Jump to navigation

Cochrane Training

Chapter 14: completing ‘summary of findings’ tables and grading the certainty of the evidence.

Holger J Schünemann, Julian PT Higgins, Gunn E Vist, Paul Glasziou, Elie A Akl, Nicole Skoetz, Gordon H Guyatt; on behalf of the Cochrane GRADEing Methods Group (formerly Applicability and Recommendations Methods Group) and the Cochrane Statistical Methods Group

Key Points:

- A ‘Summary of findings’ table for a given comparison of interventions provides key information concerning the magnitudes of relative and absolute effects of the interventions examined, the amount of available evidence and the certainty (or quality) of available evidence.

- ‘Summary of findings’ tables include a row for each important outcome (up to a maximum of seven). Accepted formats of ‘Summary of findings’ tables and interactive ‘Summary of findings’ tables can be produced using GRADE’s software GRADEpro GDT.

- Cochrane has adopted the GRADE approach (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) for assessing certainty (or quality) of a body of evidence.

- The GRADE approach specifies four levels of the certainty for a body of evidence for a given outcome: high, moderate, low and very low.

- GRADE assessments of certainty are determined through consideration of five domains: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision and publication bias. For evidence from non-randomized studies and rarely randomized studies, assessments can then be upgraded through consideration of three further domains.

Cite this chapter as: Schünemann HJ, Higgins JPT, Vist GE, Glasziou P, Akl EA, Skoetz N, Guyatt GH. Chapter 14: Completing ‘Summary of findings’ tables and grading the certainty of the evidence. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.4 (updated August 2023). Cochrane, 2023. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook .

14.1 ‘Summary of findings’ tables

14.1.1 introduction to ‘summary of findings’ tables.

‘Summary of findings’ tables present the main findings of a review in a transparent, structured and simple tabular format. In particular, they provide key information concerning the certainty or quality of evidence (i.e. the confidence or certainty in the range of an effect estimate or an association), the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data on the main outcomes. Cochrane Reviews should incorporate ‘Summary of findings’ tables during planning and publication, and should have at least one key ‘Summary of findings’ table representing the most important comparisons. Some reviews may include more than one ‘Summary of findings’ table, for example if the review addresses more than one major comparison, or includes substantially different populations that require separate tables (e.g. because the effects differ or it is important to show results separately). In the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), all ‘Summary of findings’ tables for a review appear at the beginning, before the Background section.

14.1.2 Selecting outcomes for ‘Summary of findings’ tables

Planning for the ‘Summary of findings’ table starts early in the systematic review, with the selection of the outcomes to be included in: (i) the review; and (ii) the ‘Summary of findings’ table. This is a crucial step, and one that review authors need to address carefully.

To ensure production of optimally useful information, Cochrane Reviews begin by developing a review question and by listing all main outcomes that are important to patients and other decision makers (see Chapter 2 and Chapter 3 ). The GRADE approach to assessing the certainty of the evidence (see Section 14.2 ) defines and operationalizes a rating process that helps separate outcomes into those that are critical, important or not important for decision making. Consultation and feedback on the review protocol, including from consumers and other decision makers, can enhance this process.

Critical outcomes are likely to include clearly important endpoints; typical examples include mortality and major morbidity (such as strokes and myocardial infarction). However, they may also represent frequent minor and rare major side effects, symptoms, quality of life, burdens associated with treatment, and resource issues (costs). Burdens represent the impact of healthcare workload on patient function and well-being, and include the demands of adhering to an intervention that patients or caregivers (e.g. family) may dislike, such as having to undergo more frequent tests, or the restrictions on lifestyle that certain interventions require (Spencer-Bonilla et al 2017).

Frequently, when formulating questions that include all patient-important outcomes for decision making, review authors will confront reports of studies that have not included all these outcomes. This is particularly true for adverse outcomes. For instance, randomized trials might contribute evidence on intended effects, and on frequent, relatively minor side effects, but not report on rare adverse outcomes such as suicide attempts. Chapter 19 discusses strategies for addressing adverse effects. To obtain data for all important outcomes it may be necessary to examine the results of non-randomized studies (see Chapter 24 ). Cochrane, in collaboration with others, has developed guidance for review authors to support their decision about when to look for and include non-randomized studies (Schünemann et al 2013).

If a review includes only randomized trials, these trials may not address all important outcomes and it may therefore not be possible to address these outcomes within the constraints of the review. Review authors should acknowledge these limitations and make them transparent to readers. Review authors are encouraged to include non-randomized studies to examine rare or long-term adverse effects that may not adequately be studied in randomized trials. This raises the possibility that harm outcomes may come from studies in which participants differ from those in studies used in the analysis of benefit. Review authors will then need to consider how much such differences are likely to impact on the findings, and this will influence the certainty of evidence because of concerns about indirectness related to the population (see Section 14.2.2 ).

