How to Teach Divergent Thinking Skills in the Classroom

- December 21, 2020

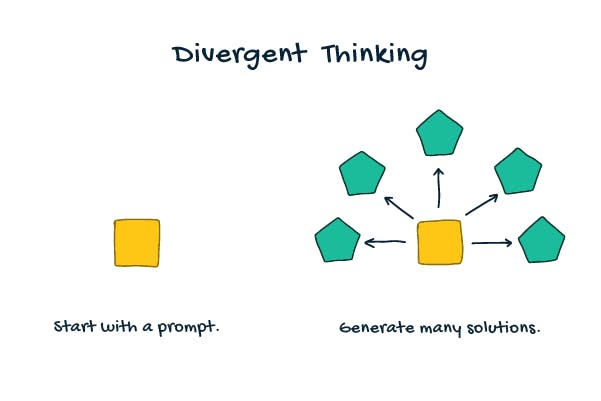

To solve a problem they are struggling with, some students need only to “think outside the box.” This tactic is called divergent thinking, and it gets students to come up with several answers to a question and decide which is the best, most useful one.

Read on to take a look at divergent thinking, why it’s important, and how it differs from its opposite, convergent thinking. Then, discover a few strategies for helping students strengthen and maintain their divergent thinking skills.

What is Divergent Thinking?

Although divergent thinking is not synonymous with creativity—here defined as the ability to have new ideas or make something new—the two skills are closely related.[3] Divergent thinking can lead to creativity as students come up with more unique solutions. Likewise, encouraging creativity in your students can lead them to consider divergent answers to their problems.

Studies also suggest that, as a whole, children have stronger divergent thinking skills than adults. For example, children are better at visualizing divergent ideas than adults. In fact, a person’s ability to think divergently decreases with age. It could be argued that teaching divergent thinking to students is less about teaching a new skill and more about maintaining it.

Divergent Thinking vs. Convergent Thinking

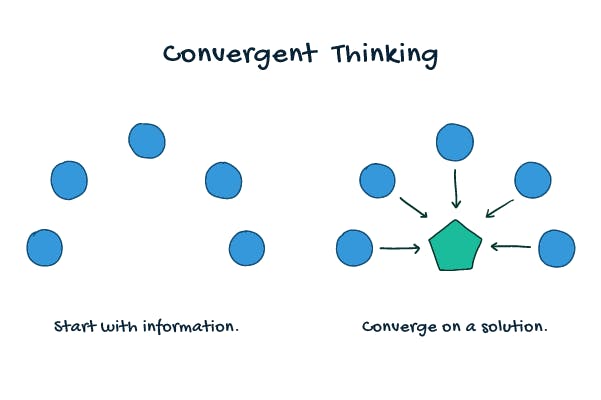

It’s important not to confuse divergent thinking with convergent thinking, a problem-solving strategy that is more often taught in schools. Convergent thinking encourages students to come up with one distinct answer to a question based on the information given to them.[6] After they have come up with this solution, they stop and do not come up with others.

Convergent thinking is not necessarily a negative thinking strategy. In some situations, there may be one answer to a question (though there likely isn’t only one way to get that answer). But in general, teaching divergent thinking over its convergent counterpart will help students solve problems more creatively and effectively.

Divergent Thinking Boosts Problem-Solving and Student Success

Divergent thinking can also help students become more open-minded, a crucial social-emotional skill.[4] As students learn to think about a topic from new angles, they’ll be able to consider ideas from beyond their own experiences. This can help them broaden their perspective and better understand people whose ideas differ from their own.

Additionally, divergent thinking strategies teach students how to problem solve.[2] Instead of stopping at the quickest, easiest, or most obvious solution, students spend time thinking of many different answers. That way, they learn to prioritize finding an effective solution over a fast one.

The younger a student is, the easier divergent thinking may come to them. For example, 90% of kindergarteners ranked at the “genius” level for divergent thinking in a study conducted by the Royal Society of Medicine.[14] If you can nurture this skill early in a student’s academic journey, you can help them maintain skills that will benefit them for their entire life.

Strategies to Encourage Divergent Thought in Schools

One simple yet effective way to help students think divergently is by asking open-ended questions.[12] Open-ended questions are defined as ones that cannot be answered by “yes” or “no.” The more open a question is, the more likely students will be able to come up with many different answers.

These open-ended question examples from the Coeur d’Alene Public School District can help you get started as you structure your lesson plans:

- What were the major effects of World War II for the United States?

- What is your favorite memory from childhood?

- What makes the leaves change color?

In class, encourage students to focus more on the learning process, and not on the answer.[16] If students worry too much about finding the “right” answer, they may hurry and choose their first answer. But if they spend a little more time on a question, they may think of a better one.

Additionally, teach your students to view failures as a positive rather than a negative experience.[10] Making mistakes provides learning experiences that can help students move toward a more successful solution. If a student is struggling with a project, praise them for working hard and encourage them to try again from another angle.

And finally, make sure to include time for creative play in your classroom. Studies show that playing pretend, for example, is linked to stronger divergent thinking skills in young students.[5] Assign students projects that allow them to use their imagination and play as they complete it. You could, for example, assign students an art project or have them perform a skit in small groups.

5 Quick Tips to Teach Students Divergent Thinking Skills

It’s crucial to encourage divergent thinking in schools in order to help students thrive. By thinking outside of the box, your students will come up with better and more thoughtful solutions.

These five quick and simple tips will help you move towards divergent thinking in the classroom.

1. Journaling is a great way to encourage self-analysis and help students think through many solutions to a question.[13] Assign students to keep a journal and ask them thought-provoking questions .

For earlier grades, journaling may involve more drawing and early attempts to write than full sentences.

2. Include free play in your curriculum, which is when students can work on projects of their own choosing.[11]

3. Ask students open-ended questions that cannot be answered with one solution.[8] You could, for example, ask what they believe makes life meaningful or how they would solve a global issue.

4. Brainstorming is a great example of a divergent thinking strategy. If a student is stuck on an assignment, encourage them to brainstorm answers or solutions—either on their own or with their classmates. Through brainstorming, students are taught to consider a variety of solutions instead of just one.[6]

5. Play this Animal Soup Activity to teach students how to come up with many outcomes to a situation.

- Runco, M.A., and Acar, S. Divergent Thinking as an Indicator of Creative Potential . Creativity Research Journal, 2012, 24(1), pp. 66-75.

- Vincent, A.S., Decker, B.P., and Mumford, M.D. Divergent Thinking, Intelligence, and Expertise: A Test of Alternative Models . Creativity Research Journal, 2002, 14(2), pp. 163-178.

- Runco, M. A. Commentary: Divergent thinking is not synonymous with creativity . Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 2008, 2(2), 93–96.

- Goodman, S. Fuel Creativity in the Classroom With Divergent Thinking . March 2014. Edutopia. https://www.edutopia.org/blog/fueling-creativity-through-divergent-thinking-classroom-stacey-goodman

- Hadani, H.S. The Creativity Issue: Why Imaginative Play in Early Childhood Could be the Key to Creativity in Adulthood . Toca Magazine. tocaboca.com/magazine/creativity-issue_imaginary-play/.

- Nelson-Danley, K. How to Teach Divergent Thinking . Teach Hub. July 2020. https://www.teachhub.com/teaching-strategies/2020/07/how-to-teach-divergent-thinking/

- Palmiero, M., Di Giacomo, D., and Passafiume, D. Divergent Thinking and Age-Related Changes . Creativity Research Journal, 2014, 26(4), pp 456-460.

- Amico, B. Crucial Creativity: The Case for Cultivating Divergent Thinking in Classrooms . Waldorf Education. February 2020. https://www.waldorfeducation.org/news-resources/essentials-in-education-blog/detail/~board/essentials-in-ed-board/post/crucial-creativity-the-case-for-cultivating-divergent-thinking-in-classrooms.

