The University of Mississippi

Research, scholarship, innovation, and creativity.

- Policies & Procedures

- New Uniform Guidance

- Manuals & Guides

5.1 - Solicited vs. Unsolicited Proposals

A proposal is the document submitted to the prospective funding source outlining the entire program, including goals, objectives, methods, time lines, expertise committed, and program budget. The terms proposal and application are often used synonymously. However, in some cases, an application form is required by the sponsor and is just one part of the entire proposal.

A solicited proposal is one that is submitted in response to a specific work statement from the sponsor. A Request for Proposals (RFP) or Request for Applications (RFA) is sometimes used by sponsors to solicit proposals for specific research, development, or training projects or to provide specific services or goods. The RFP or RFA generally includes standard terms, conditions, and assurances that the institution is asked to accept.

An unsolicited proposal is initiated by the applicant and submitted according to the sponsor’s broad guidelines. The funding arrangement for unsolicited proposals is usually a grant.

Site Search | Site Index | Feedback | Staff Directory

©2011 The University of Mississippi

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Explore sell to government

- Ways you can sell to government

- How to access contract opportunities

- Conduct market research

- Register your business

- Certify as a small business

- Become a schedule holder

- Market your business

- Research active solicitations

- Respond to a solicitation

- What to expect during the award process

- Comply with contractual requirements

- Handle contract modifications

- Monitor past performance evaluations

- Explore real estate

- 3D-4D building information modeling

- Art in architecture | Fine arts

- Computer-aided design standards

- Commissioning

- Design excellence

- Engineering

- Project management information system

- Spatial data management

- Facilities operations

- Smart buildings

- Tenant services

- Utility services

- Water quality management

- Explore historic buildings

- Heritage tourism

- Historic preservation policy, tools and resources

- Historic building stewardship

- Videos, pictures, posters and more

- NEPA implementation

- Courthouse program

- Land ports of entry

- Prospectus library

- Regional buildings

- Renting property

- Visiting public buildings

- Real property disposal

- Reimbursable services (RWA)

- Rental policy and procedures

- Site selection and relocation

- For businesses seeking opportunities

- For federal customers

- For workers in federal buildings

- Explore policy and regulations

- Acquisition management policy

- Aviation management policy

- Information technology policy

- Real property management policy

- Relocation management policy

- Travel management policy

- Vehicle management policy

- Federal acquisition regulations

- Federal management regulations

- Federal travel regulations

- GSA acquisition manual

- Managing the federal rulemaking process

- Explore small business

- Explore business models

- Research the federal market

- Forecast of contracting opportunities

- Events and contacts

- Explore travel

- Per diem rates

- Transportation (airfare rates, POV rates, etc.)

- State tax exemption

- Travel charge card

- Conferences and meetings

- E-gov travel service (ETS)

- Travel category schedule

- Federal travel regulation

- Travel policy

- Explore technology

- Cloud computing services

- Cybersecurity products and services

- Data center services

- Hardware products and services

- Professional IT services

- Software products and services

- Telecommunications and network services

- Work with small businesses

- Governmentwide acquisition contracts

- MAS information technology

- Software purchase agreements

- Cybersecurity

- Digital strategy

- Emerging citizen technology

- Federal identity, credentials, and access management

- Mobile government

- Technology modernization fund

- Explore about us

- Annual reports

- Mission and strategic goals

- Role in presidential transitions

- Get an internship

- Launch your career

- Elevate your professional career

- Discover special hiring paths

- Events and training

- Agency blog

- Congressional testimony

- GSA does that podcast

- News releases

- Leadership directory

- Staff directory

- Office of the administrator

- Federal Acquisition Service

- Public Buildings Service

- Staff offices

- Board of Contract Appeals

- Office of Inspector General

- Region 1 | New England

- Region 2 | Northeast and Caribbean

- Region 3 | Mid-Atlantic

- Region 4 | Southeast Sunbelt

- Region 5 | Great Lakes

- Region 6 | Heartland

- Region 7 | Greater Southwest

- Region 8 | Rocky Mountain

- Region 9 | Pacific Rim

- Region 10 | Northwest/Arctic

- Region 11 | National Capital Region

- Per Diem Lookup

Unsolicited Proposals

An Unsolicited Proposal is a written application for a new or innovative idea submitted to a Federal agency on the initiative of the offeror for the purpose of obtaining a contract with the government, and that is not in response to a Request for Proposals, Broad Agency Announcement, Program Research and Development Announcement, or any other Government-initiated solicitation or program.

Each agency is responsible for reviewing unsolicited proposals that are relevant to their mission areas.

If you believe you have an unsolicited proposal that is related to GSA's mission, please review FAR part 15.6 and GSAM part 515.6 .

Once you have:

- Reviewed the requirements in the FAR and GSAM

- Made the determination you have a valid unsolicited proposal for GSA

- Determined the proposal is related to GSA's mission

You may submit your proposal to [email protected] .

Please Note:

- GSA is unable to review or comment on unsolicited proposals that are for other agencies, or that are not directly related to GSA's mission.

- Due to the significant amount of advertising material submitted to agency inboxes, GSA does not intend to respond to a proposal that is unrelated to GSA's mission, directed to another agency, and/or one which does not include all the required content per FAR 15.605 or meet FAR 15.606-1 . To assist you in ensuring you have provided the required details, GSA is providing the below checklist you may use when submitting an unsolicited proposal.

Unsolicited Proposal Checklist

- Offeror’s Name and Address

- Type of Organization (e.g., profit, nonprofit, educational, small business)

- Contact Name, Phone Number, and Email Address (i.e., person that can negotiate)

- GSA Organization Relevant for the Proposal (e.g., FAS PSHC, PBS Region 3, PBS Leasing, Office of GSA IT, etc.)

- Names of Other Federal, State or Local Government Entities Receiving the Proposal

- Description of Product(s) or Services(s)

- Period of Performance (Including Base Period and Options)

- Place of Performance

- Proposed Price or Total Estimated Cost for the Effort

- Proposal Validity Period (6-month minimum suggested)

- Identification of any proprietary data, organizational conflicts of interest, security clearances, or environmental impacts (if applicable)

- Reasonably complete discussion stating objectives of the effort

- Method of approach and extent of effort to be employed

- Nature and extent of the anticipated results

- Manner in which the work will help to support accomplishment of the agency’s mission

- Key personnel information who would be involved, including alternates

- Brief description of facilities to be used

- Type of support needed from the agency (e.g., Government property or personnel resources)

- Type of contract preferred (e.g., fixed price, cost plus)

- Brief description of the organization, previous experience, relevant past performance

- Sufficient detail for proposed price or total estimated cost to allow meaningful evaluation

- Name/Signature and Date of Authorized Offeror Representative

PER DIEM LOOK-UP

1 choose a location.

Error, The Per Diem API is not responding. Please try again later.

No results could be found for the location you've entered.

Rates for Alaska, Hawaii, U.S. Territories and Possessions are set by the Department of Defense .

Rates for foreign countries are set by the State Department .

2 Choose a date

Rates are available between 10/1/2021 and 09/30/2024.

The End Date of your trip can not occur before the Start Date.

Traveler reimbursement is based on the location of the work activities and not the accommodations, unless lodging is not available at the work activity, then the agency may authorize the rate where lodging is obtained.

Unless otherwise specified, the per diem locality is defined as "all locations within, or entirely surrounded by, the corporate limits of the key city, including independent entities located within those boundaries."

Per diem localities with county definitions shall include "all locations within, or entirely surrounded by, the corporate limits of the key city as well as the boundaries of the listed counties, including independent entities located within the boundaries of the key city and the listed counties (unless otherwise listed separately)."

