McCombs School of Business

- Español ( Spanish )

Videos Concepts Unwrapped View All 36 short illustrated videos explain behavioral ethics concepts and basic ethics principles. Concepts Unwrapped: Sports Edition View All 10 short videos introduce athletes to behavioral ethics concepts. Ethics Defined (Glossary) View All 58 animated videos - 1 to 2 minutes each - define key ethics terms and concepts. Ethics in Focus View All One-of-a-kind videos highlight the ethical aspects of current and historical subjects. Giving Voice To Values View All Eight short videos present the 7 principles of values-driven leadership from Gentile's Giving Voice to Values. In It To Win View All A documentary and six short videos reveal the behavioral ethics biases in super-lobbyist Jack Abramoff's story. Scandals Illustrated View All 30 videos - one minute each - introduce newsworthy scandals with ethical insights and case studies. Video Series

Ethics Defined UT Star Icon

Moral Philosophy

Moral Philosophy studies what is right and wrong, and related philosophical issues.

Moral philosophy is the branch of philosophy that contemplates what is right and wrong. It explores the nature of morality and examines how people should live their lives in relation to others.

Moral philosophy has three branches.

One branch, meta-ethics , investigates big picture questions such as, “What is morality?” “What is justice?” “Is there truth?” and “How can I justify my beliefs as better than conflicting beliefs held by others?”

Another branch of moral philosophy is normative ethics . It answers the question of what we ought to do. Normative ethics focuses on providing a framework for deciding what is right and wrong. Three common frameworks are deontology, utilitarianism, and virtue ethics.

The last branch is applied ethics . It addresses specific, practical issues of moral importance such as war and capital punishment. Applied ethics also tackles specific moral challenges that people face daily, such as whether they should lie to help a friend or co-worker.

So, whether our moral focus is big picture questions, a practical framework, or applied to specific dilemmas, moral philosophy can provide the tools we need to examine and live an ethical life.

Related Terms

Consequentialism

Consequentialism is an ethical theory that judges an action’s moral correctness by its consequences.

Deontology is an ethical theory that uses rules to discern the moral course of action.

Hedonism is a form of consequentialism that approves of actions that produce pleasure and avoid pain.

Utilitarianism

Utilitarianism is an ethical theory that asserts that right and wrong are best determined by focusing on outcomes of actions and choices.

Virtue Ethics

Virtue Ethics is a normative philosophical approach that urges people to live a moral life by cultivating virtuous habits.

Stay Informed

Support our work.

Moral Dilemma and Ethics: Moral Philosophy Essay

Individuals frequently face moral dilemmas in life, forcing them to make choices beyond their moral convictions and other commitments. The divine command and natural law ethics are the two main perspectives on how people can use their freedom to make decisions (Ben-Menahem & Ben-Menahem, 2020). The first holds that since God created the world knowing what would be best for people, humans must slavishly obey the divine laws and commandments. It is entirely objective to determine if anything is right or bad: It is right if God mandates it, and it is wrong if God prohibits it (Rachels & Rachels, 2015). According to natural law ethics, God created everything in the world with a purpose, which has the ultimate goal – to achieve good for man. Therefore, people can make decisions on their own, based on the principle that the main thing is to achieve the best result.

If I were in the described situation as a nurse, I would mainly follow the laws. In case there is a need to get parental consent for a blood transfusion, then I would not do it without such a document. Natural law ethics would say that morally right and good is what contribute to the prosperity of humankind, therefore, it is necessary to save human life. If everything is in order with the legal side and the only question is a moral choice, I would do everything to save the child. The parents’ beliefs are their business, the child is not the parent’s property, and the main thing is their life. I agree with what a natural law ethicist would say because the doctor knows the ultimate objective – saving a life and can take measures to achieve the goal.

The divine command ethicist in this situation would say not to do a blood transfusion because God forbids it. I disagree with this point of view, even if it contradicts the parents’ beliefs, because even from the religious side, a person has a value, and one must fight for life. An emotivist would say that my decision is based on the fact that I do not like members of religious groups. I do not like it when people die because, according to this theory, there is no morality – only an individual assessment of the situation. In ethics, subjectivity unquestionably plays a significant role because, when faced with a moral choice, people make their own decisions.

Ben-Menahem, H., & Ben-Menahem, Y. (2020). The rule of law: Natural, human, and divine. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, 81, 46–54.

Rachels, J., & Rachels, S. (2015). The Elements of Moral Philosophy . McGraw-Hill Europe.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, February 28). Moral Dilemma and Ethics: Moral Philosophy. https://ivypanda.com/essays/moral-dilemma-and-ethics-moral-philosophy/

"Moral Dilemma and Ethics: Moral Philosophy." IvyPanda , 28 Feb. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/moral-dilemma-and-ethics-moral-philosophy/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'Moral Dilemma and Ethics: Moral Philosophy'. 28 February.

IvyPanda . 2024. "Moral Dilemma and Ethics: Moral Philosophy." February 28, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/moral-dilemma-and-ethics-moral-philosophy/.

1. IvyPanda . "Moral Dilemma and Ethics: Moral Philosophy." February 28, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/moral-dilemma-and-ethics-moral-philosophy/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Moral Dilemma and Ethics: Moral Philosophy." February 28, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/moral-dilemma-and-ethics-moral-philosophy/.

- The importance of religion in eitheror

- Drug-Testing: Utilitarian Theory Ethical Dilemma

- Practical Ethics: Connie Case

- Opposing Views on Mandatory Vaccination

- Ester Hernandez’s Picture “Sun Mad Raisins”

- Blood Transfusion Code of Ethics

- The Hemolytic Transfusion Reactions

- Blood Transfusion and Blood Banks Development

- Reducing the Risk of Transfusion Transmission of Zika

- Blood Transfusion: Benefits and Risk Factors

- The Examined Life Film Reaction

- Moral Virtue and Its Relation to Happiness

- Life Meaning From Humanist and Other Perspectives

- Studying Philosophy: What Are the Main Benefits?

- Anger: Philosophical Perspective

1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

Philosophy, One Thousand Words at a Time

Virtue Ethics

Author: David Merry Category: Ethics , Historical Philosophy Word Count: 1000

Listen here

Think of the (morally) best person you know. It could be a friend, parent, teacher, religious leader, thinker, or activist.

The person you thought of is probably kind, brave, and wise. They are probably not greedy, cruel, or foolish.

The first list of ‘character traits’ ( kind, brave, etc.) are virtues, and the second list ( arrogant, greedy, etc.) are vices . Virtues are ways in which people are good; vices are ways in which people are bad.

This essay presents virtue ethics, a theory that sees virtues and vices as central to understanding who we should be, and what we should do.

1. Virtue and Happiness

Virtues are excellent traits of character. [1] They shape how we act, think, and feel. They make us who we are. Virtues are acquired through good habits, over a long period of time.

1.1. Eudaimonia

According to Aristotle (384-322 BCE) virtues are those, and only those, character traits we need to be happy. [2] Many virtue ethicists today agree. [3] These virtue ethicists are called eudaimonists, after the Greek word eudaimonia, usually translated as “happiness,” “flourishing,” or “well-being . ” [4]

For eudaimonists, happiness is more than a feeling: it involves living well with others and pursuing worthwhile goals. This includes cultivating strong relationships, and succeeding at such projects as raising a family, fighting for justice, and (moderate yet enthusiastic) enjoyment of pleasure. [5]

Eudaimonists believe our happiness is not easily separated from that of other people. Many would consider the happiness of their friends and family as part of their own. Eudaimonists may extend this to complete strangers, and non-human animals. Similarly for causes or ideals: eudaimonists believe complicity in injustice and deceit reduces a person’s happiness. , [6]

If eudaimonists are right about happiness, then it is plausible that we need virtues such as honesty, kindness, gratitude and justice to be happy. This is not to say that the virtues will guarantee happiness. But eudaimonists believe we cannot be truly happy without them.

One concern is that vicious people often seem happy. For example, dictators live in palaces, apparently rather pleasantly. Eudaimonists may not think this amounts to happiness, but many would disagree. And if dictators can be happy, then we certainly can be happy without the virtues. Answering this objection is an ongoing project for eudaimonists. [7]

1.2. Emotion, Intelligence, and Developing Virtue

Eudaimonists believe emotions are essential to happiness, and that our emotions are shaped by our habits. Good emotional habits are a question of balance.

For example, eudaimonists argue that honest people habitually want to and enjoy telling the truth, but not so much that they will ignore all other considerations–a habit of enjoying pointing out other people’s shortcomings will leave us friendless, and so is not part of honesty. [8]

Because virtue requires balancing competing considerations, such as telling the truth and considering other people’s feelings, virtue also requires experience in making moral decisions. Virtue ethicists call this intellectual ability practical intelligence, or wisdom. [9]

2. Virtue and Right Action

Virtue ethicists believe we can use virtue to understand how we should act, or what makes actions right.

According to some virtue ethicists, an action is right if, and only if, it is what a virtuous person would characteristically do under the circumstances. [10] On rare occasions, virtuous people do the wrong thing. But this is not acting characteristically.

2.1. Being Specific

“Do what virtuous people would do” is not very specific, and we may be left wondering what the theory is actually saying we should do.

One way to make it more specific is to generate rules for each of the virtues and vices, called “v-rules.” Two examples of v-rules are: be kind, don’t be cruel. The v-rules give specific guidance in many cases: writing an email just to hurt someone’s feelings is cruel, so don’t do it. [11]

Unfortunately, the virtues can conflict: if a friend asks whether we like their new partner, it may be more honest to say we do not , but kinder to say we do. In this case it is hard to say what the virtuous person would do.

