Please could you help me fill in this feedback form so I can improve and make my website more useful

Mussolini's use of Propaganda

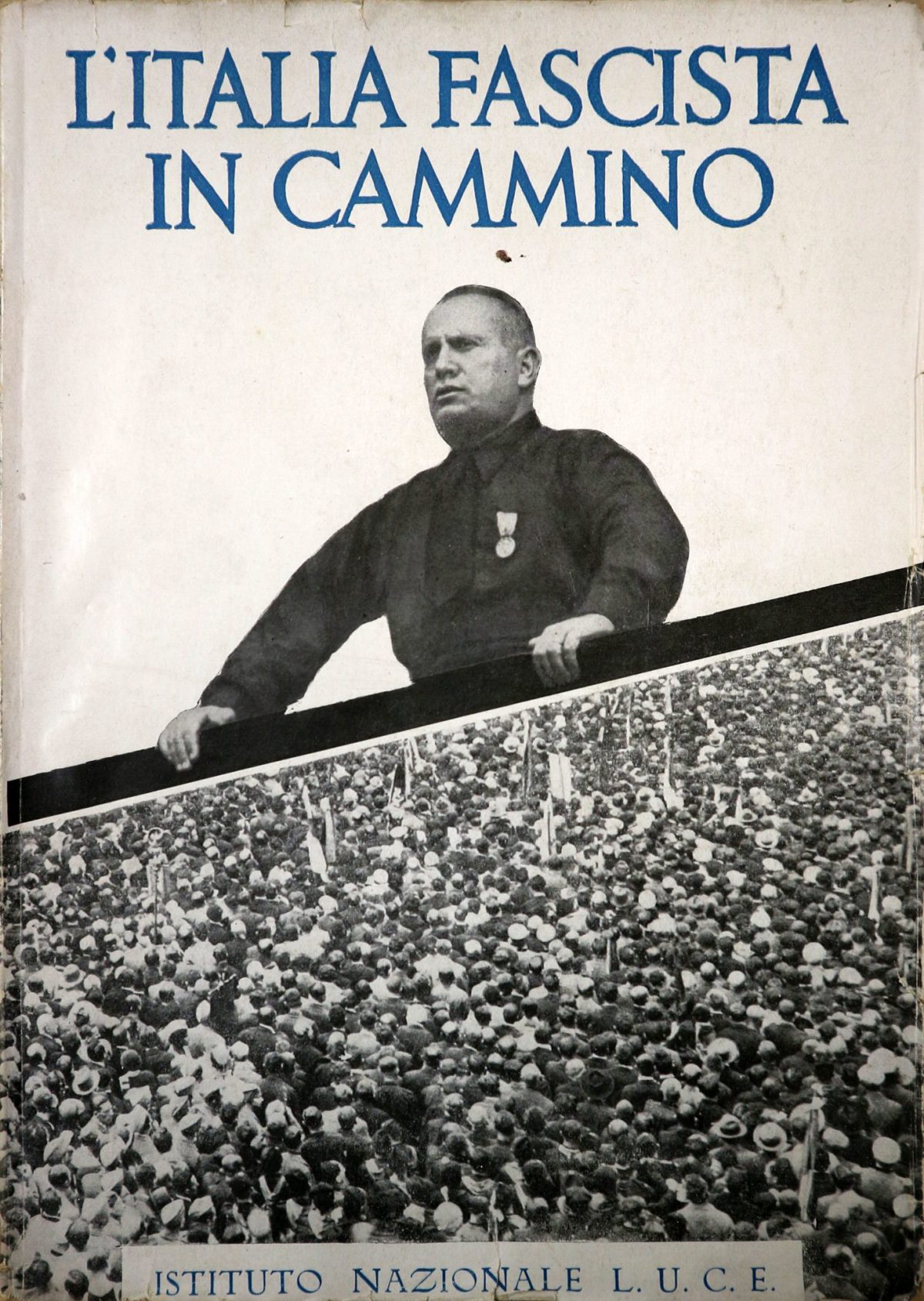

During the rule of the Fascists, Mussolini used propaganda to brainwash Italian citizens to ensure support and increase his popularity.

He used various types of propaganda to achieve this. Examples include...

