- September 22, 2011

The Knowledge Problem

Studying knowledge is one of those perennial topics—like the nature of matter in the hard sciences—that philosophy has been refining since before the time of Plato. The discipline, epistemology, comes from two Greek words episteme (επιστημη) which means knowledge and logos (λογος) which means a word or reason. Epistemology literally means to reason about knowledge. Epistemologists study what makes up knowledge, what kinds of things can we know, what are the limits to what we can know, and even if it’s possible to actually know anything at all.

Coming up with a definition of knowledge has proven difficult but we’ll take a look at a few attempts and examine the challenges we face in doing so. We’ll look at how prominent philosophers have wrestled with the topic and how postmodernists provide a different viewpoint on the problem of knowledge. We’ll also survey some modern work being done in psychology and philosophy that can help us understand the practical problems with navigating the enormous amounts of information we have at our disposal and how we can avoid problems in the way we come to know things.

Do We Know Stuff?

In order to answer that question, you probably have to have some idea what the term “know” means. If I asked, “Have you seen the flibbertijibbet at the fair today?” I’d guess you wouldn’t know how to answer. You’d probably start by asking me what a flibbertijibbet is. But most adults tend not to ask what knowledge is before they can evaluate whether they have it or not. We just claim to know stuff and most of us, I suspect, are pretty comfortable with that. There are lots of reasons for this but the most likely is that we have picked up a definition over time and have a general sense of what the term means. Many of us would probably say knowledge that something is true involves:

- Certainty – it’s hard if not impossible to deny

- Evidence – it has to based on something

- Practicality – it has to actually work in the real world

- Broad agreement – lots of people have to agree it’s true

But if you think about it, each of these has problems. For example, what would you claim to know that you would also say you are certain of? Let’s suppose you’re not intoxicated, high, or in some other way in your “right” mind and conclude that you know you’re reading an article on the internet. You might go further and claim that denying it would be crazy. Isn’t it at least possible that you’re dreaming or that you’re in something like the Matrix and everything you see is an illusion? Before you say such a thing is absurd and only those who were unable to make the varsity football team would even consider such questions, can you be sure you’re not being tricked? After all, if you are in the Matrix, the robots that created the Matrix would making be making you believe you are not in the Matrix and that you’re certain you aren’t.

What about the “broad agreement” criterion? The problem with this one is that many things we might claim to know are not, and could not be, broadly agreed upon. Suppose you are experiencing a pain in your arm. The pain is very strong and intense. You might tell your doctor that you know you’re in pain. Unfortunately though, only you can claim to know that (and as an added problem, you don’t appear to have any evidence for it either—you just feel the pain). So at least on the surface, it seems you know things that don’t have broad agreement by others.

These problems and many others are what intrigue philosophers and are what make coming up with a definition of knowledge challenging. Since it’s hard to nail down a definition, it also makes it hard to answer the question “what do you know?”

What is Knowledge?

As with many topics in philosophy, a broadly-agreed-upon definition is difficult. But philosophers have been attempting to construct one for centuries. Over the years, a trend has developed in the philosophical literature and a definition has emerged that has such wide agreement it has come to be known as the “standard definition.” While agreement with the definition isn’t universal, it can serve as a solid starting point for studying knowledge.

The definition involves three conditions and philosophers say that when a person meets these three conditions, she can say she knows something to be true. Take a statement of fact: The Seattle Mariners have never won a world series.  On the standard definition, a person knows this fact if:

- The person believes the statement to be true

- The statement is in fact true

- The person is justified in believing the statement to be true

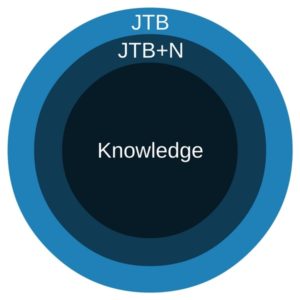

The bolded terms earmark the three conditions that must be met and because of those terms, the definition is also called the “tripartite” (three part) definition or “JTB” for short. Many many books have been written on each of the three terms so I can only briefly summarize here what is going on in each. I will say up front though that epistemologists spend most of their time on the third condition.

First, beliefs are things people have. Beliefs aren’t like rocks or rowboats where you come across them while strolling along the beach. They’re in your head and generally are viewed as just the way you hold the world (or some aspect of the world) to be. If you believe that the Mariners never won a world series, you just accept it is as true that the Mariners really never won a world series. Notice that accepting that something is true implies that what you accept could be wrong. In other words, it implies that what you think about the world may not match up with the way the world really is. This implies that there is a distinction between belief and truth . There are some philosophers—notably postmodernists and existentialists—who think such a distinction can’t be made which we’ll examine more below. But in general, philosophers claim that belief is in our heads and truth is about the way the world is. In practical terms, you can generally figure out what you or someone else believes by examining behavior. People will generally act according to what they really believe rather than what they say they believe—despite what Dylan says .

Something is true if the world really is that way. Truth is not in your head but is “out there.” The statement, “The Mariners have never won a world series” is true if the Mariners have never won a world series. The first part of that sentence is in quotes on purpose. The phrase in quotes signifies a statement we might make about the world and the second, unquoted phrase is supposed to describe the way the world actually is. The reason philosophers write truth statements this way is to give sense to the idea that a statement about the world could be wrong or, more accurately, false (philosophers refer to the part in quotes as a statement or proposition ). Perhaps you can now see why beliefs are different than truth statements. When you believe something, you hold that or accept that a statement or proposition is true. It could be false that’s why your belief may not “match up” with the way the world really is. For more on what truth is, see the Philosophy News article, “ What is Truth? ”

Justification

If the seed of knowledge is belief, what turns belief into knowledge? This is where justification (sometimes called ‘warrant’) comes in. A person knows something if they’re justified in believing it to be true (and, of course, it actually is true). There are dozens of competing theories of justification. It’s sometimes easier to describe when a belief isn’t justified than when it is. In general, philosophers agree that a person isn’t justified if their belief is:

- a product of wishful thinking (I really wish you would love me so I believe you love me)

- a product of fear or guilt (you’re terrified of death and so form the belief in an afterlife)

- formed in the wrong way (you travel to an area you know nothing about, see a white spot 500 yards away and conclude it’s a sheep)

- a product of dumb luck or guesswork (you randomly form the belief that the next person you meet will have hazel eyes and it turns out that the next person you meet has hazel eyes)

Because beliefs come in all shapes and sizes and it’s hard to find a single theory of justification that can account for everything we would want to claim to know. You might be justified in believing that the sun is roughly 93 million miles from the earth much differently than you would be justified in believing God exists or that you have a minor back pain. Even so, justification is a critical element in any theory of knowledge and is the focus of many a philosophical thought.

People-centered Knowledge

You might notice that the description above puts the focus of knowing on the individual. Philosophers talk of individual persons being justified and not the ideas or concepts themselves being justified. This means that what may count as knowledge for you may not count as knowledge for me. Suppose you study economics and you learn principles in the field to some depth. Based on what you learn, you come to believe that psychological attitudes have just as much of a role to play in economic flourishing or deprivation as the political environment that creates economic policy. Suppose also that I have not studied economics all that much but I do know that I’d like more money in my pocket. You and I may have very different beliefs about economics and our beliefs might be justified in very different ways. What you know may not be something I know even though we have the same evidence and arguments in front of us.

So the subjective nature of knowledge partly is based on the idea that beliefs are things that individuals have and those beliefs are justified or not justified. When you think about it, that makes sense. You may have more evidence or different experiences than I have and so you may believe things I don’t or may have evidence for something that I don’t have. The bottom line is that “universal knowledge” – something everybody knows—may be very hard to come by. Truth, if it exists, isn’t like this. Truth is universal. It’s our access to it that may differ widely.

