Rational Planning Model

Evolution of different planning models

Different authors and scholars coined different planning theories which evolved over time. Planning theories are an attempt to refine the planning process so as to produce better plans. With more and more people working some of the well-known planning concepts like rational planning model, advocacy planning concept , collaborative planning theory , political economic model in urban planning , critical minimum efforts theory etc. emerged. Among these Rational Planning Model is considered to be most successful and even used today.

A brief history of Rational Planning Model

The rational planning model is the process of understanding a problem by establishing and evaluating planning criteria, formulation of alternatives and implementing them and finally monitoring the progress of the chosen alternatives. The rational planning model is central in the development of transport planning & modern planning. Similarly, rational decision-making model is a process of making decisions which are logically sound. This multi-step model and aims to be logical and follow the orderly path from problem identification through solution.

The RCM (Rational Comprehensive Model) for planning owes its origins to Enlightenment epistemology (Sandercock, 1998; Allmendinger, 2002), as it is centred on decisions and principles that are based on reason, logic and scientific facts with little or no emphasis on values and emotions. Due to its tendency towards scientific method and its decision-making process, Faludi has termed it ‘procedural planning theory’. He sees planning as a procedure and declares that “the planning theorist depends on first-hand experience, reflects upon it, and puts it into context” (Faludi, 1978:179). Therefore, the planner learns from experience and can define the correct method or procedure to follow to get the correct result. Meanwhile Sandercock (1998) refers to the rational comprehensive model as ‘technocratic planning’ due to its emphasis on technical expertise and skills and its steadfast belief that technology and social science can be used to solve our problems.

Related: Advocacy Planning Concept

Terms used in Rational Decision Model

- Goals – Goals are broad statements that we intend to achieve. They are quite general and abstract.

- Objectives – Objectives are more specific, measurable and clear as they help to progress towards the goals. They are the means to actually fulfil the goals.

- Targets – they are further specific and specify the time against which the actions need to be completed.

- Data – Data is raw, unorganized facts that need to be processed.

- Information – When data is processed, organized, structured or presented in a given context so as to make it useful, it is called Information.

- Model – A model is simply a schematic but precise description of the system using assumptions, which appears to fit its past behaviour and which can, therefore, be used, it is hoped, to predict the future

- Projections – Projections are usually carried out based on a number of alternative assumptions based on trends of growth and other linked factors like future policy of the government, attitude of people etc. They refer to the probable value of data in future.

- Estimate – Estimate refers to the past date. For example, suppose we wish to have population of India for 2009 today, which is not available, so we have to estimate it based on some previous available data of other years.

- Forecast – Forecast has an element of prediction into the near future using current data and sophisticated instruments. For instance, forecasting the weather in the next 24 hours.

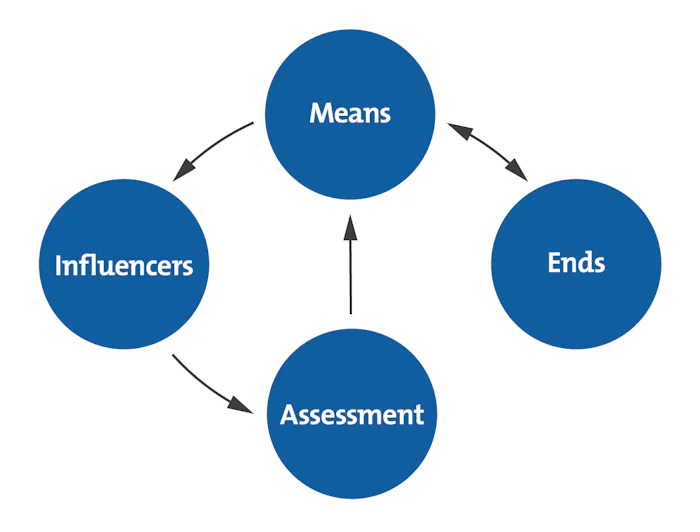

Stages of Rational Planning Model

Related: Collaborative Planning Theory

Criticism of Rational Planning Model

Critique of the Rational Comprehensive Planning Model: The RCM of planning has been the subject of numerous criticisms. Michael Thomas (1982:14, in Paris, 1982) criticised the RCM’s focus on means rather than ends and claimed that the model is “essentially ‘contentless’ in that it specifies thinking and acting procedures but does not investigate what is the content of these” (Thomas, 1982, p.14, in Paris 1982). The model is accused of being abstract “offering merely an extended definition of planning and not saying anything about how planning in practice operated or what its effects were” (Taylor 1998:96). Advocate planners argued that what was portrayed as the ‘Public interest’ in the RCM represented merely the interests of the privileged. They maintain that no common social interest exists and that the RCM neglects the interests of both the poor and nature (Campbell and Fainstein 2003).

The comprehensiveness of the model has also come under question by such critics as Lindblom (2003 in Campbell and Fainstein 2003) and Altshuler (1965), who argue that due to limited time and resources available for making a decision and exploring all alternative options it is practically impossible to be thoroughly comprehensive (Taylor 1998; Campbell and Fainstein 2003). It also requires an exceptional level of knowledge, analysis and organisational coordination to absorb and make sense of all the relevant information; planners may end up being more confused and thus less rational (Campbell and Fainstein 2003; Taylor 1998). Forester (1999:46) argues that even if planners are “quite alone” in making a rational decision, they will still do so in anticipation of certain other people’s opinions whom “they know they must finally come to some form of agreement”, and so the decision is neither fully comprehensive or rational in this sense.

Sandercock (1998:88) points out that in this model “the planner is indisputably ‘The knower’, relying strictly on ‘his’ professional expertise and objectivity to do what is best for an undifferentiated public”. Sandercock also highlights the point that the RCM “privileges scientific and technical knowledge over an array of equally important alternatives – experiential, intuitive, local knowledges” (Sandercock 1998:5). Knowledge gained from these practical and analytical modes by definition exclude those without professional training. This knowledge is based on technical jargons and is preferred to knowledge gained through other practices such as talking, listening, seeing, contemplating, and sharing.

Adding to the above limitations, there are a lot of assumptions, requirements without which the rational decision model is a failure. Therefore, they all have to be considered. The model assumes that we have or should or can obtain adequate information, both in terms of quality, quantity and accuracy. This applies to the situation as well as the alternative technical situations. It further assumes that you have or should or can obtain substantive knowledge of the cause and effect relationships relevant to the evaluation of the alternatives. In other words, it assumes that you have a thorough knowledge of all the alternatives and the consequences of the alternatives chosen. It further assumes that you can rank the alternatives and choose the best of it. The following are the limitations for the Rational Decision Making Model:

- requires a great deal of time

- requires great deal of information

- assumes rational, measurable criteria are available and agreed upon

- assumes accurate, stable and complete knowledge of all the alternatives, preferences, goals and consequences

- assumes a rational, reasonable, non – political world

What makes Rational Planning Model successful?

Ration decision model is considered to be most practical and apt for the needs of the planning process. Its based on the scientific reasoning which takes into account the use of modern technology and increased data collection. The data collected helps in establishing the rationale and thus helps in making a claim. Another characteristic is the preparation of alternative and then choosing best among the alternatives. Moreover as the process completes the last step for the first time addressed the problem of rigidity. Planning processes is often criticized for being too rigid. The feedback and monitoring provides the much-needed flexibility in the whole process so that timely modifications can be made to the plan.

About The Author

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

11.2: Understanding Decision Making

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 34537

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Learning Objectives

- Define decision making.

- Understand different types of decisions.

Decision making refers to making choices among alternative courses of action—which may also include inaction. While it can be argued that management is decision making, half of the decisions made by managers within organizations ultimately fail (Ireland & Miller, 2004; Nutt, 2002; Nutt, 1999). Therefore, increasing effectiveness in decision making is an important part of maximizing your effectiveness at work. This chapter will help you understand how to make decisions alone or in a group while avoiding common decision-making pitfalls.

Individuals throughout organizations use the information they gather to make a wide range of decisions. These decisions may affect the lives of others and change the course of an organization. For example, the decisions made by executives and consulting firms for Enron ultimately resulted in a $60 billion loss for investors, thousands of employees without jobs, and the loss of all employee retirement funds. But Sherron Watkins, a former Enron employee and now-famous whistleblower, uncovered the accounting problems and tried to enact change. Similarly, the decision made by firms to trade in mortgage-backed securities is having negative consequences for the entire economy in the United States. All parties involved in such outcomes made a decision, and everyone is now living with the consequences of those decisions.

Types of Decisions

Most discussions of decision making assume that only senior executives make decisions or that only senior executives’ decisions matter. This is a dangerous mistake.

Peter Drucker

Despite the far-reaching nature of the decisions in the previous example, not all decisions have major consequences or even require a lot of thought. For example, before you come to class, you make simple and habitual decisions such as what to wear, what to eat, and which route to take as you go to and from home and school. You probably do not spend much time on these mundane decisions. These types of straightforward decisions are termed programmed decisions , or decisions that occur frequently enough that we develop an automated response to them. The automated response we use to make these decisions is called the decision rule . For example, many restaurants face customer complaints as a routine part of doing business. Because complaints are a recurring problem, responding to them may become a programmed decision. The restaurant might enact a policy stating that every time they receive a valid customer complaint, the customer should receive a free dessert, which represents a decision rule.

