¿Cómo sabemos que el cambio climático es real?

Existe evidencia inequívoca de que la Tierra se está calentando a un ritmo sin precedentes. La actividad humana es la causa principal.

- Mientras que el clima de la Tierra ha cambiado a lo largo de su historia , el calentamiento actual está ocurriendo a un ritmo no visto en los últimos 10.000 años.

- Según el Panel Intergubernamental sobre Cambio Climático ( IPCC , por sus siglas en ingles), "Desde que comenzaron las evaluaciones científicas sistemáticas en la década de 1970, la influencia de la actividad humana en el calentamiento del sistema climático ha evolucionado de la teoría al hecho establecido". 1

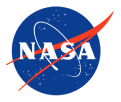

- La información científica extraída de fuentes naturales (como núcleos de hielo, rocas y anillos de árboles) y de equipos modernos (como satélites e instrumentos) muestra signos de un clima cambiante.

- Desde el aumento de la temperatura global hasta el derretimiento de las capas de hielo, abunda la evidencia del calentamiento del planeta.

La tasa de cambio desde mediados del siglo XX no tiene precedentes en milenios.

El clima de la Tierra ha cambiado a lo largo de la historia. Solo en los últimos 800.000 años, ha habido ocho ciclos de glaciaciones y períodos más cálidos, y el final de la última glaciación hace unos 11.700 años marcó el comienzo de la era climática moderna y de la civilización humana. La mayoría de estos cambios climáticos se atribuyen a variaciones muy pequeñas en la órbita de la Tierra que cambian la cantidad de energía solar que recibe nuestro planeta.

Obtén más información sobre los núcleos de hielo .

La tendencia de calentamiento actual es diferente porque es claramente el resultado de las actividades humanas desde mediados del siglo XIX y avanza a un ritmo que no se ha visto en muchos milenios recientes. 1 Es innegable que las actividades humanas han producido los gases atmosféricos que han atrapado una mayor parte de la energía del Sol en el sistema de la Tierra. Esta energía adicional ha calentado la atmósfera, el océano y la tierra, y se han producido cambios rápidos y generalizados en la atmósfera, el océano, la criósfera y la biosfera.

Los satélites en órbita terrestre y las nuevas tecnologías han ayudado a los científicos a ver el panorama general, recopilando muchos tipos diferentes de información sobre nuestro planeta y su clima en todo el mundo. Estos datos, recopilados durante muchos años, revelan los signos y patrones de un clima cambiante.

Los científicos demostraron la naturaleza de atrapar el calor del dióxido de carbono y otros gases a mediados del siglo XIX. 2 Muchos de los instrumentos científicos que usa la NASA para estudiar nuestro clima se enfocan en cómo estos gases afectan el movimiento de radiación infrarroja a través de la atmósfera. A partir de los impactos medidos de los aumentos de estos gases, no hay duda de que el aumento de los niveles de gases de efecto invernadero calienta la Tierra en respuesta.

La evidencia científica del calentamiento del sistema climático es inequívoca.

Grupo Intergubernamental de Expertos sobre el Cambio Climático

Los núcleos de hielo extraídos de Groenlandia, la Antártida y los glaciares de las montañas tropicales muestran que el clima de la Tierra responde a los cambios en los niveles de gases de efecto invernadero. También se puede encontrar evidencia antigua en anillos de árboles, sedimentos oceánicos, arrecifes de coral y capas de rocas sedimentarias. Esta evidencia antigua, o paleoclima, revela que el calentamiento actual está ocurriendo aproximadamente 10 veces más rápido que la tasa promedio de calentamiento después de una edad de hielo. El dióxido de carbono de las actividades humanas está aumentando unas 250 veces más rápido que el de las fuentes naturales después de la última Edad de Hielo. 3

La evidencia del cambio climático rápido es convincente:

La temperatura global está aumentando.

La temperatura promedio de la superficie del planeta ha aumentado aproximadamente 2 grados Fahrenheit (1 grado Celsius) desde finales del siglo XIX, un cambio impulsado en gran medida por el aumento de las emisiones de dióxido de carbono a la atmósfera y otras actividades humanas. 4 La mayor parte del calentamiento ocurrió en los últimos 40 años, los siete años más recientes han sido los más cálidos. Los años 2016 y 2020 están empatados como el año más cálido registrado. 5

El océano se está calentando

El océano ha absorbido gran parte de este aumento de calor, y los 100 metros superiores (alrededor de 328 pies) del océano muestran un calentamiento de más de 0,6 grados Fahrenheit (0,33 grados Celsius) desde 1969. 6 La Tierra almacena el 90 % de la energía adicional en el océano.

Las capas de hielo se están reduciendo

Las capas de hielo de Groenlandia y la Antártida han disminuido en masa. Los datos del Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment de la NASA muestran que Groenlandia perdió un promedio de 279.000 millones de toneladas de hielo por año entre 1993 y 2019, mientras que la Antártida perdió alrededor de 148.000 millones de toneladas de hielo por año. 7

Los glaciares están desapareciendo

Los glaciares se están retirando en casi todas partes del mundo, incluso en los Alpes, el Himalaya, los Andes, las Montañas Rocosas, Alaska y África. 8

La capa de nieve está disminuyendo

Las observaciones satelitales revelan que la cantidad de nieve primaveral en el hemisferio norte ha disminuido en las últimas cinco décadas y la nieve se está derritiendo antes. 9

El nivel del mar está aumentando

El nivel global del mar subió unas 8 pulgadas (20 centímetros) en el último siglo. Sin embargo, la tasa en las últimas dos décadas es casi el doble que la del siglo pasado y se acelera ligeramente cada año. 10

El hielo marino del Ártico está disminuyendo

Tanto la extensión como el grosor del hielo marino del Ártico han disminuido rápidamente en las últimas décadas. 11

Los eventos extremos están aumentando en frecuencia

La cantidad de eventos de temperatura alta récord en los Estados Unidos ha ido en aumento, mientras que la cantidad de eventos de temperatura baja récord ha disminuido desde 1950. Los EE. UU. también ha sido testigo de un número creciente de eventos de lluvia intensa. 12

La acidificación de los océanos está aumentando

Desde el comienzo de la Revolución Industrial, la acidez de las aguas superficiales del océano ha aumentado aproximadamente un 30 %. 13, 14 Este aumento se debe a que los seres humanos emiten más dióxido de carbono a la atmósfera y, por lo tanto, el océano absorbe más. El océano ha absorbido entre el 20 % y el 30 % de las emisiones antropógenas totales de dióxido de carbono en las últimas décadas (entre 7.200 y 10.800 millones de toneladas métricas al año). 15, 16

Referencias

- IPCC Fifth Assessment Report, Summary for Policymakers B.D. Santer et.al., “ A search for human influences on the thermal structure of the atmosphere ,” Nature vol 382, 4 July 1996, 39-46Gabriele C. Hegerl, “ Detecting Greenhouse-Gas-Induced Climate Change with an Optimal Fingerprint Method ,” Journal of Climate, v. 9, October 1996, 2281-2306V. Ramaswamy et.al., “ Anthropogenic and Natural Influences in the Evolution of Lower Stratospheric Cooling ,” Science 311 (24 February 2006), 1138-1141B.D. Santer et.al., “ Contributions of Anthropogenic and Natural Forcing to Recent Tropopause Height Changes ,” Science vol. 301 (25 July 2003), 479-483.

- En 1824, Joseph Fourier calculó que un planeta del tamaño de la Tierra, situado a nuestra distancia del Sol, debería ser mucho más frío. Sugirió que algo en la atmósfera debe estar actuando como una manta aislante. En 1856, Eunice Foote descubrió esa manta, mostrando que el dióxido de carbono y el vapor de agua en la atmósfera de la Tierra atrapan la radiación infrarroja (calor) que escapan del planeta. En la década de 1860, el físico John Tyndall identificó el efecto invernadero natural de la Tierra y sugirió que ligeros cambios en la composición atmosférica podrían provocar variaciones climáticas. En 1896, un artículo fundamental del científico sueco Svante Arrhenius predijo por primera vez que los cambios en los niveles de dióxido de carbono atmosférico podrían alterar sustancialmente la temperatura de la superficie a través del efecto invernadero. En 1938, Guy Callendar relacionó los aumentos de dióxido de carbono en la atmósfera terrestre con el calentamiento global. En 1941, Milutin Milankovic conectó las edades de hielo con las características orbitales de la Tierra. Gilbert Plass formuló la teoría del dióxido de carbono del cambio climático en 1956.

