An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Find crime statistics

Federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies collect data about crime. Find crime statistics around the U.S. using the FBI’s Crime Data Explorer.

Use the Crime Data Explorer to find statistics about different types of crime nationally or in your state, county, or town.

LAST UPDATED: February 1, 2024

Have a question?

Ask a real person any government-related question for free. They will get you the answer or let you know where to find it.

New Data Shows Violent Crime Is Up… And Also Down.

Property crime and violence against young people are both up, recent federal data shows, but other crime trends are murkier..

T wo key crime reports released by the Justice Department this fall reveal a changing crime landscape, even when they diverge on year-over-year trends. Property crime rose in significant ways for the first time in years. Violent crime against young people doubled. As usual, most crimes go unreported. And as a major election season looms in 2024, the deviation between the reports on recent trends in violent crime could be read selectively to score political points.

The FBI’s crime reporting program and the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ crime victimization survey are generally seen as the Justice Department’s two major pillars of national crime statistics. While the FBI tries to collect crime data directly from more than 18,000 police agencies through its Uniform Crime Reporting program, the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) interviews 150,000 families across the country. The NCVS asks questions that capture crimes that were not reported to police as well as ones that were, which are then weighted in order to estimate crime victimization for more than 120 million U.S. households.

Both reports show a return to pre-pandemic levels of violent crime since the COVID-19 pandemic broke out three years prior, and a similar pattern: The violent crime rate exhibited significant fluctuations during the pandemic, but by 2022, it had returned to pre-pandemic levels.

Violent crime and victimization rates return to pre-pandemic level

During the pandemic, the country saw a significant uptick in homicides, shootings and aggravated assaults , which likely contributed to the increase seen in data reported by law enforcement. At the same time, violent crime victimizations — which included less acute forms of violent crime, such as assaults without weapons that did not lead to serious injuries — dipped. These violent crime victimizations mostly went unreported.

Murders are a good measurement for the most serious violent crimes, partially because they are almost always reported to police. According to the FBI’s crime statistics, the number of murders dropped by 6.1% from 2021 to 2022, but is still higher than where it was prior to the pandemic.

For some observers, the jump in serious violent crime was always bound to stabilize, as the shock from the early pandemic wore off. “Violent crime rates had been trending down for at least a decade. And when the pandemic hit, unsurprisingly, with this once-in-a-century event, you saw things shift,” said Kim Foxx, state’s attorney for Cook County, Illinois. “As we are coming out of the pandemic, the fact that we are now seeing those numbers trend downward again is not surprising to me.”

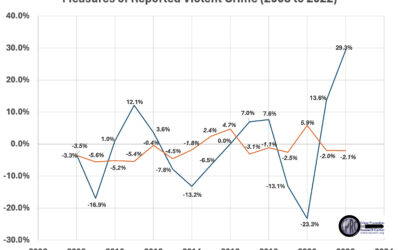

Despite the long-term trends, the two reports differ more than ever before on the year-over-year change in violent crime.

Since the methodologies for these two reports are different, it’s not unusual for them to show different trends on a particular year, said Richard Rosenfeld, a criminology professor at the University of Missouri, who recently wrote about this divergence for the Council on Criminal Justice . Over the past 30 years, these two reports’ difference in year-over-year violence trends has never been as big as it was last year.

In 2021, the FBI changed how it collects data from police departments, and as a result, that year’s crime data missed nearly 40% of police agencies . Bureau analysts estimated the missing data with statistical modeling, but the change led to the most incomplete picture of national crime since the FBI began collecting data in the 1930s, which created confusion on how crime trends changed . Last year, the FBI reversed the change and revived the previously-retired data collection system. They also gave agencies that didn’t submit data for 2021 a chance to submit their data retrospectively. Nearly 2,500 agencies took the FBI’s offer and submitted crime data through the old system for 2022, but it’s unclear how many did for 2021.

Experts said the lingering effect of that transition could be why the 2021-2022 trend is unreliable: If the 2021 crime data remains incomplete, it is difficult to compare it with the 2022 data.

These data gaps and disagreements create more space for politicians to spin unsubstantiated, murky narratives. When Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis announced his run for president, for example, he touted that Florida’s crime rate has reached a record-low under his administration. But he failed to mention that he relied on a crime rate estimation that was missing data from about half of the state’s law enforcement agencies , which policed 40% of the state’s population.

The FBI said it cannot address the difference between its crime data and the BJS’ victimization survey because it “cannot comment on another agency's report.”

In an interview, BJS statisticians said there’s no single factor that can neatly explain the divergence — the victimization survey and police statistics are designed to complement each other, and often reflect different aspects of criminal justice and victim’s issues.

“It would be nice to know what's happening with violent crime rates,” said Richard Rosenfeld. “But having two contrasting reports both coming out of the Justice Department enables politicians, or anyone else who has a horse in the race, to just cherry-pick the estimate that fits best with their [priorities] and ignore the other.”

While the Justice Department’s two reports diverged on recent violent crime trends, both showed an uptick in property crime from 2021 to 2022: The FBI’s crime data showed a 7.1% increase in property crime, while the victimization survey showed a 14.5% jump.

Property crime and victimization increased in 2022

The FBI's crime data showed a 7% increase in property crime from 2021 to 2022, which came after a decades-long downward trend. The Justice Department's crime victimization survey shows similar trends. Experts said motor vehicle theft and soaring inflation could be behind the increases.

In both reports, a sharp increase in motor vehicle theft and larceny were the main drivers for the increase in property crime. The former, criminologists said, can be partially attributed to the “Kia Boyz,” whose videos on how to steal Hyundai and Kia vehicles went viral on social media platforms .

In Chicago, the number of stolen Kia and Hyundais jumped 35 times over a couple of months — from 45 cars stolen in May 2022 to more than 1,400 cars stolen that October, according to data compiled by Vice . Data from other major cities, like Los Angeles, Denver and Milwaukee, showed similar trends.

Relentless inflation can also lead to more property crimes like theft and larceny , Rosenfeld said. Last summer, the inflation rate reached 9.1% — the highest in decades — which led many people to trade down on where they shop, and some traded down to purchasing stolen goods. While the inflation rate has since dropped , the 2022 crime data doesn’t reflect its effect yet.

Another trend that both Justice Department reports show is that young people experienced more violence in 2022.

The FBI’s crime data shows that while fatal and non-fatal gun violence against adults declined in 2022, both increased by more than 10% for young people who are under the age of 18. Similarly, the crime victimization survey shows that the violent victimization rate for people between the ages of 12 and 17 doubled last year — from 13 to 27 violent crimes per 1,000 youth, representing the age group that saw the biggest increase in violent victimization.

Researchers have theories on why violence against young people jumped, but caution that little is definitive. Kim Smith, the Director of Programs at the University of Chicago Crime Lab, points to school enrollment as a factor that might be one piece of the puzzle. Nationwide, school enrollment rates fell during the pandemic and are still yet to recover. The Crime Lab has found that in Chicago, a startling 90% of youth shooting victims were not active or enrolled at school at the time they were shot. “Education is the most protective factor against future violence involvement,” Smith said.

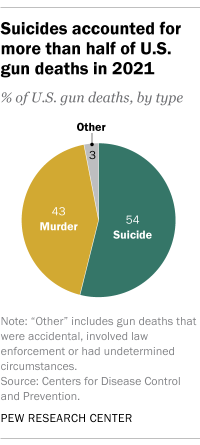

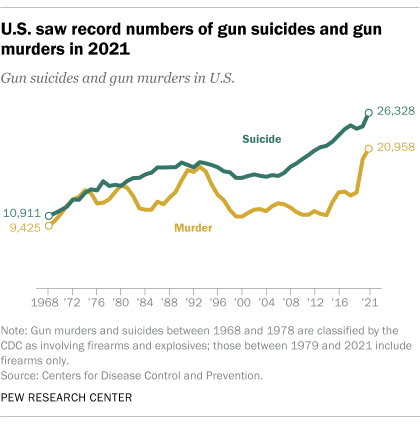

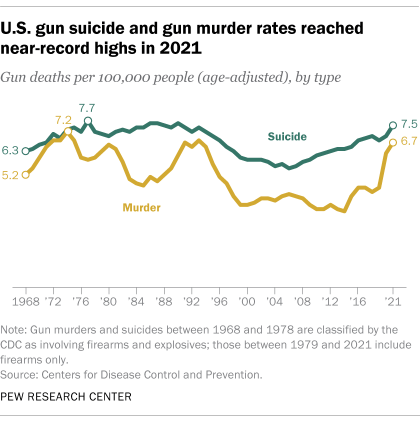

Other analysts have pointed to the increase in gun purchases since the beginning of the pandemic, and the sense of danger that many young people feel in their neighborhoods. “We had an influx of guns during the COVID shutdown, and an enormous amount of guns that entered the country and ended up on the streets,” said Jamila Hodge, executive director of the national violence prevention group Equal Justice USA. “That influx is reflected in the numbers of rising violence against young people — it's access to guns.”

