Human rights abuses are happening right now – start a monthly gift today.

- Videos & Photos

- Take Action

Why Sex Work Should Be Decriminalized

Questions and Answers

Share this via Facebook Share this via X Share this via WhatsApp Share this via Email Other ways to share Share this via LinkedIn Share this via Reddit Share this via Telegram Share this via Printer

Human Rights Watch has conducted research on sex work around the world, including in Cambodia , China , Tanzania , the United States , and most recently, South Africa . The research, including extensive consultations with sex workers and organizations that work on the issue, has shaped the Human Rights Watch policy on sex work: Human Rights Watch supports the full decriminalization of consensual adult sex work.

Why is criminalization of sex work a human rights issue?

Criminalizing adult, voluntary, and consensual sex – including the commercial exchange of sexual services – is incompatible with the human right to personal autonomy and privacy. In short – a government should not be telling consenting adults who they can have sexual relations with and on what terms.

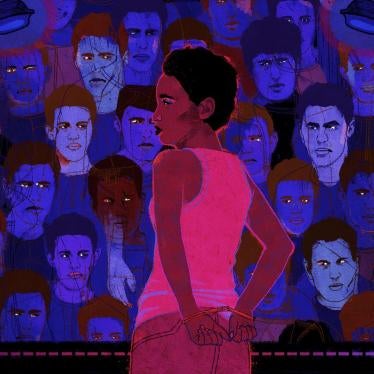

Criminalization exposes sex workers to abuse and exploitation by law enforcement officials, such as police officers. Human Rights Watch has documented that, in criminalized environments, police officers harass sex workers, extort bribes, and physically and verbally abuse sex workers, or even rape or coerce sex from them.

Human Rights Watch has consistently found in research across various countries that criminalization makes sex workers more vulnerable to violence, including rape, assault, and murder, by attackers who see sex workers as easy targets because they are stigmatized and unlikely to receive help from the police. Criminalization may also force sex workers to work in unsafe locations to avoid the police.

Criminalization consistently undermines sex workers’ ability to seek justice for crimes against them. Sex workers in South Africa, for example, said they did not report armed robbery or rape to the police. They said that they are afraid of being arrested because their work is illegal and that their experience with police is of being harassed or profiled and arrested, or laughed at or not taken seriously. Even when they report crimes, sex workers may not be willing to testify in court against their assailants and rapists for fear of facing sanctions or further abuse because of their work and status.

UNAIDS , public health experts , sex worker organizations , and other human rights organizations have found that criminalization of sex work also has a negative effect on sex workers’ right to health. In one example, Human Rights Watch found in a 2012 report, “Sex Workers at Risk: Condoms as Evidence of Prostitution in Four US Cities,” that police and prosecutors used a sex worker’s possession of condoms as evidence to support prostitution charges. The practice left sex workers reluctant to carry condoms for fear of arrest, forcing them to engage in sex without protection and putting them at heightened risk of contracting HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases.

Criminalization also has a negative effect on other human rights. In countries that ban sex work, sex workers are less likely to be able to organize as workers, advocate for their rights, or to work together to support and protect themselves.

How does decriminalizing sex work help protect sex workers?

Decriminalizing sex work maximizes sex workers’ legal protection and their ability to exercise other key rights, including to justice and health care. Legal recognition of sex workers and their occupation maximizes their protection, dignity, and equality. This is an important step toward destigmatizing sex work.

Does decriminalizing sex work encourage other human rights violations such as human trafficking and sexual exploitation of children?

Sex work is the consensual exchange of sex between adults. Human trafficking and sexual exploitation of children are separate issues. They are both serious human rights abuses and crimes and should always be investigated and prosecuted.

Laws that clearly distinguish between sex work and crimes like human trafficking and sexual exploitation of children help protect both sex workers and crime victims. Sex workers may be in a position to have important information about crimes such as human trafficking and sexual exploitation of children, but unless the work they themselves do is not treated as criminal, they are unlikely to feel safe reporting this information to the police.

What should governments do?

Governments should fully decriminalize sex work and ensure that sex workers do not face discrimination in law or practice. They should also strengthen services for sex workers and ensure that they have safe working conditions and access to public benefits and social safety nets.

Moreover, any regulations and controls on sex workers and their activities need to be nondiscriminatory and otherwise comply with international human rights law. For example, restrictions that would prevent those engaged in sex work from organizing collectively, or working in a safe environment, are not legitimate restrictions.

Why does Human Rights Watch support full decriminalization rather than the “Nordic model?”

The “Nordic model,” first introduced in Sweden, makes buying sex illegal, but does not prosecute the seller, the sex worker. Proponents of the Nordic model see “prostitution” as inherently harmful and coerced; they aim to end sex work by killing the demand for transactional sex. Disagreement between organizations seeking full decriminalization of sex work and groups supporting the Nordic model has been a contentious issue within the women’s rights community in many countries and globally.

Human Rights Watch supports full decriminalization rather than the Nordic model because research shows that full decriminalization is a more effective approach to protecting sex workers’ rights. Sex workers themselves also usually want full decriminalization.

The Nordic model appeals to some politicians as a compromise that allows them to condemn buyers of sex but not people they see as having been forced to sell sex. But the Nordic model actually has a devastating impact on people who sell sex to earn a living. Because its goal is to end sex work, it makes it harder for sex workers to find safe places to work, unionize, work together and support and protect one another, advocate for their rights, or even open a bank account for their business. It stigmatizes and marginalizes sex workers and leaves them vulnerable to violence and abuse by police as their work and their clients are still criminalized.