Non-randomized studies can provide important information not only when randomized trials do not report on an outcome or randomized trials suffer from indirectness, but also when the evidence from randomized trials is rated as very low and non-randomized studies provide evidence of higher certainty. Further discussion of these issues appears also in Chapter 24 .

14.1.3 General template for ‘Summary of findings’ tables

Several alternative standard versions of ‘Summary of findings’ tables have been developed to ensure consistency and ease of use across reviews, inclusion of the most important information needed by decision makers, and optimal presentation (see examples at Figures 14.1.a and 14.1.b ). These formats are supported by research that focused on improved understanding of the information they intend to convey (Carrasco-Labra et al 2016, Langendam et al 2016, Santesso et al 2016). They are available through GRADE’s official software package developed to support the GRADE approach: GRADEpro GDT (www.gradepro.org).

Standard Cochrane ‘Summary of findings’ tables include the following elements using one of the accepted formats. Further guidance on each of these is provided in Section 14.1.6 .

- A brief description of the population and setting addressed by the available evidence (which may be slightly different to or narrower than those defined by the review question).

- A brief description of the comparison addressed in the ‘Summary of findings’ table, including both the experimental and comparison interventions.

- A list of the most critical and/or important health outcomes, both desirable and undesirable, limited to seven or fewer outcomes.

- A measure of the typical burden of each outcomes (e.g. illustrative risk, or illustrative mean, on comparator intervention).

- The absolute and relative magnitude of effect measured for each (if both are appropriate).

- The numbers of participants and studies contributing to the analysis of each outcomes.

- A GRADE assessment of the overall certainty of the body of evidence for each outcome (which may vary by outcome).

- Space for comments.

- Explanations (formerly known as footnotes).

Ideally, ‘Summary of findings’ tables are supported by more detailed tables (known as ‘evidence profiles’) to which the review may be linked, which provide more detailed explanations. Evidence profiles include the same important health outcomes, and provide greater detail than ‘Summary of findings’ tables of both of the individual considerations feeding into the grading of certainty and of the results of the studies (Guyatt et al 2011a). They ensure that a structured approach is used to rating the certainty of evidence. Although they are rarely published in Cochrane Reviews, evidence profiles are often used, for example, by guideline developers in considering the certainty of the evidence to support guideline recommendations. Review authors will find it easier to develop the ‘Summary of findings’ table by completing the rating of the certainty of evidence in the evidence profile first in GRADEpro GDT. They can then automatically convert this to one of the ‘Summary of findings’ formats in GRADEpro GDT, including an interactive ‘Summary of findings’ for publication.

As a measure of the magnitude of effect for dichotomous outcomes, the ‘Summary of findings’ table should provide a relative measure of effect (e.g. risk ratio, odds ratio, hazard) and measures of absolute risk. For other types of data, an absolute measure alone (such as a difference in means for continuous data) might be sufficient. It is important that the magnitude of effect is presented in a meaningful way, which may require some transformation of the result of a meta-analysis (see also Chapter 15, Section 15.4 and Section 15.5 ). Reviews with more than one main comparison should include a separate ‘Summary of findings’ table for each comparison.

Figure 14.1.a provides an example of a ‘Summary of findings’ table. Figure 15.1.b provides an alternative format that may further facilitate users’ understanding and interpretation of the review’s findings. Evidence evaluating different formats suggests that the ‘Summary of findings’ table should include a risk difference as a measure of the absolute effect and authors should preferably use a format that includes a risk difference .

A detailed description of the contents of a ‘Summary of findings’ table appears in Section 14.1.6 .

Figure 14.1.a Example of a ‘Summary of findings’ table

Summary of findings (for interactive version click here )

a All the stockings in the nine studies included in this review were below-knee compression stockings. In four studies the compression strength was 20 mmHg to 30 mmHg at the ankle. It was 10 mmHg to 20 mmHg in the other four studies. Stockings come in different sizes. If a stocking is too tight around the knee it can prevent essential venous return causing the blood to pool around the knee. Compression stockings should be fitted properly. A stocking that is too tight could cut into the skin on a long flight and potentially cause ulceration and increased risk of DVT. Some stockings can be slightly thicker than normal leg covering and can be potentially restrictive with tight foot wear. It is a good idea to wear stockings around the house prior to travel to ensure a good, comfortable fit. Participants put their stockings on two to three hours before the flight in most of the studies. The availability and cost of stockings can vary.