When a military installation or Government - related facility(whether or not specifically named) is located partially within more than one city or county boundary, the applicable per diem rate for the entire installation or facility is the higher of the rates which apply to the cities and / or counties, even though part(s) of such activities may be located outside the defined per diem locality.

Guidance for the Preparation and Submission of Unsolicited Proposals

Revised may 2016, table of contents.

I. Introduction

(a) Important Caveat to Potential Proposers

II. Eligibility

(a) Applicant Eligibility

(b) Defining An Unsolicited Proposal

(c) What Is Not An Unsolicited Proposal

III. Submission

(a) How to Submit

(b) When To Submit

(c) Revision or Withdrawal

(d) Interagency Coordination

IV. Proposal Form and Content

(c) Cover Pages

(d) Proposal Content

V. Evaluation

VI. Selection or Declination of Unsolicited Proposals

VIII. NASA Research Areas and Other NSPIRES Cover Page Questions

NASA encourages the submission of unique and innovative proposals that will further the Agency's mission. While the vast majority of proposals are solicited, ( http://nspires.nasaprs.com/external/solicitations/solicitations.do?method=init&stack=push ) a small number of unsolicited proposals that cannot be submitted to those solicitations and yet are still relevant to NASA are reviewed and some are funded each year.

This document provides guidelines for the preparation of formal unsolicited proposals to those who wish to convey their creative methods or approaches to NASA. These guidelines apply to all unsolicited proposals for financial assistance (i.e., those that would result in grants and cooperative agreements) regardless of the NASA Installation or Agency program for which they are intended. However, these guidelines do not apply to solicited proposals, nor do they apply to proposals that would result in contracts, i.e., they are not for acquisition. Projects toward the research and development end of the spectrum are more likely to result in a grant (or grant-like award), rather than a contract and thus more likely to be suitable as unsolicited proposals. Proposals to provide supplies or services or to otherwise satisfy a NASA requirement, i.e., those that would result in a contract, do not fall under this guidance but are instead governed by the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) and the NASA FAR Supplement (NFS).

Before any effort is expended in preparing a proposal, potential proposers should:

(1) Review the current versions of the NASA Strategic Plan and documents from the specific directorate, office, or program for which the proposal is intended (e.g., the Science Plan , the Strategic Space Technology Investment Plan , the Aeronautics Strategic Vision , Voyages: Charting the Course for Sustainable Human Space Exploration , etc.) to determine if the work planned is sufficiently relevant to current goals to warrant a formal submission. NASA will return without peer review any proposal that is deemed not relevant to the office to which it was sent.

(2) Potential proposers must review current opportunities (e.g., at https://nspires.nasaprs.com/external/solicitations/solicitations.do?method=init&stack=push to determine if any solicitation already exists to which the potential project could be proposed. NASA will return without review any proposal that could have been responsive to a recent or current solicitation, or one that is currently planned for the near future. Having missed a deadline for a recent open solicitation does not allow a proposal to be submitted as an unsolicited proposal.

(3) Potential proposers should review current awards (e.g., by doing key word searches at Research.gov , or at the NSSC grant status page , and the NASA Life and Physical Sciences Task Book ) to learn what, if any, related work is already funded by NASA. Such preparation reduces the risk of redundancy, improves implementation, and sometimes results in collaboration.

Finally, after those three things have been done, the proposer may contact an appropriate NASA person to determine whether NASA has any interest in the type of work being proposed and if any funding is currently available. Since NASA does not reserve any funding for unsolicited proposals, viable ideas may not be supported simply for lack of funds. Discussions between NASA and potential proposers that convey an understanding of the Agency mission and needs relative to the type of effort contemplated do not jeopardize the unsolicited status of any subsequently submitted proposal.

Any category of organization or institution may submit an unsolicited proposal. There is no restriction on teaming arrangements involving US organizations, including teaming with government personnel. However, each proposal must be a separate, stand-alone, complete document for evaluation purposes and any proposal that involves more than one organization should describe the distinct contributions expected from any participating investigator or organization, including facilities or equipment that may be required. When multiple organizations are involved in a single proposal, government labs are generally funded directly, but other than that a single award is made to the submitting organization (see Section VII ). Simultaneous submission of related proposals from cooperating organizations is permitted if it indicates the nature of the relationship among the proposals, and these may result in parallel awards.

NASA's policy is to conduct research with foreign entities on a cooperative, no-exchange-of-funds basis. NASA does not normally fund foreign research proposals from foreign organizations, nor research efforts by individuals at foreign organizations as part of U.S. research proposals. This includes subawards from US organizations to investigators at foreign organizations and also travel by individuals at foreign organizations to conduct research, fieldwork, and present at conferences. Rather, each country agrees to bear the cost of discharging their respective responsibilities (i.e., the work to be done by team members affiliated with organizations in their country). The direct purchase of supplies and/or services, which do not constitute research, from non-U.S. sources by U.S. award recipients is permitted. Proposals from foreign entities must be submitted in the same format as U.S. proposals and in U.S. dollars. All information should be typed and in English. The proposal should emphasize the unique nature of the project and/or the unique expertise of the proposer. Foreign proposals will go through the same evaluation and selection process as U.S. Proposals

There are special restrictions on NASA regarding the People's Republic of China. Proposals must not include bilateral participation, collaboration, or coordination with China or any Chinese-owned company or entity, whether funded or performed under a no-exchange-of-funds arrangement. In accordance with Public Law 113-235, Division B, Title V, Section 532, NASA is prohibited from funding any work that involves the bilateral participation, collaboration, or coordination with China or any Chinese-owned company or entity, at the prime recipient level or at any subrecipient level , whether funded or performed under a no-exchange-of-funds arrangement. Proposals involving bilateral participation, collaboration, or coordination in any way with China or any Chinese-owned company, whether funded or performed under a no-exchange-of-funds arrangement , may be ineligible for award.

Finally, only proposals for financial assistance (i.e., grants and cooperative agreements) are covered by this guidance. See the introduction for information regarding contracts, which are not covered by this document.

If a commercial organization wants to receive a grant or cooperative agreement, cost sharing is required unless the commercial organization can demonstrate that it does not expect to receive substantial compensating benefits for performance of the work. If this demonstration is made, cost sharing is not required but may be offered voluntarily. Reference also 2 CFR §1800.922 and 14 CFR §1274.204, (Costs and Payments), paragraph (b), Cost Sharing

An unsolicited proposal is a written submission to an Agency on the initiative of the submitter for the purpose of obtaining an award from the Government and that is not in response to a formal or informal request (other than a publicized general statement of needs or a document such as this one). For more information see Section 5.3 (Non-Competitive Awards) of the NASA Grant and Cooperative Agreement Manual .

To be eligible as an unsolicited proposal, a submission must:

1. Be of high scientific and/or technical merit: presenting unique and innovative methods, approaches, concepts, or advanced technologies, demonstrate adequate qualifications, capabilities and experience of the proposed team, facilities or other capabilities of the Offeror, and display a high overall standing of vs. the state of the art. 2. Be relevant to NASA generally and specifically to the office within NASA to which the proposal is directed. 3. Have reasonable and realistic proposed costs, and 4. The proposal can not be eligible for a recent, current, or pending NASA solicitation, see the important caveat to potential proposers in the Introduction.

Moreover, the proposal must contain adequate detail and be clear and organized enough that reviewers can easily assess the criteria above.

A proposal that fails to meet the definition of an unsolicited proposal, or that falls under any of the seven following categories is not a valid unsolicited proposal:

1. Technical correspondence that consists of a written inquiry from an individual, academic researcher, or others that should be addressed to NASA program offices, including:

• Inquiries regarding NASA's interest in research areas, • Pre-proposal exploration, • General technical inquiries, • Concepts or ideas with little detail, • Unofficial submissions not sent in according to the submission instructions here, and • Research descriptions or suggestions that do not request NASA resources, typically funding.