- Vostok ice core data; NOAA Mauna Loa CO 2 record Gaffney, O.; Steffen, W. (2017) " The Anthropocene equation ," The Anthropocene Review (Volume 4, Issue 1, April 2017), 53-61.

- https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/monitoring-references/faq/indicators.php https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/temperature/ http://data.giss.nasa.gov/gistemp

- https://www.giss.nasa.gov/research/news/20170118/

- Levitus, S.; Antonov, J.; Boyer, T.; Baranova, O.; Garcia, H.; Locarnini, R.; Mishonov, A.; Reagan, J.; Seidov, D.; Yarosh, E.; Zweng, M. (2017). NCEI ocean heat content, temperature anomalies, salinity anomalies, thermosteric sea level anomalies, halosteric sea level anomalies, and total steric sea level anomalies from 1955 to present calculated from in situ oceanographic subsurface profile data (NCEI Accession 0164586). Version 4.4. NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. Dataset. doi: 10.7289/V53F4MVP https://www.nodc.noaa.gov/OC5/3M_HEAT_CONTENT/index3.html von Schuckmann, K., Cheng, L., Palmer, D., Hansen, J., Tassone, C., Aich, V., Adusumilli, S., Beltrami, H., Boyer, T., Cuesta-Valero, F., Desbruyeres, D., Domingues, C., Garcia-Garcia, A., Gentine, P., Gilson, J., Gorfer, M., Haimberger, L., Ishii, M., Johnson, G., Killick, R., King, B., Kirchengast. G., Kolodziejczyk, N., Lyman, J., Marzeion, B., Mayer, M., Monier, M., Monselesan, D., Purkey, S., Roemmich, D., Schweiger, A., Seneviratne, S., Shepherd, A., Slater, D., Steiner, A., Straneo, F., Timmermans, ML., Wijffels, S. (2020). Heat stored in the Earth system: where does the energy go? Earth System Science Data (Volume 12, Issue 3, 07 September 2020), 2013-2041.

- Velicogna, I., Mohajerani, Y., A, G., Landerer, F., Mouginot, J., Noel, B., Rignot, E., Sutterly, T., van den Broeke, M., van Wessem, M., Wiese, D. (2020). Continuity of ice sheet mass loss in Greenland and Antarctica from the GRACE and GRACE Follow‐On missions . Geophysical Research Letters (Volume 47, Issue 8, 28 April 2020, e2020GL087291.

- nsidc.org/cryosphere/sotc/glacier_balance.html World Glacier Monitoring Service

- nsidc.org/cryosphere/sotc/snow_extent.html Robinson, D. A., D. K. Hall, and T. L. Mote. 2014. MEaSUREs Northern Hemisphere Terrestrial Snow Cover Extent Daily 25km EASE-Grid 2.0, Version 1 . [Indicate subset used]. Boulder, Colorado USA. NASA National Snow and Ice Data Center Distributed Active Archive Center. doi: https://doi.org/10.5067/MEASURES/CRYOSPHERE/nsidc-0530.001 . [Accessed 9/21/18]. http://nsidc.org/cryosphere/sotc/snow_extent.html Rutgers University Global Snow Lab, Data History Accessed September 21, 2018.

- R. S. Nerem, B. D. Beckley, J. T. Fasullo, B. D. Hamlington, D. Masters and G. T. Mitchum. Climate-change–driven accelerated sea-level rise detected in the altimeter era. PNAS , 2018 DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1717312115

- https://nsidc.org/cryosphere/sotc/sea_ice.html Pan-Arctic Ice Ocean Modeling and Assimilation System (PIOMAS, Zhang and Rothrock, 2003) http://psc.apl.washington.edu/research/projects/arctic-sea-ice-volume-anomaly/ http://psc.apl.uw.edu/research/projects/projections-of-an-ice-diminished-arctic-ocean/

- USGCRP, 2017: Climate Science Special Report: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume I [Wuebbles, D.J., D.W. Fahey, K.A. Hibbard, D.J. Dokken, B.C. Stewart, and T.K. Maycock (eds.)]. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, USA, 470 pp, doi: 10.7930/J0J964J6

- http://www.pmel.noaa.gov/co2/story/What+is+Ocean+Acidification%3F

- http://www.pmel.noaa.gov/co2/story/Ocean+Acidification

- C. L. Sabine et.al., “ The Oceanic Sink for Anthropogenic CO 2 ,” Science vol. 305 (16 July 2004), 367-371

- Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate , Technical Summary, Chapter TS.5, Changing Ocean, Marine Ecosystems, and Dependent Communities, Section 5.2.2.3. https://www.ipcc.ch/srocc/chapter/technical-summary/

Climate Change in Spain: Friend and Foe–Causes, Consequences and Response–

Latest Publications

Banning Russian LNG transhipment in European ports: a pragmatic and effective measure

Beyond Strategy? Industrial Strategy and the Future of European Defence

France’s Eastern Zeitenwende?

Climate change is unequivocal and Spain is one of the most vulnerable countries within the EU. The consequences of global warming will bring about higher temperatures, average sea level rises and a reduction in water availability, among others. The consequences for the Spanish economy will vary depending on the sector analysed. Tourism, the construction sector and the insurance sector stand to lose if mitigation and adaptation are further delayed.

Spain’s international commitments in the fight against climate change after the UNFCCC, and more so after ratifying the Kyoto Protocol, have spurred a host of institutional responses. These responses are depicted along with the key opportunities and challenges for the post Kyoto period.

Available cost estimates of climate change are presented. Mitigation and adaptation costs are also analysed, highlighting the preliminary nature of current studies and the need to broaden the knowledge of the economic costs of our actions.

Introduction

Climate change can be loosely defined as the alteration in climate patterns. According to the UNFCCC[1] this phenomenon ‘means a change of climate which is attributed directly or indirectly to human activity that alters the composition of the global atmosphere and which is in addition to natural climate variability observed over comparable time periods’ (UN, 1992, p. 3). The complexity of the climate system and the limitations in modelling imply that predictions are necessarily uncertain to an extent. There exists, however, a broad scientific consensus regarding the unequivocal warming of the earth. Global warming and its associated damages bring about the need to limit the concentration of greenhouse gases (GHG) in the atmosphere in order to minimise the possibility of a dangerous interference with global climate stability. The EU’s recommendation is to limit GHG concentrations in the atmosphere to 550ppm[2] and limit temperature increases to 2ºC, as global average temperature increases above this will most likely imply irreversible effects (Abanades García et al., 2007). The Stern Review states that this stabilisation target will imply allowing GHG emissions to peak in the next decade or two and then ensuring a decline in GHG emissions of between 1% and 3% per year.[3]

Climate change has both positive and negative consequences.[4] The developed countries located in the North might benefit from higher agricultural yields (harvesting plant varieties that had hitherto been unable to grow in colder areas), reduced heating demands and a reduction in the number of cold-related deaths, among others. These countries are nevertheless exposed to temperature increases and sea level rises that can alter ecosystems, human health and economic activities. Damages from climate change will not be evenly distributed among countries. Developing countries and some developed countries located in the South of Europe such as Spain will suffer the consequences of more severe and more frequent extreme weather events, reductions in rainfall, increases in heat-related illnesses and deaths plus the displacement or decline of certain economic activities. Eastern and Mediterranean Europe is expected to suffer more floods and more frequent and severe droughts (EEA, 2007). Overall, the greater the rise in temperatures the more severe the consequences of global warming will be.

The problem we face is a global one in need of broad and deep international agreements that take into account each country’s responsibilities and damages. Countries will therefore have to make individual efforts to mitigate GHG emissions according to the principle of shared but differentiated responsibilities. Additionally, all countries will adapt to global warming to a greater or lesser extent depending on the damages caused to their territory and on their adaptation capabilities. This paper focuses on the causes and consequences of climate change in Spain as well as the actions taken and planned to mitigate and adapt to one of the greatest threats of the 21st century. The analysis will conclude with a presentation of the latest guidelines for the post-Kyoto negotiations.

