Essay on Terai Region Of Nepal

Students are often asked to write an essay on Terai Region Of Nepal in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Terai Region Of Nepal

Introduction to terai region.

The Terai Region of Nepal is a lowland area in the southern part of the country. It is known for its rich soil which is very good for farming. This area has a lot of forests, wildlife, and rivers too.

Climate and Weather

The Terai Region experiences a warm climate most of the year. Summers are very hot, and winters are mild. This weather is perfect for growing many kinds of crops.

People and Culture

Many different communities live in the Terai. They have their own unique traditions, languages, and festivals. People here mostly depend on farming for their living.

Wildlife and Forests

The Terai is home to dense forests that are full of diverse wildlife, including rare animals like tigers and rhinos. These forests are important for the environment and tourism.

250 Words Essay on Terai Region Of Nepal

Terai region: nepal’s diverse treasure.

Nepal’s Terai region is a vibrant and diverse treasure stretching along the southern border of the country. It is a fertile, flat belt of land that starts from the Siwalik Hills in the north and extends to the Indian border in the south. The region is home to a wide range of ethnic groups, cultures, and religions, making it a fascinating place to explore.

Rich History and Cultural Heritage

The Terai region has a rich historical and cultural heritage that dates back centuries. It was once a part of the ancient Magadha Kingdom and later became a vital trade route between Nepal and India. The region has also been influenced by the Mughal Empire and the British Raj, which left behind a unique blend of cultures and traditions.

Natural Beauty and Wildlife

The Terai region is renowned for its natural beauty and wildlife. It is home to lush forests, wetlands, and grasslands that support a diverse range of flora and fauna. The region is famous for its national parks, including Chitwan National Park, which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and home to endangered species such as the one-horned rhinoceros and the Bengal tiger.

Agriculture and Economic Importance

The Terai region is vital to Nepal’s economy. The fertile soil and favorable climate make it ideal for agriculture. The region produces a variety of crops, including rice, wheat, sugarcane, and jute. It is also home to numerous industries, including textiles, food processing, and tourism. The region’s strategic location makes it a crucial gateway for trade with India and other neighboring countries.

Challenges and Opportunities

The Terai region faces several challenges, including poverty, unemployment, and environmental degradation. However, it also has vast potential for development. The government is actively working to improve infrastructure, promote education, and attract investment to the region. The Terai region has the potential to become a major economic hub and a vital center for tourism and cultural exchange.

500 Words Essay on Terai Region Of Nepal

The terai region of nepal: a diverse and fertile land, geography of the terai.

The Terai is a flat and fertile region, with an average elevation of just 150 meters above sea level. It is bounded by the Himalayas to the north and the Indian state of Bihar to the south. The Terai is also crossed by several major rivers, including the Ganges, the Koshi, and the Narayani.

Climate of the Terai

The Terai has a tropical climate, with hot and humid summers and mild winters. The average temperature in the Terai is 25 degrees Celsius. The region receives an average of 1500 millimeters of rainfall per year, which is distributed throughout the year.

People and Culture of the Terai

Agriculture in the terai.

The Terai is a major agricultural hub of Nepal, and it produces a variety of crops, including rice, wheat, maize, and sugarcane. The region is also home to a large number of livestock, including cattle, buffalo, and goats.

Biodiversity of the Terai

The Terai is also home to a rich biodiversity, including a variety of plants and animals. The region is home to several national parks and wildlife sanctuaries, including the Chitwan National Park and the Bardia National Park. These parks are home to a variety of animals, including tigers, rhinos, elephants, and leopards.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Accomodation

- Culture & Tradition

- Responsible Tourism

- Community Homestay

- rato matsyendranath

- boudhanath stupa

- E-magazines

The best of Inside Himalayas delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for the latest stories.

Please leave this field empty.

Get the latest edition of Inside Himalayas on your doorstep.

Select Country Afghanistan Albania Algeria Andorra Angola Antigua and Barbuda Argentina Armenia Australia Austria Azerbaijan Bahamas Bahrain Bangladesh Barbados Belarus Belgium Belize Benin Bhutan Bolivia Bosnia and Herzegovina Botswana Brazil Brunei Bulgaria Burkina Faso Burundi Cabo Verde Cambodia Cameroon Canada Central African Republic (CAR) Chad Chile China Colombia Comoros Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Costa Rica Cote d'Ivoire Croatia Cuba Cyprus Czechia Denmark Djibouti Dominica Dominican Republic Ecuador Egypt El Salvador Equatorial Guinea Eritrea Estonia Eswatini (formerly Swaziland) Ethiopia Fiji Finland France Gabon Gambia Georgia Germany Ghana Greece Grenada Guatemala Guinea Guinea-Bissau Guyana Haiti Honduras Hungary Iceland India Indonesia Iran Iraq Ireland Israel Italy Jamaica Japan Jordan Kazakhstan Kenya Kiribati Kosovo Kuwait Kyrgyzstan Laos Latvia Lebanon Lesotho Liberia Libya Liechtenstein Lithuania Luxembourg Madagascar Malawi Malaysia Maldives Mali Malta Marshall Islands Mauritania Mauritius Mexico Micronesia Moldova Monaco Mongolia Montenegro Morocco Mozambique Myanmar (formerly Burma) Namibia Nauru Nepal Netherlands New Zealand Nicaragua Niger Nigeria North Korea North Macedonia (formerly Macedonia) Norway Oman Pakistan Palau Palestine Panama Papua New Guinea Paraguay Peru Philippines Poland Portugal Qatar Romania Russia Rwanda Saint Kitts and Nevis Saint Lucia Saint Vincent and the Grenadines Samoa San Marino Sao Tome and Principe Saudi Arabia Senegal Serbia Seychelles Sierra Leone Singapore Slovakia Slovenia Solomon Islands Somalia South Africa South Korea South Sudan Spain Sri Lanka Sudan Suriname Sweden Switzerland Syria Taiwan Tajikistan Tanzania Thailand Timor-Leste Togo Tonga Trinidad and Tobago Tunisia Turkey Turkmenistan Tuvalu Uganda Ukraine United Arab Emirates (UAE) United Kingdom (UK) United States of America (USA) Uruguay Uzbekistan Vanuatu Vatican City (Holy See) Venezuela Vietnam Yemen Zambia Zimbabwe

- 26 January, 2024

Terai – The Other Face of Nepal

When people think of Nepal, the first things that come to mind are the Himalayas with its yaks and snow leopards, or the cultural and historical haven of the Kathmandu Valley . Most travelers find themselves seeking this emblematic image of Nepal, an image of hills and glaciers, narrow trekking paths and endless pastures. While the unparalleled magnificence of the Himalayas and their foothills are the face of Nepal for a good reason, travelers must not ignore that Nepal has another, equally unique, face. Underneath the shadow of the mountains are the vast lowlands, home to indigenous communities and wealthy in flora and fauna, the Terai is the other face of Nepal, less traveled but just as fascinating as the rest of Nepal.

Making up 17% of Nepal’s terrain, stretching seamlessly from far-west to far-east, and starting at the modest elevation of 70 meters above sea level, this belt of land boasts of a sub-tropical climate that fosters such fertility that it has become the agricultural backbone of Nepal. A land where all the Himalayan waters flow through to reach the Indo-Gangetic plain and then the ocean, the fertility of the Terai gives hold to more than just human agriculture.

The wildlife that emerges from the Terai is enough to leave one in awe for a lifetime. From old-growth, sub-tropical jungles to wide river beds and endless grasslands, the Terai is inhabited by fabled animals such as the Bengal Tiger, One-Horned Rhinoceros, crocodiles and tens of bird species. Not only this, but the people who inhabit the Terai still hold onto a way of life that can be rarely seen these days. Untouched by modernity, many indigenous communities live as they did a hundred years ago – hand in hand with the nature surrounding them.

To say that the Terai altogether falls out of the limelight of tourism woudn’t be fair, since its more famous national parks see hundreds of domestic and international tourists every year, but it can be said with some certainty that the Terai is largely untapped given the potential it holds. To understand this potential in a deeper way Inside Himalayas met with Abhishek Subedi, filmmaker from Morang, a Terai town in Eastern Nepal.

