An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Wiley - PMC COVID-19 Collection

A literature review of the economics of COVID‐19

Abel brodeur.

1 Department of Economics, University of Ottawa, Ottawa Ontario, Canada

Suraiya Bhuiyan

Associated data.

Table B: COVID‐19 ‐ Timeline

Figure A: Cumulative COVID‐19 Cases and Deaths – Global Pandemic (as on 30 November 2020)

Table C: Cumulative Cases: Top 10 Countries (as of 30 November 2020)

The goal of this piece is to survey the developing and rapidly growing literature on the economic consequences of COVID‐19 and the governmental responses, and to synthetize the insights emerging from a very large number of studies. This survey: (i) provides an overview of the data sets and the techniques employed to measure social distancing and COVID‐19 cases and deaths; (ii) reviews the literature on the determinants of compliance with and the effectiveness of social distancing; (iii) mentions the macroeconomic and financial impacts including the modelling of plausible mechanisms; (iv) summarizes the literature on the socioeconomic consequences of COVID‐19, focusing on those aspects related to labor, health, gender, discrimination, and the environment; and (v) summarizes the literature on public policy responses.

1. INTRODUCTION

The World was gripped by a pandemic over the first half of 2020, of which the second wave emerged in the Fall. It was identified as a new coronavirus (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, or SARS‐CoV‐2), and later renamed as Coronavirus Disease‐19 or COVID‐19 (Qiu et al., 2020 ). While COVID‐19 originated in the city of Wuhan in the Hubei province of China, it has spread rapidly across the World, resulting in a human tragedy and in tremendous economic damage. By the end of November 2020, there had been close to 63 million reported cases of COVID‐19 globally and over 1.4 million deaths.

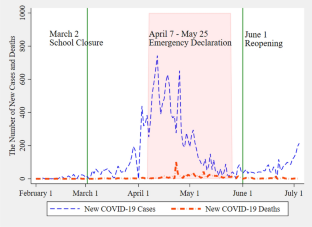

Pandemics are anything but new, and they have had severe, adverse economic impacts in the past; COVID‐19 is not expected to be any different (see the Online Appendix for a brief history of past pandemics and their socioeconomic consequences). Given the rapid spread of COVID‐19, countries across the World have adopted several public health measures intended to prevent its spread, including social distancing (Fong et al., 2020 ). According to Mandavilli ( 2020 ), this strategy saved thousands of lives, both during other pandemics, such as the Spanish flu of 1918, and more recently a flu outbreak that occurred in Mexico City in 2009. As part of social distancing measures, businesses, schools, community centers, and nongovernmental organization (NGOs) were required to close down, mass gatherings have been prohibited, and lockdown measures have been imposed in many countries, allowing travel only for essential needs. 1 The goal of these measures is to facilitate a “flattening the curve,” that is, a reduction in the number of new daily cases of COVID‐19 in order to halt their exponential growth and, hence, reduce pressure on medical services (John Hopkins University, 2020 ).

The spread of COVID‐19 has resulted in a considerable slowdown in economic activities. According to an early forecast of The World Bank ( 2020 ), global GDP in 2020 relative to 2019 is forecasted to fall by 5.2%. Similarly, the OECD ( 2020 ) forecasts a fall in global GDP by 6 to 7.6%, depending on whether or not a second wave of COVID‐19 emerges. In its latest forecast, the International Monetary Fund ( 2020 ) projected a contraction of 4.4% in light of the stronger than expected recoveries in advanced economies which lifted lockdowns during May and June of 2020. This was mainly the result of the unprecedented fiscal, monetary, and regulatory responses in these countries that helped to maintain household disposable income, protect cash flows for firms, and support credit provisions.

The economic implications will be wide ranging and uncertain, with different effects expected on labor markets, production supply chains, financial markets, and GDP levels. The negative effects may vary by the stringency of the social distancing measures (e.g., lockdowns and related restrictions), their length of implementation, and the degree of compliance with them. In addition, the pandemic and the subsequent interventions may well lead to higher levels of mental health distress, increased economic inequality, and particularly harsh effects on certain socio‐demographic groups.

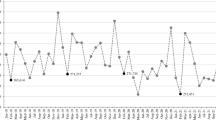

The goal of this piece is to survey the emerging and already vast literature on the economic consequences of COVID‐19, and to synthesize the insights contained in a growing number of studies. Figure 1 illustrates the number of National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) working articles that have been released related to the pandemic between March and November of 2020. 2 By the end of November 2020, there had been 247 articles related to COVID‐19. Similarly, 204 discussion articles on the pandemic were released by the IZA Institute of Labor Economics (IZA) from March to November of 2020. 3

COVID‐19 publications in 2020 in the NBER working paper series. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com ]

Source : Authors’ compilation drawn from the NBER website

This article will focus on five broad areas: (i) the measurement of the spread of COVID‐19 and social distancing activities, (ii) the effectiveness and compliance with social distancing regulations, (iii) the economic impacts of COVID‐19 and the mechanisms giving rise to them, (iv) the socioeconomic consequences of lockdowns, and (v) the policy measures and regulations that have been implemented in response to the pandemic. One topic that we do not cover explicitly is the interface between COVID‐19 and financial markets. This omission is due partly to space constraints, but also to the fact that the outcomes in financial markets that are related to COVID‐19 are extremely volatile, and therefore, any analysis contained in our survey would be ephemeral.

The rest of the article is structured as follows. Section 2 provides an outline of the measurement of COVID‐19 spread and of social distancing actions by documenting and describing the most popular data sources. Section 3 discusses the socioeconomic determinants and the effectiveness of social distancing activities. Section 4 focuses on the economic and financial impacts including modelling of the plausible behavioral mechanisms. Section 5 reviews the literature on the socioeconomic consequences of social distancing measures, focusing on the labor‐related, health‐related, gender‐related, discriminatory, and environmental aspects. Section 6 consists of a summary of the economic impact of the policy responses. Section 7 provides the conclusion.

2. MEASUREMENT OF COVID‐19 AND SOCIAL DISTANCING ACTIONS

2.1. measurement of covid‐19 spread.

Before reviewing the potential economic impact and socioeconomic consequences, it is important to contextualize the data related to COVID‐19, without which it would not be possible to assess the scope of the pandemic. Timely and reliable data inform us of how and where the disease is spreading, what impact the pandemic has on the lives of people around the World, and to what extent the counter measures that are taken are successful (Roser et al., 2020 ).

Four key indicators are: (i) the total number of tests carried out, (ii) the number of confirmed COVID‐19 cases, (iii) the number of confirmed COVID‐19 deaths, and (iv) the number of people who have recovered from COVID‐19. These numbers are provided by different local, regional, and national health agencies/ministries across countries. However, for research and educational purposes, the data are accumulated by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering at Johns Hopkins University. 4 The database provides the figures as well as visual maps of the distribution of cases across the World. They are reported at the provincial level for China, at the city level for the United States of America, Australia, and Canada, and at the country level for all other countries (Dong et al., 2020 ). The data are corroborated with the WHO, 5 the Center for Disease Control (CDC) in the United States, and the European Center for Disease Control (ECDC).

Based on these figures, the Case Fatality Rate (CFR) is calculated as the number of confirmed deaths divided by the number of confirmed cases, which gives the mortality rate. 6 However, Roser et al. ( 2020 ) caution against taking the CFR numbers at face value to assess mortality risks, 7 because the CFR is based on the number of confirmed cases. Due to limited and sporadic testing capacities, not all COVID‐19 cases can be confirmed. Moreover, the CFR reflects the incidence of the disease in a particular context at a particular point in time. Therefore, CFRs are subject to changes over time and are sensitive to the location and population characteristics.