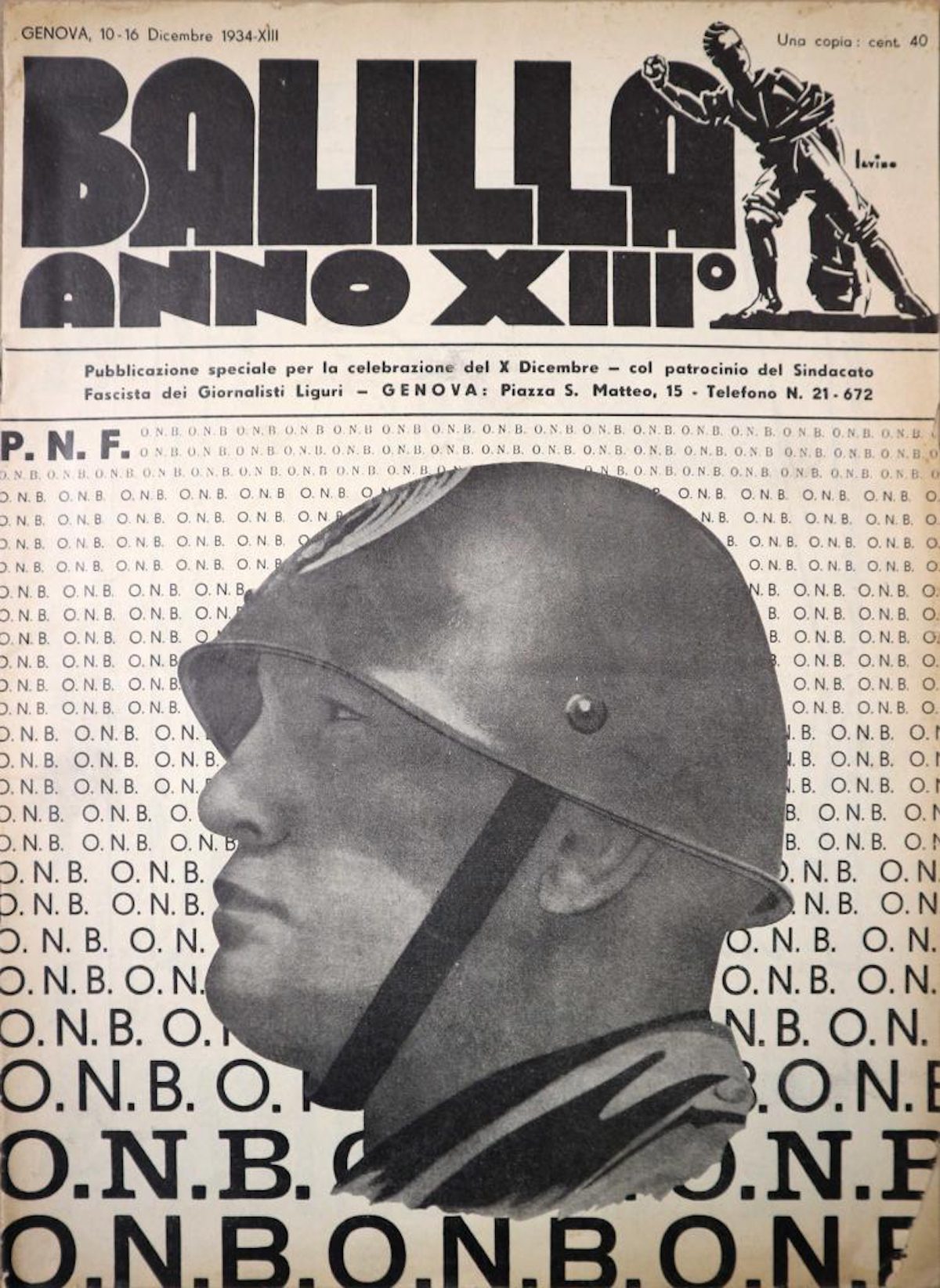

Mussolini had already banned all Anti-Fascist newspapers (including foreign newspapers) in July 1925 and required that all journalists should be approved by and registered with the Fascist party from December 1925. Therefore, when reading Italian newspapers, everyone would be influenced by propaganda as the news constantly promoted Fascism and portrayed Mussolini’s government in a very positive light.

Newspapers were used to promote the Fascist ideology, such as militarism, nationalism an d extremism. For example, when Italy joined World War Two on the side of Germany, in an article titled “People of Italy Run To Arms”, they stated that it was “Italy’s destiny to join the War”. As an ally of Nazi Germany, they also used their newspaper to spread Hitler’s news and Nazi German propaganda, such as anti-semitism.

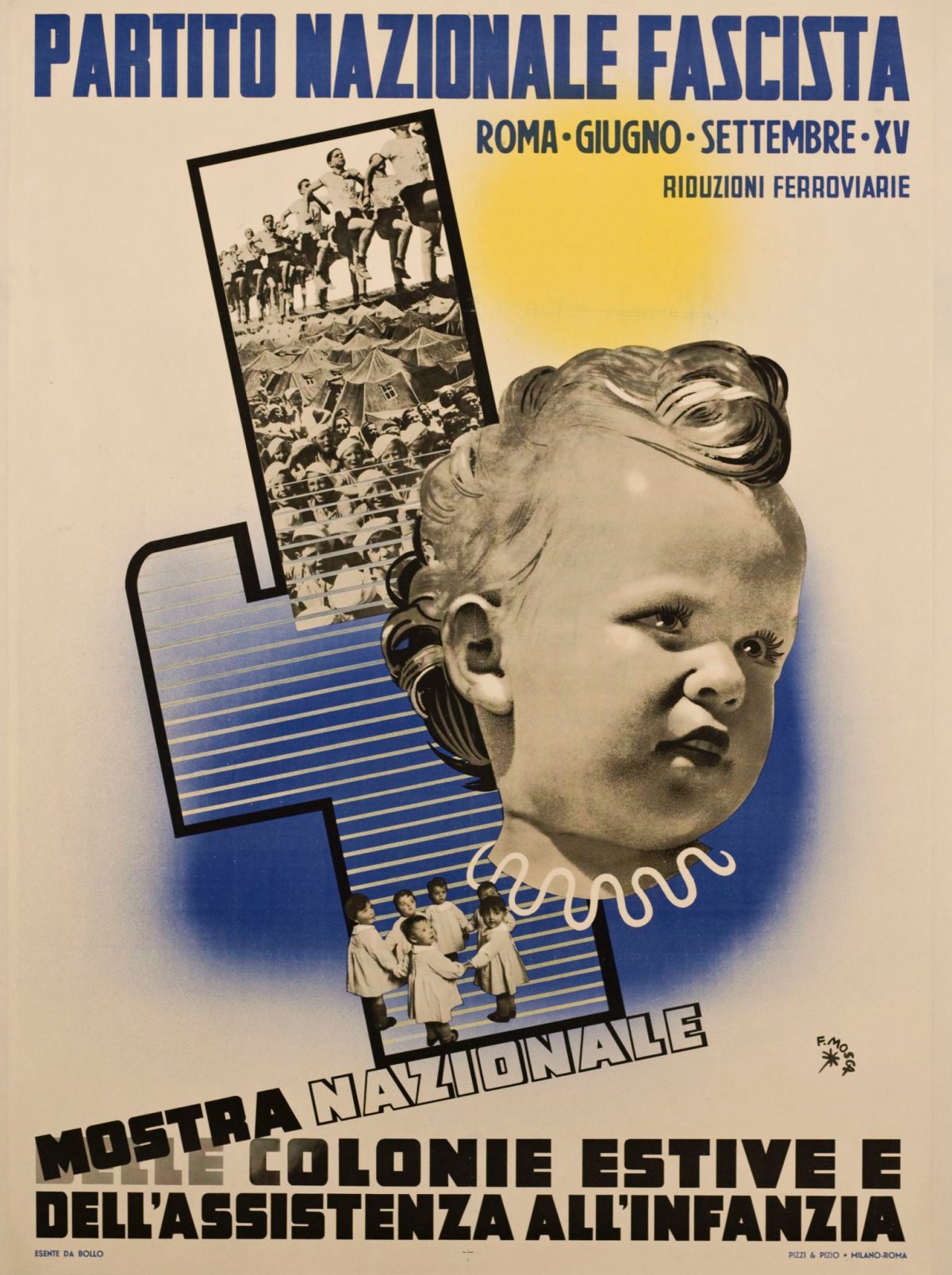

Fascist Italy used posters to show Mussolini’s brilliance, the power of Fascism, the threat of communism and a number of other messages.

On the right is a poster with a large face of Mussolini above smoking factories, the caption being “Greetings to the Duce, the founder of the empire”. Clearly, this had the purpose of celebrating the Italian leader, showing how he has established power and authority over the national image, by leading the country through greater development and expansion, and the power over the nation as a whole. The factories in the foreground and background indicate the industrial advances that Mussolini advocates and has brought for Fascist ideology and Italy as a whole. His large face evokes a sense of national pride as the stoic facial expression and the shadows drawn present him as a powerful Italian patriot who has seen war.

We found another poster of a young child (representing Italy), captioned ‘Papa Save Me’ with a red flag and symbol of communism in the background. This would appeal to the upper class, businessmen and bourgeoisie due to their fear of communism. In short, it tells Italians that they should be afraid of communism. The child fits the technique of pathos as it targets the audience emotions, telling them that they should save the child, and thus, Italy– from communism.

Mussolini changed the film industry and used the cinema to fit the interests of the state.

In 1934, a censorship government body was founded, with the power to read and change movie scripts, they awarded prizes to pro-Fascist movies and censored many foreign films. They provided full funding to movie scripts that had pro-Fascist messages in their original versions, whilst any approved movie scripts could also receive up to 60% of their funding from the state. With this, there was also a Directorate-General for Cinema who was responsible for monitoring it for anti-Fascist messages and for approving content.

