Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 13 October 2017

Rethinking higher education and its relationship with social inequalities: past knowledge, present state and future potential

- Theocharis Kromydas 1

Palgrave Communications volume 3 , Article number: 1 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

128k Accesses

150 Citations

77 Altmetric

Metrics details

The purposes and impact of higher education on the economy and the broader society have been transformed through time in various ways. Higher education institutional and policy dynamics differ across time, but also between countries and political regimes and therefore context cannot be neglected. This article reviews the purpose of higher education and its institutional characteristics juxtaposing two, allegedly rival, conceptual frameworks; the instrumental and the intrinsic one. Various pedagogical traditions are critically reviewed and used as examples, which can potentially inform today’s policy making. Since, higher education cannot be seen as detached from all other lower levels of education appropriate conceptual links are offered throughout this article. Its significance lies on the organic synthesis of literature across social science, suggesting ways of going forward based on the traditions that already exist but seem underutilized so far because of overdependence in market-driven practices. This offers a new insight on how theories can inform policy making, through conceptual “bridging” and reconciliation. The debate on the purpose of higher education is placed under the context of the most recent developments of increasing social inequalities in the western world and its relation to the mass model of higher education and the relevant policy decisions for a continuous increase in participation. This article suggests that the current policy focus on labor market driven policies in higher education have led to an ever growing competition transforming this social institution to an ordinary market-place, where attainment and degrees are seen as a currency that can be converted to a labour market value. Education has become an instrument for economic progress moving away from its original role to provide context for human development. As a result, higher education becomes very expensive and even if policies are directed towards openness, in practice, just a few have the money to afford it. A shift toward a hybrid model, where the intrinsic purpose of higher education is equally acknowledged along with its instrumental purpose should be seen by policy makers as the way forward to create educational systems that are more inclusive and societies that are more knowledgeable and just.

Similar content being viewed by others

The impact of artificial intelligence on employment: the role of virtual agglomeration

Identity and inequality misperceptions, demographic determinants and efficacy of corrective measures

Participatory action research

Introduction.

The mainstream view in the western world, as informed by the human capital theory sees education, as an ordinary investment and the main reason why someone consumes time and money to undertake higher levels of education, is the high returns expected from the corresponding wage premium, when enters the labour market (Becker, 1964 , 1993 ). Nevertheless, things in practice are more complicated and this sequence of events is unlikely to be sustained, especially in recession periods like the one we currently live in. On the contrary, one notion of education, related somewhat to the American liberal arts tradition, is the intrinsic notion, which interprets that the purpose of education is to ‘equip people to make their own free, autonomous choices about the life they will lead’ (Bridges, 1992 : 92). There might be an economic basis underpinning this individual choice, but the intrinsic notion permits more subjective motivations, which are not necessarily affected by economic circumstances.

Robinson and Aronica ( 2009 ) argue that education, have become an impersonal linear process, a type of assembly line, similar to a factory production. They challenge this view and call for a less standardised pedagogy; more personalised to students needs as well as talents. Education is not similar to a manufacturing production-line, since students are highly concerned about the quality of education they receive as opposed to motor cars, which are indifferent to the process by which they are manufactured. Along these lines, Waters ( 2012 ), following Weber’s ( 1947 , 1968 ) rationale on the role of bureaucracy in modern societies, adds that this manufacturing process is achieved through rigid, rationalised and productively efficient but totally impersonal bureaucracy, operated in a way that sees children as raw materials for the creation of adults, which is the final product properly equipped to reproduce “itself” by being a parent to a new born “raw material” and so forth. Durkheim ( 1956 , 2006 ) sees this as a mechanism where adults exercise their influence over the younger in order to maintain the status quo they desire. However, since education entails ontological as well as epistemological implications, primary focus should be given to learning in such a way that educative and social functions could be amalgamated, rather than solely focusing on the delivery of existing knowledge per se, which becomes a reiterated process and an unchallenged absolute truth (Freire, 1970 ; Heidegger, 1988 ; Dall’ Alba and Barnacle, 2007 ).

This article focus on higher education; since it is the last stage before somebody enters the labour market and thus the instrumental view becomes more dominant over the intrinsic view, compared to the lower levels of education. Higher education, is being traditionally offered by universities. The first established university in Europe is the University of Bologna, where the term “academic freedom” was introduced as the kernel of its culture (Newman, 1996 ). Graham ( 2013 ) distinguishes between three different models of higher education. These are: the university college, the research and the technical university. He provides a historical review of the origins of these three models. The university college is the oldest one, where Christian values were the core values. Later on, when scientific knowledge questioned the universal theological truth, another type of university has been established, where research was the ultimate goal of the scholarship. This type of university has subsequently transformed by the introduction of the liberal arts tradition, flourished in the US. The research university model, originated circa 16 th century in Cambridge and established in Berlin by the introduction of the Humboldian University, shared a common aim: the pursuit of knowledge and its dissemination to the greater society. The third model of university is the technical one. It has been established in an industrial revolution context in Scotland and particularly in Glasgow in the premises of what is currently known as the University of Strathclyde. While the introduction of capitalism changed radically the structure and the format of labour relations, the technical model was based on the idea that industrial skills had to be acquired by formal education and somehow verified institutionally in order to be applied to the broader society. This is the first time where the up to then distinct fields of education and industry, started to be conceived as inextricably tight in a rather linear way.

These different models of higher education cultures and traditions still exist, but in reality, Universities worldwide follow a hybrid approach, where all traditions collaborate with each other. However, there are some universities that still carry the reputation and tradition of a specific model and to some extent this tradition differentiates them from all others. It is not the scope of this research to analyse this in detail, as the main aim is to offer an institutional and policy narrative, exploring the purpose of higher education and its relationship with social inequalities, focusing primarily on the western world.

Nowadays, in a rapidly changing word, the major debate is placed under the forms of institutional transformation of higher education. Brennan ( 2004 ), based on Trow ( 1979 , 2000 ), allocates three forms of higher education. The first one is the elite form, which main aim is to prepare and shape the mind-set of students originated from the most dominant class. The second is the mass form of higher education, which transmits the knowledge and skills acquired in higher education into the technical and economic roles students subsequently perform in the labour market. Lastly, the third is the universal form, which main purpose is to adapt students and the general population to the rapid social and technological changes.

This article reviews the contemporary trends in higher education and its widespread diffusion as interacted with the evolutions in western economies and societies, where social inequalities persist and even become wider (Dorling and Dorling, 2015 ). The narrative used in this article is more suitable to conceptualise higher education in a western world context, though we acknowledge that via globalisation, the way education and particularly higher education is delivered in the rest of the world seems to follow similar to the Western worlds paths, despite the apparent differences in culture, social and economic systems as well as writing systems. Footnote 1

An interdisciplinary and critical synthesis of the relevant literature is conducted, presenting two stances that are largely considered as rival: The instrumental one that treats higher education as an ordinary investment with particular financial yields in the labour market and the more intrinsic one which sees higher education as mainly detached from the logic of economic costs and benefits. The theoretical rivalry is apparent since in the former approach higher education is an inevitable property of labour market and thus an indispensable part of the mainstream economic neoliberal regime, whereas the latter sees no logical link between higher education and labour market purposes and therefore the content and substance of learning and knowledge acquisition in education and specifically in higher education should not be market-driven or aligned to the functions of specific economic regimes. However, this article argues that educational systems, and particularly their higher levels, are amalgamated parts of contemporary societies and therefore theories and practices need to move away from rather futile binary rationales.