On the other hand, unique and important decisions require conscious thinking, information gathering, and careful consideration of alternatives. These are called nonprogrammed decisions . For example, in 2005 McDonald’s Corporation became aware of the need to respond to growing customer concerns regarding the unhealthy aspects (high in fat and calories) of the food they sell. This is a nonprogrammed decision, because for several decades, customers of fast-food restaurants were more concerned with the taste and price of the food, rather than its healthiness. In response to this problem, McDonald’s decided to offer healthier alternatives such as the choice to substitute French fries in Happy Meals with apple slices and in 2007 they banned the use of trans fat at their restaurants.

A crisis situation also constitutes a nonprogrammed decision for companies. For example, the leadership of Nutrorim was facing a tough decision. They had recently introduced a new product, ChargeUp with Lipitrene, an improved version of their popular sports drink powder, ChargeUp. At some point, a phone call came from a state health department to inform them of 11 cases of gastrointestinal distress that might be related to their product, which led to a decision to recall ChargeUp. The decision was made without an investigation of the information. While this decision was conservative, it was made without a process that weighed the information. Two weeks later it became clear that the reported health problems were unrelated to Nutrorim’s product. In fact, all the cases were traced back to a contaminated health club juice bar. However, the damage to the brand and to the balance sheets was already done. This unfortunate decision caused Nutrorim to rethink the way decisions were made when under pressure. The company now gathers information to make informed choices even when time is of the essence (Garvin, 2006).

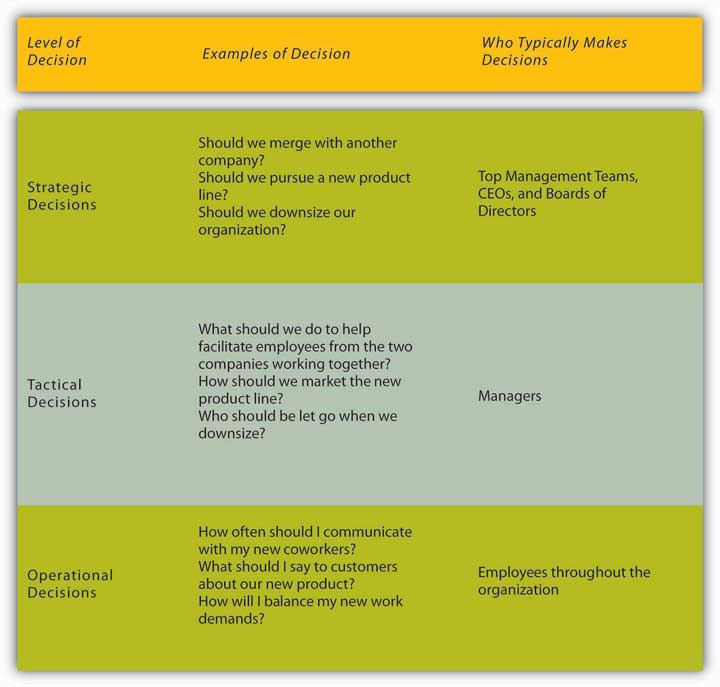

Decisions can be classified into three categories based on the level at which they occur. Strategic decisions set the course of an organization. Tactical decisions are decisions about how things will get done. Finally, operational decisions refer to decisions that employees make each day to make the organization run. For example, think about the restaurant that routinely offers a free dessert when a customer complaint is received. The owner of the restaurant made a strategic decision to have great customer service. The manager of the restaurant implemented the free dessert policy as a way to handle customer complaints, which is a tactical decision. Finally, the servers at the restaurant are making individual decisions each day by evaluating whether each customer complaint received is legitimate and warrants a free dessert.

