What Is a Rhetorical Device? Definition, List, Examples

- An Introduction to Punctuation

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/JS800-800-5b70ad0c46e0fb00501895cd.jpg)

- B.A., English, Rutgers University

A rhetorical device is a linguistic tool that employs a particular type of sentence structure, sound, or pattern of meaning in order to evoke a particular reaction from an audience. Each rhetorical device is a distinct tool that can be used to construct an argument or make an existing argument more compelling.

Any time you try to inform, persuade , or argue with someone, you’re engaging in rhetoric. If you’ve ever had an emotional reaction to a speech or changed your mind about an issue after hearing a skilled debater's rebuttal, you've experienced the power of rhetoric. By developing a basic knowledge of rhetorical devices, you can improve your ability to process and convey information while also strengthening your persuasive skills.

Types of Rhetorical Devices

Rhetorical devices are loosely organized into the following four categories:

- Logos. Devices in this category seek to convince and persuade via logic and reason, and will usually make use of statistics, cited facts, and statements by authorities to make their point and persuade the listener.

- Pathos. These rhetorical devices base their appeal in emotion. This could mean invoking sympathy or pity in the listener, or making the audience angry in the service of inspiring action or changing their mind about something.

- Ethos. Ethical appeals try to convince the audience that the speaker is a credible source, that their words have weight and must be taken seriously because they are serious and have the experience and judgment necessary to decide what’s right.

- Kairos. This is one of the most difficult concepts in rhetoric; devices in this category are dependent on the idea that the time has come for a particular idea or action. The very timeliness of the idea is part of the argument.

Top Rhetorical Devices

Since rhetoric dates back to ancient times, much of the terminology used to discuss it comes from the original Greek. Despite its ancient origins, however, rhetoric is as vital as ever. The following list contains some of the most important rhetorical devices to understand:

- Alliteration , a sonic device, is the repetition of the initial sound of each word (e.g. Alan the antelope ate asparagus).

- Cacophony , a sonic device, is the combination of consonant sounds to create a displeasing effect.

- Onomatopoeia , a sonic device, refers to a word that emulates the real-life sound it signifies (e.g. using the word "bang" to signify an explosion).

- Humor creates connection and identification with audience members, thus increasing the likelihood that they will agree with the speaker. Humor can also be used to deflate counter-arguments and make opposing points of view appear ridiculous.

- Anaphora is the repetition of certain words or phrases at the beginning of sentences to increase the power of a sentiment. Perhaps the best-known example of anaphora is Martin Luther King Jr.'s repetition of the phrase "I have a dream."

- Meiosis is a type of euphemism that intentionally understates the size or importance of its subject. It can be used to dismiss or diminish a debate opponent's argument.

- Hyperbole is an exaggerated statement that conveys emotion and raises the bar for other speakers. Once you make a hyperbolic statement like “My idea is going to change the world," other speakers will have to respond in kind or their more measured words may seem dull and uninspiring in comparison.

- Apophasis is the verbal strategy of bringing up a subject by denying that that very subject should be brought up at all.

- Anacoluthon is a sudden swerve into a seemingly unrelated idea in the middle of a sentence. It can seem like a grammatical mistake if handled poorly, but it can also put powerful stress onto the idea being expressed.

- Chiasmus is a technique wherein the speaker inverts the order of a phrase in order to create a pretty and powerful sentence. The best example comes from President John F. Kennedy's inaugural address: "Ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country ."

- Anadiplosis is the use of the same word at the end of one sentence and at the beginning of the subsequent sentence, forming a chain of thought that carries your audience to the point you’ve chosen.

- Dialogismus refers to moments when the speaker imagines what someone else is thinking, or speaks in the voice of someone else, in order to explain and then subvert or undermine counterpoints to the original argument.

- Eutrepismus , one of the most common rhetorical devices, is simply the act of stating points in the form of a numbered list. Why is it useful? First off, this devices makes information seem official and authoritative. Second, it gives speech a sense of order and clarity. And third, it helps the listener keep track of the speaker's points.

- Hypophora is the trick of posing a question and then immediately supplying the answer. Do you know why hypophora is useful? It's useful because it stimulates listener interest and creates a clear transition point in the speech.

- Expeditio is the trick of listing a series of possibilities and then explaining why all but one of those possibilities are non-starters. This device makes it seem as though all choices have been considered, when in fact you've been steering your audience towards the one choice you desired all along.

- Antiphrasis is another word for irony. Antiphrasis refers to a statement whose actual meaning is the opposite of the literal meaning of the words within it.

- Asterismos. Look, this is the technique of inserting a useless but attention-grabbing word in front of your sentence in order to grab the audience’s attention. It's useful if you think your listeners are getting a bit bored and restless.

Examples of Rhetorical Devices

Rhetoric isn’t just for debates and arguments. These devices are used in everyday speech, fiction and screenwriting, legal arguments, and more. Consider these famous examples and their impact on their audience.

- “ Fear leads to anger. Anger leads to hate. Hate leads to suffering.” – Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back . Rhetorical Device : Anadiplosis. The pairs of words at the beginning and ending of each sentence give the impression that the logic invoked is unassailable and perfectly assembled.

- “ Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.” —President John F. Kennedy. Rhetorical Device : Chiasmus. The inversion of the phrase can do and the word country creates a sense of balance in the sentence that reinforces the sense of correctness.

- "I will not make age an issue of this campaign. I am not going to exploit, for political purposes, my opponent’s youth and inexperience." –President Ronald Reagan Rhetorical Device : Apophasis. In this quip from a presidential debate, Reagan expresses mock reluctance to comment on his opponent's age, which ultimately does the job of raising the point of his opponent's age.

- “ But in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate, we cannot consecrate, we cannot hallow this ground.” —Abraham Lincoln, Gettysburg Address . Rhetorical Device : Anaphora. Lincoln’s use of repetition gives his words a sense of rhythm that emphasizes his message. This is also an example of kairos : Lincoln senses that the public has a need to justify the slaughter of the Civil War, and thus decides to make this statement appealing to the higher purpose of abolishing slavery.

- “ Ladies and gentlemen, I've been to Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan, and I can say without hyperbole that this is a million times worse than all of them put together.” – The Simpsons . Rhetorical Device : Hyperbole. Here, hyperbole is used to humorous effect in order to undermine the superficial point of the sentence.

- Rhetoric. The discipline of discourse and persuasion via verbal argument.

- Rhetorical Device. A tool used in the course of rhetoric, employing specific sentence structure, sounds, and imagery to attain a desired response.

- Logos. The category of rhetorical devices that appeal to logic and reason.

- Pathos. The category of rhetorical devices that appeal to emotions.

- Ethos. The category of rhetorical devices that appeals to a sense of credibility.

- Kairos. The concept of “right place, right time” in rhetoric, wherein a specific rhetorical device becomes effective because of circumstances surrounding its use.

- “16 Rhetorical Devices That Will Improve Your Public Speaking.” Duarte , 19 Mar. 2018, www.duarte.com/presentation-skills-resources/rhetoric-isnt-a-bad-thing-16-rhetorical-devices-regularly-used-by-steve-jobs/.

- Home - Ethos, Pathos, and Logos, the Modes of Persuasion ‒ Explanation and Examples , pathosethoslogos.com/ .

- McKean, Erin. “Rhetorical Devices.” Boston.com , The Boston Globe, 23 Jan. 2011, archive.boston.com/bostonglobe/ideas/articles/2011/01/23/rhetorical_devices/ .

- The Top 20 Figures of Speech

- Figure of Speech: Definition and Examples

- Anadiplosis: Definition and Examples

- AP English Exam: 101 Key Terms

- Words, Phrases, and Arguments to Use in Persuasive Writing

- Use Social Media to Teach Ethos, Pathos and Logos

- Artistic Proofs: Definitions and Examples

- Traductio: Rhetorical Repetition

- Pathos in Rhetoric

- Polyptoton (Rhetoric)

- Brief Introductions to Common Figures of Speech

- Chiasmus Figure of Speech

- What Are Tropes in Language?

