- The Magazine

- Stay Curious

- The Sciences

- Environment

- Planet Earth

Meet the woman without fear

Kentucky, USA. A woman known only as SM is walking through Waverly Hills Sanatorium, reputedly one of the “most haunted” places in the world. Now a tourist attraction, the building transforms into a haunted house every Halloween, complete with elaborate decorations, spooky noises and actors dressed in monstrous costumes. The experience is silly but still unnerving and the ‘monsters’ often manage to score frights from the visitors by leaping out of hidden corners.

But not SM. While others show trepidation before walking down empty corridors, she leads the way and beckons her companions to follow. When monsters leap out, she never screams in fright; instead, she laughs, approaches and talks to them. She even scares one of the monsters by poking it in the head.

SM is a woman without fear. She doesn’t feel it. She has been held at knifepoint without a tinge of panic. She’ll happily handle live snakes and spiders, even though she claims not to like them. She can sit through reels of upsetting footage without a single start. And all because a pair of almond-shaped structures in her brain – amygdalae – have been destroyed.

Ralph Adolphs, Antonio Damasio and Daniel Tranel at the University of Iowa have been working with SM for over a decade. She is a 44-year old mother-of-three, who suffers from a rare genetic condition called Urbach-Wiethe disease , which has caused parts of her brain to harden and waste away. This creeping damage has completely destroyed her amygdala, a part of the brain involved in processing emotion (white arrows in the diagram below). She’s one of the few people who shows such a striking pattern of damage.

Even so, her IQ is normal. Her memory is good, as are her language and perception skills. But she has problems dealing with fear. Way back in 1994, the group showed that SM has trouble recognising fear in other people. She can’t tell what fearful facial expressions mean , even though she’s more than capable of discerning other emotions. Even though she’s a talented artist, she can’t draw a scared face, once claiming that she didn’t know what such a face would look like. Now, in a study led by Justin Feinstein, the team have found that SM cannot feel fear either.

During her visit to Waverley Hills, SM rated her level of fear throughout the experience. She said that she was excited and enthusiastic in the same way that she feels when she rides a rollercoaster, but never scared – her scores always stayed at zero. In a similar trip to an exotic pet store, her levels of fear never climbed over a score of 2 out of 10. Even though she claimed to “hate” snakes and spiders, she was drawn to the snake enclosure, was excited about holding a serpent (“This is so cool!”) and had to be told not to touch or poke the bigger, more dangerous snakes (and a nearby tarantula). Why? She was overcome with “curiosity”.

When Feinstein showed SM a set of film clips, she generally behaved on cue, laughing at the happy clips and shouting in revulsion at the disgusting ones. But in response to ten scary film clips (including The Shining , Seven , and The Ring )… nothing. She showed no signs of terror, nor did she report any. She said that most people would probably be scared by the films but she herself felt nothing.

SM’s unusual reactions during these isolated scenarios are reflected in her day-to-day life. When Feinstein gave her an electronic handheld “emotion diary”, she reported feeling every basic emotion other than fear. In fact, out of a range of 50 possible emotional descriptions, the one she rated most highly over 3 months was “fearless”. (It’s fascinating data, although (and Feinstein admits this) it’s unfortunate that he didn’t collect similar data from healthy individuals to compare against).

After more digging, Feinstein uncovered a history of behaviour consistent with a lack of fear. SM’s eldest son can’t remember a single instance when mom felt fear or looked like she was scared. His anecdotes even support the results of Feinstein’s pet store trip. “Me and my brothers… see this snake on the road,” he writes. “I was like, ‘Holy cow, that’s a big snake!’ Well mom just ran over there and picked it up and brought it out of the street, put it in the grass and let it go on its way… She would always tell me how she was scared of snakes and stuff like that, but then all of a sudden she’s fearless of them. I thought that was kind of weird.”

Other events in SM’s life are less benign. Fourteen years ago, she was walking through a small park at 10pm, when a man beckoned her over to a bench. As she approached, he pulled her down stuck a knife to her throat and said, “I’m going to cut you, bitch!” SM didn’t panic; she didn’t feel afraid. Hearing a church choir sing in the distance, she confidently said, “If you’re going to kill me, you’re gonna have to go through my God’s angels first.” The man let her go and she walked (not ran) away. The next day, she returned to the same park.

These sorts of things happen to her a lot. It’s not that SM has had a cosseted life. She lives in a poor area “replete with crime, drugs and danger”. As Feinstein writes, “she has been held up at knife point and at gun point, she was once physically accosted by a woman twice her size, she was nearly killed in an act of domestic violence, and on more than one occasion she has been explicitly threatened with death.” But in most of these situations, she didn’t act with urgency or desperation, something that police reports have corroborated.

It’s not that she doesn’t understand the concept of fear; after all, she knew that other people might be scared by the films she saw. However, she has a lot of problems with detecting danger. In a previous study, the team showed that she has no personal bubble . She’ll happily stand a foot away from complete strangers, far closer than most people would be comfortable with (even though, again, she understands the concept of personal space). It’s no surprise that she gets herself into a lot of difficult situations.

It’s fascinating how this looks to other people. A few years back, the team asked two clinical psychologists to interview SM without any knowledge of her condition. They described her as a “survivor”, as “resilient” and even “heroic” in how she coped with adversity. If you ask the woman herself, she’ll say that she feels upset or angry in the face of danger, but never fearful. Feinstein even thinks that because of her brain damage, she could be immune to posttraumatic stress disorder, a trait that she shares with some combat veterans .

It wasn’t always like this. She remembers being afraid of the dark as a young child, running away screaming when her older brother jumped out from behind a tree, and being pinned to a corner by a large Doberman (“That’s the only time I really felt scared. Like gut-wrenching scared”). But all of these events happened before her disease wrecked her amygdalae. During her adult life, Feinstein couldn’t find a single episode where she clearly experienced fear.

But Elizabeth Phelps, who studies emotion at New York University, isn’t convinced. Her team has also worked with people whose amygdalae have been severely damaged and while they also have trouble recognising fear in others, they all feel fear in their normal lives (as assessed with similar diaries to the ones that Feinstein used).