b Two studies recruited high risk participants defined as those with previous episodes of DVT, coagulation disorders, severe obesity, limited mobility due to bone or joint problems, neoplastic disease within the previous two years, large varicose veins or, in one of the studies, participants taller than 190 cm and heavier than 90 kg. The incidence for the seven studies that excluded high risk participants was 1.45% and the incidence for the two studies that recruited high-risk participants (with at least one risk factor) was 2.43%. We have used 10 and 30 per 1000 to express different risk strata, respectively.

c The confidence interval crosses no difference and does not rule out a small increase.

d The measurement of oedema was not validated (indirectness of the outcome) or blinded to the intervention (risk of bias).

e If there are very few or no events and the number of participants is large, judgement about the certainty of evidence (particularly judgements about imprecision) may be based on the absolute effect. Here the certainty rating may be considered ‘high’ if the outcome was appropriately assessed and the event, in fact, did not occur in 2821 studied participants.

f None of the other studies reported adverse effects, apart from four cases of superficial vein thrombosis in varicose veins in the knee region that were compressed by the upper edge of the stocking in one study.

Figure 14.1.b Example of alternative ‘Summary of findings’ table

14.1.4 Producing ‘Summary of findings’ tables

The GRADE Working Group’s software, GRADEpro GDT ( www.gradepro.org ), including GRADE’s interactive handbook, is available to assist review authors in the preparation of ‘Summary of findings’ tables. GRADEpro can use data on the comparator group risk and the effect estimate (entered by the review authors or imported from files generated in RevMan) to produce the relative effects and absolute risks associated with experimental interventions. In addition, it leads the user through the process of a GRADE assessment, and produces a table that can be used as a standalone table in a review (including by direct import into software such as RevMan or integration with RevMan Web), or an interactive ‘Summary of findings’ table (see help resources in GRADEpro).

14.1.5 Statistical considerations in ‘Summary of findings’ tables

14.1.5.1 dichotomous outcomes.

‘Summary of findings’ tables should include both absolute and relative measures of effect for dichotomous outcomes. Risk ratios, odds ratios and risk differences are different ways of comparing two groups with dichotomous outcome data (see Chapter 6, Section 6.4.1 ). Furthermore, there are two distinct risk ratios, depending on which event (e.g. ‘yes’ or ‘no’) is the focus of the analysis (see Chapter 6, Section 6.4.1.5 ). In the presence of a non-zero intervention effect, any variation across studies in the comparator group risks (i.e. variation in the risk of the event occurring without the intervention of interest, for example in different populations) makes it impossible for more than one of these measures to be truly the same in every study.

It has long been assumed in epidemiology that relative measures of effect are more consistent than absolute measures of effect from one scenario to another. There is empirical evidence to support this assumption (Engels et al 2000, Deeks and Altman 2001, Furukawa et al 2002). For this reason, meta-analyses should generally use either a risk ratio or an odds ratio as a measure of effect (see Chapter 10, Section 10.4.3 ). Correspondingly, a single estimate of relative effect is likely to be a more appropriate summary than a single estimate of absolute effect. If a relative effect is indeed consistent across studies, then different comparator group risks will have different implications for absolute benefit. For instance, if the risk ratio is consistently 0.75, then the experimental intervention would reduce a comparator group risk of 80% to 60% in the intervention group (an absolute risk reduction of 20 percentage points), but would also reduce a comparator group risk of 20% to 15% in the intervention group (an absolute risk reduction of 5 percentage points).

‘Summary of findings’ tables are built around the assumption of a consistent relative effect. It is therefore important to consider the implications of this effect for different comparator group risks (these can be derived or estimated from a number of sources, see Section 14.1.6.3 ), which may require an assessment of the certainty of evidence for prognostic evidence (Spencer et al 2012, Iorio et al 2015). For any comparator group risk, it is possible to estimate a corresponding intervention group risk (i.e. the absolute risk with the intervention) from the meta-analytic risk ratio or odds ratio. Note that the numbers provided in the ‘Corresponding risk’ column are specific to the ‘risks’ in the adjacent column.

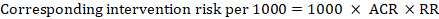

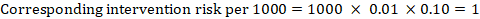

For the meta-analytic risk ratio (RR) and assumed comparator risk (ACR) the corresponding intervention risk is obtained as:

As an example, in Figure 14.1.a , the meta-analytic risk ratio for symptomless deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is RR = 0.10 (95% CI 0.04 to 0.26). Assuming a comparator risk of ACR = 10 per 1000 = 0.01, we obtain:

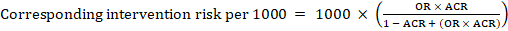

For the meta-analytic odds ratio (OR) and assumed comparator risk, ACR, the corresponding intervention risk is obtained as:

Upper and lower confidence limits for the corresponding intervention risk are obtained by replacing RR or OR by their upper and lower confidence limits, respectively (e.g. replacing 0.10 with 0.04, then with 0.26, in the example). Such confidence intervals do not incorporate uncertainty in the assumed comparator risks.