- Peroration: The Closing Argument

- Persuasion and Rhetorical Definition

- Logos (Rhetoric)

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, the 20 most useful rhetorical devices.

General Education

Rhetoric is the art of effective communication; if you communicate with others at all, rhetorical devices are your friends!

Rhetorical devices help you make points more effectively, and help people understand you better. In this article, I'll be covering some important rhetorical devices so you can improve your own writing!

What Are Rhetorical Devices?

A lot of things that you would think of as just regular everyday modes of communicating are actually rhetorical devices That’s because ‘rhetorical devices’ is more or less a fancy way of saying ‘communication tools.’

Most people don’t plan out their use of rhetorical devices in communication, both because nobody thinks, “now would be a good time to use synecdoche in this conversation with my grocery clerk,” and because we use them so frequently that they don’t really register as “rhetorical devices.”

How often have you said something like, “when pigs fly!” Of those times, how often have you thought, “I’m using a rhetorical device!” That’s how ubiquitous they are!

However, being aware of what they are and how to use them can strengthen your communication , whether you do a lot of big speeches, write persuasive papers, or just argue with your friends about a TV show you all like.

Rhetorical devices can function at all levels: words, sentences, paragraphs, and beyond. Some rhetorical devices are just a single word, such as onomatopoeia. Others are phrases, such as metaphor, while still others can be sentence-length (such as a thesis), paragraph-length (hypophora), or go throughout the entire piece, such as a standard five-paragraph essay.

Many of these (such as the thesis or five-paragraph essay) are so standard and familiar to us that we may not think of them as devices. But because they help us shape and deliver our arguments effectively, they're important to know and understand.

The Most Useful Rhetorical Devices List

It would be impossible to list every single rhetorical device in one blog post. Instead, I've collected a mixture of extremely common devices you may have heard before and some more obscure ones that might be valuable to learn.

Amplification

Amplification is a little similar to parallelism: by using repetition, a writer expands on an original statement and increases its intensity .

Take this example from Roald Dahl’s The Twits :

“If a person has ugly thoughts, it begins to show on the face. And when that person has ugly thoughts every day, every week, every year, the face gets uglier and uglier until you can hardly bear to look at it. A person who has good thoughts cannot ever be ugly. You can have a wonky nose and a crooked mouth and a double chin and stick-out teeth, but if you have good thoughts it will shine out of your face like sunbeams and you will always look lovely.”

In theory, we could have gotten the point with the first sentence. We don’t need to know that the more you think ugly thoughts, the uglier you become, nor that if you think good thoughts you won’t be ugly—all that can be contained within the first sentence. But Dahl’s expansion makes the point clearer, driving home the idea that ugly thoughts have consequences.

Amplification takes a single idea and blows it up bigger, giving the reader additional context and information to better understand your point. You don’t just have to restate the point— use amplification to expand and dive deeper into your argument to show readers and listeners how important it is!

Anacoluthon

Anacoluthon is a fancy word for a disruption in the expected grammar or syntax of a sentence. That doesn’t mean that you misspoke—using anacoluthon means that you’ve deliberately subverted your reader’s expectations to make a point.

For example, take this passage from King Lear :

“I will have such revenges on you both, That all the world shall—I will do such things, What they are, yet I know not…”

In this passage, King Lear interrupts himself in his description of his revenge. This has multiple effects on the reader: they wonder what all the world shall do once he has his revenge (cry? scream? fear him?), and they understand that King Lear has interrupted himself to regain his composure. This tells us something about him—that he’s seized by passion in this moment, but also that he regains control. We might have gathered one of those things without anacoluthon, but the use of this rhetorical device shows us both very efficiently.

Anadiplosis

Anadiplosis refers to purposeful repetition at the end of one sentence or clause and at the beginning of the next sentence or clause. In practice, that looks something like a familiar phrase from Yoda:

“Fear leads to anger. Anger leads to hate. Hate leads to suffering.”

Note the way that the ending word of each sentence is repeated in the following sentence. That’s anadiplosis!

This rhetorical device draws a clear line of thinking for your reader or listener—repetition makes them pay closer attention and follow the way the idea evolves. In this case, we trace the way that fear leads to suffering through Yoda’s purposeful repetition.

Antanagoge is the balancing of a negative with a positive. For example, the common phrase, “When life gives you lemons, make lemonade,” is antanagoge—it suggests a negative (lots of lemons) and follows that up with a positive (make lemonade).

When writing persuasively, this can be a great way to respond to potential detractors of your argument. Suppose you want to convince your neighborhood to add a community garden, but you think that people might focus on the amount of work required. When framing your argument, you could say something like, “Yes, it will be a lot of work to maintain, but working together will encourage us all to get to know one another as well as providing us with fresh fruits, vegetables, and flowers.”

This is a little like procatalepsis, in that you anticipate a problem and respond to it. However, antanagoge is specifically balancing a negative with a positive, just as I did in the example of a garden needing a lot of work, but that work is what ultimately makes the project worth it.

Apophasis is a form of irony relating to denying something while still saying it. You’ll often see this paired with phrases like, “I’m not saying…” or “It goes without saying…”, both of which are followed up with saying exactly what the speaker said they weren’t going to say.

Take this speech from Iron Man 2 :

"I'm not saying I'm responsible for this country's longest run of uninterrupted peace in 35 years! I'm not saying that from the ashes of captivity, never has a phoenix metaphor been more personified! I'm not saying Uncle Sam can kick back on a lawn chair, sipping on an iced tea, because I haven't come across anyone man enough to go toe to toe with me on my best day! It's not about me."

Tony Stark isn’t saying that he’s responsible for all those things… except that’s exactly what he is saying in all of his examples. Though he says it’s not about him, it clearly is—all of his examples relate to how great he is, even as he proclaims that they aren’t.

A scene like this can easily be played for humor, but apophasis can also be a useful (albeit deceptive) rhetorical tool. For example, this argument:

Our neighborhood needs a community garden to foster our relationships with one another. Not only is it great for getting to know each other, but a community garden will also provide us with all kinds of fresh fruit and vegetables. It would be wrong to say that people who disagree aren’t invested in others’ health and wellness, but those who have the neighborhood’s best interests in mind will support a community garden.

That last sentence is all apophasis. Not only did I imply that people who don’t support the community garden are anti-social and uncaring (by outright stating that I wouldn’t say that, but I also implied that they’re also not invested in the neighborhood at all. Stating things like this, by pretending you’re not saying them or saying the opposite, can be very effective.

Assonance and Alliteration

Assonance adds an abundance of attractive accents to all your assertions. That’s assonance—the practice repeating the same vowel sound in multiple words in a phrase or sentence, often at the beginning of a word, to add emphasis or musicality to your work. Alliteration is similar, but uses consonant sounds instead of vowel sounds.

Let’s use Romeo and Juliet as an example again:

“From forth the fatal loins of these two foes; A pair of star-cross’d lovers take their life.”

Here, we have repetition of the sounds ‘f’ and ‘l’ in ‘from forth...fatal...foes,’ and ‘loins...lovers...life.’

Even if you don’t notice the repetition as you’re reading, you can hear the effects in how musical the language sounds. Shakespeare could easily have just written something like, “Two kids from families who hate one another fell in love and died by suicide,” but that’s hardly as evocative as the phrasing he chose.

Both assonance and alliteration give your writing a lyrical sound, but they can do more than that, too. These tools can mimic associated sounds, like using many ‘p’ sounds to sound like rain or something sizzling, or ‘s’ sounds to mimic the sounds of a snake. When you’re writing, think about what alternative meanings you can add by emphasizing certain sounds.

Listen, asterismos is great. Don’t believe me? How did you feel after I began the first sentence with the word ‘listen?’ Even if you didn’t feel more inspired to actually listen, you probably paid a bit more attention because I broke the expected form. That’s what asterismos is—using a word or phrase to draw attention to the thought that comes afterward.

‘Listen’ isn’t the only example of asterismos, either. You can use words like, ‘hey,’ ‘look,’ ‘behold,’ ‘so,’ and so on. They all have the same effect: they tell the reader or listener, “Hey, pay attention—what I’m about to say is important.”