2. Proposals for known NASA requirements that can be acquired by a competitive method, such as an offer to perform ordinary tasks (e.g., provide computer facilities or services) or that resemble a current, recent, or pending formal NASA solicitation.

3. Proposals for commercial items that are usually sold to the general public.

4. Advertising material designed to acquaint the Government with a prospective contractor's present products or potential capabilities.

5. Contributions that are concepts, suggestions, or ideas presented to the Government in which the source may not devote any further effort to it on the Government's behalf.

6. An invention or discovery that has officially received a patent or is otherwise protected under title 35 of the U.S. Code. If the Proposer is an owner of an issued U.S. patent, he or she may offer NASA a license in the patented invention by writing to the Office of the Associate General Counsel, Commercial and Intellectual Property Practice Group, NASA Headquarters, 300 E Street, SW, Washington, DC 20546. Please identify the U.S. patent number in your correspondence. An investigation will then be made to determine the extent of NASA's interest. Note that only U.S. patents will be considered.

7. A proposal for a new award or the renewal of an existing award that falls within the scope of an open NASA solicitation. These proposals must be submitted in response to that announcement unless it is determined that doing so will place the unsolicited proposal at a competitive disadvantage. If such a determination is made, the unsolicited proposal will be evaluated separately.

8. An unsolicited proposal is not an appropriate mechanism to request start-up funds to establish a laboratory.

(a) How To Submit

All proposals must be submitted electronically via the NASA Solicitation and Proposal Integrated Review and Evaluation System (NSPIRES) in response to the unsolicited proposal response structure. After logging into NSPIRES a prospective proposer should follow the link from "Proposals/NOIs" and then "Create Proposal" choose source = "Solicitation" click continue and then click the radio button for "Unsolicited" and proceed from there. As part of the submission process proposers will answer the program specific questions on the NSPIRES web pages that will identify the appropriate Proposal Coordinating Office at NASA. Refer to the example questions in Section VIII at the end of this document.

All proposals to NASA must be submitted electronically. No hard copy proposals will be accepted. The only exceptions will be granted consistent with Section 5.1.5 of the Grants and Cooperative Agreements Manual. Electronic proposals must be submitted by one of the officials at the PI's organization who is authorized to make such a submission ; electronic submission by the authorized organization representative (AOR) serves for the proposal as the required original signature by an authorized official of the proposing organization. Every organization that intends to submit an unsolicited proposal to NASA must be registered in NSPIRES. Registration must be performed by an organization's electronic business point-of-contact in the System for Award Management http://www.sam.gov . Each individual team member (e.g., PI, Co-Investigators, etc.), including all personnel named on the proposal's electronic cover page, must be individually registered in NSPIRES. Each individual team member must confirm their participation on that proposal (indicating team member role) and specify an organizational affiliation. Only one version of a proposal should be submitted to NASA. Proposals that duplicate (or that have significant overlap with) a proposal under review with NASA should not be submitted to NASA.

Although any individual may create a proposal and release it to their organization, only a responsible person authorized to represent and obligate the offeror (an Authorized Organizational Representative or AOR) may officially "submit" a proposal via NSPIRES. For more information about the registering an organization in NSPIRES and or affiliating as an individual with an existing organization please see the NSPIRES tutorials and user guides at http://nspires.nasaprs.com/tutorials/.

There are no specific dates for the submission of unsolicited proposals. However, proposals should be submitted at least six (6) months in advance of the desired starting date. Each year a new response structure will be created in NSPIRES near the start of the Governmentclass='MsoListParagraphCxSpMiddle's fiscal year beginning October 1 of each year, and ending one year later. Proposals should be submitted in the same fiscal year in which they were created. If a proposal is not submitted by the end of the fiscal year then it may be lost and will have to be recreated in the following fiscal year's response structure.

Proposals may be withdrawn by the proposing organization at any time. If the offeror wishes to submit additional material or submit a revision an AOR must withdraw the proposal in NSPIRES and, after revision, resubmit via NSPIRES. The resubmitted proposal will be given a new proposal number in NSPIRES. Major revisions are likely to delay the evaluation process.

NASA does not transfer formal submissions to or accept similar submissions from other agencies, except as they might be related to an interagency funding arrangement. Unsolicited proposals submitted to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) are not considered as formal submissions to NASA.

IV Proposal Form and Content

Proposers must adhere to the standard format described in the NASA Guidebook for Proposers , or a format described in a recent solicitation from the directorate or office for which the proposal is intended. If the proposal is so disorganized or poorly written that evaluators deem it a significant obstacle to evaluation, it may be returned without review. The Proposer has the option to resubmit the proposal after making modifications.

Proposals should be brief and concentrate on substantive material essential for a complete understanding of the project. Experience shows that few proposals require a technical section that exceeds 15 pages to adequately explain the proposed work, and many are shorter. Indeed, rather than investing considerable effort into a lengthy and detailed unsolicited proposal, proposers are strongly encouraged to submit brief (1-3 page) summary focused on what is proposed why, and the unique qualifications of the proposer(s), to allow NASA to ascertain if the proposed work is relevant and eligible. Please see the NASA Guidebook for Proposers for what is included in each section of a proposal and which sections are page limited. All necessary detailed information, such as figures, tables, charts, engineering diagrams, CVs, current and pending support, and budgets should be included in the single proposal PDF file uploaded into NSPIRES.

(c) Cover page Information

As is the case for all proposals submitted via NSPIRES, the web interface will prompt the proposer for basic information at the time of proposal creation, such as proposal title and organizational affiliation of the PI, and will permit the PI to choose team members, assign their roles and access, and enter budget information. Proposers should familiarize themselves with NSPIRES. NSPIRES tutorials and user guides at http://nspires.nasaprs.com/tutorials/ . The proposer or AOR will have to answer other questions prior to proposal submission to help NASA assign unsolicited proposals to the right department for evaluation. Please see Section VIII at the end of this guidance document.

Unsolicited proposals should include the fundamental parts given in Section 2.3 of the NASA Guidebook for Proposers to facilitate an objective and timely evaluation. In particular, proposers should refer to the table in Section 2.3.1(a) Proposal Checklist. If the Proposal is missing content that evaluators deem required for evaluation, it may be returned without review. The Proposer has the option to resubmit the proposal after making modifications.

(i) Project Summary

The NSPIRES system will require proposers to provide a "Project Summary" of up to 4000 characters (including spaces and invisible control characters if cut and paste from Microsoft Word) that provides an overview of the proposed investigation. This abstract or Proposal Summary will be publicly accessible should the proposal be selected, so it should not contain any proprietary data or information that should not be released to the public (e.g., ITAR).

(ii) Data Management Plan

The NSPIRES system will require proposers provide a data management plan (DMP) of up to 4000 characters (including spaces and invisible control characters if cut and paste from Microsoft Word) as part of the proposal cover page. The kind of proposal that requires a data management plan is described in the NASA Plan for increasing access to results of Federally funded research and those proposing to the Science Mission Directorate may also refer to the SARA FAQs on this subject . This requirement supersedes the data-sharing plan mentioned in the NASA Guidebook for Proposers . If the proposer feels that it would be useful to provide more information on data management or archiving, they may do so in the body of the technical proposal.