Figure 11.4 Examples of Decisions Commonly Made Within Organizations

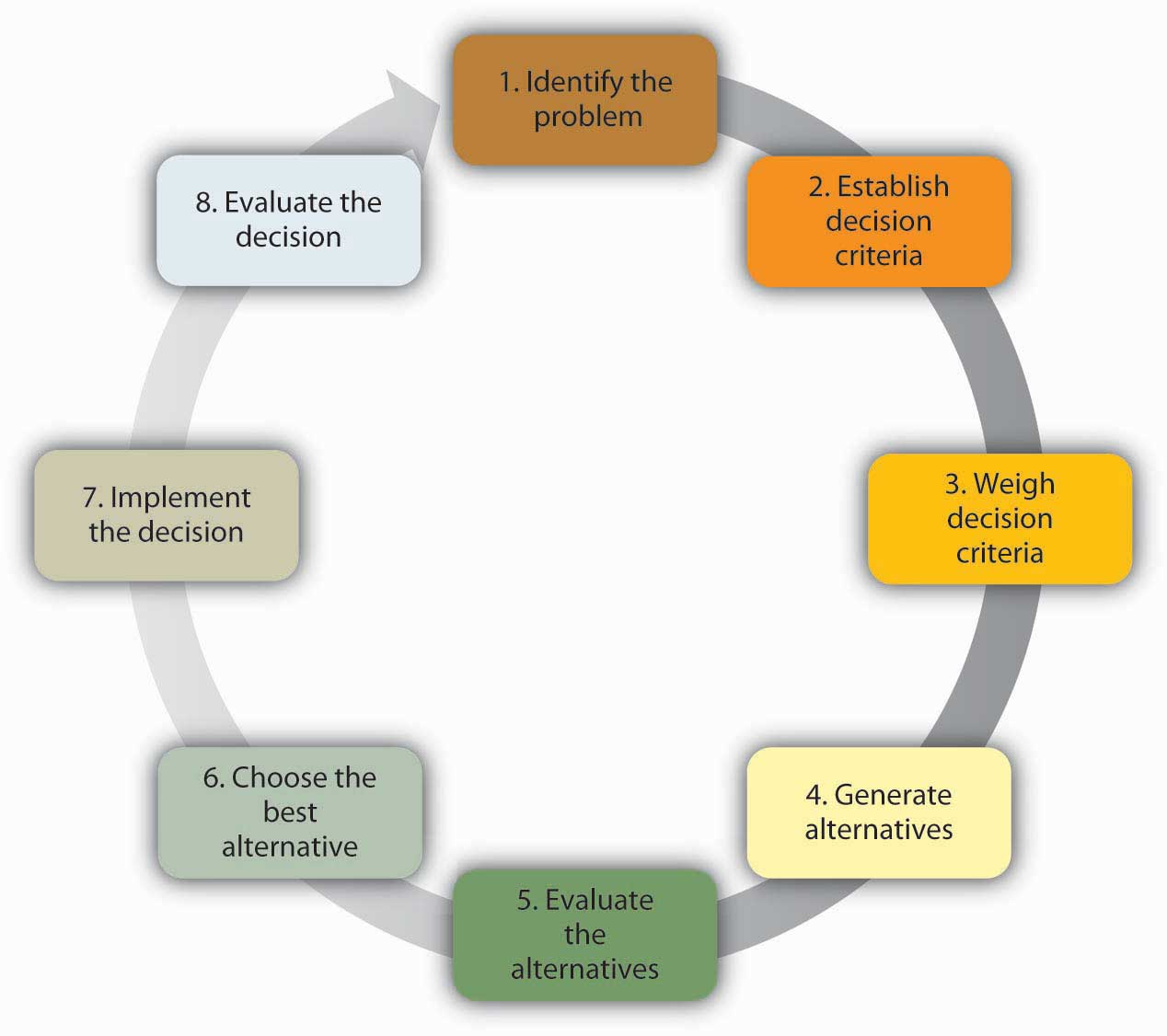

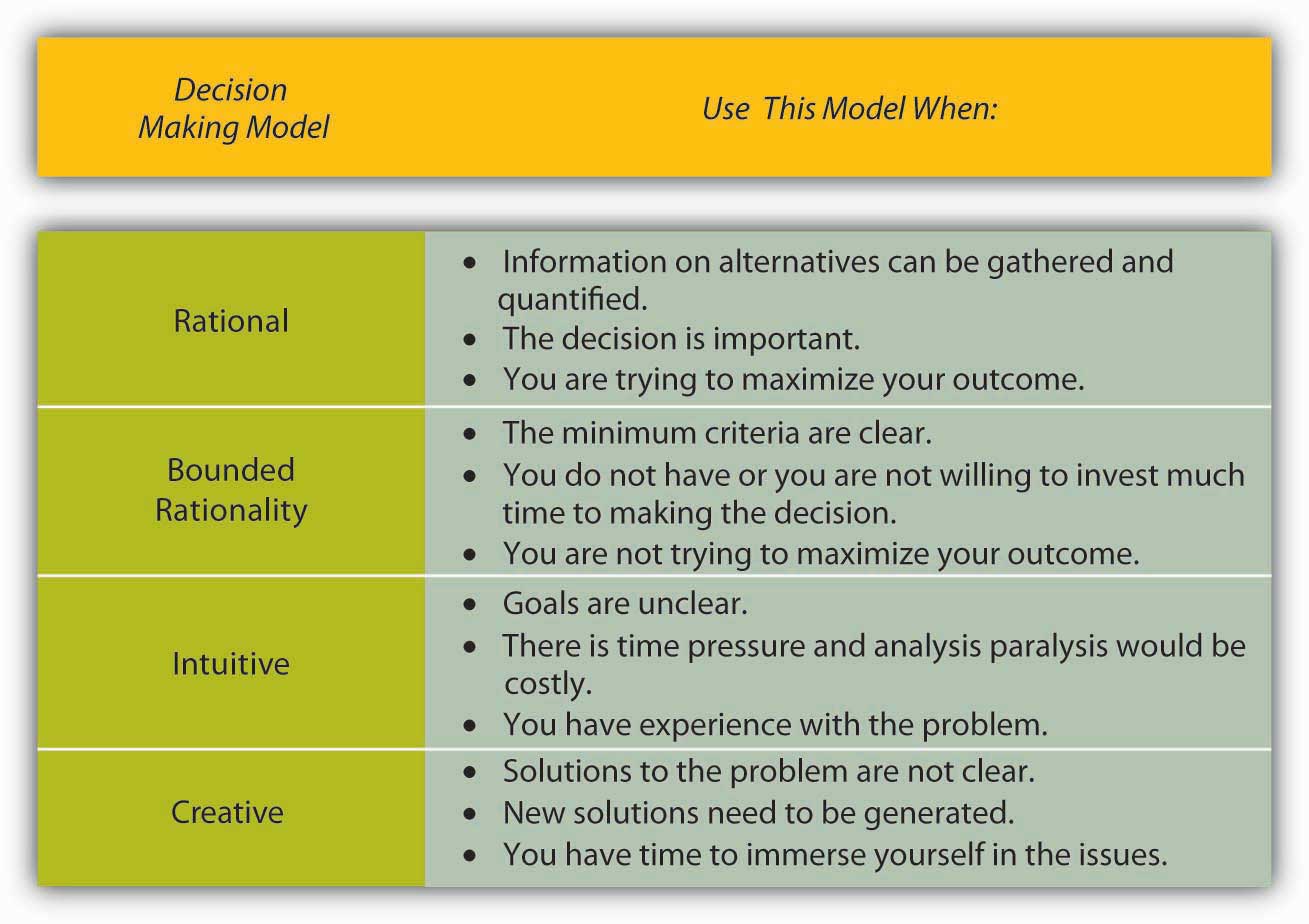

In this chapter we are going to discuss different decision-making models designed to understand and evaluate the effectiveness of nonprogrammed decisions. We will cover four decision-making approaches, starting with the rational decision-making model, moving to the bounded rationality decision-making model, the intuitive decision-making model, and ending with the creative decision-making model.

Making Rational Decisions

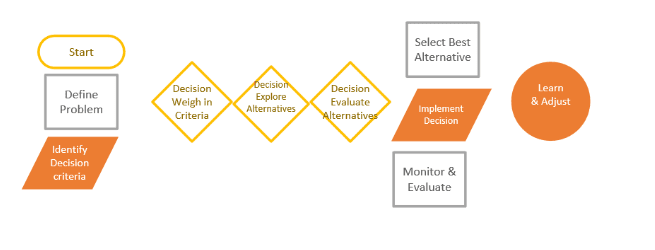

The rational decision-making model describes a series of steps that decision makers should consider if their goal is to maximize the quality of their outcomes. In other words, if you want to make sure that you make the best choice, going through the formal steps of the rational decision-making model may make sense.

Let’s imagine that your old, clunky car has broken down, and you have enough money saved for a substantial down payment on a new car. It will be the first major purchase of your life, and you want to make the right choice. The first step, therefore, has already been completed—we know that you want to buy a new car. Next, in step 2, you’ll need to decide which factors are important to you. How many passengers do you want to accommodate? How important is fuel economy to you? Is safety a major concern? You only have a certain amount of money saved, and you don’t want to take on too much debt, so price range is an important factor as well. If you know you want to have room for at least five adults, get at least 20 miles per gallon, drive a car with a strong safety rating, not spend more than $22,000 on the purchase, and like how it looks, you have identified the decision criteria . All the potential options for purchasing your car will be evaluated against these criteria. Before we can move too much further, you need to decide how important each factor is to your decision in step 3. If each is equally important, then there is no need to weigh them, but if you know that price and mpg are key factors, you might weigh them heavily and keep the other criteria with medium importance. Step 4 requires you to generate all alternatives about your options. Then, in step 5, you need to use this information to evaluate each alternative against the criteria you have established. You choose the best alternative (step 6), and then you would go out and buy your new car (step 7).

Of course, the outcome of this decision will influence the next decision made. That is where step 8 comes in. For example, if you purchase a car and have nothing but problems with it, you will be less likely to consider the same make and model when purchasing a car the next time.

While decision makers can get off track during any of these steps, research shows that searching for alternatives in the fourth step can be the most challenging and often leads to failure. In fact, one researcher found that no alternative generation occurred in 85% of the decisions he studied (Nutt, 1994). Conversely, successful managers know what they want at the outset of the decision-making process, set objectives for others to respond to, carry out an unrestricted search for solutions, get key people to participate, and avoid using their power to push their perspective (Nutt, 1998).

The rational decision-making model has important lessons for decision makers. First, when making a decision, you may want to make sure that you establish your decision criteria before you search for alternatives. This would prevent you from liking one option too much and setting your criteria accordingly. For example, let’s say you started browsing cars online before you generated your decision criteria. You may come across a car that you feel reflects your sense of style and you develop an emotional bond with the car. Then, because of your love for the particular car, you may say to yourself that the fuel economy of the car and the innovative braking system are the most important criteria. After purchasing it, you may realize that the car is too small for your friends to ride in the back seat, which was something you should have thought about. Setting criteria before you search for alternatives may prevent you from making such mistakes. Another advantage of the rational model is that it urges decision makers to generate all alternatives instead of only a few. By generating a large number of alternatives that cover a wide range of possibilities, you are unlikely to make a more effective decision that does not require sacrificing one criterion for the sake of another.

Despite all its benefits, you may have noticed that this decision-making model involves a number of unrealistic assumptions as well. It assumes that people completely understand the decision to be made, that they know all their available choices, that they have no perceptual biases, and that they want to make optimal decisions. Nobel Prize winning economist Herbert Simon observed that while the rational decision-making model may be a helpful device in aiding decision makers when working through problems, it doesn’t represent how decisions are frequently made within organizations. In fact, Simon argued that it didn’t even come close.

Think about how you make important decisions in your life. It is likely that you rarely sit down and complete all 8 of the steps in the rational decision-making model. For example, this model proposed that we should search for all possible alternatives before making a decision, but that process is time consuming, and individuals are often under time pressure to make decisions. Moreover, even if we had access to all the information that was available, it could be challenging to compare the pros and cons of each alternative and rank them according to our preferences. Anyone who has recently purchased a new laptop computer or cell phone can attest to the challenge of sorting through the different strengths and limitations of each brand and model and arriving at the solution that best meets particular needs. In fact, the availability of too much information can lead to analysis paralysis , in which more and more time is spent on gathering information and thinking about it, but no decisions actually get made. A senior executive at Hewlett-Packard Development Company LP admits that his company suffered from this spiral of analyzing things for too long to the point where data gathering led to “not making decisions, instead of us making decisions” (Zell, Glassman, & Duron, 2007). Moreover, you may not always be interested in reaching an optimal decision. For example, if you are looking to purchase a house, you may be willing and able to invest a great deal of time and energy to find your dream house, but if you are only looking for an apartment to rent for the academic year, you may be willing to take the first one that meets your criteria of being clean, close to campus, and within your price range.

Making “Good Enough” Decisions

The bounded rationality model of decision making recognizes the limitations of our decision-making processes. According to this model, individuals knowingly limit their options to a manageable set and choose the first acceptable alternative without conducting an exhaustive search for alternatives. An important part of the bounded rationality approach is the tendency to satisfice (a term coined by Herbert Simon from satisfy and suffice ), which refers to accepting the first alternative that meets your minimum criteria. For example, many college graduates do not conduct a national or international search for potential job openings. Instead, they focus their search on a limited geographic area, and they tend to accept the first offer in their chosen area, even if it may not be the ideal job situation. Satisficing is similar to rational decision making. The main difference is that rather than choosing the best option and maximizing the potential outcome, the decision maker saves cognitive time and effort by accepting the first alternative that meets the minimum threshold.

Making Intuitive Decisions

The intuitive decision-making model has emerged as an alternative to other decision making processes. This model refers to arriving at decisions without conscious reasoning. A total of 89% of managers surveyed admitted to using intuition to make decisions at least sometimes and 59% said they used intuition often (Burke & Miller, 1999). Managers make decisions under challenging circumstances, including time pressures, constraints, a great deal of uncertainty, changing conditions, and highly visible and high-stakes outcomes. Thus, it makes sense that they would not have the time to use the rational decision-making model. Yet when CEOs, financial analysts, and health care workers are asked about the critical decisions they make, seldom do they attribute success to luck. To an outside observer, it may seem like they are making guesses as to the course of action to take, but it turns out that experts systematically make decisions using a different model than was earlier suspected. Research on life-or-death decisions made by fire chiefs, pilots, and nurses finds that experts do not choose among a list of well thought out alternatives. They don’t decide between two or three options and choose the best one. Instead, they consider only one option at a time. The intuitive decision-making model argues that in a given situation, experts making decisions scan the environment for cues to recognize patterns (Breen, 2000; Klein, 2003; Salas & Klein, 2001). Once a pattern is recognized, they can play a potential course of action through to its outcome based on their prior experience. Thanks to training, experience, and knowledge, these decision makers have an idea of how well a given solution may work. If they run through the mental model and find that the solution will not work, they alter the solution before setting it into action. If it still is not deemed a workable solution, it is discarded as an option, and a new idea is tested until a workable solution is found. Once a viable course of action is identified, the decision maker puts the solution into motion. The key point is that only one choice is considered at a time. Novices are not able to make effective decisions this way, because they do not have enough prior experience to draw upon.