As a filmmaker, Mr Subedi has traveled extensively all across Nepal, but his recent works brought him back to the areas surrounding his hometown and beyond. His sensibilities towards ethnic communities, their lifestyles and culture have made him an anthropologist per se, and he hopes to pursue Rural Development academically. Fascinated by the nature, cultures, and people of the Terai, he believes that the Terai should be as much a highlight of the country as the rest of Nepal. He says that “humans are naturally drawn to other humans, no matter how different they may be from each other, and listening to their stories is an activity with no end. The Terai holds many untold stories, unexplored areas and unmet potential.”

Rooted in the belief that the Terai should learn how to show its unique identity to the rest of the world, Mr. Subedi explains why traveling to the Terai should be in your immediate priorities when visiting Nepal.

Cultural and Religious Significance

Mr. Subedi states that “the natural wonders of the Terai are marketed quite well, as a large number of tourist passes through some of the more famous national parks like Chitwan , but I believe that we are failing to market the rich cultural heritage of the Terai, perhaps because all of the attention is on Kathmandu when it comes to this.”

The diversity of the culture across this region is palpable, as it ranges from the birth place of important historical and religious figures such as Sita in Hinduism and Gautam Buddha in Buddhism , to various indigenous settlements, each with their distinct languages, forms of art, music and dance.

Buddhist Heritage

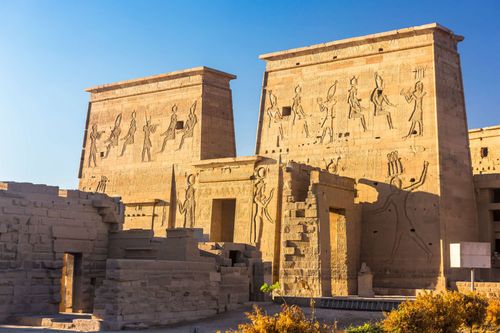

Lumbini , where the Buddha Siddharta Gautama, took his first breath, holds an unassuming charm, marked by a humble plaque and stone beneath the sheltering arms of a bodhi tree. Rediscovered in the 19th century, Lumbini stretches across three miles, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site adorned with monasteries built by various Buddhist nations.

As you wander through Lumbini on foot or opt for a leisurely bicycle tour, the various monasteries showcase a visual panorama of Buddhist architectural styles. From a Burmese-style golden pagoda to a Chinese-style temple reminiscent of Beijing’s Forbidden City, each structure narrates the adaptive journey of Buddhism through East Asia.

Beyond Lumbini, you can explore the remnants of Siddhartha’s palace in Kapilavastu, a place where the prince commenced his transformative journey. Nearby archaeological sites, marked by pillars erected by Ashoka and three stupas in Kundan, offer glimpses into the life and teachings of the Buddha.

For those drawn to this spiritual sanctuary, consider visiting during the cooler months from November to March . Lumbini, situated in the Terai, reveals its most inviting aspect during this time. Given the limited accommodations, prudent travelers secure reservations in advance. Accessible by a five-hour drive from Pokhara or a short flight from Kathmandu to Bhairahawa followed by a brief drive , Lumbini stands near the Indian border, offering a seamless continuation for those exploring the Buddhist pilgrimage sites in India.

Mithila Heritage

In the heart of the Terai region lies Janakpur , a city that evolves as a captivating tale of history and spirituality. Mithila paintings, crafted by the skilled hands of Maithili women, puts Janakpur on the global map of artistic expression. At its centre, the grand Janaki Temple, also known as Nau Lakha Mandir, becomes a significant pilgrimage site for Hindus, as it plays a pivotal role in the epic tale of Ramayana. Legend whispers that Goddess Sita, the Mithila princess of Janakpur, chose Prince Ram as her husband, and their sacred union was celebrated in the Vivaha Mandap. This is more than just a legend, though, as the Goddess was the daughter of the King of Janakpur, and they are both historical figures who have truly lived.

Beyond its temples, Janakpur stands as a cultural hub, nurturing a rich history of arts, language, and literature. As the heartland of the Mithila civilization, it becomes a melting pot of cultures and religions. The annual Vivah Panchami festival, held in November and December , transforms the temple surroundings into a spirited and spiritual haven.

Likewise, Ram Mandir, built by Amar Singh Thapa, pays homage to Prince Ram of Ayodhya, complementing Janakpur’s spiritual ambiance. Gangasagar, a holy pond near Ram Mandir, adds to the city’s spiritual allure, believed to be connected to the Ganga. During the Chhath festival, the pond transforms into a magical spectacle, inviting peaceful boat rides.

Swargdwar, on the west bank of Gangasagar, earns its name as the “gate to heaven” for the departed, adding a touch of the divine to Janakpur’s spiritual story. With that being said, the ideal time to explore Janakpur’s charm is during May, July, and August when the city dons pleasant weather and festivals.

Tharu Heritage

Primarily in the outskirts of Chitwan, Morang, and Sunsari the Tharu community is the largest ethnic group in the Terai region, deeply rooted in time as the probable original inhabitants of the Terai. With features reflecting their Mongoloid heritage and a warm, dark-brown complexion, the Tharu community holds within its diversity the proud lineage of Rana-Tharu, claiming an ancestry tied to the Rajputs in the western Terai.

To fully immerse yourself in the Tharu culture, plan your visit during the months when their festivals come to life, especially during the Maghe Sankranti , their New Year. It mostly falls in mid-January . However, if you travel to Chitwan, explore the Tharu culture as well, no matter what month it is.

Cuisine from the Terai

The people of the Terai region boast of a cuisine that is in stark difference from the rest of Nepal. With the use of unique ingredients and flavor, they expand the idea one has of Nepali cuisine .

Rajbanshi Cuisine

Bhakka is a winter delight originating from the culinary traditions of the Rajbanshi community in the Jhapa and Morang districts. Made from fresh rice flour, it is traditionally consumed after the harvest season but has become a breakfast staple all over the country.

Maithili Cuisine

A plate on Mithila showcases a medley of rice, wheat, fish, and sweet dishes. Infused with spices, herbs, and natural edibles, each recipe is a culinary masterpiece tailored to specific events. The mantra, “ Maachh, Paan aur Makhaan e teen ta aichh Mithila ke jaan ” (Fish, Betel, and water-lily seed are the soul of Mithila), resonates through the heart of Maithili gastronomy.

Likewise, in the heart of Maithili non-vegetarian delights, where fish, cooked in mustard oil with a blend of local spices, takes centre stage. From Rohu fish curry to mutton and a variety of fowl, Maithili cuisine elevates aquatic and terrestrial delights into cultural symbols. Vegetables claim their own space in the Maithili plate, with dishes like baigan adauri , arikanchan tarkari , and kadhi-bari offering a tantalizing array of flavours. The art of tempering, the use of spices like panch forna and hing , and the crafting of sun-dried and preserved vegetables showcase the intricacies of Mithila’s culinary expertise.

The culinary journey extends to a symphony of sweets and desserts like anarsa, thekua, pidikiya , and the revered dahi-cheeni , considered the king of desserts in Mithila. In Mithila, food isn’t just sustenance; it’s a narrative, a cultural expression that speaks volumes about the people, the place, and the timeless traditions that define this enchanting region.

Tharu Cuisine

Tharu Cuisine revolves around the abundance of marshlands and rivers, featuring freshwater delights like fish, crabs, snails, and mussels. Ghonghi , a popular dish, comprises mud-water snails mixed with local spices, providing a tangy and spicy flavour. Pakuwa , a BBQ meat dish of pork and wild boar, stands out with its well-marinated spices. Gengta chutney , made from clean and cooked carp, serves as a versatile snack or accompaniment to other dishes. Chichar (Anadi rice) steamed during special occasions, showcases the sticky rice cultivated in the western plains. Sipi , a dish made from boiled freshwater mussels, offers a unique taste experience. Jhingiya machhari features freshwater shrimp cooked with local spices, while parewak sikar highlights pigeon meat in various preparations. Dhikri , a western Tharu cuisine made from rice flour, is steamed and shaped and often served during festivals. Bagiya , another dish made from rice flour, is flat and stuffed with lentils, spices, and boiled potatoes. Khariya , a popular and tasty dish, consists of rice, legumes, and spices wrapped in colocasia leaves and deep-fried. Sidhara , made from ground Sidhra fish, taro, colocasia steam, and spices, is shaped into cakes and sun-dried, often served as soup or curry. All in all, Tharu Cuisine offers a diverse and flavorful culinary experience in the Terai region, providing a unique taste of the local culture.