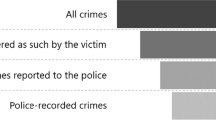

While the FBI continues trying to improve the national crime statistics, most property and violent crimes are not reported to the police, the victimization survey shows.

The survey asks victims if they reported crimes they experienced to the police. About 41% of violent crime victims said they reported the incident to the police. But the actual number of violent crimes police recorded is much lower.

More than half of crimes never got reported

The Justice Department's crime victimization survey shows millions of violent and property crimes were never reported to the police — often because the victim reported the incident to another authority, like a school official, or because they don't think police would take the matter seriously. Some crimes that are reported to the police never end up in the police report, and would not be counted by the FBI's crime stats.

While the BJS estimated more than 6 million violent crime victimizations, and estimated more than 2 million of those incidents were reported to the police, the FBI’s crime statistics only recorded 1.2 million incidents. In some incidents, a reported crime is not recorded by the police.

Our reporting has real impact on the criminal justice system

Our journalism establishes facts, exposes failures and examines solutions for a criminal justice system in crisis. If you believe in what we do, become a member today.

Weihua Li Twitter Email is a data reporter at The Marshall Project. She uses data analysis and visualization to tell stories about the criminal justice system. She studied journalism and comparative politics at Boston University and graduated from Columbia University with a master's degree in data journalism.

Jamiles Lartey Twitter Email is a New Orleans-based staff writer for The Marshall Project. Previously, he worked as a reporter for the Guardian covering issues of criminal justice, race and policing. Jamiles was a member of the team behind the award-winning online database “The Counted,” tracking police violence in 2015 and 2016. In 2016, he was named “Michael J. Feeney Emerging Journalist of the Year” by the National Association of Black Journalists.

Stay up to date on our reporting and analysis.

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Suggested Results

Informed citizens are our democracy’s best defense..

We respect your privacy .

- Research & Reports

Understanding the FBI’s 2021 Crime Data

Changes to the way the FBI reports national crime data may significantly complicate public understanding of recent crime trends.

- Accurate Crime Data

Click here for the latest FBI crime statistics >>

Policymakers, journalists, and the public look to data released annually by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) to understand state and national crime trends. Recently, the FBI rolled out a plan to modernize its reporting of crime data. Here’s what these changes mean for our understanding of recent crime trends.

What data does the FBI collect, and why does it matter?

For nearly a century , the FBI has collected data on offenses known to law enforcement from state and local agencies. Through its Uniform Crime Reporting program, the FBI aggregates these reports, applies quality control standards, uses estimates to fill gaps in their information, and then publishes both the raw data and trend analyses.

Researchers and policymakers have come to rely especially on an annual Uniform Crime Reporting publication, Crime in the United States , for understanding the previous year’s crime trends. This report generally contains high-level tables tracking important statistics like state, regional, and national violent crime rates. Each year’s annual report tends to come out roughly nine months after the end of the year it describes, although the summary of 2021 crime data is coming out slightly later.

How has the FBI historically collected and reported this data?

The FBI historically used two systems to collect crime data. The older of the two , the Summary Reporting System, tracked “monthly counts of the number of crimes known to law enforcement.” While easy to use, the system tended to gloss over important nuances. Among other things, it only counted the most serious offense in an incident, applying a “hierarchy rule” to determine which offenses were more serious than others. The system also focused on a limited number of types of crime and failed to capture details like the number of people involved.

More recently, the FBI and reporting agencies began using the National Incident Based Reporting System. This system tracks information in much greater detail than the Summary Reporting System and covers many additional types of crimes . The National Incident Based Reporting System also abandons the hierarchy rule, allowing law enforcement to report multiple offenses in a single incident . Consider a hypothetical robbery where the victim, injured in the attack, dies of his injuries. Under the Summary Reporting System, this incident would be recorded solely as a murder — the robbery would vanish from the FBI’s data. Under the National Incident Based Reporting System, both the robbery and murder would be counted along with considerable details about both offenses.

What is changing about crime data collection and reporting?

For years, the FBI accepted data in both formats. On January 1, 2021, however, the FBI stopped accepting data through the Summary Reporting System.

Unfortunately, despite the advantages of the newer National Incident Based Reporting System, many state and local law enforcement agencies have yet to make the switch. Law enforcement agencies covering just over half of the population reported a full year’s worth of data to the FBI in 2021. By comparison, the FBI’s recent reports have been based on data from agencies covering upwards of 95 percent of the population. The time and expense involved in updating outdated government computer systems are likely partly to blame for the delayed adoption of the new system.

The FBI recently started releasing some crime data on a quarterly basis. Participation by police departments has been relatively low so far but is expected to increase as more agencies make the switch. These quarterly reports, available through an online data dashboard , should eventually become a more reliable, regular source of crime data.

How will these changes affect crime data reported for 2021?

With so many agencies failing to report a full year of data for 2021, this year’s annual crime data release will have significant blind spots.

We know that the agency’s annual Crime in the United States report will feature “state-level data” and “a trend study comparing 2020 and 2021 data,” the latter drawing on partial data supplemented by estimates. It may also contain national estimates of crime trends — that is, data on whether rates of murder and other offenses rose or fell at the national level. If the FBI ultimately publishes these national estimates, they will likely be expressed with “ confidence intervals ” to indicate uncertainty.

Some major cities will be absent from the data too. San Francisco, for example, does not plan to complete its transition to National Incident Based Reporting System until 2025 , meaning it will be absent from FBI crime data until then. (Data on San Francisco crime trends will, of course, remain available directly from the city, but not in the new format.) And just 13 percent of law enforcement agencies in New York State reported a full year of data to the FBI in 2021. New York City was not among them. On the other hand, some regions of the country with a high rate of National Incident Based Reporting System adoption — like Michigan, Texas, and Virginia — will have robust data available, allowing researchers to use data from the FBI to study crime trends in some states in great detail.

What challenges does this present for our understanding of crime trends?

It will probably be impossible to speak of a precise “national” murder rate or “national” violent crime rate for 2021. Confidence intervals may make it difficult to determine whether the rates of some offenses rose or fell. Policymakers will have to exercise great care when using this limited data.

Some challenges will also remain even after National Incident Based Reporting System adoption is complete. Because it allows the reporting of multiple “offenses” per “incident,” comparing data from before and after the transition may create a false appearance of an increase in some offenses. Recall the example of the deadly robbery, above: the Summary Reporting System would count it as only one crime — a murder — while the National Incident Based Reporting System would count it as two violent crimes from that incident — a murder and a robbery. A 2019 study of early adopters of the National Incident Based Reporting System suggests roughly 90 percent of incidents involve just one offense, and increases in offense counts related to the transition may be in the range of just 2 to 5 percent. But that could still be enough to affect perceptions of whether crime is “rising” or “falling.”

What about other sources of crime data for 2021?

Critically, the FBI is not the only source of information on public safety. For one, the Centers for Disease Control provides 3-month and 12-month national homicide trends . This data, which uses a different methodology to track deaths but aligned with the FBI estimates in 2020 , shows homicides rising at a slower rate than in 2020.

Researchers and think tanks have also produced their own crime analyses. Most notably, the Council on Criminal Justice publishes regular reports on crime trends , including a collection of year-end 2021 data from 27 cities. Its findings track the CDC’s, suggesting that murder rose in 2021 but at a much slower pace than the previous year. Trends were mixed across other categories of crime, which are more challenging for private organizations to study. Crime data analyst Jeff Asher also tracks year-to-date murders in select cities on a data dashboard , and his tallies currently show major-city murders declining in 2022.

Lastly, while the FBI tracks offenses known to law enforcement agencies, it cannot account for crimes that are never reported. The National Criminal Victimization Survey, published by the Bureau of Justice Statistics, seeks to account for the difference using a national survey to estimate the rate at which people experience non-fatal crime and violence. This survey shows rates of non-fatal violent crime declining in 2020 and increasing very slightly in 2021.

Related Resources

U.S. Crime Rates and Trends — Analysis of FBI Crime Statistics

The FBI’s latest report on crime trends includes 2022 data for national, regional, and local levels.

Myths and Realities: Understanding Recent Trends in Violent Crime

Debunking the Myth of the ‘Migrant Crime Wave’

Data does not support claims that the United States is experiencing a surge in crime caused by immigrants.