Isn’t sex work a form of sexual violence?

No. When an adult makes a decision of her, his, or their own free will to exchange sex for money, that is not sexual violence.

When a sex worker is the victim of a crime, including sexual violence, the police should promptly investigate and refer suspects for prosecution. When a person exchanges sex for money as a result of coercion – for example by a pimp – or experiences violence from a pimp or a customer, or is a victim of trafficking, these are serious crimes. The police should promptly investigate and refer the case for prosecution.

Sex workers are often exposed to high levels of violence and other abuse or harm, but this is usually because they are working in a criminalized environment. Research by Human Rights Watch and others indicates that decriminalization can help reduce crime, including sexual violence, against sex workers.

Aside from decriminalizing sex work, what other policies does Human Rights Watch support with regard to sex workers’ rights?

People engaged in voluntary sex work may come from backgrounds of poverty or marginalization and face discrimination and inequality, including in their access to the job market. With this in mind, Human Rights Watch supports measures to improve the human rights situation for sex workers, including research and access to education, financial support, job training and placement, social services, and information. Human Rights Watch also encourages efforts to address discrimination based on gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, race, ethnicity, or immigration status affecting sex workers.

Human Rights Watch research documenting abuse against sex workers:

- Why We’ve Filed a Lawsuit Against a US Federal Law Targeting Sex Workers , June 2018

- Greece: Police Abusing Marginalized People: Target the Homeless, Drug Users, Sex Workers in Athens , March 2015

- “I’m Scared to Be a Woman”: Human Rights Abuses Against Transgender People in Malaysia , September 2014

- In Harm’s Way: State Response to Sex Workers, Drug Users and HIV in New Orleans, December 2013

- “Swept Away”: Abuses Against Sex Workers in China , May 2013

- “Treat Us Like Human Beings”: Discrimination against Sex Workers, Sexual and Gender Minorities, and People Who Use Drugs in Tanzania , June 2013

- Off the Streets: Arbitrary Detention and Other Abuses against Sex Workers in Cambodia, July 2010

- Sex Workers at Risk: Condoms as Evidence of Prostitution in Four US Cities , July 2012

Your tax deductible gift can help stop human rights violations and save lives around the world.

- Women's Rights

More Reading

South africa: decriminalise sex work.

Why We’ve Filed a Lawsuit Against a US Federal Law Targeting Sex Workers

“This Is Why We Became Activists”

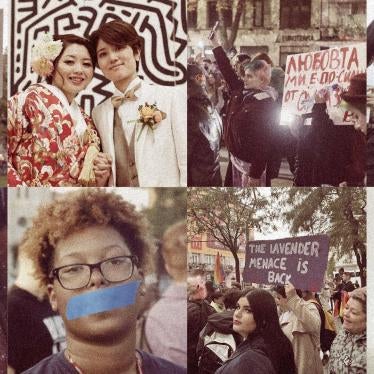

Violence Against Lesbian, Bisexual, and Queer Women and Non-Binary People

Future Choices

Charting an Equitable Exit from the Covid-19 Pandemic

Most Viewed

Sudan: ethnic cleansing in west darfur.

South Korea: Extend Health Benefits to Same-Sex Partners

U.S.: 'Hague Invasion Act' Becomes Law

A dirty investment.

Gaza: Israelis Attacking Known Aid Worker Locations

Protecting Rights, Saving Lives

Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people in close to 100 countries worldwide, spotlighting abuses and bringing perpetrators to justice

Get updates on human rights issues from around the globe. Join our movement today.

Every weekday, get the world’s top human rights news, explored and explained by Andrew Stroehlein.

Cookies in use

Beyond the stereotypes: a deep dive into sex work.

Sex work. We all see it across tv, in the news, or maybe even on platforms like OnlyFans, but the diverse experiences of those involved in this profession are deeper and more comprehensive than you may know. Dispelling misconceptions, challenging stigmas, and promoting a perspective that recognizes the agency, rights, and well-being of sex workers is how we can ensure that we have a more holistic approach to ending health care disparities.

Navigate The Page:

Sex Work as Survival - Criminalization - Ending HIV - Support

Spectrum of Sex Work

Sex work is the exchange of sexual services for money or something of value (erotic dancing, adult film actors, BDSM workers, etc.). Individuals engage in sex work for a variety of reasons, which could include choice, circumstance, and coercion.

Sex Work As Survival

Sex work is often part of a survival economy. When society makes access to health care, education, food, water, and shelter extremely inaccessible or unaffordable to many people and families across the country, biased political leaders strategically use those barriers and the gaps they create to target marginalized communities or any group they deem as an “other.”

The criminalization of sex work is rooted in stigmatization and a sex shaming culture. Society over-polices and shames sex work under the guise of ‘ keeping the community safe, ’ but all it ultimately does is punish and dehumanize sex workers while perpetuating the existing societal structures that may have coerced or placed people in a circumstance where sex work becomes survival. This practice threatens human rights for vulnerable communities, deprives them of access to essential social, economic, and health systems, and makes it that much harder to end epidemics such as HIV, mpox, and health care disparities.

In addition to the desperation someone may feel in this situation, imagine the added burden for those who are medically dependent, such as individuals who need gender-affirming services and/or whose health and life depends on their adherence to sexual health services such as HIV treatment .

The “Legal” Targeting of Poverty

Social Determinants of Health are disproportionately impacted by current policies and legislation against sex workers. The policies affect historically marginalized identities such as LGBTQ+ communities, and have especially targeted transgender folks. These policies negate the survival economy sex workers are forced into, demonize and dehumanize them, and paint them not as people but “threats.”