When dealing with risk ratios, it is critical that the same definition of ‘event’ is used as was used for the meta-analysis. For example, if the meta-analysis focused on ‘death’ (as opposed to survival) as the event, then corresponding risks in the ‘Summary of findings’ table must also refer to ‘death’.

In (rare) circumstances in which there is clear rationale to assume a consistent risk difference in the meta-analysis, in principle it is possible to present this for relevant ‘assumed risks’ and their corresponding risks, and to present the corresponding (different) relative effects for each assumed risk.

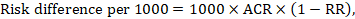

The risk difference expresses the difference between the ACR and the corresponding intervention risk (or the difference between the experimental and the comparator intervention).

For the meta-analytic risk ratio (RR) and assumed comparator risk (ACR) the corresponding risk difference is obtained as (note that risks can also be expressed using percentage or percentage points):

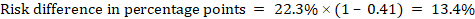

As an example, in Figure 14.1.b the meta-analytic risk ratio is 0.41 (95% CI 0.29 to 0.55) for diarrhoea in children less than 5 years of age. Assuming a comparator group risk of 22.3% we obtain:

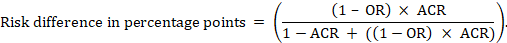

For the meta-analytic odds ratio (OR) and assumed comparator risk (ACR) the absolute risk difference is obtained as (percentage points):

Upper and lower confidence limits for the absolute risk difference are obtained by re-running the calculation above while replacing RR or OR by their upper and lower confidence limits, respectively (e.g. replacing 0.41 with 0.28, then with 0.55, in the example). Such confidence intervals do not incorporate uncertainty in the assumed comparator risks.

14.1.5.2 Time-to-event outcomes

Time-to-event outcomes measure whether and when a particular event (e.g. death) occurs (van Dalen et al 2007). The impact of the experimental intervention relative to the comparison group on time-to-event outcomes is usually measured using a hazard ratio (HR) (see Chapter 6, Section 6.8.1 ).

A hazard ratio expresses a relative effect estimate. It may be used in various ways to obtain absolute risks and other interpretable quantities for a specific population. Here we describe how to re-express hazard ratios in terms of: (i) absolute risk of event-free survival within a particular period of time; (ii) absolute risk of an event within a particular period of time; and (iii) median time to the event. All methods are built on an assumption of consistent relative effects (i.e. that the hazard ratio does not vary over time).

(i) Absolute risk of event-free survival within a particular period of time Event-free survival (e.g. overall survival) is commonly reported by individual studies. To obtain absolute effects for time-to-event outcomes measured as event-free survival, the summary HR can be used in conjunction with an assumed proportion of patients who are event-free in the comparator group (Tierney et al 2007). This proportion of patients will be specific to a period of time of observation. However, it is not strictly necessary to specify this period of time. For instance, a proportion of 50% of event-free patients might apply to patients with a high event rate observed over 1 year, or to patients with a low event rate observed over 2 years.

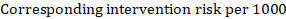

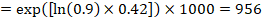

As an example, suppose the meta-analytic hazard ratio is 0.42 (95% CI 0.25 to 0.72). Assuming a comparator group risk of event-free survival (e.g. for overall survival people being alive) at 2 years of ACR = 900 per 1000 = 0.9 we obtain:

so that that 956 per 1000 people will be alive with the experimental intervention at 2 years. The derivation of the risk should be explained in a comment or footnote.

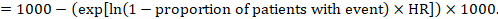

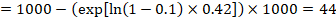

(ii) Absolute risk of an event within a particular period of time To obtain this absolute effect, again the summary HR can be used (Tierney et al 2007):

In the example, suppose we assume a comparator group risk of events (e.g. for mortality, people being dead) at 2 years of ACR = 100 per 1000 = 0.1. We obtain:

so that that 44 per 1000 people will be dead with the experimental intervention at 2 years.

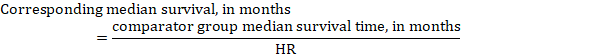

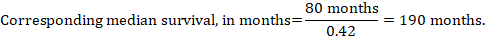

(iii) Median time to the event Instead of absolute numbers, the time to the event in the intervention and comparison groups can be expressed as median survival time in months or years. To obtain median survival time the pooled HR can be applied to an assumed median survival time in the comparator group (Tierney et al 2007):

In the example, assuming a comparator group median survival time of 80 months, we obtain:

For all three of these options for re-expressing results of time-to-event analyses, upper and lower confidence limits for the corresponding intervention risk are obtained by replacing HR by its upper and lower confidence limits, respectively (e.g. replacing 0.42 with 0.25, then with 0.72, in the example). Again, as for dichotomous outcomes, such confidence intervals do not incorporate uncertainty in the assumed comparator group risks. This is of special concern for long-term survival with a low or moderate mortality rate and a corresponding high number of censored patients (i.e. a low number of patients under risk and a high censoring rate).