The remainder of this paper explains why both the intrinsic and instrumental approaches are doomed to fail in practice when used in isolation. In a rapidly diverging and polarised world, where social inequalities rise within as well as between countries, common sense dictates social theories and practices to move towards reconciliation rather than stubborn rivalry. In that spirit, this paper argues that the intrinsic and instrumental approach are in fact complementary to each other. Such view can inform policy making towards building more inclusive educational systems; organically tight with the broader society. The narrative this article uses departs and expands on the rationale of eminent critical pedagogists such as Freire, Bronfenbrenner, Bourdieu and Kozol in order to challenge the current instrumental world-view of education, at least as this is apparent in the western world. Then the article moves into offering a reasoning for an organic synthesis of existing knowledge in order the two rival theories to be actualised in practice as a unified and reconciled pedagogical strategy. This reasoning builds on the research conducted by Durst’s ( 1999 ), Payne ( 1999 ) and Lu and Horner ( 2009 ). Durst ( 1999 ) suggests a “reflective instrumentalism”, where student’s pragmatic view that education is just a way of finding a well-paid job, operated in tandem with critical pedagogical canons, is indeed possible. Payne ( 1999 ) proposes a similar approach, where students are equipped with the necessary tools to find a job in the labour market; however educators should engage students with this knowledge in a critical way in order to be able to produce something new. Likewise Lu and Horner ( 2009 ) note that educators and students need to work together in such a way that perceptions of both are amenable to change and career choices are critically discussed in a constantly changing social context.

The purpose of higher education in western societies

Mokyr ( 2002 ) suggests that education should be integrated by both inculcation and emancipation in order to serve individual intellectual development as well as social progression. Shapiro ( 2005 ) emphasizes the need for the higher education institutions to serve a public purpose moving beyond narrow self-serving concerns, as well as to enforce social change in order to reflect the nature of a society that its members desire. More recently, in philosophical terms Barnett ( 2017 , p 10) calls for a wider conceptual landscape in higher education where “The task of an adequate philosophy of higher education…is not merely to understand the university or even to defend it but to change it”. )

The purpose of education and its meaning in the contemporary western societies has been also criticised by Bo ( 2009 ), suggesting that education has become a contradictory notion that leaves no space for emancipation since it gives no opportunity for improvisation to students. Thus, the students feel encaged within the system instead of being liberated. Bo agrees with Mokyr, who highlighted the need for recalling the basic notions of education from ancient philosophies: that education should be integrated by both inculcation and emancipation in order to serve individual intellectual development as well as social progression (Mokyr, 2002 ; Bo, 2009 ).

Not all individuals and societies agree on the purposes and roles of higher education in the modern world. However, in any case, it is a place where teaching and research can be accommodated in an organised fashion for the promotion of various types of knowledge, applied and non-applied. It is a place where money and moral values compete and collaborate simultaneously, where the development of labour market skills and competences coexist with the identification and utilisations of people’s skills and talents as well as the pursuit of employment, morality and citizenship.

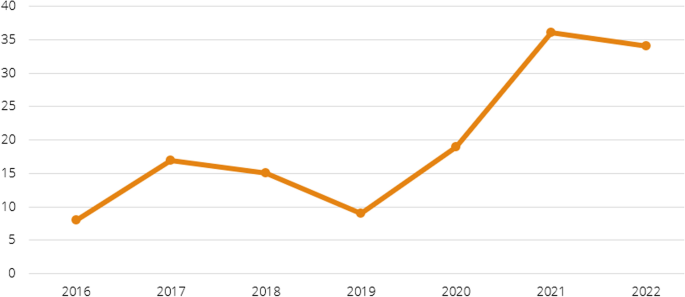

The post-WWII era has been characterised by the mass model of higher education. Before this, higher education was for those belonging to higher social classes (Brennan, 2004 ). This model became the kernel of educational policies in Europe and generally, in the western world (Shapiro, 2005 ). Such policies have been boosted by the advent of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT), which enhance commercial and non-commercial bonds between countries and higher education institutions, transforming the role of higher education even further, making it rather universal (Jongbloed et al., 2008 ). Higher education’s boundaries have become vague and the predefined “social contract” between its institutions and those participated in them, is more complicated to be defined in absolute terms. Higher education institutions are now characterised by economic competition in a strict global market environment, where governments are not the key players anymore (Brennan, 2004 ).

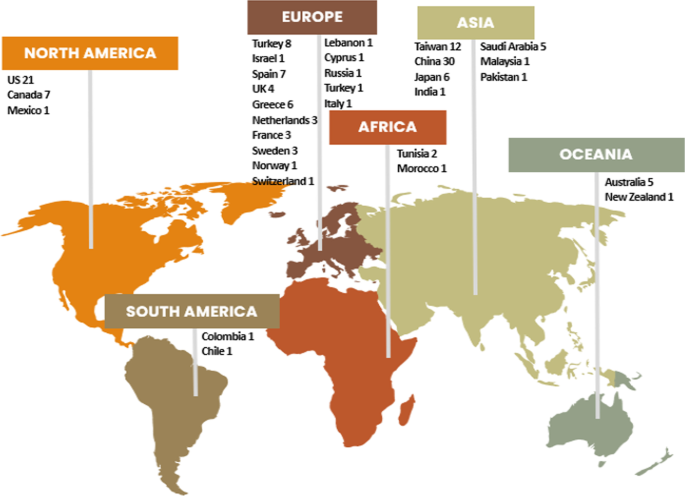

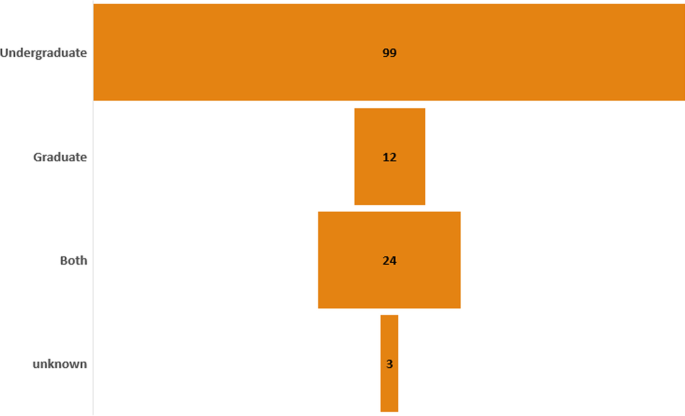

Moreover, student demographics in higher education are constantly changing. Higher education is now an industry operating in a global market. Competition to attract talents from around the world is growing rapidly as an increasing number of countries offer additional graduate and post graduate positions to non-nationals, usually at a higher cost compared to nationals (Barber et al., 2013 ). Countries such as China or Singapore that are growing economically very rapidly are investing huge amounts of money to develop their higher education system and make it more friendly to talented people from around the world. The advent of new technologies have changed the traditional model of higher education, where physical presence is not a necessary requirement anymore (Yuan et al., 2013 ). Studying while working is much easier and therefore more mature students have now the opportunity to study towards a graduate or post-graduate degree. All these developments have increased the potential for profit; however it also requires huge amount of money to be invested in new technologies and all kinds of infrastructures and resources. The need for diversification in funding sources is simply essential and therefore all other industries become inevitably more engaged (Kaiser et al., 2014 ). On top of all these, climate change, the rise of terrorism, the prolonged economic uncertainty and the automazation of labour will likely increase cross-national and intraoccupational mobility and therefore the demand for higher education, especially in the recipient countries of the economically developed western world will inevitably rise. Summing up, higher education institutions operate under a very fluid and unpredictable environment and therefore approaches that are informed by adaptability and flexibility are absolutely crucial. The hybrid approach we propose where instrumental and intrinsic values are reconciled is along these lines.

