The Rise of Dalit Studies and Its Impact on the Study of India: An Interview with Historian Ramnarayan Rawat

Kritika Agarwal | Jun 6, 2016

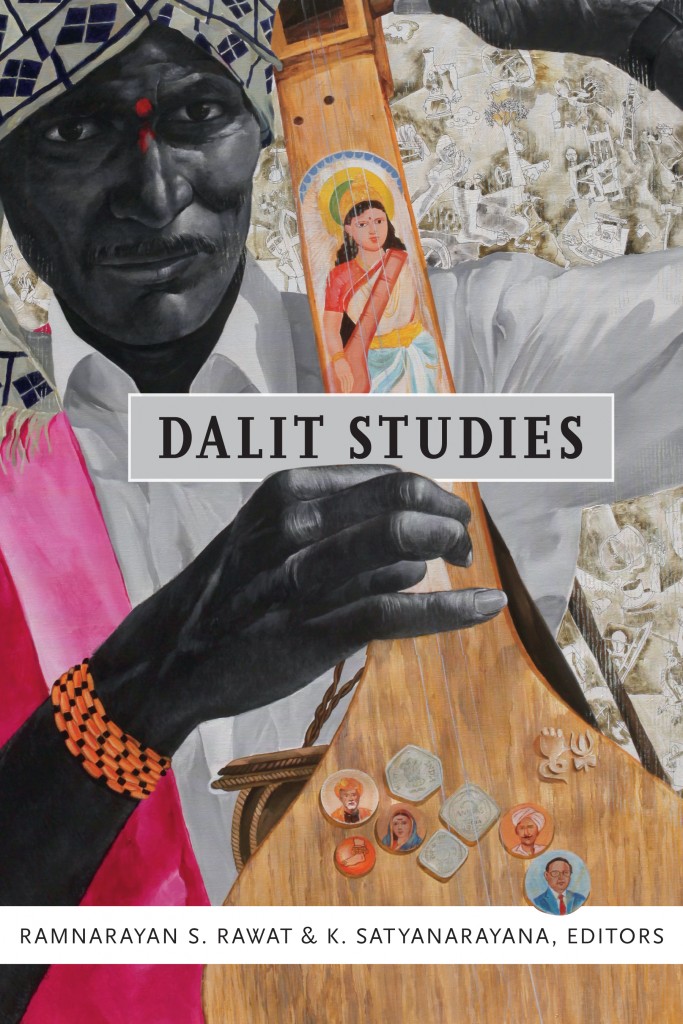

Last month, controversy erupted again in California over the portrayal of the South Asian subcontinent in history textbooks. Among the disputed points was whether schools in California should teach Dalit history and the history of the caste system to students. While the word “Dalit” may ring unfamiliar to most outside the subcontinent, Dalit history is a burgeoning field of study in academia, both in the United States and India alike. We caught up with historian Ramnarayan Rawat (Univ. of Delaware), co-editor of the recently released Dalit Studies (2016), to ask him what Dalit studies is and what the future of the field looks like.

Dalits constitute nearly 17 percent of India’s population—210 million people as per the 2011 census. They are considered untouchable by orthodox Hindus and Hindu theology because of their association in rural areas with impure occupations such as leather work, sanitary work, removing dead animals, and midwifery. In addition, because Dalit communities have been historically segregated, the practice of untouchability has a distinctive spatial dimension. The practice has moral and religious sanction in Hindu theology.

What are the major goals of the field of Dalit history or Dalit studies? What are some of the reasons behind the emergence of Dalit studies as a field of inquiry? The major objective of Dalit studies is to offer new perspectives for the study of India. First, to foreground dignity and humiliation as key ethical categories that have shaped political struggles and ideological agendas in India. Second, Dalit studies historicizes the persistence of caste inequality and discrimination that have acquired new forms in a modern and democratic India. Given these objectives, a key aim of Dalit studies is to recover histories of struggles for human dignity and caste discrimination by highlighting Dalit intellectual and political activism.

There has been a general absence of research into and engagement with the perspectives of 20th-century Dalit intellectuals such as Swami Achhutanand, Bhagya Reddy Varma, Kusuma Dharmanna, and Iyothee Thass. The rise of Dalit studies as a discipline can be located in the transformational political events of the 1990s in India: The greater visibility of Dalit political movements, especially the Bahujan Samaj Party ’s rise to political power in the 1990s and 2000s in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh; the rise of new and visible Dalit movements in southern Indian states such as Tamil Nadu; renewed discussions around caste inequalities and discrimination following the Indian government’s decision to implement recommendations from the Mandal commission report to extend affirmative action to lower caste groups; and the emergence of a new group of Dalit activist/intellectuals in universities across India.

What are the challenges of doing Dalit history, both from theoretical and methodological standpoints? The challenge is to make Dalit agendas and actors visible. This requires innovative approaches and combining anthropological, historical, and literary fields. In my research I have found politically and culturally informed discussions in spatially secluded Dalit neighborhoods to be the most productive. I have found their viewpoints and agendas rarely acknowledged in mainstream academic contexts, and have followed up on them in historical, archival, and literary sources.

For example, many Dalits, considered impure because of their association with occupations such as leather working in their neighborhoods in northern India, told me that historically they have always held land and been peasants. I was able to corroborate these claims in historical registers, which equipped me to think anew about Dalit agendas in the early 20th century. Likewise, Dalit activists and groups have always claimed that they have an ethical commitment to ideas of equality and democratic politics. Dalit owned printing presses in the 1920s published books that addressed these questions and related them to heterodox religious practices in their neighborhoods.

Why should scholars outside of South Asian history pay attention to Dalit history? What sorts of courses do you think would benefit from readings and discussions on Dalit history? Dalit history illustrates and enables connections with global histories of racism and social exclusion. Scholars (and students) will find remarkable parallels on policies and practices that sustain exclusion of Dalits (similar to black people and Burakumins in Japan), and their struggles to seek access to public spaces. For these reasons, courses on race and ethnic studies, Africana studies, black studies, history, anthropology, English/postcolonial studies, literary studies, and area studies can benefit from Dalit histories. Courses that emphasize innovative methodological and theoretical approaches will find Dalit histories useful, especially for graduate students.

In the introduction to your book, Reconsidering Untouchability , you argue that “Dalit perspectives on Indian history have little respect for the framework of colonialism versus nationalism mapped by Hindu-dominated mainstream Indian historiography.” Can you explain what you mean by this and also elaborate on your critique of Indian historiography? In mainstream Indian historiography the framework of colonialism versus nationalism highlights the major contradiction that has shaped the making of modern Indian society. In this conceptual framework, colonialism is regarded as the homogenous and primary form of oppression and exploitation of all Indians. The framework has helped the Hindu nationalist elite to appropriate both history and power in modern India. The historiography centers anti-colonial struggles of the Hindu nationalist elite at the expense of other forms of activism or social concerns. Dalits, tribal groups, and women’s organizations, for example, often responded very differently to the presence of colonial rule in India.

Dalit history demonstrates that the colonial legal regime provided Dalits with mechanisms to claim political and constitutional rights previously denied to them. The colonial state’s legal apparatus, consisting of judicial courts and the police system, allowed Dalit activists and groups to demand access to public spaces and gain employment in new professions, such as the army and state bureaucracy. Dalit activists also considered the practice of untouchability and the persistence of caste hierarchies as crucial questions central to decolonization. Led by B.R. Ambedkar, Dalits urged the British and the Indian National Congress to give them adequate representation in constitutional discussions regarding the transfer of power to Indian representatives and the establishment of a new constitution.