The Natural Wonders of The Terai

When appreciating indigenous communities like the Tharu people, one can’t separate them from the nature and wildlife they have been intrinsically connected to for generations. To understand these indigenous cultures, one must be in close contact with the flora and fauna that is interconnected with them. The Terai region is home to most of the natural parks and protected forests of Nepal. Most travelers go to Chitwan and partake in nature-based adventure activities, but an astute traveler should not dismiss the many equally thrilling areas.

Sahalesh Fulbari – Siraha

In the south of the Siraha district lies Salahesh Fulbari, a sanctuary where cultural sagas intertwine with a natural miracle. At the heart of this garden resides a delicate flower, a rare orchid known to unfurl its petals solely on the eve and the first day of the Nepali New Year, Baishakh. As you explore the expansive 14-acre space, the air carries the soft aroma of this unique blossom—a fragrant embodiment of the affection shared between Salahesh, a local deity, and his cherished Malini. To truly experience the miraculous phenomenon, align your visit with the New Year’s Eve celebration in Baishakh.

Koshi Tappu Wildlife Reserve

Established in 1976, the Koshi Tappu Wildlife Reserve is a 176 sq.km sanctuary that guards the last remaining population of wild buffalo, known as Arna (Bubalus arnee). Koshi Tappu’s charm lies in the Sapta Koshi, a key tributary of the Ganges, whose dynamic flooding during the monsoon is tamed by adjacent embankments.

The sanctuary is home to great biodiversity, with tall grasslands dominating the landscape. Local villagers benefit from these grasslands, collecting thatch grass for various purposes. Alongside sheltering the last 159 Arnas, this reserve is also home to Hog deer, Wild boar, Spotted deer, Blue bull, and Rock Python.

Likewise, Koshi Tappu is a haven for bird enthusiasts, boasting around 441 bird species, including 14 found nowhere else inthe world. The Koshi Barrage becomes a resting place for migratory birds, welcoming 87 winter and trans-Himalayan species. The Koshi River adds to the diversity with 80 fish and reptile species, including the endangered Gharial crocodile and Gangetic dolphin.

Journeying to Koshi Tappu is straightforward, with daily bus services from Kathmandu to Kakarbhitta and Biratnagar. However, travelling there from March to October can be the ideal time because, during these months, one can witness the migratory birds.

Parsa National Park

In the south-central lowlands of Terai, Nepal, Parsa National Park covers a vast 637.37 sq. km. This untouched sub-tropical jungle reflects the history of yesteryears, once a cherished retreat for the Rana Rulers. Inscribed as a wildlife reserve in 1984, and elevated to National Park status in 2017, Parsa National Park is aligned with the esteemed Chitwan National Park to the west and unfurls a distinctive diversity of landscapes and ecosystems.

Within the park, a flourishing flora and fauna find sanctuary. Sal forests dominate the landscape, riverine forests along the riverbanks shelter Khair and Silk cotton trees, and endangered species like the wild Asian elephant and Royal Bengal tiger roam freely. The avian population, numbering over 500 species, graces the skies with the White-Breasted Kingfisher, Paradise Flycatcher, and the endangered Giant Hornbill.

Autumn and winter can be the best time to explore the Parsa National Park. Although open during every season, spring and summer can be tiring due to the extremely hot temperatures.

Chitwan National Park

Nestled in the subtropical region of inner Terai, Chitwan National Park unveils itself across a vast 952.63 sq. km. Established in 1973, it achieved the distinguished status of a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1984, marking its profound importance in the world of conservation.

Chitwan National Park reveals varied diversity, from the slopes of the Churia hills to the flood plains of the Rapti, Reu, and Narayani Rivers. Seventy per cent of the park is embraced by Sal forests, while lush grasslands cloak another 20 per cent. This abundant habitat becomes a haven for a stunning array of wildlife—over 50 mammal species, more than 525 bird species, and a multitude of amphibians and reptiles find sanctuary here. The park stands tall as a sanctuary for endangered beings like the One-Horned Rhinoceros, Royal Bengal Tiger, wild elephant, and the elusive Bengal Florican.

For an optimal Chitwan National Park experience, late January becomes a window of opportunity as local villagers cut thatch grasses, enhancing wildlife viewing. Whether absorbing the informative displays at the visitor centre, exploring handicrafts at the women’s user groups’ souvenir shop, or engaging in wildlife activities from the park’s resorts, Chitwan National Park promises an enriching and unforgettable experience.

Banke – Baridya Complex

The Banke – Bardiya Complex is the collective name for two national parks in Banke and Bardiya.

Banke National Park

Banke National Park covers 550 square kilometres and unveils diverse ecosystems, from Sal forests to Riverine forests and sprawling grasslands. It’s home to various life forms, hosting 124 plant species, 34 mammals, over 300 birds, and many more. Protected species like the Royal Bengal Tiger and Asiatic Wild Elephant find refuge in its core. For those eager to explore this natural sanctuary, the best time is during the dry season, from October to April.

Bardiya National Park

Bardiya National Park is spread across 968 sq. km—the largest in this lowland region. A gem in Western Terai, its roots trace back to the humble Karnali Wildlife Reserve in 1976, evolving into the cherished Bardiya National Park we encounter today. Envisioned to protect diverse ecosystems and the habitats of the mighty tiger and its prey, this park epitomizes nature’s resilience. The Karnali River, coursing through the park, hosts the rare Gangetic dolphin, adding an ethereal touch to this natural haven.

For enthusiasts of wildlife, the Babai Valley within the park is a haven of biodiversity with wooded grasslands and riverine forests. Here, flagship species like Rhinos, tigers, and elephants roam freely in their natural domain. The valley also cradles the endangered gharial crocodile, marsh mugger, and the elusive Gangetic dolphin. Over 230 bird species, including the Bengal florican, lesser florican, and sarus crane, fly above the park.

For visitors, the headquarters offers a museum and a glimpse into the Tharu culture. Likewise, to embrace the wonders of Bardiya National Park, the months from October to early April stand as an ideal time, promising a dry and pleasant climate for an immersive wildlife experience.

Shuklaphanta National Park

Originally designated a Wildlife Reserve in 1976, Shuklaphanta National Park has grown to cover 305 sq km. Attaining the esteemed status of a National Park in 2016, Shuklaphanta reveals a landscape adorned with grasslands, waterholes, and wetlands shaped by the Mahakali River floodplain.

Situated in the Kanchanpur district, Shuklaphanta National Park shares its borders with India, extending north to the east-west highway. The Chaudhary River and Mahakali River shape its boundaries, and to the south, it connects with the Indian Tiger Reserve Kisanpur Wildlife Sanctuary.

Diverse vegetation adorns Shuklaphanta National Park, with Sal trees covering 52% of the protected area, wetlands claiming 10%, and vast grasslands spanning 30%. Alongside riverside forests and mixed forests, the park stands as a sanctuary for various species, including swamp deer, Bengal tigers, sloth bears, elephants, Indian leopards, Hispid Hares, and the great One-Horned Rhinoceros. A rich diversity of over 700 plant species contributes to the vibrant ecosystem.

For wildlife enthusiasts, the park hosts a thriving population of swamp deer, reaching 2301 individuals by 2014, along with around 20-25 wild elephants and 16 Bengal tigers, as per the 2018 census. The park’s water bodies harbour 28 fish species, while its skies are painted with 424 bird species, including Bengal floricans, dusky eagle owls, great slaty woodpeckers, chestnut-capped babblers, sarus cranes, and rusty-tailed flycatchers.

For those considering a visit to Shuklaphanta National Park, the ideal time is during the pleasant autumn months of October and November . This period offers agreeable weather, allowing travelers to witness the vibrant wildlife thriving in this flourishing sanctuary.

Terai – Stepping into the Limelight

“Terai is filled with indigenous communities, and what the Tharus have done in Chitwan and Bardiya speaks volumes. Cultural marketing has been centralized in these two places and most tourists think that the Terai is only made up of Chitwan and Bardiya,” says Mr. Subedi.

He believes that “the first step is to create an environment where other, perhaps more disadvantaged, communities like the Rajbhansi in eastern Terai, and the Mithila community in most parts of Madhesh Province, can present their unique personality to the rest of the world.”

Mr Subedi expressed his disappointment in the way in which the Terai is often overlooked when it comes to developing it as a touristic destination. He is right in stating that “indigenous people can not be blamed for not developing the Terai to its greatest potential.” He continues by saying that “most people belonging to indigenous communities are not in a well-to-do state, and to put the burden of marketing their culture is too heavy on them. However, their hospitable spirit makes them great hosts once they have the resources to welcome visitors.”