Dysphemism and Euphemism

Euphemism is the substitution of a more pleasant phrase in place of a familiar phrase, and dysphemism is the opposite —an un pleasant phrase substituted in place of something more familiar. These tools are two sides of the same coin. Euphemism takes an unpleasant thing and makes it sound nicer—such as using 'passed away' instead of 'died'—while dysphemism does the opposite, taking something that isn't necessarily bad and making it sound like it is.

We won’t get into the less savory uses of dysphemism, but there are plenty that can leave an impression without being outright offensive. Take ‘snail mail.’ A lot of us call postal mail that without any real malice behind it, but ‘snail’ implies slowness, drawing a comparison between postal mail and faster email. If you’re making a point about how going electronic is faster, better for the environment, and overall more efficient, comparing email to postal mail with the phrase ‘snail mail’ gets the point across quickly and efficiently.

Likewise, if you're writing an obituary, you probably don't want to isolate the audience by being too stark in your details. Using gentler language, like 'passed away' or 'dearly departed' allows you to talk about things that might be painful without being too direct. People will know what you mean, but you won't have to risk hurting anyone by being too direct and final with your language.

You’ve no doubt run into epilogues before, because they’re a common and particularly useful rhetorical device! Epilogues are a conclusion to a story or work that reveals what happens to the characters in the story. This is different from an afterword, which is more likely to describe the process of a book’s creation than to continue and provide closure to a story.

Many books use epilogues to wrap up loose ends, usually taking place in the future to show how characters have changed as a result of their adventures. Both Harry Potter and The Hunger Games series use their epilogues to show the characters as adults and provide some closure to their stories—in Harry Potter , the main characters have gotten married and had children, and are now sending those children to the school where they all met. This tells the reader that the story of the characters we know is over—they’re adults and are settled into their lives—but also demonstrates that the world goes on existing, though it’s been changed forever by the actions of the familiar characters.

Eutrepismus

Eutrepismus is another rhetorical device you’ve probably used before without realizing it. This device separates speech into numbered parts, giving your reader or listener a clear line of thinking to follow.

Eutrepismus is a great rhetorical device—let me tell you why. First, it’s efficient and clear. Second, it gives your writing a great sense of rhythm. Third, it’s easy to follow and each section can be expanded throughout your work.

See how simple it is? You got all my points in an easy, digestible format. Eutrepismus helps you structure your arguments and make them more effective, just as any good rhetorical device should do.

You’ve probably used hypophora before without ever thinking about it. Hypophora refers to a writer or speaker proposing a question and following it up with a clear answer. This is different from a rhetorical question—another rhetorical device—because there is an expected answer, one that the writer or speaker will immediately give to you.

Hypophora serves to ask a question the audience may have (even if they’re not entirely aware of it yet) and provide them with an answer. This answer can be obvious, but it can also be a means of leading the audience toward a particular point.

Take this sample from John F. Kennedy’s speech on going to the moon:

But why, some say, the moon? Why choose this as our goal? And they may well ask why climb the highest mountain? Why, 35 years ago, fly the Atlantic? Why does Rice play Texas? We choose to go to the moon. We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win, and the others, too.

In this speech, Kennedy outright states that he’s asking questions others have asked, and then goes on to answer them. This is Kennedy’s speech, so naturally it’s going to reflect his point of view, but he’s answering the questions and concerns others might have about going to the moon. In doing so, he’s reclaiming an ongoing conversation to make his own point. This is how hypophora can be incredibly effective: you control the answer, leaving less room for argument!

Litotes is a deliberate understatement, often using double negatives, that serves to actually draw attention to the thing being remarked upon. For example, saying something like, “It’s not pretty,” is a less harsh way to say “It’s ugly,” or “It’s bad,” that nonetheless draws attention to it being ugly or bad.

In Frederick Douglass’ Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass: an American Slave , he writes:

“Indeed, it is not uncommon for slaves even to fall out and quarrel among themselves about the relative goodness of their masters, each contending for the superior goodness of his own over that of the others.”

Notice the use of “not uncommon.” Douglass, by using a double negative to make readers pay closer attention, points out that some slaves still sought superiority over others by speaking out in favor of their owners.

Litotes draws attention to something by understating it. It’s sort of like telling somebody not to think about elephants—soon, elephants becomes all they can think about. The double negative draws our attention and makes us focus on the topic because it’s an unusual method of phrasing.

Onomatopoeia

Onomatopoeia refers to a sound represented within text as a mimicry of what that sound actually sounds like. Think “bang” or “whizz” or “oomph,” all of which can mean that something made that kind of a sound—”the door banged shut”—but also mimic the sound itself—”the door went bang .”

This rhetorical device can add emphasis or a little bit of spice to your writing. Compare, “The gunshot made a loud sound,” to “The gun went bang .” Which is more evocative?

Parallelism

Parallelism is the practice of using similar grammar structure, sounds, meter, and so on to emphasize a point and add rhythm or balance to a sentence or paragraph.

One of the most famous examples of parallelism in literature is the opening of Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities :

"It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way— in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only."

In the beginning, every phrase begins with “It was,” which is itself a parallelism. But there are also pairs of parallelism within the sentence, too; “It was the ___ of times, it was the ___ of times,” and “it was the age of ___, it was the age of ___.”

Parallelism draws your reader deeper into what you’re saying and provides a nice sense of flow, even if you’re talking about complicated ideas. The ‘epoch of incredulity’ is a pretty meaty phrase, but Dickens’ parallelism sets up a series of dichotomies for us; even if we don’t know quite what it means, we can figure it out by comparing it to ‘belief.’

Personification

Personification is a rhetorical device you probably run into a lot without realizing it. It’s a form of metaphor, which means two things are being compared without the words like or as—in this case, a thing that is not human is given human characteristics.

Personification is common in poetry and literature, as it’s a great way to generate fresh and exciting language, even when talking about familiar subjects. Take this passage from Romeo and Juliet , for example:

“When well-appareled April on the heel Of limping winter treads.”

April can’t wear clothes or step on winter, and winter can’t limp. However, the language Shakespeare uses here is quite evocative. He’s able to quickly state that April is beautiful (“well-appareled”) and that winter is coming to an end (“limping winter”). Through personification, we get a strong image for things that could otherwise be extremely boring, such as if Shakespeare had written, “When beautiful April comes right after winter.”

Procatalepsis

Procatalepsis is a rhetorical device that anticipates and notes a potential objection, heading it off with a follow-up argument to strengthen the point. I know what you’re thinking—that sounds really complicated! But bear with me, because it’s actually quite simple.

See how that works? I imagined that a reader might be confused by the terminology in the first sentence, so I noted that potential confusion, anticipating their argument. Then, I addressed that argument to strengthen my point—procatalepsis is easy, which you can see because I just demonstrated it!

Anticipating a rebuttal is a great way to strengthen your own argument. Not only does it show that you’ve really put thought into what you’re saying, but it also leaves less room for disagreement!

Synecdoche is a rhetorical device that uses a part of something to stand in for the whole. That can mean that we use a small piece of something to represent a whole thing (saying ‘let’s grab a slice’ when we in fact mean getting a whole pizza), or using something large to refer to something small. We often do this with sports teams–for example, saying that New England won the Super Bowl when we in fact mean the New England Patriots, not the entirety of New England.

This style of rhetorical device adds an additional dimension to your language, making it more memorable to your reader. Which sounds more interesting? “Let’s get pizza,” or “let’s grab a slice?”

Likewise, consider this quote from Percy Bysshe Shelly’s “Ozymandias”:

“Tell that its sculptor well those passions read Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things, The hand that mocked them.”

Here, Shelly uses ‘the hand’ to refer to the sculptor. The hand did not sculpt the lifeless things on its own; it was a tool of the sculptor. But by using just the hand, Shelly avoids repeating ‘the sculptor,’ preserves the poem’s rhythm, and narrows our focus. If he had referred to the sculptor again, he’d still be a big important figure; by narrowing to the hand, Shelly is diminishing the idea of the creator, mirroring the poem’s assertion that the creation will outlast it.