Making Creative Decisions

In addition to the rational decision making, bounded rationality, and intuitive decision-making models, creative decision making is a vital part of being an effective decision maker. Creativity is the generation of new, imaginative ideas. With the flattening of organizations and intense competition among companies, individuals and organizations are driven to be creative in decisions ranging from cutting costs to generating new ways of doing business. Please note that, while creativity is the first step in the innovation process, creativity and innovation are not the same thing. Innovation begins with creative ideas, but it also involves realistic planning and follow-through. Innovations such as 3M’s Clearview Window Tinting grow out of a creative decision-making process about what may or may not work to solve real-world problems.

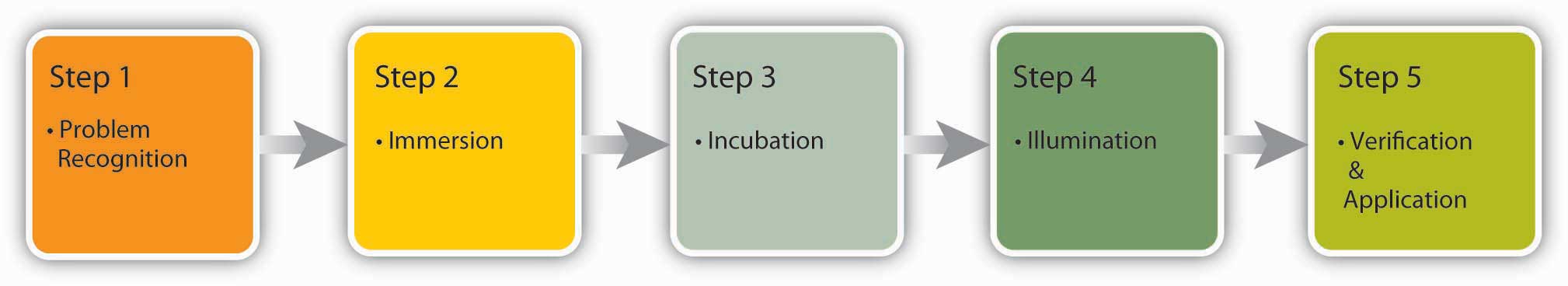

The five steps to creative decision making are similar to the previous decision-making models in some keys ways. All the models include problem identification, which is the step in which the need for problem solving becomes apparent. If you do not recognize that you have a problem, it is impossible to solve it. Immersion is the step in which the decision maker consciously thinks about the problem and gathers information. A key to success in creative decision making is having or acquiring expertise in the area being studied. Then, incubation occurs. During incubation, the individual sets the problem aside and does not think about it for a while. At this time, the brain is actually working on the problem unconsciously. Then comes illumination, or the insight moment when the solution to the problem becomes apparent to the person, sometimes when it is least expected. This sudden insight is the “eureka” moment, similar to what happened to the ancient Greek inventor Archimedes, who found a solution to the problem he was working on while taking a bath. Finally, the verification and application stage happens when the decision maker consciously verifies the feasibility of the solution and implements the decision.

A NASA scientist describes his decision-making process leading to a creative outcome as follows: He had been trying to figure out a better way to de-ice planes to make the process faster and safer. After recognizing the problem, he immersed himself in the literature to understand all the options, and he worked on the problem for months trying to figure out a solution. It was not until he was sitting outside a McDonald’s restaurant with his grandchildren that it dawned on him. The golden arches of the M of the McDonald’s logo inspired his solution—he would design the de-icer as a series of Ms. [1] This represented the illumination stage. After he tested and verified his creative solution, he was done with that problem, except to reflect on the outcome and process.

How Do You Know If Your Decision-Making Process Is Creative?

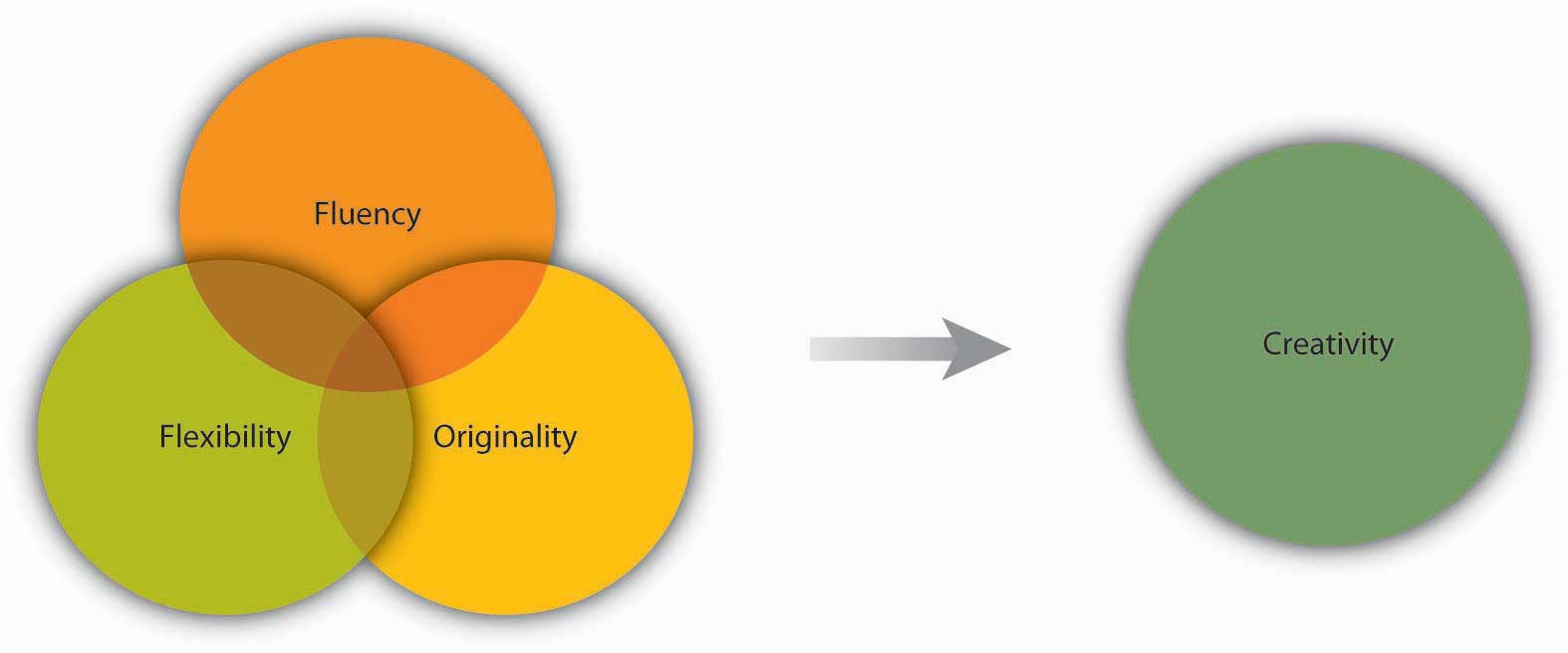

Researchers focus on three factors to evaluate the level of creativity in the decision-making process. Fluency refers to the number of ideas a person is able to generate. Flexibility refers to how different the ideas are from one another. If you are able to generate several distinct solutions to a problem, your decision-making process is high on flexibility. Originality refers to how unique a person’s ideas are. You might say that Reed Hastings, founder and CEO of Netflix Inc. is a pretty creative person. His decision-making process shows at least two elements of creativity. We do not know exactly how many ideas he had over the course of his career, but his ideas are fairly different from each other. After teaching math in Africa with the Peace Corps, Hastings was accepted at Stanford, where he earned a master’s degree in computer science. Soon after starting work at a software company, he invented a successful debugging tool, which led to his founding of the computer troubleshooting company Pure Software LLC in 1991. After a merger and the subsequent sale of the resulting company in 1997, Hastings founded Netflix, which revolutionized the DVD rental business with online rentals delivered through the mail with no late fees. In 2007, Hastings was elected to Microsoft’s board of directors. As you can see, his ideas are high in originality and flexibility (Conlin, 2007).

Some experts have proposed that creativity occurs as an interaction among three factors: people’s personality traits (openness to experience, risk taking), their attributes (expertise, imagination, motivation), and the situational context (encouragement from others, time pressure, physical structures) (Amabile, 1988; Amabile et al., 1996; Ford & Gioia, 2000; Tierney, Farmer, & Graen, 1999; Woodman, Sawyer, & Griffin, 1993). For example, research shows that individuals who are open to experience, less conscientious, more self-accepting, and more impulsive tend to be more creative (Feist, 1998).

OB Toolbox: Ideas for Enhancing Organizational Creativity

- Diversify your team to give them more inputs to build on and more opportunities to create functional conflict while avoiding personal conflict.

- Change group membership to stimulate new ideas and new interaction patterns.

- Leaderless teams can allow teams freedom to create without trying to please anyone up front.

