Literature Review: Types of literature reviews

- Traditional or narrative literature reviews

- Scoping Reviews

- Systematic literature reviews

- Annotated bibliography

- Keeping up to date with literature

- Finding a thesis

- Evaluating sources and critical appraisal of literature

- Managing and analysing your literature

- Further reading and resources

Types of literature reviews

The type of literature review you write will depend on your discipline and whether you are a researcher writing your PhD, publishing a study in a journal or completing an assessment task in your undergraduate study.

A literature review for a subject in an undergraduate degree will not be as comprehensive as the literature review required for a PhD thesis.

An undergraduate literature review may be in the form of an annotated bibliography or a narrative review of a small selection of literature, for example ten relevant articles. If you are asked to write a literature review, and you are an undergraduate student, be guided by your subject coordinator or lecturer.

The common types of literature reviews will be explained in the pages of this section.

- Narrative or traditional literature reviews

- Critically Appraised Topic (CAT)

- Scoping reviews

- Annotated bibliographies

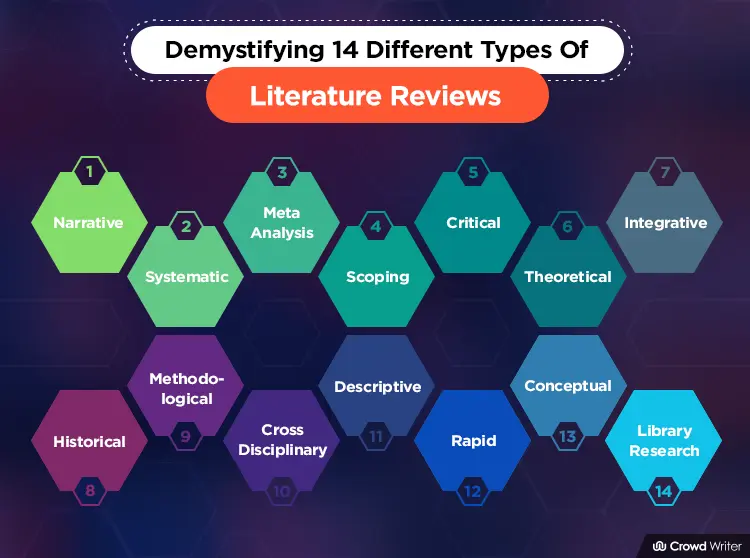

These are not the only types of reviews of literature that can be conducted. Often the term "review" and "literature" can be confusing and used in the wrong context. Grant and Booth (2009) attempt to clear up this confusion by discussing 14 review types and the associated methodology, and advantages and disadvantages associated with each review.

Grant, M. J. and Booth, A. (2009), A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies . Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26 , 91–108. doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

What's the difference between reviews?

Researchers, academics, and librarians all use various terms to describe different types of literature reviews, and there is often inconsistency in the ways the types are discussed. Here are a couple of simple explanations.

- The image below describes common review types in terms of speed, detail, risk of bias, and comprehensiveness:

"Schematic of the main differences between the types of literature review" by Brennan, M. L., Arlt, S. P., Belshaw, Z., Buckley, L., Corah, L., Doit, H., Fajt, V. R., Grindlay, D., Moberly, H. K., Morrow, L. D., Stavisky, J., & White, C. (2020). Critically Appraised Topics (CATs) in veterinary medicine: Applying evidence in clinical practice. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 7 , 314. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2020.00314 is licensed under CC BY 3.0

- The table below lists four of the most common types of review , as adapted from a widely used typology of fourteen types of reviews (Grant & Booth, 2009).

Grant, M.J. & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26 (2), 91-108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

See also the Library's Literature Review guide.

Critical Appraised Topic (CAT)

For information on conducting a Critically Appraised Topic or CAT

Callander, J., Anstey, A. V., Ingram, J. R., Limpens, J., Flohr, C., & Spuls, P. I. (2017). How to write a Critically Appraised Topic: evidence to underpin routine clinical practice. British Journal of Dermatology (1951), 177(4), 1007-1013. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.15873

Books on Literature Reviews

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Traditional or narrative literature reviews >>

- Last Updated: May 12, 2024 12:18 PM

- URL: https://libguides.csu.edu.au/review

Charles Sturt University is an Australian University, TEQSA Provider Identification: PRV12018. CRICOS Provider: 00005F.

- UConn Library

- Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide

- Introduction

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide — Introduction

- Getting Started

- How to Pick a Topic

- Strategies to Find Sources

- Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

What are Literature Reviews?

So, what is a literature review? "A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries." Taylor, D. The literature review: A few tips on conducting it . University of Toronto Health Sciences Writing Centre.

Goals of Literature Reviews

What are the goals of creating a Literature Review? A literature could be written to accomplish different aims:

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1997). Writing narrative literature reviews . Review of General Psychology , 1 (3), 311-320.

What kinds of sources require a Literature Review?

- A research paper assigned in a course

- A thesis or dissertation

- A grant proposal

- An article intended for publication in a journal

All these instances require you to collect what has been written about your research topic so that you can demonstrate how your own research sheds new light on the topic.

Types of Literature Reviews

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

Narrative review: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific topic/research and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weakness, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section which summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Example : Predictors and Outcomes of U.S. Quality Maternity Leave: A Review and Conceptual Framework: 10.1177/08948453211037398

Systematic review : "The authors of a systematic review use a specific procedure to search the research literature, select the studies to include in their review, and critically evaluate the studies they find." (p. 139). Nelson, L. K. (2013). Research in Communication Sciences and Disorders . Plural Publishing.

