How to Use a Conceptual Framework for Better Research

A conceptual framework in research is not just a tool but a vital roadmap that guides the entire research process. It integrates various theories, assumptions, and beliefs to provide a structured approach to research. By defining a conceptual framework, researchers can focus their inquiries and clarify their hypotheses, leading to more effective and meaningful research outcomes.

What is a Conceptual Framework?

A conceptual framework is essentially an analytical tool that combines concepts and sets them within an appropriate theoretical structure. It serves as a lens through which researchers view the complexities of the real world. The importance of a conceptual framework lies in its ability to serve as a guide, helping researchers to not only visualize but also systematically approach their study.

Key Components and to be Analyzed During Research

- Theories: These are the underlying principles that guide the hypotheses and assumptions of the research.

- Assumptions: These are the accepted truths that are not tested within the scope of the research but are essential for framing the study.

- Beliefs: These often reflect the subjective viewpoints that may influence the interpretation of data.

- Ready to use

- Fully customizable template

- Get Started in seconds

Together, these components help to define the conceptual framework that directs the research towards its ultimate goal. This structured approach not only improves clarity but also enhances the validity and reliability of the research outcomes. By using a conceptual framework, researchers can avoid common pitfalls and focus on essential variables and relationships.

For practical examples and to see how different frameworks can be applied in various research scenarios, you can Explore Conceptual Framework Examples .

Different Types of Conceptual Frameworks Used in Research

Understanding the various types of conceptual frameworks is crucial for researchers aiming to align their studies with the most effective structure. Conceptual frameworks in research vary primarily between theoretical and operational frameworks, each serving distinct purposes and suiting different research methodologies.

Theoretical vs Operational Frameworks

Theoretical frameworks are built upon existing theories and literature, providing a broad and abstract understanding of the research topic. They help in forming the basis of the study by linking the research to already established scholarly works. On the other hand, operational frameworks are more practical, focusing on how the study’s theories will be tested through specific procedures and variables.

- Theoretical frameworks are ideal for exploratory studies and can help in understanding complex phenomena.

- Operational frameworks suit studies requiring precise measurement and data analysis.

Choosing the Right Framework

Selecting the appropriate conceptual framework is pivotal for the success of a research project. It involves matching the research questions with the framework that best addresses the methodological needs of the study. For instance, a theoretical framework might be chosen for studies that aim to generate new theories, while an operational framework would be better suited for testing specific hypotheses.

Benefits of choosing the right framework include enhanced clarity, better alignment with research goals, and improved validity of research outcomes. Tools like Table Chart Maker can be instrumental in visually comparing the strengths and weaknesses of different frameworks, aiding in this crucial decision-making process.

Real-World Examples of Conceptual Frameworks in Research

Understanding the practical application of conceptual frameworks in research can significantly enhance the clarity and effectiveness of your studies. Here, we explore several real-world case studies that demonstrate the pivotal role of conceptual frameworks in achieving robust research conclusions.

- Healthcare Research: In a study examining the impact of lifestyle choices on chronic diseases, researchers used a conceptual framework to link dietary habits, exercise, and genetic predispositions. This framework helped in identifying key variables and their interrelations, leading to more targeted interventions.

- Educational Development: Educational theorists often employ conceptual frameworks to explore the dynamics between teaching methods and student learning outcomes. One notable study mapped out the influences of digital tools on learning engagement, providing insights that shaped educational policies.

- Environmental Policy: Conceptual frameworks have been crucial in environmental research, particularly in studies on climate change adaptation. By framing the relationships between human activity, ecological changes, and policy responses, researchers have been able to propose more effective sustainability strategies.

Adapting conceptual frameworks based on evolving research data is also critical. As new information becomes available, it’s essential to revisit and adjust the framework to maintain its relevance and accuracy, ensuring that the research remains aligned with real-world conditions.

For those looking to visualize and better comprehend their research frameworks, Graphic Organizers for Conceptual Frameworks can be an invaluable tool. These organizers help in structuring and presenting research findings clearly, enhancing both the process and the presentation of your research.

Step-by-Step Guide to Creating Your Own Conceptual Framework

Creating a conceptual framework is a critical step in structuring your research to ensure clarity and focus. This guide will walk you through the process of building a robust framework, from identifying key concepts to refining your approach as your research evolves.

Building Blocks of a Conceptual Framework

- Identify and Define Main Concepts and Variables: Start by clearly identifying the main concepts, variables, and their relationships that will form the basis of your research. This could include defining key terms and establishing the scope of your study.

- Develop a Hypothesis or Primary Research Question: Formulate a central hypothesis or question that guides the direction of your research. This will serve as the foundation upon which your conceptual framework is built.

- Link Theories and Concepts Logically: Connect your identified concepts and variables with existing theories to create a coherent structure. This logical linking helps in forming a strong theoretical base for your research.

Visualizing and Refining Your Framework

Using visual tools can significantly enhance the clarity and effectiveness of your conceptual framework. Decision Tree Templates for Conceptual Frameworks can be particularly useful in mapping out the relationships between variables and hypotheses.

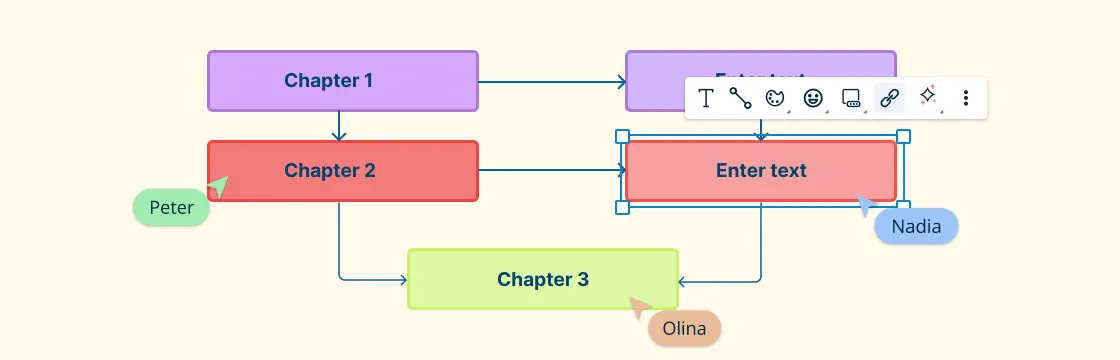

Map Your Framework: Utilize tools like Creately’s visual canvas to diagram your framework. This visual representation helps in identifying gaps or overlaps in your framework and provides a clear overview of your research structure.

Analyze and Refine: As your research progresses, continuously evaluate and refine your framework. Adjustments may be necessary as new data comes to light or as initial assumptions are challenged.

By following these steps, you can ensure that your conceptual framework is not only well-defined but also adaptable to the changing dynamics of your research.

Practical Tips for Utilizing Conceptual Frameworks in Research

Effectively utilizing a conceptual framework in research not only streamlines the process but also enhances the clarity and coherence of your findings. Here are some practical tips to maximize the use of conceptual frameworks in your research endeavors.

- Setting Clear Research Goals: Begin by defining precise objectives that are aligned with your research questions. This clarity will guide your entire research process, ensuring that every step you take is purposeful and directly contributes to your overall study aims. \

- Maintaining Focus and Coherence: Throughout the research, consistently refer back to your conceptual framework to maintain focus. This will help in keeping your research aligned with the initial goals and prevent deviations that could dilute the effectiveness of your findings.

- Data Analysis and Interpretation: Use your conceptual framework as a lens through which to view and interpret data. This approach ensures that the data analysis is not only systematic but also meaningful in the context of your research objectives. For more insights, explore Research Data Analysis Methods .

- Presenting Research Findings: When it comes time to present your findings, structure your presentation around the conceptual framework . This will help your audience understand the logical flow of your research and how each part contributes to the whole.

- Avoiding Common Pitfalls: Be vigilant about common errors such as overcomplicating the framework or misaligning the research methods with the framework’s structure. Keeping it simple and aligned ensures that the framework effectively supports your research.

By adhering to these tips and utilizing tools like 7 Essential Visual Tools for Social Work Assessment , researchers can ensure that their conceptual frameworks are not only robust but also practically applicable in their studies.

How Creately Enhances the Creation and Use of Conceptual Frameworks

Creating a robust conceptual framework is pivotal for effective research, and Creately’s suite of visual tools offers unparalleled support in this endeavor. By leveraging Creately’s features, researchers can visualize, organize, and analyze their research frameworks more efficiently.

- Visual Mapping of Research Plans: Creately’s infinite visual canvas allows researchers to map out their entire research plan visually. This helps in understanding the complex relationships between different research variables and theories, enhancing the clarity and effectiveness of the research process.

- Brainstorming with Mind Maps: Using Mind Mapping Software , researchers can generate and organize ideas dynamically. Creately’s intelligent formatting helps in brainstorming sessions, making it easier to explore multiple topics or delve deeply into specific concepts.

- Centralized Data Management: Creately enables the importation of data from multiple sources, which can be integrated into the visual research framework. This centralization aids in maintaining a cohesive and comprehensive overview of all research elements, ensuring that no critical information is overlooked.

- Communication and Collaboration: The platform supports real-time collaboration, allowing teams to work together seamlessly, regardless of their physical location. This feature is crucial for research teams spread across different geographies, facilitating effective communication and iterative feedback throughout the research process.

Moreover, the ability t Explore Conceptual Framework Examples directly within Creately inspires researchers by providing practical templates and examples that can be customized to suit specific research needs. This not only saves time but also enhances the quality of the conceptual framework developed.

In conclusion, Creately’s tools for creating and managing conceptual frameworks are indispensable for researchers aiming to achieve clear, structured, and impactful research outcomes.

Join over thousands of organizations that use Creately to brainstorm, plan, analyze, and execute their projects successfully.

More Related Articles

Chiraag George is a communication specialist here at Creately. He is a marketing junkie that is fascinated by how brands occupy consumer mind space. A lover of all things tech, he writes a lot about the intersection of technology, branding and culture at large.

The Ultimate Guide to Qualitative Research - Part 1: The Basics

- Introduction and overview

- What is qualitative research?

- What is qualitative data?

- Examples of qualitative data

- Qualitative vs. quantitative research

- Mixed methods

- Qualitative research preparation

- Theoretical perspective

- Theoretical framework

- Literature reviews

- Research question

- Introduction

Understanding conceptual frameworks

Selecting and developing your framework, variables in a conceptual framework.

