An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

THE CRITICAL ROLE OF SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGY IN THE SCHOOL MENTAL HEALTH MOVEMENT

Joni williams splett.

University of South Carolina

JOHNATHAN FOWLER

Mark d. weist, heather mcdaniel, melissa dvorsky.

Virginia Commonwealth University

School mental health (SMH) programs are gaining momentum and, when done well, are associated with improved academic and social–emotional outcomes. Professionals from several education and mental health disciplines have sound training and experiences needed to play a critical role in delivering quality SMH services. School psychologists, specifically, are in a key position to advance SMH programs and services. Studies have documented that school psychologists desire more prominent roles in the growth and improvement of SMH, and current practice models from national organizations encourage such enhanced involvement. This article identifies the roles of school psychologists across a three-tiered continuum of SMH practice and offers an analysis of current training and professional development opportunities aimed at such role enhancement. We provide a justification for the role of school psychologists in SMH, describe a framework for school psychologists in the SMH delivery system, discuss barriers to and enablers of this role for school psychologists, and conclude with recommendations for training and policy.

Although mental health challenges experienced early in childhood tend to be stable and predictive of negative outcomes later in youth, early prevention and intervention has the potential to alter this negative trajectory ( Hill, Lochman, Coie, Greenberg, & Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group [CPPRG], 2004 ; Lochman & CPPRG, 1995 ). Unfortunately, only a small percentage of students experiencing mental health problems are identified and receive treatment by “frontline gate-keepers,” such as educators, school psychologists, mental health clinicians, or pediatricians ( Briggs-Gowan, Horwitz, Schwab-Stone, Leventhal, & Leaf, 2000 ). In fact, only approximately half of children in need of mental health services actually receive help ( Merikangas et al., 2010 ). In response to this need, school mental health (SMH) programs have progressively expanded over the past several decades ( Foster, Rollefson, Doksum, Noonan, & Robinson, 2005 ; Weist & Murray, 2007 ). The expansion of SMH programs relates to a range of positive outcomes, such as enhanced access to early intervention, improved academic performance, decreased stigma, and reduced emotional and behavioral disorders (e.g., see Hoagwood, Kratochwill, Kerker, & Olin, 2005 ; Hussey & Guo, 2003 ).

As SMH programs are increasingly prominent in efforts to bridge the gap between unmet youth mental health needs and effective services, SMH workforce development will be a key factor in promoting success for students ( Hoge et al., 2005 ). Several professionals, such as school counselors, school psychologists, school social workers, school nurses, and special education teachers, play a critical role in delivering SMH services ( Mellin, Anderson-Butcher, & Bronstein, 2011 ). Generally, each of these professionals has the sound training and experiences needed to deliver quality SMH services and work collaboratively across disciplines ( Ball, Anderson-Butcher, Mellin, & Green, 2010 ). Working collaboratively is important because it is clear that not one discipline can individually address the multifaceted mental health barriers to student learning. Although the remainder of this article focuses on the role of school psychologists in SMH, it is important to remember that more effectively meeting the mental health needs of all youth will require the competency and collaboration of all mental health and education professionals ( Flaherty et al., 1998 ).

School psychologists are in a key position to advance SMH and desire this involvement ( Curtis, Hunley, Walker, & Baker, 1999 ; Fagan & Wise, 2007 ), but research suggests that school psychologists have not been able to assume this role to the degree promoted or desired ( Curtis, Grier, & Hunley, 2003 ; Friedrich, 2010 ). The purpose of this article is to identify the roles of school psychologists across a continuum of SMH practice and to offer an analysis of current training and professional development opportunities. In the following section, we provide justification for school psychologists’ enhanced role in SMH, within a public health framework for prevention and intervention. We then discuss barriers to and enablers of this role for school psychologists and conclude with actionable recommendations for training and practice.

SMH and S chool P sychology

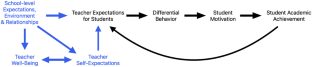

Similar to other SMH professionals, school psychologists possess a unique blend of knowledge regarding multiple factors influencing SMH programs and services, including developmental risk factors, the impact of behavior and mental health on learning and life skill development, instructional design, organization and operation of schools, and evidence-based strategies for promoting mental health and wellness (see National Association of School Psychologists [NASP], 2010a ). Additionally, literature and policy documents from the NASP (2010a , 2010b , 2010c ) encourage and delineate a role for school psychologists in SMH (e.g., see Sheridan & Gutkin, 2000 ). For example, Figure 1 illustrates the NASP Model for Comprehensive and Integrated School Psychological Services, which delineates services that might typically be provided by school psychologists, including “interventions and mental health services to develop social and life skills” ( NASP, 2010a , p. 2; Ysseldyke et al., 2006 ). Along with the NASP standards for graduate training and credentialing, these policy documents indicate not only that practicing school psychologists are expected to provide mental health services to children, families, and schools, but also that quality training that meets professional standards should be provided to them at pre- and in-service levels ( NASP, 2010b , 2010c ).

National Association of School Psychologists’ Model for Comprehensive and Integrated School Psychological Services. (Reprinted from Model for Comprehensive and Integrated School Psychological Services, NASP Practice Model Overview [Brochure], by National Association of School Psychologists, 2010 , Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists. Retrieved from http://www.nasponline.org/standards/practice-model/Practice_Model_Brochure.pdf . Reprinted with permission.)

Unfortunately, however, this historically has not been the case; despite a desire to offer expanded services, school psychologists have traditionally been limited to heavy psychological assessment caseloads consuming more than 50% of their work ( Hosp & Reschly, 2002 ; Reschly, 2000 ). But some evidence suggests that school psychologists may be expanding their role and providing more mental health services. In a recent survey of school psychologists, Friedrich (2010) reported that approximately 50% of their work week involved mental health services, such as consultation with school staff and problem-solving teams, social–emotional–behavioral assessment, and various forms of counseling. To further promote this trend, we delineate an expanded role school psychologists could have in providing a continuum of SMH prevention and intervention in the following section. By identifying the role of school psychologists in this manner, we hope to raise awareness of what mental health services school psychologists could be providing within the field of school psychology and among administrators, teachers, other mental health providers, families, and graduate trainers.

SMH Services Provided by School Psychologists

The fields of school psychology and education, in general, are increasingly adopting tiered models of learning; behavioral and mental health services and supports, including School-Wide Positive Behavior Supports (SWPBS; Horner, Sugai, & Anderson, 2010 ); Response to Intervention (RTI; National Center on Response to Intervention, 2010 ); and the Interconnected Systems Framework, which bridges SMH practices and SWPBS ( Barrett, Eber, & Weist, 2009 ). These models are based on a public health approach and promote a continuum of support, including school-wide prevention, early intervention, and more intense treatment ( Gordon, 1983 ). Given the overwhelming predominance of tiered models in the field, we have conceptualized the role of school psychologists in providing mental health services within and across this framework.

The public health, tiered model includes prevention and intervention services across three tiers that are commonly called universal, selective, and indicated ( Gordon, 1983 ; O’Connell, Boat & Warner, 2009 ). As this model has been applied widely in educational settings, the terminology has been modified, resulting in multiple names for each tier across fields. For example, SWPBS and RTI refer to the three tiers as primary, secondary, and tertiary, or Tier 1, Tier 2, and Tier 3 ( Horner et al., 2010 ; National Center on Response to Intervention, 2010 ). Although the conceptual difference among terminologies is minimal, the inconsistencies across fields have created unnecessary confusion and should be resolved.