- Example : The effect of leave policies on increasing fertility: a systematic review: 10.1057/s41599-022-01270-w

Meta-analysis : "Meta-analysis is a method of reviewing research findings in a quantitative fashion by transforming the data from individual studies into what is called an effect size and then pooling and analyzing this information. The basic goal in meta-analysis is to explain why different outcomes have occurred in different studies." (p. 197). Roberts, M. C., & Ilardi, S. S. (2003). Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology . Blackwell Publishing.

- Example : Employment Instability and Fertility in Europe: A Meta-Analysis: 10.1215/00703370-9164737

Meta-synthesis : "Qualitative meta-synthesis is a type of qualitative study that uses as data the findings from other qualitative studies linked by the same or related topic." (p.312). Zimmer, L. (2006). Qualitative meta-synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 53 (3), 311-318.

- Example : Women’s perspectives on career successes and barriers: A qualitative meta-synthesis: 10.1177/05390184221113735

Literature Reviews in the Health Sciences

- UConn Health subject guide on systematic reviews Explanation of the different review types used in health sciences literature as well as tools to help you find the right review type

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: How to Pick a Topic >>

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2022 2:16 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/literaturereview

Literature Reviews

- Getting started

What is a literature review?

Why conduct a literature review, stages of a literature review, lit reviews: an overview (video), check out these books.

- Types of reviews

- 1. Define your research question

- 2. Plan your search

- 3. Search the literature

- 4. Organize your results

- 5. Synthesize your findings

- 6. Write the review

- Artificial intelligence (AI) tools

- Thompson Writing Studio This link opens in a new window

- Need to write a systematic review? This link opens in a new window

Contact a Librarian

Ask a Librarian

Definition: A literature review is a systematic examination and synthesis of existing scholarly research on a specific topic or subject.

Purpose: It serves to provide a comprehensive overview of the current state of knowledge within a particular field.

Analysis: Involves critically evaluating and summarizing key findings, methodologies, and debates found in academic literature.

Identifying Gaps: Aims to pinpoint areas where there is a lack of research or unresolved questions, highlighting opportunities for further investigation.

Contextualization: Enables researchers to understand how their work fits into the broader academic conversation and contributes to the existing body of knowledge.

tl;dr A literature review critically examines and synthesizes existing scholarly research and publications on a specific topic to provide a comprehensive understanding of the current state of knowledge in the field.

What is a literature review NOT?

❌ An annotated bibliography

❌ Original research

❌ A summary

❌ Something to be conducted at the end of your research

❌ An opinion piece

❌ A chronological compilation of studies

The reason for conducting a literature review is to:

Literature Reviews: An Overview for Graduate Students

While this 9-minute video from NCSU is geared toward graduate students, it is useful for anyone conducting a literature review.

Writing the literature review: A practical guide

Available 3rd floor of Perkins

Writing literature reviews: A guide for students of the social and behavioral sciences

Available online!

So, you have to write a literature review: A guided workbook for engineers

Telling a research story: Writing a literature review

The literature review: Six steps to success

Systematic approaches to a successful literature review

Request from Duke Medical Center Library

Doing a systematic review: A student's guide

- Next: Types of reviews >>

- Last Updated: May 17, 2024 8:42 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.duke.edu/litreviews

Services for...

- Faculty & Instructors

- Graduate Students

- Undergraduate Students

- International Students

- Patrons with Disabilities

- Harmful Language Statement

- Re-use & Attribution / Privacy

- Support the Libraries

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 5. The Literature Review

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

A literature review surveys prior research published in books, scholarly articles, and any other sources relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory, and by so doing, provides a description, summary, and critical evaluation of these works in relation to the research problem being investigated. Literature reviews are designed to provide an overview of sources you have used in researching a particular topic and to demonstrate to your readers how your research fits within existing scholarship about the topic.

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . Fourth edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2014.

Importance of a Good Literature Review

A literature review may consist of simply a summary of key sources, but in the social sciences, a literature review usually has an organizational pattern and combines both summary and synthesis, often within specific conceptual categories . A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information in a way that informs how you are planning to investigate a research problem. The analytical features of a literature review might:

- Give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations,

- Trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates,

- Depending on the situation, evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant research, or

- Usually in the conclusion of a literature review, identify where gaps exist in how a problem has been researched to date.

Given this, the purpose of a literature review is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to understanding the research problem being studied.

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies.

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important].

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Jesson, Jill. Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2011; Knopf, Jeffrey W. "Doing a Literature Review." PS: Political Science and Politics 39 (January 2006): 127-132; Ridley, Diana. The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students . 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2012.

Types of Literature Reviews

It is important to think of knowledge in a given field as consisting of three layers. First, there are the primary studies that researchers conduct and publish. Second are the reviews of those studies that summarize and offer new interpretations built from and often extending beyond the primary studies. Third, there are the perceptions, conclusions, opinion, and interpretations that are shared informally among scholars that become part of the body of epistemological traditions within the field.

In composing a literature review, it is important to note that it is often this third layer of knowledge that is cited as "true" even though it often has only a loose relationship to the primary studies and secondary literature reviews. Given this, while literature reviews are designed to provide an overview and synthesis of pertinent sources you have explored, there are a number of approaches you could adopt depending upon the type of analysis underpinning your study.

Argumentative Review This form examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply embedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. The purpose is to develop a body of literature that establishes a contrarian viewpoint. Given the value-laden nature of some social science research [e.g., educational reform; immigration control], argumentative approaches to analyzing the literature can be a legitimate and important form of discourse. However, note that they can also introduce problems of bias when they are used to make summary claims of the sort found in systematic reviews [see below].

Integrative Review Considered a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. The body of literature includes all studies that address related or identical hypotheses or research problems. A well-done integrative review meets the same standards as primary research in regard to clarity, rigor, and replication. This is the most common form of review in the social sciences.

