Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

What is a Theoretical Framework? | A Step-by-Step Guide

Published on 14 February 2020 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 10 October 2022.

A theoretical framework is a foundational review of existing theories that serves as a roadmap for developing the arguments you will use in your own work.

Theories are developed by researchers to explain phenomena, draw connections, and make predictions. In a theoretical framework, you explain the existing theories that support your research, showing that your work is grounded in established ideas.

In other words, your theoretical framework justifies and contextualises your later research, and it’s a crucial first step for your research paper , thesis, or dissertation . A well-rounded theoretical framework sets you up for success later on in your research and writing process.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Why do you need a theoretical framework, how to write a theoretical framework, structuring your theoretical framework, example of a theoretical framework, frequently asked questions about theoretical frameworks.

Before you start your own research, it’s crucial to familiarise yourself with the theories and models that other researchers have already developed. Your theoretical framework is your opportunity to present and explain what you’ve learned, situated within your future research topic.

There’s a good chance that many different theories about your topic already exist, especially if the topic is broad. In your theoretical framework, you will evaluate, compare, and select the most relevant ones.

By “framing” your research within a clearly defined field, you make the reader aware of the assumptions that inform your approach, showing the rationale behind your choices for later sections, like methodology and discussion . This part of your dissertation lays the foundations that will support your analysis, helping you interpret your results and make broader generalisations .

- In literature , a scholar using postmodernist literary theory would analyse The Great Gatsby differently than a scholar using Marxist literary theory.

- In psychology , a behaviourist approach to depression would involve different research methods and assumptions than a psychoanalytic approach.

- In economics , wealth inequality would be explained and interpreted differently based on a classical economics approach than based on a Keynesian economics one.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

To create your own theoretical framework, you can follow these three steps:

- Identifying your key concepts

- Evaluating and explaining relevant theories

- Showing how your research fits into existing research

1. Identify your key concepts

The first step is to pick out the key terms from your problem statement and research questions . Concepts often have multiple definitions, so your theoretical framework should also clearly define what you mean by each term.

To investigate this problem, you have identified and plan to focus on the following problem statement, objective, and research questions:

Problem : Many online customers do not return to make subsequent purchases.

Objective : To increase the quantity of return customers.

Research question : How can the satisfaction of company X’s online customers be improved in order to increase the quantity of return customers?

2. Evaluate and explain relevant theories

By conducting a thorough literature review , you can determine how other researchers have defined these key concepts and drawn connections between them. As you write your theoretical framework, your aim is to compare and critically evaluate the approaches that different authors have taken.

After discussing different models and theories, you can establish the definitions that best fit your research and justify why. You can even combine theories from different fields to build your own unique framework if this better suits your topic.

Make sure to at least briefly mention each of the most important theories related to your key concepts. If there is a well-established theory that you don’t want to apply to your own research, explain why it isn’t suitable for your purposes.

3. Show how your research fits into existing research

Apart from summarising and discussing existing theories, your theoretical framework should show how your project will make use of these ideas and take them a step further.

You might aim to do one or more of the following:

- Test whether a theory holds in a specific, previously unexamined context

- Use an existing theory as a basis for interpreting your results

- Critique or challenge a theory

- Combine different theories in a new or unique way

A theoretical framework can sometimes be integrated into a literature review chapter , but it can also be included as its own chapter or section in your dissertation. As a rule of thumb, if your research involves dealing with a lot of complex theories, it’s a good idea to include a separate theoretical framework chapter.

There are no fixed rules for structuring your theoretical framework, but it’s best to double-check with your department or institution to make sure they don’t have any formatting guidelines. The most important thing is to create a clear, logical structure. There are a few ways to do this:

- Draw on your research questions, structuring each section around a question or key concept

- Organise by theory cluster

- Organise by date

As in all other parts of your research paper , thesis, or dissertation , make sure to properly cite your sources to avoid plagiarism .

To get a sense of what this part of your thesis or dissertation might look like, take a look at our full example .

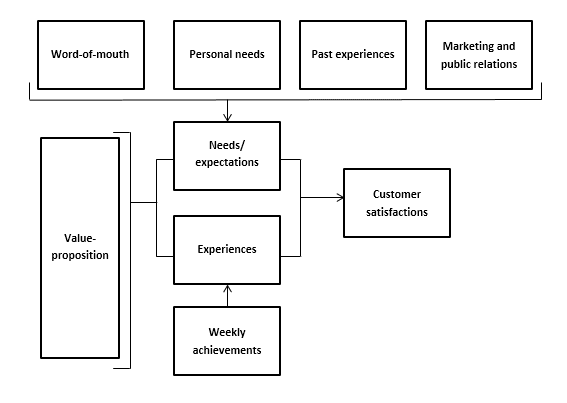

While a theoretical framework describes the theoretical underpinnings of your work based on existing research, a conceptual framework allows you to draw your own conclusions, mapping out the variables you may use in your study and the interplay between them.

A literature review and a theoretical framework are not the same thing and cannot be used interchangeably. While a theoretical framework describes the theoretical underpinnings of your work, a literature review critically evaluates existing research relating to your topic. You’ll likely need both in your dissertation .

A theoretical framework can sometimes be integrated into a literature review chapter , but it can also be included as its own chapter or section in your dissertation . As a rule of thumb, if your research involves dealing with a lot of complex theories, it’s a good idea to include a separate theoretical framework chapter.

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a dissertation , thesis, research paper , or proposal .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, October 10). What is a Theoretical Framework? | A Step-by-Step Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved 9 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/the-theoretical-framework/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a literature review | guide, template, & examples, how to write a results section | tips & examples, how to write a discussion section | tips & examples.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- CBE Life Sci Educ

- v.21(3); Fall 2022

Literature Reviews, Theoretical Frameworks, and Conceptual Frameworks: An Introduction for New Biology Education Researchers

Julie a. luft.

† Department of Mathematics, Social Studies, and Science Education, Mary Frances Early College of Education, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602-7124

Sophia Jeong

‡ Department of Teaching & Learning, College of Education & Human Ecology, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210

Robert Idsardi

§ Department of Biology, Eastern Washington University, Cheney, WA 99004

Grant Gardner

∥ Department of Biology, Middle Tennessee State University, Murfreesboro, TN 37132

Associated Data

To frame their work, biology education researchers need to consider the role of literature reviews, theoretical frameworks, and conceptual frameworks as critical elements of the research and writing process. However, these elements can be confusing for scholars new to education research. This Research Methods article is designed to provide an overview of each of these elements and delineate the purpose of each in the educational research process. We describe what biology education researchers should consider as they conduct literature reviews, identify theoretical frameworks, and construct conceptual frameworks. Clarifying these different components of educational research studies can be helpful to new biology education researchers and the biology education research community at large in situating their work in the broader scholarly literature.

INTRODUCTION

Discipline-based education research (DBER) involves the purposeful and situated study of teaching and learning in specific disciplinary areas ( Singer et al. , 2012 ). Studies in DBER are guided by research questions that reflect disciplines’ priorities and worldviews. Researchers can use quantitative data, qualitative data, or both to answer these research questions through a variety of methodological traditions. Across all methodologies, there are different methods associated with planning and conducting educational research studies that include the use of surveys, interviews, observations, artifacts, or instruments. Ensuring the coherence of these elements to the discipline’s perspective also involves situating the work in the broader scholarly literature. The tools for doing this include literature reviews, theoretical frameworks, and conceptual frameworks. However, the purpose and function of each of these elements is often confusing to new education researchers. The goal of this article is to introduce new biology education researchers to these three important elements important in DBER scholarship and the broader educational literature.