Given the fact that SM is just a single patient, and inconsistencies with previous research, Phelps says, “I don’t think the authors were appropriately cautious.” However, she adds, “It could be the difference between their findings and ours is linked to when during development the amygdala lesion occurred in our respective patients.” Feinstein acknowledges that SM has injuries to other parts of her brain and these could have exacerbated the harm done to her amygdala to produce her unique immunity to fear.

Phelps also points out that SM has been “tested extensively and has some knowledge of her condition”. Perhaps she is overplaying her lack of fear, even subconsciously, to conform to the team’s expectations? Feinstein thinks that’s “highly unlikely”. He and his colleagues have never mentioned to SM that they’re focusing on fear. Their experiments largely involve a spectrum of emotions and they tell SM that they’re interested in emotion, memory and other general concepts. When explicitly asked, she said that they’re interested in how her brain damage affects her behaviour. More importantly, Feinstein says, “After over two decades of extensive testing with SM, we have been repeatedly impressed by her lack of insight into her specific fear impairments.”

Even SM’s case doesn’t imply that the amygdala is the brain’s fear centre. Feinstein thinks that it’s more of a “broker”, going between parts of the brain that sense things in the environment, and those in the brainstem that initiate fearful actions. Damage to the amygdala breaks the chain between seeing something scary and acting on it.

If that seems like a good thing, think again. In comic books, conquering fear is a good basis for a successful vigilante lifestyle. In real life, the consequences are far direr. As Feinstein writes, “[SM]’s behaviour, time and time again, leads her back to the very situations she should be avoiding, highlighting the indispensable role that the amygdala plays in promoting survival by compelling the organism away from danger. Indeed, it appears that without the amygdala, the evolutionary value of fear is lost.”

Already a subscriber?

Register or Log In

Keep reading for as low as $1.99!

Sign up for our weekly science updates.

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Chapter 1 endnote 33, from How Emotions are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain by Lisa Feldman Barrett . Some context is:

But then, a funny thing happened. Scientists found that SM could see fear in body postures and hear fear in voices. [,..] SM also had difficulty seeing fear in scenes only when they contained faces; see Adolphs and Tranel 2003. SM’s difficulties have other explanations not related to fear.

Much of our understanding of the neural basis of fear comes from studying Patient SM . For an interesting description of her life and struggles, see Feinstein et. al (2016). [1]

- 1 Perceiving fear

- 2 Experiencing fear

- 3 Notes on SM's brain

- 4 Notes on the Notes

Perceiving fear

SM has difficulty seeing fear in a very specific situation: when she is asked to overtly identify a face that's portraying a stereotyped fear expression (i.e., a facial configuration for fear used in the basic emotion method). [2] In laboratory experiments where she was presented with posed facial configurations and asked to explicitly identify them, SM didn’t look at the eyes in the photographs. This is significant because in fear poses, the eyes are distinctively wide, showing lots of sclera (the white of the eye), [3] and neurons in the amygdala are particularly sensitive to sclera. [4] When SM was directed to pay attention to the eyes, she could explicitly identify stereotyped fear faces as effectively as neurotypical subjects could. [3] Scientists also found that SM had difficulty identifying facial configurations of surprise, which also show lots of sclera. [5]

Additionally, SM improved when she was put under time pressure. She could pick out a face posing a stereotyped fear pose in an array of happy, sad, and calm faces when instructed to do it rapidly. Also, when shown two basic emotion configurations for an extremely short time (about 40 milliseconds), she could identify the one showing more fear, anger, or threat. [6] So, SM could clearly identify fearful configurations under some circumstances, even without her amygdalae. Interestingly, other patients who have amygdalae damaged by Urbach-Wiethe disease show no changes in fear-related behavior (such as Patient AM , discussed in chapter 1), or they spend a longer time looking at the widened eyes of stereotyped fear poses and have no difficulty correctly categorizing those faces as fearful. [7] [8] [9]

SM is able to perceive fear in bodies posed to look fearful, and in vocalizations that depict fear (e.g., screams). [10] [11] She is able to identify threatening scenes except when they contain posed fear faces. [12] In her everyday life, SM is able to perceive fear in friends—for example, she ventures out during a storm to help a scared friend in need and calls the police for others in danger. [1]

Experiencing fear

As discussed in chapter 1, SM has difficulty in experiencing fear in many typical circumstances (e.g., horror movies, haunted houses). But she experiences fear in many other circumstances, particularly when the feeling is intense. She experiences fear when asked to breathe air with higher concentrations of CO 2 (and she continues to experience fear after repeated exposure to CO 2 even when neurotypical subjects habituate somewhat). SM avoids breaking the law for fear of getting in trouble. And she is able “learn fear” in the real world; for example, she is averse to seeking medical treatment or visiting the dentist because of intense pain she experienced on a previous occasions. [1]

Interestingly, SM spontaneously reports feeling worried, but she does not use the word "fear" to describe her experiences. The average person in the U.S. avoids breaking the law or going to the dentist out of fear, so it is easy to infer that SM would also be feeling fear. With this observation in mind, it may be important to consider that SM has had difficulties sustaining long-term relationships with people in her life, a fact that is distressing to her. There is one clear exception to this rule, however: SM has sustained a relationship with the scientists who have studied her for almost two decades. SM relies on them—she calls them for support (e.g., when she is worried or afraid, such as when did not want to return to the doctor for painful medical treatment), and they help her with the details of daily life (financial and otherwise). [1] It would be interesting to examine whether SM is aware of their hypothesis that the amygdala contains the circuitry for fear.

Notes on SM's brain

It should be noted (but rarely is) that SM’s brain shows abnormalities that extend beyond the amygdala, including the anterior entorhinal cortex and ventromedial prefrontal cortex, both of which show dense, reciprocal connections to the amygdala and very likely play a role in SM’s specific behavioral profile. [13] [14]

Notes on the Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Feinstein, Justin S., Ralph Adolphs, and Daniel Tranel. 2016. "A tale of survival from the world of Patient S.M." In Living Without an Amygdala , edited by David G. Amaral & Ralph Adolphs, 1-38. New York: Guilford.

