Nursing: How to Write a Literature Review

- Traditional or Narrative Literature Review

Getting started

1. start with your research question, 2. search the literature, 3. read & evaluate, 4. finalize results, 5. write & revise, brainfuse online tutoring and writing review.

- RESEARCH HELP

The best way to approach your literature review is to break it down into steps. Remember, research is an iterative process, not a linear one. You will revisit steps and revise along the way. Get started with the handout, information, and tips from various university Writing Centers below that provides an excellent overview. Then move on to the specific steps recommended on this page.

- UNC- Chapel Hill Writing Center Literature Review Handout, from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- University of Wisconsin-Madison Writing Center Learn how to write a review of literature, from the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

- University of Toronto-- Writing Advice The Literature Review: A few tips on conducting it, from the University of Toronto.

- Begin with a topic.

- Understand the topic.

- Familiarize yourself with the terminology. Note what words are being used and keep track of these for use as database search keywords.

- See what research has been done on this topic before you commit to the topic. Review articles can be helpful to understand what research has been done .

- Develop your research question. (see handout below)

- How comprehensive should it be?

- Is it for a course assignment or a dissertation?

- How many years should it cover?

- Developing a good nursing research question Handout. Reviews PICO method and provides search tips.

Your next step is to construct a search strategy and then locate & retrieve articles.

- There are often 2-4 key concepts in a research question.

- Search for primary sources (original research articles.)

- These are based on the key concepts in your research question.

- Remember to consider synonyms and related terms.

- Which databases to search?

- What limiters should be applied (peer-reviewed, publication date, geographic location, etc.)?

Review articles (secondary sources)

Use to identify literature on your topic, the way you would use a bibliography. Then locate and retrieve the original studies discussed in the review article. Review articles are considered secondary sources.

- Once you have some relevant articles, review reference lists to see if there are any useful articles.

- Which articles were written later and have cited some of your useful articles? Are these, in turn, articles that will be useful to you?

- Keep track of what terms you used and what databases you searched.

- Use database tools such as save search history in EBSCO to help.

- Keep track of the citations for the articles you will be using in your literature review.

- Use RefWorks or another method of tracking this information.

- Database Search Strategy Worksheet Handout. How to construct a search.

- TUTORIAL: How to do a search based on your research question This is a self-paced, interactive tutorial that reviews how to construct and perform a database search in CINAHL.

The next step is to read, review, and understand the articles.

- Start by reviewing abstracts.

- Make sure you are selecting primary sources (original research articles).

- Note any keywords authors report using when searching for prior studies.

- You will need to evaluate and critique them and write a synthesis related to your research question.

- Consider using a matrix to organize and compare and contrast the articles .

- Which authors are conducting research in this area? Search by author.

- Are there certain authors’ whose work is cited in many of your articles? Did they write an early, seminal article that is often cited?

- Searching is a cyclical process where you will run searches, review results, modify searches, run again, review again, etc.

- Critique articles. Keep or exclude based on whether they are relevant to your research question.

- When you have done a thorough search using several databases plus Google Scholar, using appropriate keywords or subject terms, plus author’s names, and you begin to find the same articles over and over.

- Remember to consider the scope of your project and the length of your paper. A dissertation will have a more exhaustive literature review than an 8 page paper, for example.

- What are common findings among each group or where do they disagree?

- Identify common themes. Identify controversial or problematic areas in the research.

- Use your matrix to organize this.

- Once you have read and re-read your articles and organized your findings, you are ready to begin the process of writing the literature review.

2. Synthesize. (see handout below)

- Include a synthesis of the articles you have chosen for your literature review.

- A literature review is NOT a list or a summary of what has been written on a particular topic.

- It analyzes the articles in terms of how they relate to your research question.

- While reading, look for similarities and differences (compare and contrast) among the articles. You will create your synthesis from this.

- Synthesis Examples Handout. Sample excerpts that illustrate synthesis.

Regis Online students have access to Brainfuse. Brainfuse is an online tutoring service available through a link in Moodle. Meet with a tutor in a live session or submit your paper for review.

- Brainfuse Tutoring and Writing Assistance for Regis Online Students by Tricia Reinhart Last Updated Oct 26, 2023 81 views this year

- << Previous: Traditional or Narrative Literature Review

- Next: eBooks >>

- Last Updated: Feb 21, 2024 12:05 PM

- URL: https://libguides.regiscollege.edu/nursing_litreview

Nursing: Literature Review

- Required Texts

- Writing Assistance and Organizing & Citing References

- NCLEX Resources

- Literature Review

- MSN Students

- Physical Examination

- Drug Information

- Professional Organizations

- Mobile Apps

- Evidence-based Medicine

- Certifications

- Recommended Nursing Textbooks

- DNP Students

- Conducting Research

- Scoping Reviews

- Systematic Reviews

- Distance Education Students

- Ordering from your Home Library

Good Place to Start: Citation Databases

Interdisciplinary Citation Databases:

A good place to start your research is to search a research citation database to view the scope of literature available on your topic.

TIP #1: SEED ARTICLE Begin your research with a "seed article" - an article that strongly supports your research topic. Then use a citation database to follow the studies published by finding articles which have cited that article, either because they support it or because they disagree with it.

TIP #2: SNOWBALLING Snowballing is the process where researchers will begin with a select number of articles they have identified relevant/strongly supports their topic and then search each articles' references reviewing the studies cited to determine if they are relevant to your research.

BONUS POINTS: This process also helps identify key highly cited authors within a topic to help establish the "experts" in the field.

Begin by constructing a focused research question to help you then convert it into an effective search strategy.

- Identify keywords or synonyms

- Type of study/resources

- Which database(s) to search

- Asking a Good Question (PICO)

- PICO - AHRQ

- PICO - Worksheet

- What Is a PICOT Question?

Seminal Works: Search Key Indexing/Citation Databases

- Google Scholar

- Web of Science

TIP – How to Locate Seminal Works

- DO NOT: Limit by date range or you might overlook the seminal works

- DO: Look at highly cited references (Seminal articles are frequently referred to “cited” in the research)

- DO: Search citation databases like Scopus, Web of Science and Google Scholar

Web Resources

What is a literature review?

A literature review is a comprehensive and up-to-date overview of published information on a subject area. Conducting a literature review demands a careful examination of a body of literature that has been published that helps answer your research question (See PICO). Literature reviewed includes scholarly journals, scholarly books, authoritative databases, primary sources and grey literature.

A literature review attempts to answer the following:

- What is known about the subject?

- What is the chronology of knowledge about my subject?

- Are there any gaps in the literature?

- Is there a consensus/debate on issues?

- Create a clear research question/statement

- Define the scope of the review include limitations (i.e. gender, age, location, nationality...)

- Search existing literature including classic works on your topic and grey literature

- Evaluate results and the evidence (Avoid discounting information that contradicts your research)

- Track and organize references

- How to conduct an effective literature search.

- Social Work Literature Review Guidelines (OWL Purdue Online Writing Lab)

What is PICO?

The PICO model can help you formulate a good clinical question. Sometimes it's referred to as PICO-T, containing an optional 5th factor.

Search Example

- << Previous: NCLEX Resources

- Next: MSN Students >>

- Last Updated: Mar 13, 2024 10:57 AM

- URL: https://guides.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/Nursing

- Himmelfarb Intranet

- Privacy Notice

- Terms of Use

- GW is committed to digital accessibility. If you experience a barrier that affects your ability to access content on this page, let us know via the Accessibility Feedback Form .

- Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library

- 2300 Eye St., NW, Washington, DC 20037

- Phone: (202) 994-2850

- [email protected]

- https://himmelfarb.gwu.edu

University Library

- Research Guides

- Literature Reviews

- Evidence-Based Practice

- Books & Media

What is a Literature Review?

Key questions for a literature review, examples of literature reviews, useful links, evidence matrix for literature reviews.

- Annotated Bibliographies

The Scholarly Conversation

A literature review provides an overview of previous research on a topic that critically evaluates, classifies, and compares what has already been published on a particular topic. It allows the author to synthesize and place into context the research and scholarly literature relevant to the topic. It helps map the different approaches to a given question and reveals patterns. It forms the foundation for the author’s subsequent research and justifies the significance of the new investigation.

A literature review can be a short introductory section of a research article or a report or policy paper that focuses on recent research. Or, in the case of dissertations, theses, and review articles, it can be an extensive review of all relevant research.

- The format is usually a bibliographic essay; sources are briefly cited within the body of the essay, with full bibliographic citations at the end.

- The introduction should define the topic and set the context for the literature review. It will include the author's perspective or point of view on the topic, how they have defined the scope of the topic (including what's not included), and how the review will be organized. It can point out overall trends, conflicts in methodology or conclusions, and gaps in the research.

- In the body of the review, the author should organize the research into major topics and subtopics. These groupings may be by subject, (e.g., globalization of clothing manufacturing), type of research (e.g., case studies), methodology (e.g., qualitative), genre, chronology, or other common characteristics. Within these groups, the author can then discuss the merits of each article and analyze and compare the importance of each article to similar ones.

- The conclusion will summarize the main findings, make clear how this review of the literature supports (or not) the research to follow, and may point the direction for further research.

- The list of references will include full citations for all of the items mentioned in the literature review.

A literature review should try to answer questions such as

- Who are the key researchers on this topic?

- What has been the focus of the research efforts so far and what is the current status?

- How have certain studies built on prior studies? Where are the connections? Are there new interpretations of the research?

- Have there been any controversies or debate about the research? Is there consensus? Are there any contradictions?

- Which areas have been identified as needing further research? Have any pathways been suggested?

- How will your topic uniquely contribute to this body of knowledge?

- Which methodologies have researchers used and which appear to be the most productive?

- What sources of information or data were identified that might be useful to you?

- How does your particular topic fit into the larger context of what has already been done?

- How has the research that has already been done help frame your current investigation ?