Virtue ethicists might respond that other ethical theories will also struggle to give clear guidance in hard cases. [12]

Second, they might try to understand how a virtuous person would think about the situation. Remember that virtuous people have practical intelligence, and habitually care about other people’s happiness and telling the truth. So they may consider a lot of particular details, including how close the friendship is, how bad the partner is, how gently the friend may be told. [13]

This may not provide a specific answer, but virtue ethicists hope they can at least provide a helpful model for thinking about hard cases. [14]

2.2. Explaining Why

We have seen how virtue ethics tells us what to do. But we also want to know why we should do it.

Virtue ethicists point out that if we ask virtuous people, they will explain why they did what they did. [15] Their reasoning results from their excellent emotional habits and practical intelligence–that is, from their virtue. And if we want to be happy, we need to cultivate virtue. So these should be our reasons too.

But in explaining their decision, the virtuous person won’t necessarily mention virtue. They might, for example, say, “I wanted to avoid hurting their feelings, so I told the truth gently.” [16]

It might then seem that something other than virtue–in our example, the importance of other people’s feelings–explains why the action is right . But then this other thing should be central to ethical theory, instead of virtue.

Virtue ethicists may respond that the moral weight of this other thing depends on which character traits are virtues. Accordingly, if kindness were not a virtue, there may be no moral reason to care about others’ feelings. [17]

3. Conclusion

Virtue ethicists recommend reflecting on the character traits we need to be happy. They hope this will help us make better moral decisions. Virtue ethics may not always yield clear answers, but perhaps acknowledging moral uncertainty is not a vice.

[1] Others may define virtue as admirable or merely good traits of character. For additional definitions of virtue and understandings of virtue ethics, see Hursthouse and Pettigrove’s “Virtue Ethics.”

[2] Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics , Book One, Chapter 9, Lines 1099b25-29. For this interpretation, see Nussbaum, The Fragility of Goodness, p. 6.

[3] Hursthouse, On Virtue Ethics , pp. 165-169, “Virtue Theory and Abortion”, p. 226, Foot, Natural Goodness , pp. 99-116.

There are many other accounts of virtue worth considering. One major alternative is sentimentalist accounts, such as that of Hume and Zagbzebski, who define virtues as those character traits that attract love or admiration. Some scholars argue that Confucian ethics is a virtue ethic, though this is debated: see Wong, “Chinese Ethics.” Also see John Ramsey’s Mengzi’s Moral Psychology, Part 1: The Four Moral Sprouts . For an African understanding of virtue, see Thaddeus Metz’s The African Ethic of Ubuntu .

[4] Hursthouse has a detailed and accessible discussion of the merits of different translations of eudaimonia in On Virtue Ethics, pp. 9-10.

[5] Some people find this account of virtue surprising because they think virtue must involve sacrificing one’s own happiness for the sake of other people, and living like a saint, a monk, or just being a really boring and miserable person. In this case it may be more helpful to think in terms of ‘good character’ than ‘virtue’. David Hume amusingly argued that some alleged virtues, such as humility, celibacy, silence, and solitude, were vices. See his Enquiry 9.1.

[6] The idea that injustice erodes everybody’s happiness is not to deny that it especially harms people who are treated unjustly. However, eudaimonists consider being unjust, or deceiving others to be bad for us.

[7] For a compelling discussion of this objection to eudaimonism, see Blackburn, Being Good, pp. 112-118 . Eudaimonists have been trying to answer this objection for a long time. Indeed, arguing that it is more beneficial to be just than unjust is one of the major themes of Plato’s Republic. For more recent attempts to make the case, see Hursthouse’s On Virtue Ethics, Chapter 8, or Foot, Natural Goodness, especially Chapter 7. See also Kiki Berk’s Happiness .

[8] The idea that the virtues involve finding a balance is called ‘the doctrine of the mean.’ See Nicomachean Ethics, Book II, Chapter 6, lines 1106b30-1107a5. For one contemporary account of the emotional aspects of virtue, see Hursthouse’s On Virtue Ethics, pp.108-121.

[9] Aristotle discusses practical intelligence in Nicomachean Ethics Book 6. For a contemporary account see Hursthouse’s On Virtue Ethics, pp. 59-62.

[10] Hursthouse, On Virtue Ethics, pp. 28-29. This is sometimes called a qualified-agent account. For some alternatives, see van Zyl’s “Virtue Ethics and Right Action”.

[11] Hursthouse, On Virtue Ethics, pp. 28-29.

[12] For other moral theories, see Deontology: Kantian Ethics by Andrew Chapman and Introduction to Consequentialism by Shane Gronholz. When reading, you might consider whether these theories would give you clearer guidance about your friend’s partner.

[13] See Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, Book 2, chapter 9, lines 1109a25-30. Hursthouse, On Virtue Ethics pp. 128-129.

[14] For two examples of how virtue ethics may be helpfully applied to tough moral decisions, see Hursthouse’s “Virtue Theory and Abortion”, and Foot’s “Euthanasia”.

[15] Hursthouse, “Virtue Ethics and Abortion”, especially p. 227, pp. 234-237. “Do what a virtuous person would do” is only supposed to tell us what we should do, not how we should think .

[16] This objection is discussed in Shafer-Landau’s The Fundamentals of Ethics, pp. 272-274.

[17] On this connection between facts about morality on facts about virtue and human happiness, see Hursthouse “Virtue Theory and Abortion”, pp. 236-238.

Aristotle. Nicomachean Ethics . C. 355-322 BCE. Trans. Roger Crisp. Cambridge UP. 2014.

Blackburn, S. Being Good. Oxford UP. 2001.

Boxill, B. “How Injustice Pays.” Philosophy and Public Affairs, 9(4): 359-371. 1980.

Foot, P. Natural Goodness. Oxford UP. 2001.

Foot, P. “Euthanasia”. Philosophy and Public Affairs, 6(2): 85–112. 1977.

Foot, P. “Moral Beliefs.” Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society. 59: 83-104. 1958.

Hume, An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals. 1777.

Hursthouse, R. “Virtue Theory and Abortion.” Philosophy & Public Affairs . 20(3): 223-246. 1991.

Hursthouse, R. On Virtue Ethics. Oxford UP. 1999.

Hursthouse, Rosalind and Glen Pettigrove, “Virtue Ethics”. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2018 Edition), Zalta, E.N (ed.). 2018,

Nussbaum, M. The Fragility of Goodness. Cambridge UP. 2nd Edition, 2001.

van Zyl, L. “Virtue Ethics and Right Action”. In Russell, D. C (ed.) The Cambridge Companion to Virtue Ethics. Cambridge UP. 2013.

Plato. Republic. C. 375 BCE. Trans. Paul Shorey. Harvard UP. 1969.

Shafer-Landau, R. The Fundamentals of Ethics . Fourth Edition. Oxford UP. 2017.

Wong, D. “Chinese Ethics”. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2021 Edition) . Zalta, E.N (ed). 2021.

Zagzebski, L.T. Exemplarist Moral Theory. Oxford UP. 2017.

Related Essays

Happiness by Kiki Berk

Deontology: Kantian Ethics by Andrew Chapman

Introduction to Consequentialism by Shane Gronholz

G. E. M. Anscombe’s “Modern Moral Philosophy” by Daniel Weltman

Philosophy as a Way of Life by Christine Darr

Ethical Egoism by Nathan Nobis

Why be Moral? Plato’s ‘Ring of Gyges’ Thought Experiment by Spencer Case

Situationism and Virtue Ethics by Ian Tully

Ancient Cynicism: Rejecting Civilization and Returning to Nature by G. M. Trujillo, Jr.

Mengzi’s Moral Psychology, Part 1: The Four Moral Sprouts by John Ramsey

Mengzi’s Moral Psychology, Part 2: The Cultivation Analogy by John Ramsey

The African Ethic of Ubuntu by Thaddeus Metz

PDF Download

Download this essay in PDF .

About the Author

David Merry’s research is mostly about ethics and dialectic in ancient Greek and Roman philosophy, although he also occasionally works on contemporary ethics and philosophy of medicine. He received a Ph.D. from the Humboldt University of Berlin, and an M.A in philosophy from the University of Auckland. He is co-editor of Essays on Argumentation in Antiquity . He offers interactive, discussion-based online philosophy classes and maintains a blog at Kayepos.com .

Follow 1000-Word Philosophy on Facebook and Twitter and subscribe to receive email notifications of new essays at 1000WordPhilosophy.com

Share this:, 21 thoughts on “ virtue ethics ”.

- Pingback: Philosophy as a Way of Life – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Ancient Cynicism: Rejecting Civilization and Returning to Nature – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Aristotle on Friendship: What Does It Take to Be a Good Friend? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Ursula Le Guin’s “The Ones who Walk Away from Omelas”: Would You Walk Away? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: G. E. M. Anscombe’s “Modern Moral Philosophy” – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Why be Moral? Plato’s ‘Ring of Gyges’ Thought Experiment – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Article on Virtue Ethics at 1000-Word Philosophy - Kayepos: Philosophical Capers

- Pingback: - Kayepos: Philosophical Capers

- Pingback: Online Philosophy Resources Weekly Update | Daily Nous

- Pingback: Rousseau on Human Nature: “Amour de soi” and “Amour propre” – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: What Is It To Love Someone? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Because God Says So: On Divine Command Theory – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Consequentialism and Utilitarianism – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Deontology: Kantian Ethics – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Happiness: What is it to be Happy? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Indoctrination: What is it to Indoctrinate Someone? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: The African Ethic of Ubuntu – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Situationism and Virtue Ethics – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Mengzi’s Moral Psychology, Part 2: The Cultivation Analogy – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Mengzi’s Moral Psychology, Part 1: The Four Moral Sprouts – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Is it Wrong to Believe Without Sufficient Evidence? W.K. Clifford’s “The Ethics of Belief” – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

Comments are closed.

