Dissertation Structure & Layout 101: How to structure your dissertation, thesis or research project.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) Reviewed By: David Phair (PhD) | July 2019

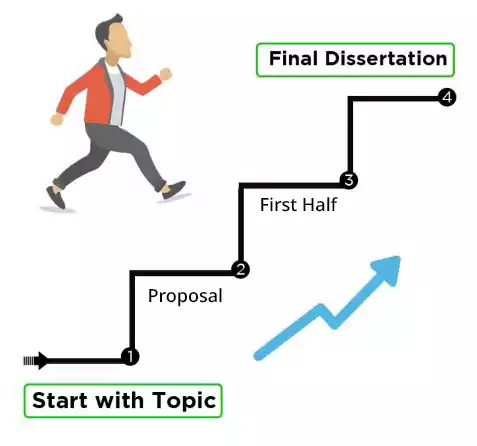

So, you’ve got a decent understanding of what a dissertation is , you’ve chosen your topic and hopefully you’ve received approval for your research proposal . Awesome! Now its time to start the actual dissertation or thesis writing journey.

To craft a high-quality document, the very first thing you need to understand is dissertation structure . In this post, we’ll walk you through the generic dissertation structure and layout, step by step. We’ll start with the big picture, and then zoom into each chapter to briefly discuss the core contents. If you’re just starting out on your research journey, you should start with this post, which covers the big-picture process of how to write a dissertation or thesis .

*The Caveat *

In this post, we’ll be discussing a traditional dissertation/thesis structure and layout, which is generally used for social science research across universities, whether in the US, UK, Europe or Australia. However, some universities may have small variations on this structure (extra chapters, merged chapters, slightly different ordering, etc).

So, always check with your university if they have a prescribed structure or layout that they expect you to work with. If not, it’s safe to assume the structure we’ll discuss here is suitable. And even if they do have a prescribed structure, you’ll still get value from this post as we’ll explain the core contents of each section.

Overview: S tructuring a dissertation or thesis

- Acknowledgements page

- Abstract (or executive summary)

- Table of contents , list of figures and tables

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Literature review

- Chapter 3: Methodology

- Chapter 4: Results

- Chapter 5: Discussion

- Chapter 6: Conclusion

- Reference list

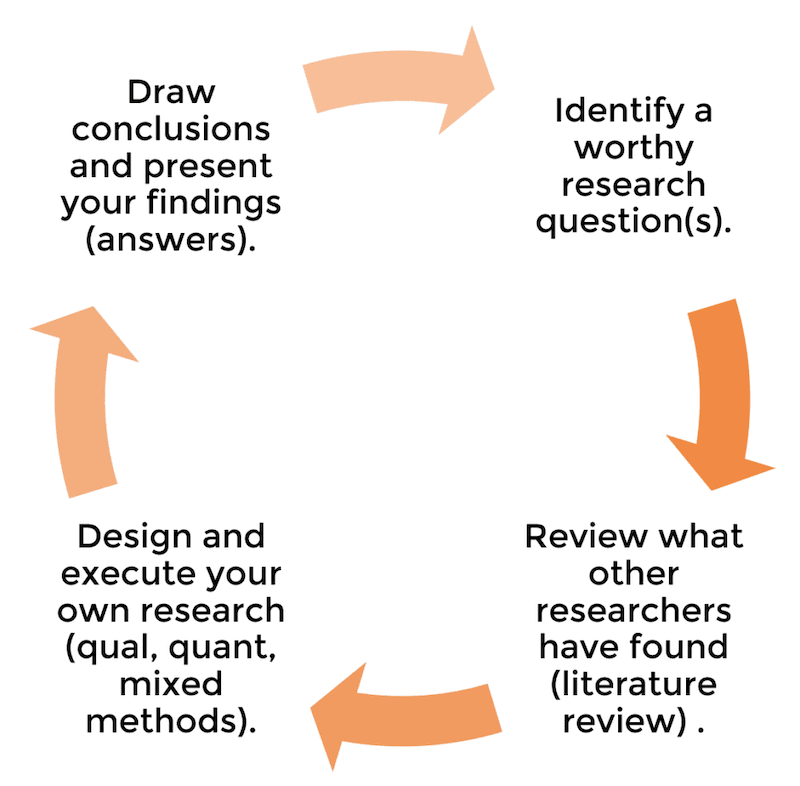

As I mentioned, some universities will have slight variations on this structure. For example, they want an additional “personal reflection chapter”, or they might prefer the results and discussion chapter to be merged into one. Regardless, the overarching flow will always be the same, as this flow reflects the research process , which we discussed here – i.e.:

- The introduction chapter presents the core research question and aims .

- The literature review chapter assesses what the current research says about this question.

- The methodology, results and discussion chapters go about undertaking new research about this question.

- The conclusion chapter (attempts to) answer the core research question .

In other words, the dissertation structure and layout reflect the research process of asking a well-defined question(s), investigating, and then answering the question – see below.

To restate that – the structure and layout of a dissertation reflect the flow of the overall research process . This is essential to understand, as each chapter will make a lot more sense if you “get” this concept. If you’re not familiar with the research process, read this post before going further.

Right. Now that we’ve covered the big picture, let’s dive a little deeper into the details of each section and chapter. Oh and by the way, you can also grab our free dissertation/thesis template here to help speed things up.

The title page of your dissertation is the very first impression the marker will get of your work, so it pays to invest some time thinking about your title. But what makes for a good title? A strong title needs to be 3 things:

- Succinct (not overly lengthy or verbose)

- Specific (not vague or ambiguous)

- Representative of the research you’re undertaking (clearly linked to your research questions)

Typically, a good title includes mention of the following:

- The broader area of the research (i.e. the overarching topic)

- The specific focus of your research (i.e. your specific context)

- Indication of research design (e.g. quantitative , qualitative , or mixed methods ).

For example:

A quantitative investigation [research design] into the antecedents of organisational trust [broader area] in the UK retail forex trading market [specific context/area of focus].

Again, some universities may have specific requirements regarding the format and structure of the title, so it’s worth double-checking expectations with your institution (if there’s no mention in the brief or study material).

Acknowledgements

This page provides you with an opportunity to say thank you to those who helped you along your research journey. Generally, it’s optional (and won’t count towards your marks), but it is academic best practice to include this.

So, who do you say thanks to? Well, there’s no prescribed requirements, but it’s common to mention the following people:

- Your dissertation supervisor or committee.

- Any professors, lecturers or academics that helped you understand the topic or methodologies.

- Any tutors, mentors or advisors.

- Your family and friends, especially spouse (for adult learners studying part-time).

There’s no need for lengthy rambling. Just state who you’re thankful to and for what (e.g. thank you to my supervisor, John Doe, for his endless patience and attentiveness) – be sincere. In terms of length, you should keep this to a page or less.

Abstract or executive summary

The dissertation abstract (or executive summary for some degrees) serves to provide the first-time reader (and marker or moderator) with a big-picture view of your research project. It should give them an understanding of the key insights and findings from the research, without them needing to read the rest of the report – in other words, it should be able to stand alone .

For it to stand alone, your abstract should cover the following key points (at a minimum):

- Your research questions and aims – what key question(s) did your research aim to answer?

- Your methodology – how did you go about investigating the topic and finding answers to your research question(s)?

- Your findings – following your own research, what did do you discover?

- Your conclusions – based on your findings, what conclusions did you draw? What answers did you find to your research question(s)?

So, in much the same way the dissertation structure mimics the research process, your abstract or executive summary should reflect the research process, from the initial stage of asking the original question to the final stage of answering that question.

In practical terms, it’s a good idea to write this section up last , once all your core chapters are complete. Otherwise, you’ll end up writing and rewriting this section multiple times (just wasting time). For a step by step guide on how to write a strong executive summary, check out this post .

Need a helping hand?