- Guido, M. How to Teach Convergent and Divergent Thinking: Definitions, Examples, Templates and More . Prodigy. July 2018. https://www.prodigygame.com/main-en/blog/convergent-divergent-thinking/.

- Briggs, S. 30 Ways to Inspire Divergent Thinking . InformED. June 2014. https://www.opencolleges.edu.au/informed/features/divergent-thinking/.

- Iannelli, V. The Importance of Free Play for Kids . Verywell Family. March 2020. https://www.verywellfamily.com/the-importance-of-free-play-2633113.

- Hughes, D. Activities that Inspire Divergent Thinking . https://study.com/academy/lesson/activities-that-inspire-divergent-thinking.html.

- University of Washington Staff. Strategies of Divergent Thinking . https://faculty.washington.edu/ezent/imdt.htm.

- Abbasi, K. A riot of divergent thinking . Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, October 2011, 104(10), pp. 391.

- Lewis, C., and Lovatt, P.J. Breaking away from set patterns of thinking: Improvisation and divergent thinking . Thinking Skills and Creativity, August 2013, 9, pp. 46-58.

- O’Byrne, W.I. Understanding key differences between divergent & convergent thinking . November 2017. https://wiobyrne.com/divergent-convergent/.

- Cohut, M. What are the health benefits of being creative? Medical News Today. February 2018. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/320947.

More education articles

Phonics vs Phonological Awareness: A Guide Informed by the Science of Reading

Among the six key skills needed for literacy development, two are commonly used interchangeably: phonics and phonological awareness. While their names sound similar, they are

Six Picture Books & Chapter Book Guides to Celebrate Black History Month with Young Students

February marks Black History Month, a dedicated observance of the achievements, heritage, and contributions of Black Americans. It can also be an opportunity to find

Children’s Books for Celebrating Women’s History Month in Class

Women’s History Month, observed each March, is a dedicated time to honor the accomplishments, resilience, and contributions of women. For elementary teachers, this month provides

Ideas to Celebrate National Library Week and Encourage a Young Writer Day 2024

MacKenzie Scott’s Yield Giving Awards Waterford.org a $10 Million Grant

End Bullying: October is National Bullying Prevention Month

- Our Mission

Fuel Creativity in the Classroom With Divergent Thinking

Teachers can inspire outside-the-box thinking for students by using problem-based learning, art, music, and inquiry-based feedback.

Recently, I showed a group of students in my high school art class a film called Ma Vie En Rose ( My Life in Pink ), about a 7-year-old boy named Ludovic who identifies as female. Ludovic has an active imagination, but is bullied by both adults and other kids who are unnerved by his desire to wear dresses and play with dolls. The film challenged my students to broaden their understanding of gender and identity and led to a discussion about ways in which our imaginations are limited when we are forced to be who we are not. It reminded me of other stories in which a character is forced to choose an identity, such as the movie Divergent , based on the popular trilogy of novels by Veronica Roth.

In Divergent , a dystopian future society has been divided into five factions based on perceived virtues. Young people are forced to choose a faction as a rite of passage to becoming an adult. Tris, the story’s female hero, knows that choosing a faction might mean being cut off from family and friends forever, and wonders if she truly belongs to any one faction at all. Like Ludovic, Tris feels compelled to hide who she is, and knows that her behavior and ways of thinking might put herself and family at risk. Tris also knows that the most dangerous people in her society are considered those whose thinking is unrestricted and cannot be easily categorized—those people are called divergent.

Defining Divergent Thinking

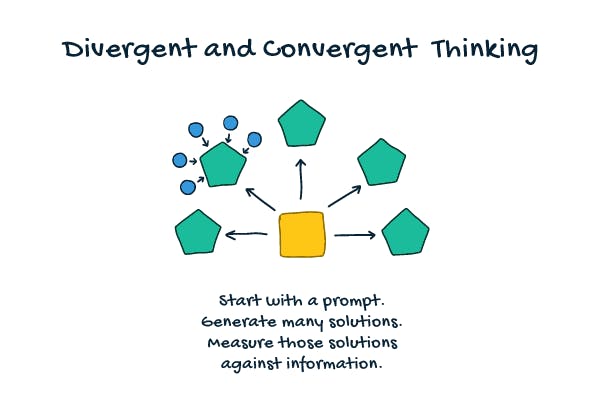

The word divergent is partly defined as “tending to be different or develop in different directions.” Divergent thinking refers to the way the mind generates ideas beyond proscribed expectations and rote thinking—what is usually referred to thinking outside the box, and is often associated with creativity. Convergent thinking, on the other hand, requires one to restrict ideas to those that might be correct or the best solution to a problem.

Studies suggest that, as children, our divergence capability is high, and decreases dramatically as we become adults. Perhaps this is as it should be to a certain degree, and as teachers and adults we would be concerned if our middle and high school students extended imaginative play into everyday life in the way a 4-year-old does. Yet many teachers at some point in their teaching career become frustrated by their students’ inability to think creatively, and others—exemplified by Sir Ken Robinson —blame schooling itself for killing the imagination.

Divergent behavior is discouraged in school when students are scared to say or do the “wrong thing” in class. This is not surprising since schools often tolerate environments in which both teachers and peer groups keep in check those who say and do things that are off-script, incorrect, or inappropriate. This system of overt convergence is enforced by a grading culture that systematically penalizes students for being “wrong,” and by allowing a school environment in which students tease those who exhibit non-normative behaviors. So if divergent thinking is key to being creative, it becomes clear why our students find being open with their imaginations and divergent ideas inhibited.

It must be said that there are valid reasons why divergent thinking is discouraged in our classrooms. Divergent thinking treats all ideas equally regardless of context or applicability and disregards rubrics, criteria, or any process for assessment. There are also situations when divergent behavior might actually cause physical harm, such as in chemistry class or on the playground, and we expect our students to display good judgment, or convergent thinking strategies, so that they can make correct decisions.

Teachers also might find divergent thinking and behavior a challenge when students ignore directions and rules, and, if we’re honest with ourselves, display personality traits that operate outside societal norms. These non-normative students, kids like the character Ludovic, who are transgender or who identify as atheists, for example, might be considered divergent in many of our communities. It’s up to us as school administrators and teachers to ensure that good judgment extends beyond what might be considered current social norms and take into account what’s best for our students’ spirits, humanity, and ultimate sense of belonging.

In the Classroom: Strategies

Ideally, divergent and convergent thinking work in harmony with each other. The geneplore model diagrams this relation between divergent, generative thinking and evaluative, convergent thinking. Helping our students understand these strategies and how they complement each other also encourages metacognitive learning so that students better understand their own thinking and creative abilities.

As an art teacher, my job is to foster an environment for creative work, and I believe the following five strategies might be useful for non-art teachers as well.

1. Reversing the question/answer paradigm: Problem-based learning is derived from an approach developed for training medical students in Canada but has since been used in K–12 education and other project-based learning environments. The premise of it is simple: Instead of asking questions to which there is a correct answer, ask students to create the problem.

Students pose their problem by first tapping into their own wishes and goals that might have real-life results or be largely theoretical and in end in the modeling stages. Questions like “How can we grow vegetables without using pesticides?” and “How can we feed the world’s population in a sustainable way?” encourage students to think divergently.

2. Let the music play: In my classroom, students serve as guest DJs and play their music when we're in the studio mode of our projects. I love the atmosphere music creates. I also know how “tribal” adolescents often see each other in terms of musical taste, so I introduce the guest DJ at the beginning of the term as a strategy for setting norms in the classroom in order to create an environment in which judgment of each other is deferred, restrained, and more thoughtful.

When students learn to defer judgment, the learning environment becomes open to other influences and ideas. When we’re not afraid of being immediately judged by our taste, we’re more likely to share ideas and opinions, and therefore become less afraid to be divergent in our thinking and behavior.