(iii) Project Description: The Main Scientific/Technical part of the proposal

Proposers are encouraged to refer to the descriptions of the expected content and constituent parts of a proposal that appear in the NASA Guidebook for Proposers . The main body of the proposal should be a detailed statement of the work to be undertaken. The proposal should describe the complete project. The proposal should clearly describe what work is being done when and why. The duration of the project should be adequately justified. It should include objectives and expected significance (particularly in the context of the national aerospace effort), relation to the present state of knowledge in the field, relation to any previous work done on the project, and to related work in progress elsewhere. The document should fully describe the implementation, including the design of any experiments, observations, instrument development or modeling to be undertaken, methods and procedures at a level of detail adequate to demonstrate the likelihood of success. The best proposals present uncertainties in measurements, address potential pitfalls, and consider alternatives.

(iv) Management Approach.

Proposals for large or complex efforts involving interactions among numerous individuals or other organizations should describe plans for distribution of responsibilities and necessary arrangements for ensuring a coordinated effort. Aspects of any important working relations with organizations other than the offeror, including Government Agencies, especially NASA that were not already defined elsewhere in the proposal, should be described in the management section.

(v) Personnel

Every team member identified as a participant on the proposal's cover page and/or in the proposal's Scientific/Technical/Management Section must acknowledge his/her intended participation in the proposed effort. The NSPIRES proposal management system allows for participants named on the Proposal Cover Page to acknowledge a statement of commitment electronically. If the team member cannot confirm their participation in NSPIRES then the proposer may include a statement of participation from this person in the body of the proposal

Outline the relevant experience and/or expertise of all key personnel in a way that would demonstrate these capabilities in relation to the proposed effort; a short biographical sketch, a list of principal publications, and any exceptional qualifications should be included. Give the names and titles of any others associated substantially with the project in an advisory capacity. Any substantial collaboration with individuals not referred to in the budget or use of consultants should be described.

The Proposer or principal investigator will be responsible for direct supervision of the work and participates in the conduct of the effort regardless of whether or not compensation is received under the award.

Educational institutions should list the approximate number of students/assistants involved in the project and information about their level of academic attainments.

Omit social security numbers and any personal information not required for NASA to evaluate the proposal.

(vi) Facilities and Equipment

Identify any unique facilities, Government-owned facilities, industrial plant equipment or special tooling that will be required. A letter is required from the owner of any facility or resource that is not under the PI's direct control, acknowledging that the facility or resource is available for the proposed use during the proposed period. For Government facilities, the availability of the facility to users is often stated in the facilities documentation or web page. Where the availability is not publicly stated, or where the proposed use goes beyond the publicly stated availability, a statement, signed by the appropriate Government official at the facility verifying that it will be available for the required effort, is sufficient.

(vii) Proposed Costs

Proposals must state the funding level being requested accompanied by a budget with sufficient detail to permit an understanding of the basis of the funding request. As applicable, include separate cost estimates for the following:

- salaries, wages, and fringe benefits for each employee;

- expendable materials and supplies;

- domestic and foreign travel;

- IT expenses;

- publication or page charges;

- consultants;

- contracts with budget breakdowns;

- sub-awards with budget breakdowns;

- other miscellaneous identifiable direct costs; and

- indirect costs.

List estimated expenses as yearly requirements by major work phases. If the proposal is multi-year in scope, submit separate cost estimates for each year.

List salaries and wages in appropriate organizational categories; for example, principal investigator, other scientific and engineering professionals, graduate research assistants and technicians, and other non-professional personnel. Estimate personnel data in terms of full months or fractions of full time. Do not use separate "confidential" or "proprietary" salary pages.

Proposers may not acquire and charge general-purpose equipment in excess of $5K as a direct cost without the advance, written approval of the Agency's Grant Officer . Such requests must explain why indirect costs cannot be charged for the requested item or items and what controls will be put in place to assure that the property will be used exclusively for research purposes (i.e., explain why the proposed general purpose equipment cannot also be used for other purposes).

Explanatory notes should accompany the budget to provide identification and estimated costs of major capital equipment items to be acquired; purpose and estimated number and lengths of trips planned; basis for indirect costs; and clarification of other items that are not self-evident. Allowable costs are governed by 2 CFR 200.

(viii) Other Matters

Include any required statements of environmental impact of the effort, human subject or animal care provisions, conflict of interest, or such other topics as may be required by the nature of the effort and current statutes, executive orders, or other government-wide guidelines.

As indicated in the NASA Guidebook for Proposers , proposers should include a brief description of relevant facilities and previous work experience in the field of their proposals, current and pending support, and a Table of work effort for proposal team members.

(ix) Limited Distribution of Proprietary Information

It is NASA policy to subject proposals to peer review thus the information contained in proposals, including budgets may be made available to subject matter experts both inside and outside of the Agency for evaluation purposes only. Peer reviewers are required to sign non-disclosure agreements prior to viewing the contents of a proposal. Any information that the proposer believes is covered by ITAR should be clearly identified in the proposal.

However, proposers should be aware that the proposal summary, that provides an overview of the proposed project, should be suitable for public release because if the proposal is selected the title, proposal summary, and the name of the PI and their affiliation will be posted in publicly accessible archives such as research.gov.

(x) Security

If the proposed effort requires access to or may generate national security classified information, the submitter will be required to comply with applicable Government security regulations. Proposals should not contain national security classified material.

All unsolicited proposals will receive equitable handling and, if eligible, peer review. The principal elements considered in evaluating a proposal are 1) its technical, scientific and/or engineering merit, 2) relevance to NASA, and 3) the cost realism and reasonableness. Proposers not already familiar with Merit, Relevance and Cost criteria and NASA's evaluation methods should refer to Section C of the NASA Guidebook for Proposers .

Several evaluation techniques are regularly used within NASA. Some proposals are reviewed entirely in-house, others are evaluated by a combination of in-house personnel and selected external reviewers, while still others are subject to a full external peer review either by mail or through assembled panels. Due regard for conflict of interest and protection of proposal information is always part of the process.

The decision to fund or not fund an unsolicited proposal is made by the selecting official based on the recommendation of NASA technical personnel and also programmatic factors. Even if a proposal is meritorious, relevant and the costs are reasonable, the selecting official may choose not to support the proposed work for other reasons, such as programmatic priorities, limited budget, or because the work is redundant with an existing award.

NASA may support an award as outlined in the proposal budget, or may offer to fund only selected tasks, or all tasks for a shorter duration (e.g., a one year pilot study), or a combination. Awards may be made contingent on acceptable revised versions of budgets, statements of work, data management plans, or other elements in the NASA Guidebook for Proposers .

Whether an unsolicited proposal is selected or declined, NASA will notify in writing the proposer of the decision in a timely manner. Whenever practicable, the evaluations that formed the basis of the decision, or a summary of those evaluations, will be provided to the proposer in writing. Notifications will be made and evaluations will be provided via NSPIRES, but may also be communicated by other methods.

The vast majority of unsolicited proposals to NASA are declined. The bulk of rejections of unsolicited proposals are either due to relevance or cost. A notification letter, citing the reason(s) for rejection, will be sent to the individual who made the submission. Proposers should make inquiries with the NASA official who signed the notification letter.

If a proposal is accepted, any budget negotiation and making the award will be handled by the Center Grant Officer. The unsolicited proposal will be used as the basis for negotiation with the original submitter. Additional information specific to the award process (certifications, cost and pricing data, facilities information, etc.) will be requested as the negotiations progress.

Unless otherwise noted in negotiations, NASA will send funds directly to any Co-Is at NASA centers and other Government laboratories, including JPL. Thus, if a proposal submitted by a university has a Government Co-I, the funds will not pass through the university, so the university (or other institution that receives a grant) should not include overhead or any other pass through charges on those funds. However, the proposer should assume that funds for Co-Is who do not work for the Government will pass through the grant recipient and those charges may be applied. Regardless of whether a Co-I will be funded through a subaward via the proposing institution or funded directly by NASA, the budget for the proposal must include all funding requested from NASA for the proposed investigation so as to facilitate the review of the budget by the grant officer upon which the award is contingent.