Table of contents

This section is straightforward. You’ll typically present your table of contents (TOC) first, followed by the two lists – figures and tables. I recommend that you use Microsoft Word’s automatic table of contents generator to generate your TOC. If you’re not familiar with this functionality, the video below explains it simply:

If you find that your table of contents is overly lengthy, consider removing one level of depth. Oftentimes, this can be done without detracting from the usefulness of the TOC.

Right, now that the “admin” sections are out of the way, its time to move on to your core chapters. These chapters are the heart of your dissertation and are where you’ll earn the marks. The first chapter is the introduction chapter – as you would expect, this is the time to introduce your research…

It’s important to understand that even though you’ve provided an overview of your research in your abstract, your introduction needs to be written as if the reader has not read that (remember, the abstract is essentially a standalone document). So, your introduction chapter needs to start from the very beginning, and should address the following questions:

- What will you be investigating (in plain-language, big picture-level)?

- Why is that worth investigating? How is it important to academia or business? How is it sufficiently original?

- What are your research aims and research question(s)? Note that the research questions can sometimes be presented at the end of the literature review (next chapter).

- What is the scope of your study? In other words, what will and won’t you cover ?

- How will you approach your research? In other words, what methodology will you adopt?

- How will you structure your dissertation? What are the core chapters and what will you do in each of them?

These are just the bare basic requirements for your intro chapter. Some universities will want additional bells and whistles in the intro chapter, so be sure to carefully read your brief or consult your research supervisor.

If done right, your introduction chapter will set a clear direction for the rest of your dissertation. Specifically, it will make it clear to the reader (and marker) exactly what you’ll be investigating, why that’s important, and how you’ll be going about the investigation. Conversely, if your introduction chapter leaves a first-time reader wondering what exactly you’ll be researching, you’ve still got some work to do.

Now that you’ve set a clear direction with your introduction chapter, the next step is the literature review . In this section, you will analyse the existing research (typically academic journal articles and high-quality industry publications), with a view to understanding the following questions:

- What does the literature currently say about the topic you’re investigating?

- Is the literature lacking or well established? Is it divided or in disagreement?

- How does your research fit into the bigger picture?

- How does your research contribute something original?

- How does the methodology of previous studies help you develop your own?

Depending on the nature of your study, you may also present a conceptual framework towards the end of your literature review, which you will then test in your actual research.

Again, some universities will want you to focus on some of these areas more than others, some will have additional or fewer requirements, and so on. Therefore, as always, its important to review your brief and/or discuss with your supervisor, so that you know exactly what’s expected of your literature review chapter.

Now that you’ve investigated the current state of knowledge in your literature review chapter and are familiar with the existing key theories, models and frameworks, its time to design your own research. Enter the methodology chapter – the most “science-ey” of the chapters…

In this chapter, you need to address two critical questions:

- Exactly HOW will you carry out your research (i.e. what is your intended research design)?

- Exactly WHY have you chosen to do things this way (i.e. how do you justify your design)?

Remember, the dissertation part of your degree is first and foremost about developing and demonstrating research skills . Therefore, the markers want to see that you know which methods to use, can clearly articulate why you’ve chosen then, and know how to deploy them effectively.

Importantly, this chapter requires detail – don’t hold back on the specifics. State exactly what you’ll be doing, with who, when, for how long, etc. Moreover, for every design choice you make, make sure you justify it.

In practice, you will likely end up coming back to this chapter once you’ve undertaken all your data collection and analysis, and revise it based on changes you made during the analysis phase. This is perfectly fine. Its natural for you to add an additional analysis technique, scrap an old one, etc based on where your data lead you. Of course, I’m talking about small changes here – not a fundamental switch from qualitative to quantitative, which will likely send your supervisor in a spin!

You’ve now collected your data and undertaken your analysis, whether qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods. In this chapter, you’ll present the raw results of your analysis . For example, in the case of a quant study, you’ll present the demographic data, descriptive statistics, inferential statistics , etc.

Typically, Chapter 4 is simply a presentation and description of the data, not a discussion of the meaning of the data. In other words, it’s descriptive, rather than analytical – the meaning is discussed in Chapter 5. However, some universities will want you to combine chapters 4 and 5, so that you both present and interpret the meaning of the data at the same time. Check with your institution what their preference is.

Now that you’ve presented the data analysis results, its time to interpret and analyse them. In other words, its time to discuss what they mean, especially in relation to your research question(s).

What you discuss here will depend largely on your chosen methodology. For example, if you’ve gone the quantitative route, you might discuss the relationships between variables . If you’ve gone the qualitative route, you might discuss key themes and the meanings thereof. It all depends on what your research design choices were.

Most importantly, you need to discuss your results in relation to your research questions and aims, as well as the existing literature. What do the results tell you about your research questions? Are they aligned with the existing research or at odds? If so, why might this be? Dig deep into your findings and explain what the findings suggest, in plain English.

The final chapter – you’ve made it! Now that you’ve discussed your interpretation of the results, its time to bring it back to the beginning with the conclusion chapter . In other words, its time to (attempt to) answer your original research question s (from way back in chapter 1). Clearly state what your conclusions are in terms of your research questions. This might feel a bit repetitive, as you would have touched on this in the previous chapter, but its important to bring the discussion full circle and explicitly state your answer(s) to the research question(s).

Next, you’ll typically discuss the implications of your findings . In other words, you’ve answered your research questions – but what does this mean for the real world (or even for academia)? What should now be done differently, given the new insight you’ve generated?

Lastly, you should discuss the limitations of your research, as well as what this means for future research in the area. No study is perfect, especially not a Masters-level. Discuss the shortcomings of your research. Perhaps your methodology was limited, perhaps your sample size was small or not representative, etc, etc. Don’t be afraid to critique your work – the markers want to see that you can identify the limitations of your work. This is a strength, not a weakness. Be brutal!

This marks the end of your core chapters – woohoo! From here on out, it’s pretty smooth sailing.

The reference list is straightforward. It should contain a list of all resources cited in your dissertation, in the required format, e.g. APA , Harvard, etc.

It’s essential that you use reference management software for your dissertation. Do NOT try handle your referencing manually – its far too error prone. On a reference list of multiple pages, you’re going to make mistake. To this end, I suggest considering either Mendeley or Zotero. Both are free and provide a very straightforward interface to ensure that your referencing is 100% on point. I’ve included a simple how-to video for the Mendeley software (my personal favourite) below:

Some universities may ask you to include a bibliography, as opposed to a reference list. These two things are not the same . A bibliography is similar to a reference list, except that it also includes resources which informed your thinking but were not directly cited in your dissertation. So, double-check your brief and make sure you use the right one.

The very last piece of the puzzle is the appendix or set of appendices. This is where you’ll include any supporting data and evidence. Importantly, supporting is the keyword here.

Your appendices should provide additional “nice to know”, depth-adding information, which is not critical to the core analysis. Appendices should not be used as a way to cut down word count (see this post which covers how to reduce word count ). In other words, don’t place content that is critical to the core analysis here, just to save word count. You will not earn marks on any content in the appendices, so don’t try to play the system!

Time to recap…

And there you have it – the traditional dissertation structure and layout, from A-Z. To recap, the core structure for a dissertation or thesis is (typically) as follows:

- Acknowledgments page

Most importantly, the core chapters should reflect the research process (asking, investigating and answering your research question). Moreover, the research question(s) should form the golden thread throughout your dissertation structure. Everything should revolve around the research questions, and as you’ve seen, they should form both the start point (i.e. introduction chapter) and the endpoint (i.e. conclusion chapter).

I hope this post has provided you with clarity about the traditional dissertation/thesis structure and layout. If you have any questions or comments, please leave a comment below, or feel free to get in touch with us. Also, be sure to check out the rest of the Grad Coach Blog .

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

36 Comments

many thanks i found it very useful

Glad to hear that, Arun. Good luck writing your dissertation.