Causes of Climate Change and the Main Consequences for Spain

In a nutshell, the process of anthropogenic climate change originates from human activities in the form of production, consumption and distribution processes and population growth. Human activity entails emitting greenhouse gases which trap heat, thus warming the Earth. In Spain, the main activities that contribute to GHG generation and accumulation in the atmosphere are mainly related to the production and use of energy, agriculture, stockbreeding and industrial activity. Graph 1 shows the breakdown of the main sectors’ contributions to GHG emissions.

The main sectors that contribute to energy derived emissions are: electricity (24.04%), road transport (21.66%), industrial energy consumption (16.33%), residential uses (6%), oil refining (3%) and services (2.8%).

The consequences of climate change in Spain are being analysed by a growing number of institutions. To date, the most comprehensive study[5] is is the one developed by Moreno et al ., (2005) and the following analysis draws on this assessment as well as on the IPCC’s 4AR,[6] Martín Vide (2007), the EEA (2007), Abanades García et al., (2007), and others. The overall impact of climate change throughout the 21st century will be increasing temperatures and average sea level rises. Temperature increases will be more severe during the summer and inland. Rainfall trends are harder to predict, but both past trends and projections show a reduction in expected rain and lower water availability that will be discussed below. Temperature anomalies will become more common with more days reaching maximum temperatures. These tendencies will be exacerbated the higher the concentration of GHG in the atmosphere. Different ecosystems and activities will be affected in Spain. The main consequences can be summarised as follows:

Terrestrial Ecosystems According to the IPCC (4AR), the resilience of many ecosystems is likely to be exceeded during the 21st century. Ecosystems will experience alterations in periodic and seasonal plant and animal behaviour (eg, birds will alter their migration habits). For example, in Spain, Catalonia has recorded tree leaves unfolding 20 days earlier compared with their sprouting period 50 years ago. The extent to which affected species will be able to adapt is uncertain. Changes in the interaction of species will take place and we can expect increases in plagues and invasive species which cause biodiversity losses (as invasive species can appropriate the niche of native species and thereby displace them). These effects will be more severe in previously vulnerable isolated areas and islands, among others. Given that preserving these ecosystems can run against the development of other economic activities (eg, preserving forests can run against land use planning decisions, for instance), the recommendations are to implement holistic management schemes in which competing interests are taken into account. The long-term follow-up of terrestrial ecosystems from a multidisciplinary stance is recommended, along with determining tolerance levels with regards to climate change.

Aquatic Ecosystems Both inland and marine aquatic systems will be affected by climate change. Lakes, rivers, coastal wetlands and lagoons will be among the most severely affected. In coastal areas the expected sea level rise is projected to be between 10cm and 68cm by the end of the century, with a 50cm average sea level rise as a reasonable forecast (Moreno et al ., 2005). The main areas affected by floods include the Cantabrian Coast and the deltas of the Ebro and Llobregat and the coast of Doñana among others. Buildings and infrastructures in these areas will suffer the consequences of the expected rise in the sea level.

The productivity of certain commercial varieties is expected to decline, especially boreal species. Additionally, species such as the jelly fish are expected to become more frequent, especially in Catalonia, Mar Menor and the Canary Islands. Both warmer sea temperatures and increases in organic nutrients in the water are suspected to favour this. Theeffects of having more jelly fish in our beaches are as yet impossible to know with any degree of certainty but the phenomenon is expected to reduce tourism in the affected areas. On a brighter note, subtropical species such as the marlin will increase, partly offsetting the decline in other species.

Water Availability Reductions in water resources and a greater variability in the availability of water are both expected throughout the century. Simulations made by Moreno et al ., (2005) tell us that for a 1ºC increase in temperature there will be a 5% drop in rainfall which will mean a reduction in water availability of between 5% and 14% by 2030. This reduction in water resources can grow to 20% by the end of the century. The Canary Islands and the Balearic Islands will be the most affected regions along with the Guadiana, Guadalquivir, Júcar and Segura river basins. Uncertainties in regional precipitation projections are still significant according to the IPCC (2007) and to Martín Vide (2007) and further research and modelling should emerge from ongoing research to provide better estimates in this area. In any case, the available data for Spain from 1875 to the end of the last century points to a drier south, no significant change in the central part of the peninsula and a slight increase in rainfall in the North-West (see Map 1).

Data from the National Meteorology Institute depict a statistically significant decrease in winter rainfall in Spain (which is the main component of our rainfall according to Ayala Carcedo, 2004) in the last half of the XX century (see Graph 2).

The expected trend throughout the 21st century will entail a reduction in annual rainfall, particularly during the latter part of the century and during the spring. The area to be most affected will be the South-Eastern part of the Iberian Peninsula. This tendency is however reversed in the North-West, where rainfall is expected to increase. Reduced rainfall and droughts have already caused damage to the Spanish economy, costing over €3 billion in losses in 1999 (EEA, 2007).

Biodiversity Although there are many definitions, according to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD, 1992, article 2) biodiversity is ‘the variability among living organisms from all sources including, inter alia , terrestrial, marine and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are part; this includes diversity within species, between species and of ecosystems’. Spain has a large share of the EU’s plant diversity and it is also considered to be the richest in terms of animal diversity. Moreover, we also have a significant proportion of endemic species. Spain’s biodiversity losses are therefore relevant in terms of a wider geographical scope especially because of the phenomenon’s irreversible nature. The effect of less water availability and changes in rainfall patterns will lead to a more Mediterranean North and a more arid South in Spain. Forests in the South, mountain vegetation and coastal vegetation are among the most vulnerable. In addition to these effects, changes in migration and reproduction patterns are expected. This will affect different species in different ways thus leading to declining numbers in the most vulnerable species and to the displacement of other species towards the North.

Soil Resources, Forests and Agriculture The expected consequences of climate change in this area will include an increase in desertification (which already affects 31.5% of our territory, Abanades García et al. , 2007), erosion, salinisation, changes in forest species and a higher risk of fires. The presence of organic carbon in our soils (essential to soil fertility) is expected to decrease between 6% and 7% for every degree in temperature increase, especially in more humid areas such as the North of Spain and in forests. Tree mortality is also expected to increase as the temperatures rise (EEA, 2007).

The agricultural sector presents a mixed picture with higher agricultural yields, due to greater photosynthesis in the North of Spain, and reductions in agricultural yields in the South. For higher emission scenarios, however, Spain’s agricultural yields are projected to exhibit significant reductions in most parts of our territory. According to EEA (2007), crop yields are expected to record reductions of between 15% and 30% for most parts of the country (see Map 2).

The Energy Sector Temperature increases of 3ºC are said to cause a 10% variation in energy consumption (Lloyd’s, 1999, in Moreno et al ., 2005). Climate change is expected to lead to increases in the demand for electricity, oil and gas in Spain. Temperature increases and the reduction in water availability will reduce the production of hydraulic energy and biomass. Solar energy, which is said to hold the greatest potential, will furthermore be boosted by more hours of sun. Wind energy, that has seen the greatest growth in recent years, can also benefit from expected stronger winds. The EU’s determination to move towards a greater use of renewable energy and Spain’s vast potential in wind capacity make this strategic sector an attractive one. Table 1 compares the installed wind power across the EU.

Renewable energies, such as onshore wind power, are cleaner (compared with oil or gas, for example) in terms of GHG emissions. No energy source, however, is free from problems. For instance, onshore wind power has faced opposition due to the impact on certain bird species such as the Griffon Vulture. According to experts from CSIC[7] the overall impact on birds from onshore wind power is of low to medium intensity compared with the number of deaths caused by road collisions, for example. This, however, seems unsurprising given the lower number of wind generators compared with the number of roads and their length in kilometres. The design of models to predict which areas are used by the most vulnerable species, plus the search for scientific consensus and action protocols to help decide which areas should be avoided when planning wind power installations, is paramount to minimise the opposition to this renewable energy source.

The Tourist Sector Given the strategic economic relevance of the tourist sector for the Spanish economy (10.8% of Spain’s GDP in 2006)[8] it is important to be aware of the main consequences of climate change in this area. Global warming will entail changes in tourist activities mainly for ‘sun and sand tourism’ and for ‘snow-based tourism’. Climate change will mean more mountain trekking and less skiing, especially for resorts located below 2,000 metres. It will also bring about relative increases in inland stays versus coastal tourism.

In Madrid, for instance, the data available from one of the weather stations in Navacerrada show a significant reduction in the number of days it snowed between the 1970s and the end of the last century. This will affect the quantity and the quality of snow and is therefore expected to lead to a reduction in this type of activity.