Example of a literature review at the beginning of an article: Forbes, C. C., Blanchard, C. M., Mummery, W. K., & Courneya, K. S. (2015, March). Prevalence and correlates of strength exercise among breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer survivors . Oncology Nursing Forum, 42(2), 118+. Retrieved from http://go.galegroup.com.sonoma.idm.oclc.org/ps/i.do?p=HRCA&sw=w&u=sonomacsu&v=2.1&it=r&id=GALE%7CA422059606&asid=27e45873fddc413ac1bebbc129f7649c Example of a comprehensive review of the literature: Wilson, J. L. (2016). An exploration of bullying behaviours in nursing: a review of the literature. British Journal Of Nursing , 25 (6), 303-306. For additional examples, see:

Galvan, J., Galvan, M., & ProQuest. (2017). Writing literature reviews: A guide for students of the social and behavioral sciences (Seventh ed.). [Electronic book]

Pan, M., & Lopez, M. (2008). Preparing literature reviews: Qualitative and quantitative approaches (3rd ed.). Glendale, CA: Pyrczak Pub. [ Q180.55.E9 P36 2008]

- Write a Literature Review (UCSC)

- Literature Reviews (Purdue)

- Literature Reviews: overview (UNC)

- Review of Literature (UW-Madison)

The Evidence Matrix can help you organize your research before writing your lit review. Use it to identify patterns and commonalities in the articles you have found--similar methodologies ? common theoretical frameworks ? It helps you make sure that all your major concepts covered. It also helps you see how your research fits into the context of the overall topic.

- Evidence Matrix Special thanks to Dr. Cindy Stearns, SSU Sociology Dept, for permission to use this Matrix as an example.

- << Previous: Misc

- Next: Annotated Bibliographies >>

- Last Updated: Jan 8, 2024 2:58 PM

- URL: https://libguides.sonoma.edu/nursing

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Doing a Literature Review in Nursing, Health and Social Care

- Michael Coughlan - Trinity College Dublin, Ireland

- Patricia Cronin - Trinity College Dublin, Ireland

- Description

A clear and practical guide to completing a literature review in nursing and healthcare studies.

Providing students with straightforward guidance on how to successfully carry out a literature review as part of a research project or dissertation, this book uses examples and activities to demonstrate how to complete each step correctly, from start to finish, and highlights how to avoid common mistakes.

The third edition includes:

- Expert advice on selecting and researching a topic

- A chapter outlining the different types of literature review

- Increased focus on Critical Appraisal Tools and how to use them effectively

- New real-world examples presenting best practice

- Instructions on writing up and presenting the final piece of work

Perfect for any nursing or healthcare student new to literature reviews and for anyone who needs a refresher in this important topic.

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

Praise for the previous edition:

'This book is an excellent resource for practitioners wishing to develop their knowledge and understanding of reviewing literature and the processes involved. It uses uncomplicated language to signpost the reader effortlessly through key aspects of research processes. Practitioners will find this an invaluable companion for navigating through evidence to identify quality literature applicable to health and social care practice.'

'Students often struggle with writing an effective literature review and this invaluable guide will help to allay their concerns. Key terms are clearly explained, and the inclusion of learning outcomes is a helpful feature for students and lecturers alike. The examples are also very helpful, particularly for less confident students. This is an accessible yet authoritative guide which I can thoroughly recommend.'

'A must have - this book provides useful information and guidance to students and professionals alike. It guides the reader through various research methods in a theoretical and pragmatic manner.'

' It's a very readable, concise, and accessible introduction to undertaking a literature review in the field of healthcare. The book’s layout has a logical format which really helped me to think methodically about my research question. An excellent reference for undergraduates who are about to undertake their first literature review.'

'This book is an essential resource for students. Clearly written and excellently structured, with helpful study tools throughout, it takes the reader step by step through the literature review process in an easy, informative and accessible manner. This text gives students the skills they need to successfully complete their own review.'

'The updating of the chapters will be exceptionally helpful given the rapid changes in online availability of resources and open-access literature.'

Excellent text for masters and doctoral level students

An excellent primer to help the level 7 students write their systemised review for the assignment.

This book provides a comprehensive overview of the practical process of literature review in healthcare. It contains all details required to conduct a review by students.

This is an excellent clear and concise book on undertaking literature reviews being particularly good at demystifying jargon. It is timely given the move to student dissertations being primarily literature reviews in the current Covid pandemic. However nearly all the examples are drawn from nursing and health making the text less useful for social care and social work. A little disappointing given the title. SW students are likely to gravitate to texts where their subject is more prominent for a primary text.

Accessible, informative, step to step guide

This is a really helpful, accessible text for students and academic staff alike.

A really good addition to the repertoire of skills and techniques for understanding the essential process of literature reviewing.

Preview this book

For instructors, select a purchasing option, related products.

Library Research Guides - University of Wisconsin Ebling Library

Uw-madison libraries research guides.

- Course Guides

- Subject Guides

- University of Wisconsin-Madison

- Research Guides

- Nursing Resources

- Conducting a Literature Review

Nursing Resources : Conducting a Literature Review

- Definitions of

- Professional Organizations

- Nursing Informatics

- Nursing Related Apps

- EBP Resources

- PICO-Clinical Question

- Types of PICO Question (D, T, P, E)

- Secondary & Guidelines

- Bedside--Point of Care

- Pre-processed Evidence

- Measurement Tools, Surveys, Scales

- Types of Studies

- Table of Evidence

- Qualitative vs Quantitative

- Types of Research within Qualitative and Quantitative

- Cohort vs Case studies

- Independent Variable VS Dependent Variable

- Sampling Methods and Statistics

- Systematic Reviews

- Review vs Systematic Review vs ETC...

- Standard, Guideline, Protocol, Policy

- Additional Guidelines Sources

- Peer Reviewed Articles

- Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis

- Writing a Research Paper or Poster

- Annotated Bibliographies

- Levels of Evidence (I-VII)

- Reliability

- Validity Threats

- Threats to Validity of Research Designs

- Nursing Theory

- Nursing Models

- PRISMA, RevMan, & GRADEPro

- ORCiD & NIH Submission System

- Understanding Predatory Journals

- Nursing Scope & Standards of Practice, 4th Ed

- Distance Ed & Scholarships

- Assess A Quantitative Study?

- Assess A Qualitative Study?

- Find Health Statistics?

- Choose A Citation Manager?

- Find Instruments, Measurements, and Tools

- Write a CV for a DNP or PhD?

- Find information about graduate programs?

- Learn more about Predatory Journals

- Get writing help?

- Choose a Citation Manager?

- Other questions you may have

- Search the Databases?

- Get Grad School information?

What is a Literature Review?

A literature review is an essay that surveys, summarizes, links together, and assesses research in a given field. It surveys the literature by reviewing a large body of work on a subject; it summarizes by noting the main conclusions and findings of the research; it links together works in the literature by showing how the information fits into the overall academic discussion and how the information relates to one another; it assesses the literature by noting areas of weakness, expansion, and contention. This is the essentials of literature review construction by discussing the major sectional elements, their purpose, how they are constructed, and how they all fit together.

All literature reviews have major sections:

- Introduction: that indicates the general state of the literature on a given topic;

- Methodology: an overview of how, where, and what subject terms used to conducted your search so it may be reproducable

- Findings: a summary of the major findings in that field;

- Discussion: a general progression from wider studies to smaller, more specifically-focused studies;

- Conclusion: for each major section that again notes the overall state of the research, albeit with a focus on the major synthesized conclusions, problems in the research, and even possible avenues of further research.

In Literature Reviews, it is Not Appropriate to:

- State your own opinions on the subject (unless you have evidence to support such claims).

- State what you think nurses should do (unless you have evidence to support such claims).

- Provide long descriptive accounts of your subject with no reference to research studies.

- Provide numerous definitions, signs/symptoms, treatment and complications of a particular illness without focusing on research studies to provide evidence and the primary purpose of the literature review.

- Discuss research studies in isolation from each other.

Remember, a literature review is not a book report. A literature review is focus, succinct, organized, and is free of personal beliefs or unsubstantiated tidbits.

- Types of Literature Reviews A detailed explanation of the different types of reviews and required citation retrieval numbers

Outline of a Literture Review

- << Previous: Peer Reviewed Articles

- Next: Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis >>

- Last Updated: Nov 30, 2023 2:31 PM

- URL: https://researchguides.library.wisc.edu/nursing

This website is intended for healthcare professionals

- { $refs.search.focus(); })" aria-controls="searchpanel" :aria-expanded="open" class="hidden lg:inline-flex justify-end text-gray-800 hover:text-primary py-2 px-4 lg:px-0 items-center text-base font-medium"> Search

Search menu

Bashir Y, Conlon KC. Step by step guide to do a systematic review and meta-analysis for medical professionals. Ir J Med Sci. 2018; 187:(2)447-452 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-017-1663-3

Bettany-Saltikov J. How to do a systematic literature review in nursing: a step-by-step guide.Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2012

Bowers D, House A, Owens D. Getting started in health research.Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011

Hierarchies of evidence. 2016. http://cjblunt.com/hierarchies-evidence (accessed 23 July 2019)

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2008; 3:(2)37-41 https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Developing a framework for critiquing health research. 2005. https://tinyurl.com/y3nulqms (accessed 22 July 2019)

Cognetti G, Grossi L, Lucon A, Solimini R. Information retrieval for the Cochrane systematic reviews: the case of breast cancer surgery. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2015; 51:(1)34-39 https://doi.org/10.4415/ANN_15_01_07

Dixon-Woods M, Cavers D, Agarwal S Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006; 6:(1) https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-6-35

Guyatt GH, Sackett DL, Sinclair JC Users' guides to the medical literature IX. A method for grading health care recommendations. JAMA. 1995; 274:(22)1800-1804 https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1995.03530220066035