Home — Essay Samples — Philosophy — Ethics and Moral Philosophy

Essays on Ethics and Moral Philosophy

The dangers of legalizing euthanasia, moral dilemmas faced by law enforcement officers, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

What is Integrity to You

Suitable consequences for cyberbullying, unauthorized practice of law case analysis, weaknesses of nike, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Vigilante Justice in Batman: a Complex Moral Dilemma

Thesis statement for abortion, the importance of virtue ethics, dubiski high school, get a personalized essay in under 3 hours.

Expert-written essays crafted with your exact needs in mind

Mcdonalds Code of Ethics Case Study

Swot analysis of red bull, ethical business practices: csr, employee relations, environment, moral ambiguity in the great gatsby, right vs right moral dilemmas, john stuart mills definition of war, ethical ethics of costco, analysis of fearlessness in sophocless antigone, lather and nothing else character analysis, topics in this category.

- Ethical Dilemma

- Virtue Ethics

- Ethics in Everyday Life

- Personal Ethics

- Values of Life

Popular Categories

- Philosophers

- Philosophical Movements

- Philosophical Concepts

- Philosophical Works

- Philosophical Theories

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

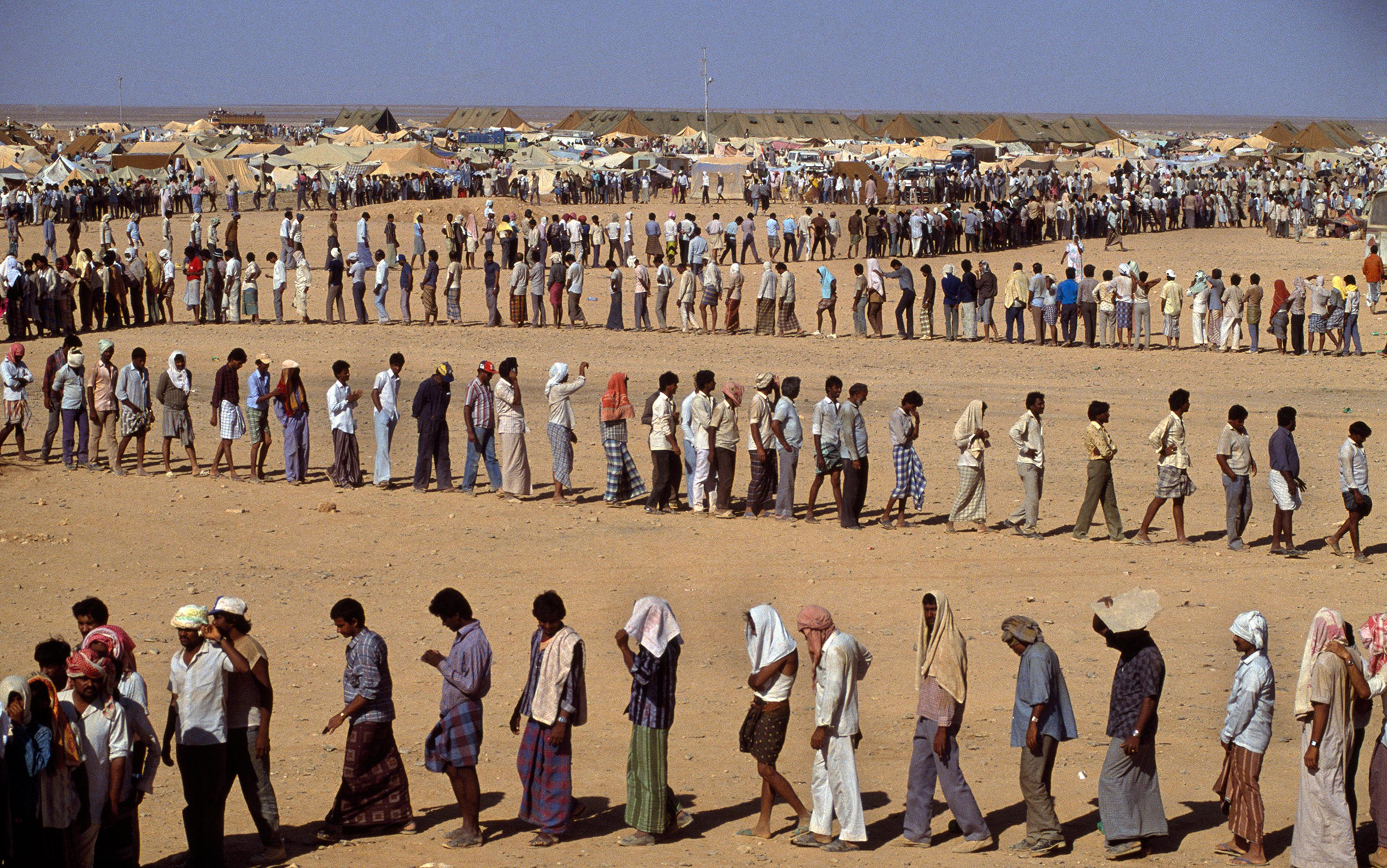

The environment

Emergency action

Could civil disobedience be morally obligatory in a society on a collision course with climate catastrophe?

Rupert Read

The scourge of lookism

It is time to take seriously the painful consequences of appearance discrimination in the workplace

Andrew Mason

The dangers of AI farming

AI could lead to new ways for people to abuse animals for financial gain. That’s why we need strong ethical guidelines

Virginie Simoneau-Gilbert & Jonathan Birch

Public health

It’s dirty work

In caring for and bearing with human suffering, hospital staff perform extreme emotional labour. Is there a better way?

Susanna Crossman

For Iris Murdoch, selfishness is a fault that can be solved by reframing the world

Sports and games

The moral risks of fandom

Players, coaches and team owners sometimes do terrible things. What, if anything, should their fans do about that?

Jake Wojtowicz & Alfred Archer

Computing and artificial intelligence

Frontier AI ethics

Generative agents will change our society in weird, wonderful and worrying ways. Can philosophy help us get a grip on them?

Space exploration

Capturing the cosmos

When self-replicating craft bring life to the far Universe, a religious cult, not science, is likely to be the driving force

History of science

The rights of the dead

From the Irish Giant to the Ancient One, is it ever ethical for scientists and museums to study bodies without permission?

Anita Guerrini

Comparative philosophy

Forging philosophy

A 17th-century classic of Ethiopian philosophy might be a fake. Does it matter, or is that just how philosophy works?

Jonathan Egid

Ethics has no foundation

Ethical values can be both objective and knowable – torture really is wrong – yet not need any foundation outside themselves

Andrew Sepielli

The final ethical frontier

Earthbound exploration was plagued with colonialism, exploitation and extraction. Can we hope to make space any different?

Philip Ball

Wrestling with relativism

Bernard Williams argued that one’s ethics is shaped by culture and history. But that doesn’t mean that everyone is right

Daniel Callcut

History of ideas

Equality without compromise

Liberal philosophy has clipped the wings of the egalitarian ideal. We should return to the bolder ideals of Iris Murdoch