Rene Descartes and the Search for Universal Knowledge

A lot of people are uncomfortable with the idea that there isn’t universal knowledge. Philosopher Rene Descartes (pronounced day-cart) was one of them. When he was a young man, he was taught a bunch of stuff by his parents, teachers, priests and other authorities. As he came of age, he, like many of us, started to discover that much of what he was taught either was false or was highly questionable. At the very least, he found he couldn’t have the certainty that many of his educators had. While many of us get that, deal with it, and move on, Descartes was deeply troubled by this.

One day, he decided to tackle the problem. He hid himself away in a cabin and attempted to doubt everything of which he could not be certain. Since it wasn’t practical to doubt every belief he had, Descartes decided that it would be sufficient to subject the foundations of his belief system to doubt and the rest of the structure will “crumble of its own accord.” He first considers the things he came to believe by way of the five senses. For most of us these are pretty stable items but Descartes found that it was rather easy to doubt their truth. The biggest problem is that sometimes the senses can be deceptive. And after all, could he be certain he wasn’t insane or dreaming when he saw that book or tasted that honey? So while they might be fairly reliable, the senses don’t provide us with certainty—which is what Descartes was after.

Unfortunately, this left Descartes with no where to turn. He found that he could be skeptical about everything and was unable to find a certain foundation for knowledge. But then he hit upon something that changed modern epistemology. He discovered that there was one thing he couldn’t doubt: the fact that he was a thinking thing. In order to doubt it, he would have to think. He reasoned that it’s not possible to doubt something without thinking about the fact that you’re doubting. If he was thinking then he must be a thinking thing and so he found that it was impossible to doubt that he was a thinking being.

This seemingly small but significant truth led to his most famous contribution to Western thought: cogito ergo sum (I think, therefore I am). Some mistakenly think that Descartes was implying with this idea that he thinks himself into existence. But that wasn’t his point at all. He was making a claim about knowledge. Really what Descartes was saying is: I think, therefore I know that I am.

The story doesn’t end here for Descartes but for the rest of it, I refer you to the reading list below to dig deeper. The story of Descartes is meant to illustrate the depth of the problems of epistemology and how difficult and rare certainty is, if certainty is possible—there are plenty of philosophers who think either that Descartes’ project failed or that he created a whole new set of problems that are even more intractable than the one he set out to solve.

Postmodernism and Knowledge

Postmodern epistemology is a growing area of study and is relatively new on the scene compared with definitions that have come out of the analytic tradition in philosophy. Generally, though, it means taking a specific, skeptical attitude towards certainty, and a subjective view of belief and knowledge. Postmodernists see truth as much more fluid than classical (or modernist) epistemologists. Using the terms we learned above, they reject the idea that we can ever be fully justified in holding that our beliefs line up with the way the world actually is. We can’t know that we know.

Perspective at the Center

In order to have certainty, postmodernists claim, we would need to be able to “stand outside” our own beliefs and look at our beliefs and the world without any mental lenses or perspective . It’s similar to wondering what it would be like to watch ourselves meeting someone for the first time? We can’t do it. We can watch the event of the meeting on a video but the experience of meeting can only be had by us. We have that experience only from “inside” our minds and bodies. Since its not possible to stand outside our minds, all the parts that make up our minds influence our view on what is true. Our intellectual and social background, our biases, our moods, our genetics, other beliefs we have, our likes and dislikes, our passions (we can put all these under the label of our “cognitive structure”) all influence how we perceive what is true about the world. Further, say the postmodernists, it’s not possible to set aside these influences or lenses. We can reduce the intensity here and there and come to recognize biases and adjust for them for sure. But it’s not possible to completely shed all our lenses which color our view of things and so it’s not possible to be certain that we’re getting at some truth “out there.”

Many have called out what seems to be a problem with the postmodernist approach. Notice that as soon as a postmodernist makes a claim about the truth and knowledge they seem to be making a truth statement! If all beliefs are seen through a lens, how do we know the postmodernists beliefs are “correct?” That’s a good question and the postmodernist might respond by saying, “We don’t!” But then, why believe it? Because of this obvious problem, many postmodernists attempt to simply live with postmodernist “attitudes” towards epistemology and avoid saying that they’re making claims that would fit into traditional categories. We have to change our perspective to understand the claims.

Community Agreement

To be sure, Postmodernists do tend to act like the rest of us when it comes to interacting with the world. They drive cars, fly in airplanes, make computer programs, and write books. But how is this possible if they take such a fluid view of knowledge? Postmodernists don’t eschew truth in general. They reject the idea that any one person’s beliefs about it can be certain. Rather, they claim that truth emerges through community agreement. Suppose scientists are attempting to determine whether the planet is warming and that humans are the cause. This is a complex question and a postmodernist might say that if the majority of scientists agree that the earth is warming and that humans are the cause, then that’s true. Notice that the criteria for “truth” is that scientists agree . To use the taxonomy above, this would be the “justification condition.” So we might say that postmodernists accept the first and third conditions of the tripartite view but reject the second condition: the idea that there is a truth that beliefs need to align to a truth outside our minds.

When you think about it, a lot of what we would call “facts” are determined in just this way. For many years, scientists believed in a substance called “phlogiston.” Phlogiston was stuff that existed in certain substances (like wood and metal) and when those substances were burned, more phlogiston was added to the substance. Phlogiston was believed to have negative weight, that’s why things got lighter when they burned. That theory has since been rejected and replace by more sophisticated views involving oxygen and oxidation.

So, was the phlogiston theory true? The modernist would claim it wasn’t because it has since been shown to be false. It’s false now and was false then even though scientists believed it was true. Beliefs about phlogiston didn’t line up with the way the world really is, so it was false. But the postmodernist might say that phlogiston theory was true for the scientists that believed it. We now have other theories that are true. But phlogiston theory was no less true then than oxygen theory is now. Further, they might add, how do we know that oxygen theory is really the truth ? Oxygen theory might be supplanted some day as well but that doesn’t make it any less true today.

Knowledge and the Mental Life

As you might expect, philosophers are not the only ones interested in how knowledge works. Psychologists, social scientists, cognitive scientists and neuroscientists have been interested in this topic as well and, with the growth of the field of artificial intelligence, even computer scientists have gotten into the game. In this section, we’ll look at how work being done in psychology and behavioral science can inform our understanding of how human knowing works.

Thus far, we’ve looked at the structure of knowledge once beliefs are formed. Many thinkers are interested how belief formation itself is involved our perception of what we think we know. Put another way, we may form a belief that something is true but the way our minds formed that belief has a big impact on why we think we know it. The science is uncovering that, in many cases, the process of forming the belief went wrong somewhere and our minds have actually tricked us into believing its true. These mental tricks may be based on good evolutionary principles: they are (or at least were at some point in our past) conducive to survival. But we may not be aware of this trickery and be entirely convinced that we formed the belief in the right way and so have knowledge. The broad term used for this phenomenon is “cognitive bias” and mental biases have a significant influence over how we form beliefs and our perception of the beliefs we form. 1

Wired for Bias

A cognitive bias is a typically unconscious “mental trick” our minds play that lead us to form beliefs that may be false or that are directed towards some facts and leaving out others such that these beliefs align to other things we believe, promote mental safety, or provide grounds for justifying sticking to to a set of goals that we want to achieve. Put more simply, mental biases cause us to form false beliefs about ourselves and the world. The fact that our minds do this is not necessarily intentional or malevolent and, in many cases, the outcomes of these false beliefs can be positive for the person that holds them. But epistemologists (and ethicists) argue that ends don’t always justify the means when it comes to belief formation. As a general rule, we want to form true beliefs in the “right” way.