- Engage in brainstorming to generate ideas. Remember to set a high goal for the number of ideas the group should come up with, encourage wild ideas, and take brainwriting breaks.

- Use the nominal group technique (see Tools and Techniques for Making Better Decisions below) in person or electronically to avoid some common group process pitfalls. Consider anonymous feedback as well.

- Use analogies to envision problems and solutions.

- Challenge teams so that they are engaged but not overwhelmed.

- Let people decide how to achieve goals , rather than telling them what goals to achieve.

- Support and celebrate creativity even when it leads to a mistake. Be sure to set up processes to learn from mistakes as well.

- Role model creative behavior.

- Institute organizational memory so that individuals do not spend time on routine tasks.

- Build a physical space conducive to creativity that is playful and humorous—this is a place where ideas can thrive.

- Incorporate creative behavior into the performance appraisal process.

Sources: Adapted from ideas in Amabile, T. M. (1998). How to kill creativity. Harvard Business Review , 76 , 76–87; Gundry, L. K., Kickul, J. R., & Prather, C. W. (1994). Building the creative organization. Organizational Dynamics , 22 , 22–37; Keith, N., & Frese, M. (2008). Effectiveness of error management training: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology , 93 , 59–69. Pearsall, M. J., Ellis, A. P. J., & Evans, J. M. (2008). Unlocking the effects of gender faultlines on team creativity: Is activation the key? Journal of Applied Psychology , 93 , 225–234. Thompson, L. (2003). Improving the creativity of organizational work groups. Academy of Management Executive , 17 , 96–109.

There are many techniques available that enhance and improve creativity. Linus Pauling, the Nobel Prize winner who popularized the idea that vitamin C could help strengthen the immune system, said, “The best way to have a good idea is to have a lot of ideas.” [2] One popular method of generating ideas is to use brainstorming. Brainstorming is a group process of generating ideas that follow a set of guidelines, including no criticism of ideas during the brainstorming process, the idea that no suggestion is too crazy, and building on other ideas (piggybacking). Research shows that the quantity of ideas actually leads to better idea quality in the end, so setting high idea quotas , in which the group must reach a set number of ideas before they are done, is recommended to avoid process loss and maximize the effectiveness of brainstorming. Another unique aspect of brainstorming is that since the variety of backgrounds and approaches give the group more to draw upon, the more people are included in the process, the better the decision outcome will be. A variation of brainstorming is wildstorming , in which the group focuses on ideas that are impossible and then imagines what would need to happen to make them possible (Scott, Leritz, & Mumford, 2004).

Figure 11.8

Which decision-making model should I use?

Key Takeaways

Decision making is choosing among alternative courses of action, including inaction. There are different types of decisions ranging from automatic, programmed decisions to more intensive nonprogrammed decisions. Structured decision-making processes include rational, bounded rationality, intuitive, and creative decision making. Each of these can be useful, depending on the circumstances and the problem that needs to be solved.

- What do you see as the main difference between a successful and an unsuccessful decision? How much does luck versus skill have to do with it? How much time needs to pass to know if a decision is successful or not?

- Research has shown that over half of the decisions made within organizations fail. Does this surprise you? Why or why not?

- Have you used the rational decision-making model to make a decision? What was the context? How well did the model work?

- Share an example of a decision in which you used satisficing. Were you happy with the outcome? Why or why not? When would you be most likely to engage in satisficing?

- Do you think intuition is respected as a decision-making style? Do you think it should be? Why or why not?

Amabile, T. M. (1988). A model of creativity and innovation in organizations. In B. M. Staw & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior, vol. 10 (pp. 123–167) Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Amabile, T. M., Conti, R., Coon, H., Lazenby, J., & Herron, M. (1996). Assessing the work environment for creativity. Academy of Management Journal , 39 , 1154–1184.

Breen, B. (2000, August). What’s your intuition? Fast Company , 290.

Burke, L. A., & Miller, M. K. (1999). Taking the mystery out of intuitive decision making. Academy of Management Executive , 13 , 91–98.

Conlin, M. (2007, September 14). Netflix: Recruiting and retaining the best talent. Business Week Online . Retrieved March 1, 2008, from http://www.businessweek.com/managing/content/sep2007/ca20070913_564868.htm?campaign_id=rss_null .

Feist, G. J. (1998). A meta-analysis of personality in scientific and artistic creativity. Personality and Social Psychology Review , 2 , 290–309.

Ford, C. M., & Gioia, D. A. (2000). Factors influencing creativity in the domain of managerial decision making. Journal of Management , 26 , 705–732.

Garvin, D. A. (2006, January). All the wrong moves. Harvard Business Review , 84 , 18–23.

Ireland, R. D., & Miller, C. C. (2004). Decision making and firm success. Academy of Management Executive , 18 , 8–12.

Klein, G. (2003). Intuition at work . New York: Doubleday.

Nutt, P. C. (1994). Types of organizational decision processes. Administrative Science Quarterly , 29 , 414–550.

Nutt, P. C. (1998). Surprising but true: Half the decisions in organizations fail. Academy of Management Executive , 13 , 75–90.

Nutt, P. C. (1999). Surprising but true: Half the decisions in organizations fail. Academy of Management Executive , 13 , 75–90.

Nutt, P. C. (2002). Why decisions fail . San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Salas, E., & Klein, G. (2001). Linking expertise and naturalistic decision making . Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Scott, G., Leritz, L. E., & Mumford, M. D. (2004). The effectiveness of creativity training: A quantitative review. Creativity Research Journal , 16 , 361–388.

Tierney, P., Farmer, S. M., & Graen, G. B. (1999). An examination of leadership and employee creativity: The relevance of traits and relationships. Personnel Psychology , 52 , 591–620.

Woodman, R. W., Sawyer, J. E., & Griffin, R. W. (1993). Toward a theory of organizational creativity. Academy of Management Review , 18 , 293–321.

Zell, D. M., Glassman, A. M., & Duron, S. A. (2007). Strategic management in turbulent times: The short and glorious history of accelerated decision making at Hewlett-Packard. Organizational Dynamics , 36 , 93–104.

- In person interview conducted by author at Ames Research Center, Mountain View, CA, 1990. ↵

- Quote retrieved May 1, 2008, from http://www.whatquote.com/quotes/linus-pauling/250801-the-best-way-to-have.htm . ↵

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

11.3 Understanding Decision Making

Learning objectives.

- Define decision making.

- Understand different types of decisions.

What Is Decision Making?

Decision making refers to making choices among alternative courses of action—which may also include inaction. While it can be argued that management is decision making, half of the decisions made by managers within organizations fail (Ireland & Miller, 2004; Nutt, 2002; Nutt, 1999). Therefore, increasing effectiveness in decision making is an important part of maximizing your effectiveness at work. This chapter will help you understand how to make decisions alone or in a group while avoiding common decision-making traps.

Individuals throughout organizations use the information they gather to make a wide range of decisions. These decisions may affect the lives of others and change the course of an organization. For example, the decisions made by executives and consulting firms for Enron ultimately resulted in a $60 billion loss for investors, thousands of employees without jobs, and the loss of all employee retirement funds. But Sherron Watkins, a former Enron employee and now-famous whistleblower, uncovered the accounting problems and tried to enact change. Similarly, the decisions made by firms to trade in mortgage-backed securities is having negative consequences for the entire U.S. economy. Each of these people made a decision, and each person, as well as others, is now living with the consequences of his or her decisions.

Because many decisions involve an ethical component, one of the most important considerations in management is whether the decisions you are making as an employee or manager are ethical. Here are some basic questions you can ask yourself to assess the ethics of a decision (Blanchard & Peale, 1988).

- Is this decision fair?

- Will I feel better or worse about myself after I make this decision?

- Does this decision break any organizational rules?

- Does this decision break any laws?

- How would I feel if this decision was broadcast on the news?

Types of Decisions

Despite the far-reaching nature of the decisions in the previous example, not all decisions have major consequences or even require a lot of thought. For example, before you come to class, you make simple and habitual decisions such as what to wear, what to eat, and which route to take as you go to and from home and school. You probably do not spend much time on these mundane decisions. These types of straightforward decisions are termed programmed decisions; these are decisions that occur frequently enough that we develop an automated response to them. The automated response we use to make these decisions is called the decision rule . For example, many restaurants face customer complaints as a routine part of doing business. Because this is a recurring problem for restaurants, it may be regarded as a programmed decision. To deal with this problem, the restaurant might have a policy stating that every time they receive a valid customer complaint, the customer should receive a free dessert, which represents a decision rule. Making strategic, tactical, and operational decisions is an integral part of the planning function in the P-O-L-C (planning-organizing-leading-controlling) model.

However, decisions that are unique and important require conscious thinking, information gathering, and careful consideration of alternatives. These are called nonprogrammed decisions . For example, in 2005, McDonald’s became aware of a need to respond to growing customer concerns regarding foods high in fat and calories. This is a nonprogrammed decision because for several decades, customers of fast-food restaurants were more concerned with the taste and price of the food, rather than the healthiness. In response, McDonald’s decided to offer healthier alternatives, such as substituting apple slices in Happy Meals for French fries and discontinuing the use of trans fats. A crisis situation also constitutes a nonprogrammed decision for companies. For example, the leadership of Nutrorim was facing a tough decision. They had recently introduced a new product, ChargeUp with Lipitrene, an improved version of their popular sports drink powder, ChargeUp. But a phone call came from a state health department to inform them that several cases of gastrointestinal distress had been reported after people consumed the new product. Nutrorim decided to recall ChargeUp with Lipitrene immediately. Two weeks later, it became clear that the gastrointestinal problems were unrelated to ChargeUp with Lipitrene. However, the damage to the brand and to the balance sheets was already done. This unfortunate decision caused Nutrorim to rethink the way decisions were made under pressure so that they now gather information to make informed choices even when time is of the essence (Garvin, 2006).