Historical Review Few things rest in isolation from historical precedent. Historical literature reviews focus on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomena emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.

Methodological Review A review does not always focus on what someone said [findings], but how they came about saying what they say [method of analysis]. Reviewing methods of analysis provides a framework of understanding at different levels [i.e. those of theory, substantive fields, research approaches, and data collection and analysis techniques], how researchers draw upon a wide variety of knowledge ranging from the conceptual level to practical documents for use in fieldwork in the areas of ontological and epistemological consideration, quantitative and qualitative integration, sampling, interviewing, data collection, and data analysis. This approach helps highlight ethical issues which you should be aware of and consider as you go through your own study.

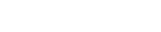

Systematic Review This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect, report, and analyze data from the studies that are included in the review. The goal is to deliberately document, critically evaluate, and summarize scientifically all of the research about a clearly defined research problem . Typically it focuses on a very specific empirical question, often posed in a cause-and-effect form, such as "To what extent does A contribute to B?" This type of literature review is primarily applied to examining prior research studies in clinical medicine and allied health fields, but it is increasingly being used in the social sciences.

Theoretical Review The purpose of this form is to examine the corpus of theory that has accumulated in regard to an issue, concept, theory, phenomena. The theoretical literature review helps to establish what theories already exist, the relationships between them, to what degree the existing theories have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested. Often this form is used to help establish a lack of appropriate theories or reveal that current theories are inadequate for explaining new or emerging research problems. The unit of analysis can focus on a theoretical concept or a whole theory or framework.

NOTE : Most often the literature review will incorporate some combination of types. For example, a review that examines literature supporting or refuting an argument, assumption, or philosophical problem related to the research problem will also need to include writing supported by sources that establish the history of these arguments in the literature.

Baumeister, Roy F. and Mark R. Leary. "Writing Narrative Literature Reviews." Review of General Psychology 1 (September 1997): 311-320; Mark R. Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Kennedy, Mary M. "Defining a Literature." Educational Researcher 36 (April 2007): 139-147; Petticrew, Mark and Helen Roberts. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide . Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 2006; Torracro, Richard. "Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples." Human Resource Development Review 4 (September 2005): 356-367; Rocco, Tonette S. and Maria S. Plakhotnik. "Literature Reviews, Conceptual Frameworks, and Theoretical Frameworks: Terms, Functions, and Distinctions." Human Ressource Development Review 8 (March 2008): 120-130; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Thinking About Your Literature Review

The structure of a literature review should include the following in support of understanding the research problem :

- An overview of the subject, issue, or theory under consideration, along with the objectives of the literature review,

- Division of works under review into themes or categories [e.g. works that support a particular position, those against, and those offering alternative approaches entirely],

- An explanation of how each work is similar to and how it varies from the others,

- Conclusions as to which pieces are best considered in their argument, are most convincing of their opinions, and make the greatest contribution to the understanding and development of their area of research.

The critical evaluation of each work should consider :

- Provenance -- what are the author's credentials? Are the author's arguments supported by evidence [e.g. primary historical material, case studies, narratives, statistics, recent scientific findings]?

- Methodology -- were the techniques used to identify, gather, and analyze the data appropriate to addressing the research problem? Was the sample size appropriate? Were the results effectively interpreted and reported?

- Objectivity -- is the author's perspective even-handed or prejudicial? Is contrary data considered or is certain pertinent information ignored to prove the author's point?

- Persuasiveness -- which of the author's theses are most convincing or least convincing?

- Validity -- are the author's arguments and conclusions convincing? Does the work ultimately contribute in any significant way to an understanding of the subject?

II. Development of the Literature Review

Four Basic Stages of Writing 1. Problem formulation -- which topic or field is being examined and what are its component issues? 2. Literature search -- finding materials relevant to the subject being explored. 3. Data evaluation -- determining which literature makes a significant contribution to the understanding of the topic. 4. Analysis and interpretation -- discussing the findings and conclusions of pertinent literature.

Consider the following issues before writing the literature review: Clarify If your assignment is not specific about what form your literature review should take, seek clarification from your professor by asking these questions: 1. Roughly how many sources would be appropriate to include? 2. What types of sources should I review (books, journal articles, websites; scholarly versus popular sources)? 3. Should I summarize, synthesize, or critique sources by discussing a common theme or issue? 4. Should I evaluate the sources in any way beyond evaluating how they relate to understanding the research problem? 5. Should I provide subheadings and other background information, such as definitions and/or a history? Find Models Use the exercise of reviewing the literature to examine how authors in your discipline or area of interest have composed their literature review sections. Read them to get a sense of the types of themes you might want to look for in your own research or to identify ways to organize your final review. The bibliography or reference section of sources you've already read, such as required readings in the course syllabus, are also excellent entry points into your own research. Narrow the Topic The narrower your topic, the easier it will be to limit the number of sources you need to read in order to obtain a good survey of relevant resources. Your professor will probably not expect you to read everything that's available about the topic, but you'll make the act of reviewing easier if you first limit scope of the research problem. A good strategy is to begin by searching the USC Libraries Catalog for recent books about the topic and review the table of contents for chapters that focuses on specific issues. You can also review the indexes of books to find references to specific issues that can serve as the focus of your research. For example, a book surveying the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict may include a chapter on the role Egypt has played in mediating the conflict, or look in the index for the pages where Egypt is mentioned in the text. Consider Whether Your Sources are Current Some disciplines require that you use information that is as current as possible. This is particularly true in disciplines in medicine and the sciences where research conducted becomes obsolete very quickly as new discoveries are made. However, when writing a review in the social sciences, a survey of the history of the literature may be required. In other words, a complete understanding the research problem requires you to deliberately examine how knowledge and perspectives have changed over time. Sort through other current bibliographies or literature reviews in the field to get a sense of what your discipline expects. You can also use this method to explore what is considered by scholars to be a "hot topic" and what is not.