VIII NASA Research Areas and Other NSPIRES Cover Page Questions

As part of the submission process proposers will be asked to answer the program specific questions on the NSPIRES web pages that will help NASA identify the appropriate Proposal Coordinating Office at NASA to which their proposal should be directed. The example questions appear below. Note that the questions provided below are samples only; actual questions may differ and proposer should answer those questions they are presented with within NSPIRES.

1: Please select a NASA component that most closely represents the subject of your proposal . (You must choose one.)

• Aeronautics Research • Earth and Space Science Research • Education/Public Outreach • Space Exploration and Operations • Space Technology Development or Demonstration • I don't know

2: Please select a NASA Center where there might be a particular interest in your proposal . (You must choose one.) • Ames Research Center • Armstrong Flight Research Center • Glenn Research Center • Goddard Space Flight Center • NASA Headquarters, Washington, DC • Johnson Space Center • Kennedy Space Center • Langley Research Center • Marshall Space Flight Center • Stennis Space Center • Wallops Flight Facility • Not applicable or unknown

3: Please select a research, technology development, or outreach category that most closely aligns with the main topic of your proposal . (You must choose one.) Advanced Air Vehicles Airspace Operations and Safety Astronomy and/or Astrophysics Earth Science Exoplanet Research Game-Changing Technology Development Heliophysics Human Research Integrated Aviation Systems Planetary Science Public Awareness Small Spacecraft Technology Development Space Biology Space Flight Operations Space Launch Systems Space Physical Sciences Space Technology Research Technology-Based Innovative Advanced Concepts Transformative Aeronautics Concepts Other

4: Describe the objectives of your proposal and their relevance to NASA. You are strongly encouraged to link your objectives to NASA's strategic plan . (You may enter up to 4,000 characters.)

5: Briefly explain why you are submitting an unsolicited proposal instead of responding to a NASA solicitation . (You may enter up to 4,000 characters.) Please note: Before submitting an unsolicited proposal you should determine whether your proposal is within the scope of a current NASA opportunity. NASA will return without review any unsolicited proposal that is within scope of a current NASA opportunity, as explained in the Guidance for the Preparation and Submission of Unsolicited Proposals . Also explain whether or not this proposal was previously submitted to NASA, either as an unsolicited proposal or in response to a solicitation/funding opportunity.

6: Provide data management plan (DMP) or explain why one is unnecessary given the nature of the work proposed. Refer to the NASA Plan for Increasing Access to the Results of Federally Funded Research for additional instructions . (You may enter up to 4,000 characters. Enter more information, if required, in the technical section of your proposal.)

7: Does this proposal contain information and data that are subject to U.S. export control laws and regulations including Export Administration Regulations (EAR) and International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR)? <Yes/No> Please note: If you answer "yes" the cover of the proposal should have a notice that clearly indicates which parts of the proposal (e.g., page number, section, figure) contain export control information. Indicate all information and data that are subject to provisions of U.S. export control laws and regulations as described above. Be sure to describe clearly or highlight information and data that contain export-controlled material so they can be redacted, if necessary, prior to proposal review .

8: Does the proposed work include any involvement with collaborators in China or with Chinese organizations or does the proposed work include activities in China? <Yes/No> NASA's appropriation from Congress includes this restriction: "None of the funds made available by this [law] may be used for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration or the Office of Science and Technology Policy to develop, design, plan, promulgate, implement, or execute a bilateral policy, program, order, or contract of any kind to participate, collaborate, or coordinate bilaterally in any way with China or any Chinese-owned company unless such activities are specifically authorized by a law enacted after the date of enactment of this division."

9: Please provide the name and contact information, if you have it, of a NASA technical, education, or outreach specialist(s) who might have a particular interest in your proposal. Provide name, phone, e-mail, and NASA Center where the interested individual(s) works . <or "N/A" if none>

END OF DOCUMENT

The Federal Register

The daily journal of the united states government, request access.

Due to aggressive automated scraping of FederalRegister.gov and eCFR.gov, programmatic access to these sites is limited to access to our extensive developer APIs.

If you are human user receiving this message, we can add your IP address to a set of IPs that can access FederalRegister.gov & eCFR.gov; complete the CAPTCHA (bot test) below and click "Request Access". This process will be necessary for each IP address you wish to access the site from, requests are valid for approximately one quarter (three months) after which the process may need to be repeated.

An official website of the United States government.

If you want to request a wider IP range, first request access for your current IP, and then use the "Site Feedback" button found in the lower left-hand side to make the request.

What (Exactly) Is A Research Proposal?

A simple explainer with examples + free template.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | June 2020 (Updated April 2023)

Whether you’re nearing the end of your degree and your dissertation is on the horizon, or you’re planning to apply for a PhD program, chances are you’ll need to craft a convincing research proposal . If you’re on this page, you’re probably unsure exactly what the research proposal is all about. Well, you’ve come to the right place.

Overview: Research Proposal Basics

- What a research proposal is

- What a research proposal needs to cover

- How to structure your research proposal

- Example /sample proposals

- Proposal writing FAQs

- Key takeaways & additional resources

What is a research proposal?

Simply put, a research proposal is a structured, formal document that explains what you plan to research (your research topic), why it’s worth researching (your justification), and how you plan to investigate it (your methodology).

The purpose of the research proposal (its job, so to speak) is to convince your research supervisor, committee or university that your research is suitable (for the requirements of the degree program) and manageable (given the time and resource constraints you will face).

The most important word here is “ convince ” – in other words, your research proposal needs to sell your research idea (to whoever is going to approve it). If it doesn’t convince them (of its suitability and manageability), you’ll need to revise and resubmit . This will cost you valuable time, which will either delay the start of your research or eat into its time allowance (which is bad news).

What goes into a research proposal?

A good dissertation or thesis proposal needs to cover the “ what “, “ why ” and” how ” of the proposed study. Let’s look at each of these attributes in a little more detail:

Your proposal needs to clearly articulate your research topic . This needs to be specific and unambiguous . Your research topic should make it clear exactly what you plan to research and in what context. Here’s an example of a well-articulated research topic:

An investigation into the factors which impact female Generation Y consumer’s likelihood to promote a specific makeup brand to their peers: a British context

As you can see, this topic is extremely clear. From this one line we can see exactly:

- What’s being investigated – factors that make people promote or advocate for a brand of a specific makeup brand

- Who it involves – female Gen-Y consumers

- In what context – the United Kingdom

So, make sure that your research proposal provides a detailed explanation of your research topic . If possible, also briefly outline your research aims and objectives , and perhaps even your research questions (although in some cases you’ll only develop these at a later stage). Needless to say, don’t start writing your proposal until you have a clear topic in mind , or you’ll end up waffling and your research proposal will suffer as a result of this.

Need a helping hand?

As we touched on earlier, it’s not good enough to simply propose a research topic – you need to justify why your topic is original . In other words, what makes it unique ? What gap in the current literature does it fill? If it’s simply a rehash of the existing research, it’s probably not going to get approval – it needs to be fresh.

But, originality alone is not enough. Once you’ve ticked that box, you also need to justify why your proposed topic is important . In other words, what value will it add to the world if you achieve your research aims?

As an example, let’s look at the sample research topic we mentioned earlier (factors impacting brand advocacy). In this case, if the research could uncover relevant factors, these findings would be very useful to marketers in the cosmetics industry, and would, therefore, have commercial value . That is a clear justification for the research.