What does the future of Dalit studies look like? What are some of the new trends in the field? Dalit studies has the potential to fundamentally alter the historiographical map of India/South Asia studies. The recent recognition by Indian academia of Ambedkar as a philosopher and social scientist who made important contributions to the study of Indian society and history, the surge in Dalit histories in the last decade all around the academia, especially in the United States, all seem to suggest that a new set of questions are informing research and the study of India.

A key trend in the field is to recover histories of leading Dalit activists or leaders in different regions of India and to explore the nature of activism that emerged there. A second prominent trend, which I have not mentioned so far, is to recognize the distinctive agendas of Dalit feminism. A third emerging trend has been to engage with Dalit literature, in both prose and verse forms, as well as political and autobiographical writings, to understand the cultural and social motivations that have shaped their political activities. A fourth prominent theme is to study Dalit groups’ religious and cultural formations. These four trends draw from, and build on, the work done by scholars prior to the 1990s and foreground the role of Dalit activism.

Can you provide some suggestions for further readings? I provide below a very select reading list, covering a range of topics:

Aloysius, G. Religion as Emancipatory Identity: A Buddhist Movement among the Tamils under Colonialism . New Delhi: New Age International Publishers, 1998.

Ambedkar, B.R. What Congress and Gandhi have done to the Untouchables ? Bombay: Thacker & Co., Ltd., 1945.

Brueck, Laura. Writing Resistance . New York: Columbia University Press, 2014.

Guru, Gopal, ed. Humiliation: Claims and Context . New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Juergensmeyer, Mark. Religion as Social Vision: The Movement against Untouchability in Twentieth-Century Punjab . Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982.

Mohan, P. Sanal. Modernity of Slavery: Struggles against Caste Inequality in Colonial Kerala . New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Moon, Vasant. Growing Up Untouchable in India: A Dalit Autobiography . New York: Rowman &Littlefield Publishers, 2000. First published in Marathi as Vasti , 1995. Translated from the Marathi by Gail Omvedt.

Paik, Shailaja, Dalit Women’s Education in Modern India: Double Discrimination . Routledge, 2014.

Nagaraj, D. R. The Flaming Feet and Other Essays: The Dalit Movement in India . Prithvi Shobhi, ed. Ranikhet: Permanent Black, 2011.

Rao, Anupama, ed. Gender and Caste . New Delhi: Kali for Women, 2003.

Rawat, Ramnarayan and Satyanarayana, K., eds. Dalit Studies . Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016.

Rawat, Ramnarayan. Reconsidering Untouchability: Chamars and Dalit History in North India . Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2011.

Rege, Sharmila. Writing Caste/ Writing Gender: Reading Dalit Women’s Testimonios . New Delhi: Zubaan, 2006.

Satyanarayana, K. and Tharu, Susie, eds. Steel Nibs are Sprouting: New Dalit Writing from South India (Dossier II) . New Delhi: Harper Collins, 2013.

Ramnarayan Rawat teaches at the University of Delaware. He is currently completing a second book, “Parallel Publics: A History of Indian Democracy.” His recent co-edited book, Dalit Studies (2016) , was published by Duke University Press.

This post first appeared on AHA Today .

Tags: AHA Today Asia/Pacific Global History Religious History Social History

The American Historical Association welcomes comments in the discussion area below, at AHA Communities , and in letters to the editor . Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.

In This Section

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Dalit Literature

Introduction.

- Life Writing

- Graphic Novels

- Anthologies

- Sociopolitical Studies

- B. R. Ambedkar, Jotirao Phule, and Dalit Iconography

- Dalits and Religion

- Dalit Cosmopolitanism

- Comparative Studies

- Dalit Literatures: Translation and Reception

- Literature, Language, Aesthetics

- Histories and Archives

- Caste and Gender

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Postmodernism

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Black Atlantic

- Postcolonialism and Digital Humanities

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Dalit Literature by Pramod K. Nayar LAST REVIEWED: 12 January 2021 LAST MODIFIED: 12 January 2021 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780190221911-0101

Dalit Literature is at once the expression of a “Dalit consciousness” about identity (both individual and communal), human rights and human dignity, and the community, as well as the discursive supplement to a ground-level sociopolitical movement that seeks redress for historically persistent oppression and social justice in the present. While its origins are often deemed to be coterminous with the movement dating back to the reformist campaigns in several parts of India during the 19th century, contemporary researchers have found precursors to both the Dalit consciousness and literary expressions in poets and thinkers of earlier eras, such as the saint-poets in the Punjab. Dalit literature’s later development has also run alongside political movements such as the Indian freedom struggle, even as B. R. Ambedkar’s campaign on behalf of what were then called the “depressed classes” intersected, sometimes fractiously, with the Indian National Congress, Mahatma Gandhi, and others in the struggle. Ambedkar’s own voluminous writings and speeches, tracts of various social and reformer organizations, debates, and letters also stimulated the literary. This bibliography includes primary texts in terms of foundational writings by B. R. Ambedkar, Jotirao Phule. and Periyar, followed by select examples of Dalit life writing, fiction, poetry, and anthologies that have brought together some of these texts. Later sections include critical-academic texts that cover some of the contexts, history, and development of Dalit literature. With more poetry, autobiographies, commentaries, anthologies, and compilations of Dalit texts appearing through the 20th century, the foundation for academic studies of the field of Dalit literature were also laid. Contextualizing Dalit texts in many cases, the essays and books listed here represent a wide variety of approaches. The contexts invariably involve the Dalit movement; the campaigns from the late 19th century; the various social, cultural, and political associations; the rise of Ambedkar and his influence; and other subjects. Many link Dalit narratives to other cultural productions, iconography, and practices. Others focus on the intersection of caste and class/political economy and capitalist modernity in the postcolonial state, or caste and patriarchy. And some others, working with Dalit literature from particular languages, offer a history of Dalit literature in that language. The role of this literature in shaping not only political mobilization but also the social imaginary of the Dalit communities and the public sphere are also key components of the protocols of reading and receiving Dalit texts engendered in the academic and cultural discussions around the domain. Aesthetics, politics, genre conventions, influences and the “voice” of resistance, anger, and despair are part of the discussion in many essays. Others offer comparative studies of Dalit texts. Read variously as the literature of protest, sympathy, solidarity, and resistance, Dalit literature thrives in Indian languages, and in multiple forms, although oral narratives and stories that are popular in gatherings and meetings remain largely uncollected. New forms such as the graphic novel have energized the field in recent years.

Dalit Literature: Select Primary Texts

The texts in this section open with the writings of B. R. Ambedkar, Jotirao Phule, and Periyar. These constitute the foundational texts, if one could call them that, of both Dalit sociopolitical movements and Dalit literary productions. The first significant anti-caste critiques are to be found in the work of the 19th-century reformer-educationist Jotirao Phule, and are brought together in Phule 2002 . Ambedkar 2014b includes his key writings on the caste system; the mythography of religion; and political issues such as the question of suffrage, education, and the organization of states. What is extant as autobiography may be found in Ambedkar 2005 , and his most famous critique of the caste system is Ambedkar 2014a . Periyar 2019 is a reprint of Periyar’s major tract on women and caste. Later subsections list important anthologies, fiction, life writing, poetry, and graphic novels.

Ambedkar, B. R. Annihilation of Caste . New annotated ed. New Delhi: Navayana, 2014a.

Ambedkar here presents a refutation of the caste system, drawing on political, economic, and social reasoning. From Hindu myths to Marx and economic relations, Ambedkar unpacks the iniquities and logical inconsistencies in the caste system. He also argues that Hindu reformers may seek political freedom from the British, but they would not allow a reform of religious beliefs or social practices that emerge from those beliefs. Political freedom without social reform, he proposes, is ineffectual.

