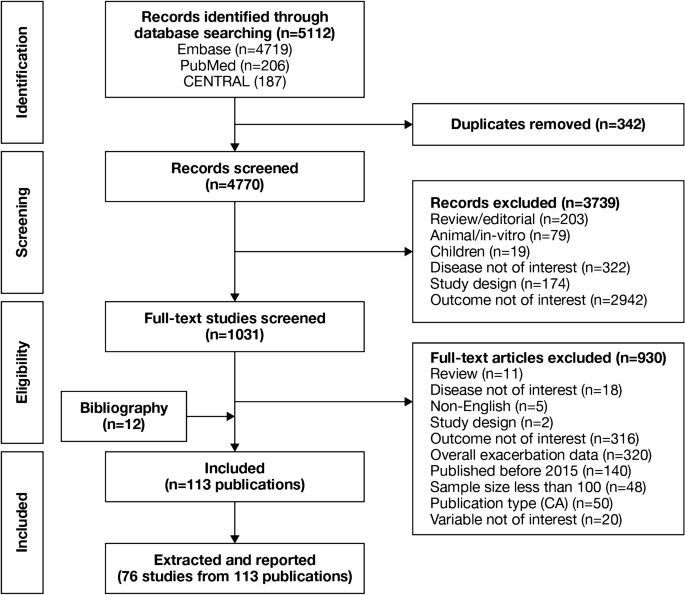

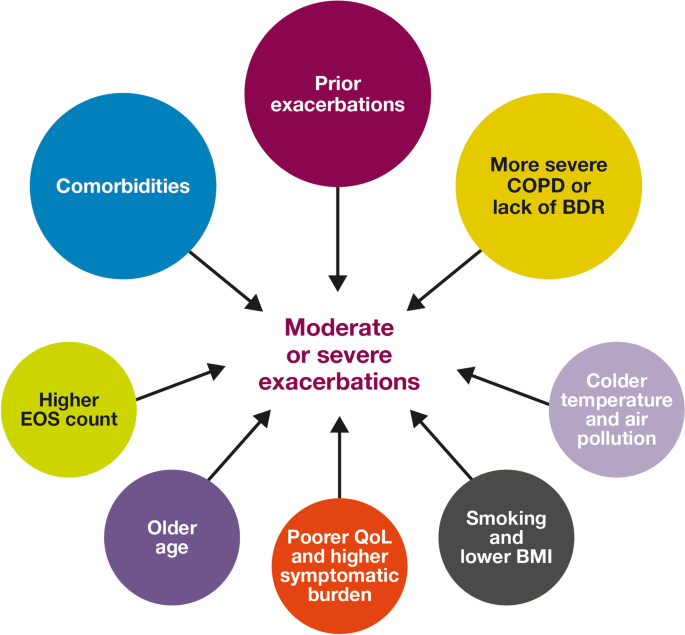

Secondary research shows which topics are particularly popular or important for your organization and what problems other researchers are trying to solve. This research method is widely discussed in library and information sciences but is often neglected in UX. Nonetheless, secondary research can be useful to uncover industry trends and to inspire further studies. For example, Jessica Pater and her colleagues looked at the foundational question of participant compensation in user studies. They could have opted for user interviews or a costly large-scale survey, yet through secondary research, they were able to review 2250 unique user studies across 1662 manuscripts published in 2018-2019. They found inconsistencies in participant compensation and suggested changes to the current practices and further research opportunities.

