Advertisement

Green criminological perspectives on dog-fighting as organised masculinities -based animal harm

- Open access

- Published: 23 September 2021

- Volume 24 , pages 447–466, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Angus Nurse ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2486-4973 1

6069 Accesses

3 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Dog-fighting was historically a working-class pursuit within predominantly white, working-class subcultures, representing a distinct type of organised animal exploitation. However, contemporary dog-fighting has moved way from its organised pit-based origins to encompass varied forms of organised activity including street dog-fighting in the form of chain fighting or chain rolling, the use of dogs as status or weapon dogs. This paper examines dog-fighting from a green criminological perspective as a distinct form of organised and subcultural crime. Analysis of UK legislation identifies that the specific offence of ‘dog-fighting’ does not exist. Instead, dog-fighting is contained within the ‘animal fighting’ offence, prohibited by provisions of the Animal Welfare Act 2006. However, beyond the actual fight activities (pitting dogs against each other or attacking humans), a range of other offences are associated with dog-fighting including: illegal gambling; attending dog-fighting events; animal welfare harms; and the breeding and selling of dogs for fighting. This paper’s analysis examines contemporary legal perspectives on such activities; also discussing how illegal fieldsports (e.g. dog-fighting and cock-fighting) are dominated by organised crime elements of gambling and distinctly masculine subcultures through which a hierarchy of offending is established and developed. Commensurate with previous research that identifies different offender behaviours and offending within animal crime, this paper concludes that variation exists in the nature of dog-fighting to the extent that a single approach to offenders and offending behaviour is unlikely to be successful.

Similar content being viewed by others

Policing the Crisis in the 21st Century; the making of “knife crime youths” in Britain

Semiotics of legal transplants: exploring domestic violence justice in uzbekistan.

The Impact of Islamophobia on the Persecution of Myanmar's Rohingya: A Human Rights Perspective

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Dog-fighting is a form of animal harm that over the years has been subject to criminalisation via laws protecting non-human animals from human exploitation (Nurse 2013 ). Footnote 1 Its situation within organised crime discourse also reflects its links with gambling, the group dynamics involved in its organisation and its association with gangs and youth culture. However, while discussion of dog-fighting often centres on one ‘traditional’ type of activity, contemporary dog-fighting has broadened from its organised pit-based origins to encompass varied forms of organised activity including street dog-fighting in the form of chain fighting or chain rolling and the use of dogs as status or weapon dogs (Harding and Nurse 2015 ). Thus, there are arguably not only different types of dog-fighting in existence but also varied types of organised crime involved in the activity and its associated illegal acts.

This article examines dog-fighting from a green criminological perspective as a distinct form of organised and subcultural crime. It considers the question ‘to what extent is dog-fighting characterised as organised crime and how does such classification influence the enforcement approach?’. It also considers the extent to which a green criminological perspective should be applied to such activity, considering the nature of animal harm within an ecological justice approach that applies concepts of justice beyond species boundaries (Benton 2007 ). UK dog-fighting is primarily caught within animal welfare legislation, which creates criminal offences in respect of harm caused to protected animals and any failure to provide appropriate standards of animal welfare (Nurse 2016 ; Nurse and Ryland 2014 ). However, beyond the actual fight activities (pitting dogs against each other or using dogs to attack other humans), a range of other offences are associated with dog-fighting including: illegal gambling; attending dog-fighting events; animal welfare harms; and the breeding and selling of dogs for fighting. This article’s analysis examines contemporary legal perspectives on such activities as part of the consideration of dog-fighting as a group activity that should be considered within a broader conception of criminal networks than might fit within normative conceptions of ‘organised’ crime (Nurse and Wyatt 2020 ). It identifies that various conceptions on organised crime exists and that dog-fighting activity exists within various structural conceptions. Thus, the paper’s analysis identifies how different types of organised activity are at work in dog-fighting. It also discusses how illegal fieldsports (e.g. dog-fighting and cock-fighting) are dominated by organised crime elements of gambling and distinctly masculine subcultures through which a hierarchy of offending is established and developed. This paper examines how the enforcement approach to dog-fighting arguably needs to consider the dynamics of group offending within dog-fighting activity.

This paper is largely theoretical and literature based in respect of advancing conceptions on organised crime and masculinities as a cause of dog-fighting activity. However, it also draws on the author’s prior research into wildlife and animal crime and makes use of both empirical research (including prior research) and documentary analysis. For this paper, a literature review was conducted in order to identify factors prevalent in dog-fighting and to examine; how dog-fighting is conceptualised in law; the different types of activity and behaviours that exist in dog-fighting and the enforcement response to dog-fighting. The literature selection considered the research question outlined earlier in the paper with a direct focus on examining how understanding of behaviours and motivations of those involved in dog-fighting are incorporated into enforcement and legislative approaches. Literature was considered that indicated the existence of masculinities within animal harm (Nurse 2013 ) or where evidence of a particularly male offending characteristic was present as a factor in animal harm or dog-fighting activity. The literature review examined prior research on animal fighting, animal abuse and dog-fighting and on enforcement approaches to dog-fighting and animal abuse. Studies in these areas have examined the extent to which violent male offenders are exposed to or are engaged in animal abuse alongside other activities such as illegal gambling. Studies have also considered the extent to which animal abuse can be characterised as a distinctly male activity where individuals’ criminal activity is linked to or reinforces their masculinity (Nurse 2013 ; Linzey 2009 ; Kimmel et al. 2005 ). Accordingly, this article examines what the available research reveals about the extent to which dog-fighting is primarily the preserve of male offenders. For example, an analysis of selected available prosecutions data was conducted in respect of animal abuse offending in the UK. The author’s research on dog-fighting in the UK, for example, identified that the majority of those prosecuted for dog-fighting offences (over 90%) are male (Harding & Nurse 2015 ).

During the period 2000 to 2008 the author also conducted research into wildlife crime, which has also informed this article's research. This prior research into wildlife crime conducted interviews with the majority of UK wildlife NGOs focused on the scale of wildlife crime, the nature of offending behaviour that contravened legislation, and the adequacy of UK law and enforcement approaches. The interviews provided considerable information on the nature of offenders involved in wildlife and animal crime, who are predominantly male. What emerged from the interviews and empirical research was a clearer picture of the nature of wildlife and animal crime in the UK as well as a picture of the types of offenders involved. One finding of the previous research was that whilst male offending dominated, offenders have different motivations and rationalisations for their offending (Nurse 2011 , 2013 ). Thus, rather than all animal offenders fitting into the perceived wisdom of the rationally driven, profit-motivated offender, a range of offender types exist, including that of the masculinities offender and different aspects of group offending.

In developing this article, information provided in the author’s earlier fieldwork and the evidence of previous studies into animal abuse and dog-fighting as well as the criminological literature on organised crime and legal and enforcement approaches to dog-fighting was considered. By combining this information this article seeks to evaluate the nature of dog-fighting, drawing on prior research, as well as the detail of dog-fighting law and the appropriate enforcement approach.

The Nature of Dog-Fighting

While it is beyond the scope of this article to provide an exhaustive description of dog-fighting’s rules and processes, some basic elements are accepted within definitions of dog-fighting. Evans et al ( 1998 : 827) define dog-fighting as ‘the act of baiting two dogs against each other for entertainment or gain. It involves placing two dogs in a pit until one either quits or dies.’ Integral to the conduct of a fight is that the two dogs are required to fight each other until there is a clear conclusion to the fight. As Lawson explains:

In its most extreme and organised form, dog fights will last until one dog fails to scratch (charge over their corner ‘’scratch line’, into the centre of the pit to engage with the other dog); jumps out of the pit, dies, or is declared the winner, which can take anything from just a few minutes up to a few hours. The losing dog, unless kept for breeding based on its bloodlines and past performances, may often be beaten, drowned, shot or strangled to death, sometimes on the night as entertainment for the other participants. ( 2017 : 343-344)

Notwithstanding this commonly accepted notion of dog-fighting as pit based activity, arguably there is variation in the different types of dog-fighting that can take place and thus variation in the behaviours of those involved and their motivations. Harding ( 2014 : 163) identified three levels of dog-fighting drawing on the work of Hardiman ( 2009 ) and Ortiz ( 2010 ) and as outlined in Table 1 below.