Ernest Becker in his important Pulitzer Prize winning book The Denial of Death attempts to get at the psychology behind why we form the beliefs we do. He also explores why we may be closed off to alternative viewpoints and why we tend to become apologists (defenders) of the viewpoints we hold. One of his arguments is that we as humans build an ego ( in the Freudian sense; what he calls “character armor”) out of the beliefs we hold and those beliefs tend to give us meaning and they are strengthened when more people hold the same viewpoint. In a particularly searing passage, he writes:

Each person thinks that he has the formula for triumphing over life’s limitations and knows with authority what it means to be a man [N.B. by ‘man’ Becker means ‘human’ and uses masculine pronouns as that was common practice when he wrote the book], and he usually tries to win a following for his particular patent. Today we know that people try so hard to win converts for their point of view because it is more than merely an outlook on life: it is an immortality formula. . . in matters of immortality everyone has the same self-righteous conviction. The thing seems perverse because each diametrically opposed view is put forth with the same maddening certainty; and authorities who are equally unimpeachable hold opposite views! (Becker, Ernest. The Denial of Death, pp. 255-256. Free Press.)

In other words, being convinced that our viewpoint is correct and winning converts to that viewpoint is how we establish ourselves as persons of meaning and significance and this inclination is deeply engrained in our psychological equipment. This not only is why biases are so prevalent but why they’re difficult to detect. We are, argues Becker and others, wired towards bias. Jonathan Haidt agrees and go so far as to say that reason and logic is not only the cure but a core part of the wiring that causes the phenomenon.

Anyone who values truth should stop worshipping reason. We all need to take a cold hard look at the evidence and see reasoning for what it is. The French cognitive scientists Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber recently reviewed the vast research literature on motivated reasoning (in social psychology) and on the biases and errors of reasoning (in cognitive psychology). They concluded that most of the bizarre and depressing research findings make perfect sense once you see reasoning as having evolved not to help us find truth but to help us engage in arguments, persuasion, and manipulation in the context of discussions with other people. (Haidt, Jonathan. The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion (p. 104). Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.)

Biases and Belief Formation

Research in social science and psychology are uncovering myriad ways in which our minds play these mental tricks. For example, Daniel Kahneman discusses the impact emotional priming has on the formation of a subsequent idea. In one study, when participants were asked about happiness as it related to their romantic experiences, those that had a lot of dates in the past would report that they were happy about their life while those that had no dates reported being lonely, isolated, and rejected. But then when they subsequently were asked about their happiness in general, they imposed the context of their dating happiness to their happiness in general regardless of how good or bad the rest of their lives seemed to be going. If a person would have rated their overall happiness as “very happy” when asked questions about general happiness only, they might rate their overall happiness as “somewhat happy” if they were asked questions about their romantic happiness just prior and their romantic happiness was more negative than positive.

This type of priming can significantly impact how we view what is true. Being asked if we need more gun control or whether we should regulate fatty foods will change right after a local shooting right or after someone suffers a heart scare. The same situation will have two different responses by the same person depending on whether he or she was primed or not. Jonathan Haidt relates similar examples.

Psychologists now have file cabinets full of findings on ‘motivated reasoning,’ showing the many tricks people use to reach the conclusions they want to reach. When subjects are told that an intelligence test gave them a low score, they choose to read articles criticizing (rather than supporting) the validity of IQ tests. When people read a (fictitious) scientific study that reports a link between caffeine consumption and breast cancer, women who are heavy coffee drinkers find more flaws in the study than do men and less caffeinated women. (Haidt, p. 98)

There are many other biases that influence our thinking. When we ask the question, “what is knowledge?” this research has to be a part of how we answer the question. Biases and their influence would fall under the broad category of the justification condition we looked at earlier and the research should inform how we view how beliefs are justified. Justification is not merely the application of a philosophical formula. There are a host of psychological and social influences that are play when we seek to justify a belief and turn it into knowledge. 2 We can also see how this research lends credence to the philosophical position of postmodernists. At the very least, even if we hold that we can get past our biases and get “more nearer to the truth,” we at least have good reason to be careful about the things we assert as true and adopt a tentative stance towards the truth of our beliefs.

In a day when “fake news” is a big concern and the amount of information for which we’re responsible grows each day, how we justify the beliefs we hold becomes a even more important enterprise. I’ll use a final quote from Haidt to conclude this section:

And now that we all have access to search engines on our cell phones, we can call up a team of supportive scientists for almost any conclusion twenty-four hours a day. Whatever you want to believe about the causes of global warming or whether a fetus can feel pain, just Google your belief. You’ll find partisan websites summarizing and sometimes distorting relevant scientific studies. Science is a smorgasbord, and Google will guide you to the study that’s right for you. (Haidt, pp. 99-100)

Making Knowledge Practical

Well most of us aren’t like Descartes. We actually have lives and don’t want to spend time trying to figure out if we’re the cruel joke of some clandestine mad scientist. But we actually do actually care about this topic whether we “know” it or not. A bit of reflection exposes just how important having a solid view of knowledge actually is and spending some focused time thinking more deeply about knowledge can actually help us get better at knowing.

Really, knowledge is a the root of many (dare I say most) challenges we face in a given day. Once you get past basic survival (though even things as basic as finding enough food and shelter involves challenges related to knowledge), we’re confronted with knowledge issues on almost every front. Knowledge questions range from larger, more weighty questions like figuring out who our real friends are, what to do with our career, or how to spend our time, what politician to vote for, how to spend or invest our money, or should we be religious or not, to more mundane ones like which gear to buy for our hobby, how to solve a dispute between the kids, where to go for dinner, or which book to read in your free time. We make knowledge decisions all day, every day and some of those decisions deeply impact our lives and the lives of those around us.

So all these decisions we make about factors that effect the way we and others live are grounded in our view of knowledge—our epistemology . Unfortunately few spend enough time thinking about the root of their decisions and many make knowledge choices based on how they were raised (my mom always voted Republican so I will), what’s easiest (if I don’t believe in God, I’ll be shunned by my friends and family), or just good, old fashioned laziness. But of all the things to spend time on, it seems thinking about how we come to know things should be at the top of the list given the central role it plays in just about everything we do.

Updated January, 2018: Removed dated material and general clean up; added section on cognitive biases. Updated March, 2014: Removed reference to dated events; removed section on thought experiment; added section on Postmodernism; minor formatting changes

- While many thinkers have written on cognitive biases in one form or another, Jonathan Haidt in his book The Righteous Mind and Daniel Kahneman in his book Thinking Fast and Slow have done seminal work to systemize and provide hard data around how the mind operates when it comes to belief formation and biases. There is much more work to be done for sure but these books, part philosophy, part psychology, part social science, provide the foundation for further study in this area. The field of study already is large and growing so I can only provide a thumbnail sketch of the influence of how belief formation is influenced by our mind and other factors. I refer the reader to the source material on this topic for further study (see reading list below). ↩

- For a strategy on how we can adjust for these natural biases that our minds seem wired to create, see the Philosophy News article, “ How to Argue With People ”. I also recommend Carol Dweck’s excellent book Mindset . ↩

For Further Reading

- Epistemology: Classic Problems and Contemporary Responses (Elements of Philosophy) by Laurence BonJour. One of the better introductions to the theory of knowledge. Written at the college level, this book should be accessible for most readers but have a good philosophical dictionary on hand.

- Belief, Justification, and Knowledge: An Introduction to Epistemology (Wadsworth Basic Issues in Philosophy Series) by Robert Audi. This book has been used as a text book in college courses on epistemology so may be a bit out of range for the general reader. However, it gives a good overview of many of the issues in the theory of knowledge and is a fine primer for anyone interested in the subject.

- The Theory of Knowledge: Classic and Contemporary Readings by Louis Pojman. Still one of the best books for primary source material. The edited articles have helpful introductions and Pojman covers a range of sources so the reader will get a good overview from many sides of the question. Written mainly as a textbook.

- The Stuff of Thought: Language as a Window into Human Nature   by Steven Pinker. While not strictly a book about knowledge per se, Pinker’s book is fun, accessible, and a good resource for getting an overview of some contemporary work being done mainly in the hard sciences.

- The Selections From the Principles of Philosophy by René Descartes . A good place to start to hear from Descartes himself.

- Descartes’ Bones: A Skeletal History of the Conflict between Faith and Reason by Russell Shorto. This book is written as a history so it’s not strictly a philosophy tome. However, it gives the general reader some insight into what Descartes and his contemporaries were dealing with and is a fun read.