In the public health model, all students have access to universal services and practices, and the majority of students (e.g., 80%) will only need this level of support. However, some students demonstrating emerging difficulties will need selective supports and interventions (e.g., about 15%), whereas an even smaller percentage of students will need indicated treatments (e.g., about 5%; Horner et al., 2010 ; O’Connell et al., 2009 ). Commonly, services across these three tiers are provided through a variety of school teams, composed of administrators, teachers, SMH professionals, students, and/or families ( Markle, Splett, Maras, & Weston, in press ). For example, schools implementing SWPBS and/or RTI may have a school leadership team in charge of universal prevention efforts ( Yergat, 2011 ); intervention, student support, and/or teacher assistance teams at the selective level ( Hawken, Adolphson, Macleod, & Schumann, 2009 ); and multidisciplinary special education teams, wraparound teams, and/or interagency teams at the indicated level ( Eber, Sugai, Smith & Scott, 2002 ; Freeman et al., 2006 ; Turnbull et al., 2002 ). The mental health services that school psychologists, as well as other SMH professionals and school teams, could provide are delineated in Figure 2 .

The mental health services that school psychologists and other school mental health professionals could provide within and across tiers.

School Psychologists and Three-Tiered, Mental Health Services.

As illustrated in the bottom box of Figure 2 , school psychologists, in collaboration with other school and mental health professionals are involved in planning, implementing, and evaluating school-wide prevention efforts at the universal level. They are critical members of their school’s Tier 1 team, as they possess unique knowledge of best practice efforts to prevent mental health concerns, program planning and evaluation, and databased decision making ( NASP, 2010a ; Splett & Maras, 2011 ). At the selective level, as indicated in the middle box of Figure 2 , school psychologists have the knowledge and experience to be integrally involved in the screening process, intervention development and delivery, teacher and team consultation to support intervention implementation, and progress monitoring ( Gresham, 2008 ; Hawken et al., 2009 ; Weist, Rubin, Moore, Adelsheim, & Wrobel, 2007 ). Finally, at the indicated level (top box of Figure 2 ), school psychologists’ knowledge and skills in assessment, intervention, consultation, and collaboration position them to be highly qualified and needed in roles delivering interventions, as well as consulting, collaborating, and communicating with families and other school and community professionals ( Hoagwood & Johnson, 2003 ; Weist, 2003 ). In the following section, factors that may facilitate or hinder the ability of school psychologists to take on an expanded role, such as the one described in Figure 2 , are addressed.

B arriers to and E nablers of B est P ractices

Although discussion of ideal roles and responsibilities of school psychologists in the provision of SMH services is an important exercise, equally crucial is the exploration of factors that may serve as barriers to or enablers of such responsibilities. Several studies have surveyed school psychologists regarding their actual and desired duties, as well as their perceptions of what assists or hinders their active involvement in SMH ( Bramlett, Murphy, Johnson, Wallingsford, & Hall, 2002 ; Friedrich, 2010 ; Hosp & Reschly, 2002 ; Noltemeyer & McLaughlin, 2011 ; Suldo, Friedrich, & Michalowski. 2010 ). Some of the facilitating and obstructing factors cited across these sources include time constraints, administrative support, pre-service training and supervision, professional development, cultural awareness, and the frequency and type of referrals made for services.

Time and Personal Prioritization

The type and quality of services that school psychologists are able to provide are affected by the practitioner’s available time, which is affected by many time-consuming responsibilities and often itinerant assignments to multiple school buildings. Several studies have shown that school psychologists spend the majority of their time involved in assessment activities, especially as they relate to special education eligibility determinations ( Stoiber & Vanderwood, 2008 ). However, it is not identified as the most valuable activity or the area where professional development was desired ( Stoiber & Vanderwood, 2008 ). Although assessment and special education procedures are necessary roles, their continued dominance has prevented school psychologists from taking on a broader continuum of SMH services ( Harrison et al., 2004 ; Meyers & Swerdlik, 2003 ). Unfortunately, a dissonance between ideal time allocation and actual duties of school psychologists is often significant ( Hosp & Reschly, 2002 ). In addition, school psychologists are often assigned to multiple schools, meaning there are days when they are unavailable to students and staff at a particular school and unable to meet the mental health needs that arise. Itinerant placements also decrease school psychologists’ access to staff and students, making it difficult to become integrated in the school and bring visibility to the breadth of SMH services they can offer ( Meyers & Swerdlik, 2003 ; Suldo et al., 2010 ).

Conversely, school psychologists with lower student-to-school psychologist ratios and manageable assessment and intervention caseloads report providing more SMH services and seeking more professional development related to social–emotional interventions ( Harrison et al., 2004 ; Meyers & Swerdlik, 2003 ). Further, the school psychologist’s personal desire to provide SMH interventions actually helps to increase involvement in them ( Suldo et al., 2010 ). Despite the desire and time to provide quality SMH services, school psychologists often still encounter barriers related to inadequate and insufficient training, supervision, and professional development in SMH roles and activities.

Training Limitations

School psychologists’ training and competence in SMH services is another area that can inhibit, as well as facilitate, the provision of SMH services. For example, Stoiber and Vanderwood (2008) found that surveyed school psychologists reported feeling less competent in providing prevention/intervention activities than assessment and consultation/collaboration activities. Similarly, in a statewide survey asking school psychologists about their awareness and understanding of the most recent guidelines for school psychology training and practice from Blueprint III (see Figure 1 ), Noltemeyer and McLaughlin (2011) found that only 25% of respondents reported expertise in the practice domain, “enhancing the development of wellness, social skills, and life skills.” School psychologists may feel they are not experts in providing SMH services due to a perceived lack of content knowledge and applied experiences ( Suldo et al., 2010 ). Interviewees in Suldo and colleagues’ study (2010) described feeling they had too little exposure to important SMH topics, such as treatment planning and group counseling during pre- and in-service training, likely leading to a lack of confidence in their ability to competently provide these services. Further complicating the problem is the fact that the population of students and families increasingly in need of SMH services are from diverse, multicultural backgrounds for which school psychologists also have insufficient training and supervision ( Newell et al., 2010 ). This is also true for other mental health staff working in schools ( Clauss-Ehlers, Serpell, & Weist, in press ). These factors present a situation in which SMH providers, including school psychologists, feel underprepared and overwhelmed to broaden their role in SMH programs.

Conversely, school psychologists interviewed by Suldo and colleagues (2010) frequently indicated that sufficient training and/or confidence in one’s ability were facilitators of comprehensive SMH services. Specifically, interviewees noted the importance of training experiences that fostered skill development in sufficiently preparing them to engage in a range of SMH activities.

Collaboration With and Engagement of School Personnel

At the school-building level, the relationship and interactions between school psychologists and other school staff impacts the staff’s perception of the school psychologist and the breadth of services school psychologists offer. For example, inordinate time allocated to one area of practice (i.e., assessment; Stoiber & Vanderwood, 2008 ) likely prohibits school psychologists from expanding the services they offer. In schools where school psychologists spend nearly all of their time engaged in special education eligibility determination, other school staff may not realize the breadth of skills school psychologists may possess across the prevention and intervention continuum and therefore may not go to them for help or with concerns ( Harrison et al., 2004 ). As a result, the perception of administrators, other school staff, families, and the community regarding the role and function of school psychologists is likely limited to diagnostic responsibilities in many settings ( Harrison et al., 2004 ; Meyers & Swerdlik, 2003 ).

Schools’ often narrowly-defined emphasis on academics and achievement outcomes also likely limits school psychologists’ ability to expand the SMH services they offer ( Hoagwood et al., 2005 ; Severson, Walker, Hope-Doolittle, Kratochwill, & Gresham, 2007 ). Research over the past two decades has documented that most schools perceive their primary mission to be academics, with the legitimacy of any focus on social–emotional development frequently questioned ( Del’Homme, Kasari, Forness, and Bagley, 1996 ; Lloyd, Kauffman, Landrum, & Roe, 1991 ). More recently, school psychologists interviewed by Suldo and colleagues (2010) reported that many staff in their schools are exclusively focused on academics and lack concern for students’ mental health.