Tautology refers to using words or similar phrases to effectively repeat the same idea with different wording. It’s a form of repetition that can make a point stronger, but it can also be the basis of a flawed argument—be careful that your uses of tautology is the former, not the latter!

For example, take this section of “The Bells” by Edgar Allen Poe:

“Keeping time, time, time, In a sort of Runic rhyme… From the bells, bells, bells, bells.”

Poe’s poetry has a great deal of rhythm already, but the use of ‘time, time, time’ sets us up for the way that ‘bells, bells, bells, bells’ also holds that same rhythm. Keeping time refers to maintaining rhythm, and this poem emphasizes that with repetition, much like the repetitive sound of ringing bells.

An example of an unsuccessful tautology would be something like, “Either we should buy a house, or we shouldn’t.” It’s not a successful argument because it doesn’t say anything at all—there’s no attempt to suggest anything, just an acknowledgment that two things, which cannot both happen, could happen.

If you want to use tautology in your writing, be sure that it’s strengthening your point. Why are you using it? What purpose does it serve? Don’t let a desire for rhythm end up robbing you of your point!

That thing your English teachers are always telling you to have in your essays is an important literary device. A thesis, from the Greek word for ‘a proposition,’ is a clear statement of the theory or argument you’re making in an essay. All your evidence should feed back into your thesis; think of your thesis as a signpost for your reader. With that signpost, they can’t miss your point!

Especially in longer academic writing, there can be so many pieces to an argument that it can be hard for readers to keep track of your overarching point. A thesis hammers the point home so that no matter how long or complicated your argument is, the reader will always know what you’re saying.

Tmesis is a rhetorical device that breaks up a word, phrase, or sentence with a second word, usually for emphasis and rhythm . We often do this with expletives, but tmesis doesn’t have to be vulgar to be effective!

Take this example from Romeo and Juliet :

“This is not Romeo, he’s some other where.”

The normal way we’d hear this phrase is “This is not Romeo, he’s somewhere else.” But by inserting the word ‘other’ between ‘some’ and ‘where,’ it not only forces us to pay attention, but also changes the sentence’s rhythm. It gets the meaning across perfectly, and does so in a way that’s far more memorable than if Shakespeare had just said that Romeo was somewhere else.

For a more common usage, we can turn to George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion , which often has Eliza Doolittle using phrases like “fan-bloody-tastic” and “abso-blooming-lutely.” The expletives—though mild by modern standards—emphasize Eliza’s social standing and make each word stand out more than if she had simply said them normally.

What’s Next?

Rhetorical devices and literary devices can both be used to enhance your writing and communication. Check out this list of literary devices to learn more !

Ethos, pathos, logos, and kairos are all modes of persuasion—types of rhetorical devices— that can help you be a more convincing writer !

No matter what type of writing you're doing, rhetorical devices can enhance it! To learn more about different writing styles, check out this list !

Melissa Brinks graduated from the University of Washington in 2014 with a Bachelor's in English with a creative writing emphasis. She has spent several years tutoring K-12 students in many subjects, including in SAT prep, to help them prepare for their college education.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

31 Useful Rhetorical Devices

What is a rhetorical device and why are they used.

As with all fields of serious and complicated human endeavor (that can be considered variously as an art, a science, a profession, or a hobby), there is a technical vocabulary associated with writing. Rhetoric is the name for the study of writing or speaking as a means of communication or persuasion, and though a writer doesn’t need to know the specific labels for certain writing techniques in order to use them effectively, it is sometimes helpful to have a handy taxonomy for the ways in which words and ideas are arranged. This can help to discuss and isolate ideas that might otherwise become abstract and confusing. As with the word rhetoric itself, many of these rhetorical devices come from Greek.

Ready, set, rhetoric.

The repetition of usually initial consonant sounds in two or more neighboring words or syllables

wild and woolly, threatening throngs

Syntactical inconsistency or incoherence within a sentence especially : a shift in an unfinished sentence from one syntactic construction to another

you really should have—well, what do you expect?

Repetition of a prominent and usually the last word in one phrase or clause at the beginning of the next

rely on his honor—honor such as his?

A literary technique that involves interruption of the chronological sequence of events by interjection of events or scenes of earlier occurrence : flashback

Repetition of a word or expression at the beginning of successive phrases, clauses, sentences, or verses especially for rhetorical or poetic effect

we cannot dedicate—we cannot consecrate—we cannot hallow—this ground

The repetition of a word within a phrase or sentence in which the second occurrence utilizes a different and sometimes contrary meaning from the first

we must all hang together or most assuredly we shall all hang separately

The usually ironic or humorous use of words in senses opposite to the generally accepted meanings

this giant of 3 feet 4 inches

The use of a proper name to designate a member of a class (such as a Solomon for a wise ruler) OR the use of an epithet or title in place of a proper name (such as the Bard for Shakespeare)

The raising of an issue by claiming not to mention it

we won't discuss his past crimes

An expression of real or pretended doubt or uncertainty especially for rhetorical effect

to be, or not to be: that is the question

Harshness in the sound of words or phrases

An inverted relationship between the syntactic elements of parallel phrases

working hard, or hardly working?

A disjunctive conclusion inferred from a single premise

gravitation may act without contact; therefore, either some force may act without contact or gravitation is not a force

The substitution of a disagreeable, offensive, or disparaging expression for an agreeable or inoffensive one

greasy spoon is a dysphemism for the word diner

Repetition of a word or expression at the end of successive phrases, clauses, sentences, or verses especially for rhetorical or poetic effect

of the people, by the people, for the people

Emphatic repetition [ this definition is taken from the 1934 edition of Webster's Unabridged dictionary ]

An interchange of two elements in a phrase or sentence from a more logical to a less logical relationship

you are lost to joy for joy is lost to you

A transposition or inversion of idiomatic word order

judge me by my size, do you?

Extravagant exaggeration

mile-high ice-cream cones

The putting or answering of an objection or argument against the speaker's contention [ this definition is taken from the 1934 edition of Webster's Unabridged dictionary ]

Understatement in which an affirmative is expressed by the negative of the contrary

not a bad singer

The presentation of a thing with underemphasis especially in order to achieve a greater effect : UNDERSTATEMENT

A figure of speech in which a word or phrase literally denoting one kind of object or idea is used in place of another to suggest a likeness or analogy between them ( Metaphor vs. Simile )

drowning in money

A figure of speech consisting of the use of the name of one thing for that of another of which it is an attribute or with which it is associated

crown as used in lands belonging to the crown

The naming of a thing or action by a vocal imitation of the sound associated with it

A combination of contradictory or incongruous words

cruel kindness

The use of more words than those necessary to denote mere sense : REDUNDANCY

I saw it with my own eyes

A figure of speech comparing two unlike things that is often introduced by "like" or "as"

cheeks like roses

The use of a word in the same grammatical relation to two adjacent words in the context with one literal and the other metaphorical in sense

she blew my nose and then she blew my mind

A figure of speech by which a part is put for the whole (such as fifty sail for fifty ships ), the whole for a part (such as society for high society ), the species for the genus (such as cutthroat for assassin ), the genus for the species (such as a creature for a man ), or the name of the material for the thing made (such as boards for stage )

The use of a word to modify or govern two or more words usually in such a manner that it applies to each in a different sense or makes sense with only one

opened the door and her heart to the homeless boy

MORE TO EXPLORE: Rhetorical Devices Used in Pop Songs

Word of the Day

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Games & Quizzes

Usage Notes

Prepositions, ending a sentence with, 33 transition words and phrases, is 'irregardless' a real word, 8 more grammar terms you used to know: special verb edition, point of view: it's personal, grammar & usage, more words you always have to look up, 'fewer' and 'less', 7 pairs of commonly confused words, more commonly misspelled words, your vs. you're: how to use them correctly, great big list of beautiful and useless words, vol. 4, 9 other words for beautiful, why jaywalking is called jaywalking, the words of the week - may 24, flower etymologies for your spring garden.