In this regard, Community Homestay Network has been working with indigenous communities in the Terai by giving educational workshops on how to create a welcoming space for foreign visitors. Their success can be seen in the many homestays that are now flourishing in the whereabouts of the incredibly lush national parks that make up the flatlands of Nepal.

To know more about the Community Homestays in the Terai and the experiences they offer, please follow these links.

Terai Experiences:

Jeep Safari at Suklaphanta National Park

Explore the outskirts of Chitwan National Park on a Cycle

Mithila Painting Wokshop

Tharu Cultural Program at Bhada

The Art of Tharu Cooking

Chitwan Private Canoe Ride, Barauli

Tags: Lumbini national parks nepal indigenous communities religious heritage Terai terai experiences wildlife

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- submit comment

ISSUE 8 | 2024

Related articles.

- 05 June, 2024

Into the World of Succulents With Sharad Bhimsaria

- 03 June, 2024

The Hidden Wonders of Nar Phu Valley: Beyond the Annapurna Circuit

- 23 May, 2024

Boudhanath Stupa

- 15 May, 2024

The Legendary Tale of Rato Machindranath Jatra

- 11 May, 2024

Breaking Down Barriers: Planeterra’s Global Community Tourism Network

- 02 May, 2024

Finding the Sacred Waters of Nepal

- 24 April, 2024

Biska Jatra Festival: An Iconic Chariot Tradition Uniting Thousands

- 15 April, 2024

Sustainable Tourism in Nepal: Inside the Mind of Shiva Dhakal

- 13 April, 2024

The Safest Asian Country for Rainbow Tourists

- 27 March, 2024

Hiti Tales: The stories behind Kathmandu’s ancient Water Spouts

The WWF is run at a local level by the following offices...

- AsiaPacific

- Central African Republic

- Central America

- Democratic Republic of the Congo

- European Policy Office

- Greater Mekong

- Hong Kong SAR

- Mediterranean

- Netherlands

- New Zealand

- Papua New Guinea

- Philippines

- Regional Office Africa

- South Africa

- South Pacific

- Switzerland

- United Arab Emirates

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Working Areas

- Terai Arc Landscape

The Terai is a stretch of lowlands in the southernmost part of Nepal. Often described as the rice bowl of the country, the region supports one of the most spectacular assemblages of large mammals in Asia such as the Bengal Tiger, the Greater One-Horned Rhinoceros, the common leopard, Asian elephant, and more. The protected areas of the Terai are also an important foothold for several of Asia's birds, reptiles, and freshwater fish, as well as several types of sal, riverine and mixed forests and grasslands. The ecosystem services provided by the region plays a major role in supporting the socioeconomic well-being and development of people in the Terai and extended Churia regions of Nepal.

Located in the shadows of the Himalayas, the trans-boundary Terai Arc belt stretches from Nepal’s Bagmati River in the east to India’s Yamuna River in the west, connecting 16 protected areas across both countries. In Nepal, the Terai Arc Landscape (TAL) covers a vast area of 24,710 sq. km with a network of six protected areas, forests, agricultural lands and wetlands, with over six million people depending on its forests for food, fuel, and medicine.

Conceptualized in 2001 by the Government of Nepal based on the tiger dispersal model, the landscape approach aimed to increase the persistence of tigers over a larger landscape, beyond initial source populations within protected areas. This laid the foundations for a shift from site-based conservation to a broader landscape based conservation approach expanding across Nepal’s corridors, with efforts ranging from forest restoration, reducing threats to species, safeguarding livelihoods, to effective transboundary cooperation between Nepal and India. Today, the transboundary Terai Arc Landscape is a critical tiger landscape that boasts over 880 tigers; with both Nepal and India having close to doubled their tiger numbers, a testament to the unwavering resolve and belief in the landscape approach by communities and conservation partners.

PROTECTED AREAS AND CORRIDORS

A key characteristic of TAL is the presence of eight corridors and two bottlenecks; a landscape conservation approach that facilitates wildlife dispersal between protected areas on either side of this transboundary landscape while also engaging local communities in forest restoration and management. Nepal - Parsa National Park, Chitwan National Park, Bardia National Park, Banke National Park, Shuklaphanta National Park, Krishnasaar Conservation Area, and the Barandabhar, Khata, Basanta, Laljhadi-Mohana, Brahmadev, Kamdi, Karnali Corridors. India - Valmiki Tiger Reserve, Sohagi Barwa Wildlife Sanctuary, Suhelwa Wildlife Sanctuary, Katarniaghat Wildlife Sanctuary, Dudhwa National Park, Pilibhit Tiger Reserve.

STRENGTHENING COMMUNITY STEWARDSHIP

A vital component of the TAL Program is building local community stewardship, focusing primarily on the community forestry model, good governance and sustainable livelihood diversification programs, making communities an integral part of biodiversity protection and restoration efforts. A key area of focus under the program is supporting marginalized and vulnerable communities in a significant way and promoting gender equality, while ensuring access to healthy forests in a sustainable manner.

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Ultimate Guide to the Nepali Terai

Discover the terai.

From the birthplace of the Buddha to wildlife safaris and culturally vibrant towns, there's a lot to see and do on the Terai. But with the exception of Chitwan National Park , most travelers to Nepal don't know much about the region. Indeed, until the mid-20th century, the Terai was largely an area of dense forest and malarial marshes, a natural border area between the plains of North India and the hills and mountains of Nepal. But the Terai played an important role in the development of Hinduism over many centuries: kings and queens lived in and around the Nepali Terai, as well as mythological deities, according to legend.

These days, the Terai houses much of Nepal's large-scale agriculture and industry, but also some of its most impressive national parks. Read on for practical tips to help you plan your trip to the region, and check out these five unique itineraries for travel inspiration in Nepal.

Planning Your Visit

The Terai is a large area, spanning over 13,000 square miles, or nearly a quarter of Nepal. While it's possible to take a bus from Kathmandu to many of the destinations listed below, the journey is long and not particularly comfortable. Most travelers choose to fly instead to airports like Nepalganj and Biratnagar , then make connections by car or bus. Due to travel logistics, you'll want at least a week to explore the area, or longer if you plan on visiting more than one of the highlights below. Read this article for more details on how much time to spend in Nepal.

A note on safety: while there's no cause for concern in popular tourist areas like Chitwan, the political situation on the Terai can be volatile. Cities like Janakpur regularly experience political unrest which can turn to violence, so check the situation before arriving. Tourists are never targets, but travelers should avoid getting caught up in demonstrations. Learn more here about solo travel and safety on kimkim's guided trips.

The climate of the Terai is more like that of North India than the hills and mountains of Nepal. So unless you're used to very hot weather, it's better to avoid visiting the Terai between April and October, when temperatures can soar above 100 degrees.

Since wildlife spotting in the national parks is one of the main attractions of the Terai, it's best to visit at prime animal-spotting times. Jungle animals are less active when it's hot out, so by visiting in fall and winter months (November through March), you're more likely to see tigers, rhinos, and birds in their natural habitats. This article explains why January is a great time to visit the Terai.

Getting There & Around

The Terai is connected by road and air to the rest of Nepal. Major transportation hubs are Bharatpur/Narayangadh , Nepalganj, Biratnagar, Siddharthanagar ( Bhairahawa ), and Janakpur. Although most travelers to Nepal fly internationally into Kathmandu, you could take the overland route from India and pass through the Terai. (The roads are generally bumpy and in poor condition, but they're not nauseatingly twisty like they can be in the mountains.)

When traveling between Kathmandu or Pokhara and the cities on the Terai, flying is by far the most comfortable option. You'll only need to spend 30 to 60 minutes in the air, instead of several hours in traffic jams and bumping over uncomfortable roads, as you would on a bus.

Highlights & Activities

Chitwan national park.

Established in 1973, Chitwan was Nepal's first national park. Bordered by Parsa National Park to the east (in Nepal) and Valmiki National Park to the south (in India), the large protected area is mostly comprised of forest, grasslands, and marshes, which are home to a large number of bird species, as well as rare slender-snouted gharial crocodiles, deer, elephants, tigers, and the one-horned rhinoceros. Your chance of seeing a rhino is especially high, as Chitwan has benefited from a series of successful anti-poaching campaigns: there are now more than 600 of these enormous creatures in the park. Chitwan also has one of the highest concentrations of Royal Bengal tigers in the world, though these are much more difficult to spot.