3. Inquiry-based feedback: Instead of value-based feedback, inquiry coupled with deep observation encourages a more open-ended and in-depth approach for evaluating students’ work. Students are encouraged to minimize expressing their likes and dislikes, and to first spend at least two minutes silently observing, and then asking questions prefixed by phrases such as, “I noticed that _____,” “Why did you _____,” and “How _____.”

4. Encourage play and manage failure: When failure is framed more by reflection and iteration, and less by penalty and closure, we’re more likely to loosen up in our efforts and be less afraid to make mistakes. Then we can open up the environment for play and experimentation.

In my community art class, I prepare students to take risks in their projects by creating one-day exercises in which they engage with the public in a safe but unpredictable way. One example involves asking other students outside of class to have their photo taken. The scary aspect of being rejected is overcome, and students gain courage to open up and take risks. If rejection does occur, students have time to reflect and strategize in preparation for scaling up their ideas or projects.

5. Using art strategies: I use a few art strategies such as collage, readymade, and pareidolia to open up the divergent thinking part of the students’ brains. They become less concerned about exact interpretation and more open to poetry, metaphor, and dream imagery in general.

- Collage : When artfully done, brings disparate images together and finds relationships based on aesthetics, absurdity, or spatial arrangements—not their literal meaning or function in the real world. Once the images are de-coupled from their literal roles, this opens up to nonlinear thinking in general.

- Readymade : This involves taking ordinary objects and playfully renaming what they are or reimagining how they function. Marcel Duchamp had a famous example: taking a urinal, flipping it upside down, and calling it Fountain . I ask my students to do the same with ordinary objects around them—using the material, shape, or alternative functions of an object, they reimagine it.

- Pareidolia : A phenomenon of looking at an object and finding a semblance of something else that’s not really there, like seeing a dragon in the shape of a cloud, or noticing that a three-prong power outlet looks like a face. I show students the short animated film The Deep by the artist Pes, in which ordinary objects are turned into mysterious sea creatures. I then ask them to take photos of examples of pareidolia around them. They have fun reinterpreting the world.

Divergent thinking strategies offer the possibility of doing more than fostering a creative classroom environment—they can also help us better understand and appreciate difference in all areas of our students’ lives. Young people like the fictional characters Ludovic and Tris might then find a world that’s more accepting, and we could benefit from the creative possibilities when young people are allowed to be who they are.

- Prodigy Math

- Prodigy English

From our blog

- Is a Premium Membership Worth It?

- Promote a Growth Mindset

- Help Your Child Who's Struggling with Math

- Parent's Guide to Prodigy

- Assessments

- Math Curriculum Coverage

- English Curriculum Coverage

- Game Portal

How to Teach Convergent and Divergent Thinking: Definitions, Examples, Templates and More

Written by Marcus Guido

Did you know?

Students at one school district mastered 68% more math skills on average when they used Prodigy Math.

- Teaching Strategies

The definitions of convergent and divergent thinking

- Examples of questions

- Tips for creating your own questions

- Prompting students to use each style of thinking

Not all problems require the same approach.

For many students, knowing how to tackle certain problems starts by recognizing when to apply convergent and divergent thinking.

To help you effectively teach and reinforce these strategies, read through it, and then reference it as you integrate both thinking methods into your lessons.

Convergent and divergent thinking are opposites, but both have places in your daily lessons.

American psychologist JP Guilford coined the terms in the 1950s, which take their names from the problem solving processes they describe.

Convergent thinking involves starting with pieces of information, converging around a solution.

As you can infer, it emphasizes finding the single, optimal solution to a given problem and usually demands thinking at the first or second Depth of Knowledge (DoK) level.

Determining the correct answer to a multiple choice question is an example.

The nature of the question does not demand creativity, but inherently encourages the student to consider the veracity of each provided answer before selecting the single correct one. Typically, he or she must apply a limited range of skills and knowledge to reach this answer quickly.

This mirrors many out-of-school scenarios, wherein someone must use all the information available to him or her to make a decision.

Divergent thinking, on the other hand, starts with a prompt that encourages students to think critically, diverging towards distinct answers.

As you can see, the prompts -- in the form of guiding questions -- are open-ended and typically require thinking at the third, or even fourth, Depth of Knowledge level.

Writing an essay and brainstorming are examples of exercises that demand divergent thinking.

Creativity plays an important role , as students should usually reach an answer they did not anticipate upon processing the prompt. This is because the prompt should encourage them to analyze content and generate their own ideas to arrive at a range of plausible solutions.

This mirrors real-life situations in which students face a broad problem without much information.

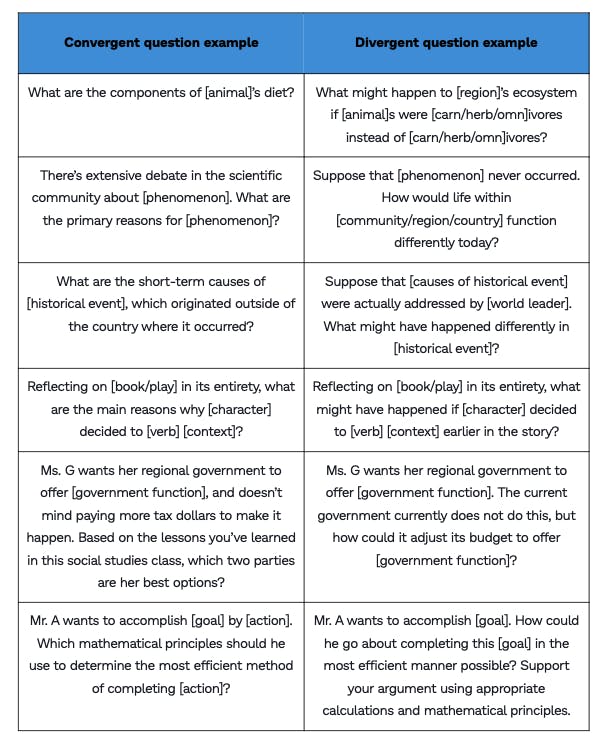

Now that you understand convergent and divergent thinking, you’re probably curious about the kinds of questions that incite each strategy.

Examples of convergent vs. divergent questions

Like most teaching tasks, writing convergent and divergent questions is easier said than done.

Use these examples as templates, and to guide your creation of content-appropriate convergent and divergent questions:

Although it’s likely these convergent and divergent question examples aren’t completely applicable to you, they should -- at the very least -- give you a clear idea about how to structure your own questions.

How to write original convergent and divergent questions

Using the above examples as inspiration, keep these tips in mind to create your own convergent and divergent questions:

- Focus on the beginning -- Before you get into the nitty gritty of crafting a question, you should understand that the first few words are the most important. That’s because they’ll largely deem what kind of responses you’ll receive. Convergent questions typically start with “who,” “what,” “where” or “when.” Divergent questions usually begin with “how could,” “what might” or “suppose.”

- Search far and wide for the answers -- Validating a question starts by finding answers. You shouldn’t have a tough time answering convergent questions. Flipping through a textbook, lesson notes or an online resource should yield a clear answer. On the other hand, you shouldn’t find a definitive answer to a divergent question through such research methods. You’re encouraging students to deliver original responses born from critical thinking , after all.

- Make convergent questions before divergent ones -- If you struggle to brainstorm divergent questions, start with convergent questions. Often, the process of writing three to four convergent questions will allow you to combine them into a divergent one. Consider the notion that divergent queries begin with phrases such as “suppose.” Answering a “suppose” question comes from understanding “what,” “who” and the answers to other convergent questions.

With examples in your toolbox -- and tips about how to create your own questions -- you need to consider the appropriate times to ask them.

When, and how, to give opportunities for convergent and divergent thinking

During lessons, before study times and at the conclusions of entire units, opportunities to spur and assess convergent and divergent thinking will present themselves.