Hanley T, Cutts LA. What is a systematic review? Counselling Psychology Review. 2013; 28:(4)3-6

Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0. 2011. https://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org (accessed 23 July 2019)

Jahan N, Naveed S, Zeshan M, Tahir MA. How to conduct a systematic review: a narrative literature review. Cureus. 2016; 8:(11) https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.864

Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1997; 33:(1)159-174

Methley AM, Campbell S, Chew-Graham C, McNally R, Cheraghi-Sohi S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: a comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014; 14:(1) https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-014-0579-0

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009; 6:(7) https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Mueller J, Jay C, Harper S, Davies A, Vega J, Todd C. Web use for symptom appraisal of physical health conditions: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2017; 19:(6) https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.6755

Murad MH, Asi N, Alsawas M, Alahdab F. New evidence pyramid. Evid Based Med. 2016; 21:(4)125-127 https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmed-2016-110401

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Methods for the development of NICE public health guidance. 2012. http://nice.org.uk/process/pmg4 (accessed 22 July 2019)

Sambunjak D, Franic M. Steps in the undertaking of a systematic review in orthopaedic surgery. Int Orthop. 2012; 36:(3)477-484 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-011-1460-y

Siddaway AP, Wood AM, Hedges LV. How to do a systematic review: a best practice guide for conducting and reporting narrative reviews, meta-analyses, and meta-syntheses. Annu Rev Psychol. 2019; 70:747-770 https://doi.org/0.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102803

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008; 8:(1) https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

Wallace J, Nwosu B, Clarke M. Barriers to the uptake of evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses: a systematic review of decision makers' perceptions. BMJ Open. 2012; 2:(5) https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001220

Carrying out systematic literature reviews: an introduction

Alan Davies

Lecturer in Health Data Science, School of Health Sciences, University of Manchester, Manchester

View articles · Email Alan

Systematic reviews provide a synthesis of evidence for a specific topic of interest, summarising the results of multiple studies to aid in clinical decisions and resource allocation. They remain among the best forms of evidence, and reduce the bias inherent in other methods. A solid understanding of the systematic review process can be of benefit to nurses that carry out such reviews, and for those who make decisions based on them. An overview of the main steps involved in carrying out a systematic review is presented, including some of the common tools and frameworks utilised in this area. This should provide a good starting point for those that are considering embarking on such work, and to aid readers of such reviews in their understanding of the main review components, in order to appraise the quality of a review that may be used to inform subsequent clinical decision making.

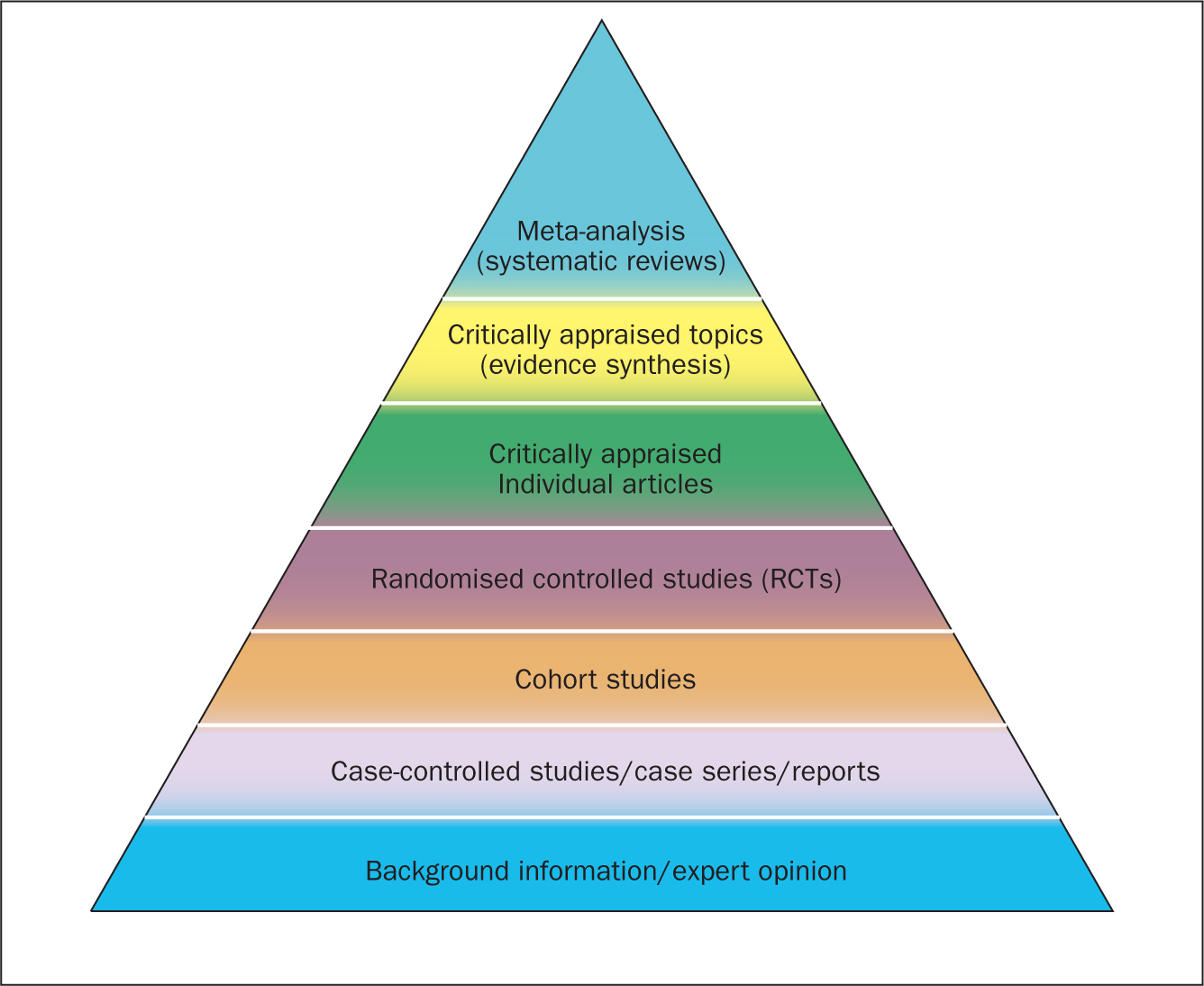

Since their inception in the late 1970s, systematic reviews have gained influence in the health professions ( Hanley and Cutts, 2013 ). Systematic reviews and meta-analyses are considered to be the most credible and authoritative sources of evidence available ( Cognetti et al, 2015 ) and are regarded as the pinnacle of evidence in the various ‘hierarchies of evidence’. Reviews published in the Cochrane Library ( https://www.cochranelibrary.com) are widely considered to be the ‘gold’ standard. Since Guyatt et al (1995) presented a users' guide to medical literature for the Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group, various hierarchies of evidence have been proposed. Figure 1 illustrates an example.

Systematic reviews can be qualitative or quantitative. One of the criticisms levelled at hierarchies such as these is that qualitative research is often positioned towards or even is at the bottom of the pyramid, thus implying that it is of little evidential value. This may be because of traditional issues concerning the quality of some qualitative work, although it is now widely recognised that both quantitative and qualitative research methodologies have a valuable part to play in answering research questions, which is reflected by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) information concerning methods for developing public health guidance. The NICE (2012) guidance highlights how both qualitative and quantitative study designs can be used to answer different research questions. In a revised version of the hierarchy-of-evidence pyramid, the systematic review is considered as the lens through which the evidence is viewed, rather than being at the top of the pyramid ( Murad et al, 2016 ).

Both quantitative and qualitative research methodologies are sometimes combined in a single review. According to the Cochrane review handbook ( Higgins and Green, 2011 ), regardless of type, reviews should contain certain features, including:

- Clearly stated objectives

- Predefined eligibility criteria for inclusion or exclusion of studies in the review

- A reproducible and clearly stated methodology

- Validity assessment of included studies (eg quality, risk, bias etc).

The main stages of carrying out a systematic review are summarised in Box 1 .

Formulating the research question

Before undertaking a systemic review, a research question should first be formulated ( Bashir and Conlon, 2018 ). There are a number of tools/frameworks ( Table 1 ) to support this process, including the PICO/PICOS, PEO and SPIDER criteria ( Bowers et al, 2011 ). These frameworks are designed to help break down the question into relevant subcomponents and map them to concepts, in order to derive a formalised search criterion ( Methley et al, 2014 ). This stage is essential for finding literature relevant to the question ( Jahan et al, 2016 ).

It is advisable to first check that the review you plan to carry out has not already been undertaken. You can optionally register your review with an international register of prospective reviews called PROSPERO, although this is not essential for publication. This is done to help you and others to locate work and see what reviews have already been carried out in the same area. It also prevents needless duplication and instead encourages building on existing work ( Bashir and Conlon, 2018 ).

A study ( Methley et al, 2014 ) that compared PICO, PICOS and SPIDER in relation to sensitivity and specificity recommended that the PICO tool be used for a comprehensive search and the PICOS tool when time/resources are limited.

The use of the SPIDER tool was not recommended due to the risk of missing relevant papers. It was, however, found to increase specificity.

These tools/frameworks can help those carrying out reviews to structure research questions and define key concepts in order to efficiently identify relevant literature and summarise the main objective of the review ( Jahan et al, 2016 ). A possible research question could be: Is paracetamol of benefit to people who have just had an operation? The following examples highlight how using a framework may help to refine the question:

- What form of paracetamol? (eg, oral/intravenous/suppository)

- Is the dosage important?

- What is the patient population? (eg, children, adults, Europeans)

- What type of operation? (eg, tonsillectomy, appendectomy)

- What does benefit mean? (eg, reduce post-operative pyrexia, analgesia).

An example of a more refined research question could be: Is oral paracetamol effective in reducing pain following cardiac surgery for adult patients? A number of concepts for each element will need to be specified. There will also be a number of synonyms for these concepts ( Table 2 ).