- Literary Terms

- Rhetorical Device

- Definition & Examples

- When & How to Write a Rhetorical Device

I. What is a Rhetorical Device?

A rhetorical device is any language that helps an author or speaker achieve a particular purpose (usually persuasion , since rhetoric is typically defined as the art of persuasion). But “rhetorical device” is an extremely broad term, and can include techniques for generating emotion, beauty, and spiritual significance as well as persuasion.

II. Examples of Rhetorical Devices

Hyperbole is a word- or sentence-level rhetorical device in which the author exaggerates a particular point for dramatic effect. For example:

Berlin was flattened during the bombing.

Because the city was not literally left flat, this is an exaggeration, and therefore hyperbole. But it still helps express the author’s main point, which is that the city of Berlin was very severely damaged.

Analogy is an important device in which the explains one thing by comparing it to another. At the sentence level, this might be as simple as saying “my cat’s fur is as white as a cloud .” But analogies can also function at much higher levels, including paragraphs and whole essays . For example, you might argue against war by drawing an extended analogy between the war on terrorism and World War 2. The success of the whole argument would depend entirely on how well you could persuade readers to accept the analogy!

The counterargument is the most important rhetorical device for college-level essays. A counterargument is a response to your own view – for example, if you’re arguing in favor of an idea, the counterargument is one that goes against that idea. In order to make your own argument perspective, you have to acknowledge, analyze, and answer these counterarguments.

III. Types of Rhetorical Devices

Because the term is so broad, there are countless ways to categorize rhetorical devices. For example, we might group them by function: e.g. persuasive devices, aesthetic devices (for creating beauty), or emotional devices. We could also group them according to the types of writing they belong to: e.g. poetry vs. essays.

The clearest way to categorize, though, is probably by scale: that is, what level of the writing does each device affect?

A. Word Level

Before we even get to full sentences, there are many rhetorical devices that operate at the level of individual words or groups of words. For example, the “metonym” is a rhetorical device in which a part stands in for the whole. For example, you might say that a ship is staffed with “twenty hands,” where each hand stands in for a full human being.

B. Sentence Level

Most rhetorical devices operate at the sentence level. They affect the meaning of a sentence, or a chunk of a sentence. For example, parallelism is an important rhetorical device in which different parts of a sentence have the same grammatical structure: “I am disgusted by your methods , but impressed with your results .” Notice how each underlined portion has the same pattern of adjective, preposition, pronoun, and plural noun.

C. Paragraph Level

Paragraph-level rhetorical techniques are especially important in essays, where they help to signal the structure of the argument. One example would be the topic sentence. Topic sentences open the paragraph and introduce its main idea, which is then supported and explained in the body of the paragraph. This is one of the most important techniques for structuring paragraphs effectively.

D. Structural Level

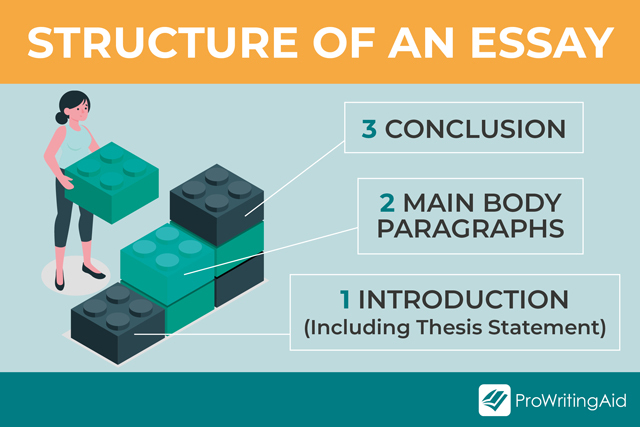

Some rhetorical devices cover the whole structure of a piece of writing. For example, the 5-paragraph essay is a rhetorical device that many people learn in high school for structuring their essays. The five paragraphs involve an introduction, 3 body paragraphs, and a conclusion. This structure is rejected by many college-level writing instructors (and thus may be thought of as a bad rhetorical device), but it’s a rhetorical device nonetheless.

IV. The Importance of Rhetorical Devices

Rhetorical devices are just like artistic techniques – they become popular because they work. For as long as human beings have been using language, we’ve been trying to persuade one another and evoke emotions. Over time, we’ve developed a huge variety of different techniques for achieving these effects, and the sum total of all such techniques is encapsulated in our modern lists of rhetorical techniques. Each rhetorical device has a different purpose, a different history, and a different effect!

V. Examples of Rhetorical Devices in Literature

“If we shadows have offended , think but this and all is mended : that you have but slumbered here while these visions did appear .” (Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night’s Dream )

This famous quote, like many of Shakespeare’s lines, employs rhyme and meter, the two most basic rhetorical devices in verse. Although not all poetry has rhyme or meter, most classical poems do, and these rhetorical devices were probably important in helping poets memorize their works and sing them in front of audiences.

The dialogue form is an important structural device used in philosophy and religious scriptures for thousands of years. By putting different arguments in the mouths of different characters , philosophers can present their readers with a broader range of possible views, thus bringing more nuance into the conversation. This device also allows philosophers to make their own arguments more persuasive by responding to the various counterarguments presented by characters in the dialogue.

VI. Examples of Rhetorical Devices in Popular Culture

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); “Ah, yes – Zorro! And where is he now, padre? Your masked friend? He hasn’t shown himself in 20 years!” (Don Rafael, The Mask of Zorro )

A rhetorical question is a question that the audience is not supposed to answer – either because the answer is obvious, or because the speaker is about to answer it for them. It’s one of the most common techniques in oratory (speeches) and essays. In this case, Don Rafael is using a rhetorical question to undermine the crowd’s confidence in Zorro, their legendary defender.

“The microphone explodes, || shattering the mold.” (Rage Against the Machine, Bulls on Parade )

The two vertical lines (||) represent a caesura , or pause. This is a common rhetorical device in poetry, but is also found in music. In the recording of the song, there’s a beat’s pause in between “explodes” and “shattering.”

VII. Related Terms

Rhetoric is the art of persuasion, either through speaking or writing. In ancient Greece, the concept of rhetoric was given huge cultural importance, and philosophers like Aristotle wrote whole books on rhetoric and the techniques of convincing others.

Today, people sometimes view rhetoric in a negative light (as when someone says of a politician’s speech that it was “all rhetoric and no substance”). But this is a shame, since we are very much in need of leaders who have mastered the art of persuasive reasoning and respectful argumentation. Rhetoric has fallen from its former place of honor, and perhaps this explains the lack of productive dialogue in our political arena, driven as it is by sound bites and personal attacks.

Figure of Speech

When a rhetorical device departs from literal truth, this is called a “figure of speech.” The most common figure of speech is a metaphor, in which one thing stands for another (e.g. “he unleashed a hurricane of criticism”). However, many rhetorical devices employ literal truth and therefore should not be thought of as figures of speech.

List of Terms

- Alliteration

- Amplification

- Anachronism

- Anthropomorphism

- Antonomasia

- APA Citation

- Aposiopesis

- Autobiography

- Bildungsroman

- Characterization

- Circumlocution

- Cliffhanger

- Comic Relief

- Connotation

- Deus ex machina

- Deuteragonist

- Doppelganger

- Double Entendre

- Dramatic irony

- Equivocation

- Extended Metaphor

- Figures of Speech

- Flash-forward

- Foreshadowing

- Intertextuality

- Juxtaposition

- Literary Device

- Malapropism

- Onomatopoeia

- Parallelism

- Pathetic Fallacy

- Personification

- Point of View

- Polysyndeton

- Protagonist

- Red Herring

- Rhetorical Question

- Science Fiction

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

- Synesthesia

- Turning Point

- Understatement

- Urban Legend

- Verisimilitude

- Essay Guide

- Cite This Website

9.5 Writing Process: Thinking Critically about Rhetoric

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Develop a rhetorical analysis through multiple drafts.

- Identify and analyze rhetorical strategies in a rhetorical analysis.

- Demonstrate flexible strategies for generating ideas, drafting, reviewing, collaborating, revising, rewriting, and editing.

- Give and act on productive feedback for works in progress.