Generating appropriate referrals for services can also be challenging for SMH providers. For example, there is evidence that youth presenting “internalizing” disorders such as depression, anxiety and trauma, interpersonal issues, and developmental problems may be referred for services less often, whereas students showing acting-out behaviors, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, or clear academic problems are more likely to be referred ( Friedrich, 2010 ). A number of reasons may account for these findings, including inadequate knowledge and training in identifying students’ mental health concerns among most school staff ( Severson et al., 2007 ). The issue of over- and under-referred students limits mental health providers’ ability to provide an appropriate, full continuum of SMH services.

In contrast, school psychologists who are supported in delivering SMH services by their building-level administrators and teachers are more likely to engage in a breadth of activities ( Suldo et al., 2010 ). For example, Suldo and colleagues (2010) found that teachers’ support of SMH services and expectation of the school psychologist’s role to include SMH responsibilities were enablers of school psychologists’ ability to engage in related activities.

District and Systems Issues

At the district level, the conceptualization of the school psychologist’s role, provision of sufficient resources, and in-house professional development impact the breadth of SMH services school psychologists provide. For example, a prominent theme in focus groups conducted by Suldo and colleagues (2010) was that school psychologists’ district-level department and administration’s definition of their roles and responsibilities either excluded SMH services or was too ambiguous to facilitate a defined role. In contrast, districts that prioritized SMH services by providing explicit permission to school psychologists to engage in related activities through guidelines for SMH services, job descriptions inclusive of SMH services, district mental health initiatives, and the allocation of sufficient financial and personnel resources, in fact, increased school psychologists’ involvement in them ( Suldo et al., 2010 ). Providing internal professional development opportunities related to SMH services also demonstrates support for such activities and ensures a competent workforce ( Suldo et al., 2010 ).

R ecommendations to E nhance I nvolvement and L eadership in SMH

It is clear that school psychologists are in a unique position to influence and shape the evolving SMH agenda. Although effective SMH includes many professional disciplines (see Flaherty et al., 1998 ), school psychologists bring a particular blend of skills and training that are ideal for leadership roles in this agenda. These skills include, but are not limited to, an understanding of child development, psycho-educational assessment, special education law, consultation methodology, program evaluation, and interventions at both the individual and systemic level. In the final section of this article, several actionable recommendations related to pre-service training, school–university–community partnerships, professional development, and public relations are provided to enhance school psychology’s involvement and leadership in SMH.

Recommendation 1: Recruit Students With Interest in SMH Services and Foster Current Students’ Motivation

Training programs should enhance recruitment of students with interest in the full continuum of SMH services while striving to build interest among current students. Program applicants and existing providers alike may be evaluated for such attributes using scales of readiness such as the Evidence Based Practice Attitude Scale ( Aarons, 2004 ), observational ratings through role-played treatment or collaboration scenarios, and in-depth interviewing about ideal roles and responsibilities of school psychologists within an expanded SMH framework ( Weist, 2003 ).

Recommendation 2: Intentional Integration of SMH Activities Into Field Experiences

Training programs must ensure that graduates have sufficient content knowledge and applied experiences to build their interest and confidence in delivering SMH services ( Perfect & Morris, 2011 ). This likely requires significant changes to the courses and experiences school psychology graduate training programs require and provide ( Perfect & Morris, 2011 ). To promote competencies using methods beyond didactic courses, school psychology programs should provide field experiences or practicum courses that specifically include experience in all three tiers of services, including climate enhancement, enhancing team effectiveness, implementing preventive skill training groups, and providing evidence-based individual, group, and family therapy to students while under the supervision of a competent professional ( Perfect & Morris, 2011 ). For this training to occur, more active involvement by school psychology training programs in identifying and recruiting practicum sites to ensure these opportunities will be required. It is likely that it will be difficult for programs to find competent supervisors (e.g., licensed, doctoral-level psychologists) engaged in SMH services, but program administrators should consider including other professionals engaged in SMH services as field supervisors and should seek to increase collaboration between university and field supervisors ( Ross, Powell, & Elias, 2002 ).

Through increased collaboration, training programs can help facilitate improved understanding of the specific experiences their students need and design strategies for providing such experiences. At the University of South Carolina, the first and third author have collaborated with field supervisors of school and clinical–community psychology students to explicitly require and provide a continuum of SMH service opportunities. This initiative has recently been supported by the integration of a grant-funded research project into the practicum course. The research project, Student Emotional and Educational Development (SEED), is testing the feasibility and preliminary impact of an intervention package for middle and high school students with or at risk for developing mood disorders. The intervention is being delivered by advanced school and clinical–community psychology graduate students enrolled in the first author’s practicum course in collaboration with social work graduate students and child psychiatry medical residents. The inclusion of this research project as part of the students’ practicum experiences is providing them with needed interdisciplinary experience and training in specific evidence-based practices for the treatment of mood disorders, while benefiting the schools and the study through the services delivered by the trainees.

In addition, graduate training programs should ensure that students are aware of factors that may inhibit and/or facilitate their provision of SMH services to better prepare them for real-world practice. Students should be asked to discuss their observations of these factors in the field experiences, and trainers should help students generate solutions to current and future problems they may encounter following graduate school ( Suldo et al., 2010 ).

Recommendation 3: Ensure That Content Courses Provide Sufficient Knowledge Needed to Provide Continuum of SMH Services

School psychology training programs are required to ensure that graduates are exposed to all domains of practice following completion of coursework and to be competent across domains following internship ( Ysseldyke et al., 2006 ). Thus, training programs should compare their course requirements and objectives with the school psychology practice domains, paying particular attention to the mental health and social–emotional domain. Programs would benefit by improving or adding courses related to individual, small-group, and family interventions; crisis prevention and intervention; family-oriented prevention and intervention activities; psychopharmacology; and systems or organizational consultation ( Perfect & Morris, 2011 ; Ross et al., 2002 , Suldo et al., 2010 ).

Training programs should consider offering courses co-taught by a multidisciplinary team of faculty with students from a variety of specialties to provide collaborative experiences and increase prioritization of SMH services across education and mental health fields ( Ross et al, 2002 ; Weist et al., 2005 ). As described previously, a practicum course taught by the first author integrates the SEED research project, which facilitates collaborative relationships with trainees from other disciplines (i.e., social work and child psychiatry). As part of this training opportunity, all trainees participate in monthly meetings designed to help them learn more about one another’s background and training experiences and then begin to work together in a collaborative, strength-focused manner.

Unfortunately, graduate training programs in school psychology already face a tight timeline when tasked with addressing the breadth of practice domains required by accreditation organizations, making the call for additional coursework a difficult plan to implement. This is especially the case for specialist degrees, such as the Education Specialist (Ed.S.), where trainees are afforded less training time than those in doctoral programs. Training programs should evaluate these issues individually, but the need for refined training may certainly indicate the need for further specialization in the training of tomorrow’s school psychologists.