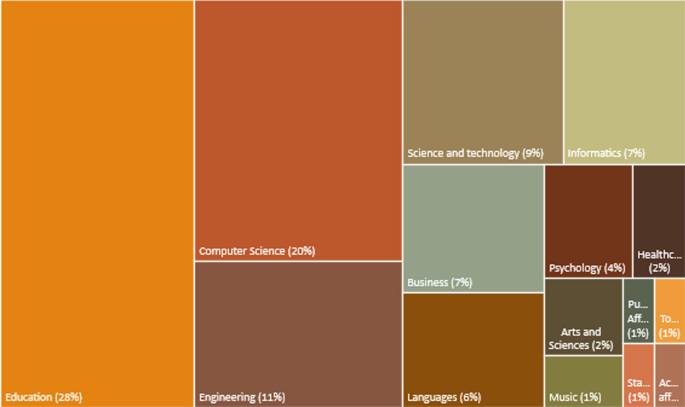

Modern views of higher education place its function under a digital knowledge-based society, where economy dominates. Labour markets demand for skills such as technological competence and complex problem-solving by critical thinking and multitasking, which increases competition and in turn, accelerates the pace of the working day (Westerheijden et al., 2007 ). Haigh and Clifford ( 2011 ) argue that high competency, in both hard and soft skills, is not enough, as higher education needs to go deeper into changing attitudes and behaviours becoming the core of a globalised knowledge-based-economy. However, the trends of transferring knowledge and skills by universities, which “increasingly instrumentalize, professionalize, vocationalize, corporatize, and ultimately technologize education” (Thomson, 2001 : 244), have been extensively criticised in epistemological as well as in ontological terms (Bourdieu, 1998 ; Dall’ Alba and Barnacle, 2007 ). Livingstone ( 2009 ) argues that education and labour market have different philosophical departures and institutional principles to fulfill and therefore conceptualising them as concomitant economic events, with strong causal conjunctions, leads to logical fallacies. Livingstone sees the intrinsic purposes of education and contemporary labour market as rather contradictory than complimentary and any attempt to see them as the latter, leads to arbitrary and ambiguous outcomes, which in turn mislead rather than inform policy making. The current article, building on the arguments of Durst’s ( 1999 ), Payne ( 1999 ) and Lu and Horner ( 2009 ) challenges this view introducing a “bridging” rationale between the two theories, which can be also actualized in practice and inform policy making.

When education, and especially higher education, is considered as a public social right that everyone should have access to, human capital, as solely informed by the investment approach, cannot be seen as the most appropriate tool to explain the benefits an individual and society can gain from education. Citizenship can be regarded as one of these tools and perhaps concepts, such as the social and c ultural capital or habitus , which contrary to human capital acknowledge that students are not engaged with education just to succeed high returns in the labour market but apart from the economic capital, should be of equal importance when we try to offer a better explanation of the individuals’ drivers to undertake higher education. (Bourdieu, 1986 ; Coleman, 1988 ). Footnote 2 For example, Bourdieu ( 1984 ) thinks that certificates and diplomas are neither indications of academic or applied to the labour market knowledge, nor signals of competences but rather take the form of tacit criteria set by the ruling class to identify people from a particular social origin. Yet, Bourdieu does not disregard the human capital theory as invalid; however he remains very sceptical on its narrow social meaning as it becomes a property of ruling class and used as a mechanism to maintain their power and tacitly reproduce social inequalities.

Higher education attainment cannot be examined irrespectively of someone’s capabilities, as its conceptual framework presupposes a social construction of interacting and competing individuals, fulfilling a certain and, sometimes common to all, task each time. Capabilities, certainly, exist in and out of this context, as it includes both innate traits and acquired skills in a dynamic social environment. Sen ( 1993 : 30) defines capability as “a person’s ability to do valuable acts or reach valuable states of being; [it] represents the alternative combinations of things a person is able to do or be”. Moreover, Sen argues that capabilities should not be seen only as a means for succeeding a certain goal, but rather as an end itself (Sen, 1985 ; Saito, 2003 ; Walker and Unterhalter, 2007 ).

Capabilities are a prerequisite of well-being and therefore, social institutions should direct people into fulfilling this aim in order to feel satisfied with their lives. However, since satisfaction is commonly understood as a subjective concept, it cannot be implied that equal levels of life satisfaction, as these perceived by people of different demographic and socio-economic characteristics, mean social and economic equality. Usually, the sense of life satisfaction is relative to future expectations, aspirations and past empirical experiences, informed by the socio-economic circumstances people live in (Saito, 2003 ).

According to the capability approach, assessing the educational attainment of individuals or the quality of teachers and curriculum are not such useful tasks, if not complemented by the capacity of a learner to convert resources into capabilities. Sen’s ( 1985 , 1993 ) capability approach, challenges the human capital theory, which sees education as an ordinary investment undertaken by individuals. It also remains sceptical towards structuralist and post-structruralist approaches, which support the dominance of institutional settings and power over the individual acts. According to Sen ( 1985 , 1993 ), educational outcomes, as these are measured by student enrolments, their performance on tests or their expected future income, are very poor indicators for evaluating the overall purpose of education, related to human well-being. Moreover, the capability approach does not imply that education can only enhance peoples’ capabilities. It also implies that education, can be detrimental, imposing severe life-long disadvantages to individuals and societies, if delivered poorly (Unterhalter, 2003 , 2005 ).

From Sen’s writings, it is not clear whether the capability approach imply a distinction between instrumental and intrinsic values. Even if someone attempts an interpretation of the capability approach by arguing that it is only means that have an instrumental value, whereas ends only an intrinsic one, it is still unclear how can we draw a line between means and ends in a rather objective way. Escaping from this rather dualistic interpretation, a common-sense argument seems apparent: Capabilities have both intrinsic and instrumental value. Material resources can be obtained through people’s innate talents and acquired skills; however through the same resources transformed into capabilities a person who does not see this as an end but rather as a means, can also become a trusted member of the community and a good citizen, given that some kind of freedom of choice exists. Thus, resources apart from their instrumental value can also have an intrinsic one, with the caveat that the person chooses to conceive them as means towards a socially responsible end.

The American tradition in student development goes back to the liberal arts tradition, which main aim is to build a free person as an active member of a civic society. The essence of this tradition can be found in Nussbaum ( 1998 : 8)

“When we ask about the relationship of a liberal education to citizenship, we are asking a question with a long history in the Western philosophical tradition. We are drawing on Socrates’ concept of ‘the examined life,’ on Aristotle’s notions of reflective citizenship, and above all on Greek and Roman Stoic notions of an education that is ‘liberal’ in that it liberates the mind from bondage of habit and custom, producing people who can function with sensitivity and alertness as citizens of the whole world.”

Nowadays, liberal arts tradition is regarded as the delivery of interdisciplinary education across the social sciences but also beyond that, aiming to prepare students for the challenges they are facing both as professionals and as members of civic society. However, as Kozol notes in reality things are quite different (Kozol, 2005 , 2012 ). Kozol devoted much of his work examining the social context of schools in the US by focusing on the interrelationships that exist, maintained or transformed between students, teachers and parents. He points out that segregation and local disparities in the US schools are continuously increasing. The US schools and especially urban schools are seen as distinctive examples of institutions where social discrimination propagates while the US educational system currently functions as a mechanism of reproducing social inequality. Kozol is very critical on the instrumental purpose of market-driven education as this places businesses and commerce as the “key players”, since they shape the purpose, content and curriculum of education. At the same time, students, their parents as well as teachers, whose roles should have been essential, are displaced into some kind of token participants.

Hess ( 2004 ) might agree that US schools have become vehicles of increasing social inequalities but he suggest a very different to Kozol’s approach. Since schools are social institutions that operate and constantly interact with the rest of economy they have to become accountable in the way that ordinary business are, at least when it comes to basic knowledge delivery. Hess insists that all schools across the US should be able to deliver high quality basic knowledge and literacy. Such knowledge can be easily standardised and a national curriculum, equal and identical to all US school can be designed. By this, all schools are able to deliver high quality basic knowledge and all pupils, irrespective of their social background, would be able to receive it. Then, each school, teacher and pupil are held accountable for their performance and failure to meet the national standards should result in schools closed down, teachers laid off and pupils change school environment or even lose their chance to graduate. Hess distinguishes between two types of reformers; the status quo reformers who do not challenge the state control education and the common-sense reformers who are in favour of a non-bureaucratic educational system, governed by market competition, subjected to accountability measures similar to those used in the ordinary business world.