The ability to think critically about rhetoric is a skill you will use in many of your classes, in your work, and in your life to gain insight from the way a text is written and organized. You will often be asked to explain or to express an opinion about what someone else has communicated and how that person has done so, especially if you take an active interest in politics and government. Like Eliana Evans in the previous section, you will develop similar analyses of written works to help others understand how a writer or speaker may be trying to reach them.

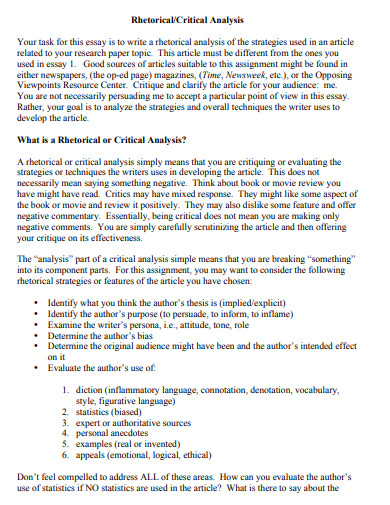

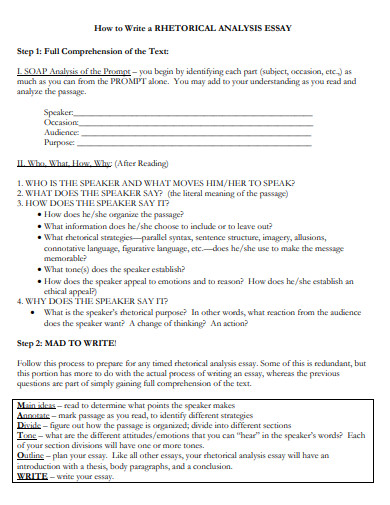

Summary of Assignment: Rhetorical Analysis

The assignment is to write a rhetorical analysis of a piece of persuasive writing. It can be an editorial, a movie or book review, an essay, a chapter in a book, or a letter to the editor. For your rhetorical analysis, you will need to consider the rhetorical situation—subject, author, purpose, context, audience, and culture—and the strategies the author uses in creating the argument. Back up all your claims with evidence from the text. In preparing your analysis, consider these questions:

- What is the subject? Be sure to distinguish what the piece is about.

- Who is the writer, and what do you know about them? Be sure you know whether the writer is considered objective or has a particular agenda.

- Who are the readers? What do you know or what can you find out about them as the particular audience to be addressed at this moment?

- What is the purpose or aim of this work? What does the author hope to achieve?

- What are the time/space/place considerations and influences of the writer? What can you know about the writer and the full context in which they are writing?

- What specific techniques has the writer used to make their points? Are these techniques successful, unsuccessful, or questionable?

For this assignment, read the following opinion piece by Octavio Peterson, printed in his local newspaper. You may choose it as the text you will analyze, continuing the analysis on your own, or you may refer to it as a sample as you work on another text of your choosing. Your instructor may suggest presidential or other political speeches, which make good subjects for rhetorical analysis.

When you have read the piece by Peterson advocating for the need to continue teaching foreign languages in schools, reflect carefully on the impact the letter has had on you. You are not expected to agree or disagree with it. Instead, focus on the rhetoric—the way Peterson uses language to make his point and convince you of the validity of his argument.

Another Lens. Consider presenting your rhetorical analysis in a multimodal format. Use a blogging site or platform such as WordPress or Tumblr to explore the blogging genre, which includes video clips, images, hyperlinks, and other media to further your discussion. Because this genre is less formal than written text, your tone can be conversational. However, you still will be required to provide the same kind of analysis that you would in a traditional essay. The same materials will be at your disposal for making appeals to persuade your readers. Rhetorical analysis in a blog may be a new forum for the exchange of ideas that retains the basics of more formal communication. When you have completed your work, share it with a small group or the rest of the class. See Multimodal and Online Writing: Creative Interaction between Text and Image for more about creating a multimodal composition.

Quick Launch: Start with a Thesis Statement

After you have read this opinion piece, or another of your choice, several times and have a clear understanding of it as a piece of rhetoric, consider whether the writer has succeeded in being persuasive. You might find that in some ways they have and in others they have not. Then, with a clear understanding of your purpose—to analyze how the writer seeks to persuade—you can start framing a thesis statement : a declarative sentence that states the topic, the angle you are taking, and the aspects of the topic the rest of the paper will support.

Complete the following sentence frames as you prepare to start:

- The subject of my rhetorical analysis is ________.

- My goal is to ________, not necessarily to ________.

- The writer’s main point is ________.

- I believe the writer has succeeded (or not) because ________.

- I believe the writer has succeeded in ________ (name the part or parts) but not in ________ (name the part or parts).

- The writer’s strongest (or weakest) point is ________, which they present by ________.

Drafting: Text Evidence and Analysis of Effect

As you begin to draft your rhetorical analysis, remember that you are giving your opinion on the author’s use of language. For example, Peterson has made a decision about the teaching of foreign languages, something readers of the newspaper might have different views on. In other words, there is room for debate and persuasion.

The context of the situation in which Peterson finds himself may well be more complex than he discusses. In the same way, the context of the piece you choose to analyze may also be more complex. For example, perhaps Greendale is facing an economic crisis and must pare its budget for educational spending and public works. It’s also possible that elected officials have made budget cuts for education a part of their platform or that school buildings have been found obsolete for safety measures. On the other hand, maybe a foreign company will come to town only if more Spanish speakers can be found locally. These factors would play a part in a real situation, and rhetoric would reflect that. If applicable, consider such possibilities regarding the subject of your analysis. Here, however, these factors are unknown and thus do not enter into the analysis.

Introduction

One effective way to begin a rhetorical analysis is by using an anecdote, as Eliana Evans has done. For a rhetorical analysis of the opinion piece, a writer might consider an anecdote about a person who was in a situation in which knowing another language was important or not important. If they begin with an anecdote, the next part of the introduction should contain the following information:

- Author’s name and position, or other qualification to establish ethos

- Title of work and genre

- Author’s thesis statement or stance taken (“Peterson argues that . . .”)

- Brief introductory explanation of how the author develops and supports the thesis or stance

- If relevant, a brief summary of context and culture

Once the context and situation for the analysis are clear, move directly to your thesis statement. In this case, your thesis statement will be your opinion of how successful the author has been in achieving the established goal through the use of rhetorical strategies. Read the sentences in Table 9.1 , and decide which would make the best thesis statement. Explain your reasoning in the right-hand column of this or a similar chart.

The introductory paragraph or paragraphs should serve to move the reader into the body of the analysis and signal what will follow.

Your next step is to start supporting your thesis statement—that is, how Octavio Peterson, or the writer of your choice, does or does not succeed in persuading readers. To accomplish this purpose, you need to look closely at the rhetorical strategies the writer uses.

First, list the rhetorical strategies you notice while reading the text, and note where they appear. Keep in mind that you do not need to include every strategy the text contains, only those essential ones that emphasize or support the central argument and those that may seem fallacious. You may add other strategies as well. The first example in Table 9.2 has been filled in.

When you have completed your list, consider how to structure your analysis. You will have to decide which of the writer’s statements are most effective. The strongest point would be a good place to begin; conversely, you could begin with the writer’s weakest point if that suits your purposes better. The most obvious organizational structure is one of the following:

- Go through the composition paragraph by paragraph and analyze its rhetorical content, focusing on the strategies that support the writer’s thesis statement.

- Address key rhetorical strategies individually, and show how the author has used them.

As you read the next few paragraphs, consult Table 9.3 for a visual plan of your rhetorical analysis. Your first body paragraph is the first of the analytical paragraphs. Here, too, you have options for organizing. You might begin by stating the writer’s strongest point. For example, you could emphasize that Peterson appeals to ethos by speaking personally to readers as fellow citizens and providing his credentials to establish credibility as someone trustworthy with their interests at heart.

Following this point, your next one can focus, for instance, on Peterson’s view that cutting foreign language instruction is a danger to the education of Greendale’s children. The points that follow support this argument, and you can track his rhetoric as he does so.

You may then use the second or third body paragraph, connected by a transition, to discuss Peterson’s appeal to logos. One possible transition might read, “To back up his assertion that omitting foreign languages is detrimental to education, Peterson provides examples and statistics.” Locate examples and quotes from the text as needed. You can discuss how, in citing these statistics, Peterson uses logos as a key rhetorical strategy.