- On Bullshit by Harry Frankfurt. One get’s the sense that Frankfurt was being a bit tongue-in-cheek with the small, engaging tract. It’s more of a commentary on the social aspect of epistemology and worth reading for that reason alone. Makes a great gift!

- On Truth by Harry Frankfurt. Like On Bullshit but on truth.

- A Rulebook for Arguments by Anthony Weston. A handy reference for constructing logical arguments. This is a fine little book to have on your shelf regardless of what you do for a living.

- Warrant: The Current Debate   by Alvin Plantinga. Now over 25 years old, “current” in the title may seem anachronistic. Still, many of the issues Plantinga deals with are with us today and his narrative is sure to enlighten and prime the pump for further study.

- Thinking Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman. The book to begin a study on cognitive biases.

- The Righteous Mind by Jonathan Haidt. A solid book that dabbles in cognitive biases but also in why people form and hold beliefs and how to start a conversation about them.

- The Denial of Death by Ernest Becker. A neo (or is it post?) Freudian analysis of why we do what we do. Essential reading for better understanding why we form the beliefs we do.

- Mindset: The New Psychology of Success by Carol S. Dweck. The title reads like a self-help book but the content is actually solid and helpful for developing an approach to forming and sharing ideas.

More articles

What is Disagreement? – Part IV

This is Part 4 of a 4-part series on the academic, and specifically philosophical study of disagreement. In Part 1...

What is Disagreement? – Part III

This is Part 3 of a 4-part series on the academic, and specifically philosophical study of disagreement. In Part 1...

What is Disagreement? – Part II

This is Part 2 of a 4-part series on the academic, and specifically philosophical study of disagreement. In Part 1...

What is Disagreement?

This is Part 1 of a 4-part series on the academic, and specifically philosophical study of disagreement. In this series...

The Lords and Limits of Tolkienism

On December 19, 2001, The Fellowship of the Ring opened in US theaters. Like Episode IV: A New Hope, the...

philosophybits: “Men, in general, seem to employ their reason to justify prejudices… rather than to…

philosophybits: “Men, in general, seem to employ their reason to justify prejudices… rather than to root them out.” — Mary...

philosophybits: “A minister of state is excusable for the harm he does when the helm of government…

philosophybits: “A minister of state is excusable for the harm he does when the helm of government has forced his...

“The mechanism for reproducing life, for dominating and for destroying it, is exactly the same, and…”

“The mechanism for reproducing life, for dominating and for destroying it, is exactly the same, and accordingly industry, state and...

1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

Philosophy, One Thousand Words at a Time

Epistemology, or Theory of Knowledge

Thomas Metcalf Category: Epistemology Word count: 999

Listen here

Many people think that they have a lot of knowledge. They also believe that other people sometimes know what they claim to know. But what is knowledge anyway? And how do we come to have it? Is it important that we have knowledge? If so, why?

The branch of philosophy that attempts to answer these and related questions is known as ‘epistemology’ or ‘theory of knowledge.’ [1]

1. What is Knowledge? [2]

One historically popular definition of ‘knowledge’ is the ‘JTB’ theory of knowledge: knowledge is j ustified, t rue b elief. [3] Most philosophers think that a belief must be true in order to count as knowledge. [4] Suppose that Smith is framed for a crime, and the evidence against Smith is overwhelming. But Smith is innocent. Does the jury know that Smith committed the crime ? No, because knowledge requires truth; the jury believed it, but they didn’t know it. [5]

Also, most philosophers think that the belief must be justified . We don’t normally consider a lucky guess to be knowledge. (If you flip a coin but don’t look at the result yet, and just find yourself believing that it’s Heads, and in fact it is Heads, we don’t think you knew that it was Heads.) Yet there is substantial debate about what justification is.

2. Analysis of Justification

What would be required to transform the lucky guess that the coin came up Heads into knowledge ? One standard answer is ‘justification.’ [6]

Intuitively, you would have to acquire good reason to believe that the coin came up Heads: for example, you look at the coin. [7] In general, theories of justification either say that the factors that justify your belief must be available within your own first-person, conscious experience, or that they don’t need to be. We call the former theories ‘internalist’ and the latter ‘externalist.’ [8]

For example, some internalists are evidentialists : roughly, they say that your justification depends on the evidence you have, for example the awareness of the image of a president’s head on a coin. And some externalists are reliabilists : roughly, they say that whether you are justified depends on whether your belief was formed by a reliable belief-forming mechanism, for example, the physical process of vision. For evidentialists, the evidence you have seems “internal” to your first-person awareness: it’s what you’re aware of. And whether the process that formed your belief is reliable seems “external” to your first-person awareness: you might not even have any beliefs about photons and how they work.

3. Sources of Knowledge and Evidence

We’ve thought about what it means to have justified beliefs. [9] But when our beliefs are in fact justified, what is the source or explanation of that justification?

Surely we get some justification from empirical observation : using our five senses, the tools of science, and introspection (looking inside your own mind, for example learning that you believe that 2+2=4). [10] This justification is ‘ a posteriori ’ or ‘empirical,’ for example, looking at the coin-toss result.

Maybe there is some knowledge that we acquire through intuition, definitions, or some other putative non -empirical evidence. We call this ‘ a priori ’ knowledge or justification: justified but independently of any particular empirical observation or awareness of the evidence or justification required. [11] I seem to know, just by thinking about it, that there can be no coins that are both square and circular; I don’t need to consult scientists. [12]

Roughly speaking, rationalists (about justification) believe that we have important, valuable a priori knowledge about the world, knowledge that’s not merely about the meanings of our words or concepts. Empiricists , in contrast, believe that all of our important knowledge of the world is empirical. [13]

Beyond this, feminist epistemologists have argued that one’s knowledge, and whether one is taken seriously as a knower, can depend on one’s particular social position, including one’s gender. [14] To the traditional list of sources of knowledge, we might add one’s standpoint and situation, and also add emotion. [15]

4. The Structure of Knowledge, Justification, and Inference

Normally, we think we can infer new beliefs from our existing beliefs: we believe some propositions, and on the basis of those beliefs, conclude that some other propositions are true.

If someone asks you to justify a belief, you’re likely to cite other beliefs you have. I know that Antarctica exists because I believe that maps are generally trustworthy and that maps claim that Antarctica exists. But can this regress of inference go on forever? [16]

One popular position is foundationalism . Foundationalists say that the regress stops at justified beliefs and, since the regress has stopped, those beliefs aren’t justified by any inference from any other belief. [17]

Another popular position is coherentism , according to which one’s beliefs are justified by being part of a web or network of coherent beliefs. [18]

We think a set of inferences can give us justified beliefs. But it’s possible to acquire false or unjustified beliefs, which wouldn’t be knowledge after all.

5. Skepticism

In general, skeptics deny that we have some item of knowledge. There are skeptics about whether we have:

- knowledge of the external world, i.e., the world beyond the contents of our conscious experiences; [19]

- moral knowledge; [20]

- religious knowledge; [21]

- knowledge from memory or knowledge of the past; [22]

- knowledge from induction; [23]

- scientific knowledge; [24] and

- knowledge of other minds. [25]

And some philosophers have endorsed global skepticism, according to which we have no knowledge or no justified beliefs at all. [26]

6. Other Issues

Epistemology is a broad field. Other issues include:

- the nature of perception; [27]

- the nature of understanding; [28]

- whether we should trust our peers when they disagree with us; [29]

- the relationships between epistemology, trust, and justice; [30]

- how different reasons for belief (not just epistemic reasons) should affect us or determine whether we have knowledge; [31]

- what value there is, if any, in having knowledge, especially in contrast to mere true belief; [32]

- whether ‘knowledge’ means the same thing in all contexts. [33]

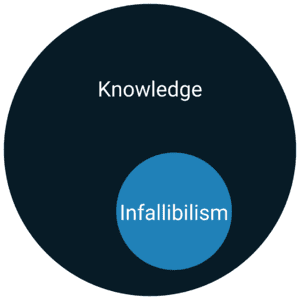

- whether knowledge requires certainty; [34]

- whether philosophy should be continuous with, or even replaced by, science. [35]

And many more. [36]

7. Conclusion

Some philosophers believe that epistemology is “first philosophy,” fundamental to the rest of philosophy and inquiry, since all areas of study and learning seek understanding, justified beliefs, and knowledge. If they are correct, an understanding of at least the basics of epistemology is important for all thinking people. [37]

[1] In constructing this overview, I roughly follow online encyclopedias such as in Steup 2019 and Truncellito 2019 and textbooks such as BonJour 2002, Huemer 2002, and Steup and Sosa 2005. ‘Epistemology’ comes from Greek roots meaning the study of, or discourse about, knowledge.