While Hess presents evidence that the problem in higher education is not underfunding but efficiency in spending, the argument he makes that schools can only reformed and flourish through the laws of market competition is not adequately backed up as there are plenty of examples in many industrial sectors, where the actual implementation of market competition instead of opening up opportunities for the more disadvantaged, has finally generated huge multinationals corporations, which operate in a rather monopolistic or at best oligopolistic environment, satisfying their own interests on the expense of the most deprived and disadvantaged members of the society. The ever growing increasing competition in the financial, pharmaceutical or IT software and hardware (Apple Microsoft, IOS and Android software etc.) sectors have not really helped the disadvantaged or the sector itself but rather created powerful “too big to fail” corporations that dominate the market if not own it.

Hess indeed believes that the US educational system apart from preparing students for the labour market has a social role to fulfil. When the purpose of higher education is solely labour market-oriented teaching and learning become inadequate to respond to the social needs of a well-functioned civic democracy, which requires active learners and critical thinkers who, apart from having a job and a profession, are able “ to frame and express their thoughts and participate in their local and national communities”(p. 4) . Creating rigorous standards for basic knowledge in all US schools is a goal that is sound and rather achievable. However, when such goals are based on a Darwinian like competition and coercion where only the fittest can survive they become rather inapplicable for satisfying the needs of human development, equity and sustainable social progress.

Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory ( 1979 , 2005 , 2009 ) (subsequently named from Bronfenbrenner himself as bioecological systems theory) is also an example of schools as organic ingredients of a single concentric system that includes four sub systems; the micro, the meso, the exo and the macro as well as the chronosystem that refers to the change of the other four through time. The Micro system involves activities and roles that are experienced through interpersonal relationships such as the family, schools, religious or social institutions or any interactions with peers. The meso system includes the relationships developed between the various microsystem components, such as the relationship between school and workplace or family and schools. The exosystem comprises various interactions between systems that the person who is in the process of development does not directly participates but influence the way microsystems function and impact on the person. Some examples of exosystems are the relationships between family and peers of the developing person, family and schools, etc. The macrosystem incorporates all these things that can be considered as cultural environment and social context in which the developing person lives. Finally, the chronosystem introduces a time dimension, which encompasses all other sub-systems, subjecting them to the changes occurred through time. All these systems constantly interact, shaping a dynamic, complex but also natural ecological environment, in which a person develops its understanding of the world. In practical terms, this theory has found application in Finland, gradually transforming the Finish educational system to such a degree that is now considered the best all over the world (Määttä and Uusiautti, 2014 ; Takala et al., 2015 ). Finally, Bronfenbrenner is also an advocate that poverty and social inequalities are developed not because of differences in individual characteristics and capabilities but because of institutional constraints that are insurmountable to those from a lower socio-economic background.

Freire ( 1970 , 2009 ) criticizes the way schooling is delivered in contemporary societies. The term he uses to describe the current state of education is “banking education”, where teachers and students have very discrete roles with the former to be perceived as depositors of knowledge and the latter as depositories. This approach sees the knowledge acquired within the institutional premises of formal education as an absolute truth, where reality is perceived as something static aiming to preserve the status quo in education and in turn in society and satisfy the interests of the elite. This actual power play means that those who hold knowledge and accept its acquiring procedure as static, become the oppressors whereas those who either lack knowledge or even hold it but challenge it in order to transform it, the oppressed. From the one side the oppressors achieve to maintain their dominance over the oppressed and on the other side the oppressed accept their inferior role as an unchallenged normality where their destiny is predetermined and can never be transformed. Therefore, through this distinction of social roles, social inequalities are maintained and even intensified through time. Freire sees the “banking education” approach as a historical hubris since social reality is a process of constant transformation and hence, it is by definition dynamic and non-static. What we actually know today cannot determine our future social roles, neither can prohibit individuals from challenging and transforming it into something new (Freire, 1970 ; Giroux, 1983 ; Darder, 2003 ).

The banking education approach resembles very much the ethos of the human capital theory, where individuals utilise educational attainment as an investment instrument for succeeding higher wages in the future and also climb the levels of social hierarchy. The assumption of linearity between past individual actions and future economic and social outcomes is at the core of banking education and thus human capital theory. However, this assumption introduces a serious logical fallacy that surprisingly policy makers seem to value very little nowadays, at least in the Western societies. Freire ( 2009 ) apart from criticizing the current state of education argues that a pedagogical approach that “demythologize” and unveils reality by promoting dialogue between teachers and students create critical thinkers, who are engaged in inquiry in order to create social reality by constantly transforming it. This is the process of problem-posing education , which aligns its meaning with the intrinsic view of education that regards human development as mainly detached from the acquisition of material objects and accumulation of wealth through increased levels of educational attainment.

Originated in Germany, the term Bildung —at least as this was interpreted from 18 th century onwards, after Middle Ages era where everything was explained in the prism of a strict and theocratic society- shaped the philosophy by which the German educational system has been functioning even until nowadays (Waters, 2016 ). Bildung aims to provide the individual education with the appropriate context, through which can reach high levels of professional development as well as citizenship. It is a term strongly associated with the liberation of mind from superstition and social stereotypes. Education is assumed to have philosophical underpinnings but it needs, as philosophy itself as a whole does too, to be of some practical use and therefore some context needs to be provided Footnote 3 (Herder, 2002 ).

For Goethe ( 2006 ) Bildung , is a self-realisation process that the individual undertakes under a specific context, which aims to inculcate altruism where individual actions are consider benevolent only if they are able to serve the general society. Although Bildung tradition, from the one hand, assumes that educational process should be contextualised, it approach context as something fluid that is constantly changing. Therefore, it sees education as an interactive and dynamic process, where roles are predetermined; however at the same time they are also amenable to constant transformation (Hegel, 1977 ). Consequently, this means that Bildung tradition is more closely to what Freire calls problem-posing education and therefore to the intrinsic notion of education. Weber ( 1968 ), looked on the Bildung tradition as a means to educate scientists to be involved in policy making and overcome the problems of ineffective bureaucracy. Waters ( 2016 ) based on his experiences with teaching in German higher education argue that the Bildung tradition is still apparent today in the educational system in Germany.

However, higher education, as an institution, involves students, teachers, administrators, policy makers, workers, businessmen, marketers and generally, individuals with various social roles, different demographic characteristics and even different socio-economic backgrounds. It comes natural that their interests can be conflicting and thus, they perceive the purpose of higher education differently.

Higher education expansion and social inequalities: contemporary trends

Higher education enrolment rates have been continuously rising for the last 30 years. In Europe, and especially in the Anglo-Saxon world, policies are directed towards widening the access to higher education to a broader population (Bowl, 2012 ). However, it is very difficult for policy-makers to design a framework towards openness in higher education, mainly due to the heterogeneity of the population the policies are targeted upon. Such population includes individuals from various socio-economic, demographic, ethnic, innate ability, talent orientation or disability groups, as well as people with very different social commitments and therefore the vested interests of each group contradict each other, rendering policy-making an extremely complicated task (CFE and Edge Hill University, 2013 ).

A collection of essays, edited by Giroux and Myrsiades ( 2001 ), provided valuable insights to the humanities and social sciences literature regarding the notion of corporate university and its implications to society’s structure. As Williams ( 2001 : 18) notes in one of this essays:

“Universities are now being conscripted directly as training grounds for the corporate workforce…university work has been more directly construed to serve not only corporate-profit agendas via its grant-supplicant status, but universities have become franchises in their own right, reconfigured to corporate management, labor, and consumer models and delivering a name-brand product”.

Chang et al. ( 2013 ) argues that institutional purposes do not always coincide with the expectations students have from their studies. In most cases, students hold a more pragmatic and instrumental understanding towards the purpose of higher education, primarily aiming for a better-paid and high quality jobs.