Recent studies indicate that there are large measurement errors associated with COVID‐19 case numbers. Using data on influenza‐like illnesses (ILI) from the CDC, Silverman et al. ( 2020 ) show that ILIs can be a useful predictor of COVID‐19 cases in the United States. The authors find that there was an escalation in the number of ILI patients during March of 2020. These cases could not be properly identified as COVID‐19 cases due to the lack of testing capabilities during the early stages of the pandemic's progression. The authors suggest that the surge in ILIs may have corresponded to 8.7 million new COVID‐19 cases between March 8 and March 28, most of which were probably not diagnosed. Based on imputation, that figure suggests that almost 80% of all actual cases in the United States during that time period were never diagnosed.

While the dataset mentioned above focuses on counts and tests, the COVID Tracking Project 8 in the United States provides additional data on patients who have been hospitalized, are in intensive care units (ICUs), and are on ventilator support for each of the 50 states. It also grades each state on data quality. Recently, it has included the COVID Racial Data Tracker , 9 which shows the race and the ethnicity of individuals affected by COVID‐19. All of these combined measures and statistics provide a more comprehensive perspective of the spread of the pandemic in the United States.

2.2. Measurement of social distancing

Compared to measuring the spread of the virus, social distancing is not easy to quantify. We determined from the literature that there are three main techniques that are employed: (i) developing and calculating measures of the mobility of the population, (ii) modelling proxies, and (iii) calculating indices. Proxies and indices are based on data related to the observed spread of infection and to the implementation of social distancing policies, respectively. On the other hand, the movements of people are based on their observed travelling patterns. Mobility measures have been used extensively in recent months to discern mobility patterns during the pandemic (Nguyen et al., 2020 ). However, mobility data providers have slight differences in their methodologies. Table 1 provides a summary of how different mobility data providers compile their data.

Social distancing— Mobility measures and how they work

Mobility data are more dynamic and are available at a daily frequency. They can also be used to measure the effect of social distancing on other variables, such as adherence to shelter‐in‐place policies or labor employment patterns (Gupta et al., 2020 ). They also offer key insights into human behavior. For example, “Safegraph” data suggest that social activity in the United States started declining substantially and rapidly well before lockdown measures were imposed (Farboodi et al., 2020 ).

Outside of the United States, a large number of studies have relied on Google LLC Community Mobility Reports. For China, mobility has been mostly measured using data from Baidu Inc. For example, Kraemer et al. ( 2020 ) document how COVID‐19 spread in China using Baidu Inc. data. They investigate travel history from Wuhan to other cities in China, finding that the spatial distribution of cases in other cities was correlated with individual peoples’ travel histories. However, after the implementation of social distancing measures in these cities, the correlation no longer held. Therefore, the authors conclude that local lockdowns rather than travel restrictions helped to mitigate the spread and transmission of COVID‐19 in cities outside Wuhan. See Coelho et al. ( 2020 ) for an examination of the spread of COVID‐19 in Brazil using daily air travel statistics from the Official Airline Guide to measure mobility.

Mobility data do have their own limitations and are not frequently used in the case of epidemics, even though they might be useful (Oliver et al., 2020 ). Mobility data are a proxy for time spent in different locations. They do not allow one to determine the situational context of the contacts that are reported, which are needed to understand the spread of COVID‐19, that is whether they occur in the workplace or in the general community (Martín‐Calvo et al., 2020 ). Those two situations involve different levels of the inherent risk of transmission. In regards to the productive activities of the individuals that are tracked, information on the context is also indeterminate. For those who are working virtually from their homes, for instance, these measures do not capture the value‐added stemming from the time that they allocate to their jobs in the labor market. It is also likely that the quality of these measures can deteriorate when overall unemployment rates and job disruptions are high (Gupta et al., 2020 ). 10 Telecom operator data are deemed to be more representative than locational data, as the former are not limited to people with smartphones, GPS locators, and histories of travel using GPS location (Lomas, 2020 ).

Social media has also been used to measure mobility patterns. Galeazzi et al. (2020) analyze the effect of lockdowns in France, Italy, and United Kingdom on national mobility patterns by exploiting geolocalized data observed from 13 million Facebook users. The authors predictably find that people transition toward localized, short‐ range mobility patterns instead of international, long‐range patterns. However, mobility patterns display heterogeneity across countries. In France and the United Kingdom, mobility is more “concentrated” around huge, central metropolises that are largely disconnected from the provinces, which helps to reduce transmission of the virus. In Italy, on the other hand, the population is more “distributed” across clusters around four major cities that remain interconnected, thus permitting persistent spread.

3. SOCIAL DISTANCING: DETERMINANTS, EFFECTIVENESS, AND COMPLIANCE

A large range of social distancing policies have been implemented, ranging from full‐scale lockdowns to voluntary self‐compliance measures. 11 For example, Sweden imposed relatively light restrictions (Juranek & Zoutman, 2020 ). Large‐scale events were prohibited, and restaurants and bars were restricted to table service only; however, private businesses were generally allowed to operate freely. The population was encouraged to stay at home if they were feeling unwell and to limit social interactions if possible (T.M. Andersen et al., 2020 bib18 ).

People tend to adopt social distancing practices when there is a specific incentive to do so in terms of risk to health and financial cost (Makris, 2020 ). Maloney and Taskin ( 2020 ) attribute voluntary, cooperative actions to either fear of infection or to a sense of social responsibility. Stringent social distancing measures tend to be implemented in countries with a greater proportion of elderly residents, a higher population density, a greater proportion of employees working in vulnerable occupations, higher degrees of democratic freedom, a higher incidence of international travel, and greater distances from the Equator (e.g., Jinjarak et al., 2020 ). Appealing to a game theoretic approach, Cui et al. ( 2020 ) argue that states sharing economic ties will be “tipped” to reach a Nash equilibrium, whereby all other states comply with shelter‐in‐place policies. 12

Social distancing policy determinants have been linked to political party characteristics, political beliefs, and partisan differences (Baccini & Brodeur, 2021 ; Barrios & Hochberg, forthcoming; Murray & Murray, 2020 ). Barrios and Hochberg (forthcoming) correlate the risk perception for contracting COVID‐19 with partisan differences. They find that, in the absence of the imposition of social distancing, counties in the United States which had higher vote shares for Donald Trump are less likely to engage in social distancing. This persists even when mandatory stay‐at‐home measures are implemented across states. Allcott et al. ( 2020 ) find a similar pattern. In addition, the authors show through surveys that Democratic and Republican supporters have different risk perceptions about contracting COVID‐19, and hence hold divergent views regarding the importance of following social distancing measures. These stylized facts make it hard to estimate the causal effect of COVID‐19 on electoral outcomes (Baccini et al., 2021 ).

Researchers are trying to determine the effectiveness of social distancing policies in reducing social interactions and ultimately infections and deaths. Abouk and Heydari ( 2021 ) show that reductions in outside‐the‐home social interactions in the United States are driven by a combination of governmental regulations and voluntary measures, with a strong causal impact for the implementation of statewide stay‐at‐home orders, but more moderate impacts for nonessential business closures and limitations placed on bars/restaurants. Ferguson et al. ( 2020 ) argue that multiple interventions are required in order to have a substantial desired impact on transmission. The optimal mitigation strategy, which is a combination of case isolations, home quarantining, and social distancing of high‐risk groups, would reduce the number of deaths by half and the demand for beds in ICUs by two‐thirds in the United Kingdom and the United States.

Some studies focus on the impact of social distancing on COVID‐19 cases, hospitalizations, etc. For example, Fang et al. ( 2020 ) argue that if lockdown policies had not been imposed in Wuhan, then the infection rates would have been 65% higher in cities outside of Wuhan. Hartl et al. ( 2020 ) show that growth rate of COVID‐19 cases in Germany dropped from 26.7 to 13.8% within 7 days after implementation of lockdowns in the country. Greenstone and Nigam ( 2020 ) project that 3 to 4 months of adherence to social distancing regulations would reduce the number of cases in the United States by 1.7 million by October of 2021, 630,000 of which would translate into averted overcrowding of ICUs in hospitals. Friedson et al. ( 2020 ) argue that early intervention in California helped to reduce significantly the numbers of COVID‐19 cases and deaths during the first 3 weeks following its enactment. Note that this set of interventions falls well short of an economic shutdown.

