An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Mass Media and Marketing Communication Promoting Primary and Secondary Cancer Prevention

Peggy a. hannon.

University of Washington

Gareth P. Lloyd

University College London

K. Viswanath

Harvard University

Tenbroeck Smith

American Cancer Society

Karen Basen-Engquist

University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center

Sally W. Vernon

University of Texas Houston School of Public Health

Gina Turner

Mount Sinai School of Medicine

Bradford W. Hesse

National Cancer Institute

Corinne Crammer

Christian von wagner, cathy l. backinger.

People often seek and receive cancer information from mass media (including television, radio, print media, and the Internet), and marketing strategies often inform cancer information needs assessment, message development, and channel selection. In this article, we present the discussion of a 2-hour working group convened for a cancer communications workshop held at the 2008 Society of Behavioral Medicine meeting in San Diego, CA. During the session, an interdisciplinary group of investigators discussed the current state of the science for mass media and marketing communication promoting primary and secondary cancer prevention. We discussed current research, new research areas, methodologies and theories needed to move the field forward, and critical areas and disciplines for future research.

This paper summarizes a discussion about mass media and marketing approaches to cancer prevention and control held by attendees of the Society of Behavioral Medicine (SBM) Cancer Special Interest Group session at the 2008 SBM annual meeting. We discussed current research in this area, new research areas, needed methodologies and theories to move the field forward, and critical areas and disciplines for future research. In our discussion, we defined mass media broadly, to include television, radio, print, and the internet. We discussed marketing mainly in terms of marketing methods and tools, such as audience research, segmentation of the target audience, and the marketing mix (product, price, place, and promotion; Kotler & Lee, 2008 ).

Mass media can be used to influence policy, and can help set the cancer prevention and control agenda as well as motivate individual behavior change. A sufficient number of simple, straightforward cancer prevention and early detection messages are needed to ensure adequate exposure to achieve these goals ( Hornik, 2002 ). Unfortunately, primary and secondary cancer prevention and control receive little attention in the mass media compared with stories about people who already have cancer ( Stryker, Emmons, & Viswanath, 2007 ). When cancer prevention and screening are discussed in print media, the stories rarely include skill-building or resource information to help readers act on the information given (Moriarty & Stryker, 2007). Finally, conflicting information in the media about risk factors for cancer and benefits of screening makes it difficult for the public to know what to believe and which behaviors to enact ( Russell, 1999 ). Cancer is a complex topic that may be addressed in the context of other issues including tobacco, nutrition, physical activity, early detection and treatment. Additionally, cancer information competes with news about other health topics, non-health topics, entertainment, and advertising.

Given the complexity of cancer and the potential for competing information, some assessment of the information environment in which a given media campaign will be fielded is critical for determining message content and adequate exposure. What is the public’s attitude and emotional response to the messages in the campaign? What are the competing messages? Message theories and audience pre-testing of messages are underutilized, yet these approaches can help us create effective messages for broad audiences as well as culturally appropriate messages for more specific target audiences ( Randolph & Viswanath, 2004 ). Social marketing approaches, particularly audience research and considering all four “p’s” in the marketing mix (product, place, price, and promotion) can be especially useful in creating messages and campaigns that are responsive to the audience’s needs ( Kotler & Lee, 2008 ).

The internet and “eHealth” is experiencing rapid growth as a channel to deliver cancer prevention and control information and interventions. The emergence of the internet and the increasing array of mass media channels have made it increasingly difficult to draw traditional distinctions between mass media and interpersonal communication ( Abroms & Maibach, 2008 ), circumstances that create new challenges in choosing appropriate theories, methods, and evaluation designs. Of particular concern is the “digital divide:” lack of internet access, or lack of high-speed internet access, among several different groups in the population, including the elderly, those with low income or education, and those with limited health literacy or English proficiency ( Glasgow, 2007 ). Although internet access is becoming more common in some of these groups ( Carroll, Rivara, Ebel, Zimmerman, & Christakis, 2005 ), the majority of health information on the internet is written beyond the average reading level of U.S. adults and is therefore inaccessible to many people with internet access ( Viswanath & Kreuter, 2007 ).

There is increasing information each day about prevention and early detection of cancer, and there are innovative technologies (e.g., the internet, text messaging) to convey this information to the public. Unfortunately, there has not been a parallel increase in the efforts to reach underserved populations with messages they find relevant, or via channels they have access to. As we discussed this issue, we agreed there is a moral imperative for future cancer communications work to reach the underserved with relevant, comprehensive, and comprehensible cancer information. In the remainder of this paper, and with this imperative as a focus, we discuss examples of new areas of active investigation, key needs to advance the field, and critical areas and disciplines for future research.

New Research Areas

The National Cancer Institute has created several initiatives in the past 10 years that have supported exciting new areas of cancer communications research, including the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS), the Centers for Excellence in Cancer Communications Research, and Research Diffusion and Dissemination. Here, we present examples of recent advances in research that identified cancer prevention and control information needs, informed message development, and aided channel selection.

Identifying Cancer Prevention and Control Information Needs

Learning about underserved populations is a critical step toward identifying both appropriate messages and appropriate channels for people in this target audience. The HINTS was developed to monitor Americans’ use of cancer-related information from media and non-media sources ( http://hints.cancer.gov/about.jsp ). Several published reports using HINTS data highlighted important issues and gaps in the information available to the public about cancer prevention and control. For example, of the 45% of HINTS respondents who reported searching for cancer information, many were frustrated by the search process and concerned about the quality of information they found. Respondents lacking health insurance or a high-school education reported the most confusion in their search for cancer information ( Arora et al., 2007 ).

An analysis of HINTS respondents who had not actively sought cancer information revealed that nonseekers tended to be older and/or of lower socioeconomic status than information seekers. Nonseekers reported more trust in their providers as sources of health information than seekers, and less trust in health information provided by other sources ( Ramanadhan & Viswanath, 2006 ). HINTS has also documented knowledge gaps about common risk factors such as smoking and sun exposure among higher and lower SES groups ( Viswanath et al., 2006 ). New reports and publications based on HINTS data continue to be generated, and are valuable resources for cancer prevention researchers.

Message Development

Once the target audience has been identified and characterized, it is important to develop media and marketing interventions with messages that resonate with the target audience. There is a growing body of evidence testing different methods of framing health information presented in cancer prevention and control media messages. In the area of tobacco control, a comparison of gain and loss-framed messages found that loss-framed messages featuring decaying teeth were more effective in lowering adolescents’ intentions to smoke; of interest here is not only that the loss-frame was more effective, but the health threat (decaying teeth) was appearance-related rather than the usual lung cancer message ( Goodall & Appiah, 2008 ). Perhaps the price of decreasing physical attractiveness from smoking was more meaningful to this adolescent target audience than the threat of cancer. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of fear-based messages has provided a framework of conditions under which fear appeals are most effective ( Witte & Allen, 2000 ), but more work is needed to increase our understanding of the conditions under which other promotion tactics (e.g., humor, arousing empathy, etc.) are effective.

One promotion tactic is to incorporate narratives (e.g., stories with connected events and characters that include implicit or explicit cancer-relevant messages) into media messages (Kreuter et al., 2007). Much of the research about narrative communication has focused on topic areas other than health or cancer; therefore, an exciting new area of research is whether narrative approaches are more effective in engaging and motivating people than more traditional non-narrative approaches for cancer information. If so, narratives could become a powerful tool with which to relay cancer information, especially as they lend themselves well to mass media channels and could be more effective than traditional didactic messages in helping people understand cancer information and overcoming resistance to cancer prevention and screening behaviors (Kreuter et al., 2007).