Such clear practical logical advice. I very much needed to read this to keep me focused in stead of fretting.. Perfect now ready to start my research!

what about scientific fields like computer or engineering thesis what is the difference in the structure? thank you very much

Thanks so much this helped me a lot!

Very helpful and accessible. What I like most is how practical the advice is along with helpful tools/ links.

Thanks Ade!

Thank you so much sir.. It was really helpful..

You’re welcome!

Hi! How many words maximum should contain the abstract?

Thank you so much 😊 Find this at the right moment

You’re most welcome. Good luck with your dissertation.

best ever benefit i got on right time thank you

Many times Clarity and vision of destination of dissertation is what makes the difference between good ,average and great researchers the same way a great automobile driver is fast with clarity of address and Clear weather conditions .

I guess Great researcher = great ideas + knowledge + great and fast data collection and modeling + great writing + high clarity on all these

You have given immense clarity from start to end.

Morning. Where will I write the definitions of what I’m referring to in my report?

Thank you so much Derek, I was almost lost! Thanks a tonnnn! Have a great day!

Thanks ! so concise and valuable

This was very helpful. Clear and concise. I know exactly what to do now.

Thank you for allowing me to go through briefly. I hope to find time to continue.

Really useful to me. Thanks a thousand times

Very interesting! It will definitely set me and many more for success. highly recommended.

Thank you soo much sir, for the opportunity to express my skills

Usefull, thanks a lot. Really clear

Very nice and easy to understand. Thank you .

That was incredibly useful. Thanks Grad Coach Crew!

My stress level just dropped at least 15 points after watching this. Just starting my thesis for my grad program and I feel a lot more capable now! Thanks for such a clear and helpful video, Emma and the GradCoach team!

Do we need to mention the number of words the dissertation contains in the main document?

It depends on your university’s requirements, so it would be best to check with them 🙂

Such a helpful post to help me get started with structuring my masters dissertation, thank you!

Great video; I appreciate that helpful information

It is so necessary or avital course

This blog is very informative for my research. Thank you

Doctoral students are required to fill out the National Research Council’s Survey of Earned Doctorates

wow this is an amazing gain in my life

This is so good

How can i arrange my specific objectives in my dissertation?

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- What Is A Literature Review (In A Dissertation Or Thesis) - Grad Coach - […] is to write the actual literature review chapter (this is usually the second chapter in a typical dissertation or…

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

/images/cornell/logo35pt_cornell_white.svg" alt="dissertation writing hints"> Cornell University --> Graduate School

Guide to writing your thesis/dissertation, definition of dissertation and thesis.

The dissertation or thesis is a scholarly treatise that substantiates a specific point of view as a result of original research that is conducted by students during their graduate study. At Cornell, the thesis is a requirement for the receipt of the M.A. and M.S. degrees and some professional master’s degrees. The dissertation is a requirement of the Ph.D. degree.

Formatting Requirement and Standards

The Graduate School sets the minimum format for your thesis or dissertation, while you, your special committee, and your advisor/chair decide upon the content and length. Grammar, punctuation, spelling, and other mechanical issues are your sole responsibility. Generally, the thesis and dissertation should conform to the standards of leading academic journals in your field. The Graduate School does not monitor the thesis or dissertation for mechanics, content, or style.

“Papers Option” Dissertation or Thesis

A “papers option” is available only to students in certain fields, which are listed on the Fields Permitting the Use of Papers Option page , or by approved petition. If you choose the papers option, your dissertation or thesis is organized as a series of relatively independent chapters or papers that you have submitted or will be submitting to journals in the field. You must be the only author or the first author of the papers to be used in the dissertation. The papers-option dissertation or thesis must meet all format and submission requirements, and a singular referencing convention must be used throughout.

ProQuest Electronic Submissions

The dissertation and thesis become permanent records of your original research, and in the case of doctoral research, the Graduate School requires publication of the dissertation and abstract in its original form. All Cornell master’s theses and doctoral dissertations require an electronic submission through ProQuest, which fills orders for paper or digital copies of the thesis and dissertation and makes a digital version available online via their subscription database, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses . For master’s theses, only the abstract is available. ProQuest provides worldwide distribution of your work from the master copy. You retain control over your dissertation and are free to grant publishing rights as you see fit. The formatting requirements contained in this guide meet all ProQuest specifications.

Copies of Dissertation and Thesis

Copies of Ph.D. dissertations and master’s theses are also uploaded in PDF format to the Cornell Library Repository, eCommons . A print copy of each master’s thesis and doctoral dissertation is submitted to Cornell University Library by ProQuest.

Five common mistakes to avoid when writing your doctoral dissertation

Business student farn sritrairatana shares five common slip-ups to avoid when writing your doctoral dissertation.

Farn Sritrairatana

Writing a doctoral dissertation is a significant milestone in your academic journey and it’s essential to do it right. Many students, including myself, make these common mistakes that can hinder progress and affect the quality of your work.

So, from my experience, here are five common mistakes to avoid when writing your doctoral dissertation.

Lack of planning and structure

At the beginning of my dissertation journey, I didn’t have a clear plan. I was eager to start as soon as possible, and this led to disorganised writing and a lack of focus.

To avoid this mistake, create a detailed outline of your dissertation, including chapter titles and subheadings. This will help you stay on track and ensure that your dissertation is coherent and well organised.

Ignoring feedback

Throughout your coursework, you’ll have several opportunities to present your progress and receive feedback from your cohort, professors and advisers. This feedback is valuable in helping you stay on track and develop your research.

Keep track of the feedback you receive as it could lead to identifying a valuable research gap. Be open to receiving critical feedback and be willing to make revisions.

This will help you improve the quality of your dissertation and ensure that it meets the requirements of your programme.

Poor time management

Writing a doctoral dissertation requires a significant amount of time and effort. Many students may also have jobs, family commitments and other social responsibilities. Although doctoral programmes are often completed over a few years it’s vital to maintain your momentum throughout.

Create a realistic structure to work on your dissertation on a weekly basis, as well as setting goals and milestones. Break down your writing into manageable chunks and set deadlines for each section. This will help you stay on track and ensure that you allocate enough time during your busy schedule to complete your dissertation to the best of your ability.

How to write an undergraduate university dissertation How to choose a topic for your dissertation How to write a successful research piece at university

Lack of impact

A doctoral dissertation should make a significant contribution to the academic community. At the beginning of my journey, I found it difficult to find a unique perspective and research gap. However, talking to my adviser, professors and peers from industry about my research provided fresh perspectives on my topic.

If you already have a topic in mind for your research, considering it from various angles can enhance the impact of your publication. By examining your work from different perspectives, you can uncover new insights and connections that enrich your findings. This broader approach can make your research more meaningful and influential within your field, contributing to its overall significance.

Ignoring the importance of style and formatting

A doctoral dissertation is a formal academic document, and the style and formatting are just as important as the content, especially if you’re planning to submit your research to an academic journal.

Throughout your literature review, you’ll come across many writing styles, content structures and document formats. Use the style and format that meets the requirements of your programme and the academic journal that you’re planning to submit.

Familiarise yourself with the style and formatting guidelines provided by your discipline to ensure that your dissertation meets these standards. This will save you time and prevent the need to rewrite your document in the future.

Writing a doctoral dissertation is about communicating your research findings and the insights that you’ve gained through your discovery. You’ll experience many highs and lows throughout this long and challenging journey. However, by avoiding some of these common mistakes, you can ensure that your dissertation will be well organised, well researched and provides a new insight to your discipline.

You may also like

.css-185owts{overflow:hidden;max-height:54px;text-indent:0px;} Tips for writing a convincing thesis

Clinton Golding

How to reference at university level

Grace McCabe

What is the difference between a postgraduate taught master’s and a postgraduate research master’s?