Figure 11.5

To ensure consistency around the globe such as at this St. Petersburg, Russia, location, McDonald’s trains all restaurant managers (over 65,000 so far) at Hamburger University where they take the equivalent of two years of college courses and learn how to make decisions. The curriculum is taught in 28 languages.

Wikimedia Commons – McDonalds in St Petersburg 2004 – CC BY-SA 1.0.

Decision making can also be classified into three categories based on the level at which they occur. Strategic decisions set the course of organization. Tactical decisions are decisions about how things will get done. Finally, operational decisions are decisions that employees make each day to run the organization. For example, remember the restaurant that routinely offers a free dessert when a customer complaint is received. The owner of the restaurant made a strategic decision to have great customer service. The manager of the restaurant implemented the free dessert policy as a way to handle customer complaints, which is a tactical decision. And, the servers at the restaurant are making individual decisions each day evaluating whether each customer complaint received is legitimate to warrant a free dessert.

Figure 11.6 Decisions Commonly Made within Organizations

In this chapter, we are going to discuss different decision-making models designed to understand and evaluate the effectiveness of nonprogrammed decisions. We will cover four decision-making approaches starting with the rational decision-making model, moving to the bounded rationality decision-making model, the intuitive decision-making model, and ending with the creative decision-making model.

Making Rational Decisions

The rational decision-making model describes a series of steps that decision makers should consider if their goal is to maximize the quality of their outcomes. In other words, if you want to make sure you make the best choice, going through the formal steps of the rational decision-making model may make sense.

Let’s imagine that your old, clunky car has broken down and you have enough money saved for a substantial down payment on a new car. It is the first major purchase of your life, and you want to make the right choice. The first step, therefore, has already been completed—we know that you want to buy a new car. Next, in step 2, you’ll need to decide which factors are important to you. How many passengers do you want to accommodate? How important is fuel economy to you? Is safety a major concern? You only have a certain amount of money saved, and you don’t want to take on too much debt, so price range is an important factor as well. If you know you want to have room for at least five adults, get at least 20 miles per gallon, drive a car with a strong safety rating, not spend more than $22,000 on the purchase, and like how it looks, you’ve identified the decision criteria. All of the potential options for purchasing your car will be evaluated against these criteria.

Figure 11.7

Using the rational decision-making model to make major purchases can help avoid making poor choices.

Lars Plougmann – Headshift business card discussion – CC BY-SA 2.0.

Before we can move too much further, you need to decide how important each factor is to your decision in step 3. If each is equally important, then there is no need to weight them, but if you know that price and gas mileage are key factors, you might weight them heavily and keep the other criteria with medium importance. Step 4 requires you to generate all alternatives about your options. Then, in step 5, you need to use this information to evaluate each alternative against the criteria you have established. You choose the best alternative (step 6) and you go out and buy your new car (step 7).

Of course, the outcome of this decision will be related to the next decision made; that is where the evaluation in step 8 comes in. For example, if you purchase a car but have nothing but problems with it, you are unlikely to consider the same make and model in purchasing another car the next time!

Figure 11.8 Steps in the Rational Decision-Making Model

While decision makers can get off track during any of these steps, research shows that limiting the search for alternatives in the fourth step can be the most challenging and lead to failure. In fact, one researcher found that no alternative generation occurred in 85% of the decisions studied (Nutt, 1994). Conversely, successful managers are clear about what they want at the outset of the decision-making process, set objectives for others to respond to, carry out an unrestricted search for solutions, get key people to participate, and avoid using their power to push their perspective (Nutt, 1998).

The rational decision-making model has important lessons for decision makers. First, when making a decision you may want to make sure that you establish your decision criteria before you search for all alternatives. This would prevent you from liking one option too much and setting your criteria accordingly. For example, let’s say you started browsing for cars before you decided your decision criteria. You may come across a car that you think really reflects your sense of style and make an emotional bond with the car. Then, because of your love for this car, you may say to yourself that the fuel economy of the car and the innovative braking system are the most important criteria. After purchasing it, you may realize that the car is too small for all of your friends to ride in the back seat when you and your brother are sitting in front, which was something you should have thought about! Setting criteria before you search for alternatives may prevent you from making such mistakes. Another advantage of the rational model is that it urges decision makers to generate all alternatives instead of only a few. By generating a large number of alternatives that cover a wide range of possibilities, you are likely to make a more effective decision in which you do not need to sacrifice one criterion for the sake of another.

Despite all its benefits, you may have noticed that this decision-making model involves a number of unrealistic assumptions. It assumes that people understand what decision is to be made, that they know all their available choices, that they have no perceptual biases, and that they want to make optimal decisions. Nobel Prize–winning economist Herbert Simon observed that while the rational decision-making model may be a helpful tool for working through problems, it doesn’t represent how decisions are frequently made within organizations. In fact, Simon argued that it didn’t even come close!

Think about how you make important decisions in your life. Our guess is that you rarely sit down and complete all eight steps in the rational decision-making model. For example, this model proposed that we should search for all possible alternatives before making a decision, but this can be time consuming and individuals are often under time pressure to make decisions. Moreover, even if we had access to all the information, it could be challenging to compare the pros and cons of each alternative and rank them according to our preferences. Anyone who has recently purchased a new laptop computer or cell phone can attest to the challenge of sorting through the different strengths and limitations of each brand, model, and plans offered for support and arriving at the solution that best meets their needs.

In fact, the availability of too much information can lead to analysis paralysis , where more and more time is spent on gathering information and thinking about it, but no decisions actually get made. A senior executive at Hewlett-Packard admits that his company suffered from this spiral of analyzing things for too long to the point where data gathering led to “not making decisions, instead of us making decisions (Zell, et. al., 2007).” Moreover, you may not always be interested in reaching an optimal decision. For example, if you are looking to purchase a house, you may be willing and able to invest a great deal of time and energy to find your dream house, but if you are looking for an apartment to rent for the academic year, you may be willing to take the first one that meets your criteria of being clean, close to campus, and within your price range.

Making “Good Enough” Decisions

The bounded rationality model of decision making recognizes the limitations of our decision-making processes. According to this model, individuals knowingly limit their options to a manageable set and choose the best alternative without conducting an exhaustive search for alternatives. An important part of the bounded rationality approach is the tendency to satisfice , which refers to accepting the first alternative that meets your minimum criteria. For example, many college graduates do not conduct a national or international search for potential job openings; instead, they focus their search on a limited geographic area and tend to accept the first offer in their chosen area, even if it may not be the ideal job situation. Satisficing is similar to rational decision making, but it differs in that rather than choosing the best choice and maximizing the potential outcome, the decision maker saves time and effort by accepting the first alternative that meets the minimum threshold.

Making Intuitive Decisions

The intuitive decision-making model has emerged as an important decision-making model. It refers to arriving at decisions without conscious reasoning. Eighty-nine percent of managers surveyed admitted to using intuition to make decisions at least sometimes, and 59% said they used intuition often (Burke & Miller, 1999). When we recognize that managers often need to make decisions under challenging circumstances with time pressures, constraints, a great deal of uncertainty, highly visible and high-stakes outcomes, and within changing conditions, it makes sense that they would not have the time to formally work through all the steps of the rational decision-making model. Yet when CEOs, financial analysts, and healthcare workers are asked about the critical decisions they make, seldom do they attribute success to luck. To an outside observer, it may seem like they are making guesses as to the course of action to take, but it turns out that they are systematically making decisions using a different model than was earlier suspected. Research on life-or-death decisions made by fire chiefs, pilots, and nurses finds that these experts do not choose among a list of well-thought-out alternatives. They don’t decide between two or three options and choose the best one. Instead, they consider only one option at a time. The intuitive decision-making model argues that, in a given situation, experts making decisions scan the environment for cues to recognize patterns (Breen, 2000; Klein, 2003; Salas & Klein, 2001). Once a pattern is recognized, they can play a potential course of action through to its outcome based on their prior experience. Due to training, experience, and knowledge, these decision makers have an idea of how well a given solution may work. If they run through the mental model and find that the solution will not work, they alter the solution and retest it before setting it into action. If it still is not deemed a workable solution, it is discarded as an option and a new idea is tested until a workable solution is found. Once a viable course of action is identified, the decision maker puts the solution into motion. The key point is that only one choice is considered at a time. Novices are not able to make effective decisions this way because they do not have enough prior experience to draw upon.

Making Creative Decisions

In addition to the rational decision making, bounded rationality models, and intuitive decision making, creative decision making is a vital part of being an effective decision maker. Creativity is the generation of new, imaginative ideas. With the flattening of organizations and intense competition among organizations, individuals and organizations are driven to be creative in decisions ranging from cutting costs to creating new ways of doing business. Please note that, while creativity is the first step in the innovation process, creativity and innovation are not the same thing. Innovation begins with creative ideas, but it also involves realistic planning and follow-through.