Violent Crime Is Falling Nationwide — Here’s How We Know

Preliminary FBI data, however imperfect, confirms a sharp downward trend in crime, undercutting attempts to blame criminal justice reform for pandemic-era spikes in violence.

Why Inclusive Criminal Justice Research Matters

The hidden toll of new york city's misdemeanor system, myth vs. reality: trends in retail theft, fact-checking trump’s speech on crime and immigrants, trump misleads about crime and public safety, again, informed citizens are democracy’s best defense.

- Society ›

- Crime & Law Enforcement

Crime in the U.S.

State by state comparison, is crime increasing, key insights.

Detailed statistics

Most dangerous cities in the U.S. 2022, by violent crime rate

Least peaceful U.S. metropolitan areas 2012

Metropolitan areas - crime U.S. 2020, by type

Editor’s Picks Current statistics on this topic

Violent crime.

United States crime rate in 2022, by type of crime

Metropolitan areas - crime rate U.S. 2022, by type

Public assessment of crime as a serious issue U.S. 2000-2021

Further recommended statistics

- Basic Statistic Number of committed crimes in the U.S. 2022, by type

- Basic Statistic United States crime rate in 2022, by type of crime

- Basic Statistic Reported violent crime rate in the U.S. 2022, by state

- Premium Statistic Metropolitan areas - crime rate U.S. 2022, by type

- Basic Statistic Public assessment of crime as a serious issue U.S. 2000-2021

- Basic Statistic U.S. crime rate trend perception 1990-2022

Number of committed crimes in the U.S. 2022, by type

Number of committed crimes in the United States in 2022, by type of crime

Crime rate in the United States in 2022, by type of crime (per 100,000 inhabitants)

Reported violent crime rate in the U.S. 2022, by state

Reported violent crime rate in the United States in 2022, by state (per 100,000 of the population)

Crime rate in metropolitan areas in the United States in 2022, by type (per 100,000 inhabitants)

Percentage of the U.S. population that assesses crime as a serious problem from 2000 to 2021, nationwide and local

U.S. crime rate trend perception 1990-2022

Is there more crime in the U.S. than there was a year ago, or less?

- Basic Statistic U.S.: reported murder and nonnegligent manslaughter cases 1990-2022

- Basic Statistic USA - reported murder and nonnegligent manslaughter rate 1990-2022

- Basic Statistic U.S.: reported forcible rape cases 1990-2022

- Basic Statistic USA - reported forcible rape rate 1990-2022

- Basic Statistic U.S.: reported robbery cases 1990-2022

- Basic Statistic USA - reported robbery rate 1990-2022

- Basic Statistic U.S.: reported cases of aggravated assault 1990-2022

- Basic Statistic USA - reported aggravated assault rate 1990-2022

U.S.: reported murder and nonnegligent manslaughter cases 1990-2022

Number of reported murder and nonnegligent manslaughter cases in the United States from 1990 to 2022

USA - reported murder and nonnegligent manslaughter rate 1990-2022

Reported murder and nonnegligent manslaughter rate in the United States from 1990 to 2022 (per 100,000 of the population)

U.S.: reported forcible rape cases 1990-2022

Number of reported forcible rape cases in the United States from 1990 to 2022

USA - reported forcible rape rate 1990-2022

Reported forcible rape rate in the United States from 1990 to 2022 (per 100,000 of the population)

U.S.: reported robbery cases 1990-2022

Number of reported robbery cases in the United States from 1990 to 2022

USA - reported robbery rate 1990-2022

Reported robbery rate in the United States from 1990 to 2022 (per 100,000 of the population)

U.S.: reported cases of aggravated assault 1990-2022

Number of reported cases of aggravated assault in the United States from 1990 to 2022

USA - reported aggravated assault rate 1990-2022

Reported aggravated assault rate in the United States from 1990 to 2022 (per 100,000 of the population)

Property Crime

- Basic Statistic U.S.: reported larceny-theft cases 1990-2022

- Basic Statistic USA - reported larceny-theft rate 1990-2022

- Basic Statistic U.S.: reported burglary cases 1990-2022

- Basic Statistic USA - reported burglary rate 1990-2022

- Basic Statistic U.S.: reported motor vehicle theft cases 1990-2022

- Basic Statistic U.S.: reported motor vehicle theft rate 1990-2022

U.S.: reported larceny-theft cases 1990-2022

Number of reported larceny-theft cases in the United States from 1990 to 2022

USA - reported larceny-theft rate 1990-2022

Reported larceny-theft rate in the United States from 1990 to 2022 (per 100,000 of the population)

U.S.: reported burglary cases 1990-2022

Number of reported burglary cases in the United States from 1990 to 2022

USA - reported burglary rate 1990-2022

Reported burglary rate in the United States from 1990 to 2022 (per 100,000 of the population)

U.S.: reported motor vehicle theft cases 1990-2022

Number of reported motor vehicle theft cases in the United States from 1990 to 2022

U.S.: reported motor vehicle theft rate 1990-2022

Reported motor vehicle theft rate in the United States from 1990 to 2022 (per 100,000 of the population)

Crime Clearance & Arrests

- Basic Statistic Clearance rate - crime clearance rate U.S. 2022, by type

- Basic Statistic Regional distribution - crime clearance rate in the U.S. 2022

- Basic Statistic USA - number of arrests for all offenses 1990-2022

- Basic Statistic USA - arrest rate for all offenses 1990-2022

- Basic Statistic USA - number of arrests for violent offenses 1990-2022

- Basic Statistic USA - arrest rate for violent offenses 1990-2022

- Basic Statistic USA - number of arrests for property offenses 1990-2022

- Premium Statistic USA - arrest rate for property offenses 1990-2022

Clearance rate - crime clearance rate U.S. 2022, by type

Crime clearance rate in the United States in 2022, by type

Regional distribution - crime clearance rate in the U.S. 2022

Crime clearance rate in the United States in 2022, by region

USA - number of arrests for all offenses 1990-2022

Number of arrests for all offenses in the United States from 1990 to 2022

USA - arrest rate for all offenses 1990-2022

Arrest rate for all offenses in the United States from 1990 to 2022 (arrests per 100,000 people)

USA - number of arrests for violent offenses 1990-2022

Number of arrests for violent offenses in the United States from 1990 to 2022

USA - arrest rate for violent offenses 1990-2022

Arrest rate for violent offenses in the United States from 1990 to 2022 (arrests per 100,000 of the population)

USA - number of arrests for property offenses 1990-2022

Number of arrests for property offenses in United States from 1990 to 2022

USA - arrest rate for property offenses 1990-2022

Arrest rate for property offenses in the United States from 1990 to 2022 (per 100,000 of the population)

Further reports

Get the best reports to understand your industry.

Mon - Fri, 9am - 6pm (EST)

Mon - Fri, 9am - 5pm (SGT)

Mon - Fri, 10:00am - 6:00pm (JST)

Mon - Fri, 9:30am - 5pm (GMT)

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- SAGE - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Beyond Policing: The Problem of Crime in America

José luis morín.

1 John Jay College of Criminal Justice, CUNY, New York City, NY, USA

Photo by Francois Polito. Sculpture by Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd.

In 2020, the United States experienced the sharpest one-year rise in homicides on record. 1 In 2021, hate crimes also surged to their highest level in twelve years, with the largest increases being anti-Black crimes followed by anti-Asian crimes. 2 Pundits and politicians on the right have been quick to cite bail reform and “defunding” of police as reasons for the national rise in crime. Yet, the best available evidence points to other causes—among them, the massive social and economic dislocation resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic and the nationwide proliferation of guns along with the spread of racial and ethnic hatred and the violence it has roused.

While violent crime today [is] much lower . . . than in 1991, when [it] reached its highest point in recent history, public anxiety about crime is high.

While violent crime today registers at much lower levels than in 1991, when violent crime reached its highest point in recent history, 3 public anxiety about crime is high. Yet, more police and a redoubling of get-tough measures, however alluring, have not proven to be as effective as they appear. An examination of what is not driving the recent spike in crime as well as what probably is driving it—and revisiting the role that policing and the criminal justice system has played in U.S. society in reproducing racial, social, and economic inequalities—may move us closer to arriving at effective public safety solutions.