Chitwan is the most popular national park on the Terai, as it's easily accessible from both Kathmandu and Pokhara by car or bus. Bharatpur Airport is a 20-minute flight from Kathmandu. Travelers who want a more rugged but scenic experience can go overland, a journey of five to seven hours.

Learn more about here about the best things to do in Chitwan National Park.

Bardia National Park

A one-horned rhinoceros in Bardia National Park

Some say that Bardia National Park is how Chitwan used to be before the tourism infrastructure developed so much. In far western Nepal, Bardia is much more challenging to get to than Chitwan, so the park sees fewer visitors, there are fewer places to stay, and animals can be spotted in a more rugged and natural setting: indeed, you're much more likely to see tigers at Bardia than at Chitwan.

The Karnali River —Nepal's last remaining free-flowing, undammed river—runs through the park. A great way of visiting Bardia is as an add-on to a Karnali River expedition , in which you'll paddle in a kayak or white-water raft for the first week, then end near the park for more outdoor adventures. Bardia is also home to a wide variety of habitats, from dry slopes to grassy plains. In 2010, Banke National Park was established along Bardia's eastern border, creating the largest tiger conservation area in Asia. As well as tigers, you can see rhinos, spotted deer, the Ganges dolphin, and more.

To get to Bardia, fly to Nepalganj airport. From there, the park is still a three-to-four-hour bus journey. (You can also take a bus from Kathmandu, but it's not recommended.)

For more on Chitwan and Bardia National Parks, read this article .

Koshi Tappu Wildlife Sanctuary

Sarus Cranes in the Bardia National Park

On Nepal's eastern Terai, the Koshi Tappu Wildlife Sanctuary is a magnet for bird enthusiasts. The wetland area, located in the floodplain of the Sapta Koshi River , is home to almost 500 bird species, including storks, ducks, geese, eagles, terns, lapwings, and kingfishers. There's also an enormous variety of fish, plus elephants, deer, and the Ganges dolphin. The terrain is mostly mudflats, reed beds, and freshwater marshes. Tented camps cater specifically to bird watchers: don't forget your binoculars!

The Koshi Tappu Reserve is about a 90-minute drive from Biratnagar Airport in eastern Nepal. Buses from Kathmandu take a minimum of 12 hours.

A Buddhist stupa at Lumbini

The small, otherwise unremarkable town of Lumbini on the western Terai has one extraordinary claim to fame: it's the birthplace of the Buddha. Archaeological evidence suggests that this was the place where Prince Siddhartha Gautama Buddha was born in 623 BCE. Lumbini was lost to history for many centuries, then rediscovered again in the 19th century by Nepali officials and Raj archaeologists.

Today, Lumbini is home to monasteries and Buddhist centers built by various countries with strong Buddhist traditions, so touring the place is like taking a tour of international Buddhist architectural traditions. It's a UNESCO World Heritage Site and a major place of pilgrimage for Buddhists from all around the world.

The easiest way to get to Lumbini is to fly to Bhairahawa from Kathmandu. From Pokhara, it's a five-hour drive. Read more about Lumbini in this ultimate guide.

Janakpur's Janaki Mandir (Photo credit: Elen Turner)

Janakpur ( also called Janakpurdham ) is an ancient city in the eastern section of the Terai. A Hindu pilgrimage spot, Janakpur is believed to be where Hindu Lord Rama's wife Sita (also called Janaki, hence the city's name) was born. Janakpur’s Janaki Mandir temple is unique in Nepal, combining elements of Mughal and Rajput design.

Fans of Nepali art should visit the Janakpur Women's Development Centre , an arts center surrounded by farmland on the edge of the city. The local Maithili women have turned their colorful and stylized traditional painting into a source of profit: you'll see their work at fair trade and handicraft shops in Kathmandu. Stop by the center to watch them at work.

Janakpur is also the terminus for Nepal's only passenger railway line, which runs between Jainagar and Janakpur. It's not a major attraction, but railway enthusiasts won't want to miss it.

Discover the best of Nepal on this 16-day itinerary.

Where to Stay

Many visitors base themselves in Kathmandu and take short flights to airports in the Terai to make connections to national parks, wildlife-viewing hot spots, and pilgrimage sites.

If you're headed to Chitwan National Park, you'll probably stay in or around the town of Sauraha , which has many accommodation options and tour operators. Travel agencies offer various kinds of safaris, but the safest and most ethical is to travel by Jeep. For a more peaceful and less touristy experience, check out the village of Barauli , near the western edge of the park. Accommodation ranges from simple guesthouses and homestays to luxury lodges—read more about the best jungle lodges in Nepal in this article .

In Bardia National Park, try a jungle lodge like Tiger Tops Karnali Lodge or Forest Hideaway Hotel & Cottages . Visiting Koshi Tappu Wildlife Sanctuary ? Try Koshi Tappu Reserve Camp for a convenient overnight option. There are several nice resorts near Lumbini, including Lumbini Village Lodge , while down-to-earth Hotel Welcome is a solid choice in Janakpur.

Learn more about unique lodging options in Nepal here .

Read more on our privacy policy

Mitigating the Impacts of Climate Change in Nepal’s Terai Region: Sustainable Solutions for a Resilient Future

28 August 2023, NIICE Commentary 8793 Keshav Verma & Sheetal Arya

The Terai region is a pivotal part of Nepal in many ways, since it is essential to the country’s economy, politics, and culture. Nearly half of Nepal’s population calls this fertile belt home; as a result, it’s a thriving demographic centre where many different peoples and cultures live peacefully. Nepal’s legacy has been enhanced by this cultural tapestry, which also fosters mutual appreciation and unity among people of different backgrounds. The region situated in the southern portion of the nation, characterised by its flat and fertile terrain, is now undergoing the effects of climate change

Challenges in the Terai Region

The Terai area of Nepal, noted for its lush farmland and dynamic people, is facing a multidimensional challenge posed by climate change. This environmental hazard manifests itself in a variety of ways, each posing a distinct set of problems to the region’s social, economic, and biological landscape.

Changes in precipitation patterns have brought about a serious trend in the Terai region – the depletion of groundwater supplies. As irregular rainfall causes tube wells to dry up, communities are being forced to draw from deeper reservoirs. Unfortunately, arsenic is often found in deeper groundwater. This pollution has caused a health problem for individuals who rely on these water sources. Furthermore, increased river volumes caused by shifting precipitation patterns have had serious repercussions. Shifting river channels damage not just the natural environment, but also human settlements, roads, bridges, and agricultural fields, putting the Terai’s infrastructure at risk.

Droughts have emerged as a dangerous foe, causing crop failures and decreasing output. Farmers in certain places have been forced to quit their properties, which have become barren due to a lack of irrigation infrastructure. As safe drinking water becomes more limited, the cascading impacts of drought affect daily life. Droughts cause populations to travel considerable distances to meet their daily water demands, worsening the battle for life.

The Terai’s flood plains, which are famous for their production, are subject to catastrophic monsoon floods and river bank erosion. These extended floods harm crops and dump sand in fields, making them less productive. Aside from agricultural losses, such circumstances foster the spread of waterborne illnesses such as malaria, dengue fever, dysentery, and cholera. This twin danger to livelihoods and public health puts enormous strain on Terai communities. Once-predictable seasonal cycles in the area are now a thing of the past, as climate-induced temperature and rainfall variations disturb historical rhythms. The unpredictability and uncertainty of these developments has a direct influence on the lives of Terai inhabitants. Agriculture, a key component of the region’s economy, is severely impacted, making planning and resource management more difficult. This unpredictability, along with the threat of climate change, throws a pall over the Terai people’s quality of life and capacity to continue their livelihoods.

Climate change is intensifying societal conflicts and disputes over natural resource access in Nepal’s Terai area, according to a research published by the Overseas Development Institute (2017). Communities are at conflict over irrigation infrastructure, land access, and forest management, further straining already strained relationships. The rising insecurity of the young male population has resulted in out-migration, leaving women with more obligations and, in some circumstances, leading to domestic violence. These issues have far-reaching consequences for the Terai’s social fabric and community dynamics.