14.1.6 Detailed contents of a ‘Summary of findings’ table

14.1.6.1 table title and header.

The title of each ‘Summary of findings’ table should specify the healthcare question, framed in terms of the population and making it clear exactly what comparison of interventions are made. In Figure 14.1.a , the population is people taking long aeroplane flights, the intervention is compression stockings, and the control is no compression stockings.

The first rows of each ‘Summary of findings’ table should provide the following ‘header’ information:

Patients or population This further clarifies the population (and possibly the subpopulations) of interest and ideally the magnitude of risk of the most crucial adverse outcome at which an intervention is directed. For instance, people on a long-haul flight may be at different risks for DVT; those using selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) might be at different risk for side effects; while those with atrial fibrillation may be at low (< 1%), moderate (1% to 4%) or high (> 4%) yearly risk of stroke.

Setting This should state any specific characteristics of the settings of the healthcare question that might limit the applicability of the summary of findings to other settings (e.g. primary care in Europe and North America).

Intervention The experimental intervention.

Comparison The comparator intervention (including no specific intervention).

14.1.6.2 Outcomes

The rows of a ‘Summary of findings’ table should include all desirable and undesirable health outcomes (listed in order of importance) that are essential for decision making, up to a maximum of seven outcomes. If there are more outcomes in the review, review authors will need to omit the less important outcomes from the table, and the decision selecting which outcomes are critical or important to the review should be made during protocol development (see Chapter 3 ). Review authors should provide time frames for the measurement of the outcomes (e.g. 90 days or 12 months) and the type of instrument scores (e.g. ranging from 0 to 100).

Note that review authors should include the pre-specified critical and important outcomes in the table whether data are available or not. However, they should be alert to the possibility that the importance of an outcome (e.g. a serious adverse effect) may only become known after the protocol was written or the analysis was carried out, and should take appropriate actions to include these in the ‘Summary of findings’ table.

The ‘Summary of findings’ table can include effects in subgroups of the population for different comparator risks and effect sizes separately. For instance, in Figure 14.1.b effects are presented for children younger and older than 5 years separately. Review authors may also opt to produce separate ‘Summary of findings’ tables for different populations.

Review authors should include serious adverse events, but it might be possible to combine minor adverse events as a single outcome, and describe this in an explanatory footnote (note that it is not appropriate to add events together unless they are independent, that is, a participant who has experienced one adverse event has an unaffected chance of experiencing the other adverse event).

Outcomes measured at multiple time points represent a particular problem. In general, to keep the table simple, review authors should present multiple time points only for outcomes critical to decision making, where either the result or the decision made are likely to vary over time. The remainder should be presented at a common time point where possible.

Review authors can present continuous outcome measures in the ‘Summary of findings’ table and should endeavour to make these interpretable to the target audience. This requires that the units are clear and readily interpretable, for example, days of pain, or frequency of headache, and the name and scale of any measurement tools used should be stated (e.g. a Visual Analogue Scale, ranging from 0 to 100). However, many measurement instruments are not readily interpretable by non-specialist clinicians or patients, for example, points on a Beck Depression Inventory or quality of life score. For these, a more interpretable presentation might involve converting a continuous to a dichotomous outcome, such as >50% improvement (see Chapter 15, Section 15.5 ).

14.1.6.3 Best estimate of risk with comparator intervention

Review authors should provide up to three typical risks for participants receiving the comparator intervention. For dichotomous outcomes, we recommend that these be presented in the form of the number of people experiencing the event per 100 or 1000 people (natural frequency) depending on the frequency of the outcome. For continuous outcomes, this would be stated as a mean or median value of the outcome measured.

Estimated or assumed comparator intervention risks could be based on assessments of typical risks in different patient groups derived from the review itself, individual representative studies in the review, or risks derived from a systematic review of prognosis studies or other sources of evidence which may in turn require an assessment of the certainty for the prognostic evidence (Spencer et al 2012, Iorio et al 2015). Ideally, risks would reflect groups that clinicians can easily identify on the basis of their presenting features.

An explanatory footnote should specify the source or rationale for each comparator group risk, including the time period to which it corresponds where appropriate. In Figure 14.1.a , clinicians can easily differentiate individuals with risk factors for deep venous thrombosis from those without. If there is known to be little variation in baseline risk then review authors may use the median comparator group risk across studies. If typical risks are not known, an option is to choose the risk from the included studies, providing the second highest for a high and the second lowest for a low risk population.