- ↑ Adolphs, Ralph, Daniel Tranel, Hanna Damasio, and Antonio Damasio. 1994. "Impaired recognition of emotion in facial expressions following bilateral damage to the human amygdala." Nature 372 (6507): 470-474.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Adolphs, Ralph, Frederic Gosselin, Tony W. Buchanan, Daniel Tranel, Philippe Schyns, and Antonio R. Damasio. 2005. "A mechanism for impaired fear recognition after amygdala damage." Nature 433 (7021): 68-72.

- ↑ Whalen, Paul J., Jerome Kagan, Robert G. Cook, F. Caroline Davis, Hackjin Kim, Sara Polis, Donald G. McLaren et al. 2004. "Human amygdala responsivity to masked fearful eye whites." Science 306 (5704): 2061.

- ↑ Adolphs, Ralph, James A. Russell, and Daniel Tranel. 1999. "A role for the human amygdala in recognizing emotional arousal from unpleasant stimuli." Psychological Science 10 (2): 167-171.

- ↑ Tsuchiya, Naotsugu, Farshad Moradi, Csilla Felsen, Madoka Yamazaki, and Ralph Adolphs. 2009. "Intact rapid detection of fearful faces in the absence of the amygdala." Nature neuroscience 12 (10): 1224–1225.

- ↑ Terburg, David, B. E. Morgan, E. R. Montoya, I. T. Hooge, H. B. Thornton, A. R. Hariri, J. Panksepp, D. J. Stein, and J. Van Honk. 2012. "Hypervigilance for fear after basolateral amygdala damage in humans." Translational Psychiatry 2 (5): e115.

- ↑ See also: De Gelder, Beatrice, David Terburg, Barak Morgan, Ruud Hortensius, Dan J. Stein, and Jack van Honk. 2014. "The role of human basolateral amygdala in ambiguous social threat perception." Cortex 52: 28-34.

- ↑ See also Van Honk, J., D. Terburg, H. Thornton, D. J. Stein, and B. Morgan. "Consequences of selective bilateral lesions to the basolateral amygdala in humans." In Living Without an Amygdala , edited by David G. Amaral & Ralph Adolphs, {{{pages}}}. New York: Guilford.

- ↑ Adolphs, Ralph, and Daniel Tranel. 1999. "Intact recognition of emotional prosody following amygdala damage." Neuropsychologia 37 (11): 1285-1292.

- ↑ Atkinson, Anthony P., Andrea S. Heberlein, and Ralph Adolphs. 2007. "Spared ability to recognise fear from static and moving whole-body cues following bilateral amygdala damage." Neuropsychologia 45 (12): 2772-2782.

- ↑ Adolphs, Ralph, and Daniel Tranel. 2003. "Amygdala damage impairs emotion recognition from scenes only when they contain facial expressions." Neuropsychologia 41 (10): 1281-1289.

- ↑ Boes, Aaron D., Sonya Mehta, David Rudrauf, Ellen Van Der Plas, Thomas Grabowski, Ralph Adolphs, and Peg Nopoulos. 2012. "Changes in cortical morphology resulting from long-term amygdala damage." Social cognitive and affective neuroscience 7 (5): 588-595.

- ↑ Hampton, Alan N., Ralph Adolphs, J. Michael Tyszka, and John P. O'Doherty. 2007. "Contributions of the amygdala to reward expectancy and choice signals in human prefrontal cortex." Neuron 55 (4): 545-555.

Navigation menu

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 8: Fear, Anxiety, and Stress

S.M. Case Study: Impairment in Recognition

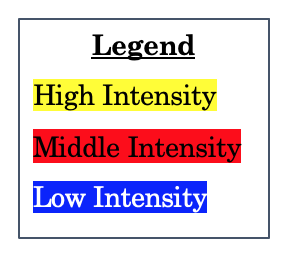

In the first set of tasks, participants were presented with photos of human emotional facial expressions (similar to Ekman’s judgment methodology; Adolphs, Tranel, et al., 1999). Specifically, participants were shown six male and female faces of anger, fear, happiness, surprise, sadness, disgust, and also three neutral faces. While viewing each photo, participants indicated on a scale of 0 to 5 ( 0 = not at all; 5 = very much ) the intensity of six emotions shown on the face: happy, sadness, disgusted, angry, afraid, and surprised. During each trial, participants were asked to rate the intensity of one of the six emotion labels for a group of facial expressions. Figure 11 below displays the findings for three groups of participants. The bilateral amygdala damage group included 9 participants, one of whom was S.M. As indicated in the legend, yellow colors indicate participants selected high intensity (around a 4/5) for the emotion in the face, red indicates moderate intensity (around a 3) and blue indicates low intensity (around a 1/2). To interpret each figure, you should compare the facial expression displayed to participants in the y-axis to the emotional intensity rating (1-5 scale) as reported by the participants. Some findings are described under the figure.

Reproduced from “Recognition of facial emotion in nine individuals with bilateral amygdala damage,” R. Adolphs, D. Tranel, S. Hamann, A.W. Young, A.J. Calder, E.A. Phelps, A. Anderson, G.P. Lee, and A.R. Damasio, 1999 Neuropsychologia, 37, p. 1113, (https://doi.org/10.1016/50028-3932(99)00039-1). Copyright 1999 by Elsevier Science Ltd.

Based on Figure 11, the following conclusions can be made:

- Normal controls and brain-damaged controls showed similar performance. When shown an emotional facial expression, these participants reported the corresponding emotion to be most intense. For instance, when participants saw a disgusted face, they rated the face as intensely disgusting. This demonstrates that control participants were able to identify and recognize the emotional experience in others’ faces.

- When comparing bilateral amygdalae damage patients to the control groups, some of the emotion expressions do not show a corresponding highly intense emotion label. In particular, this is found for faces of fear, anger, and disgust. These findings suggest that impairment to the amygdala may hinder one’s ability to identify how much anger, fear, and disgust a person is showing, but this impairment does not exist for surprise, happy, and sad faces.

- These figures also show that control participants show overlap in their ratings of certain emotion labels for the same face. For example, when controls viewed an angry face, they reported high intensity for the emotions anger and disgust. This overlap is not as intense for bilateral damaged patients.

These initial findings show that amygdala damage does indeed impair recognition of fear in others. But this also shows that amygdala does control the identification of other emotions.