Audience research can be a useful tool to determine what types of narratives will resonate with the target audience. In an effort to create an educational televised cancer news series that would appeal to an inner-city African-American community, Marks and colleagues conducted focus groups with members of their target audience to learn about their current understanding of cancer and what types of information and presentation styles were desired ( Marks, Reed, Colby, & Ibrahim, 2004 ). The focus group findings informed the development of a cancer news series broadcast via a local public television station. The stories in the news series reflected focus group participants’ values and concerns. African Americans were portrayed positively (as both patients and physicians) in stories that conveyed hopeful messages about detecting and treating cancer. This approach – audience involvement in message development prior to creating the new series (rather than filming the series and then pre-testing it) – increased the odds that the intervention was responsive to the audience’s core needs and values.

Channel Selection

Once an effective intervention has been created, finding the right channel and/or setting where the intervention will reach the target audience at the right time is crucial. A recent study compared seven different community settings (which included beauty salons, churches, neighborhood health centers, laundromats, social service agencies, health fairs, and public libraries) as sites for breast cancer education kiosks with touch screens. These kiosks were for low-income women who had never received breast cancer screening or were off-schedule; kiosks provided tailored, printed magazines about breast cancer, mammography, where to get a mammogram, and overcoming barriers to screening. The kiosks were equipped to track how many women used them, and how many of the users “fit” the target audience. Of the seven types of sites tested the kiosks placed in laundromats received the most frequent use by women in the target audience ( Kreuter, Alcaraz, Pfeiffer, & Christopher, 2008 ). This is one of the few cancer communication studies we’re aware of that specifically tested which places were most effective to reach the right people (in this case, women who need mammograms) at the right time (when they have time available to use the kiosk and read the magazines). Researchers creating interventions for cancer prevention and control could conduct similar studies comparing various channels and settings to determine maximal reach to the target audience.

Key Methodologies and Theories Needed to Advance the Field

Methodologies.

Relatively weak research designs (such as one-time post-intervention surveys) are frequently used to evaluate media interventions ( Noar, 2006 ). The randomized controlled trial (RCT) has long been considered the “gold standard” of evidence that a given intervention is effective, but there is increasing debate over whether this is the best research design for population-level health interventions ( Sanson-Fisher, Bonevski, Green, & D’este, 2007 ). Interrupted time series designs, longitudinal surveys, and other designs that enable us to assess exposure to media campaigns, changes in social norms, and sustainability of message effects are alternative approaches ( Mercer, DeVinney, Fine, Green, & Dougherty, 2007 ) that may be particularly well-suited to media interventions. The field would benefit greatly from consensus among researchers about the range of appropriate evaluation designs for media interventions.

Health literacy and media literacy are gaining currency as important predictors of people’s ability to comprehend and act on cancer prevention and control information. Systematic reviews of interventions to improve health and media literacy have yielded mixed findings; the small number of completed studies, heterogeneity of outcomes measured, and differing definitions and measures of health and media literacy make determining the efficacy of such interventions difficult ( Bergsma & Carney, 2008 ; Pignone, DeWalt, Sheridan, Berkman, & Lohr, 2005 ). Better definition of the core concepts and skills that make one health and media literate, and consensus on which measures to use, are needed in order for researchers to design and test cancer prevention and control messages accessible to underserved populations.

Most mass media and marketing campaigns target the “end user” – the individual who will receive, understand, and act on our message. Mass media and marketing approaches can also be used to address higher levels in the socioecologic model ( McLeroy, Bibeau, Steckler, & Glanz, 1988 ). The ability to examine individual effects and then recognize implications across other levels in the model (interpersonal, organization, community, and policy) was elucidated in Michael Marmot’s (2005) work on social inequalities, and can easily be applied to mass media and marketing in cancer prevention and control. This approach could lead to theories and research testing whether and how mass media messages affect interpersonal communications among social networks and the broader community ( Noar, 2006 ). This approach could also generate theories of how mass media and marketing interventions can be designed to change social norms and activate social groups that will attempt to make policy-level changes ( Abroms & Maibach, 2008 ; Gladwell, 2002 ). Media approaches using social marketing principles could also be directed towards policy-makers, other decision makers, health care delivery systems, employers, and entities with the capacity to reach and influence large numbers of individuals.

Many of the theories that currently inform message design for cancer communication do not address the fact that cancer prevention and control media messages often have powerful competitors sending counter-messages. In addition to the “usual suspect” constructs in health behavior change theories, such as barriers, lack of self-efficacy, and lack of knowledge or awareness, mass media and marketing campaign developers need to be aware of competing messages and behaviors when designing campaigns and interventions. The tobacco industry, which advertises and markets a product that accounts for 30% of cancer deaths, is the most obvious example of counter-messages. What have we learned from the “truth” campaign and other successful tobacco control media efforts about combating counter-messages that we can apply to other areas, such as improving diet and physical activity? Better integration of theories across different levels of the socioecologic model will equip us to design media and marketing campaigns that address not only lack of awareness, barriers, and self-efficacy problems, but also motivate people to act healthfully in spite of a social context with messages which often encourage the opposite.

Critical Areas & Disciplines for Future Research

Media interventions can effectively promote cancer-preventing lifestyle changes and screening tests that detect cancer early ( Viswanath, 2005 ). Our challenge now is to create and disseminate cancer prevention and control information that is equally accessible and usable for everyone. Unless we actively tackle the issue of health disparities in our future research, current inequalities will only be exacerbated by media and marketing efforts that use channels that fail to reach diverse populations, language that is not comprehensible to groups with low health literacy, or messages that are culturally inappropriate ( Viswanath, 2005 ). Interdisciplinary collaboration will be needed to address all of these issues successfully.

Scientists from disciplines such as communication sciences, biomedical professions, and public health are already engaged in using mass media and marketing to disseminate cancer information. Commercial marketers have expertise in encouraging people to buy new products and have valuable insights to share with health and social marketers about encouraging people to “buy” new behaviors. Several other disciplines with expertise relevant to media and marketing cancer prevention and control interventions include anthropology, cognitive and social psychology, health journalism, information systems, opinion polling, policy research, and social network analysis.

Increased collaboration among researchers from these disciplines would advance the science of mass media and marketing interventions promoting primary and secondary cancer prevention. Ideally, these collaborative efforts could build new bridges to reach those experiencing cancer-related health disparities. We must recognize that much more than cancer information needs to be communicated; mass media and marketing campaigns and interventions targeting underserved groups must also build trust, create meaningful dialogue, and promote useful resources in order to address and eliminate cancer-related health disparities.

Contributor Information

Peggy A. Hannon, University of Washington.

Gareth P. Lloyd, University College London.

K. Viswanath, Harvard University.

Tenbroeck Smith, American Cancer Society.

Karen Basen-Engquist, University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center.

Sally W. Vernon, University of Texas Houston School of Public Health.

Gina Turner, Mount Sinai School of Medicine.

Bradford W. Hesse, National Cancer Institute.

Corinne Crammer, American Cancer Society.

Christian von Wagner, University College London.

Cathy L. Backinger, National Cancer Institute.