Richard Carruthers

Register free and enjoy extra benefits

May 15, 2024

Tips and Resources for a Successful Summer of Dissertation Writing

By Yana Zlochistaya

Summer can be a strange time for graduate students. Gone are the seminars and workshops, the student clubs, and the working group, that structured the semester and provided us with a sense of community. Instead, we’re faced with a three-month expanse of time that can feel equal parts liberating and intimidating. This double-edged freedom is only exacerbated for those of us in the writing stage of our dissertation, when isolation and a lack of discipline can have a particularly big impact. For those hoping not to enter another summer with lofty plans, only to blink and find ourselves in August disappointed with our progress, we’ve compiled some tips and resources that can help.

According to Graduate Writing Center Director Sabrina Soracco, the most important thing you can do to set yourself up for writing success is to clarify your goals. She recommends starting this process by looking at departmental requirements for a completed dissertation. Consider when you would like to file and work backwards from that point, determining what you have to get done in order to hit that target. Next, check in with your dissertation committee members to set up an accountability structure. Would they prefer an end-of-summer update to the whole committee? A monthly check-in with your chair or one of your readers? Setting up explicit expectations that work for you and your committee can cut through the aimlessness that comes with a major writing project.

For those early on in their dissertation-writing process, a committee meeting is also a valuable opportunity to set parameters. “One of the problems with the excitement for the discipline that happens post-quals is that it results in too many ideas,” says Director Soracco. Your committee members should give you input on productive research directions so that you can begin to hone in on your project. It is also important to remember that your dissertation does not have to be the end-all-and-be-all of your academic research. Ideas that do not fit into its scope can end up becoming conference papers or even book chapters.

Once you have a clear goal that you have discussed with your committee, the hard part begins: you have to actually write. The Graduate Writing Center offers several resources to make that process easier:

- The Graduate Writing Community. This is a totally remote, two-month program that is based on a model of “gentle accountability.” When you sign up, you are added to a bCourses site moderated by a Graduate Writing Consultant. At the beginning of the week, everyone sets their goals in a discussion post, and by the end of the week, everyone checks in with progress updates. During the week, the writing consultants offer nine hours of remote synchronous writing sessions. As a writing community member, you can attend whichever sessions work best for your schedule. All that’s required is that you show up, set a goal for that hour, and work towards that goal for the length of two 25-minute Pomodoro sessions . This year’s summer writing community will begin in June. Keep your eye on your email for the registration link!

- Writing Consultations : As a graduate student, you can sign up for an individual meeting with a Graduate Writing Consultant. They can give you feedback on your work, help you figure out the structure of a chapter, or just talk through how to get started on a writing project.

- Independent Writing Groups: If you would prefer to write with specific friends or colleagues, you can contact Graduate Writing Center Director Sabrina Soracco at [email protected] so that she can help you set up your own writing group. The structure and length of these groups can differ; often, members will send each other one to five pages of writing weekly and meet the next day for two hours to provide feedback and get advice. Sometimes, groups will meet up not only to share writing, but to work in a common space before coming together to debrief. Regardless of what the groups look like, the important thing is to create a guilt-free space. Some weeks, you might submit an outline; other weeks, it might be the roughest of rough drafts; sometimes, you might come to a session without having submitted anything. As long as we continue to make progress (and show up even when we don’t), we’re doing what we need to. As Director Soracco puts it, “it often takes slogging through a lot of stuff to get to that great epiphany.”

Yana Zlochistaya is a fifth-year graduate student in the Department of Comparative Literature and a Professional Development Liaison with the Graduate Division. She previously served as a co-director for Beyond Academia.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

What Is a Dissertation? | 5 Essential Questions to Get Started

Published on 26 March 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on 5 May 2022.

A dissertation is a large research project undertaken at the end of a degree. It involves in-depth consideration of a problem or question chosen by the student. It is usually the largest (and final) piece of written work produced during a degree.

The length and structure of a dissertation vary widely depending on the level and field of study. However, there are some key questions that can help you understand the requirements and get started on your dissertation project.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

When and why do you have to write a dissertation, who will supervise your dissertation, what type of research will you do, how should your dissertation be structured, what formatting and referencing rules do you have to follow, frequently asked questions about dissertations.

A dissertation, sometimes called a thesis, comes at the end of an undergraduate or postgraduate degree. It is a larger project than the other essays you’ve written, requiring a higher word count and a greater depth of research.

You’ll generally work on your dissertation during the final year of your degree, over a longer period than you would take for a standard essay . For example, the dissertation might be your main focus for the last six months of your degree.

Why is the dissertation important?

The dissertation is a test of your capacity for independent research. You are given a lot of autonomy in writing your dissertation: you come up with your own ideas, conduct your own research, and write and structure the text by yourself.

This means that it is an important preparation for your future, whether you continue in academia or not: it teaches you to manage your own time, generate original ideas, and work independently.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

During the planning and writing of your dissertation, you’ll work with a supervisor from your department. The supervisor’s job is to give you feedback and advice throughout the process.

The dissertation supervisor is often assigned by the department, but you might be allowed to indicate preferences or approach potential supervisors. If so, try to pick someone who is familiar with your chosen topic, whom you get along with on a personal level, and whose feedback you’ve found useful in the past.

How will your supervisor help you?

Your supervisor is there to guide you through the dissertation project, but you’re still working independently. They can give feedback on your ideas, but not come up with ideas for you.

You may need to take the initiative to request an initial meeting with your supervisor. Then you can plan out your future meetings and set reasonable deadlines for things like completion of data collection, a structure outline, a first chapter, a first draft, and so on.

Make sure to prepare in advance for your meetings. Formulate your ideas as fully as you can, and determine where exactly you’re having difficulties so you can ask your supervisor for specific advice.

Your approach to your dissertation will vary depending on your field of study. The first thing to consider is whether you will do empirical research , which involves collecting original data, or non-empirical research , which involves analysing sources.

Empirical dissertations (sciences)

An empirical dissertation focuses on collecting and analysing original data. You’ll usually write this type of dissertation if you are studying a subject in the sciences or social sciences.

- What are airline workers’ attitudes towards the challenges posed for their industry by climate change?

- How effective is cognitive behavioural therapy in treating depression in young adults?

- What are the short-term health effects of switching from smoking cigarettes to e-cigarettes?

There are many different empirical research methods you can use to answer these questions – for example, experiments , observations, surveys , and interviews.

When doing empirical research, you need to consider things like the variables you will investigate, the reliability and validity of your measurements, and your sampling method . The aim is to produce robust, reproducible scientific knowledge.

Non-empirical dissertations (arts and humanities)

A non-empirical dissertation works with existing research or other texts, presenting original analysis, critique and argumentation, but no original data. This approach is typical of arts and humanities subjects.

- What attitudes did commentators in the British press take towards the French Revolution in 1789–1792?

- How do the themes of gender and inheritance intersect in Shakespeare’s Macbeth ?

- How did Plato’s Republic and Thomas More’s Utopia influence nineteenth century utopian socialist thought?

The first steps in this type of dissertation are to decide on your topic and begin collecting your primary and secondary sources .

Primary sources are the direct objects of your research. They give you first-hand evidence about your subject. Examples of primary sources include novels, artworks and historical documents.

Secondary sources provide information that informs your analysis. They describe, interpret, or evaluate information from primary sources. For example, you might consider previous analyses of the novel or author you are working on, or theoretical texts that you plan to apply to your primary sources.

Dissertations are divided into chapters and sections. Empirical dissertations usually follow a standard structure, while non-empirical dissertations are more flexible.

Structure of an empirical dissertation

Empirical dissertations generally include these chapters:

- Introduction : An explanation of your topic and the research question(s) you want to answer.

- Literature review : A survey and evaluation of previous research on your topic.

- Methodology : An explanation of how you collected and analysed your data.

- Results : A brief description of what you found.

- Discussion : Interpretation of what these results reveal.

- Conclusion : Answers to your research question(s) and summary of what your findings contribute to knowledge in your field.