A follow-up study (Spezio et al., 2007) investigated the location of S.M.’s visual gaze when interpreting others’ facial expressions. Before discussing this study, it is important to note that people determine whether someone is experiencing fear mostly from their eyes. Even when someone is smiling, but their eyes are fearful – people interpret the facial expression as fear. In this study, S.M. and several healthy female controls engaged in a face-to-face or live video interaction with a professional actor who maintained a neutral facial expression. During the interaction, the participants wore an eye tracker. Findings (see Figure 12) showed that compared to controls, S.M. spent less time fixated on the actor’s eyes and more time staring at the actor’s mouth. This might suggest when the amygdala is damaged people identify the wrong facial expression because they are looking at the wrong part of the face. These finding have been replicated with still photos as well, but in the still photos S.M. focused more on the center of the face (Adolphs et al., 2005). Finally, although amygdala-damaged patients experience difficulty identifying emotions in facial expressions, their ability to identify an individual from their face is not hindered (Adolphs et al., 1994; 1995). Thus, if S.M. runs into her friend Wang, S.M. would think “This is my friend, Wang,” but she might have trouble interpreting Wang’s facial expressions.

Psychology of Human Emotion: An Open Access Textbook Copyright © by Michelle Yarwood is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Brain Development

- Childhood & Adolescence

- Diet & Lifestyle

- Emotions, Stress & Anxiety

- Learning & Memory

- Thinking & Awareness

- Alzheimer's & Dementia

- Childhood Disorders

- Immune System Disorders

- Mental Health

- Neurodegenerative Disorders

- Infectious Disease

- Neurological Disorders A-Z

- Body Systems

- Cells & Circuits

- Genes & Molecules

- The Arts & the Brain

- Law, Economics & Ethics

Neuroscience in the News

- Supporting Research

- Tech & the Brain

- Animals in Research

- BRAIN Initiative

- Meet the Researcher

- Neuro-technologies

- Tools & Techniques

Core Concepts

- For Educators

- Ask an Expert

- The Brain Facts Book

Patient S.M.

- Published 9 Dec 2020

- Author Calli McMurray

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Because of damage to her amygdala, Patient S.M. lives a life without fear. This may sound appealing, but fear helps us avoid danger.

Brain Bytes showcase essential facts about neuroscience.

Design by Adrienne Tong .

Image: Courtesy of Iowa Neurological Patient Registry at the University of Iowa .

About the Author

Calli McMurray

Calli McMurray is the Media & Science Writing Associate at SfN. She graduated from the University of Texas at Austin in 2019 with a Bachelor of Science in Neuroscience.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Feinstein, J. S., Adolphs, R., Damasio, A., & Tranel, D. (2011). The human amygdala and the induction and experience of fear. Current biology : CB, 21 (1), 34–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2010.11.042

Adolphs, R., Tranel, D., Damasio, H. et al. (1994). Impaired recognition of emotion in facial expressions following bilateral damage to the human amygdala. Nature, 372 , 669–672. https://doi.org/10.1038/372669a0

Yong, E. (2019, May 17). Meet the woman without fear. Retrieved November 12, 2020, from https://www.discovermagazine.com/mind/meet-the-woman-without-fear

Parida, J. R., Misra, D. P., & Agarwal, V. (2015). Urbach-Wiethe syndrome. BMJ case reports, 2015, bcr2015212443. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2015-212443

Also In Tools & Techniques

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org

BrainFacts Book

Download a copy of the newest edition of the book, Brain Facts: A Primer on the Brain and Nervous System.

A beginner's guide to the brain and nervous system.

Check out the latest news from the field.

SUPPORTING PARTNERS

- Privacy Policy

- Accessibility Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Manage Cookies

Some pages on this website provide links that require Adobe Reader to view.

- Abnormal Psychology

- Assessment (IB)

- Biological Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminology

- Developmental Psychology

- Extended Essay

- General Interest

- Health Psychology

- Human Relationships

- IB Psychology

- IB Psychology HL Extensions

- Internal Assessment (IB)

- Love and Marriage

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

- Prejudice and Discrimination

- Qualitative Research Methods

- Research Methodology

- Revision and Exam Preparation

- Social and Cultural Psychology

- Studies and Theories

- Teaching Ideas

Exam Answer: Localization Short Answer Question An example SAQ following a simple 7-step format

Travis Dixon August 20, 2019 Assessment (IB) , Biological Psychology , Revision and Exam Preparation

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

Recently I wrote a post about how to write better short answer responses (SAQs) in 7 simple steps for IB Psych’ Paper 1 and this video explains the same. But the only reason I am able to explain these frameworks with confidence is because I’ve written 100s of examples. Here’s one I’ll share with you.

The example SAQ below is written following the 7 step structure I explained in this blog post ( link ). While there are definitely other ways to write an excellent short answer response, I like to keep things consistent and simple, especially with students who are in their first year of studying IB Psych.

Read more:

- 7 simple steps to better exam answers (SAQs)( Link )

Click here to download this answer with examiner comments as a PDF.

Describe localization with reference to one relevant study..

One example of localization is the fact that the amygdala helps us feel fear. This can be seen in SM’s case study.

Localization of function refers to the fact that different parts of the brain are responsible for different functions. For example, the hippocampus helps turn short-term memories into long-term memories and the amygdala plays an important role in the fear response. The amygdala helps to activate our fear response to prepare the body for the fight or flight response. When our amygdala perceives a threatening stimulus it activates the HPA axis, which results in the release of stress hormones like adrenaline and cortisol. Interestingly, the amygdala detects threat in our environment before we are consciously aware of the presence of the threat. This rapid response to threat is an evolutionary adaptation that has helped us to survive.

The role of the amygdala in emotion was first studied in the 1880s and later the 1950s on studies involving monkeys and lesioning. However, after modern technology like MRIs were invented psychologists could study the amygdala and fear in humans. For example, Feinstein et al’s case study on SM provides strong evidence for the importance of the amygdala in the fear response. SM is a woman in her 40s (at the time of the study) who had bilateral amygdala damage as a result of a genetic condition. She made for a valuable case study because it is rare for people to have damage only in their amygdala because it is hidden deep within the brain. Feinstein et al. wanted to see if the amygdala is necessary to feel fear so they did a series of tests and gathered data on SM. For example, they took her to an exotic pet store with snakes and spiders, a haunted house and they showed her scary film clips. The researchers observed that SM displayed no signs of fear, but she did show other emotions (e.g. she laughed at comedy clips and had fun in the haunted house).