Recommendation 4: Encourage Areas of Specialization Related to SMH Prevention and Intervention Services

Just as one training program cannot realistically provide an adequate depth of training in all practice domains of school psychology, it is also important to acknowledge that one school psychologist simply cannot provide all the school psychology and SMH services indicated by a school’s needs or described in this article. It is also true that there are areas in addition to SMH in which school psychologists should be competently practicing, including assessment, pediatric school psychology, and neuropsychology ( Reynolds, 2011 ). For a more in-depth review of the range of services and practices promoted by professionals, see the NASP Model for Comprehensive and Integrated School Psychological Services illustrated in Figure 1 ( NASP, 2010a ). Given the sheer breadth of knowledge needed by school psychologists facing increasing demands for evidence-based services, professional organizations and governmental accrediting agencies should explore methods of providing specialization in targeted areas of practice, such as SMH prevention and intervention ( Reynolds, 2011 ). The recommendation for areas of specialization is not new to the field of school psychology. Specialization in the area of school neuropsychology was first introduced in 1981 by Hynd and Obrzut and has long been recognized as common practice in academia ( Reynolds, 2011 ). Advanced training in the area of SMH for school psychologists seeking professionally recognized specialization would likely improve the SMH workforce’s overall competency and interest in providing expanded services. Likewise, hiring school psychologists with specialized knowledge in the area of SMH is likely to address the time and personnel constraints currently facing the field by more clearly assigning SMH responsibilities, including interventions and mental health services to build the social–emotional and life skills of youth, to highly qualified and devoted staff with minimal assessment caseloads.

Recommendation 5: School–University–Community Agencies Should Partner to Provide Training and Expand Services

A key theme in moving the SMH agenda forward is the advancement of school and university– community partnerships. Such partnerships have several important benefits to the school district, university, and/or community agency, including school and/or community-based learning for undergraduate and graduate students, sustained and enhanced organizational capacity, and staff and organizational development ( Ross et al., 2002 ; Sandy & Holland, 2006 ). Community and school partners who participated in focus groups conducted by Sandy and Holland (2006) described the inclusion of college students in their settings as supporting initiatives that would have otherwise remained on the back burner and additionally providing staff with greater access to new information and research in the field. Further, when SMH practitioners become supervisors or college educators through university–school partnerships, higher quality pre-service field experiences are provided and exposure to the fields of school psychology and SMH is increased ( Community-Campus Partnership for Health, 2006 ; Perfect & Morris, 2011 ; Sandy & Holland, 2006 ).

Recommendation 6: Professional Organizations Should Emphasize Mental Health Prevention and Intervention Practices in Conferences and Training Programs

School psychologists have identified in-service professional development needs for effective SMH practice ( Suldo et al., 2010 ). For example, Stoiber and Vanderwood (2008) surveyed practicing school psychologists and found their top priorities for professional development were classroom-based behavioral intervention, followed by therapeutic interventions, functional assessment and prevention, key realms of SMH practice. Continued professional development can be pursued in a variety of manners such as graduate courses at local universities and continuing education courses offered at the annual meetings of professional organizations such as NASP, the American Psychological Association, the American School Health Association, and the University of Maryland Center for School Mental Health’s annual conference on advancing SMH (see http://csmh.umaryland.edu ).

In addition to enhanced offerings related to SMH by these and other professional organizations, it is also necessary for the field to evaluate the effectiveness of current professional development practices and identify strategies for improvement. Traditional professional development practices have been widely criticized for not leading to changes in practice ( Joyce & Showers, 2002 ). Thus, there is a need to enhance in-service training, to embrace principles of adult learning, experiential learning activities, mutual peer support, implementation support and coaching, and a view of intensive life-long learning ( Fixsen, Naoom, Blase, Friedman, & Wallace, 2005 ; Perfect & Morris, 2011 ; Weist, Stephan, et al., 2007 ).

Recommendation 7: School Districts Should Provide SMH Professional Development Opportunities

In-service trainings at the district level underscore the district’s commitment to student mental health and reducing barriers to their learning, as well as sustaining effective SMH systems of service ( Perfect & Morris, 2011 ). School districts should prioritize SMH competencies in their professional development opportunities and strive to provide effective professional development beyond traditional in-service meetings, such as group book studies, regularly scheduled supervision, coaching, collaboration, and re-occurring, in-depth, and experiential learning opportunities (e.g., a series of training sessions with opportunities for practice and feedback between meetings; Fixsen et al., 2005 ; Splett, 2012 ).

Recommendation 8: Initiate Public Relations Campaign Targeting School Staff, Families, and the Community Regarding SMH Services

In order to be seen as a mental health provider, visibility among and education of key stakeholders (e.g., school board members, school administrators, teachers, families, and community members) is essential ( Harrison et al., 2004 ). School psychologists and other SMH providers should consider proactively providing in-services and/or educational materials to their colleagues, clients, and constituents. To make educators, administrators, decision-makers, families, and community members aware of the range of SMH services school psychologists can provide, these efforts should address the school psychologist’s competency in and desire to provide a continuum of SMH services, the importance of these services and their link to academic outcomes, risk factors to identify students at risk for developing mental health concerns, and evidence-based prevention and intervention strategies ( Harrison et al., 2004 ; Ross et al., 2002 ).

C onclusion

The interdisciplinary SMH field is showing progressive growth related to documented and increasingly recognized advantages in bringing mental health to youth “where they are.” School psychologists have played a key role in this field from its inception and are positioned to be in critical leadership roles. This article has focused on increasing such leadership by moving away from traditional constraints (e.g., excessive emphasis on assessment), by purposefully changing the culture of pre-service and in-service education and training, and through specific strategies to expand perspectives and training experiences within school psychology training programs. This discussion has been occurring for at least a decade (see Ross et al., 2002 ); as exemplified in this special issue, there is critical momentum for a significant enhancement in leadership by school psychologists in SMH.

Contributor Information

JONI WILLIAMS SPLETT, University of South Carolina.

JOHNATHAN FOWLER, University of South Carolina.

MARK D. WEIST, University of South Carolina.

HEATHER MCDANIEL, University of South Carolina.

MELISSA DVORSKY, Virginia Commonwealth University.

R eferences

- Aarons GA (2004). Mental health provider attitudes toward adoption of evidence-based practice: The evidence-based practice attitude scale (EBPAS). Mental Health Services Research , 6 , 61–74. doi: 10.1023/B:MHSR.0000024351.12294.65. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ball A, Anderson-Butcher D, Mellin EA, & Green JH (2010). A cross-walk of professional competencies involved in expanded school mental health: An exploratory study. School Mental Health , 2 , 114–124. doi: 10.1007/s12310-010-9039-0 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Barrett S, Eber L, & Weist MD (2009). An interconnected systems framework for school mental health and PBIS National Technical Assistance Center for PBIS (Maryland site), funded by the Office of Special Education Programs, U.S. Department of Education; Retrieved from http://www.pbis.org/school/school_mental_health.aspx . [ Google Scholar ]

- Bramlett RK, Murphy JJ, Johnson J, Wallingsford L, & Hall JD (2002). Contemporary practices in school psychology: A national survey of roles and referral problems. Psychology in the Schools , 39 , 327–335. doi: 10.1002/pits.10022 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Briggs-Gowan MJ, Horwitz S, Schwab-Stone ME, Leventhal JM, & Leaf PJ (2000). Mental health in pediatric settings: Distribution of disorders and factors related to service use. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry , 39 , 841–849. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200007000-00012 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chorpita BF, & Daleiden EL (2009). Mapping evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents: Application of the distillation and matching model to 615 treatments from 322 randomized trials. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology , 77 , 566–579. doi: 10.1037/a0014565 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Clauss-Ehlers C, Serpell Z, & Weist MD (n press). Handbook of culturally responsive school mental health: Advancing research, training, practice, and policy New York, NY: Springer. [ Google Scholar ]

- Community-Campus Partnerships for Health. (2006). Principles of good community-campus partnerships Retrieved from http://depts.washington.edu/ccph/principles.html#principles