- Abroms LC, & Maibach EW (2008). The effectiveness of mass communication to change public behavior . Annual Review of Public Health , 29 , 219–34. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Arora NK, Hesse BW, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, Clayman ML, & Croyle RT (2007). Frustrated and confused: The American public rates its cancer-related information-seeking experiences . Journal of General Internal Medicine , 23 , 223–228. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bergsma LJ, & Carney ME (2008). Effectiveness of health-promoting media literacy education: A systematic review . Health Education Research , 23 , 522–542. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carroll AE, Rivara FP, Ebel B, Zimmerman FJ, & Christakis DA (2005). Household computer and Internet access: The digital divide in a pediatric clinic population . AMIA 2005 Symposium Proceedings, 111–115. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gladwell M (2002). The tipping point: How little things can make a big difference . Boston, MA: Back Bay Publishing Co. [ Google Scholar ]

- Glasgow RE (2007). eHealth evaluation and dissemination research . American Journal of Preventive Medicine , 32 , 5S , S119–S126. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Goodall C, & Appiah O (2008). Adolescents’ perceptions of Canadian cigarette package warning labels: Investigating the effects of message framing . Health Communication , 23 , 117–127. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hornik R (2002). Public health communication: Evidence for behavior change . New York: Lawrence Erlbaum. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kotler P, & Lee NR (2008). Social marketing: Influencing behaviors for good . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kreuter MW, Alcaraz KI, Pfeiffer D, Christopher K (2008). Using dissemination research to identify optimal community settings for tailored breast cancer information kiosks . Journal of Public Health Management & Practice , 14 , 160–169. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Marks JP, Reed W, Colby K, & Ibrahim SA (2004). A culturally competent approach to cancer news and education in an inner city community: Focus group findings . Journal of Health Communication , 9 , 143–157. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Marmot M (2005). The status syndrome: How social standing affects our health and longevity . New York, NY: Henry Holt & Company. [ Google Scholar ]

- McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K (1988). An ecological perspective on health promotion programs . Health Education Quarterly , 15 , 351–377. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mercer SL, DeVinney BJ, Fine LJ, Green LW, & Dougherty D (2007). Study designs for effectiveness and translation research: Identifying trade-offs . American Journal of Preventive Medicine , 33 , 139–154. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Moriarty CM, & Strycker JE (2008). Prevention and screening efficacy messages in newspaper accounts of cancer . Health Education Research , 23 , 487–98. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Noar SM (2006). A 10-year retrospective of research in health mass media campaigns: where to we go from here? Journal of Health Communication , 11 , 21–42. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pignone M, DeWalt DA, Sheridan S, Berkman N, & Lohr KN (2005). Interventions to improve health outcomes for patients with low literacy: A systematic review . Journal of General Internal Medicine , 20 , 185–192. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ramanadhan S & Viswanath K (2006). Health and the information nonseeker: A profile . Health Communication , 20 , 131–139. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Randolph W, & Viswanath K (2004). Lessons learned from public health mass media campaigns: Marketing health in a crowded media world . Annual Reviews in Public Health , 25 , 419–437. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Russell C (1999). Living can be hazardous to your health: How the news media cover cancer risks . Journal of the National Cancer Institute Monographs , 25 , 167–70. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sanson-Fisher RW, Bonevski B, Green LW, & D’Este C (2007). Limitations of the randomized controlled trial in evaluation population-based health interventions . American Journal of Preventive Medicine , 33 , 155–161. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stryker JE, Emmons KM, Viswanath K (2007). Uncovering differences across the cancer control continuum: A comparison of ethnic and mainstream cancer newspaper stories . Preventive Medicine , 44 , 20–25. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Viswanath K (2005). The communications revolution and cancer control . Nature Reviews: Cancer , 5 , 828–835. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Viswanath K, Breen N, Meissner H, Moser RP, Hesse B, Steele WR, et al. (2006). Cancer knowledge and disparities in the information age . Journal of Health Communication , 11 Suppl 1 , 1–17. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Viswanath K, & Kreuter MW (2007). Health disparities, communication inequalities, and eHealth . American Journal of Preventive Medicine , 32 Suppl 5 , S131–133. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Witte K, & Allen M (2000). A meta-analysis of fear appeals: Implications for effective public health campaigns . Health Education & Behavior , 27 , 591–615. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

Salesforce is closed for new business in your area.

McKinsey Global Private Markets Review 2024: Private markets in a slower era

At a glance, macroeconomic challenges continued.

McKinsey Global Private Markets Review 2024: Private markets: A slower era

If 2022 was a tale of two halves, with robust fundraising and deal activity in the first six months followed by a slowdown in the second half, then 2023 might be considered a tale of one whole. Macroeconomic headwinds persisted throughout the year, with rising financing costs, and an uncertain growth outlook taking a toll on private markets. Full-year fundraising continued to decline from 2021’s lofty peak, weighed down by the “denominator effect” that persisted in part due to a less active deal market. Managers largely held onto assets to avoid selling in a lower-multiple environment, fueling an activity-dampening cycle in which distribution-starved limited partners (LPs) reined in new commitments.

About the authors

This article is a summary of a larger report, available as a PDF, that is a collaborative effort by Fredrik Dahlqvist , Alastair Green , Paul Maia, Alexandra Nee , David Quigley , Aditya Sanghvi , Connor Mangan, John Spivey, Rahel Schneider, and Brian Vickery , representing views from McKinsey’s Private Equity & Principal Investors Practice.

Performance in most private asset classes remained below historical averages for a second consecutive year. Decade-long tailwinds from low and falling interest rates and consistently expanding multiples seem to be things of the past. As private market managers look to boost performance in this new era of investing, a deeper focus on revenue growth and margin expansion will be needed now more than ever.

Perspectives on a slower era in private markets

Global fundraising contracted.

Fundraising fell 22 percent across private market asset classes globally to just over $1 trillion, as of year-end reported data—the lowest total since 2017. Fundraising in North America, a rare bright spot in 2022, declined in line with global totals, while in Europe, fundraising proved most resilient, falling just 3 percent. In Asia, fundraising fell precipitously and now sits 72 percent below the region’s 2018 peak.

Despite difficult fundraising conditions, headwinds did not affect all strategies or managers equally. Private equity (PE) buyout strategies posted their best fundraising year ever, and larger managers and vehicles also fared well, continuing the prior year’s trend toward greater fundraising concentration.

The numerator effect persisted

Despite a marked recovery in the denominator—the 1,000 largest US retirement funds grew 7 percent in the year ending September 2023, after falling 14 percent the prior year, for example 1 “U.S. retirement plans recover half of 2022 losses amid no-show recession,” Pensions and Investments , February 12, 2024. —many LPs remain overexposed to private markets relative to their target allocations. LPs started 2023 overweight: according to analysis from CEM Benchmarking, average allocations across PE, infrastructure, and real estate were at or above target allocations as of the beginning of the year. And the numerator grew throughout the year, as a lack of exits and rebounding valuations drove net asset values (NAVs) higher. While not all LPs strictly follow asset allocation targets, our analysis in partnership with global private markets firm StepStone Group suggests that an overallocation of just one percentage point can reduce planned commitments by as much as 10 to 12 percent per year for five years or more.

Despite these headwinds, recent surveys indicate that LPs remain broadly committed to private markets. In fact, the majority plan to maintain or increase allocations over the medium to long term.

Investors fled to known names and larger funds

Fundraising concentration reached its highest level in over a decade, as investors continued to shift new commitments in favor of the largest fund managers. The 25 most successful fundraisers collected 41 percent of aggregate commitments to closed-end funds (with the top five managers accounting for nearly half that total). Closed-end fundraising totals may understate the extent of concentration in the industry overall, as the largest managers also tend to be more successful in raising non-institutional capital.

While the largest funds grew even larger—the largest vehicles on record were raised in buyout, real estate, infrastructure, and private debt in 2023—smaller and newer funds struggled. Fewer than 1,700 funds of less than $1 billion were closed during the year, half as many as closed in 2022 and the fewest of any year since 2012. New manager formation also fell to the lowest level since 2012, with just 651 new firms launched in 2023.

Whether recent fundraising concentration and a spate of M&A activity signals the beginning of oft-rumored consolidation in the private markets remains uncertain, as a similar pattern developed in each of the last two fundraising downturns before giving way to renewed entrepreneurialism among general partners (GPs) and commitment diversification among LPs. Compared with how things played out in the last two downturns, perhaps this movie really is different, or perhaps we’re watching a trilogy reusing a familiar plotline.