Ambedkar, B. R. Writings and Speeches . Compiled by Vasant Moon. 17 vols. New Delhi: Ambedkar Foundation, 2014b.

This is the standard reference material for understanding the background to the Dalit movement. Included here are the speeches, books, essays, and journalism on the caste system, the mythography of religion, suffrage and electoral reforms, education, Gandhi-Marxism-Buddhism, the Indian National Congress, the English Constitution, and the Hindu Code Bill, among others. Key texts such as Annihilation of Caste are a part of this set.

Ambedkar, B. R. Autobiographical Notes . New Delhi: Navayana, 2005.

The only autobiography Ambedkar left behind was in the form of these “notes.” This slim volume gives us vignettes and episodes rather than a sustained narrative. It includes the famous visa story, the account of his school life in which he faced sustained discrimination, his return to India from the United States and the caste-based social antagonism that he met on return, among others. Poignant in parts, the Notes offers us glimpses into the contexts of the making of Ambedkar.

Periyar (E. V. Ramaswamy). Why Were Women Enslaved ? Translated by Meena Kandaswamy. Chennai, India: Periyar Self-Respect Propaganda Foundation, 2019.

First published in 1942, Periyar’s tract links caste/religion and gender inequality in India. Remarriage and widowhood are social conditions that contribute to the subjugated status of women. Ancient literary texts such as those of Thiruvalluvar glorified “chastity” and other “slavish concepts” (p. 3). He argues that “there is provision in nature for both sexes to be equal . . . but it has been changed artificially because of men’s selfishness and conspiracy” (p. 11). Later essays examine widowhood, prostitution, and remarriage within exploitative patriarchy.

Phule, Jotirao. Selected Writings . Edited by G. R. Deshpande. New Delhi: Leftword Books, 2002.

This brings together Phule’s key texts: Slavery, The Cultivator’s Whipcord , and the deposition before the Education Commission. In Slavery Phule claims the Brahmins were a race that invaded the subcontinent and enslaved, through the caste system, the aborigine natives, while exploiting the latter’s labor “to sustain . . . their own luxurious lifestyle” (p. 45). Phule argues that Hindu myths compound social differentiation and hierarchization. He discusses caste-based agricultural labor, the British government’s Brahmin employees, and compares the labor of women across castes in The Cultivator’s Whipcord .

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Literary and Critical Theory »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Achebe, Chinua

- Adorno, Theodor

- Aesthetics, Post-Soul

- Affect Studies

- Afrofuturism

- Agamben, Giorgio

- Anzaldúa, Gloria E.

- Apel, Karl-Otto

- Appadurai, Arjun

- Badiou, Alain

- Baudrillard, Jean

- Belsey, Catherine

- Benjamin, Walter

- Bettelheim, Bruno

- Bhabha, Homi K.

- Biopower, Biopolitics and

- Blanchot, Maurice

- Bloom, Harold

- Bourdieu, Pierre

- Brecht, Bertolt

- Brooks, Cleanth

- Caputo, John D.

- Chakrabarty, Dipesh

- Conversation Analysis

- Cosmopolitanism

- Creolization/Créolité

- Crip Theory

- Critical Theory

- Cultural Materialism

- de Certeau, Michel

- de Man, Paul

- de Saussure, Ferdinand

- Deconstruction

- Deleuze, Gilles

- Derrida, Jacques

- Dollimore, Jonathan

- Du Bois, W.E.B.

- Eagleton, Terry

- Eco, Umberto

- Ecocriticism

- English Colonial Discourse and India

- Environmental Ethics

- Fanon, Frantz

- Feminism, Transnational

- Foucault, Michel

- Frankfurt School

- Freud, Sigmund

- Frye, Northrop

- Genet, Jean

- Girard, René

- Global South

- Goldberg, Jonathan

- Gramsci, Antonio

- Greimas, Algirdas Julien

- Grief and Comparative Literature

- Guattari, Félix

- Habermas, Jürgen

- Haraway, Donna J.

- Hartman, Geoffrey

- Hawkes, Terence

- Hemispheric Studies

- Hermeneutics

- Hillis-Miller, J.

- Holocaust Literature

- Human Rights and Literature

- Humanitarian Fiction

- Hutcheon, Linda

- Žižek, Slavoj

- Imperial Masculinity

- Irigaray, Luce

- Jameson, Fredric

- JanMohamed, Abdul R.

- Johnson, Barbara

- Kagame, Alexis

- Kolodny, Annette

- Kristeva, Julia

- Lacan, Jacques

- Laclau, Ernesto

- Lacoue-Labarthe, Philippe

- Laplanche, Jean

- Leavis, F. R.

- Levinas, Emmanuel

- Levi-Strauss, Claude

- Literature, Dalit

- Lonergan, Bernard

- Lotman, Jurij

- Lukács, Georg

- Lyotard, Jean-François

- Metz, Christian

- Morrison, Toni

- Mouffe, Chantal

- Nancy, Jean-Luc

- Neo-Slave Narratives

- New Historicism

- New Materialism

- Partition Literature

- Peirce, Charles Sanders

- Philosophy of Theater, The

- Postcolonial Theory

- Posthumanism

- Post-Structuralism

- Psychoanalytic Theory

- Queer Medieval

- Race and Disability

- Rancière, Jacques

- Ransom, John Crowe

- Reader Response Theory

- Rich, Adrienne

- Richards, I. A.

- Ronell, Avital

- Rosenblatt, Louse

- Said, Edward

- Settler Colonialism

- Socialist/Marxist Feminism

- Stiegler, Bernard

- Structuralism

- Theatre of the Absurd

- Thing Theory

- Tolstoy, Leo

- Tomashevsky, Boris

- Translation

- Transnationalism in Postcolonial and Subaltern Studies

- Virilio, Paul

- Warren, Robert Penn

- White, Hayden

- Wittig, Monique

- World Literature

- Zimmerman, Bonnie

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|81.177.182.174]

- 81.177.182.174

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Options

- Why Submit?

- About English

- About the English Association

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Terms and Conditions

- Publishers' Books for Review

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

View from here – english in india: the rise of dalit and ne literature.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Nandana Dutta, View from Here – English in India: The Rise of Dalit and NE Literature, English: Journal of the English Association , Volume 67, Issue 258, Autumn 2018, Pages 201–208, https://doi.org/10.1093/english/efy025

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This article argues that transactions between the English text and local conditions are an important aspect of developments in English in India determining interpretations in teaching and research. Texts emerging from contemporary conditions feature in courses, with one of the most significant of these transactions resulting in the incorporation of Dalit and minority literatures into English Studies. Perceived as an instrument of empowerment by Indians almost from the time it was introduced, English has never quite lost this aspect of its role – and even as the discipline has taken note of global expansions in the field through theory and the incorporation of new areas, it has gradually acquired a strong national/regional flavour through the incorporation of texts that have emerged out of struggles for visibility and voice by marginal groups. The rise of Dalit and Northeast Indian English literature and their incorporation into English syllabi are two examples of this trend.

While trying to capture a sense of the current status of the discipline of English as it is taught at college and university level in India, and brought up short by the impossible task of pulling together the many ways in which the discipline exists here, I realized that perhaps the only common thread that runs through its multiple practices is the growing interest in Dalit writing from all over the country and writings (mostly in English) from the north eastern states of India (or NE as it is commonly known). The bird’s eye view would reveal literatures from these two sites – the Dalit and the NE – making the most significant impact on the discipline by their hospitality to current developments in theory, their strong ideological moorings in otherness of caste and tribe respectively, and, perhaps most importantly, their accessibility as areas of study.