In another paragraph, focus on other rhetorical elements, such as parallelism, repetition, and rhetorical questions. Moreover, be sure to indicate whether the writer acknowledges counterclaims and whether they are accepted or ultimately rejected.

The question of other factors at work in Greendale regarding finances, or similar factors in another setting, may be useful to mention here if they exist. As you continue, however, keep returning to your list of rhetorical strategies and explaining them. Even if some appear less important, they should be noted to show that you recognize how the writer is using language. You will likely have a minimum of four body paragraphs, but you may well have six or seven or even more, depending on the work you are analyzing.

In your final body paragraph, you might discuss the argument that Peterson, for example, has made by appealing to readers’ emotions. His calls for solidarity at the end of the letter provide a possible solution to his concern that the foreign language curriculum “might vanish like a puff of smoke.”

Use Table 9.3 to organize your rhetorical analysis. Be sure that each paragraph has a topic sentence and that you use transitions to flow smoothly from one idea to the next.

As you conclude your essay, your own logic in discussing the writer’s argument will make it clear whether you have found their claims convincing. Your opinion, as framed in your conclusion, may restate your thesis statement in different words, or you may choose to reveal your thesis at this point. The real function of the conclusion is to confirm your evaluation and show that you understand the use of the language and the effectiveness of the argument.

In your analysis, note that objections could be raised because Peterson, for example, speaks only for himself. You may speculate about whether the next edition of the newspaper will feature an opposing opinion piece from someone who disagrees. However, it is not necessary to provide answers to questions you raise here. Your conclusion should summarize briefly how the writer has made, or failed to make, a forceful argument that may require further debate.

For more guidance on writing a rhetorical analysis, visit the Illinois Writers Workshop website or watch this tutorial .

Peer Review: Guidelines toward Revision and the “Golden Rule”

Now that you have a working draft, your next step is to engage in peer review, an important part of the writing process. Often, others can identify things you have missed or can ask you to clarify statements that may be clear to you but not to others. For your peer review, follow these steps and make use of Table 9.4 .

- Quickly skim through your peer’s rhetorical analysis draft once, and then ask yourself, What is the main point or argument of my peer’s work?

- Highlight, underline, or otherwise make note of statements or instances in the paper where you think your peer has made their main point.

- Look at the draft again, this time reading it closely.

- Ask yourself the following questions, and comment on the peer review sheet as shown.

The Golden Rule

An important part of the peer review process is to keep in mind the familiar wisdom of the “Golden Rule”: treat others as you would have them treat you. This foundational approach to human relations extends to commenting on others’ work. Like your peers, you are in the same situation of needing opinion and guidance. Whatever you have written will seem satisfactory or better to you because you have written it and know what you mean to say.

However, your peers have the advantage of distance from the work you have written and can see it through their own eyes. Likewise, if you approach your peer’s work fairly and free of personal bias, you’re likely to be more constructive in finding parts of their writing that need revision. Most important, though, is to make suggestions tactfully and considerately, in the spirit of helping, not degrading someone’s work. You and your peers may be reluctant to share your work, but if everyone approaches the review process with these ideas in mind, everyone will benefit from the opportunity to provide and act on sincerely offered suggestions.

Revising: Staying Open to Feedback and Working with It

Once the peer review process is complete, your next step is to revise the first draft by incorporating suggestions and making changes on your own. Consider some of these potential issues when incorporating peers’ revisions and rethinking your own work.

- Too much summarizing rather than analyzing

- Too much informal language or an unintentional mix of casual and formal language

- Too few, too many, or inappropriate transitions

- Illogical or unclear sequence of information

- Insufficient evidence to support main ideas effectively

- Too many generalities rather than specific facts, maybe from trying to do too much in too little time

In any case, revising a draft is a necessary step to produce a final work. Rarely will even a professional writer arrive at the best point in a single draft. In other words, it’s seldom a problem if your first draft needs refocusing. However, it may become a problem if you don’t address it. The best way to shape a wandering piece of writing is to return to it, reread it, slow it down, take it apart, and build it back up again. Approach first-draft writing for what it is: a warm-up or rehearsal for a final performance.

Suggestions for Revising

When revising, be sure your thesis statement is clear and fulfills your purpose. Verify that you have abundant supporting evidence and that details are consistently on topic and relevant to your position. Just before arriving at the conclusion, be sure you have prepared a logical ending. The concluding statement should be strong and should not present any new points. Rather, it should grow out of what has already been said and return, in some degree, to the thesis statement. In the example of Octavio Peterson, his purpose was to persuade readers that teaching foreign languages in schools in Greendale should continue; therefore, the conclusion can confirm that Peterson achieved, did not achieve, or partially achieved his aim.

When revising, make sure the larger elements of the piece are as you want them to be before you revise individual sentences and make smaller changes. If you make small changes first, they might not fit well with the big picture later on.

One approach to big-picture revising is to check the organization as you move from paragraph to paragraph. You can list each paragraph and check that its content relates to the purpose and thesis statement. Each paragraph should have one main point and be self-contained in showing how the rhetorical devices used in the text strengthen (or fail to strengthen) the argument and the writer’s ability to persuade. Be sure your paragraphs flow logically from one to the other without distracting gaps or inconsistencies.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Authors: Michelle Bachelor Robinson, Maria Jerskey, featuring Toby Fulwiler

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Writing Guide with Handbook

- Publication date: Dec 21, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/9-5-writing-process-thinking-critically-about-rhetoric

© Dec 19, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

What Is a Rhetorical Analysis and How to Write a Great One

Helly Douglas

Do you have to write a rhetorical analysis essay? Fear not! We’re here to explain exactly what rhetorical analysis means, how you should structure your essay, and give you some essential “dos and don’ts.”

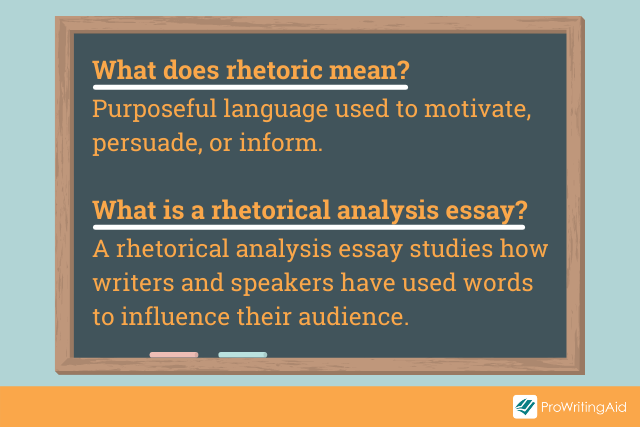

What is a Rhetorical Analysis Essay?

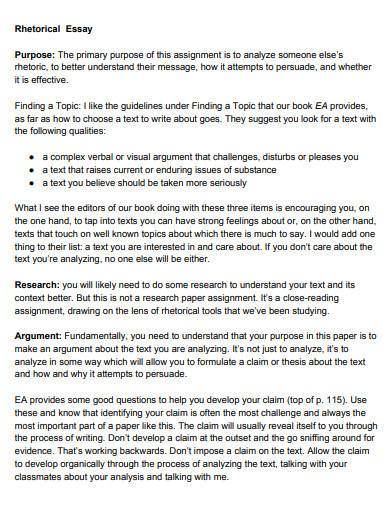

How do you write a rhetorical analysis, what are the three rhetorical strategies, what are the five rhetorical situations, how to plan a rhetorical analysis essay, creating a rhetorical analysis essay, examples of great rhetorical analysis essays, final thoughts.

A rhetorical analysis essay studies how writers and speakers have used words to influence their audience. Think less about the words the author has used and more about the techniques they employ, their goals, and the effect this has on the audience.

In your analysis essay, you break a piece of text (including cartoons, adverts, and speeches) into sections and explain how each part works to persuade, inform, or entertain. You’ll explore the effectiveness of the techniques used, how the argument has been constructed, and give examples from the text.