Thus, while pit-based dog-fighting takes place within what may be easily recognised as an organised and network-based structure, other kinds of activity take place including more informal types of dog-fighting. In addition, the differentiated nature of the activities and types of dog-fighting that take place also indicate that offenders have different motivations for engaging in dog-fighting. For example, at the more professional end, the nature of dog-fighting is such that adherents consider this to be a sport consisting of ‘highly organised events with their own subculture attached to them’ (Nurse 2013 : 43). This partially distinguishes the activity from that of the Hobbyists and ‘Off the Chain’ fights who operate within a ‘looser’ form of organisation including disorganised types of network (Wyatt et al. 2020 ). As with other forms of underground clandestine activity this complicates the accuracy of data on the amount of dog-fighting that takes place each year. Lawson’s analysis of dog fighting complaints and convictions recorded by the RSPCA for England and Wales from 2006 to 2015 identified a total of 4,855 complaints of organised fighting involving a dog. The total number of dogs involved in the complaints reported was 12,213. During the period of these complaints there were a total of 137 convictions (Lawson 2017 : 346). RSPCA figures for the following years show 15 convictions for Sect. 8 animal fighting in 2017, 17 in 2018 but none in 2019 (RSPCA 2020 : 16). Massagee ( 2015 ) suggests that dog-fighting in the US is a half a billion dollar industry, consistent with the view of a 2007 New York Times story that described it as a multi-million dollar industry. Following NFL star Michael Vick’s high profile conviction for dog-fighting (Coleman 2009 ) the BBC suggested the US industry to involve an estimated 40,000 people ‘using some 250,000 dogs’ (Smith-Spark 2007 ). The uncertain size of the industry notwithstanding, Smith ( 2011 ) argues that dog-fighting should be considered an illegal entrepreneurial crime because it is primarily committed for the purpose of financial gain. However, in the context of this paper’s overall research question, how dog-fighting is defined in law becomes important in considering whether it is or can be dealt with as animal crime or serious/organised crime.

Dog-Fighting Offences

Nurse and Harding ( 2016 : 2) identified that in the UK ‘dog-fighting laws exist within animal welfare and cruelty statutes to the extent that dog-fighting laws do not exist independently of general anti-cruelty statutes as is the case in the US’. Animal offences are frequently considered to be victimless crimes largely due to the reality that animals are generally considered to be property and not as victims according to legal classifications (Nurse 2016 ). However, US law (discussed later in this article) generally classes dog-fighting as a felony which carries much stiffer penalties than standard anti-cruelty laws. This felony status also influences law enforcement responses to dog-fighting, particularly that which is ‘organised’ in nature. While the seriousness of the activity is not in doubt, analysis of UK legislation identifies that the specific offence of ‘dog-fighting’ does not exist. Instead, the act of dog-fighting is contained within the more generalised ‘animal fighting’ offence, prohibited by provisions of the Animal Welfare Act 2006. This Act considers both direct participation in dog-fighting as well as indirect activities such as betting on dog-fights, attendance at such engagements and publicity of dog fights. It should also be noted that UK law regulates the breeding and selling of dogs considered to be fighting dogs, primarily through the Dangerous Dogs Act 1991. Footnote 2

Actual participation in dog-fighting is primarily covered by Sect. 8 of the UK’s Animal Welfare Act 2006 which states as follows:

A person commits an offence if he

causes an animal fight to take place, or attempts to do so;

knowingly receives money for admission to an animal fight;

knowingly publicises a proposed animal fight;

provides information about an animal fight to another with the intention of enabling or encouraging attendance at the fight;

makes or accepts a bet on the outcome of an animal fight or on the likelihood of anything occurring or not occurring in the course of an animal fight;

takes part in an animal fight;

has in his possession anything designed or adapted for use in connection with an animal fight with the intention of its being so used;

keeps or trains an animal for use for in connection with an animal fight;

keeps any premises for use for an animal fight.

Section 8(2) of the Act also makes it an offence for a person to be present at an animal fight without lawful authority or reasonable excuse. The offences outlined above relate to direct engagement with animal fighting and illustrate its perceived nature as a group activity, in particular one that involves spectators willing to pay admission for attendance and one that involves illegal gambling. The Act’s definition of animal fighting specifies it as ‘an occasion on which a protected animal is placed with an animal, or with a human, for the purpose of fighting, wrestling or baiting’ (Sect. 8 (7) of the Act). The specific wording used ‘makes clear that animal fighting is a tightly defined activity which in part is dependent on proving the intent of those involved in order to prove the commission of an offence’ (Nurse and Harding 2016 : 3). Potentially the specific wording ‘placed with’ would disqualify ‘impromptu’ street fights and chain rolling from a strict interpretation of dog-fighting as being deliberate and organised activity. Thus, such activities may be discounted by one notion of ‘organised’ crime, that concerning the structured and organised nature of animal fighting intended to be caught by the Animal Welfare Act 2006. But they would be caught by other provisions of UK legislation and they are applicable to this article’s wider consideration of dog-fighting as being an organised crime activity.

Beyond specific animal-fighting offences, the UK’s Animal Welfare Act 2006 also makes it an offence to cause suffering to a protected animal (dogs, cats and other companion animals are covered within this definition). Section 4 of the Act identifies that a person commits an offence if: (a) an act of his, or a failure of his to act, causes an animal to suffer, (b) he knew, or ought reasonably to have known, that the act, or failure to act, would have that effect or be likely to do so” (s. 4 AWA, 2006). Importantly this part of the Act relates to both deliberate acts, such as causing injury to a dog when using harsh and painful methods of training intended to toughen the dog and increase its endurance, as well as applying to omissions or negligence, such as failing to protect a dog from injuries inflicted during a fight. A failure to seek and provide immediate veterinary attention after a fight would also be action that prolongs a dog’s suffering and would be caught by this part of the Act. Section 9 of the Act places a duty on a person responsible for an animal to ensure animal welfare and states that ‘a person commits an offence if he does not take such steps as are reasonable in all the circumstances to ensure that the needs of an animal for which he is responsible are met to the extent required by good practice’ (Sect. 9(1) of the Animal Welfare Act 2006).

The injuries caused to a dog during dog-fighting could give rise to separate charges under Sect. 4 of the Act and arguably an owner (or responsible person) could be charged even where they may not directly participate in the alleged dog-fighting. Crucially, this widens the scope of charging those responsible for the dogs for the injuries incurred even if participation in the staging of a fight cannot be proved. The interpretation of this part of the law was clarified in R (on the application of Gray and Another) v Aylesbury Crown Court [2013] EWHC 500 (Admin). Gray, a horse farm trader was convicted of causing unnecessary suffering when the police seized 115 equines from his premises. Gray appealed against his convictions and argued that Sect. 4(1)(bb) of the Animal Welfare Act 2006 required either proof of knowledge that the animal was in a condition causing it unnecessary suffering or proof that it was showing signs of suffering which could not be missed by a reasonable, caring owner. In essence, Gray argued that for him to be convicted of the offence required either actual knowledge or a form of constructive knowledge that the animal was showing signs of unnecessary suffering, and so he argued that negligence (his failure to care for the animals so that they did actually suffer) was not sufficient. Footnote 3 The Court disagreed with Gray’s arguments and identified that Sect. 4(1)(bb) of the Animal Welfare Act 2006 had as its purpose the imposition of criminal liability for unnecessary suffering caused to an animal whether by act or omission and which the person responsible for the animal either had known or should have known was likely to cause unnecessary suffering whether by negligent act or omission The Court concluded that Sect. 9(1) of the 2006 Act also sets an objective standard of care which a responsible person is required to provide for the animal. As a result, the issue is whether the animal has suffered unnecessarily, not the mental state (i.e. level of knowledge or intent) of the person concerned. For dog-fighting offences, this raises a clear prospect that those involved in placing a dog into a fight and being present at the event where the injuries occur would have difficulty in arguing that they are not responsible under Sects. 4 or 9 of the Animal Welfare Act 2006.