- Conceptual vs. theoretical framework

- Data collection

- Qualitative research methods

- Focus groups

- Observational research

- Case studies

- Ethnographical research

- Ethical considerations

- Confidentiality and privacy

- Power dynamics

- Reflexivity

Conceptual framework: Definition and theory

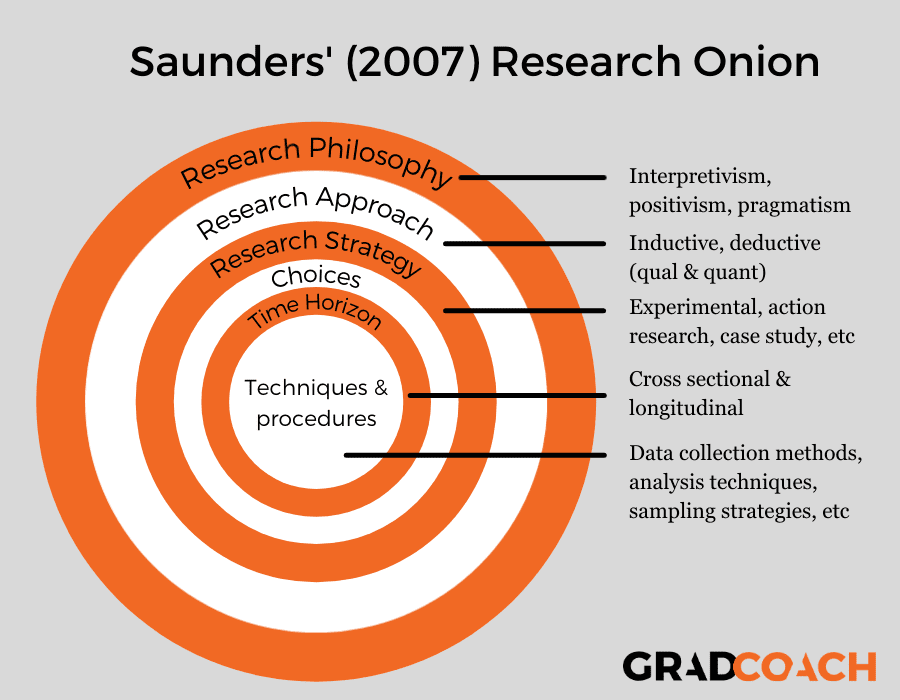

Theoretical and conceptual frameworks ultimately go hand in hand, but while there is significant overlap with theoretical perspectives and theoretical frameworks, understanding the essential differences is important when designing your research project.

Let's explore the idea of a conceptual framework, provide a few common examples, and discuss how to choose a framework for your study. Keep in mind that a conceptual framework will differ from a theoretical framework and that we will explore these differences in the next section.

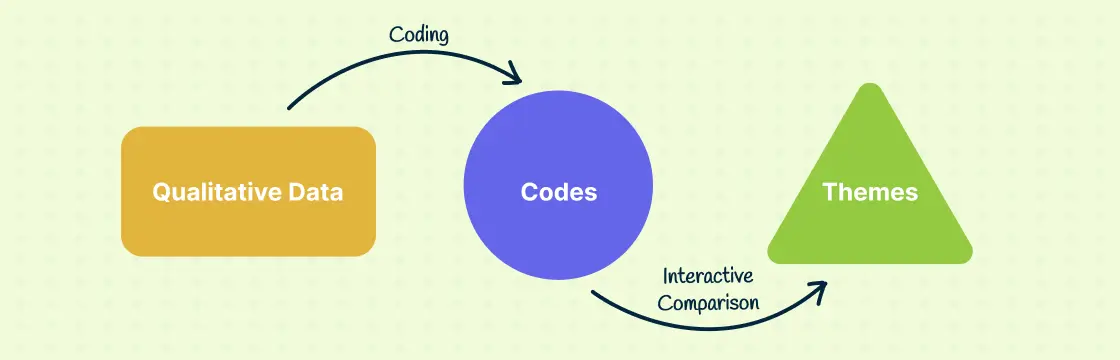

In this section, we'll delve into the intricacies of conceptual frameworks and their role in qualitative research . They are essentially the scaffolding on which you hang your research questions and analysis . They define the concepts that you'll study and articulate the relationships among them.

Developing conceptual frameworks in research

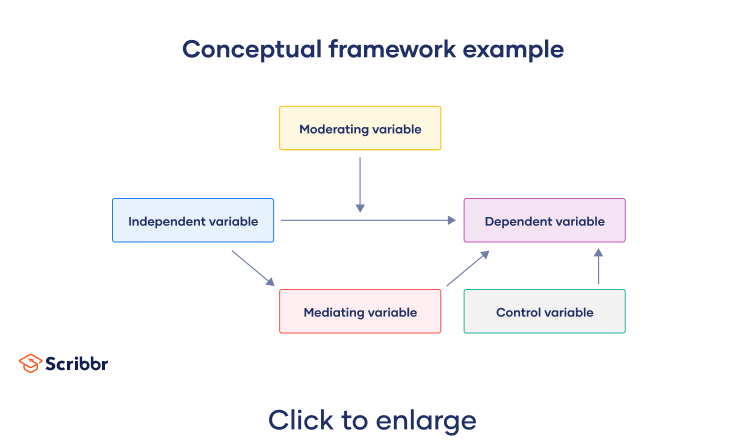

At the most basic level, a conceptual framework is a visual or written product that explains, either graphically or in narrative form, the main things to be studied, the key factors, variables, or constructs, and any presumed relationships among them. It acts as a road map guiding the course of your research, directing what will be studied, and helping to organize and analyze the data.

The purpose of a conceptual framework

A conceptual framework serves multiple functions in a research project. It helps in clarifying the research problem and purpose, assists in refining the research questions, and guides the data collection and analysis process. It's the tool that ties all aspects of the study together, offering a coherent perspective for the researcher and readers to understand the research more holistically.

Relation between theoretical perspectives and conceptual frameworks

Theoretical perspectives offer overarching philosophies and assumptions that guide the research process, while conceptual frameworks are the specific devices that are derived from these perspectives to operationalize the study. If a theoretical perspective is the broad philosophical underpinning, a conceptual framework is a pragmatic approach that puts that philosophy into practice in the context of the study.

For instance, if you're working from a feminist theoretical perspective, your conceptual framework might involve specific constructs like gender roles, power dynamics , and societal norms, as well as the relationships between these constructs. The conceptual framework would be the lens through which you examine and interpret your data, guided by your theoretical perspective.

Critical theory

Critical theory is a theoretical perspective that seeks to confront social, historical, and ideological forces and structures that produce and constrain social problems. The corresponding conceptual framework might focus on constructs like power relations, historical context, and societal structures. For instance, a study on income inequality might have a conceptual framework involving constructs of socioeconomic status, institutional policies, and the distribution of resources.

Feminist theory

Feminist theory emphasizes the societal roles of gender and power relationships. A conceptual framework derived from this theory might involve constructs like gender roles, power dynamics, and societal norms. In a study about gender representation in media, a feminist conceptual framework could involve constructs such as stereotyping, representation, and societal expectations of gender.

Design your study with ATLAS.ti

Data analysis starts with a solid study design. Make it happen with ATLAS.ti, starting with a free trial.

Choosing and developing your conceptual framework is a pivotal process in your research design. This framework will help guide your study, inform your methodology , and shape your analysis .

Factors to consider when choosing a framework

Your conceptual framework should be derived from and align with your chosen theoretical perspective , but there are other considerations as well. It should resonate with your research question , problem, or purpose and be applicable to the specific context or population you are studying. You should also consider the feasibility of operationalizing the constructs in your framework.

When selecting a conceptual framework, consider the following questions:

1. How does this framework relate to my research topic? 2. Can I use this framework to effectively address my research question(s)? 3. Does this framework resonate with the population and context I'm studying? 4. Can the constructs in this framework be feasibly operationalized in my study?

Steps in developing a conceptual framework

Developing your conceptual framework involves a few key steps:

1. Identify key constructs: Based on your theoretical perspective and research question(s) , what are the main constructs or variables that you need to explore in your study? 2. Clarify relationships among constructs: How do these constructs relate to each other? Are there presumed causal relationships, correlations, or other types of associations? 3. Define each construct: Clearly define what each construct means in the context of your study. This might also involve operationalizing each construct or defining the indicators you will use to measure or identify each construct. 4. Create a visual representation : It is often extremely helpful to create a visual representation of your conceptual framework to illustrate the constructs and their relationships. Map out the relationships among constructs to develop a holistic understanding of what you want to study.

Remember, your conceptual framework is not set in stone. You can start creating your conceptual framework based on your literature review and your own critical reflections. As you proceed with your study, you might need to refine or adapt your conceptual framework based on what you're learning from your data. Developing a robust framework is an iterative process that requires critical thinking, creativity, and flexibility.

A strong conceptual framework includes variables that refer to the constructs or characteristics that are being studied. They are the building blocks of your research study. It might be helpful to think about how the variables in your conceptual framework could be categorized as independent and dependent variables, which respectively influence and are influenced within the research study.

Independent variables and dependent variables

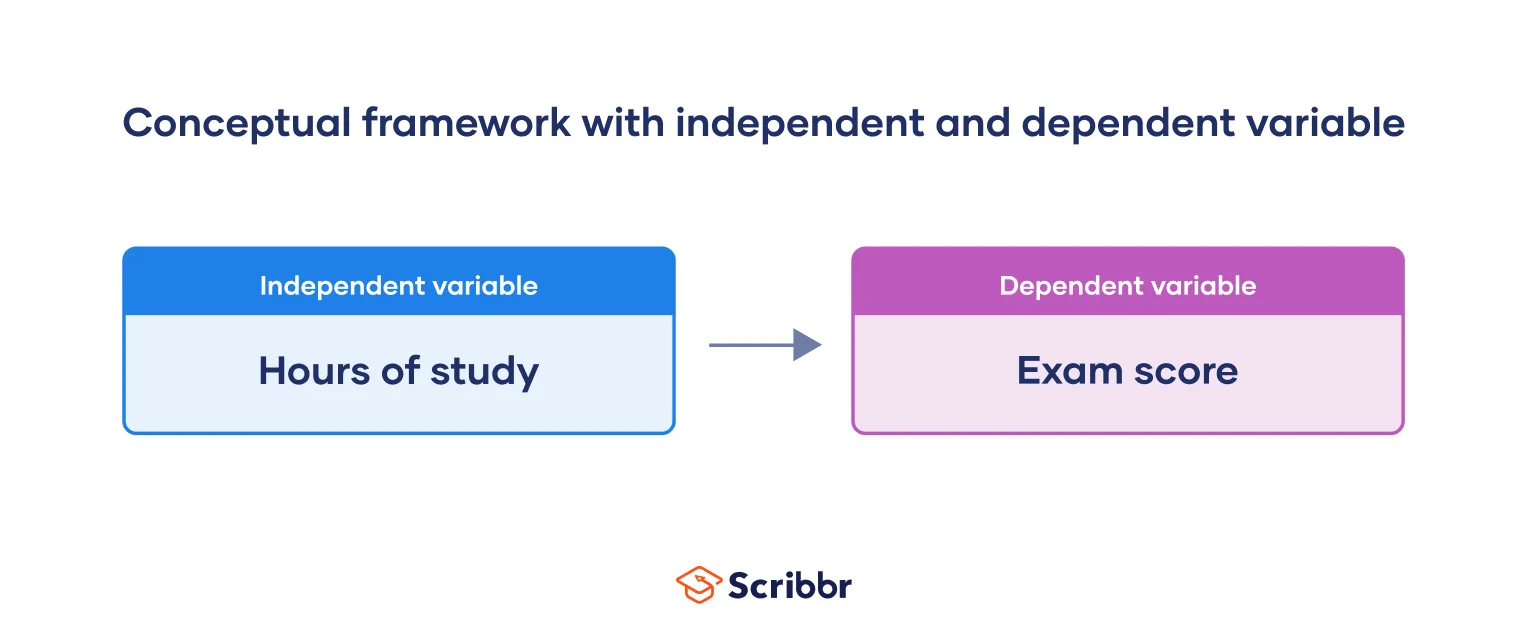

An independent variable is the characteristic or condition that is manipulated or selected by the researcher to determine its effect on the dependent variable. For example, in a study exploring the impact of classroom size on student engagement, classroom size would be the independent variable.