Systemic Barriers that Sex Workers Face:

Criminalization:.

Legislation that encourages the policing and criminalization of sex work, such as criminalizing, loitering gives law enforcement a tool to harass and discriminate against communities.

Surveillance:

Institutions such as police departments, state legislatures, and corporate businesses, prioritize funding towards surveillance technologies that are designed specifically to increase the targeting of sex workers. This redirects public blame onto sex workers and diverts attention from the actual systemic problems that drove them there.

Incarceration:

Incarcerated, sex workers have a hard time gaining job and educational opportunities. It can also further debt, or even cause loss of life, especially during imprisonment. Ultimately, incarceration creates a cycle where sex workers lose too much access and opportunity to move from sex work to other careers and educational paths.

Lack of Safety:

Sex workers often operate in unsafe locations to avoid surveillance, debt, incarceration, and other forms of punishment -- increasing the risk of physical harm, hate crimes or even fatal assault.

Public and private entities are legally allowed to deny human rights and health care to people who are incarcerated, which negatively impacts their quality of life.

Difficulty Seeking Justice:

Fearing punishment and mockery, sex workers don’t always feel comfortable coming forward with their stories of abuse or seeking legal justice when attacked.

Shame & Stigma Prevents Ending the HIV Epidemic

Institutional punishment such as incarceration, and discriminatory policies in health care interfere with attempts to solve current health issues—such as the global HIV epidemic and the transmission of STD’s and STI’s across the country—and cause economic hardship and worsened access to health care. This hurts the ability for non-profits and health focused organizations to provide care towards ending the epidemic and dealing with public health crises, which worsens health outcomes for society as a whole.

The simple fact is that we can’t end HIV without providing support to both sex workers and their sexual partners, and the key to that is removing stigma and providing social aid. The prevalence of HIV in sex workers is 12x that of the average population . Our international goal of ending the HIV epidemic involves taking care of sex workers as an important factor in finding success. As Fannie Lou Hamer once said, “nobody’s free until everybody’s free.”

How You Can Support

See sex workers as humans.

Focusing on force, punishment, sex shaming, and excommunication from society instead of on solutions only contributes to the system of poverty and the dehumanization and fatal dangers that many sex workers face—especially, transgender women of color.

Support Decriminalization

HRC supports decriminalization legislation and the push for decriminalization of sex work across the United States. Decriminalizing sex work would allow those engaged to live without stigma, social exclusion, and fear of violence or fear of seeking justice. Removing surveillance, prosecution, and stigma from sex work would be recognizing sex work as work , and would enable society to protect sex workers and help them navigate workplace safety and health concerns. It would also open their access to additional opportunities to improve their well-being

Find Advocacy Opportunities

Below are a list of organizations that help provide life-saving resources and support to sex workers. Our partners may also be a good resource to find local advocacy opportunities in your area.

Urban Justice Center: https://swp.urbanjustice.org/

St. James Infirmary: https://www.stjamesinfirmary.org/

Asian and Migrant Sex Workers and Allies: https://www.redcanarysong.net/

Red Umbrella Fund: Sex Workers Rights: https://www.redumbrellafund.org/

Sex Workers Outreach Project USA: https://swopusa.org/

HIPS: https://www.hips.org/

Liberating LGBTQ+ People: https://www.blackandpink.org/

Read More About STAR: http://nswp.org/timeline/street-transvestite-action-revolutionaries-found-star-house

Decriminalize Sex Work (2020): DECRIMINALIZING SURVIVAL: POLICY PLATFORM AND POLLING ON THE DECRIMINALIZATION OF SEX WORK

Decriminalize Sex Work (DSW), National Nonprofit: https://decriminalizesex.work/why-decriminalization/

The Stroll (2023) - Documentary on HBO detailing the experiences of trans women who were sex workers in Lower Manhattan in the 90s

Learn & Live into Sexual Health:

Learning about sex practices is empowering and important for everyone. Take control of your sexual health by checking out our My Body, My Health initiative to find sexual health resources, services on prevention, testing, treatment options, U=U, sex positivity, local providers, and more!

Embrace Your Sexuality

We're building a generation free of HIV and stigma. Embrace sex positivity with My Body, My Health campaign. Are you in?

Related Resources

HIV & Health Equity, Health & Aging

Is PrEP Right For Me?

HIV & Health Equity, Health & Aging, Sexual Health, Recursos en Español, Reports

Healthy Sex Guide (La Guía de Sexo Más Seguro)

Workplace, Allies

Human Rights Campaign Foundation Overview

Love conquers hate., wear your pride this year..

100% of every HRC merchandise purchase fuels the fight for equality.

Choose a Location

- Connecticut

- District of Columbia

- Massachusetts

- Mississippi

- New Hampshire

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Pennsylvania

- Puerto Rico

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- West Virginia

Leaving Site

You are leaving hrc.org.

By clicking "GO" below, you will be directed to a website operated by the Human Rights Campaign Foundation, an independent 501(c)(3) entity.