The five steps to creative decision making are similar to the previous decision-making models in some keys ways. All of the models include problem identification , which is the step in which the need for problem solving becomes apparent. If you do not recognize that you have a problem, it is impossible to solve it. Immersion is the step in which the decision maker thinks about the problem consciously and gathers information. A key to success in creative decision making is having or acquiring expertise in the area being studied. Then, incubation occurs. During incubation, the individual sets the problem aside and does not think about it for a while. At this time, the brain is actually working on the problem unconsciously. Then comes illumination or the insight moment, when the solution to the problem becomes apparent to the person, usually when it is least expected. This is the “eureka” moment similar to what happened to the ancient Greek inventor Archimedes, who found a solution to the problem he was working on while he was taking a bath. Finally, the verification and application stage happens when the decision maker consciously verifies the feasibility of the solution and implements the decision.

A NASA scientist describes his decision-making process leading to a creative outcome as follows: He had been trying to figure out a better way to de-ice planes to make the process faster and safer. After recognizing the problem, he had immersed himself in the literature to understand all the options, and he worked on the problem for months trying to figure out a solution. It was not until he was sitting outside of a McDonald’s restaurant with his grandchildren that it dawned on him. The golden arches of the “M” of the McDonald’s logo inspired his solution: he would design the de-icer as a series of M’s! 1 This represented the illumination stage. After he tested and verified his creative solution, he was done with that problem except to reflect on the outcome and process.

Figure 11.9 The Creative Decision-Making Process

How Do You Know If Your Decision-Making Process Is Creative?

Researchers focus on three factors to evaluate the level of creativity in the decision-making process. Fluency refers to the number of ideas a person is able to generate. Flexibility refers to how different the ideas are from one another. If you are able to generate several distinct solutions to a problem, your decision-making process is high on flexibility. Originality refers to an idea’s uniqueness. You might say that Reed Hastings, founder and CEO of Netflix, is a pretty creative person. His decision-making process shows at least two elements of creativity. We do not exactly know how many ideas he had over the course of his career, but his ideas are fairly different from one another. After teaching math in Africa with the Peace Corps, Hastings was accepted at Stanford University, where he earned a master’s degree in computer science. Soon after starting work at a software company, he invented a successful debugging tool, which led to his founding the computer troubleshooting company Pure Software in 1991. After a merger and the subsequent sale of the resulting company in 1997, Hastings founded Netflix, which revolutionized the DVD rental business through online rentals with no late fees. In 2007, Hastings was elected to Microsoft’s board of directors. As you can see, his ideas are high in originality and flexibility (Conlin, 2007).

Figure 11.10 Dimensions of Creativity

Some experts have proposed that creativity occurs as an interaction among three factors: (1) people’s personality traits (openness to experience, risk taking), (2) their attributes (expertise, imagination, motivation), and (3) the context (encouragement from others, time pressure, and physical structures) (Amabile, 1988; Amabile, et. al., 1996; Ford & Gioia, 2000; Tierney, et. al., 1999; Woodman, et. al., 1993). For example, research shows that individuals who are open to experience, are less conscientious, more self-accepting, and more impulsive, tend to be more creative (Feist, 1998).

There are many techniques available that enhance and improve creativity. Linus Pauling, the Nobel prize winner who popularized the idea that vitamin C could help build the immunity system, said, “The best way to have a good idea is to have a lot of ideas.” One popular way to generate ideas is to use brainstorming. Brainstorming is a group process of generated ideas that follows a set of guidelines that include no criticism of ideas during the brainstorming process, the idea that no suggestion is too crazy, and building on other ideas (piggybacking). Research shows that the quantity of ideas actually leads to better idea quality in the end, so setting high idea quotas where the group must reach a set number of ideas before they are done, is recommended to avoid process loss and to maximize the effectiveness of brainstorming. Another unique aspect of brainstorming is that the more people are included in brainstorming, the better the decision outcome will be because the variety of backgrounds and approaches give the group more to draw from. A variation of brainstorming is wildstorming where the group focuses on ideas that are impossible and then imagines what would need to happen to make them possible (Scott, et. al., 2004).

Ideas for Enhancing Organizational Creativity

We have seen that organizational creativity is vital to organizations. Here are some guidelines for enhancing organizational creativity within teams (Amabile, 1998; Gundry, et. al., 1994; Keith, 2008; Pearsall, et. al., 2008; Thompson, 2003).

Team Composition (Organizing/Leading)

- Diversify your team to give them more inputs to build on and more opportunities to create functional conflict while avoiding personal conflict.

- Change group membership to stimulate new ideas and new interaction patterns.

- Leaderless teams can allow teams freedom to create without trying to please anyone up front.

Team Process (Leading)

- Engage in brainstorming to generate ideas—remember to set a high goal for the number of ideas the group should come up with, encourage wild ideas, and take brainwriting breaks.

- Use the nominal group technique in person or electronically to avoid some common group process pitfalls. Consider anonymous feedback as well.

- Use analogies to envision problems and solutions.

Leadership (Leading)

- Challenge teams so that they are engaged but not overwhelmed.

- Let people decide how to achieve goals , rather than telling them what goals to achieve.

- Support and celebrate creativity even when it leads to a mistake. But set up processes to learn from mistakes as well.

- Model creative behavior.

Culture (Organizing)

- Institute organizational memory so that individuals do not spend time on routine tasks.

- Build a physical space conducive to creativity that is playful and humorous—this is a place where ideas can thrive.

- Incorporate creative behavior into the performance appraisal process.

And finally, avoiding groupthink can be an important skill to learn (Janis, 1972).

The four different decision-making models—rational, bounded rationality, intuitive, and creative—vary in terms of how experienced or motivated a decision maker is to make a choice. Choosing the right approach will make you more effective at work and improve your ability to carry out all the P-O-L-C functions.

Figure 11.11

Which decision-making model should I use?

Key Takeaway

Decision making is choosing among alternative courses of action, including inaction. There are different types of decisions, ranging from automatic, programmed decisions to more intensive nonprogrammed decisions. Structured decision-making processes include rational decision making, bounded rationality, intuitive, and creative decision making. Each of these can be useful, depending on the circumstances and the problem that needs to be solved.

- What do you see as the main difference between a successful and an unsuccessful decision? How much does luck versus skill have to do with it? How much time needs to pass to answer the first question?

- Research has shown that over half of the decisions made within organizations fail. Does this surprise you? Why or why not?

- Have you used the rational decision-making model to make a decision? What was the context? How well did the model work?

- Share an example of a decision where you used satisficing. Were you happy with the outcome? Why or why not? When would you be most likely to engage in satisficing?

- Do you think intuition is respected as a decision-making style? Do you think it should be? Why or why not?

1 Interview by author Talya Bauer at Ames Research Center, Mountain View, CA, 1990.

Amabile, T. M. (1988). A model of creativity and innovation in organizations. In B. M. Staw & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in Organizational Behavior, 10 123–167 Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Amabile, T. M., Conti, R., Coon, H., Lazenby, J., & Herron, M. (1996). Assessing the work environment for creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 39 , 1154–1184.

Amabile, T. M. (1998). How to kill creativity. Harvard Business Review, 76 , 76–87.

Blanchard, K., & Peale, N. V. (1988). The power of ethical management . New York: William Morrow.

Breen, B. (2000, August), “What’s your intuition?” Fast Company , 290.

Burke, L. A., & Miller, M. K. (1999). Taking the mystery out of intuitive decision making. Academy of Management Executive, 13 , 91–98.

Conlin, M. (2007, September 14). Netflix: Recruiting and retaining the best talent. Business Week Online . Retrieved March 1, 2008, from http://www.businessweek.com/managing/content/sep2007/ca20070913_564868.htm?campaign_id=rss_null .

Feist, G. J. (1998). A meta-analysis of personality in scientific and artistic creativity. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 2 , 290–309.

Ford, C. M., & Gioia, D. A. (2000). Factors influencing creativity in the domain of managerial decision making. Journal of Management, 26 , 705–732.

Garvin, D. A. (2006, January). All the wrong moves. Harvard Business Review , 18–23.

Gundry, L. K., Kickul, J. R., & Prather, C. W. (1994). Building the creative organization. Organizational Dynamics , 22 , 22–37.

Ireland, R. D., & Miller, C. C. (2004). Decision making and firm success. Academy of Management Executive, 18 , 8–12.

Janis, I. L. (1972). Victims of groupthink . New York: Houghton Mifflin; Whyte, G. (1991). Decision failures: Why they occur and how to prevent them. Academy of Management Executive, 5 , 23–31.

Keith, N., & Frese, M. (2008). Effectiveness of error management training: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93 , 59–69.

Klein, G. (2001). Linking expertise and naturalistic decision making . Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Klein, G. (2003). Intuition at work . New York: Doubleday; Salas, E., &.

Nutt, P. C. (1994). Types of organizational decision processes. Administrative Science Quarterly, 29 , 414–550.

Nutt, P. C. (1998). Surprising but true: Half the decisions in organizations fail. Academy of Management Executive, 13 , 75–90.

Nutt, P. C. (2002). Why decisions fail . San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Pearsall, M. J., Ellis, A. P. J., & Evans, J. M. (2008). Unlocking the effects of gender faultlines on team creativity: Is activation the key? Journal of Applied Psychology, 93 , 225–234.