From this study, the researchers concluded that one function of the amygdala is to perceive threats and to activate a fear response so we can feel fear. This is an important function because a healthy fear response keeps us safe. This can be further shown by the fact that the biographical details of SM found that she found herself in many dangerous situations.

In conclusion, one example of localization of function is the amygdala’s role in fear and this can be shown in SM’s case study.

Disagree? Got a question? Feel free to leave a comment.

Find more example answers and exam help in our revision book. Download your free preview here .

Order your copy at https://store.themantic-education.com/

Travis Dixon is an IB Psychology teacher, author, workshop leader, examiner and IA moderator.

- Neuroscience

The Neuroscience of Behavior: Five Famous Cases

Five patients who shaped our understanding of behavior and the brain..

Posted January 16, 2020 | Reviewed by Lybi Ma

“Considering everything, it seems we are dealing here with a special illness… There are certainly more psychiatric illnesses than are listed in our textbooks.” —Alois Alzheimer (In: Benjamin, 2018)

Once thought to be the product of demonic possession, immorality, or imbalanced humors, we now know that psychiatric symptoms are often caused by changes in the brain. Read on to learn about the people who helped us understand the brain as the driving force behind our behaviors.

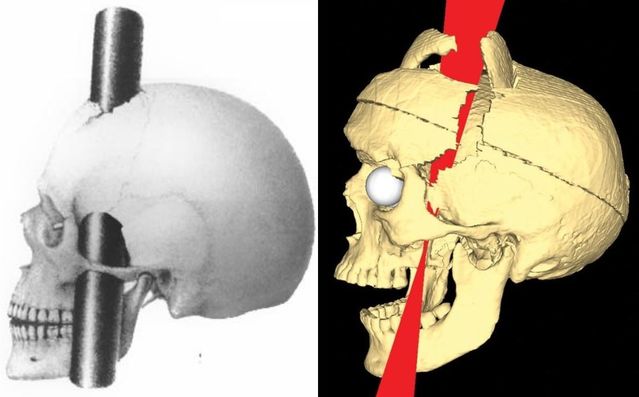

Phineas Gage

In 1848, John Harlow first described the case of a 25-year-old railroad foreman named Phineas Gage. Gage was a "temperate" man: hardworking, polite, and well-liked by all those around him. One day, Gage was struck through the skull by an iron rod launched in an accidental explosion. The rod traveled through the prefrontal cortex of his brain. Remarkably, he survived with no deficits in his motor function or memory . However, his family and friends noticed major changes in his personality . He became impatient, unreliable, vulgar, and was even described as developing the "animal passions of a strong man." This was the first glimpse into the important role of the prefrontal cortex in personality and social behavior (David, 2009; Thiebaut de Schotten, 2015; Benjamin, 2018).

Louis Victor Leborgne

Pierre Broca first published the case of 50-year-old Louis Victor Leborgne in 1861. Despite normal intelligence , Leborgne inexplicably lost the ability to speak. His nickname was Tan, after this became the only word he ever uttered. He was otherwise unaffected and seemed to follow directions and understand others without difficulty. After he died, Broca examined his brain, finding an abnormal area of brain tissue only in the left anterior frontal lobe. This suggested that the left and right sides of the brain were not always symmetric in their functions, as previously thought. Broca later went on to describe several other similar cases, cementing the role of the left anterior frontal lobe (now called Broca’s area) as a crucial region for producing (but not understanding) language (Dronkers, 2007; David, 2009; Thiebaut de Schotten, 2015).

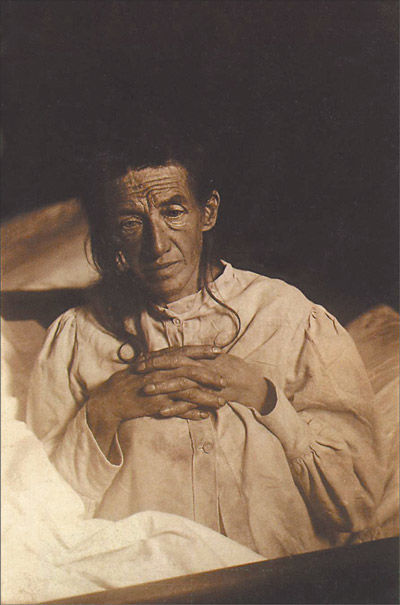

Auguste Deter

Psychiatrist and neuropathologist Aloysius Alzheimer described the case of Auguste Deter, a 56-year-old woman who passed away in 1906 after she developed strange behaviors, hallucinations, and memory loss. When Alzheimer looked at her brain under the microscope, he described amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles that we now know are a hallmark of the disease that bears his name. This significant discovery was the first time that a biological molecule such as a protein was linked to a psychiatric illness (Shorter, 1997; David, 2009; Kalia & Costa e Silva, 2015).

In 1933, Spafford Ackerly described the case of "JP” who, beginning at a very young age, would do crude things like defecate on others' belongings, expose himself, and masturbate in front of other children at school. These behaviors worsened as he aged, leading to his arrest as a teenager . He was examined by Ackerly who found that the boy had a large cyst, likely present from birth, that caused severe damage to his prefrontal cortices. Like the case of Phineas Gage, JP helped us understand the crucial role that the prefrontal cortex plays in judgment, decision-making , social behaviors, and personality (Benjamin, 2018).

HM (Henry Gustav Molaison)

William Scoville first described the case of HM, a 29-year-old man whom he had treated two years earlier with an experimental surgery to remove his medial temporal lobes (including the hippocampus and amygdala on both sides). The hope was that the surgery would control his severe epilepsy, and it did seem to help. But with that improvement came a very unexpected side effect: HM completely lost the ability to form certain kinds of new memories. While he was still able to form new implicit or procedural memories (like tying shoes or playing the piano), he was no longer able to form new semantic or declarative memories (like someone’s name or major life events). This taught us that memories were localized to a specific brain region, not distributed throughout the whole brain as previously thought (David, 2009; Thiebaut de Schotten, 2015; Benjamin, 2018).