Here are four opportunities to encourage convergent thinking, and how to do so:

1. You’re in the middle of a math lesson, and arrive at a word problem . Don’t immediately start the problem-solving process. Instead, walk through the wording with students before giving them five minutes of independent work. Using their notes and textbooks for reference, they can determine the functions needed to solve the problem.

2. The content you’re delivering in history, social studies or language arts class is broad enough that you anticipate students will struggle to process it. As a quick differentiated instruction exercise , provide a physical timeline and list of events to small groups of students. Ask them to pin the events to the timeline, aiding contextualization.

3. You’re giving a lecture-style lesson, and want to avoid providing a solution without giving students a chance to answer the question. But they’re struggling to respond. To enable convergent thinking, present potential answers in a multiple-choice style fashion. “Who wrote [text]? Was it [author], [author] or [author]?”

4. It’s the end of a unit. To review content in preparation for an assessment, ask students to summarize aspects of the unit. For example, “List x ways to apply y skill.” Or, “In what ways did [person] accomplish [goal].” If you provide a high number of such tasks, you can run a jigsaw activity , allowing students to work together to review key material.

Here are four opportunities to encourage divergent thinking, and how to do so:

1. You’re reading a play or novel as a class, and the protagonist faces a major problem. Before learning how he overcomes it, ask the class to think of as many solutions as possible. You can run this as a think-pair-share activity. Specifically, students can individually think of solutions, pair with one another to exchange ideas and then share these ideas with the class.

2. Running through new math problems as a class, you present a broad word problem that’s rooted in skills students already have. Instead of immediately solving the question, give them 15 minutes to find as many methods of solving it as possible. After, hold a class discussion to share responses.

3. Your class has made it to the end of a history or social studies unit. They have a fresh, firm grasp on the unit’s content, meaning it’s an ideal time to pose a query that demands divergent thinking. Ask them what they believe would have happened if a given figure had done y instead of x . Individually, or as a small group, students should write a short paper on potential outcomes and impacts.

4. Students are a week or two away from starting a written assessment. Why not prepare them with a formative assessment ? Simply give them a mock essay question that deals with similar subject matter, helping them study as they investigate different responses.

Although you can use them separately, convergent and divergent thinking aren’t mutually exclusive.

This is because divergent thinking can lead in to convergent thinking.

Consider asking a question such as, “Suppose Bilbo Baggins didn’t pick up the Ring when he first had the chance. How might his encounter with Gollum have been different? What are some potential outcomes?” Students who have a firm grasp of The Hobbit would likely generate many ideas from this divergent question.

This opens the door to asking a convergent question as a follow-up. For example, “Based on the different outcomes you envisioned, which one is the most probable? Why?”

Linking the two thinking styles in this manner can prepare students to write essays and tackle open-ended projects , as well as out-of-school dilemmas in which they must choose the single-best course of action.

Final thoughts

Developing strong commands of convergent and divergent thinking should empower students to tackle challenging problems, in and out of the classroom.

What’s more, being able to use the thinking styles -- independently and together -- is critical in many projects, group activities and forms of assessment.

This is why it’s crucial to provide opportunities to apply convergent and divergent thinking, while offering scaffolding and supplementary instruction.

Reading and referencing this guide is only a first step, albeit an important one.

Create or log in to your free teacher account on Prodigy — a fun, easy-to-use math platform that delivers content in an engaging game-based learning environment. Aligned with curricula across the English-speaking world, it’s used by more than 2.5 million teachers and 100 million students .

K-12 Resources By Teachers, For Teachers Provided by the K-12 Teachers Alliance

- Teaching Strategies

- Classroom Activities

- Classroom Management

- Technology in the Classroom

- Professional Development

- Lesson Plans

- Writing Prompts

- Graduate Programs

How to Teach Divergent Thinking

Kelly nelson-danley.

- July 8, 2020

What is Divergent Thinking?

When you hear the term divergent thinking, you might have a flashback to the book (also a popular movie) Divergent, in which some of the unique characters in this story are “divergent” or different. Divergent simply means being able to think outside the box as opposed to convergent thinking, which means to restrict ideas to ones that might be the only correct answer. Divergent thinking opens students up to the idea that there can be more than one way to solve a problem. As education evolves, instruction tends to promote more divergent thinking than it has in the past.

Benefits of Divergent Thinking

Divergent thinking has many benefits. Once upon a time, convergent thinking was encouraged. There was one solution and one way to arrive at that solution. Now, creative thinking is encouraged in the classroom and in the real world. Students need to be prepared to be flexible and think outside of the box. Divergent thinking allows students to make connections between ideas and to find innovative ways to view problems. When students can think divergently, they are able to find solutions to problems in unexpected ways.

Additionally, divergent thinking allows students to work together to generate new ideas. This encourages collaboration and prepares students for working with others when they enter into a college and/or career setting. When students practice collaboration, they are practicing the idea of pushing the boundaries of their schema and imagination.

Not only does divergent thinking inspire students to think outside the box and to collaborate, it also gives students a sense of excitement and interest regarding subject matter. If students are allowed to approach curriculum with the mindset that they are encouraged to solve a problem in a way that works for them, they are more likely to be motivated to put their best effort into action.

Teaching Strategies to Promote Divergent Thinking

Educators can incorporate divergent thinking in a variety of ways. The following strategies are ways to incorporate divergent thinking into daily classroom activities.

- Encourage Students to Embrace Creativity – By allowing students to have time to free write, use various materials to create products, and invent new games, educators are encouraging students to think differently. Some educators may even limit the amount of resources or time allotted during these creative activities in order to push students to think divergently.

- Ask Divergent Questions – Teachers are often guiding student learning by asking appropriate questions. Divergent questions involve real world situations that ask students to solve a problem that has multiple solutions. com provides a list of examples of divergent thinking questions as compared to convergent thinking questions.

- Brainstorming – Brainstorming is a strategy that has long been present in instruction. It involves generating a list of ideas, as many as possible in a short period of time. Brainstorming allows students to record all ideas and disregard none. This leaves the field of options open and encourages students to explore a variety of ways to approach problems.

- Foster a Creative Environment – As educators, it’s important to set the tone of the classroom. This can be done by encouraging students to think critically and creatively and by modelling divergent thinking. Allow students to share their ideas with each other so that they can gain a better understanding of others’ perspectives and thought processes.

- Use Inquiry-based Learning – Using inquiry-based learning asks students to formulate questions, research answers, share knowledge, and reflect on their learning process. In inquiry-based learning, students are given autonomy to decide on questions about the topic they want to explore. This allows students to use open-ended questions to direct their own learning and make connections to deepen their understanding of subject matter.

- Give Students Access to Unconventional Learning Materials – Every teacher needs solid lesson plans as a staple in their teacher tool kit; however, introducing additional unconventional learning materials will help students think creatively and engage deeply in lessons. These materials might include, but are not limited to: using QR codes, collaborating using Google Slideshows and Google Classroom , allowing students to listen to educational podcasts, inviting guest speakers into the classroom, and involving community members in lessons.

While creativity isn’t something that can be taught step-by-step, it is a way of thinking that can be applied to classroom tasks on a daily basis. This way of thinking can then be carried over into students’ lives and futures. Engaging students in divergent thinking is stimulating, exciting, and a surefire way to allow students to engage with subject matter in a fun and creative way.

- #DivergentThinking , #TeachingStrategies

More in Teaching Strategies

Unleashing the Learning Potential of Classroom Focus Walls

Focus walls have emerged as an effective tool in today’s classrooms, and for…

Getting Older Students Excited About Science Class

As students move into middle and high school, it becomes increasingly challenging for…

AI-Powered Lesson Planning: Revolutionizing the Way Teachers Create Content

Traditional teaching methods are evolving since technology has been integrated into classrooms across…

How to Promote Civic Engagement through English and Math

Civic engagement provides excellent opportunities for students to serve others and their communities…

Toolkit Library/

How to teach divergent thinking.