The first element we discuss is a review of research (literature reviews), which highlights the need for a specific research question, study problem, or topic of investigation. Literature reviews situate the relevance of the study within a topic and a field. The process may seem familiar to science researchers entering DBER fields, but new researchers may still struggle in conducting the review. Booth et al. (2016b) highlight some of the challenges novice education researchers face when conducting a review of literature. They point out that novice researchers struggle in deciding how to focus the review, determining the scope of articles needed in the review, and knowing how to be critical of the articles in the review. Overcoming these challenges (and others) can help novice researchers construct a sound literature review that can inform the design of the study and help ensure the work makes a contribution to the field.

The second and third highlighted elements are theoretical and conceptual frameworks. These guide biology education research (BER) studies, and may be less familiar to science researchers. These elements are important in shaping the construction of new knowledge. Theoretical frameworks offer a way to explain and interpret the studied phenomenon, while conceptual frameworks clarify assumptions about the studied phenomenon. Despite the importance of these constructs in educational research, biology educational researchers have noted the limited use of theoretical or conceptual frameworks in published work ( DeHaan, 2011 ; Dirks, 2011 ; Lo et al. , 2019 ). In reviewing articles published in CBE—Life Sciences Education ( LSE ) between 2015 and 2019, we found that fewer than 25% of the research articles had a theoretical or conceptual framework (see the Supplemental Information), and at times there was an inconsistent use of theoretical and conceptual frameworks. Clearly, these frameworks are challenging for published biology education researchers, which suggests the importance of providing some initial guidance to new biology education researchers.

Fortunately, educational researchers have increased their explicit use of these frameworks over time, and this is influencing educational research in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields. For instance, a quick search for theoretical or conceptual frameworks in the abstracts of articles in Educational Research Complete (a common database for educational research) in STEM fields demonstrates a dramatic change over the last 20 years: from only 778 articles published between 2000 and 2010 to 5703 articles published between 2010 and 2020, a more than sevenfold increase. Greater recognition of the importance of these frameworks is contributing to DBER authors being more explicit about such frameworks in their studies.

Collectively, literature reviews, theoretical frameworks, and conceptual frameworks work to guide methodological decisions and the elucidation of important findings. Each offers a different perspective on the problem of study and is an essential element in all forms of educational research. As new researchers seek to learn about these elements, they will find different resources, a variety of perspectives, and many suggestions about the construction and use of these elements. The wide range of available information can overwhelm the new researcher who just wants to learn the distinction between these elements or how to craft them adequately.

Our goal in writing this paper is not to offer specific advice about how to write these sections in scholarly work. Instead, we wanted to introduce these elements to those who are new to BER and who are interested in better distinguishing one from the other. In this paper, we share the purpose of each element in BER scholarship, along with important points on its construction. We also provide references for additional resources that may be beneficial to better understanding each element. Table 1 summarizes the key distinctions among these elements.

Comparison of literature reviews, theoretical frameworks, and conceptual reviews

This article is written for the new biology education researcher who is just learning about these different elements or for scientists looking to become more involved in BER. It is a result of our own work as science education and biology education researchers, whether as graduate students and postdoctoral scholars or newly hired and established faculty members. This is the article we wish had been available as we started to learn about these elements or discussed them with new educational researchers in biology.

LITERATURE REVIEWS

Purpose of a literature review.

A literature review is foundational to any research study in education or science. In education, a well-conceptualized and well-executed review provides a summary of the research that has already been done on a specific topic and identifies questions that remain to be answered, thus illustrating the current research project’s potential contribution to the field and the reasoning behind the methodological approach selected for the study ( Maxwell, 2012 ). BER is an evolving disciplinary area that is redefining areas of conceptual emphasis as well as orientations toward teaching and learning (e.g., Labov et al. , 2010 ; American Association for the Advancement of Science, 2011 ; Nehm, 2019 ). As a result, building comprehensive, critical, purposeful, and concise literature reviews can be a challenge for new biology education researchers.

Building Literature Reviews

There are different ways to approach and construct a literature review. Booth et al. (2016a) provide an overview that includes, for example, scoping reviews, which are focused only on notable studies and use a basic method of analysis, and integrative reviews, which are the result of exhaustive literature searches across different genres. Underlying each of these different review processes are attention to the s earch process, a ppraisa l of articles, s ynthesis of the literature, and a nalysis: SALSA ( Booth et al. , 2016a ). This useful acronym can help the researcher focus on the process while building a specific type of review.

However, new educational researchers often have questions about literature reviews that are foundational to SALSA or other approaches. Common questions concern determining which literature pertains to the topic of study or the role of the literature review in the design of the study. This section addresses such questions broadly while providing general guidance for writing a narrative literature review that evaluates the most pertinent studies.

The literature review process should begin before the research is conducted. As Boote and Beile (2005 , p. 3) suggested, researchers should be “scholars before researchers.” They point out that having a good working knowledge of the proposed topic helps illuminate avenues of study. Some subject areas have a deep body of work to read and reflect upon, providing a strong foundation for developing the research question(s). For instance, the teaching and learning of evolution is an area of long-standing interest in the BER community, generating many studies (e.g., Perry et al. , 2008 ; Barnes and Brownell, 2016 ) and reviews of research (e.g., Sickel and Friedrichsen, 2013 ; Ziadie and Andrews, 2018 ). Emerging areas of BER include the affective domain, issues of transfer, and metacognition ( Singer et al. , 2012 ). Many studies in these areas are transdisciplinary and not always specific to biology education (e.g., Rodrigo-Peiris et al. , 2018 ; Kolpikova et al. , 2019 ). These newer areas may require reading outside BER; fortunately, summaries of some of these topics can be found in the Current Insights section of the LSE website.

In focusing on a specific problem within a broader research strand, a new researcher will likely need to examine research outside BER. Depending upon the area of study, the expanded reading list might involve a mix of BER, DBER, and educational research studies. Determining the scope of the reading is not always straightforward. A simple way to focus one’s reading is to create a “summary phrase” or “research nugget,” which is a very brief descriptive statement about the study. It should focus on the essence of the study, for example, “first-year nonmajor students’ understanding of evolution,” “metacognitive prompts to enhance learning during biochemistry,” or “instructors’ inquiry-based instructional practices after professional development programming.” This type of phrase should help a new researcher identify two or more areas to review that pertain to the study. Focusing on recent research in the last 5 years is a good first step. Additional studies can be identified by reading relevant works referenced in those articles. It is also important to read seminal studies that are more than 5 years old. Reading a range of studies should give the researcher the necessary command of the subject in order to suggest a research question.

Given that the research question(s) arise from the literature review, the review should also substantiate the selected methodological approach. The review and research question(s) guide the researcher in determining how to collect and analyze data. Often the methodological approach used in a study is selected to contribute knowledge that expands upon what has been published previously about the topic (see Institute of Education Sciences and National Science Foundation, 2013 ). An emerging topic of study may need an exploratory approach that allows for a description of the phenomenon and development of a potential theory. This could, but not necessarily, require a methodological approach that uses interviews, observations, surveys, or other instruments. An extensively studied topic may call for the additional understanding of specific factors or variables; this type of study would be well suited to a verification or a causal research design. These could entail a methodological approach that uses valid and reliable instruments, observations, or interviews to determine an effect in the studied event. In either of these examples, the researcher(s) may use a qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods methodological approach.