Facebook /LinkedIn image: Gorodenkoff/Shutterstock

Benjamin, S., MacGillivray, L., Schildkrout, B., Cohen-Oram, A., Lauterbach, M.D., & Levin, L.L. (2018). Six landmark case reports essential for neuropsychiatric literacy. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci, 30 , 279-290.

Shorter, E., (1997). A history of psychiatry: From the era of the asylum to the age of Prozac. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Thiebaut de Schotten, M., Dell'Acqua, F., Ratiu, P. Leslie, A., Howells, H., Cabanis, E., Iba-Zizen, M.T., Plaisant, O., Simmons, A, Dronkers, N.F., Corkin, S., & Catani, M. (2015). From Phineas Gage and Monsieur Leborgne to H.M.: Revisiting disconnection syndromes. Cerebral Cortex, 25 , 4812-4827.

David, A.S., Fleminger, S., Kopelman, M.D., Lovestone, S., & Mellers, J. (2009). Lishman's organic psychiatry: A textbook of neuropsychiatry. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

Kalia, M., & Costa e Silva, J. (2015). Biomarkers of psychiatric diseases: Current status and future prospects. Metabolism, 64, S11-S15.

Dronkers, N.F., Plaisant, O., Iba-Zizen, M.T., & Cabanis, E.A. (2007). Paul Broca's historic cases: High resolution MR Imaging of the brains of Leborgne and Lelong. Brain , 130, 1432–1441.

Scoville, W.B., & Milner, B. (1957). Loss of recent memory after bilateral hippocampal lesions. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiat., 20, 11-21.

Melissa Shepard, MD , is an assistant professor of psychiatry at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is a Case Study?

Weighing the pros and cons of this method of research

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Cara Lustik is a fact-checker and copywriter.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Cara-Lustik-1000-77abe13cf6c14a34a58c2a0ffb7297da.jpg)

Verywell / Colleen Tighe

- Pros and Cons

What Types of Case Studies Are Out There?

Where do you find data for a case study, how do i write a psychology case study.

A case study is an in-depth study of one person, group, or event. In a case study, nearly every aspect of the subject's life and history is analyzed to seek patterns and causes of behavior. Case studies can be used in many different fields, including psychology, medicine, education, anthropology, political science, and social work.

The point of a case study is to learn as much as possible about an individual or group so that the information can be generalized to many others. Unfortunately, case studies tend to be highly subjective, and it is sometimes difficult to generalize results to a larger population.

While case studies focus on a single individual or group, they follow a format similar to other types of psychology writing. If you are writing a case study, we got you—here are some rules of APA format to reference.

At a Glance

A case study, or an in-depth study of a person, group, or event, can be a useful research tool when used wisely. In many cases, case studies are best used in situations where it would be difficult or impossible for you to conduct an experiment. They are helpful for looking at unique situations and allow researchers to gather a lot of˜ information about a specific individual or group of people. However, it's important to be cautious of any bias we draw from them as they are highly subjective.

What Are the Benefits and Limitations of Case Studies?

A case study can have its strengths and weaknesses. Researchers must consider these pros and cons before deciding if this type of study is appropriate for their needs.

One of the greatest advantages of a case study is that it allows researchers to investigate things that are often difficult or impossible to replicate in a lab. Some other benefits of a case study:

- Allows researchers to capture information on the 'how,' 'what,' and 'why,' of something that's implemented

- Gives researchers the chance to collect information on why one strategy might be chosen over another

- Permits researchers to develop hypotheses that can be explored in experimental research

On the other hand, a case study can have some drawbacks:

- It cannot necessarily be generalized to the larger population

- Cannot demonstrate cause and effect

- It may not be scientifically rigorous

- It can lead to bias

Researchers may choose to perform a case study if they want to explore a unique or recently discovered phenomenon. Through their insights, researchers develop additional ideas and study questions that might be explored in future studies.

It's important to remember that the insights from case studies cannot be used to determine cause-and-effect relationships between variables. However, case studies may be used to develop hypotheses that can then be addressed in experimental research.

Case Study Examples

There have been a number of notable case studies in the history of psychology. Much of Freud's work and theories were developed through individual case studies. Some great examples of case studies in psychology include:

- Anna O : Anna O. was a pseudonym of a woman named Bertha Pappenheim, a patient of a physician named Josef Breuer. While she was never a patient of Freud's, Freud and Breuer discussed her case extensively. The woman was experiencing symptoms of a condition that was then known as hysteria and found that talking about her problems helped relieve her symptoms. Her case played an important part in the development of talk therapy as an approach to mental health treatment.

- Phineas Gage : Phineas Gage was a railroad employee who experienced a terrible accident in which an explosion sent a metal rod through his skull, damaging important portions of his brain. Gage recovered from his accident but was left with serious changes in both personality and behavior.

- Genie : Genie was a young girl subjected to horrific abuse and isolation. The case study of Genie allowed researchers to study whether language learning was possible, even after missing critical periods for language development. Her case also served as an example of how scientific research may interfere with treatment and lead to further abuse of vulnerable individuals.

Such cases demonstrate how case research can be used to study things that researchers could not replicate in experimental settings. In Genie's case, her horrific abuse denied her the opportunity to learn a language at critical points in her development.

This is clearly not something researchers could ethically replicate, but conducting a case study on Genie allowed researchers to study phenomena that are otherwise impossible to reproduce.

There are a few different types of case studies that psychologists and other researchers might use:

- Collective case studies : These involve studying a group of individuals. Researchers might study a group of people in a certain setting or look at an entire community. For example, psychologists might explore how access to resources in a community has affected the collective mental well-being of those who live there.

- Descriptive case studies : These involve starting with a descriptive theory. The subjects are then observed, and the information gathered is compared to the pre-existing theory.

- Explanatory case studies : These are often used to do causal investigations. In other words, researchers are interested in looking at factors that may have caused certain things to occur.

- Exploratory case studies : These are sometimes used as a prelude to further, more in-depth research. This allows researchers to gather more information before developing their research questions and hypotheses .

- Instrumental case studies : These occur when the individual or group allows researchers to understand more than what is initially obvious to observers.

- Intrinsic case studies : This type of case study is when the researcher has a personal interest in the case. Jean Piaget's observations of his own children are good examples of how an intrinsic case study can contribute to the development of a psychological theory.