[2] Here, we are talking about what’s sometimes called ‘propositional’ knowledge or ‘knowledge-that.’ But there are other mental facts about you that may count as your having knowledge. Someone might know how to ride a bicycle, or know what it’s lik e to taste lemon. These aren’t obviously propositional knowledge, but they are natural enough ways of using the term ‘knowledge.’

[3] Gettier (1963) attributes this conception or something very much like it to Plato ( Theaetetus 20 I; Meno 98), Chisholm (1957: 16), and Ayer (1956). BonJour (2002: 27) attributes a similar conception to Descartes. Yet as Gettier argues, there may be examples of justified, true beliefs that don’t count as ‘knowledge.’ Suppose that your computer has an error and its internal clock is stuck at 11:49 am. It stays this way all morning and you don’t notice. Then you happen to wonder what time it is, look at your computer’s clock, and see ‘11:49 am.’ Suppose, however, that the time actually just happens to be 11:49 am right when you look at the clock. Your belief that it is 11:49 am might be justified (because you have no reason yet to doubt your computer’s clock), and true (because you happened to check the clock right at 11:49 am), but many would say it doesn’t count as ‘knowledge.’ Therefore, perhaps there is some fourth property that a belief must have to count as knowledge. For more, see Zagzebski 1994 and Chapman 2014 (“ The Gettier Problem ” in 1000-Word Philosophy ).

[4] Sometimes a person might say, ‘I just knew I wasn’t going to get that job–but I did!’ But arguably, that use of ‘knew’ is intended to emphasize the person’s certainty, not to say that they really knew something false. But see Hazlett 2010 which argues that knowledge doesn’t require truth.

[5] And see n. 4.

[6] For an introduction to the concept of epistemic justification, see Epistemic Justification: What is Rational Belief? by Todd R. Long. Although the term of art for ‘whatever has to be added to true belief to create knowledge’ is ‘warrant.’ Cf. Plantinga 1993. Perhaps Gettier (1963) showed that warrant isn’t merely justification.

[7] See e.g. BonJour 2004: 5 on what epistemic justification is. Philosophers have described justification as occurring when a belief is likely to be true, or when a person who wants to have true beliefs ought to believe that belief, or when one has good reason to believe the belief, or when the belief is best-supported by the evidence. This question is actually fairly complex, however, because some (e.g. possibly Foley 1987: ch. 1; but see Kelly 2003 for critique) believe that epistemic justification is just a species of prudential or instrumental justification.

[8] I generally follow Pappas 2019; refer there for more information. In more detail: an internalist might say (as ‘accessibilists’ say) that justification depends on what you are aware of from the first-person perspective, or (as ‘mentalists’ say) on the current content of your mental states, or (as ‘evidentialists’ say) on the evidence available to you. Externalists might say (as ‘reliabilists’ say) that justification depends on one’s belief’s having been formed by a reliable belief-forming mechanism, or (as ‘proper functionalists’ say) by the proper functioning of your cognitive apparatus. Most generally, evidentialism, accessibilism, mentalism, and deontology are usually thought of as ‘internalist’ theories of epistemic justification, since they say your justification depends on factors internal to your mind or first-person awareness. And reliabilism, proper-functionalism, and virtue epistemology are normally thought of as ‘externalist’ theories of epistemic justification, since whether a belief was reliably formed, for example, may depend on factors you have no first-person access to. See e.g. Fumerton 1995 and BonJour and Sosa 2003, as well as Pappas 2019. One might also take the position that internalists and externalists are simply describing two different phenomena, both philosophically important, that are sometimes both referred to as ‘justification; cf. BonJour 2002: 233-7 and Pasnau 2013: 1008 ff. For more about specific internalist and externalist theories, see Conee and Feldman 2004 for evidentialism; Chisholm 1977: 17 for accessibilism; Conee and Feldman 2001 for mentalism; Alston 1989: 115-52 for deontology; Goldman 1979 for reliabilism; Plantinga 1993: 41 ff. and Bergmann 2006: ch. 5 for proper-functionalism; and Turri et al. 2019 for an introduction to virtue epistemology.

[9] One more note: There could be justified, false beliefs. For example, someone might do a really great job of framing you for a crime you didn’t commit, and so people would be justified in believing that you committed the crime, yet you really are innocent and so their justified belief is false. Such beliefs are part of the standard presentation of Gettier (1963) cases. Of course, a few philosophers have questioned whether justified or warranted false beliefs are possible (Sturgeon 1993; Merricks 1995).

[10] See for example Steup 2019: § 4.2. I assume that introspection is fundamentally empirical, at least in the sense necessary to make the a priori -empirical distinction most illuminating (BonJour 1998: 7).

[11] But not normally independent of any empirical observation at all. For example, we might need empirical observation to acquire the relevant concept in the first place. See e.g. BonJour 1998: 9.

[12] Perhaps moral knowledge, if it exists, is also a priori (cf. Huemer 2005). It’s difficult to imagine seeing, with my eyes , that stealing is wrong.

[13] Some famous rationalists include Plato, Descartes, and Leibniz; some famous empiricists include Locke, Berkeley, and Hume. Yet these categorizations aren’t 100% neat; for example, Locke and Berkeley are normally counted among the empiricists, but they may have made some limited room for a priori knowledge as well. See Markie 2019: § 1.2. Also, strictly speaking, when I talk about these different types of sentences, what I’m referring to is the distinction between analytic sentences ( very roughly, sentences that are true by definition, e.g. ‘all red squares are red’) and synthetic sentences (sentences that are not merely true by definition, e.g. ‘all red squares are somewhere on Earth’), such that rationalists believe in the synthetic a priori and empiricists don’t. For a general introduction to this debate, see Markie 2019.

[14] See Anderson 2020 for an overview.

[15] Jaggar 1988.

[16] Infinitists (e.g. Klein 1998) say that the regress goes back forever, but that our beliefs can still be justified.

[17] One of the most-important historical presentations of foundationalism is in Descartes (cf. Newman 2019: § 2.1). More-recent defenders include Pryor (2000) and Huemer (2001). Foundationalists face the challenge of explaining what could justify a belief other than an inference from some other belief. One answer that has received much attention recently is to appeal to some principle of conservatism; see e.g. Huemer 2001. Perhaps, for example, if it appears to you as if something is true, that appearance is enough to justify the belief.

[18] To say that these beliefs are coherent might mean, for example, that they are all logically consistent and mutually supporting. Thus for coherentists, in some sense, the regress of inference “circles back” on itself. Influential coherentists include Lewis (1946); Quine and Ullian (1970) and the early BonJour (1985). A more recent example is Poston (2014). Coherentists face their own challenges, for example, why there needs to be any “input” from outside one’s own mind (cf. BonJour 1985: ch. 6) in order to have a set of justified beliefs. Why isn’t mere coherence with the rest of one’s beliefs enough?

[19] See e.g. Descartes 1984 [1641]: 13.

[20] Sinnott-Armstrong 2020.

[21] Forrest 2020.

[22] Cf. Russell 2019 [1921]: 71-84.

[23] Hume 1896 [1739-40]: bk. I, part III, § VI.

[24] See e.g. Chakravartty 2019 for an overview of scientific realism and anti-realism.