In 1937, Benito Mussolini and his son Vittorio, founded Cinecitta movie studios with Luigi Freddi, Directorate-General for Cinema, in order to help filmmakers make films with pro-Fascist messages. The same year, an Italian movie, titled “Scipio Africanus: The Defeat of Hannibal” was released, promoting Italy’s Africa expansionist policy.

In 1924, Mussolini began to see the potential of the radio in dispensing propaganda. The Radio began to broadcast several state programmes. Although it mainly consisted of music, there were at least 2 hours of official broadcast each day, and this increased in the 1930s.

Additionally, Mussolini made speeches that were broadcast to crowds of people in Piazzas through loudspeakers. This is because, at the time, only 40,000 people owned a radio, although, by 1938, this had increased to 1 million and by 1939, 1 in 44 households owned a radio.

This large increase was likely due to the new rural radio agency which supplied schools with radios. There was also a Fascist leisure and recreational organization for adults called The National Afterwork Club (Opera Nazionale Dopolavoro, or OND for short). It ran community listening meetings that assisted in the spread of Fascist ideology, to people in rural areas and those who could not read.

Rallies and Sports

Italy was quite heavily invested in the sport of football, with Mussolini being an avid fan. In regards to sport, they had quite a few aims. The Fascist regime used football to improve the health and strength of Italian men, possibly as they wanted to be able to recruit a strong army in the event of War.

In 1934, Italy hosted the FIFA World Cup, using the opportunity to show off and sell Italian products. Rallies were also held, showing the might of the Italian Nation. Italy even won the World Cup that year, and it showed the strength of Italian men.

Many rallies were held over the years, aiming at impressing the audience, promoting discipline and encouraging national and collective identity. Examples of these rallies include the mass rally which was held in celebration of the seventh anniversary of the Fascist March on Rome. Again, in 1936, they organised a mass military parade in which medals were presented to war widows.

In terms of art, Mussolini banned degenerate art in an attempt to control the public and only allowed abstract art. As already discussed, posters were created as Fascist propaganda. Mussolini was also featured in art where he was depicted as a strong saviour and hero of Italy.

See again on the right... Mussolini's large face evokes a sense of national pride while the stoic facial expression and the shadows drawn present him as a powerful Italian patriot who has seen war.

With regards to sculptures, a huge sports complex, called Foro Italico, was created in Italy, with the primary aim of Italy hosting the olympics in 1940. Known originally as Foro Mussolini (meaning Mussolini’s Forum), statues of Italian athletes were built to advertise the success and strength of Italy— and it still exists today as a significant example of Fascist architecture.

Exhibitions

Furthermore, the Exhibition of the Fascist Revolution was held in Rome from 1923 to 1934 and featured art and sculptures.

It was opened by Mussolini on 28 October 1932 and had 4 million visitors.

The show told the story of the evolution of Italian history from 1914 until the March on Rome. It served as a work of Fascist propaganda which aimed at influencing and emotionally involving the audience, whilst it also compared Mussolini to the Roman Emperor Caesar, signifying that Mussolini would bring Italy back to it’s former glory.

Literature and Philosophy

In 1928, Mussolini also published his autobiography, recounting his youth, his time as a journalist, his experiences in World War I, the formation of the Fascist Party, the March on Rome, and his early years in power.

From 1929 and 1936, Enciclopedia Italia was published, also known as Treccani (after its developer Giovanni Treccani ). It was aimed at rivalling Britain’s Britannica Encyclopedia , although it had a strong focus on Italy’s role in world development as it aimed at displaying Italian pride.

The philosophy of fascism was conveyed through the Manifesto of Fascist Intellectuals . In this, over 200 intellectuals, led by the philosopher Gentile, produced this book on the philosophy of Fascism, similar to how Mein Kampf showed the philosophy of Nazism and the writings of Marx and Lenin the philosophy of communism. This aimed to show that without Fascism, there would be no true culture, and to prove that fascism was the one true ideology.

Culture and Music

The National Fascist Cultural Institute was established to spread Fascist culture to the masses, and by 1941, had over 200,000, mostly middle-class members.

Musicians were forced to join the Fascist Union of Musicians and were forced to reject foreign influences in order to develop “Cultural Authority”. Despite this, there was still some musical diversity in Italy.

LINK TO PODCAST: https://anchor.fm/from1student2another-hist/episodes/A-Level-Mussolinis-use-of-Propaganda-e18hku9

OUR SHOP IS OPEN - COME ON IN www.flashbackshop.com

Visit the shop

How Mussolini Won the Propaganda War: 1922-1943

The art of indoctrination - how political propagandists tried to on shape the 20th century into “a Fascist century”

“In 1931,” wrote British historian Arnold Toynbee, “men and women all over the world were seriously contemplating and frankly discussing the possibility that the Western system of Society might break down and cease to work.” As if to confirm that widespread anxiety, Mussolini proclaimed in the following year, “the liberal state is destined to perish. All the political experiments of our day are anti-liberal.” The following decade would reveal to the world the mass murderous designs behind that collapse.

Famed American journalist and writer Walter Lippmann agreed with Mussolini’s forecast , if not his motivations. When Hitler ascended to power in 1933, Lippmann told an audience at Berkeley, “The present century is the century of authority, a century of the Right, a Fascist century.” Lippmann ostensibly stood on the side of liberalism, though his was a decidedly top-down variety. Critical of democratic idealism, he argued in 1919, three years before the rise of Mussolini’s Fascism, that government and corporate elites must shape the views of the public, steering the ships of state and market by telling people what is in their best interest.

As influential as the work of writers like Lippmann and his disciple Edward Bernays was on the fields of advertising and public communications, it also appealed to political propagandists intent on shaping the 20th century into “a Fascist century.” Lippmann understood the dangers of the misuse of information, though he mostly saw that danger coming in the form of “Bolshevism.” As Hannah Arendt argued thirty years later in her diagnosis of totalitarianism, he wrote, “men who have lost their grip upon the relevant facts of their environment are the inevitable victims of agitation and propaganda. The quack, the charlatan, the jingo, and the terrorist, can flourish only where the audience is deprived of independent access to information.”

When Lippmann published those words, Mussolini was busy founding the Fasci de Combattimento . He lost the 1919 elections, but the man who would shape himself into the larger-than-life Il Duce did manage to enter the Italian parliament in 1921 and, with the complicity of liberal ministers, institute strict censorship and absolute control over the press. As Mussolini consolidated his dictatorship, “most of his time was spent on propaganda, whether at home or abroad,” one history explains , “and here his training as a journalist was invaluable. Press, radio, education, films—all were carefully supervised to manufacture the illusion that fascism was the doctrine of the 20th century that was replacing liberalism and democracy.”