Christine Sypnowich

Thinkers and theories

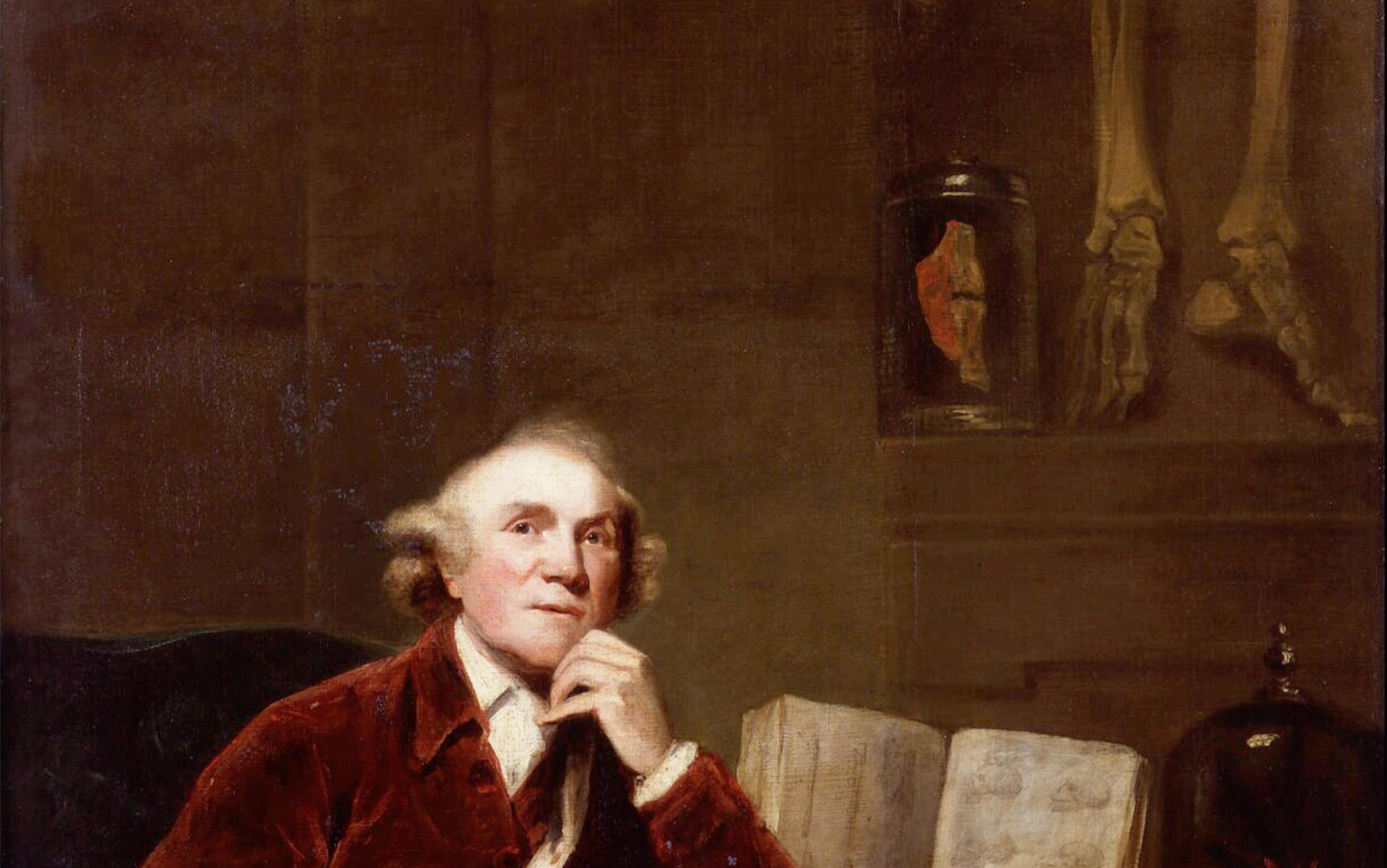

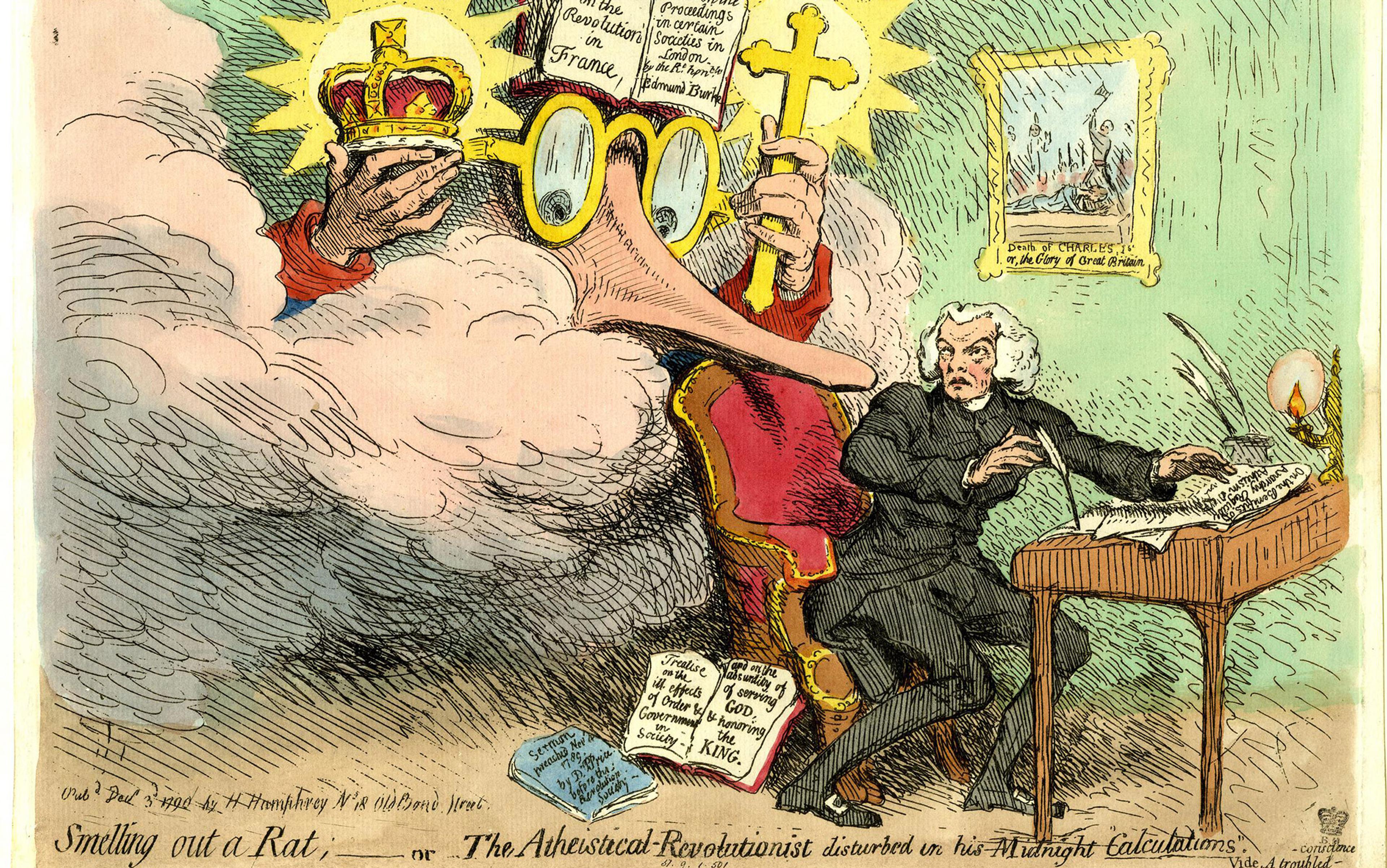

Remember Richard Price!

Demonised by the political establishment for his radical, dissenting views, this 18th-century Welsh polymath deserves better

Huw Williams

Philosophy of religion

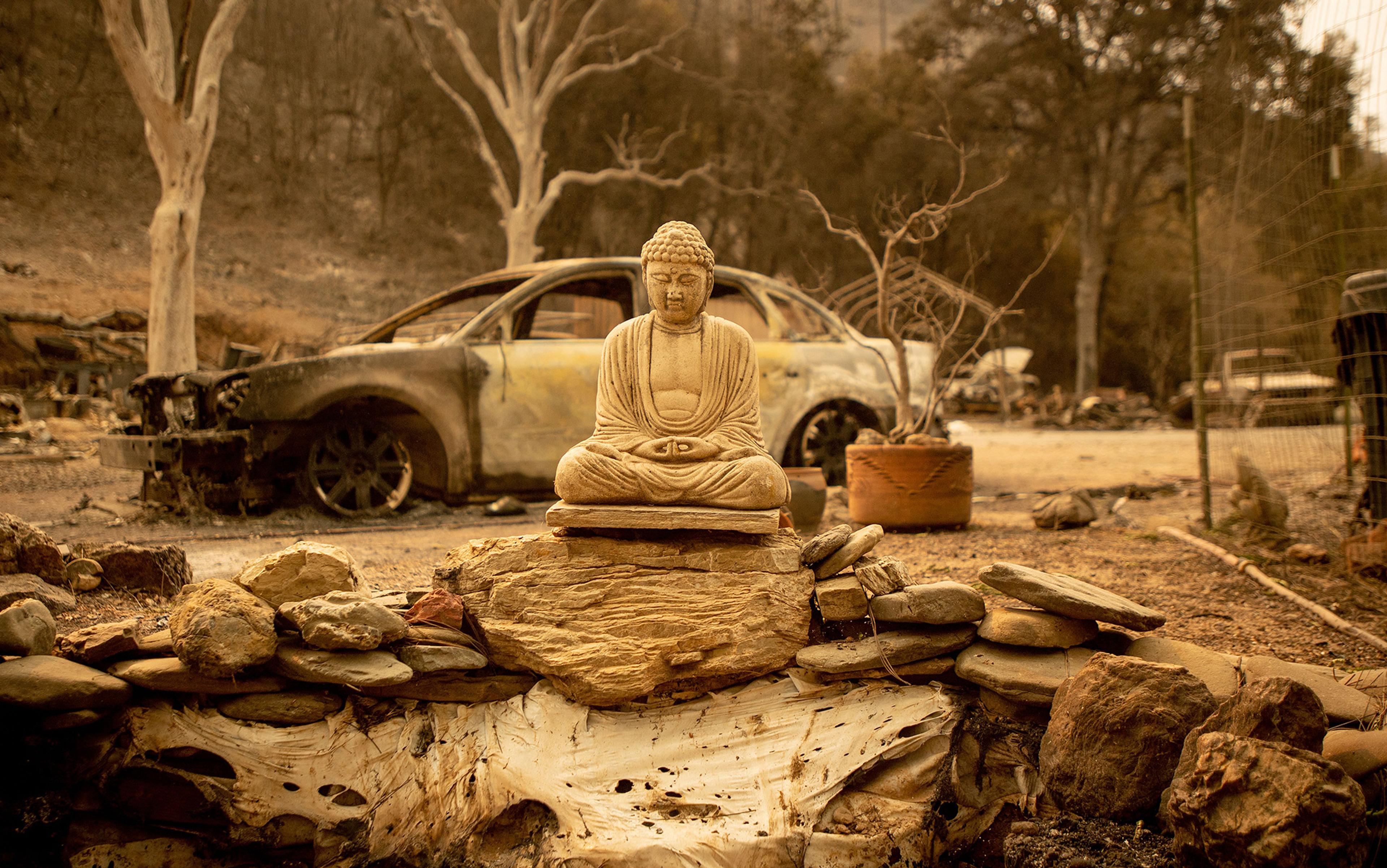

Reckoning with compassion

After an abuse scandal destroyed my Buddhist community, I had to reconsider what it means to live an ethically attuned life

Jessica Locke

Future of technology

Artificial ‘creativity’ is unstoppable. Grappling with its ethics is up to us

The ethics of human extinction

Why would it be so bad if our species came to an end? It is a question that reveals our latent values and hidden fears

Émile P Torres

If not vegan, then what?