Even with a good research question, there is still more reading to be done. The complexity and focus of the research question dictates the depth and breadth of the literature to be examined. Questions that connect multiple topics can require broad literature reviews. For instance, a study that explores the impact of a biology faculty learning community on the inquiry instruction of faculty could have the following review areas: learning communities among biology faculty, inquiry instruction among biology faculty, and inquiry instruction among biology faculty as a result of professional learning. Biology education researchers need to consider whether their literature review requires studies from different disciplines within or outside DBER. For the example given, it would be fruitful to look at research focused on learning communities with faculty in STEM fields or in general education fields that result in instructional change. It is important not to be too narrow or too broad when reading. When the conclusions of articles start to sound similar or no new insights are gained, the researcher likely has a good foundation for a literature review. This level of reading should allow the researcher to demonstrate a mastery in understanding the researched topic, explain the suitability of the proposed research approach, and point to the need for the refined research question(s).

The literature review should include the researcher’s evaluation and critique of the selected studies. A researcher may have a large collection of studies, but not all of the studies will follow standards important in the reporting of empirical work in the social sciences. The American Educational Research Association ( Duran et al. , 2006 ), for example, offers a general discussion about standards for such work: an adequate review of research informing the study, the existence of sound and appropriate data collection and analysis methods, and appropriate conclusions that do not overstep or underexplore the analyzed data. The Institute of Education Sciences and National Science Foundation (2013) also offer Common Guidelines for Education Research and Development that can be used to evaluate collected studies.

Because not all journals adhere to such standards, it is important that a researcher review each study to determine the quality of published research, per the guidelines suggested earlier. In some instances, the research may be fatally flawed. Examples of such flaws include data that do not pertain to the question, a lack of discussion about the data collection, poorly constructed instruments, or an inadequate analysis. These types of errors result in studies that are incomplete, error-laden, or inaccurate and should be excluded from the review. Most studies have limitations, and the author(s) often make them explicit. For instance, there may be an instructor effect, recognized bias in the analysis, or issues with the sample population. Limitations are usually addressed by the research team in some way to ensure a sound and acceptable research process. Occasionally, the limitations associated with the study can be significant and not addressed adequately, which leaves a consequential decision in the hands of the researcher. Providing critiques of studies in the literature review process gives the reader confidence that the researcher has carefully examined relevant work in preparation for the study and, ultimately, the manuscript.

A solid literature review clearly anchors the proposed study in the field and connects the research question(s), the methodological approach, and the discussion. Reviewing extant research leads to research questions that will contribute to what is known in the field. By summarizing what is known, the literature review points to what needs to be known, which in turn guides decisions about methodology. Finally, notable findings of the new study are discussed in reference to those described in the literature review.

Within published BER studies, literature reviews can be placed in different locations in an article. When included in the introductory section of the study, the first few paragraphs of the manuscript set the stage, with the literature review following the opening paragraphs. Cooper et al. (2019) illustrate this approach in their study of course-based undergraduate research experiences (CUREs). An introduction discussing the potential of CURES is followed by an analysis of the existing literature relevant to the design of CUREs that allows for novel student discoveries. Within this review, the authors point out contradictory findings among research on novel student discoveries. This clarifies the need for their study, which is described and highlighted through specific research aims.

A literature reviews can also make up a separate section in a paper. For example, the introduction to Todd et al. (2019) illustrates the need for their research topic by highlighting the potential of learning progressions (LPs) and suggesting that LPs may help mitigate learning loss in genetics. At the end of the introduction, the authors state their specific research questions. The review of literature following this opening section comprises two subsections. One focuses on learning loss in general and examines a variety of studies and meta-analyses from the disciplines of medical education, mathematics, and reading. The second section focuses specifically on LPs in genetics and highlights student learning in the midst of LPs. These separate reviews provide insights into the stated research question.

Suggestions and Advice

A well-conceptualized, comprehensive, and critical literature review reveals the understanding of the topic that the researcher brings to the study. Literature reviews should not be so big that there is no clear area of focus; nor should they be so narrow that no real research question arises. The task for a researcher is to craft an efficient literature review that offers a critical analysis of published work, articulates the need for the study, guides the methodological approach to the topic of study, and provides an adequate foundation for the discussion of the findings.

In our own writing of literature reviews, there are often many drafts. An early draft may seem well suited to the study because the need for and approach to the study are well described. However, as the results of the study are analyzed and findings begin to emerge, the existing literature review may be inadequate and need revision. The need for an expanded discussion about the research area can result in the inclusion of new studies that support the explanation of a potential finding. The literature review may also prove to be too broad. Refocusing on a specific area allows for more contemplation of a finding.

It should be noted that there are different types of literature reviews, and many books and articles have been written about the different ways to embark on these types of reviews. Among these different resources, the following may be helpful in considering how to refine the review process for scholarly journals:

- Booth, A., Sutton, A., & Papaioannou, D. (2016a). Systemic approaches to a successful literature review (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. This book addresses different types of literature reviews and offers important suggestions pertaining to defining the scope of the literature review and assessing extant studies.

- Booth, W. C., Colomb, G. G., Williams, J. M., Bizup, J., & Fitzgerald, W. T. (2016b). The craft of research (4th ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. This book can help the novice consider how to make the case for an area of study. While this book is not specifically about literature reviews, it offers suggestions about making the case for your study.

- Galvan, J. L., & Galvan, M. C. (2017). Writing literature reviews: A guide for students of the social and behavioral sciences (7th ed.). Routledge. This book offers guidance on writing different types of literature reviews. For the novice researcher, there are useful suggestions for creating coherent literature reviews.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORKS

Purpose of theoretical frameworks.

As new education researchers may be less familiar with theoretical frameworks than with literature reviews, this discussion begins with an analogy. Envision a biologist, chemist, and physicist examining together the dramatic effect of a fog tsunami over the ocean. A biologist gazing at this phenomenon may be concerned with the effect of fog on various species. A chemist may be interested in the chemical composition of the fog as water vapor condenses around bits of salt. A physicist may be focused on the refraction of light to make fog appear to be “sitting” above the ocean. While observing the same “objective event,” the scientists are operating under different theoretical frameworks that provide a particular perspective or “lens” for the interpretation of the phenomenon. Each of these scientists brings specialized knowledge, experiences, and values to this phenomenon, and these influence the interpretation of the phenomenon. The scientists’ theoretical frameworks influence how they design and carry out their studies and interpret their data.

Within an educational study, a theoretical framework helps to explain a phenomenon through a particular lens and challenges and extends existing knowledge within the limitations of that lens. Theoretical frameworks are explicitly stated by an educational researcher in the paper’s framework, theory, or relevant literature section. The framework shapes the types of questions asked, guides the method by which data are collected and analyzed, and informs the discussion of the results of the study. It also reveals the researcher’s subjectivities, for example, values, social experience, and viewpoint ( Allen, 2017 ). It is essential that a novice researcher learn to explicitly state a theoretical framework, because all research questions are being asked from the researcher’s implicit or explicit assumptions of a phenomenon of interest ( Schwandt, 2000 ).

Selecting Theoretical Frameworks

Theoretical frameworks are one of the most contemplated elements in our work in educational research. In this section, we share three important considerations for new scholars selecting a theoretical framework.

The first step in identifying a theoretical framework involves reflecting on the phenomenon within the study and the assumptions aligned with the phenomenon. The phenomenon involves the studied event. There are many possibilities, for example, student learning, instructional approach, or group organization. A researcher holds assumptions about how the phenomenon will be effected, influenced, changed, or portrayed. It is ultimately the researcher’s assumption(s) about the phenomenon that aligns with a theoretical framework. An example can help illustrate how a researcher’s reflection on the phenomenon and acknowledgment of assumptions can result in the identification of a theoretical framework.