III. Ways to Organize Your Literature Review

Chronology of Events If your review follows the chronological method, you could write about the materials according to when they were published. This approach should only be followed if a clear path of research building on previous research can be identified and that these trends follow a clear chronological order of development. For example, a literature review that focuses on continuing research about the emergence of German economic power after the fall of the Soviet Union. By Publication Order your sources by publication chronology, then, only if the order demonstrates a more important trend. For instance, you could order a review of literature on environmental studies of brown fields if the progression revealed, for example, a change in the soil collection practices of the researchers who wrote and/or conducted the studies. Thematic [“conceptual categories”] A thematic literature review is the most common approach to summarizing prior research in the social and behavioral sciences. Thematic reviews are organized around a topic or issue, rather than the progression of time, although the progression of time may still be incorporated into a thematic review. For example, a review of the Internet’s impact on American presidential politics could focus on the development of online political satire. While the study focuses on one topic, the Internet’s impact on American presidential politics, it would still be organized chronologically reflecting technological developments in media. The difference in this example between a "chronological" and a "thematic" approach is what is emphasized the most: themes related to the role of the Internet in presidential politics. Note that more authentic thematic reviews tend to break away from chronological order. A review organized in this manner would shift between time periods within each section according to the point being made. Methodological A methodological approach focuses on the methods utilized by the researcher. For the Internet in American presidential politics project, one methodological approach would be to look at cultural differences between the portrayal of American presidents on American, British, and French websites. Or the review might focus on the fundraising impact of the Internet on a particular political party. A methodological scope will influence either the types of documents in the review or the way in which these documents are discussed.

Other Sections of Your Literature Review Once you've decided on the organizational method for your literature review, the sections you need to include in the paper should be easy to figure out because they arise from your organizational strategy. In other words, a chronological review would have subsections for each vital time period; a thematic review would have subtopics based upon factors that relate to the theme or issue. However, sometimes you may need to add additional sections that are necessary for your study, but do not fit in the organizational strategy of the body. What other sections you include in the body is up to you. However, only include what is necessary for the reader to locate your study within the larger scholarship about the research problem.

Here are examples of other sections, usually in the form of a single paragraph, you may need to include depending on the type of review you write:

- Current Situation : Information necessary to understand the current topic or focus of the literature review.

- Sources Used : Describes the methods and resources [e.g., databases] you used to identify the literature you reviewed.

- History : The chronological progression of the field, the research literature, or an idea that is necessary to understand the literature review, if the body of the literature review is not already a chronology.

- Selection Methods : Criteria you used to select (and perhaps exclude) sources in your literature review. For instance, you might explain that your review includes only peer-reviewed [i.e., scholarly] sources.

- Standards : Description of the way in which you present your information.

- Questions for Further Research : What questions about the field has the review sparked? How will you further your research as a result of the review?

IV. Writing Your Literature Review

Once you've settled on how to organize your literature review, you're ready to write each section. When writing your review, keep in mind these issues.

Use Evidence A literature review section is, in this sense, just like any other academic research paper. Your interpretation of the available sources must be backed up with evidence [citations] that demonstrates that what you are saying is valid. Be Selective Select only the most important points in each source to highlight in the review. The type of information you choose to mention should relate directly to the research problem, whether it is thematic, methodological, or chronological. Related items that provide additional information, but that are not key to understanding the research problem, can be included in a list of further readings . Use Quotes Sparingly Some short quotes are appropriate if you want to emphasize a point, or if what an author stated cannot be easily paraphrased. Sometimes you may need to quote certain terminology that was coined by the author, is not common knowledge, or taken directly from the study. Do not use extensive quotes as a substitute for using your own words in reviewing the literature. Summarize and Synthesize Remember to summarize and synthesize your sources within each thematic paragraph as well as throughout the review. Recapitulate important features of a research study, but then synthesize it by rephrasing the study's significance and relating it to your own work and the work of others. Keep Your Own Voice While the literature review presents others' ideas, your voice [the writer's] should remain front and center. For example, weave references to other sources into what you are writing but maintain your own voice by starting and ending the paragraph with your own ideas and wording. Use Caution When Paraphrasing When paraphrasing a source that is not your own, be sure to represent the author's information or opinions accurately and in your own words. Even when paraphrasing an author’s work, you still must provide a citation to that work.

V. Common Mistakes to Avoid

These are the most common mistakes made in reviewing social science research literature.

- Sources in your literature review do not clearly relate to the research problem;

- You do not take sufficient time to define and identify the most relevant sources to use in the literature review related to the research problem;

- Relies exclusively on secondary analytical sources rather than including relevant primary research studies or data;

- Uncritically accepts another researcher's findings and interpretations as valid, rather than examining critically all aspects of the research design and analysis;

- Does not describe the search procedures that were used in identifying the literature to review;

- Reports isolated statistical results rather than synthesizing them in chi-squared or meta-analytic methods; and,

- Only includes research that validates assumptions and does not consider contrary findings and alternative interpretations found in the literature.

Cook, Kathleen E. and Elise Murowchick. “Do Literature Review Skills Transfer from One Course to Another?” Psychology Learning and Teaching 13 (March 2014): 3-11; Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Jesson, Jill. Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques . London: SAGE, 2011; Literature Review Handout. Online Writing Center. Liberty University; Literature Reviews. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J. and Rebecca Frels. Seven Steps to a Comprehensive Literature Review: A Multimodal and Cultural Approach . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2016; Ridley, Diana. The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students . 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2012; Randolph, Justus J. “A Guide to Writing the Dissertation Literature Review." Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation. vol. 14, June 2009; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016; Taylor, Dena. The Literature Review: A Few Tips On Conducting It. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Writing a Literature Review. Academic Skills Centre. University of Canberra.