Table 2 shows an example of concepts used to define a search strategy using the PICO statement. It is easy to see even with this dummy example that there are many concepts that require mapping and much thought required to capture ‘good’ search criteria. Consideration should be given to the various terms to describe the heart, such as cardiac, cardiothoracic, myocardial, myocardium, etc, and the different names used for drugs, such as the equivalent name used for paracetamol in other countries and regions, as well as the various brand names. Defining good search criteria is an important skill that requires a lot of practice. A high-quality review gives details of the search criteria that enables the reader to understand how the authors came up with the criteria. A specific, well-defined search criterion also aids in the reproducibility of a review.

Search criteria

Before the search for papers and other documents can begin it is important to explicitly define the eligibility criteria to determine whether a source is relevant to the review ( Hanley and Cutts, 2013 ). There are a number of database sources that are searched for medical/health literature including those shown in Table 3 .

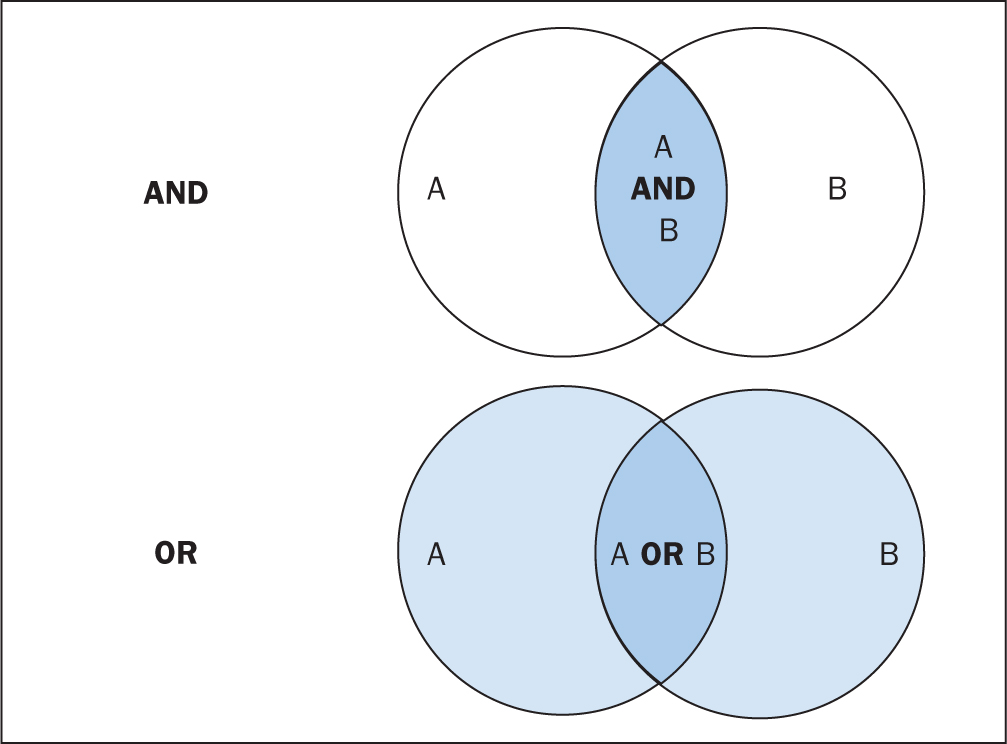

The various databases can be searched using common Boolean operators to combine or exclude search terms (ie AND, OR, NOT) ( Figure 2 ).

Although most literature databases use similar operators, it is necessary to view the individual database guides, because there are key differences between some of them. Table 4 details some of the common operators and wildcards used in the databases for searching. When developing a search criteria, it is a good idea to check concepts against synonyms, as well as abbreviations, acronyms and plural and singular variations ( Cognetti et al, 2015 ). Reading some key papers in the area and paying attention to the key words they use and other terms used in the abstract, and looking through the reference lists/bibliographies of papers, can also help to ensure that you incorporate relevant terms. Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) that are used by the National Library of Medicine (NLM) ( https://www.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/meshhome.html) to provide hierarchical biomedical index terms for NLM databases (Medline and PubMed) should also be explored and included in relevant search strategies.

Searching the ‘grey literature’ is also an important factor in reducing publication bias. It is often the case that only studies with positive results and statistical significance are published. This creates a certain bias inherent in the published literature. This bias can, to some degree, be mitigated by the inclusion of results from the so-called grey literature, including unpublished work, abstracts, conference proceedings and PhD theses ( Higgins and Green, 2011 ; Bettany-Saltikov, 2012 ; Cognetti et al, 2015 ). Biases in a systematic review can lead to overestimating or underestimating the results ( Jahan et al, 2016 ).

An example search strategy from a published review looking at web use for the appraisal of physical health conditions can be seen in Box 2 . High-quality reviews usually detail which databases were searched and the number of items retrieved from each.

A balance between high recall and high precision is often required in order to produce the best results. An oversensitive search, or one prone to including too much noise, can mean missing important studies or producing too many search results ( Cognetti et al, 2015 ). Following a search, the exported citations can be added to citation management software (such as Mendeley or Endnote) and duplicates removed.

Title and abstract screening

Initial screening begins with the title and abstracts of articles being read and included or excluded from the review based on their relevance. This is usually carried out by at least two researchers to reduce bias ( Bashir and Conlon, 2018 ). After screening any discrepancies in agreement should be resolved by discussion, or by an additional researcher casting the deciding vote ( Bashir and Conlon, 2018 ). Statistics for inter-rater reliability exist and can be reported, such as percentage of agreement or Cohen's kappa ( Box 3 ) for two reviewers and Fleiss' kappa for more than two reviewers. Agreement can depend on the background and knowledge of the researchers and the clarity of the inclusion and exclusion criteria. This highlights the importance of providing clear, well-defined criteria for inclusion that are easy for other researchers to follow.

Full-text review

Following title and abstract screening, the remaining articles/sources are screened in the same way, but this time the full texts are read in their entirety and included or excluded based on their relevance. Reasons for exclusion are usually recorded and reported. Extraction of the specific details of the studies can begin once the final set of papers is determined.

Data extraction

At this stage, the full-text papers are read and compared against the inclusion criteria of the review. Data extraction sheets are forms that are created to extract specific data about a study (12 Jahan et al, 2016 ) and ensure that data are extracted in a uniform and structured manner. Extraction sheets can differ between quantitative and qualitative reviews. For quantitative reviews they normally include details of the study's population, design, sample size, intervention, comparisons and outcomes ( Bettany-Saltikov, 2012 ; Mueller et al, 2017 ).