The peak tourist season might be altered and more tourists might arrive during shoulder seasons (spring and autumn) and during the low season. Potential droughts and water supply problems, especially on the Mediterranean coast, the Balearic Islands and the Canary Islands, plus flooding of coastal areas, might hinder growth in this sector and, unfortunately, risk and sensitivity maps are still part of our collective wishful thinking in planning tourist and urban infrastructures. Overall, however, the picture is mixed –as it has been for other areas of analysis– since the damages to more vulnerable areas might be partially offset by the development of other tourist destinations. Protected natural areas, the Northern part of Spain and different activities such as inland sports and river sports may become increasingly attractive for tourists.

In any case, under high-emission scenarios, compared to other European tourist destinations, greenhouse emission increases and their related consequences are expected to reduce Spain’s attractive tourist profile in favour of Northern destinations. The PESETA project[9] estimates that high-emission scenarios will imply a worsening of tourist conditions for the last third of the present century. These would deteriorate from excellent (in red in Map 3 below), very good (in yellow) and good (in green) to mainly acceptable (in blue).

The Insurance Sector According to insurance companies and IPCC reports, both the frequency and extent of losses derived from climate-related events have increased. The data for Spain in this area are limited according to Moreno et al . (2005) and thus both the information presented and the conclusions drawn are to be taken with caution. Extreme weather events such as floods, storms, rain, hail, high wind and damages caused by the sea have been the most frequent occurrences in Spain in the data analysed. Of these events, 80% are caused by floods and 40% of the damage has occurred in Valencia and Vizcaya, with an even spread of the damage between the two areas. Mitigation efforts and the adaptation of urban planning decisions to avoid particularly sensitive areas are recommended in order to limit future increases in insurance premiums and compensation payments. Despite other factors influencing the insurance sector, climate change is expected to increase potential losses. The European Environment Agency provides estimates of climate-related losses in 2004 and of expected losses for the EU, the US and Japan (see Table 2).

Table 2. Expected climate-related insurance losses

Source: EEA (2007), p. 43.

Health According to Moreno et al., (2005, p. 707), ‘Climate changes can specifically affect temporal and spatial distribution, as well as the seasonal and interannual dynamics of pathogens, vectors, hosts and reservoirs’. Atmospheric pollution, heat waves and cold spells are related to higher rates of respiratory diseases, heart episodes and climate-related deaths. Pregnant women, young children, poor people and the elderly are considered the most vulnerable groups. According to the IPCC 4AR, with temperature increases of 3ºC or more, the expected burden on health services will rise. Examples of heat waves such as the one suffered in Europe in August 2003, which caused thousands of deaths, will become more frequent and intense. Added to these, some disease vectors such as dengue fever, malaria, West Nile encephalitis and ticks could increase, although other factors such as increased travel to areas where these illnesses are more common will also favour their spread. The preliminary nature of the analysis of the effects of climate change on Spain again calls for caution in the interpretation of the data presented above. The need for more research and more primary data seems to lie at the heart of good policy making in this area in order to minimise the most damaging consequences of climate change.

According to the EEA (2007), the development of information on the costs of climate change is still at an early stage and the figures presented below are likely to provide the lower bound estimates of the damages of global warming as many unquantifiable damages are left out of the analyses. This is due to the fact that accurately estimating the impacts of climate change is a complex endeavour. This is coupled with the difficulty in valuing these consequences in monetary terms, especially when non-use values, that can only be captured by stated preference techniques, are large. Simplified climate models and simplified ‘impact relationships’ lead to partial and uncertain outcomes. There are damages that are not adequately captured by the models, there is uncertainty about the exact damages and there may be losses that we are currently unable to predict. This wealth of limitations and uncertainties plus the different assumptions made by researchers might explain the disparity in the costs of climate change that are published in different academic and policy papers.

Tol (2005) reviewed the literature on estimates of the marginal damage costs of CO2 emissions and concluded that they are unlikely to exceed US$50/tC.[10] This figure contrasts with the Stern review that estimates the marginal damage of a ton of carbon at US$312/tC. The IPCC (2007) presents the figures for the social cost of carbon[11] to vary between US$-3 to US$95 per tonne of CO2 with an average value, among the peer-reviewed estimates analysed, of US$12. Differences in parameters and assumptions yield wide-ranging estimates and we are still far from a scientific consensus regarding the cost of emitting GHG. Regional differences in exposure to climate change and adaptation capabilities will imply damages are unevenly distributed and regional estimates are therefore vital in order to understand the full extent of the consequences of climate change for a given region.

At a global scale, the costs of inaction if temperatures rise above 2º-3ºC are expected to damage almost all countries. For rises in temperatures above 4ºC, global GDP losses are estimated at between 1% and 5% according to the IPCC. The costs of inaction on a global scale for the Stern review are significantly larger, causing an indefinite drop in global consumption ranging from 5% to 20% depending on the assumptions made. According to the Spanish Office for Climate Change, there are no overall cost estimates of climate change for Spain at present.[12]

Actions and the Cost of Actions for Spain

This subsection will present Spain’s most noteworthy actions to limit GHG emissions, the main adaptation actions and the expected cost of these actions whenever the data is available. The potential impact of climate change as well as the preliminary costs presented above are a powerful call for action. Spain agreed to be part of the international efforts to curb global warming. This commitment was put forth through its membership of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which was the first multilateral milestone in the fight against global warming, and though its ratification of the Kyoto Protocol (KP). The KP was approved by the third Conference of Parties (COP) in 1997 and entered into force on 16 February 2005 after Russia’s ratification in November 2004. At a global scale, the KP’s goal is to reduce GHG emissions by 5.2% by the first commitment period (2008-12). As part of the EU bubble that agreed to reduce its GHG emissions by 8% of its 1990 emissions, Spain was allowed to increase its emissions by 15% for the first KP commitment period.

The evolution of GHG emissions in Spain from 1990 to 2006 shows a significant increase, well above its KP goal. The rise in GHG emissions has been coupled with an increase in economic growth. The trend in Spain’s GHG emissions started to change in 2006 and a 4.1% decrease in GHG emissions was reported along with a drop in primary energy consumption of 1.3% despite a 3.9% increase in economic growth (MMA, 2007, and Nieto & Santamarta, 2007). Graph 2 illustrates historical emissions in Spain as percentage increases compared to 1990 as well as the goal to be achieved by Spain according to its KP commitments. Except for a decline in 1993, 1996 and 2006, GHG emissions have soared, reaching 48.1% above 1990 levels. Population and economic growth, an increasing energy demand and changing lifestyles have all contributed to this trend.

Spain’s response to climate change has been articulated by multiple institutions. The former Ministry of the Environment was the institution in charge of developing and implementing climate change policies at the state level. Since March, the Ministry has been restructured. It now includes rural and marine environments within its competences at the central government level. The change has not altered the fact that nation-wide climate change policies will be dealt with by the Ministry. More specifically, the Spanish Office for Climate Change[13] is in charge of developing climate change policies and providing administrative and technical support for the National Climate Council.[14] The latter was established in 1992 to provide information about the potential effects of climate change in Spain, promote research in this area, provide policy guidance for the government on climate policies and develop the National Climate Plan. A further institution is the Coordination Commission for Climate Change Policies,[15] whose main task is to coordinate climate change initiatives between the central government and the autonomous communities (regions). Finally, the Inter-cabinet Group for Climate Change[16] was designed as a coordinating institution within the central government sphere. Its main task is to develop preparatory work for the government’s delegate commission for economic affairs.[17]

According to the Spanish Office for Climate Change (OECC, Pers. Comm., 2008) there are currently no final estimates of the cost of mitigating or of adapting to global warming in Spain. The costs of the latter are only expected to be available once adaptation measures are well under way. On a global scale, the IPCC acknowledges ‘much less information is available about the costs and effectiveness of adaptation measures than about mitigation measures’ (IPCC, 2007, p. 56). In what follows the main initiatives to mitigate and adapt to climate change will be explored and cost estimates will be offered when available according to official data published by the institutions in charge of climate change policies or by academic research when appropriate. These estimates will depend on the assumptions made (eg, expected economic growth, emissions growth, the evolution of the energy sector, the discount rate used, the policy instruments used, etc.) and therefore figures should be taken with caution.