In the US, dog-fighting is prohibited at both federal and state level. Federal criminalization of dogfighting is considered to be important ‘because it provides a system that overlaps state programs, allowing federal charges to be brought in instances where state enforcement is inadequate or non-existent or where state penalties are low’ (Ortiz 2010 : 21). Similar provisions to those that exist in the UK are contained in federal laws notably the Animal Fighting Prohibition Enforcement Act of 2007 which imposes a fine and/or prison term of up to three years for violations of the Animal Welfare Act relating to: (1) sponsoring or exhibiting an animal in an animal fighting venture; (2) buying, selling, transporting, delivering, or receiving for purposes of transportation, in interstate or foreign commerce, any dog or other animal for participation in an animal fighting venture; and (3) using the mails or other instrumentality of interstate commerce to promote or further an animal fighting venture (Congress 2007 ). The Animal Welfare Act was amended in 2014 when an additional prohibition against attending fighting events was added and provision was made to impose an additional penalty for bringing minors to fighting events. The “interstate or foreign commerce” requirement of the AWA gives the federal court jurisdiction over an activity otherwise regulated by the state.

Green Criminology, Dog-Fighting and Animal Exploitation

Green criminology has identified how non-human animals are often commodified through laws that, for example, allow the continued exploitation of wildlife as an exploitable resource. It has also explored the potential shortcomings of legal systems and enforcement practices that fail to adequately provide justice for non-human animals and that may consider animal crimes as somehow victimless (Sollund 2017 ; Nurse 2015 ). Green criminology’s ecological justice conception ‘refers to the relationship of human beings generally to the rest of the natural world’ (White 2008 : 18). This incorporates a focus on ensuring that non-human animals can live free from torture, abuse and the destruction of their habitats and that policy and justice systems consider and incorporate mechanisms for providing justice when human considerations and behaviour prove to be problematic in respect of animals. Green criminology further develops these concerns within its species justice concept which ‘includes the particular consideration that animal welfare and rights ought to be of relevance to eco-justice’ (White and Heckenberg 2014 : 49). However, non-human animals’ status as ‘property’ is integral to the perpetuation of anthropocentric views that generally limit legal protection to the extent to which non-human animal and human interests coincide (Wise 2000 ). The green criminological perspective considers this to be problematic and discussions of speciesism have identified it as ‘the practice of discriminating against non-human animals because they are perceived to be inferior to the human species in much the same way that sexism and racism involve prejudice and discrimination against women and people of different colour’ (White and Heckenberg 2014 : 49). Thus, green criminology identifies that many animal crimes fall outside of the mainstream criminological gaze and contends that this is a short-sighted approach that fails to align animal abuse with other violent crimes. While several social fieldsports (such as hunting, shooting and fishing) are lawful if carried out in accordance with regulations that may specify when non-human animals can be killed or taken and may restrict the methods that might be used in killing or taking non-human animals, illegal activities such as ‘hunting with dogs or animal baiting, have been criminalised by various jurisdictions yet continue as underground ‘sports’ despite the illegality of doing so (Nurse and Wyatt 2020 :52; Kalof and Taylor 2007 ; Smith 2011 ). Undoubtedly dog-fighting constitutes a form of animal harm which prior green criminological research has defined as:

Animal harm is any unauthorized act or omission that violates national or international animal law whether anti-cruelty, conservation, animal protection, wildlife or general law that contains animal protection provisions (including the protection of animals as property) and is subject to either criminal prosecution and criminal sanctions, including cautioning and disposal by means other than a criminal trial or which provides for civil sanctions to redress the harm caused to the animal whether directly or indirectly. Animal harm may involve injury to or killing of animals, removal from the wild, possession or reducing into captivity, or the sale or exploitation of animals or products derived from animals. Animal harm also includes the causing of either physical or psychological distress. (Nurse 2013 : 57).

Kalof and Taylor ( 2007 : 330) identify that as green criminology ‘seeks to understand and confront the social problem of animal cruelty’ it is well placed to develop or contribute to a discourse of dog-fighting centred around the physical, psychological and emotional abuse of the non-human animals themselves. However, situating dog-fighting within mainstream law enforcement efforts also requires negating anthropocentric viewpoints towards non-human animals that limit the priority given to their harm. Accordingly, this article contends that the animal harm concerns are best allied to organised crime concerns which law enforcement is already predisposed to take seriously. This is particularly the case in respect of masculinities based group offending.

Dog-Fighting and Masculinity Subculture

Maher and Pierpoint ( 2011 ) identify a level of social anxiety in the UK centred around the perception of a status dogs’ problem where youth dog ownership of so called ‘dangerous dogs’ relates to extrinsically motivated dog ownership linked to criminal and anti-social purposes. In the UK context, the term ‘status dog’ generally refers to breeds historically considered to be fighting dogs such as the bull breeds (e.g. Staffordshire bull terrier American Pit Bull terrier, American Bully). Ownership of these dogs has been documented ‘to confer an image of toughness, an air of aggression, and their use as an extension of UK youth gang violence (for example as weapons in turf wars)’ (Maher et al 2017 : 132). Research has also identified that masculinities offences, particularly those linked to direct exploitation of non-human animals, are seldom committed by lone individuals (Nurse 2013 ). In some of these crimes (e.g. pit-based dog-fighting) ‘the main motivation is the exercise of power allied to sport or entertainment’ which often links with organised crime and gambling (Nurse 2020 :915).

Sykes and Matza’s neutralization theory ( 1957 ) can be applied to the justifications used by offenders that gives them the freedom to act (and a post-act rationalization for doing so) while other theories explain why animal harm offenders are motivated to commit specific crimes (Nurse 2013 ). Animal offenders often exist within distinct communities where the crimes take place, frequently outside of the gaze of the wider community by virtue of being an underground or hidden activity and there is a lack of disapproving neighbours or a distinct law enforcement presence to exert essential controls on offending (especially in respect of wildlife offences which often take place in remote areas). Offenders may also live within a community or subculture of their own which accepts their offences. Nurse ( 2013 ) identified that many animal harm offences carry only fines or lower level prison terms which reinforce the notion of animal harm as ‘minor’ offences unworthy of official activity within mainstream criminal justice. In addition, Sutherland’s ( 1973 ) differential association theory helps to explain the situation that occurs when potential animal abusers and wildlife offenders learn their activities from others in their community or social group (Sutherland 1973 ). Communities engulfed in subcultural acceptance of animal harm can encourage the main learning process for criminal behaviour within intimate groups and association with others and provide the organisational structure that facilities, encourages and supports deviant behaviour like illegal dog-fighting. Such offending also fits within the notion of crimes of masculinities involving cruelty to, or power over, animals, in some cases linked to sporting or ‘hobby’ pursuits, perceptions by the offender of their actions being part of their culture where toughness, masculinity and smartness (Wilson 1985 ) combine with a love of excitement. In the case of animal baiting sports (e.g. badger-baiting, badger-digging, hare coursing, dog-fighting and cock-fighting) for example, gambling and association with other like-minded males are factors and provide a strong incentive for new members to join already established networks of offenders.

American research on non-human animal and wildlife-oriented crimes of the masculine, including cockfighting and cock-fighting gangs, illustrate the existence of such masculine subcultures. Thus, “cock-fighting can be said to have a mythos centered on the purported behaviour and character of the gamecock itself. Cocks are seen as emblems of bravery and resistance in the face of insurmountable odds” (Hawley 1993 , 2). Gullone ( 2012 :13) noted dog-fighting as fitting into one of Kellert and Felthous’ ( 1985 ) nine motivations for animal cruelty, namely that of the expression of aggression through a non-human animal. Footnote 4 Maher et al ( 2017 ) identify the cyclical nature of status dog ownership and anti-social behaviour as arguably self-reinforcing such that dogs:

(1) Are labelled as aggressive, dangerous and linked to criminality (for example dog-fighting, (2) are established as valued amongst deviant youth; (3) become further associated with oppositional culture and are labelled as socially deviant and vilified by mainstream society, (4) have their status elevated amongst deviant youths and those pursuing anti-social or criminal activities (Ragatz et al. 2009 and Schenk et al. 2012 ), and (55) are abandoned, rejected and killed by mainstream society (including non-deviant bull-breed owners). Moreover ownership of these dog breeds then becomes a tool with which society can label antisocial youth and other owners.