In our example, a biology education researcher may be interested in exploring how students’ learning of difficult biological concepts can be supported by the interactions of group members. The phenomenon of interest is the interactions among the peers, and the researcher assumes that more knowledgeable students are important in supporting the learning of the group. As a result, the researcher may draw on Vygotsky’s (1978) sociocultural theory of learning and development that is focused on the phenomenon of student learning in a social setting. This theory posits the critical nature of interactions among students and between students and teachers in the process of building knowledge. A researcher drawing upon this framework holds the assumption that learning is a dynamic social process involving questions and explanations among students in the classroom and that more knowledgeable peers play an important part in the process of building conceptual knowledge.

It is important to state at this point that there are many different theoretical frameworks. Some frameworks focus on learning and knowing, while other theoretical frameworks focus on equity, empowerment, or discourse. Some frameworks are well articulated, and others are still being refined. For a new researcher, it can be challenging to find a theoretical framework. Two of the best ways to look for theoretical frameworks is through published works that highlight different frameworks.

When a theoretical framework is selected, it should clearly connect to all parts of the study. The framework should augment the study by adding a perspective that provides greater insights into the phenomenon. It should clearly align with the studies described in the literature review. For instance, a framework focused on learning would correspond to research that reported different learning outcomes for similar studies. The methods for data collection and analysis should also correspond to the framework. For instance, a study about instructional interventions could use a theoretical framework concerned with learning and could collect data about the effect of the intervention on what is learned. When the data are analyzed, the theoretical framework should provide added meaning to the findings, and the findings should align with the theoretical framework.

A study by Jensen and Lawson (2011) provides an example of how a theoretical framework connects different parts of the study. They compared undergraduate biology students in heterogeneous and homogeneous groups over the course of a semester. Jensen and Lawson (2011) assumed that learning involved collaboration and more knowledgeable peers, which made Vygotsky’s (1978) theory a good fit for their study. They predicted that students in heterogeneous groups would experience greater improvement in their reasoning abilities and science achievements with much of the learning guided by the more knowledgeable peers.

In the enactment of the study, they collected data about the instruction in traditional and inquiry-oriented classes, while the students worked in homogeneous or heterogeneous groups. To determine the effect of working in groups, the authors also measured students’ reasoning abilities and achievement. Each data-collection and analysis decision connected to understanding the influence of collaborative work.

Their findings highlighted aspects of Vygotsky’s (1978) theory of learning. One finding, for instance, posited that inquiry instruction, as a whole, resulted in reasoning and achievement gains. This links to Vygotsky (1978) , because inquiry instruction involves interactions among group members. A more nuanced finding was that group composition had a conditional effect. Heterogeneous groups performed better with more traditional and didactic instruction, regardless of the reasoning ability of the group members. Homogeneous groups worked better during interaction-rich activities for students with low reasoning ability. The authors attributed the variation to the different types of helping behaviors of students. High-performing students provided the answers, while students with low reasoning ability had to work collectively through the material. In terms of Vygotsky (1978) , this finding provided new insights into the learning context in which productive interactions can occur for students.

Another consideration in the selection and use of a theoretical framework pertains to its orientation to the study. This can result in the theoretical framework prioritizing individuals, institutions, and/or policies ( Anfara and Mertz, 2014 ). Frameworks that connect to individuals, for instance, could contribute to understanding their actions, learning, or knowledge. Institutional frameworks, on the other hand, offer insights into how institutions, organizations, or groups can influence individuals or materials. Policy theories provide ways to understand how national or local policies can dictate an emphasis on outcomes or instructional design. These different types of frameworks highlight different aspects in an educational setting, which influences the design of the study and the collection of data. In addition, these different frameworks offer a way to make sense of the data. Aligning the data collection and analysis with the framework ensures that a study is coherent and can contribute to the field.

New understandings emerge when different theoretical frameworks are used. For instance, Ebert-May et al. (2015) prioritized the individual level within conceptual change theory (see Posner et al. , 1982 ). In this theory, an individual’s knowledge changes when it no longer fits the phenomenon. Ebert-May et al. (2015) designed a professional development program challenging biology postdoctoral scholars’ existing conceptions of teaching. The authors reported that the biology postdoctoral scholars’ teaching practices became more student-centered as they were challenged to explain their instructional decision making. According to the theory, the biology postdoctoral scholars’ dissatisfaction in their descriptions of teaching and learning initiated change in their knowledge and instruction. These results reveal how conceptual change theory can explain the learning of participants and guide the design of professional development programming.

The communities of practice (CoP) theoretical framework ( Lave, 1988 ; Wenger, 1998 ) prioritizes the institutional level , suggesting that learning occurs when individuals learn from and contribute to the communities in which they reside. Grounded in the assumption of community learning, the literature on CoP suggests that, as individuals interact regularly with the other members of their group, they learn about the rules, roles, and goals of the community ( Allee, 2000 ). A study conducted by Gehrke and Kezar (2017) used the CoP framework to understand organizational change by examining the involvement of individual faculty engaged in a cross-institutional CoP focused on changing the instructional practice of faculty at each institution. In the CoP, faculty members were involved in enhancing instructional materials within their department, which aligned with an overarching goal of instituting instruction that embraced active learning. Not surprisingly, Gehrke and Kezar (2017) revealed that faculty who perceived the community culture as important in their work cultivated institutional change. Furthermore, they found that institutional change was sustained when key leaders served as mentors and provided support for faculty, and as faculty themselves developed into leaders. This study reveals the complexity of individual roles in a COP in order to support institutional instructional change.

It is important to explicitly state the theoretical framework used in a study, but elucidating a theoretical framework can be challenging for a new educational researcher. The literature review can help to identify an applicable theoretical framework. Focal areas of the review or central terms often connect to assumptions and assertions associated with the framework that pertain to the phenomenon of interest. Another way to identify a theoretical framework is self-reflection by the researcher on personal beliefs and understandings about the nature of knowledge the researcher brings to the study ( Lysaght, 2011 ). In stating one’s beliefs and understandings related to the study (e.g., students construct their knowledge, instructional materials support learning), an orientation becomes evident that will suggest a particular theoretical framework. Theoretical frameworks are not arbitrary , but purposefully selected.

With experience, a researcher may find expanded roles for theoretical frameworks. Researchers may revise an existing framework that has limited explanatory power, or they may decide there is a need to develop a new theoretical framework. These frameworks can emerge from a current study or the need to explain a phenomenon in a new way. Researchers may also find that multiple theoretical frameworks are necessary to frame and explore a problem, as different frameworks can provide different insights into a problem.

Finally, it is important to recognize that choosing “x” theoretical framework does not necessarily mean a researcher chooses “y” methodology and so on, nor is there a clear-cut, linear process in selecting a theoretical framework for one’s study. In part, the nonlinear process of identifying a theoretical framework is what makes understanding and using theoretical frameworks challenging. For the novice scholar, contemplating and understanding theoretical frameworks is essential. Fortunately, there are articles and books that can help:

- Creswell, J. W. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. This book provides an overview of theoretical frameworks in general educational research.

- Ding, L. (2019). Theoretical perspectives of quantitative physics education research. Physical Review Physics Education Research , 15 (2), 020101-1–020101-13. This paper illustrates how a DBER field can use theoretical frameworks.

- Nehm, R. (2019). Biology education research: Building integrative frameworks for teaching and learning about living systems. Disciplinary and Interdisciplinary Science Education Research , 1 , ar15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43031-019-0017-6 . This paper articulates the need for studies in BER to explicitly state theoretical frameworks and provides examples of potential studies.

- Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice . Sage. This book also provides an overview of theoretical frameworks, but for both research and evaluation.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORKS

Purpose of a conceptual framework.