Arum and Roksa ( 2011 ) claim that students during their studies in higher education make no real progress in critical thinking and complex problem-solving. Nonetheless, it is notable that those who state that they seek some “deeper meaning” in higher education, looking at a broader picture of things, tend to perform better than those who see university through instrumental lenses (Entwistle and Peterson, 2004 ). These findings question the validity of the instrumental view in higher education as it seems that those that are intrinsically motivated to attend higher education, end up performing much better in higher education and also later on in the labour market. Therefore, in practice, the theoretical rivalry between the intrinsic and instrumental approach operate in a rather dialectic manner, where interactions between social actors move towards a convergence, despite the focus given by policy makers on the instrumental view.

Bourdieu ( 1984 , 1986 , 1998 , 2000 ) based on his radical democratic politics, argued that education inequalities are just a transformation of social inequalities and a way of reproduction of social status quo. Aronowitz ( 2004 ) acknowledged that the main function of public education in the US is to prepare students to meet the changes, occurred in contemporary workplaces. Even if this instrumental model involves the broad expansion of educational attainment, it also fails to alleviate class-based inequalities. He is in line with Bourdieu’s argument that social class relations are reproduced through schooling, as schools reinforce, rather than reduce, class-based inequalities. More recently, similar findings from various countries are very common in the literature (Chapman et al., 2011 ; Stephens et al., 2015 )

Apple ( 2001 ) argues that despite neoliberalism’s claims that privatisation, marketization, harmonisation and generally the globalisation of educational systems increase the quality of education, there are considerable findings in numerous studies that show that the expansion of higher education happens in tandem with the increase of income inequality and the aggravation of racial, gender and class differences. Gouthro ( 2002 ) argues that there has been a misrepresentation of the basic notions that characterise the purpose of education, such as critical thinking, justice and equity. Ganding and Apple ( 2002 ) went one step further by suggesting an alternative solution, which lies on the decentralisation of educational systems, using the “Citizen School” as an example of an educational institution, which prioritises quality in education and its provision to impoverished people. Finally, they call for a radical structural reform on educational systems worldwide, where the relationship between various social communities and the state is based on social justice and not on power.

Brown and Lauder ( 2006 ) investigated the impact of the fundamental changes on education, as related to the influence that various socio-economic and cultural factors have on policy making. Remaining sceptical against the empirical validity of human capital theory, they conclude that it cannot be guaranteed that graduates will secure employment and higher wages. Contrary to Card and Lemieux’s ( 2001 ) findings, the authors argue that when the wage-premium is not measured by averages, but is split in deciles within graduates, it is only the high-earning graduates that have experienced an increasing wage-gap during this period. Increasing incidences of over-education, due to an ever-increasing supply of graduates compared to the relatively modest growth rates of high-skilled jobs, have also been observed. Any differences in pay, between graduates and non-graduates, can be ascribed more to the stagnation of non-graduates' pay, rather than to graduates’ additional pay, because of their higher educational attainment. More recently, Mettler ( 2014 ) argues that the focus on corporate interests in policy making in the US has transformed higher education into a caste system that reproduces and also intensifies social inequalities.

There are evidence, which illustrate that families play a distinctive role in encouraging children’s abilities and traits through a warm and friendly family environment. As higher education requires a significant amount of money to be invested, families with high-income have more chances and means to promote their children’s abilities and traits as well as their career prospects, when compared with the low-income ones. Certainly, there are other factors, which can affect children’s prospects, but the advantage in favour of high-income families is relatively apparent in the empirical literature (Solon, 1999 ).

Livingstone and Stowe ( 2007 ), based on the General Social Survey (GSS), conducted an empirical study on the school completion rates partitioning individuals into family and class origin, residential area as well as race and gender. They focused on the relatively low completion rates of low-class individuals, from the inner city and rural areas of the US. Their findings reveal that working-class children are being discriminated on their school completion rates, compared with the mid- and high-class children. Race and gender discrimination has been detected in rural areas but not in inner cities and suburb areas, where the completion rates are more balanced.

Stone ( 2013 ), finally sees things from a very different perspective, where inequalities exist mainly because of simply bad luck. He argues in favour of lots, when a university has to decide whether to accept an applicant or not. Even if, an argument like this seems highly controversial, it consists of something that has been implemented in many countries, several times in the past (Hyland, 2011 ). The argument that an individual deserves a place in university just because he/she scored higher marks in a standardised sorting examination test does not prove that he/she will perform better in his/her subsequent academic tasks. Likewise, if an individual, who failed to secure a place in university due to low marks, was given a chance to enter university through a different procedure, he/she might have performed exceptionally well. Yet, human society cannot solely depend on lotteries and computer random algorithms, but sometimes, up to a certain point and in the name of fairness and transparency, there is a strong case for also looking on the merits for using one (Stone, 2013 ).

Furthermore, Lowe ( 2000 ) argued that the widening of higher education participation can create a hyper-inflation of credentials, causing their serious devaluation in the labour market. This relates to the concept of diploma disease, where labour markets create a false impression that a higher degree is a prerequisite for a job and therefore, induce individuals to undertake them only for the sake of getting a job (Dore, 1976 ; Collins, 1979 ). This situation can create a highly competitive credential market, and even if there are indications of higher education expansion, individuals from lower social class do not have equal opportunities to get a degree, which can lead them to a more prestigious occupational category. This is, in turn, very similar to the Weberian theory of educational credentialism, where credentials determine social stratum (Brown, 2003 ; Karabel, 2006 ; Douthat, 2005 ; Waters, 2012 ).

The concept of credential inflation has been extensively debated from many scholars, who question the role of formal education and the usefulness of the acquisition of skills within universities (Dore 1997 ; Collins, 1979 ; Walters, 2004 ; Hayes and Wynard, 2006 ). Evans et al. ( 2004 ) focuses on the tacit skills, which cannot be acquired by formal learning, mainly obtained by work and life experience as well as informal learning. These skills are competences related to the way a complex situation could be best approached or resemble to personal traits, which can be used for handling unforeseen situations.

Policy implications

Higher educational attainment that leads to a specific academic degree is a dynamic procedure, but with a pre-defined end. This renders the knowledge acquired there, as obsolete. Policies, such as Bologna Declaration supports an agenda, where graduates should be further encouraged to engage with on-the-job training and life-long education programmes (Coffield, 1999 ). Other scholars argue that institutions should have a broader role, acknowledging the benefits that higher educational attainment bring to societies as a whole by the simultaneous promotion of productivity, innovation and democratisation as well as the mitigation of social inequalities (Harvey, 2000 ; Hayward and James, 2004 ). Boosting employability for graduates is crucial and many international organisations are working towards the establishment of a framework, which can ensure that higher education satisfies this aim (Diamond et al., 2011 ). Yet, this can have negative side-effects making the employability gap between high- and low-skilled even wider, since there is no any policy framework specifically designed for low-skilled non-graduates on a similar to Bologna Declaration, supranational context. Heinze and Knill ( 2008 ) argue that convergence in higher education policy-making, as a result of the Bologna Process, depends on a combination of cultural, institutional and socio-economic national characteristics. Even if, it can be assumed that more equal countries, in terms of these characteristics, can converge much easier, it is still questionable if and how much national policy developments have been affected by the Bologna Declaration.

However, the political narrative of equal opportunities in terms of higher education participation rates does not seem very convincing (Brown and Hesketh, 2004 ; The Milburn Commission, 2009 ). It appears that a consensus has been reached in the relevant literature that there is a bias towards graduates from the higher social classes, but it has been gradually decreasing since 1960 (Bekhradnia, 2003 ; Tight, 2012 ). Nonetheless, despite the fact that, during the last few decades, there has been an improvement in the participation rates for the most vulnerable groups, such as women and ethnic minorities, the inequality is still obvious in some occasions (Greenbank and Hepworth, 2008 ). Machin and Van Reenen ( 1998 ) trace the causes of the under-participation in an intergenerational context, arguing that the positive relationship between parental income and participation rates is apparent even from the secondary school. Likewise, Gorard ( 2008 ) identifies underrepresentation on the previous poor school performance, which leads to early drop-outs in the secondary education, or into poor grades, which do not allow for a place in higher education. Other researchers argue that paradoxically, educational inequality persists even nowadays, albeit the policy orientation worldwide towards the widening of higher education participation across all social classes (Burke, 2012 ; Bathmaker et al., 2013 ).