Sex Workers And Sex Work Essay

The term sex work dates to 1973, when the organization Call Off Your Old Tired Ethics proposed replacing the term prostitute with the term sex worker to separate sex workers from dirt and disease and instead legitimize them as a social category engaged in an income-generating occupation (Uretsky, 2014). Sex work is commonly thought to be associated with dirt and disease. The public health field has used sex work as a “behavioral category” which is useful for targeting a population determined to be at high risk for HIV infection. This approach however is discriminatory against sex work and has torn sex workers away from the idea that they are actual workers with an actual occupation, to disease ridden and risk factors. Sex can be considered both work for men and women. Because sex work is often associated with disease, as are sex workers, they are branded, and have a reputation related to immoral behavior which leads to stigma and discrimination. Popular accounts of sex work tend to present prostitution as a product of the economy or as sex workers having psychological problems, lending to the narrative of sex workers as passive and as victims exploited and coerced into sex work. This paper takes a look at the lives of sex workers, male , female, and also transgender people, and the similarities between them, but also some differences as these cannot be completely ignored or overlooked. Chinese discourse on sex work, which is more developed than most discussions on sex work,

Essay on Sex Trafficking

- 6 Works Cited

Sex trafficking is essentially systemic rape for profit. Force, fraud and coercion are used to control the victim’s behavior which may secure the appearance of consent to please the buyer (or john). Behind every transaction is violence or the threat of violence (Axtell par. 4). Just a decade ago, only a third of the countries studied by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime had legislation against human trafficking. (Darker Side, par.1) Women, children, and even men are taken from their homes, and off of the streets and are brought into a life that is almost impossible to get out of. This life is not one of choice, it is in most times by force. UNODC estimates that the total international human trafficking is a

Persuasive Essay On Prostitution

Prostitution is one of the oldest and most controversial professions on earth. According to records, prostitution was a normal practice of the earliest known civilizations. Ancient Greeks and Roma governments went as far as sponsoring brothels to ensure their citizens could afford a prostitute. The emergence of religions like Christianity and Islam transformed the moral views on prostitution. Following a tremendous pressure from the religious authorities, many European countries started to ban the practice on the bases of being immoral and harmful to society. The king of Spain made prostitution punishable law. Those caught could face a harsh punishment or they could be exiled. Pope Sixths of Rome went as far as making prostitution punishable by death .Despite the laws drafted by the authorities, people continued to provide and use sexual services. In this modern era, we are still debating the ethics of prostitution. Most people claim that prostitution is morally degrading and harmful to the wellbeing of society. While others claim that legalizing prostitution can help create tax revenues, undermine organized crime and reduce the spread of disease. Using utilitarianism, virtue ethics and Kant deontology I will prove that prostitution is immoral and it should be banned.

Sex Trafficking And Human Trafficking Essay

Human trafficking brings in billions of dollars into the U.S and all around the world. “The prime motive for such outrageous abuse is simple: money. In this $12 billion global business just one woman trafficked into the industrialized world can net her captors an average $67,000 a year” (Baird 2007). The laws around human trafficking are not strict and vary depending on what country it is happening in. Human trafficking is not something that is strictly foreign, it is happening right in front of our faces, in our neighborhoods, and all around us.

Moving Prostitution Through The United States

Abstract: This paper explores the world’s oldest and most controversial occupation and puts forth a foundational plan for legalizing and regulating sex work in a safe way that satisfies both radical and liberal feminists ideals. To understand how prostitution has evolved to where it’s at today, this proposal travels through the history of prostitution in the United States (heavily focusing on the twentieth century.) Prostitutes were initially accepted and openly sought after. A shift in societal norms and values placed sex work in a heavy degradation. The regulation of prostitution in Nevada began in 1970 and resulted in the first licensed brothel in 1971. Fast forward nearly fifty years and prostitution is outlawed in 49 out of 50 states. Vast amounts of money are being spent annually in failed attempts to stop prostitution all together. Radical feminists are those who would identify as conservative. They are against prostitution on the belief that it victimizes and degrades women in poverty. Liberal feminists strongly agree that the government has no place in a women’s body and that the right to perform sex work is human right. This paper analyzes these different perspectives and incorporates a model that will resemble the current working regulation in Nevada. Stricter stipulations such as health requirements and the legal age should help influence radical feminist to expand their perspective and acceptance.

Research Paper On Human Sex Trafficking

Rijken, C. (2009). A human rights based approach to trafficking in human beings. Security &

Sex Workers in Canada Essay

- 8 Works Cited

Sometimes, the term “sex work” is used, as well as “prostitution”. But whichever term we choose to say, it does not eliminate the stigma attached to it. Cases such as the Bedford V. Canada Case (144) indulges into the conspiracy of sex work and challenges certain sections of the Criminal Code that make business in relation to prostitution illegal. Ideally, a sex worker has a career just as a teacher or lawyer. For this reason, their human rights and dignity should be protected by the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms as are other professions. However, the Charter of Rights and Freedoms as well as the Criminal Code do not seek to protect sex workers, yet, they seek to do otherwise using certain sections of the Criminal Code

Women Of Color Research Paper

Society pushing these women into this sex industry is severally impacting how these women daily lives are being lead. For example, the article written by Carmen Logie states "In multivariable analyses, paid sex and transactional sex were both associated with: intrapersonal (depression), interpersonal (lower social support, forced sex, childhood sexual abuse, intimate partner violence, multiple partners/polyamory), and structural (transgender stigma, unemployment) factors. Participants reporting transactional sex also reported increased odds of incarceration perceived to be due to transgender identity, forced sex, homelessness, and lower resilience, in comparison with participants reporting no sex work involvement." This reveals to the readers that sex work extremely affects these women's lives. This sex industry has a major negative impact on these women's lives. The quote reveals that this industry that a large majority of transgender women are exposed to can lead to things like jail, homelessness, and abuse. Yet, no one acknowledges that societies stigma against these women is what is pushing these women into this extremely dangerous industry. Participating in sex work can even affect these women's health they can acquire HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases. These diseases are extremely detrimental to these women's health and can even lead to their death. Women in sex work more also likely have mental

Prostitution Vs Sex Trafficking Essay

Most people throughout the world would think of slavery as an issue of the past, but sex trafficking is today’s form of “modern day slavery” (Countryman-Roswurm, 2014). Sex trafficking has become the fastest growing and most profitable criminal enterprise in the world due to the fact that people can be sold over and over again. Corrupt governments have tried to cover this issue up and have worked alongside traffickers to help them obtain illegal documents to continue operating (Deshpande et al., 2013). The effects of this crime causes victims of trafficking to have many emotional, physical, and mental traumas (Deshpande et al., 2013).