Similarly, Dave, Friedson, Matsuzawa, Sabia, et al. ( 2020 ) find that counties in Texas that adopted shelter‐in‐place orders earlier than the statewide shelter‐in‐place order experienced a 19 to 26% fall in the rates of COVID‐19 case growth 2 weeks after implementation of such orders. M. Andersen et al. ( 2020 ) find that temporary paid sick leave, a federal mandate enacted in the United States, which allowed private and public employees 2 weeks of paid leave, led to increased compliance with stay‐at‐home orders. On a more global scale, Hsiang et al. ( 2020 ) show that social distancing interventions prevented or delayed around 62 million confirmed cases, corresponding to the aversion of roughly 530 million total infections in China, South Korea, Italy, Iran, France, and the United States within 7 days.

Another important related issue is the determinants of compliance behavior (e.g., Coelho et al., 2020 ; Fan et al., 2020 ). The documented socioeconomic determinants of the degree of compliance with social distancing (lockdowns or safer‐at‐home orders) include, among other factors, income level, trust, and social capital, public discourse, and to some extent, news channel viewership. The degree of ethnic diversity is another documented socioeconomic determinant of social distancing (Egorov et al., 2021 ). Galasso et al. ( 2020 ) rely on survey data from eight OECD countries and provide evidence that women are more likely than men to agree with restrictive public policy measures and to comply with them. Chiou and Tucker ( 2020 ) show that Americans living in higher‐income regions with access to high‐speed internet are more likely to comply with social distancing directives. Coven and Gupta ( 2020 ) find that residents of low‐income neighborhoods in New York City comply less with shelter‐in‐place activities during non‐working hours. According to the authors, this pattern is consistent with the fact that low‐income populations are more likely to be front line, “essential” workers and are also are more likely to make frequent retail shopping visits for essentials, making for two compounded effects. People with lower income levels, less flexible work arrangements (e.g., the inability to work remotely), and a lack of accessible interior space outside of bedrooms are less likely to engage in social distancing (Papageorge et al., 2020 ). Last, Bonaccorsi et al. ( 2020 ) analyze the heterogeneous impacts of lockdowns by socioeconomic conditions of people in Italy. Using mobility data from Facebook, they provide evidence that mobility reduction is higher in municipalities which have stronger fiscal capacity and also those which have lower per‐capita income levels. The authors conclude that the pandemic has disproportionately affected poor individuals within municipalities with strong fiscal capacity in Italy.

Individual beliefs and social preferences should also be taken into consideration, as they affect behavior and compliance. Based on an experimental setup with participants in the United States and the United Kingdom, Akesson et al. ( 2020 ) conclude that individuals overestimated the infectiousness of COVID‐19 relative to expert suggestions. If they were exposed to expert opinion, individuals were prone to correct their beliefs. However, the more infectious COVID‐19 was deemed to be, the less likely they were to undertake social distancing measures. This was perhaps due to the belief that the individual will contract COVID‐19 regardless of his/her social distancing practices. Briscese et al. ( 2020 ) model the impact of “lockdown extension” on compliance using a representative sample of residents from Italy. The authors find that if a given hypothetical extension is shorter than expected (i.e., a positive surprise), the residents are more willing to engage in self‐isolation. Therefore, to ensure compliance, these authors suggest that it is imperative for the government or local authorities to work on communication and to manage peoples’ expectations. Campos‐Mercade et al. ( 2021 ) examine the relationship between social preferences and social distancing compliance. The authors find that people who exhibit prosocial behavior (in this instance individuals who claim that they do not want to expose others to risks) are more likely to follow social distancing measures and other health‐related guidelines.

Bargain and Aminjonov ( 2020 ) demonstrate that residents in European regions with high levels of trust decrease their mobility related to non‐necessary activities compared to regions with lower levels of trust. Brück et al. ( 2020 ) document a negative relationship between being in contact with sick people and trust in people and institutions. Similarly, Brodeur et al. ( 2020 ) find that counties in the United States exhibiting relatively more trust in others decrease their mobility significantly once a lockdown policy is implemented. They also provide evidence that the estimated effect on postlockdown compliance is especially large if people tend to place trust in the media, and relatively smaller if they tend to trust in science, medicine, or government.

Researchers also think about this chain of causality in reverse. Aksoy Eichengreen, and Saka ( 2020 ) find that individuals’ degrees of exposure to epidemics (especially during the ages 18 to 25) has a negative effect on their confidence in political institutions. These individuals are also less likely to have confidence in their health care systems during the times of pandemics. Barrios et al. ( 2021 ) and Durante et al. ( 2021 ) provide evidence that regions with stronger civic culture engaged in more voluntary social distancing. Aksoy, Ganslmeier, and Poutvaara ( 2020 ) find that a high level of public attention (measured through the share of Google shares containing matters related to COVID‐19) has a significant correlation with the timing of implementation of social distancing measures. This relationship is mostly applicable for countries with high quality of institutions. Last, Bartscher et al. ( 2020 ) show that higher levels of social capital (proxied through voter turnout in parliamentary elections) lead to fewer cases per capita accumulated from mid‐March to mid‐May in selected European countries and United Kingdom.

Daniele et al. ( 2020 ) investigate the effect of the COVID‐19 shock on sociopolitical attitudes as opposed to the impact of latter on the spread of the virus. Employing a randomized survey flow design for 8,000 respondents in Germany, Italy, Netherlands and Spain, the authors find that COVID‐19 has led to a deterioration in the levels of interpersonal and institutional trust. It has also lowered support for the European Union in general and for social welfare spending financed by taxes. The authors conclude that these results are driven by the “economic insecurity” rather than the “health” dimensions resulting from the crisis.

Simonov et al. ( 2020 ) analyze the causal effect of cable news viewership on social distancing compliance. The authors examine the average partial effect of Fox News viewership, a news channel that has mostly refuted expert recommendations from leaders of the United States and global public health communities on the severity of COVID‐19 and on compliance, and find that a 1 percentage point increase in Fox News viewership reduced the propensity to stay at home by 8.9 percentage points. Bursztyn et al. ( 2020 ) show that greater exposure to the Hannity show compared to the Tucker Carlson Tonight show in Fox News is associated with larger COVID‐19 case numbers and deaths. This is because the former TV host downplayed the importance of COVID‐19, while the latter provided a serious warning on the same topic during early February. The variation between the messages in the two shows led to changes in behavior in response to COVID‐19.

Table 2 provides a summary of the literature related to the determinants (i.e., factors which influence implementation of social distancing as a policy measure), compliance with social distancing (i.e., whether people are actually following social distancing measures), and their effectiveness (i.e., evidence of success in reducing COVID‐19 cases).

Determinants, compliance and effectiveness of social distancing measures: Summary of studies

4. MACROECONOMIC IMPACTS AND PLAUSIBLE MECHANISMS

4.1. plausible mechanisms for macroeconomic impact.

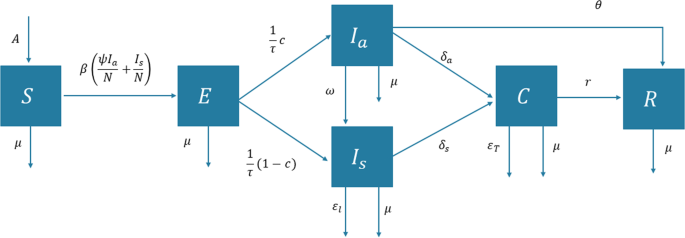

To understand the potential negative economic impact of COVID‐19, it is important to comprehend the economic transmission channels through which the shocks will adversely affect the economy. According to Carlsson‐Szlezak et al. ( 2020a , b ), there are three main transmission channels. The first is the direct impact, which is related to reduced consumption of goods and services. Prolonged lengths of the pandemic and the concomitant social distancing measures might reduce consumer confidence by keeping consumers at home, wary of discretionary spending, and pessimistic about their long‐term economic prospects. The second one is the indirect impact working through financial market shocks and their effects on the real economy. Household wealth will likely fall, savings will increase, and consumption spending will decrease further. The third consists of supply‐side disruptions; as restrictions halt or hamper production activities, they will negatively impact supply chains, labor demand, and employment, leading to prolonged periods of lay‐offs and rising unemployment. In particular, Baldwin ( 2020 ) discusses the expectation shock by which a “wait‐and‐see” attitude is adopted by economic agents. The author argues that this is common during economic climates characterized by uncertainties, as there is less confidence in markets and in engaging in economic transactions. Ultimately, the intensity of the shock is determined by the underlying epidemiological properties of the virus, consumer behaviour, and firm behavior in the face of adversity and uncertainty, and public policy responses. To understand the implications of the spread of the virus and the consequent social distancing measures on economic activities, a number of researchers have integrated canonical epidemiology models such as the susceptible, infected, resolved model (SIR) with macroeconomic models (see the Online Appendix for a detailed review of these models).