Writing Tip

Break Out of Your Disciplinary Box!

Thinking interdisciplinarily about a research problem can be a rewarding exercise in applying new ideas, theories, or concepts to an old problem. For example, what might cultural anthropologists say about the continuing conflict in the Middle East? In what ways might geographers view the need for better distribution of social service agencies in large cities than how social workers might study the issue? You don’t want to substitute a thorough review of core research literature in your discipline for studies conducted in other fields of study. However, particularly in the social sciences, thinking about research problems from multiple vectors is a key strategy for finding new solutions to a problem or gaining a new perspective. Consult with a librarian about identifying research databases in other disciplines; almost every field of study has at least one comprehensive database devoted to indexing its research literature.

Frodeman, Robert. The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity . New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Another Writing Tip

Don't Just Review for Content!

While conducting a review of the literature, maximize the time you devote to writing this part of your paper by thinking broadly about what you should be looking for and evaluating. Review not just what scholars are saying, but how are they saying it. Some questions to ask:

- How are they organizing their ideas?

- What methods have they used to study the problem?

- What theories have been used to explain, predict, or understand their research problem?

- What sources have they cited to support their conclusions?

- How have they used non-textual elements [e.g., charts, graphs, figures, etc.] to illustrate key points?

When you begin to write your literature review section, you'll be glad you dug deeper into how the research was designed and constructed because it establishes a means for developing more substantial analysis and interpretation of the research problem.

Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1 998.

Yet Another Writing Tip

When Do I Know I Can Stop Looking and Move On?

Here are several strategies you can utilize to assess whether you've thoroughly reviewed the literature:

- Look for repeating patterns in the research findings . If the same thing is being said, just by different people, then this likely demonstrates that the research problem has hit a conceptual dead end. At this point consider: Does your study extend current research? Does it forge a new path? Or, does is merely add more of the same thing being said?

- Look at sources the authors cite to in their work . If you begin to see the same researchers cited again and again, then this is often an indication that no new ideas have been generated to address the research problem.

- Search Google Scholar to identify who has subsequently cited leading scholars already identified in your literature review [see next sub-tab]. This is called citation tracking and there are a number of sources that can help you identify who has cited whom, particularly scholars from outside of your discipline. Here again, if the same authors are being cited again and again, this may indicate no new literature has been written on the topic.

Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J. and Rebecca Frels. Seven Steps to a Comprehensive Literature Review: A Multimodal and Cultural Approach . Los Angeles, CA: Sage, 2016; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016.

- << Previous: Theoretical Framework

- Next: Citation Tracking >>

- Last Updated: May 21, 2024 11:14 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER FEATURE

- 04 December 2020

- Correction 09 December 2020

How to write a superb literature review

Andy Tay is a freelance writer based in Singapore.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Literature reviews are important resources for scientists. They provide historical context for a field while offering opinions on its future trajectory. Creating them can provide inspiration for one’s own research, as well as some practice in writing. But few scientists are trained in how to write a review — or in what constitutes an excellent one. Even picking the appropriate software to use can be an involved decision (see ‘Tools and techniques’). So Nature asked editors and working scientists with well-cited reviews for their tips.

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-03422-x

Interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Updates & Corrections

Correction 09 December 2020 : An earlier version of the tables in this article included some incorrect details about the programs Zotero, Endnote and Manubot. These have now been corrected.

Hsing, I.-M., Xu, Y. & Zhao, W. Electroanalysis 19 , 755–768 (2007).

Article Google Scholar

Ledesma, H. A. et al. Nature Nanotechnol. 14 , 645–657 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Brahlek, M., Koirala, N., Bansal, N. & Oh, S. Solid State Commun. 215–216 , 54–62 (2015).

Choi, Y. & Lee, S. Y. Nature Rev. Chem . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41570-020-00221-w (2020).

Download references

Related Articles

- Research management

Brazil’s plummeting graduate enrolments hint at declining interest in academic science careers

Career News 21 MAY 24

How religious scientists balance work and faith

Career Feature 20 MAY 24

How to set up your new lab space

Career Column 20 MAY 24

Pay researchers to spot errors in published papers

World View 21 MAY 24

US halts funding to controversial virus-hunting group: what researchers think

News 16 MAY 24

Harassment of scientists is surging — institutions aren’t sure how to help

News Feature 21 MAY 24

I’m worried I’ve been contacted by a predatory publisher — how do I find out?

Career Feature 15 MAY 24

Assistant Professor in Plant Biology

The Plant Science Program in the Biological and Environmental Science and Engineering (BESE) Division at King Abdullah University of Science and Te...

Saudi Arabia (SA)

King Abdullah University of Science and Technology

Postdoctoral Fellow

New Orleans, Louisiana

Tulane University School of Medicine

Postdoctoral Associate - Immunology

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Postdoctoral Associate

Vice president, nature communications portfolio.

This is an exciting opportunity to play a key leadership role in the market-leading journal Nature Portfolio and help drive its overall contribution.

New York City, New York (US), Berlin, or Heidelberg

Springer Nature Ltd

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

ON YOUR 1ST ORDER

Different Types of Literature Review: Which One Fits Your Research?

By Laura Brown on 13th October 2023

You might not have heard that there are multiple kinds of literature review. However, with the progress in your academic career you will learn these classifications and may need to use different types of them. However, there is nothing to worry if you aren’t aware of them now, as here we are going to discuss this topic in detail.

There are approximately 14 types of literature review on the basis of their specific objectives, methodologies, and the way they approach and analyse existing literature in academic research. Of those 14, there are 4 major types. But before we delve into the details of each one of them and how they are useful in academics, let’s first understand the basics of literature review.