So, when you’re crafting your research proposal, remember that it’s not enough for a topic to simply be unique. It needs to be useful and value-creating – and you need to convey that value in your proposal. If you’re struggling to find a research topic that makes the cut, watch our video covering how to find a research topic .

It’s all good and well to have a great topic that’s original and valuable, but you’re not going to convince anyone to approve it without discussing the practicalities – in other words:

- How will you actually undertake your research (i.e., your methodology)?

- Is your research methodology appropriate given your research aims?

- Is your approach manageable given your constraints (time, money, etc.)?

While it’s generally not expected that you’ll have a fully fleshed-out methodology at the proposal stage, you’ll likely still need to provide a high-level overview of your research methodology . Here are some important questions you’ll need to address in your research proposal:

- Will you take a qualitative , quantitative or mixed -method approach?

- What sampling strategy will you adopt?

- How will you collect your data (e.g., interviews, surveys, etc)?

- How will you analyse your data (e.g., descriptive and inferential statistics , content analysis, discourse analysis, etc, .)?

- What potential limitations will your methodology carry?

So, be sure to give some thought to the practicalities of your research and have at least a basic methodological plan before you start writing up your proposal. If this all sounds rather intimidating, the video below provides a good introduction to research methodology and the key choices you’ll need to make.

How To Structure A Research Proposal

Now that we’ve covered the key points that need to be addressed in a proposal, you may be wondering, “ But how is a research proposal structured? “.

While the exact structure and format required for a research proposal differs from university to university, there are four “essential ingredients” that commonly make up the structure of a research proposal:

- A rich introduction and background to the proposed research

- An initial literature review covering the existing research

- An overview of the proposed research methodology

- A discussion regarding the practicalities (project plans, timelines, etc.)

In the video below, we unpack each of these four sections, step by step.

Research Proposal Examples/Samples

In the video below, we provide a detailed walkthrough of two successful research proposals (Master’s and PhD-level), as well as our popular free proposal template.

Proposal Writing FAQs

How long should a research proposal be.

This varies tremendously, depending on the university, the field of study (e.g., social sciences vs natural sciences), and the level of the degree (e.g. undergraduate, Masters or PhD) – so it’s always best to check with your university what their specific requirements are before you start planning your proposal.

As a rough guide, a formal research proposal at Masters-level often ranges between 2000-3000 words, while a PhD-level proposal can be far more detailed, ranging from 5000-8000 words. In some cases, a rough outline of the topic is all that’s needed, while in other cases, universities expect a very detailed proposal that essentially forms the first three chapters of the dissertation or thesis.

The takeaway – be sure to check with your institution before you start writing.

How do I choose a topic for my research proposal?

Finding a good research topic is a process that involves multiple steps. We cover the topic ideation process in this video post.

How do I write a literature review for my proposal?

While you typically won’t need a comprehensive literature review at the proposal stage, you still need to demonstrate that you’re familiar with the key literature and are able to synthesise it. We explain the literature review process here.

How do I create a timeline and budget for my proposal?

We explain how to craft a project plan/timeline and budget in Research Proposal Bootcamp .

Which referencing format should I use in my research proposal?

The expectations and requirements regarding formatting and referencing vary from institution to institution. Therefore, you’ll need to check this information with your university.

What common proposal writing mistakes do I need to look out for?

We’ve create a video post about some of the most common mistakes students make when writing a proposal – you can access that here . If you’re short on time, here’s a quick summary:

- The research topic is too broad (or just poorly articulated).

- The research aims, objectives and questions don’t align.

- The research topic is not well justified.

- The study has a weak theoretical foundation.

- The research design is not well articulated well enough.

- Poor writing and sloppy presentation.

- Poor project planning and risk management.

- Not following the university’s specific criteria.

Key Takeaways & Additional Resources

As you write up your research proposal, remember the all-important core purpose: to convince . Your research proposal needs to sell your study in terms of suitability and viability. So, focus on crafting a convincing narrative to ensure a strong proposal.

At the same time, pay close attention to your university’s requirements. While we’ve covered the essentials here, every institution has its own set of expectations and it’s essential that you follow these to maximise your chances of approval.

By the way, we’ve got plenty more resources to help you fast-track your research proposal. Here are some of our most popular resources to get you started:

- Proposal Writing 101 : A Introductory Webinar

- Research Proposal Bootcamp : The Ultimate Online Course

- Template : A basic template to help you craft your proposal

If you’re looking for 1-on-1 support with your research proposal, be sure to check out our private coaching service , where we hold your hand through the proposal development process (and the entire research journey), step by step.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Research Proposal Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

51 Comments

I truly enjoyed this video, as it was eye-opening to what I have to do in the preparation of preparing a Research proposal.

I would be interested in getting some coaching.

I real appreciate on your elaboration on how to develop research proposal,the video explains each steps clearly.

Thank you for the video. It really assisted me and my niece. I am a PhD candidate and she is an undergraduate student. It is at times, very difficult to guide a family member but with this video, my job is done.

In view of the above, I welcome more coaching.

Wonderful guidelines, thanks

This is very helpful. Would love to continue even as I prepare for starting my masters next year.

Thanks for the work done, the text was helpful to me

Bundle of thanks to you for the research proposal guide it was really good and useful if it is possible please send me the sample of research proposal

You’re most welcome. We don’t have any research proposals that we can share (the students own the intellectual property), but you might find our research proposal template useful: https://gradcoach.com/research-proposal-template/

Cheruiyot Moses Kipyegon

Thanks alot. It was an eye opener that came timely enough before my imminent proposal defense. Thanks, again

thank you very much your lesson is very interested may God be with you

I am an undergraduate student (First Degree) preparing to write my project,this video and explanation had shed more light to me thanks for your efforts keep it up.

Very useful. I am grateful.

this is a very a good guidance on research proposal, for sure i have learnt something

Wonderful guidelines for writing a research proposal, I am a student of m.phil( education), this guideline is suitable for me. Thanks

You’re welcome 🙂

Thank you, this was so helpful.

A really great and insightful video. It opened my eyes as to how to write a research paper. I would like to receive more guidance for writing my research paper from your esteemed faculty.

Thank you, great insights

Thank you, great insights, thank you so much, feeling edified

Wow thank you, great insights, thanks a lot

Thank you. This is a great insight. I am a student preparing for a PhD program. I am requested to write my Research Proposal as part of what I am required to submit before my unconditional admission. I am grateful having listened to this video which will go a long way in helping me to actually choose a topic of interest and not just any topic as well as to narrow down the topic and be specific about it. I indeed need more of this especially as am trying to choose a topic suitable for a DBA am about embarking on. Thank you once more. The video is indeed helpful.

Have learnt a lot just at the right time. Thank you so much.

thank you very much ,because have learn a lot things concerning research proposal and be blessed u for your time that you providing to help us

Hi. For my MSc medical education research, please evaluate this topic for me: Training Needs Assessment of Faculty in Medical Training Institutions in Kericho and Bomet Counties

I have really learnt a lot based on research proposal and it’s formulation

Thank you. I learn much from the proposal since it is applied

Your effort is much appreciated – you have good articulation.

You have good articulation.

I do applaud your simplified method of explaining the subject matter, which indeed has broaden my understanding of the subject matter. Definitely this would enable me writing a sellable research proposal.

This really helping

Great! I liked your tutoring on how to find a research topic and how to write a research proposal. Precise and concise. Thank you very much. Will certainly share this with my students. Research made simple indeed.

Thank you very much. I an now assist my students effectively.

Thank you very much. I can now assist my students effectively.

I need any research proposal

Thank you for these videos. I will need chapter by chapter assistance in writing my MSc dissertation

Very helpfull

the videos are very good and straight forward

thanks so much for this wonderful presentations, i really enjoyed it to the fullest wish to learn more from you

Thank you very much. I learned a lot from your lecture.