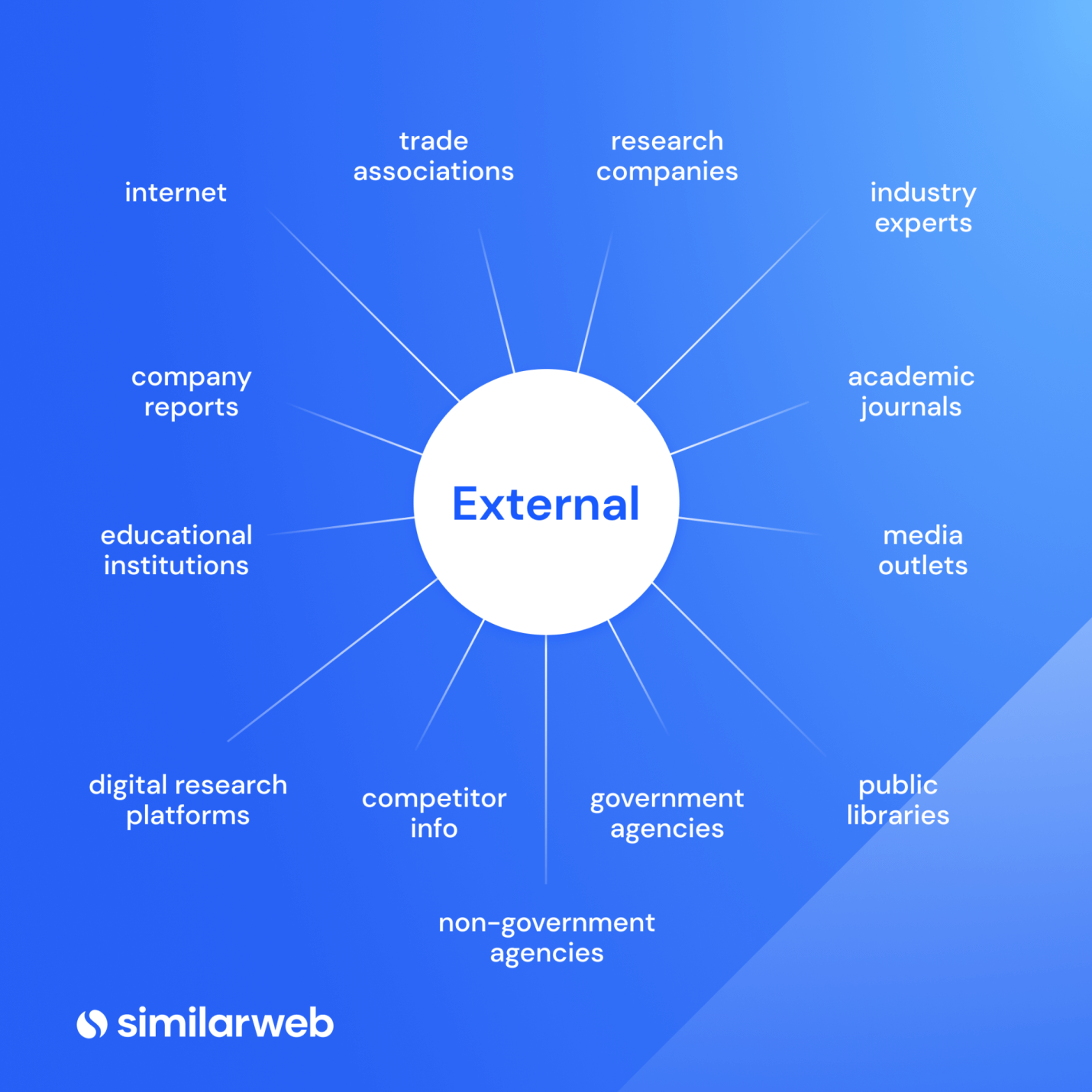

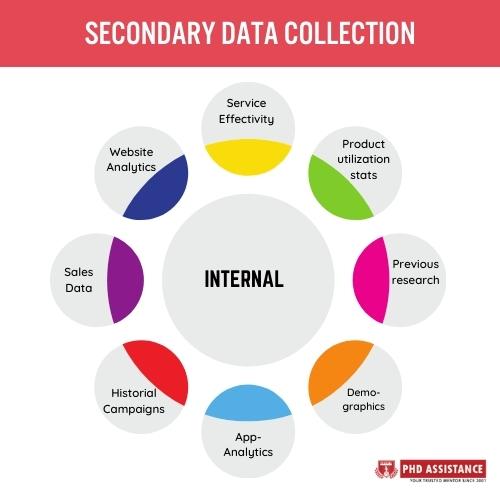

Secondary research can be divided into two main types: internal and external research.

Internal secondary research involves gathering all relevant research findings already available in your organization. These might include artifacts from the past primary research projects, maps (e.g., customer-journey map , service blueprint ), deliverables from external consultants, or results from different kinds of workshops (e.g., discovery, design thinking, etc.). Hopefully, these will be available in a research repository .

External secondary research is focused on sources outside of your organization, such as academic journals, public libraries, open data repositories, internet searches, and white papers published by reputable organizations. For example, external resources for the field of human-computer interaction (HCI) can be found at the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) digital library , Journal of Usability Studies (JUS ), or research websites like ours . University libraries and labs like UCSD Geisel Library , Carnegie Mellon University Libraries , MIT D-Lab , Stanford d.school , and specialized portals like Google Scholar offer another avenue for directed search.

Our goal is to have the necessary depth, rigor, and usefulness for practitioners. Here are the 4 steps for conducting secondary research:

- Choose the topic of research & write a problem statement .

Write a concise description of the problem to be solved. For example, if you are doing a website redesign, you might want to both learn the current standards and look at all the previous design iterations to avoid issues that your team already identified.

- Identi fy external and internal resources.

Peer-reviewed publications (such as those published in academic journals and conferences) are a fairly reliable source. They always include a section describing methods, data-collection techniques, and study limitations. If a study you plan to use does not include such information, that might be a red flag and a reason to further scrutinize that source. Public datasets also often present some challenges because of errors and inclusion criteria, especially if they were collected for another purpose.

One should be cautious of the seemingly reputable “research” findings published across different websites in a form of blog posts, which could be opinion pieces, not backed up by primary research. If you encounter such a piece, ask yourself — is the conclusion of the writeup based on a real study? If the study was quantitative, was it properly analyzed (e.g., at the very least, are confidence intervals reported, and was statistical significance evaluated?). For all studies, was the method sound and nonbiased (e.g., did the study have internal and external validity )?

A more nuanced challenge involves evaluating findings based on a different audience, which might not be always generalizable to your situation, but may form hypotheses worthy of investigating. For example, if a design pattern is found okay to use by young adults, you may still want to know if this finding will also be valid for older generations.

- Collect and analyze data from external and internal resources.

Remember that secondary research involves both the existing data and existing research. Both of those categories become helpful resources when they are critically evaluated for any inherent biases, omissions, and limitations. If you already have some secondary data in your organization, such as customer service logs or search logs, you should include them in secondary research alongside any existent analysis of such logs and previous reports. It is helpful to revisit previous findings, compare how they have or have not been implemented to refresh institutional memory and support future research initiatives.

- Refine your problem statement and determine what still needs to be investigated.

Once you collected the relevant information, write a summary of findings, and discuss them with your team. You might need to refine your problem statement to determine what information you still need to answer your research questions. Next time your team is planning to adopt a trendy new design pattern, it may be a good idea to go back and search the web or an academic database for any evaluations of that pattern.

It is important to note that secondary research is not a substitute for primary research. It is always better to do both. Although secondary research is often cost-effective and quick, its quality depends to a large extent on the quality of your sources. Therefore, before using any secondary sources, you need to identify their validity and limitations.

Secondary (or desk) research involves gathering existing data from inside and outside of your organization. A literature review should be done more frequently in UX because it is a viable option even for researchers with limited time and budget. The most challenging part is to persuade yourself and your team that the existing data is worth being summarized, compared, and collated to increase the overall effectiveness of your primary research.