A conceptual framework is a description of the way a researcher understands the factors and/or variables that are involved in the study and their relationships to one another. The purpose of a conceptual framework is to articulate the concepts under study using relevant literature ( Rocco and Plakhotnik, 2009 ) and to clarify the presumed relationships among those concepts ( Rocco and Plakhotnik, 2009 ; Anfara and Mertz, 2014 ). Conceptual frameworks are different from theoretical frameworks in both their breadth and grounding in established findings. Whereas a theoretical framework articulates the lens through which a researcher views the work, the conceptual framework is often more mechanistic and malleable.

Conceptual frameworks are broader, encompassing both established theories (i.e., theoretical frameworks) and the researchers’ own emergent ideas. Emergent ideas, for example, may be rooted in informal and/or unpublished observations from experience. These emergent ideas would not be considered a “theory” if they are not yet tested, supported by systematically collected evidence, and peer reviewed. However, they do still play an important role in the way researchers approach their studies. The conceptual framework allows authors to clearly describe their emergent ideas so that connections among ideas in the study and the significance of the study are apparent to readers.

Constructing Conceptual Frameworks

Including a conceptual framework in a research study is important, but researchers often opt to include either a conceptual or a theoretical framework. Either may be adequate, but both provide greater insight into the research approach. For instance, a research team plans to test a novel component of an existing theory. In their study, they describe the existing theoretical framework that informs their work and then present their own conceptual framework. Within this conceptual framework, specific topics portray emergent ideas that are related to the theory. Describing both frameworks allows readers to better understand the researchers’ assumptions, orientations, and understanding of concepts being investigated. For example, Connolly et al. (2018) included a conceptual framework that described how they applied a theoretical framework of social cognitive career theory (SCCT) to their study on teaching programs for doctoral students. In their conceptual framework, the authors described SCCT, explained how it applied to the investigation, and drew upon results from previous studies to justify the proposed connections between the theory and their emergent ideas.

In some cases, authors may be able to sufficiently describe their conceptualization of the phenomenon under study in an introduction alone, without a separate conceptual framework section. However, incomplete descriptions of how the researchers conceptualize the components of the study may limit the significance of the study by making the research less intelligible to readers. This is especially problematic when studying topics in which researchers use the same terms for different constructs or different terms for similar and overlapping constructs (e.g., inquiry, teacher beliefs, pedagogical content knowledge, or active learning). Authors must describe their conceptualization of a construct if the research is to be understandable and useful.

There are some key areas to consider regarding the inclusion of a conceptual framework in a study. To begin with, it is important to recognize that conceptual frameworks are constructed by the researchers conducting the study ( Rocco and Plakhotnik, 2009 ; Maxwell, 2012 ). This is different from theoretical frameworks that are often taken from established literature. Researchers should bring together ideas from the literature, but they may be influenced by their own experiences as a student and/or instructor, the shared experiences of others, or thought experiments as they construct a description, model, or representation of their understanding of the phenomenon under study. This is an exercise in intellectual organization and clarity that often considers what is learned, known, and experienced. The conceptual framework makes these constructs explicitly visible to readers, who may have different understandings of the phenomenon based on their prior knowledge and experience. There is no single method to go about this intellectual work.

Reeves et al. (2016) is an example of an article that proposed a conceptual framework about graduate teaching assistant professional development evaluation and research. The authors used existing literature to create a novel framework that filled a gap in current research and practice related to the training of graduate teaching assistants. This conceptual framework can guide the systematic collection of data by other researchers because the framework describes the relationships among various factors that influence teaching and learning. The Reeves et al. (2016) conceptual framework may be modified as additional data are collected and analyzed by other researchers. This is not uncommon, as conceptual frameworks can serve as catalysts for concerted research efforts that systematically explore a phenomenon (e.g., Reynolds et al. , 2012 ; Brownell and Kloser, 2015 ).

Sabel et al. (2017) used a conceptual framework in their exploration of how scaffolds, an external factor, interact with internal factors to support student learning. Their conceptual framework integrated principles from two theoretical frameworks, self-regulated learning and metacognition, to illustrate how the research team conceptualized students’ use of scaffolds in their learning ( Figure 1 ). Sabel et al. (2017) created this model using their interpretations of these two frameworks in the context of their teaching.

Conceptual framework from Sabel et al. (2017) .

A conceptual framework should describe the relationship among components of the investigation ( Anfara and Mertz, 2014 ). These relationships should guide the researcher’s methods of approaching the study ( Miles et al. , 2014 ) and inform both the data to be collected and how those data should be analyzed. Explicitly describing the connections among the ideas allows the researcher to justify the importance of the study and the rigor of the research design. Just as importantly, these frameworks help readers understand why certain components of a system were not explored in the study. This is a challenge in education research, which is rooted in complex environments with many variables that are difficult to control.

For example, Sabel et al. (2017) stated: “Scaffolds, such as enhanced answer keys and reflection questions, can help students and instructors bridge the external and internal factors and support learning” (p. 3). They connected the scaffolds in the study to the three dimensions of metacognition and the eventual transformation of existing ideas into new or revised ideas. Their framework provides a rationale for focusing on how students use two different scaffolds, and not on other factors that may influence a student’s success (self-efficacy, use of active learning, exam format, etc.).

In constructing conceptual frameworks, researchers should address needed areas of study and/or contradictions discovered in literature reviews. By attending to these areas, researchers can strengthen their arguments for the importance of a study. For instance, conceptual frameworks can address how the current study will fill gaps in the research, resolve contradictions in existing literature, or suggest a new area of study. While a literature review describes what is known and not known about the phenomenon, the conceptual framework leverages these gaps in describing the current study ( Maxwell, 2012 ). In the example of Sabel et al. (2017) , the authors indicated there was a gap in the literature regarding how scaffolds engage students in metacognition to promote learning in large classes. Their study helps fill that gap by describing how scaffolds can support students in the three dimensions of metacognition: intelligibility, plausibility, and wide applicability. In another example, Lane (2016) integrated research from science identity, the ethic of care, the sense of belonging, and an expertise model of student success to form a conceptual framework that addressed the critiques of other frameworks. In a more recent example, Sbeglia et al. (2021) illustrated how a conceptual framework influences the methodological choices and inferences in studies by educational researchers.

Sometimes researchers draw upon the conceptual frameworks of other researchers. When a researcher’s conceptual framework closely aligns with an existing framework, the discussion may be brief. For example, Ghee et al. (2016) referred to portions of SCCT as their conceptual framework to explain the significance of their work on students’ self-efficacy and career interests. Because the authors’ conceptualization of this phenomenon aligned with a previously described framework, they briefly mentioned the conceptual framework and provided additional citations that provided more detail for the readers.

Within both the BER and the broader DBER communities, conceptual frameworks have been used to describe different constructs. For example, some researchers have used the term “conceptual framework” to describe students’ conceptual understandings of a biological phenomenon. This is distinct from a researcher’s conceptual framework of the educational phenomenon under investigation, which may also need to be explicitly described in the article. Other studies have presented a research logic model or flowchart of the research design as a conceptual framework. These constructions can be quite valuable in helping readers understand the data-collection and analysis process. However, a model depicting the study design does not serve the same role as a conceptual framework. Researchers need to avoid conflating these constructs by differentiating the researchers’ conceptual framework that guides the study from the research design, when applicable.

Explicitly describing conceptual frameworks is essential in depicting the focus of the study. We have found that being explicit in a conceptual framework means using accepted terminology, referencing prior work, and clearly noting connections between terms. This description can also highlight gaps in the literature or suggest potential contributions to the field of study. A well-elucidated conceptual framework can suggest additional studies that may be warranted. This can also spur other researchers to consider how they would approach the examination of a phenomenon and could result in a revised conceptual framework.