A vegan diet can be hard to adopt, even if you’re convinced it’s the right thing to do. What are the next-best options?

Peter Godfrey-Smith

How many monkeys is it worth sacrificing to save a human life?

Human rights and justice

Thirty years after one teenager shot another, is it time to forgive?

Moral mathematics

Subjecting the problems of ethics to the cool quantifications of logic and probability can help us to be better people

The lethal act

The Buddha taught not to kill, yet his followers have at times disobeyed him. Can murderers still be Buddhists?

Martin Kovan

An animator wonders: can you ever depict someone without making them a caricature?

A Level Philosophy & Religious Studies

Applied ethics

AQA Philosophy Moral Philosophy

Applied ethics questions

You need to be ready to answer:

5 or 12 mark questions

Explanation of theory Y on applied ethics topic X.

You need to know how each of Utilitarianism, Deontology, Virtue ethics and Meta-ethical theories apply to each of the applied ethics topics: stealing, deception & the telling of lies, eating animals & simulated killing.

25 mark essay questions

For 25 mark questions on applied ethics you additionally need to be able to evaluate the judgement made on the applied ethics topics by normative/meta-ethical theories.

The question could be whether applied ethics topic X is right/wrong.

Your answer/conclusion could be:

- It is right/wrong to X

- It is not right/wrong to X

- It is sometimes right/wrong to X

Different answers/conclusions such as these will be those given by the normative/meta-ethics theories.

For example, if the question is whether stealing is wrong, Kantian deontologists would answer affirmatively that stealing is wrong.

Utilitarians would answer that it is sometimes wrong to steal.

Anti-realist meta-ethical theories

Error theory would say that all ethical statements are false. So, if the question is whether stealing is wrong, an error theorist would say no, because the statement ‘stealing is wrong’ is false. This doesn’t mean stealing is right though, that would equally be false.

Non-cognitive theories like emotivism would regard all ethical questions as meaningless expressions of emotion.

Unless the question specifies a particular normative/meta-ethical theory, it is up to you which and how many to include.

Evaluation in 25-mark questions

Once you have explained what answer to the question a normative/meta-ethical theory would give and why, the next step is to evaluate that answer.

There is no need to learn special criticisms or objections. The issues you already need to know for normative & meta-ethics work well enough.

You will have explained what answer a theory gives to the question. If you evaluate the theory, you therefore evaluate its answer to the question.

Bringing in issues can sometimes be directly related (most easily through illustration) and sometimes not.

If the question is whether stealing is wrong, Utilitarianism would say that it is sometimes wrong.

Example of an issue being used to directly relate to the applied ethics topic:

Issues with calculation can be brought in. It is difficult to predict the future, including the future consequences that could arise from stealing.

Example of an issue being used to indirectly relate to the applied ethics topic:

Nozick’s experience machine issue can be used. It attempts to undermine the foundational premise of hedonistic Utilitarianism, that happiness/pleasure is our sole ultimate desire. If that premise is false, then Utilitarianism is false. In that case, the judgement Utilitarianism made about stealing is false.

This issue can’t be made or illustrated to have anything to do with the applied ethics topic, but it nonetheless helps us to evaluate the answer to the applied ethics question that Utilitarianism provided.

Utilitarianism on stealing

Evaluation of Utilitarianism on stealing

Kantian ethics on stealing

Evaluation of Kantian ethics on stealing

Virtue ethics on stealing

Evaluation of Virtue ethics on stealing

Meta-ethics on stealing

Evaluation of Meta-ethics on stealing

Simulated killing

(within computer games, plays, films etc)

Utilitarianism on simulated killing

Evaluation of Utilitarianism simulated killing

Kantian ethics on simulated killing

Evaluation of Kantian ethics on simulated killing

Virtue ethics on simulated killing

Evaluation of Virtue ethics on simulated killing

Meta-ethics on simulated killing

Evaluation of Meta-ethics on simulated killing

Eating animals

Utilitarianism on eating animals

Evaluation of Utilitarianism on eating animals

Kantian ethics on eating animals

Evaluation of Kantian ethics on eating animals

Virtue ethics on eating animals

Evaluation of Virtue ethics on eating animals

Meta-ethics on eating animals

Evaluation of Meta-ethics on eating animals

Deception & telling lies

Utilitarianism on deception & telling lies

Evaluation of Utilitarianism on deception & telling lies

Kantian ethics on deception & telling lies

Evaluation of Kantian ethics on deception & telling lies

Virtue ethics on deception & telling lies

Evaluation of Virtue ethics on deception & telling lies

Meta-ethics on deception & telling lies

Evaluation of Meta-ethics on deception & telling lies

Ethics and Moral Subjectivism

This essay about the complexities of ethics and moral subjectivism. It explores the notion that moral judgments are subjective, varying between individuals, cultures, and societies. While moral subjectivism promotes cultural understanding and empathy, it also raises concerns about moral relativism and the absence of objective moral truths. Despite criticisms, it encourages critical reflection on personal moral beliefs and promotes open-mindedness. Ultimately, navigating moral subjectivism requires a balanced approach that acknowledges both cultural diversity and universal human values.

How it works

Ethics and moral subjectivism present a complex interplay in the realm of philosophy and human behavior. At the heart of this discourse lies the question of whether morality is objective or subjective, and the implications this distinction holds for our understanding of ethical principles and decision-making processes.

Moral subjectivism posits that ethical judgments are dependent on individual perspectives, beliefs, and cultural contexts. In other words, what is deemed morally right or wrong can vary from person to person, society to society, and culture to culture.

This viewpoint challenges the notion of universal moral truths and suggests that ethical standards are not fixed but rather contingent upon subjective experiences and interpretations.

One of the key arguments in favor of moral subjectivism is its recognition of diversity in moral beliefs and practices across different cultures and societies. Proponents of this view argue that acknowledging the subjectivity of morality allows for greater respect and understanding of cultural differences, promoting tolerance and acceptance in multicultural societies.

However, moral subjectivism also faces criticism, particularly regarding its potential to undermine moral objectivity and justify morally reprehensible actions. Critics argue that without a foundation of objective moral truths, individuals and societies may be susceptible to moral relativism, where any action can be deemed morally acceptable as long as it is justified within a particular cultural or personal framework.

Despite these criticisms, moral subjectivism offers valuable insights into the complexities of ethical decision-making. It encourages individuals to critically examine their own moral beliefs and to consider alternative perspectives, fostering intellectual humility and open-mindedness. Moreover, by recognizing the subjective nature of morality, moral subjectivism emphasizes the importance of empathy and compassion in ethical deliberations, highlighting the significance of understanding and respecting the experiences and perspectives of others.

In conclusion, the discourse surrounding ethics and moral subjectivism is both intricate and thought-provoking, raising fundamental questions about the nature of morality and its implications for human behavior and society. While moral subjectivism challenges traditional notions of objective morality, it also offers opportunities for greater cultural understanding and ethical reflection. Ultimately, navigating the complexities of moral subjectivism requires a nuanced approach that acknowledges both the diversity of moral perspectives and the universal human values that underpin ethical decision-making.

Cite this page

Ethics And Moral Subjectivism. (2024, Apr 22). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/ethics-and-moral-subjectivism/

"Ethics And Moral Subjectivism." PapersOwl.com , 22 Apr 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/ethics-and-moral-subjectivism/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Ethics And Moral Subjectivism . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/ethics-and-moral-subjectivism/ [Accessed: 28 Apr. 2024]

"Ethics And Moral Subjectivism." PapersOwl.com, Apr 22, 2024. Accessed April 28, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/ethics-and-moral-subjectivism/

"Ethics And Moral Subjectivism," PapersOwl.com , 22-Apr-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/ethics-and-moral-subjectivism/. [Accessed: 28-Apr-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Ethics And Moral Subjectivism . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/ethics-and-moral-subjectivism/ [Accessed: 28-Apr-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

Philosophy and moral decision making

Posted on April 22, 2024 by Guest Contributor

This post was written by guest contributor, Jillian Meyer.

Should you cheat on your exam to get a good final grade in your class? When is it okay to lie? If your child is going for an internship at your company, is it morally permissible to give them a leg up over other applicants? We make moral decisions every day, forming a moral personality from the choices we make about right and wrong. Our moral foundations come from many different sources, such as our religions, the legal system, and even our personal past experiences. The brain plays a big role in moral decision making, and damage to certain areas can completely change our morality . To articulate the impact the brain can have on morality, moral psychologists often turn to the philosophical roots of moral perspectives. Ancient philosophy continues to define our moral decisions today, so knowledge of different philosophical theories is imperative and detailed below.

Ethical Theories

According to Aristotle, people should become virtuous by doing virtuous things. One of the most well-known, modern, western ethical theories started with Aristotle himself: virtue ethics. Just as the name suggests, this theory focuses on the virtues one must acquire to live a good life. Aristotle focused not on the moral action of a situation, but rather on the moral character of a person . He emphasized cultivating virtues such as honesty, courage, justice, generosity, and more. Virtue ethics places virtues and vices at the center of the theory, asking what the most virtuous person would do in a given situation.