The dependent variable is the main outcome that the researcher is interested in studying or explaining. In the example given above, student engagement would be the dependent variable, as it's the outcome being observed for any changes in response to the independent variable (classroom size). In essence, defining these variables can help you identify the cause-and-effect relationships in your study. While it might be difficult to know beforehand exactly which variables will be important and how they relate to one another, this is a helpful thought exercise to flesh out potential relationships among variables you may want to study.

Relationships among variables

Within a conceptual framework, the dependent and independent variables are listed in addition to their proposed relationships to each other. The ways in which these variables influence one another form the crux of the propositions or assumptions that guide your research.

In a conceptual framework based on the theoretical perspective of constructivism, for instance, the independent variable might be a teaching method (as constructivists would argue that methods of instruction can shape learning), and the dependent variable could be the depth of student understanding. The proposed relationship between these variables might be that student-centered teaching methods lead to a deeper understanding, which would guide the data collection and analysis such that this proposition could be explored.

However, it is important to note that the terminology of independent and dependent variables is more typical of quantitative research , in which independent and dependent variables are operationalized in hypotheses that will be tested based on pre-established theory. In qualitative research , the relationships between variables are more fluid and open-ended because the focus is often more on understanding the phenomenon as a whole and building a contextualized understanding of the research problem. This can involve including new or unexpected variables and interrelationships that emerge during the study, thus extending previous theory or understanding that didn’t initially predict these relationships.

Thus, in your conceptual framework, rather than solely focusing on identifying independent and dependent variables, consider how various factors interact and influence one another within the context of your study. Your conceptual framework should provide a holistic picture of the complexity of the phenomenon you are studying.

Ready to jumpstart your research with ATLAS.ti?

Conceptualize your research project with our intuitive data analysis interface. Download a free trial today.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- What Is a Conceptual Framework? | Tips & Examples

What Is a Conceptual Framework? | Tips & Examples

Published on 4 May 2022 by Bas Swaen and Tegan George. Revised on 18 March 2024.

A conceptual framework illustrates the expected relationship between your variables. It defines the relevant objectives for your research process and maps out how they come together to draw coherent conclusions.

Keep reading for a step-by-step guide to help you construct your own conceptual framework.

Table of contents

Developing a conceptual framework in research, step 1: choose your research question, step 2: select your independent and dependent variables, step 3: visualise your cause-and-effect relationship, step 4: identify other influencing variables, frequently asked questions about conceptual models.

A conceptual framework is a representation of the relationship you expect to see between your variables, or the characteristics or properties that you want to study.

Conceptual frameworks can be written or visual and are generally developed based on a literature review of existing studies about your topic.

Your research question guides your work by determining exactly what you want to find out, giving your research process a clear focus.

However, before you start collecting your data, consider constructing a conceptual framework. This will help you map out which variables you will measure and how you expect them to relate to one another.

In order to move forward with your research question and test a cause-and-effect relationship, you must first identify at least two key variables: your independent and dependent variables .

- The expected cause, ‘hours of study’, is the independent variable (the predictor, or explanatory variable)

- The expected effect, ‘exam score’, is the dependent variable (the response, or outcome variable).

Note that causal relationships often involve several independent variables that affect the dependent variable. For the purpose of this example, we’ll work with just one independent variable (‘hours of study’).

Now that you’ve figured out your research question and variables, the first step in designing your conceptual framework is visualising your expected cause-and-effect relationship.

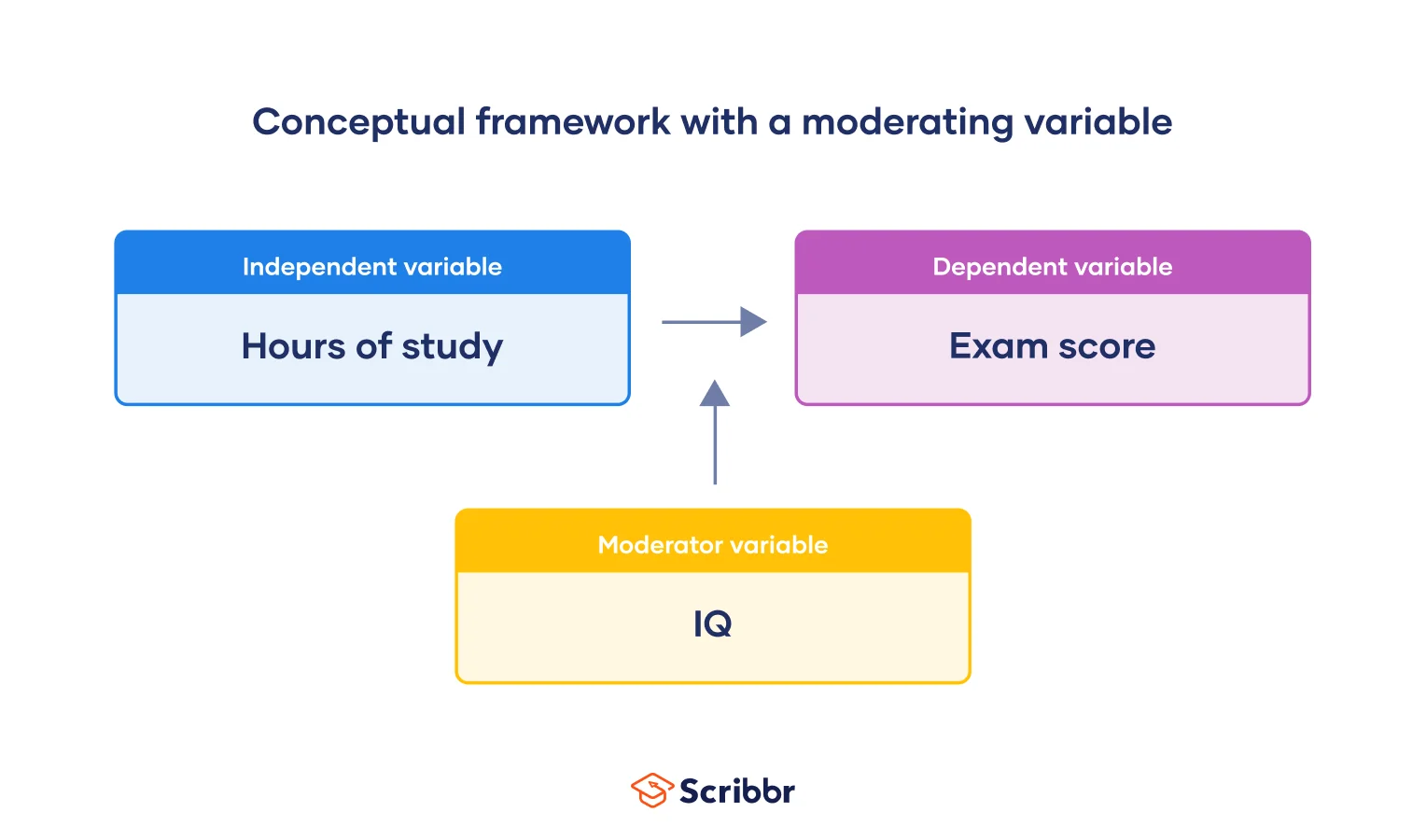

It’s crucial to identify other variables that can influence the relationship between your independent and dependent variables early in your research process.

Some common variables to include are moderating, mediating, and control variables.

Moderating variables

Moderating variable (or moderators) alter the effect that an independent variable has on a dependent variable. In other words, moderators change the ‘effect’ component of the cause-and-effect relationship.

Let’s add the moderator ‘IQ’. Here, a student’s IQ level can change the effect that the variable ‘hours of study’ has on the exam score. The higher the IQ, the fewer hours of study are needed to do well on the exam.