Sex Trafficking Persuasive Essay

Currently, 501 children mostly African American and Latino are missing out of Washington, D.C. since the beginning of the year. The police have good reason to believe that this is due to sex trafficking. These kids were taken from their lives and are threatened even with the thought of leaving their trafficker. Some children have been able to escape, but this is very risky. A young, 13-year-old girl who has a mental illness was brought into sex trafficking because she believes that her trafficker loved her. She was sold for sex to around 40 men per day. Because of these reasons sex trafficking needs to become a thing of the past. Sex trafficking in the United States can be reduced and possibly eliminated through education, government intervention,

Prostitution In Canada Essay

For the purpose of this study, male prostitutes and sexual acts such as pornography, stripping and erotic massages are excluded from the definition of prostitution. The terms ‘sex worker’ and ‘prostitute’ will be used interchangeably throughout the paper. The term ‘sex work’ was coined to circumvent the stigma that accompanies prostitution and to acknowledge that it generates income, like any other profession in our society (Sondhi, 2011).

Not A Choice By Janice G. Raymond

Often, when people think of sex work and sex workers their minds immediately go to human trafficking. Yet, I believe it is essential that one marks the difference between the two, because as social workers we will have clients who come to us who have chosen to be sex workers. As social workers we recognize that every individual has the right to self-determination and we must know how to best serve them. In Janice G. Raymond’s book Not a Choice, Not a Job, she explores the world of sex work and though her views conflict with social work values she presents great information into the world of sex work. I will be presenting the ideas from her book and also be offering other views that are important when working with clients.

The Stigma Of Prostitution, And Sexual Slavery

The first part of Nussbaum’s paper challenges to examine the stigmatization of prostitution by comparing it to six other kinds of jobs/professions in which the individual uses her body in ways that majority of us do not necessary find morally objectionable but are not far off from the ways prostitutes use their bodies in the trade. These range from the domestic servant who “must do what the client wants, or fail at the job” (pg. 375), the nightclub singer who pleasures her customers by her voice to the colonoscopy artist who allows herself to be probed without anesthesia in a “consensual invasion” (pg. 378) of her bodily space for the purpose of medical education. The further we go down the list of the six jobs/professions, we see a closer

Prostitution Persuasive Essay Outline

they were being forced, have a smoother system going, and making sure nothing was to go wrong.

The Issue Of Sex Work Essay

Sexual favours in return for money, just the thought of this has people cringing, although laws have deemed to move forward with the idea of prostitution it seems although socially there has not been much progress. The idea of prostitution still scares, or one could even go as far to say it disgusts people. The lack of knowledge and awareness of the details of sex work create this ongoing hate towards sex work, which continues to stigmatize sex workers. Regardless of changing laws, regardless of changing policies, why is it that sex workers are still afraid to proudly announce that their job is in fact the job of a sex worker? Unfortunately, it seems as though the idea of sex work that seems to be such a terrible one is not what bothers sex workers the most, it is the social misconception of what sex work is like that leads these individuals to feel highly stigmatized (Van der Meulen and Redwood, 2013). The primary harm for of prostitution seems to be the stigma against prostitution, women involved in prostitution are considered socially invisible as full human beings (Farley, 2004). Why is it that our changing and progressing laws are still unable to remove this stigma from the lives of sex workers? This paper will argue that prostitution laws continue to produce stigma around sex work. It will argue this through revisiting the historical laws, examining present laws and ongoing laws at this time.

Slavery and Sex Trafficking Essay

When we hear the word slavery our mind paints a picture of colonial America down in the South with big plantation houses harvesting wheat, with workers being unpaid and unfairly treated. At this time in our county we were struggling with the idea of equality for all. America has come a long way from those days but not with out a fight. Abraham Lincoln, the Civil Rights moment and free and public education has been addressed. Today, we face a new conflicts and a different type of slavery. Slavery and sex trafficking is occurring not just abroad but at home as well. In 2004, “800,000 to 9000,000 men women and children are trafficked across international borders every year, including 18,000 to 20,000 in the US. Worldwide slavery is in the

Related Topics

- Prostitution

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Should Sex Work Be Decriminalized? Some Activists Say It's Time

Jasmine Garsd

LGBTQ, immigrant rights and criminal justice reform groups, launched a coalition, Decrim NY, in February to decriminalize the sex trade in New York. Erik McGregor/Getty Images hide caption

LGBTQ, immigrant rights and criminal justice reform groups, launched a coalition, Decrim NY, in February to decriminalize the sex trade in New York.

Sex work is illegal in much of the United States, but the debate over whether it should be decriminalized is heating up.

Former California Attorney General and Democratic presidential candidate Kamala Harris recently came out in favor of decriminalizing it , as long as it's between two consenting adults.

The debate is hardly new — and it's fraught with emotions. Opponents of decriminalization say it's an exploitative industry that preys on the weak. But many activists and academics say decriminalization would help protect sex workers, and would even be a public health benefit.