Quality appraisal

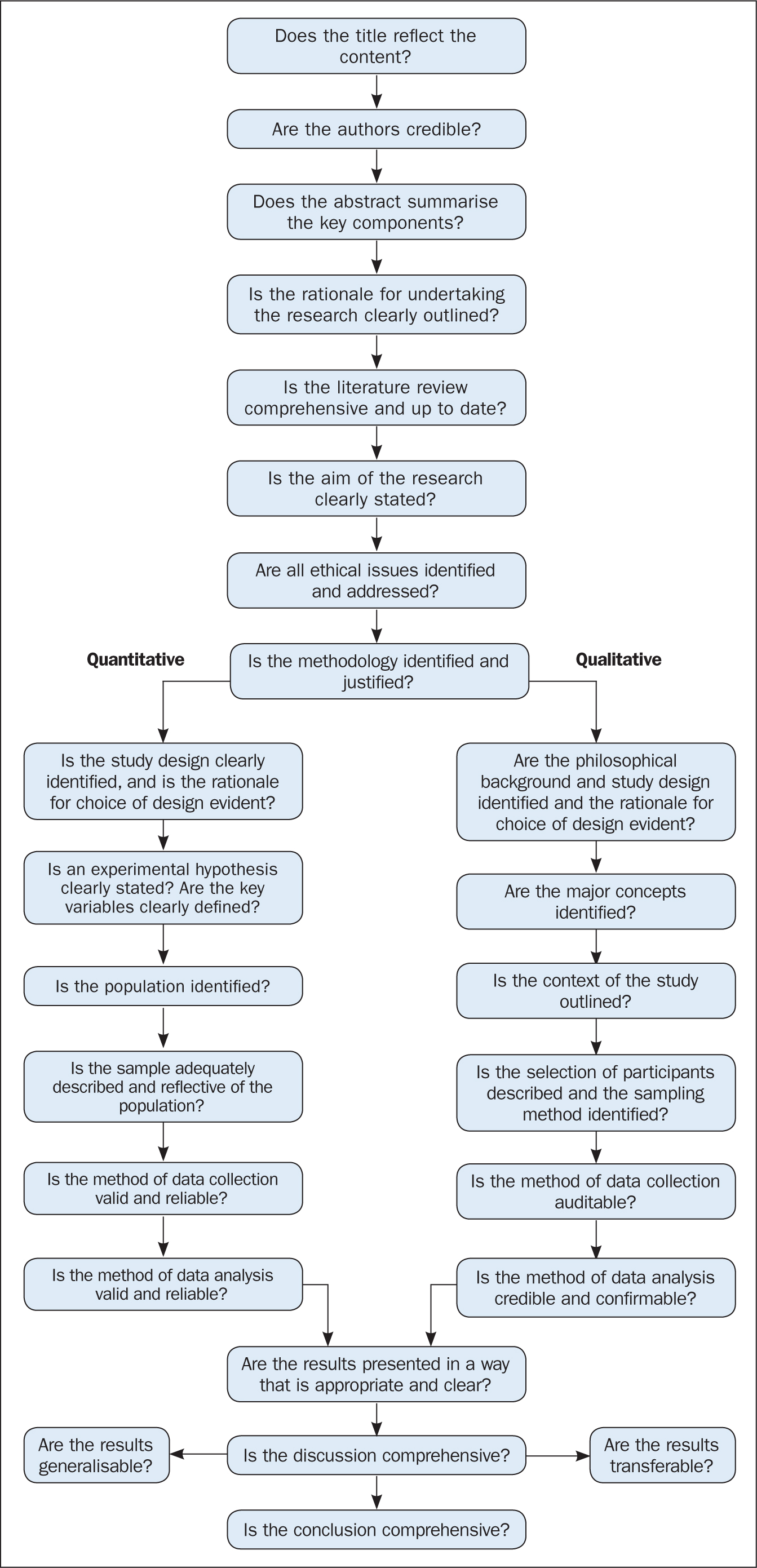

The quality of the studies used in the review should also be appraised. Caldwell et al (2005) discussed the need for a health research evaluation framework that could be used to evaluate both qualitative and quantitative work. The framework produced uses features common to both research methodologies, as well as those that differ ( Caldwell et al, 2005 ; Dixon-Woods et al, 2006 ). Figure 3 details the research critique framework. Other quality appraisal methods do exist, such as those presented in Box 4 . Quality appraisal can also be used to weight the evidence from studies. For example, more emphasis can be placed on the results of large randomised controlled trials (RCT) than one with a small sample size. The quality of a review can also be used as a factor for exclusion and can be specified in inclusion/exclusion criteria. Quality appraisal is an important step that needs to be undertaken before conclusions about the body of evidence can be made ( Sambunjak and Franic, 2012 ). It is also important to note that there is a difference between the quality of the research carried out in the studies and the quality of how those studies were reported ( Sambunjak and Franic, 2012 ).

The quality appraisal is different for qualitative and quantitative studies. With quantitative studies this usually focuses on their internal and external validity, such as how well the study has been designed and analysed, and the generalisability of its findings. Qualitative work, on the other hand, is often evaluated in terms of trustworthiness and authenticity, as well as how transferable the findings may be ( Bettany-Saltikov, 2012 ; Bashir and Conlon, 2018 ; Siddaway et al, 2019 ).

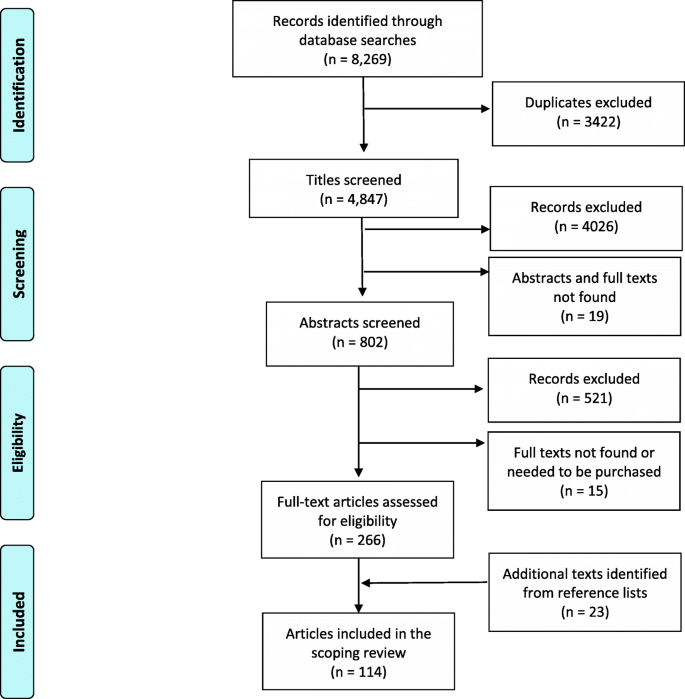

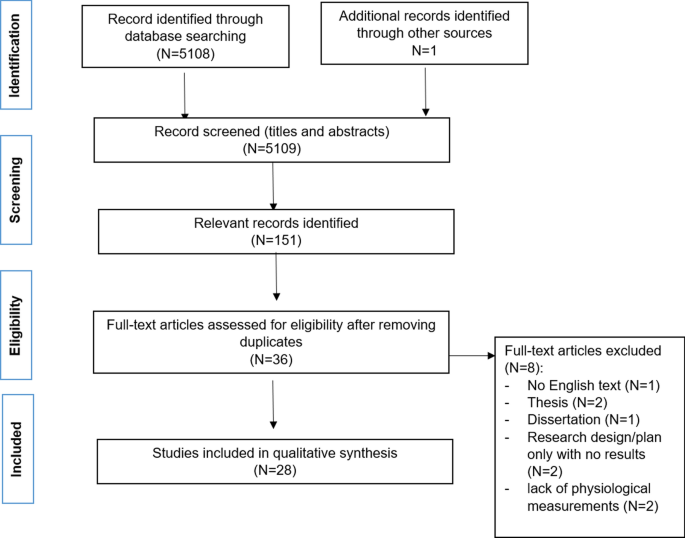

Reporting a review (the PRISMA statement)

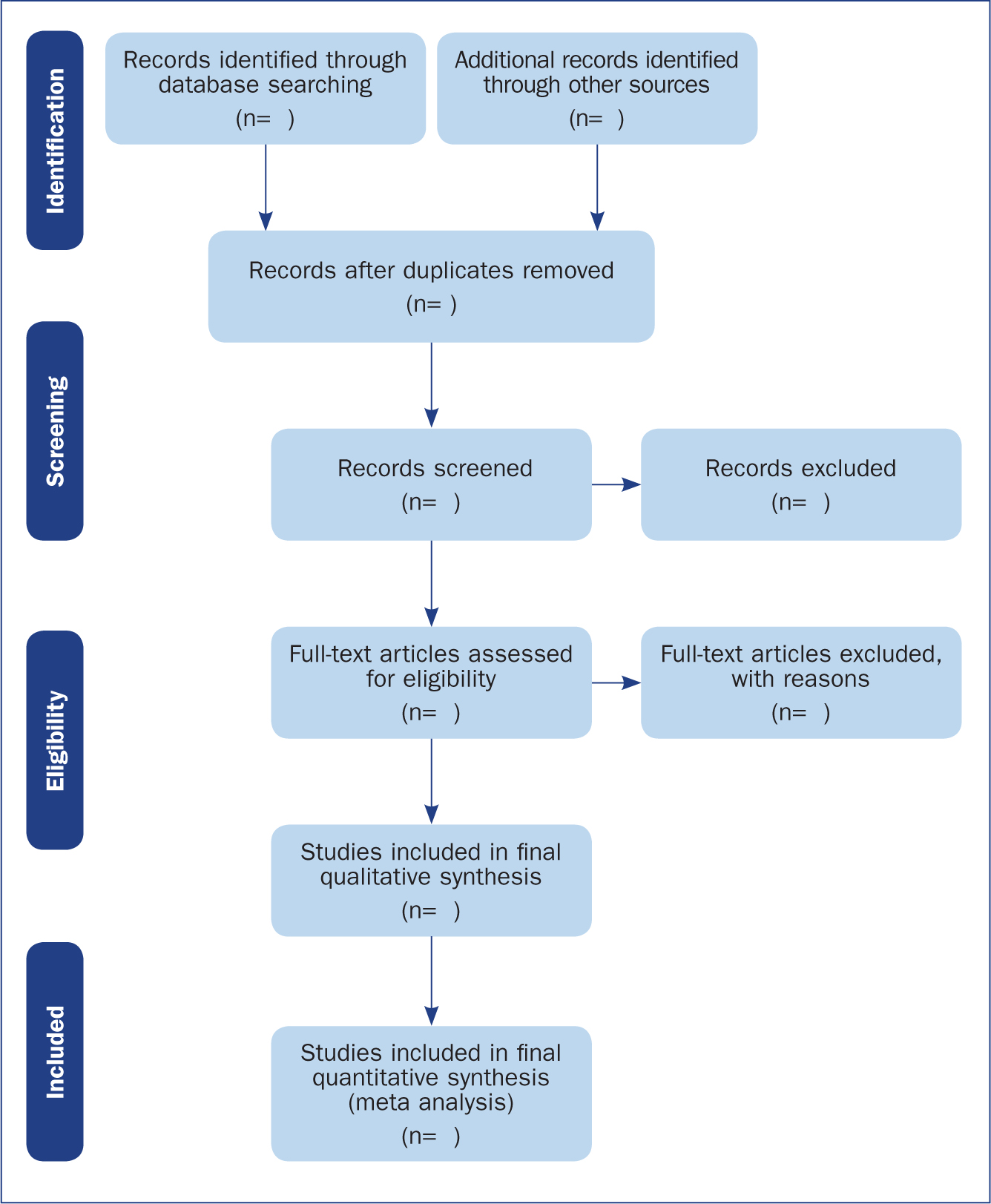

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) provides a reporting structure for systematic reviews/meta-analysis, and consists of a checklist and diagram ( Figure 4 ). The stages of identifying potential papers/sources, screening by title and abstract, determining eligibility and final inclusion are detailed with the number of articles included/excluded at each stage. PRISMA diagrams are often included in systematic reviews to detail the number of papers included at each of the four main stages (identification, screening, eligibility and inclusion) of the review.

Data synthesis

The combined results of the screened studies can be analysed qualitatively by grouping them together under themes and subthemes, often referred to as meta-synthesis or meta-ethnography ( Siddaway et al, 2019 ). Sometimes this is not done and a summary of the literature found is presented instead. When the findings are synthesised, they are usually grouped into themes that were derived by noting commonality among the studies included. Inductive (bottom-up) thematic analysis is frequently used for such purposes and works by identifying themes (essentially repeating patterns) in the data, and can include a set of higher-level and related subthemes (Braun and Clarke, 2012). Thomas and Harden (2008) provide examples of the use of thematic synthesis in systematic reviews, and there is an excellent introduction to thematic analysis by Braun and Clarke (2012).