To aid in the effort, Mussolini enlisted Futurist artists, many already fully on board with the fascist program, and communications experts already immersed in swaying what Lippmann broadly called “public opinion.” A current exhibit of Italian Fascist propaganda at New York University introduces the many examples on display by noting:

[F]ascist political propaganda coopted modernist aesthetics, mass communication, marketing techniques, and popular culture to manipulate society and muster support for its totalitarian endeavors. Considered together, the propaganda emerging from fascism, as well as from the particularly tense democratic times surrounding the fascist period, provide an opportunity to deconstruct the rhetoric of political communication in its entirety, and represent a call to engage critically with the multitude of competing political narratives that surround us today.

Communicating strength, health, authority, control, and the Neoclassical ideals in which Mussolini’s fascist state wrapped itself, the posters and publications from 1922 to 1943 show how fascism was normalized and made a part of everyday life. But Italian fascist propaganda is unique in that it embraced modernism, where Nazism rejected it wholesale and persecuted its “degenerate” artists.

Italian fascists realized, exhibition curator Niccola Lucchi tells Print , “that, as long as the propaganda message remained consistent, welcoming a variety of different modernist languages would project the idea that the regime welcomed creativity”—and, therefore, independent thought. “Fascist Italy co-opted every artistic current—an entire generation of artists gravitated in the orbit of the regime, which turned them into accomplices through misleading promises of artistic freedom.” The uneasy marriage of totalitarianism and creative liberty proved a particularly effective for Mussolini as a means of neutering subversive aesthetic movements by putting them on the payroll.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site . We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List . And you can also follow us on Facebook , Instagram and Twitter . For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop .

OUR SHOP IS OPEN - COME ON IN

www.flashbackshop.com

OUR SHOP IS OPEN – PRINTS, CARDS, TEES & MORE

15% off 3 or more T-Shirts

Recent Posts

Why James Bond Gave Up His ‘Lady’s Gun’ For A Walther PPK

Ernest Hemingway’s Six-Word Short Story

1980s Birmingham – Portraits of A City

A Painted Treatise on Cats From 19th Century Thailand

Maurice Sendak Illustrates William Blake’s Songs of Innocence

Editor’s picks, collect our postcards.

You Might Also Like

Italian Culture

How Mussolini Used the Legend of the Roman Empire to Create Fascist Italy

During Mussolini’s rise to power, he used propaganda to create a precise image and identity for fascism. Through speeches, posters, films, and much more, Mussolini used the tools of propaganda to gain the influence and support of the Italian people. As we were learning about the rise of fascism and fascist identity in Italy, I noticed that Mussolini often invoked images, phrases, and memories of the Roman empire in order to gain legitimacy and establish his identity as a powerful leader. Historians and scholars have used the terms “romanita” to describe people who attempt to emulate Roman values or ways of life in the modern age. Mussolini used “romanita” to establish the fascist party and I found this very interesting because it showed how political leadership can use a country’s collective memory and identity to its own advantage. Mussolini used Italy’s glorification and pride of the Roman Empire to his own favor in order to gain power and fascist control of the country. In this essay, I want to examine how Mussolini used language and imagery reminiscent of the Roman Empire in propaganda and popular communication to grow and cement his power as a leader.

Mussolini’s use of the Latin language is one of the main ways he incorporated Roman tradition into propaganda. One of the most widely known ways Mussolini incorporated Latin into fascist propaganda was through his nickname “Il Duce”. By calling himself Il Duce, which means “the leader” in Latin, Mussolini was deeply instilling the ties between fascism and the Roman Empire within the Italian people. Il Duce’s use of a Latin nickname was just one of the ways he tried to create a new chapter of Roman history. Mussolini was obsessed with Ceasar and the great accomplishments of the Roman Empire, and he saw himself and the fascist party as restoring the greatness of the Roman Empire. On May 9, 1936, Mussolini gave one of his most famous and well-known speeches after Italy has the second Italo-Ethiopian war. After winning the war the king of Italy was now also the king of Ethiopia, which Mussolini saw as the restoration of the new Roman Empire (Lamers, 2016). Mussolini gave an impassioned speech from his balcony in Rome, claiming “Italy finally has its empire. It is a fascist empire, an empire of peace, an empire of civilization and humanity”. To Mussolini and the fascist party, imperialist rule over Ethiopia was confirmation that fascism has successfully revived and brought back the greatness of the Roman Empire (Lamers, 2016). Imperialistic control of other countries meant that Mussolini was spreading Fascist ideas and influence across the world, much like Romans had spread their ideas and influence across their empire. Two weeks after his famous speech, Mussolini had Latin translations of quotes from the speech published in magazines and newspapers across the country. The Latin quotes had to be published alongside an Italian translation, but Mussolini felt that using the language of his Roman ancestors strengthened fascism’s connection to the great empire of antiquity (Lamers, 2016).

Mussolini used propaganda and Roman imagery to consistently to the Italian people that fascism would restore and revive the greatness of Rome. This can be seen clearly in the national symbol for fascism which incorporated the Roman icon of the fasces. During the time of the Roman Empire, the fasces was a bundle of reeds bound together with an ax carried by Roman officials as a symbol of authority. In the early 20th century, it became one of the most important icons of the new political climate. The symbol represented the concept of strength through unity and discipline. In 1926, the fasces was adopted as the official emblem of the Fascist Party (Doordan). In the images below, you can see how the Eagle of fascism is perched on the bundle of reeds, representing how fascism is building off of the traditions of the Roman Empire.

In addition to the emblem of the party, there were many other elements of the fascist party that were directly based on Roman tradition. Members of the party greeted each other with a Roman salute instead of a handshake (Visser, 1992). The traditional greeting is a gesture where the arm is fully extended and the palm is facing down. The gesture is most often associated with the Nazi party in Germany, but it began with the fascist party in Italy. The gesture was popularized as an alternative to the traditional handshake because it was seen as a show of strength and it was perceived as more hygienic (Visser, 1992). In the images below, you can see how the gesture was adopted from traditional Roman artwork.

After gaining power and instituting fascist rule, Mussolini began to use architecture as a form of propaganda and a way to communicate the power of the fascist party. Fascist architecture is easily recognizable and many of the structures are reminiscent of Roman architecture, with a few noticeable differences. Fascist architecture is known for emulating Roman design without the grandeur and extravagance, and instead making the designs more modern, simplistic, and symmetrical. The Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana exemplifies how fascist architecture co-opted the original designs of Roman architecture to reflect the beliefs of the fascist party. The building draws inspiration from the colosseum, with rows and columns of symmetrical roman arches on all sides of the building. The is a strong cube shape with sharp angles and intense symmetry, which makes it significantly different from the colosseum and traditional Roman architecture. The strong lines and imposing structure give the building an imposing presence and communicate a feeling of power to anyone looking at the building (Tucci, 2020). Fascist architecture was designed as a vehicle of propaganda to both emulate the greatness of the past and Roman accomplishment, while also communicating the strong and promising future of the fascist party. The buildings were designed to broadcast the imperial power of the fascist party and the greatness of Mussolini (Tucci, 2020). In the images below, it is clear how fascist architecture incorporated traditional Roman architectural images.