It can be challenging to create conceptual frameworks, but they are important. Below are two resources that could be helpful in constructing and presenting conceptual frameworks in educational research:

- Maxwell, J. A. (2012). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach (3rd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. Chapter 3 in this book describes how to construct conceptual frameworks.

- Ravitch, S. M., & Riggan, M. (2016). Reason & rigor: How conceptual frameworks guide research . Los Angeles, CA: Sage. This book explains how conceptual frameworks guide the research questions, data collection, data analyses, and interpretation of results.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

Literature reviews, theoretical frameworks, and conceptual frameworks are all important in DBER and BER. Robust literature reviews reinforce the importance of a study. Theoretical frameworks connect the study to the base of knowledge in educational theory and specify the researcher’s assumptions. Conceptual frameworks allow researchers to explicitly describe their conceptualization of the relationships among the components of the phenomenon under study. Table 1 provides a general overview of these components in order to assist biology education researchers in thinking about these elements.

It is important to emphasize that these different elements are intertwined. When these elements are aligned and complement one another, the study is coherent, and the study findings contribute to knowledge in the field. When literature reviews, theoretical frameworks, and conceptual frameworks are disconnected from one another, the study suffers. The point of the study is lost, suggested findings are unsupported, or important conclusions are invisible to the researcher. In addition, this misalignment may be costly in terms of time and money.

Conducting a literature review, selecting a theoretical framework, and building a conceptual framework are some of the most difficult elements of a research study. It takes time to understand the relevant research, identify a theoretical framework that provides important insights into the study, and formulate a conceptual framework that organizes the finding. In the research process, there is often a constant back and forth among these elements as the study evolves. With an ongoing refinement of the review of literature, clarification of the theoretical framework, and articulation of a conceptual framework, a sound study can emerge that makes a contribution to the field. This is the goal of BER and education research.

Supplementary Material

- Allee, V. (2000). Knowledge networks and communities of learning . OD Practitioner , 32 ( 4 ), 4–13. [ Google Scholar ]

- Allen, M. (2017). The Sage encyclopedia of communication research methods (Vols. 1–4 ). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. 10.4135/9781483381411 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- American Association for the Advancement of Science. (2011). Vision and change in undergraduate biology education: A call to action . Washington, DC. [ Google Scholar ]

- Anfara, V. A., Mertz, N. T. (2014). Setting the stage . In Anfara, V. A., Mertz, N. T. (eds.), Theoretical frameworks in qualitative research (pp. 1–22). Sage. [ Google Scholar ]

- Barnes, M. E., Brownell, S. E. (2016). Practices and perspectives of college instructors on addressing religious beliefs when teaching evolution . CBE—Life Sciences Education , 15 ( 2 ), ar18. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.15-11-0243 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Boote, D. N., Beile, P. (2005). Scholars before researchers: On the centrality of the dissertation literature review in research preparation . Educational Researcher , 34 ( 6 ), 3–15. 10.3102/0013189x034006003 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Booth, A., Sutton, A., Papaioannou, D. (2016a). Systemic approaches to a successful literature review (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. [ Google Scholar ]

- Booth, W. C., Colomb, G. G., Williams, J. M., Bizup, J., Fitzgerald, W. T. (2016b). The craft of research (4th ed.). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brownell, S. E., Kloser, M. J. (2015). Toward a conceptual framework for measuring the effectiveness of course-based undergraduate research experiences in undergraduate biology . Studies in Higher Education , 40 ( 3 ), 525–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1004234 [ Google Scholar ]

- Connolly, M. R., Lee, Y. G., Savoy, J. N. (2018). The effects of doctoral teaching development on early-career STEM scholars’ college teaching self-efficacy . CBE—Life Sciences Education , 17 ( 1 ), ar14. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.17-02-0039 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cooper, K. M., Blattman, J. N., Hendrix, T., Brownell, S. E. (2019). The impact of broadly relevant novel discoveries on student project ownership in a traditional lab course turned CURE . CBE—Life Sciences Education , 18 ( 4 ), ar57. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.19-06-0113 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Creswell, J. W. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. [ Google Scholar ]

- DeHaan, R. L. (2011). Education research in the biological sciences: A nine decade review (Paper commissioned by the NAS/NRC Committee on the Status, Contributions, and Future Directions of Discipline Based Education Research) . Washington, DC: National Academies Press. Retrieved May 20, 2022, from www7.nationalacademies.org/bose/DBER_Mee ting2_commissioned_papers_page.html [ Google Scholar ]

- Ding, L. (2019). Theoretical perspectives of quantitative physics education research . Physical Review Physics Education Research , 15 ( 2 ), 020101. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dirks, C. (2011). The current status and future direction of biology education research . Paper presented at: Second Committee Meeting on the Status, Contributions, and Future Directions of Discipline-Based Education Research, 18–19 October (Washington, DC). Retrieved May 20, 2022, from http://sites.nationalacademies.org/DBASSE/BOSE/DBASSE_071087 [ Google Scholar ]

- Duran, R. P., Eisenhart, M. A., Erickson, F. D., Grant, C. A., Green, J. L., Hedges, L. V., Schneider, B. L. (2006). Standards for reporting on empirical social science research in AERA publications: American Educational Research Association . Educational Researcher , 35 ( 6 ), 33–40. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ebert-May, D., Derting, T. L., Henkel, T. P., Middlemis Maher, J., Momsen, J. L., Arnold, B., Passmore, H. A. (2015). Breaking the cycle: Future faculty begin teaching with learner-centered strategies after professional development . CBE—Life Sciences Education , 14 ( 2 ), ar22. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.14-12-0222 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Galvan, J. L., Galvan, M. C. (2017). Writing literature reviews: A guide for students of the social and behavioral sciences (7th ed.). New York, NY: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315229386 [ Google Scholar ]

- Gehrke, S., Kezar, A. (2017). The roles of STEM faculty communities of practice in institutional and departmental reform in higher education . American Educational Research Journal , 54 ( 5 ), 803–833. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831217706736 [ Google Scholar ]

- Ghee, M., Keels, M., Collins, D., Neal-Spence, C., Baker, E. (2016). Fine-tuning summer research programs to promote underrepresented students’ persistence in the STEM pathway . CBE—Life Sciences Education , 15 ( 3 ), ar28. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.16-01-0046 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Institute of Education Sciences & National Science Foundation. (2013). Common guidelines for education research and development . Retrieved May 20, 2022, from www.nsf.gov/pubs/2013/nsf13126/nsf13126.pdf

- Jensen, J. L., Lawson, A. (2011). Effects of collaborative group composition and inquiry instruction on reasoning gains and achievement in undergraduate biology . CBE—Life Sciences Education , 10 ( 1 ), 64–73. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.19-05-0098 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kolpikova, E. P., Chen, D. C., Doherty, J. H. (2019). Does the format of preclass reading quizzes matter? An evaluation of traditional and gamified, adaptive preclass reading quizzes . CBE—Life Sciences Education , 18 ( 4 ), ar52. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.19-05-0098 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Labov, J. B., Reid, A. H., Yamamoto, K. R. (2010). Integrated biology and undergraduate science education: A new biology education for the twenty-first century? CBE—Life Sciences Education , 9 ( 1 ), 10–16. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.09-12-0092 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lane, T. B. (2016). Beyond academic and social integration: Understanding the impact of a STEM enrichment program on the retention and degree attainment of underrepresented students . CBE—Life Sciences Education , 15 ( 3 ), ar39. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.16-01-0070 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lave, J. (1988). Cognition in practice: Mind, mathematics and culture in everyday life . New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lo, S. M., Gardner, G. E., Reid, J., Napoleon-Fanis, V., Carroll, P., Smith, E., Sato, B. K. (2019). Prevailing questions and methodologies in biology education research: A longitudinal analysis of research in CBE — Life Sciences Education and at the Society for the Advancement of Biology Education Research . CBE—Life Sciences Education , 18 ( 1 ), ar9. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.18-08-0164 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lysaght, Z. (2011). Epistemological and paradigmatic ecumenism in “Pasteur’s quadrant:” Tales from doctoral research . In Official Conference Proceedings of the Third Asian Conference on Education in Osaka, Japan . Retrieved May 20, 2022, from http://iafor.org/ace2011_offprint/ACE2011_offprint_0254.pdf