Mitigation will be more costly the higher the emission scenarios from which we decide to reduce emissions and the more stringent targets we set. The IPCC’s Fourth Assessment Report estimates that the cost of reducing a tonne of CO2 equivalent ranges from slightly negative to US$100. A more wide-ranging summary of the costs of action under different stabilisation targets is provided in Table 3 below.

Table 3. IPCC’s (2007) estimates on the costs of stabilising GHG concentrations

Source: Abanades García et al. (2007), p. 5.

Available cost estimates of mitigation for Spain (see Labandeira and Rodríguez, 2004) point to the efficiency of early and continued action versus delayed and sudden cuts in GHG emissions. In their simulation for Spain, using a static applied general equilibrium model, the above mentioned authors find that annual reductions in GHG emissions of less than 6% would imply drops in GDP of less than 0.5% yearly. Although the figure is significant, especially with the current economic outlook, it is judged to be manageable compared to more drastic cuts (eg, a 16% cut in annual GHG emissions leading to drops in GDP of over 1.6% yearly).

On a global scale, the cost of meeting the KP’s goals in the first commitment period (2008-12) with emission-trading between Annex-B countries[18] will be lower than the range given by the previous IPCC report (the TAR), which expected GDP losses of between 0.1% and 1.1% in 2010. Other estimates endorsed by the Ministry of the Environment in the past estimated the cost of meeting Kyoto for Spain at between €500 million and €1,000 million annually. The cost of meeting our Kyoto Protocol target is significant, but less than 0.1% of Spain’s then expected GDP for 2010 (Philp, 2004). There have, however, been higher estimates of up to €3,800 million annually (Carvajal et al. , 2004).

Mitigation can be achieved both by internal measures (national GHG reduction measures plus the use of carbon sinks) and by the use of the KP’s flexibility mechanisms (Clean Development Mechanism, Joint Implementation and Emissions Trading System). As described by Abanades García et al., (2007), along with the National Allocation Plan 2008-12, in which emission rights were assigned to those sectors allowed to participate in the ETS (ie, those that were contemplated in Directive 2003/87/CE), other measures are ongoing to ensure Spain meets its KP goal. The measures and emissions reduction targets include:

- Using flexibility mechanisms by the government and the private sector. The government is expected to buy carbon credits in the global market to cover 31.8 MTCO2-eq per year. The private sector receives a limited amount of credits equal to 26.1 MTCO2-eq per annum.

- Carbon sinks are an additional tool to meet our GHG reduction goals and are expected to be able to capture 5.8 MTCO2 –eq annually.

- Using additional measures to limit GHG emissions from diffuse sectors which will mean reducing 37,6 MtCO2-eq annually.

- Plan of Urgent Measures with over 80 actions aimed at further reducing Spain’s emissions. These measures are expected to reduce our GHG emissions by up to 12.2MTCO2-eq per year

- Autonomous communities are expected to further cooperate in implementing regional and local measures in order to meet our KP goal. The expected reduction of these measures is 15.03MTCO2-eq annually.

The Spanish Climate Change and Clean Energy Strategy[19](part of Spain’s recently approved Sustainable Development Strategy) describes actions that are being implemented and planned plus indicators that will help monitor future progress. The strategy divides these actions into the climate change response and actions directed specifically towards promoting cleaner energy and improving energy efficiency. The main goals of this strategy include a further reduction of GHG emissions in order to help us achieve our KP targets, increasing carbon sinks and promoting R&D. Within the climate change actions being developed, the Spanish Climate Change and Clean Energy Strategy describes the main initiatives in energy consumption. These are summarised in Table 4.

Table 4. Examples of energy efficiency initiatives: goals, emission reductions and government investment

Source: MMA (2007).

In Spain the National Allocation Plan[22] (NAP) for the KP’s first commitment period maintains the burden sharing effort between the sectors[23] that are allowed to participate in the ETS and the other sectors. The annual amount of emission permits assigned to the sectors allowed to participate in the ETS is equal to 152,673 million tonnes, which are allocated for free.[24] This implies a 16% reduction with regards to the previous NAP (2005-07). The main goal of the current NAP is to help achieve the KP objective, to preserve Spain’s competitiveness and employment and to ensure economic and budgetary stability.

Within the remaining flexibility mechanisms, the CDM is considered a priority for Spain and particularly so in Latin America, where Spain is promoting projects to boost renewable energy development. Although the basic goal is to reduce GHG emissions within our national boundaries, the CDM is seen as an efficient facilitator to lead to a low carbon future and as a way of promoting growth in developing countries that host these projects. Table 5 below illustrates the main CDM programmes in which Spain is participating.

Table 5. CDM projects and carbon funds

A further strategic area for Spain in the climate change challenge is its involvement in international cooperation projects. One of the most significant landmarks in this area was the development of the Latin American Network of Climate Change Offices[29] as well as the Latin American programme on Impacts, Vulnerability and Adaptation to Climate Change.[30] The main goals of these initiatives have been to provide assistance in understanding the potential threats of climate change for Latin American countries as well as the development of strategies for dealing with it. Additional initiatives including bilateral climate change agreements included the Araucaria XXI programme to promote sustainable development in Latin America, reforestation projects in Latin America and Spanish cooperation programmes in the Mediterranean basin, among others.

With regards to multilateral aid, Spain has also contributed to projects designed to help developing countries adapt to climate change, foster technology transfer initiatives, help with the integration of developing countries in the global carbon markets and participate in CDM projects. Spain’s efforts in this area have included the contribution of more than €9 million in various projects, including the Carbon Finance Assist initiative, the UNDP-UNEP initiative (mainly directed to African and Latin American countries), the Fund for Less Developed Countries and the Special Fund for Climate Change. According to the former Ministry of the Environment, an estimate of the overall cost of using the flexibility mechanisms will range from €445 million to €613 million per year.

Efficient actions towards limiting GHG emissions will also bring about ancillary benefits, that again are hard to quantify. These benefits might well partially offset some of the GHG mitigation costs (IPCC, 2007). Co-benefits include improvements in air quality, that will reduce respiratory diseases, the reduction in Spain’s energy dependence, increases in competitiveness for those firms that innovate in the renewable energy sector and the creation of new employment niches. The agricultural sector and the tertiary sector are both expected to reap the economic opportunities brought about by an economy which is less carbon intensive.

Some climate change, as we have seen, is already under way. No matter how much we reduce GHG emissions in the future, we will suffer the damages resulting from past emissions, ie, from past inaction. Vulnerability to climate change depends on the level of exposure, sensitivity and adaptability (IPCC, 2007). Adaptation is a damage minimising strategy that has been used throughout human history, and more realistic projections include this behaviour in their analyses. Adaptation has come to the forefront of international climate talks and will remain among the higher priorities on the climate policy agenda as the consequences and damages of climate change become increasingly visible.

Global warming will hit poorer people the hardest, affecting those that are already under stress due to floods, droughts, food shortage and diseases, among others. Helping vulnerable people to adapt is an issue of inter- and intra-generational equity that is on the table.[31] As necessary and inevitable as adaptation strategies might be, they will not be able to cope with the consequences of unlimited GHG emissions. Designing a balanced and efficient mix of mitigation and adaptation efforts is therefore the best strategy to deal with global warming. Equity considerations in adaptation strategies are therefore of paramount importance. Asymmetric responsibilities in past emissions provide strong arguments to advocate for transferring funds from developed to developing countries.

Stern (2008) suggests that funds to ensure aid could be raised by auctioning emission permits rather than allocating them for free among polluters allowed to participate in ETS. Even though this might be attractive in theory (in that an approach that ensures that a polluter pays can serve to improve the industry’s public image), the stakeholders’ resistance and pressures might have to be overcome in order to implement this idea. Although cost estimates for adaptation remain very uncertain, the UNFCCC estimates the cost of adaptation for developing countries will be between US$28 billion and US$67 billion annually by 2030. The UNDP’s estimates are higher, at around US$86 billion a year by 2015 ( ibid. ). On a global scale the main recommendations in terms of adaptation according to the IPCC are summarised in Table 6 below along with the policy framework in which adaptation will have to be integrated and the main opportunities and barriers to implementation.

Spain is among the most vulnerable countries within the EU and therefore the following part of this subsection will briefly introduce the main areas and issues within Spain’s adaptation strategy.