Gourinchas ( 2020 , p. 33) summarizes the effect on the economy by stating: “A modern economy is a complex web of interconnected parties: employees, firms, suppliers, consumers, and financial intermediaries. Everyone is someone else's employee, customer, lender, etc.” Due to the very high degrees of interconnectiveness and specialization of productive activities, a breakdown in the supply chains and the circular flows will have cascading effects. Baldwin ( 2020 ) describes the impact of COVID‐19 and subsequent social distancing measures on the macroeconomy within a circular flow framework.

It is also important to understand the processes that generate recoveries from economic crises. Carlsson‐Szlezak et al. ( 2020a ) explain different types of recovery in the aftermath of negative shocks through the concept of “shock geometry.” There are three broad scenarios of economic recoveries, which we mention in ascending order of their severity. First, there is the most optimistic one labelled “V‐shaped,” whereby aggregate output is displaced and quickly recovers to its pre‐crisis path. Second, there is the “U‐shaped” path, whereby output drops swiftly but does not return swiftly to its precrisis path. The gap between the former trajectory of output and the actual one remains large for quite some time, but recovery eventually occurs. Third, in the case of the very grim “L‐shaped” path, output drops and reaches a trough, but subsequent growth rates remain very low. The gap between the former and the new output paths continues to widen. Another scenario of economic recovery often mentioned is the “K‐shaped” one, which occurs when, following a recession, different parts of the economy recover at different rates, times, or magnitudes.

Carlsson‐Szlezak et al. ( 2020b ) state that after previous pandemics, such as the 1918 Spanish Influenza, the 1958 Asian Influenza, the 1968 Hong Kong influenza, and the 2002 SARS outbreak, economies have tended to experience “V‐shaped” recoveries. However, the pattern for the COVID‐19 economic recovery is not expected to be straightforward. This is because the effects on employment due to social distancing measures and lockdowns are expected to be much larger. According to Gourinchas ( 2020 ), during a short period, as much as 50% of the working population might not be able to find work. Moreover, even if no containment measures are implemented, a recession would occur anyway, fueled by the precautionary and/or risk‐averse behavior of households and firms faced with the uncertainty of dealing with a pandemic as well as with an inadequate public health response (Gourinchas, 2020 ).

Guerrieri et al. ( 2020 ) show that in a multisector model with certain assumptions, such as incomplete markets, low substitutability across sectors, and liquidity‐constrained consumers, COVID‐19 imparts a supply shock which works through lockdowns, layoffs, firm closures, etc. The subsequent impact would be a drop in aggregate demand and a demand‐deficient recession, that is, a “Keynesian supply shock.”

Baqaee and Farhi ( 2020 ) analyze the impact through a disaggregated Keynesian model comprised of multiple sectors, factors of production, and input‐output linkages with different features, such as nominal wage rigidities and credit constraints. They find that negative supply shocks are stagflationary, whereas negative demand shocks are deflationary. The policy implications are somewhat ambiguous. Policies that boost aggregate supply (e.g., providing subsidies to businesses, relaxing lockdowns, etc.) might not be effective in increasing demand in certain demand‐constrained sectors. Similarly, demand‐inducing policies (e.g., lower interest rates, more generous social insurance, etc.) might lead to supply shortages and inflationary pressures in certain sectors.

4.2. Quantitative macroeconomic impacts

As the pandemic unfolds, many researchers have been thinking about the economic impact from a historical perspective. Ludvigson et al. ( 2020 ) try to quantify the macroeconomic impact of costly disasters (natural and manmade) and translate them into estimates of the impact of COVID‐19. They find that in a fairly conservative scenario, pandemics, such as COVID‐19, are tantamount to large, multiple‐period exogenous shocks. Using a “costly disaster” index, the authors find that COVID‐19 is constituted of multi‐period shocks in the United States, which leads to a 12.75% drop in industrial production, a 17% loss in service employment, sustained and drastic reductions in air travel, and macroeconomic uncertainties which linger for up to 5 months. Jordà et al. ( 2020 ) analyze the rate of return on the real natural interest rate (the level of real returns on safe assets resulting from the demand and supply of investment capital in a noninflationary environment) from the 14 th century to 2018. Theoretically, a pandemic is supposed to induce a downward negative shock to the real natural interest rate. This is because investment demand decreases due to excess capital per labor unit (i.e., a scarcity of labor being utilized), while savings flows increase due to either precautionary reasons or to replace lost wealth. The authors find that the natural rate of interest may be about 2 percentage points lower than it would otherwise have been some 20 years after the pandemic, and only return to counterfactual levels after 40 years.

Analysis based on historical data, however, might not be relevant in this case. According to Baker et al. ( 2020 ), COVID‐19 has led to massive spikes in uncertainty, and there are no close historical parallels. Because of the speed of evolution and timely requirements of data, the authors suggest that one should utilize forward‐looking uncertainty measures to ascertain its impact on the economy. They formulate the uncertainty measure from the Standard & Poor's 500 Volatility Index (VIX) and the news‐based economic policy uncertainty (EPU) index developed by Baker et al. ( 2016 ). Using a real business cycle model, the authors find that a COVID‐19 shock leads to a year‐over‐year contraction of GDP by 11% in fourth quarter of 2020. According to the authors, more than half of the contraction is caused by COVID‐19‐induced uncertainty. Based on a similar approach, Altig et al. ( 2020 ) conduct an analysis of different forward‐looking uncertainty measures during the pandemic. Coibion et al. ( 2020a ) use surveys to assess the macroeconomic expectations of households in the United States. They find that it is primarily lockdowns, rather than the infections themselves, that lead to declines in consumption spending and employment, lower inflationary expectations, increased uncertainty, and lower mortgage payments being made.

Eichenbaum et al. ( 2020 ) model the interactions between economic decisions and the spread of the virus. They find that, without any mitigation measures, aggregate consumption falls by 9.3% over a 32‐week period. On the other hand, labor supply or hours worked follow a U‐shaped pattern, with a peak decline of 8.25% in the 32nd week from the start of the pandemic. These reductions decrease peak infection rates and death tolls from 7% and 0.30% to 5% and 0.26% respectively, but worsen the magnitude of the recession. Infected people fail to internalize the impact of their choices on the spread of the virus. Therefore, the optimal containment policy increases the severity of the recession but saves lives. 13

Mulligan ( 2020 ) assesses the opportunity cost of “shutdowns” in order to document the macroeconomic impact of COVID‐19. Within the National Accounting Framework for the United States, the author extrapolates the welfare loss stemming from “nonworking days,” the fall in the labor‐capital ratio resulting from the absence/layoff of workers, and the resulting idle capacity of workplaces. After accounting for dead‐weight losses stemming from fiscal stimulus, the replacement of normal import and export flows with black market activities, and the effect on nonmarket activities (lost productivity, missed schooling for children and young adults), the author finds the welfare loss to be approximately $7 trillion per year of shutdown. Medical innovations, such as vaccine development, contact tracing, and workplace risk mitigation can help to offset the welfare loss by around $2 trillion per year of shutdown.