Sometimes the order or naming of chapters might be slightly different, but all of the above information must be included in order to produce thorough, valid scientific research.

Other dissertation structures

If your dissertation doesn’t involve data collection, your structure is more flexible. You can think of it like an extended essay – the text should be logically organised in a way that serves your argument:

- Introduction: An explanation of your topic and the question(s) you want to answer.

- Main body: The development of your analysis, usually divided into 2–4 chapters.

- Conclusion: Answers to your research question(s) and summary of what your analysis contributes to knowledge in your field.

The chapters of the main body can be organised around different themes, time periods, or texts. Below you can see some example structures for dissertations in different subjects.

- Political philosophy

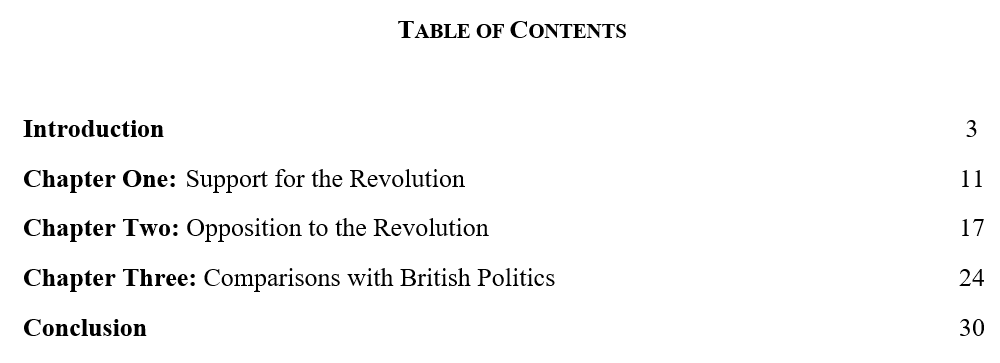

This example, on the topic of the British press’s coverage of the French Revolution, shows how you might structure each chapter around a specific theme.

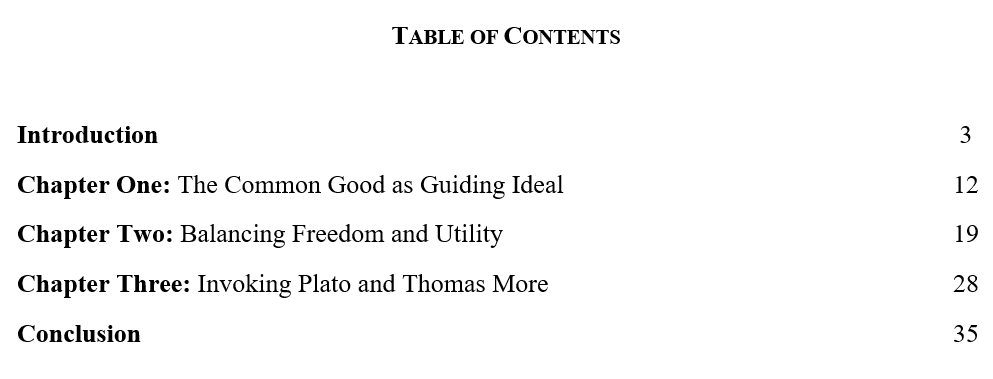

This example, on the topic of Plato’s and More’s influences on utopian socialist thought, shows a different approach to dividing the chapters by theme.

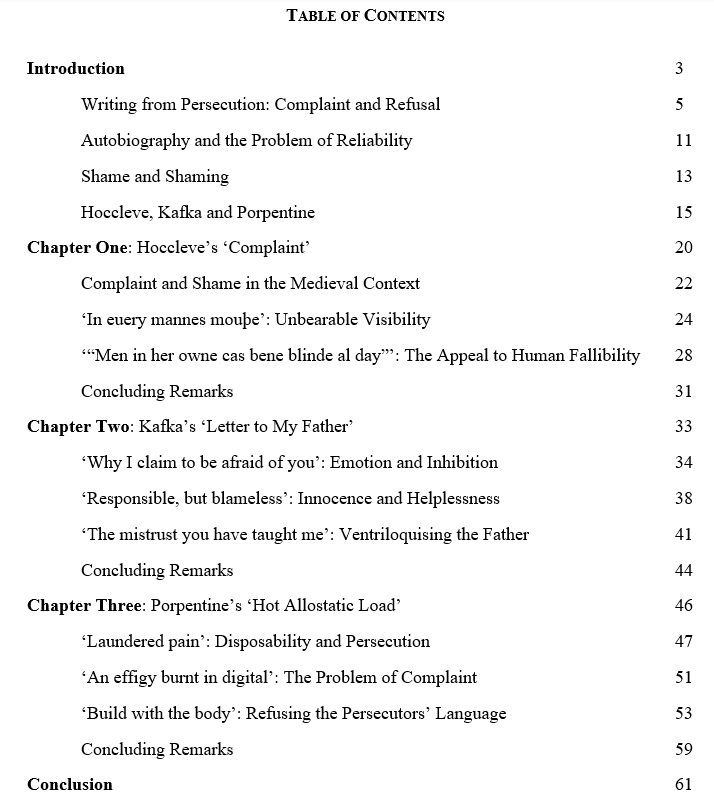

This example, a master’s dissertation on the topic of how writers respond to persecution, shows how you can also use section headings within each chapter. Each of the three chapters deals with a specific text, while the sections are organised thematically.

Like other academic texts, it’s important that your dissertation follows the formatting guidelines set out by your university. You can lose marks unnecessarily over mistakes, so it’s worth taking the time to get all these elements right.

Formatting guidelines concern things like:

- line spacing

- page numbers

- punctuation

- title pages

- presentation of tables and figures

If you’re unsure about the formatting requirements, check with your supervisor or department. You can lose marks unnecessarily over mistakes, so it’s worth taking the time to get all these elements right.

How will you reference your sources?

Referencing means properly listing the sources you cite and refer to in your dissertation, so that the reader can find them. This avoids plagiarism by acknowledging where you’ve used the work of others.

Keep track of everything you read as you prepare your dissertation. The key information to note down for a reference is:

- The publication date

- Page numbers for the parts you refer to (especially when using direct quotes)

Different referencing styles each have their own specific rules for how to reference. The most commonly used styles in UK universities are listed below.

You can use the free APA Reference Generator to automatically create and store your references.

APA Reference Generator

The words ‘ dissertation ’ and ‘thesis’ both refer to a large written research project undertaken to complete a degree, but they are used differently depending on the country:

- In the UK, you write a dissertation at the end of a bachelor’s or master’s degree, and you write a thesis to complete a PhD.

- In the US, it’s the other way around: you may write a thesis at the end of a bachelor’s or master’s degree, and you write a dissertation to complete a PhD.

The main difference is in terms of scale – a dissertation is usually much longer than the other essays you complete during your degree.

Another key difference is that you are given much more independence when working on a dissertation. You choose your own dissertation topic , and you have to conduct the research and write the dissertation yourself (with some assistance from your supervisor).

Dissertation word counts vary widely across different fields, institutions, and levels of education:

- An undergraduate dissertation is typically 8,000–15,000 words

- A master’s dissertation is typically 12,000–50,000 words

- A PhD thesis is typically book-length: 70,000–100,000 words

However, none of these are strict guidelines – your word count may be lower or higher than the numbers stated here. Always check the guidelines provided by your university to determine how long your own dissertation should be.

At the bachelor’s and master’s levels, the dissertation is usually the main focus of your final year. You might work on it (alongside other classes) for the entirety of the final year, or for the last six months. This includes formulating an idea, doing the research, and writing up.