- Curtis MJ, Grier JEC, & Hunley SA (2003). The changing face of school psychology: Trends in data and projections for the future. School Psychology Quarterly , 18 , 409–430. doi: 10.1521/scpq.18.4.409.26999 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Curtis MJ, Hunley SA, Walker KL, & Baker AC (1999). Demographic characteristics and professional practices in school psychology. School Psychology Review , 28 , 104–116. [ Google Scholar ]

- Del’Homme M, Kasari C, Forness S, & Bagley R (1996). Prereferral intervention and students at risk for emotional and behavioral disorders. Education and Treatment of Children , 19 , 272–285. [ Google Scholar ]

- Durlak JA, Weissberg RP, Dymnicki AB, Taylor RD, & Schellinger KB (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development , 82 , 405–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Eber L, Sugai G, Smith CR, & Scott TM (2002). Wraparound and positive behavioral intervention and supports in the schools. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders , 10 , 171–180. doi: 10.1177/10634266020100030501 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ehrhardt-Padgett GN, Hatzichristou C, Kitson J, & Meyers J (2004). Awakening to a new dawn: Perspectives of the future of school psychology. School Psychology Review , 33 , 105–114. doi: 10.1521/scpq.18.4.483.26994 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fagan TK, & Wise PS (2007). School Psychology: Past, present, and future (3rd ed.). Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fixsen DL, Naoom SF, Blase KA, Friedman RM, & Wallace F (2005). Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature (FMHI Publication #231) Tampa: University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, The National Implementation Research Network. [ Google Scholar ]

- Flaherty LT, Garrison EG, Waxman R, Uris PF, Keys SG, Glass-Siegel M, & Weist MD (1998). Optimizing the roles of school mental health professionals. Journal of School Health , 68 , 420–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1998.tb06321.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Forness SR (2005). The pursuit of evidence-based practice in special education for children with emotional or behavioral disorders. Behavioral Disorders , 30 , 311–330. [ Google Scholar ]

- Foster S, Rollefson M, Doksum T, Noonan D, & Robinson G (2005). School mental health services in the United States, 2002–2003 Rockville, MD: Center for Mental Health Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [ Google Scholar ]

- Freeman R, Eber L, Anderson C Irvin L, Horner R, Bounds M, & Dunlap G (2006). Building inclusive school cultures using school-wide positive behavior support: Designing effective individual support systems for students with significant disabilities. Research & Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities , 31 , 4–17. doi: 10.2511/rpsd.31.1.4 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Friedrich A (2010). School-based mental health services: A national survey of school psychologists’ practices and perceptions Retrieved from http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/3549 .

- Gordon RS (1983). An operational classification of disease prevention. Public Health Reports , 98 , 107–109. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gresham FM (2004). Current status and future directions of school-based behavioral interventions. School Psychology Review , 33 , 326–343. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gresham FM (2008). Best practices in diagnosis in a multitier problem-solving approach. In Thomas A & Grimes J (Eds.), Best practices in school psychology V (pp. 281–294). Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists. [ Google Scholar ]

- Harrison PL, Cummings JA, Dawson M, Short RJ, Gorin S, & Palmoares R (2004). Responding to the needs of children, families, and schools: The 2002 Multisite Conference on the Future of School Psychology. School Psychology Review , 33 , 12–33. doi: 10.1521/scpq.18.4.358.27001 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hawken LS (2006). School psychologists as leaders in the implementation of a targeted intervention. School Psychology Quarterly , 21 , 91–111. doi: 10.1521/scpq.2006.21.1.91 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hawken LS, Adolphson SL, MacLeod KS, & Schumann J (2009). Secondary-tier interventions and supports. In Sailor W, Dunlap G, Sugai G, & Horner RH (Eds.), Handbook of positive behavior support (pp. 395–420). New York, NY: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-09632-2_17 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hill LG, Lochman JE, Coie JD, Greenberg MT, & Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. (2004). Effectiveness of early screening for externalizing problems: Issues of screening accuracy and utility. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology , 72 , 809–820. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.809 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hoagwood K, & Johnson J (2003). School psychology: A public health framework I. From evidence-based practices to evidence-based policies. Journal of School Psychology , 41 , 3–21. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4405(02)00141-3 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hoagwood K, Kratochwill T, Kerker B, & Olin S (2005). Integrating measurement of education and mental health outcomes for school mental health services: A research review Unpublished manuscript, Columbia University: New York, NY. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hoge MA, Morris JA, Daniels AS, Huey LY, Stuart GW, Adams N, .Dodge JM (2005). Report of recommendations: The Annapolis coalition conference on behavioral health work force competencies. Administration & Policy in Mental Health 32 , 651–663. doi: 10.1007/s10488-005-3267-x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Horner RH, Sugai G, & Anderson CM (2010). Examining the evidence base for school-wide positive behavior support. Focus on Exceptional Children , 42 , 1–16. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hosp JL, & Reschly DJ (2002). Regional differences in school psychology practice. School Psychology Review , 31 , 11–29. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hussey DL, & Guo S (2003). Measuring behavior change in young children receiving intensive school-based mental health services. Journal of Community Psychology , 31 , 629–639. doi: 10.1002/jcop.10074 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hynd G, & Obrzut J (1981). School neuropsychology. Journal of School Psychology , 19 , 45–50. doi: 10.1016/0022-4405(81)90006-6 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Joyce B, & Showers B (2002). Student achievement through staff development (3rd ed.). Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kern L, Hilt-Panahon A, & Sokol NG (2009). Further examining the triangle tip: Improving services for students with behavioral and emotional needs. Psychology in the Schools , 46 , 18–32. doi: 10.1002/pits.20351 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lochman JE, & the Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. (1995). Screening of child behavior problems for prevention programs at school entry. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology , 63 , 549–559. doi: 10.1037//0022-006X.63.4.549 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lloyd JW, Kauffman JM, Landrum TJ, & Roe DL (1991). Why do teachers refer pupils for special education? An analysis of referral records. Exceptionality , 2 , 115–126. doi: 10.1080/09362839109524774 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Markle B, Splett JW, Maras MA, & Weston KJ (in press). Effective school teams: Benefits, barriers, and best practices. In Weist MD, Lever N, Bradshaw C, & Owens J (Eds.), Handbook of school mental health: Research, training, practice, and policy (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Springer. [ Google Scholar ]

- McIntosh K, Campbell AL, Carter DR, & Zumbo BD (2009). Concurrent validity of office discipline referrals and cut points used in school-wide positive behavior support. Behavioral Disorders , 34 , 100–113. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mellin EA, Anderson-Butcher D, & Bronstein L (2011). Strengthening interprofessional team collaboration: Potential roles for school mental health professionals. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion , 4 , 51–61. doi: 10.1080/1754730X.2011.9715629 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Merikangas KR, He JP, Brody D, Fisher PW, Bourdon K, & Koretz DS (2010). Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders among US children in the 2001–2004 NHANES. Pediatrics , 125 , 75–81. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2598 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Meyers AB, & Swerdlik ME (2003). School-based health centers: Opportunities and challenges for school psychologists. Psychology in the Schools , 40 , 253–264. doi: 10.1002/pits.10085 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Meyers J, Meyers AB, & Grogg K (2004). Prevention through consultation: A model to guide future developments in the field of school psychology. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation , 15 , 257–276. doi: 10.1080/10474412.2004.9669517 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nastasi BK (2004). Mental health promotion. In Brown R (Ed.), Handbook of pediatric psychology in school settings Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. [ Google Scholar ]

- National Association of School Psychologists. (2010a). Model for comprehensive and integrated school psychological services Retrieved from. http://www.nasponline.org/standards/2010standards/2_PracticeModel.pdf

- National Association of School Psychologists. (2010b). Standards for graduate preparation of school psychologists Retrieved from http://www.nasponline.org/standards/2010standards/1_Graduate_Preparation.pdf