I really enjoy the in-depth knowledge on research proposal you have given. me. You have indeed broaden my understanding and skills. Thank you

interesting session this has equipped me with knowledge as i head for exams in an hour’s time, am sure i get A++

This article was most informative and easy to understand. I now have a good idea of how to write my research proposal.

Thank you very much.

Wow, this literature is very resourceful and interesting to read. I enjoyed it and I intend reading it every now then.

Thank you for the clarity

Thank you. Very helpful.

Thank you very much for this essential piece. I need 1o1 coaching, unfortunately, your service is not available in my country. Anyways, a very important eye-opener. I really enjoyed it. A thumb up to Gradcoach

What is JAM? Please explain.

Thank you so much for these videos. They are extremely helpful! God bless!

very very wonderful…

thank you for the video but i need a written example

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

11.2 Steps in Developing a Research Proposal

Learning objectives.

- Identify the steps in developing a research proposal.

- Choose a topic and formulate a research question and working thesis.

- Develop a research proposal.

Writing a good research paper takes time, thought, and effort. Although this assignment is challenging, it is manageable. Focusing on one step at a time will help you develop a thoughtful, informative, well-supported research paper.

Your first step is to choose a topic and then to develop research questions, a working thesis, and a written research proposal. Set aside adequate time for this part of the process. Fully exploring ideas will help you build a solid foundation for your paper.

Choosing a Topic

When you choose a topic for a research paper, you are making a major commitment. Your choice will help determine whether you enjoy the lengthy process of research and writing—and whether your final paper fulfills the assignment requirements. If you choose your topic hastily, you may later find it difficult to work with your topic. By taking your time and choosing carefully, you can ensure that this assignment is not only challenging but also rewarding.

Writers understand the importance of choosing a topic that fulfills the assignment requirements and fits the assignment’s purpose and audience. (For more information about purpose and audience, see Chapter 6 “Writing Paragraphs: Separating Ideas and Shaping Content” .) Choosing a topic that interests you is also crucial. You instructor may provide a list of suggested topics or ask that you develop a topic on your own. In either case, try to identify topics that genuinely interest you.

After identifying potential topic ideas, you will need to evaluate your ideas and choose one topic to pursue. Will you be able to find enough information about the topic? Can you develop a paper about this topic that presents and supports your original ideas? Is the topic too broad or too narrow for the scope of the assignment? If so, can you modify it so it is more manageable? You will ask these questions during this preliminary phase of the research process.

Identifying Potential Topics

Sometimes, your instructor may provide a list of suggested topics. If so, you may benefit from identifying several possibilities before committing to one idea. It is important to know how to narrow down your ideas into a concise, manageable thesis. You may also use the list as a starting point to help you identify additional, related topics. Discussing your ideas with your instructor will help ensure that you choose a manageable topic that fits the requirements of the assignment.

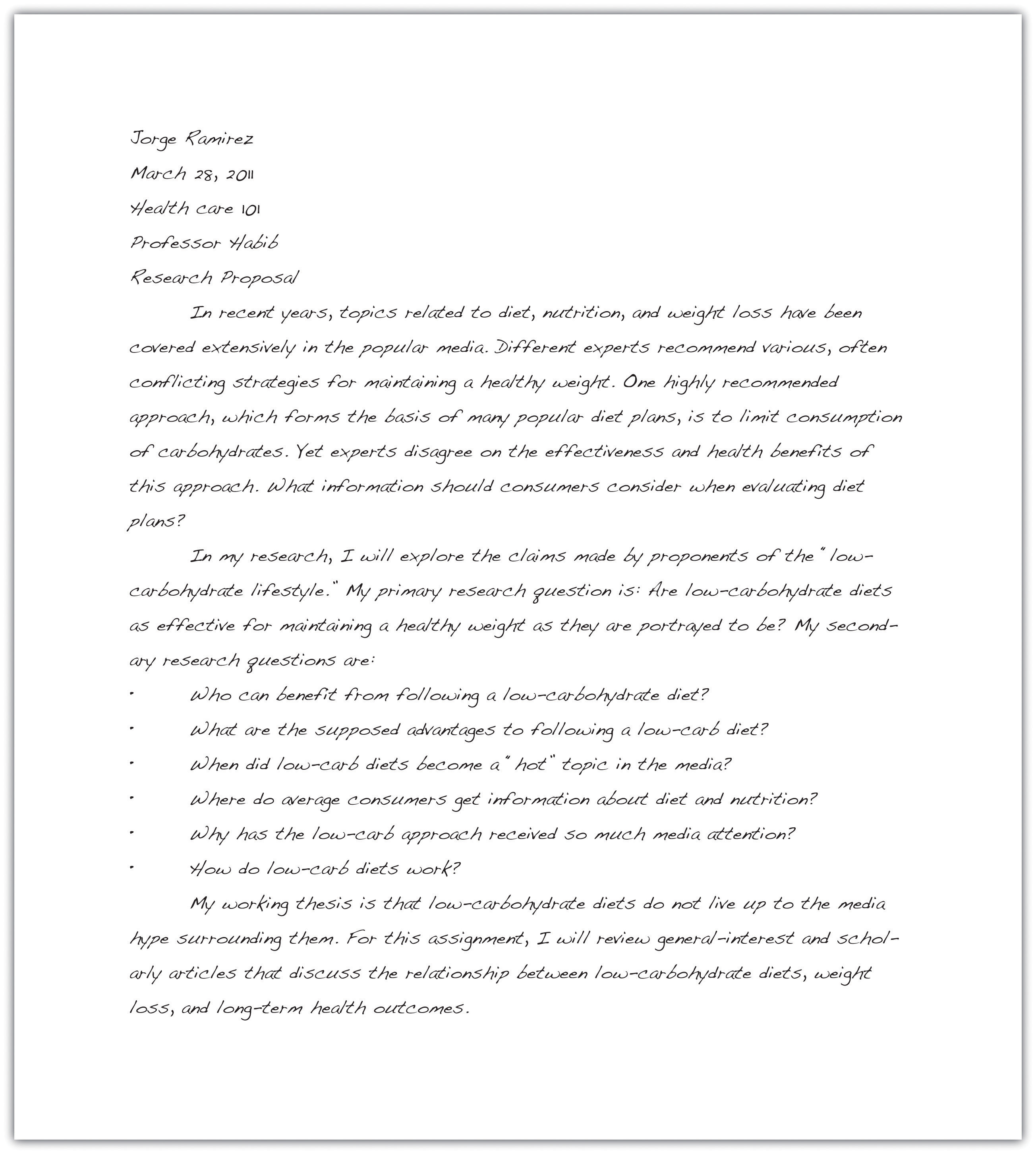

In this chapter, you will follow a writer named Jorge, who is studying health care administration, as he prepares a research paper. You will also plan, research, and draft your own research paper.

Jorge was assigned to write a research paper on health and the media for an introductory course in health care. Although a general topic was selected for the students, Jorge had to decide which specific issues interested him. He brainstormed a list of possibilities.

If you are writing a research paper for a specialized course, look back through your notes and course activities. Identify reading assignments and class discussions that especially engaged you. Doing so can help you identify topics to pursue.

- Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs) in the news

- Sexual education programs

- Hollywood and eating disorders

- Americans’ access to public health information

- Media portrayal of health care reform bill

- Depictions of drugs on television

- The effect of the Internet on mental health

- Popularized diets (such as low-carbohydrate diets)

- Fear of pandemics (bird flu, HINI, SARS)

- Electronic entertainment and obesity

- Advertisements for prescription drugs

- Public education and disease prevention

Set a timer for five minutes. Use brainstorming or idea mapping to create a list of topics you would be interested in researching for a paper about the influence of the Internet on social networking. Do you closely follow the media coverage of a particular website, such as Twitter? Would you like to learn more about a certain industry, such as online dating? Which social networking sites do you and your friends use? List as many ideas related to this topic as you can.