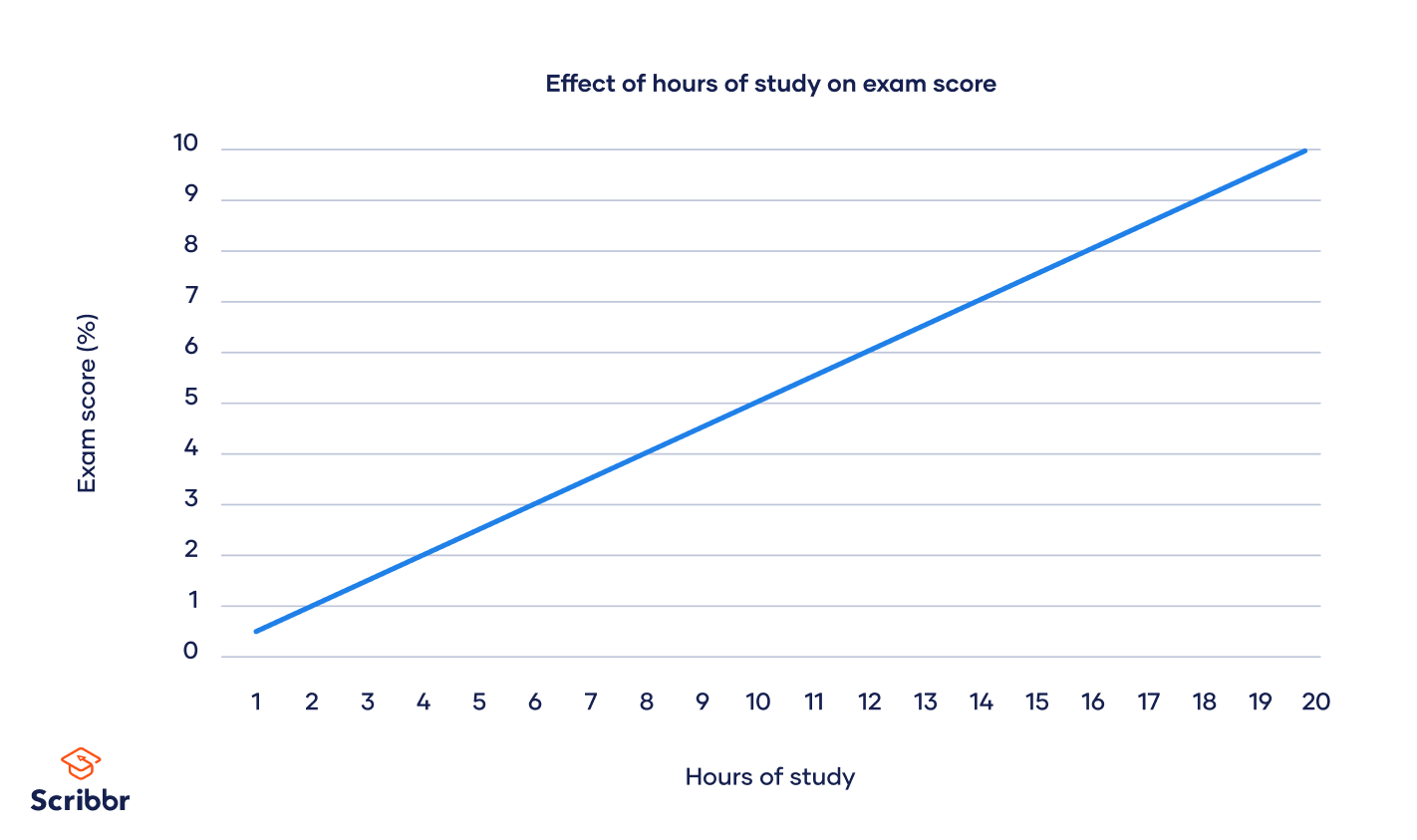

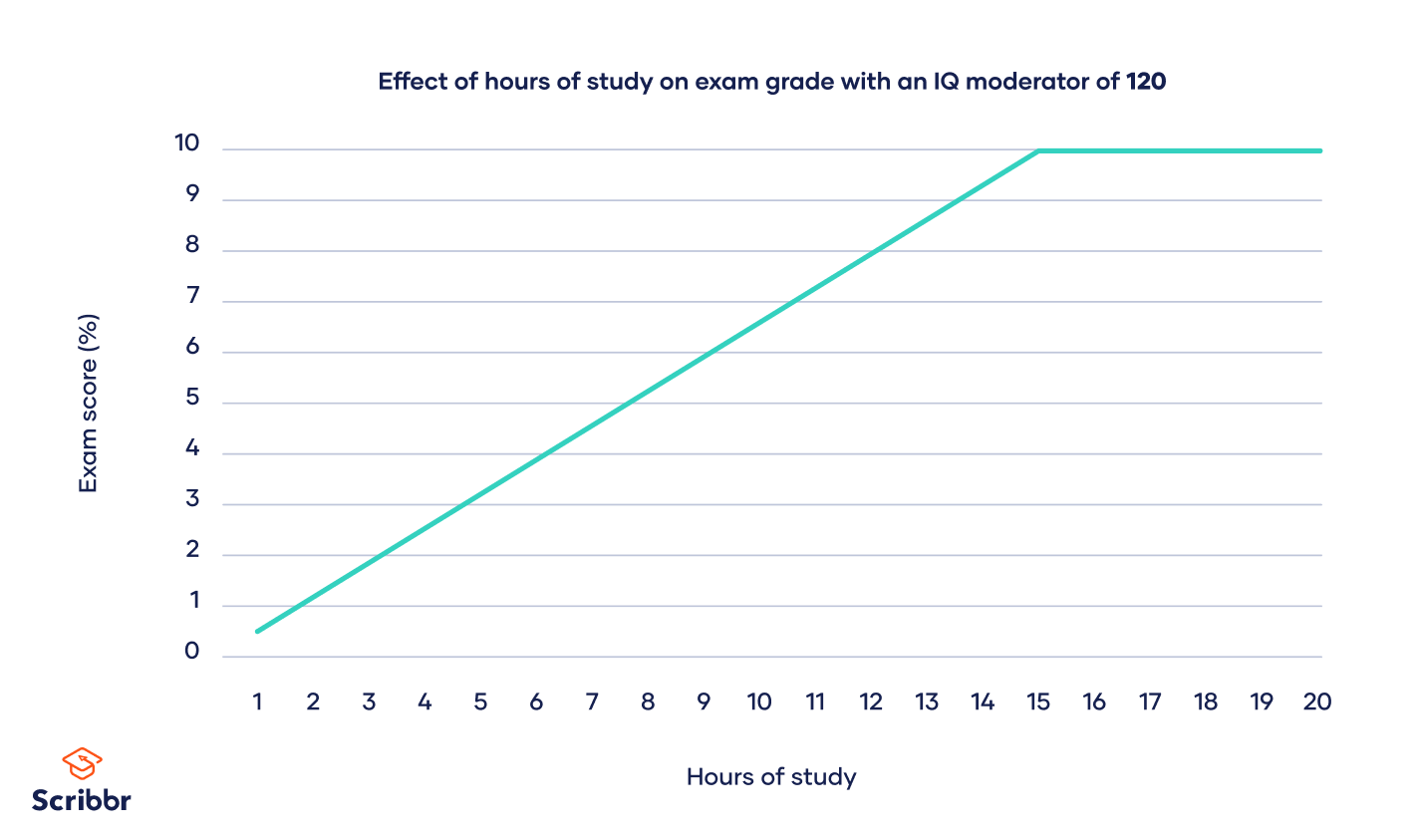

Let’s take a look at how this might work. The graph below shows how the number of hours spent studying affects exam score. As expected, the more hours you study, the better your results. Here, a student who studies for 20 hours will get a perfect score.

But the graph looks different when we add our ‘IQ’ moderator of 120. A student with this IQ will achieve a perfect score after just 15 hours of study.

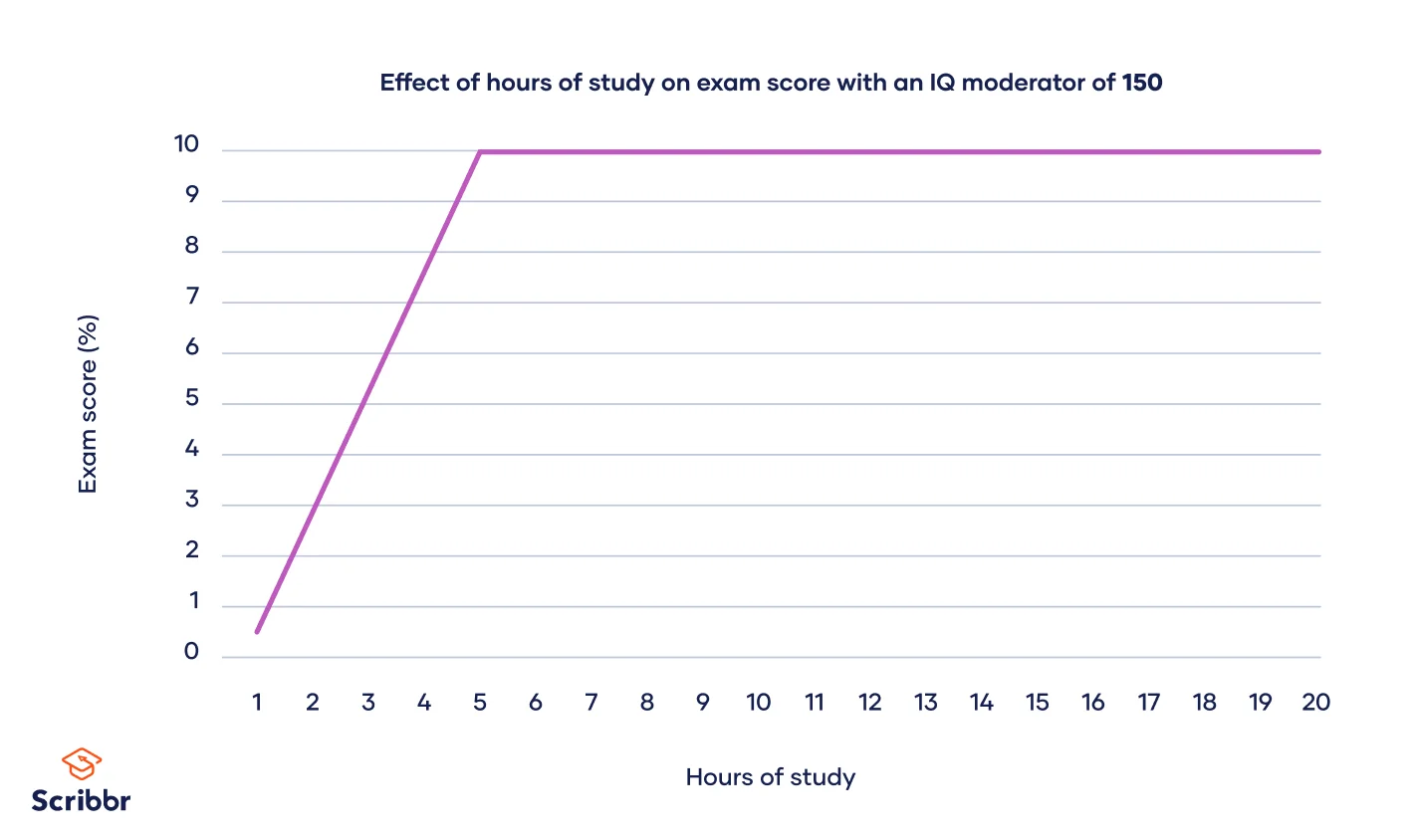

Below, the value of the ‘IQ’ moderator has been increased to 150. A student with this IQ will only need to invest five hours of study in order to get a perfect score.

Here, we see that a moderating variable does indeed change the cause-and-effect relationship between two variables.

Mediating variables

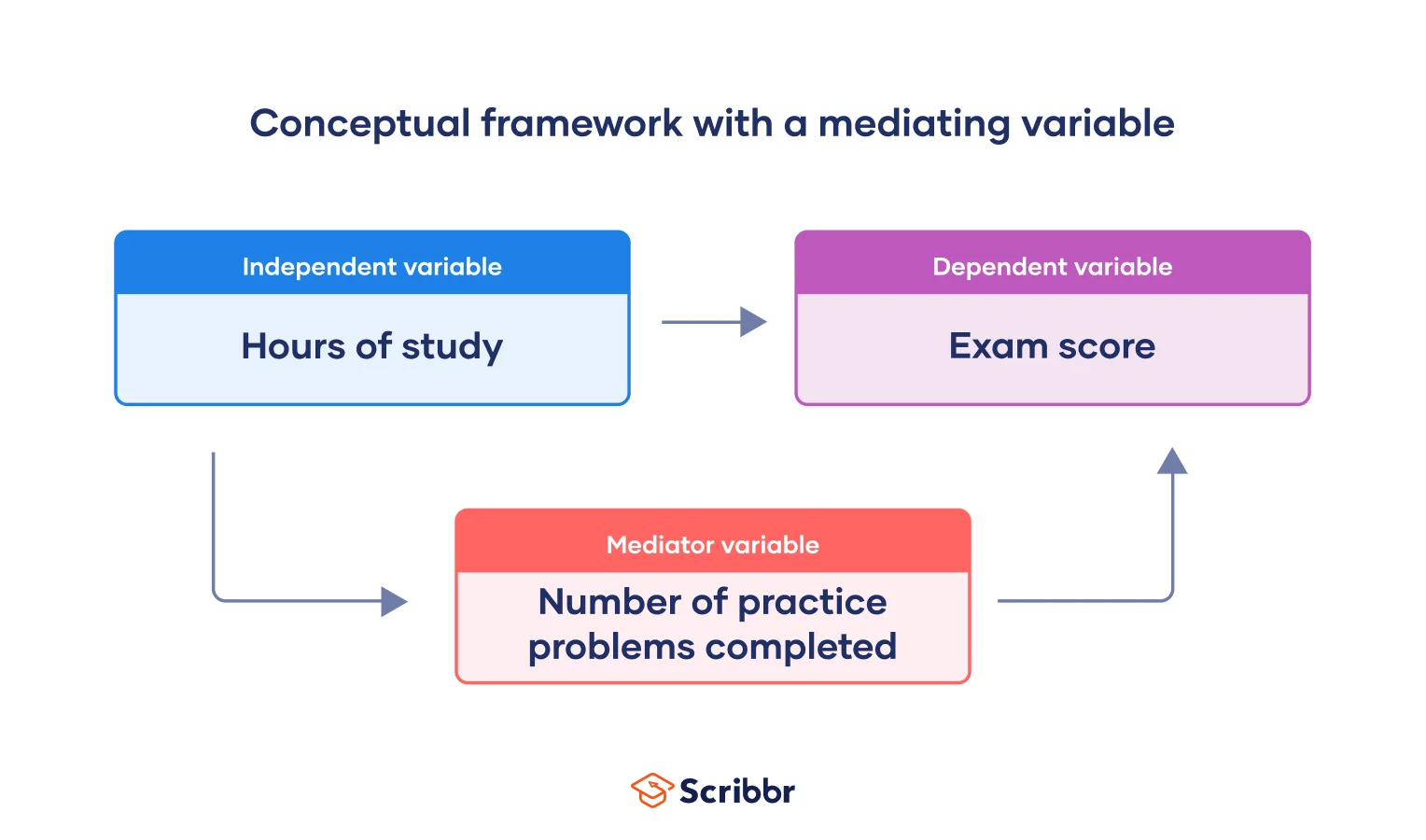

Now we’ll expand the framework by adding a mediating variable . Mediating variables link the independent and dependent variables, allowing the relationship between them to be better explained.