What is Literature Review?

A literature review is a critical and systematic summary and evaluation of existing research. It is an essential component of academic and research work, providing an overview of the current state of knowledge in a particular field.

In easy words, a literature review is like making a big, organised summary of all the important research and smart books or articles about a particular topic or question. It’s something scholars and researchers do, and it helps everyone see what we already know about that topic. It’s kind of like taking a snapshot of what we understand right now in a certain field.

It serves with some specific purpose in the research.

- Provides a comprehensive understanding of existing research on a topic.

- Identifies gaps, trends, and inconsistencies in the literature.

- Contextualise your own research within the broader academic discourse.

- Supports the development of theoretical frameworks or research hypotheses.

4 Major Types Of Literature Review

The four major types include, Narrative Review, Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Scoping Review. These are known as the major ones because they’re like the “go-to” methods for researchers in academic and research circles. Think of them as the classic tools in the researcher’s toolbox. They’ve earned their reputation because they have a unique style for literature review introduction , clear steps and specific qualities that make them super handy for different research needs.

1. Narrative Review

Narrative reviews present a well-structured narrative that reads like a cohesive story, providing a comprehensive overview of a specific topic. These reviews often incorporate historical context and offer a broad understanding of the subject matter, making them valuable for researchers looking to establish a foundational understanding of their area of interest. They are particularly useful when a historical perspective or a broad context is necessary to comprehend the current state of knowledge in a field.

2. Systematic Review

Systematic reviews are renowned for their methodological rigour. They involve a meticulously structured process that includes the systematic selection of relevant studies, comprehensive data extraction, and a critical synthesis of their findings. This systematic approach is designed to minimise bias and subjectivity, making systematic reviews highly reliable and objective. They are considered the gold standard for evidence-based research as they provide a clear and rigorous assessment of the available evidence on a specific research question.

3. Meta Analysis

Meta analysis is a powerful method for researchers who prefer a quantitative and statistical perspective. It involves the statistical synthesis of data from various studies, allowing researchers to draw more precise and generalisable conclusions by combining data from multiple sources. Meta analyses are especially valuable when the aim is to quantitatively measure the effect size or impact of a particular intervention, treatment, or phenomenon.

4. Scoping Review

Scoping reviews are invaluable tools, especially for researchers in the early stages of exploring a topic. These reviews aim to map the existing literature, identifying gaps and helping clarify research questions. Scoping reviews provide a panoramic view of the available research, which is particularly useful when researchers are embarking on exploratory studies or trying to understand the breadth and depth of a subject before conducting more focused research.

Different Types Of Literature review In Research

There are some more approaches to conduct literature review. Let’s explore these classifications quickly.

5. Critical Review

Critical reviews provide an in-depth evaluation of existing literature, scrutinising sources for their strengths, weaknesses, and relevance. They offer a critical perspective, often highlighting gaps in the research and areas for further investigation.

6. Theoretical Review

Theoretical reviews are centred around exploring and analysing the theoretical frameworks, concepts, and models present in the literature. They aim to contribute to the development and refinement of theoretical perspectives within a specific field.

7. Integrative Review

Integrative reviews synthesise a diverse range of studies, drawing connections between various research findings to create a comprehensive understanding of a topic. These reviews often bridge gaps between different perspectives and provide a holistic overview.

8. Historical Review

Historical reviews focus on the evolution of a topic over time, tracing its development through past research, events, and scholarly contributions. They offer valuable context for understanding the current state of research.

9. Methodological Review

Among the different kinds of literature reviews, methodological reviews delve into the research methods and methodologies employed in existing studies. Researchers assess these approaches for their effectiveness, validity, and relevance to the research question at hand.

10. Cross-Disciplinary Review

Cross-disciplinary reviews explore a topic from multiple academic disciplines, emphasising the diversity of perspectives and insights that each discipline brings. They are particularly useful for interdisciplinary research projects and uncovering connections between seemingly unrelated fields.

11. Descriptive Review

Descriptive reviews provide an organised summary of existing literature without extensive analysis. They offer a straightforward overview of key findings, research methods, and themes present in the reviewed studies.

12. Rapid Review

Rapid reviews expedite the literature review process, focusing on summarising relevant studies quickly. They are often used for time-sensitive projects where efficiency is a priority, without sacrificing quality.

13. Conceptual Review

Conceptual reviews concentrate on clarifying and developing theoretical concepts within a specific field. They address ambiguities or inconsistencies in existing theories, aiming to refine and expand conceptual frameworks.

14. Library Research

Library research reviews rely primarily on library and archival resources to gather and synthesise information. They are often employed in historical or archive-based research projects, utilising library collections and historical documents for in-depth analysis.

Each type of literature review serves distinct purposes and comes with its own set of strengths and weaknesses, allowing researchers to choose the one that best suits their research objectives and questions.

Choosing the Ideal Literature Review Approach in Academics

In order to conduct your research in the right manner, it is important that you choose the correct type of review for your literature. Here are 8 amazing tips we have sorted for you in regard to literature review help so that you can select the best-suited type for your research.

- Clarify Your Research Goals: Begin by defining your research objectives and what you aim to achieve with the literature review. Are you looking to summarise existing knowledge, identify gaps, or analyse specific data?

- Understand Different Review Types: Familiarise yourself with different kinds of literature reviews, including systematic reviews, narrative reviews, meta-analyses, scoping reviews, and integrative reviews. Each serves a different purpose.

- Consider Available Resources: Assess the resources at your disposal, including time, access to databases, and the volume of literature on your topic. Some review types may be more resource-intensive than others.

- Alignment with Research Question: Ensure that the chosen review type aligns with your research question or hypothesis. Some types are better suited for answering specific research questions than others.