‘English in India’ as a meta-issue has been the subject of study ever since Gauri Viswanathan’s Masks of Conquest demonstrated how English Literature was used by the British as a tool of subject construction and governance. While the goals and influence of English (language and literary study) changed with Independence in 1947, interest in what can be achieved through it has continued to grow and change. A Google search would show many essays and books that describe and analyse ‘English in India’ with varying degrees of success and most often with an emphasis on the language. English is taught in schools across the country, functions as the language of communication among the educated, is the language of higher education, and is often used as an official language in administration and in the courts. Simultaneously, Indian Writing in English (IWE) has become an exciting new addition to the global English Literature corpus. And English continues to be part of subject construction and empowerment exercises. But what is the nature of the discipline in contemporary India? An overview would show the presence of English in the above-mentioned ways as a significant context for developments in the discipline, while transactions between the English text and local conditions appear to affect interpretations in teaching and research. Texts emerging from contemporary conditions feature in courses, with one of the most significant of these transactions resulting in the incorporation of Dalit and minority literatures into English Studies. Perceived as an instrument of empowerment by Indians almost from the time it was introduced, English has never quite lost this aspect of its role – and even as the discipline has taken note of global expansions in the field through theory and the incorporation of new areas, it has gradually acquired a strong national/regional flavour that has helped turn the very real disadvantages of practising the discipline outside of its primary Anglo-American sites of production into a source of strength. And since higher education is administered from the University Grants Commission (UGC) through a combination of suggestion and direction, model curricula periodically issued by it are often a barometer of change with Dalit, regional, minority, Indian English, and classical literature being highlighted in such advisories at different times.

Over the last seven or eight decades the primarily British-English syllabus inherited from colonial education has expanded to include literatures in English from other parts of the world and India, and has come to terms with offering a percentage of translated texts from European and Latin American literatures and from some of the major Indian literary traditions. Today it is a combination of a historically inherited core British literature component supplemented in different universities with American, African, Australian, Canadian, South Asian, and Caribbean texts and elective courses (these national literatures do not always feature as full courses but individual texts often appear in courses on Women’s Writing, literature and environment, post-humanism and literature, graphic novels, etc.). Besides, newer texts and areas emerging in the wake of India’s national and regional politics, social concerns, and discourses about public events have gradually begun to appear.

Such new texts from socio-economic and political conditions and events stemming from churning amongst the many racial, class, and caste components in India’s tradition-bound social fabric have helped to evolve reading strategies that are directed at critiquing the domains from which they have emerged even as they have contributed to the formation of new critical terminologies and themes. The UGC’s curricular suggestions have facilitated incorporation of region and language specific content. So the English syllabus at a university in the north east of India would have English and translated texts from Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Nagaland, Mizoram, and Tripura (available from reputed publishers at local booksellers). A university in West Bengal might have courses on Bengali Dalit writing (both Jadavpur University and West Bengal State University have individual faculty offering such courses). A central university (like Hyderabad, Delhi, or Jawaharlal Nehru University [JNU]) with a different kind of ethnic composition and cultural politics might have courses on both Dalit and writing from the NE states on offer or encourage research in these areas. This scene, with obvious regional modifications, is repeated in universities all over the country.

Many dimensions of English are apparent in various parts of the country (regional variations emerging from racial, ethnic, linguistic and cultural conditions), and English is made to bear the weight of different expectations. Debates over whether students should study Indian writing in English or continue to read the British and American writers were common at one time and, we continue to argue whether Shakespeare (and other early writers) should be taught in general courses in English and whether science students in their compulsory English paper should read literary classics or science writings, or should be prescribed Indian short stories and poems in original English or in English translation from Indian languages. Many of these concerns come out of an interpretation/understanding of contemporary India, especially about disparities in education and wealth, about social class, caste and gender discriminations, and the need to provide education that will help ameliorate such problems.

The ‘politics of English literature as a colonial phenomenon’ has long been displaced as a way of thinking about the discipline and the language even as newer strategic uses have been regularly reinvented. That earlier view is usually taken for granted as part of the history of English in India but to think of current practice is to acknowledge how deeply immersed English has become in the Indian everyday, which includes the socio-political changes going on in post-Independence India, the tone and rhetoric of public discourse, and everyday events that catch news headlines – acts of corruption, violence, multi-ethnic Indian classrooms, gender and ethnic discrimination – all of which quickens English language usage and sharpens interpretation of literary representation. In fact, one eminent English teacher narrates his own experience of teaching Hemingway’s ‘Hills like White Elephants’ through processes of translation in a multi-ethnic classroom and discovers what students might learn: ‘readers of “Hills” in languages other than English open up other worlds where their selves are relocated and discovered. No one is perfectly at home or elsewhere in reading such stories as “Hills,” a discovery only a translation, however imperfect, can teach them’. 1 Chandran’s essay, one of many others that he has written on the experience of teaching English in India, suggests that young readers bring to the classroom and to the specific texts cultural experiences drawn from the reality of their lives in contemporary India that determine how they are likely to respond to the English text.

The complex reception and strategic hospitality accorded to the English text are the result of the urgency in students and researchers to make their discipline more responsive and relevant. This urgency has gradually begun to appear as the profile of the English classroom, determined by a combination of merit and social welfare schemes of reservation (the reservation of seats for constitutionally defined disadvantaged groups at all levels and going up to recruitment of faculty), has become more and more complex, and has begun to influence text selection and modes of classroom practice. The ideal of social upliftment through English is not new. 2 It has been a part of the expectations attendant upon knowledge of the English language and has been one of the tacit goals of English literary study at the university during its long history in India. But the growing self-consciousness, protests, and demands for visibility and justice on the part of India’s variously disadvantaged communities have ensured a path-breaking shift in Indian society and English has frequently been the engine driving this movement even as it has itself felt the impact of the upheaval.

For the discipline the shift was initially visible in MPhil and PhD research and in projects funded by the UGC 3 and has been the result of a number of negative and positive factors. The negatives include the impossibly large numbers coming into higher education institutions to study for BA and MA degrees and often going onto research degrees (with that nth PhD dissertation based on a superficial reading of a chosen author); uncertain competence in core English literature; and problems of access to primary materials on British and other English language authors. Among the positives are the alternative and local language histories of the canonical English text (as it came to be translated and circulated in one or other of the many literary cultures); theoretical engagement in the global culture of the discipline with issues of trauma, violence, otherness, and the body facilitating the incorporation of texts from Dalit and tribal experience and from Indian experiences of Partition, the Emergency, the Bhopal Gas Tragedy, etc.; and contemporary events that have made it impossible to insulate the English text from its moment of reception (for example, frequent events of rape and honour killings occurring in the still heavily feudal societies in many parts of India have often served as prisms to refract the representation of interpersonal violence in the English text). Literatures representing and making visible these experiences are also invested with the goal of empowerment and social development that runs through Indian higher education policy, even as they speak to ideological associations (and identity issues) of communities. It is possible to identify two kinds of responses in this situation – one in the inclusion of actual new texts and fields of study drawn from India’s current socio-political and economic conditions/crises; and a second in readings of the canonical English text alongside radical new texts (the English text now seems closer even as it allows the event to be seen more sharply and critically).