Starting with What Is Not: Bail Reform and Defunding the Police

The purpose of bail is to “provide reasonable assurance of court appearance or public safety,” 4 but, a 2022 briefing report by the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights suggests that the current cash bail system is also associated with producing deleterious racial disparities and economic inequities that undermine the presumption of innocence and worsen public safety. 5 The Commission report points out that low-income persons and people of color are disproportionately detained as a result of their inability to make bail, and persons of color are more often assigned higher bail amounts and considered more “dangerous” than whites. 6 To persons jailed simply because they could not afford bail, jail can result in severe trauma: loss of employment, housing, custody of a child; and economic hardship. 7 The think tank, Prison Policy Initiative, issued a report in 2016 documenting that cash bail “perpetuates an endless cycle of poverty and jail time.” 8 Nevertheless, with crime rates on the rise in 2020, bail reform became a political cudgel, and New York State’s law became a focal point of harsh condemnation from the GOP and conservative media outlets nationwide. But analyses of bail reform show no clear link between bail reform and spikes in crime. 9

To reduce unnecessary pretrial detention and ameliorate the harms associated with cash bail, New York State passed a bail reform law in 2019, ending cash bail for certain misdemeanors and most non-violent felony cases. Changes to the original law in 2020 and 2022 gave judges the ability to impose cash bail in more situations. 10 To date, research on the law shows no significant impact on crime rates. One study by the Times Union of Albany found that, of almost 100,000 cases, only a minimal number (2 percent) of individuals faced rearrest for a violent felony. As a result, as many as 80,000 people may have avoided incarceration while posing no documented threat to public safety. 11 And, looking at the national picture, the Brennan Center for Justice, a progressive law and public policy institute, points out that crime surged nationally, even in states that did not enact bail reform. 12

Another report—this one from the Office of New York City Comptroller Brad Lander—covered three calendar years and revealed that “pretrial rearrest rates remained nearly identical pre- and post-bail reform.” 13 The Comptroller’s report also warned that rollbacks to New York State’s bail reforms would “syphon money” from low-income communities. Indeed, families unable to make cash bail often turn to for-profit bail bond companies that require a non-refundable premium of 10 to 15 percent, even if no wrongdoing is found. Some form of collateral—such as a car or house—is also required. As the bail bond industry has become increasingly lucrative, growing numbers of indigent persons and their families face steep financial risks. 14 Critics of bail reform, by contrast, have produced little to no empirical evidence to support their position. Outspoken in its condemnation of bail reform, the New York Police Department has fallen short in backing up its assertions that bail reform was causing increases in gun violence. In 2021, when challenged by Albany legislators, NYPD Commissioner Dermot Shea, failed to provide any hard data to support his contention that bail reform is driving up crime. In the end, he was forced to retract his statements. 15

The term “defunding the police” has been variously understood. For the purpose of this discussion, I define the term not as a movement to eliminate police budgets, but as a call to lessen encounters with police by shifting funds away from aggressive and militarized forms of policing toward social services—such as mental health, addiction, education, and housing. In its most literal meaning, “defunding the police” is frequently cited as a reason for the surge in crime. As with bail, hard evidence to support this allegation has not materialized. Of twelve Democratic-led cities (including Austin, Louisville, Rochester, and St. Paul) cited by Republicans as examples of where crime purportedly rose due to police defunding, criminal justice scholars find no discernible link between defunding and crime. In fact, not all twelve cities defunded police; most did not substantially reduce police funding, and some actually increased their police budgets. 16

Funding quality educational programs, by comparison, has proven to be successful in diminishing crime. 17 For example, two studies—one in North Carolina and one in Michigan—showed that increased expenditures on primary schools helped to reduce adult crime by improving student academic success, which in turn provides a greater opportunity for socio-economic mobility. 18

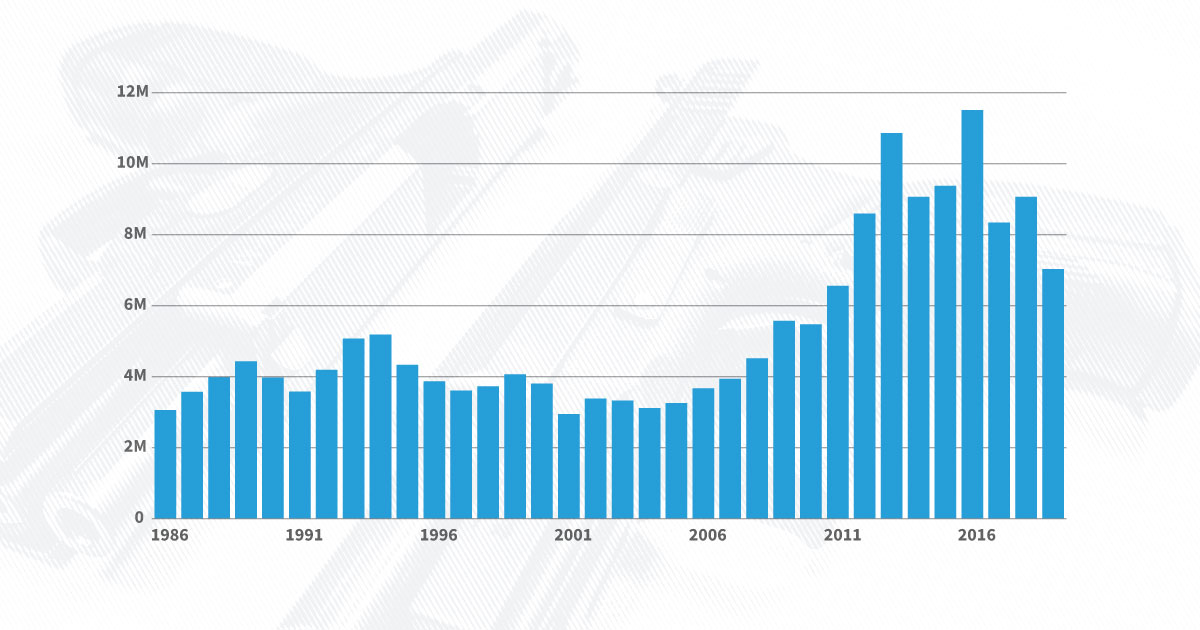

Examining What Is: Covid-19, Guns, and the Rise in Hate

Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, crime rates were relatively low. As the graph in Figure 1 demonstrates, the rate of violent crime offenses declined from a peak in 1991 of 758.2 per year to 398.5 per year in 2020. 19 The rate of homicide over the same period also dropped significantly, from its highest level in 1991 compared with 2020. 20 But the crime rate shows an uptick with the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020.

Rate of violent crime offenses by population in the United States: 1985-2020.

Source: Federal Bureau of Investigation, “Trend of Violent Crime from 1985 to 2020,” Crime Data Explorer, accessed September 19, 2022, https://crime-data-explorer.fr.cloud.gov/pages/explorer/crime/crime-trend .

Note. Rate per 100,000 people, by year.

The pandemic is widely understood as the cause of immense social and economic dislocation, disproportionately disadvantaging children, communities of color, immigrants, LGBTQIA+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning, intersex, asexual, and more) youth, and persons with disabilities. 21 The pandemic also exposed and aggravated deeply entrenched inequities in health care, poverty, education, housing, and racial segregation. Its impact on mental health and psychosocial well-being, substance abuse, and domestic violence has become a focus of attention in relation to the rise in crime. All these factors are related to the rise in crime.

As gun violence became a major driver of crime nationwide, hate crimes also spiked. During the pandemic, reports of hate crimes reached a twelve-year high.

The proliferation of guns and gun violence nationwide appears to have contributed greatly to the spike in homicides. Sharp increases in gun purchases coincided with the start of the pandemic in 2020 and continued well into 2021. 22 The increased supply of guns as well as the types of guns—high-powered semi-automatic weapons, for instance—has been linked to the surge in gun violence. 23 Criminologists Philip J. Cook and Jens Ludwig deem gun violence and the fear of gun violence as devastating to the lives of children and families around the country, most especially in low-income neighborhoods and communities of color. In their estimation, public safety begins with addressing the needs of communities most vulnerable to gun violence, and that includes investments in social policies, such as summer jobs for teens, cleaning vacant lots, and spending more on social programs—all of which have been shown to reduce homicide rates. 24

As gun violence became a major driver of crime nationwide, hate crimes also spiked. During the pandemic, reports of hate crimes reached a twelve-year high (see Figure 2 ). 25 While anti-Black incidents topped the list of hate crimes based on race, people of Asian descent experienced a steep rise in anti-Asian violence and crime, with a 169 percent increase in reports of anti-Asian hate crimes in fifteen of America’s largest cities and counties in the first quarter of 2021 when compared with the first quarter of 2020. 26

Hate crimes in the United States: 1995-2020.

Source: Hate Crime in the United States Incident Analysis, 1995 to 2020,” Crime Data Explorer, accessed October 6, 2022, https://crime-data-explorer.fr.cloud.gov/pages/explorer/crime/hate-crime .

. . . [I]t is no surprise that the earliest form of policing in the United States was the slave patrol, established in 1704.