Another popular modern ethical theory is consequentialism , which focuses on all of the potential consequences of a moral act. In consequentialism, it does not matter what the most virtuous person would do in a situation, but rather it identifies all of the possible consequences and suggests that the action with the most positive outcome should be taken. A popular form of consequentialism, utilitarianism , gives specification to “the most positive outcome” by suggesting that it can be defined as the outcome that produces the greatest overall amount of net happiness. Philosophers such as Jeremy Bentham , John Stuart Mill , and Henry Sidgwick were all early proponents of utilitarianism. Mill explains this theory, stating that “[a]ctions are right in proportion as they tend to promote happiness, wrong as they tend to produce the reverse of happiness” (Mill, 1863, p. 77) . Consequentialism is a moral framework that examines all of the possible consequences of an action and weighs the positivity of the outcomes, and utilitarianism decides the most positive outcome based on what action will produce the greatest net happiness.

The final prevalent modern ethical theory, deontology , often stands in opposition to consequentialism. Instead of focusing on all of the consequences of an action, deontology instead focuses on the moral action itself and suggests that not all actions can be justified by the consequences. While there are many parts of deontological theory, the main considerations include fundamental principles and rights. For example, deontology suggests that certain actions like lying or stealing are fundamentally immoral and never justified. Also, humans have certain fundamental rights that should never be violated, such as the right to not be murdered. Immanuel Kant is the philosopher most commonly associated with deontological theory, emphasizing that we must always treat people as ends and never means to an end.

It is important to note that Greek philosophy, which became the basis for modern western philosophy, does not hold the only set of ethical theories and frameworks out there. In fact, western, educated, industrialized, religious, and democratic ( WEIRD ) states are the outliers of the world. However, in the western world, virtue ethics, utilitarianism, and deontology are the most widely talked about (and researched) philosophical theories.

Ethical Decision Making

Moral psychology research has found that altering the way we process information can alter the moral decisions we ultimately make. Duke and Bègue’s “ drunk utilitarian ” piece found that blood alcohol content correlates with utilitarian moral decisions, suggesting that we make more utilitarian decisions when our social cognition is impaired. Researchers have also discovered that people make more utilitarian decisions (maximizing happiness) when they are presented with a dilemma written in their second language . Additional research has found that this is due to the distancing and blunting of emotional reactions to dilemmas, allowing participants to see them in a more unemotional way. Our emotions can impact our moral decisions, and it seems that situations without an emotional factor lead us to more calculated utilitarian decisions. Further studies have shown that even just foreign accents lead people to make more utilitarian decisions. When given the trolley (an impersonal moral dilemma) and footbridge (a more personal moral dilemma) problems, participants made more utilitarian decisions listening to a speaker in the same language but with a foreign accent compared to a speaker in the same language with the same accent. These researchers provide three possible explanations for this phenomenon: emotion reduction, increased cognitive load, and psychological distance, which could all play a part in this finding.

Morality and the Brain

Cognitive research has furthered this distinction between emotion-based and logic-based moral decisions. Greene and colleagues found that different brain regions are activated for intuitive, emotional moral thought (the ventromedial prefrontal cortex) and reasoned, logical moral thought (the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex). Process dissociation models in social psychology have found a way to separate these two cognitive processes within a single task, such as a morality attribution task . One multinomial processing tree created by Gawronski and colleagues provides a way to analyze this distinction in moral decision making, separating intentional, utilitarian decisions from unintentional, deontological decisions. By understanding how these philosophical theories function differently cognitively, moral psychologists can better understand how different kinds of moral decisions are made.

Our moral decisions are based on a plethora of factors and can be altered with very minor changes to how our brains process moral dilemmas. The philosophical theories of virtue ethics, utilitarianism, and deontology have provided a foundation for understanding different moral perspectives, and a helpful starting point for scientific research on moral decisions. Moral psychology is continuing to combine the humanities research in philosophy with the science research in psychological and brain sciences to learn more about how we make the moral decisions that shape our lives.

Acknowledgements:

A big thank you to Dr. Joseph Porter, the philosophy pro and a great friend, for aiding my interpretation of these early philosophical concepts!

Edited by Chloe Holden and Emma Cleary

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

College of Arts + Sciences

Are you a graduate student at IUB? Would you like to write for ScIU? Email [email protected]

Subscribe By Email

Get every new post delivered right to your inbox.

Your Email Leave this field blank

This form is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Reid’s Ethics

We are often told that the moral theories defended by modern philosophers fall into two types. On the one hand are rationalist positions developed by thinkers such as Samuel Clarke, William Wollaston, and Richard Price. The rationalists, it is said, believe that reason is the basis of morality, as morality is (in some sense) both grounded in and grasped by reason. On the other hand are sentimentalist positions championed by philosophers such as the Third Earl of Shaftesbury, Francis Hutcheson, and David Hume. The sentimentalists, it is claimed, hold that affect is the basis of morality. According to the standard classification, the sentimentalists believe that morality has relatively little to do with reason, as it is (in some sense) both grounded in and discerned by sentiment.

Thomas Reid’s (1710–1796) moral philosophy does not neatly fit into this scheme of classification. To be sure, some characterize Reid as a rationalist working within the tradition of Clarke and Price (see MacIntyre 1966 and Rawls 2000, Introduction). One can see why. Reid, after all, affirms core rationalist claims, such as that there is a body of necessary moral principles that are self-evident to the ordinary person. But there are important elements of Reid’s thought that do not fit the rationalist paradigm. For example, Reid defends the view that all normal, mature human beings are endowed with a moral sense. Like philosophers such as Hutcheson and Hume, Reid claims that the moral sense yields sentiments of various sorts that themselves occasion “our first moral conceptions,” such as the apprehension that an act is approbation-worthy (EAP V.ii: 279). This account of concept formation, according to some philosophers, would make Reid’s position a version of sentimentalism (see D’Arms 2005). In this respect, Reid’s position resembles not Clarke’s and Price’s but Hutcheson’s and Hume’s.

There is, then, a sense in which Reid’s moral philosophy resists ready categorization. It is neither a version of rationalism nor sentimentalism, but an attempt to blend those features from both these traditions that Reid found most attractive. This presents a challenge to the contemporary interpreter of Reid’s moral philosophy. One wonders: Is Reid’s theory of morals an exotic hybrid, one which eludes the categories used by contemporary philosophers to describe ethical theories?

Not exactly. Anyone familiar with contemporary moral philosophy could not fail to miss the resemblance that Reid’s position bears to the view defended some one hundred and fifty years later by W. D. Ross (see Ross 2002). Although Ross never mentions Reid as an influence, both thinkers operate within a broadly non-naturalist framework according to which the sciences offer us limited insight into the nature of moral reality. In so doing, they both stood against powerful trends in their day to “naturalize” ethics. Moreover, both reject monistic accounts of the moral domain, such as those defended by Kantians and consequentialists, according to which there is one master ethical principle from which all others are derived. According to both Reid and Ross, there is instead a plurality of self-evident moral first principles, none of which is reducible to another.

In light of this, we might describe Reid’s position as a proto-Rossian version of ethical intuitionism. While such a description is tempting, it would probably be misleading. For the parallels between Reid and Ross extend only so far. The most important difference between the two thinkers is this: Ross frames his project in the light of G. E. Moore’s Open Question Argument and Mill’s utilitarianism—two philosophical topics about which Reid knew nothing. Reid, by contrast, developed his version of ethical intuitionism within the context of a defense of a certain account of human agency, according to which each of us is endowed with “active power” which we can freely exercise. Reid believed that this account of human agency, when coupled with our best scientific knowledge, yields a form of non-naturalist ethical intuitionism. Call a position that grounds many of its core metaethical claims about the nature of moral reality in a particular view of human agency an agency-centered account . Agency-centered views tell us that in order to understand the nature of moral reality we must first examine the nature of agency. Reid’s is an agency-centered version of ethical intuitionism. Ross’s, by contrast, is not.

The project of this essay is to present both the motivations for and fundamental contours of Reid’s agency-centered intuitionist view. Before diving into the details of Reid’s position, however, it may be worth saying a word about the influence of Reid’s views in contemporary ethics. If one were to gauge this influence by the number of books or articles written in the last one hundred years about Reid’s ethics, one would have to conclude that his influence is negligible. Very little has been written about Reid’s moral philosophy. Indeed, Reid is not even included in what is perhaps the standard anthology on the British Moralists, the two-volume work edited by Selby-Bigge of the same title (Selby-Bigge 1965). Moreover, one would also have to conclude that Reid’s influence on moral philosophers who receive a great deal of attention, such as Moore, is marginal. For example, in the flurry of work produced in 2003 on the centenary of the publication of Moore’s Principia Ethica , no one mentions Reid as an influence on Moore’s ethical views.

The reality of the matter, however, is that Reid has indeed exercised considerable influence on contemporary moral philosophy, albeit indirectly. This influence runs primarily through Henry Sidgwick, who knew Reid’s work well (see Sidgwick 2000, Ch. 16). Sidgwick, it seems, exposed his student, G. E. Moore, to Reid’s views (see Beanblossom 1983). Reid’s broadly common sense methodology and his positive views were subsequently taken up by Moore. Among the more salient similarities one finds in their ethical views is that both thinkers are interested in whether the fundamental moral properties are definable. Reid claims they are not; fundamental moral properties are, in Reid’s estimation, simple, indefinable, and sui generis (EAP III.iii.v). Famously, Moore said the same, although for somewhat different reasons. And the rest, as they say, is history. Depending on one’s views, one might view this history as one in which Moore finally put ethical theory on the right track or, alternatively, pushed it off the rails. Whatever one’s opinion on this issue, Reid seems to have had a role in its direction.