The three main case study types often used are intrinsic, instrumental, and collective. Intrinsic case studies are useful for learning about unique cases. Instrumental case studies help look at an individual to learn more about a broader issue. A collective case study can be useful for looking at several cases simultaneously.

The type of case study that psychology researchers use depends on the unique characteristics of the situation and the case itself.

There are a number of different sources and methods that researchers can use to gather information about an individual or group. Six major sources that have been identified by researchers are:

- Archival records : Census records, survey records, and name lists are examples of archival records.

- Direct observation : This strategy involves observing the subject, often in a natural setting . While an individual observer is sometimes used, it is more common to utilize a group of observers.

- Documents : Letters, newspaper articles, administrative records, etc., are the types of documents often used as sources.

- Interviews : Interviews are one of the most important methods for gathering information in case studies. An interview can involve structured survey questions or more open-ended questions.

- Participant observation : When the researcher serves as a participant in events and observes the actions and outcomes, it is called participant observation.

- Physical artifacts : Tools, objects, instruments, and other artifacts are often observed during a direct observation of the subject.

If you have been directed to write a case study for a psychology course, be sure to check with your instructor for any specific guidelines you need to follow. If you are writing your case study for a professional publication, check with the publisher for their specific guidelines for submitting a case study.

Here is a general outline of what should be included in a case study.

Section 1: A Case History

This section will have the following structure and content:

Background information : The first section of your paper will present your client's background. Include factors such as age, gender, work, health status, family mental health history, family and social relationships, drug and alcohol history, life difficulties, goals, and coping skills and weaknesses.

Description of the presenting problem : In the next section of your case study, you will describe the problem or symptoms that the client presented with.

Describe any physical, emotional, or sensory symptoms reported by the client. Thoughts, feelings, and perceptions related to the symptoms should also be noted. Any screening or diagnostic assessments that are used should also be described in detail and all scores reported.

Your diagnosis : Provide your diagnosis and give the appropriate Diagnostic and Statistical Manual code. Explain how you reached your diagnosis, how the client's symptoms fit the diagnostic criteria for the disorder(s), or any possible difficulties in reaching a diagnosis.

Section 2: Treatment Plan

This portion of the paper will address the chosen treatment for the condition. This might also include the theoretical basis for the chosen treatment or any other evidence that might exist to support why this approach was chosen.

- Cognitive behavioral approach : Explain how a cognitive behavioral therapist would approach treatment. Offer background information on cognitive behavioral therapy and describe the treatment sessions, client response, and outcome of this type of treatment. Make note of any difficulties or successes encountered by your client during treatment.

- Humanistic approach : Describe a humanistic approach that could be used to treat your client, such as client-centered therapy . Provide information on the type of treatment you chose, the client's reaction to the treatment, and the end result of this approach. Explain why the treatment was successful or unsuccessful.

- Psychoanalytic approach : Describe how a psychoanalytic therapist would view the client's problem. Provide some background on the psychoanalytic approach and cite relevant references. Explain how psychoanalytic therapy would be used to treat the client, how the client would respond to therapy, and the effectiveness of this treatment approach.

- Pharmacological approach : If treatment primarily involves the use of medications, explain which medications were used and why. Provide background on the effectiveness of these medications and how monotherapy may compare with an approach that combines medications with therapy or other treatments.

This section of a case study should also include information about the treatment goals, process, and outcomes.

When you are writing a case study, you should also include a section where you discuss the case study itself, including the strengths and limitiations of the study. You should note how the findings of your case study might support previous research.

In your discussion section, you should also describe some of the implications of your case study. What ideas or findings might require further exploration? How might researchers go about exploring some of these questions in additional studies?

Need More Tips?

Here are a few additional pointers to keep in mind when formatting your case study:

- Never refer to the subject of your case study as "the client." Instead, use their name or a pseudonym.

- Read examples of case studies to gain an idea about the style and format.

- Remember to use APA format when citing references .

Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2011;11:100.

Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2011 Jun 27;11:100. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-11-100

Gagnon, Yves-Chantal. The Case Study as Research Method: A Practical Handbook . Canada, Chicago Review Press Incorporated DBA Independent Pub Group, 2010.

Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods . United States, SAGE Publications, 2017.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Becoming first time father of premature newborn during the first wave of the pandemic: a case study approach.

- 1 EA3188 Laboratoire de Psychologie, Université de Franche-Comté, Besançon, France

- 2 School of Early Childhood Education, Faculty of Education, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece

The final, formatted version of the article will be published soon.

Select one of your emails

You have multiple emails registered with Frontiers:

Notify me on publication

Please enter your email address:

If you already have an account, please login

You don't have a Frontiers account ? You can register here

The aim of this paper is to delve into the emotional and psychological challenges that fathers face as they navigate the complexities of having a preterm infant in the NICU and in an unprecedented sanitary context. We used three data collection methods such as interviews (narrative and the Clinical Interview for Parents of High-risk Infants-CLIP) and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) to gain a comprehensive understanding of the cases. The following analysis explores two individuals' personal experiences of becoming a first-time father during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic through a close examination of two superordinate themes: "A series of separations through the experienced COVID-19 restrictions" and "Moments of connection." The transition to fatherhood is essentially with a medicalized form of connection with their newborn and the perceived paternal identity. In terms of temporality, these fathers experienced a combination of concerns about their infants' long-term development and COVID-19 health concerns. Furthermore,

Keywords: first-time fathers, prematurity, experienced separations, moments of connection, Experiential approach, qualitative study, COVID-19

Received: 26 Feb 2024; Accepted: 03 May 2024.

Copyright: © 2024 Jean-Dit-Pannel, Dubroca and Koliouli. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Romuald Jean-Dit-Pannel, EA3188 Laboratoire de Psychologie, Université de Franche-Comté, Besançon, France

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Featured Neurology Neuroscience. · December 17, 2010. A woman with bilateral damage relatively restricted to the amygdala is the subject of a case study recently reported. SM, as she will be known to the public, seems able to experience emotions such as happiness and sadness normally, but shows no signs of fear.