Jessica Pater, Amanda Coupe, Rachel Pfafman, Chanda Phelan, Tammy Toscos, and Maia Jacobs. 2021. Standardizing Reporting of Participant Compensation in HCI: A Systematic Literature Review and Recommendations for the Field. In Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 141, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1145/3411764.3445734

Hannah Snyder. 2019. Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. Journal of business research 104, 333-339. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.039.

Related Courses

Discovery: building the right thing.

Conduct successful discovery phases to ensure you build the best solution

User Research Methods: From Strategy to Requirements to Design

How to pick the best UX research method for each stage in the development process

ResearchOps: Scaling User Research

Orchestrate and optimize research to amplify its impact

Related Topics

- Research Methods Research Methods

Learn More:

Always Pilot Test User Research Studies

Kim Salazar · 3 min

Level Up Your Focus Groups

Therese Fessenden · 5 min

Inductively Analyzing Qualitative Data

Tanner Kohler · 3 min

Related Articles:

Open-Ended vs. Closed Questions in User Research

Maria Rosala · 5 min

UX Research Methods: Glossary

Raluca Budiu · 12 min

Recruiting and Screening Candidates for User Research Projects

Therese Fessenden · 10 min

ResearchOps: Study Guide

Kate Kaplan · 5 min

International Usability Testing: Why You Need It

Feifei Liu · 10 min

Triangulation: Get Better Research Results by Using Multiple UX Methods

Kathryn Whitenton · 3 min

How To Do Secondary Research or a Literature Review

- Secondary Research

- Literature Review

- Step 1: Develop topic

- Step 2: Develop your search strategy

- Step 3. Document search strategy and organize results

- Systematic Literature Review Tips

- More Information

Search our FAQ

Make a research appointment.

Schedule a personalized one-on-one research appointment with one of Galvin Library's research specialists.

What is Secondary Research?

Secondary research, also known as a literature review , preliminary research , historical research , background research , desk research , or library research , is research that analyzes or describes prior research. Rather than generating and analyzing new data, secondary research analyzes existing research results to establish the boundaries of knowledge on a topic, to identify trends or new practices, to test mathematical models or train machine learning systems, or to verify facts and figures. Secondary research is also used to justify the need for primary research as well as to justify and support other activities. For example, secondary research may be used to support a proposal to modernize a manufacturing plant, to justify the use of newly a developed treatment for cancer, to strengthen a business proposal, or to validate points made in a speech.

Why Is Secondary Research Important?

Because secondary research is used for so many purposes in so many settings, all professionals will be required to perform it at some point in their careers. For managers and entrepreneurs, regardless of the industry or profession, secondary research is a regular part of worklife, although parts of the research, such as finding the supporting documents, are often delegated to juniors in the organization. For all these reasons, it is essential to learn how to conduct secondary research, even if you are unlikely to ever conduct primary research.

Secondary research is also essential if your main goal is primary research. Research funding is obtained only by using secondary research to show the need for the primary research you want to conduct. In fact, primary research depends on secondary research to prove that it is indeed new and original research and not just a rehash or replication of somebody else’s work.

- Next: Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Dec 21, 2023 3:46 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.iit.edu/litreview

New NPM integration: design with fully interactive components from top libraries!

What is Desk Research? Definition & Useful Tools

Desk research typically serves as a starting point for design projects, providing designers with the knowledge to guide their approach and help them make informed design choices.

Make better design decisions with high-quality interactive UXPin prototypes. Sign up for a free trial to explore UXPin’s advanced prototyping features.

Build advanced prototypes

Design better products with States, Variables, Auto Layout and more.

What is Desk Research?

Desk research (secondary research or literature review) refers to gathering and analyzing existing data from various sources to inform design decisions for UX projects. It’s usually the first step in a design project as it’s cost-effective and informs where teams may need to dig deeper.

This data can come from published materials, academic papers, industry reports, online resources, and other third-party data sources. UX designers or researchers use this information to supplement data, learn about certain markets/user groups, explore industry trends, understand specific topics, or navigate design challenges.

The importance of desk research in the design process

Desk research gives designers a comprehensive understanding of the context, users, and existing solutions. It allows designers to gather valuable insights without conducting primary research which can be time-consuming and resource-intensive.

Desk research helps designers better understand the problem space, explore best practices and industry trends , and identify potential design opportunities without reinventing the wheel while learning from others’ mistakes.