Even before the pandemic, former President Donald Trump’s xenophobic, racially inflammatory rhetoric and policies were understood as green-lighting racial and ethnic violence. But unfortunately, this is not unique in our history. Hate groups of different types—white nationalists, neo-Nazis, and anti-government paramilitary organizations—historically have played a major role in the spread of hatred and violence.

Policing: The Historical Context

The history of policing in the United States may help us determine the best policies and practices to advance public safety without subjecting communities to abusive police practices.

The institution of slavery—and its continuance—was integral to the founding of the nation. So, it is no surprise that the earliest form of policing in the United States was the slave patrol, established in 1704. 27 The patrols were designed to maintain the system of slave labor and to capture runaway slaves. Patrollers, often armed, used violence to terrorize slaves and deter rebellions. In 1787, the apprehension of slaves was codified in the U.S. Constitution in Article IV, Section 2, commonly referred to as the “Fugitive Slave Clause.” The intent of the clause, which passed unanimously, was “to require fugitive slaves and servants to be delivered up like criminals.” 28 The clause was nullified by passage of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865. Slave patrols were also disbanded after the Civil War, only to be replaced by other forms of policing Black lives. These included the Ku Klux Klan and the institution of Jim Crow, which was maintained in Southern states by police who often used intimidation and terror to maintain a brutally oppressive system. 29

By the 1990s, the acquisition of military equipment by police forces across the country became ubiquitous . . .

Over time, police and other law enforcement agencies helped preserve and reproduce race and class inequality, as in the 1918 massacre of fifteen Mexican men in Porvenir, Texas and the 1921 Tulsa, Oklahoma massacre that resulted in destruction of a prosperous Black neighborhood. 30 Business and economic elites—such as Andrew Carnegie and Henry Clay Frick—also relied on police or private law enforcement agencies to employ deadly force against workers and union organizers. The massacre of strikers at the Homestead Steelworks in 1882 is one example; the 1897 massacre of coal miners in Lattimer, Pennsylvania is another. 31

The militarization of policing arose in the 1960s, amid cries for a “war on crime” and a “war on drugs.” In Los Angeles, Daryl F. Gates, then head of the Los Angeles Police Department, spearheaded an effort to outfit local police departments with military-grade armaments and equipment to handle emergencies, such as hostage situations and sniper shootings. By the 1990s, the acquisition of military equipment by police forces across the country became ubiquitous through a federal program that encouraged the militarization of law enforcement. 32 But, as a report from the American Civil Liberties Union documents, militarization, too, frequently came at the expense of individual civil liberties, particularly in Black and Latinx communities. 33

Police practices—including chokeholds, stop and frisks, and “broken windows” tactics—have come into question as the victims of police brutality have come into sharp focus. From George Floyd and Breonna Taylor to Eric Garner and Freddy Gray, their names are now familiar and—for some—synonymous with policing in the United States. Yet, despite the bright light shone on these cases, fatal police shootings continue to rise. According to the Washington Post , “2021 was the deadliest year for police shootings” since the newspaper began tracking such incidents in 2015. 34

Centering Communities to Advance Public Safety

Following incidents of excessive police force, municipalities commonly opt for police retraining. However, as some analysts observe, retraining is too often inadequate or ineffective in resolving or mitigating a recurrence of police misconduct. 35 Similarly, while there is merit to hiring police officers who resemble members of the communities they serve, a diverse police force does not necessarily decrease incidents of brutality against persons of color. Regrettably, research shows that a Black officer may be more inclined to use force in encounters with Black community members than white officers. 36 These officers often face the dilemma of how to fit into a police culture that commonly takes an “us against them” approach when patrolling communities. Aggressive behavior can be one way to prove that they belong. 37

Ensuring public safety requires attention to non-violent as well as violent situations. In the context of rising crime, expectations that police officers can resolve a wide array of concerns are high. Police are often called to aid unhoused people, assist individuals experiencing emotional difficulties, or settle domestic disputes. The police are not trained to handle such matters. Social workers or other trained professionals are much better equipped to deal with problems of this nature.

National data on homicide “clearance rates”—the rate at which homicide cases are resolved—also raise questions about the effectiveness of policing. In 2020, the clearance rate was just under 50 percent, representing a historic low and “a long, steady drop since the early 1980s, when police cleared about 70 percent of all homicides.” 38 The pandemic and the spike in violent crimes may help to explain the fall in clearance rates, but the data still beg the question of whether policing itself is sufficiently effective in meeting the public safety needs of contemporary society.

In determining the best approaches moving forward, the intractability of problems related to policing cannot be ignored. Policing remains a leading cause of death for young men in the United States. 39 People of color are most vulnerable, with Black men facing a one in one thousand risk of being killed by police. As we have seen, violent encounters with the police have profound effects on whole communities and neighborhoods, affecting the health and the life chances of individuals in those communities.

Community concerns about crime are real, especially in the most vulnerable communities of color. But the alternative of aggressive policing and mass incarceration has resulted in tremendous harm and cannot be the ultimate solution.

The high rate of recidivism—the rate at which persons released from prison are rearrested—does not point to a system that works well. The most recent Bureau of Justice Statistics covering a ten-year period (2008-2018) shows that “about 66 percent of prisoners released across 24 states in 2008 were rearrested within three years, and 82 percent were arrested within ten years.” 40 Recidivism rates this high should call into question the adequacy of the criminal justice system. It should also raise the issue of whether a system, focused on retribution rather than rehabilitation and public health, is actually serving the cause of public safety. These questions have found resonance with advocates of prison abolition. These abolitionists include scholars Angela Davis, Gina Dent, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, and Alex Vitale. In their view, the current structure of policing and incarceration is profoundly connected to systems of oppression. What is required, they believe, is a system that operates within a social-justice framework—one that substantively engages communities in maintaining their own safety. Such a system, they believe, would reaffirm the values of self-determination and community empowerment. 41 Rather than simply replicating punitive approaches that disproportionally and discriminatorily harm communities of color, abolitionists look to broader social solutions to the problem of crime—remedial measures such as restitution, reconciliation, rehabilitation, and restorative justice.

While a complete transformation of policing and the criminal justice system may not be on the immediate horizon, a variety of initiatives in recent years have sought to address the basic human needs of communities while minimizing negative interactions with police. In a 2021 experiment in Brooklyn, for example, the Brownsville Safety Alliance—a community-based organization—arranged for precinct police to disengage from their usual assignments in a two-block area for five days. In their place, trained violence interrupters and crisis management groups were charged with securing public safety. Although limited in duration, this pilot program has been praised by New York City officials as well as members of the community as “a model for the future.” 42 A range of other crime-reduction strategies that do not involve the deployment of police have also produced promising results. These include improvements in street lighting, clean-up of empty lots, provision of quality mental health and drug treatment services, and expansion of Medicaid services. 43

Community concerns about crime are real, especially in the most vulnerable communities of color. But the alternative of aggressive policing and mass incarceration has resulted in tremendous harm and cannot be the ultimate solution. The best, most promising option is to center communities and underlying social and economic inequality as the means to advance public safety.

Author Biography

José Luis Morín is a professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, City University of New York.

1 Jeff Asher, “Murder Rose by almost 30% in 2020: It’s Rising at a Slower Rate in 2021,” New York Times , September 22, 2021, updated November 15, 2021, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/22/upshot/murder-rise-2020.html .

2 Federal Bureau of Investigation, “FBI Releases 2020 Hate Crime Statistics,” August 30, 2021, available at https://www.fbi.gov/news/press-releases/press-releases/fbi-releases-2020-hate-crime-statistics ; See also, Christina Carrega and Priya Krishnakumar, “Hate Crime Reports in US Surge to the Highest Level in 12 Years, FBI Says,” CNN , October 26, 2021, available at https://www.cnn.com/2021/08/30/us/fbi-report-hate-crimes-rose-2020/index.html .

3 Federal Bureau of Investigation, “Trend of Violent Crime from 1985 to 2020,” Crime Data Explorer, available at https://crime-data-explorer.fr.cloud.gov/pages/explorer/crime/crime-trend .

4 Timothy Schnacke, “Fundamentals of Bail: A Resource Guide for Pretrial Practitioners and a Framework for American Pretrial Reform,” National Institute of Corrections, September 2, 2014, available at https://s3.amazonaws.com/static.nicic.gov/Library/028360.pdf .

5 U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, “Civil Rights Implications of Cash Bail,” Briefing Report, Washington, DC, available at https://www.usccr.gov/reports/2021/civil-rights-implications-cash-bail .

6 U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, 10.

7 Adureh Onyekwere, “How Cash Bail Works,” Brennan Center for Justice at NYU Law, December 10, 2019, updated February 24, 2021, available at https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/how-cash-bail-works#:~:text=Cash%20bail%20is%20used%20as,is%20forfeited%20to%20the%20government ; See also, U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, 6-8.