Spain’s planned response to adaptation has been to develop the National Adaptation Plan. The main goals of our adaptation strategy include: to provide information and guidance; to design mechanisms to cope with change that is already under way; to gather information on regional and sector-wide impacts; to determine the most pressing needs in R&D; and to include all stakeholders in the information and decision-making framework plus to evaluate the measures implemented.

The main areas in which the adaptation plan is to thrive are biodiversity, the agricultural sector, water availability, coastal areas and marine ecosystems, forests and mountain areas, the fishing sector, transport, health, tourism, energy, the insurance sector and the building industry. These sectors are the same as those analysed earlier, on the impact of climate change for Spain and, once again, the main source in the development of our adaptation strategies is Moreno et al ., (2005). A concise and insightful summary of the main adaptation strategies to be followed in Spain is presented by Abanades García et al., (2007). Accurate information on the assets at risk is lacking in many areas. Research and development efforts need to be decisively advanced. Valuation studies are still at an early stage and there is an increasing need for information if we want to allocate scarce funds optimally.

Table 6. IPCC’s selected examples of adaptation strategies by sector

Source: IPCC (2007), p. 57.

Ecosystems and biodiversity at risk are said to have limited adaptation capabilities and therefore the advice is to try to reduce the pressure exerted by activities such as construction, infrastructure development, livestock, water pollution, overfishing, etc. Designation of new protected areas plus ensuring there are enough resources to manage these areas is also recommended in order to increase ecosystem resilience.

Analysing adaptation options for water resources is considered essential for Spain. The main recommendation in order to adapt our water resources is to ensure we have adequate management systems that take into account climate change in their planning and implementation. Efficiency in the use of water and clear priority setting in the use of water resources are believed to be profitable long-term goals. For coastal areas such as the Cantabrian Sea and the Canary islands the main recommendation is to increase the weight of docks between 10% and 25% to ensure their stability. Additional measures would also entail considering vacating areas that will be flooded and building coastal defences as part of broader adaptation strategies.

With regards to agriculture, the main adaptive strategy is to tailor sowing, cultivation and harvesting to the new climate patterns. Stockbreeding is also seen as a threat to pastures and reducing its pressure to ensure higher quality grazing land is the main adaptation measure recommended in order to minimise damages. Fisheries are also expected to see declining catch numbers. Fishing businesses on the continental shelf are thus expected to take this into account in the future, diversifying their activity or relocating to other areas. Forests are also at risk of more frequent wildfires and the adaptation advice in this area is to avoid risky monocultures and to ensure adequate maintenance.

Health adaptation strategies should include early warning messages and prevention programmes for the Spanish population, especially those who are considered more vulnerable to climate-related diseases. Finally, other adaptation strategies for the energy sector, the tourism sector and the insurance industry are explored. The energy sector is encouraged to further increase its efficiency, reduce demand and promote renewable energy, provided the government encourages a stable and efficient regulatory framework. The Spanish tourism sector will inevitably see higher infrastructure deterioration in certain areas, a shift in seasonal visitors and a decrease in traditional tourist destinations and activities. To counteract this, civil engineering might alleviate infrastructure damages. Complementary services such as SPA’s or funfairs can be encouraged as an artificial and less vulnerable alternative. The environmental impacts and stakeholder opposition to these artificial options might hinder their widespread implementation. The insurance sector is expected to adapt to more adverse weather conditions through increased preventive strategies, increases in risk premiums and possible reductions in the coverage of damages.

The main criticisms to our adaptation plan as well as to Spain’s climate change strategy come from various stakeholders and NGOs. These agents believe that Spain’s response is a somewhat vague and shallow attempt to face climate change. According to these groups, Spain’s response is in need of more information, further specific measures and benchmarks against which achievements can be gauged. The specific measures suggested by these agents include: a long term and stable policy framework to ensure renewable energies are continuously incentivised; further promotion of public transport; a greater use of fiscal measures to ‘green’ production and consumption processes; the increasing the use of production standards; and ensuring climate policies permeate across all government departments. We still have a long way to go and future negotiations for the post-Kyoto era are not going to be easier.

Post-Kyoto: The New Global Deal Sir Nicholas Stern has released a policy guidance paper in which the main challenges of the Post-Kyoto era are unravelled and advice for the Copenhagen Conference of Parties (COP15) is put forth (Stern, 2008). Future efforts in the quest for a stable climate are going to be greater than those required by the Kyoto Protocol. This endeavour is expected to be significant but the positive outlook provided is that it is achievable if action is taken now. The message that a greater effort is needed first from the developed countries but soon after from the developing countries is similar to that voiced by the IPCC in 2007 and by the Stern Review in 2006. Being prepared to face forthcoming commitments is paramount if we are to ensure a bearable climate system. The present subsection will present the main ideas discussed by Stern (2008) as well as the recommendations for Spain in the post-Kyoto era.

The relevance of a stable and strong policy framework that builds on the existing institutional setting is seen to lie at the heart of effective action in the climate-change arena. Achieving environmental goals in a cost-effective manner plus taking into account how actions and policies affect different groups of people is considered fundamental if we are to ensure we all walk towards a tolerable climate scenario. Stern estimates this will require greater cuts in emissions to limit GHG concentrations to a ‘critical threshold’ of 500ppm.

At a global scale, this more stringent target will require GHG emissions to be cut by 50% by 2050 compared with 1990 levels. Developed countries are expected to reduce by 80% their GHG emissions by 2050, proving that decoupling growth and emissions is possible minimising harm to the former. This should be accompanied by wide-ranging technology transfers and the provision of adaptation funds for developing countries in order to provide them with adequate incentives to engage in GHG emission limits. Developing countries are expected to agree to binding emission cuts by 2020 if benefits of binding constraints outweigh the expected costs. These countries are to reap the benefits of CDM in terms of technology transfer and lower emission paths in the meantime. Additionally, sectors that are particularly exposed to international competition should face equivalent regulatory requirements in order to minimise carbon leakage and competitiveness concerns. On an individual basis, per capita emissions should be reduced drastically to 2 tonnes per capita. Note that Spain’s per capita emissions were 9.59 tonnes per capita in 2006 (versus 11 tonnes per capita in the EU in 2006 and countries such as the US reaching 20-25 tonnes per capita) and that current KP commitments entail a reduction in per capita terms to 7 tonnes per capita (Nieto & Santamarta, 2007).

The policy mix that has been developed world-wide to face climate change is also examined by Stern (2008).[32] Little new advice is given and further expansion of the emission trading system to cover more sectors and countries is seen as the way ahead to ensure environmental goals are met, costs of meeting our commitments are minimised and developing countries can benefit from lower emission paths. Expanding the emission trading system could reduce costs by 70%. One of the major players in the climate challenge, the US, is showing an increasing interest in the use of cap and trade emission trading schemes. The presidential candidates support the future implementation of this market-based instrument and thus it is highly likely that we will see a US scheme in the near future.

Additional market mechanisms that put a price on carbon emissions and more traditional command and control policies are also considered in the mix. The weight and implementation of these tools will depend on the specific conditions of the country/sector analysed. International experience and success stories can help develop these tools in different settings. In order to send the correct signals to investors these tools are again expected to be implemented over the long run so that investors face stable policy frameworks and incentives. Spain is, according to MMA (2007), considering the further use of green fiscal policy measures but stakeholder resistance, coupled with the current economic outlook, might well delay or reduce the widespread development of this initiative.

On a more specific level, the report provides advice on halting deforestation. Biodiversity losses and deforestation are at present inextricably linked. Tropical rainforests hold a high percentage of the world’s remaining biodiversity and act as a global carbon sink. Deforestation is furthermore acknowledged to potentially cause over 17% of GHG emissions world-wide. Halting deforestation seems to be an attractive strategy in the struggle against global warming. All efforts in this area are welcome, but the geographical location of forests brings equity issues again to the forefront of the analysis. Less developed countries hold a wealth of species and a high percentage of remaining forests. They also have access to these resources and incentives to reduce forest cover according to immiserisation and frontier model explanations (Hanley et al., 2001). In order to provide incentives to halt deforestation, Stern (2008) advocates an annual payment of US$15 billion and extending carbon trading to fully account for forest services. It seems that time to compensate developing countries for the opportunity cost of forest preservation is here to stay and this will mean a push for international initiatives such as the Global Environmental Facility (GEF).[33]

A further step towards a low carbon future is the development, adoption and diffusion of new technology. Carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) is presented as one of the main future alternatives due to the increasing energy demand and the abundance of highly polluting coal. Safety concerns in terms of large-scale leakage and the current cost of capturing and storing carbon are the main concerns with this technology.