In addition to incorporating Roman techniques in a new form of fascist architecture, Mussolini also used iconic Roman structures to display his cult of personality and power. One of the best examples of this is the Mussolini obelisk and the Foro Italico. The Foro Italico is a sports complex in Rome built between 1928 and 1938 and was originally called “Foro Mussolini” or Mussolini’s forum. The complex was heavily inspired by traditional Roman forums and displays many of the same principles and ideas of fascist architecture that are present in The Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana (Visser, 1992). One specific structure from the Forum that I want to focus on is Mussolini’s obelisk. Obelisks originated in Ancient Egypt but were imported and used to decorate Rome by the Emporer Augustus Caesar in 10 a.d. Since they were first imported to Rome, obelisks have signified the power and strength of individual rulers and emperors. In 1932, Mussolini ordered the creation of this obelisk in honor of himself and the fascist party. The statue exemplifies how Mussolini used Roman iconography and art in propaganda creations to bolster his self-image (Tucci, 2020). Even though the obelisk is a simple geometric form, Mussolini’s iteration is noticeably different and has elements of fascism in the design. There is a more complex base structure and Latin inscriptions on the side, rather than Egyptian hieroglyphics. By recreating Roman architectural tradition in his own honor, Mussolini is using the statue as a form of propaganda to associate himself with the greatness of the Roman empire.

During Mussolini’s rise to power and his time in control of fascist Italy, he used propaganda through the form of posters, language, architecture, and more to impose fascist beliefs and ideals on the people of Italy. One of the main ways Mussolini legitimized himself and communicated his power was through the use and incorporation of Roman symbols, language, and traditions. By aligning himself with the greatness of the Roman Empire, Mussolini used propaganda to attempt to write himself into history alongside emperors, kings, and great leaders. Mussolini incorporated the Latin language and Roman architecture throughout fascist Italy as propaganda to convince Italy and the world of his greatness. More than 100 years later, history does not look kindly on fascism and Mussolini’s propaganda represents an era of hatred and cruelty.

Citations

Cheles, Luciano. (2016). Iconic images in propaganda. Modern Italy : Journal of the Association for the Study of Modern Italy , 21 (4), 453–478. https://doi.org/10.1017/mit.2016.55

Dennis P. Doordan. (1997). In the Shadow of the Fasces: Political Design in Fascist Italy. Design Issues, 13 (1), 39-52.

Corduwener, Pepijn. (2014). Fascist past, present and future? The multiple usages of the Roman Empire in Mussolini’s Italy. Incontri (Amsterdam, Netherlands) , 29 (1), 136. https://doi.org/10.18352/incontri.9790

Lamers, Han, & Reitz-Joosse, Bettina. (2016). Lingua Lictoria: The Latin Literature of Italian Fascism. Classical Receptions Journal, 8 (2), 216-252.

Romke Visser. (1992). Fascist Doctrine and the Cult of the Romanita. Journal of Contemporary History, 27 (1), 5-22.

Tucci, Pier Luigi. (2020). EPHEMERAL ARCHITECTURE AND ROMANITÀ IN THE FASCIST ERA: A ROYAL-IMPERIAL TRIBUNE FOR HITLER AND MUSSOLINI IN ROME. Papers of the British School at Rome, 1-45.

Share this:

Published by daniellefeinstein

View all posts by daniellefeinstein

Leave a comment Cancel reply

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- HISTORY & CULTURE

How Mussolini led Italy to fascism—and why his legacy looms today

Although ultimately disgraced, the Italian dictator's memory still haunts the nation a century after toppling the government and ushering in an age of brutality.

In October 1922, a storm was gathering over Italy. Fascism—a political movement that harnessed discontent with a potent brew of nationalism, populism, and violence—would soon engulf the embattled nation and much of the world.

Benito Mussolini, the leader of the Italian movement, had amassed a strong following and began to call for the government to hand over power.

“We are at the point when either the arrow shoots forth or the tightly drawn bowstring breaks!” he said during a speech at a rally in Naples on October 24 of that year. “Our program is simple. We want to govern Italy.” He told supporters that if the government did not resign, they must march on Rome. Four days later, they did just that—leaving chaos in their wake as Mussolini seized control.

Mussolini’s name is still often invoked in the country as a brutal dictator though some still revere him as a hero. But how did he rise to power and what exactly happened during that fateful march that toppled Italy’s government? Here’s what you need to know.

How Mussolini founded Italian fascism

Fascism galvanized a growing nationalist movement in Europe born in the face of the First World War and the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, in which Russian socialists overthrew the Russian Empire. ( Learn more about the causes and effects of WWI .)

In Italy, Mussolini led the way to fascism. Born on July 29, 1883, in small-town southern Italy to a blacksmith father and a schoolteacher mother, he grew up on his socialist father’s stories of nationalism and political heroism. Shy and socially awkward, he ran into trouble at an early age due to his intransigence and violence against his classmates. As a young adult, he moved to Switzerland and became an avowed socialist. Eventually, he made his way back to Italy and established himself as a socialist journalist.

When war broke out across Europe in 1914, Italy at first remained neutral. Mussolini wanted Italy to join the war—putting him at odds with the Italian Socialist Party, which expelled him due to his pro-war advocacy. In response, he formed his own political movement, the Fasces of Revolutionary Action, aimed at encouraging entry into the war. (Italy eventually joined the fray in 1915.)

FREE BONUS ISSUE

In ancient Rome, the word fasces referred to a weapon consisting of a bundle of wooden rods, sometimes surrounding an ax. Used by Roman authorities to punish wrongdoers, the fasces came to represent state authority. In the 19th century, Italians had begun to use the word for political groups bound by common aims.

Mussolini was increasingly convinced that society should organize itself not along lines of social class or political affiliation, but around a strong national identity. He believed that only a “ruthless and energetic” dictator could make a “clean sweep” of Italy and restore it to its national promise.

Support for fascism grows

Mussolini was not alone: In the wake of the war, many Italians were chagrined by the Treaty of Versailles . They felt the treaty, which carved up the territory of the aggressor nations, disrespected Italy by awarding it far too little land. This “mutilated victory” would shape Italy’s future. ( How the Treaty of Versailles ended WWI and started WWII .)

In 1919, Mussolini founded a paramilitary movement he called the Italian Fasces of Combat. A successor to the Fasces of Revolutionary Action, this combat-focused squad aimed to mobilize war-hardened veterans who could return glory to Italy.

Mussolini hoped to translate the nation’s discontent into political success, but the young party suffered a humiliating defeat in that year’s parliamentary election. Mussolini only garnered 2,420 votes compared with the Socialist Party’s 1.8 million, delighting his enemies in Milan who held a fake funeral in his honor.

Undeterred, Mussolini began courting other groups who were at odds with socialists: industrialists and businessmen who feared strikes and slowdowns, rural landowners who feared losing their land, and members of political parties who feared socialism’s growing popularity.