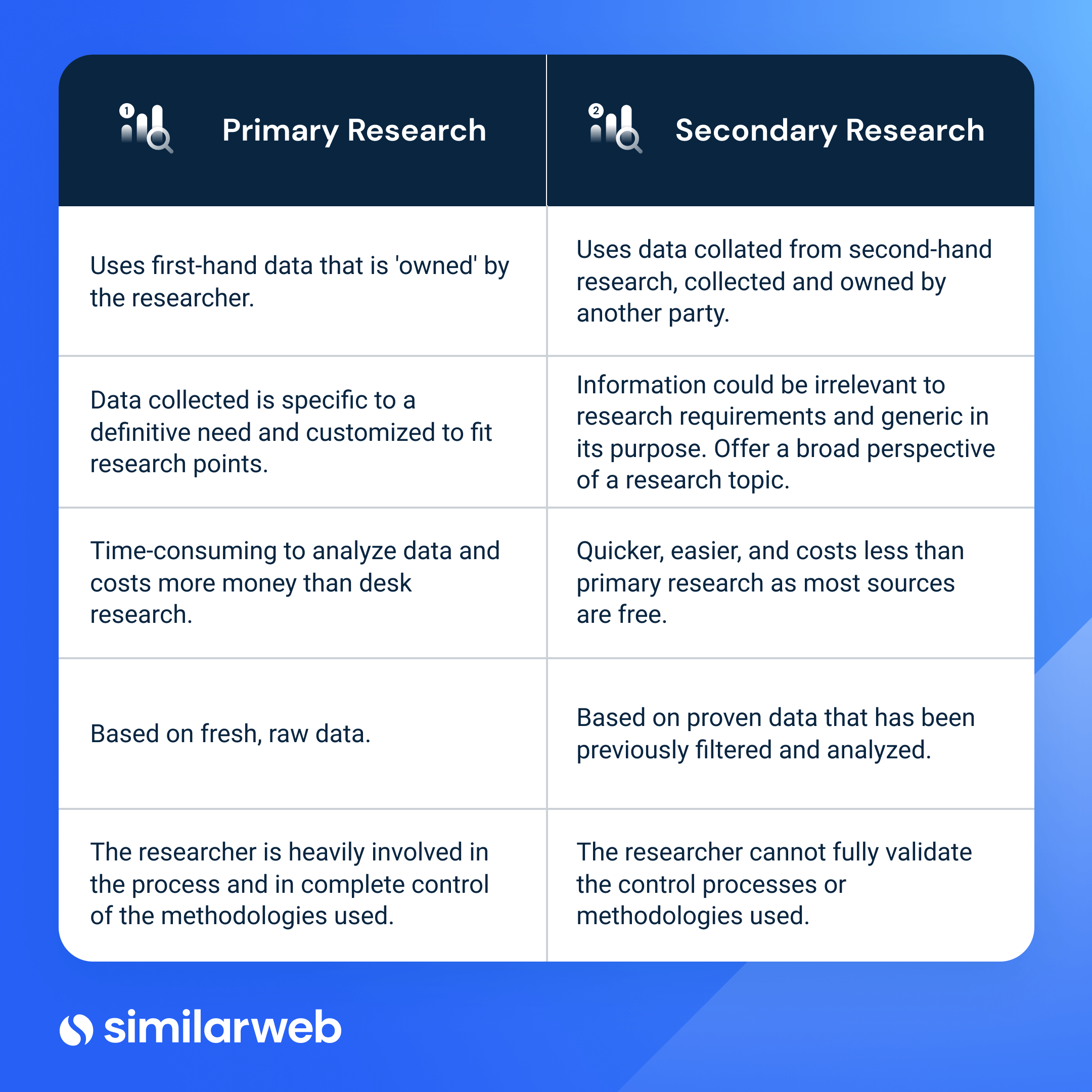

Primary Research vs. Secondary Research

- Primary research: new and original data from first-hand sources collected by the team, such as questionnaires, interviews, field research, or experiments, specifically for a particular research project.

- Secondary research: utilizing existing data sets and information that others have collected, including books, articles, reports, and databases.

Primary and secondary research complement each other in comprehensively understanding a topic or problem. While primary research provides new first-party data specifically for a project’s goals , secondary data leverages existing knowledge and resources to gain insights.

What is the Purpose of Desk Research?

Understanding the problem or design challenge

Desk research helps designers comprehensively understand the problem or design challenge. By reviewing existing knowledge and information, designers can grasp the context, identify pain points, and define the scope of their design project.

For example, when tasked with designing a new mobile banking app, desk research can provide insights into user preferences, common challenges in the banking industry, and emerging trends in mobile banking.

Gathering background information

Desk research allows designers to gather background information related to their design project. It helps them explore the domain, industry, target audience, and relevant factors that may influence their design decisions.

For example, when designing a fitness-tracking app, desk research may involve collecting information about fitness activities, wearable technologies, and health guidelines.

Exploring existing solutions and best practices

Desk research enables designers to explore existing solutions and best practices. By studying successful designs, case studies, and industry standards, designers can learn from previous approaches and incorporate proven techniques.

For example, when creating a website’s navigation menu , desk research can involve analyzing navigation patterns used by popular websites to ensure an intuitive user experience.

Identifying trends and patterns

Desk research helps designers identify trends and patterns within the industry or user behavior. Designers examine market reports, user surveys, and industry publications to identify trends, emerging technologies, and user preferences.

For example, when designing a smart home app, desk research can involve analyzing market trends in connected devices and user expectations for seamless integration.

Informing decision-making and design choices

Desk research provides designers valuable insights that inform their decision-making and design choices. It helps designers make informed design decisions based on existing knowledge, data, and research findings.

For example, when selecting a color palette for a brand’s website, desk research can involve studying color psychology, cultural associations, and industry trends to ensure the chosen colors align with the brand’s values and resonate with the target audience.

Secondary Research Methods and Techniques

Researchers use these methods individually or in combination, depending on the specific design project and research objectives. They select and adapt these based on the nature of the problem, available resources, and desired outcomes.

- Literature review : gathers and analyzes relevant data from academic and research publications, government agencies, educational institutions, books, articles, and online resources (i.e., Google Scholar, social media, etc.). It helps designers gain a deeper understanding of existing knowledge, theories, and perspectives on the subject matter.

- Market research : studying and analyzing market reports, industry trends, consumer behavior, and demographic data. It provides valuable insights into the target market, user preferences, emerging trends, and potential opportunities for design solutions.

- Competitor analysis : examines and evaluates the products, services, and strategies of competitors in the market. By studying competitors’ strengths, weaknesses, and unique selling points, designers can identify gaps, potential areas for improvement, and opportunities to differentiate their designs.

- User research analysis : User research analysis involves reviewing and analyzing data collected from various user research methods, such as surveys, interviews, and usability testing. It helps designers gain insights into user needs, preferences, pain points, and behaviors, which inform the design decisions and enhance the user-centeredness of the final product.

- Data analysis : processing and interpreting quantitative and qualitative data from various sources, such as surveys, analytics, and user feedback. It helps designers identify patterns, trends, and correlations in the data, which can guide decision-making and inform design choices.