- Scope and Depth: Determine the scope and depth of your review. For a broad overview, a narrative review might be suitable, while a systematic review is ideal for an in-depth analysis.

- Consult with Advisors: Seek guidance from your academic advisors or mentors. They can provide valuable insights into which review type best fits your research goals and resources.

- Consider Research Field Standards: Different academic fields have established standards and preferences for different forms of literature review. Familiarise yourself with what is common and accepted in your field.

- Pilot Review: Consider conducting a small-scale pilot review of the literature to test the feasibility and suitability of your chosen review type before committing to a larger project.

Bonus Tip: Crafting an Effective Literature Review

Now, since you have learned all the literature review types and have understood which one to prefer, here are some bonus tips for you to structure a literature review of a dissertation .

- Clearly Define Your Research Question: Start with a well-defined and focused research question to guide your literature review.

- Thorough Search Strategy: Develop a comprehensive search strategy to ensure you capture all relevant literature.

- Critical Evaluation: Assess the quality and credibility of the sources you include in your review.

- Synthesise and Organise: Summarise the key findings and organise the literature into themes or categories.

- Maintain a Systematic Approach: If conducting a systematic review, adhere to a predefined methodology and reporting guidelines.

- Engage in Continuous Review: Regularly update your literature review to incorporate new research and maintain relevance.

Some Useful Tools And Resources For You

Effective literature reviews demand a range of tools and resources to streamline the process.

- Reference management software like EndNote, Zotero, and Mendeley helps organise, store, and cite sources, saving time and ensuring accuracy.

- Academic databases such as PubMed, Google Scholar, and Web of Science provide access to a vast array of scholarly articles, with advanced search and citation tracking features.

- Research guides from universities and libraries offer tips and templates for structuring reviews.

- Research networks like ResearchGate and Academia.edu facilitate collaboration and access to publications. Literature review templates and research workshops provide additional support.

Some Common Mistakes To Avoid

Avoid these common mistakes when crafting literature reviews.

- Unclear research objectives result in unfocused reviews, so start with well-defined questions.

- Biased source selection can compromise objectivity, so include diverse perspectives.

- Never miss on referencing; proper citation and referencing are essential for academic integrity.

- Don’t overlook older literature, which provides foundational insights.

- Be mindful of scope creep, where the review drifts from the research question; stay disciplined to maintain focus and relevance.

While Summing Up On Various Types Of Literature Review

As we conclude this classification of fourteen distinct approaches to conduct literature reviews, it’s clear that the world of research offers a multitude of avenues for understanding, analysing, and contributing to existing knowledge.

Whether you’re a seasoned scholar or a student beginning your academic journey, the choice of review type should align with your research objectives and the nature of your topic. The versatility of these approaches empowers you to tailor your review to the demands of your project.

Remember, your research endeavours have the potential to shape the future of knowledge, so choose wisely and dive into the world of literature reviews with confidence and purpose. Happy reviewing!

Laura Brown, a senior content writer who writes actionable blogs at Crowd Writer.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- ScientificWorldJournal

- v.2024; 2024

- PMC10807936

Writing a Scientific Review Article: Comprehensive Insights for Beginners

Ayodeji amobonye.

1 Department of Biotechnology and Food Science, Faculty of Applied Sciences, Durban University of Technology, P.O. Box 1334, KwaZulu-Natal, Durban 4000, South Africa

2 Writing Centre, Durban University of Technology, P.O. Box 1334 KwaZulu-Natal, Durban 4000, South Africa

Japareng Lalung

3 School of Industrial Technology, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Gelugor 11800, Pulau Pinang, Malaysia

Santhosh Pillai

Associated data.

The data and materials that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Review articles present comprehensive overview of relevant literature on specific themes and synthesise the studies related to these themes, with the aim of strengthening the foundation of knowledge and facilitating theory development. The significance of review articles in science is immeasurable as both students and researchers rely on these articles as the starting point for their research. Interestingly, many postgraduate students are expected to write review articles for journal publications as a way of demonstrating their ability to contribute to new knowledge in their respective fields. However, there is no comprehensive instructional framework to guide them on how to analyse and synthesise the literature in their niches into publishable review articles. The dearth of ample guidance or explicit training results in students having to learn all by themselves, usually by trial and error, which often leads to high rejection rates from publishing houses. Therefore, this article seeks to identify these challenges from a beginner's perspective and strives to plug the identified gaps and discrepancies. Thus, the purpose of this paper is to serve as a systematic guide for emerging scientists and to summarise the most important information on how to write and structure a publishable review article.

1. Introduction

Early scientists, spanning from the Ancient Egyptian civilization to the Scientific Revolution of the 16 th /17 th century, based their research on intuitions, personal observations, and personal insights. Thus, less time was spent on background reading as there was not much literature to refer to. This is well illustrated in the case of Sir Isaac Newton's apple tree and the theory of gravity, as well as Gregor Mendel's pea plants and the theory of inheritance. However, with the astronomical expansion in scientific knowledge and the emergence of the information age in the last century, new ideas are now being built on previously published works, thus the periodic need to appraise the huge amount of already published literature [ 1 ]. According to Birkle et al. [ 2 ], the Web of Science—an authoritative database of research publications and citations—covered more than 80 million scholarly materials. Hence, a critical review of prior and relevant literature is indispensable for any research endeavour as it provides the necessary framework needed for synthesising new knowledge and for highlighting new insights and perspectives [ 3 ].