1.1 Reid’s alternative

1.2 reid’s moral non-naturalism, 2.1 reid’s defense of the hierarchy thesis, 3.1 reid’s defense of the objectivity of moral first principles, 4.1 reid’s view compared with hutcheson’s, 4.2 reid’s defense of the reliability of the moral sense, 5. conclusion, primary literature, secondary literature, other internet resources, related entries, 1. the system of necessity.

Reid’s moral philosophy, according to the gloss offered thus far, is an agency-centered intuitionist position, which also blends together both rationalist and sentimentalist influences. Given its synthetic character, it is natural to ask how best to enter into Reid’s thought. A promising avenue is to note a pattern of thought present in Reid’s work. In his work in epistemology and philosophy of mind, which is found primarily in An Inquiry into the Human Mind (IHM) and Essays on the Intellectual Powers of Man (EIP), Reid frames his project as a response to a general position that he calls the Way of Ideas. This position, which Reid says unites philosophers as diverse as Aristotle, Locke, Berkeley, and Hume, holds that we are never acquainted with the external world but only with “images” or sense data in the mind. What Reid says positively about our perception of the external world is couched as a response to this view. Although it is rarely noted, Reid’s work in ethics in Essays on the Active Powers of Man (EAP) is also framed as a response to a general position, which he claims is adopted by philosophers as diverse as Spinoza, Leibniz, and Hume. This position Reid ordinarily calls the System of Necessity. Reid’s own positive views about the nature of agency and the moral domain are best viewed as a response to the System of Necessity. Let us, then, enter Reid’s moral philosophy by having before us the rudiments of the System of Necessity.

Suppose you have fallen asleep in your bed after a long day of work. You briefly wake during the night, noting that someone has left a kitchen light on. You do not want, however, to get out of bed at this hour. Still, after pondering the issue for a moment, you know that you should do so. So, you drag yourself out of bed and turn the light off. How should we describe your behavior?

According to advocates of the System of Necessity, there is a sense in which the performance of this action is up to you. No one forced you to get up out of bed. There is also a sense in which you did it because you believed you should. It is this belief, coupled with a desire—perhaps to do what is right—that moved you to get out of bed. Finally, there is a sense in which there is an explanation of your action that is perfectly law-like. Because your desire (let us suppose) to do what is right was stronger than your desire to stay in bed, it won out. Under the supposition that stronger motivations win, we have a perfectly general, law-like explanation of why you acted as you did.

In Reid’s view, then, proponents of the System of Necessity affirm these three claims:

- Every human action has a sufficient cause.

- Provided normal background conditions obtain, the sufficient cause of a human action is its motive, which is a mental state of an agent.

- Every human action is subsumable under a law, which specifies that for any agent S , set of motives M , and action A at t , necessarily, if S performs A , then there is some member of M that is S ’s strongest motive, which causes S to perform A at t .

Viewed from on angle, these claims appear not to fit tightly together. One could accept any one and reject the others. Viewed from another angle, however, they express a unified picture of human action, one according to which human action is a natural phenomenon that is subsumable under laws in much the same way that other ordinary natural events are. If one is attracted to this broadly naturalistic position, as Reid claims that figures such as Spinoza, Hume, Priestley, and Kames were, then these claims form a natural package (see Cuneo 2011a).

Reid, however, believed that this package of claims provides a deeply distorted picture of human action. Why did he believe this? In large part because he could not see how it could account for genuinely autonomous human agency in at least two senses of this multivalent term. In the first place, autonomous actions are ones that can be properly ascribed to an agent. But if the System of Necessity were true, Reid claimed, there is no proper sense in which actions that appear to be performed by an agent could justly be attributed to that agent—the human agent being simply a theater in which various drives and impulses vie for dominance. One could, if the System of Necessity were right, attribute actions to mental states such as desires. And this might be adequate to describe the behavior of animals and addicts. But, Reid claims, it is not adequate to describe purposeful human action. For human action, in Reid’s view, must be attributable to the person as a whole, not some force working in or on her (see Korsgaard 2009, xii).

Secondly, autonomous agency is such that an agent can exercise a certain type of control over the various impulses that present themselves when deliberating. Suppose, to return to our earlier case, that you briefly wake during the night, noting that someone has left a kitchen light on. You want not to get out of bed at this hour. Must you capitulate to your strongest desire? Not if you are autonomous. For genuinely autonomous agents, according to Reid, are reflective. Any desire is such that an autonomous agent can direct his attention not only to its object, but also to the desire itself, asking: Should I act on it? That is, any such agent can ask these two questions: First, would acting on this desire contribute to my genuine well-being? And, second, is there a sufficient moral reason or obligation for acting on or ignoring it? These two questions advert to what Reid calls the rational principles of action (see EAP, III.iii.i). The first principle Reid calls the principle with “regard to our good on the whole,” the second the “principle of duty.” The fact that you needn’t capitulate to your desire to stay in bed but can step back and critically assess it with reference to these two rational principles of action, in Reid’s estimation, is what separates normal, mature human beings from the rest of the natural order.

This point was important enough to Reid that he highlights it in the Introduction to Essays on the Active Powers and elsewhere:

The brutes are stimulated to various actions by their instincts, by their appetites, by their passions: but they seem to be necessarily determined by the strongest impulse, without any capacity of self-government…. They may be trained up by discipline, but cannot be governed by law. There is no evidence that they have the conception of a law, or of its obligation. Man is capable of acting from motives of a higher nature. He perceives a dignity and worth in one course of conduct, a demerit and turpitude in another, which brutes have not the capacity to discern…. [Men] judge what ends are most worthy to be pursued, how far every appetite and passion may be indulged, and when it ought to be resisted…. In them [the brutes] we may observe one passion combating another, and the strongest prevailing; but we perceive no calm principle in their constitution that is superior to every passion, and able to give law to it. (EAP, 5 and II.ii: 57)

When Reid talks about our capacity to be governed by law he has in mind our capacity to regulate our behavior by assessing it in terms of the two rational principles of action. Reid, then, champions what we might call a regulation account of autonomy . We are autonomous, rational agents, in Reid’s estimation, in virtue of the fact that we can regulate or govern our behavior by stepping back from our various impulses, desires, instincts, and assess prospective actions in light of the two rational principles of action. It is this dimension of human action, according to Reid, that is missing altogether from the description of agency offered by advocates of the System of Necessity.

In Reid’s view, then, the System of Necessity fails to offer an accurate account of human agency. What alternative account of agency did Reid propose? One that accepts the following three claims:

(1′) Every human action has a cause, which in the case of free human action is not itself a motive, but the agent himself. (2′) Motives are not mental states but the ends for which an agent acts. (3′) Human action is nomic only to this extent: If an agent fails to exercise autonomy when deliberating (and he is not in a state of indifference), then his strongest desire to act in a certain way will prevail. If he exercises autonomy when deliberating, however, then he will act on the motive that seems to him most rationally appropriate.

Let us consider these three claims in turn.

The first statement, (1′), expresses Reid’s commitment to an agent causal account of human free action. Reid presents various arguments for this view in Essays on the Active Powers of Man , but it is worth emphasizing that a central consideration that Reid furnishes in its favor appeals not to common sense but to what science appears to tell us. Reid, like most of his contemporaries, was a Newtonian. In Reid’s judgment, however, Newtonian science is committed to the claim “that matter is a substance altogether inert, and merely passive; that gravitation, and the other attractive or repulsive powers … are not inherent in its nature, but impressed upon it by some external cause” (EAP I.vi: 34). Matter, according to this view, does not cause anything. On the assumptions that there is genuine causality in the world and that agents are causes, it follows that agents, who are not material things, in Reid’s view, are the only causes. Reid takes Newtonian science to imply a mitigated version of occasionalism according to which the only genuine causation in the world is agent causation.

The second statement above, (2′), expresses Reid’s commitment to a broadly teleological account of human agency, according to which autonomous human action is explained not by the impulses that present themselves to an agent when deliberating but by the ends for which she acts. In his defense of this view, Reid argues that, contrary to the adherents of the System of Necessity, motives are not mental states that cause us to act, for motives are not the right sort of thing to be causes: They are not agents. In some places, in fact, Reid says that motives (as he thinks of them) have no “real existence,” by which he seems to mean (at least) that they are not part of the spatio-temporal manifold but are abstracta (see EAP IV.iv: 214).

These claims might take us aback: Motives are not causes and have no real existence? How could that be? When evaluating these claims, two things should be noted. First, Reid is working with a rather narrow understanding of what it is for something to be a cause (and to exist)—an understanding, we’ve seen, he thinks fits best with a Newtonian understanding of the world. Second, Reid’s considered view about the role of motives is actually more complicated than (2′) would have us believe. (2′) expresses the view that Reid defends in Essay IV of Essays on the Active Powers , “Of the Liberty of Moral Agents.” But anyone who has read Essay III, “Of the Principles of Action,” knows that Reid claims that motives or “principles of action” divide into three kinds: mechanical, animal, and rational. Mechanical principles of action are what we would call instincts, such as the unreflective impulse to protect oneself from perceived harm. Animal principles of action are a more varied lot. Under this category, Reid places the so-called benevolent affections, such as the affection felt between kin, gratitude to benefactors, pity and compassion, friendship, public spirit, and the like (see EAP III.iii.iv). He also includes the so-called malevolent affections, such as resentment and the desire to dominate others. (In section III, we will see a reason to believe that some animal principles, by Reid’s own lights, are not ones that could be had by the animals.)