Thus, societal condemnation of status dog-ownership risks enforcing notions of masculinity linked to the perceived outlaw status of the dogs themselves and their acceptance as an illicit commodity. Engagement in ‘animal fighting’ activity heightens this as the fighting involved is ‘an affirmation of masculine identity in an increasingly complex and diverse era’ (Hawley 1993 , 1), and the fighting spirit of the birds or dogs has great symbolic significance to participants as does the ability of fighting and hunting dogs to take punishment. Thus, such activities arguably speak to distinctly male characteristics and provide a means through which masculine stereotypes can be reinforced and developed through offending behaviour (Goodey 1997 ) and are important factors in addressing offending behaviour that may sometimes be overlooked (Groombridge 1998 ).

The male-bonding element of animal fighting identified by Hawley is significant to considerations of the organised nature of animal abuse, as is the banding together of men from the margins of society or from a shared cultural background for whom issues of belonging, male pride, and achievement are important. Such considerations can be powerful factors in the development of a subculture where offending activity is accepted by participants, spectators and support networks. In discussing cock-fighting in America, Hawley ( 1993 ) explains that ‘young men are taken under the wing of an older male relative or father, and taught all aspects of chicken care and lore pertaining to the sport. Females are generally not significant players in this macho milieu’ although special events for women ‘powder puff’ derbies are sometimes arranged (Hawley 1993 , 5). Forsyth and Evans ( 1998 ) reached similar findings in researching dog-fighting in the United States, illustrating how Sykes and Matza’s ( 1957 ) neutralization techniques might be deployed to defend and justify the animal abuse and illegal activity linked to such offending. Forsyth and Evans noted that in order to maintain rationalizations concerning their activities, ‘the dogmen use four recurring techniques: (a) denial of injury; (b) condemnation of the condemners; (c) appeal to higher loyalties; and (d) a defense that says dogmen are good people (their deviance-dogfighting expunged by their good character)’ (1998: 2013). Thus, preservation of and pride in their sport as a historical practice, an attachment to smaller groups and loyalty to dogfighting and dogmen took precedence over attachment to society for the dogmen, with dog-fighting having great cultural significance and wider social importance for the dogmen and other masculinities offenders. Harding and Nurse’s research into UK dog-fighting (2015, 2016) also identified the importance of a masculine group dynamic and, in an analysis of dog-fighting activity and prosecutions in the United Kingdom, also noted the extent to which dog-fighting had become a masculinities-based group activity on the part of different participants (e.g. organisers, participants and spectators).

Previous research (Nurse, 2013 ) indicates that as a causation of animal harm, the denial of injury is an important factor indicating not only that individuals do not see any harm in their activity but also confirming the view of animals as a commodity rather than as sentient beings suffering as a result of the individual’s actions. In addition, the perception that certain animals do not feel pain allows offenders to commit their offences without considering the impact of their actions or feeling any guilt over them. However, in dog-fighting, it is precisely the animal’s ability to endure pain and to inflict it on an opponent that is integral to the activity’s appeal. Those involved identify with these masculine traits in their dogs and work hard to ensure that they are brought out. At the more professional end of dog-fighting (see Table 1 ) organisational structures are in place to support such ideologies.

Dog-Fighting and Organised Crime

Kalof and Taylor ( 2007 ) estimated that more than 40,000 dog fighters were active in urban centres of the United States at the time of their analysis. They also identified that ‘some dog fighters are skilled professionals who operate in national and international clandestine networks, but others are mid-level dog fighters who remain in specific geographical regions’ (2007: 324). Smith ( 2011 ) identified that activities such as dog-fighting take place in a closed social milieu to which the authorities and the academic researcher cannot legitimately gain access. Harding and Nurse ( 2016 ) identified that while dog-fighting is classified primarily as animal welfare and animal abuse crime it is also a distinctly status crime. However, the illegal activities associated with dog-fighting can legitimately be regarded as being an entrepreneurial activity as they entail trading in a Kirznerian sense as well as financial implications associated with gambling (Smith, 2011 ).

Throughout the literature on dog-fighting a picture emerges of varied types of organised activity. In their analysis of organised crime in the illegal wildlife trade Wyatt et al. ( 2020 ) identified three types of organised crime groups, organised, corporate and disorganised groups. Two of these groups are clearly involved in illegal dog-fighting, organised and disorganised groups. Wyatt et al.’s definition of organised groups concluded that these are ‘highly-organized, disciplined, rational, and may use violence or corruption to control illegal goods and/or services for profit. In addition, the group has existed for a significant length of time’ ( 2020 : 353). Wyatt et al. 2020 : 353) note that in respect of some animal related crimes, the nature of the organisation and the crime need not define a crime as ‘serious’ according to the United Nations definition of seriousness as “conduct constituting an offence punishable by a maximum deprivation of liberty of at least four years or a more serious penalty” (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) 2004 : 5). Arguably there is also some corporate crime involvement allied to dog-fighting particularly in respect of its ancillary activities, the lucrative world of dog-fighting merchandise (such as recordings of fights, prohibited under the UK’s Animal Welfare Act 2008) and the commercialised nature of high-end dog-fighting which involves thousands of pounds in high end gambling and that sometimes involves interstate activity. Professional dog-fighting is often discussed in the context of a dog-fighting network or ‘ring’. Thus, it lends itself to consideration within normative considerations of hierarchical organised crime. Smith ( 2011 ) identified dog-fighting as being organised criminal activity that was engaged in by urban criminals and especially by organised thieves and drug dealers. As Heger ( 2011 :242) identified, dog fights ‘require networking, preparation, and coordination between at least two, and typically three or more, parties such as kennels, dog ―sponsors, referees, the fight promoter, and spectators’. Accordingly, ‘dogfights often mark the synchronization of criminal efforts from various players, all linked together through their common purpose of the fighting ring’’ (Heger 2011 : 242). The prevalence of gambling and the large sums of money to be made from organised dog-fighting means that the ‘sport’ attracts the involvement of organised crime wishing to take advantage of the sport’s profits. As Kalof and Taylor noted in assessing research on dog-fighting in Detroit ‘organised dog fights emerge as serious racketeering activities – business ventures that draw a cross section of spectators from the middle class, the working class, the wealthy and the street culture’ ( 2007 : 326).

At the ‘disorganised’ end, dog-fighting is inextricably linked to inner city gang culture where dogs are seen as status symbols and are also used for security and enforcement. As this article identifies, varied forms of dog-fighting exist and the more informal types of dog-fighting reflect Wyatt et al.’s ( 2020 ) notion of disorganisation and Reuter’s ( 1986 ) conception of disorganised crime, notwithstanding the fact that the violence visited on each other by the dogs is undoubtedly violence. But as Table 1 (earlier) indicates, the ‘impromptu’ street rolls and low-level dog-fighting are distinguished from the pit-based and more organised variant, reflecting a notion of being conducted by parties who are less organised or monopolistic in their organisation and purpose. Thus, urban street culture dog-fighting represented by ‘Off the Chain’ fights and the ‘Hobbyists’ are arguably closer to a conception of disorganised crime than the clearly organised crime fights of the professional rings. This variance in behaviour has implications for the enforcement approach to dog-fighting.

Prosecuting Dog-Fighting

Given the organised but underground nature of dog-fighting, standard animal welfare enforcement approaches are arguably inadequate to address the full range of offending incorporated within dog-fighting. Most animal welfare and many animal abuse offences are dealt with by a mixture of police and animal welfare charities. Thus, bodies such as the RSPCA, SSCPCA, RSPCA (Australia), the League Against Cruel Sports (LACS) and the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) may routinely find themselves the first port of call for dealing with harm to or neglect of an animal. This may include injuries arising from dog-fighting and in some cases animal welfare charities with investigative departments will also liaise with policing agencies in anti-dog-fighting operations.