Dry powder inventory spiked (again)

Private markets assets under management totaled $13.1 trillion as of June 30, 2023, and have grown nearly 20 percent per annum since 2018. Dry powder reserves—the amount of capital committed but not yet deployed—increased to $3.7 trillion, marking the ninth consecutive year of growth. Dry powder inventory—the amount of capital available to GPs expressed as a multiple of annual deployment—increased for the second consecutive year in PE, as new commitments continued to outpace deal activity. Inventory sat at 1.6 years in 2023, up markedly from the 0.9 years recorded at the end of 2021 but still within the historical range. NAV grew as well, largely driven by the reluctance of managers to exit positions and crystallize returns in a depressed multiple environment.

Private equity strategies diverged

Buyout and venture capital, the two largest PE sub-asset classes, charted wildly different courses over the past 18 months. Buyout notched its highest fundraising year ever in 2023, and its performance improved, with funds posting a (still paltry) 5 percent net internal rate of return through September 30. And although buyout deal volumes declined by 19 percent, 2023 was still the third-most-active year on record. In contrast, venture capital (VC) fundraising declined by nearly 60 percent, equaling its lowest total since 2015, and deal volume fell by 36 percent to the lowest level since 2019. VC funds returned –3 percent through September, posting negative returns for seven consecutive quarters. VC was the fastest-growing—as well as the highest-performing—PE strategy by a significant margin from 2010 to 2022, but investors appear to be reevaluating their approach in the current environment.

Private equity entry multiples contracted

PE buyout entry multiples declined by roughly one turn from 11.9 to 11.0 times EBITDA, slightly outpacing the decline in public market multiples (down from 12.1 to 11.3 times EBITDA), through the first nine months of 2023. For nearly a decade leading up to 2022, managers consistently sold assets into a higher-multiple environment than that in which they had bought those assets, providing a substantial performance tailwind for the industry. Nowhere has this been truer than in technology. After experiencing more than eight turns of multiple expansion from 2009 to 2021 (the most of any sector), technology multiples have declined by nearly three turns in the past two years, 50 percent more than in any other sector. Overall, roughly two-thirds of the total return for buyout deals that were entered in 2010 or later and exited in 2021 or before can be attributed to market multiple expansion and leverage. Now, with falling multiples and higher financing costs, revenue growth and margin expansion are taking center stage for GPs.

Real estate receded

Demand uncertainty, slowing rent growth, and elevated financing costs drove cap rates higher and made price discovery challenging, all of which weighed on deal volume, fundraising, and investment performance. Global closed-end fundraising declined 34 percent year over year, and funds returned −4 percent in the first nine months of the year, losing money for the first time since the 2007–08 global financial crisis. Capital shifted away from core and core-plus strategies as investors sought liquidity via redemptions in open-end vehicles, from which net outflows reached their highest level in at least two decades. Opportunistic strategies benefited from this shift, with investors focusing on capital appreciation over income generation in a market where alternative sources of yield have grown more attractive. Rising interest rates widened bid–ask spreads and impaired deal volume across food groups, including in what were formerly hot sectors: multifamily and industrial.

Private debt pays dividends

Debt again proved to be the most resilient private asset class against a turbulent market backdrop. Fundraising declined just 13 percent, largely driven by lower commitments to direct lending strategies, for which a slower PE deal environment has made capital deployment challenging. The asset class also posted the highest returns among all private asset classes through September 30. Many private debt securities are tied to floating rates, which enhance returns in a rising-rate environment. Thus far, managers appear to have successfully navigated the rising incidence of default and distress exhibited across the broader leveraged-lending market. Although direct lending deal volume declined from 2022, private lenders financed an all-time high 59 percent of leveraged buyout transactions last year and are now expanding into additional strategies to drive the next era of growth.

Infrastructure took a detour

After several years of robust growth and strong performance, infrastructure and natural resources fundraising declined by 53 percent to the lowest total since 2013. Supply-side timing is partially to blame: five of the seven largest infrastructure managers closed a flagship vehicle in 2021 or 2022, and none of those five held a final close last year. As in real estate, investors shied away from core and core-plus investments in a higher-yield environment. Yet there are reasons to believe infrastructure’s growth will bounce back. Limited partners (LPs) surveyed by McKinsey remain bullish on their deployment to the asset class, and at least a dozen vehicles targeting more than $10 billion were actively fundraising as of the end of 2023. Multiple recent acquisitions of large infrastructure GPs by global multi-asset-class managers also indicate marketwide conviction in the asset class’s potential.

Private markets still have work to do on diversity

Private markets firms are slowly improving their representation of females (up two percentage points over the prior year) and ethnic and racial minorities (up one percentage point). On some diversity metrics, including entry-level representation of women, private markets now compare favorably with corporate America. Yet broad-based parity remains elusive and too slow in the making. Ethnic, racial, and gender imbalances are particularly stark across more influential investing roles and senior positions. In fact, McKinsey’s research reveals that at the current pace, it would take several decades for private markets firms to reach gender parity at senior levels. Increasing representation across all levels will require managers to take fresh approaches to hiring, retention, and promotion.

Artificial intelligence generating excitement

The transformative potential of generative AI was perhaps 2023’s hottest topic (beyond Taylor Swift). Private markets players are excited about the potential for the technology to optimize their approach to thesis generation, deal sourcing, investment due diligence, and portfolio performance, among other areas. While the technology is still nascent and few GPs can boast scaled implementations, pilot programs are already in flight across the industry, particularly within portfolio companies. Adoption seems nearly certain to accelerate throughout 2024.

Private markets in a slower era

If private markets investors entered 2023 hoping for a return to the heady days of 2021, they likely left the year disappointed. Many of the headwinds that emerged in the latter half of 2022 persisted throughout the year, pressuring fundraising, dealmaking, and performance. Inflation moderated somewhat over the course of the year but remained stubbornly elevated by recent historical standards. Interest rates started high and rose higher, increasing the cost of financing. A reinvigorated public equity market recovered most of 2022’s losses but did little to resolve the valuation uncertainty private market investors have faced for the past 18 months.

Within private markets, the denominator effect remained in play, despite the public market recovery, as the numerator continued to expand. An activity-dampening cycle emerged: higher cost of capital and lower multiples limited the ability or willingness of general partners (GPs) to exit positions; fewer exits, coupled with continuing capital calls, pushed LP allocations higher, thereby limiting their ability or willingness to make new commitments. These conditions weighed on managers’ ability to fundraise. Based on data reported as of year-end 2023, private markets fundraising fell 22 percent from the prior year to just over $1 trillion, the largest such drop since 2009 (Exhibit 1).

The impact of the fundraising environment was not felt equally among GPs. Continuing a trend that emerged in 2022, and consistent with prior downturns in fundraising, LPs favored larger vehicles and the scaled GPs that typically manage them. Smaller and newer managers struggled, and the number of sub–$1 billion vehicles and new firm launches each declined to its lowest level in more than a decade.

Despite the decline in fundraising, private markets assets under management (AUM) continued to grow, increasing 12 percent to $13.1 trillion as of June 30, 2023. 2023 fundraising was still the sixth-highest annual haul on record, pushing dry powder higher, while the slowdown in deal making limited distributions.

Investment performance across private market asset classes fell short of historical averages. Private equity (PE) got back in the black but generated the lowest annual performance in the past 15 years, excluding 2022. Closed-end real estate produced negative returns for the first time since 2009, as capitalization (cap) rates expanded across sectors and rent growth dissipated in formerly hot sectors, including multifamily and industrial. The performance of infrastructure funds was less than half of its long-term average and even further below the double-digit returns generated in 2021 and 2022. Private debt was the standout performer (if there was one), outperforming all other private asset classes and illustrating the asset class’s countercyclical appeal.