Other researchers have examined the supply side. Bonadio et al. ( 2020 ) use a quantitative framework to simulate a global lockdown as a contraction in labor supply for 64 countries. The authors find that the average decline in real GDP constitutes a major contraction in economic activity, with a large share attributed to disruptions in global supply chains. Elenev et al. ( 2020 ) model the impact of COVID‐19 as a fall in worker productivity and as a decline in labor supply, which both adversely affect firm revenue. The fall in revenue and the subsequent non‐repayment of debt‐servicing obligations spur a wave of corporate defaults, which might also bring down financial intermediaries. Céspedes et al. ( 2020 ) formulate a minimalist economic model in which the virus also leads to losses in productivity. The authors predict a vicious cycle triggered by the loss of productivity causing lower collateral values, in turn limiting the amount of borrowing activity, subsequently leading to decreased employment, followed by a further decline in productivity. The shock is thus magnified through an “unemployment and asset price deflation doom loop” (see Fornaro & Wolf, 2020 ).

Consumption pattern responses and debt responses from pandemic shocks had not been analyzed prior to COVID‐19 (Baker et al., 2020 ). Using transaction‐level household data, these authors find that households sharply increased their spending during the initial period in specific sectors such as retail and food spending. These increases, however, were followed by a decrease in overall spending. Similarly, Chang and Meyerhoefer ( 2020 ) show that consumers in Taiwan have increased food purchases from online platforms. Binder ( 2020 ) conduct an online survey of 500 United States consumers to investigate their concerns and responses related to COVID‐19, which indicated those items of consumption on which they were spending either more or less. They find that 28% of the respondents in that survey postponed future travel plans, and that 40% forewent food purchases. Interestingly, Binder ( 2020 ) finds from the surveys that consumers tend to associate graver concerns about COVID‐19 with higher inflationary expectations, a sentiment which serves as a proxy for “pessimism” or “bad times.”

Clemens and Veuger ( 2020 ) focus on the declines in government sales and income tax collections across US states. According to the authors, COVID‐19 has led to a substantial decline in consumption levels compared to income levels. This pattern is unlike the case in previous recessions, during which income decreased more than consumption. The authors find that the COVID‐19 pandemic will reduce the states’ tax collections by $42 billion in the second quarter of 2020. For fiscal year 2021, the authors anticipate an overall decline in sales and income tax revenues of $106 billion with heterogenous losses across US states.

McKibbin and Fernando ( 2020 ) estimate the aggregate economic costs. Using a hybrid DSGE/CGE global model, the authors model COVID‐19 as a negative shock to labor supply, consumption spending, financial markets, but as a positive shock to government expenditure, particularly stemming from health‐related expenditures. The authors outline seven different scenarios and provide a range of estimates of the increase in mortality and the fall in GDP for a number of countries across the world. In the case of the most contained outbreak, the number of deaths reaches around 15 million, while the reduction in global GDP is around $2.4 trillion in 2020.

Eppinger et al. ( 2020 ) use a quantitative international trade model with input‐output linkages for 43 countries to assess the impact of COVID‐19 supply shock on global value chains. They find that due to the supply shock, China experienced a welfare loss of 30% with moderate (positive or negative) spillover to other countries. Estimating a simulation consisting of a counterfactual scenario described as “without global value chains,” the authors find that welfare losses are reduced for some countries by as much as 40%, while they are magnified for others.

The economic impact of shocks, such as pandemics, is usually measured with aggregate time series data. However, these datasets are available only after a certain lag. In order to analyze the economic impact at a higher frequency, Lewis et al. ( 2020 ) developed a weekly economic index (WEI) using 10 different economic variables to track the economic impact of COVID‐19 in the United States. These authors report that between March 21 and March 28, the WEI declined by 6.19%. This was driven by a decline in consumer confidence, a fall in fuel sales, a rise in unemployment insurance (UI) claims, and changes in other variables. Similarly, Demirguc‐Kunt et al. ( 2020 ) estimate the economic impact of social distancing measures via three high‐frequency proxies (electricity consumption, nitrogen dioxide emissions, and mobility records). The authors find that social distancing measures led to a 10% decline in economic activity (as measured by electricity usage and emissions) across European and Central Asian countries between January and April. Chetty et al. ( 2020 ) develop a real‐time economic tracker using daily statistics on consumption, employment, business revenue, job postings, and other variables. The authors show that the initial slowdown in economic activity was partly driven by reductions in consumption by high‐income individuals. These spending shocks negatively affected business revenues catering to high‐income individuals. Subsequently, low‐income individuals working for these businesses lose much of their incomes and reduce their consumption levels. Kapteyn et al. ( 2020 ) tracked a representative sample of 7,000 respondents in Los Angeles County, California every 2 weeks to assess the impact of COVID‐19 over time.

Brinca et al. ( 2020 ) estimate the labor demand and supply shocks occurring in different sectors in the US economy employing a Bayesian structural vector autoregression model. They find that the decrease in work hours can be attributed to negative labor supply shock, a result that they suggest has important policy design implications. A negative labor supply shock is directly related to the lockdown and might be mitigated once such policies are lifted.

5. SOCIOECONOMIC CONSEQUENCES OF COVID‐19

We now review studies documenting the socioeconomic consequences of COVID‐19 and the ensuing lockdowns. Social distancing and lockdown measures have been shown to adversely affect labor markets, mental health and well‐being, racial inequality, and gender‐related outcomes. The environmental implications, while likely to be positive overall, also deserve careful analysis.

5.1. Labor market outcomes

A large number of studies document the effects on the variables of hours of work and job losses (e.g., Kahn et al., 2020 ). The major increases in unemployment observed in the United States are driven partly by lockdowns and social distancing policies (Rojas et al., 2020 ). Accounting for cross‐state variation in the timing of business closures and stay‐at‐home mandates in the United States, Gupta et al. ( 2020 ) find that the employment rate in the United States falls by about 1.7 percentage points for every extra 10 days that a state experienced a stay‐at‐home mandate during the period of March 12th to April 12th.

Coibion et al. ( 2020b ) find that the level of unemployment and job losses in the United States is more severe than one might judge based on the rise in UI claims, which is to be expected given the low coverage rate of the UI regimes in the United States. They also project a severe fall in the labor participation rate in the long run accompanied by an increase in the number of “discouraged workers” (jobless workers who have stopped actively searching for work, effectively withdrawing from the labor force). This phenomenon might be due to the disproportionate impact of COVID‐19 on the older population. Aum et al. ( 2020a , 2021b ) find that an increase in infections leads to a drop in local employment even in the absence of lockdowns in South Korea, whose government did not mandate them. This estimated impact was higher for countries, such as the United States and the United Kingdom, where mandatory lockdown measures were imposed.

Adams‐Prassl et al. ( 2020a ) analyze the inequality of the distributions of job and income losses based on the type of job held and on individual characteristics for the United States and the United Kingdom. The authors find that workers who can perform none of their employment tasks from home are more likely to lose their job. This study also finds that younger individuals and people without a university education were significantly more likely to experience drops in their income. Yasenov ( 2020 ) finds that workers with lower levels of education, younger adults, and immigrants are concentrated in occupations whose tasks are less likely to be performed from home. Similarly, Alstadsæter et al. ( 2020 ) find that the pandemic shock in Norway has a strong socioeconomic gradient, as it has disproportionately affected the financially vulnerable population, including parents with younger children.

Béland, Brodeur, and Wright ( 2020 ) discuss heterogeneous effects across occupations and workers in the United States, showing that occupations that have a higher share of workers working remotely were less affected by COVID‐19. On the other hand, occupations with relatively more workers working in proximity to others were more affected. They also find that occupations classified as “more exposed to disease” are less affected, which is possibly due to the number of essential workers in these occupations. Based on these results, it can be reasonably expected that workers might change (or students might select different) occupations in the medium term. Bui et al. ( 2020 ) focus on the impact of COVID‐19 on older workers in the United States. Using CPS data, they show that older workers who are over 65 years of age, especially women, are facing higher unemployment in this COVID‐19 recession compared to previous ones.