Narrowing Your Topic

Once you have a list of potential topics, you will need to choose one as the focus of your essay. You will also need to narrow your topic. Most writers find that the topics they listed during brainstorming or idea mapping are broad—too broad for the scope of the assignment. Working with an overly broad topic, such as sexual education programs or popularized diets, can be frustrating and overwhelming. Each topic has so many facets that it would be impossible to cover them all in a college research paper. However, more specific choices, such as the pros and cons of sexual education in kids’ television programs or the physical effects of the South Beach diet, are specific enough to write about without being too narrow to sustain an entire research paper.

A good research paper provides focused, in-depth information and analysis. If your topic is too broad, you will find it difficult to do more than skim the surface when you research it and write about it. Narrowing your focus is essential to making your topic manageable. To narrow your focus, explore your topic in writing, conduct preliminary research, and discuss both the topic and the research with others.

Exploring Your Topic in Writing

“How am I supposed to narrow my topic when I haven’t even begun researching yet?” In fact, you may already know more than you realize. Review your list and identify your top two or three topics. Set aside some time to explore each one through freewriting. (For more information about freewriting, see Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” .) Simply taking the time to focus on your topic may yield fresh angles.

Jorge knew that he was especially interested in the topic of diet fads, but he also knew that it was much too broad for his assignment. He used freewriting to explore his thoughts so he could narrow his topic. Read Jorge’s ideas.

Conducting Preliminary Research

Another way writers may focus a topic is to conduct preliminary research . Like freewriting, exploratory reading can help you identify interesting angles. Surfing the web and browsing through newspaper and magazine articles are good ways to start. Find out what people are saying about your topic on blogs and online discussion groups. Discussing your topic with others can also inspire you. Talk about your ideas with your classmates, your friends, or your instructor.

Jorge’s freewriting exercise helped him realize that the assigned topic of health and the media intersected with a few of his interests—diet, nutrition, and obesity. Preliminary online research and discussions with his classmates strengthened his impression that many people are confused or misled by media coverage of these subjects.

Jorge decided to focus his paper on a topic that had garnered a great deal of media attention—low-carbohydrate diets. He wanted to find out whether low-carbohydrate diets were as effective as their proponents claimed.

Writing at Work

At work, you may need to research a topic quickly to find general information. This information can be useful in understanding trends in a given industry or generating competition. For example, a company may research a competitor’s prices and use the information when pricing their own product. You may find it useful to skim a variety of reliable sources and take notes on your findings.

The reliability of online sources varies greatly. In this exploratory phase of your research, you do not need to evaluate sources as closely as you will later. However, use common sense as you refine your paper topic. If you read a fascinating blog comment that gives you a new idea for your paper, be sure to check out other, more reliable sources as well to make sure the idea is worth pursuing.

Review the list of topics you created in Note 11.18 “Exercise 1” and identify two or three topics you would like to explore further. For each of these topics, spend five to ten minutes writing about the topic without stopping. Then review your writing to identify possible areas of focus.

Set aside time to conduct preliminary research about your potential topics. Then choose a topic to pursue for your research paper.

Collaboration

Please share your topic list with a classmate. Select one or two topics on his or her list that you would like to learn more about and return it to him or her. Discuss why you found the topics interesting, and learn which of your topics your classmate selected and why.

A Plan for Research

Your freewriting and preliminary research have helped you choose a focused, manageable topic for your research paper. To work with your topic successfully, you will need to determine what exactly you want to learn about it—and later, what you want to say about it. Before you begin conducting in-depth research, you will further define your focus by developing a research question , a working thesis, and a research proposal.

Formulating a Research Question

In forming a research question, you are setting a goal for your research. Your main research question should be substantial enough to form the guiding principle of your paper—but focused enough to guide your research. A strong research question requires you not only to find information but also to put together different pieces of information, interpret and analyze them, and figure out what you think. As you consider potential research questions, ask yourself whether they would be too hard or too easy to answer.

To determine your research question, review the freewriting you completed earlier. Skim through books, articles, and websites and list the questions you have. (You may wish to use the 5WH strategy to help you formulate questions. See Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” for more information about 5WH questions.) Include simple, factual questions and more complex questions that would require analysis and interpretation. Determine your main question—the primary focus of your paper—and several subquestions that you will need to research to answer your main question.

Here are the research questions Jorge will use to focus his research. Notice that his main research question has no obvious, straightforward answer. Jorge will need to research his subquestions, which address narrower topics, to answer his main question.

Using the topic you selected in Note 11.24 “Exercise 2” , write your main research question and at least four to five subquestions. Check that your main research question is appropriately complex for your assignment.

Constructing a Working ThesIs

A working thesis concisely states a writer’s initial answer to the main research question. It does not merely state a fact or present a subjective opinion. Instead, it expresses a debatable idea or claim that you hope to prove through additional research. Your working thesis is called a working thesis for a reason—it is subject to change. As you learn more about your topic, you may change your thinking in light of your research findings. Let your working thesis serve as a guide to your research, but do not be afraid to modify it based on what you learn.

Jorge began his research with a strong point of view based on his preliminary writing and research. Read his working thesis statement, which presents the point he will argue. Notice how it states Jorge’s tentative answer to his research question.

One way to determine your working thesis is to consider how you would complete sentences such as I believe or My opinion is . However, keep in mind that academic writing generally does not use first-person pronouns. These statements are useful starting points, but formal research papers use an objective voice.

Write a working thesis statement that presents your preliminary answer to the research question you wrote in Note 11.27 “Exercise 3” . Check that your working thesis statement presents an idea or claim that could be supported or refuted by evidence from research.

Creating a Research Proposal

A research proposal is a brief document—no more than one typed page—that summarizes the preliminary work you have completed. Your purpose in writing it is to formalize your plan for research and present it to your instructor for feedback. In your research proposal, you will present your main research question, related subquestions, and working thesis. You will also briefly discuss the value of researching this topic and indicate how you plan to gather information.

When Jorge began drafting his research proposal, he realized that he had already created most of the pieces he needed. However, he knew he also had to explain how his research would be relevant to other future health care professionals. In addition, he wanted to form a general plan for doing the research and identifying potentially useful sources. Read Jorge’s research proposal.

Before you begin a new project at work, you may have to develop a project summary document that states the purpose of the project, explains why it would be a wise use of company resources, and briefly outlines the steps involved in completing the project. This type of document is similar to a research proposal. Both documents define and limit a project, explain its value, discuss how to proceed, and identify what resources you will use.

Writing Your Own Research Proposal

Now you may write your own research proposal, if you have not done so already. Follow the guidelines provided in this lesson.

Key Takeaways

- Developing a research proposal involves the following preliminary steps: identifying potential ideas, choosing ideas to explore further, choosing and narrowing a topic, formulating a research question, and developing a working thesis.

- A good topic for a research paper interests the writer and fulfills the requirements of the assignment.

- Defining and narrowing a topic helps writers conduct focused, in-depth research.

- Writers conduct preliminary research to identify possible topics and research questions and to develop a working thesis.

- A good research question interests readers, is neither too broad nor too narrow, and has no obvious answer.

- A good working thesis expresses a debatable idea or claim that can be supported with evidence from research.

- Writers create a research proposal to present their topic, main research question, subquestions, and working thesis to an instructor for approval or feedback.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

3.2 Types of proposals