[25] Mill 1872: 243; Duddington 1919; Ayer 1953.

[26] Comesaña and Klein 2019: § 5.

[27] See e.g. Berkeley 1904 [1710]; Austin 1962; and Lyons 2019 for an overview.

[28] Gordon n.d.

[29] See e.g. Frances and Matheson 2019: § 5.

[30] Fricker 2007; Alcoff 2010.

[31] See e.g. Stanley 2005.

[32] Prichard et al. 2019.

[33] See e.g. Cohen 1986; DeRose 1992.

[34] Butchvarov 1970.

[35] Quine 1969; Kornblith 2002.

[36] For excellent overviews, see Steup 2019; Truncellito 2019; Steup, Turri, and Sosa 2013; BonJour 2002; and Huemer 2002.

[37] Perhaps in order to know whether one has acquired any knowledge, one must know what knowledge is and how we achieve it. This is the basis of Descartes’s 1984 [1641] strategy.

Alcoff, Linda Martín. 2010. “Epistemic Identities.” Episteme 7(2): 128-37.

Alston, William. 1989. Epistemic Justification: Essays in the Theory of Knowledge . Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Anderson, Elizabeth. 2020. “Feminist Epistemology and Philosophy of Science.” In E. N. Zalta (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Summer 2020 Edition.

Austin 1962. Sense and Sensibilia . Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Ayer, A. J. 1953. “One’s Knowledge of Other Minds.” Theoria 19(1-2): 1-20.

Ayer, A. J. 1956. The Problem of Knowledge . London, UK: Macmillan.

Bergmann, Michael. 2006. Justification Without Awareness . New York, NY and Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Berkeley, George. 1904 [1710]. A Treatise Concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge . Chicago, IL: Open Court.

BonJour, Laurence. 1985. The Structure of Empirical Knowledge . Cambridge, MA and London, UK: Harvard University Press.

BonJour, Laurence. 1998. In Defense of Pure Reason: A Rationalist Account of A Priori Justification . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

BonJour, Laurence. 2002. Epistemology: Classic Problems and Contemporary Responses . Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

BonJour, Laurence. 2003. “A Version of Internalist Foundationalism.” In BonJour, Laurence and Ernest Sosa. Epistemic Justification: Internalism vs. Externalism, Foundations vs. Virtues . Malden, MA: Blackwell.

BonJour, Laurence and Ernest Sosa. 2003. Epistemic Justification: Internalism vs. Externalism, Foundations vs. Virtues . Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Butchvarov, Panayot. 1970. The Concept of Knowledge . Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

Chakrvavartty, Anjan. 2019. “Scientific Realism.” In E. N. Zalta (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Winter 2019 Edition .

Chisholm, Roderick M. 1957. Perceiving: A Philosophical Study (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press).

Chisholm, Roderick M. 1977. Theory of Knowledge , second edition. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Cohen, Stewart. 1986. “Knowledge and Context.” The Journal of Philosophy 83(10): 574-83.

Comesaña, Juan and Peter Klein. “Skepticism.” In E. N. Zalta (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Winter 2019 Edition .

Conee, Earl and Richard Feldman. 2001. “Internalism Defended.” American Philosophical Quarterly 38(1): 1-18.

Conee, Earl and Richard Feldman. 2004. Evidentialism: Essays in Epistemology . New York, NY and Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

DeRose, Keith. 1992. “Contextualism and Knowledge Attributions.” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 52(4): 913-29.

Descartes, René. 1984 [1641]. “Meditations on First Philosophy.” In John Cottingham, Robert Stoothoff, and Dugald Murdoch (tr. and ed.), The Philosophical Writings of Descartes, Volume II (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press), pp. 1-6.

Duddington, Nathalie A. 1919. “Our Knowledge of Other Minds.” Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 19: 147-78.

Foley, Richard. 1987. The Theory of Epistemic Rationality. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Forrest, Peter. 2020. “The Epistemology of Religion.” In E. N. Zalta (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Summer 2020 Edition .

Frances, Bryan and Jonathan Matheson. 2019. “Disagreement.” In E. N. Zalta (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Winter 2019 Edition .

Fricker, Miranda. 2007. Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing . New York, NY and Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Fumerton, Richard. 1995. Metaepistemology and Skepticism . Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Gettier, Edmund. 1963. “Is Justified True Belief Knowledge?” Analysis 23(6): 121-23.

Goldman, Alvin I. 1979. “What is Justified Belief?” In G. S. Pappas (ed.), Justification and Knowledge (Dordrecht, Holland: D. Reidel), pp. 1-23.

Gordon, Emma C. N.d. “Understanding in Epistemology.” In The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy ,

Hazlett, Allan. 2010. “The Myth of Factive Verbs.” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 80(3): 497-522.

Huemer, Michael. 2001. Skepticism and the Veil of Perception . Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Huemer, Michael. 2005. Ethical Intuitionism . Houndmills, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hume, David. 1896 [1739-40]. A Treatise of Human Nature . Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Jaggar, Alison. 1988. “Love and Knowledge: Emotion in Feminist Epistemology.” Inquiry 32(2): 151-76.

Kelly, Thomas. 2003. “Epistemic Rationality as Instrumental Rationality: A Critique.” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research LXVI(3): 612-40.

Klein, Peter. 1998. “Foundationalism and the Infinite Regress of Reasons.” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 58(4): 919-26.

Kornblith, Hilary. 2002. Knowledge and Its Place in Nature . New York, NY and Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Lewis, Clarence Irving. 1946. An Analysis of Knowledge and Valuation . La Salle, IL: The Open Court Publishing Company.

Lyons, Jack. 2019. “Epistemological Problems of Perception.” In E. N. Zalta (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Winter 2019 Edition .

Markie, Peter. 2019. “Rationalism vs. Empiricism.” In E. N. Zalta (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Winter 2019 Edition .

Merricks, Trenton. 1995. “Warrant Entails Truth.” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 55(4): 841-55.

Mill, John Stuart. 1872. An Examination of Sir William Hamilton’s Philosophy , fourth edition. London, UK: Longman, Green, Reader, and Dyer.

Newman, Lex. 2019. “Descartes’ Epistemology.” In E. N. Zalta (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Winter 2019 Edition .

Pappas, George. 2019. “Internalist vs. Externalist Conceptions of Justification.” In E. N. Zalta (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy , Winter 2019 Edition.

Pasnau, Robert. 2013. “Epistemology Idealized.” Mind 122(488): 987-1021.

Plantinga, Alvin. 1993. Warrant and Proper Function . New York, NY and Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Poston, Ted. 2014. Reason and Explanation: A Defense of Explanatory Coherentism . New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Prichard, Dunan et al. 2019. “The Value of Knowledge.” In E. N. Zalta (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Winter 2019 Edition.

Pryor, James. 2000. “The Skeptic and the Dogmatist.” Noûs 34(4): 517-49.

Quine, W. V. O. 1969. “Epistemology Naturalized.” In W. V. O. Quine, Ontological Relativity and Other Essays (New York, NY: Columbia University Press), pp. 69-90.

Quine, W.V.O. 1951. “Two Dogmas of Empiricism.” Philosophical Review 60(1): 20-43.

Quine, W.V.O. and J.S. Ullian. 1970. The Web of Belief . New York, NY: Random House.

Rey, Georges. 2019. “The Analytic/Synthetic Distinction.” In E. N. Zalta (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Winter 2019 Edition .

Russell, Bertrand. 2019 [1921]. The Analysis of Mind . Whithorn, UK: Anodos Books.

Sinnott-Armstrong, Walter. 2020. “Moral Skepticism.” In E. N. Zalta (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Summer 2020 Edition .

Stanley, Jason. 2005. Knowledge and Practical Interests . New York, NY and Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Steup, Matthias. 2019. “Epistemology.” In E. N. Zalta (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Winter 2019 Edition .