So, from being a tool in British colonial hands it has now metamorphosed into a strategic tool in the hands of Indian students and researchers of the discipline. It has been progressively Indianized – through the admission of new texts from hitherto ignored and invisible areas of culture, through comparative work, and in a turn to Indian aesthetics and classic Indian texts. The most recent (2015) UGC model curriculum for the BA course starts off with a paper on Indian Classical Literature that includes Kalidasa’s Shakuntala, Sudraka’s Mrcchakatika, ‘The Book of Banci’ from Adigal’s Cilappatikaram: The Tale of an Anklet and several sections from the Mahabharata while among suggested readings is Bharata’s Natyashastra – all of which would earlier only have been referred to in passing in the classroom, if at all. 4

The interest in politically charged work has accompanied the protest movement of the Dalit Panthers and has created serious readership for Dalit autobiographies and poetry and fiction on Dalit experience. Autobiographical novels like Karukku by Bama and Ittibritte Chandal Jibon by Manoranjan Byapari, autobiographies by Baby Kamble ( Jina Amucha ) and Daya Pawar ( Baluta ), and the powerful poetry of Namdeo Dhasal (to name a random handful of representative Dalit texts in Tamil, Marathi, and Bangla, all available in English translation) now feature in syllabi across the country. The emergence of Dalit consciousness is a pan-Indian phenomenon and its powerful discourse of otherness has led to discovery of similar literatures in regions earlier thought to be devoid of Dalit groups. 5

Dalit literature finding a place in English curricula has been the result of much of this literature being either written in English or being quickly translated into English. The role of Katha and Sahitya Akademi in supporting translations from the literary traditions of other languages, the rise of new publishers and local presses, as well as the changed policy on translations of big publishing houses like OUP and Penguin, has been largely responsible for the availability of this literature. Publishing houses that have begun to specialize in Dalit writing are identified by Jaya Bhattacharji Rose as Macmillan India ( Karukku was brought out by them), Orient Longman/OBS, OUP India, Zubaan, Navayana, Adivaani, Speaking Tiger, and Penguin Random House. 6 Besides these there are smaller presses throughout India publishing minority and Dalit literature. The case of literature in English from the ‘North East’ is similar, with visibility and circulation being achieved because of the interest shown by the same publishers.

Recently, I was at a workshop on Translation organized by the English Department of West Bengal State University (WBSC). The focus was on translations of Bangla Dalit writings. The overall ambience of the workshop was distinctly Bengali with workshop participants (comprising of translators who were expected to use the three days of the workshop to fine tune their translations through interactions with the writers present and with one another) and invited Resource Persons (mainly senior academics who were expected to use their own experience of translation to comment on the problems brought up by the participant-translators and set them against current positions in the field of translation studies) being asked to use English, Bangla, and Hindi in their presentations and interventions. Several of the writers whose works had been or were being translated were present along with their translators, even as the workshop identified new writings under this category. Since there was no Dalit literature in my region (comprised of the eight states of India’s northeast), the example I gave was of a similar translation context. This was a project that the English Department of my university had carried out in 2000–2001 which involved the collection of folk tales from several tribal languages of Assam and their translation into English. The project was titled ‘Representation of Women in the Folk Narratives of Assam’ and the process of collection from oral sources and already existing published versions in Assamese translation revealed two interesting features: one was a desire for visibility on the part of communities/groups marginalized by a dominant literary culture – and hence the willingness to be translated into English; the second was the mediatory role played by departments of English in this politics of visibility, a role that has elements of social responsibility, genuine desire to make a rich vernacular literature available to a larger readership, and perhaps most crucially the need to reinvent or at least reenergize the discipline and redefine the place of the Indian academic within this discipline.

The other significant surge of interest has been in literature produced in the eight states of the region known collectively as ‘the North East’ (much of it in English, though literature in the Assamese language has a long history and powerful presence). This literature has successfully articulated the region’s historical marginalization, its cultural and ethnic distinctiveness, its contemporary politics of identity, and accompanying insurgencies and violence, even as the conditions that produced this literature have provided insight into issues of power and powerlessness, and of processes of othering in social and political sites. The experience of alienation, misrepresentation, and political neglect of the NE has been long drawn out and persistent and its perceived and real marginalization has been frequently represented in its literature; and since much of it has been in English or is available in English translation this literature has entered syllabuses without too much resistance.

These two areas of experience have led to hitherto unimaginable representations of cruelties; of bodily oppression and mental agonies; of disgust, shame and revulsion, strong resistance, and critiques of historical persecution. The struggle to find voice and expression has helped refurbish the critical apparatus of writers and critics. Questions of space, body, and otherness have become the stuff of critical language, and students and teachers of English literature have been quick to make the connection between English texts and Dalit and NE literature and allow the insights gained to influence approaches to otherness, and social oppression in the English text.

An example of the kind of thing that happens in the contemporary classroom in India should give a sense of these shifts. The classroom at my university has students coming from different ethnic groups, from rural and urban backgrounds, often with little or no previous exposure to English literature before they enter the BA programme. The challenge is to find a point where we can converse and use the familiar to introduce the strange. The entry point for them is often life in the region, and their access to the discourse about the region made up of identity, neglect, invisibility, and marginalization has both colonial and contemporary resonances. When faced with a text like The Merchant of Venice (one of the most popular and featuring frequently in syllabi), the student’s sympathy for Shylock is immediate. While they enjoy the twists and turns of the plot and readily mouth critical platitudes derived usually these days from online notes, their response to Shylock is experiential and therefore more engaged. With a little steering into the social dynamics of the play they quickly see the way the majority Christian community treats the minority Jewish community – drawing on their own sensitivity to the treatment NE students receive when they go to study or work in metropolises like Delhi and face discrimination and violence from landlords and neighbours or randomly on streets because of different food habits, dress, and supposedly bohemian lifestyles.

Contextual elements as part of literary-critical concerns decide themes of research, setting up evaluative schema that address and critique existing frames for reading that have their origin in other contexts (for example, Partition violence or Indian representations of violence and trauma might help to critique migration writing as well as the literature of the Holocaust or 9/11). The need to speak to the specific classroom – and this varies across India – the importance of taking note of current events and social concerns and registering these as relevant to the English classroom, are also part of keeping the discipline relevant.

While it is impossible to generalize, the blend of canonical and local elements found in the university English classroom today points to a dual urge at work in the way English is developing – one that looks both outward and inward. This is the empowerment that the discipline’s practitioners have perhaps been seeking ever since it was introduced and it looks forward to what might very well be an enabling indigenous strand in English Studies in India alongside developments in keeping with its global status.

K. Narayana Chandran, ‘Being Elsewhere: “Hills Like White Elephants,” Translation, and an Indian Classroom’, Pedagogy, 16.3 (2016), 381–92 (p. 391).

Gyanendra Pandey writes of the Dalit relationship to English in ‘Dreaming in English: Challenges of Nationhood and Democracy’, Economic and Political Weekly , LI.16 (2016), 56–62.

See the present author’s essay on ‘The Politics of English in India’, Australian Literary Studies , 28.1–2 (2013), 84–97.

See < https://www.ugc.ac.in/pdfnews/5430486_B.A.-Hons-English.pdf > [accessed 20 March 2018].

A brief overview of Dalit history and marginalization may be had at Palak Mathur and Jessica Singh, ‘Minorities in India: Dalits’ < https://palakmathur.wordpress.com > [accessed 14 February 2018, 11:30].

Jaya Bhattacharji Rose, ‘Dalit Literature in English’ (4 May 2016) < www.jayabhattacharjirose.com > [accessed 14 February 2018, 11:23].