A PhD thesis takes a longer time, as the thesis is the main focus of the degree. A PhD thesis might be being formulated and worked on for the whole four years of the degree program. The writing process alone can take around 18 months.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2022, May 05). What Is a Dissertation? | 5 Essential Questions to Get Started. Scribbr. Retrieved 14 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/what-is-a-dissertation/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to choose a dissertation topic | 8 steps to follow, how to write a dissertation proposal | a step-by-step guide, what is a literature review | guide, template, & examples.

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Knowledge Hub

Thesis/Dissertation Writing Guide

- 35-minute read

- 12th February 2021

How to Write a Great Thesis or Dissertation

This guide will explain how to write a great undergraduate or master’s thesis or dissertation (see our Essay Writing Guide for advice on shorter academic documents).

Use the list to the left to select an aspect of thesis writing to learn more about.

What Is a Thesis?

A thesis is a longer, in-depth paper written at the end of an undergraduate or master’s degree. It will be on a subject you choose yourself and involve self-directed research, although with some help from a tutor or advisor. The thesis may make a significant contribution towards your final grade, so it is very important. We will use the word “thesis” throughout this guide, but some also call this final project a “dissertation.”

The idea of an undergraduate thesis (also known as a “senior project” or “senior thesis”) is to demonstrate the skills and knowledge developed during your studies. Not every undergraduate will need to do a senior thesis, but they are common in some schools and may be required if you’re planning on enrolling for a postgraduate course.

A master’s thesis is the final project on a master’s degree. It will usually be longer and more detailed than an undergraduate thesis. You may also be required to make an original contribution (i.e., put forward a new argument) as well as demonstrating your knowledge.

Depending on your subject area, your thesis may be empirical or non-empirical:

- Empirical theses are more common in the sciences. They involve collecting and analyzing data, then writing this up with your findings and conclusions.

- Non-empirical theses are more common in the humanities. They involve researching existing data, ideas, and arguments, then offering a critical analysis or making an argument of your own based on your research.

In this guide, we will discuss both types of thesis, highlighting any differences as they become relevant. We will not look at how to write a doctoral dissertation, which is usually even longer and more complex, but many of the same skills apply.

KEY NOTE: Most colleges and universities have detailed guidelines for how students should write a thesis, including any stylistic or procedural requirements. The advice below will be designed to apply to any thesis-length project, but you still need to check what your institution requires if you are writing a thesis or dissertation.

Planning a Thesis or Dissertation

The first step in writing a thesis is making a plan. This may include several steps.

Selecting a Topic

Since a thesis is self-directed, you will need to decide what to research. This is an important decision, so don’t rush it! Tips for selecting a thesis topic include:

- Think about your interests – Try to pick something that reflects your interests. Is there something from your prior studies you wish you’d had more time with? Some subject area that you found especially engaging? Something you read about that you didn’t get the chance to study? Something relevant to your career plans? A thesis is a major project, so make sure it focuses on something you care about!

- Aim for originality – Try to find a unique issue or problem to address. This doesn’t necessarily mean conducting entirely original research (it will be hard to find something nobody has ever written about). But you can try to find a new angle on an existing idea or problem (e.g., applying an established theory in a new area). This is especially important for a master’s thesis, where originality is valued.

- Think about the scope – Try to pick a problem that you think you can answer within the word limit of your thesis. This should be something fairly in depth so you can show off your skills and hit the word count. But it should also be narrow enough that you can finish it in time and without massively overwriting!

- Do some research – If you have an idea for something you might want to write about, do a little preliminary research. This will help you focus your idea by seeing what other people have already said on the subject. It may even help you identify a new angle from which to approach the issue. And if you do a little research on a few potential topics, you can be sure you’ve picked the right one for your thesis.

- Be realistic – As with the scope of your chosen topic, you need to be realistic about what you can do with the time and resources available. Would your topic require access to specialist equipment or resources? Would it require traveling? Are there any potential costs? Think about how easy it will be to conduct your research.

- Ask for advice – Once you have a basic idea of what you might want to write about, ask your tutor or lecturer for advice. They will have a good sense of whether it is a suitable subject for a thesis and may have suggestions for how to approach it.

And once you’ve selected a topic, you’ll want to check what your school requires for a dissertation. Usually, you will need to submit a research proposal of some kind for approval. Minimally, though, you will need to decide on a research question.

Setting a Research Question

The “ research question ” is the question you’ll seek to answer in your thesis. This should narrow the focus of your thesis down even more, giving you a distinct problem to address. To formulate a research question, try to come up with something that:

- Clearly sets out the focus of your research

- Has a limited enough scope to answer in one paper

- Is complex enough to warrant in-depth discussion and investigation

- Is relevant to your field of study (e.g. it fills a gap in the research)

For instance, you may be interested in viral marketing techniques. However, since this would be a very broad topic for a thesis, you would then need to look for a specific question to answer, such as how do social media influencers affect a viral advertising campaign? You could even narrow this down further by framing a question around a specific case study.

We can see some examples of “good” and “bad” questions below.

In this case, the “bad” question is too broad. It would take several book-length essays to even start answering! The second question is much narrower, focusing on the effect of climate change on one species in one region, making it easier to answer.

In this case, the “bad” question is too narrow. It could be answered by searching on google and simply setting out the policies you find. The second question, meanwhile, is open to debate and does not have a simple answer, so there is scope for good research.

As with your thesis topic, once you have come up with a research question, speak to your advisor or tutor. They may have some guidance on how to refine it.

Writing a Research Proposal

Some colleges will ask you to write a research proposal – i.e., a detailed description of your proposed research project – before they approve your thesis. And even if you don’t have to do this, writing a research proposal can be a useful way to organize your thoughts before you begin writing. This may include information on the following:

- A proposed title

- Your research question/ objectives

- Why your research is significant (e.g., what it contributes to your field of study or how it could be used to help solve a practical problem)

- An initial literature review (i.e., a look at existing research in the subject area)

- A thesis chapter outline (see below for tips on structure)

- Your methods (i.e., how you will conduct research or experimentation)

- A justification for why you will study the topic in the manner set out

- Logistical and ethical considerations

- Potential limitations on your research project

- A reference list or bibliography

- A research timeline breaking down when you will complete each stage of the project, including writing up and editing your thesis

- Any information on projected expenses or budget

You won’t always need all the above. This will depend on your school’s requirements, your subject area, and the scope of your thesis project. In essence, though, you need to set out what you want to achieve, why you want to do this, and how you intend to accomplish it.

One thing to note here is that your plan may change later on. Research can be difficult to predict, so you may need to adapt your plan after you start work on your thesis. You might find, for example, that your research question was too broad. Or you might encounter an obstacle that forces you to adapt your plans. This is completely normal!

As such, don’t stress too much about making your research plan “perfect.” Your real aim is to prove that you’ve thought seriously about your thesis, that you’re capable of planning a research project, and that you’re committed to producing high quality work.

Once your school has approved your plan, you will be ready to begin work on your thesis.

Conducting Research

Any thesis will require engaging with past research. This may be for a literature review before conducting your own experimental study. Or, in a more theoretical thesis (e.g., historical analysis or literary criticism), it may make up a large proportion of your work.

You will have done some research already as part of your proposal. But most of it will come after your thesis has been approved. Exactly what this will involve will depend on your subject area and research question, but we will look at a few common issues below.

Creating a Research Plan

Creating a plan will help you focus your research. To do this, break your thesis down into steps and set aside time for each task you need to complete. You’ll then know exactly how much you need to do and how long you will need to do it. This may include:

- Studying existing literature on your research topic

- Designing a study or experiment

- Conducting primary research

When creating this plan, be realistic about how long each stage will take. And make sure to leave time for writing and editing your thesis once you’ve finished the research!

Top Tip! You can actually start writing while you’re still doing research or gathering data. For example, if you’re working on your design study, you can start making notes for your methodology section. This will save time when you come to write your thesis, as you should have all the information you need in one place, ready to be written up.