There are different aspects on the purpose of higher education, which particularly, under the context of the ongoing economic uncertainty, gain some recognition and greater respect from academics and policy-makers. Lorenz ( 2006 ) notes that the employability agenda, which is constantly promoted within higher education institutions lately, cannot stand as a sustainable rationale in a diverse global environment. This harmonisation and standardisation of higher education creates permanent winners and losers, centralising all the gains, monetary and non-monetary, towards the most dominant countries, particularly towards Anglo-phone countries and specific industries and therefore social inequalities increase between as well as within countries. Some scholars call this phenomenon as Englishization (Coleman, 2006 ; Phillipson, 2009 ).

Tomusk ( 2002 , 2004 ) positioned education within the general framework of the recent institutional changes and the rapid rise of the short-term profits of the financial global capital. Specifically, the author sees World Bank as a transnational organisation. Given this, any loan agreement planned from the World Bank regarding higher education reforms in developing countries, has the same ultimate, but tacit, goal, which is the continuous rise of the national debt and in turn, the vitiation of national fiscal and monetary policies, in order the human resources of the so called “recipient countries”, to be redistributed in favour of a transnational dominant class.

Hunter ( 2013 ) places the debate under a broader political framework, juxtaposing neo-liberalism with the trends formulated by the OECD. She concludes that OECD is a very complex and multi-vocal organisation and when it comes to higher education policy suggestions, there is not any clear trend, especially towards neo-liberalism. This does not mean that economic thinking is not dominant within the OECD. This is, in fact, OECD’s main concern and it is clear to all. Hunter ( 2013 : 15–16) accordingly states that:

“Some may feel offended by the vocational and economic foci in OECD discourse. Many would like to see HE held up for “higher” ideals. However, it is fair for OECD to be concerned with economics. They do not deny that they are primarily an organization concerned with economics. It is up to us, the readers, politicians, scholars, voters, teachers, administrators, and policy makers, to be aware that this is an economic organization and be careful of from whom we get our assumptions”.

Hyslop-Margison ( 2000 ) investigated how the market economy affects higher education in Canada, when international organisations and Canadian business interfere in higher education policy making, under the support of government agencies. He argues that such economy-oriented policies deteriorate curriculum theory and development.

Letizia ( 2013 ) criticises market-oriented reforms, enacted by The Virginia Higher Education Opportunity Act of 2011, placing them within the context of market-driven policies informed by neoliberalism, where social institutions, such as higher education, should be governed by the law of free market. According to Letizia, this will have very negative implications to the humanistic character of education, affecting people’s intellectual and critical thinking, while perpetuating social inequalities.

The term Mcdonaldisation has been also used recently to capture functional similarities and trends in common, between higher education and ordinary commercial businesses. Thus, efficiency, calculability, predictability and maximisation are high priorities in the American and British educational systems and because of their global influence, these characteristics are being expanding worldwide (Hayes and Wynard, 2006 ; Garland, 2008 ; Ritzer, 2010 ).

The notion of Mcdonaldisation is very well explained by Garland ( 2008 , no pagination):

“Mcdonaldisation can be seen as the tendency toward hyper-rationalisation of these same processes, in which each and every task is broken down into its most finite part, and over which the individual performing it has little or no control becoming all by interchangeable. It may be argued that the labour processes involved in advanced technological capitalism increasingly depend on either the handling and processing of information, or provision of services requiring instrumentalised forms of communication and interaction, just as the same “professional” roles frequently consist of largely mechanized, functional tasks requiring a minimum of individual input or initiative, let alone creative or critical thought, a process illustrated in blackly comic by the 1999 film Office Space”.

Realistically, higher education cannot be solely conceptualised by the human capital approach and similar quantitative interpretations, as it has cultural, psychological, idiosyncratic and social implications. Additionally, Hoxby ( 1996 ) argued that policy environment and systems of governance in higher education play a significant role to an individuals’ decision-making process to obtain further education and unfortunately, policy makers regard this aspect as static that can never be transformed.

Lepori and Bonaccorsi ( 2013 ), following Latour and Woolgar’s ( 1979 ) rationale of the high importance of vested interest in scientific endeavours, argue that higher education trends are too complex to be reduced and captured adequately, by the use of economic indicators as related to the labour market. However, the market and money value of higher education should not be neglected, especially in developing countries, as there is evidence that it can help people escape the vicious cycle of poverty and therefore it has a practical and more pragmatic purpose to fulfil (Psacharopoulos and Patrinos, 2004 ). According to World Bank ( 2013 ), education can contribute to a significant decrease of the number of poor people globally and increase social mobility when it manages to provides greater opportunities for children coming from poor families. There are also other studies that do not only focus to strict economic factors, but also to the contribution of educational attainment to fertility and mortality rates as well as to the level of health and the creation of more responsible and participative citizens, bolstering democracy and social justice (Council of Europe, 2004 ; Osler and Starkey, 2006 ; Cogan and Derricott, 2014 ).

Mountford-Zimdars and Sabbagh ( 2013 ), analysing the British Social Attitudes (BSA) survey, offer a plausible explanation on why the widening of participation in higher education is not that easy to be implemented politically, in the contemporary western democracies. The majority of the people, who have benefited from higher educational attainment in monetary and non-monetary terms, are reluctant to support the openness of higher education to a broader population. On the contrary, those that did not succeed or never tried to secure a place in a higher education institute, are very supportive of this idea. This clash of interests creates a political perplexity, making the process of policy-making rather dubious. Therefore, the apparent paradox of the increase in higher educational attainment, along with a stable rate in educational inequalities, does not seem that strange when vested interests of certain groups are taken into account.

Moreover, the decision for someone to undertake higher education is not solely influenced by its added value in the labour market. Since an individual is exposed to different experiences and influences, strategic decisions can easily change, especially when these are taken from adolescents or individuals in their early stages of their adulthood. Given this, perceptions and preferences do change with ageing and this is why there are some individuals who drop out from university, others who choose radical shifts in their career or others who return to education after having worked in the labour market for many years and in different types of jobs.

Higher education has expanded rapidly after WWII. The advent of new technologies dictates the enhancement of people’s talents and skills and the creation of a knowledge-based-economy, which in turn, demands for even more high-skilled workers. Policy aims for higher education in the western world is undoubtedly focusing on its diffusion to a broader population. This expansion is seen as a policy instrument to alleviate social and income inequalities. However, the implementation of such policies has been proved extremely difficult in practise, mainly because of existent conflicted interests between groups of people, but also because of its institutional incapacity to target the most vulnerable. Nonetheless, it has been observed a constant marketization process in higher education, making it less accessible to people from poor economic background. Concerns on the persistence of policy-makers to focus primarily on the economic values of higher education have been increasingly expressed, as strict economic reasoning in higher education contradicts with political claims for its continuing expansion.

On the other hand, there are studies arguing that the instrumental model can make the transition of graduates into the labour market smoother. Such studies are placed under the mainstream economics framework and are also informed by policy decisions implemented by the Bologna Process, where competitiveness, harmonisation and employability are the main policy axes. The Bologna Process and various other institutions (e.g., the EU, World Bank, OECD) have provided a framework under which higher education can be seen as inextricably linked with labour market dynamics; however, the intrinsic notion of higher education is treated more as a nuisance and less as a vital component on this framework. Nevertheless, this makes the job competition between graduates much more intense and also creates very negative implications for those that remain with low qualifications as they effectively become socially and economically marginalised.