Renewable energy sources such as solar, wind and second generation bio fuels are considered to hold a great potential in the future global energy mix. Adequate incentives can ensure that countries like Spain retain a significant share of the renewable pie. Spain’s climate makes it one of the best locations for investing in renewables. This value is demonstrated and captured by our energy companies who have thrived in this competitive field. We are the second-largest wind energy producer, with our energy companies leading the wind power market world-wide. Solar power is also a blooming business in Spain. In 2007 we were second in Europe in the use of solar power. These energy sources are believed to be able to reduce GHG emissions by 10GT by 2030. This is a significant amount given that in 2005 world-wide emissions were estimated at 45GT and the goal proposed by Stern (2008) is to emit 20GT by 2050 and to halve that figure in the following decades in order to stabilise GHG emissions.

The final milestone is the institutional setting in which the post-Kyoto agreement will develop. In the absence of a World Environmental Organisation, agreements will happen under the auspices and using the research potential of various institutions such as the UNFCCC, UNEP, the IPCC, the EEA, NGO’s, universities, etc. The scope and depth of climate change could, however, lead to the development of an ‘International Climate Change Organisation’ (Stern, 2008). In any case, no matter the exact setting in which future climate plans thrive, the fundamental goal seems to be to ensure the provision of a stable, proactive, flexible and efficient setting for action.

IPCC experts agree that citizen involvement in all the above mentioned initiatives can contribute to meeting climate change goals (IPCC, 2007). For Spain, the good news in this area comes from the survey conducted by the Centre for Sociological Research ( CIS in its Spanish acronym) in November 2007. According to the results obtained in this survey the majority of the people in Spain would be willing to change their lifestyle and habits if this can help fight climate change. These changes may come from choosing energy providers with greater investments in renewables, walking and using bicycles for short distances, using public transport whenever this option is feasible, keeping car tyres properly inflated, buying energy efficient appliances, separating waste so it can be adequately recycled, buying local products, etc. Warm glow effects and other biases aside, whether these intentions are good predictors of behaviour remains to be seen especially if we have to pay extra for it. Further efforts to inform, involve people and remind us all of how we can contribute to climate change mitigation in our daily activities are, according to the available data, beneficial strategies in the medium and long term.

Conclusions

Climate change is unequivocal and existing scientific consensus points towards the need to curb global warming if we want to minimise the possibility of dangerous interference with the climate system. The currently available data point to broadly comparable estimates of costs and benefits of mitigation, but according to the IPCC we do not as of yet have unambiguous emission pathways for which benefits will outweigh costs. It is, however, important to note that the longer mitigation decisions are postponed, the higher the damages of climate change. Thus, minimising maximum losses will in all likelihood imply acting sooner rather than later.

Spain’s geographical location and some of our most important economic activities, such as tourism and the building sector, are particularly sensitive to temperature increases, sea level rises and more frequent extreme weather events. Our international commitments in the fight against global warming plus our vulnerability are strong incentives to act. Mitigation strategies for Spain are seen not only as a liability but as an opportunity. These opportunities include reducing our energy dependence through our thriving renewable energy sector, reaping co-benefits through cleaner air and reduced health hazards, improving land use planning, etc.

Emission trends until 2006 have been coupled with economic growth and thus the gap between our KP commitment and our GHG emission reductions has grown. In order to close this gap Spain has developed and is implementing various measures within its national boundaries. Within Spain’s Sustainable Development Strategy, Spain’s Climate Change and Clean Energy Strategy was presented along with some of its salient measures and plans. These measures include, among others, the Action Plan for Energy Saving and Energy efficiency (E4), the Technical Building Code, the Plan for Renewable Energies and the promotion of carbon sinks through reforestation initiatives. Additionally, the use of KP’s flexibility mechanisms, especially through the ETS and the CDM, are seen as vital in the quest for a low carbon future. The costs and benefits of the policies implemented are to date uncertain although the available figures have been provided by official estimates and academic publications.

Mitigation and adaptation strategies are complementary and choosing only one of them would come at a great cost for the environment and for socio-economic structures. Some climate change is, however, unavoidable and adaptation strategies are increasingly important in order to minimise the most damaging consequences of global warming. Spain should be particularly mindful of the developments in this area as it is one of the most vulnerable countries to climate change within the EU. The advancement of the National Adaptation Plan is the first planned move in this area. Further analysis of the potential economic, social and environmental costs and benefits of these actions will help us engage in efficient strategies avoiding piecemeal and expensive maladaptation.

The remaining challenges are to effectively reduce GHG emissions, making sure there is a long term decoupling of Spain’s economic growth and its emissions. Citizens seem, theoretically at least, willing to act. Incentives for firms, further R&D, stable policies securing our leadership in renewable energies and horizontal wholehearted involvement of institutions could be the way forward in the winding road to Spain’s Kyoto goals.

Lara Lázaro-Touza London School of Economics

Abanades García, J.C., et al. , (2007), ‘El cambio climático en España. Estado de situación. Documento resumen. Noviembre de 2007’, http://www.programaagua.org/secciones/cambio_climatico/pdf/ad_hoc_resumen.pdf .

Ayala-Carcedo, F. (2004), ‘ La realidad del cambio climático en España y sus principales impactos ecológicos y socioeconómicos’, http://ram.meteored.com/numero21/cambioclimatico.asp

Carvajal, A., J. Toribio & F. Arlandis (Dir.) (2004), ‘Efectos de la aplicación del Protocolo de Kioto en la economía española’, PriceWaterhouseCoopers España.

Convery, F.J., & L. Redmond (2004), ‘Allocating Allowances in Transfrontier Emissions Trading – A Note on the European Emissions Trading Scheme (EETS)’, Asociación Hispano Portuguesa de Economía de los Recursos Naturales y Ambientales (AERNA),Vigo.

EEA (2007), ‘Climate Change: The Cost of Inaction and the Cost of Adaptation. Technical Report 13/2007’, http://reports.eea.europa.eu/technical_report_2007_13/en/Tech_report_13_2007.pdf .

Hanley, N., et al., (2001), Introduction to Environmental Economics , Oxford University Press.

IPCC (2007), ‘Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report’, http://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar4/syr/ar4_syr.pdf

http://ec.europa.eu/environment/climat/pdf/ia_sec_8.pdf

http://unfccc.int/files/meetings/cop_13/application/pdf/cp_bali_action.pdf

http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/convkp/kpeng.pdf

http://www.aeeolica.org

http://www.cbd.int/convention/convention.shtml

http://www.cne.es/cne/doc/legislacion/RD1370_2006-PNA(1).pdf

http://www.energias-renovables.com

http://www.ine.es/jaxi/tabla.do

http://www.ine.es/prensa/np486.pdf

http://www.meteored.com/ram/1477/la-realidad-del-cambio-climtico-en-espaa- y-sus-principales-impactos-ecolgicos-y-socioeconmicos/

Labandeira, X., & M. Rodríguez (2004), ‘The Effects of a Sudden CO2 Reduction in Spain’, Documento de Traballo, nr 0408.

Lázaro Touza, L. (2007), ‘Climate Change: Cherry-picking Alarmists or Time to Eat at the Table?’, ARI, nr 72/2007, Elcano Royal Institute, https://www.realinstitutoelcano.org/rielcano_eng/Content?WCM_GLOBAL_ CONTEXT=/Elcano_in/Zonas_in/International+Economy/ARI+72-2007

Lázaro Touza, L. (2008), ‘Climate Change: Policy Mix for a Brave New Kyoto?’, ARI, 12/2008, Elcano Royal Institute, https://www.realinstitutoelcano.org/rielcano_eng/Content?WCM_GLOBAL_ CONTEXT=/Elcano_in/Zonas_in/International+Economy/ARI12-2008

MMA (2006) Medio Ambiente en España 2006. Available on-line at: http://www.mma.es/secciones/info_estadistica_ambiental/estadisticas_info/ memorias/2006/pdf/mem06_3_1_1_cambioclimatico.pdf

MMA (2007), ‘Estrategia española de cambio climático y energía limpia’, http://www.mma.es/portal/secciones/cambio_climatico/documentacion_cc/ estrategia_cc/pdf/est_cc_energ_limp.pdf

MMA (2008), ‘Primer barómetro CIS sobre medio ambiente. Los españoles están dispuestos a modificar sus hábitos para luchar contra el cambio climático’, Ambienta , January, p. 42-47.