How to Conduct Desk Research

Defining research objectives and questions

Start by defining the research objectives and formulating specific research questions. A clear goal will inform the type and method of secondary research.

For example, if you’re designing a mobile app for fitness tracking, your research objective might be to understand user preferences for workout-tracking features. Your research question could be: “What are the most commonly used workout tracking features in popular fitness apps?”

Identifying and selecting reliable sources

Identify relevant and reliable sources of information that align with your research objectives. These sources include academic journals, industry reports, reputable websites, and case studies.

For example, you might refer to academic journals and industry reports on fitness technology trends and user behavior to gather reliable insights for your research.

Collecting and analyzing relevant information

Collect information from the selected sources and carefully analyze it to extract key insights.

For example, you could collect data on user preferences for workout-tracking features by reviewing user reviews of existing fitness apps, analyzing market research reports, and studying user surveys conducted by fitness-related organizations.

Organizing and synthesizing findings

Organize the research data and synthesize the findings to identify common themes, patterns, and trends.

For example, you might categorize the collected data based on different workout tracking features, identify the most frequently mentioned features, and analyze user feedback to understand the reasons behind their preferences.

Limitations and Considerations of Secondary Research

Considering these desk research limitations and considerations allows designers to approach it with a critical mindset, apply appropriate methodologies to address potential biases, and supplement it with other research methods when necessary.

- Potential bias in sources: Desk research heavily relies on existing information, which may come from biased or unreliable sources. It is essential to critically evaluate the credibility and objectivity of the sources used to minimize the risk of incorporating biased information into the research findings.

- Limited access to certain information: Desk research may have limitations in accessing certain types of information, such as proprietary data or sensitive industry insights. This limited access can restrict the depth of the research and may require designers to rely on alternative sources or approaches to fill the gaps.

- Lack of real-time data: Desk research uses existing data and information, which may not always reflect the most up-to-date or current trends. It is essential to consider the data’s publication date and recognize that certain aspects of the research may require complementary methods, such as user research or market surveys, to capture real-time insights.

- Necessary cross-referencing and triangulation: Given the potential limitations and biases in individual sources, it is crucial to cross-reference information from multiple sources and employ triangulation techniques. This due diligence helps validate the findings and ensures a more comprehensive and accurate understanding of the subject matter.

Test Research Findings With UXPin’s Interactive Prototypes

Secondary research is the first step. Design teams must test and validate ideas with end-users using prototypes. With UXPin’s built-in design libraries , designers can build fully functioning prototypes using patterns and components from leading design systems, including Material Design, iOS, Bootstrap, and Foundation.

UXPin’s prototypes allow usability participants and stakeholders to interact with user interfaces and features like they would the final product, giving design teams high-quality insights to iterate and improve efficiency with better results.

These four key features set UXPin apart from traditional image-based design tools :

- States : create multiple states for a single UI element and design complex interactive components like dropdown menus , tab menus , navigational drawers , and more .

- Variables : create personalized, dynamic prototype experiences by capturing data from user inputs and using it throughout the prototype–like a personalized welcome message or email confirmation.

- Expressions : Javascript-like functions to create complex components and advanced functionality–no code required!

- Conditional Interactions : create if-then and if-else conditions based on user interactions to create dynamic prototypes with multiple outcomes to replicate the final product experience accurately.

Gain valuable insights with fully functioning prototypes to validate UX research hypotheses and make better design decisions. Sign up for a free trial to build your first interactive prototype with UXPin.

Build prototypes that are as interactive as the end product. Try UXPin

by UXPin on 3rd July, 2023

UXPin is a web-based design collaboration tool. We’re pleased to share our knowledge here.

UXPin is a product design platform used by the best designers on the planet. Let your team easily design, collaborate, and present from low-fidelity wireframes to fully-interactive prototypes.

No credit card required.

These e-Books might interest you

Design Systems & DesignOps in the Enterprise

Spot opportunities and challenges for increasing the impact of design systems and DesignOps in enterprises.

DesignOps Pillar: How We Work Together

Get tips on hiring, onboarding, and structuring a design team with insights from DesignOps leaders.

We use cookies to improve performance and enhance your experience. By using our website you agree to our use of cookies in accordance with our cookie policy.

- Desk Research: Definition, Types, Application, Pros & Cons

If you are looking for a way to conduct a research study while optimizing your resources, desk research is a great option. Desk research uses existing data from various sources, such as books, articles, websites, and databases, to answer your research questions.

Let’s explore desk research methods and tips to help you select the one for your research.

What Is Desk Research?

Desk research, also known as secondary research or documentary research, is a type of research that relies on data that has already been collected and published by others. Its data sources include public libraries, websites, reports, surveys, journals, newspapers, magazines, books, podcasts, videos, and other sources.

When performing desk research, you are not gathering new information from primary sources such as interviews, observations, experiments, or surveys. The information gathered will then be used to make informed decisions.

The most common use cases for desk research are market research , consumer behavior , industry trends , and competitor analysis .

How Is Desk Research Used?

Here are the most common use cases for desk research:

- Exploring a new topic or problem

- Identifying existing knowledge gaps

- Reviewing the literature on a specific subject

- Finding relevant data and statistics

- Analyzing trends and patterns

- Evaluating competitors and market trends

- Supporting or challenging hypotheses

- Validating or complementing primary research

Types of Desk Research Methods

There are two main types of desk research methods: qualitative and quantitative.

- Qualitative Desk Research

Analyzing non-numerical data, such as texts, images, audio, or video. Here are some examples of qualitative desk research methods:

Content analysis – Examining the content and meaning of texts, such as articles, books, reports, or social media posts. It uses data to help you identify themes, patterns, opinions, attitudes, emotions, or biases.