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Contact the English Association

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1756-1124

- Print ISSN 0013-8215

- Copyright © 2024 The English Association

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Understanding dalit literature: An alternative Research methodology

Related Papers

Psychology and Education Journal

Revathi Ponnudurai Asst.Prof, English Vel Tech University, Chennai

In this modern biosphere there is one form of writing which still thrives on being dissimilar, from the idea of what the history had portrayed about the past for centuries. As per layperson&#39;sempathetic, history is whatsoeveroccurred in former or past. To our astonishment, in a negative inference someone who wrote history has chosen only the certain aspects of past and not all that happened in a country. It means, it is interpreted only for a distinct group of audience. According to Herman Northrop Fry, a Canadian literary critic &#39;emplotment&#39; acts a criticalpart in organizing a past narrative. Now, time has come to not only to know the past life of kings and queens, conquerors, battles, fall of territories, rise of empires, rich culture, religion, hegemony but also to know about the life of ordinary peasants, traders, fighters, marginalised group etc., Generally, mainstream literature has an aforementioned of major written and oral traditions from ancient times,these writers depend on this. However, the marginalised literature needs to generateapeculiarmetaphysical base. This article does not talk about the scuffle between impoverishedand well-to-do but the skirmish seen from the perspective of the lower caste, the marginals, the minorities, the subalterns through the autobiographies of marginalised writers.

Galaxy: International Multidisciplinary Research journal

Dr. Anju Bala

The term ‘Dalit’ is synonymous with poor, exploited, oppressed and needy people. There is no universally acclaimed concept about the origin of Indian caste system. In every civilized society, there are some types of inequalities that lead to social discrimination. And in India, it comes in the garb of ‘Casteism’. The discourses catering to the gentry tastes did not include the subaltern literary voices of the tribals, Dalits and other minority people. The dalits are deprived of their fundamental rights of education, possession of assets and right to equality. Thus Dalit Literature emerges to voice for all those oppressed, exploited and marginalized communities who endured this social inequality and exploitation for so long. The major concern of Dalit Literature is the emancipation of Dalits from this ageless bondage of slavery. Dalits use their writings as a weapon to vent out their anger against the social hierarchy which is responsible for their degradation. After a so long slumber now, they have become conscious about their identity as a human being. This Dalit consciousness and self-realization about their identity has been centrally focused in various vibrant and multifarious creative writings and is also widely applauded in the works of Mahasweta Devi, Bama, Arjun Dangle, D. Gopi and in many more. The anguish represented by the Dalit writers is not that of an individual but of the whole outcast society. The primary concern of present paper is to show how Dalit writers shatter the silence surrounding the unheard exploitation of Dalits in our country in their writings? And how Dalit Literature has become a vehicle of explosion of these muffled voices. The paper makes an attempt to comprehend the vision and voice of the Dalits and their journey from voiceless and passive objects of history to self-conscious subject. The paper will also make a study of the reasons behind the development of Dalit Literature with its consequences on our society, social condition of Dalit in India and how they write their own history. Keywords: Self-realization, Identity, Exploitation, Caste, Subaltern

African - British Journals

Disha Mondal

Autobiography has remained a significant segment of Dalit literature since nineteen hundred and sixties. Dalit literature has emerged through the Dalit movement in Maharashtra.It has been a favorite genre with Dalit writers. This paper seeks to analyse Omprakash Valmiki's Joothan: A Dalit's Life (2003), Sarankumar Limbale's The Outcaste: Akkarmasi (2007), and Bama's Karukku (2001). In these autobiographies, one finds a complete representation of the self and its problems. Although autobiography is a European genre, concerned with the representation of the self, Dalit autobiography is strikingly different from the European models in that it makes "self" only a locus for representing the social reality. In other words, in Dalit autobiography the focus is not on "self" but "Dalit community". Dalit autobiography is not just of a remembrance of things past, but a shaping and structuring of them to help one to understand one's life and the society. The act of narration involves the political act of self-assertion and self creation. So, these are the public functions of Dalit autobiographies. On the other hand, authenticity of experience is the most outstanding quality of Dalit autobiography. It articulates the rage against education and social system that privileges the upper caste. However, it is incorrect to say that Dalit autobiography is a mere reportage of the pain and suffering of the untouchables. The ultimate goal of Dalit literature is to evoke the Dalit consciousness.

Artha - Journal of Social Sciences

Literature about Dalits and by Dalits is a huge body of writing today. Autobiographical accounts as well as testimonies by Dalit writers from all over India have already been looked at as genres that locate personal as well as the suffering of a mass of people within the larger discourse of human rights. The present paper attempts to examine literary narratives by Dalits and place them as evidence of atrocities committed against them. The paper will also look closely at Dalit stories as typifying the Dalit lived experience. The stories also throw light on the rich and varied culture of these subaltern castes. It is worth noting that there seems to be a hierarchy even among the various kinds of Dalits. The literature analysed will cover stories that show the range of experiences and the cultural identity of the Dalits. The Dalit literary narrative will be looked at as a document that records the suffering of the marginalised and, therefore, as something that is different from a socio...

NARENDRA K U M A R ARYA

Knowledge has intricate linkages with forces that govern our social life. Invariably, the production and denial of knowledge are akin to the production and denial of power. For centuries, caste system in the Indian subcontinent has controlled, regulated and hierarchised knowledge. Brahmanism, as it evolved over a period of time, has sought to legitimate the servitude of Dalit castes through its hegemony over the social universe of knowledge.Of course, the hegemony has seldom been complete or gone uncontested. Today dalits claim a stake, both in knowledge and the power that it serves more strongly than ever before. Right from the nineteenth century, dalit discourses have emerged as challenges to the Brahmanic-national-universal with distinct and dissenting imageries of future and the quotidian, the community and the nation. Violence and at times token concessions have been the usual response of the powers that be to such dissents. It was a ploy of the dominant and not really commitment to incorporate dalit thinkers, ideologues and fighters in Social Sciences.

New Man Publication, Mumbai

Kunj Bihari Ahirwar

Today, the untouchables have been termed as Dalits and the evil practice of untouchability has been abolished by the Indian Constitution. But, before its abolishment, it had forced the Dalit community to live a life worse than animals. The origin and causes of untouchability are still in controversial talks. The untouchability has its roots in Hindu Caste System, which is supposed to be more than 1500 years old; it is associated with the times when the Aryans invaded India. The advent of the fifth Varna laid foundation to the untouchability; the community that was categorized as untouchables is now know as Dalit Community. The questions like who were Dalits (Ati-shudras) and how really the evil practice of untouchability was begun are matter of investigation. In this paper, I have tried my best to investigate these questions. I have investigated about meaning of historiography, origin of untouchability and meaning and origin and signification of term Dalit.

Journal of English Language and Literature

KOTA Dr. Tushar Nair

In Indian society, the Dalits who are known earlier as untouchables or Shudras have been suffering in the name of Casteism. Even after more than 70 years of achieving Independence, the Dalits are bearing the brunt of torture and humiliation at the hand of upper caste people in many states in India. Dalits, being born in lower castes, are the worst target of embarrassment, dishonour, torture and discrimination. They have been inflicted violence physically or mentally in such a cruel manner that their whole identity is trampled underfoot. For centuries their life has been an epic of traumatic experiences. Their survival was possible at the behest of upper caste people who otherwise treated them like beasts. The wishes and dreams of the Dalits didn’t matter as they had no right to dream for a world of joy and progress. With the passage of time, people in the Dalit community realised the traumatic situation and sufferings of their brethren and decided to give voice through literature to...

The Journal of Commonwealth Literature

Judith Misrahi-Barak

Ayudh: International Peer-Reviewed Journal

Provakar Palaka

rightly said that knowledge is/has power. Certain ideas have dominated the Epistemological discourse. Certain ideas have become the normative while certain other kinds of ideas have been deliberately relegated to the margin. In Indian context, Brahmanism was created and shrewdly sustained for ages as the normative. However, such hegemonic and regressive ideas never went unchallenged. Dalit Panthers Movement in 1970s gave a decisive turn to the Dalit Movement in India by creating a counter discourse against Brahmanism in a very systematic manner. Dalit literature which emerged from Dalit movement, is not just about expression of anger against the discursive idea of caste and casteism, or pain and misery of the community, but also it strongly lies in creating Dalit philosophy and Dalit Epistemology.