Kahn et al. ( 2020 ) show that firms in the United States dramatically reduced job vacancies from the second week of March 2020 and thereafter. The authors find that the job vacancy declines occurred simultaneously with increasing UI claims. Notably, the labor market declines (proxied through reductions in job vacancies and increases in UI claims) were uniform across states, with no notable differences across states which experienced the spread of the pandemic, or implemented stay‐at‐home orders, earlier than others. The study also finds that the reductions in job vacancies were uniform across industries and occupations, except for those in front line jobs, such as nursing. Baert et al. ( 2020a ) investigate the impact of COVID‐19 on career prospects through surveys conducted in Belgium. They document concerns that were expressed about job losses and missing out on promotions, especially among migrant workers.

Fairlie ( 2020 ) analyzes the impact of COVID‐19 on the number of small businesses in the United States. Using the April 2020 CPS data, the author finds that the number of active business owners declined by 22% between February and April 2020. While most major industries faced large drop in business, the authors also find that female and immigrant‐owned businesses were disproportionately affected.

With the enforcement of social distancing measures, work from home has become increasingly prevalent. The degree to which economic activity is impaired by such social distancing measures depends largely on the capacity of firms to maintain business processes from the homes of workers (Alipour et al. 2020 ; Papanikolaou & Schmidt, 2020 ). Additionally, working from home or working remotely are much more common and are thought to cause lower productivity losses in industries that are staffed by better educated and better paid workers (Bartik et al., 2020 ). Brynjolfsson et al. ( 2020 ) find that the increase in cases per 100k individuals is associated with a significant rise in the fraction of workers switching to remote work and the fall in the fraction of workers commuting to work in the United States. Interestingly, the authors find that people working from home are more likely to claim UI (if they are laid off) than people who are still commuting to work and are likely working in industries providing essential services.

Dingel and Neiman ( 2020 ) analyze the feasibility of jobs that can be done from home. They find that 37% of jobs can be feasibly performed from home. A different but related context for the feasibility of work from home is the extent to which the job involves face‐to‐face (F2F) interaction. According to Avdiu and Nayyar ( 2020 ), the job‐characteristic variables of home‐based work (HBW) and F2F interaction differ along three main dimensions, namely: (i) temporal (short run vs. medium run); (ii) the primary channel of effects (supply and demand of labor for the occupation/tasks); and (iii) the relevant margins of adjustment (intensive vs. extensive). They argue that the supply of labor in industries with HBW capabilities and low F2F interactions (e.g., professional, scientific, and technical services) might be the least affected. Nevertheless, those industries and occupations with HBW capabilities and high F2F interactions are likely to experience negative productivity shocks. As lockdown restrictions are lifted, industries with low HBW capabilities and low F2F interactions (e.g., manufacturing, transportation, and warehousing) might be able to recover relatively quickly. The risk of infection through physical proximity can be mitigated by wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) and by taking other relevant precautionary measures. However, those industries with low HBW capabilities and high F2F interactions (e.g., accommodation and food services, arts entertainment and recreation) are likely to experience slower recoveries, as consumers might be apprehensive about patronizing them, for example, cinemas and restaurants. Using a web survey in Belgium, Baert et al. ( 2020b ) find that a majority of respondents thought that teleworking and digital conferencing were here to stay and will become more common in the postpandemic period.

From the firm's perspective, there are large short‐term effects of temporary closures, such as the (perhaps permanent) loss of productive workers and declines in job postings, all of which are characterized by strong heterogeneity across industries. Bartik et al. ( 2020 ) survey a small number of firms in the United States and document that several of them have temporarily closed shop and reduced their number of employees compared to January 2020. The surveyed firms were not optimistic about the efficacy of the fiscal stimulus implemented by the federal government of the United States. Campello et al. ( 2020 ) find that job losses have been more severe for industries with highly concentrated labor markets (i.e., where hiring is dominated by a few employers), nontradable sectors (e.g., construction, health services), and credit‐constrained firms. Hassan et al. ( 2020 ) discern a pattern of heterogeneity with respect to firm resilience across industries around the World. Based on earnings call reports, they provide evidence that some firms are expecting increased business opportunities in the midst of the global disruption (e.g., firms which make medical supplies or others whose competitors are facing negative impressions after the outbreak due to their association with regions where case numbers are high). Barrero et al. ( 2020 ) measure the reallocation of labor in response to the pandemic‐induced demand response (e.g., increased hiring by delivery companies, delivery‐oriented restaurant/fast food chains, technology companies).

To conclude this subsection, a large number of studies try to predict labor market outcomes by exploiting high frequency data (e.g., Adams‐Prassl et al. 2020a , Chetty et al., 2020 ). For instance, Bartik et al. ( 2020 ) and Kurmann et al. ( 2020 ) rely on worker‐firm matched daily data drawn from “Homebase,” a scheduling and time clock software provider, to construct real‐time data for small businesses. Other studies have also used high‐frequency electricity market data to estimate the short‐run impacts of COVID‐19 on economic activity (e.g., Fezzi & Fanghella, 2020 ).

5.2. Health outcomes

The impact of the pandemic on physical health and mortality has been documented in many studies (e.g., Goldstein & Lee, 2020 ; Lin & Meissner, 2020 ). Knittel and Ozaltun ( 2020 ) document a positive correlation between the share of elderly population, the incidence of commuting via public transportation, and the number of COVID‐19 deaths in the United States. In contrast, the authors provide evidence that obesity rates, the number of ICU beds per capita, and poverty rates are not related to the death rate. Chatterji and Li ( 2021 ) document the effect of the pandemic on the US health care sector. The authors find that it is associated with a 67% decline in the total number of outpatient visits per provider by the week of April 12th‐18th 2020 relative to the same week in prior years. This might have negative health consequences, especially among individuals with chronic health conditions. Hermosilla et al. ( 2020 ) show that COVID‐19 has crowded out non‐COVID‐19‐related health care demands in China. Others, such as Alé‐Chilet et al. ( 2020 ), explore the drop in emergency cases in hospitals around the world.

Nevertheless, during a crisis, such as the COVID‐19 pandemic, it is common for everyone to experience increased levels of distress and anxiety, particularly the sentiment of social isolation (American Medical Association, 2020 ). A growing number of studies document worsening mental health status and levels of well‐being (Adams‐Prassl et al. 2020b ; Brodeur, Clark, Fleche, & Powdthavee, 2021 ; Davillas & Jones, 2020 ; de Pedraza et al., 2020 , and Tubadji et al., 2020 ). According to Lu et al. ( 2020 ), social distancing or lockdown measures are likely to affect psychological well‐being through a lack of access to essential household supplies, discriminatory treatment, or exclusion by neighbors. They assert that maintaining a positive attitude (in terms of severity perceptions, the credibility of real‐time updates of information, and confidence in social distancing measures) can help reduce depression. Hamermesh ( 2020 ) also provides evidence that, adjusted for numerous demographic and economic variables, happiness levels during the COVID‐19 pandemic are affected by how people spend time and with whom. In the opposite case, using an experimental set‐up, Bogliacino et al. ( 2020 ) find that a negative shock triggered by COVID‐19 lowers cognitive functionality and increases risk aversion and the propensity to punish others, that is negative reciprocity. Public mental health is also affected by the cognitive bias related to the diffusion of public death toll statistics (Tubadji et al., 2020 ). These needs are all the less likely to be addressed given the lower levels of provision of health care and social work services.

Using the Canadian Perspective Survey Series, Béland, Brodeur, Mikola, and Wright ( 2020 ) find that those who missed work not due to COVID‐19, and those who were already unemployed, showed declines in mental health. Using panel data in the United Kingdom, Etheridge and Spantig ( 2020 ) report a large deterioration in the state of mental health, with much larger effects for women.