The study's lead authors met SM, who has a rare genetic condition called Urbach-Wiethe disease, more than 2 decades ago. As a result of her illness, she has "two perfectly symmetrical black holes" where her amygdala should be, says Justin Feinstein, a graduate student in clinical psychology at the University of Iowa in Iowa City.

Learn from an expert why SM's story is one of the most famous case studies in affective neuroscience. SM is a woman who lost the ability to learn from fear after the loss of her amygdala. ... So SM is one of the most famous case studies in all of affective neuroscience. She is a woman who is currently, I think, in her 40s. And as far as we can ...

Patient S. M..is one of the most renowned lesion cases in the history of neuropsychology. Her focal bilateral amygdala damage has led to a host of behavioral impairments that have been well-documented across dozens of research publications. This chapter provides an overview of S. M.'s seminal contributions to the study of brain-behavior relationships, with an emphasis on the role of the human ...

be induced in SM, thereby preempting her experience of fear. Throughout this study,we define fear induction as the expo-sure to stimuli capable of triggering a state of fear. Fear experience, on the other hand, is the subjective feeling of fear, and it was measured by SM's self-report of her internal experi-

S.M., sometimes referred to as SM-046, is an American woman with a peculiar type of brain damage that physiologically reduces her ability to feel fear.First described by scientists in 1994, she has had exclusive and complete bilateral amygdala destruction since late childhood as a consequence of Urbach-Wiethe disease.Dubbed by the media as the "woman with no fear", S.M. has been studied ...

S.M. is a famous case study that has provided some information about the amygdala. S.M. was diagnosed with Urbach-Weithe disease and thus her brain damage is confined to the amygdala. In the upcoming section, we will discuss some very interesting findings related to S.M.'s emotional experiences. (You can also read more about her case on ...

Although clinical observations suggest that humans with amygdala damage have abnormal fear reactions and a reduced experience of fear [1-3], these impressions have not been systematically investigated.To address this gap, we conducted a new study in a rare human patient, SM, who has focal bilateral amygdala lesions [].To provoke fear in SM, we exposed her to live snakes and spiders, took her ...

Source BrainFacts/SfN. One woman's rare condition left her with an astonishing side effect: the inability to feel fear. This provided researchers an opportunity to study a behavior most of us take for granted. Hear the story from the doctor who first diagnosed the woman known as Patient SM in this podcast from BrainFacts.org.

One reason contradictory findings might exist is because participants in the PANAS study reported their emotions over a long period - which measures more of a trait than state emotion. Second, the Adolphs, Russell, et al. (1999) study looked at deficits in identifying facial expressions, whereas the PANAS study investigated subjective feelings.

Ralph Adolphs, Antonio Damasio and Daniel Tranel at the University of Iowa have been working with SM for over a decade. She is a 44-year old mother-of-three, who suffers from a rare genetic condition called Urbach-Wiethe disease, which has caused parts of her brain to harden and waste away.This creeping damage has completely destroyed her amygdala, a part of the brain involved in processing ...

SM is able to perceive fear in bodies posed to look fearful, and in vocalizations that depict fear (e.g., screams). She is able to identify threatening scenes except when they contain posed fear faces. In her everyday life, SM is able to perceive fear in friends—for example, she ventures out during a storm to help a scared friend in need and ...

In this study, S.M. and several healthy female controls engaged in a face-to-face or live video interaction with a professional actor who maintained a neutral facial expression. During the interaction, the participants wore an eye tracker. Findings (see Figure 12) showed that compared to controls, S.M. spent less time fixated on the actor's ...

Patient S.M. Published 9 Dec 2020. Author Calli McMurray. Source BrainFacts/SfN. Because of damage to her amygdala, Patient S.M. lives a life without fear. This may sound appealing, but fear helps us avoid danger. Brain Bytes showcase essential facts about neuroscience. Design by A. Tong. Design by Adrienne Tong.

Social Cognition Battery. Social cognition battery (Prior et al., 2003) is a self-administered task with four different tests assessing different aspects of social cognition, namely, the emotion attribution, the theory of mind, the social situation, and the moral/conventional distinction.In each test, the participant is asked to read brief stories and to answer the related questions.

Summary. Although clinical observations suggest that humans with amygdala damage have abnormal fear reactions and a reduced experience of fear [ 1, 2, 3 ], these impressions have not been systematically investigated. To address this gap, we conducted a new study in a rare human patient, SM, who has focal bilateral amygdala lesions [ 4 ].

SAR Exemplar #1: Localization. Describe localization with reference to one relevant study. One example of localization is the fact that the amygdala helps us feel fear. This can be seen in SM's case study. Localization of function refers to the fact that different parts of the brain are responsible for different functions.

SM was a person who was born with lesions in her amygdalae caused by a genetic disorder. This impaired her ability to feel fear and to recognise it in others. What was the aim of the case study? To investigate whether the amygdala is responsible for fear processing. What was the method?

For example, Feinstein et al. (2011) conducted a case study on SM, a patient with bilateral amygdala damage (damage to amygdalae on both sides of the brain). This was due to a genetic condition. In this study, the researchers exposed SM to a range of fear-inducing stimuli, including going to an exotic pet store, visiting a haunted house and ...

One example of localization is the fact that the amygdala helps us feel fear. This can be seen in SM's case study. Localization of function refers to the fact that different parts of the brain are responsible for different functions. For example, the hippocampus helps turn short-term memories into long-term memories and the amygdala plays an ...

Source: By Henry Jacob Bigelow; Ratiu et al. Phineas Gage. In 1848, John Harlow first described the case of a 25-year-old railroad foreman named Phineas Gage. Gage was a "temperate" man ...

An overview of the SM Case Study as detailed in the course content for IB Psychology SL. current biology 21, january 11, 2011 ª2011 elsevier ltd all rights

A case study is an in-depth study of one person, group, or event. In a case study, nearly every aspect of the subject's life and history is analyzed to seek patterns and causes of behavior. Case studies can be used in many different fields, including psychology, medicine, education, anthropology, political science, and social work.

Sec. Pediatric Psychology Volume 15 - 2024 | doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1391857 ... Becoming first time father of premature newborn during the first wave of the pandemic: a case study approach Provisionally accepted Romuald Jean-Dit-Pannel 1* Chloé Dubroca 1 Flora Koliouli 2. 1 EA3188 ...