SMART M O V E S J O U R N A L IJELLH

Abstract: Dalit literature in India over the past many decades has emerged as a separate and important category of literature in many Indian languages. It has provided a new voice and identity to the communities that have experienced discrimination, exploitation and marginalization due to hierarchical caste system. Dalit literature has also made a forceful case for human dignity and social equality. In the light of the growing importance of the study of Dalit literature, this paper attempts to explore the origin, concept and contributions of Dalit literature in India and brings out its significance and key features. Keywords:Challenged, Communities, Dalit literature, Dignity, Equality, Exploitation, History of Dalit Literature, Socio-political commitment, Untouchable

RELATED PAPERS

Vittorio Villa

Folia Linguistica Historica

Andrea Sansò , Linda Konnerth

Transcultural Psychiatry

Laurence J Kirmayer

Luisa Jiménez

Enea Pezzini

Nabila Azzakhro

Nabila Åżżähŕä

Tancredi Bella

Periklis Pavlidis

Alex Leonardi

C.P. Alejandra Luna Rosas

Analytical Sciences: X-ray Structure Analysis Online

Venkatraman Krishnakumar

Richard Kayondo Ssekibuule

Learning & Memory

Yomayra Guzman

2006 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work in Design

Mohamed Amine Ouertani

2019 International Conference on Numerical Simulation of Optoelectronic Devices (NUSOD)

Trevor Hall

JIATAX (Journal of Islamic Accounting and Tax)

Tumirin Tumirin

Journal of Women's History

Julie Guard

Thomas Ede Zimmermann

Cell Transplantation

Anatol Manaenko

Jurnal Civic Hukum

Irish Journal of Medical Science

Brendan O'Shea

Tatiane Iembo

Vanessa Buraco

Veterinary Microbiology

Lenka Havlíčková

Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry

Cláudia Zini

Accounting and Managerial Economics for an Environmental-Friendly Forestry, INRA. Économie et sociolotie rurales, Actes et Communications

Markku Penttinen

Journal of Nutrition Health & Aging

Fernando Lamarca

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

The Criterion: An International Journal in English

Bi-Monthly, Peer-reviewed and Indexed Open Access eJournal ISSN: 0976-8165

The Dalit Vision and Voice: A Study of Sharan Kumar Limbale’s Akkarmarshi

Assistant Professor of English Govt. College for Women Thiruvanathapuram.

Kerala, India.

Writing is a form of therapy: sometimes I wonder how all those who do not write, compose, or paint can manage to escape the madness, the melancholia, the panic fear which is inherent in the human situation. (Graham Greene 9)

Sharan Kumar Limbale is an illustrious Dalit writer in India who has authored extensively up to forty books including his autobiography Akkarmashi ( The Outcaste ) and is currently Professor and Regional Director of Yashavantrao Chavan Maharashtra Open University and his creative interest rests on the Dalit struggle and identity.

Dalit Literature is a new literary canon with an evident disregard for form, content and style, and a vibrant expression of the newly awakened sensibilities which distinguishes it from the mainstream literary traditions. It is a Literature of protest against all forms of exploitation based on class, race, caste or occupation. It rejects both the Western and Eastern theoretical conceptions like Freud’s Psychoanalysis, Barthe’s Structuralism and Derrida’s Deconstruction together with the Indian theories of Rasa and Dhawni. The very foundations of Indian Mythology are questioned and de-constructed by the Dalit writers. They consider the legendary figure Ekalavya as their forefather and Shambooka – another Dalit in Ramayana who was killed by Rama at the behest of Vasishta, is worshipped by the Dalits. These writers express their experiences in stark realistic manner by using their native speech. Their language as well as images comes from their experiences instead of their observation of life. Dr. C.B. Bharti claims:

The aim of Dalit Literature is to protest against the established system which is based on injustice and to expose the evil and hypocrisy of the higher castes. There is an urgent need to create a separate aesthetics for Dalit literature, an aesthetics based on the real experiences of life. ( The Aesthetics of Dalit Literature )

This unique branch of aesthetics is most expressive in autobiographies as the experiences they portray are peculiar only to the communities in which they are born into. Autobiographies are generally written by eminent personalities towards the end of their lives and who have got much to evidence before the world, while Dalit autobiographies are penned at an early age when the author is neither distinguished nor eminent but noted for its depiction of a poignant past that has affected the history of a community. These autobiographies deal not only with the caste system as oppressive but also depict how economic deprivation and poverty are handmaids with caste discrimination.

Sharan Kumar Limbale’s Akkarmashi penned at an age of twenty five depicts the meta-realistic accounts of his life as a Dalit in particular and which can be extended to the life of any individual of Mahar community in general. In the text, the narrator moves back

and forth between the individual ‘I’ and the collective ‘We’. The experiences of exclusions and ostracizations of both the self and the community are the creative and critical sources used to “create testimonies of caste-based oppression, anti-caste struggles and resistance” (Rege 14) offering a distinct world view. Limbale in an interview notes:

The span of my autobiography is my childhood. . . I want write about my pain and pangs. I want write about the suffering of my community. So I cannot give importance to my personal life. I am writing for social cause. .

. . My autobiography is a statement of my war against injustice. (The Criterion)

This paper centres on the depictions of the “self”; the split identification; untouchability; poverty; education and language as evidenced in Akkarmashi and would argue that Limbale’s suffering is intensified on the account of he being an akkarmashi or illegitimate. To be a Dalit in a caste-ridden society is a curse and to be an illegitimate within the Dalit community is to be doubly cursed. Dalits are “outcasts” to the society but a “half-cast” of an “outcast” is much less than being a human. It is the record of “the woes of the son of a whore” (ix).

The paper also makes an attempt to understand the vision and voice of the Dalits as the texts speak for the “outcasts” and are therefore rendered from voiceless and passive objects of history to self-conscious subjects who procreate alternative modes of knowledge and knowing. Limbale projects before the readers an objective and disinterested account of his life from birth to adulthood, carefully creating the image of his community in conflict with the contemporary social and cultural conditions. The narrator’s self reflects his life in particular and the life of the community in general. Toni Morrison observes:

Autobiographical form is classic in Black American or Afro-American Literature because it provided an instance in which a writer could be representative, could say, ‘my single solitary and individual life is like the lives of the tribe; it differs in these specific ways, but it is a balanced life because it is both solitary and representative’. (327)

A Dalit has no personal life of his own but is dissolved in the engulfing whirlpool of his community. Akkarmashi works as the mouthpiece of the community, it depicts their togetherness in triumphs and tribulations as “the self belongs to the people and people find a voice in the self” (Butterfield 3).

As a Dalit Intellectual, the narrator experiences split identification at various levels

– as an illegitimate; as a Mahar and even as an educated Dalit who has advanced in social order than his community but at the same time forbidden to step up the established social order by the caste Hindus. Limbale talks about his birth:

My first breath must have threatened the morality of the world. With my first cry, milk must have splashed from the breasts of every Kunti.

Why did my mother say yes to the rape which brought me into the world? Why did she put up with the fruit of this illegitimate intercourse for nine months and nine days and allow me to grow in the foetus? Why did she allow this bitter embryo to grow? How many eyes must have humiliated her because they considered her a whore? Did anyone distribute sweets to celebrate my birth? Did anyone admire me affectionately? Did anyone

celebrate my naming ceremony? Which family would claim me as its descendants? Whose son am I, really? (36-7)

In another account, Limbale relates how he owns his name to a sympathetic teacher:

The teacher decided to enroll my name in the register after I attended school regularly for four to five days. When he was convinced that I was serious about my schooling he asked me my father’s name. I did not know my father’s name. Strange that I too could have a father!