All this complicates Reid’s picture. Reid seems to want to allow that motives come in two varieties. On the one hand, Reid says that rational motives function as “advice” or “exhortation” which do not push but pull us to action. On the other, he describes the mechanical and animal motives as “impulses,” which do not pull but push us to action (EAP II.ii and IV.iv). How best to understand what Reid is saying? Perhaps the best conclusion to draw is that Reid does not have a unified account of motives. Some of the rational motives are best described as being either those ends for which we act or principles by which we evaluate those ends for which we act. Other motives—the mechanical and a range of the animal ones—are not; they are what push or impel us to action (see Cuneo and Harp 2016).

Are these latter motives best described as having a causal influence on behavior? Perhaps they are, according to a more relaxed understanding of causality than that with which Reid officially works. For suppose we agree that there are processes that are instigated by the exercise of active power, such as the process that is instigated by an agent’s willing to raise her arm. In Reid’s view, this process includes the exercise of active power, which is the agent’s willing to raise her arm, the activity of nerves and muscles and, finally, the raising of her arm. If we allow ourselves to talk of elements of this process as causes in a “lax and popular sense,” then perhaps some motives, in Reid’s view, could be called causes. Of course Reid would have to say that in some cases the motives that “cause” us to act are not part of a causal process that we ourselves instigate. Not every desire or mental state we have is the causal consequence of the exercise of our active power in a given way. (That I desire to eat an ice cream cone, for example, appears to be a causal consequence not of the exercise of my active power but of your handing me an ice cream cone.) Reid would have to say, then, that those mental states and events that are not simply the causal consequence of the exercise of active power are parts of processes instigated by some other agent cause, such as God. This may seem odd. But it seems to be the broader picture within which Reid operated. All causal processes in nature (which are not due to us) are instigated by the exercise of God’s active power. A typical case of human action involves the coincidence of the exercise of our active power with God’s (see EAP I.vi and Cuneo 2011a).

Let us now turn to the third statement above, namely, (3′). This claim expresses Reid’s two-fold conviction that free human action is (i) not in any interesting sense nomic, and (ii) that we can assess our motives along two dimensions. We can assess them, first, according to their psychological strength and, second, according to their rational authority.

That free human action is not nomic is simply an implication of Reid’s conviction that we are endowed with libertarian free will, the exercise of which does not fall under any natural law in the sense described by Newtonian science. That our motives can be assessed along two dimensions, by contrast, is an implication of Reid’s regulation account of autonomy.

To see how Reid is thinking about the strength of motives, consider a case in which you are moved to action by some animal principle of action. Imagine, for example, you are incited to reprimand someone in your family because you believe that he or she has acted irresponsibly by leaving a kitchen light on during the night. One way to assess this action would be to ask whether it conforms to the rational principles of action. Let us suppose that, in the case we are considering, by reprimanding you risk alienating yourself from those with whom you live; the circumstances you’re in call for a calm and measured response. While there may be good reasons to alienate yourself from others, expressing your anger in these circumstances is not one of them. This motive in these circumstances, then, has no rational authority.

Now consider the same motive not with respect to its rational authority but with regard to its psychological strength. Is this motive the strongest of your motives? Reid maintains that this is a difficult question to answer. One of the complaints Reid raises about the System of Necessity is that it sheds no light on the matter. Although advocates of the System of Necessity claim that human actions can be subsumed under natural laws, the laws to which they appeal in order to assess the strength of motives are either false or trivial. For recall that, according to the System of Necessity:

(3) Every human action is subsumable under a law, which specifies that for any agent S , set of motives M , and action A at t , necessarily, if S performs A , then there is some member of M that is S ’s strongest motive, which causes S to perform A at t .

Reid finds this claim totally unpersuasive. It is worth quoting at length what he has to say about it:

It is a question of fact, whether the influence of motives be fixed by laws of nature, so that they shall always have the same effect in the same circumstance. Upon this, indeed, the question about liberty and necessity hangs. But I have never seen any proof that there are such laws of nature, far less any proof that the strongest motive always prevails. However much our late fatalists have boasted of this principle as of a law of nature, without telling us what they mean by the strongest motive, I am persuaded that, whenever they shall be pleased to give us any measure of the strength of motives distinct from their prevalence, it will appear, from experience, that the strongest motive does not always prevail. If no other test or measure of the strength of motives can be found but their prevailing, then this boasted principle will be only an identical proposition, and signify only that the strongest motive is the strongest motive … which proves nothing. (C, 176–77)

According to Reid, (3), then, is either false or trivial (for discussion, see Yaffe 2004, Ch. 6).

We should now have a better picture of Reid’s favored account of human agency. It is one according to which agents are causes, at least some motives are not causes but ends, and autonomous action is non-nomic. Earlier I said that this picture of agency grounds his non-naturalist account of the ethical domain. Let me now explain how.

Like most of his contemporaries, Reid’s worldview was Newtonian. While he was convinced that the natural sciences should conform to Newtonian methods, Reid held that these methods have their limitations. In a passage from an unpublished review composed toward the end of his life, Reid writes:

There are many important branches of human knowledge, to which Sir Isaac Newton’s rules of Philosophizing have no relation, and to which they can with no propriety be applied. Such are Morals, Jurisprudence, Natural Theology, and the abstract Sciences of Mathematicks and Metaphysicks; because in none of those Sciences do we investigate the physical laws of Nature. There is therefore no reason to regret that these branches of knowledge have been pursued without regard to them. (AC, 186)

In this passage, Reid tells us that Newton’s rules pertain only to the physical laws of nature and what is subsumable under them. But the rational principles of action, we have seen, are not themselves the physical laws of nature. They do not concern how the universe in fact operates. Rather, they concern how rational agents ought to conduct their behavior. Nor are these principles subsumable under Newton’s laws (EAP IV.ix: 251). They are, in Reid’s view, not part of the space/time manifold. It follows that Newton’s methods should not guide our theorizing about the rational principles of action. Since moral principles are among the rational principles of action, it follows that they are not identical with or subsumable under Newton’s laws. Given the additional assumption that natural science must conform to Newton’s rules, Reid concludes that morality is not the subject matter of natural science. That this is so, Reid continues, is “no reason to regret.” It is a matter of simply acknowledging the implications of Newton’s system—implications, Reid maintains, that philosophers such as Hume and Priestley, who also took themselves to be followers of Newton, had failed to appreciate.

In sum: Suppose we understand moral naturalism to be the view that moral facts are natural. And suppose we say, in a rough and ready way, that a fact is natural just in case it pulls its explanatory weight in the natural sciences (see Wiggins 1993). Reid maintains that Newtonian methods exhaust the limits of natural science. Newtonian science, however, does not investigate the ends or rational principles for which we act. The ends for which we act neither fall under Newtonian laws nor are identical with them. But moral facts, Reid says, are among the ends or rational principles for which we act. It follows that, in Reid’s view, moral facts are not the proper object of scientific inquiry. The moral domain is autonomous.

2. The Rational Principles of Action

Philosophers such as Hume and Priestly were eager to apply Newton’s methods to the moral domain. Reid, however, viewed attempts to use Newtonian methods to understand the moral domain as mistaken—not, once again, because he viewed Newtonian science as suspect, but because he held that Newton’s methods themselves require this. That said, we have seen that there is a sense in which Reid believes that human action is law-governed. We can regulate our behavior by reference to the rational principles of action. Earlier we saw that these principles are of two kinds: They concern our good on the whole and duty. Reid holds that these principles stand in a certain kind of relation to one another. We can better identify this relation by having the notion of motivational primacy before us.

Suppose we say that a state of affairs P has motivational primacy for an (ordinary adult) agent S just in case three conditions are met. First, in a wide range of ordinary cases, P is a type of consideration in light of which S would act. Accordingly, were S to deliberate about what to do, P is a type of state of affairs that S would, in a wide range of cases, not only use to “frame” his practical deliberations, but also endeavor to bring about. That my loved ones flourish is such a state of affairs for many of us.

Second, P is a sufficient reason for S to act. Roughly put, P is a sufficient reason for S to act just in case were S to deliberate about what to do, then (in a wide range of ordinary cases) S would take P to be a reason to act and would endeavor to bring about P even if he believed (or presupposed) that his doing so would not bring about (or increase the likelihood of his bringing about) any further state of affairs that he values. Imagine, for example, S is like many of us inasmuch as he takes himself to have a reason to bring about the flourishing of his loved ones. This is a sufficient reason for S to act since he would endeavor to bring about the flourishing of his loved ones even if he believed that his doing so would not bring about any further state of affairs that he values, such as his gaining increased notoriety among his peers .

Third, P has deliberative weight for S . For our purposes, we can think of this as the claim that P is a reason of such a type that, in a wide range of circumstances, were S to deliberate about what to do, then S would take P to trump other types of reasons, even other sufficient reasons. Many of us, for example, hold that there is a beautiful sunset on the horizon is a sufficient reason to stop whatever we are doing and enjoy it. Still, for most of us, that an act would bring about or preserve the flourishing of our loved ones has greater deliberative weight than this. If a person had to choose between enjoying a beautiful sunset, on the one hand, or protecting her child from danger, on the other, then the latter reason trumps.

Having introduced the notion of motivational primacy, we can now identify a claim that is arguably the centerpiece of Reid’s discussion of rational motivation, namely:

The Hierarchy Thesis: In any case in which an agent must decide what to do, considerations of what is morally required should have motivational primacy. Specifically, what is morally required of an agent should have motivational primacy over what he takes to be his good on the whole.