14.1.6.4 Risk with intervention

For dichotomous outcomes, review authors should provide a corresponding absolute risk for each comparator group risk, along with a confidence interval. This absolute risk with the (experimental) intervention will usually be derived from the meta-analysis result presented in the relative effect column (see Section 14.1.6.6 ). Formulae are provided in Section 14.1.5 . Review authors should present the absolute effect in the same format as the risks with comparator intervention (see Section 14.1.6.3 ), for example as the number of people experiencing the event per 1000 people.

For continuous outcomes, a difference in means or standardized difference in means should be presented with its confidence interval. These will typically be obtained directly from a meta-analysis. Explanatory text should be used to clarify the meaning, as in Figures 14.1.a and 14.1.b .

14.1.6.5 Risk difference

For dichotomous outcomes, the risk difference can be provided using one of the ‘Summary of findings’ table formats as an additional option (see Figure 14.1.b ). This risk difference expresses the difference between the experimental and comparator intervention and will usually be derived from the meta-analysis result presented in the relative effect column (see Section 14.1.6.6 ). Formulae are provided in Section 14.1.5 . Review authors should present the risk difference in the same format as assumed and corresponding risks with comparator intervention (see Section 14.1.6.3 ); for example, as the number of people experiencing the event per 1000 people or as percentage points if the assumed and corresponding risks are expressed in percentage.

For continuous outcomes, if the ‘Summary of findings’ table includes this option, the mean difference can be presented here and the ‘corresponding risk’ column left blank (see Figure 14.1.b ).

14.1.6.6 Relative effect (95% CI)

The relative effect will typically be a risk ratio or odds ratio (or occasionally a hazard ratio) with its accompanying 95% confidence interval, obtained from a meta-analysis performed on the basis of the same effect measure. Risk ratios and odds ratios are similar when the comparator intervention risks are low and effects are small, but may differ considerably when comparator group risks increase. The meta-analysis may involve an assumption of either fixed or random effects, depending on what the review authors consider appropriate, and implying that the relative effect is either an estimate of the effect of the intervention, or an estimate of the average effect of the intervention across studies, respectively.

14.1.6.7 Number of participants (studies)

This column should include the number of participants assessed in the included studies for each outcome and the corresponding number of studies that contributed these participants.

14.1.6.8 Certainty of the evidence (GRADE)

Review authors should comment on the certainty of the evidence (also known as quality of the body of evidence or confidence in the effect estimates). Review authors should use the specific evidence grading system developed by the GRADE Working Group (Atkins et al 2004, Guyatt et al 2008, Guyatt et al 2011a), which is described in detail in Section 14.2 . The GRADE approach categorizes the certainty in a body of evidence as ‘high’, ‘moderate’, ‘low’ or ‘very low’ by outcome. This is a result of judgement, but the judgement process operates within a transparent structure. As an example, the certainty would be ‘high’ if the summary were of several randomized trials with low risk of bias, but the rating of certainty becomes lower if there are concerns about risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision or publication bias. Judgements other than of ‘high’ certainty should be made transparent using explanatory footnotes or the ‘Comments’ column in the ‘Summary of findings’ table (see Section 14.1.6.10 ).

14.1.6.9 Comments

The aim of the ‘Comments’ field is to help interpret the information or data identified in the row. For example, this may be on the validity of the outcome measure or the presence of variables that are associated with the magnitude of effect. Important caveats about the results should be flagged here. Not all rows will need comments, and it is best to leave a blank if there is nothing warranting a comment.

14.1.6.10 Explanations

Detailed explanations should be included as footnotes to support the judgements in the ‘Summary of findings’ table, such as the overall GRADE assessment. The explanations should describe the rationale for important aspects of the content. Table 14.1.a lists guidance for useful explanations. Explanations should be concise, informative, relevant, easy to understand and accurate. If explanations cannot be sufficiently described in footnotes, review authors should provide further details of the issues in the Results and Discussion sections of the review.

Table 14.1.a Guidance for providing useful explanations in ‘Summary of findings’ (SoF) tables. Adapted from Santesso et al (2016)

14.2 Assessing the certainty or quality of a body of evidence

14.2.1 the grade approach.

The Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation Working Group (GRADE Working Group) has developed a system for grading the certainty of evidence (Schünemann et al 2003, Atkins et al 2004, Schünemann et al 2006, Guyatt et al 2008, Guyatt et al 2011a). Over 100 organizations including the World Health Organization (WHO), the American College of Physicians, the American Society of Hematology (ASH), the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology in Health (CADTH) and the National Institutes of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) in the UK have adopted the GRADE system ( www.gradeworkinggroup.org ).