Mitigating the impacts of Climate Change

Nepal’s Terai region faces formidable climate change challenges, and international support as well as domestic measures are essential in building resilience and mitigating the impact of these challenges.

International Community

Nepal’s efforts to confront the formidable challenges posed by climate change in its Terai region rely heavily on international assistance. Investments and contributions from international organisations and donor nations are indispensable for financing climate resilience initiatives, such as the development of renewable energy infrastructure and sustainable agricultural practises. In addition, the transfer of advanced technology, the augmentation of capacity, and collaborative research projects equip Nepal with the necessary knowledge and capabilities to effectively combat the effects of climate change. Together with advocacy campaigns, the participation of international climate finance mechanisms effectively allocates resources and heightens awareness. Concurrently, cross-border collaboration ensures synchronised administration of trans-boundary water resources, addressing a significant concern in Nepal’s strategy for adapting to climate change. Community involvement is of the utmost importance, especially the empowerment of local constituents and women, given their pivotal positions in agricultural activities and domestic administration. In conclusion, international collaboration fosters resilience, facilitates policy formulation, and supports sustainable development initiatives, thereby bolstering the prospects for a climate-resilient future in Nepal’s Terai region.

Domestic Measures

The development of the Terai region’s capability for managing natural resources should be Nepal’s top priority. Enhancing the equitable and sustainable use of natural resources including land, water, and forests is part of this. It will be essential to establish responsible and transparent procedures for managing resources that include marginalised groups and local communities. While it’s a good start to make sure that the area of cultivated land determines a landowner’s access to water resources, fair distribution should also be taken into account to prevent disputes over resource distribution.

Secondly, Nepal has to put climate change adaption strategies that support social cohesiveness and peace into practise. This entails creating initiatives and regulations that promote collaboration and trust among various community members in addition to increasing resistance to the effects of climate change. Promoting resource-efficient, sustainable farming methods, for example, may lessen rivalry and diffuse tensions amongst farmers. Protecting indigenous people’s rights and involving local populations and in the decision-making process is also crucial to ensuring that adaptation efforts take into account their particular vulnerabilities and needs, particularly those of women, youth, and ethnic minorities.

Thirdly, it is critical to assist sustainable and climate-resilient livelihoods in conflict-affected regions. Targeted investments in industries like small businesses, renewable energy, and agriculture may help accomplish this. These programmes ought to minimise environmental damage while offering prospects for revenue. In order to ensure that marginalised people have a voice in creating these livelihood programmes and achieve more fair results, a participatory approach is also essential. Subsequently, Nepal has to evaluate the social and gender aspects of its attempts to mitigate climate change. Promoting gender equality and empowerment should be the main goal of initiatives rather than just include women and other marginalised groups. This entails locating and removing obstacles to social inclusion, such as restricted access to positions in decision-making, education, and resources. Using a gender-responsive strategy will help the Terai region’s climate security programmes become more sustainable and successful.

The Terai region of Nepal is at a crossroads due to the escalating effects of climate change. To ensure a resilient future, a comprehensive strategy that incorporates community empowerment, sustainable land management, and robust collaborations is required. Preserving and restoring natural habitats will simultaneously mitigate environmental degradation. Importantly, partnerships between government, non-governmental organisations, and the private sector can provide the necessary resources and expertise to execute infrastructure initiatives that are climate-resilient. The Terai region can not only adapt to the challenges of climate change, but also thrive, assuring a sustainable and resilient future for generations to come through collective efforts.

Keshav Verma is a PhD Scholar at Department of International Studies, CHRIST (Deemed to be University), India and Sheetal Arya is a PhD Scholar at School of International Studies at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India.

Share This Publication

About the author: niice.

Related Posts

Environmental Espionage: Unveiling the Green Agenda

A New Start for China-Japan-South Korea Trilateral Cooperation

Navigating the Intersection of Technology and Governance

- Latest news

- Media centre

- News archive

- Nobel Peace Prize shortlist

- Upcoming events

- Recorded events

- Annual Peace Address

- Event archive

- Project archive

- Research groups

- Latest publications

- Publication archive

- Current staff

- Alphabetical list

- Global Fellows

- Practitioners in Residence

- Replication data

- Annual reports

- How to find

Nepal's Terai: Constructing an Ethnic Conflict

Miklian, Jason (2009) Nepal's Terai: Constructing an Ethnic Conflict [South Asia Briefing Paper #1]. PRIO Paper . Oslo: PRIO.

After the government of Nepal signed a peace agreement with the Communist Party of Nepal-Maoist in 2006 to end a 10 year civil war, local and international observers were surprised to see new fighting erupt in the Terai region of southern Nepal. The violence, however, was initiated not by either party to the civil war but by groups targeting both the state and the Maoists, polarizing citizens along ethnic issues largely unaddressed during the civil war.

In 2007, three of these groups joined forces to create a coalition called the United Democratic Madhesi Front (UDMF).The UDMF’s stated goal is to transform the Terai into a single autonomous province of Madhes. To accomplish this, the UDMF has redefined the identity of those people living in the Terai and those outside of it, in turn exacerbating ethnic division and violence at the grassroots level.

This narrative has benefited the UDMF by binding otherwise disparate ethnic groups together, constructing a history of the Terai that makes it their exclusive political domain, polarizing society into a ‘Madhesi vs. Pahadi (Kathmandu valley)' dichotomy that scapegoats elite ethnicities for local problems, and dissociating Madhesi political leaders from their Maoist past. The UDMF uses political violence to draw attention to the plight of those from the Madhesi ethnic group, signing two peace agreements over the past year with political leaders in Kathmandu to push reform and articulate their grievances.

However, implementation of the agreements is complex and problematic. Nepal’s government is in a difficult spot: it committed to UDMF directives that, if implemented in their entirety, will likely increase conflict within the Terai while simultaneously fracturing the state and weakening Nepal’s fragile institutions.

.jpg?x=600&y=1200&m=Scale&hp=Center&vp=Center&ho=0&vo=0&)

Jason Miklian

The Western Terai Travel Guide

Book your individual trip , stress-free with local travel experts

Select Month

- roughguides.com

- the-western-terai

- Travel guide

- Itineraries

- Local Experts

- Travel Advice

- Accommodation

Plan your tailor-made trip with a local expert

Book securely with money-back guarantee

Travel stress-free with local assistance and 24/7 support

We chose this trip specifically as we are regular hill walkers and had always wanted to hike in the Everest region of Nepal, but had been put off by tales ...

A narrow strip of flatland extending along the length of Nepal’s southern border, the Terai was originally covered in thick, malarial jungle. In the 1950s, however, the government identified the southern plains as a major growth area to relieve population pressure in the hills, and, with the help of liberal quantities of DDT, brought malaria under control. Since then, the jungle has been methodically cleared and the Terai has emerged as Nepal’s most productive region, accounting for more than fifty percent of its GDP and supporting about half its population.

Cycling through the Terai

Lumbini terai, the far west.

The jungle barrier that once insulated Nepal from Indian influences as effectively as the Himalayas had guarded the north, making possible the development of a uniquely Nepali culture, has disappeared. An unmistakeable Indian quality now pervades the Terai, as evidenced by the avid mercantilism of the border bazaars, the chewing of betel , the mosques and orthodox Brahmanism, the jute mills and sugar refineries, and the many roads and irrigation projects built with Indian aid.

Fortunately, the government has set aside sizeable chunks of the Western Terai in the form of national parks and reserves, which remain among the finest w ildlife and bird havens on the subcontinent. Dense riverine forest provides cover for predators like tigers and leopards; swampy grasslands make the perfect habitat for rhinos; and vast, tall stands of sal , the Terai’s most common tree, shelter huge herds of deer. Of the region’s wildlife parks, the deservedly popular Chitwan is the richest in game and the most accessible, but if you’re willing to invest some extra effort, Bardia and Sukla Phanta further to the west make quieter alternatives. The region’s other claim to fame is historical: the Buddha was born 2500 years ago at Lumbini . Nearby, important archeological discoveries have also been made at Tilaurakot .

Four border crossings in the western Terai are open to foreigners. As it’s on the most direct route between Kathmandu and Varanasi, and fits in well with visits to Lumbini and Chitwan, Sonauli is the most heavily used. Less popular are the crossing points south of Nepalgunj or Dhangadhi. Alternatively, on the far western frontier is Mahendra Nagar , only around twelve hours from Delhi, but an arduous journey to Kathmandu.