- National Association of School Psychologists. (2010c). Standards for the credentialing of school psychologists Retrieved from http://www.nasponline.org/standards/2010standards/2_Credentialing_Standards.pdf

- National Center on Response to Intervention. (2010, March). Essential components of RTI – a closer look at response to intervention Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs, National Center on Response to Intervention. [ Google Scholar ]

- Newell ML, Nastasi BK, Hatzichristou C, Jones JM, Schanding GT Jr., & Yetter G (2010). Evidence on multicultural training in school psychology: Recommendations for future directions. School Psychology Quarterly , 25 , 249–278. doi: 10.1037/a0021542 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Noltemeyer A, & McLaughlin CL (2011). School psychology’s Blueprint III: A survey of knowledge, use, and competence. School Psychology Forum: Research in Practice , 5 , 74–86. [ Google Scholar ]

- O’Connell ME, Boat T, & Warner KE (Eds.). (2009). Preventing mental, emotional and behavioral disorders among young people: Progress and possibilities Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Perfect MM, & Morris RJ (2011). Delivering school-based mental health services by school psychologists: Education, training, and ethical issues. Psychology in the Schools , 48 , 1049–1063. doi: 10.1002/pits.20612 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Quinn KP, & Lee V (2007). The wraparound approach for students with emotional and behavioral disorders: Opportunities for school psychologists. Psychology in the Schools , 44 , 101–111. doi: 10.1002/pits.20209 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Reinke WM, Splett JW, Robeson EN, & Offutt C (2009). Combining school and family interventions for the prevention and early intervention of disruptive behavior problems in children: A public health perspective. Psychology in the Schools , 46 , 33–43. doi: 10.1002/pits.20352. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Reschly DJ (2000). The present and future status of school psychology in the United States. School Psychology Review , 29 , 507–522. [ Google Scholar ]

- Reynolds CR (2011). Perspectives on specialization in school psychology training and practice. Psychology in the Schools , 48 , 922–930. doi: 10.1002/pits.20598 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ross MR, Powell SR, & Elias MJ (2002). New roles for school psychologists: Addressing the social and emotional learning needs of students. School Psychology Review , 31 , 43–52. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sandy M, & Holland B (2006). Different worlds and common ground: Community partner perspectives in campus-community partnerships. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning , 13 , 30–43. [ Google Scholar ]

- Severson HH, Walker HM, Hope-Doolittle J, Kratochwill TR, & Gresham FM (2007). Proactive, early screening to detect behaviorally at-risk students: Issues, approaches, emerging innovations, and professional practices. Journal of School Psychology , 45 193–223. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2006.11.003 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sheridan SM, & Gutkin TB (2000). The ecology of school psychology: Examining and changing our paradigm for the 21st century. School Psychology Review , 29 , 485–501. [ Google Scholar ]

- Splett JW (2012). Support system models of professional development to create lasting and systemic school improvements. The Community Psychologist , 45 , 26–29. [ Google Scholar ]

- Splett JW, & Maras MA (2011). Closing the gap in school mental health: A community-centered model for school psychology. Psychology in the Schools , 48 , 385–99. doi: 10.1002/pits.20561 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stoiber KC, & Vanderwood ML (2008). Traditional assessment, consultation, and intervention practices: Urban school psychologists’ use, importance, and competence ratings. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation , 18 , 264–292. doi: 10.1080/10474410802269164 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Suldo SM, Friedrich A, & Michalowski J (2010). Personal and system-level factors that limit and facilitate school psychologists’ involvement in school-based mental health services. Psychology in the Schools , 47 , 354–373. doi: 10.1002/pits.20475 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Turnbull A, Edmonson H, Griggs P, Wickham D, Sailor W, Freeman R, Warren J (2002). A blueprint for schoolwide positive behavior support: Implementation of three components. Exceptional Children , 68 , 377–402. [ Google Scholar ]

- Walker HM, Kavanagh K, Stiller B, Golly A, Severson HH, & Feil EG (1998). First step to success: An early intervention approach for preventing school failure. Journal of Emotional Behavior Disorders , 4 , 66–80. doi: 10.1177/106342669800600201 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Weist MD (2003). Promoting paradigmatic change in child and adolescent mental health and schools. School Psychology Review , 32 , 336–341. [ Google Scholar ]

- Weist MD, & Murray M (2007). Advancing school mental health promotion globally. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion , 1 [Inaugural Issue], 2–12. doi: 10.1080/1754730X.2008.9715740. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Weist MD, Rubin MR, Moore E, Adelsheim S, & Wrobel G (2007). Mental health screening in schools. Journal of School Health , 77 , 53–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00167.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Weist MD, Sanders MA, Walrath C, Link B, Nabors L, Adelsheim S, Carrillo K (2005). Developing principles for best practice in expanded school mental health. Journal of Youth and Adolescence , 34 , 7–13. doi: 10.1007/s10964-005-1331-1 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Weist MD, Stephan S, Lever N, Moore E, Flaspohler P, Maras M, Cosgrove TJ (2007). Quality and school mental health. In Evans S, Weist M, & Serpell Z (Eds.), Advances in school-based mental health interventions (pp. 4:1–4:14). New York, NY: Civic Research Institute. [ Google Scholar ]

- Yergat JD (2011). The augmented efficacy of PBS implementation (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database (UMI No. 3468207).

- Ysseldyke J, Burns M, Dawson P, Kelley B, Morrison D, Ortiz S, … Telzrow C (2006). School psychology: A blueprint for training and practice III Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists. [ Google Scholar ]

NASP: The National Association of School Psychologists

- NASP Research Reports

In This Section

- Virtual Poster Series

- Research Proposals

- School Psychology Workforce

- Research Summaries

- Member Surveys

- Strategic Goal Grant

- EDIJ Research Grants

Access more information about NASP Research Reports, including instructions to authors.

Volume 8, Issue 3 (2024, May)

2022–2023 ratio of students to full-time equivalent school psychologists in u.s. public elementary and secondary schools.

By Nicholas W. Affrunti

The current brief provides an overview of the 2022–2023 school year’s student to school psychologist ratio for every United States territory, using the National Center for Education Statistics counts of school psychologists. In addition to this, data are presented on the percentage change in student to school psychologist ratio from the 2021–2022 school year to the 2022–2023 school year (i.e., the currently released data). When territory ratios for the 2022–2023 school year were examined by region, the data displayed significant differences. No associations were found between the student to school psychologist ratio and territory population, the number of graduate programs in school psychology in that territory, or the average school psychologist salary. This information is vital for tracking workforce shortages, as well as the effects of advocacy efforts throughout the country.

Download this issue

Volume 8, Issue 2 (2024, March)

A model of school psychologist turnover.

By Nicholas W. Affrunti & Eric Rossen

This data brief presents a model of school psychologist turnover based on publicly available datasets. The model calculates the difference between the expected number of school psychologists for a current year by adding the number of school psychologists from the previous year with estimates of incoming graduates who work in schools. The number of school psychologists for that current year are then subtracted from the estimated total. This provides the estimated raw number of school psychologists who left the field in any given year. To obtain a percentage change that can be compared with other professions, the raw number of school psychologists who left in that year was divided by the current year’s total number of school psychologists. Based on this model, the rate of turnover for the 2020–2021 school year was 6.7%. The model is presented in more detail, and the implications of the model are discussed in this paper.

Volume 8, Issue 1 (2024, February)

Nasp report of graduate education in school psychology: 2021–2022.