The Two-Way

Queen honors activist who fought to decriminalize prostitution.

RJ Thompson wants to push back against the idea that sex work is inherently victimizing. He says for him it was liberating: Thompson had recently graduated from law school and started working at a nonprofit when the recession hit. In 2008, he got laid off with no warning and no severance, and he had massive student loan debt.

Thompson became an escort. "I made exponentially more money than I ever could have in my legal profession," he says.

He says the possibility of arrest was often on his mind. And he says for many sex workers, it's a constant fear. "Many street-based workers are migrants or transgender people who have limited options in the formal economies," he says. "And so they do sex work for survival. And it puts them in a very vulnerable position — the fact that it's criminalized."

Thompson is now a human rights lawyer and the managing director of the Sex Workers Project at the Urban Justice Center. It's among several organizations that are advocating bills to decriminalize sex work in New York City and New York state. They already have the support of various state lawmakers .

TED Radio Hour

Juno mac: how does stigma compromise the safety of sex workers.

Due to its clandestine nature in America, it's extremely hard to find reliable numbers about the sex trade. But one thing is for sure: It's a multi-billion-dollar industry. In 2007, a government-sponsored report looked at several major U.S. cities and found that sex work brings in around $290 million a year in Atlanta alone.

Economist Allison Schrager says the Internet has increased demand and supply. "Women who pre-Internet (or men) who wouldn't walk the streets or sign with a madam or an agency now can sell sex work, sometimes even on the side to supplement other sources of income," she says.

So what happens when you take this massive underground economy and decriminalize it? Nevada might offer a clue. Brothels are legal there, in certain counties.

In Shrager's book, An Economist Walks Into A Brothel , she investigated the financial workings of the Nevada brothel industry. She found that on average it's 300 percent more expensive to hire a sex worker in a Nevada brothel than in an illegal setting. Shrager thinks it's because workers and customers prefer to pay for the safety and health checks of a brothel.

"Sex work is risky for everyone," she says. "You take on a lot of risk as a customer too. And when you're working in a brothel you are assured complete anonymity. They've been fully screened for diseases."

Goats and Soda

Legalizing prostitution would protect sex workers from hiv.

But many activists and academics say decriminalization would help protect sex workers and could also have public health benefits.

Take the case of Rhode Island . A loophole made sex work, practiced behind closed doors, legal there between 2003 and 2009.

Baylor University economist Scott Cunningham and his colleagues found that during those years the sex trade grew. But Cunningham points to some other important findings : During that time period the number of rapes reported to police in the state declined by over a third. And gonorrhea among all women declined by 39 percent. Of course, changes in prostitution laws might not be the only cause, but Cunningham says, "the trade-off is if you make it safer to some degree, you grow the industry."

Rhode Island made sex work illegal again in 2009, in part under pressure from some anti-trafficking advocates. That's the thing: The debate about sex work always gets linked to trafficking — people who get forced into it against their will.

Economist Axel Dreher from the University of Heidelberg in Germany teamed up with the London School of Economics to analyze the link between trafficking and prostitution laws in 150 countries. "If prostitution is legal, there is more human trafficking simply because the market is larger," he says.

It's a controversial study: Even Dreher admits that reliable data on sex trafficking is really hard to find.

Human rights organizations including Amnesty International support decriminalization. Victims of trafficking might be able to ask for help more easily if they aren't afraid of having committed a crime, the groups say.

Cecilia Gentili is the director of policy at GMHC, an HIV/AIDS prevention, care and advocacy nonprofit in New York. Erik McGregor/Getty Images hide caption

Cecilia Gentili is the director of policy at GMHC, an HIV/AIDS prevention, care and advocacy nonprofit in New York.

Former sex worker Cecilia Gentili says she might have been able to break free much sooner had it not been for fear of legal consequences. She left her native Argentina because she was being brutally harassed by police in her small town. She thought she'd be better off when she moved to New York, but as a transgender, undocumented immigrant, she says she had few options.

"Let's be realistic," Gentili says, "for people like me, sex work is not 'one' job option. It's the only option."

Gentili says that when police busted the drug house in Brooklyn where she was being held, she debated whether to ask for help. She figured she was in a very vulnerable position, as a trans, undocumented person. She stayed quiet.

These days Gentili is the director of policy at GMHC , an HIV/AIDS prevention, care and advocacy nonprofit in New York. She's advocating for New York City and state to decriminalize sex work.

Rachel Lloyd is the founder of Girls Educational and Mentoring Services, a nonprofit for sexually exploited women in New York. Jasmine Garsd/NPR hide caption

Rachel Lloyd is the founder of Girls Educational and Mentoring Services, a nonprofit for sexually exploited women in New York.

But many believe the sex industry is just fundamentally vicious and decriminalizing it will make it worse. Rachel Lloyd is the founder of Girls Educational and Mentoring Services , a nonprofit for sexually exploited women in New York. She says there's nothing that will equalize the power unbalances in the sex industry.

"The commercial sex industry is inherently [exploitative]," she says. "The folks who end up in the commercial sex industry are the folks who are the most vulnerable and the most desperate."

When she was a teenager, Lloyd sold sex in Germany, where it's legal. But she says that didn't make it any less brutal for her.

The Surprising Wishes Of India's Sex Workers

"Those power dynamics of exploitation were still there," she says. "When ... legal johns came in, they were the ones with the money."

Lloyd says she doesn't want sex workers to be persecuted or punished. But she doesn't think men should be allowed to buy sex legally. She says that would be condoning the same industry that brutalized her and the women she works with today.