Mussolini’s powerful new allies helped finance his movement’s paramilitary wing, known as “the Blackshirts.” Though Mussolini professed to stand against oppression and censorship of all kinds, the group quickly became known for its willingness to use violence for political gain.

The Blackshirts terrorized socialists and Mussolini’s personal enemies nationwide. The year 1920 was bloody, with fascists marching through towns, beating and even killing labor leaders, and effectively taking over local authority. But the Italian government, which shared the fascists’ enmity with socialists, did little to stem the violence.

Mussolini’s rise to power

Though in reality Mussolini only controlled a fraction of the militia members, their tough image helped build his reputation as a powerful, authoritative leader capable of backing up his words with violent and decisive action. Known as Il Duce, (the Duke), he exercised a powerful influence over Italians, seducing them with his personal charm and persuasive rhetoric.

In 1921, Mussolini won a seat in parliament and was even invited to join the coalition government by Italy’s Prime Minister Giovanni Giolitti—who assumed that Mussolini would bring his Blackshirts to heel once he was given a share of the political power.

But Giolitti had misjudged Mussolini, who instead intended to use his Blackshirts to seize absolute control. In late 1921, Mussolini transformed the group into the National Fascist Party, translating a movement that had numbered about 30,000 in 1920 into a political party 320,000 members strong. Although he had effectively declared war against the state, the Italian government was powerless to dissolve the party and stood by as fascists took over most of northern Italy.

Mussolini saw his opening in summer 1922. Socialists had announced a strike that historian Ararat Gocmen writes was “not in the name of workers’ emancipation but in a desperate cry for the state to bring an end to fascist violence.” Mussolini positioned the strike as proof that the government was weak and incapable of rule. With new supporters who wanted law and order, Mussolini decided it was time to seize power.

The March on Rome

On October 25, 1922, a day after his rally in Naples, Mussolini appointed four party leaders to lead members into the nation’s capital. Poorly trained and outfitted, these men would likely have lost a battle with Italy’s army. But Mussolini intended to intimidate the government into submission.

Fascist battalions were to congregate outside of Rome. If the prime minister did not give the fascists power—and King Victor Emmanuel III did not subsequently recognize his authority—his waiting men would march into the capital and seize control.

While Mussolini lingered in Milan, his supporters gathered. They left chaos in their wake, taking over government buildings in towns they passed through en route to Rome. Though the party consistently overstated their numbers, historian Katy Hull notes , fewer than 30,000 men joined the march.

Luigi Facta, then the prime minister, attempted to impose martial law. But the king thought Mussolini could usher in stability and refused to sign the order that would have mobilized Italian troops against the fascists.

In protest, Facta and his cabinet resigned the morning of October 28. Armed with a telegram from the king inviting him to form a cabinet, Mussolini boarded a sleeper car and took a leisurely, 14-hour journey from Milan to Rome. On October 30, he became prime minister—and ordered his men to parade before the king’s residence as they left the city.

The fall of Mussolini—and fascism’s legacy

The king, exhausted by the world war and a state of near civil war in Italy, had assumed Mussolini would impose order. But within three years, the strongman would be an outright dictator—and Victor Emmanuel let him do as he pleased.

Over the years, Mussolini increased his own power while chipping away at the population’s civil rights and forming a propagandistic police state. His agenda also went beyond domestic affairs. Mussolini’s imperial ambitions led Italy to occupy the Greek island of Corfu, invade Ethiopia, and ally itself with Nazi Germany, eventually resulting in the murder of 8,500 Italians in the Holocaust.

Mussolini’s ambition would be his downfall. Though he led Italy into World War II as an Axis power aligned with the seemingly unstoppable Adolf Hitler, he presided over the destruction of much of his country. Victor Emmanuel III convinced Mussolini’s closest allies to turn against him and, on July 25, 1943, they finally succeeded in removing him from power and placing him under arrest. ( Subscriber exclusive: Hear stories from the last voices of World War II .)

After a dramatic prison break, Mussolini fled to German-occupied Italy, where, under pressure from Hitler, he formed a weak and short-lived puppet state. On April 28, 1945, as an Allied victory neared, Mussolini attempted to flee the country. He was intercepted by communist partisans, who shot him and dumped his body in a public square in Milan.

Soon, a crowd gathered, desecrating the dictator’s corpse and venting years of hatred and loss. His barely recognizable body was eventually deposited in an unmarked grave. Il Duce was dead. But his legacy still haunts Italy today—and the fascist movement he pioneered remains alive both in Italian politics and the international imagination.

- Perpetual Planet

- Environment

- Paid Content

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- Photography

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Culture

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business History

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Methodology

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Theory

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

10 Propaganda and Youth

Patrizia Dogliani is Professor of Contemporary History at the University of Bologna (Italy). Her publications include Italia fascista 1922–1940 (Milan, 1999), Storia dei Giovani (Milan, 2003), and Storia sociale delfascismo (Turin, forthcoming).

- Published: 18 September 2012

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Throughout its history, Italian fascism emphasized that it was a revolutionary and youthful phenomenon. During its rise from 1919 to 1922, the fascist movement, like its communist competitor, was novel in its appeal to youth. Fascism entailed the rejuvenation of the national political class of Liberal days and fostered a social and economic transformation whereby members of a middle class lacking an ancient inheritance of land and professional qualification could take up the reins of power. Most of the fascist leadership under the dictatorship were men born in the mid-1890s, framed by their experience of the First World War as twenty-year-olds. Fascism similarly could count on support from the next generation, a group who had only just been old enough to join in the last months of battle or who had missed the war altogether and felt frustrated at their loss.

W as fascism a generational revolt? Certainly, throughout its history, Italian Fascism emphasized that it was a revolutionary and youthful phenomenon. Moreover, during its rise from 1919 to 1922, the fascist movement, like its communist competitor, was novel in its appeal to youth and in the salient place that youth took in its ranks. Fascism did entail the rejuvenation of the national political class of Liberal days and fostered a social and economic transformation whereby members of a middle class lacking an ancient inheritance of land and professional qualification could take up the reins of power. Most of the fascist leadership under the dictatorship were menborninthe mid-189os, framed by their experience of the First World War as 20-year-olds, animated by their participation in the squadrism of the early days of their movement, and then, if they survived the internal struggles at the time of fascism's installation in government, they found themselves in their forties at the head of their country. 1