Cochrane has also formally adopted this approach, and all Cochrane Reviews should use GRADE to evaluate the certainty of evidence for important outcomes (see MECIR Box 14.2.a ).

MECIR Box 14.2.a Relevant expectations for conduct of intervention reviews

For systematic reviews, the GRADE approach defines the certainty of a body of evidence as the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association is close to the quantity of specific interest. Assessing the certainty of a body of evidence involves consideration of within- and across-study risk of bias (limitations in study design and execution or methodological quality), inconsistency (or heterogeneity), indirectness of evidence, imprecision of the effect estimates and risk of publication bias (see Section 14.2.2 ), as well as domains that may increase our confidence in the effect estimate (as described in Section 14.2.3 ). The GRADE system entails an assessment of the certainty of a body of evidence for each individual outcome. Judgements about the domains that determine the certainty of evidence should be described in the results or discussion section and as part of the ‘Summary of findings’ table.

The GRADE approach specifies four levels of certainty ( Figure 14.2.a ). For interventions, including diagnostic and other tests that are evaluated as interventions (Schünemann et al 2008b, Schünemann et al 2008a, Balshem et al 2011, Schünemann et al 2012), the starting point for rating the certainty of evidence is categorized into two types:

- randomized trials; and

- non-randomized studies of interventions (NRSI), including observational studies (including but not limited to cohort studies, and case-control studies, cross-sectional studies, case series and case reports, although not all of these designs are usually included in Cochrane Reviews).

There are many instances in which review authors rely on information from NRSI, in particular to evaluate potential harms (see Chapter 24 ). In addition, review authors can obtain relevant data from both randomized trials and NRSI, with each type of evidence complementing the other (Schünemann et al 2013).

In GRADE, a body of evidence from randomized trials begins with a high-certainty rating while a body of evidence from NRSI begins with a low-certainty rating. The lower rating with NRSI is the result of the potential bias induced by the lack of randomization (i.e. confounding and selection bias).

However, when using the new Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool (Sterne et al 2016), an assessment tool that covers the risk of bias due to lack of randomization, all studies may start as high certainty of the evidence (Schünemann et al 2018). The approach of starting all study designs (including NRSI) as high certainty does not conflict with the initial GRADE approach of starting the rating of NRSI as low certainty evidence. This is because a body of evidence from NRSI should generally be downgraded by two levels due to the inherent risk of bias associated with the lack of randomization, namely confounding and selection bias. Not downgrading NRSI from high to low certainty needs transparent and detailed justification for what mitigates concerns about confounding and selection bias (Schünemann et al 2018). Very few examples of where not rating down by two levels is appropriate currently exist.

The highest certainty rating is a body of evidence when there are no concerns in any of the GRADE factors listed in Figure 14.2.a . Review authors often downgrade evidence to moderate, low or even very low certainty evidence, depending on the presence of the five factors in Figure 14.2.a . Usually, certainty rating will fall by one level for each factor, up to a maximum of three levels for all factors. If there are very severe problems for any one domain (e.g. when assessing risk of bias, all studies were unconcealed, unblinded and lost over 50% of their patients to follow-up), evidence may fall by two levels due to that factor alone. It is not possible to rate lower than ‘very low certainty’ evidence.

Review authors will generally grade evidence from sound non-randomized studies as low certainty, even if ROBINS-I is used. If, however, such studies yield large effects and there is no obvious bias explaining those effects, review authors may rate the evidence as moderate or – if the effect is large enough – even as high certainty ( Figure 14.2.a ). The very low certainty level is appropriate for, but is not limited to, studies with critical problems and unsystematic clinical observations (e.g. case series or case reports).

Figure 14.2.a Levels of the certainty of a body of evidence in the GRADE approach. *Upgrading criteria are usually applicable to non-randomized studies only (but exceptions exist).

14.2.2 Domains that can lead to decreasing the certainty level of a body of evidence

We now describe in more detail the five reasons (or domains) for downgrading the certainty of a body of evidence for a specific outcome. In each case, if no reason is found for downgrading the evidence, it should be classified as 'no limitation or not serious' (not important enough to warrant downgrading). If a reason is found for downgrading the evidence, it should be classified as 'serious' (downgrading the certainty rating by one level) or 'very serious' (downgrading the certainty grade by two levels). For non-randomized studies assessed with ROBINS-I, rating down by three levels should be classified as 'extremely' serious.