Creativity requires us to diverge from prior thought patterns and to consider fresh perspectives and possibilities—a process that can happen through both individual and group explorations. This two-page guide from the University of Texas at Austin provides an overview of divergent thinking and suggestions on how to foster divergent thinking in the classroom.

20 minutes

by: ut austin faculty innovation center, educator-prep | k-12 educators, making connections:.

Principled Innovation asks us to work with others and recognize the limits of our own knowledge so that we can better understand and tackle the complex issues our communities face.

Quatrenary Headline

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud

K-5 card deck activity: altruism.

15 minutes

By: Principled Innovation ® (PI)

Why diversity is hard (and why it’s worth it)

2 minutes

By: Columbia Business School, Katherine Phillips

Empathy in designing solutions

To understand your students, use “compassionate curiosity.”.

By: Education Week, Kyle Redford

Creative resilience

1 minutes

By: ASU, Liz Lerman

Access our collection of +200 learning materials

Fostering Divergent Thinking for Student Creativity

In partnership with Model Teaching, an industry leader in supporting educators, this quick course highlights the importance of divergent thinking and how it relates to creativity. Model Teaching’s Mission is to improve student performance by directly supporting teachers with quality content and resources. You will learn how to support creativity through divergent thinking using the strategies, activities, and resources provided within this course.

Details + Objectives

Course code: t14718.

This quick teacher professional development course teaches you about divergent thinking, also known as divergent reasoning, and its role in creativity. You will explore what divergent thinking is and then learn specific activities that can help you foster and support creativity in the classroom. You will also be provided guidance on how to give feedback and support to your students to improve creativity over time.

The course comes with a downloadable PDF of the content and multiple graphic organizers and resources ready to support your students in building their creative thinking.

What you will learn

- Understand and define divergent thinking and its role in creativity

- Analyze strategies and activities to support divergent thinking in the classroom

- Evaluate a method of feedback to help support and improve creativity and divergent thinking in your students

How you will benefit

- You will think about your lessons differently and consider methods to help support and foster creativity within your classroom regularly

- Your students will become more thoughtful and creative over time if you implement these strategies regularly

- Student progress will improve significantly in creative subjects like experiment design in science or essay writing in English Language Arts (ELA) classes with regular divergent thinking practice

How the course is taught

- Self-Guided, online course

- 3 Months access

- 1 course hours

- The video and article will provide you with an understanding of divergent thinking and how to foster creativity within your classroom using specific strategies and techniques. The course also includes some “Reflect or Discuss” prompts to help you connect with the course content and ends with a “Try This Task” to guide you explicitly on how you might implement the ideas into the classroom.

- You will answer questions related to creativity and divergent thinking. Quizzes are automatically scored and provide feedback on answer choice rationale.

- The reflection prompt requires you to plan for use of the “try this task” by either reflecting on the content yourself or discussing them with the colleague. You will then discuss a new concept you can attempt to implement in the future based on something you learned in the course.

- This short statement helps you reflect on your ideas and assess whether you might be successful in your implementation.

- Additional content suggestions are provided to enhance and expand your understanding of divergent thinking.

Instructors & Support

Requirements.

Prerequisites:

There are no prerequisites to take this course.

Requirements:

Hardware Requirements:

- This course can be taken on either a PC, Mac, or Chromebook.

Software Requirements:

- PC: Windows 10 or later.

- Mac: macOS 10.6 or later.

- Browser: The latest version of Google Chrome or Mozilla Firefox is preferred. Microsoft Edge and Safari are also compatible.

- Microsoft Word Online

- Editing of a Microsoft Word document is required in this course. You may use a free version of Microsoft Word Online, or Google Docs if you do not have Microsoft Office installed on your computer. Model Teaching can provide support for this.

- Adobe Acrobat Reader

- Software must be installed and fully operational before the course begins.

- Other: Email capabilities and access to a personal email account.

Instructional Material Requirements:

The instructional materials required for this course are included in enrollment and will be available online.

When can I get started?

Your course begins immediately after you enroll.

How does it work?

You have 3 months of access to the course. After enrolling, you can learn and complete the course at your own pace, within the allotted access period. You will have the opportunity to interact with other students in the online discussion area.

How long do I have to complete each lesson?

There is no time limit to complete each lesson, other than completing all lessons within the allotted access period. Discussion areas for each lesson are open for the entire duration of the course.

What if I need an extension?

Because this course is self-guided, no extensions will be granted after the start of your enrollment.

Related Courses

Integration and Implementation Insights

A community blog and repository of resources for improving research impact on complex real-world problems

Enabling divergent and convergent thinking in cross-disciplinary graduate students

By Gemma Jiang

How can we enable graduate students to think in ways that open new possibilities, as well as to make good decisions based on diverse cross-disciplinary insights?

Here I describe how we have embedded 14 graduate students in a research team with nine faculty from four academic institutes, representing six disciplines (for simplicity only three disciplines – engineering, economics, and anthropology – are considered here). Our research addresses the circular economy. I have developed a three-step model (summarised in the figure below) to operationalize the “divergence-convergence diamond,” which is key to our teaching method.

The “divergence – convergence diamond” is widely used in design thinking. The divergent mode helps open new possibilities while the convergent mode helps evaluate what you have and make decisions. Both are important to cross-disciplinary collaboration. Divergence without convergence results in disjointed ideas without any impactful output, while convergence without divergence leads to “same old same old” ideas without a breakthrough.

The three steps in our teaching model are:

- Student meetings

- Three-minute pitch

- Convergence circles.

Step 1. Divergence: Student Meetings

We have designed our bi-weekly student meetings to focus explicitly on fostering cross-disciplinary dialogues. Each meeting is facilitated to minimise structure and maximise creative ‘chaos’. We have two major types of meetings:

- exploring the frontiers of research

- topic ‘provocations.’

In meetings exploring the frontiers of research, each student is invited to pitch a research topic they would like to explore. The student team votes for one idea to focus on during the meeting, which is then examined through different disciplinary lenses. For example, in a recent meeting where the chosen topic was the social aspects of the circular economy, students from different disciplines shared their perspectives:

- the anthropologist discussed professional identity and how the attachment to a fixed identity could trigger resistance to change;

- engineers were primarily concerned about the technologies involved, and also brought up the importance of involving communities in developing and deploying technology from their past experiences;

- the economist wondered how economic modelling could bring all the parts together.

In topic ‘provocation’ meetings, we invite students from one discipline as topic owners to start the meeting with a provocation on a topic and then foster cross-disciplinary interaction. For example, the economics student invited everybody to explore how the different disciplines could get involved in designing an experiment to test the feasibility of a “durability label” for products in the United States.

After the meetings, students have opportunities to continue to explore the ideas through collaborative writing and self-organized small groups.

When asked about their experience with these dialogue-driven meetings, one student said “These conversations are only possible because we have such a diverse team. We need to face circular economy as the complex system that it is. We can’t run away from the uncomfortable talks about our different worldviews.”

These activities enable students to “stretch” their divergent thinking through meeting themes, facilitation methods, writing initiatives and self-organized groups. Together they build a runway for deep thinking and cross-disciplinary exploration.

Step 2. Inflection: Three-Minute Pitch

Groups of students come together to pitch a research idea to the entire research team at the monthly whole team meeting. To qualify for a three-minute pitch, the idea has to be sponsored by at least three disciplines. This initiative facilitates not only the transition from divergence to convergence by clarifying potential research questions, but also the bottom-up dynamics by connecting students with faculty. In most cases, faculty advisors are invited to guide the development of pitch ideas and co-present the pitch with their students.

After the presentation, the pitching team receives coaching from the rest of the research team, followed by a participatory decision-making process to decide whether to move the pitch idea into a research project.

Step 3. Convergence: Convergence Circles

A convergence circle forms around pitch ideas that are chosen for research projects. Each convergence circle is a microcosm of the larger team with roles such as a process coach to help with the convergence process, academic advisors to provide subject matter expertise, and a circle captain to lead the team. In most cases, advanced graduate students are appointed to be circle captains, while faculty members experienced in cross-disciplinary collaboration volunteer to serve as process coaches.