8 Bernadette Rabuy and Daniel Kopf, “Detaining the Poor: How Money Bail Perpetuates an Endless Cycle of Poverty and Jail Time,” Prison Policy Initiative , May 10, 2016, available at https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/DetainingThePoor.pdf .

9 Ames Grawert and Noah Kim, “The Facts on Bail Reform and Crime Rates in New York State,” Brennan Center for Justice at NYU Law, March 22, 2022, available at https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/facts-bail-reform-and-crime-rates-new-york-state .

10 Taryn A. Merkl, “New York’s Latest Bail Law Changes Explained,” Brennan Center for Justice at NYU Law, April 16, 2020, available at https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/analysis-opinion/new-yorks-latest-bail-law-changes-explained ; See also, Jon Campbell, “NY Lawmakers Pass $220B Budget that Changes Bail Reform, Approves Buffalo Bills Stadium Funding,” Gothamist, April 9, 2022, available at https://gothamist.com/news/ny-lawmakers-pass-220b-budget-that-changes-bail-reform-approves-buffalo-bills-stadium-funding?utm_source=sfmc&utm_medium=nypr-email&utm_campaign=Gothamist%20Daily%20Newsletter&utm_term=https%3A%2F%2Fgothamist.com%2Fnews%2Fny-lawmakers-pass-220b-budget-that-changes-bail-reform-approves-buffalo-bills-stadium-funding&utm_id=88591&sfmc_id=2849872&utm_content=202249 .

11 Grawert and Kim, “Bail Reform and Crime.”

12 Grawert and Kim, “Bail Reform and Crime.”

13 Office of New York City Comptroller Brad Lander, “NYC Bail Trends Since 2019,” available at https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/nyc-bail-trends-since-2019/ .

14 Gillian B. White, “Who Really Makes Money Off of Bail Bonds?” The Atlantic , May 12, 2017, available at https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2017/05/bail-bonds/526542/ ; See also, Onyekwere, “How Cash Bail Works”; Rabuy and Kopf, “Detaining the Poor.”

15 “During Questioning in Albany, NYPD Commissioner Shea Backtracks on Bail Reform Law as Big Reason for Gun Violence,” CBS New York , October 14, 2021, available at https://www.cbsnews.com/newyork/news/bail-reform-nypd-commissioner-dermot-shea-assembly-hearing/ .

16 Daniel Funke, “Fact Check: No Evidence Defunding Police to Blame for Homicide Increases, Experts Say,” USA TODAY , January 28, 2022, available at https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/factcheck/2022/01/28/fact-check-police-funding-not-linked-homicide-spikes-experts-say/9054639002/ .

17 See, for example, Brian Bell, Rui Costa, and Stephen Machin, “Why Does Education Reduce Crime?” Journal of Political Economy 130, no. 3 (2022): 732-65.

18 David J. Deming, “Better Schools, Less Crime?” Quarterly Journal of Economics 126 (2011): 2063-115; See also, E. Jason Baron, Joshua M. Hyman, and Brittany N. Vasquez, “Public School Funding, School Quality, and Adult Crime,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 29855, available at http://www.nber.org/papers/w29855 .

19 FBI, “Trend of Violent Crime from 1985 to 2020.”

20 FBI, “Trend of Homicide from 1985-2020,” Crime Data Explorer, available at https://crime-data-explorer.fr.cloud.gov/pages/explorer/crime/crime-trend .

21 Charles Oberg, H.R. Hodges, Sarah Gander, Rita Nathawad, and Diana Cutts. “The Impact of COVID-19 on Children’s Lives in the United States: Amplified Inequities and a Just Path to Recovery,” Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care 52, no. 7 (2022): 1-17.

22 Sabrina Tavernise, “An Arms Race in America: Gun Buying Spiked during the Pandemic. It’s Still Up,” New York Times , May 29, 2021, updated May 30, 2021, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/29/us/gun-purchases-ownership-pandemic.html .

23 Tavernise, “An Arms Race in America.”

24 Philip J. Cook and Jens Ludwig, “Gun Violence Is THE Crime Problem,” Vital City . March 2, 2022, available at https://www.vitalcitynyc.org/articles/gun-violence-is-the-crime-problem .

25 Carrega and Krishnakumar, “Hate Crime Reports in US Surge”; FBI, “Hate Crime in the United States Incident Analysis, 1995-2020,” Crime Data Explorer,” accessed October 6, 2022, https://crime-data-explorer.fr.cloud.gov/pages/explorer/crime/hate-crime .

26 Center for the Study of Hate & Extremism at California State University, “Report to the Nation: Anti-Asian Prejudice & Hate Crime 2021,” (2021), available at https://www.csusb.edu/sites/default/files/Report%20to%20the%20Nation%20-%20Anti-Asian%20Hate%202020%20Final%20Draft%20-%20As%20of%20Apr%2028%202021%2010%20AM%20corrected.pdf .

27 Chelsea Hansen, “Slave Patrols: An Early Form of American Policing,” National Law Enforcement Museum , July 10, 2019, available at https://lawenforcementmuseum.org/2019/07/10/slave-patrols-an-early-form-of-american-policing/ ; See also, Jill Lepore, “The Invention of the Police: Why Did American Policing Get so Big, so Fast? The Answer, Mainly, Is Slavery,” The New Yorker , July 13, 2020, available at https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/07/20/the-invention-of-the-police .

28 Library of Congress, “The Fugitive Slave Clause,” Constitution Annotated, available at https://constitution.congress.gov/browse/essay/artIV-S2-C3-1/ALDE_00013571/ [“clause”].

29 Hansen, “Slave Patrols.”

30 Zinn Education Project, “Massacres in U.S. History,” available at https://www.zinnedproject.org/collection/massacres-us/ .

31 Gary Potter, “The History of Policing in the United States, Part 3,” EKU Online . Eastern Kentucky University. July 9, 2013, available at https://ekuonline.eku.edu/blog/police-studies/the-history-of-policing-in-the-united-states-part-3/ ; See also, Paul A. Shackel, “How a 1897 Massacre of Pennsylvania Coal Miners Morphed from a Galvanizing Crisis to Forgotten History,” Smithsonian Magazine , March 13, 2019, available at https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/how-1897-massacre-pennsylvania-coal-miners-morphed-galvanizing-crisis-forgotten-history-180971695/ .

32 Radley Balko, Rise of the Warrior Cop: The Militarization of America’s Police Forces , (New York: Public Affairs, 2021).

33 American Civil Liberties Union, “War Comes Home: The Excessive Militarization of American Policing” (2014), available at https://www.aclu.org/sites/default/files/assets/jus14-warcomeshome-report-web-rel1.pdf .

34 The Marshall Project, “How Policing Has—and Hasn’t—Changed since George Floyd,” August 6, 2022, available at https://www.themarshallproject.org/2022/08/06/how-policing-has-and-hasn-t-changed-since-george-floyd .

35 See, for example, Alex S. Vitale, The End of Policing (London: Verso Books, 2017), 4-11.

36 Vitale, The End of Policing , 11-13; See also, “Does Diversifying Police Forces Reduce Brutality against Minorities?” NPR , June 22, 2020, available at https://www.npr.org/2020/06/22/881559659/does-diversifying-police-forces-reduce-brutality-against-minorities .

37 Vitale, The End of Policing ; See also, José Luis Morín, Latino/a Rights and Justice in the United States: Perspectives and Approaches , 2nd edition (Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 2009), 106-15; Balko, Rise of the Warrior Cop .

38 Weihua Li and Jamiles Lartey, “As Murders Spiked, Police Solved about Half in 2020,” The Marshall Project , January 12, 2022, available at https://www.themarshallproject.org/2022/01/12/as-murders-spiked-police-solved-about-half-in-2020 .

39 Frank Edwards, Hedwig Lee, and Michael Esposito, “Risk of being Killed by Police Use of Force in the United States by Age, Race–Ethnicity, and Sex,” PNAS 116, no. 34 (2019): 16793-8.

40 Leonardo Antenangeli and Matthew R. Durose, Recidivism of Prisoners Released in 24 States in 2008: A 10-Year Follow-up Period (2008–2018), Bureau of Justice Statistics NCJ Number 256094 September 2021, available at https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/recidivism-prisoners-released-24-states-2008-10-year-follow-period-2008-2018 .

41 See, for example, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Golden Gulag: Prisons Surplus, Crisis, and Oppression in Globalizing California (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007); Vitale, The End of Policing ; Derecka Purnell, Becoming Abolitionists: Police, Protests, and the Pursuit of Freedom (New York: Astra House, 2021); Mariame Kaba, We Do This ’Til We Free Us: Abolitionist Organizing and Transforming Justice (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2021); Angela Y. Davis, Gina Dent, Erica R. Meiners, and Beth Richie. Abolition. Feminism. Now (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2022).