Steup, Matthias, John Turri, and Ernest Sosa (eds.). 2013. Contemporary Debates in Epistemology, Second Edition . Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Sturgeon, Scott. 1993. “The Gettier Problem.” Analysis 53(3): 156-64.

Turri, John, Mark Alfano, and John Greco. 2019. “Virtue Epistemology.” In E. N. Zalta (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy , Winter 2019 Edition.

Zagzebski, Linda. 1994. “The Inescapability of Gettier Problems.” The Philosophical Quarterly 44(174): 65-73.

Related Essays

Epistemic Justification: What is Rational Belief? by Todd R. Long

Seemings: Justifying Beliefs Based on How Things Seem by Kaj André Zeller

The Gettier Problem & the Definition of Knowledge by Andrew Chapman

External World Skepticism by Andrew Chapman

Is it Wrong to Believe Without Sufficient Evidence? W.K. Clifford’s “The Ethics of Belief” by Spencer Case

Descartes’ “I think, therefore I am” by Charles Miceli

Descartes’ Meditations 1-3 and Descartes’ Meditations 4-6 by Marc Bobro

Moral Testimony by Annaleigh Curtis

Take My Word for It: On Testimony by Spencer Case

Conspiracy Theories by Jared Millson

Modal Epistemology: Knowledge of Possibility and Necessity by Bob Fischer

“Properly Basic” Belief in God: Believing in God without an Argument by Jamie B. Turner

The Problem of Induction by Kenneth Blake Vernon

The Epistemology of Disagreement by Jonathan Matheson

Expertise by Jamie Carlin

Epistemic Injustice by Huzeyfe Demirtas

Idealism Pt. 1 and Idealism Pt. 2 by Addison Ellis

PDF Download

Download this essay in PDF.

About the Author

Tom Metcalf is an associate professor at Spring Hill College in Mobile, AL. He received his PhD in philosophy from the University of Colorado, Boulder. He specializes in ethics, metaethics, epistemology, and the philosophy of religion. Tom has two cats whose names are Hesperus and Phosphorus. shc.academia.edu/ThomasMetcalf

Follow 1000-Word Philosophy on Facebook and Twitter and subscribe to receive email notifications of new essays at 1000WordPhilosophy.com

Share this:

31 thoughts on “ epistemology, or theory of knowledge ”.

- Pingback: Seemings: Justifying Beliefs Based on How Things Seem – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Epistemic Injustice – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Philosophy of Color – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Philosophy of Mysticism: Do Mystical Experiences Justify Religious Beliefs? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: “Properly Basic” Belief in God: Believing in God without an Argument – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Expertise: What is an Expert? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: The Probability Calculus – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Bayesianism – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Self-Knowledge: Knowing Your Own Mind – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Moore’s Proof of an External World: Responding to External World Skepticism – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: al-Ghazālī’s Dream Argument for Skepticism – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: External World Skepticism – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Arguments: Why Do You Believe What You Believe? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: The Gettier Problem & the Definition of Knowledge – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Epistemic Justification: What is Rational Belief? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Philosophy of Law: An Overview – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Is it Wrong to Believe Without Sufficient Evidence? W.K. Clifford’s “The Ethics of Belief” – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Indoctrination: What is it to Indoctrinate Someone? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Agnosticism about God’s Existence – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Modal Epistemology: Knowledge of Possibility & Necessity – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Cosmological Arguments for the Existence of God – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Philosophy and Its Contrast with Science: Comparing Philosophical and Scientific Understanding – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Critical Thinking: What is it to be a Critical Thinker? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Descartes’ Meditations 1-3 – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: “I think, therefore I am”: Descartes on the Foundations of Knowledge – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Pascal’s Wager: A Pragmatic Argument for Belief in God – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Conspiracy Theories – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Epistemology: A collection of articles, videos, and podcasts. - The Daily Idea

- Pingback: Philosophy – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

Shared at Daily Nous, Online Philosophy Resources Weekly Update http://dailynous.com/2020/08/31/online-philosophy-resources-weekly-update-214/

Comments are closed.

Overview – The Definition of Knowledge

The definition of knowledge is one of the oldest questions of philosophy. Plato’s answer, that knowledge is justified true belief , stood for thousands of years – until a 1963 philosophy paper by philosopher Edmund Gettier challenged this definition.

Gettier described two scenarios – now known as Gettier cases – where an individual has a justified true belief but that is not knowledge.

Since Gettier’s challenge to the justified true belief definition, various alternative accounts of knowledge have been proposed. The goal of these accounts is to define ‘knowledge’ in a way that rules out Gettier cases whilst still capturing all instances of what we consider to be knowledge.

A Level philosophy looks at 5 definitions of knowledge :

- Justified true belief (the tripartite definition)

- JTB + No false lemmas

Reliabilism

Virtue epistemology, infallibilism.

It’s important to first distinguish the kind of knowledge we’re discussing here. Broadly, there are three kinds of knowledge:

- Ability: knowledge how – e.g. “I know how to ride a bike”

- Acquaintance: knowledge of – e.g. “I know Fred well”

- Propositional: knowledge that – e.g. “I know that London is the capital of England”

When we talk about the definition of knowledge, we are talking about the definition of propositional knowledge specifically.

Justified True Belief

The tripartite definition.

In Theaetetus , Plato argues that knowledge is “true belief accompanied by a rational account”. This got simplified to:

‘Justified true belief’ is known as the tripartite definition of knowledge.

Necessary and sufficient conditions

The name of the game in defining ‘knowledge’ is to provide necessary and sufficient conditions.

For example, ‘unmarried’ and ‘man’ are both necessary to be a ‘bachelor’ because if you don’t meet both these conditions you’re not a bachelor. Further, being an ‘unmarried man’ is sufficient to be a ‘bachelor’ because everything that meets these conditions is a bachelor. So, ‘unmarried man’ is a good definition of ‘bachelor’ because it provides both the necessary and sufficient conditions of that term.

The correct definition of ‘knowledge’ will work the same way. Firstly, we can argue that ‘justified’, ‘true’, and ‘belief’ are all necessary for knowledge.

For example, you can’t know something if it isn’t true . If someone said, “I know that the moon is made of green cheese” you wouldn’t consider that knowledge because it isn’t true.

Similarly, you can’t know something you don’t believe. It just wouldn’t make sense, for example, to say “I know today is Monday but I don’t believe today is Monday.”

And finally, justification . Suppose someone asks you if you know how many moons Pluto has. You have no interest in astronomy but just have a strong feeling about the number 5 because it’s your lucky number or whatever. You’d be right – Pluto does indeed have 5 moons – but it seems a bit of a stretch to say you knew Pluto has 5 moons. Your true belief “Pluto has 5 moons” is not properly justified and so would not count as knowledge.

So, ‘justified’, ‘true’, and ‘belief’ may each be necessary for knowledge. But are these conditions sufficient? If ‘justified true belief’ is also a sufficient definition of knowledge, then everything that is a justified true belief will be knowledge. However, this is challenged by Gettier cases .

Problem: Gettier cases

Gettier’s paper describes two scenarios where an individual has a justified true belief that is not knowledge. Both scenarios describe a belief that fails to count as knowledge because the justified belief is only true as a result of luck .

Gettier case 1

- Smith and Jones are interviewing for the same job

- Smith hears the interviewer say “I’m going to give Jones the job”

- Smith also sees Jones count 10 coins from his pocket

- Smith thus forms the belief that “the man who will get the job has 10 coins in his pocket”

- But Smith gets the job, not Jones

- Then Smith looks in his pocket and, by coincidence, he also has 10 coins in his pocket

Smith’s belief “the man who will get the job has 10 coins in his pocket” is:

- Justified: he hears the interviewer say Jones will get the job and he sees that Jones has 10 coins in his pocket

- True: the man who gets the job (Smith) does indeed have 10 coins in his pocket

This shows that the tripartite definition of knowledge is not sufficient : you can have a justified true belief that is not knowledge.

Gettier case 2

Gettier’s second example relies on the logical principle of disjunction introduction (or, more simply, addition ).