Discourse analysis – Studying the use of language and communication in texts, such as speeches, interviews, conversations, or documents. It helps you understand how language shapes reality, influences behavior, constructs identities, creates power relations, and more.

Narrative analysis – Analyzing the stories and narratives that people tell in texts, such as biographies, autobiographies, memoirs, or testimonials. This allows you to explore how people make sense of their experiences, express their emotions, construct their identities, or cope with challenges.

- Quantitative Desk Research

Analyzing numerical data, such as statistics, graphs, charts, or tables.

Here are common examples of quantitative desk research methods:

Statistical analysis : This method involves applying mathematical techniques and tools to numerical data, such as percentages ratios, averages, correlations, or regressions.

You can use statistical analysis to measure, describe, compare, or test relationships in the data.

Meta-analysis : Combining and synthesizing the results of multiple studies on a similar topic or question. Meta-analysis can help you increase the sample size, reduce the margin of error, or identify common findings or discrepancies in data.

Trend analysis : This method involves examining the changes and developments in numerical data over time, such as sales, profits, prices, or market share. It helps you identify patterns, cycles, fluctuations, or anomalies.

Examples of Desk Research

Here are some real-life examples of desk research questions:

- What are the current trends and challenges in the fintech industry?

- How do Gen Z consumers perceive money and financial services?

- What are the best practices for conducting concept testing for a new fintech product?

- Documentary on World War II and its effect on Austria as a country

You can use the secondary data sources listed below to answer these questions:

Industry reports and publications

- Market research surveys and studies

- Academic journals and papers

- News articles and blogs

- Podcasts and videos

- Social media posts and reviews

- Government and non-government agencies

How to Choose the Best Type of Desk Research

The main factors for selecting a desk research method are:

- Research objective and question

- Budget and deadlines

- Data sources availability and accessibility.

- Quality and reliability of data sources

- Your data analysis skills

Let’s say your research question requires an in-depth analysis of a particular topic, a literature review may be the best method. But if the research question requires analysis of large data sets, you can use trend analysis.

Differences Between Primary Research and Desk Research

The main difference between primary research and desk research is the source of data. Primary research uses data that is collected directly from the respondents or participants of the study. Desk research uses data that is collected by someone else for a different purpose.

Another key difference is the cost and time involved. Primary research is usually more expensive, time-consuming, and resource-intensive than desk research. However, it can also provide you with more specific, accurate, and actionable data that is tailored to your research goal and question.

The best practice is to use desk-based research before primary research; it refines the scope of the work and helps you optimize resources.

Read Also – Primary vs Secondary Research Methods: 15 Key Differences

How to Conduct a Desk Research

Here are the four main steps to conduct desk research:

- Define Research Goal and Question

What do you want to achieve with your desk research? What problem do you want to solve or what opportunity do you want to explore? What specific question do you want to answer with your desk research?

- Identify and Evaluate Data Sources

Where can you find relevant data for your desk research? How relevant and current are the data sources for your research? How consistent and comparable are they with each other?

You can evaluate your data sources based on factors such as-

– Authority: Who is the author or publisher of the data source? What are their credentials and reputation? Are they experts or credible sources on the topic?

– Accuracy: How accurate and precise is the data source? Does it contain any errors or mistakes? Is it supported by evidence or references?

– Objectivity: How objective and unbiased is the data source? Does it present facts or opinions? Does it have any hidden agenda or motive?

– Coverage: How comprehensive and complete is the data source? Does it cover all aspects of your topic? Does it provide enough depth and detail?

– Currency: How current and up-to-date is the data source? When was it published or updated? Is it still relevant to your topic?

- Collect and Analyze Your Data

How can you collect your data efficiently and effectively? What tools or techniques can you use to organize and analyze your data? How can you interpret your data with your research goal and question?

- Present and Report Your Findings

How can you communicate your findings clearly and convincingly? What format or medium can you use to accurately record your findings?

You can use spreadsheets, presentation slides, charts, infographics, and more.

Advantages of Desk Research

- Cost Effective

It is cheaper and faster than primary research, you don’t have to collect new data or report them. You can simply analyze and leverage your findings to make deductions.

- Prevents Effort Duplication

Desk research provides you with a broad and thorough overview of the research topic and related issues. This helps to avoid duplication of efforts and resources by using existing data.

- Improves Data Validity

Using desk research, you can compare and contrast various perspectives and opinions on the same topic. This enhances the credibility and validity of your research by referencing authoritative sources.

- Identify Data Trends and Patterns

It helps you to identify new trends and patterns in the data that may not be obvious from primary research. This can help you see knowledge and research gaps to offer more effective solutions.

Disadvantages of Desk Research

- Outdated Information

One of the main challenges of desk research is that the data may not be relevant, accurate, or up-to-date for the specific research question or purpose. Desk research relies on data that was collected for a different reason or context, which may not match the current needs or goals of the researcher.

- Limited Scope

Another limitation of desk research is that it may not provide enough depth or insight into qualitative aspects of the market, such as consumer behavior, preferences, motivations, or opinions.

Data obtained from existing sources may be biased or incomplete due to the agenda or perspective of the source.

Read More – Research Bias: Definition, Types + Examples

- Data Inconsistencies

It may also be inconsistent or incompatible with other data sources due to different definitions or methodologies.

- Legal and Technical Issues

Desk research data may also be difficult to access or analyze due to legal, ethical, or technical issues.

How to Use Desk Research Effectively

Here are some tips on how to use desk research effectively:

- Define the research problem and objectives clearly and precisely.

- Identify and evaluate the sources of secondary data carefully and critically.

- Compare and contrast different sources of data to check for consistency and reliability.

- Use multiple sources of data to triangulate and validate the findings.

- Supplement desk research with primary research when exploring deeper issues.

- Cite and reference the sources of data properly and ethically.