The weather in the Terai is at its best from October to January – the days are pleasantly milder during the latter half of this period, though the nights and mornings can be surprisingly chilly and damp. However, wildlife viewing gets much better after the thatch has been cut, from late January, by which time the temperatures are starting to warm up again. It gets really hot in April, May and June. From July to September, the monsoon brings mosquitoes, malaria and leeches, and makes a lot of the more minor, unpaved roads very muddy and difficult to pass, and some rivers burst their banks.

Travel ideas for Nepal, created by local experts

11 days / from 3248 USD

Exclusive Everest

Trek in the Everest region of Nepal's Himalayas, absorbing spectacular views at every step, including Everest rising above the Nuptse Ridge, Lhotse, the iconic peak of Ama Dablam and other Himalayan giants too. Top this off with a shot of warm Nepalese culture for an experience of a lifetime.

13 days / from 1950 USD

Himalayan Family Adventure

Experience Nepal's hill villages and jungle lowlands as you embark on a family-friendly adventure of a lifetime. Expect mini mountain treks, overnight camps, river rafting and wildlife safaris. Come here for action, stunning mountain scenery and a look around bustling Kathmandu too.

13 days / from 2200 USD

The UNESCO World Heritage Sites of Nepal

Set in the heart of the Himalayas, the landlocked South-Asian country of Nepal is home to a wealth of UNESCO World Heritage Sites. From wild jungles to ancient civilisations, Nepal offers a combination of history, culture and nature; perfect for the most well-seasoned of travellers.

Chitwan is the name not only of Nepal’s most visited national park but also of the surrounding dun valley and administrative district. The name means “Heart of the Jungle” – a description that, sadly, now holds true only for the lands protected within the park and community forests. Yet, the rest of the valley – though it’s been reduced to a flat, furrowed plain – still provides fascinating vignettes of a rural lifestyle. Truly ugly development is confined to the wayside conurbation of Narayangadh/Bharatpur , and even this has left the nearby holy site of Devghat so far unscathed.

The best – and worst – aspects of Chitwan National Park are that it can be visited easily and inexpensively. It is high on the list of “things to do in Nepal”, so unless you go during the steamy season you’ll share your experience with a lot of other people. If you want to steer clear of the crowds, and don’t mind making a little extra effort, try avoiding the much-touted tourist village of Sauraha and base yourself in one of two villages along the park’s northern boundary, just west. Ghatgain and Meghauli are much quieter and less developed than Sauraha, but also have guesthouses, guides, elephants and entry checkposts (though jeeps are more difficult to come by). You can also do a jungle trek from Sauraha to either village. Or, if you’ve got the money ($200–350 per night per person, all-in), opt for pampered seclusion at any one of the luxury lodges and camps inside the park itself.

Asian elephants

In Nepal and throughout southern Asia, elephants have been used as ceremonial transportation and beasts of burden for thousands of years, earning them a cherished place in the culture – witness the popularity of elephant-headed Ganesh, the darling of the Hindu pantheon. Thanks to this symbiosis with man, Asian elephants (unlike their African cousins) survive mainly as a domesticated species, even as their wild habitat has all but vanished.

With brains four times the size of humans’, elephants are reckoned to be as intelligent as dolphins. What we see as a herd is in fact a complex social structure, consisting of bonded pairs and a fluid hierarchy. In the wild, herds typically consist of fifteen to thirty females and one old bull, and are usually led by a senior female; other bulls live singly or in bachelor herds. Though they appear docile, elephants have strongly individual personalities and moods. They can learn dozens of commands, but they won’t obey just anyone; as any handler will tell you, you can’t make an elephant do what it doesn’t want to do. That they submit to such apparently cruel head-thumping by drivers seems to have more to do with thick skulls than obedience.

Asian elephants are smaller than those of the African species, but still formidable. A bull can grow up to three metres high and weigh four tons, although larger individuals are known to exist. An average day’s intake is 200 litres of water and 225kg of fodder – and if you think that’s impressive, wait till you see it come back out again. All that eating wears down teeth fast: an average elephant goes through six sets in its lifetime, each more durable than the last. The trunk is controlled by an estimated forty thousand muscles, enabling its owner to eat, drink, cuddle and even manipulate simple tools (such as a stick for scratching). Though up to 2.5cm thick, an elephant’s skin is still very sensitive, and it will often take mud or dust baths to protect against insects. Life expectancy is about 75 years and, much the same as with humans, an elephant’s working life can be expected to run from its mid-teens to its mid-fifties; training begins at about age five.

Bis Hajaar Tal

Large patches of jungle still exist outside the park in Chitwan’s heavily populated buffer zone, albeit in a less pristine state. The areas designated as community forests were originally conceived to reduce the need for residents of this critical strip to go into the park to gather wood, thatch and other resources, but they’re now nearly as rich in flora and fauna as Chitwan itself. Two forests, Baghmara and Kumroj on the outskirts of Sauraha, offer alternatives to entering the park itself, and the elephant rides , particularly, are often no less rewarding.

Another community forest, the Bis Hajaar Tal (“Twenty Thousand Lakes”) wetland area, is one of the best areas – inside or outside the park – for birdwatching , though the growth of water hyacinth has reduced bird numbers. There are plenty of animals, but it’s one of the few areas of jungle that can be visited independently with relative safety – though, as always, you’ll probably get more out of it in the company of a good guide. Nepal’s second largest natural wetland, the area, provides an important corridor for animals migrating between the Terai and the hills. The name refers to a maze of marshy oxbow lakes, many of them already filled in, well hidden among mature sal trees. The area teems with birds, including storks, kingfishers, eagles and the huge Lesser Adjutant. The forest starts just west of Baghmara and the Elephant Breeding Project and reaches its marshy climax about 5km northwest of there.

Chitwan: a seesaw battle for survival

While Chitwan’s forest ecosystem is healthy at the moment, pollution from upstream industries is endangering the rivers that flow into it: gangetic dolphins have disappeared from the Narayani, and gharial crocodiles hang on only thanks to human intervention. With more than three hundred thousand people now inhabiting the Chitwan Valley, human population growth represents an even graver danger in the long term. Tourism has picked up again, after dropping off considerably during the civil war – the key issue will be to ensure the resultant development is handled in a sensitive, sustainable manner.

The key to safeguarding Chitwan, everyone agrees, is to win the support of local people, and there’s some indication that this is happening. Several organizations run awareness-raising programmes, particularly targeting children, but there has been little government action in this regard. Another pressing problem for the area – and the country as a whole – is a lack of investment in infrastructure, notably roads.

Communities living in the 750 square kilometres around the park receive some state financial support, and compensation is paid for damage caused by wild animals (safety has improved but one or two people are still killed each year). The National Trust for Nature Conservation ( w www.ntnc.org.np ), funded by several international agencies, is active in general community development efforts such as building schools, health posts, water taps and appropriate technology facilities, as well as in conservation education and training for guides and lodge-owners. They have also been instrumental in helping set up community forests around Chitwan and the prospect of collecting hefty entrance fees from these is turning local people into zealous guardians of the environment.

Chitwan National Park

Whether CHITWAN NATIONAL PARK has been blessed or cursed by its own riches is an open question. The coexistence of the valley’s people and wildlife has rarely been easy or harmonious, even before the creation of the national park. In the era of the trigger-happy maharajas, the relationship was at least simple: when Jang Bahadur Rana overthrew the Shah dynasty in 1846, one of his first actions was to make Chitwan a private hunting reserve. The following century saw some truly hideous hunts – during an eleven-day shoot in 1911, a visiting King George V killed 39 tigers and 18 rhinos.

Still, the Ranas’ patronage afforded Chitwan a degree of protection, as did malaria. But in the early 1950s, the Ranas were thrown out, the monarchy was restored, and the new government launched its malaria-control programme . Settlers poured in and poaching went unpoliced – rhinos, whose horns were (and still are) valued for Chinese medicine and Yemeni knife handles, were especially hard hit. By 1960, the human population of the valley had trebled to one hundred thousand, while the number of rhinos had plummeted from one thousand to two hundred. With the Asian one-horned rhino on the verge of extinction, Nepal emerged as an unlikely hero in one of conservation’s finest hours. In 1962, Chitwan was set aside as a rhino sanctuary (becoming Nepal’s first national park in 1973); and, despite the endless hype about tigers, rhinos are Chitwan’s biggest attraction and its greatest triumph. Chitwan now boasts around 508 rhinos , and the park authorities have felt confident enough to relocate some to Bardia National Park. A number were killed by poachers during the conflict but now the soldiers are back at their posts in the park the problem has declined (though it has not been eradicated).