But decriminalization activists say that sex work has and always will exist. And they say bringing it out of the shadows can only help.

Read more stories from NPR Business.

- prostitution

- sex trafficking

Edited by Natalie West, with Tina Horn Essays on Sex Work and Survival

Paperback Edition ISBN: 9781558612853 Publication date: 02-09-2021

Foreword by Selena the Stripper

This collection of narrative essays by sex workers presents a crystal-clear rejoinder: there’s never been a better time to fight for justice. Responding to the resurgence of the #MeToo movement in 2017, sex workers from across the industry—hookers and prostitutes, strippers and dancers, porn stars, cam models, Dommes and subs alike—complicate narratives of sexual harassment and violence, and expand conversations often limited to normative workplaces.

Writing across topics such as homelessness, motherhood, and toxic masculinity, We Too: Essays on Sex Work and Survival gives voice to the fight for agency and accountability across sex industries. With contributions by leading voices in the movement such as Melissa Gira Grant, Ceyenne Doroshow, Audacia Ray, femi babylon, April Flores, and Yin Q, this anthology explores sex work as work, and sex workers as laboring subjects in need of respect—not rescue.

A portion of this book's net proceeds will be donated to SWOP Behind Bars (SBB).

“While mainstream media does not allow the space for a complex and nuanced portrait of sex work, because such coverage is often weaponized, this book is salvation. The writing is unfailingly keen, each piece individually capable of inducing radical empathy. This book and its fierce creators are ready to change the world.” — Booklist , starred review

“Offers a stop gap, a bridge, or a passage for sex workers enduring violence by uplifting both pain and survival with dignity.” —Autostraddle

“Funny and fresh and very not the same story you might have heard about sex work before—the pieces feel complex and exciting.” —Xtra Magazine

“As the essays in this powerful collection demonstrate, it has always been sex workers who have kept each other safe: from predatory clients, from pimps, and from the police. These essays reveal workers who are not helpless, but oppressed, and are increasingly organizing for their rights.” —Lux

“As infuriating as it is vulnerable, the book serves as a testament that sex workers deserve a central place in both the labor and feminist movements.” — In These Times

“ We Too: Essays on Sex Work and Survival embodies the rallying cry: ‘Nothing about us without us.’ Featuring incisive essays by sex workers of all backgrounds, this vital anthology centers diverse narratives about sex work, labor rights, sexual assault, trauma, and healing that too often go unheard. Raw, gut-wrenching, and transformative, We Too is a powerful addition to the canon of books by sex workers and for sex workers and their allies.” —Kristen J. Sollée, author of Witches, Sluts, Feminists

“ We Too offers a sharp indictment of this world and a warm invitation to build another one. Against a #MeToo movement that represents some at a high cost to others, We Too places sex workers at the front lines of an anti-violence movement for the rest of us. We Too ’s vision knows the state is no ally, that freedom won’t come without solidarity, and that real cultures of consent will come from the ground up.” —Heather Berg, author of Porn Work: Sex, Labor, and Late Capitalism

“A necessary, wide-ranging, preconception-smashing collection of essays by writers who speak from experience within the sex industry. At turns, these essays are devastating, astute, funny, and heart opening. Taken together, they are a welcome antidote to the reductive narratives about sex worker experiences that we hear too often. We Too is an anthology that honors the humanity, diversity, and depth of insight within the field. Reading it made me want to stand up and cheer.” —Melissa Febos, author of Whip Smart and Abandon Me

“This incredible anthology has pulled together personal stories of sex work that speak to a reality that only so many of us know. There are even fewer of us who have the capacity and desire to relive some of these tacit moments that become predictable fodder for outsiders to bemuse themselves with temporarily. But beyond the buzzworthy story of selling sex is the truth and lived experience, and the understanding of value, self-worth, self-pity and self-empowerment. We Too ’s firsthand accounts will give perspective and nuance to the ‘sex work is work’ conversation in this new era of informed consent.” —Lotus Lain, adult performer and sex worker rights advocate

“ We Too is a powerful, engrossing collection of essays, each lending a unique perspective from a courageous and resilient voice. Together, these essays constitute a critical resource for understanding the complex and diverse world of sex worker experience.” —Isa Mazzei, screenwriter, CAM

“In We Too , the voices of those within the sex worker community come together on topics that don’t get much exposure outside our own private gatherings. This collection is incisive, generous, vulnerable, and insightful with a fair dash of humor and verve. It should come as no surprise that sex workers thinking and writing on harassment and interpersonal violence are much more multidimensional, tender, and thoughtful than most mainstream intellectuals on the topic. It’s so important that these stories are heard as told by us.” —Rachel Rabbit White, author of Porn Carnival

“The Me Too movement, started by Tarana Burke, was formed to fight for the working class, often left vulnerable to sexual violence with little to no justice. This anthology, We Too: Essays on Sex Work and Survival , examines that sexual violence and labor with a lens that looks specifically at how sex workers experience and witness it. Documenting personal accounts of sexual violence in the workplace, We Too can be a hard pill to swallow but presents a path toward healing from and combating rape culture from people who have survived on the front lines. This anthology brilliantly showcases the billowing voice of the sex worker community and how it supports and should be supported by feminist movements like Me Too.” —Courtney Trouble, founder of NoFauxxx.com

“ We Too is a crucial, brutally necessary book that works to create needed intersectionality within the Me Too movement and feminism generally. These stunning outsider voices are thick with inside information, personal and political, and most importantly they’re great, gripping reads. I’m very grateful for this collection.” —Michelle Tea, author of Against Memoir: Complaints, Confessions & Criticisms

Natalie West is a Los Angeles based writer and educator.