The implementation of lockdown policy also adversely affected public mental health. Armbruster and Klotzbücher ( 2020 ) demonstrate that there were increases in the demand for psychological assistance (through helpline calls) due to lockdown measures imposed in Germany. The authors find that these calls were mainly driven by mental health issues such as loneliness and depression. Brodeur, Clark, Fleche, & Powdthavee et al. ( 2021 ) show that there has been a substantial increase in the search intensity on Google for “boredom” and “loneliness” during the postlockdown period in nine Western European countries and the United States during the first few weeks of lockdowns. Using experimental surveys, Codagnone Bogliacino, Gómez, and Charris et al. ( 2020 ) find that about 43% of the population in Italy, Spain, and United Kingdom are at high risk of developing mental health problems; not only because of the negative economic shock, but also due to conditions of long‐standing economic weakness and vulnerability in those countries.

Fetzer et al. ( 2020 ) find that there has been broad public support for COVID‐19 containment measures. However, some of the respondents believe that the general public fails to adhere to health measures, and that the governmental response has been insufficient. These respondents have a tendency to exhibit a poorer state of mental health. If governments are seen to take decisive actions, however, then the respondents altered their perceptions about governments and other citizens, which in turn improved their state of mental health.

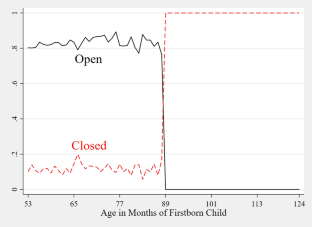

5.3. Gender and racial inequality

A growing literature points out that COVID‐19 has had an unequal impact between genders and across races in OECD countries; specifically, women and racial minorities, such as African‐Americans and Latinos, have been unduly and adversely affected. While it is thought that prior recessions typically affected men more than women, many studies provide evidence that COVID‐19 has large negative effects on women's labor market outcomes (Adams‐Prassl et al., 2020a ; Forsythe et al., 2020 ; Yasenov, 2020 ). Alon et al. ( 2020 ) argue that women's employment is concentrated in sectors such as health care and education. Moreover, the closure of schools and daycare centers led directly to increased childcare needs, which would have a negative impact on working and/or single mothers. For example, based on household surveys in Spain, Farré et al. ( 2020 ) find that while men increased their participation in household work and childcare duties during lockdowns, the burden of these tasks fell disproportionately on women.

Couch et al. ( 2020a ) examine the variation in unemployment shocks among minority groups in the United States. The authors find that Latino groups were disproportionately affected by the pandemic. They attribute the difference to an unfavorable occupational distribution (e.g., Latino workers tend to work in nonessential services) and to lower skill levels among them. Borjas and Cassidy ( 2020 ) determine that the COVID‐19 shock led to a fall in employment rates of immigrant men compared to native men in United States, which was in contrast to the historical pattern observed during previous recessions. The immigrants’ relatively high rate of job loss was attributed to the fact that immigrants were less likely to hold jobs that could be performed remotely from home. The likelihood of being unemployed during March 2020 was significantly higher for racial and ethnic minorities in the United States (Montenovo et al., 2020 ). In a similar vein, McLaren ( 2020 ) finds that minorities’ population shares in a county strongly correlate with COVID‐19‐related deaths in the United States. After controlling for the factors of education, jobs, and travel patterns, the correlation holds for the African‐American and the First‐Nations populations. The author shows that these racial disparities between African‐Americans, First Nations peoples, and others can be partially attributed to differentials in public transit usage patterns.

Couch et al. ( 2020b ) find that COVID‐19 has unduly affected women compared to men in the United States. Using employment to population ratios and number of hours from the CPS data, the authors find that women with school‐age children faced greater declines in employment and work hours compared to men between April and August 2020. The reductions in work hours and employment can be explained by additional childcare responsibilities, job and skill characteristics, and lower numbers of women involved in “essential” industries.

Schild et al. ( 2020 ) find that COVID‐19 occasioned a rise of Sino‐phobia across the internet, particularly when western countries started showing signs of infection. Bartos et al. ( 2020 ) document the causal effect of economic hardships on hostility against certain ethnic groups in the context of COVID‐19 using an experimental approach. The authors find that the COVID‐19 pandemic magnifies sentiments of hostility and discrimination against foreigners, especially those from Asia.

5.4. Environmental outcomes

The global lockdown and the considerable slowdown of economic activities are expected to have a positive effect on the environment (Almond et al., 2020 ; Cicala et al., 2020 ). He et al. ( 2020 ) show that lockdown measures in China led to a remarkable improvement in air quality. The Air Quality Index and the fine particulate matter (PM 2.5 ) concentrations were brought down by 25% within weeks of the lockdown, with larger effects recorded in colder, richer, and more industrialized cities. Similarly, Almond et al. ( 2020 ) focused on air pollution and the release of greenhouse gases in China during the post‐COVID‐19 period. They determined that, while nitrogen dioxide (NO 2 ) emissions fell precipitously, sulphur dioxide emissions (SO 2 ) did not decrease. For China as a whole, PM 2.5 emissions fell by 22%; however, ozone concentrations increased by 40%. These variations show that there is not necessarily an unambiguous improvement in air pollution due to the economic slowdown. The reduction can be attributed to less travel in personal vehicles causing lower nitrous oxide (NO 2 ) emissions.

Brodeur, Cook, & Wright ( 2021 ) examine the causal effect of “safer‐at‐home” policies on air pollution across US counties. They find that “safer‐at‐home” policies decreased air pollution (measured as PM 2.5 emissions) by almost 25% on average, with larger effects for populous counties. Cicala et al. ( 2020 ) focus on the health and mortality benefits of reduced vehicle travel and electricity consumption in the United States due to stay‐at‐home policies, suggesting that reductions in emissions from less travel and from lower electricity usage reduced deaths by over 360 per month.

On the other hand, Andree ( 2020 ) focuses on the effect of pollution on cases, finding that PM 2.5 levels are a highly significant predictor of COVID‐19 incidence using data from 355 municipalities in the Netherlands. In terms of COVID‐19‐related deaths, Knittel and Ozaltun ( 2020 ) find no evidence that pollution levels are related to death rates in the United States.

Based on the research discussed in section 5 above, Table 3 provides a summary of these strands of the literature dealing with the socioeconomic and environmental outcomes resulting from social distancing actions, stay‐at‐home orders, and/or lockdowns including a listing of the statistical measures and methodologies that were utilized.

Socioeconomic outcomes of COVID‐19 lockdowns: Summary of studies

6. POLICY MEASURES

The economic literature deals with a wide assortment of policy measures. We organize our presentation into six broad topics: (i) the types of policy measures, (ii) the determinants of government policy, (iii) optimal testing methods, (iv) the lockdown measures and their associated factors, (v) the lifting of the lockdown measures, and (vi) the economic stimulus measures.

To mitigate the negative effects of public health controls on the economy and to sustain and promote public welfare, governments all around the World have implemented a variety of policies within a very short time frame. These include fiscal, monetary, and financial policy measures (Gourinchas, 2020 ). The economic measures vary across counties in terms of breadth and scope, and they target households, firms, health systems, and/or banks (Weder di Mauro, 2020 ).

Using a database of economic policies implemented by 166 countries, Elgin et al. ( 2020 ) employ the technique of Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to develop their COVID‐19 Economic Stimulus Index. The authors correlate the standardized index with predictors of governmental response, such as population characteristics (e.g., median age), public health‐related measures (e.g., the number of hospital beds per capita), and economic variables (e.g., GDP per capita). They find that the economic stimulus is larger for countries with higher COVID‐19 infections, older median ages, and higher GPD‐per‐capita levels. In addition, the authors develop a “Stringency Index,” which includes measures such as school closures and travel restrictions. They find that the “Stringency Index” is not a significant predictor of their economic stimulus index, which suggests that public health measures do not drive economic stimulus measures (Weder di Mauro, 2020 ).

On a similar note, Porcher ( 2020 ) has created an index of public health measures using the PCA technique. The index is based on 10 common public health policies implemented across 180 countries to mitigate the spread of COVID‐19. The index is designed to measure the stringency of the public health response across countries. The author finds that, abstracting from the COVID‐19 case numbers and deaths, countries which have better public‐health systems and effective governance tend to have less stringent public health measures.