There are thought to be around 122 tigers in the park. Chitwan also supports at least four hundred gaur (Indian bison) and provides a part-time home to as many as 45 wild elephants , who roam between here and India. Altogether, 56 mammalian species are found in the park, including sloth bear, leopard, langur and four kinds of deer. Chitwan is also Nepal’s most important sanctuary for birds , with more than five hundred species recorded, and there are also two types of crocodile and more than one hundred and fifty types of butterfly .

Visitors can only enter the national park accompanied by a guide , and guides for activities such as jungle walks, elephant rides, canoe trips and jeep safaris vie for your attention once you arrive in the vicinity of the park. Note, however, that promises of “safari adventure” in Chitwan can be misleading. While the park’s wildlife is astoundingly concentrated, the dense vegetation doesn’t allow the easy sightings you get in the savannas of Africa (especially in autumn, when the grass is high). Many guides assume everyone wants to see only tigers and rhinos, but there are any number of birds and other animals to spot which the typical safari package may not cover, not to mention the many different ways simply to experience the luxuriant, teeming jungle: elephant rides , jeep tours , canoe trips and jungle walks each give a different slant.

DEVGHAT (or Deoghat), 5km northwest of Narayangadh, is many people’s idea of a great place to die. An astonishingly tranquil spot, it stands where the wooded hills meet the shimmering plains, and the Trisuli and the Kali Gandaki rivers merge to form the Narayani, a major tributary of the Ganga (Ganges). Some say Sita, heroine of the Ramayana, died here. The ashes of King Mahendra were sprinkled at this sacred tribeni (a confluence of three rivers: wherever two rivers meet, a third, spiritual one is believed to join them), and scores of sunyasan , those who have renounced the world, patiently live out their last days here hoping to achieve an equally auspicious death and rebirth. Many retire to Devghat to avoid being a burden to their children, to escape ungrateful offspring, or because they have no children to look after them in their old age and perform the necessary rites when they die. Pujari (priests) also practise here and often take in young candidates for the priesthood as resident students. Suggestions that a hydroelectric project might be built just downstream of the confluence seem, fortunately, to have fallen by the wayside.

Dozens of small shrines lie dotted around the village, but you come here more for the atmosphere than the sights. Vaishnavas (followers of Vishnu) congregate at Devghat’s largest and newest temple, the central shikra -style Harihar Mandir , founded in 1998 by the famed guru Shaktya Prakash Ananda of Haridwar. Shaivas (followers of Shiva) dominate the area overlooking the confluence at the western edge of the village.

The confluence

To reach the confluence, turn left at a prominent chautaara at the top of the path leading through the village: Galeshwar Ashram , on your right as you walk down the steps, and Aghori Ashram , further downhill on the right, are named after two recently deceased holy men. One of them, the one-armed Aghori Baba, was a follower of the extreme Aghori tradition and was often referred to as the “Crazy Baba”, claiming to have cut off his own arm after being instructed to do so in a dream. Various paths lead upstream of the confluence, eventually arriving at Sita Gupha , a sacred cave that is closed except on Makar Sankranti, and Chakrabarti Mandir , a shady temple area housing a famous shaligram that locals say is growing.

Gharial crocodiles

The world’s longest crocodile – adults can grow to more than 7m from nose to tail – the gharial is an awesome fishing machine. Its slender, broom-like snout, which bristles with a fine mesh of teeth, snaps shut on its prey like a spring-loaded trap. Unfortunately, its eggs are regarded as a delicacy, and males are hunted for their bulb-like snouts, believed to have medicinal powers.

In the mid-1970s, there were only 1300 gharials left. Chitwan’s project was set up in 1977 to incubate eggs under controlled conditions, thus upping the survival rate – previously only one percent in the wild – to as high as 75 percent. The majority of hatchlings are released into the wild after three years, when they reach 1.2m in length; more than five hundred have been released so far into the Narayani, Koshi, Karnali and Babai rivers. Having been given this head start, however, the hatchlings must then survive a growing list of dangers, which now include not only hunters but also untreated effluents from upstream industries and a scarcity of food caused by the lack of fish ladders on a dam downstream in India. Counts indicate that captive-raised gharials now outnumber wild ones on the Narayani, which suggests that without constant artificial augmentation of their numbers they would soon become extinct. A few turtles can also be seen at the breeding centre.

Park people

A procession of bicycle-toting locals crossing the Rapti at dusk, wading or being ferried across the river before disappearing into the trees of the national park on the far side, was once a familiar Sauraha scene.

In the late 1990s, more than 20,000 people lived within the park boundaries, mainly in Padampur , the area immediately opposite Sauraha. Inevitably, villagers were forced to compete with the park’s animal population for forest resources and the ever-increasing number of wild animals would regularly raid farmers’ crops, causing widespread damage and even deaths. The situation became increasingly unsustainable, and the government finally decided to relocate Padampur’s villagers from the park itself to Saguntole, around 10km north of the national park, which extends from Bis Hajaar Tal towards the hills of the Mahabharat Lekh. This programme has now left Chitwan itself free of human settlement.

This has inevitably raised troubling issues. Foremost is that people have been forced to leave their homes to make way for animals and the tourists who come to see them. A great deal of knowledge, and the cultural beliefs that go with it, has been, if not lost, then undoubtedly threatened. There are concerns about water supply in Saguntole and allegations of corruption surround the villagers’ compensation payments. The move could also accelerate the destruction of a vital wildlife corridor, one of the few that still connects the plains and the hills.

Spectacularly situated on the banks of the Rapti River, opposite a prime area of jungle, SAURAHA (pronounced So -ruh-hah) is one of those unstoppably successful destinations at which Nepal seems to excel. In some lights it looks like the archetypal budget safari village, with its lodges spread out along dusty roads at the edge of the forest; at other times, you could half-close your eyes and imagine yourself in a mini Thamel. While there’s still a lot to recommend it, not least the ease of access into the park, Sauraha loses a little more of what once made it so enjoyable each year: buildings are springing up at an alarming rate.

The fast-changing cluster of shops and hotels that make up Sauraha “ village ” constitutes most of the action, though there’s little to do except shop, eat and plan excursions.

In addition to the Tharu village tours, you can also learn about real Terai village life by hopping on a bike and just getting lost on the back roads to the east and west of Sauraha. Stopping at any village and asking “chiya paunchha?” (where can I get a cup of tea?) will usually attract enough attention to get you introduced to someone.

In November, when the rice is harvested, you’ll be able to watch villagers cutting the stems, tying them into sheaves and threshing them; or, since it’s such a busy time of year, piling them in big stacks to await threshing. January is thatch-gathering time, when huge bundles are put by until a slack time before the monsoon allows time to repair roofs. In early March, the mustard, lentils and wheat that were planted after the rice crop are ready; maize is then planted, to be harvested in July for animal fodder, flour and meal. Rice is seeded in dense starter-plots in March, to be transplanted into separate paddy fields in April.

From Sauraha, the most fertile country for exploration lies to the east: heading towards Tadi along the eastern side of the village, turn right (east) at the intersection marked by a health post and you can follow that road all the way to Parsa , 8km away on the Mahendra Highway, with many side roads to villages en route. Given a full day and a good bike or motorcycle, you could continue eastwards from Parsa along the highway for another 10km, and just before Bhandaara turn left onto a track leading to Baireni , a particularly well-preserved Tharu village. From Lothar , another 10km east of Bhandaara, you can follow a trail upstream to reach the waterfalls on the Lothar Khola, a contemplative spot with a healthy measure of birdlife.

For a short ride west of Sauraha, first head north for 3km and take the first left after the river crossing, which brings you to the authentic Tharu villages of Baghmara and Hardi . If you’re game for a longer journey, pedal to Tadi and west along the Mahendra Highway to Tikauli. From there, the canal road through Bis Hajaar Tal leads about 10km through beautiful forest to Gita Nagar , where you join the Bharatpur–Jagatpur road, with almost unlimited possibilities. A good route is to continue due west from Jagatpur on dirt roads all the way to Meghauli, though you may have to ford a river on the way, impossible on a motorbike from June/July until at least late November. Don’t overlook the possibility of an outing to Devghat, either.