By Daniel Gadke, Sarah Valley-Gray, & Eric Rossen

Each year the Graduate Education Committee of the National Association of School Psychologists (NASP) administers the National School Psychology Program Database Survey. Data regarding graduate education in school psychology have been collected annually for both specialist and doctoral programs since 2010. This report for the 2021–2022 academic year summarizes data solicited from the directors of all known school psychology programs and provides estimates regarding selected outcomes for those programs. During the 2021–2022 academic year, an estimated 12,090 current students (including interns) were enrolled in school psychology programs. Furthermore, an estimated 3,855 first year students were enrolled, whereas an estimated 3,409 students (2,904 specialist level and 505 doctoral level) graduated from school psychology programs. Approximately 89% of specialist-level program graduates work in schools. In contrast, approximately 39% of doctoral-level program graduates work in schools, while 8% of doctoral graduates work as faculty members within a university setting. Additional data include information regarding credit hour requirements, financial support, enrollment, internship placement, and student outcomes.

Volume 7, Issue 3 (2023, November)

Examining racial-ethnic and gender differences on the praxis school psychologist tests, september 2022–august 2023.

In this data brief, we examine the scores and pass rates for the Praxis School Psychologist tests (both Praxis 5402 and the newer version, Praxis 5403) by racial-ethnic group and gender for the period September 1, 2022 to August 31, 2023. The Praxis School Psychologist tests are the most often used external assessment of competency by school psychology programs and states and a passing score on the test is a requirement to earn the Nationally Certified School Psychologist (NCSP) credential. For this particular window of time, both versions of the test were available to test takers, with a passing score on either version accepted for NCSP applications. Data were provided to the National Association of School Psychologists (NASP) by the Educational Testing Service, including preset categories for racial-ethnic group and gender. The Praxis 5402 pass rates significantly differed by gender, though the Praxis 5403 did not significantly differ by gender. There were also significant differences in both the Praxis 5402 and the Praxis 5403 pass rates by race-ethnicity.

Volume 7, Issue 2 (2023, August)

Commentary on the racial, ethnic, and gender disparities in school psychology praxis exam outcomes.

By Bryn Harris, Miriam E. Thompson, Lindsay Fallon, & Amanda L. Sullivan

This commentary provides an external perspective on NASP’s first public report on racial and ethnic differences in Praxis outcomes. These data demonstrate racial disparities in pass rates but do not provide information regarding the causes of these disparities. This report underscores the need for expanded public reporting of Praxis data in order to facilitate research into program contexts for student success and whether there are systemic disparities in pass rates attributable to programmatic (e.g., type of institution, program training components and quality) and systemic considerations (e.g., racism, systemic oppression, bias among test content). Although we must maintain competencies for the practice of school psychology, the way in which we evaluate such competencies and the interpretation of Praxis test score data should be considered through a social justice lens. The report begins what we hope will be more transparency and ongoing dissemination and use of Praxis exam data to support equity.

Racial-Ethnic and Gender Breakdown of the Praxis Exam Scores and Pass Rates

In this data brief, we examine both the scores and pass rates for the Praxis 5402 School Psychology test (Praxis 5402) by racial-ethnic group and gender. The Praxis 5402 is the most often used external assessment in school psychology, and a passing score on the Praxis 5402 is a requirement to earn the Nationally Certified School Psychologist (NCSP) credential. Data were provided to the National Association of School Psychologists (NASP) by the Educational Testing Service (ETS), including preset categories for racial-ethnic group and gender. The Praxis 5402 pass rates did not significantly differ by gender. Although there were significant differences in Praxis 5402 pass rates by racial-ethnic grouping, all racial-ethnic groups, except for Pacific Islander (n = 7), had a pass rate of 89% or higher. The data within represent a step in better understanding the fairness of the Praxis 5402 test for all individuals.

Volume 7, Issue 1 (2023, April)

2021–2022 ratio of students to full-time equivalent (fte) school psychologists in u.s. public elementary and secondary schools.

The current brief provides an overview of the 2021–2022 school year student-to-school psychologist ratio for every United States territory, using the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) counts of school psychologists. In addition to this, data are presented on the percentage change in student-to-school psychologist ratio from the 2020–2021 school year to the 2021–2022 school year (i.e., most recently released data). When territory ratios for the 2021–2022 school year were examined by region, the Northeast region was found to have significantly smaller ratios (i.e., fewer students per school psychologist) than all other regions. No associations were found between the student-to-school psychologist ratio and territory population or number of graduate programs in school psychology in that territory. There was a significant association between the student-to-school psychology ratio and the average salary in that territory. This information is vital for tracking workforce shortages, as well as the effects of advocacy efforts, throughout the country.

Volume 6, Issue 3 (2022, November)

Nasp report of graduate education in school psychology: 2019-2020.

Each year the Graduate Education Committee of the National Association of School Psychologists (NASP) administers the National School Psychology Program Database Survey . Data regarding the status of graduate education in school psychology have been collected annually for both specialist and doctoral programs since 2010. This report for the 2019–2020 academic year summarizes data solicited from the directors of all known school psychology programs and provides estimates regarding selected outcomes for those programs. During the 2019–2020 academic year, an estimated 11,728 current students (including interns) were enrolled in school psychology programs. Furthermore, an estimated 3,600 first year students were enrolled, whereas an estimated 3,394 students (2,879 specialist-level and 515 doctoral-level) graduated from school psychology programs. Approximately 87% of specialist-level program graduates work in schools. In contrast, approximately 42% of doctoral-level program graduates work in schools, while 4% of doctoral graduates work as faculty members within a university setting. Additional data include information regarding credit hour requirements, financial support, enrollment, internship placement, and student outcomes.

Volume 6, Issue 2 (2022, July)

Ratio of students to full-time equivalent school psychologists in u.s. public elementary and secondary schools.

This data brief provides an overview of the 2020–2021 school year’s student to school psychologist ratio for every U.S. territory, using the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) counts of school psychologists. In addition to this, data are presented on the percentage change in student to school psychologist ratio from the 2019–2020 school year and the 2020–2021 school year (i.e., currently released data). When territory ratios for the 2020–2021 school year were examined by region, the Northeast region was found to have significantly smaller ratios (i.e., fewer students per school psychologist) than all other regions. No associations were found between the student to school psychologist ratio and territory population or number of graduate programs in school psychology in that territory. This information is vital for tracking workforce shortages, as well as the effects of advocacy efforts, throughout the country.

Volume 6, Issue 1 (2022, June)

Trends in graduate education in school psychology, 2015–2020.

By Eric Rossen, Daniel Gadke, & Sarah Valley-Gray

The Graduate Education Committee of the National Association of School Psychologists (NASP) has collected data regarding the status of graduate education in school psychology for both specialist and doctoral programs since 2010. This report highlights trends across a 5-year period from the 2015–2016 academic year through 2019–2020. The data highlight a generally positive outlook. The number of applicants, enrolled students, and graduates from school psychology programs continue to grow. The percent of minoritized students enrolled in school psychology programs has steadily increased over time as well. Additionally, more graduates than ever are estimated to enter the workforce, specifically in the school setting. However, these positive trends are almost entirely attributed to specialist-level programs; the data from doctoral-level programs indicate that the number of doctoral students enrolled, graduating, and working in schools has either remained the same or slightly decreased. Further, the number of available graduate programs overall (specialist-level or doctoral-level) remains generally stable with a slight increase over the 5-year period. This status quo may be insufficient to meet increasing demand for school psychological services coupled with an increasing pre-K–12 enrollment across the United States.

Volume 5, Issue 3 (2021, November)

Status of school psychology in 2020, part 2: professional practices in the nasp membership survey.