However, whereas much animal abuse or animal welfare offending might not be considered a policing priority, dog-fighting attracts the attention of police and prosecutors ‘because those engaged in animal fighting also tend to be involved in additional criminal conduct, such as gambling, guns and illegal drugs’ (Schaffner 2011 : 35). Nurse ( 2013 ) identified that the public policy response to masculinities crimes such as dog-fighting reflects acceptance of the propensity towards violence of offenders involved in such offences. However, by necessity, dog-fighting investigations may be complex and require techniques such as infiltration of gangs, surveillance activities, undercover operations and in-depth financial investigations. Investigations can also be lengthy and resource intensive. For example, Masagee ( 2015 :2) notes that the conviction of an Alabama dog-fight organiser to an eight-year prison term came only after a four-year investigation. Ortiz ( 2010 ) suggested that dog-fighting attracted a low level of prosecution in the US. The reasons for this were identified as ‘differences in the values people place on prosecution, the costs involved in investigating cases, and the difficulties of proving the criminal violations’ (Ortiz 2010 : 27). The valuation of animal crime as not being a mainstream enforcement priority has been commented on by several green criminologists and arguably reflects anthropocentric notions of animals as property. Ortiz suggested that ‘even between those states that agree that dogfighting should be a certain category (felony or misdemeanour), criminal sanctions for the activity differ which shows a different value for the crime’ ( 2010 : 28). Maximum penalties for dog-fighting offences were recently increased in the UK by virtue of the Animal Welfare (Sentencing) Act 2021 which increased maximum penalties from to five years for offences under any of Sects. 4, 5, 6(1) and (2), 7 and 8 of the Animal Welfare Act 2006. This captures offences of causing unnecessary suffering to a dog (Sect. 4) and relating to animal fighting (Sect. 8).

The costs of conducting investigations become problematic when the possible conclusions of a ‘successful’ investigation are that seized dogs must be housed, often at considerable expense, or may need to be euthanised. Where dog-fighting is a mutli-jurisdictional problem (for example involving several different US states or even more than one country), investigative costs could increase and this may discourage authorisation for investigation. Heger notes ‘the largest fight-ring bust in the U.S. entailed acquiring remote farmland, purchasing forty fight dogs, keeping two officers undercover for eighteen months, and participating in fights’ ( 2011 :254). The case resulted in more than 500 dogs being rescued from twenty-nine sites from across eight states. While there were twenty-six arrests ‘the resulting convictions ranged from twenty-four months in federal prison down to only probation’ while the costs of caring for the seized animals were estimated at $350,000 (Heger 2011 :254). While this one large case is unlikely to be typical, it does represent a problem that green criminologists identify in other areas of non-human animal crime, namely that without recognition of the harm caused to animals by such offending or a clear link to more ‘mainstream’ offending that criminal justice agencies understand, such offences may remain under-prosecuted (Nurse 2015 ).

Dog-fighters also represent a particular type of masculinities offender (Nurse 2013 ) considered to be more dangerous than other animal offenders (with the possible exception of wildlife crime’s organised gangs) and evidence suggests that investigations also need to be tailored with this in mind and taking into account the likely benefits at the conclusion of an investigation. The challenges of proving animal fighting violations were noted by Nurse and Harding ( 2016 ) who concluded that ‘dog-fighting offences may not always be prosecuted or identified as such given the nature of harms caused to dogs during fighting activities and the availability of ‘lesser’ but more easily provable offences such as failure to provide animal welfare’. From an animal welfare perspective, the relative ease of proving that harm to an animal has occurred and thus, in the UK at least, the duty to provide animal welfare has not been met and thus an offence has occurred. However, the organised crime elements of dog-fighting offences require more extensive consideration particularly in respect of the linked illegal action. Thus, arguments have been made that prosecutorial approaches more explicitly routed in organised crime discourse should be employed.

In US dog-fighting discourse arguments have been made for use of the federal Racketeering Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO), which was included in the Organised Crime Control Act of 1970., RICO was arguably originally conceived as an anti-mafia tool, but has developed to engage with other forms of corruption and organised activity. The four key themes of RICO are that:

First, income acquired through racketeering or illegal debts may not be used to purchase interest in an enterprise. Second, the racketeering proceeds or illegal debts may not themselves be used to gain or maintain interest in an enterprise. Third, an enterprise may not conduct its affairs through a pattern of racketeering or the collection of illegal debts. Finally, any conspiracies to commit the above acts are prohibited. (Heger 2011 : 256).

RICO charges may be based either on a ‘pattern of racketeering’ or on the collection of unlawful debt notwithstanding some of the challenges of establishing that a pattern of racketeering exists (Massagee 2015 : 1). Racketeering as defined by the statute refers to committing any of the approximately one hundred offenses or ‘predicate offenses’ specifically listed within the RICO statute. However, while 187 predicate offenses include certain state charges involving, for example, murder, kidnapping, gambling, arson, robbery, bribery, extortion, dealing in obscene matter, or dealing in a controlled substance, as well as an expansive list of federal offenses, ‘neither dogfighting nor other Animal Welfare Act violations are listed as predicate offenses under the RICO statute’ (Heger 2011 : 257).

While it is beyond the scope of this article to explore RICO or its equivalents in depth, the application of legislation that gives options to enforcers and prosecutors options to consider the organised crime elements of racketeering as part of dog-fighting prosecutions provides some hope for addressing the animal abuse aspects of such offences alongside the organised elements. Heger ( 2011 : 270) argues that RICO is appropriate given the business-like nature of associated dog-fighting crimes as well as some of the evidential/proof issues in dog-fighting statutes. The Animal Legal Defense fund identified that most states have RICO statutes and that ‘as of January 2018, New Jersey and Texas have made dog fighting a predicate RICO offense; and Kansas has made both dog fighting and cockfighting predicate offenses’ (ALDF 2019 ). Notably, 6 US states have made all animal fighting predicate offences.

The importance of applying RICO or other organised crime tools to dog-fighting is that while a focus on the dogs is core concern of animal welfare and animal protection law, use of organised crime tools also provides a mechanism for more serious penalties, such as seizure of assets and equipment. It also brings dog-fighting within the remit of mainstream law enforcement arguably better resourced to conduct such investigations whilst ensuring the associated animal abuse is brought clearly within the remit of public prosecutors.

Conclusions on Dog-Fighting and Organised Crime

The paper has considered the extent to which dog-fighting is characterised as organised crime and whether any such classification influences or assists enforcement approaches. Commensurate with previous research that identifies different offender behaviours and offending exist within animal crime (Nurse 2011 ; 2013 ), this paper’s examination concludes that variation exists in the nature of dog-fighting to the extent that a single approach to offenders and offending behaviour is unlikely to be successful. There are different types of dog-fighting as well as different motivations and engagement with associated illegal activity. But the underlying conclusion is that dog-fighting operates within organised and disorganised structures and is primarily a group activity.

At the more ‘professional’ end, dog-fighting engages with normative organised crime behaviour such as illegal gambling, racketeering and the engagement of criminal networks in lucrative, illegal activity. At the lower end of the scale, there is less organisation and arguably a level of disorganisation, that nevertheless engages with illegal gambling (in respect of the ‘Hobbyists) and is gang affiliated. The differences in types of offender and behaviour should be considered when developing enforcement and prosecution strategies and perhaps preventative ones. But underlying the different types of dog-fighting are key issues of masculinities and anthropocentric attitudes towards animals as property to be exploited and used for human entertainment.

Legislatively dog-fighting offences are primarily considered within animal welfare and animal protection law. But from a green criminological perspective, the harms caused to non-human animals are a primary concern, where dog-fighting and other animal harm activities need to be considered not just in the context of whether they are organised or serious crime that criminology and criminal justice would normally consider, but also because they represent crimes against animals that are of significance to how society deals with violence and deviance (Nurse 2016 ; Beirne 2007 ). Thus, justice approaches need to consider how to address anthropocentric attitudes towards non-human animals and the failure to afford appropriate priority to these even where legislation mechanisms exist. But as this article outlines, an effective response requires allying the animal harm aspects with the organised crime aspects in order to holistically address the realities of contemporary dog-fighting as both animal abuse crime and organised crime.