Here’s how the conceptual framework might look if a mediator variable were involved:

In this case, the mediator helps explain why studying more hours leads to a higher exam score. The more hours a student studies, the more practice problems they will complete; the more practice problems completed, the higher the student’s exam score will be.

Moderator vs mediator

It’s important not to confuse moderating and mediating variables. To remember the difference, you can think of them in relation to the independent variable:

- A moderating variable is not affected by the independent variable, even though it affects the dependent variable. For example, no matter how many hours you study (the independent variable), your IQ will not get higher.

- A mediating variable is affected by the independent variable. In turn, it also affects the dependent variable. Therefore, it links the two variables and helps explain the relationship between them.

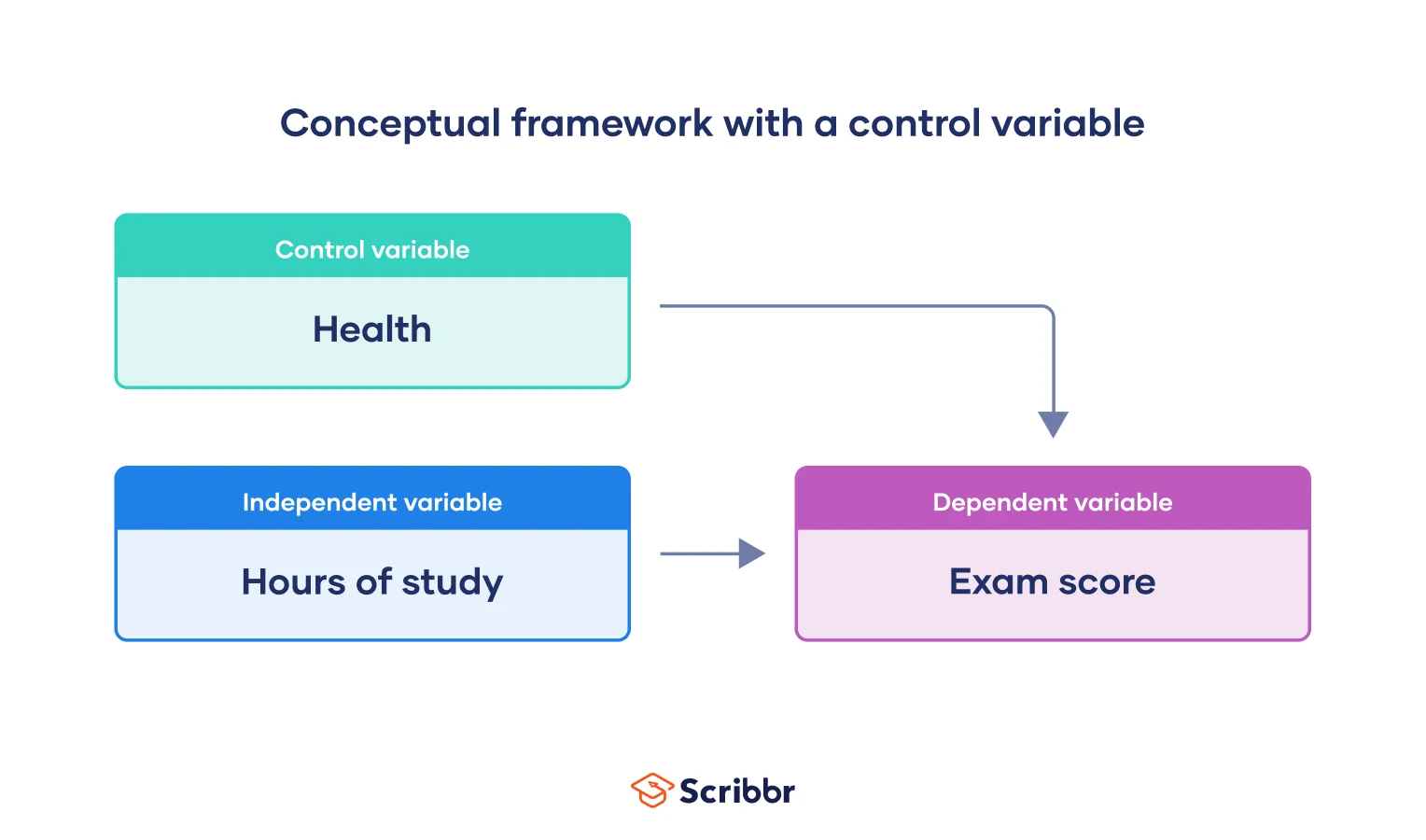

Control variables

Lastly, control variables must also be taken into account. These are variables that are held constant so that they don’t interfere with the results. Even though you aren’t interested in measuring them for your study, it’s crucial to be aware of as many of them as you can be.

A mediator variable explains the process through which two variables are related, while a moderator variable affects the strength and direction of that relationship.

No. The value of a dependent variable depends on an independent variable, so a variable cannot be both independent and dependent at the same time. It must be either the cause or the effect, not both.

Yes, but including more than one of either type requires multiple research questions .

For example, if you are interested in the effect of a diet on health, you can use multiple measures of health: blood sugar, blood pressure, weight, pulse, and many more. Each of these is its own dependent variable with its own research question.

You could also choose to look at the effect of exercise levels as well as diet, or even the additional effect of the two combined. Each of these is a separate independent variable .

To ensure the internal validity of an experiment , you should only change one independent variable at a time.

A control variable is any variable that’s held constant in a research study. It’s not a variable of interest in the study, but it’s controlled because it could influence the outcomes.

A confounding variable , also called a confounder or confounding factor, is a third variable in a study examining a potential cause-and-effect relationship.

A confounding variable is related to both the supposed cause and the supposed effect of the study. It can be difficult to separate the true effect of the independent variable from the effect of the confounding variable.

In your research design , it’s important to identify potential confounding variables and plan how you will reduce their impact.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Swaen, B. & George, T. (2024, March 18). What Is a Conceptual Framework? | Tips & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 3 June 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/conceptual-frameworks/

Is this article helpful?

Other students also liked

Mediator vs moderator variables | differences & examples, independent vs dependent variables | definition & examples, what are control variables | definition & examples.

What is a Conceptual Framework?

A conceptual framework sets forth the standards to define a research question and find appropriate, meaningful answers for the same. It connects the theories, assumptions, beliefs, and concepts behind your research and presents them in a pictorial, graphical, or narrative format.

Updated on August 28, 2023

What are frameworks in research?

Both theoretical and conceptual frameworks have a significant role in research. Frameworks are essential to bridge the gaps in research. They aid in clearly setting the goals, priorities, relationship between variables. Frameworks in research particularly help in chalking clear process details.

Theoretical frameworks largely work at the time when a theoretical roadmap has been laid about a certain topic and the research being undertaken by the researcher, carefully analyzes it, and works on similar lines to attain successful results.

It varies from a conceptual framework in terms of the preliminary work required to construct it. Though a conceptual framework is part of the theoretical framework in a larger sense, yet there are variations between them.

The following sections delve deeper into the characteristics of conceptual frameworks. This article will provide insight into constructing a concise, complete, and research-friendly conceptual framework for your project.

Definition of a conceptual framework

True research begins with setting empirical goals. Goals aid in presenting successful answers to the research questions at hand. It delineates a process wherein different aspects of the research are reflected upon, and coherence is established among them.

A conceptual framework is an underrated methodological approach that should be paid attention to before embarking on a research journey in any field, be it science, finance, history, psychology, etc.

A conceptual framework sets forth the standards to define a research question and find appropriate, meaningful answers for the same. It connects the theories, assumptions, beliefs, and concepts behind your research and presents them in a pictorial, graphical, or narrative format. Your conceptual framework establishes a link between the dependent and independent variables, factors, and other ideologies affecting the structure of your research.

A critical facet a conceptual framework unveils is the relationship the researchers have with their research. It closely highlights the factors that play an instrumental role in decision-making, variable selection, data collection, assessment of results, and formulation of new theories.

Consequently, if you, the researcher, are at the forefront of your research battlefield, your conceptual framework is the most powerful arsenal in your pocket.

What should be included in a conceptual framework?

A conceptual framework includes the key process parameters, defining variables, and cause-and-effect relationships. To add to this, the primary focus while developing a conceptual framework should remain on the quality of questions being raised and addressed through the framework. This will not only ease the process of initiation, but also enable you to draw meaningful conclusions from the same.

A practical and advantageous approach involves selecting models and analyzing literature that is unconventional and not directly related to the topic. This helps the researcher design an illustrative framework that is multidisciplinary and simultaneously looks at a diverse range of phenomena. It also emboldens the roots of exploratory research.