The purpose of higher education and its role in modern societies remains a heated philosophical debate, with strong practical and policy implications. This article sheds more light to this debate by presenting a synthetic narrative of the relevant literature, which can be used as a basis for future theoretical and empirical research in understanding contemporary trends in higher education as interwoven with the evolutions in the broader socio-economic sphere. Specifically, two conflicting theoretical stances have been discussed. The mainstream view primarily aims to assist individuals to increase their income and their relative position in the labour market. On the other hand, the intrinsic notion focus on understanding its purpose under ontological and epistemological considerations. Under this conceptual framework, the enhancement of individual creativity and emancipation are in conflict with the contemporary institutional settings related to power, dominance and economic reasoning. This conflict can influence people’s perceptions on the purpose of higher education, which can in turn perpetuate or otherwise revolutionise social relations and roles.

However, even if the two theoretical stances presented are regarded as contradictory, this article argues that, in practical terms, they can be better seen as complementing each other. From one hand, using an instrumental perspective, an increase in higher education participation, focusing particularly on the most vulnerable and deprived members of society, can alleviate problems of income and social inequalities. The instrumental view of education has a very important role to play if focused on lower-income social classes, as it can become the mechanism towards the alleviation of income inequalities. On the other hand, apart from the pecuniary, there are also other non-pecuniary benefits associated with this, such as the improvement in the fertility and mortality and general health level rates or the boost of active democracy and citizenship even within workplaces and therefore a shift of higher education towards its intrinsic purposes is also needed. (Bowles and Gintis, 2002 ; Council of Europe, 2004 ; Brennan, 2004 ; Brown and Lauder, 2006 ; Wolff and Barsamian, 2012 ).

Summing up, education is not a simply just another market process. It is not just an institution that supply graduates as products that have some predetermined value in the labour market. Consequently, acquired knowledge in education verified by college degrees is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for the labour market to create appropriate jobs, where graduates utilise and expand this knowledge. In fact, the increasing costs of higher education, mostly due to its internationalisation, and the rising levels of job mismatch create a rather gloomy picture of the current economic environment, which seems to preserve the well-paid jobs mostly to those from a certain socio-economic class background. At the same time, poor students are vastly disadvantaged to more wealthy ones, considering the huge differences in terms of higher as well as their past education, their parent’s education and also certain elitist traditions that work towards perpetuating power relations in favour of the dominant class.

As Castoriadis ( 1997 ) notes, it is impossible to separate education from its social context. We, as human beings, acquire knowledge, in the sense of what Castoriadis calls paideia , from the day we born until the day we die. We are being constantly developed and transformed along with the social transformations that happen around us. The transformation on the individual is in constant interaction with social transformations, where no cause and effect exists. Formal schooling has become nowadays an apathetic task where no real engagement with learning happens, while its major components such as educators, families and students are largely disconnected with each other. Educators, cynically execute the teaching task that a curriculum dictates each time, families’ main concern is to attach a market value to their children educational attainment, “labelling” them with a credential that the labour market allegedly desires, while students pay attention to anything else apart from the knowledge they get per se and therefore they care too little for its quality and also its practical use.

To tackle the ever-growing social inequalities due to the narrow economic policy making in education, we need a radical shift towards policies that are informed from Freire’s problem-posing education and Sen’s capabilities approach, get insights in terms of structure from Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological systems theory, while giving context according to the Bildung tradition also acknowledging that education, apart from instrument, is a vehicle towards liberation, cultural realisation as well as social transformation. In practical terms, real-world examples from Finland or Germany can be used, which policy makers from around the world should start paying more attention to, moving away from narrow and sterile instrumentalism that has spectacularly failed to tackle social inequalities.

In the context of a modern world where monetary costs and benefits are the basis of policy arguments, a massification and broader diffusion of higher education to a much broader population implies marketisation and commercialisation of its purpose and in turn its inclusion on an economy-oriented model where knowledge, skills, curriculum and academic credentials inevitably presuppose a money-value and have a financial purpose to fulfil. The policy trends towards an economy-based-knowledge, through a strict instrumental reasoning, rather than the alleged knowledge-based-economy seems to persist and prevail, albeit its poor performance on alleviating income and social inequalities. Yet, in a global context of a prolonged economic stagnation and a continuous deterioration of society’s democratic reflexes, a shift towards a model, where knowledge is not subdued to economic reasoning, can inform a new societal paradigm of a genuine knowledge-based-economy, where economy would become a means rather than an ultimate goal for human development and social progress.

Data availability

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

For example, Confucian tradition is very rich, when it comes to education and human development. It is indeed very interesting to see how the basic principles of Confucian education, such as humanism, harmony and hierarchy, has been transformed through time and especially after the change in China’s economic model by Den Xiaoping’s reforms towards a more open economic system and along this a more business-oriented and globalised educational system. Perhaps the Chinese tradition in education, which mainly regards education as a route to social status and material success based on merit and constant examination can explain why the human capital theory is more applicable. On the other hand, additional notions in the Confucian tradition that education should be open to all, irrespective of the social class each person belongs to (apart perhaps from women and servants that were rather considered as human beings with limited social rights), its focus on ethics and its purpose to prepare efficient and loyal practitioners for the government introduces an apparent paradox with human capital theory but not necessarily with the instrumental view of education. This contradiction deserves to be appropriately and thoroughly examined in a separate analysis before it is contrasted to the Western tradition. For this reason the current research focuses only on the Western world leaving the comparison analysis with educational traditions found around the world, among them the Confucian tradition, as a task that will be conducted in the near future.

The use of capital in Bourdieu is criticised by a stream of social science scholars as rather promiscuous and unfortunate (Goldthorpe, 2007 ). They argue that a paradox here is apparent as in English linguistic etymological terms, the word capital implies, if not presupposes market activity. The same time Bourdieu criticises Becker’s human capital tradition as solely market-driven and a tacit way where the ruling class maintain their power through universities and other institutions. Waters ( 2012 ) argue that the use of the term “capital” in both Becker’s and Bourdieu’s writings is unfortunate, while both use the term to mean different things. Bourdieu’s understanding on the nature of “habitus” is a much more applicable term to explain the social role of education systems. Habitus is not capital, even if there is constant interaction between the two. Becker on the other hand, seem to neglect social and cultural capital as well as Bourdieu’s notion of habitus, which in turn is about the reproduction of society and power relations by universities and other institutions.

Some might have valid ontological objections on this, in terms of the purpose of philosophy as a whole; however the concept of Bildung has given education a role within society that moves away from individualism and the constant pursuit of material objects as ultimate means of well-being.

Apple M (2001) Comparing neo-liberal projects and inequality in education. Comp Educ 37(4):409–423

Article Google Scholar

Aronowitz S (2004) Against schooling: Education and social class. Soc Text 22(2):13–35

Arum R, Roksa J (2011) Academically adrift: Limited learning on college campuses. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL

Google Scholar

Barber M, Donnelly K, Rizvi S, Summers L (2013) An avalanche is coming: Higher education and the revolution ahead. Institute for Public Policy Research, London, p 78

Barnett R (2017) Constructing the university: Towards a social philosophy of higher education. Educ Philos Theory 49(1):78–88

Bathmaker AM, Ingram N, Waller R (2013) Higher education, social class and the mobilisation of capitals: Recognising and playing the game. Br J Sociol Educ 34(5-6):723–743

Becker GS (1964) Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis with special reference to education. National Bureau of Economic Research, New York

Becker GS (1993) Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis with special reference to education, 3rd edn.. National Bureau of Economic Research, Chicago

Book Google Scholar

Bekhradnia B (2003) Widening participation and fair access: An overview of the evidence. Higher Education Policy Institute, London

Bo W (2009) Education as both Inculcation and emancipation [Online] Institute of Social Economy and Culture 1-6, Peking University Education Review. Available at http://www2.hawaii.edu/~pesaconf/zpdfs/30bo.pdf

Bourdieu P (1984) Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste. Cambridge, MA: Harvard university press.