Heger ( 2011 ) suggested one approach to professional dog-fighting offences was to ‘follow the money’. At the more professional end where the illegal gambling aspects involve large sums of money in the hundreds of thousands and a higher level of sophistication exists in the breeding and handling of dogs and in financial arrangements, not only is dog-fighting highly organised, it is also big business. Thus, in addition to the investigative techniques of surveillance, infiltration and undercover work and assessment of harm caused to dogs already identified as appropriate law enforcement techniques for this kind of crime, other techniques such as forensic accounting and the investigation of assets (including the dogs themselves) that are linked to or a consequence of dog-fighting are also appropriate. Calculating how organised networks and individuals within those networks have profited from dog-fighting, provides a means to pursue seizure of any assets and the forfeiture of profits derived from dog-fighting, as a clear objective of the prosecutorial process. In principle this approach can also be applied to the gambling profits and assets of the disorganised dog-fighting networks.

For both the organised and disorganised end, addressing the animal abuse aspects is also necessary and a priority from a species justice perspective. Fighting dogs suffer abuse and a range of harms in training, during fights and frequently afterwards (especially those dogs that lose their fights). Animal welfare law often contains provisions that allow for individuals caught abusing animals to be banned from future animal ownership. These provisions should be routinely and stringently applied and those who fail to protect their dogs from the harms intrinsic to dog-fighting by virtue of their involvement in the activity should be prevented from having dogs by way of a lifetime ban. For the law to be effective in this area it needs to ensure not only that there is investigation and prosecution when dog-fighting is suspected, but once proved (and ideally convicted) preventative measures are also put in place to address the potential for reoffending.

The term non-human animal is used throughout this article although it should be noted that legislation usually uses the term ‘animal’, and this is used for accuracy in the names of legislation and when quoting directly from prior and legislative sources.

For criminological analysis of this legislation see, for example, Hallsworth ( 2011 ).

Gray also raised arguments that his convictions under Sect. 9 of the Act amounted to duplication because they were based on the same issues and findings of fact relating to his convictions under Sect. 4. These arguments were essentially dismissed, and the appeal judge concluded that there was not complete duplication as some of the animals that had been the subject of charges under Sect. 9 had not also been the subject of charges under Sect. 4.

For further discussion of dog-fighting as symbolic masculinity and expression of aggression see, for example Kalof 2014 , Kavesh 2019 , Alonso-Recarte 2020 .

Alonso-Recarte C (2020) Pit Bulls and Dogfighting as Symbols of Masculinity in Hip Hop Culture. Men Masculinities 23(5):852–871. https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X20965455

Article Google Scholar

Animal Legal Defense Fund (2019) Animal Fighting: State Laws. Available at: https://aldf.org/article/animal-fighting-facts/animalfighting-state-laws/ . Accessed 1 Dec 2020

Beirne P (2007) Animal rights, animal abuse and green criminology. In: Berine Piers, South Nigel (eds) Issues in Green Criminology. Willan Publishing, Cullompton

Google Scholar

Benton T (2007) Ecology, community and justice: the meaning of green. In: Berine Piers, South Nigel (eds) Issues in Green Criminology. Willan Publishing, Cullompton

Coleman PG (2009) Note to athletes, NFL, and NBA: Dog fighting is a crime, not a sport. J Anim Law Ethics 3:101–135

Congress (2007) H.R.137 - 110th Congress (2007–2008): Animal Fighting Prohibition Enforcement Act of 2007. Library of Congress, U.S. Congress. Available at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/110th-congress/housebill/137#:~:text=Animal%20Fighting%20Prohibition%20Enforcement%20Act%20of%202007%20-,to%20promote%20or%20further%20an%20animal%20fighting%20venture . Accessed 12 Dec 2020

Evans R, Gauthier DK, Forsyth CJ (1998) Dog Fighting: expression and validation of masculinity. Sex Roles 39(11/12):825–838

Forsyth CJ, Evans RD (1998) Dogmen: The Rationalisation of Deviance. Soc Anim 6(3):203–218

Goodey J (1997) Masculinities, Fear of Crime and Fearlessness. Br J Sociol 37(3):401–418

Groombridge N (1998) Masculinities and Crimes Against the Environment. Theor Criminol 2(2):249–267

Gullone E (2012) Animal Cruelty, Antisocial Behaviour and Aggression. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

Book Google Scholar

Hallsworth S (2011) Then they came for the dogs! Crime Law Soc Change 55:391–403. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-011-9293-6#

Hardiman T (2009) Dog-fighting, Humane Society of the United States. Available at: https://www.humanesociety.org/issues/dogfighting . Accessed 17 Sept 2015

Harding S (2014) Unleashed: The Phenomenon of Status Dogs and Weapon Dogs. Policy Press, Bristol

Harding S, Nurse A (2015) Analysis of UK dog fighting, laws and offences . Project Report. Middlesex University, London

Hawley F (1993) The Moral and Conceptual Universe of Cockfighters: Symbolism and Rationalization. Soc Anim 1(2):159–168

Heger MC (2011) Bringing RICO to the Ring: Can the Anti-Mafia Weapon Target Dogfighters? Wash Univ Law Rev 89(1):241–271

Kalof L, Taylor C (2007) The discourse of dog fighting. Humanit Soc 31:319–333

Kalof L (2014) Animal Blood Sport: A Ritual Display of Masculinity and Sexual Virility. Sociol Sport J 31(4):438–454

Kavesh MA (2019) Dog Fighting: Performing Masculinity in Rural South Punjab, Pakistan. Society and Animals 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685306-12341606

Kellert SR, Felthous AR (1985) Childhood Cruelty towards animals among criminals and noncriminals. Human Relations 38(12):1113–1129

Kimmel M, Hearn J, Connell RW (2005) Handbook of studies on men and masculinities. Sage, London, UK

Lawson C (2017) Animal Fighting. In: Maher Jennifer, Pierpoint Harriet, Beirne Piers (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Animal Abuse Studies. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

Linzey A (ed) (2009) The link between animal abuse and human violence. Sussex University Press, Brighton

Maher J, Pierpoint H, Lawson C (2017) Status Dogs. In: Maher Jennifer, Pierpoint Harriet, Beirne Piers (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Animal Abuse Studies. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

Chapter Google Scholar

Maher J, Pierpoint H (2011) Friends, status symbols and weapons: the use of dogs by youth groups and youth gangs. Crime Law Soc Chang 55(5):405–420

Massagee, C. (2015) Prosecuting Dogfighting: The Case for the Expansion of the Federal RICO Statute. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2600232 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2600232 . Accessed 20 Jan 2021

Nurse A (2011) Policing Wildlife: Perspectives on Criminality in Wildlife Crime. Papers from the British Criminology Conference 11:38–53

Nurse A (2012) Repainting the thin green line: The enforcement of UK wildlife law. Internet Journal of Criminology, October 2012. Available at: https://958be75a-da42-4a45-aafa-549955018b18.filesusr.com/ugd/b93dd4_4b720aabf88442f29fec2bec2ff6fee6.pdf . Accessed 10 Dec 2019

Nurse A (2013) Animal Harm: Perspectives on Why People Harm and Kill Animals. Ashgate, Farnham, UK

Nurse A (2016) Beyond the property debate: animal welfare as a public good. Contemporary Justice Review 19(2):174–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/10282580.2016.1169699

Nurse A (2015) Policing Wildlife: Perspectives on the Enforcement of Wildlife Legislation. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

Nurse A (2020) Masculinities and Animal Harm. Men Masculinities 23(5):908–926

Nurse A, Harding S (2016) Contemporary dog-fighting law in the UK. J Anim Welfare Law. http://bornfree.codeomega.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Wade_Draper.pdf

Nurse A, Ryland D (2014) Cats and the Law: A Plain English Guide. The Cat Group, London

Nurse A, Wyatt T (2020) Wildlife Criminology. Bristol University Press, Bristol

Ortiz F (2010) Making the dogman heel: recommendations for improving the effectiveness of dogfighting laws. Stanford Journal of Animal Law and Policy 3:1–75

Ragatz L, Fremouw W, Thomas T, McKoy K (2009) Vicous Dogs: The antisocial behaviours and psychological characteristics of owners. J Forensic Sci (Am Acad Forensic Sci) 54(3):699–703

RSPCA (2020) RSPCA Prosecutions Annual Report 2019. Horsham: RSPCA. Available at: https://www.rspca.org.uk/documents/1494939/7712578/Prosecutions+Annual+Report+2019+%28PDF+1.83MB%29.pdf/5a5a3644-ea97-606e-cce1-373159a0a7c6?t=1583770854006 . Accessed 10 Dec 2020