A strong rhetorical analysis evaluates a text rather than just describes the techniques used. You don’t include whether you personally agree or disagree with the argument.

Structure a rhetorical analysis in the same way as most other types of academic essays . You’ll have an introduction to present your thesis, a main body where you analyze the text, which then leads to a conclusion.

Think about how the writer (also known as a rhetor) considers the situation that frames their communication:

- Topic: the overall purpose of the rhetoric

- Audience: this includes primary, secondary, and tertiary audiences

- Purpose: there are often more than one to consider

- Context and culture: the wider situation within which the rhetoric is placed

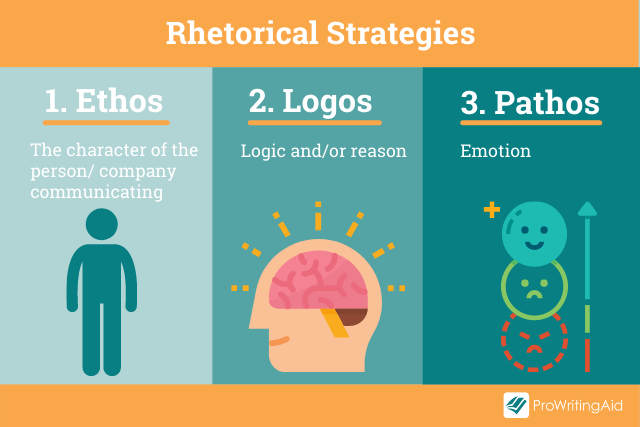

Back in the 4th century BC, Aristotle was talking about how language can be used as a means of persuasion. He described three principal forms —Ethos, Logos, and Pathos—often referred to as the Rhetorical Triangle . These persuasive techniques are still used today.

Rhetorical Strategy 1: Ethos

Are you more likely to buy a car from an established company that’s been an important part of your community for 50 years, or someone new who just started their business?

Reputation matters. Ethos explores how the character, disposition, and fundamental values of the author create appeal, along with their expertise and knowledge in the subject area.

Aristotle breaks ethos down into three further categories:

- Phronesis: skills and practical wisdom

- Arete: virtue

- Eunoia: goodwill towards the audience

Ethos-driven speeches and text rely on the reputation of the author. In your analysis, you can look at how the writer establishes ethos through both direct and indirect means.

Rhetorical Strategy 2: Pathos

Pathos-driven rhetoric hooks into our emotions. You’ll often see it used in advertisements, particularly by charities wanting you to donate money towards an appeal.

Common use of pathos includes:

- Vivid description so the reader can imagine themselves in the situation

- Personal stories to create feelings of empathy

- Emotional vocabulary that evokes a response

By using pathos to make the audience feel a particular emotion, the author can persuade them that the argument they’re making is compelling.

Rhetorical Strategy 3: Logos

Logos uses logic or reason. It’s commonly used in academic writing when arguments are created using evidence and reasoning rather than an emotional response. It’s constructed in a step-by-step approach that builds methodically to create a powerful effect upon the reader.

Rhetoric can use any one of these three techniques, but effective arguments often appeal to all three elements.

The rhetorical situation explains the circumstances behind and around a piece of rhetoric. It helps you think about why a text exists, its purpose, and how it’s carried out.

The rhetorical situations are:

- 1) Purpose: Why is this being written? (It could be trying to inform, persuade, instruct, or entertain.)

- 2) Audience: Which groups or individuals will read and take action (or have done so in the past)?

- 3) Genre: What type of writing is this?

- 4) Stance: What is the tone of the text? What position are they taking?

- 5) Media/Visuals: What means of communication are used?

Understanding and analyzing the rhetorical situation is essential for building a strong essay. Also think about any rhetoric restraints on the text, such as beliefs, attitudes, and traditions that could affect the author's decisions.

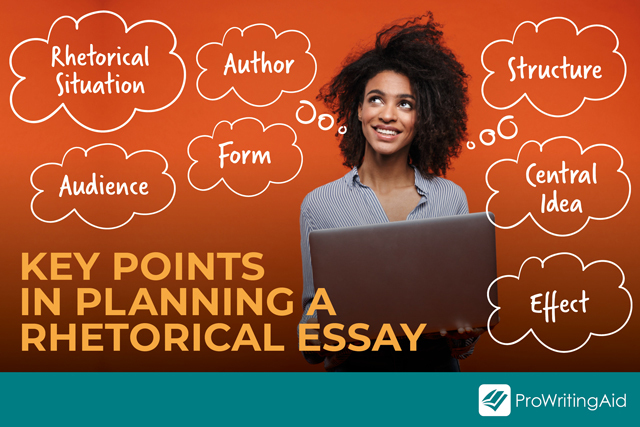

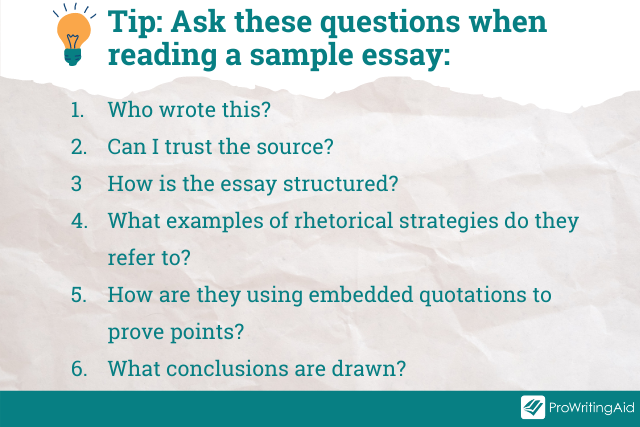

Before leaping into your essay, it’s worth taking time to explore the text at a deeper level and considering the rhetorical situations we looked at before. Throw away your assumptions and use these simple questions to help you unpick how and why the text is having an effect on the audience.

1: What is the Rhetorical Situation?

- Why is there a need or opportunity for persuasion?

- How do words and references help you identify the time and location?

- What are the rhetoric restraints?

- What historical occasions would lead to this text being created?

2: Who is the Author?

- How do they position themselves as an expert worth listening to?

- What is their ethos?

- Do they have a reputation that gives them authority?

- What is their intention?

- What values or customs do they have?

3: Who is it Written For?

- Who is the intended audience?

- How is this appealing to this particular audience?

- Who are the possible secondary and tertiary audiences?

4: What is the Central Idea?

- Can you summarize the key point of this rhetoric?

- What arguments are used?

- How has it developed a line of reasoning?

5: How is it Structured?

- What structure is used?

- How is the content arranged within the structure?

6: What Form is Used?

- Does this follow a specific literary genre?

- What type of style and tone is used, and why is this?

- Does the form used complement the content?

- What effect could this form have on the audience?

7: Is the Rhetoric Effective?

- Does the content fulfil the author’s intentions?

- Does the message effectively fit the audience, location, and time period?

Once you’ve fully explored the text, you’ll have a better understanding of the impact it’s having on the audience and feel more confident about writing your essay outline.

A great essay starts with an interesting topic. Choose carefully so you’re personally invested in the subject and familiar with it rather than just following trending topics. There are lots of great ideas on this blog post by My Perfect Words if you need some inspiration. Take some time to do background research to ensure your topic offers good analysis opportunities.

Remember to check the information given to you by your professor so you follow their preferred style guidelines. This outline example gives you a general idea of a format to follow, but there will likely be specific requests about layout and content in your course handbook. It’s always worth asking your institution if you’re unsure.

Make notes for each section of your essay before you write. This makes it easy for you to write a well-structured text that flows naturally to a conclusion. You will develop each note into a paragraph. Look at this example by College Essay for useful ideas about the structure.

1: Introduction

This is a short, informative section that shows you understand the purpose of the text. It tempts the reader to find out more by mentioning what will come in the main body of your essay.

- Name the author of the text and the title of their work followed by the date in parentheses

- Use a verb to describe what the author does, e.g. “implies,” “asserts,” or “claims”

- Briefly summarize the text in your own words

- Mention the persuasive techniques used by the rhetor and its effect

Create a thesis statement to come at the end of your introduction.