42 Yoav Gonen and Eileen Grench, “Five Days without Cops: Could Brooklyn Policing Experiment Be a ‘Model for the Future’?” The City , January 3, 2021, available at https://www.thecity.nyc/2021/1/3/22211709/nypd-cops-brooklyn-brownsville-experiment-defund-police .

43 Shaila Dewan. “‘Re-fund the Police’? Why It might Not Reduce Crime,” New York Times , November 8, 2021, updated November 11, 2021, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/08/us/police-crime.html .

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Sorry, we did not find any matching results.

We frequently add data and we're interested in what would be useful to people. If you have a specific recommendation, you can reach us at [email protected] .

We are in the process of adding data at the state and local level. Sign up on our mailing list here to be the first to know when it is available.

Search tips:

• Check your spelling

• Try other search terms

• Use fewer words

How is crime measured in the US?

The FBI relied heavily on estimates for 2021 crime statistics due to low response rates from law enforcement agencies.

Published Wed, May 17, 2023 by the USAFacts Team

Is crime in the US increasing or decreasing? It’s a question that the Department of Justice tries to answer using two primary sources: victim surveys and administrative data from law enforcement agencies.

The Bureau of Justice Statistics’ National Crime Victimization Survey captures information directly from victims, while the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program collects data from law enforcement agencies. These data sources, which account for crimes that are reported to the police as well as those that aren’t, together provide a more comprehensive understanding of crime in the US.

In 2021, however, with only 64% of the US population covered by law enforcement agency participation, the FBI relied on crime estimates to compensate for the missing data.

Local and state agencies are not required by federal law to submit crime data to the FBI, making their participation voluntary.

FBI adopts a more detailed reporting system, law enforcement participation drops

The FBI has been collecting crime data from local law enforcement agencies through the Summary Reporting System (SRS) since 1929. SRS was replaced in 2021 by the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS), a more detailed reporting system.

In addition to removing the SRS Hierarchy Rule, which only recorded the most serious offense in a crime incident, NIBRS captures more information than SRS by allowing the data to count up to 10 offenses per incident and including more offense categories.

Although the FBI created NIBRS in the 1980s , law enforcement agencies were given until January 1, 2021, to switch to the new system, and some continued to submit data to the SRS until the deadline.

The results of the transition have been mixed. While NIBRS collects data for 42 more types of offenses and collects more details about victims and offenders than SRS, technological and cost-related challenges meant some law enforcement agencies missed the deadline for the transition.

Most agencies take a year to transition to NIBRS, while larger or more complex ones may need two years. This involves certification, implementing new software, personnel training, and acquiring funding. Washington, DC’s, government spent $50,493 to implement NIBRS in 2021 , while the Maryland governor's office budgeted $2.5 million to ensure full NIBRS compliance for all local law enforcement agencies by the federal deadline.

Through the NIBRS Statewide Compliance Initiative, the Governor’s Office of Crime Prevention, Youth, and Victim Services has allocated approximately $2.5 million in Justice Department funding to support Maryland’s efforts to ensure 100% NIBRS compliance for all local law enforcement agencies by the federal deadline. The office anticipates making up to 50 awards. Priority will be given to agencies requesting technology enhancements.

Local law enforcement agency participation in SRS has historically covered greater than 90% of the US population , a number that dropped to 64% in 2021 with NIBRS. The FBI fell 16 percentage points short of its goal to have data from agencies serving more than 80% of the US population by 2021.

Notably, law enforcement agencies from New York City and Los Angeles, the two most populous cities in the US, did not submit data to NIBRS in 2021 . The entire state of Florida also did not submit data to NIBRS that year.

Although many cities didn't provide data to the FBI in 2021, the FBI employs statistical methods , such as weighting, to fill in data gaps and produce crime figures that are representative of the country.

For a fuller picture of crime in the US , read about which states have the least and most crime . Get USAFacts data in your inbox by subscribing to our weekly newsletter .

Explore more of USAFacts

Related articles, firearm background checks: explained.

The state of domestic terrorism in the US

The latest government data on school shootings

How many guns are made in the US?

Related Data

Firearm Deaths in the US: Statistics and Trends

Firearm background checks

38.88 million

Data delivered to your inbox

Keep up with the latest data and most popular content.

SIGN UP FOR THE NEWSLETTER

Crime Prevention Research Center

Dedicated to conducting academic quality research on the relationship between laws regulating the ownership or use of guns, crime, and public safety, latest research.

The Rate that Police Officers are Murdered with their Own Weapon

by johnrlott | May 23, 2024 | Original Research

Often, people point to the rate at which police officers are murdered with their guns. Over the 17 years from 2002 to 2018, there were 34 officers murdered with their gun compared to the 878 officers who were murdered — 3.87% of the total. But the relevant comparison...

How reliable are the FBI’s Report of Violent Crime Data? There are some major problems.

by johnrlott | Apr 20, 2024 | Original Research

The U.S. employs two distinct measures of crime. The Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Uniform Crime Reporting program counts the number of crimes reported to police annually. The Bureau of Justice Statistics, in its National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), asks...

The Latest Research

Get our latest research on crime sent straight to you. Find out what law enforcement and gun ownership policies will make people safer

Latest Columns

The Washington Times: Don’t defend yourself in New York City: If you do, you will be prosecuted

by johnrlott | May 29, 2024 | op-ed

Dr. John Lott has a new op-ed at the Washington Times. . The message in New York City is clear: don’t try defending yourself or anyone else from violence. If you do, you will be prosecuted by the city’s District Attorneys. . New Yorkers are likely to be very familiar...

At Townhall: The FBI’s Crime Data Have Real Problems

by johnrlott | May 15, 2024 | op-ed

Dr. John Lott has a new piece up at Townhall that continues our investigation into the problems with the FBI crime data. The news media relies almost exclusively on FBI data to report on changes in crime rates. But there is strong evidence that FBI data...

Letter Submitted to USA Today: Responding to “FBI data shows America is seeing a ‘considerable’ drop in crime. Trump says the opposite.”

by johnrlott | May 12, 2024 | op-ed

When USA Today had two articles claiming that Trump was wrong in claiming that crime was increasing, Dr. John Lott submitted the following letter to the editor, but the newspaper didn't run the letter. Dear Letters Editor: USA Today erroneously dismisses former...

At The Tennessean: My husband was killed in a ‘gun free zone.’ Arm teachers for safety and to save lives.

by johnrlott | May 1, 2024 | op-ed

The CPRC's Nikki Goeser has a new op-ed in the Tennessean. . My husband Ben and I used to run a mobile karaoke business in Nashville. . Every Thursday evening, we would load up our vehicle and head to a popular restaurant to help facilitate a night of good music and...

At the Wall Street Journal: The Media Say Crime Is Going Down. Don’t Believe It: The decline in reported crimes is a function of less reporting, not less crime.

by johnrlott | Apr 24, 2024 | Crime , op-ed

Dr. John Lott has a new op-ed at the Wall Street Journal. News outlets claim that Americans mistakenly believe violent crime is rising. A Gallup survey last year found that 92% of Republicans and 58% of Democrats thought crime was increasing. A February...

At Townhall: City where police emergency response time is 36 minutes wants to ban Civilians Carrying Guns for protection

by johnrlott | Apr 24, 2024 | op-ed

Dr. John Lott has a new piece at Townhall In 2023, New Orleans had the third highest per capita murder rate in the country according to the FBI. Last week, New Orleans Police Chief Anne Kirkpatrick claimed that the city can lower...

At the Missoulian: Duty to uphold the laws of the land rests on Tester’s shoulders

by johnrlott | Apr 15, 2024 | op-ed

Dr. John Lott has a new piece at the Missoulian. . Will Sen. Jon Tester provide the necessary vote this week to hold an impeachment trial for Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas? Democrats might think that they can protect vulnerable Democrats such as...

At the Colorado Springs Gazette: Registries could be used to enforce gun bans

by johnrlott | Apr 14, 2024 | op-ed

John Lott and Colorado state Representative Ryan Armagost have a piece in Colorado's second largest newspaper the Colorado Springs Gazette. . Credit card companies soon might be tracking purchases of firearms and ammunition in Colorado. A bill that would flag...

Popular posts:

- Violent Crime Rates by Race

- UPDATED: Compiling Cases where concealed handgun…

- Massive errors in FBI’s Active Shooting…

- UPDATED: Mass Public Shootings keep occurring in…

- Twenty-five states have Constitutional Carry

- Massive errors in FBI’s Active Shooting Reports from…

Public Speech in São Paulo, Brazil on July 5th

by johnrlott | May 29, 2024 | Talk

Dr. John Lott will give talks in Santiago, Chile, at the end of June and then travel to Brazil, where he will give more talks.