Desk research should not be used as a substitute for primary research, but rather as a complement or supplement. Combine it with primary research methods, such as surveys, interviews, observations, experiments, and others to obtain a more complete and accurate picture of your research topic.

Desk research is a cost-effective tool for gaining insights into your research topic. Although it has limitations, if you choose the right method and carry out your desk research effectively, you will save a lot of time, money, and effort that primary research would require.

Connect to Formplus, Get Started Now - It's Free!

- desk research

- market research

- primary vs secondary research

- research bias

- secondary research

- Moradeke Owa

You may also like:

Projective Techniques In Surveys: Definition, Types & Pros & Cons

Introduction When you’re conducting a survey, you need to find out what people think about things. But how do you get an accurate and...

What is Thematic Analysis & How to Do It

Introduction Thematic Analysis is a qualitative research method that plays a crucial role in understanding and interpreting data. It...

Judgmental Sampling: Definition, Examples and Advantages

Introduction Judgment sampling is a type of non-random sampling method used in survey research and data collection. It is a method in...

25 Research Questions for Subscription Pricing

After strategically positioning your product in the market to generate awareness and interest in your target audience, the next step is...

Formplus - For Seamless Data Collection

Collect data the right way with a versatile data collection tool. try formplus and transform your work productivity today..

Just one more step to your free trial.

.surveysparrow.com

Already using SurveySparrow? Login

By clicking on "Get Started", I agree to the Privacy Policy and Terms of Service .

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Don't miss the future of CX at RefineCX USA! Register Now

Enterprise Survey Software

Enterprise Survey Software to thrive in your business ecosystem

NPS® Software

Turn customers into promoters

Offline Survey

Real-time data collection, on the move. Go internet-independent.

360 Assessment

Conduct omnidirectional employee assessments. Increase productivity, grow together.

Reputation Management

Turn your existing customers into raving promoters by monitoring online reviews.

Ticket Management

Build loyalty and advocacy by delivering personalized support experiences that matter.

Chatbot for Website

Collect feedback smartly from your website visitors with the engaging Chatbot for website.

Swift, easy, secure. Scalable for your organization.

Executive Dashboard

Customer journey map, craft beautiful surveys, share surveys, gain rich insights, recurring surveys, white label surveys, embedded surveys, conversational forms, mobile-first surveys, audience management, smart surveys, video surveys, secure surveys, api, webhooks, integrations, survey themes, accept payments, custom workflows, all features, customer experience, employee experience, product experience, marketing experience, sales experience, hospitality & travel, market research, saas startup programs, wall of love, success stories, sparrowcast, nps® benchmarks, learning centre, apps & integrations, testimonials.

Our surveys come with superpowers ⚡

Blog General

Desk Research 101: Definition, Methods, and Examples

Parvathi vijayamohan.

2 March 2023

Table Of Contents

If you ever had to do a research study or a survey at some point, you would have started with desk research .

There’s another, more technical name for it – secondary research. To rewind a bit, there are two types of research: primary , where you go out and study things first-hand, and secondary , where you explore what others have done.

But what is desk research? How do you do it, and use it? This article will help you:

- Understand what is desk-based research

- Explore 3 examples of desk research

- Make note of 6 common desk research methods

- Uncover the advantages of desk research

What is desk research?

Desk research can be defined as a type of market/product research, where you collect data at your desk (metaphorically speaking) from existing sources to get initial ideas about your research topic.

Desk research or secondary research is an essential process from a business’s point of view. After all, secondary data sources are such an easy way to get information about their industry, trends, competitors, and customers.

Types of secondary data sources

#1. Internal secondary data: This consists of data from within the researcher’s company. Examples include:

- Company reports and presentations

- Case studies

- Podcasts, vlogs and blogs

- Press releases

- Websites and social media

- Company databases and data sets

#2. External secondary data: Researchers collect this from outside their respective firms. Examples include:

- Digital and print publications

- Domain-specific publications and periodicals

- Online research communities, like ResearchGate

- Industry speeches and conference presentations

- Research papers

What are examples of desk research in action?

#1. testing product-audience match.

Let’s say you’re developing a fintech product. You want to do a concept testing study. To make sure you get it right, you’re interested in finding out your target audience’s attitudes about a topic in your domain. For e.g., Gen Z’s perceptions about money in the US.

With a quick Google search, you get news articles, reports, and research studies about Gen Z’s financial habits and attitudes. Also, infographics and videos provide plenty of quantitative data to draw on.

These steps are a solid starting point for framing your concept testing study. You can further reduce the time spent on survey design with a Concept Testing Survey Template . Sign up to get free access to this and hundreds more templates.

Please enter a valid Email ID.

14-Day Free Trial • No Credit Card Required • No Strings Attached

#2. Tracking the evolution of the Web

As we wade into the brave new world of Web 5.0 , there are quite a few of us who still remember static websites, flash animations, and images sliced up into tables.

If you want to refresh your memory, you can hop on the Wayback Machine . iI gives you access to over 20 years of web history, with over 635 billion web pages saved over time!

Curiosity aside, there are practical use cases for this web archive. SEO specialist Artur Bowsza explores this in his fantastic article Internet Archeology with the Wayback Machine .

Imagine you’re investigating a recent drop in a website’s visibility. You know there were some recent changes in the website’s code, but couldn’t get any details. Or maybe you’re preparing a case study of your recent successful project, but the website has changed so much, and you never bothered to take a screenshot. Wouldn’t it be great to travel back in time and uncover the long-forgotten versions of the website – like an archaeologist, discovering secrets from the past but working in the digital world?

#3. Repairing a business reputation

As a brand, you hope that a crisis never happens. But if hell does break loose, having a crisis management strategy is essential.