- Maxwell, J. A. (2012). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach (3rd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. [ Google Scholar ]

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis (3rd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nehm, R. (2019). Biology education research: Building integrative frameworks for teaching and learning about living systems . Disciplinary and Interdisciplinary Science Education Research , 1 , ar15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43031-019-0017-6 [ Google Scholar ]

- Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice . Los Angeles, CA: Sage. [ Google Scholar ]

- Perry, J., Meir, E., Herron, J. C., Maruca, S., Stal, D. (2008). Evaluating two approaches to helping college students understand evolutionary trees through diagramming tasks . CBE—Life Sciences Education , 7 ( 2 ), 193–201. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.07-01-0007 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Posner, G. J., Strike, K. A., Hewson, P. W., Gertzog, W. A. (1982). Accommodation of a scientific conception: Toward a theory of conceptual change . Science Education , 66 ( 2 ), 211–227. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ravitch, S. M., Riggan, M. (2016). Reason & rigor: How conceptual frameworks guide research . Los Angeles, CA: Sage. [ Google Scholar ]

- Reeves, T. D., Marbach-Ad, G., Miller, K. R., Ridgway, J., Gardner, G. E., Schussler, E. E., Wischusen, E. W. (2016). A conceptual framework for graduate teaching assistant professional development evaluation and research . CBE—Life Sciences Education , 15 ( 2 ), es2. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.15-10-0225 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Reynolds, J. A., Thaiss, C., Katkin, W., Thompson, R. J. Jr. (2012). Writing-to-learn in undergraduate science education: A community-based, conceptually driven approach . CBE—Life Sciences Education , 11 ( 1 ), 17–25. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.11-08-0064 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rocco, T. S., Plakhotnik, M. S. (2009). Literature reviews, conceptual frameworks, and theoretical frameworks: Terms, functions, and distinctions . Human Resource Development Review , 8 ( 1 ), 120–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484309332617 [ Google Scholar ]

- Rodrigo-Peiris, T., Xiang, L., Cassone, V. M. (2018). A low-intensity, hybrid design between a “traditional” and a “course-based” research experience yields positive outcomes for science undergraduate freshmen and shows potential for large-scale application . CBE—Life Sciences Education , 17 ( 4 ), ar53. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.17-11-0248 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sabel, J. L., Dauer, J. T., Forbes, C. T. (2017). Introductory biology students’ use of enhanced answer keys and reflection questions to engage in metacognition and enhance understanding . CBE—Life Sciences Education , 16 ( 3 ), ar40. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.16-10-0298 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sbeglia, G. C., Goodridge, J. A., Gordon, L. H., Nehm, R. H. (2021). Are faculty changing? How reform frameworks, sampling intensities, and instrument measures impact inferences about student-centered teaching practices . CBE—Life Sciences Education , 20 ( 3 ), ar39. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.20-11-0259 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schwandt, T. A. (2000). Three epistemological stances for qualitative inquiry: Interpretivism, hermeneutics, and social constructionism . In Denzin, N. K., Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 189–213). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sickel, A. J., Friedrichsen, P. (2013). Examining the evolution education literature with a focus on teachers: Major findings, goals for teacher preparation, and directions for future research . Evolution: Education and Outreach , 6 ( 1 ), 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/1936-6434-6-23 [ Google Scholar ]

- Singer, S. R., Nielsen, N. R., Schweingruber, H. A. (2012). Discipline-based education research: Understanding and improving learning in undergraduate science and engineering . Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Todd, A., Romine, W. L., Correa-Menendez, J. (2019). Modeling the transition from a phenotypic to genotypic conceptualization of genetics in a university-level introductory biology context . Research in Science Education , 49 ( 2 ), 569–589. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-017-9626-2 [ Google Scholar ]

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning as a social system . Systems Thinker , 9 ( 5 ), 2–3. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ziadie, M. A., Andrews, T. C. (2018). Moving evolution education forward: A systematic analysis of literature to identify gaps in collective knowledge for teaching . CBE—Life Sciences Education , 17 ( 1 ), ar11. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.17-08-0190 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

What is a framework? Understanding their purpose, value, development and use

- Articles with Attitude

- Open access

- Published: 14 April 2023

- Volume 13 , pages 510–519, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Stefan Partelow ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7751-4005 1 , 2

13k Accesses

4 Citations

18 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

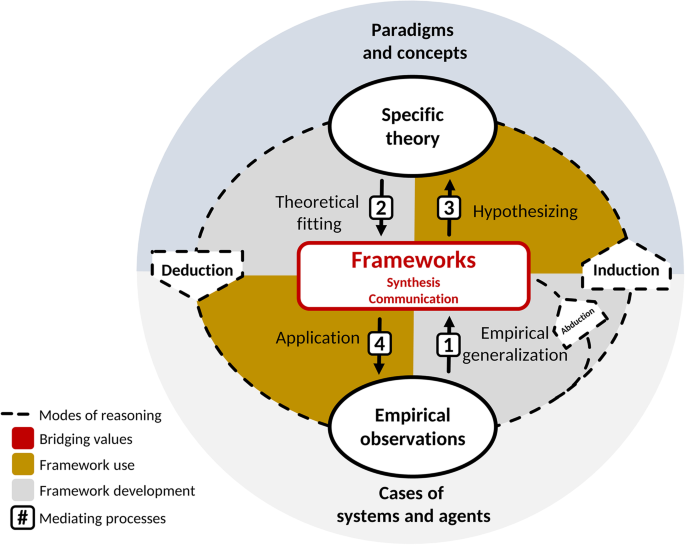

Many frameworks exist across the sciences and science-policy interface, but it is not always clear how they are developed or can be applied. It is also often vague how new or existing frameworks are positioned in a theory of science to advance a specific theory or paradigm. This article examines these questions and positions the role of frameworks as integral but often vague scientific tools, highlighting benefits and critiques. While frameworks can be useful for synthesizing and communicating core concepts in a field, they often lack transparency in how they were developed and how they can be applied. Positioning frameworks within a theory of science can aid in knowing the purpose and value of framework use. This article provides a meta-framework for visualizing and engaging the four mediating processes for framework development and application: (1) empirical generalization, (2) theoretical fitting, (3) application, and (4) hypothesizing. Guiding points for scholars and policymakers using or developing frameworks in their research are provided in closing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Reflections on Methodological Issues

Looking Back

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The development of ‘frameworks’ is at present probably the most common strategy in the field of natural resources management to achieve integration and interdisciplinarity. Mollinga , 2008

…it is not clear what the role of a scientific framework should be, and relatedly, what makes for a successful scientific framework. Ban and Cox, 2017