Conference talk on the Collapse of Law Enforcement in the US

by RW | May 12, 2024 | Talk

https://youtu.be/b24Qep3c2nE Dr. John Lott gave a talk at a Berkeley Springs 2024 Conference on the collapse of law enforcement in the US. Dr. Lott disagreed with what he was told were the concerns of others at the conference regarding legal immigration and also...

Crime Prevention Research Center fellow Amanda Collins Johnson talked about being raped in college and her advocacy for “campus carry” gun laws

by johnrlott | Apr 4, 2024 | Talk

Crime Prevention Research Center fellow Amanda Collins Johnson talked about being raped in college and her advocacy for “campus carry” gun laws. This event was hosted on February 29th, 2024 by the Clare Boothe Luce Center for Conservative Women in Virginia. C-SPAN...

Media Appearances

On Iowa’s KXEL: To Discuss Crime Data

by RW | May 27, 2024 | Radio

Dr. John Lott appeared on Iowa’s giant 50,000-watt KXEL-AM radio station to discuss his new op-ed at the Wall Street Journal titled "The Media Say Crime Is Going Down. Don’t Believe It: The decline in reported crimes is a function of less reporting, not less crime."...

On WAVA FM’s The Drive Home Show: To Discuss AI’s Left-Wing Bias and Decline in Reported Crimes

by RW | May 26, 2024 | Radio

Dr. John Lott talked to Greg Seltz on WAVA's The Drive Home Show about AI's left-wing bias and the collapse in law enforcement. See also Dr. Lott's new op-ed at Real Clear Politics ("AI’s Left-wing Bias on Crime and Gun Control") and his latest piece at the Wall...

On The Rod Arquette Show in Salt Lake City: The Media Say Crime Is Going Down. Don’t Believe It.

by RW | May 25, 2024 | Radio

Dr. John Lott appeared on KNRS’s The Rod Arquette Show in Salt Lake City to discuss his new op-ed at the Wall Street Journal about why we should not believe the media when they say crime numbers are decreasing.(Thursday, April 25, 2024, from 6:05 to 6:15 PM)

All Our Posts

CPRC’s Nikki Goeser on Armed American Radio: Teachers carrying guns to protect students in Tennessee

by Nikki Goeser | May 29, 2024 | Campus carry , Media Bias

Senior Fellow Nikki Goeser speaks with host Mark Walters about Tennessee Teachers now being able to carry concealed to protect their students. Nikki also discusses some of the media bias she has experienced when standing up for gun rights. Sunday, May 19, 2024

Is there a massive change in whether both blacks and whites believe Republicans or Democrats have done the most for blacks?

by johnrlott | May 28, 2024 | Survey

Rasmussen Reports surveyed likely voters in 2020 and 2024 to determine whether they thought Republicans or Democrats had done the most for blacks. In May 2020, only 18% of blacks thought that Republicans had done the most, but that increased to 32% in May 2024. Large...

CPRC’s Nikki Goeser on the Tudor Dixon Podcast

by Nikki Goeser | May 28, 2024 | gun control , Gun Free Zones , Second Amendment

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RJAOvDaogUw May 6, 2024 In this episode, Tudor talks with Senior Fellow of the Crime Prevention Research Center Nikki Goeser, a victims' rights advocate, who shares her story of her husband being brutally murdered by her stalker. She...

The accuracy of crime statistics: assessing the impact of police data bias on geographic crime analysis

- Open access

- Published: 26 March 2021

- Volume 18 , pages 515–541, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- David Buil-Gil ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7549-6317 1 ,

- Angelo Moretti ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6543-9418 2 &

- Samuel H. Langton ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1322-1553 3

26k Accesses

25 Citations

32 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

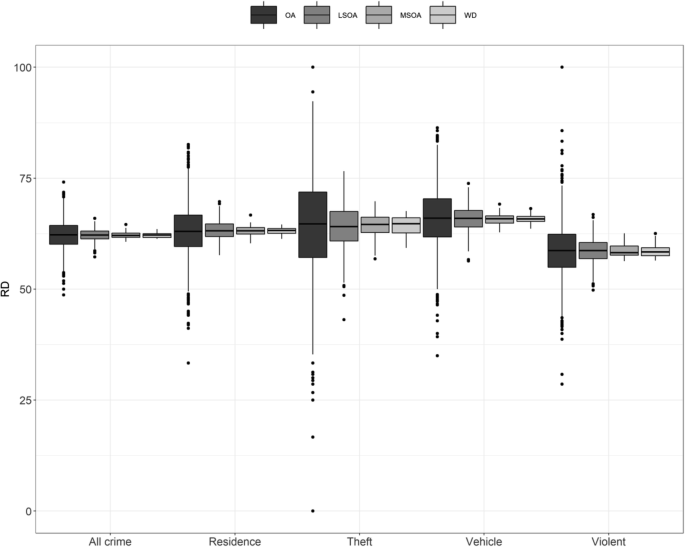

Police-recorded crimes are used by police forces to document community differences in crime and design spatially targeted strategies. Nevertheless, crimes known to police are affected by selection biases driven by underreporting. This paper presents a simulation study to analyze if crime statistics aggregated at small spatial scales are affected by larger bias than maps produced for larger geographies.

Based on parameters obtained from the UK Census, we simulate a synthetic population consistent with the characteristics of Manchester. Then, based on parameters derived from the Crime Survey for England and Wales, we simulate crimes suffered by individuals, and their likelihood to be known to police. This allows comparing the difference between all crimes and police-recorded incidents at different scales.

Measures of dispersion of the relative difference between all crimes and police-recorded crimes are larger when incidents are aggregated to small geographies. The percentage of crimes unknown to police varies widely across small areas, underestimating crime in certain places while overestimating it in others.

Conclusions

Micro-level crime analysis is affected by a larger risk of bias than crimes aggregated at larger scales. These results raise awareness about an important shortcoming of micro-level mapping, and further efforts are needed to improve crime estimates.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Impact of Measurement Error in Regression Models Using Police Recorded Crime Rates

Too Fine to be Good? Issues of Granularity, Uniformity and Error in Spatial Crime Analysis

More places than crimes: implications for evaluating the law of crime concentration at place.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Police-recorded crimes are the main source of information used by police forces and government agencies to analyze crime patterns, investigate the geographic concentration of crime, and design and evaluate spatially targeted policing strategies and crime prevention policies (Bowers and Johnson 2014 ; Weisburd and Lum 2005 ). Police statistics are also used by criminologists to develop theories of crime and deviance (Bruinsma and Johnson 2018 ). Nevertheless, crimes known to police are affected by selection biases driven by unequal crime reporting rates across social groups and geographical areas (Buil-Gil et al. 2021 ; Goudriaan et al. 2006 ; Hart and Rennison 2003 ; Xie 2014 ; Xie and Baumer 2019a ). The level of police control (e.g., police patrols, surveillance) also varies across areas, which may affect victims’ willingness to report crimes to police and dictate the likelihood that police officers witness incidents in some places more than others (McCandless et al. 2016 ; Schnebly 2008 ). The sources of measurement error that affect the bias and precision of crime statistics is an issue that merits scrutiny, since it affects policing practices, criminal justice policies, and citizens’ daily lives. Yet, it is an understudied issue.

The implications of crime data biases for documenting and explaining community differences in crime and guiding policing operational decision-making processes are mostly unknown (Brantingham 2018 ; Gibson and Kim 2008 ; Kirkpatrick 2017 ). Moreover, police analyses and crime mapping are moving toward using increasingly fine-grained geographic units of analysis, such as street segments and micro-places containing highly homogeneous communities (Groff et al. 2010 ; Weisburd et al. 2009 , 2012 ). Geographic crime analysis based on police-recorded crime and calls for service data is used to identify the micro-places where crime is most prevalent in order to effectively target police resource (Braga et al. 2018 ). In this context, we define “micro-places” as very detailed spatial units of analysis such as addresses, street segments, or clusters of such units (Weisburd et al. 2009 ). Despite the increasing interest in small units of analysis, the extent to which such aggregations impact on the overall accuracy of statistical outputs and spatial analyses remains unknown (Ramos et al. 2020 ). In other words, we do not know whether aggregating crime data at such detailed levels of analysis increases the impact of biases introduced by underreporting. This article presents a simulation study to analyze the impact of data biases on geographic crime analysis conducted at different spatial scales. The open question that this research aims to address is whether aggregating crimes at smaller, more socially homogeneous spatial scales increases the risk of obtaining biased outputs compared with aggregating crimes at larger, more socially heterogeneous geographical levels.