Review papers are generally considered secondary research publications that sum up already existing works on a particular research topic or question and relate them to the current status of the topic. This makes review articles distinctly different from scientific research papers. While the primary aim of the latter is to develop new arguments by reporting original research, the former is focused on summarising and synthesising previous ideas, studies, and arguments, without adding new experimental contributions. Review articles basically describe the content and quality of knowledge that are currently available, with a special focus on the significance of the previous works. To this end, a review article cannot simply reiterate a subject matter, but it must contribute to the field of knowledge by synthesising available materials and offering a scholarly critique of theory [ 4 ]. Typically, these articles critically analyse both quantitative and qualitative studies by scrutinising experimental results, the discussion of the experimental data, and in some instances, previous review articles to propose new working theories. Thus, a review article is more than a mere exhaustive compilation of all that has been published on a topic; it must be a balanced, informative, perspective, and unbiased compendium of previous studies which may also include contrasting findings, inconsistencies, and conventional and current views on the subject [ 5 ].

Hence, the essence of a review article is measured by what is achieved, what is discovered, and how information is communicated to the reader [ 6 ]. According to Steward [ 7 ], a good literature review should be analytical, critical, comprehensive, selective, relevant, synthetic, and fully referenced. On the other hand, a review article is considered to be inadequate if it is lacking in focus or outcome, overgeneralised, opinionated, unbalanced, and uncritical [ 7 ]. Most review papers fail to meet these standards and thus can be viewed as mere summaries of previous works in a particular field of study. In one of the few studies that assessed the quality of review articles, none of the 50 papers that were analysed met the predefined criteria for a good review [ 8 ]. However, beginners must also realise that there is no bad writing in the true sense; there is only writing in evolution and under refinement. Literally, every piece of writing can be improved upon, right from the first draft until the final published manuscript. Hence, a paper can only be referred to as bad and unfixable when the author is not open to corrections or when the writer gives up on it.

According to Peat et al. [ 9 ], “everything is easy when you know how,” a maxim which applies to scientific writing in general and review writing in particular. In this regard, the authors emphasized that the writer should be open to learning and should also follow established rules instead of following a blind trial-and-error approach. In contrast to the popular belief that review articles should only be written by experienced scientists and researchers, recent trends have shown that many early-career scientists, especially postgraduate students, are currently expected to write review articles during the course of their studies. However, these scholars have little or no access to formal training on how to analyse and synthesise the research literature in their respective fields [ 10 ]. Consequently, students seeking guidance on how to write or improve their literature reviews are less likely to find published works on the subject, particularly in the science fields. Although various publications have dealt with the challenges of searching for literature, or writing literature reviews for dissertation/thesis purposes, there is little or no information on how to write a comprehensive review article for publication. In addition to the paucity of published information to guide the potential author, the lack of understanding of what constitutes a review paper compounds their challenges. Thus, the purpose of this paper is to serve as a guide for writing review papers for journal publishing. This work draws on the experience of the authors to assist early-career scientists/researchers in the “hard skill” of authoring review articles. Even though there is no single path to writing scientifically, or to writing reviews in particular, this paper attempts to simplify the process by looking at this subject from a beginner's perspective. Hence, this paper highlights the differences between the types of review articles in the sciences while also explaining the needs and purpose of writing review articles. Furthermore, it presents details on how to search for the literature as well as how to structure the manuscript to produce logical and coherent outputs. It is hoped that this work will ease prospective scientific writers into the challenging but rewarding art of writing review articles.

2. Benefits of Review Articles to the Author

Analysing literature gives an overview of the “WHs”: WHat has been reported in a particular field or topic, WHo the key writers are, WHat are the prevailing theories and hypotheses, WHat questions are being asked (and answered), and WHat methods and methodologies are appropriate and useful [ 11 ]. For new or aspiring researchers in a particular field, it can be quite challenging to get a comprehensive overview of their respective fields, especially the historical trends and what has been studied previously. As such, the importance of review articles to knowledge appraisal and contribution cannot be overemphasised, which is reflected in the constant demand for such articles in the research community. However, it is also important for the author, especially the first-time author, to recognise the importance of his/her investing time and effort into writing a quality review article.

Generally, literature reviews are undertaken for many reasons, mainly for publication and for dissertation purposes. The major purpose of literature reviews is to provide direction and information for the improvement of scientific knowledge. They also form a significant component in the research process and in academic assessment [ 12 ]. There may be, however, a thin line between a dissertation literature review and a published review article, given that with some modifications, a literature review can be transformed into a legitimate and publishable scholarly document. According to Gülpınar and Güçlü [ 6 ], the basic motivation for writing a review article is to make a comprehensive synthesis of the most appropriate literature on a specific research inquiry or topic. Thus, conducting a literature review assists in demonstrating the author's knowledge about a particular field of study, which may include but not be limited to its history, theories, key variables, vocabulary, phenomena, and methodologies [ 10 ]. Furthermore, publishing reviews is beneficial as it permits the researchers to examine different questions and, as a result, enhances the depth and diversity of their scientific reasoning [ 1 ]. In addition, writing review articles allows researchers to share insights with the scientific community while identifying knowledge gaps to be addressed in future research. The review writing process can also be a useful tool in training early-career scientists in leadership, coordination, project management, and other important soft skills necessary for success in the research world [ 13 ]. Another important reason for authoring reviews is that such publications have been observed to be remarkably influential, extending the reach of an author in multiple folds of what can be achieved by primary research papers [ 1 ]. The trend in science is for authors to receive more citations from their review articles than from their original research articles. According to Miranda and Garcia-Carpintero [ 14 ], review articles are, on average, three times more frequently cited than original research articles; they also asserted that a 20% increase in review authorship could result in a 40–80% increase in citations of the author. As a result, writing reviews can significantly impact a researcher's citation output and serve as a valuable channel to reach a wider scientific audience. In addition, the references cited in a review article also provide the reader with an opportunity to dig deeper into the topic of interest. Thus, review articles can serve as a valuable repository for consultation, increasing the visibility of the authors and resulting in more citations.

3. Types of Review Articles