Reuter P (1986) Disorganized crime. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

Schaffner JE (2011) An Introduction to Animals and the Law. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

Schenk AM, Ragatz LL, Fremouw WJ (2012) Vicious Dogs part 2: Criminal thinking, callousness, and personal styles of their owners. J Forensic Sci (Am Acad Forensic Sci) 57(1):152–159

Smith R (2011) Investigating financial aspects of dog-fighting in the UK. Journal of Financial Crime 18(4):336–346

Smith-Spark L (2007) Brutal culture of US dog-fighting., BBC News. Available at: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/americas/6960788.stm . Accessed 10 Dec 2020

Sollund R (2017) The animal other: Legal and Illegal Theriocide. In: Hall M, Maher J, Nurse A, Potter G, South N, Wyatt T (eds) Greening Criminology in the 21 st Centuryy. Routledge, Abindgon

Sutherland EH (1973) On Analysing Crime. edited by K. Schuessler. University of Chicago Press (original work published 1942), Chicago

Sykes GM, Matza D (1957) Techniques of Neutralization: A Theory of Delinquency. Am Sociol Rev 22:664–673

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) (2004) United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime and the Protocols thereto. https://www.unodc.org/documents/treaties/UNTOC/Publications/TOC%20Convention/TOCebook-e.pdf . Accessed 30 Jul 2021

White R (2008) Crimes Against Nature: Environmental Criminology and Ecological Justice. Willan Publishing, Cullompton

White R, Heckenberg D (2014) Green Criminology: An Introduction to the Study of Environmental Harm. Routledge, London

Wilson JQ (1985) Thinking about Crime, 2nd edn. Vintage Books, New York

Wise S (2000) Rattling the Cage: Towards Legal Rights for Animals. Profile Books, London

Wyatt T, van Uhm D, Nurse A (2020) Differentiating criminal networks in the illegal wildlife trade: Organized, corporate and disorganized crime. Trends Organ Crime 33:350–366. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-020-09385-9

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Nottingham Trent University, 50 Shakespeare Street, Nottingham, NG1 4FQ, UK

Angus Nurse

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Angus Nurse .

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest.

There are no potential conflicts of interest. The author has previously been funded by the League against Cruel Sports, an NGO involved in combatting bloodsports but the submitted research was not funded by this or any other such organisation. The research did not involve any human participants as it was primarily desk/doctrinal research and also did not involve any animals. All research conducted by the author is in compliance with his institutional ethical requirements.

There are no images or third-party data that require informed consent, references to and acknowledgements of other work referred to in the submitted piece have been duly incorporated.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Nurse, A. Green criminological perspectives on dog-fighting as organised masculinities -based animal harm. Trends Organ Crim 24 , 447–466 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-021-09432-z

Download citation

Accepted : 31 August 2021

Published : 23 September 2021

Issue Date : December 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-021-09432-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Green criminology

- Animal harm

- Masculinities

- Species justice

- Animal welfare

- Organised crime

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 03 May 2021

Aggressive behaviour is affected by demographic, environmental and behavioural factors in purebred dogs

- Salla Mikkola 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Milla Salonen 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Jenni Puurunen 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Emma Hakanen 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Sini Sulkama 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- César Araujo 1 , 2 , 3 &

- Hannes Lohi 1 , 2 , 3

Scientific Reports volume 11 , Article number: 9433 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

89k Accesses

25 Citations

625 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Animal behaviour

- Animal physiology

- Behavioural ecology

- Ecological epidemiology

- Risk factors

Aggressive behaviour is an unwanted and serious problem in pet dogs, negatively influencing canine welfare, management and public acceptance. We aimed to identify demographic and environmental factors associated with aggressive behaviour toward people in Finnish purebred pet dogs. We collected behavioural data from 13,715 dogs with an owner-completed online questionnaire. Here we used a dataset of 9270 dogs which included 1791 dogs with frequent aggressive behaviour toward people and 7479 dogs without aggressive behaviour toward people. We studied the effect of several explanatory variables on aggressive behaviour with multiple logistic regression. Several factors increased the probability of aggressive behaviour toward people: older age, being male, fearfulness, small body size, lack of conspecific company, and being the owner’s first dog. The probability of aggressive behaviour also differed between breeds. These results replicate previous studies and suggest that improvements in the owner education and breeding practices could alleviate aggressive behaviour toward people while genetic studies could reveal associated hereditary factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Aggressiveness, ADHD-like behaviour, and environment influence repetitive behaviour in dogs

Inadequate socialisation, inactivity, and urban living environment are associated with social fearfulness in pet dogs

Active and social life is associated with lower non-social fearfulness in pet dogs

Introduction.

Aggressive behaviour is a serious and common behaviour problem in domestic dogs 1 . Aggressively behaving dogs can cause public concern by biting people and other pets, with medical or even lethal consequences for the victim. In some countries, certain dog breeds are even banned or are under breed-specific restriction in order to minimize the potential risk of dog bites 2 , 3 . Additionally, aggressive behaviour often leads to surrender or even euthanasia of the dog 4 , disposing the aggressively behaving individuals to welfare problems. Aggressive behaviour can also arise from pain 5 , 6 , suggesting that some aggressively behaving dogs may have a disease, such as hip dysplasia 7 , or other painful condition which impair their welfare.

The severity of aggressive behaviour varies from biting and snapping attacks that can even lead to the death of a victim to less severe, but more common growling and barking 8 . When including these less severe signs of aggressive behaviour, the aggressive behaviour toward people are quite common in pet dogs even though the reported proportions differ depending on the study approaches and study populations. In Iran, 26% of dogs showed aggressive behaviour toward strangers in a pilot study 9 , and in an English dog population 3% of dogs showed aggressive behaviour toward family member, and 5–7% toward strangers 10 . In a Finnish dog population, in the study of Tiira et al. 11 , the proportion of aggressive behaviour toward the owner/family members and toward strangers/familiar people were 16% and 45%, respectively. However, in our more recent prevalence study from Finnish dogs, aggressive behaviour was less common: the prevalence of total aggressive behaviour in this study population was 14%, aggressive behaviour toward (human) family members 6.4%, and toward strange people 6% 12 . The different criteria to categorise a dog as aggressive or non-aggressive explains the differences in the reported percentages of dogs showing aggressive behaviour. For example, in our more recent study 12 , we only considered dogs that had growled at least often or had tried to bite or snap at least sometimes as aggressive, while Tiira et al. 11 , considered all dogs that had barked, growled, snapped, or bit at least once as aggressive. Thus, in our study aggressive behaviour toward people includes frequent growling, snapping and biting or trying to snap or bite.

Aggressive behaviour in dogs has been associated with several factors. Some of these identified factors are dog-related, for example, dog’s fearfulness 11 , 13 , older age 10 , 14 , 15 , and being male 1 , 14 . The association with sterilisation is inconsistent, as studies have showed a lower probability of overall aggressive behaviour in sterilised than intact dogs 1 , a higher probability (toward owner) of aggressive behaviour in sterilised dogs 14 , and no connection between sterilisation and aggressive behaviour 14 , 15 , 16 . Some previous studies have also identified size as an affecting factor, with small dogs behaving more likely aggressively than large dogs 17 , 18 . Differences in aggressive behaviour between breeds have also been studied before, and several studies have detected significant breed-wise differences 11 , 12 , 14 , 19 . In addition, various environmental factors have been associated with aggressive behaviour. For example, dogs living in a single-dog household have been found to more likely behave aggressively toward the owner than dogs living in multi-dog household 14 , 20 , and dogs living in larger families have been found to be more prone to aggressive behaviour 14 , 15 . Dogs living in rural areas have been found to more likely behave aggressively toward strangers than dogs living in cities 14 . Furthermore, time spent with the owner 14 , and owner’s dog experience 14 , 20 , 21 , 22 have been associated with aggressiveness, and early weaning has been suggested to increase the probability of aggressive behaviour 23 .