We employ field-tested structures and processes to foster innovative thinking within such close-knit circles, such as liberating structures, design thinking, social labs, and agile methods. Outcomes of a convergence circle include scholarly outputs, such as peer-reviewed publications and conference proposals.

In my previous blog post, Three complexity principles for convergence research , I laid out three types of transformative containers. This post provides a practical model to operationalize one of them: the container for small, intensive transdisciplinary research teams and is especially useful in graduate student education.

Another application of the divergence-convergence diamond can be found in Carrie Kappel’s blog post Collaboration: From groan zone to growth zone .

For faculty readers: what has your experience been with teaching graduate students about divergence and convergence? What tools, methods or models have you found useful?

For student readers: what worked in enabling you to conduct cross-disciplinary research both divergently and convergently? Are there particular tools, methods or models that you would recommend?

Acknowledgement :

Funding for this research was provided by the U. S. National Science Foundation Award, ID: 1934824, GCR: Collaborative Research: Convergence Around the Circular Economy.

Biography: Gemma Jiang PhD is the founding director of the Organizational Innovation Lab in the Swanson School of Engineering and the founding host of the Pitt u.lab hub at the University of Pittsburgh in the USA. She applies complexity leadership theory, social network analysis, and a suite of facilitation methods to enable transdisciplinary teams to converge upon solutions for challenges of societal importance .

Share this:

24 thoughts on “enabling divergent and convergent thinking in cross-disciplinary graduate students”.

Thank you Gemma and others for these posts and for contributing to this conversation. These teaching methods, as described, contribute to the field of education in BIG ways and can be applied in primary and secondary school as well as graduate studies. Thank you again for sharing. As Paul mentioned, I too am interested in hearing how these various projects develop over the next 6-12 months (PhD student at the University of Alberta, Canada, studying career integrated learning and interdisciplinary competencies in school communities).

Thank you for your interest, Colleen. Good luck applying the methods in your context. I would love to hear your stories as well.

While my instinct reaction to the notion of diamond cycles was decisively positive, the Double Diamond (British Design Council) workflow representation includes a couple of essentials missing here. With one proviso of course, the ideals framing my observations are those of a design process, as opposed to brainstorming style workshops, I doubt that introducing a ‘pitch’ formalism makes up for that difference.

First, progression through two distinct sets of divergent and convergent phases; provides a more explicit guide of actual activities. And second, accounting for the transition between two distinct stages of work (rendered as diamonds) seems to be more constructive that the proposed inflection point of pitching proposals.

At the point of transition, the all important ‘problem definition’, captured in the first diamond, moves into the development domain, generally implying new roles and corresponding abstractions entering the collaborative space. Absence of explicit emphases on this translation or mapping from ‘doing the right thing’ (problem definition) to ‘doing things right’ could prove to be a serious drawback.

For more on the Double Diamond see: https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/news-opinion/double-diamond-15-years

thank you Piotr for the critique, and Gabriele for the link. I never heard of the double diamond, as you can see I am not a designer. I appreciate this framework — I can already see rooms for improvement of the model I described. The exploration continues…

Hi Gemma, thanks very much for sharing this model and your experience of using it. It is a very practical approach to how to get interdisciplinary groups of students to work on problems. I was just wondering whether, after convergence, the students took their ideas for research projects and further developed them into funded projects, papers, conferences, etc? Best wishes, Paul

Thank you, Paul. Great question. Our expected outcomes are exactly what you described–funded projects, papers, conferences. We are moving nicely along the trajectory, and it takes time, as we all know!

Thanks Gemma for your reply. Great to hear that the outcomes have a lifetime after the process – this should really cement and deepen the interdisciplinary collaborations. I would be interested in hearing how these various projects develop over the next 6-12 months.

Yes, absolutely. I would love to follow up on this. One quick follow up I can already give is that we are listing one of our pitch ideas, ‘material passport’, as one of our ’emergent projects’ that were not described in our original proposal, as we seek further funding for this project.

Hi Gemma, great to hear that one of the ideas will go on to see further funding. Thanks.

Dear Gemma,

Great to see a colleague at Pitt also working on this topic! I wondered how you attend to issues of power, particularly when race/ethnicity and gender are correlated with status at Pitt.

Hi, Chris, what a delightful surprise to connect with a fellow Pitt friend! Apparently we are doing similar things but plugged into very different networks. We should connect.

I love your question about race and gender. Could you clarify if this question is for this NSF project specifically, or for Pitt in general? Only about half the researchers and students on this project are from Pitt, and we have three collaborating universities. So the dynamics are different…

Let’s just pick gender for now, but a similar story could be told for race/ethnicity. In every discipline, the higher up the food chain you go, the more male dominated it becomes (true everywhere and at Pitt in engineering). So, when students are female and faculty are male, how do you disrupt the double power dynamic? Is it worse in heavily male-dominated departments (ECE, MechE vs. ChemE and IE).

And then there is the intersection of gender and ethnicity/race/culture, mansplaining, in my experience is pretty common in engineering students (at least at the undergrad level, according to recent studies at Pitt). When students are coming from more male-dominant cultures (common in engineering grad students), does this amplify the challenge in getting full and equitable participation in convergence and divergence phases?

I’m also curious about power by ‘dominant’ discipline for a project. In my experience, each project has a primary discipline (e.g., it is more BioE than MechE or more ECE than IE). Does the likelihood of gender differences that are confounded by discipline disciplines complicate either divergence or convergence phases?

Too many questions here, so I’d be more than happy with an answer to any of them!

Very thoughtful questions here, Chris. In terms of gender, we have 4 female co-pi and 4 male co-pi; 9 female students, and 5 male students. The gender dynamics is overall balanced, in my view. In terms of disciplines, we have 3 social science co-pi and 5 engineering co-pi; 3 social science students and 11 engineering students. Apparently the engineers are in the majority, but given the emphasis of our grant on convergence, our social scientists are quite respected and sought after. of course, not all the power dynamics is as healthy, but I do not feel comfortable to discuss it here in protection of identity.

Ok, sounds like you have built a uniquely healthy microcosm that will be challenging to scale! I also had positive experiences with collaborating engineers in the School of Engineering. When my collaborators left and I had to quickly take substitutes, the experience was less positive. 😉

That is the point, Chris, complexity is highly contextual. There are general principles we could abide by, but how it works out with each team configuration is so context specific–no principles can encompass all the human complexities.

I am worried about statements like “no principles can encompass all the human complexities”. It seems to deny the engineering or science of teamwork. I think it is on us to theorize, design for, and test approaches which are robust across more and less desirable starting conditions.

Hi Gemma, very nice application of the divergence-convergence diamond to cross-disciplinary research and graduate training as described in your article! I like how you’ve operationalized the diamond through the student brainstorming meetings, three-minute pitches, and convergence circles. On the divergence side of the diamond, a strategy that we’ve used to foster the development of creative ideas among members of cross-disciplinary teams is the “idea tree” exercise as described in this earlier i2i blog article: https://i2insights.org/2019/03/12/idea-tree-brainstorming-tool/ . Please let us know if you have occasion to try it out with your faculty-student research teams. I look forward to learning more about your research. All best, Dan

Hi, Dan, thank you for the comment, and for sharing your idea tree exercise. I just read your post, and really appreciated the ease of applying this method. It reminded me of the Round Robin method I learned in design thinking. Here is a post to learn more: https://www.mindtools.com/pages/article/round-robin-brainstorming.htm

I am curious how you adapted the idea tree exercise for virtual environment. Did you use Mural as a platform?

I use a method called 1-2-4-all, one of the liberating structures, to facilitate our divergence process.

Dear Dr. Gemma Jiang.