The results of the review should contain details on the search strategy used (including search terms), the databases searched (and the number of items retrieved), summaries of the studies included and an overall synthesis of the results ( Bettany-Saltikov, 2012 ). Finally, conclusions should be made about the results and the limitations of the studies included ( Jahan et al, 2016 ). Another method for synthesising data in a systematic review is a meta-analysis.

Limitations of systematic reviews

Apart from the many advantages and benefits to carrying out systematic reviews highlighted throughout this article, there remain a number of disadvantages. These include the fact that not all stages of the review process are followed rigorously or even at all in some cases. This can lead to poor quality reviews that are difficult or impossible to replicate. There also exist some barriers to the use of evidence produced by reviews, including ( Wallace et al, 2012 ):

- Lack of awareness and familiarity with reviews

- Lack of access

- Lack of direct usefulness/applicability.

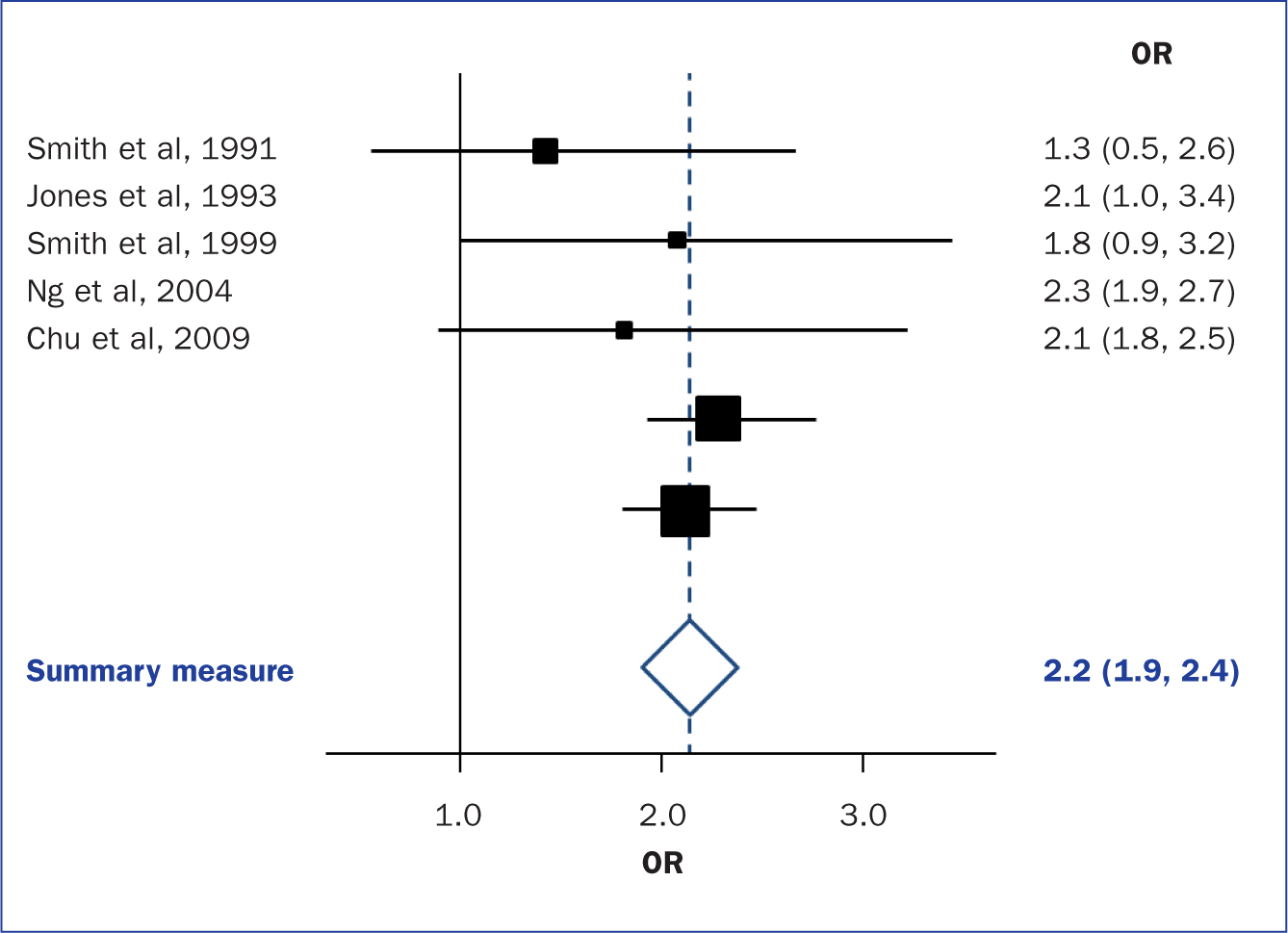

Meta-analysis

When the methods used and the analysis are similar or the same, such as in some RCTs, the results can be synthesised using a statistical approach called meta-analysis and presented using summary visualisations such as forest plots (or blobbograms) ( Figure 5 ). This can be done only if the results can be combined in a meaningful way.

Meta-analysis can be carried out using common statistical and data science software, such as the cross-platform ‘R’ ( https://www.r-project.org), or by using standalone software, such as Review Manager (RevMan) produced by the Cochrane community ( https://tinyurl.com/revman-5), which is currently developing a cross-platform version RevMan Web.

Carrying out a systematic review is a time-consuming process, that on average takes between 6 and 18 months and requires skill from those involved. Ideally, several reviewers will work on a review to reduce bias. Experts such as librarians should be consulted and included where possible in review teams to leverage their expertise.

Systematic reviews should present the state of the art (most recent/up-to-date developments) concerning a specific topic and aim to be systematic and reproducible. Reproducibility is aided by transparent reporting of the various stages of a review using reporting frameworks such as PRISMA for standardisation. A high-quality review should present a summary of a specific topic to a high standard upon which other professionals can base subsequent care decisions that increase the quality of evidence-based clinical practice.

- Systematic reviews remain one of the most trusted sources of high-quality information from which to make clinical decisions

- Understanding the components of a review will help practitioners to better assess their quality

- Many formal frameworks exist to help structure and report reviews, the use of which is recommended for reproducibility

- Experts such as librarians can be included in the review team to help with the review process and improve its quality

CPD reflective questions

- Where should high-quality qualitative research sit regarding the hierarchies of evidence?

- What background and expertise should those conducting a systematic review have, and who should ideally be included in the team?

- Consider to what extent inter-rater agreement is important in the screening process

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 16 May 2019

An analysis of current practices in undertaking literature reviews in nursing: findings from a focused mapping review and synthesis

- Helen Aveyard ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5133-3356 1 &

- Caroline Bradbury-Jones 2

BMC Medical Research Methodology volume 19 , Article number: 105 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

37k Accesses

23 Citations

10 Altmetric

Metrics details

In this paper we discuss the emergence of many different methods for doing a literature review. Referring back to the early days, when there were essentially two types of review; a Cochrane systematic review and a narrative review, we identify how the term systematic review is now widely used to describe a variety of review types and how the number of available methods for doing a literature review has increased dramatically. This led us to undertake a review of current practice of those doing a literature review and the terms used to describe them.

We undertook a focused mapping review and synthesis. Literature reviews; defined as papers with the terms review or synthesis in the title, published in five nursing journals between January 2017–June 2018 were identified. We recorded the type of review and how these were undertaken.

We identified more than 35 terms used to describe a literature review. Some terms reflected established methods for doing a review whilst others could not be traced to established methods and/or the description of method in the paper was limited. We also found inconsistency in how the terms were used.

We have identified a proliferation of terms used to describe doing a literature review; although it is not clear how many distinct methods are being used. Our review indicates a move from an era when the term narrative review was used to describe all ‘non Cochrane’ reviews; to a time of expansion when alternative systematic approaches were developed to enhance rigour of such narrative reviews; to the current situation in which these approaches have proliferated to the extent so that the academic discipline of doing a literature review has become muddled and confusing. We argue that an ‘era of consolidation’ is needed in which those undertaking reviews are explicit about the method used and ensure that their processes can be traced back to a well described, original primary source.

Peer Review reports

Over the past twenty years in nursing, literature reviews have become an increasingly popular form of synthesising evidence and information relevant to the profession. Along with this there has been a proliferation of publications regarding the processes and practicalities of reviewing [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ], This increase in activity and enthusiasm for undertaking literature reviews is paralleled by the foundation of the Cochrane Collaboration in 1993. Developed in response to the need for up-to-date reviews of evidence of the effectiveness of health care interventions, the Cochrane Collaboration introduced a rigorous method of searching, appraisal and analysis in the form of a ‘handbook’ for doing a systematic review [ 5 ] .Subsequently, similar procedural guidance has been produced, for example by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) [ 6 ] and The Joanna Briggs Institute [ 7 ]. Further guidance has been published to assist researchers with clarity in the reporting of published reviews [ 8 ].

In the early days of the literature review era, the methodological toolkit for those undertaking a literature was polarised, in a way that mirrored the paradigm wars of the time within mixed-methods research [ 9 ]. We refer to this as the ‘dichotomy era’ (i.e. the 1990s), The prominent methods of literature reviewing fell into one of two camps: The highly rigorous and systematic, mostly quantitative ‘Cochrane style’ review on one hand and a ‘narrative style’ review on the other hand, whereby a body of literature was summarised qualitatively, but the methods were often not articulated. Narrative reviews were particularly popular in dissertations and other student work (and they continue to be so in many cases) but have been criticised for a lack of systematic approach and consequently significant potential for bias in the findings [ 10 , 11 ].