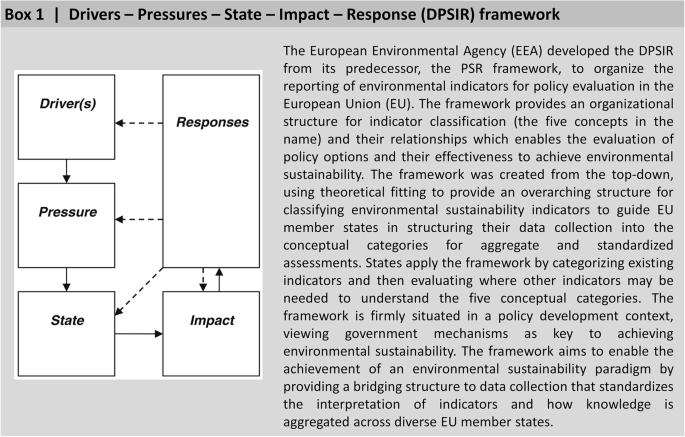

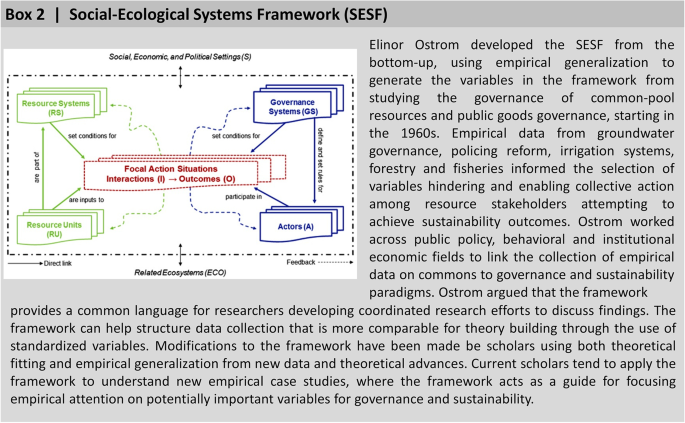

Frameworks are important research tools across nearly all fields of science. They are critically important for structuring empirical inquiry and theoretical development in the environmental social sciences, governance research and practice, the sustainability sciences and fields of social-ecological systems research in tangent with the associated disciplines of those fields (Binder et al. 2013 ; Pulver et al. 2018 ; Colding and Barthel 2019 ). Many well-established frameworks are regularly applied to collect new data or to structure entire research programs such as the Ecosystem Services (ES) framework (Potschin-Young et al. 2018 ), the Social-Ecological Systems Framework (SESF) (McGinnis and Ostrom 2014a ), Earth Systems Governance (ESG) (Biermann et al. 2010 ), the Driver-Impact-Pressure-State-Response (DIPSR) framework, and the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) framework. Frameworks are also put forth by major scientific organizing bodies to steer scientific and policy agendas at regional and global levels such as the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) (Díaz et al. 2015 ) and the Global Sustainable Development Report’s transformational levers and fields (UN 2019 ).

Despite the countless frameworks, it is not always clear how a framework can be developed or applied (Ban and Cox 2017 ; Partelow 2018 ; Nagel and Partelow 2022 ). Development may occur through empirically backed synthesis or by scholars based on their own knowledge, values, or interests. These diverse development pathways do, however, result in common trends. The structure of most frameworks is the identification of a set of concepts and their general relationships — often in the form box-and-arrow diagrams — that are loosely defined or unspecified. This hallmark has both benefits and challenges. On one hand, this is arguably the purpose of frameworks, to structure the basic ideas of theory or conceptual thinking, and if they were more detailed they would be models. On the other hand, there is often a “black box” nature to frameworks. It is often unclear why some sets of concepts and relationships are chosen for integration into frameworks, and others not. As argued below, these choices are often the result of the positionality of the framework’s creators. Publications of frameworks, furthermore, often lack descriptions of their value and potential uses compared to other frameworks or analytical tools that exist in the field.

Now shifting focus to how frameworks are applied. Some frameworks provide measureable indicators as the key variables in the framework, but many only suggest general concepts. This creates the need to link concepts and their relationships to data through other more tangible indicators. Methods to measure such indicators will also be needed in new empirical studies. These methodological and study design steps necessary to associate data to framework concepts is often referred to as “operationalizing” a framework. However, without guidance on how to do this, scholars are often left with developing their own strategies, which can lead to heterogeneous and idiosyncratic methods and data. These challenges can be referred to as methodological gaps (Partelow 2018 ), where the details of how to move from concept to indicator to measurement to data transformation, are not always detailed in a way that welcomes replicability or learning. This is not necessarily a problem if the purpose of a framework is to only guide the analysis of individual cases or synthesis activities in isolation, for example to inform local management, but it hinders meta-analyses, cross-case learning and data interpretability for others.

In this article, a brief overview of framework definitions and current synthesis literature are reviewed in the “ What is a framework? ” section. This is coupled with the argument that frameworks often lack clarity in their development and application because their positioning within a theory of science is unclear. In the “ Mechanisms of framework development and use: a meta-framework ” section, a meta-framework is proposed to assist in clarifying the four major levers with which frameworks are developed and applied: (1) empirical generalization, (2) theoretical fitting, (3) hypothesizing, and (4) application. The meta-framework aims to position individual frameworks into a theory of science, which can enable scholars to take a conceptual “step back” in order to view how their engagement with a framework contributes to their broader scientific goal and field. Two case studies of different frameworks are provided to explore how the meta-framework can aid in comparing them. This is followed by a discussion of what makes a good framework, along with explicit guiding points for the use of frameworks in research and policy practice.

What is a framework?

The definition and purpose of a framework is likely to vary across disciplines and thematic fields (Cox et al. 2016 ). There is no universal definition of a framework, but it is useful to provide a brief overview of different definitions for orientation. The Cambridge Dictionary states that frameworks are “a supporting structure around which something can be built; a system of rules, ideas, or beliefs that is used to plan or decide something.” Schlager ( 2007 , 293) states that “frameworks provide a foundation for inquiry,” and Cumming ( 2014 , 5) adds that this “does not necessarily depend on deductive logic to connect different ideas.” Importantly, Binder et al., ( 2013 , 2) note that “a framework provides a set of assumptions, concepts, values and practices,” emphasizing the normative or inherently subjective logic to framework development. A core theme being plurality and connectivity. Similarly, McGinnis and Ostrom ( 2014a , 1) define frameworks as “the basic vocabulary of concepts and terms that may be used to construct the kinds of causal explanations expected of a theory. Frameworks organize diagnostic, descriptive, and prescriptive inquiry.” In a review comparing ten commonly used frameworks in social-ecological systems (SES) research, Binder et al., ( 2013 , 1) state that frameworks are useful for developing “a common language, to structure research on SES, and to provide guidance toward a more sustainable development of SES.” In a similar review, Pulver et al., ( 2018 , 1) suggest that frameworks “assist scholars and practitioners to analyze the complex, nonlinear interdependencies that characterize interactions between biophysical and social arenas and to navigate the new epistemological, ontological, analytical, and practical horizons of integrating knowledge for sustainability solutions.” It is important to recognize that the above claims often suggest the dualistic or bridging positions held by frameworks, in both theory building and for guiding empirical observations. However, there is relatively little discussion in the above literature on how frameworks act as bridging tools within a theory of science or how frameworks add value as positioning tools in a field.

Every framework has a position, meaning it is located within a specific context of a scientific field. As positioning tools, frameworks seem to “populate the scientist’s world with a set of conceptual objects and (non-causal) relationships among them,” shaping (and sometimes limiting) the way we think about problems and potential solutions (Cox et al. 2016 , 47). Thus, using a specific framework helps in part to position the work of a researcher in a field and its related concepts, theories and paradigms.