Disjunction introduction says that if you have a true statement and add “or some other statement” then the full statement (i.e. “true statement or some other statement”) is also true.

For example: “London is the capital of England” is true. And so the statement “either London is the capital of England or the moon is made of green cheese” is also true, because London is the capital of England. Even though the second part (“the moon is made of green cheese”) is false, the overall statement is true because the or means only one part has to be true (in this case “London is the capital of England”).

Gettier’s second example is as follows:

- Smith has a justified belief that “Jones owns a Ford”

- So, using the principle of disjunctive introduction above, Smith can form the further justified belief that “Either Jones owns a Ford or Brown is in Barcelona”

- Smith thinks his belief that “Either Jones owns a Ford or Brown is in Barcelona” is true because the first condition is true (i.e. that Jones owns a Ford)

- But it turns out that Jones does not own a Ford

- However, by sheer coincidence, Brown is in Barcelona

So, Smith’s belief that “Either Jones owns a Ford or Brown is in Barcelona” is:

- True: “Either Jones owns a Ford or Brown is in Barcelona” turns out to be true. But Smith thought it was true because of the first condition (Jones owns a Ford) whereas it turns out it is true because of the second condition (Brown is in Barcelona)

- Justified: The original belief “Jones owns a Ford” is justified, and so disjunction introduction means that the second belief “Either Jones owns a Ford or Brown is in Barcelona” is also justified.

But despite being a justified true belief, it is wrong to say that Smith’s belief counts as knowledge, because it was just luck that led to him being correct.

This again shows that the tripartite definition of knowledge is not sufficient .

Problem: Not necessary

The majority of this debate focuses on whether the tripartite definition is sufficient for knowledge, but you can potentially argue that one or more of the conditions are not necessary :

- Justification: The fact that children and animals appear to possess knowledge suggests that justification is not necessary for knowledge because children and animals have knowledge even though they can’t justify it.

- Truth: Zagzebski’s definition of knowledge does not explicitly include true as a condition but instead talks about acts of intellectual virtue (which kind of implies truth but anyway). Some philosophers reject the very idea of objective truth, but that’s getting a bit off-piste.

- Belief: You can potentially imagine scenarios where someone knows something but doesn’t believe it. For example, you may have heard years ago that Pluto has 5 moons but forgotten it consciously . But when asked years later “how many moons does Pluto have?” you correctly answer “5” – even though you’re not sure about this answer and don’t really believe it.

Alternative definitions of knowledge

Gettier cases are a devastating problem for the tripartite definition of knowledge .

In response, philosophers have tried to come up with new definitions of knowledge that avoid Gettier cases.

Generally, these new definitions seek to refine the justification condition of the tripartite definition. True and belief remain unchanged.

JTB + no false lemmas

The no false lemmas definition of knowledge aims to strengthen the justification condition of the tripartite definition.

It says that James has knowledge of P if:

- James believes that P

- James’s belief is justified

- James did not infer that P from anything false

So, basically, it adds an extra condition to the tripartite definition . It says knowledge is justified true belief + that is not inferred from anything false (a false lemma).

This avoids the problems of Gettier cases because Smith’s belief “the man who will get the job has 10 coins in his pocket” is inferred from the false lemma “Jones will get the job” .

- The tripartite definition says Smith’s belief is knowledge, even though it isn’t

- The no false lemmas response says Smith’s belief is not knowledge, which is correct.

So, in this instance, the no false lemmas definition appears to be a more accurate account of knowledge than the tripartite view: it avoids saying Gettier cases count as knowledge.

Problem: fake barn county

However, the no false lemmas definition of knowledge faces a similar problem: the fake barn county situation:

- In ‘fake barn county’, the locals create fake barns that look identical to real barns

- Henry is driving through fake barn county, but he doesn’t know the locals do this

- These beliefs are not knowledge , because they are not true – the barns are fake

- This time the belief is true

- It’s also justified by his visual perception of the barn

- And it’s not inferred from anything false.

According to the no false lemmas definition, Henry’s belief is knowledge.

But this shows that the no false lemmas definition must be false. Henry’s belief is clearly not knowledge – he’s just lucky in this instance.

Reliabilism says James knows that P if:

- James’s belief that P is caused by a reliable method

A reliable method is one that produces a high percentage of true beliefs.

So, if you have good eyesight, it’s likely that your eyesight would constitute a reliable method of forming true beliefs. If you have an accurate memory, it’s likely your memory would also be a reliable method for forming true beliefs. If a website is consistent in reporting the truth, that website would also count as a reliable method.

But if you form a belief through an unreliable method – for example by simply guessing or using a biased source – then it would not count as knowledge even if the resultant belief is true.

Children and Animals

An advantage of reliabilism is that it allows for young children and animals to have knowledge. Typically, we attribute knowledge to young children and animals. For example, it seems perfectly sensible to say that a seagull knows where to find food or that a baby knows when its mother is speaking.

However, pretty much all the other definitions of knowledge considered here imply that animals and young children can not have knowledge. For example, a seagull or a baby can’t justify its beliefs and so justified true belief rules out seagulls and young babies from having knowledge. Similarly, if virtue epistemology is the correct definition, it is hard to see how a seagull or a newly born baby could possess intellectual virtues of care about forming true beliefs and thus possess knowledge.

However, both young children and animals are capable of forming beliefs via reliable processes, e.g. their eyesight, and so according to reliabilism are capable of possessing knowledge.

You can argue against reliabilism using the same fake barn county argument above : Henry’s true belief that “there’s a barn” is caused by a reliable process – his visual perception. Reliabilism would thus (incorrectly) say that Henry knows “there’s a barn” even though his belief is only true as a result of luck.

There are several forms of virtue epistemology (we will look at two), but common to all virtue epistemology definitions of knowledge is a link between a belief and intellectual virtues . Intellectual virtues are somewhat analogous to the sort of moral virtues considered in Aristotle’s virtue theory in moral philosophy . However, instead of being concerned with moral good, intellectual virtues are about epistemic good. For example, an intellectually virtuous person would have traits such as being rational, caring about what’s true, and a good memory.

Linda Zagzebski: What is Knowledge?

Formula for creating gettier-style cases.

Philosopher Linda Zagzebski argues that definitions of knowledge of the kind we have looked at so far (i.e. ‘true belief + some third condition ’) will always fall victim to Gettier-style cases. She provides a formula for constructing such Gettier cases to defeat these definitions:

- E.g. Henry’s belief “there’s a barn” when he is looking at the fake barns

- E.g. Henry’s belief “there’s a barn” when he is looking at the one real barn

- In the second case, the belief will still fit the definition (‘true belief + some third condition ’) because it’s basically the same as the first case

- But the second case won’t be knowledge, because it’s only true due to luck

Zagzebski argues that this formula will always provide a means to defeat any definition of knowledge that takes the form ‘true belief + some third condition’ (whether that third condition is justification , formed by a reliable process , or whatever).

The reason for this is that truth and the third condition are simply added together, but not linked ( the belief is not apt , to use Sosa’s terminology ). The fact that truth and the third condition are not linked leaves a gap where lucky cases can incorrectly fit the definition.

Zagzebski’s definition of knowledge

The issues resulting from the gap between truth and the third condition motivate Zagzebski to do away with the ‘truth’ condition altogether. Instead, Zagzebski’s analysis of knowledge is that James knows that P if:

- James’s belief that P arises from an act of intellectual virtue

However, in Zagzebski’s analysis of knowledge, the ‘truth’ of the belief is kind of implied by the idea of an act of intellectual virtues. This can be shown by drawing a comparison with moral virtue :

An act of moral virtue is one where the actor both intends to do good and achieves that goal. For example, intending to help an old lady across the road but killing her in the process is not an act of moral virtue because it doesn’t achieve a virtuous goal (despite the virtuous intent). Likewise, helping the old lady across the road because you think she will give you money is not an act of moral virtue – even though it succeeds in achieving a virtuous goal – because your intentions aren’t good.