Private equity down but not out

Higher financing costs, lower multiples, and an uncertain macroeconomic environment created a challenging backdrop for private equity managers in 2023. Fundraising declined for the second year in a row, falling 15 percent to $649 billion, as LPs grappled with the denominator effect and a slowdown in distributions. Managers were on the fundraising trail longer to raise this capital: funds that closed in 2023 were open for a record-high average of 20.1 months, notably longer than 18.7 months in 2022 and 14.1 months in 2018. VC and growth equity strategies led the decline, dropping to their lowest level of cumulative capital raised since 2015. Fundraising in Asia fell for the fourth year of the last five, with the greatest decline in China.

Despite the difficult fundraising context, a subset of strategies and managers prevailed. Buyout managers collectively had their best fundraising year on record, raising more than $400 billion. Fundraising in Europe surged by more than 50 percent, resulting in the region’s biggest haul ever. The largest managers raised an outsized share of the total for a second consecutive year, making 2023 the most concentrated fundraising year of the last decade (Exhibit 2).

Despite the drop in aggregate fundraising, PE assets under management increased 8 percent to $8.2 trillion. Only a small part of this growth was performance driven: PE funds produced a net IRR of just 2.5 percent through September 30, 2023. Buyouts and growth equity generated positive returns, while VC lost money. PE performance, dating back to the beginning of 2022, remains negative, highlighting the difficulty of generating attractive investment returns in a higher interest rate and lower multiple environment. As PE managers devise value creation strategies to improve performance, their focus includes ensuring operating efficiency and profitability of their portfolio companies.

Deal activity volume and count fell sharply, by 21 percent and 24 percent, respectively, which continued the slower pace set in the second half of 2022. Sponsors largely opted to hold assets longer rather than lock in underwhelming returns. While higher financing costs and valuation mismatches weighed on overall deal activity, certain types of M&A gained share. Add-on deals, for example, accounted for a record 46 percent of total buyout deal volume last year.

Real estate recedes

For real estate, 2023 was a year of transition, characterized by a litany of new and familiar challenges. Pandemic-driven demand issues continued, while elevated financing costs, expanding cap rates, and valuation uncertainty weighed on commercial real estate deal volumes, fundraising, and investment performance.

Managers faced one of the toughest fundraising environments in many years. Global closed-end fundraising declined 34 percent to $125 billion. While fundraising challenges were widespread, they were not ubiquitous across strategies. Dollars continued to shift to large, multi-asset class platforms, with the top five managers accounting for 37 percent of aggregate closed-end real estate fundraising. In April, the largest real estate fund ever raised closed on a record $30 billion.

Capital shifted away from core and core-plus strategies as investors sought liquidity through redemptions in open-end vehicles and reduced gross contributions to the lowest level since 2009. Opportunistic strategies benefited from this shift, as investors turned their attention toward capital appreciation over income generation in a market where alternative sources of yield have grown more attractive.

In the United States, for instance, open-end funds, as represented by the National Council of Real Estate Investment Fiduciaries Fund Index—Open-End Equity (NFI-OE), recorded $13 billion in net outflows in 2023, reversing the trend of positive net inflows throughout the 2010s. The negative flows mainly reflected $9 billion in core outflows, with core-plus funds accounting for the remaining outflows, which reversed a 20-year run of net inflows.

As a result, the NAV in US open-end funds fell roughly 16 percent year over year. Meanwhile, global assets under management in closed-end funds reached a new peak of $1.7 trillion as of June 2023, growing 14 percent between June 2022 and June 2023.

Real estate underperformed historical averages in 2023, as previously high-performing multifamily and industrial sectors joined office in producing negative returns caused by slowing demand growth and cap rate expansion. Closed-end funds generated a pooled net IRR of −3.5 percent in the first nine months of 2023, losing money for the first time since the global financial crisis. The lone bright spot among major sectors was hospitality, which—thanks to a rush of postpandemic travel—returned 10.3 percent in 2023. 2 Based on NCREIFs NPI index. Hotels represent 1 percent of total properties in the index. As a whole, the average pooled lifetime net IRRs for closed-end real estate funds from 2011–20 vintages remained around historical levels (9.8 percent).

Global deal volume declined 47 percent in 2023 to reach a ten-year low of $650 billion, driven by widening bid–ask spreads amid valuation uncertainty and higher costs of financing (Exhibit 3). 3 CBRE, Real Capital Analytics Deal flow in the office sector remained depressed, partly as a result of continued uncertainty in the demand for space in a hybrid working world.

During a turbulent year for private markets, private debt was a relative bright spot, topping private markets asset classes in terms of fundraising growth, AUM growth, and performance.

Fundraising for private debt declined just 13 percent year over year, nearly ten percentage points less than the private markets overall. Despite the decline in fundraising, AUM surged 27 percent to $1.7 trillion. And private debt posted the highest investment returns of any private asset class through the first three quarters of 2023.

Private debt’s risk/return characteristics are well suited to the current environment. With interest rates at their highest in more than a decade, current yields in the asset class have grown more attractive on both an absolute and relative basis, particularly if higher rates sustain and put downward pressure on equity returns (Exhibit 4). The built-in security derived from debt’s privileged position in the capital structure, moreover, appeals to investors that are wary of market volatility and valuation uncertainty.

Direct lending continued to be the largest strategy in 2023, with fundraising for the mostly-senior-debt strategy accounting for almost half of the asset class’s total haul (despite declining from the previous year). Separately, mezzanine debt fundraising hit a new high, thanks to the closings of three of the largest funds ever raised in the strategy.

Over the longer term, growth in private debt has largely been driven by institutional investors rotating out of traditional fixed income in favor of private alternatives. Despite this growth in commitments, LPs remain underweight in this asset class relative to their targets. In fact, the allocation gap has only grown wider in recent years, a sharp contrast to other private asset classes, for which LPs’ current allocations exceed their targets on average. According to data from CEM Benchmarking, the private debt allocation gap now stands at 1.4 percent, which means that, in aggregate, investors must commit hundreds of billions in net new capital to the asset class just to reach current targets.

Private debt was not completely immune to the macroeconomic conditions last year, however. Fundraising declined for the second consecutive year and now sits 23 percent below 2021’s peak. Furthermore, though private lenders took share in 2023 from other capital sources, overall deal volumes also declined for the second year in a row. The drop was largely driven by a less active PE deal environment: private debt is predominantly used to finance PE-backed companies, though managers are increasingly diversifying their origination capabilities to include a broad new range of companies and asset types.

Infrastructure and natural resources take a detour

For infrastructure and natural resources fundraising, 2023 was an exceptionally challenging year. Aggregate capital raised declined 53 percent year over year to $82 billion, the lowest annual total since 2013. The size of the drop is particularly surprising in light of infrastructure’s recent momentum. The asset class had set fundraising records in four of the previous five years, and infrastructure is often considered an attractive investment in uncertain markets.

While there is little doubt that the broader fundraising headwinds discussed elsewhere in this report affected infrastructure and natural resources fundraising last year, dynamics specific to the asset class were at play as well. One issue was supply-side timing: nine of the ten largest infrastructure GPs did not close a flagship fund in 2023. Second was the migration of investor dollars away from core and core-plus investments, which have historically accounted for the bulk of infrastructure fundraising, in a higher rate environment.