Thanks for your interesting insights. I, as a PhD student, agree with your concept and think that especially ‘provocation” meetings or other comparable spaces are needed to trigger cross-disciplinary approaches. During my studies as a Masters student and now as a PhD student at ETH (in Zurich Switzerland), I realized that especially the method “drawing a rich picture” helped me and my colleagues to first get the overall picture. All experts from the different fields were thereby able to put their puzzle part on the picture. Afterwards, we were able to jointly define a research question.

However, I would have one question for you. Is this concept only applicable to cross-disciplinary research or also transdisciplinary research? Have you made any experiences with that?

Thanks again and best wishes, Irina

Hi, Irina, I appreciate your comments. I also really enjoyed reading your post on your experience with transdisciplinary research in the winter school ( https://i2insights.org/2020/10/06/students-on-transdisciplinary-learning/ )

Yes, I use the word cross-disciplinary to refer to a wide range of research: inter-, multi-, disciplinary, and convergence research in a more US context. The common thread is bringing coherence to an otherwise fragmented system by bringing people together who are otherwise isolated. I believe this model is definitely applicable, esp. the divergence phase. We need to make room for our differences before hurrying to convergence, otherwise those unrecognized differences will becoming tension and resistance.

I meant “inter-, multi-, and trans-disciplinary”:)

thanks a lot for this well-presented post. I wish I had had the possibility to follow a similar “onboarding” to cross-disciplinary research during my studies. It is great to see how you make an effort to integrate students into your groups’ work.

The question that it sparked in me goes into a similar direction as Irina’s above, so I like to follow up here. I also feel that the setup you described in the post would work very well for multi- and interdisciplinary projects. Including non-academic actors would most likely make things way more complex, both logistically, but also process-wise, since you then need to invest even more time in finding a common language, boundary objects etc.

Learning the relevant competences to lead such processes is crucial for students who like to work in transdisciplinary settings. At the same time, I would assume that most higher education institutions don’t yet provide spaces to develop these competences. So it might be worthwhile to explore whether the process outlined above could be adapted to transdisciplinary projects, and which changes would need to be made.

(This is more a comment than a question.)

Thanks, Jan

It would be very useful exploration, Jan. As you so wisely pointed out, adding non-academic actors would add additional layer of complexity, and all complexity is contextual, so further exploration case by case is definitely needed.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Discover more from Integration and Implementation Insights

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

Divergent Thinking: What It Is, How It Works

“Bring Your Weird,” is one of the values at Panzura , a cloud-management software company based in San Jose, California. “We believe that different thinking is what makes us awesome, and we encourage everyone to be their authentic self at all times,” said Ed Peters, chief innovation officer.

What Is Divergent Thinking?

This “different thinking,” also known as divergent thinking, has resulted in many effective decisions for Panzura, including moving the company’s entire product-development and quality-assurance efforts to its Mexican nearshore unit, rather than nearshoring only parts of the process.

More on Leadership Skills 11 Essential Leadership Qualities for the Future of Work

In the 1950s, psychologist J.P. Guildford came up with the concept of convergent and divergent thinking . Convergent thinking is organized and linear, following certain steps to reach a single solution to a problem. Divergent thinking is more free-flowing and spontaneous, and it produces lots of ideas. Guilford considered divergent thinking more creative because of its ability to yield many solutions to problems.

“Divergent thinking is the ability to generate alternatives,” said Spencer Harrison, associate professor of organizational behavior at management school Insead. Divergent thinkers question the status quo. They reject “we’ve always done it this way” as a reason, he said.

Divergent thinking can and should involve convergent thinking, said Peters of Panzura. The two ways of thinking “are a yin and yang that can become a virtuous cycle and a source of great pride for the team members that create ideas, products and moments.”

Characteristics of Divergent Thinking

“All true thinking is divergent,” said Chris Nicholson, team lead at San Francisco-based Clipboard Health, which matches nurses with open shifts at healthcare facilities. “Everything else is imitation and doesn’t require thinking at all.”

Divergent thinking encompasses creativity, collaboration, open mindedness, attention to detail and other qualities.

Divergent thinking is creative , but it’s not creative thinking, which requires a complicated set of skills, Harrison said. Designers need to be empathetic to create suitable, organic solutions. That empathetic aspect of thinking is, in a way, divergent thinking because it leads to ideas, but it is not the sum and substance of divergent thinking, Harrison said.

“Engaging in divergent thinking while problem solving tends to result in more creative solutions.”

Divergent thinking and creativity are intertwined, said Taylor Sullivan, senior staff industrial-organizational psychologist at Codility , an HR tech company based in San Francisco. “Engaging in divergent thinking while problem solving tends to result in more creative solutions,” she said. “This is important because leader creativity has been shown to promote positive change and inspire followers,” she said. Creative problem-solving also enhances team performance, particularly when it involves brainstorming, Sullivan added.

“One of the key life lessons my father taught me was the importance of being willing to change your mind,” Sullivan said. Open-mindedness — the willingness to to consider new or different perspectives and ideas — is a hallmark of divergent thinking and is critical for effective leadership , she said.

Collaborative

Idea creation at Donut involves cross-department collaboration , said Arielle Shipper, vice president of operations at the New York-based company, which makes office communication tools. “We always pull in people from across the organization, even if the problem we’re working on doesn’t touch their direct role,” Shipper said. Representatives from product and engineering especially bring a perspective that helps tie products and the solutions, she said.

This collaboration involves getting input from everyone, even those who are reluctant to share thoughts, she said. “It’s important to me that everyone knows that their ideas are crucial for our work, even if they contradict what a more senior person is saying,” Shipper said. To spark conversation, she asks “is there anything you disagree with?” rather than “what do you think?” Asking the more tightly focused question, which Shipper calls a “simple but mindful shift in language” promotes a culture of acceptance and ideation.

Rethink Language

Along similar lines, Chris Nicholson and his team at Clipboard Health think divergently by escaping what he calls language traps, “when you realize that what’s happening is being obscured by the way people talk about it,” Nicholson said.

To illustrate: Clipboard Health believes that new hires should “raise the median” on the team they’re joining. That belief, though, led to rejecting people for the wrong reasons, for example not having a Ph.D on a team filled with Ph.Ds.

To get out of that language trap, the company settled on a multi-dimensional median for teams, meaning that candidates could excel in coding ability, humility or other skills .

Detail Oriented

“The devil is in the details,” said Leslie Ryan, managing director in cybersecurity and technology controls at JPMorgan Chase . “I have always thought outside the career and it has helped my career advance,” said Ryan, who has six direct reports and a team of 40.

Earlier in her career, Ryan’s employer wanted to outsource functions that many people thought couldn’t be outsourced. Trade support was one such function. “It typically required a person to be in proximity to the trader and details of the trade,” Ryan explained. By dissecting a trading assistant’s job, she was able to pinpoint certain functions, such as reconciliations and reporting, that could be outsourced.

“I tend to see the bigger picture — strategically and long term,” said Chris Noble, CEO of New York-based cloud-tech company Cirrus Nexus, who considers himself a divergent thinker. “I look at things from a perspective of not what we can’t do, but imagining what can be and where we need to go,” he said. The quality, which Noble attributes in part to his dyslexia, helps him visualize unique and forward-thinking products for Cirrus Nexus.

More on Productivity Productive Downtime Is a Startup Leader’s Secret Weapon

Build Divergent Thinking Skills

Chris Nicholson of Clipboard Health honed his ability to think divergently when he was young; his family of six debated at the dinner table and his father enjoyed playing devil’s advocate. “That led us to see different perspectives,” he said. Nicholson thinks many people are able to think divergently, but perhaps are not in environments that foster it. Divergent thinking is “creative, reality focused, and persistent,” he said.