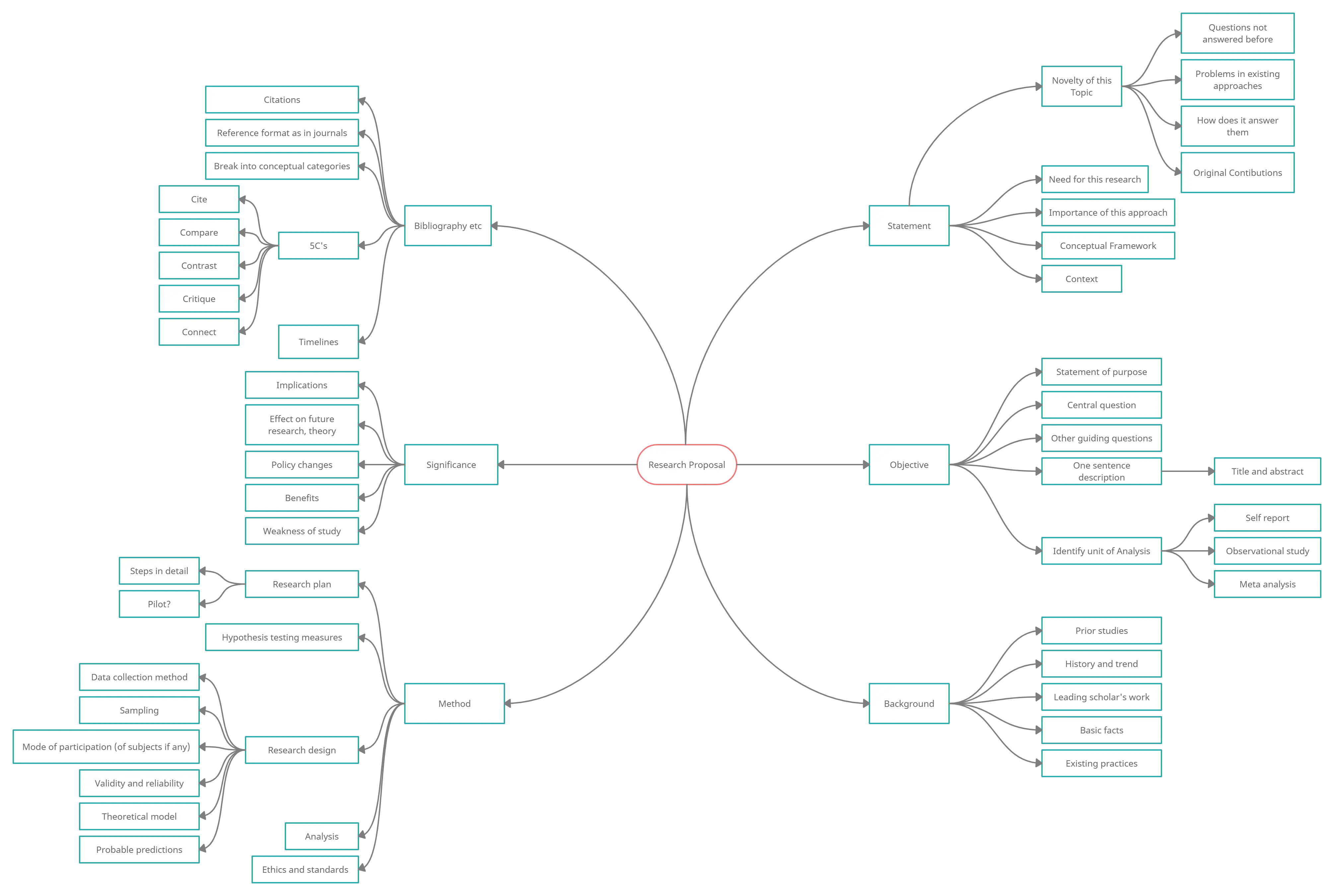

Fig. 1: Components of a conceptual framework

How to make a conceptual framework

The successful design of a conceptual framework includes:

- Selecting the appropriate research questions

- Defining the process variables (dependent, independent, and others)

- Determining the cause-and-effect relationships

This analytical tool begins with defining the most suitable set of questions that the research wishes to answer upon its conclusion. Following this, the different variety of variables is categorized. Lastly, the collected data is subjected to rigorous data analysis. Final results are compiled to establish links between the variables.

The variables drawn inside frames impact the overall quality of the research. If the framework involves arrows, it suggests correlational linkages among the variables. Lines, on the other hand, suggest that no significant correlation exists among them. Henceforth, the utilization of lines and arrows should be done taking into cognizance the meaning they both imply.

Example of a conceptual framework

To provide an idea about a conceptual framework, let’s examine the example of drug development research.

Say a new drug moiety A has to be launched in the market. For that, the baseline research begins with selecting the appropriate drug molecule. This is important because it:

- Provides the data for molecular docking studies to identify suitable target proteins

- Performs in vitro (a process taking place outside a living organism) and in vivo (a process taking place inside a living organism) analyzes

This assists in the screening of the molecules and a final selection leading to the most suitable target molecule. In this case, the choice of the drug molecule is an independent variable whereas, all the others, targets from molecular docking studies, and results from in vitro and in vivo analyses are dependent variables.

The outcomes revealed by the studies might be coherent or incoherent with the literature. In any case, an accurately designed conceptual framework will efficiently establish the cause-and-effect relationship and explain both perspectives satisfactorily.

If A has been chosen to be launched in the market, the conceptual framework will point towards the factors that have led to its selection. If A does not make it to the market, the key elements which did not work in its favor can be pinpointed by an accurate analysis of the conceptual framework.

Fig. 2: Concise example of a conceptual framework

Important takeaways

While conceptual frameworks are a great way of designing the research protocol, they might consist of some unforeseen loopholes. A review of the literature can sometimes provide a false impression of the collection of work done worldwide while in actuality, there might be research that is being undertaken on the same topic but is still under publication or review. Strong conceptual frameworks, therefore, are designed when all these aspects are taken into consideration and the researchers indulge in discussions with others working on similar grounds of research.

Conceptual frameworks may also sometimes lead to collecting and reviewing data that is not so relevant to the current research topic. The researchers must always be on the lookout for studies that are highly relevant to their topic of work and will be of impact if taken into consideration.

Another common practice associated with conceptual frameworks is their classification as merely descriptive qualitative tools and not actually a concrete build-up of ideas and critically analyzed literature and data which it is, in reality. Ideal conceptual frameworks always bring out their own set of new ideas after analysis of literature rather than simply depending on facts being already reported by other research groups.

So, the next time you set out to construct your conceptual framework or improvise on your previous one, be wary that concepts for your research are ideas that need to be worked upon. They are not simply a collection of literature from the previous research.

Final thoughts

Research is witnessing a boom in the methodical approaches being applied to it nowadays. In contrast to conventional research, researchers today are always looking for better techniques and methods to improve the quality of their research.

We strongly believe in the ideals of research that are not merely academic, but all-inclusive. We strongly encourage all our readers and researchers to do work that impacts society. Designing strong conceptual frameworks is an integral part of the process. It gives headway for systematic, empirical, and fruitful research.

Vridhi Sachdeva, MPharm

See our "Privacy Policy"

Get an overall assessment of the main focus of your study from AJE

Our Presubmission Review service will provide recommendations on the structure, organization, and the overall presentation of your research manuscript.

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Theoretical Framework

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

Theories are formulated to explain, predict, and understand phenomena and, in many cases, to challenge and extend existing knowledge within the limits of critical bounded assumptions or predictions of behavior. The theoretical framework is the structure that can hold or support a theory of a research study. The theoretical framework encompasses not just the theory, but the narrative explanation about how the researcher engages in using the theory and its underlying assumptions to investigate the research problem. It is the structure of your paper that summarizes concepts, ideas, and theories derived from prior research studies and which was synthesized in order to form a conceptual basis for your analysis and interpretation of meaning found within your research.

Abend, Gabriel. "The Meaning of Theory." Sociological Theory 26 (June 2008): 173–199; Kivunja, Charles. "Distinguishing between Theory, Theoretical Framework, and Conceptual Framework: A Systematic Review of Lessons from the Field." International Journal of Higher Education 7 (December 2018): 44-53; Swanson, Richard A. Theory Building in Applied Disciplines . San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers 2013; Varpio, Lara, Elise Paradis, Sebastian Uijtdehaage, and Meredith Young. "The Distinctions between Theory, Theoretical Framework, and Conceptual Framework." Academic Medicine 95 (July 2020): 989-994.

Importance of Theory and a Theoretical Framework

Theories can be unfamiliar to the beginning researcher because they are rarely applied in high school social studies curriculum and, as a result, can come across as unfamiliar and imprecise when first introduced as part of a writing assignment. However, in their most simplified form, a theory is simply a set of assumptions or predictions about something you think will happen based on existing evidence and that can be tested to see if those outcomes turn out to be true. Of course, it is slightly more deliberate than that, therefore, summarized from Kivunja (2018, p. 46), here are the essential characteristics of a theory.

- It is logical and coherent

- It has clear definitions of terms or variables, and has boundary conditions [i.e., it is not an open-ended statement]

- It has a domain where it applies

- It has clearly described relationships among variables

- It describes, explains, and makes specific predictions

- It comprises of concepts, themes, principles, and constructs

- It must have been based on empirical data [i.e., it is not a guess]

- It must have made claims that are subject to testing, been tested and verified

- It must be clear and concise

- Its assertions or predictions must be different and better than those in existing theories

- Its predictions must be general enough to be applicable to and understood within multiple contexts

- Its assertions or predictions are relevant, and if applied as predicted, will result in the predicted outcome

- The assertions and predictions are not immutable, but subject to revision and improvement as researchers use the theory to make sense of phenomena

- Its concepts and principles explain what is going on and why

- Its concepts and principles are substantive enough to enable us to predict a future

Given these characteristics, a theory can best be understood as the foundation from which you investigate assumptions or predictions derived from previous studies about the research problem, but in a way that leads to new knowledge and understanding as well as, in some cases, discovering how to improve the relevance of the theory itself or to argue that the theory is outdated and a new theory needs to be formulated based on new evidence.

A theoretical framework consists of concepts and, together with their definitions and reference to relevant scholarly literature, existing theory that is used for your particular study. The theoretical framework must demonstrate an understanding of theories and concepts that are relevant to the topic of your research paper and that relate to the broader areas of knowledge being considered.

The theoretical framework is most often not something readily found within the literature . You must review course readings and pertinent research studies for theories and analytic models that are relevant to the research problem you are investigating. The selection of a theory should depend on its appropriateness, ease of application, and explanatory power.

The theoretical framework strengthens the study in the following ways :

- An explicit statement of theoretical assumptions permits the reader to evaluate them critically.

- The theoretical framework connects the researcher to existing knowledge. Guided by a relevant theory, you are given a basis for your hypotheses and choice of research methods.

- Articulating the theoretical assumptions of a research study forces you to address questions of why and how. It permits you to intellectually transition from simply describing a phenomenon you have observed to generalizing about various aspects of that phenomenon.

- Having a theory helps you identify the limits to those generalizations. A theoretical framework specifies which key variables influence a phenomenon of interest and highlights the need to examine how those key variables might differ and under what circumstances.

- The theoretical framework adds context around the theory itself based on how scholars had previously tested the theory in relation their overall research design [i.e., purpose of the study, methods of collecting data or information, methods of analysis, the time frame in which information is collected, study setting, and the methodological strategy used to conduct the research].

By virtue of its applicative nature, good theory in the social sciences is of value precisely because it fulfills one primary purpose: to explain the meaning, nature, and challenges associated with a phenomenon, often experienced but unexplained in the world in which we live, so that we may use that knowledge and understanding to act in more informed and effective ways.

The Conceptual Framework. College of Education. Alabama State University; Corvellec, Hervé, ed. What is Theory?: Answers from the Social and Cultural Sciences . Stockholm: Copenhagen Business School Press, 2013; Asher, Herbert B. Theory-Building and Data Analysis in the Social Sciences . Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 1984; Drafting an Argument. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Kivunja, Charles. "Distinguishing between Theory, Theoretical Framework, and Conceptual Framework: A Systematic Review of Lessons from the Field." International Journal of Higher Education 7 (2018): 44-53; Omodan, Bunmi Isaiah. "A Model for Selecting Theoretical Framework through Epistemology of Research Paradigms." African Journal of Inter/Multidisciplinary Studies 4 (2022): 275-285; Ravitch, Sharon M. and Matthew Riggan. Reason and Rigor: How Conceptual Frameworks Guide Research . Second edition. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2017; Trochim, William M.K. Philosophy of Research. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006; Jarvis, Peter. The Practitioner-Researcher. Developing Theory from Practice . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1999.

Strategies for Developing the Theoretical Framework

I. Developing the Framework

Here are some strategies to develop of an effective theoretical framework:

- Examine your thesis title and research problem . The research problem anchors your entire study and forms the basis from which you construct your theoretical framework.

- Brainstorm about what you consider to be the key variables in your research . Answer the question, "What factors contribute to the presumed effect?"