The asset class had some notable bright spots last year. Fundraising for higher-returning opportunistic strategies more than doubled the prior year’s total (Exhibit 5). AUM grew 18 percent, reaching a new high of $1.5 trillion. Infrastructure funds returned a net IRR of 3.4 percent in 2023; this was below historical averages but still the second-best return among private asset classes. And as was the case in other asset classes, investors concentrated commitments in larger funds and managers in 2023, including in the largest infrastructure fund ever raised.

The outlook for the asset class, moreover, remains positive. Funds targeting a record amount of capital were in the market at year-end, providing a robust foundation for fundraising in 2024 and 2025. A recent spate of infrastructure GP acquisitions signal multi-asset managers’ long-term conviction in the asset class, despite short-term headwinds. Global megatrends like decarbonization and digitization, as well as revolutions in energy and mobility, have spurred new infrastructure investment opportunities around the world, particularly for value-oriented investors that are willing to take on more risk.

Private markets make measured progress in DEI

Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) has become an important part of the fundraising, talent, and investing landscape for private market participants. Encouragingly, incremental progress has been made in recent years, including more diverse talent being brought to entry-level positions, investing roles, and investment committees. The scope of DEI metrics provided to institutional investors during fundraising has also increased in recent years: more than half of PE firms now provide data across investing teams, portfolio company boards, and portfolio company management (versus investment team data only). 4 “ The state of diversity in global private markets: 2023 ,” McKinsey, August 22, 2023.

In 2023, McKinsey surveyed 66 global private markets firms that collectively employ more than 60,000 people for the second annual State of diversity in global private markets report. 5 “ The state of diversity in global private markets: 2023 ,” McKinsey, August 22, 2023. The research offers insight into the representation of women and ethnic and racial minorities in private investing as of year-end 2022. In this chapter, we discuss where the numbers stand and how firms can bring a more diverse set of perspectives to the table.

The statistics indicate signs of modest advancement. Overall representation of women in private markets increased two percentage points to 35 percent, and ethnic and racial minorities increased one percentage point to 30 percent (Exhibit 6). Entry-level positions have nearly reached gender parity, with female representation at 48 percent. The share of women holding C-suite roles globally increased 3 percentage points, while the share of people from ethnic and racial minorities in investment committees increased 9 percentage points. There is growing evidence that external hiring is gradually helping close the diversity gap, especially at senior levels. For example, 33 percent of external hires at the managing director level were ethnic or racial minorities, higher than their existing representation level (19 percent).

Yet, the scope of the challenge remains substantial. Women and minorities continue to be underrepresented in senior positions and investing roles. They also experience uneven rates of progress due to lower promotion and higher attrition rates, particularly at smaller firms. Firms are also navigating an increasingly polarized workplace today, with additional scrutiny and a growing number of lawsuits against corporate diversity and inclusion programs, particularly in the US, which threatens to impact the industry’s pace of progress.

Fredrik Dahlqvist is a senior partner in McKinsey’s Stockholm office; Alastair Green is a senior partner in the Washington, DC, office, where Paul Maia and Alexandra Nee are partners; David Quigley is a senior partner in the New York office, where Connor Mangan is an associate partner and Aditya Sanghvi is a senior partner; Rahel Schneider is an associate partner in the Bay Area office; John Spivey is a partner in the Charlotte office; and Brian Vickery is a partner in the Boston office.

The authors wish to thank Jonathan Christy, Louis Dufau, Vaibhav Gujral, Graham Healy-Day, Laura Johnson, Ryan Luby, Tripp Norton, Alastair Rami, Henri Torbey, and Alex Wolkomir for their contributions

The authors would also like to thank CEM Benchmarking and the StepStone Group for their partnership in this year's report.

This article was edited by Arshiya Khullar, an editor in the Gurugram office.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

CEO alpha: A new approach to generating private equity outperformance

Private equity turns to resiliency strategies for software investments

The state of diversity in global private markets: 2022

Can You Erase the Mark of a Criminal Record? Labor Market Impacts of Criminal Record Remediation

Many have pointed to criminal records as a substantial barrier to employment that could exacerbate racial inequality in the United States. Recent research from UChicago economists shows that retroactively reducing felony convictions to misdemeanors does not, on average, change employment. In this paper, the authors test the possibility that policies that clear entire records—rather than simply reducing their severity— might improve defendants’ labor market outcomes.

To answer this question, the authors first examine defendants’ employment trajectories before and after they encounter the criminal legal system. The authors link criminal records from four jurisdictions (Maryland, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Bexar County, Texas) to tax data from the Internal Revenue Service, and show the following:

- There are large and persistent drops in employment at the time of both misdemeanor and felony charges. These patterns are observed for convictions and, perhaps more surprisingly, for non-convictions.

- A survey of firm hiring decision-makers supports the interpretation that these patterns at least partially reflect the negative impact of having a record. Hiring professionals report markedly reduced likelihood of hiring someone with a drug or theft charge, even if it resulted in a non-conviction.

The authors next study whether removing criminal records can reverse these patterns. They measure the impacts of three policies that limit the information about criminal history reported in employment background checks: the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA), which prohibits reporting of criminal charges that did not lead to a conviction (mainly dismissals) after seven years for jobs that pay less than $75,000 a year; the Maryland Credit Reporting Law, which prohibits the reporting of convictions after seven years for jobs that pay less than $20,000 a year; and Pennsylvania’s Clean Slate Law of 2018, which legislated automated sealing of all non-convictions.

The authors detail their methodology for measuring the impact of each policy in their working paper ; in sum, they use administrative tax records to compare individuals who had their records cleared to otherwise-comparable defendants. The authors find similar results across the three policies and jurisdictions that they study:

- There is little evidence that clearing criminal records from background checks (or removing non-convictions, in the case of the FCRA) improves labor market outcomes, on average.

- A notable exception is evidence that record remediation policies increase the rate of electronically mediated gig platform work, albeit from a very low base.

How is it possible that criminal records are associated with large drops in employment and that remediation policies aren’t effective at mitigating this harm? The authors hypothesize that criminal charges scar defendants’ labor market trajectories in a way that can be difficult to undo later, for instance by creating resume gaps, loss of experience, discouragement, and reduced search. Since there are fewer barriers to participating in platform gig work, the authors posit such work is less susceptible to scarring.

Importantly, criminal record remediation policies may have benefits that are not reflected in the earnings observed in tax records. Remediation of records could directly impact access to housing, civic engagement, quality of life, and other policy-relevant outcomes. At the same time, this research suggests that if reintegration and labor market participation are primary objectives, existing policies are not achieving these goals. These results may help explain why recent evaluations of Ban-the-Box policies failed to find improvements in labor market outcomes for individuals with records.

Return to Office and the Tenure Distribution

Homelessness and the Persistence of Deprivation: Income, Employment, and Safety Net Participation

The Adoption of ChatGPT

- Share full article

For more audio journalism and storytelling, download New York Times Audio , a new iOS app available for news subscribers.

- May 24, 2024 • 25:18 Whales Have an Alphabet

- May 23, 2024 • 34:24 I.C.C. Prosecutor Requests Warrants for Israeli and Hamas Leaders

- May 22, 2024 • 23:20 Biden’s Open War on Hidden Fees

- May 21, 2024 • 24:14 The Crypto Comeback

- May 20, 2024 • 31:51 Was the 401(k) a Mistake?

- May 19, 2024 • 33:23 The Sunday Read: ‘Why Did This Guy Put a Song About Me on Spotify?’

- May 17, 2024 • 51:10 The Campus Protesters Explain Themselves

- May 16, 2024 • 30:47 The Make-or-Break Testimony of Michael Cohen

- May 15, 2024 • 27:03 The Possible Collapse of the U.S. Home Insurance System

- May 14, 2024 • 35:20 Voters Want Change. In Our Poll, They See It in Trump.