Ask Questions

When faced with a problem, Nicholson asks questions: “Why do we think this is a problem? What do we achieve if we solve it? What data, experience and customer interactions do we have that backs up our hypotheses?” This “discovery stage,” he said, helps management understand a problem before it builds solutions. “Explore the mystery first and relish the discomfort of not knowing, rather than building a plan based on misguided beliefs,” he said.

Let Thoughts Flow Freely

Free-flowing thought is a necessary step in divergent thinking, agreed Christine Andrukonis, founder and senior partner at leadership consultancy Notion Consulting, who considers divergent thinking a hallmark of leadership. “A great leader’s superpower is to be able to see into the future and anticipate what’s next, which requires divergent thinking,” she said.

“A great leader’s superpower is to be able to see into the future and anticipate what’s next, which requires divergent thinking.”

When presented with a problem, Andrukonis lets her thoughts flow freely and writes them down. Then she steps away to think about what she’s written down and perhaps identify patterns among the thoughts. She circles those patterns, steps away again, and then connects them to the bigger picture.

“My step-away moments are literally that — going for a walk, spending time with my family, or doing something creative like painting,” Andrukonis said. Stepping away does not involve a meeting or work-related task, she said.

Listen Actively

“When I face a problem, I innately begin thinking of different ways the problem can be solved,” said Daryl Hammett, general manager, global demand generation and operations at AWS , based in Seattle, Washington.

Soon after, though, Hammett starts tapping his team for feedback. “We always start with working back from the customers’ needs, so I actively seek the advice and viewpoints of a diverse range of people, listening to their thoughts about the problems, goals, and challenges they face,” he said.

By actively listening , he practices divergent thinking skills and builds solutions with his teams. “Problems are not linear,” he said. “They’re multi-dimensional and should be addressed from a variety of angles before the best solutions appear.”

To nurture divergent thinking, Hammett encourages his team to challenge him without fear of judgment. “I am always open to feedback and change,” he said. “Having two-way conversations helps me cut through the noise and put my people first.”

He also considers divergent thinking a mark of effective leadership — it helped him navigate the management challenges of the pandemic and helps lead his team with flexibility.

Both divergent and convergent thinking have their place in a leader’s skillset, said Spencer Harrison of Insead. Leaders who deal with stable and settled situations might benefit more from convergent thinking, while leaders with unstable, volatile environments might do well to think only divergently.

“What research suggests is that divergent thinking might help you see new possibilities, but you would still need convergent thinking to realize and execute on those possibilities,” he said. “That said, because education and organizations tend to over-reward conformity, divergent thinking is probably a bit more rare and therefore likely more valuable especially in the long run over the course of a career,” Harrison said.

Peters at Panzura has his own opinion. “Sometimes the divergent thinking path wins, much of the time it doesn’t,” he said. “We create more opportunities for divergence by repeating the saying: ‘You never lose. You win or you learn.’

Great Companies Need Great People. That's Where We Come In.

Encyclopedia of Creativity, Invention, Innovation and Entrepreneurship pp 245–250 Cite as

Convergent Versus Divergent Thinking

- Kyung Hee Kim Ph.D. 2 &

- Robert A. Pierce Ph.D. 3

- Reference work entry

3200 Accesses

4 Citations

3 Altmetric

Definitions

Convergent and divergent thinking are two poles on a spectrum of cognitive approaches to problems and questions (Duck 1981 ). On the divergent end, thinking seeks multiple perspectives and multiple possible answers to questions and problems. On the other end of the spectrum, convergent thinking assumes that a question has one right answer and that a problem has a single solution (Kneller 1971 ). Divergent thinking generally resists the accepted ways of doing things and seeks alternatives. Convergent thinking, the bias of which is to assume that there is a correct way to do things, is inherently conservative; it begins by assuming that the way things have been done is the right way. Divergent thinkers are better at finding additional ideas, whereas convergent thinkers have a more difficult time finding additional ideas. Convergent thinkers run out of ideas before divergent thinkers. However, convergent thinking strengthens the ability to bring closure and to conclude problems.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Andersen L, Kim KH Are creatively gifted students different from academically gifted students. in press.

Google Scholar

Duck L. Teaching with charisma. Burke: Chatelaine Press; 1981.

Kim KH. The creativity crisis: the decrease in creative thinking scores on the torrance tests of creative thinking. Creat Res J. 2011;23(4):1–11.

Kim KH, Pierce RA. Torrance’s innovator meter and the decline of creativity in America. In: Shavinina LV, editor. The international handbook of innovation education. New York: Taylor & Francis/Routledge; 2012.

Kneller GF. Introduction to the philosophy of education. 2 ed., rev. New York: Wiley; 1971.

Kuhn T. The structures of scientific revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1962.

Schumpeter JA. Capitalism, socialism, and democracy. New York/London: Harper & Brothers; 1942.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

The College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA, 23185, USA

Dr. Kyung Hee Kim Ph.D.

Christopher Newport University, Newport News, VA, 23606, USA

Robert A. Pierce Ph.D.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kyung Hee Kim Ph.D. .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Information Systems & Technology, Management, School of Business, George Washington University, Washington, DC, USA

Elias G. Carayannis

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2013 Springer Science+Business Media LLC

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Kim, K.H., Pierce, R.A. (2013). Convergent Versus Divergent Thinking. In: Carayannis, E.G. (eds) Encyclopedia of Creativity, Invention, Innovation and Entrepreneurship. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3858-8_22

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3858-8_22

Publisher Name : Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN : 978-1-4614-3857-1

Online ISBN : 978-1-4614-3858-8

eBook Packages : Business and Economics

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Experiments

Divergent Thinking in Children

- Share article

How can I use grading policies to encourage a growth mindset?

Give students opportunities to be rewarded for demonstrating learning and improvement. Here’s something I wrote about the topic for Character Lab as a Tip of the Week :

Unlike most students in my introductory chemistry class in college, I wasn’t a freshman on the premedical track. I was a senior studying philosophy and psychology. Eager to expand my mind—I’d been developing a growth mindset over a few years—I took the course thinking it would be a good challenge.

And it was. Though the work was rigorous, the professor emphasized that anybody could master chemistry—that it wasn’t reserved only for the “naturally gifted.” I became even more excited about the idea of understanding the building blocks of the universe.

Unfortunately, the class was structured like many other science courses. Grades were based almost entirely on a few exams (with median scores regularly in the 60 percent to 70 percent range), and there were no opportunities to be rewarded for demonstrating learning and improvement. For example, students couldn’t revise and resubmit homework assignments for partial credit.

With dogged hard work, I managed to get an A-minus in the course. But the experience wasn’t what I had wanted. My focus quickly shifted away from learning and purely toward performance, with the end result that much of my initial enthusiasm waned.

In recent research , my colleagues and I found that having a growth mindset isn’t enough to overcome the messages sent by performance-centric settings. Teenagers read descriptions of different types of courses and reported how likely they would be to choose challenging coursework that would push the bounds of their learning. When classroom policies didn’t reward improvement, even the students who reported having a strong growth mindset were unlikely to take on the challenging coursework. And, like my experience in chemistry, this was still the case when the teacher clearly and consistently expressed that all students could improve and ultimately master the material.

Don’t believe talking passionately about learning is enough to inspire students. That message can fail if there aren’t tangible opportunities for kids to demonstrate and be rewarded for their improvement.

Do emphasize growth in both what you say and what you do. Let students retake exams for partial credit. Allow them to turn in early drafts of essays for feedback, then give them suggestions for how to revise. When you show through your actions that improvement is the highest-priority goal, it can spark young people’s enthusiasm to show off the fruits of their learning.

The opinions expressed in Ask a Psychologist: Helping Students Thrive Now are strictly those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinions or endorsement of Editorial Projects in Education, or any of its publications.

Sign Up for The Savvy Principal

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

COMMENTS

These five quick and simple tips will help you move towards divergent thinking in the classroom. 1. Journaling is a great way to encourage self-analysis and help students think through many solutions to a question. [13] Assign students to keep a journal and ask them thought-provoking questions.