Martín Vide, J. (Coord.) (2007), Aspectos económicos del cambio climático en España , Estudios Caixa Catalunya, http://www.caixacatalunya.es/caixacat/es/ccpublic/particulars/publica/pdf/estudi04.pdf

Moreno, J.M. (Dir.) (2005), Evaluación Preliminar de los Impactos en España por Efecto del Cambio Climático. Proyecto ECCE – Informe Final , MMA and UCLM, http://www.mma.es/portal/en/secciones/cambio_climatico/areas_tematicas/ impactos_cc/pdf/evaluacion_preliminar_impactos_completo_2.pdf

Nieto, J., & J. Santamarta, (2007), ‘Evolución de las emisiones de gases de efecto invernadero en España 1990-2006’, http://www.cincodias.com/5diasmedia/cincodias/media/200704/17/economia/ 20070417cdscdseco_1.Pes.PDF.pdf

Pearce, D. (2004), ‘Environmental Market Creation: Saviour or Oversell?’, Portuguese Economic Journal , p. 115-144.

Philp, L. (2004), ‘Pero, de verdad, ¿cuánto cuesta Kioto?’, Ambienta , July, p. 26-33.

Rodríguez Ruiz, J., & A. Martínez Palacio (2008), ‘Energía eólica marina: una solución a considerar para un abastecimiento energético sostenible’, Ambienta , March, p. 52-55.

Stern, N., et al., (2006), ‘Stern Review: The Economics of Climate Change’, http://www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/independent_reviews/stern_review_economics_climate _change/stern_review_report.cfm

Stern, N. (2008), ‘Key Elements of a Global Deal on Climate Change’, http://www.lse.ac.uk/collections/climateNetwork/publications/KeyElements OfAGlobalDeal_30Apr08.pdf

UN (1992), ‘United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change’, http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/convkp/conveng.pdf

World Bank (2007), ‘Carbon Finance for Sustainable Development’.

[1] UNFCCC is the acronym for United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

[2] Ppm means parts per million.

[3] For additional information see Lara Lázaro (2007), ‘Climate Change: Cherry-picking Alarmists or Time to Eat at the Table?’, ARI nr 72/2007, Elcano Royal Institute.

[4] For a limited temperature increase (2-3ºC).

[5] To the author’s knowledge.

[6] IPCC (4AR) is the acronym for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Fourth Assessment Report.

[7] CSIC is the Spanish acronym for Higher Scientific Research Centre.

[8] Data updated by Spain’s National Statistics Institute (INE inits Spanish acronym) on 20 December 2007.

[9] The PESETA project is devoted to developing projections of the economic impact of climate change in sectors of Europe based on a bottom-up analysis.

[10] According to EEA (2007, p. 18), 1tC = 3.664tCO2, so a value of 100GBP/tC would be equivalent to GBP27/tCO2.

[11] Defined as the global discounted net economic damages of emitting GHG.

[12] Current references on the latest estimates, although partial and uncertain, are in http://www.ingurumena.ejgv.euskadi.net/r49-435/es/contenidos/nota_prensa/markandya/es_prensa/indice.html (for estimates of the cost of climate change in Bilbao) and the PESETA project ( http://peseta.jrc.es/index.htm ).

[13] The Spanish acronym is OECC ( Oficina Española de Cambio Climático ).

[14] The Spanish acronym is CNC ( Consejo Nacional del Clima ).

[15] The Spanish acronym is CCPCC ( Comisión de Coordinación de Políticas de Cambio Climático ).

[16] The Spanish acronym is GICC ( Grupo Interministerial de Cambio Climático ).

[17] For further information on the specific goals and tasks of the above institutions see www.mma.es .

[18] Which according to the KP include: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, the European Community, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Monaco, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, the Russian Federation, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Ukraine, the UK and the US (see http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/convkp/kpeng.pdf ).

[19] Estrategia Española de Cambio Climático y Energía Limpia ( EECCEL ).

[20] Not Available.

[21] According to Abanades García et al. (2007) thebreakdown of the contribution of the different energy sources to Spain’s energy demand in 2006 was: 48.5% oil, 20.8% gas, 14.4% coal, 10.3% nuclear energy and 5.9% renewable energy.

[22] http://www.cne.es/cne/doc/legislacion/RD1370_2006-PNA(1).pdf .

[23] These currently include the refinery sector, iron and steel, cement and lime, ceramic industry, glass, paper and cardboard.

[24] This free allocation will apply in principle to all permits distributed. Auctioning may only be considered for those permits that are reserved to new entrants to the market.

[25] ADC is the acronym for Andean Development Corporation( CAF Corporación Andina de Fomento ).

[26] LCI is the acronym for Latin American Carbon Initiative(ICC Iniciativa Iberoamericana de carbono ).

[27] EIB is the acronym for European Investment Bank.

[28] EBRD is the acronym for European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

[29] Red Iberoamericanas de Cambio Climático.

[30] Programa Iberoamericano de Impactos, Vulnerabilidad y Adaptación al Cambio Climático.

[31] See IPCC (2007), Stern (2006) and the main conclusions and recommendations agreed at the Bali conference in December 2007 which resulted in the Bali Roadmap: http://unfccc.int/files/meetings/cop_13/application/pdf/cp_bali_action.pdf .

[32] See, for example, Lara Lázaro (2008), ‘Climate Change: Policy Mix for a Brave New Kyoto?’, ARI nr 12/2008, Elcano Royal Institute.

[33] For an insightful analysis of market creation initiatives to preserve environmental assets see Pearce (2004).

Cuale River after Hurricane Lidia in Puerto Vallarta, Mexico

New Initiative Based at YSE Provides Timely Climate News in Spanish

A news site launched by Yale Climate Connections, YCC En Español, is providing coverage in Spanish of climate change and extreme weather events to Latino and Hispanic communities.

In October, when Tropical Storm Max and Hurricane Lidia, a Category 4 storm with sustained winds of 140 mph, were both bearing down on Mexico’s southern Pacific Coast within 48 hours of each other, YCC En Español, an initiative of Yale Climate Connections at the Yale School of the Environment, provided news and information about resources to residents in the path of the storms. Several weeks later, YCC En Español , also reported on Hurricane Otis, which made landfall near Acapulco at Category 5 intensity, and, last spring, the site covered Hurricane Hilary, the first tropical storm to directly hit San Diego in nearly a century.

The Spanish news stories are part of a new initiative by YCC to provide news and information on climate issues to Hispanic and Latino communities. YCC launched YCC En Español in September 2022 with the goal of publishing 30 articles and conducting 10 digital campaigns in Spanish to attract 100,000 pageviews to its news hub by the end of 2023. It has since published 90 articles, conducted 43 digital advertising campaigns on Facebook and Google alerting Spanish-speakers to storms and other severe weather events and garnered more than 500,000 page views.

“The project and demand for our content far exceeded our expectations,” said Pearl Marvell, features editor at YCC En Español. “Altogether, our articles received over 530,000 pageviews, more than five times our goal. Most importantly, an audience survey we conducted this fall found that the project has impact. A majority of respondents reported that our Spanish-language articles inspired them to take action on climate change and prepare for extreme weather.”

The initiative grew out of studies conducted by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication (YPCCC) that gauge concern about climate change across age, race/ ethnicity and gender. The studies found that a majority of Hispanic and Latino adults (64%) in the U.S. are concerned about global warming and are more likely to be “Alarmed” or “Concerned” than white adults. A recent YPCCC study also found that residents of Puerto Rico are among the most worried about climate change in the world.

“Latinos are one of the fastest growing demographics in the U.S., with a growing influence in American politics, economics, and culture. Our research has found that Latinos in the U.S. are very engaged with the issue of climate change. They are more likely to know it is happening and that it is human caused. They are more worried about it, more supportive of climate policies, and are willing to get personally involved,” said Anthony Leiserowitz, director of YPCCC and YSE senior research scientist. “And interestingly, primarily Spanish-speaking Latinos are even more engaged with the issue than English-speaking Latinos.”