C. Cheng et al. ( 2020 ) develop the “CoronaNet–COVID‐19 Government Response Database,” which accounts for policy announcements made by countries globally since 31 December 2019. The information that is contained in this data base is categorized according to: (i) type of policy, (ii) national versus subnational enforcement, (iii) people and geographic region targeted by the policy, and (iv) the time frame within which it is implemented. Table 4 provides a description of the government response database for 125 countries. Counts are tabulated according to 15 types of interventions for two variables: cumulative number of policies (of that type) implemented and the number of countries which have implemented it. It also displays that average value for the degree of enforcement.

Summary statistics of COVID‐19 government response dataset

Source: C. Cheng et al. ( 2020 ).

There is substantial variation across policy measures. The policy most governments have implemented is “external border restriction,” that is, restricting access to entry through ports. It has been imposed by 186 countries; the second most common policy measure, implemented by 169 countries, is “school closures.” However, in terms of the frequency of implementation across all countries, the type of “obtaining or securing health resources” has the highest level. This includes the provision of materials (e.g., face masks), personnel (e.g., doctors, nurses), and infrastructure (e.g., hospitals). The second most frequently implemented policy is “restrictions on nonessential businesses.” In terms of stringency of policy enforcement, “emergency declaration” and the formation of a “new task force” or an “administrative reconfiguration to tackle pandemic” are implemented with 100% stringency.

Due to these major differences between policy responses across countries and over time, the authors use a dynamic Bayesian item‐response approach to measure the implied economic, social, and political cost of implementing a particular policy over time. They also develop a supplementary measure labelled the “Policy Activity Index,” which assigns a higher rank for policy measures to countries that are more willing to implement a “costly” policy. Based on that index, the authors determine that school closure is the costliest to implement followed by mandatory business closure and social distancing policies. Moreover, internal border restrictions are viewed as more costly compared to external border restriction.

The topic of optimal testing methods has received a great deal of attention in the media and, to some extent, in academia. A well‐known proposal defended by Paul Romer and many others is a comprehensive “test and isolate” policy, which would effectively reduce the effective reproduction number and allow the economy to operate more openly. 14 Taipale et al. ( 2020 ) formalize this proposal and argue that the epidemic would collapse at a sufficient rate of testing and isolation, and that concurrent testing would outperform random sampling of individuals. Other proposals for optimal testing include regular testing of people in groups that are more likely to be exposed to COVID‐19 (e.g., Cleevely et al., 2020 ; Gollier & Gossner, 2020 ), multi‐stage group testing (e.g., Eberhardt et al., 2020 ), and testing on exit from quarantine instead of upon entry (e.g., Wells et al. 2020 ).

The topic of optimal lockdown policies has been investigated mostly by using epidemiology macroeconomic models, some of which are oriented around the dichotomy between the case in which the choices (and responses) are all made by private agents and the case in which the choices are made by a social planner (Acemoglu et al., forthcoming; Alvarez et al., forthcoming; Berger et al., forthcoming; Bethune & Korinek 2020 ; Eichenbaum et al., 2020 ). Jones et al. ( 2020 ) argue that in contrast to private agents, the social planner will seek to front‐load mitigation strategies: that is to impose strict lockdowns from the beginning to reduce the spread of infection and let the economy to fall into a deep recession. This is because their model's set‐up not only considers the concomitant health care costs and congestion in hospitals, but also rightly considers the fact that workers need time to become productive for a work‐from‐home situation. The outcomes are dependent on the assumed values of the parameters that are inputted into these models. The optimal policy choice reflects the rate of time preference, epidemiological factors, the value of statistical life, the rate at which death rate increases in the infected population, the hazard rate for a vaccine discovery, the learning effects in the health care sector, and the severity of output losses due to a lockdown (Gonzalez‐Eiras & Niepelt, 2020 ). The intensity of the lockdown depends on the gradient of the fatality rate as a function of the number of infected individuals and on the assumed value of a statistical life. The absence of testing increases the economic costs of the lockdown and shortens the duration of the optimal lockdown (Alvarez et al., forthcoming). Chang and Velasco ( 2020 ) argue that the optimality of policies depends on peoples’ expectations. For instance, fiscal transfers must be large enough to induce people to stay at home in order to reduce the degree of contagion; otherwise they might not change their behavior in efforts to reduce the risk of infection. Their analysis also contains a critique of the use of SIR models, as the parameters used in that class of models (which remain fixed in value) would shift as individuals change their behavior in response to policy. Kozlowski et al. ( 2020 ) investigate the scarring effect on perceptions (i.e. the change in belief about the probability of an extreme but negative or tail‐risk event) of COVID‐19, and find that revisions in belief about tail‐risk events among economic agents will lead to a larger and more persistent negative impact on the economy in the long run.

When the daily death rates and case numbers decline, policies regarding reopening the economy are of primary importance. Gregory et al. ( 2020 ) describe the lockdown measure as a “loss of productivity,” whereby relationships between employers and laborers are suspended, terminated, or continued. They further explain that postpandemic, the speed and the type (V‐shaped or L‐shaped) of recovery depend on at least three factors: (i) the fraction of workers who, at the beginning of the lockdown, enter unemployment while maintaining a relationship with their employer, (ii) the rate at which inactive relationships between employers and employees dissolve during the lockdown, and (iii) the rate at which workers who, at the end of the lockdown, are not recalled by their previous employer can find new, stable jobs elsewhere (Gregory et al., 2020 ).

Harris ( 2020 ) points out the importance of utilizing several status indicators (e.g., results of partial voluntary testing, guidelines for eligibility of testing, daily hospitalization rates) in order to decide upon the course of action on reopening the economy. Kopecky and Zha ( 2020 ) state that decreases in deaths are either due to implementation of social distancing measures or to herd immunity; it is hard to identify and disentangle those factors using standard SIR models. They argue that with the “identification problem,” there will be considerable uncertainty about the conditions for restarting the economy. Only comprehensive testing can help resolve this ambiguity by quickly and accurately identifying new cases so that future outbreaks could be contained by isolation and contact‐tracing measures (Kopecky & Zha, 2020 ).

Agarwal et al. ( 2020 ) rely on synthetic control methods to investigate the effect of counterfactual mobility restriction interventions in United States. Using the daily death data from different countries, the authors create different “synthetic mobility United States” variables. These are applied to predict a counterfactual scenario and to understand the trade‐off between different levels of mobility interventions on death levels in United States. They find that a small decrease in mobility reduces the number of deaths; however, after registering a 40% drop in mobility, the benefits derived from mobility restrictions (in terms of the number of deaths) diminish. Using a counterfactual scenario, the authors find that lifting severe mobility restrictions but retaining moderate mobility restrictions (e.g., by imposing limitations in retail and public transport locations) might effectively reduce the number of deaths in United States. Others, such as Rampini ( 2020 ), make the case for the sequential lifting of lockdown measures for the younger population at the initial stages, followed by the older population at later stages. The authors state that the lower effect on the younger population group is a fortunate coincidence, and thus, the economic consequences of interventions can be greatly reduced by adopting a sequential approach. Oswald and Powdthavee ( 2020 ) make a similar case for releasing the younger population from mobility restrictions first on the grounds of higher economic efficiency (as they are more likely to be in the labor force) and their greater resilience against infections.

As some US states reopened, some researchers turned their focus on the immediate consequences. Nguyen et al. ( 2020 ) find that 4 days after reopening, mobility has increased by 6 to 8%, with greater increases across states which were late adopters of lockdown measures. These findings have important implications for the resurgence of cases, hospital capacity utilization, and further deaths. Dave, Friedson, Matsuzawa, and McNichols et al. ( 2020 ) analyze the effect of lifting the shelter‐in‐place order in Wisconsin, after the Wisconsin Supreme Court abolished it, on social distancing and the number of cases and find no statistically significant impact. W. Cheng et al. ( 2020 ) find that employment activity in the United States increased in May due to reopening in some states, mainly as a result of people who resumed working at their previous job. However, they find that the longer employees are separated from their firms, the more their re‐employment probabilities decline.