. . . . The teacher Bhosale by name would sarcastically call me the Patil of Baslegaon. I felt good as well as bad to be called Patil. The name of Hanmanta Limbale, the Patil of Baslegaon, was added to my name in the school record. When Hanmanta came to know this he arrived with four or five rowdies. . . . But Bhosale, the headmaster, was an upright man. . . Hanmanta tried all his tricks desperately. He even pleaded. Finally he had to go away unsuccessful. I owe my father’s name to Bhosale, the headmaster. (45)

Born of a high caste father – a Patil and an untouchable mother – a Mahar, Limbale became an “akkarmashi”, as his parentage was unacknowledged through the legitimacy of marriage. This curse of being “fatherless” followed Limbale all throughout his life. It became the most heinous of obstructions, a hopeless situation – being tortured for being an akkarmashi within his family and extended to the most decisive moments in his life as seeking an admission in school or college and the prospect of getting married. More than the general shocking life of Dalits, where one suffers in groups, what affects Limbale is his isolated stigma of being an akkarmashi. Limbale is reminded now and then by the society – his position within the position less group of outcasts. He laments, “. . . a man is recognized in this world by his religion, caste, or his father. I had neither a father’s name, nor any religion, nor a caste. I had no inherited identity at all.” (59). Is not this lack of inherited identity, his real identity? The stigma of “akkarmashi” hurls around it intolerable humiliations.

The narrator-protagonist is someone more inferior to a Dalit. It is surprising to note that he is an untouchable among the untouchables. His identity is that of an “Akkarmashi” and this is what the narrator tries to present through the many episodes of his life. “Akkarmashi” in Marathi means eleven it needs another one to complete itself, to become twelve, a dozen which signifies completeness. With a government job and education to cushion him, Limbale still finds it difficult to get a wife. Limbale never enjoyed the prospect of selecting a wife of his choice. A single attempt at bride-viewing ends in disaster. At one point the reader suspects Limbale to be satisfied with any woman for a wife. He does not make a choice. He gets a wife out of sympathy and his occasional bribing his would-be father-in-law with alcohol. He notes, “The girl I married needed to be a hybrid like me to ensure a proper match. A bastard must always be matched with another bastard. No one else will marry their daughters to a bastard like me” (98). The text becomes the eye witness account of the horrors of the lives of a particular subaltern community.

However, Limbale does not succumb to the pitiable existence but acquires liberation and freedom from his purgatory of caste through education. The knowledge he had acquired from books, had taught him to think differently. He understood that the sufferings of their lives were based on the false concept of superiority. He has imbibed a

“Dalit Consciousness”, a consciousness of their own slavery (TADL 71), an understanding of their experiences of exclusion, subjugation, dispossession and oppression down the ages. It is this knowledge that liberates him. Limbale notes in his critical work, Towards an Aesthetic of Dalit Literature , “The conditions that I have written about, the environment that I have written about, no longer exist in my house, because of the position that I happened to hold today” (156). He further explains:

Now, after twenty-five years, my past has been so destroyed that I have been cut off from it, I’ve been completely separated from it. Neither have I gone home, nor does my mother see me as I was before. ‘Some big officer has come, some VIP guest has come’: thus will she offer me water. I no longer have the same attachment to my colony, my relatives, my language. Everything has changed. And because of that change, I am done writing about the history that I had to write about. (155)

The past does not lure him with its wonders of nostalgia as there is nothing to be nostalgic about. Limbale’s social protests and the subsequent redemption serve as inspiration for other members in the community to use education to overcome their economic and social conditions.

Dalit Literature abounds in genuine descriptions of untouchability and poverty in an uncouth day-to-day spoken language. The insurmountable challenge faced by Limbale and other Dalits as young children is hunger. The writer has dwelt on this basic need of man over and again all throughout the book, philosophizing on the evident need of food:

God endowed man with a stomach. . . . Since then man has been striving to satisfy his stomach. Filling even one stomach proved difficult for him. He began to live with a half-filled one. He survived by swallowing his own saliva. He went for days without eating anything. He started selling himself for his stomach. A woman becomes a whore and a man a thief. The stomach makes you clean shit; it even makes you eat shit. ( Akkarmashi 8)

The Caste Hindus in Indian society used to exploit the Dalits by making them do the most menial jobs the whole day just for a piece of bread. The text is replete with incidents of hunger which is projected before a class of readers who are blissfully unaware of such undercurrents. The Dalits are treated worse than animals. Their presence is usually banned from upper-class localities. They were made to hang pots from their necks to avoid polluting the streets by their spittle and had to carry brooms tied to themselves to wipe away their footprints from the “upper caste” streets. In P.I. Sonkamble’s Athavaninche Pakshi , the narrator Pralhad, an orphaned boy relates an incident of throwing away a dead dog:

Somehow I controlled my mind and held the tail of the dead dog. As it was completely decomposed, that part of the tail gave way and came into my hand. Though it had a stinking smell, I continued with the job as I had a craving for a small piece of bread which I hoped to get after finishing it. (87)

Daya Pawar in Baluta evokes a similar feeling, the narrator reflects:

What a coward I am? Who made me such a coward? My life was similar to that of any crawling object in the street which even cannot hiss at the children who poke at it with a stick. Sometimes I used to feel that I have lost all my self-respect just for a morsel of food. (72)

The Dalits ousted to the village outskirts lead an inhuman life. Eternally deprived with no money, no land, no work and no education these people falter in darkness with no realisation of human worth. What is evident from the text is that, they never think; rather accept this suffering as their lot. They depend on the Savarnas in the village for work and food. They do not think beyond these basic needs. Men are drunkards and women are exploited by the villagers. From this perspective it is a collective past, Limbale is each and every Dalit deemed untouchable.

Dalits are being exploited physically, mentally and socially in the caste ridden society. Though India is politically free with her own Constitution proclaiming liberty, equality and fraternity spearheaded by a Dalit himself, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar, it is still difficult for backward classes to lead their lives peacefully. Dalit Intellectuals operate their modes of resistance creatively in Dalit literature, the most powerful being Dalit autobiographies. Dalit Literature is an arduous endeavour from the canonical to the marginal, from mega-narratives to micro-narratives, from the virtual to the real, and from self- emulation to self-affirmation.

Works Cited:

Bharti, C.B., “The Aesthetics of Dalit literature,” Trans. Darshana Trivedi. Hyati, June 1999.

Butterfield, Stephen. Black Autobiography in America . Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1974.

Greene, Graham. Ways of Life: An Autobiography . London: Vintage Books, 1999. Limbale, SharanKumar. The Outcaste: Akkarmashi . Trans. Santosh Bhoomkar.

New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2005.

– – – . Towards an Aesthetic of Dalit Literature: History, Controversies and Considerations. Trans. Alok Mukherjee. New Delhi: Orient Longman, 2007.

Morrison, Tony. “Rootedness: The Ancestor as Foundation”, Literature in Modern World . Ed. Dennis Walder. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Pawar, daya. Baluta . Mumbai: Granthali Prakashan, 1982.

Rege, Sharmila. Writing Caste/ Writing Gender: Reading Dalit Women’s Testimonies. New Delhi: Zubaan, 2006.

Sonkamble, P.I. Athavaninche Pakshi . Aurangabad: Chetana Prakashan, 1993. http://www.the Criterion.com

WhatsApp us

A Critical Discourse on Aesthetics in Contemporary Indian Dalit Literature

Limbad girishkumar nagjibhai.

Ph.D Research Scholar, Hemchandracharya North Gujarat University ([email protected])