Fascism similarly could count on support from the next generation, sometimes called the ‘class of 1899’, agroup whohad only just been oldenoughtojoinin the last months of battle or who had missed the war altogether and felt frustrated at their loss. Contemporaries noted their existence: ‘the most interesting feature of the uprising that has come with the formation of the Mussolini cabinet is the appearance on the political scene of the very young, adolescents from 15 to 20 who did not serve in the war.’ 2 The desire for action, the emulation of elder brothers, accompanied by a profound crisis of family bonds and of adult authority, had pushed adolescents into squadrism. ‘The civil war is the war between a generation of the very young who did not experience the last gasp of the war’, who willingly placed themselves under the guidance of others still young who had fought the war and who now acted as instructors of their younger brothers, combining to become ‘a historic generation’. These youngsters, excluded from the ranks of the Associazione Nazionale dei Combattenti (National Returned Soldiers' Association), adopted rites, rules, symbols, and the black shirts of the fighting elite of the arditi. They also expressed themselves in violence, particularly directed against people and property of the left. It was a pattern repeated in the mayhem found in Weimar Germany or Spain of the Second Republic, with radical activity combining with often still confused political objectives. In Italy, local studies, one on Venice for example, 3 can display revolutionary and counter-revolutionary youth groups that are sure in their definition. Only after the March on Rome did the Fascist militia, the Milizia Voluntaria per la Sicurezza Nazionale (MVSN), absorb them, thereby papering over the differences that had existed between D'Annunzians from Fiume, Nationalists, and anarcho-syndicalists. In the light of this experience, the Fascist ruling elite, once from 1925 secure in power, was aware of the need to watch over the younger generation in order to avoid conflict among and with them, and to retain youth as faithful followers of the regime.

I. The New Fascist Cohort

From its beginning the regime was determined to fascistize the new generation. In the so-called corporate order with its plan to organize society through work roles, gender, and ages, the devotion to youth was highly developed and, in most senses, successful. Yet, few historians, whether Italian or not, have focused on the complex organization of the young. The only serious monograph was written more than twenty years ago by Tracy Koon and has never been translated into Italian. 4 A gender approach is even weaker and little has been published on the difficult issue of the fascist organization of girls and young women. Certainly both sexes were put through stages of Party instruction, with a steady multiplication of ideological intervention. The youth movement therefore constituted the most evident and perhaps the only genuine mass fascist organization. Key developments in this story occurred in 1926, 1929,and 1937. After the levels of turbulence within the Party prompted a major purge—more than 2,000 leaders and about 140,000 members were expelled—from 1925 membership was expected and to be given mainly to the civil service class. However, from 1927, the procedure became instead that entry occurred when an Italian was between 18 and 20 and depended on previous participation in the Party's youth movements, which therefore became the places of training, selection, and recruitment for the regime's political and administration leadership.

In the troubled immediate post-war, the first Party youth organizations had sprung up mainly in cities and in the north of the country. At Milan on 20 January 1920 an Avanguardia Studentesca (Student Vanguard) was created within the Fasci di Combattimento but, for the moment, the allure of Fiume and D Annunzio was stronger than that of Mussolini. Further student vanguards, led by the Fiuman ‘legionary’ Luigi Freddi came into existence in other sectors of the centre-north, notably Liguria and Emilia Romagna. The fascist leadership was suspicious of their independence and, at the Party congress in Rome in March 1921 that saw the birth of the Fascist Party, no youth delegates were admitted. Soon, however, the leadership turned its attention to youth, in December 1921 marshalling boys between the ages of 14 and 17 into the Avanguardia Giovanile Fascista. Later, in March 1923,atGenoa, the Fascist University Groups (Gruppi Universitari Fascisti; GUF) were founded. A month earlier, children and adolescents between the ages of 8 and 14 began to be enrolled into the so-called Balilla, utilizing the name of a boy of the people, who, in that city on 5 December 1746, had allegedly thrown the first stone that unleashed a popular revolt against Austrian occupiers. 5 Yet, in 1924, the number of children who were fascists only tallied 3,000,with 50,000 Avanguardisti. To enhance this situation, the regime would seek both to improve its organization and to destroy its rivals in the field, and this it could only do after the formal cancellation of democratic liberties with the full assumption of dictatorship in 1925.

On 3 April 1926, ‘Year IV of the Fascist Revolution’, the Opera Nazionale Balilla (ONB) ‘for the physical and moral benefit of youth’ was instituted by decree. It was to be an autonomous ente , with the task of instructing boys, initially from 8 to 18 but gradually extending to younger groups, and from the decree of 30 October 1934 achieving an articulated structure. There were now three categories for boys: Figli della Lupa (Sons of the She-Wolf) from 6 to 8; Balilla proper at 8,andat11 ‘Balilla Moschettiere’, before an upgrading at 14 to the Avanguardisti (Avanguardisti Moschettieri from 15 to 17). For girls there was an analogous structure, being Figlie della Lupa(6 to 8), Piccole Italiane (Little Italians) from 8 to 13, and then Giovani Italiane (Young Italian Women) from 14 to 17 (at first, females were placed under the Fasci Femminili and not the ONB). In 1929, formal control over the movement was passed by the Party to the Ministry of National Education which created an under-secretaryship for physical training and unified both boys and girls under the general school programme. In practice, however, the regime long continued to pay more attention to the physical and political instruction of males rather than of females. The organization was placed under the supervision of provincial committees and given its own rigid command structure, leading down through at least five ranks from the caposquadra toahumblecadet.

The transfer of the ONB to the Ministry was an important step given that it spread the movement in a capillary fashion through the entire schooling system and made membership obligatory for all boys and girls in elementary school, from the age of 6 to 11, with the teachers acting as propaganda agents. The perfecting of this organization coincided with the banning of any alternative ‘free time’ groups; the left and the original lay ‘Scouts’ (with its international connections) were suppressed in 1927, while the Catholic scouting organization, the Esploratori (Explorers), went into ‘voluntary’ dissolution in 1928. This process left only three Catholic youth organizations surviving—Azione Cattolica (AC; Catholic Action), the Federazione Universitaria Cattolica Italiana (FUCI; Italian Catholic university student federation) and the Movimento Laureati Cattolici (Catholic graduate association). The Lateran Pacts between church and state in 1929, in maintaining these bodies, led to fiurtherconflict, resolvedin 1931 with an accord whereby AC and FUCI were to devote themselves exclusively to the religious needs of their members, while the church took on a major role in the spiritual education of youth in the ONB. 6 Young Catholics thus did retain the potential to opt for a ‘double militancy’, both in the ONB and in the church groups and, especially, in the university associations. It has been estimated that such young men and women amounted to 15 per cent of those who passed through the regime's youth organizations under the dictatorship.

Although it is true that, until the passing of the Carta della Scuola (School Charter) in 1939, it was still technically possible to avoid membership of the ONB, belonging did bring social privileges and economic benefits of considerable significance, especially to the poorer classes. In 1934, a set of special scholarships and entitlements was instituted under direct ONB management, while, from 1929,the organization had taken responsibility for the teaching infrastructure needed in Italian communities abroad, first in the Mediterranean regions and then with a developing interest in other continents, notably the Americas. Furthermore, within Italy, a failure to join the ONB brought down discrimination on errant children, isolating them from the rest of society, ensuring that their family was suspected of anti-fascism, blocking any career in wide strands of the public service, and influencing the territorial placement of a boy when subject to call-up (or having him sent straight to a punishment battalion). By contrast, admission to colleges viewed as elite, notably in the military area (the naval college at Bari or the air force one at Forli being examples) demanded an ONB background and then offered advantagesbothinamilitarycareerorintheemploymentstructuresofthefascist state.