Bourdieu P (1986) The forms of capital. In: Richardson J (ed) Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. Greenwood, Westport, CT, p 241–258

Bourdieu P (1998) Practical reason: On the theory of action. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA.

Bourdieu P (2000) Participant objectivation: Breaching the boundary between anthropology and sociology- How? Lecture on the occasion of the presentation of the Huxley Memorial Medal for 2000. Royal Anthropological Institute, London, 6 Dec

Bowl M (2012) The contribution of further education and sixth-form colleges to widening participation [Online] York: Higher Education Academy. Available at: http://www.heacademy.ac.uk/resources/detail/WP_syntheses/Bowl

Bowles S, Gintis H (2002) Schooling in capitalist America revisited. Sociol Educ 75(1):1–18

Brennan J (ed) (2004) The social role of the contemporary university: contradictions, boundaries and change. In: TenYears on: changing education in a changing world. Center for Higher Education Research and Information, Open University Press, Maidenhead, UK, p 23–54

Bridges D (1992) Enterprise and liberal education. J Philos Educ 26(1):91–98

Bronfenbrenner U (1979) The ecology of human development: experiments by nature and design. Am Psychol 32:513–531

Bronfenbrenner, U (2005). Making human beings human: bioecological perspectives on human development. Sage.

Bronfenbrenner U (2009) The ecology of human development . Harvard university press.

Brown P (2003) The opportunity trap: Education and employment in a global economy. Eur Educ Res J 2(1):141–179

Brown P, Hesketh A (2004) The mismanagement of talent: Employability and jobs in the knowledge economy. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Brown P, Lauder H (2006) “Globalisation, knowledge and the myth of the magnet economy”. Globalisation, Societies and Education 4(1):25–57

Burke PJ (2012) The right to higher education: Beyond widening participation. Routledge, Oxon

Card D, Lemieux T (2001) Can falling supply explain the rising return to college for younger men? A cohort-based analysis”. Q J Econ 116(2):705–746

Article MATH Google Scholar

Castoriadis C (1997) The Castoriadis reader. Blackwell, Oxford

CFE and Edge Hill University (2013) The uses and impact of HEFCE funding for widening participation. HEFCE, Bristol, http://www.hefce.ac.uk/media/hefce/content/pubs/indirreports/2013/usesandimpactofwpfunding/The%20uses%20and%20impact%20of%20HEFCE%20funding%20for%20widening%20participation.pdf

Chang SS, Stuckler D, Yip P, Gunnell D (2013) Impact of 2008 global economic crisis on suicide: Time trend study in 54 countries. Br Med J 347:1–15

Chapman C, Laird J, Ifill N, KewalRamani A (2011) Trends in High School Dropout and Completion Rates in the United States: 1972-2009 . Compendium Report. NCES 2012-006. National Center for Education Statistics

Coffield F (1999) Breaking the consensus: Lifelong learning and social control. Br Educ Res J 25(4):479–499

Cogan J, Derricott R (eds) (2014) Citizenship for the 21st century: An international perspective on education. Routledge, London

Coleman JA (2006) English-medium teaching in European higher education. Lang Teach 39(1):1–14

Coleman JS (1988) Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am J Sociol 94(Supplement):S95–S120

Collins R (1979) Credential society: Historical sociology of education and stratification. Academic Press, New York

Council of Europe (Ed.) (2004) All European study on education for democratic citizenship policies. Council of Europe Publishing, Strasbourg, http://www.coe.int/t/dg4/education/edc/Source/Resources/Pack/AllEuropeanStudyEDCPolicies_En.pdf

Dall’ Alba G, Barnacle R (2007) An ontological turn for higher education. Stud High Educ 32(6):679–691

Darder A (2003) The critical pedagogy reader. Psychology Press, New York

Diamond A, Walkley L, Scott-Davies S (2011) Global graduates into global leaders. CIHE, London

Dore R (1976) The diploma disease: Education, qualification and development. Allen & Unwin, London

Dore R (1997) Reflections on the diploma disease twenty years later. Assessment in Education 4(1):189–205

Dorling D, Dorling D (2015) Injustice: Why social inequality still persists. Policy Press, Bristol

Douthat RG (ed) (2005) Privilege: Harvard and the education of the ruling class. Hyperion, New York

Durkheim E (1956) Education and Sociology. Free Press, Glencoe, IL

Durkheim E (2006) Education: Its nature and its role. In: Lauder, et al. (Eds) Education, globalisation & social change. Taylor and Francis Ltd, San Francisco, p 76–88

Durst RK (1999) Collision Course: Conflict, Negotiation, and Learning in College Composition. National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL

Entwistle NJ, Peterson ER (2004) Conceptions of learning and knowledge in higher education: Relationships with study behaviour and influences of learning environments. Int J Educ Res 41(6):407–428

Evans K, Hodkinson P, Unwin L (eds) (2004) Working to learn: Transforming learning in the workplace. Routledge, London

Freire P (1970) Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Herder& Herder, New York

Freire P (2009) Pedagogy of the Oppressed 30th Anniversary Eds. Continuum, New York

Ganding LA, Apple M (2002) Can education challenge neoliberalism? The citizen school and the struggle for democracy in Porto Alegre, Brazil. Social Justice 29(4):26–40

Garland C (2008) The McDonaldization of higher education: Notes on the UK experience. Fast Capitalism 4(1). Available at: http://www.uta.edu/huma/agger/fastcapitalism/4_1/garland.html

Giroux H, Myrsiades K (eds) (2001) Beyond the corporate university: Culture and pedagogy in the new millennium. Rowan and Littlefield Publishers, Lanham

Giroux HA (1983) Theory and resistance in education: A pedagogy for the opposition. Bergin & Garvey, South Hadley, MA

Goethe J (2006) The Sorrows of Young Werther. Penguin, UK, (Vol. 10)

Goldthorpe JH (2007) “Cultural Capital”: some critical observation. In: Scherer S, Pollak R, Otte G, Gangl M (eds) From Origin to Destination. Campus, Frankfurt am Main, p 78–101

Gorard S (2008) Who is missing from higher education? Camb J Educ 38(3):421–437

Gouthro PA (2002) Education for sale: At what cost? Lifelong learning and the marketplace. Int J Lifelong Educ 21(4):334–346

Graham G (2013) The university: A critical comparison of three ideal types. In: Sugden R, Valania M, Wilson JR (eds) Leadership and cooperation in academia reflecting on the roles and responsibilities of university faculty and management. Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, Cheltenham, UK, p 1–16

Greenbank P, Hepworth S (2008) Working class students, the career decision-making process: a qualitatitive study. Higher Education Careers Service Unit, Manchester

Haigh M, Clifford VA (2011) Integral vision: A multi-perspective approach to the recognition of graduate attributes. High Educ Res Dev 30(5):573–584

Harvey L (2000) New realities: The relationship between higher education and employment. Tert Educ Manag 6(1):3–17

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Hayes D, Wynard R (eds) (2006) The McDonaldization of higher education, 2nd edn. Bergin and Harvey, Westport, CT

Hayward G, James S (eds) (2004) Balancing the skills equation: Key issues for policy and practice. Policy Press, Bristol

Hegel GWF (1977) The Phenomenology of Spirit. Translated by A. V. Miller. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Heinze T, Knill C (2008) Analysing the differential impact of the Bologna Process: Theoretical considerations on national conditions for international policy convergence. High Educ 56(4):493–510

Heidegger M (1998) Plato’s doctrine of truth. In: McNeill W (ed) Pathmarks. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, p 155–182

Chapter Google Scholar

Herder JG (2002) Herder: Philosophical Writings. Translated and Edited by M. Foster. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Hess FM (2004) Common sense school reform. Palgrave MacMillan, New York

Hoxby CM (1996) How teachers’ unions affect education production. Q J Econ 111(3):671–718

Hunter CP (2013) Shifting themes in OECD country reviews of higher education. High Educ 66(6):707–723