Tina Horn hosts and produces the long-running kink podcast Why Are People Into That?!

You Might Also Like

Radical Reproductive Justice

Walking the Precipice

We Were There

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

26 Sex Work, Gender, and Criminal Justice

Ronald Weitzer is a Professor of Sociology at George Washington University.

- Published: 01 July 2014

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This essay examines key dimensions of contemporary sex work as they relate to gender and the legal system. Theoretical perspectives and empirical research on street and indoor prostitution, stripping, and pornography are reviewed. In most places, the law and criminal justice system focus on women working in these sectors, with much less official attention to male and transgender sex workers. Scholarly research on male sex work has expanded in the past two decades but remains but a fraction of the academic literature. The essay concludes with a discussion of two recent, divergent trends in state policies: increased criminalization and legalization.

26.1. Introduction

Sex work involves the exchange of sexual services or erotic performances for material compensation and includes pornography, commercial telephone sex, erotic performances (stripping, webcam), and prostitution. Depending on the society in question, these practices may be legal or illegal. Where legal, they are subject to some type of government regulation, such as restrictions on eligibility and location. Unlike predatory crimes with a clear victim, illegal sex work involving adults generally entails exchanges between willing buyers and sellers, which leads some members of the public to view it with a measure of moral ambivalence or tolerance.

This essay focuses on prostitution—and, to a lesser extent, pornography and stripping—with special attention to issues of gender and criminal justice. In addition, it documents some important international trends in state policy. These trends are not uniform, as criminalization has intensified in some societies just as legalization is being embraced by others ( McCarthy et al. 2012 ; Weitzer 2012 ). Importantly, under both trends it is typically women who are the focus of new legislation and enforcement practices. While the new laws are usually gender-neutral, they are drafted with women in mind: law enforcement (under criminalization) and implementation of regulations (under legalization) is usually directed at female rather than male sex workers. Male clients of female sex workers are targeted in some nations but not in others, while male and transgender sex workers are almost entirely neglected in the law-in-action.

This essay begins with a review of major theoretical perspectives on sex work and then addresses gender issues. It argues that gender is all too often taken for granted in this scholarly work in part because of its focus on female sex workers and male customers and the general neglect of male and transgender sex workers and female customers. Additional research on these latter actors will help clarify both the ways in which sex work is gendered and the ways in which it is experienced similarly irrespective of gender. The essay concludes with a discussion of the legal context in the United States as a point of departure for considering broader international trends in legislation regarding sexual commerce. In doing so, the essay examines research bearing on two trends—increased criminalization and legalization.

26.2. Competing Theories

Three main theoretical perspectives have been applied to sex work. The oppression paradigm holds that prostitution reflects and reinforces patriarchal gender relations. Advocates of this paradigm argue that sex work is harmful both instrumentally and symbolically. Instrumentally, exploitation, subjugation, and violence against women are viewed as inherent in sex work ( Jeffreys 1997 ; Farley 2006 ). Symbolically, the very existence of commercial sex is seen as implying that men have a “patriarchal right of access to women’s bodies”: Men can pay for sex or sexual entertainment from women who otherwise would be unavailable to them, thus perpetuating their subordination ( Pateman 1988 , p. 199). Oppression writers typically use dramatic language to highlight the plight of workers (sexual slavery, prostituted women, survivors) and to emphasize the notion that sex workers are victims of male exploiters and misogynists ( Jeffreys 1997 ; Farley 2006 ). Oppression theorists typically describe only the worst examples of sex work and treat them as representative, and they tend to ignore counterevidence to the paradigm’s main tenets ( Weitzer 2010 ). Female sex workers who claim they have agency or view their work positively are discounted by advocates of this paradigm. Male and transgender sex workers are ignored as well.

The empowerment paradigm is radically different. It focuses on the ways in which sexual services qualify as work, involve human agency, and may be empowering for workers ( Delacoste and Alexander 1987 ; Chapkis 1997 ). Advocates argue that there is nothing inherent in sex work that would prevent it from being organized like any other economic transaction (i.e., for the mutual gain of buyers and sellers alike). Apart from its material rewards, some types of sex work provide greater control over working conditions than many traditional jobs, and this work can enhance workers’ sense of self-worth. However, the positive potential of sex work, from the worker’s perspective, is diluted when it is outlawed, marginalized, and heavily stigmatized.

Few empowerment writers argue that sex work is empowering without qualification; rather they argue that it can be validating under the right circumstances. Writers in this camp highlight benefits and success stories, without claiming that these are typical. For instance, one analyst argues that sex work can be liberating for those who are “fleeing from small-town prejudices, dead-end jobs, dangerous streets, and suffocating families” ( Agustín 2007 , p. 45). A few writers go further and make bold claims that romanticize sex work. Chapkis (1997 , p. 30) describes a “sex radical” version of empowerment wherein sex workers and other sexual outlaws “embrace a vision of sex freed of the constraints of love, commitment, and convention” and present “a potent symbolic challenge to confining notions of proper womanhood and conventional sexuality.” Paglia takes issue with the very notion that commercial sex is an arena of male domination over women:

The feminist analysis of prostitution says that men are using money as power over women. I’d say, yes, that’s all that men have . The money is a confession of weakness. They have to buy women’s attention. It’s not a sign of power; it’s a sign of weakness. (Paglia, quoted in Chapkis 1997 , p. 22)