- May 13, 2024 • 27:46 How Biden Adopted Trump’s Trade War With China

- May 10, 2024 • 27:42 Stormy Daniels Takes the Stand

I.C.C. Prosecutor Requests Warrants for Israeli and Hamas Leaders

The move sets up a possible showdown between the international court and israel with its biggest ally, the united states..

Hosted by Sabrina Tavernise

Featuring Patrick Kingsley

Produced by Will Reid , Diana Nguyen and Shannon M. Lin

Edited by Liz O. Baylen and Michael Benoist

Original music by Elisheba Ittoop

Engineered by Chris Wood

Listen and follow The Daily Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | YouTube

This week, Karim Khan, the top prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, requested arrest warrants for Israel’s prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, and the country’s defense minister, Yoav Gallant.

Patrick Kingsley, the Times’s bureau chief in Jerusalem, explains why this may set up a possible showdown between the court and Israel with its biggest ally, the United States.

On today’s episode

Patrick Kingsley , the Jerusalem bureau chief for The New York Times.

Background reading

Why did a prosecutor go public with the arrest warrant requests ?

The warrant request appeared to shore up domestic support for Mr. Netanyahu.

There are a lot of ways to listen to The Daily. Here’s how.

We aim to make transcripts available the next workday after an episode’s publication. You can find them at the top of the page.

The Daily is made by Rachel Quester, Lynsea Garrison, Clare Toeniskoetter, Paige Cowett, Michael Simon Johnson, Brad Fisher, Chris Wood, Jessica Cheung, Stella Tan, Alexandra Leigh Young, Lisa Chow, Eric Krupke, Marc Georges, Luke Vander Ploeg, M.J. Davis Lin, Dan Powell, Sydney Harper, Mike Benoist, Liz O. Baylen, Asthaa Chaturvedi, Rachelle Bonja, Diana Nguyen, Marion Lozano, Corey Schreppel, Rob Szypko, Elisheba Ittoop, Mooj Zadie, Patricia Willens, Rowan Niemisto, Jody Becker, Rikki Novetsky, John Ketchum, Nina Feldman, Will Reid, Carlos Prieto, Ben Calhoun, Susan Lee, Lexie Diao, Mary Wilson, Alex Stern, Dan Farrell, Sophia Lanman, Shannon Lin, Diane Wong, Devon Taylor, Alyssa Moxley, Summer Thomad, Olivia Natt, Daniel Ramirez and Brendan Klinkenberg.

Our theme music is by Jim Brunberg and Ben Landsverk of Wonderly. Special thanks to Sam Dolnick, Paula Szuchman, Lisa Tobin, Larissa Anderson, Julia Simon, Sofia Milan, Mahima Chablani, Elizabeth Davis-Moorer, Jeffrey Miranda, Renan Borelli, Maddy Masiello, Isabella Anderson and Nina Lassam.

Patrick Kingsley is The Times’s Jerusalem bureau chief, leading coverage of Israel, Gaza and the West Bank. More about Patrick Kingsley

Advertisement

Profiling consumers who reported mass marketing scams: demographic characteristics and emotional sentiments associated with victimization

- Original Article

- Open access

- Published: 28 September 2023

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Marguerite DeLiema ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9807-5910 1 &

- Paul Witt 2

1487 Accesses

2 Citations

Explore all metrics

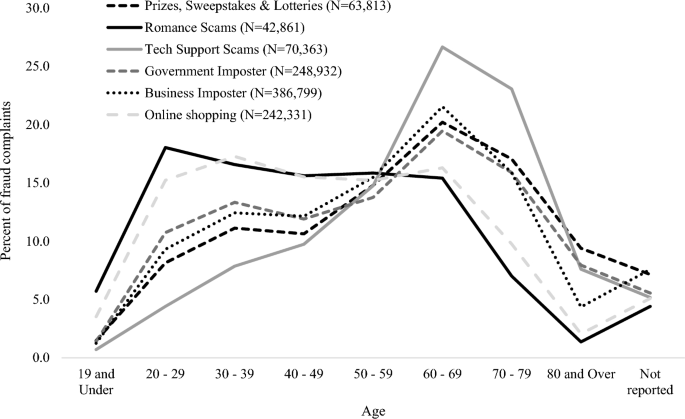

We examine the characteristics of consumers who reported scams to the U.S. Federal Trade Commission. We assess how consumers vary demographically across six scam types, and how the overall emotional sentiment of a consumer’s complaint (positive, negative, neutral/mixed) relates to reporting victimization versus attempted fraud (no losses). For romance, tech support, and prize, sweepstakes, and lottery scams, more older than young and middle-aged adults reported victimization. Across all scam types, consumers classified as Black, Hispanic, and Asian/Asian Pacific Islander were more likely than non-Hispanic white consumers to report victimization than attempted fraud. Relative to complaints categorized as emotionally neutral or mixed, we find that emotionally positive complaints and emotionally negative complaints were significantly associated with victimization, but that these relationships differed by scam type. This study helps identify which consumer groups are affected by specific scams and the association between emotion and victimization.

Similar content being viewed by others

A Comprehensive Overview of Consumer Conflicts on Social Media

Is There a Scam for Everyone? Psychologically Profiling Cyberscam Victims

Consumer Bullying in Online Brand Communities—Quantifying a Dark Social Media Phenomenon

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mass marketing scams are a form of financial fraud in which perpetrators use mass communication technologies such as robocalls, phishing emails, social media, text messages, and other low-cost methods to target and exploit thousands of consumers, often overseas. Mass marketing scams typically incorporate social engineering tactics that involve “trickery, persuasion, impersonation, emotional manipulation, and abuse of trust to gain information or computer-system access” (Thompson 2006 , p. 1).

There is significant variation in the types and prevalence of mass marketing scams, which change over time in response to new communication and money transfer methods, changes in culture and purchasing habits, and national and global events such as the Covid-19 pandemic (Whittaker et al. 2022 ). Consumer complaints of mass marketing scams received by the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) increased substantially throughout the Covid-19 pandemic, reaching a peak of 2.8 million in 2021 (FTC 2022a ), and then declining to 2.4 million in 2022 (FTC 2023 ). Several of the most common mass marketing scams reported in 2022 were imposter scams (~ 726,000 complaints), online shopping scams (327,000 complaints), prize, sweepstakes, and lottery scams (~ 143,000 complaints), and fake business and job opportunities (~ 92,700 complaints) (FTC 2023 ). The majority of these complaints involve attempted fraud where the consumer was exposed to a scam but was not victimized—i.e., no financial losses were reported. The consumer may have immediately recognized that the solicitation was fraudulent or became suspicious before sending money, or someone intervened before losses occurred. In the remaining 26% of complaints, consumers reported victimization and median losses were $650 per complaint (FTC 2023 ).

In the present study, we use consumer fraud complaints to the FTC ( N = 1,010,748) to assess the demographic correlates of victimization versus attempted fraud for six types of mass marketing scams: romance; tech support; prize, sweepstakes, lottery; government imposter; business imposter; and online shopping. We also use sentiment analysis to categorize the emotional valence of each complaint narrative as either positive, negative, or neutral/mixed, and determine how emotional valence relates to reports of victimization by different types of scams. In the following sections, we first review literature on the extent of underreporting by both victims and non-victims. Next we present literature on the demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of victims, showing that characteristics such as age, sex, race, income, and education vary across scam type. Last we identify studies that demonstrate a connection between emotion and fraud victimization. We describe how emotional arousal affects financial decision making, and how fraud negatively impacts victims’ emotional well-being.