If you want examples, just do a Google search. From Gamestop getting caught in a Reddit stock trading frenzy to Facebook being voted The Worst Company of 2021 , we have seen plenty of brands come under fire in recent years.

Some in-depth desk research can help you nail your crisis communication. Reputation management expert Lida Citroen outlines this in her article 7 Ways to Recover After a Reputation Crisis .

Conduct a thoughtful and thorough perception sweep of the reputation hit’s after-effects. This includes assessing digital impact such as social media, online relationships and Google search results. The evaluation gives you a baseline. How serious is the situation? Sometimes the way we believe the situation to be is not reflected in the business impact of the damage.

6 popular methods of desk research

#1. the internet.

No surprise there. When was the last time you checked a book to answer the burning question of “is pineapple on pizza illegal?” (it should be).

However, choosing authentic and credible sources from an information overload can be tricky. To help you out, the Lydia M. Olson Library has a 6-point checklist to filter out low-quality sources. You can read them in detail here .

#2. Libraries

You have earned some serious street cred if your preferred source is a library. But, jokes apart, finding the correct information for your research topic in a library can be time-consuming.

However, depending on which library you visit, you will find a wealth of verifiable, quotable information in the form of newspapers, magazines, research journals, books, documents, and more.

#3. Governmental and non-governmental organizations

NGOs, and governmental agencies like the US Census Bureau, have valuable demographic data that businesses can use during desk research. This data is collected using survey tools like SurveySparrow .

You may have to pay a certain fee to download or access the information from these agencies. However, the data obtained will be reliable and trustworthy.

#4. Educational institutions

Colleges and universities conduct plenty of primary research studies every year. This makes them a treasure trove for desk researchers.

However, getting access to this data requires legwork. The procedures vary according to the institution; among other things, you will need to submit an application to the relevant authority and abide by a data use agreement.

#5. Company databases

For businesses, customer and employee data are focus areas all on their own. But after the pandemic, companies are using even more applications and tools for the operations and service sides.

This gives businesses access to vast amounts of information useful for desk research and beyond. For example, one interesting use case is making employee onboarding more effective with just basic employee data, like their hobbies or skills.

#6. Commercial information media

These include radio, newspapers, podcasts, YouTube, and TV stations. They are decent sources of first-hand info on political and economic developments, market research, public opinion and other trending subjects.

However, this is also a source that blurs the lines between advertising, information and entertainment. So as far as credibility is concerned, you are better off supporting this data with additional sources.

Why is desk research helpful?

Desk research helps with the following:

- Better domain understanding. Before doing market research, running a usability test, or starting any user-centric project, you want to see what companies have done in the past (in related areas if not the same domain). Then, instead of learning everything from scratch, you can review their research, success, and mistakes and learn from that.

- Quicker opportunity spotting. How do you know if you’ve found something new? By reviewing what has gone before. By doing this, you can spot gaps in the data that match up with the problem you’re trying to solve.

- More money saved . Thanks to the internet, most of the data you need is at your fingertips, and they are cheaper to compile than field data. With a few (search and mental) filters, you can quickly find credible sources with factual information.

- More time saved . You have less than 15 minutes with your research participant. Two minutes if you’re doing an online survey. Do you really want to waste that time asking questions that have already been answered elsewhere? Lack of preparation can also hurt your credibility.

- Better context. Desk research helps to provide focus and a framework for primary research. By using desk research, companies can also get the insight to make better decisions about their customers and employees.

- More meaningful data. Desk research is the yin to the yang of field research – they are both required for a meaningful study. That’s why desk research serves as a starting point for every kind of study.

This brings us to the last question.

How do you do desk research?

Good question! In her blog post , Lorène Fauvelle covers the desk research process in detail.

Y ou can also follow our 4-step guide below:

- First, start with a general topic l ike “handmade organic soaps”. Read through existing literature about handmade soaps to see if there is a gap in the literature that your study can fill.

- Once you find that gap, it’s time to specify your research topic . So in the example above, you can specify it like this: “What is the global market size for handmade organic soaps”?

- Identify the relevant secondary data for desk research. This only applies if there is past data that could be useful for your research.

- Review the secondary data according to:

- The aim of the previous study

- The author/sponsors of the study

- The methodology of the study

- The time of the research

Note: One more thing about desk research…

Beware of dismissing research just because it was done a few years ago. People new to research often make the mistake of viewing research reports like so many yogurts in a fridge where the sell-by dates have expired. Just because it was done a couple of years ago, don’t think it’s no longer relevant. The best research tends to focus on human behaviour, and that tends to change very slowly.

- Dr David Travis, Desk Research: The What, Why and How

Wrapping up

That’s all folks! We hope this blog was helpful for you.

How have you used desk research for your work? Let us know in the comments below.

Growth Marketer at SurveySparrow

Fledgling growth marketer. Cloud watcher. Aunty to a naughty beagle.

You Might Also Like

How to create an ecommerce website – a comprehensive guide, 10 best hipaa compliant forms | form builders for your business, 10 must-have mailchimp integrations for marketers.

Leave us your email, we wont spam. Promise!

Start your free trial today

No Credit Card Required. 14-Day Free Trial

Power your desktop research with stunning surveys

Don't rely on the past alone. get insights into the future with powerful feedback software. try surveysparrow for free..

14-Day Free Trial • No Credit card required • 40% more completion rate

Hi there, we use cookies to offer you a better browsing experience and to analyze site traffic. By continuing to use our website, you consent to the use of these cookies. Learn More

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Desk Research: What it is, Tips & Examples

What is desk research?

Desk research is a type of research that is based on the material published in reports and similar documents that are available in public libraries, websites, data obtained from surveys already carried out, etc. Some organizations also store data that can be used for research purposes.

It is a research method that involves the use of existing data. These are collected and summarized to increase the overall effectiveness of the investigation.