- Review related literature to find how scholars have addressed your research problem. Identify the assumptions from which the author(s) addressed the problem.

- List the constructs and variables that might be relevant to your study. Group these variables into independent and dependent categories.

- Review key social science theories that are introduced to you in your course readings and choose the theory that can best explain the relationships between the key variables in your study [note the Writing Tip on this page].

- Discuss the assumptions or propositions of this theory and point out their relevance to your research.

A theoretical framework is used to limit the scope of the relevant data by focusing on specific variables and defining the specific viewpoint [framework] that the researcher will take in analyzing and interpreting the data to be gathered. It also facilitates the understanding of concepts and variables according to given definitions and builds new knowledge by validating or challenging theoretical assumptions.

II. Purpose

Think of theories as the conceptual basis for understanding, analyzing, and designing ways to investigate relationships within social systems. To that end, the following roles served by a theory can help guide the development of your framework.

- Means by which new research data can be interpreted and coded for future use,

- Response to new problems that have no previously identified solutions strategy,

- Means for identifying and defining research problems,

- Means for prescribing or evaluating solutions to research problems,

- Ways of discerning certain facts among the accumulated knowledge that are important and which facts are not,

- Means of giving old data new interpretations and new meaning,

- Means by which to identify important new issues and prescribe the most critical research questions that need to be answered to maximize understanding of the issue,

- Means of providing members of a professional discipline with a common language and a frame of reference for defining the boundaries of their profession, and

- Means to guide and inform research so that it can, in turn, guide research efforts and improve professional practice.

Adapted from: Torraco, R. J. “Theory-Building Research Methods.” In Swanson R. A. and E. F. Holton III , editors. Human Resource Development Handbook: Linking Research and Practice . (San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler, 1997): pp. 114-137; Jacard, James and Jacob Jacoby. Theory Construction and Model-Building Skills: A Practical Guide for Social Scientists . New York: Guilford, 2010; Ravitch, Sharon M. and Matthew Riggan. Reason and Rigor: How Conceptual Frameworks Guide Research . Second edition. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2017; Sutton, Robert I. and Barry M. Staw. “What Theory is Not.” Administrative Science Quarterly 40 (September 1995): 371-384.

Structure and Writing Style

The theoretical framework may be rooted in a specific theory , in which case, your work is expected to test the validity of that existing theory in relation to specific events, issues, or phenomena. Many social science research papers fit into this rubric. For example, Peripheral Realism Theory, which categorizes perceived differences among nation-states as those that give orders, those that obey, and those that rebel, could be used as a means for understanding conflicted relationships among countries in Africa. A test of this theory could be the following: Does Peripheral Realism Theory help explain intra-state actions, such as, the disputed split between southern and northern Sudan that led to the creation of two nations?

However, you may not always be asked by your professor to test a specific theory in your paper, but to develop your own framework from which your analysis of the research problem is derived . Based upon the above example, it is perhaps easiest to understand the nature and function of a theoretical framework if it is viewed as an answer to two basic questions:

- What is the research problem/question? [e.g., "How should the individual and the state relate during periods of conflict?"]

- Why is your approach a feasible solution? [i.e., justify the application of your choice of a particular theory and explain why alternative constructs were rejected. I could choose instead to test Instrumentalist or Circumstantialists models developed among ethnic conflict theorists that rely upon socio-economic-political factors to explain individual-state relations and to apply this theoretical model to periods of war between nations].

The answers to these questions come from a thorough review of the literature and your course readings [summarized and analyzed in the next section of your paper] and the gaps in the research that emerge from the review process. With this in mind, a complete theoretical framework will likely not emerge until after you have completed a thorough review of the literature .

Just as a research problem in your paper requires contextualization and background information, a theory requires a framework for understanding its application to the topic being investigated. When writing and revising this part of your research paper, keep in mind the following:

- Clearly describe the framework, concepts, models, or specific theories that underpin your study . This includes noting who the key theorists are in the field who have conducted research on the problem you are investigating and, when necessary, the historical context that supports the formulation of that theory. This latter element is particularly important if the theory is relatively unknown or it is borrowed from another discipline.

- Position your theoretical framework within a broader context of related frameworks, concepts, models, or theories . As noted in the example above, there will likely be several concepts, theories, or models that can be used to help develop a framework for understanding the research problem. Therefore, note why the theory you've chosen is the appropriate one.

- The present tense is used when writing about theory. Although the past tense can be used to describe the history of a theory or the role of key theorists, the construction of your theoretical framework is happening now.

- You should make your theoretical assumptions as explicit as possible . Later, your discussion of methodology should be linked back to this theoretical framework.

- Don’t just take what the theory says as a given! Reality is never accurately represented in such a simplistic way; if you imply that it can be, you fundamentally distort a reader's ability to understand the findings that emerge. Given this, always note the limitations of the theoretical framework you've chosen [i.e., what parts of the research problem require further investigation because the theory inadequately explains a certain phenomena].

The Conceptual Framework. College of Education. Alabama State University; Conceptual Framework: What Do You Think is Going On? College of Engineering. University of Michigan; Drafting an Argument. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Lynham, Susan A. “The General Method of Theory-Building Research in Applied Disciplines.” Advances in Developing Human Resources 4 (August 2002): 221-241; Tavallaei, Mehdi and Mansor Abu Talib. "A General Perspective on the Role of Theory in Qualitative Research." Journal of International Social Research 3 (Spring 2010); Ravitch, Sharon M. and Matthew Riggan. Reason and Rigor: How Conceptual Frameworks Guide Research . Second edition. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2017; Reyes, Victoria. Demystifying the Journal Article. Inside Higher Education; Trochim, William M.K. Philosophy of Research. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006; Weick, Karl E. “The Work of Theorizing.” In Theorizing in Social Science: The Context of Discovery . Richard Swedberg, editor. (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2014), pp. 177-194.

Writing Tip

Borrowing Theoretical Constructs from Other Disciplines

An increasingly important trend in the social and behavioral sciences is to think about and attempt to understand research problems from an interdisciplinary perspective. One way to do this is to not rely exclusively on the theories developed within your particular discipline, but to think about how an issue might be informed by theories developed in other disciplines. For example, if you are a political science student studying the rhetorical strategies used by female incumbents in state legislature campaigns, theories about the use of language could be derived, not only from political science, but linguistics, communication studies, philosophy, psychology, and, in this particular case, feminist studies. Building theoretical frameworks based on the postulates and hypotheses developed in other disciplinary contexts can be both enlightening and an effective way to be more engaged in the research topic.

CohenMiller, A. S. and P. Elizabeth Pate. "A Model for Developing Interdisciplinary Research Theoretical Frameworks." The Qualitative Researcher 24 (2019): 1211-1226; Frodeman, Robert. The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity . New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Another Writing Tip

Don't Undertheorize!

Do not leave the theory hanging out there in the introduction never to be mentioned again. Undertheorizing weakens your paper. The theoretical framework you describe should guide your study throughout the paper. Be sure to always connect theory to the review of pertinent literature and to explain in the discussion part of your paper how the theoretical framework you chose supports analysis of the research problem or, if appropriate, how the theoretical framework was found to be inadequate in explaining the phenomenon you were investigating. In that case, don't be afraid to propose your own theory based on your findings.

Yet Another Writing Tip

What's a Theory? What's a Hypothesis?

The terms theory and hypothesis are often used interchangeably in newspapers and popular magazines and in non-academic settings. However, the difference between theory and hypothesis in scholarly research is important, particularly when using an experimental design. A theory is a well-established principle that has been developed to explain some aspect of the natural world. Theories arise from repeated observation and testing and incorporates facts, laws, predictions, and tested assumptions that are widely accepted [e.g., rational choice theory; grounded theory; critical race theory].

A hypothesis is a specific, testable prediction about what you expect to happen in your study. For example, an experiment designed to look at the relationship between study habits and test anxiety might have a hypothesis that states, "We predict that students with better study habits will suffer less test anxiety." Unless your study is exploratory in nature, your hypothesis should always explain what you expect to happen during the course of your research.

The key distinctions are:

- A theory predicts events in a broad, general context; a hypothesis makes a specific prediction about a specified set of circumstances.

- A theory has been extensively tested and is generally accepted among a set of scholars; a hypothesis is a speculative guess that has yet to be tested.

Cherry, Kendra. Introduction to Research Methods: Theory and Hypothesis. About.com Psychology; Gezae, Michael et al. Welcome Presentation on Hypothesis. Slideshare presentation.

Still Yet Another Writing Tip

Be Prepared to Challenge the Validity of an Existing Theory

Theories are meant to be tested and their underlying assumptions challenged; they are not rigid or intransigent, but are meant to set forth general principles for explaining phenomena or predicting outcomes. Given this, testing theoretical assumptions is an important way that knowledge in any discipline develops and grows. If you're asked to apply an existing theory to a research problem, the analysis will likely include the expectation by your professor that you should offer modifications to the theory based on your research findings.

Indications that theoretical assumptions may need to be modified can include the following:

- Your findings suggest that the theory does not explain or account for current conditions or circumstances or the passage of time,

- The study reveals a finding that is incompatible with what the theory attempts to explain or predict, or

- Your analysis reveals that the theory overly generalizes behaviors or actions without taking into consideration specific factors revealed from your analysis [e.g., factors related to culture, nationality, history, gender, ethnicity, age, geographic location, legal norms or customs , religion, social class, socioeconomic status, etc.].

Philipsen, Kristian. "Theory Building: Using Abductive Search Strategies." In Collaborative Research Design: Working with Business for Meaningful Findings . Per Vagn Freytag and Louise Young, editors. (Singapore: Springer Nature, 2018), pp. 45-71; Shepherd, Dean A. and Roy Suddaby. "Theory Building: A Review and Integration." Journal of Management 43 (2017): 59-86.

- << Previous: The Research Problem/Question

- Next: 5. The Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: May 30, 2024 9:38 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

- Privacy Policy

Home » Theoretical Framework – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Theoretical Framework – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Theoretical Framework

Definition:

Theoretical framework refers to a set of concepts, theories, ideas , and assumptions that serve as a foundation for understanding a particular phenomenon or problem. It provides a conceptual framework that helps researchers to design and conduct their research, as well as to analyze and interpret their findings.

In research, a theoretical framework explains the relationship between various variables, identifies gaps in existing knowledge, and guides the development of research questions, hypotheses, and methodologies. It also helps to contextualize the research within a broader theoretical perspective, and can be used to guide the interpretation of results and the formulation of recommendations.

Types of Theoretical Framework

Types of Types of Theoretical Framework are as follows:

Conceptual Framework

This type of framework defines the key concepts and relationships between them. It helps to provide a theoretical foundation for a study or research project .

Deductive Framework

This type of framework starts with a general theory or hypothesis and then uses data to test and refine it. It is often used in quantitative research .

Inductive Framework

This type of framework starts with data and then develops a theory or hypothesis based on the patterns and themes that emerge from the data. It is often used in qualitative research .

Empirical Framework

This type of framework focuses on the collection and analysis of empirical data, such as surveys or experiments. It is often used in scientific research .

Normative Framework

This type of framework defines a set of norms or values that guide behavior or decision-making. It is often used in ethics and social sciences.

Explanatory Framework

This type of framework seeks to explain the underlying mechanisms or causes of a particular phenomenon or behavior. It is often used in psychology and social sciences.