Underreporting

Underreporting, both to law enforcement and in surveys, presents a challenge for researchers and consumer protection agencies seeking to identify vulnerable consumers for targeted outreach and awareness. Using data from three mass marketing fraud prevalence studies administered in 2005, 2011, and 2017, Anderson ( 2021 ) found that only 4.8% percent of U.S. fraud victims complained to a government agency or the Better Business Bureau. Raval ( 2020 ) compared victim information taken from fraud cases against nine mass marking scams to FTC consumer complaint data on those same scams. For scams that involved low-dollar losses (average loss of $40–90 per victim), as few as 1 in ~ 2,500 victims submitted a complaint. The complaint rate was closer to 1 in 10 victims for scams that involved significantly higher dollar losses (Raval 2020 , Table 1 , p. 171). This indicates that financial losses motivate reporting behavior. In another analysis of consumer complaint behavior, Raval ( 2021 ) found demographic differences in reporting, such that consumers situated in heavily minority areas were less likely to complain than those in predominantly white areas.

Underreporting issues also extend to survey research on fraud victimization. In 2003, researchers with AARP administered a survey to known victims of fraud and found that 50% of lottery scam victims and 77% of investment fraud victims did not report investing or paying money in any of the relevant questions about investment fraud or a lottery scam (AARP 2003).

Victims may not report to law enforcement, survey researchers, and consumer protection agencies for reasons such as self-blame, shame, embarrassment, and the stigma of victimization (Cross et al. 2016 ). Kemp ( 2022 ) recently found that the most common reason for not reporting was opportunity cost, including the time required for gathering evidence and contacting authorities. Another reason for not reporting is not considering the incident to be a crime (Kemp 2022 ), and feeling that there is little that authorities can do to hold perpetrators accountable (Cross 2020 ). Raval’s ( 2020 ) analysis indicates that lack of trust in authorities and lack of social capital may account for lower rates of fraud reporting among residents in predominantly minority communities compared to residents in predominantly white communities.

For every unreported case of fraud victimization, there are many more incidents of attempted fraud that consumers do not report. Attempted fraud is so ubiquitous that reporting every unwanted phone call, email, text message, mailed letter, or other scam solicitation would be tremendously burdensome. Illustrating the extraordinary frequency of mass marketing scams, a large market survey of more than 36,000 American adults showed that 45% received imposter scam text messages, emails, or calls every day, and another 24% were targeted each week (YouGov America 2023 ). Some consumers may assume that government agencies only address complaints that involve a financial loss. However, given that approximately three quarters of the fraud complaints in the FTC’s Consumer Sentinel Network involve no reported losses (FTC 2023), many people are still motivated to report attempted fraud.

Demographic characteristics of fraud reporters

A growing body of research seeks to understand consumer risk factors associated with mass marketing scam victimization, yet existing studies present a mixed and sometimes contradictory picture of which demographic and socioeconomic groups are most susceptible. One reason is that many fraud studies focus on a narrow subtype of mass marking scams—such as investment fraud or romance scams (e.g., Buchanan and Whitty 2014 ; Deliema et al. 2020 ), and risk factors do not necessarily generalize across the universe of consumer fraud. Another limitation of existing victim profiling research is that survey samples are typically small—between several hundred to a few thousand respondents. One notable exception is the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics’ (BJS) nationally representative fraud survey of 51,000 U.S. respondents that assessed the prevalence of victimization by seven fraud subtypes (Morgan 2021 ). Because overall rates of self-reported victimization were extremely low (1.25%), victim demographic profiles for specific mass marketing scams were not described in the report.

Random sample surveys that ask respondents to self-report fraud victimization typically find that young and middle-aged adults are more likely than older adults to report losing money in a scam (Anderson 2019 ). For scams overall, FTC’s consumer complaint data also indicate that older adults are the least likely of any age group to report a loss (compared to attempted fraud); however, their median losses are between 1.5 and three times greater than losses reported by younger adults (FTC 2022b ).

Looking at general fraud victimization obscures consumer age differences by scam type. For example, in a survey of law enforcement-identified fraud victims, Pak and Shadel ( 2011 ) found that lottery, sweepstakes, and prize scam victims were older than the general U.S. population aged 50 and older. Anderson ( 2019 ) found that survey participants aged 65 and older were more likely to self-report computer repair fraud (i.e., tech support scams) than young and middle-aged adults. Using victim information from 23 consumer protection law enforcement cases, Raval ( 2021 ) found that the victimization rate was 43% higher in zip codes with a median age of 55 compared to zip codes with a median age of 25. Studies that examine age-related declines in cognitive functioning suggest that older adults may be more susceptible to scams (Han et al. 2016a , 2016b ), yet these and other prior studies do not control for different rates of fraud exposure by age. Older adults, possibly due to higher rates of social isolation and greater wealth, may be targeted more than other age groups.

Prior research also suggests that risk factors such as income, education, and sex vary across scam types. For example, Whitty ( 2020 ) found that men and educated people were more likely to be deceived by cyberscams in general. DeLiema, Pak, and Shadel (2020) found that compared to general investors, investment fraud victims were more likely to be male. However, a recent study that examined investment fraud cases in Canada showed that 60% of the defrauded investors were female (Lokanan and Liu 2021 ). Using samples of independently identified victims, Pak and Shadel ( 2011 ) found that investment fraud victims were more likely to be male and to have higher education and income than the general population, whereas lottery scam victims were more likely to be female and have lower education and income compared to the general population.

Understanding which race/ethnic communities are affected by different forms of fraud is important for fraud prevention. Such research can inform whether fraud prevention messages should be presented in multiple languages or whether it should focus on specific scam subtypes more than others in particular communities. Broader crime victimization surveys find that Black and Hispanic individuals experience higher rates of serious criminal offenses compared to non-Hispanic (NH) white individuals (Morgan and Truman 2020 ). Similarly, in the 2017 fraud prevalence study conducted by BJS (Morgan 2021 ), a smaller percentage of white respondents were victims (1.19%) compared to respondents who were Black (1.67%) and respondents who were Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, American Indian or Alaska Native, or two or more races (2.19%). Raval ( 2021 ) found that victimization rates by payday loan and student debt relief frauds were substantially higher in majority Black communities. This may suggest that these scams disproportionality target economically disadvantaged communities.

For Hispanics, Raval ( 2021 ) found that victimization rates were slightly higher in moderately Hispanic communities compared to 0% Hispanic communities, and the victim rate was 14% lower in 100% Hispanic areas compared to 0% Hispanic areas. These results could indicate that ethnically homogenous communities provide a buffer against fraud; Hispanic community members may inform other network members about common scams affecting their community. However, it is also possible that the Raval ( 2021 ) sample of fraud cases did not include scams that most affect Hispanic individuals. For example, DeLiema and Witt ( 2021 ) found that both Black and Hispanic communities were more likely than majority NH white communities to report victimization (versus attempted fraud) by the Social Security Administration (SSA) imposter scam. This could suggest these groups are less familiar with the SSA’s roles and norms for interacting with U.S. consumers.

Taken together, prior research findings indicate that victim demographic profiles vary by scam type, perhaps due to differences in fraud exposure or other factors that make some groups more susceptible to certain types of persuasion messages than others. These differences speak to the importance of analyzing victim risk profiles separately for different types of mass marketing scams.

Emotion and fraud victimization

Demographic characteristics alone do not explain differences in rates of fraud victimization among consumers. “In the moment” persuasion tactics affect decision making and play a role in victimization. An important “in the moment” factor is the degree to which the scam solicitation message elicits strong emotional arousal. Fraud perpetrators use visceral factors, including moods, emotions and drive states that have a direct hedonic impact, to manipulate decision making (Loewenstein 1996 ). Government imposter and tech support scams incorporate fear-based messaging to make the target feel a sense of urgency and insecurity, whereas other scams—like prize, sweepstakes, and lottery scams—use positive appeals to make the target feel excited in anticipation of a and reward.