By Ryan L. Farmer, Anisa N. Goforth, Samuel Y. Kim, Shereen C. Naser, Adam B. Lockwood, & Nicholas W. Affrunti

In this second report on the 2020 NASP Membership Survey data, details regarding the professional practices of school psychologists employed in schools are highlighted (n = 1,006). The data suggest that school psychologists engage in assessment-related tasks above all other professional responsibilities, completing an average of 55 evaluations per year. Additionally, many, but not all, school psychologists are involved in mental health and behavioral health services, and involvement is dependent, in part, upon perceived competency. Additionally, the data suggest that the practices of school psychologists who serve more than 700 students were less likely to be consistent with the NASP Practice Model. Finally, only about 11% of school psychologists reported that they were knowledgeable about social justice. Implications of these results as well as recommendations for future research are discussed.

Volume 5, Issue 2 (2021, July)

Status of school psychology in 2020: part 1, demographics of the nasp membership survey.

By Anisa N. Goforth, Ryan L. Farmer, Samuel Y. Kim, Shereen C. Naser, Adam B. Lockwood, & Nicholas W. Affrunti

This report highlights the results from the 2020 NASP Membership Survey, with a particular focus on the demographics and employment settings of school psychologists. For the current survey, 30% of NASP’s regular and early career members were randomly selected by state of residence; 1,308 participants ultimately completed the survey. Results found that more than 80% of school psychologists identified as female, White, able-bodied, and monolingual. Further, the number of school psychologists with a specialist degree is increasing over time, while the number of school psychologists with doctoral degrees has remained steady. The average ratio of school psychologists-to-students was 1:1,233. Implications of these results are also discussed.

Volume 5, Issue 1 (2021, April)

Nasp report of graduate education in school psychology: 2018–2019.

By Daniel L. Gadke, Sarah Valley-Gray, & Eric Rossen

Each year, the Graduate Education Committee of the National Association of School Psychologists (NASP) administers the National School Psychology Program Database Survey. Data regarding the status of graduate education in school psychology have been collected annually for both specialist and doctoral programs since 2010. This report for the 2018–2019 academic year summarizes data solicited from the directors of all known school psychology programs and provides estimates regarding selected outcomes for those programs. During the 2018–2019 academic year, an estimated 10,173 current students (including interns) were enrolled in school psychology programs. Further, an estimated 3,128 first year students were enrolled, whereas an estimated 2,816 students (2,321 specialist-level, 495 doctoral-level) graduated from school psychology programs. Approximately 85% of specialist-level program graduates work in schools. In contrast, approximately 51% of doctoral-level program graduates work in schools, while 6% of doctoral graduates work as faculty members within a university setting. Additional data include information regarding credit hour requirements, financial support, enrollment, internship placement, and student outcomes.

Volume 4, Issue 2 (2019, August)

Nasp report of graduate education in school psychology: 2017–2018.

Each year the Graduate Education Committee of the National Association of School Psychologists (NASP) administers the National School Psychology Program Database Survey. Data regarding the status of graduate education in school psychology have been collected annually for both specialist and doctoral programs since 2010. This report for the 2017–2018 academic year summarizes data collected from the directors of all known school psychology programs and provides estimates regarding selected outcomes for those programs. During the 2017–2018 academic year, an estimated 10,121 current students (including interns) were enrolled in school psychology programs. Furthermore, an estimated 3,116 first year students were enrolled, whereas an estimated 2,708 students (2,198 specialist-level and 510 doctoral-level) graduated from school psychology programs. Approximately 90% of specialist-level program graduates work in schools. In contrast, approximately 60% of doctoral-level program graduates work in schools, while 14% of doctoral graduates work as faculty members within a university setting. Additional data include information regarding credit hour requirements, financial support, enrollment, internship placement, and student outcomes.

Volume 4, Issue 1 (2019, June)

Results from the nasp 2015 membership survey, part two: professional practices in school psychology.

By Kathleen M. McNamara, Christy M. Walcott, & Daniel Hyson

The National Association of School Psychologists (NASP) has conducted membership surveys every 5 years since 1990. In this (2015) version, surveys were completed by 1,274 NASP members, 990 of whom reported primary full-time employment as school psychologists in school settings. This is the second in a series of two reports of results, describing the professional practices of these school psychologists for the 2014-2015 school year, and examining trends in these practices over time. The report presents findings in the context of two of the five current (2017-2022) NASP Strategic Goals: (1) School psychologists, state education agencies, and local education agencies implement the NASP Model for Comprehensive and Integrated School Psychological Services; and (2) Advance the role of school psychologists as qualified mental and behavioral health providers. Results indicate that, while individual evaluations continue to play a major role in their daily activities, school psychologists also report noteworthy levels of engagement in consultation and collaboration targeting individual students' instructional needs, as well as services to enhance mental and behavior health.

Volume 3, Issue 2 (2018, November)

Nasp report of graduate education in school psychology: 2016–2017.

Each year the Graduate Education Committee of the National Association of School Psychologists (NASP) administers the National School Psychology Program Database Survey. Data regarding the status of graduate education in school psychology have been collected annually for both specialist and doctoral programs since 2010. This report for the 2016–2017 academic year summarizes data collected from the directors of all known school psychology programs and provides estimates regarding selected outcomes for those programs. During the 2016–2017 academic year, an estimated 10,209 students (including interns) were enrolled in school psychology programs. Further, an estimated 3,118 first-year students were enrolled, and an estimated 2,796 students (2,210 specialist-level and 586 doctoral-level) graduated from school psychology programs. Approximately 94% of specialist-level program graduates work in schools. In contrast, approximately 47% of doctoral-level program graduates work in schools, while 38% work as faculty members within a university setting. Additional data include information regarding credit hour requirements, financial support, enrollment, internship placement, and student outcomes.

Volume 3, Issue 1 (2018, June)

Results from the nasp 2015 membership survey, part one: demographics and employment conditions.

By Christy M. Walcott & Daniel Hyson

This report presents demographic and employment conditions for school psychologists in the 2014-2015 school year and trends in these conditions over time. The findings are organized around two of the five Strategic Goals of the National Association of School Psychologists (NASP), so as to inform advocacy initiatives and guide the work of the association. NASP has been conducting membership surveys every 5 years since 1990. In this most recent survey, 20% of NASP's regular and early career members were randomly selected by state of residence and invited by e-mail to participate. The final sample consisted of 1,274 respondents, representing a 48% response rate. Results indicate no change in the ratio of students per school psychologist since 2010, modest increases in the diversity of the workforce, and a decline since 2010 in the average age of school psychologists. Findings also suggest limited opportunities for leadership development and mentoring within school districts and minimal release time and financial reimbursement for professional development. Implications of the survey findings for how best to address workforce shortages and leadership development are discussed.

Volume 2, Issue 2 (2017, November)

Nasp report of graduate education in school psychology: 2015–2016 .

The National School Psychology Program Database Survey is an annual initiative of the Graduate Education Committee of the National Association of School Psychologists (NASP). While NASP has periodically collected data regarding graduate education in school psychology since the mid-1970s, data have been collected annually for both specialist and doctoral school psychology programs since 2010. The collection of these data aims to provide transparency regarding the status of graduate education in school psychology, inform the profession regarding emerging trends, and provide prospective students and other stakeholders with information regarding school psychology graduate programs. This report summarizes the data received from the directors of school psychology programs during the 2015–2016 academic year and provides estimates for selected outcomes for all programs. An estimated 9,797 current students (including interns) were enrolled in school psychology programs. Further, an estimated 3,003 first year students were enrolled, whereas an estimated 2,580 students (2,026 specialist-level; 554 doctoral-level) graduated. Additional data include information regarding credit hour requirements, financial support, enrollment, internship placement, and student outcomes.

Volume 2, Issue 1 (2017, May)

Factors associated with graduate students' decisions to enter school psychology .