The ONB was built like a pyramid. Teachers and members of the MVSN, assisted by priests and especially military chaplains, concentrated on local and provincial discipline. The provincial branches of the ONB sent members to the national council, chosen by Mussolini and the national secretary of the ONB, and typically combining men from the MVSN, armed services, with the addition of an Inspector General of the clergy. Until 1930, the MVSN had the task of preparing young men for Party membership, essentially through a form of pre-military training, in preparation for military call-up which usually happened after boys turned 21.Young women could move directly into the PNF's women's organizations. Eventually the Party decided to insert another step in the political formation of youth and, in 1931, opened for those aged from 18 to 21 Giovani Fasciste for young women and Fasci Giovanili di Combattimento for young men. Each was granted its own autonomy within the Party and aimed at political, military, and sporting training. Their commander was Carlo Scorza (b. 1895), with a background in Tuscan squadrism. The young people thus marshalled were deemed the new ‘cohort’ of fascism, the direct heirs of the arditi of the Great War and of the ‘martyrs of the Party's rise to power. 7 Eighteen-year-old boys now officially joined the Party's ‘new militia’, while girls should concentrate on ‘the social and family preparation of the fascist woman’, under the lead of the Fasci Femminili. From 1930,the weekly Gioventù fascista (Fascist Youth), edited by the successive PNF secretaries, Giovanni Giuriati and Achille Starace, was directed at such youth.

In December 1934, military training was made compulsory for the able-bodied male population at the age of 18,whileboysfrom8 to 14 were now to be trained ‘morally and spiritually for national defence. At 14, they began a special gymnastic and sporting campaign, while those who missed out on the call-up were obliged to take courses in technical-military skills. In 1934, adults, too, were forced to undergo military instruction, notably during the afternoon of the ‘Fascist Saturday’, allegedly time off granted to the nation by employers.

These courses were widely regarded as boring and useless, devoted to parades and Party flag waving, gymnastics, and other officially choreographed ceremonies. Moreover, where the Party was not particularly active, the young could escape from pre-military training and ideological preaching. Yet, everywhere that they were available, sporting and other forms of physical recreation produced by the ONB or the Fasci Giovanili seem to have been crowded and popular. Even the clandestine anti-fascist parties, especially the Communists (PCd I), admitted that, from 1927–8, ‘sport is the means that has given fascism the best results in its ambitions to “neutralize youth”’ and was doing so whether through the ONB or the so-called Dopolavoro (OND) or ‘after-work organization’ which had attracted the voluntary and enthusiastic support of thousands of young from the working class. 8

Even if much sporting activity remained in practice confined to the elite as is revealed in the elegant pages of the monthly Lo sport fascista , where reports of sporting events are interspersed with advertisements about cinema, fashion, and items to be consumed by the upper middle class, the PNF and the national Olympic Committee (CONI) did facilitate sporting activity and bring sporting fame to some young people from poor backgrounds. During the second half of the 1930s, prizes and honours to be won by young athletes multiplied. 9 From 1932,elite university students could participate in the so-called Littoriali dello sport (Lictors’ sporting games), joined the following year by Littoriali della cultura e dell’ arte,and from 1938, open to women students, if participating in all arenas separately. From the end of 1939, CONI took authority for the Littoriali sportivi (Italy was scheduled to hold the Olympics in 1944) but, with the outbreak of war, they lost purpose and were abolished in 1941. Nonetheless, through the 1930s, sporting activities for women did expand, with the hope of imposing the athletic and healthy image of the fascist ‘new woman’, as embodied by the 20-year-olds ‘Ondina’ Valla and Claudia Testoni, who won medals at the 1936 Berlin Olympics. Similarly on the rise were mass alpine and skiing events, especially designed for Avanguardisti and the Fasci Giovanili. Forty-two thousand youth joined in such activities in 1936, almost as if they were another special cohort, and many of these skiers participated in the invasion of France and Greece in June and then October 1940,and in 1941 in the attack on the USSR. 10

By the middle of the 1930s, then, it was difficult to distinguish sport from military training, with the former embracing marching, wrestling, boxing, various kinds of shooting, and bomb throwing, meant to temper young fascists with a virile and military nature. Not even girls were absent from such pursuits, although, for them, most common were gymnastics of some planned and uniform type, aimed at fostering healthy and courageous mothers, primed to educate their own children in the love of the Nation. The Ministry of Education assisted the distribution through schools of patriotic and fascist literature directed at the young and the very young—ripping yarns about heroic acts, the biographies of the fighters and condottieri from classical Rome through to the present (with Benito Mussolini's own story at the forefront), talk about the ‘Famous Italians who had inspired fascism, ‘spiritual breviaries’ of a fascist slant, all made up a vast publication enterprise which seconded the already fascistized school textbooks, as available from the first elementary class to Liceo. 11

Nonetheless, the sharing of responsibility for organizing youth did in time prompt dispute between the regime's chiefs, especially the Minister of National Education by the end of the 1930s, Giuseppe Bottai, and Renato Ricci, put by Mussolini in charge of the new ONB in 1926.Ricci,likeScorza, belonged to the ‘Fascists of the first hour’ as they were called. From a working-class family, he had been a volunteer in 1915, a legionary with D Annunzio at Fiume, and eventually a squadrist in violently contested Tuscany. He participated in the March on Rome and was enrolled in the leading ranks of the MVSN. In 1924 he won a seat in parliament and, by the time he took over the ONB, was deputy secretary of the PNF. Mussolini believed this ardent and loyal young man, just into his thirties, was the ideal figure to head the new youth movement. For his part, Ricci, despite having no specific training in youth affairs, carried out his task zealously and with faith in his Duce. For this reason, despite prompting quite a few rumours about dubious financial dealings and other abuses of power, Ricci was always protected by Mussolini, who had long reflected before entrusting youth training to the Party. 12 The continuing dualism was, however, overcome in October 1937 with the creation of the umbrella organization called the Gioventù Italiana del Littorio (GIL; Italian Lictors’ Youth), taking as its motto Credere, obbedire, combattere (Believe, Obey, Fight). 13

Now, although the division by age and gender was preserved, the real novelty consisted in assigning everything to do with children and the young to the direct control of the Party and to its federal and provincial bodies. School retained its privileged position in recruitment. With the attack on Ethiopia in October 1935, the emphasis on military preparation deepened and was reinforced by co-opting into the leadership of GIL officers both from the army and from the MVSN. In June 1940, GIL established select brigades of those too young to join the armed forces. Called the battaglioni giovani fascisti (battalions of young fascists), in 1941, under the supervision of GIL while technically qualified as an army regiment, they were sent to fight in North Africa. At the same time, boys in middle school, called ‘aspirant officers’, were already being groomed to fill the army's ranks, helped by an intensive training at the so-called Campi Dux (Duce's camps), transformed by the war into academies of GIL.