Scott, G., Leritz, L. E., & Mumford, M. D. (2004). The effectiveness of creativity training: A quantitative review. Creativity Research Journal, 16 , 361–388.

Thompson, L. (2003). Improving the creativity of organizational work groups. Academy of Management Executive, 17 , 96–109.

Tierney, P., Farmer, S. M., & Graen, G. B. (1999). An examination of leadership and employee creativity: The relevance of traits and relationships. Personnel Psychology, 52 , 591–620.

Woodman, R. W., Sawyer, J. E., & Griffin, R. W. (1993). Toward a theory of organizational creativity. Academy of Management Review, 18 , 293–321.

Zell, D. M., Glassman, A. M., & Duron, S. A. (2007). Strategic management in turbulent times: The short and glorious history of accelerated decision making at Hewlett-Packard. Organizational Dynamics, 36 , 93–104.

Principles of Management Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Project Management Tools

What is rational decision-making? What are the steps?

By Hadrat Ajao 4 min read · Posted Mar 25, 2024

Decision-making is undertaken by individuals daily, revolving around what to eat, what to wear, whether to go somewhere, what to read, etc. A decision-making process preempts every human action.

The rational decision-making process is often employed when making choices or decisions. The process is based on logic, reason, and carefully considering available information and options. It is a structured approach to making decisions, and it aims to optimize outcomes and reduce the impacts of biases and emotions in decision-making. When a decision is preceded by rational thinking, the results are often a desired outcome and serve a greater good.

This article will review an example of how Lauren utilized rational decision-making.

Lauren is a successful freelancer who has had a particularly successful year in her career. There has been a surge in her clientele. While this is exciting, it also brings some challenges. Lauren needs to make a decision that will significantly shape her future. The surge in her clientele brings both exciting opportunities and challenging choices.

As the offers pour in, one particularly lucrative deal requires Lauren to transition from her cozy home office to a dedicated workspace. The international client offering this two-year contract needs regular face-to-face meetings on a video call, requiring investment in a professional work office with whiteboards and big screen monitors. She had previously worked from her one-room space, but now she needs to build a professional office space. This proposition coincides with a turning point in Lauren's aspirations.

Lauren was planning to purchase a luxurious car, symbolizing her success. The allure of a vehicle that mirrors her blossoming career beckons her. Yet, the decision looms as she realizes that committing to the needed professional office space means putting her automotive dreams on hold. Lauren is torn between two significant investments promising to enhance her professional and personal life. Here, the rational decision-making process becomes Lauren's guiding light.

1. Defining the problem: First, Lauren needs to clearly define the issue, which is the decision between spending on office space for her growing clientele vs. Buying a luxurious car.

2. Identifying decision criteria: Next, Lauren determines the key factors influencing her decision, considering the long-term benefits of securing the international deal versus the immediate satisfaction of owning a prestigious car.

3. Weighing in the decision criteria: Lauren assigns a weight to each criterion, acknowledging the potential impact on her career trajectory and personal satisfaction.

4. Exploring alternatives: Lauren explores various scenarios, including negotiating with her clients for a compromise to accommodate their needs and fulfill her aspirations.

5. Evaluating alternatives: She objectively assesses the pros and cons of each alternative, weighing the consequences of delaying the car purchase against the potential gains from securing a long-term client commitment.

6. Selecting the best alternative: With a comprehensive analysis, Lauren makes an informed decision aligning with her goals and priorities.

7. Implementing the decision: Lauren takes the necessary steps to either sign the deal, negotiate terms, or pursue an alternative that suits her clients and satisfies her desires.

8. Monitoring and evaluating: With the decision put in action, Lauren stays vigilant, monitoring the outcomes and adjusting her approach to ensure continued success.

9. Learning and adjusting: Lauren reflects on the experience, learning valuable lessons about balancing professional growth and personal fulfillment. This newfound wisdom guides her future decisions as she navigates the evolving landscape of her freelance career.

By following the rational decision-making steps, Lauren transforms a challenging situation into a strategic choice that aligns with her goals and ensures a sustainable and fulfilling path forward.

Faced with the conflicting choices of building a dedicated office space or the allure of buying a luxurious car, Lauren embarked on a journey of introspection guided by the principles of rational decision-making. The weight of her decision hung in the balance, with the potential to shape her professional trajectory and personal satisfaction. After carefully considering the options and thoroughly evaluating the associated criteria, Lauren chose a path harmonizing with her overarching goals.

Recognizing the transformative potential of the international deal and the enduring impact it could have on her burgeoning career, she boldly decided to prioritize building a dedicated office space.

This choice, rooted in rational analysis, reflected Lauren's commitment to long-term success and her understanding of the sacrifices required for sustained growth. While Lauren temporarily put the luxurious car on hold, she embraced the opportunity to cultivate a thriving professional environment that would undoubtedly yield long-term gains, making her dreams of owning a luxurious car a reality soon enough.

In making this decision, Lauren demonstrated her business acumen, resilience, and foresight. The narrative of her freelance journey had evolved, and with this strategic move, she set the stage for continued prosperity. Lauren embraced her new professional chapter with a sense of purpose and the confidence that comes from deliberate decision-making. Lauren's success was not just about the projects she tackled or the words she penned; it was a testament to her ability to navigate complex choices with wisdom, ensuring a trajectory that promised financial gains and personal fulfillment.

In the grand tapestry of her freelance career, this decision stood out as a defining moment, a testament to Lauren's strategic thinking and unwavering commitment to building a legacy beyond the glossy allure of immediate rewards.

Rational decision-making is an important function especially in the Human Resources management area. This book on Rational Decisions in Organisations details the science and art behind it.

About The Author

Hadrat Ajao

Hello, I am Hadrat, a communication specialist and an article writer for Pitch Labs. I am passionate about street children and abandoned women, with a special focus on the African terrain. I enjoy writing poems and creative stories.

Join Our Community

Looking for something else? Get your questions answered in our free online learning community!

Entrepreneurial Resources

Jumpstart your next business with our free resource library.

- Getting Started

- Business Plans

- Document Types

- Keeping Records

- Protections

- Regulations

- Entrepreneurship

- Product & Service Management

- Human Resources

- Social Media Tools

- Advertising

- United States of America

- Applications

- Website Building Tools

- Recruitment

Our organization cannot give out official legal/fiscal guidance. All articles are written by volunteers and it may be beneficial to contact professionals to assist your understanding of the information and to guide your action. Pitch Labs bears no responsibility for the results of actions taken based off of article content or any other form of assistance given.

More in Operations

Operations » Human Resources

What is Cognitive Conflict?

Cognitive conflict is the anxiety and tension that affects an individual when cognitive dissonance occurs. Managing such conflict is essential in the workplace. Read more

Technology » Recruitment

What is the role of technology in recruitment?

Overall, technology enhances the recruitment experience for employers and candidates alike, optimizing every step from application to hiring. Read more

Operations » Project Management Tools

What is Stakeholder Management in Project Management?

This piece details what a stakeholder is, the relevance to project management, and how to manage stakeholders to run a smooth project. Read more

What are the psychological states that help employees feel motivated?

The main psychological states that help employees feel motivated include knowledge of results, experienced meaningfulness, and experienced responsibility. This blog post looks at each of these states and what’s involved in them.. Read more

Recent articles

Legal » Structures

What is an NGO? Are they typically nonprofits? What are the features of an NGO?

An NGO is an independent, nonprofit organization that promotes humanitarian or social missions throughout the globe. Read more

Legal » Protections

Patent Filing: A Step-By-Step Guide

A patent is a legal protection granted to inventors to protect their intellectual property. Read more

Technology » Applications

How can technology be used to reach consumers?

Technology is vital to connect with consumers effectively. Here are six ways technology can facilitate consumer engagement. Read more

- What is i-nexus

- Why i-nexus

- Strategy Execution

- Hoshin Kanri

- Operational excellence

- Case studies

- i-nexus reviews

- Strategy execution guide

- Hoshin Kanri guide

- Operational excellence guide

- Book a demo

- Demo on-demand

- Plan to practice

- Buy or build

- Customer success overview

- Customer success journey

- Customer services

- Customer support

- News & Press

8 types of strategic planning models you should be using

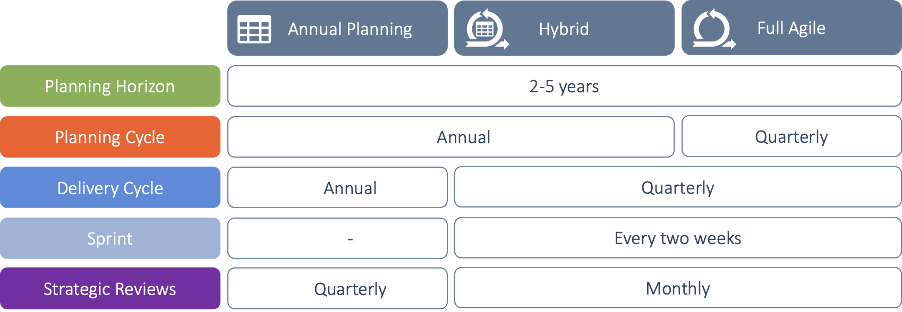

While classical strategic planning models are effective in traditional markets and environments, we no longer live in this world. to thrive here requires planners to evolve and adapt their practices. find out why one strategic planning model - hybrid - stands head and shoulders above the rest..