We studied the factors associated with canine aggressive behaviour toward people (strangers and family members) in over 9000 Finnish purebred pet dogs with multiple logistic regression and we also formed a priori hypotheses based on previous literature. The dataset we used in this study is part of our larger owner-completed online questionnaire data with over 13,700 dogs 12 . Reliability of questionnaires is usually good, reflecting the behaviour of a dog in behaviour tests 24 , 25 and over time 25 . An owner-questionnaire can even be a better method to study aggressive behaviour than behaviour tests, because all dogs that have behaved aggressively in daily life do not show aggressive behaviour in test situations 26 , 27 . Here, our aim was to study the association of known (living environment, family size, dogs in the family, owner’s dog experience, daily exercise) and novel (daily time spent alone, weaning age) factors with aggressive behaviour in a previously unstudied dog population.

Study cohort and demographics

We studied factors associated with aggressive behaviour in Finnish pet dogs with an owner-completed online questionnaire and collected a cross-sectional convenience sample of 9270 dogs, including 1791 dogs in the high and 7479 dogs in the low aggressive behaviour groups. The mean age of the dogs was 4.6 years (ranging from 2 months to 17 years) and 53% of them were female. The number of dogs in different breed, sex, and aggressive behaviour groups are shown in the Supplementary Table S1 . We have a manuscript about study participants in preparation.

Factors associated with aggressive behaviour

The final logistic regression model for aggressive behaviour included explanatory variables age, sex, fearfulness, breed, dogs in the family, body size, and owner’s dog experience (Table 1 ).

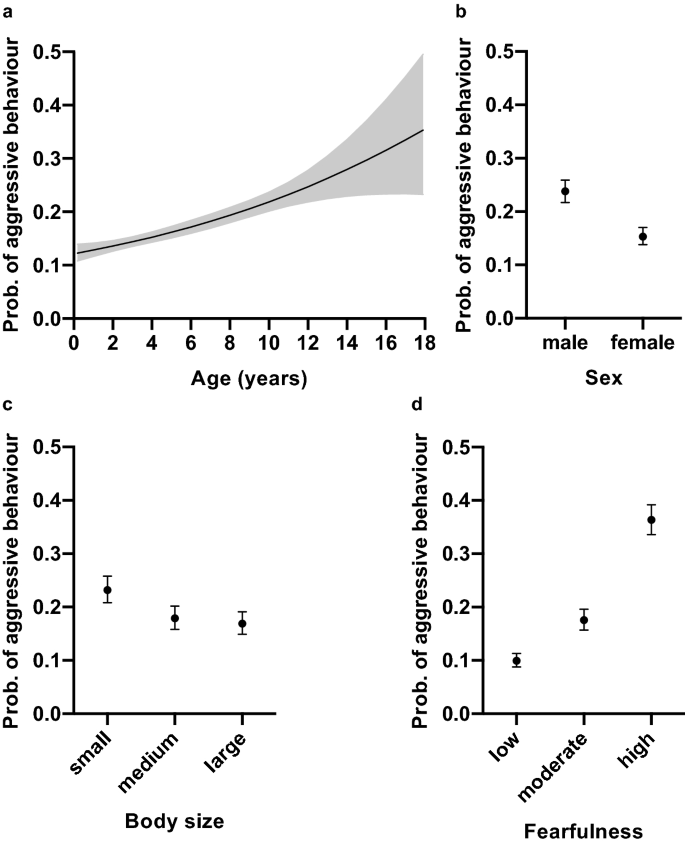

The probability of aggressive behaviour correlated positively with age, with older dogs having a higher odds of aggressive behaviour than young dogs (Fig. 1 a, Table 1 ). As hypothesised, male dogs had a higher odds of aggressive behaviour than female dogs (Fig. 1 b, Table 2 ). The dog’s body size was also associated with aggressive behaviour; small dogs had a higher odds of aggressive behaviour than medium-sized and large dogs, but there was no difference between medium-sized and large dogs (Fig. 1 c, Table 2 ). Highly fearful dogs had over five times higher odds of aggressive behaviour than non-fearful dogs and moderately fearful dogs also had a higher odds of aggressive behaviour than non-fearful dogs (Fig. 1 d, Table 2 ).

The effect of age, fearfulness, sex, and, body size on aggressive behaviour in the logistic regression analysis. ( a ) Older dogs had a higher probability of aggressive behaviour than young dogs. ( b ) Male dogs had a higher probability of aggressive behaviour than female dogs. ( c ) Small dogs had a higher probability of aggressive behaviour than medium-sized and large dogs. ( d ) Highly and moderately fearful dogs had a higher probability of aggressive behaviour than non-fearful dogs. Grey area ( a ) and error bars ( b – d ) indicate 95% confidence limits. N = 9270.

The probability of aggressive behaviour differed between breeds (Fig. 2 ). When adjusting for other variables in the model, the breeds with the highest odds of aggressive behaviour were Rough Collie, Miniature Poodle (toy, miniature and medium-sized), and Miniature Schnauzer. The breeds with the lowest odds of aggressive behaviour were Labrador Retriever, Golden Retriever, and Lapponian Herder. As we hypothesised a priori, Lagotto Romagnolo, Chihuahua, German Shepherd Dog, and Miniature Schnauzer had a significantly higher odds for aggressive behaviour than Golden Retriever and Labrador Retriever (Table 2 ). The largest pairwise differences were found between Rough Collie and Labrador Retriever (OR = 5.44, P = 0.0011), Miniature Poodle and Labrador Retriever (OR = 5.13, P = 0.0011), and Miniature Schnauzer and Labrador Retriever (OR = 5.08, P = 0.0011). Rest of the significant pairwise comparisons between breeds can be seen in the Supplementary Table S2 , and all pairwise breed differences are presented in the “ Supplementary Dataset ”.

Probability of aggressive behaviour in 23 dog breeds or breed groups. Several breeds differed significantly from each other (Supplementary Table S2 ). Error bars indicate 95% confidence limits. N = 9270.

In addition to demographic factors, environmental factors also influenced aggressive behaviour. Dogs living without other dogs in the household had a higher odds for aggressive behaviour than dogs living with other dogs (Table 2 , Supplementary Fig. S1 ). In addition, dogs of first-time dog owners had a higher odds of aggressive behaviour (Table 2 , Supplementary Fig. S1 ) than dogs belonging to owners who have had at least one dog previously.

This large-scale survey study of over 9000 pet dogs suggests that aggressive behaviour toward people is affected by behaviour, demography, and environment. The studied factors daily time spent alone, and weaning age were novel, and factors living environment, family size, dogs in the family, dog experience, daily exercise, have previously been studied only in few articles 14 , 15 , 20 , 21 , 22 . Dogs showing aggressive behaviour were more often fearful, small-sized, males, owner’s first dogs and the only dogs in the family. In addition, probability of aggressive behaviour increased with age, and we found that the probability of aggressive behaviour differed between dog breeds. These findings suggest that improvements in the owner education and breeding practices of pet dogs could alleviate aggressive behaviour toward people. The identified factors should also be considered when planning studies that aim for the discovery of the associated hereditary factors.

Fearfulness had the strongest association with aggressive behaviour. Fearful and noise-sensitive dogs have been found to behave more aggressively toward unfamiliar people than dogs with no anxieties 11 . In the study of Dinwoodie et al. 28 , the dogs with fear/anxiety problem had more biting incidences than other dogs, and they also found remarkable comorbidity between fear/anxiety and overall aggressive behaviour. Similarly, in the study of Salonen et al. 12 , comorbidity between fearfulness and aggressive behaviour was strong: aggressive dogs were over three times more often fearful than non-aggressive dogs. Aggressive behaviour commonly stems from fearfulness, as fear-related aggressive behaviour is a type of undesired aggressive behaviour 13 , 29 . Here, we could not separate fear-related aggressive behaviour from other types of aggressive behaviour. Therefore, it is possible that majority of the dogs in this study show fear-related aggressive behaviour.

We found a significant association between sex and aggressive behaviour. Male dogs had a higher probability of aggressive behaviour than females. This association has been found before in some studies 1 , 28 , 29 , but Hsu et al. 14 found this association only with aggressive behaviour toward the owner and Bennett and Rolf 15 did not find association with unfriendliness/aggressiveness. In addition, in the study population of Guy et al. 30 , female dogs were more likely to have bitten than male dogs. Thus, more studies are needed to reveal the association of sex and aggressive behaviour.