The latter 1990s and early 2000, saw the emergence of other forms of review, developed as a response to the Cochrane/Narrative dichotomy. These alternative approaches to the Cochrane review provided researchers with reference points for performing reviews that drew on different study types, not just randomised controlled trials. They promoted a systematic and robust approach for all reviews, not just those concerned with effectiveness of interventions and treatments. One of the first published description of methods was Noblet and Hare’s (1998) ‘Meta-ethnography’ [ 12 ]. This method, although its name suggests otherwise, could incorporate and synthesise all types of qualitative research, not just ethnographies. The potential confusion regarding the inclusion of studies that were not ethnographies within a meta-ethnography, promoted the description of other similar methods, for example, the meta-synthesis of Walsh and Downe (2005) [ 13 ] and the thematic synthesis of Thomas and Harden (2008) [ 14 ]. Also, to overcome the dichotomy of the quantitative/qualitative reviews, the integrative review was described according to Whitemore and Knafl (2005) [ 15 ]. These reviews can be considered to be literature reviews that have been done in a systematic way but not necessarily adhering to guidelines established by the Cochrane Collaboration. We conceptualise this as the ‘expansion era’. Some of the methods are summarised in Table 1 .

Over the past two decades there has been a proliferation of review types, with corresponding explosion of terms used to describe them. A review of evidence synthesis methodologies by Grant and Booth in 2009 [ 20 ] identified 14 different approaches to reviewing the literature and similarly, Booth and colleagues [ 21 ] detailed 19 different review types, highlighting the range of review types currently available. We might consider this the ‘proliferation era’. This is however, somewhat a double-edged sword, because although researchers now have far more review methods at their disposal, there is risk of confusion in the field. As Sabatino and colleagues (2014) [ 22 ] have argued, review methods are not always consistently applied by researchers.

Aware of such potential inconsistency and also our own confusion at times regarding the range of review methods available, we questioned what was happening within our own discipline of nursing. We undertook a snap-shot, contemporary analysis to explore the range of terms used to describe reviews, the methods currently described in nursing and the underlying trends and patterns in searching, appraisal and analysis adopted by those doing a literature review. The aim was to gain some clarity on what is happening within the field, in order to understand, explain and critique what is happening within the proliferation era.

In order to explore current practices in doing a literature review, we undertook a ‘Focused Mapping Review and Synthesis’ (FMRS) – an approach that has been described only recently. This form of review [ 19 ] is a method of investigating trends in academic publications and has been used in a range of issues relevant to nursing and healthcare, for example, theory in qualitative research [ 23 ] and vicarious trauma in child protection research [ 24 ].

A FMRS seeks to identify what is happening within a particular subject or field of inquiry; hence the search is restricted to a particular time period and to pre-identified journals. The review has four distinct features: It: 1) focuses on identifying trends in an area rather than a body of evidence; 2) creates a descriptive map or topography of key features of research within the field rather than a synthesis of findings; 3) comments on the overall approach to knowledge production rather than the state of the evidence; 4) examines this within a broader epistemological context. These are translated into three specific focused activities: 1) targeted journals; 2) a specific subject; 3) a defined time period. The FMRS therefore, is distinct from other forms of review because it responds to questions concerned with ‘what is happening in this field?’ It was thus an ideal method to investigate current practices in literature reviews in nursing.

Using the international Scopus (2016) SCImago Journal and Country Rank, we identified the five highest ranked journals in nursing at that time of undertaking the review. There was no defined method for determining the number of journals to include in a review; the aim was to identify a sample and we identified five journals in order to search from a range of high ranking journals. We discuss the limitations of this later. Journals had to have ‘nursing’ or ‘nurse’ in the title and we did not include journals with a specialist focus, such as nutrition, cancer etcetera. The included journals are shown in Table 2 and are in order according to their ranking. We recognise that our journal choice meant that only articles published in English made it into the review.

A key decision in a FMRS is the time-period within which to retrieve relevant articles. Like many other forms of review, we undertook an initial scoping to determine the feasibility and parameters of the project [ 19 ]. In our previous reviews, the timeframe has varied from three months [ 23 ] to 6 years [ 24 ]. The main criterion is the likelihood for the timespan to contain sufficient articles to answer the review questions. We set the time parameter from January 2017–June 2018. We each took responsibility for two and three journals each from which to retrieve articles. We reviewed the content page of each issue of each journal. For our purposes, in order to reflect the diverse range of terms for describing a literature review, as described earlier in this paper, any paper that contained the term ‘review’ or ‘synthesis’ in the title was included in the review. This was done by each author individually but to enhance rigour, we worked in pairs to check each other’s retrieval processes to confirm inter-rater consistency. This process allowed any areas of uncertainty to be discussed and agreed and we found this form of calibration crucial to the process. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Table 3 .

Articles meeting the inclusion criteria, papers were read in full and data was extracted and recorded as per the proforma developed for the study (Table 4 ). The proforma was piloted on two papers to check for usability prior to data extraction. Data extraction was done independently but we discussed a selection of papers to enhance rigour of the process. No computer software was used in the analysis of the data. We did not critically appraise the included studies for quality because our purpose was to profile what is happening in the field rather than to draw conclusions from the included studies’ findings.

Once the details from all the papers had been extracted onto the tables, we undertook an analysis to identify common themes in the included articles. Because our aim was to produce a snap-shot profile, our analysis was thematic and conceptual. Although we undertook some tabulation and numerical analysis, our primary focus was on capturing patterns and trends characterised by the proliferation era. In line with the FMRS method, in the findings section we have used illustrative examples from the included articles that reflect and demonstrate the point or claim being made. These serve as useful sources of information and reference for readers seeking concrete examples.

Between January 2017 and June 2018 in the five journals we surveyed, a total of 222 papers with either ‘review’ or ‘synthesis’ in the title were retrieved and included in our analysis. We identified three primary themes: 1) Proliferation in names for doing a review; 2) Allegiance to an established review method; 3) Clarity about review processes. The results section is organised around these themes.

Proliferation in names for doing a review

We identified more than 35 terms used by authors to describe a literature review. Because we amalgamated terms such as ‘qualitative literature review’ and ‘qualitative review’ the exact number is actually slightly higher. It was clear from reading the reviews that many different terms were used to describe the same processes. For example qualitative systematic review, qualitative review and meta-synthesis, qualitative meta-synthesis, meta-ethnography all refer to a systematic review of qualitative studies. We have therefore grouped together the review types that refer to a particular type of review as described by the authors of the publications used in this study (Table 5 ).

In many reviews, the specific type of review was indicated in the title as seen for example in Table 5 . A striking feature was that all but two of the systematic reviews that contained a meta-analysis were labelled as such in the title; providing clarity and ease of retrieval. Where a literature review did not contain a meta-analysis, the title of the paper was typically referred to a ‘systematic review’; the implication being that a systematic review is not necessarily synonymous with a meta-analysis. However as discussed in the following section, this introduced some muddying of water, with different interpretations of what systematic review means and how broadly this term is applied. Some authors used the methodological type of included papers to describe their review. For example, a Cochrane-style systematic review was undertaken [ 25 ] but the reviewers did not undertake a meta-analysis and thus referred to their review as a ‘quantitative systematic review’.

Allegiance to an established literature review method

Many literature reviews demonstrated allegiance to a defined method and this was clearly and consistently described by the authors. For example, one team of reviewers [ 26 ] articulately described the process of a ‘meta-ethnography’ and gave a detailed description of their study and reference to the origins of the method by Noblet and Hare (1988) [ 12 ]. Another popular method was the ‘integrative review’ where most authors referred to the work of one or two seminal papers where the method was originally described (for example, Whitemore & Knafl 2005 [ 15 ]).

For many authors the term systematic review was used to mean a review of quantitative research, but some authors [ 27 , 28 , 29 ],used the term systematic review to describe reviews containing both qualitative and quantitative data.

However in many reviews, commitment to a method for doing a literature review appeared superficial, undeveloped and at times muddled. For example, three reviews [ 30 , 31 , 32 ] , indicate an integrative review in the title of their review, but this is the only reference to the method; there is no further reference to how the components of an integrative review are addressed within the paper. Other authors do not state allegiance to any particular method except to state a ‘literature review’ [ 33 ] but without an outline of a particular method for doing so. Anther review [ 34 ] reports a ‘narrative review’ but does not give further information about how this was done, possibly indicative of the lack of methods associated with the traditional narrative review. Three other reviewers documented how they searched, appraised and analysed their literature but do not reference an over-riding approach for their review [ 35 , 36 , 37 ]. In these examples, the review can be assumed to be a literature review, but the exact approach is not clear.

In other reviews, the methods for doing a literature review appear to be used interchangeably. For example in one review [ 38 ] the term narrative review was used in the title but in the main text an integrative review was described. In another review [ 39 ] two different and distinct methods were combined in a ‘meta-ethnographic meta-synthesis’.

Some authors [ 40 , 41 ] referred to a method used to undertake their review, for example a systematic review, but did not reference the primary source from where the method originated. Instead a secondary source, such as a textbook is used to reference the approach taken [ 20 , 42 ].

Clarity about review processes

Under this theme we discerned two principal issues: searching and appraisal. The majority of literature reviews contain three components- searching, appraisal and analysis, details of which are usually reported in the methods section of the papers. However, this is not always the case and for example, one review [ 43 ] provides only a search strategy with no information about the overall method or how critical appraisal or analysis were undertaken. Despite the importance of the process of analysis, we found little discussion of this in the papers reviewed.

The overwhelming trend for those doing a literature review was to describe a comprehensive search; although for many in our sample, a comprehensive search appeared to be limited to a database search; authors did not describe additional search strategies that would enable them to find studies that might be missed through electronic searching. Furthermore, authors did not define what a comprehensive search entailed, for example whether this included grey literature. We identified a very small number of studies where authors had undertaken a purposive sample [ 26 , 44 ]; in these reviews authors clearly stated that their search was for ‘seminal papers’ rather than all papers.