Selecting Sources

Part of efficient research is selecting the best sources for your project, as reading every single book or article on a subject would take far too long. This may involve:

- Using what you know from your studies as a starting point for finding relevant sources. Asking your tutors or lecturers for recommendations is another good idea.

- Checking the reference lists in good sources for similar titles.

- Developing a strong search strategy to find sources online or in databases. This means testing keywords and using filters to narrow searches.

If you are doing research online, make sure you’re using reliable academic sources, too. For instance, a reputable journal or a university website should be trustworthy. But a blog post with no cited sources or author information will not be suitable for academic writing. Likewise, Wikipedia is not an academic source, though you can check the citations to find sources.

Top Tip! If you are writing a thesis in the humanities, the majority of your work may involve analyzing, criticizing, and comparing secondary sources or ideas from these sources. As such, it is vital to find and engage with the major thinkers in your subject area.

For instance, if you were writing about behavioral psychology, and your thesis did not acknowledge or engage with B. F. Skinner – a hugely influential figure in behaviorism – at any point, your marker may assume you haven’t done enough research or that you have missed something important. And this may affect how they assess the rest of your work.

Even if your thesis is mainly based on primary research, it is important to show that you’ve researched past work in your subject area. If you overlook a major thinker or some recent research relevant to your own study, it could end up losing you marks!

Taking and Organizing Notes

Writing a thesis will be much simpler if you have good notes to work from. So when you’re reading a paper or book relevant to your research, make sure to:

- Take notes that are neat enough to understand when you read them.

- Note all publication details for any source you might use in your thesis.

- Organize notes so you can find them when needed (e.g., using colored labels to sort paper notes visually and having a well-labeled folder system on your computer).

- Highlight important information so that you can find it later.

Other tips for efficient note taking include:

- Use abbreviations or shorthand to aid note taking (especially in lectures).

- Summarize key passages and ideas rather than writing them down verbatim. This will make note taking quicker, as well as helping you absorb the information.

- Focus on the parts of sources most relevant to your research question.

- Record page numbers and source information for anything you make notes about.

- Use an audio recording device to record lectures.

This should leave you with detailed, easy-to-use notes when you come to write your thesis.

Data Collection and Analysis

If you are conducting empirical or experimental research, part of your research will involve data collection. This is where you gather your own information to help answer your research question. The three main styles of research include:

- Quantitative – Research that depends on numerical data. This can be based on a scientific experiment, questionnaires, or many other methods.

- Qualitative – Research that focuses on the distinguishing characteristics or traits of the thing studied, such as how something is subjectively experienced. Qualitative methods include things such as interviews, focus groups, and observations.

- Mixed methods – Research that combines quantitative and qualitative methods. The aim here is to get a more rounded picture of the thing being studied.

The same applies to data analysis methods, which can also be quantitative or qualitative. But the research approach you adopt will have a major influence on how you answer your research question, so you need to think about this carefully! Key factors may include:

- Past research – How have other studies in your subject area been done? Is there something about a past study you could draw on or improve upon? Is there existing data that you could use (e.g., from past studies or metastudies)?

- Practicality – How easy will it be to conduct your study with the resources available? How will you collect and store data? How will you analyze it after collection?

- Sampling – Where will you gather data? Will you be able to generalize it to a wider population? If you are working with human subjects, are there ethical concerns?

- Problem solving – What obstacles might you face when gathering data? Do you have time to run a pilot study (i.e., a test study) before you begin?

You may have decided on much of this while writing your research proposal, but these are issues you should consider throughout the study design process. You may also want to work with your thesis advisor to finalize your plans before collecting data.

From a planning perspective, the key is giving yourself enough time to carry out each stage of the data collection and analysis. If you rush, things are more likely to go wrong!

Writing Up Your Thesis

The structure of a thesis.

The structure of your thesis will depend heavily on the subject area. As such, we will look at how to structure empirical and non-empirical theses separately. However, as elsewhere, make sure to check what your school suggests about structuring your thesis.

Empirical Thesis Structure

Most empirical theses have a structure along the following lines:

- Title page – A page with key information about your thesis, typically including your name, the title, and the date of submission. Your school should have a standard template for thesis title pages, so make sure to check this.

- Abstract – A very short summary of your research and results.

- Content page(s) – A list of chapters/sections in your thesis. You may also need to include lists of charts, illustrations, or even abbreviations.

- Introduction – An opening chapter that sets out your research aims. It should provide any key information a reader would need to follow your thesis.

- Literature review – An examination of the most important and most up-to-date research and theoretical thought relevant to your thesis topic.

- Methodology – A detailed explanation of how you collected and analyzed data.

- Results and discussion – A section setting out the results you achieved, your analysis, and your findings based on the data. You may want to include charts, graphs and other visual methods to present key findings clearly.

- Conclusions – A final section summarizing your work and the conclusions drawn.

- References – A list of all sources used during your research.

- Appendices – Any additional documentation that is relevant to your study but would not fit in the main thesis (e.g. questionnaires, surveys, raw data).

We will look at some of these sections in more detail below.

Non-Empirical Thesis Structure

In the humanities and other non-experimental subject areas, your thesis may be structured more like a long essay, with each chapter/section adding to your argument. The structure will therefore depend on what you are arguing, but a common style is:

- Abstract – A very short summary of your research.

- Main chapters – A series of chapters where you address each main point in your argument. Ideally, each chapter should lead naturally to the next one.

- Appendices – Any additional documentation that is relevant to your work but would not fit in the main thesis (e.g., questionnaires, surveys, raw data).

We will look at some of these sections in more detail below. For the main chapters of your thesis, though, you will have to break your argument down into a series of points. To do this, review your notes with your research question in mind, then:

- Write down your main arguments in as few sentences as possible. Try to imagine explaining it to a friend or your advisor in simple terms.

- Expand each sentence with a series of detailed subpoints or premises.

- Look at how each subpoint contributes to the overall argument and use this as a guideline for structuring your thesis. Ideally, each chapter will address a single aspect of your argument in detail, complete with supporting evidence.

It can help to treat each chapter in a humanities thesis like an essay of its own, with an introduction (i.e., what you will address in the chapter at hand), a series of sub-points with evidence, and a short conclusion that leads on to the next chapter.

Writing Your Thesis

Next, we’ll look in detail at some of the sections most theses will include. As elsewhere, though, don’t forget to check your school’s requirements for the structure and content of a thesis, as some elements will vary (e.g., the length of the abstract, or whether to include separate “Results” and “Discussion” sections). If you cannot find this information on your college’s website or in course materials, ask your tutor or advisor for guidance.

Picking a Title

Your thesis title should give readers an immediate sense of what it is about. A good way to do this is to have a title and a subtitle based on topic and focus respectively:

- The topic is the broad subject area of your thesis (e.g., viral marketing techniques, the environmental effects of climate change, or food safety regulations).

- The focus is the specific thing that you are studying (e.g., the impact of social media, the change in polar bear populations, or whether regulations promote public health).

For instance, the following could all work as dissertation titles:

Viral marketing and social media: A case study of the role of influencer culture in the success of Old Spice’s “The Man Your Man Could Smell Like” campaign

Environmental Effects of Climate Change: A Qualitative Study of the Factors Behind Changing Polar Bear Populations in Alaska

Food Safety in America: Are Federal Policies Promoting Public Health?

All these titles give a sense of the question the thesis will answer. The first two are quite long, which can reduce clarity in some cases, but they also include information about the type of research conducted. The key is striking a balance between detail and clarity.

You may also want to check your style guide (or ask your advisor) for advice on how to capitalize titles. You can find information on title case and sentence case capitalization here .

Writing an Abstract

An abstract is like a preview, allowing readers to see what your thesis is about. As such, it should set out the key information about your study in a clear, concise manner.

The exact length and style of an abstract can vary, but typically it will be between 100 and 500 words long and primarily written in the past or present tense. It should include:

- What you aimed to do and why

- How you did it

- What you discovered

- Recommendations (if any)

It often helps to leave writing the abstract until you’ve at least got a first draft of your full thesis, as by that point you’ll have a better sense of your research overall.