Components of Theoretical Framework

The components of a theoretical framework include:

- Concepts : The basic building blocks of a theoretical framework. Concepts are abstract ideas or generalizations that represent objects, events, or phenomena.

- Variables : These are measurable and observable aspects of a concept. In a research context, variables can be manipulated or measured to test hypotheses.

- Assumptions : These are beliefs or statements that are taken for granted and are not tested in a study. They provide a starting point for developing hypotheses.

- Propositions : These are statements that explain the relationships between concepts and variables in a theoretical framework.

- Hypotheses : These are testable predictions that are derived from the theoretical framework. Hypotheses are used to guide data collection and analysis.

- Constructs : These are abstract concepts that cannot be directly measured but are inferred from observable variables. Constructs provide a way to understand complex phenomena.

- Models : These are simplified representations of reality that are used to explain, predict, or control a phenomenon.

How to Write Theoretical Framework

A theoretical framework is an essential part of any research study or paper, as it helps to provide a theoretical basis for the research and guide the analysis and interpretation of the data. Here are some steps to help you write a theoretical framework:

- Identify the key concepts and variables : Start by identifying the main concepts and variables that your research is exploring. These could include things like motivation, behavior, attitudes, or any other relevant concepts.

- Review relevant literature: Conduct a thorough review of the existing literature in your field to identify key theories and ideas that relate to your research. This will help you to understand the existing knowledge and theories that are relevant to your research and provide a basis for your theoretical framework.

- Develop a conceptual framework : Based on your literature review, develop a conceptual framework that outlines the key concepts and their relationships. This framework should provide a clear and concise overview of the theoretical perspective that underpins your research.

- Identify hypotheses and research questions: Based on your conceptual framework, identify the hypotheses and research questions that you want to test or explore in your research.

- Test your theoretical framework: Once you have developed your theoretical framework, test it by applying it to your research data. This will help you to identify any gaps or weaknesses in your framework and refine it as necessary.

- Write up your theoretical framework: Finally, write up your theoretical framework in a clear and concise manner, using appropriate terminology and referencing the relevant literature to support your arguments.

Theoretical Framework Examples

Here are some examples of theoretical frameworks:

- Social Learning Theory : This framework, developed by Albert Bandura, suggests that people learn from their environment, including the behaviors of others, and that behavior is influenced by both external and internal factors.

- Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs : Abraham Maslow proposed that human needs are arranged in a hierarchy, with basic physiological needs at the bottom, followed by safety, love and belonging, esteem, and self-actualization at the top. This framework has been used in various fields, including psychology and education.

- Ecological Systems Theory : This framework, developed by Urie Bronfenbrenner, suggests that a person’s development is influenced by the interaction between the individual and the various environments in which they live, such as family, school, and community.

- Feminist Theory: This framework examines how gender and power intersect to influence social, cultural, and political issues. It emphasizes the importance of understanding and challenging systems of oppression.

- Cognitive Behavioral Theory: This framework suggests that our thoughts, beliefs, and attitudes influence our behavior, and that changing our thought patterns can lead to changes in behavior and emotional responses.

- Attachment Theory: This framework examines the ways in which early relationships with caregivers shape our later relationships and attachment styles.

- Critical Race Theory : This framework examines how race intersects with other forms of social stratification and oppression to perpetuate inequality and discrimination.

When to Have A Theoretical Framework

Following are some situations When to Have A Theoretical Framework:

- A theoretical framework should be developed when conducting research in any discipline, as it provides a foundation for understanding the research problem and guiding the research process.

- A theoretical framework is essential when conducting research on complex phenomena, as it helps to organize and structure the research questions, hypotheses, and findings.

- A theoretical framework should be developed when the research problem requires a deeper understanding of the underlying concepts and principles that govern the phenomenon being studied.

- A theoretical framework is particularly important when conducting research in social sciences, as it helps to explain the relationships between variables and provides a framework for testing hypotheses.

- A theoretical framework should be developed when conducting research in applied fields, such as engineering or medicine, as it helps to provide a theoretical basis for the development of new technologies or treatments.

- A theoretical framework should be developed when conducting research that seeks to address a specific gap in knowledge, as it helps to define the problem and identify potential solutions.

- A theoretical framework is also important when conducting research that involves the analysis of existing theories or concepts, as it helps to provide a framework for comparing and contrasting different theories and concepts.

- A theoretical framework should be developed when conducting research that seeks to make predictions or develop generalizations about a particular phenomenon, as it helps to provide a basis for evaluating the accuracy of these predictions or generalizations.

- Finally, a theoretical framework should be developed when conducting research that seeks to make a contribution to the field, as it helps to situate the research within the broader context of the discipline and identify its significance.

Purpose of Theoretical Framework

The purposes of a theoretical framework include:

- Providing a conceptual framework for the study: A theoretical framework helps researchers to define and clarify the concepts and variables of interest in their research. It enables researchers to develop a clear and concise definition of the problem, which in turn helps to guide the research process.

- Guiding the research design: A theoretical framework can guide the selection of research methods, data collection techniques, and data analysis procedures. By outlining the key concepts and assumptions underlying the research questions, the theoretical framework can help researchers to identify the most appropriate research design for their study.

- Supporting the interpretation of research findings: A theoretical framework provides a framework for interpreting the research findings by helping researchers to make connections between their findings and existing theory. It enables researchers to identify the implications of their findings for theory development and to assess the generalizability of their findings.

- Enhancing the credibility of the research: A well-developed theoretical framework can enhance the credibility of the research by providing a strong theoretical foundation for the study. It demonstrates that the research is based on a solid understanding of the relevant theory and that the research questions are grounded in a clear conceptual framework.

- Facilitating communication and collaboration: A theoretical framework provides a common language and conceptual framework for researchers, enabling them to communicate and collaborate more effectively. It helps to ensure that everyone involved in the research is working towards the same goals and is using the same concepts and definitions.

Characteristics of Theoretical Framework

Some of the characteristics of a theoretical framework include:

- Conceptual clarity: The concepts used in the theoretical framework should be clearly defined and understood by all stakeholders.

- Logical coherence : The framework should be internally consistent, with each concept and assumption logically connected to the others.

- Empirical relevance: The framework should be based on empirical evidence and research findings.

- Parsimony : The framework should be as simple as possible, without sacrificing its ability to explain the phenomenon in question.

- Flexibility : The framework should be adaptable to new findings and insights.

- Testability : The framework should be testable through research, with clear hypotheses that can be falsified or supported by data.

- Applicability : The framework should be useful for practical applications, such as designing interventions or policies.

Advantages of Theoretical Framework

Here are some of the advantages of having a theoretical framework:

- Provides a clear direction : A theoretical framework helps researchers to identify the key concepts and variables they need to study and the relationships between them. This provides a clear direction for the research and helps researchers to focus their efforts and resources.

- Increases the validity of the research: A theoretical framework helps to ensure that the research is based on sound theoretical principles and concepts. This increases the validity of the research by ensuring that it is grounded in established knowledge and is not based on arbitrary assumptions.

- Enables comparisons between studies : A theoretical framework provides a common language and set of concepts that researchers can use to compare and contrast their findings. This helps to build a cumulative body of knowledge and allows researchers to identify patterns and trends across different studies.

- Helps to generate hypotheses: A theoretical framework provides a basis for generating hypotheses about the relationships between different concepts and variables. This can help to guide the research process and identify areas that require further investigation.

- Facilitates communication: A theoretical framework provides a common language and set of concepts that researchers can use to communicate their findings to other researchers and to the wider community. This makes it easier for others to understand the research and its implications.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Verification – Process, Types and Examples

Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing...

Limitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Thesis Outline – Example, Template and Writing...

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Chapter Summary & Overview – Writing Guide...

Conceptual Research Framework

- First Online: 29 January 2023

Cite this chapter

- Philipp Sylla 3

Part of the book series: Schriftenreihe der HHL Leipzig Graduate School of Management ((SHL))

285 Accesses

To build a solid theoretical foundation for the following empirical analysis, a conceptual research framework will be developed within this chapter. First of all, the objectives and theoretical foundation of the research framework will be presented in section 4.1. In addition, the structure of the framework and its representation in this chapter will be explained.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

A conceptual research framework represents a first step toward the formation of theoretical insights (cp. Kirsch et al. (2007), pp. 22–23). Its main purpose is a precise delineation of the research problem which should prevent empirical data collection without a solid conceptual basis (cp. Kaufmann (2001), p. 147).

Cp. section 4.1.3 .

Cp. Wolf (2011), p. 37.

Cp. Wiesener (2014), p. 109.

Commonly, the statements are limited to assuming functional relationships without specifying these in more detail (cp. Kirsch (1973), p. 14).

Cp. Beckmann (2009), p. 81; Dietrich (2001), p. 22.

Cp. Vollhardt (2007), p. 68.

Cp. Wolf (2011), p. 202.

Cp. Pfohl and Zöllner (1997), pp. 307–312.

Cp. Reinking (2012), pp. 251–258.

Cp. Beckmann (2009), pp. 81–82; Eder (2016), pp. 38–40; Reinking (2012), pp. 248–249; Vollhardt (2007), p. 68.

Cp. Petersen (2012), p. 51; Miroschedji (2002), p. 122; Wolf (2011), pp. 38–39.

Cp. Wolf (2011), pp. 218–230.

Cp. Beckmann (2009), p. 83; Jensen (2004), p. 15; Vollhardt (2007), p. 71; Wolf (2011), p. 218.

Schoonhoven (1981), p. 350.

Cp. Jensen (2004), pp. 15–16; Beckmann (2009), p. 84.

Cp. Beckmann (2009), p. 84; Wolf (2011), p. 223.

Cp. section 1.3 .

Source: own representation.

In scientific research, the identification of dimensions is fundamental for conceptualization, i.e. the process for making fuzzy and imprecise notions more specific and precise (cp. Babbie (2016), pp. 123–132).

Cp. Wolf (2011), pp. 38–39.

This definition is based on a general definition of system use as “[…] the degree and manner in which staff and customers utilize the capabilities of an information system” (Petter et al. (2008), p. 239).

This is evident by the central role of system use in conceptual models of IS success (cp. DeLone and McLean (1992), p. 87; Gable et al. (2008), p. 382; Soh and Markus (1995), p. 37). In addition, many empirical studies indicate that system use is relevant for IS success (cp. Petter et al. (2008), pp. 251–252).

DeLone and McLean (2003), p. 16.

A business relationship is a sequence of market transactions between a buyer and seller that is not incidental (cp. Kleinaltenkamp et al. (2011), p. 22).

Cp. Kleineicken (2004), p. 105.

Cp. Richter and Nohr (2002), p. 110.

Cp. Bächle and Lehmann (2010), p. 70.

Cp. Büyüközkan (2004), p. 140.

Cp. Hartmann (2002b), pp. 167–171.

Cp. Jetu and Riedl (2012), pp. 462–463.

Besides the organizational level, system use can also be studied at the individual or group level. Research at more aggregate levels (e.g. the level of an industry or nation) is less common (cp. Burton-Jones and Gallivan (2007), p. 659).

While users in a voluntary use setting can choose whether an IS is used or not, users do not have such a choice and must use a prescribed system in a mandatory setting (cp. Bhattacherjee et al. (2018), pp. 395–396).