We reviewed the approaches to critical appraisal described in the papers and there were varying interpretations of what this means and which aspect of the included articles were to be subject to appraisal. Some authors [ 36 , 45 , 46 ] used the term ‘critical appraisal’ to refer to relevance of the paper to the review, rather than quality criteria. In that sense critical appraisal was used more as an inclusion criterion regarding relevance, rather than quality in the methods used. Mostly though, the term was used to describe the process of critical analysis of the methodological quality of included papers included in a review. When the term was used in this way to refer to quality criteria, appraisal tools were often used; for example, one review [ 47 ] provides a helpful example when they explain how a particular critical appraisal tool was used to asses the quality of papers in their review. Formal critical appraisal was undertaken by the vast majority reviewers, however the role of critical appraisal in the paper was often not explained [ 33 , 48 ]. It was common for a lot of detail to be provided about the approach to appraisal, including how papers were assessed and how disagreements between reviewers about the quality of individual papers were resolved, with no further mention of the subsequent role of the appraisal in the review. The reason for doing the critical appraisal in the review was often unclear and furthermore, in many cases, researchers included all papers within their review regardless of quality. For example, one team of reviewers [ 49 ] explained how the process, in their view, is not to exclude studies but to highlight the quality of evidence available. Another team of reviewers described how they did not exclude studies on the basis of quality because of the limited amount of research available on the topic [ 50 ].

Our review has identified a multiplicity of similar terms and approaches used by authors when doing a literature review, that we suggests marks the ‘proliferation era’. The expansion of terms used to describe a literature review has been observed previously [ 19 , 21 ]. We have identified an even wider range of terms, indicating that this trend may be increasing. This is likely to give the impression of an incoherent and potentially confusing approach to the scholarly undertaking of doing a literature review and is likely to be particularly problematic for novice researchers and students when attempting to grapple with the array of approaches available to them. The range of terms used in the title of papers to describe a literature review may cause both those new to research to wonder what the difference is between a qualitative evidence synthesis and a qualitative systematic review and which method is most suitable for their enquiry.

The clearest articles in our review were those that reported a systematic review with or without a meta-analysis. For example, one team of reviewers [ 25 ] undertook a Cochrane-style systematic review but did not undertake a meta-analysis and thus referred to their review as a ‘quantitative systematic review’. We found this form of labelling clear and helpful and is indeed in line with current recommendations [ 8 ]. While guidelines exist for the publication of systematic reviews [ 8 , 51 ], given the range of terms that are used by authors, some may be unclear when these guidelines should apply and this adds some confusion to the field. Of course, authors are at liberty to call their review processes whatever they deem appropriate, but our analysis has unearthed some inconsistencies that are confusing to the field of literature reviewing.

There is current debate about the status of literature reviews that are not ‘Cochrane’ style reviews [ 52 ]. Classification can be complex and whilst it might be tempting to refer to all non Cochrane-style reviews as ‘narrative reviews’ [ 52 ], literature reviews that conform to a recognised method would generally not be considered as such [ 53 ] and indeed the Cochrane Collaboration handbook refers to the principles of systematic review as applicable to different types of evidence, not just randomised controlled trials [ 5 ] .This raises the question as to whether the term systematic review should be an umbrella term referring to any review with an explicit method; which is implicit in the definition of a systematic review, but which raises the question as to how rigorous a method has to be to meet these standards, a thorny issue which we have identified in this study.

This review has identified a lack of detail in the reporting of the methods used by those doing a review. In 2017, Thorne raised the rhetorical question: ‘What kind of monster have we created?‘ [ 54 ]. Critiquing the growing investment in qualitative metasyntheses, she observed that many reviews were being undertaken that position themselves as qualitative metasyntheses, yet are theoretically and methodologically superficial. Thorne called for greater clarity and sense of purpose as the ‘trend in synthesis research marches forward’ [ 54 ]. Our review covered many review types, not just the qualitative meta-synthesis and its derivatives. However, we concur with Thorne’s conclusion that research methods are not extensively covered or debated in many of the published papers which might explain the confusion of terms and mixing of methods.

Despite the proliferation in terms for doing a literature review, and corresponding associated different methods and a lack of consistency in their application, our review has identified how the methods used (or indeed the reporting of the methods) appear to be remarkably similar in most publications. This may be due to limitations in the word count available to authors. However for example, the vast majority of papers describe a comprehensive search, critical appraisal and analysis. The approach to searching is of particular note; whilst comprehensive searching is the cornerstone of the Cochrane approach, other aproaches advocate that a sample of literature is sufficient [ 15 , 20 ]. Yet in our review we found only two examples where reviewers had used this approach, despite many other reviews claiming to be undertaking a meta-ethnography or meta-synthesis. This indicates that many of those doing a literature review have defaulted to the ‘comprehensive search’ irrespective of the approach to searching suggested in any particular method which is again indicative of confusion in the field.

Differences are reported in the approach to searching and critical appraisal and these appear not to be linked to different methods, but seem to be undertaken on the judgement and discretion of the reviewers without rationale or justification within the published paper. It is not for us to question researchers’ decisions as regards managing the flow of articles through their reviews, but when it comes to the issue of both searching and lack of clarity about the role of critical appraisal there is evidence of inconsistency by those doing a literature review. This reflects current observations in the literature where the lack of clarity about the role of critical appraisal within a literature review is debated . [ 55 , 56 ].

Our review indicates that many researchers follow a very similar process, regardless of their chosen method and the real differences that do exist between published methods are not apparent in many of the published reviews. This concurs with previously mentioned concerns [ 54 ] about the superficial manner in which methods are explored within literature reviews. The overriding tendency is to undertake a comprehensive review, critical appraisal and analysis, following the formula prescribed by Cochrane, even if this is not required by the literature review method stated in the paper. Other researchers [ 52 ] have questioned whether the dominance of the Cochrane review should be questioned. We argue that emergence of different methods for doing a literature review in a systematic way has indeed challenged the perceived dominance of the Cochrane approach that characterised the dichotomy era, where the only alternative was a less rigourous and often poorly described process of dealing with literature. It is positive that there is widespread acknowledgement of the validity of other approaches. But we argue that the expansion era, whereby robust processes were put forward as alternatives that filled the gap left by polarisation, has gone too far. The magnitude in the number of different approaches identified in this review has led to a confused field. Thorne [ 54 ] refers to a ‘meta-madness’; with the proliferation of methods leading to the oversimplification of complex literature and ideas. We would extend this to describe a ‘meta-muddle’ in which, not only are the methods and results oversimplified, but the existence of so many terms used to describe a literature review, many of them used interchangeably, has added a confusion to the field and prevented the in-depth exploration and development of specific methods. Table 6 shows the issues associated with the proliferation era and importantly, it also highlights the recommendations that might lead to a more coherent reviewing community in nursing.

The terms used for doing a literature review are often used both interchangeably and inconsistently, with minimal description of the methods undertaken. It is not surprising therefore that some journal editors do not index these consistently within the journal. For example, in one edition of one journal included in the review, there are two published integrative reviews. One is indexed in the section entitled as a ‘systematic review’, while the other is indexed in a separate section entitled ‘literature review’. In another edition of a journal, two systematic reviews with meta-analysis are published. One is listed as a research article and the other as a review and discussion paper. It seems to us then, that editors and publishers might sometimes also be confused and bewildered themselves.

Whilst guidance does exist for the publication of some types of systematic reviews in academic journals; for example the PRISMA statement [ 8 ] and Entreq guidelines [ 51 ], which are specific to particular qualitative synthesis, guidelines do not exist for each approach. As a result, for those doing an alternative approach to their literature review, for example an integrative review [ 15 ], there is only general publication guidance to assist. In the current reviewing environment, there are so many terms, that more specific guidance would be impractical anyway. However, greater clarity about the methods used and halting the introduction of different terms to mean the same thing will be helpful.

Limitations

This study provides a snapshot of the way in which literature reviews have been described within a short publication timeframe. We were limited for practical reasons to a small section of high impact journals. Including a wider range of journals would have enhanced the transferability of the findings. Our discussion is, of course, limited to the review types that were published in the timeframe, in the identified journals and which had the term ‘review’ or ‘synthesis’ in the title. This would have excluded papers that were entitled ‘meta-analysis’. However as we were interested in the range of reviews that fall outside the scope of a meta-analysis, we did not consider that this limited the scope of the paper. Our review is further limited by the lack of detail of the methods undertaken provided in many of the papers reviewed which, although providing evidence for our arguments, also meant that we had to assume meaning that was unclear from the text provided.

The development of rigorous methods for doing a literature review is to be welcomed; not all review questions can be answered by Cochrane style reviews and robust methods are needed to answer review questions of all types. Therefore whilst we welcome the expansion in methods for doing a literature review, the proliferation in the number of named approaches should be, in our view, a cause for reflection. The increase in methods could be indicative of an emerging variation in possible approaches; alternatively, the increase could be due to a lack of conceptual clarity where, on closer inspection, the methods do not differ greatly and could indeed be merged. Further scrutiny of the methods described within many papers support the latter situation but we would welcome further discussion about this. Meanwhile, we urge researchers to make careful consideration of the method they adopt for doing a literature review, to justify this approach carefully and to adhere closely to its method. Having witnessed an era of dichotomy, expansion and proliferation of methods for doing a literature review, we now seek a new era of consolidation.

Bettany-Saltikov J. How to do a systematic literature review in nursing: a step-by-step guide. Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2012.

Google Scholar

Coughlan M, Cronin P, Ryan F. Doing a literature review in nursing, Health and social care. London: Sage; 2013.

Aveyard H. Doing a literature review in health and social care. Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2018.

Davis D. A practical overview of how to conduct a systematic review. Nurs Stand. 2016;31(12):60–70.

Article Google Scholar

Higgins and Green. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0: Cochrane Collaboration; 2011.

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Systematic Reviews: CRD's guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. York: University of York; 2008.

Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer's Manual: The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017. Available from https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org/

Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart L. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols. Br Med J. 2015;2:349 (Jan 02).