Writing an Introduction

A good thesis introduction should set the scene for the reader, telling them everything they’ll need to know to follow the rest of your thesis. It should therefore:

- Establish the subject area and specific focus of your work.

- Explain why the topic is important and your research objectives.

- Offer some background information, including current theories or research.

- Provide a thesis or hypothesis (i.e., a short statement of what you will argue).

- Outline the structure of your thesis (i.e., what each chapter will cover).

It can help to have a strong opening line that will grab the reader’s attention, but this is not necessary. Try to avoid clichéd openings such as “Webster’s Dictionary defines [THESIS TOPIC] as…,” as these will rarely add anything useful to your paper.

One good tip is to write a rough introduction first, but to revisit it once you have a draft of your full thesis. This is because the introduction and conclusion should work like “bookends” to the rest of your thesis, so the introduction needs to reflect the content that follows.

The Literature Review

The literature review provides the theoretical foundations for your thesis. The idea is not just to summarize key concepts and studies, but to set up your own work by showing how it follows from existing research to offer something new. To do this, you may need to:

- Examine key theories or ideas that provide context for your study.

- Read sources critically and assess how they relate to your research.

- Look at the current state of research in your subject area.

- Reflect on the methods and theories used by other researchers.

- Explain how your work will develop or build upon current knowledge.

You can use your research question to guide this review. But it’s also worth asking your advisor or tutor for advice on literature you should read.

When writing up your literature review, make sure it has a clear structure. This might be chronological (i.e., in order of when the studies you discuss were done), methodological (i.e., organized in terms of the research style or approach), or thematic (i.e., organized in terms of what studies focused on or discussed). But you need to give it a clear sense of development, which ultimately should lead back to your own research question.

Methodology

The methodology chapter is where you explain, in detail, how you performed your research. This may be a relatively simple section of your thesis, but make sure to:

- Include something about your research approach (e.g., qualitative vs. quantitative) and why it was the best choice for your study.

- Be descriptive! Make sure to detail each step of how you gathered and analyzed data. This includes any equipment or techniques used, as well as the conditions under which you gathered your data. Ideally, a reader should be able to replicate your research from reading your methodology section.

- Justify your choices. From equipment to analysis, you should have a reason for every decision you make about the methodology of your study.

- Mention any obstacles you faced or any limitations of your chosen methods.

- Consider ethical concerns. If you had to seek approval from an ethics panel to conduct your research, make sure to detail it here.

The appendices can be useful here, as you can use them for information that is relevant but not essential for explaining your methodology (e.g., survey templates, consent forms). If you do include anything like this in your appendices, though, make sure to reference it clearly in your methodology chapter (e.g., “For more information, see Appendix C…”).

Results and Discussion

This is where you set out the results of your research, including data, analysis, and findings.

This can vary a lot depending on your subject area and school. Some use a combined “ Results and Discussion ” section, where results are presented alongside analysis. Some prefer to separate the results and the discussion into separate chapters. As such, you will want to check with your advisor about the best way to present your results.

Generally, though, reliable tips for presenting results in a thesis include:

- Offer context – Raw data may be difficult to follow, so make sure to include enough text to guide the reader through your findings. Ideally, it should be clear how everything in this section helps you to answer your initial research question.

- Focus on the most relevant data – If you’ve collected lots of data, make sure to focus on the parts that are most relevant to your research question. If you try to include everything, key findings may get lost among the information overload.

- Use visuals – If appropriate, consider using charts, graphs, tables, or figures to present results, as these can make complex data easier to visualize. However, make sure to label all charts and figures carefully so their relevance is clear.

The “Discussion” part should focus on the significance of your results. Think about:

- How the data supports (or disproves) your initial hypothesis.

- How your results compare to those of the studies in your literature review.

- Whether any problems encountered during the research, or the previously outlined limitations of your methods, affect the validity of your results.

- The implications of your study for future theory, research, and practice.

Since this is where you really dig into the value of your research, the “Results and Discussion” section may be the most important part of your thesis. As such, you should take time to make sure it thoroughly addresses your chosen research question.

Writing a Conclusion

The conclusion is where you tie everything up together. As mentioned earlier, it should work with the introduction to “bookend” your thesis. As such, it should:

- Start by briefly recapping the thesis topic and your research question.

- Summarize the main points of your argument/your results.

- Draw conclusions and explain how your research supports them.

- Consider the implications of your research (e.g., its significance for your field of study or real-life applications of your results).

Your overall aim is to briefly explain how you have answered your research question. However, make sure not to introduce new arguments or evidence in the conclusion. If you need these to support your point, they should be included in the main body of the thesis.

Referencing and Quoting Sources

In any academic document, you will need to cite sources. This typically means:

- Citing sources in the main text of your thesis.

- Adding a reference list or bibliography at the end of the document.

The details of how to do this will depend on the referencing style or system you’re using, so remember to check your style guide . However, we will offer some general tips here.

Why Cite Sources?

Referencing involves identifying the sources you’ve used in your research, usually with some kind of in-text citations and full publication information for all sources in a reference list.

There are several reasons to take referencing seriously in your thesis:

- You get to show off your research skills and ability to find relevant information.

- It is good practice to credit other thinkers for their ideas.

- It provides vital context for your own work.

- Failing to cite sources will be treated as plagiarism (i.e., using someone else’s words or ideas without crediting them), which could have negative consequences.

This last point is the most important as plagiarism is considered academic fraud. And if you’re found to have plagiarized someone else’s work in your thesis, you will lose marks.

You will need to cite a source whenever you:

- Quote or paraphrase another person’s words.

- Refer to facts or figures that aren’t common public knowledge.

- Refer to an idea or theory you found published somewhere.

- Use an image or illustration that you did not create yourself.

This should protect you from unfair accusations of plagiarism.

In-Text Citations

In-text citations come in three main types, each used by different referencing systems:

- Parenthetical Citations – This involves giving citations in brackets in the main body of your thesis. Often, this will be the author’s surname, the year of publication, and page numbers (e.g., Harvard, APA). However, some systems differ, such as MLA, which only gives the author’s surname and page number(s).

- Number–Footnote Citations – Some referencing systems indicate citations with a number in the text, then give source information in footnotes (e.g., Oxford, MHRA).

- Number–Endnote Citations – Similar to the above, number–endnote systems use numbered citations in the main text (e.g., Vancouver, IEEE). However, in this case the numbers point to an entry in a reference list at the end of the document.

And while these citation styles differ, there are some tips that apply in all cases:

- Always check your school’s style guide to find their preferred citation style.

- Make sure every source used in the main text is cited.

- Make sure that all cited sources are included in a reference list.

- Apply a consistent citation style throughout each essay.

As above, this will help ensure you don’t accidentally commit plagiarism in your writing.

Quoting Sources

Quoting sources is a great way of supporting your arguments in a thesis. However, if you are going to quote a source in your writing, you need to do it right.

The first step is knowing when to quote a source. Generally, this is most useful when:

- Your point depends on the exact wording (e.g., if you are discussing why an author used a specific term in their work).

- The original text is especially well expressed and rephrasing it would detract from this.

If you do quote a source, make sure to place the borrowed text in “quotation marks.” This shows the reader that you have taken it from somewhere else. The accompanying citation should then identify the source and the page(s) where the quote can be found.

In many cases, it is better to paraphrase a source than quote it. This means rewriting the passage in your own words, which shows that you have understood it. However, remember that you still need to cite sources when paraphrasing something.

Reference Lists and Bibliographies

Every academic document that cites sources should include a reference list or bibliography. These terms are sometimes used interchangeably, but the general difference is:

- A reference list is a list of every source cited in your thesis.

- A bibliography should include any source you used while researching your thesis (even the ones that you did not cite directly in your work).