(1) Risk of bias or limitations in the detailed design and implementation

Our confidence in an estimate of effect decreases if studies suffer from major limitations that are likely to result in a biased assessment of the intervention effect. For randomized trials, these methodological limitations include failure to generate a random sequence, lack of allocation sequence concealment, lack of blinding (particularly with subjective outcomes that are highly susceptible to biased assessment), a large loss to follow-up or selective reporting of outcomes. Chapter 8 provides a discussion of study-level assessments of risk of bias in the context of a Cochrane Review, and proposes an approach to assessing the risk of bias for an outcome across studies as ‘Low’ risk of bias, ‘Some concerns’ and ‘High’ risk of bias for randomized trials. Levels of ‘Low’. ‘Moderate’, ‘Serious’ and ‘Critical’ risk of bias arise for non-randomized studies assessed with ROBINS-I ( Chapter 25 ). These assessments should feed directly into this GRADE domain. In particular, ‘Low’ risk of bias would indicate ‘no limitation’; ‘Some concerns’ would indicate either ‘no limitation’ or ‘serious limitation’; and ‘High’ risk of bias would indicate either ‘serious limitation’ or ‘very serious limitation’. ‘Critical’ risk of bias on ROBINS-I would indicate extremely serious limitations in GRADE. Review authors should use their judgement to decide between alternative categories, depending on the likely magnitude of the potential biases.

Every study addressing a particular outcome will differ, to some degree, in the risk of bias. Review authors should make an overall judgement on whether the certainty of evidence for an outcome warrants downgrading on the basis of study limitations. The assessment of study limitations should apply to the studies contributing to the results in the ‘Summary of findings’ table, rather than to all studies that could potentially be included in the analysis. We have argued in Chapter 7, Section 7.6.2 , that the primary analysis should be restricted to studies at low (or low and unclear) risk of bias where possible.

Table 14.2.a presents the judgements that must be made in going from assessments of the risk of bias to judgements about study limitations for each outcome included in a ‘Summary of findings’ table. A rating of high certainty evidence can be achieved only when most evidence comes from studies that met the criteria for low risk of bias. For example, of the 22 studies addressing the impact of beta-blockers on mortality in patients with heart failure, most probably or certainly used concealed allocation of the sequence, all blinded at least some key groups and follow-up of randomized patients was almost complete (Brophy et al 2001). The certainty of evidence might be downgraded by one level when most of the evidence comes from individual studies either with a crucial limitation for one item, or with some limitations for multiple items. An example of very serious limitations, warranting downgrading by two levels, is provided by evidence on surgery versus conservative treatment in the management of patients with lumbar disc prolapse (Gibson and Waddell 2007). We are uncertain of the benefit of surgery in reducing symptoms after one year or longer, because the one study included in the analysis had inadequate concealment of the allocation sequence and the outcome was assessed using a crude rating by the surgeon without blinding.

(2) Unexplained heterogeneity or inconsistency of results

When studies yield widely differing estimates of effect (heterogeneity or variability in results), investigators should look for robust explanations for that heterogeneity. For instance, drugs may have larger relative effects in sicker populations or when given in larger doses. A detailed discussion of heterogeneity and its investigation is provided in Chapter 10, Section 10.10 and Section 10.11 . If an important modifier exists, with good evidence that important outcomes are different in different subgroups (which would ideally be pre-specified), then a separate ‘Summary of findings’ table may be considered for a separate population. For instance, a separate ‘Summary of findings’ table would be used for carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with high grade stenosis (70% to 99%) in which the intervention is, in the hands of the right surgeons, beneficial, and another (if review authors considered it relevant) for asymptomatic patients with low grade stenosis (less than 30%) in which surgery appears harmful (Orrapin and Rerkasem 2017). When heterogeneity exists and affects the interpretation of results, but review authors are unable to identify a plausible explanation with the data available, the certainty of the evidence decreases.

(3) Indirectness of evidence

Two types of indirectness are relevant. First, a review comparing the effectiveness of alternative interventions (say A and B) may find that randomized trials are available, but they have compared A with placebo and B with placebo. Thus, the evidence is restricted to indirect comparisons between A and B. Where indirect comparisons are undertaken within a network meta-analysis context, GRADE for network meta-analysis should be used (see Chapter 11, Section 11.5 ).

Second, a review may find randomized trials that meet eligibility criteria but address a restricted version of the main review question in terms of population, intervention, comparator or outcomes. For example, suppose that in a review addressing an intervention for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease, most identified studies happened to be in people who also had diabetes. Then the evidence may be regarded as indirect in relation to the broader question of interest because the population is primarily related to people with diabetes. The opposite scenario can equally apply: a review addressing the effect of a preventive strategy for coronary heart disease in people with diabetes may consider studies in people without diabetes to provide relevant, albeit indirect, evidence. This would be particularly likely if investigators had conducted few if any randomized trials in the target population (e.g. people with diabetes). Other sources of indirectness may arise from interventions studied (e.g. if in all included studies a technical intervention was implemented by expert, highly trained specialists in specialist centres, then evidence on the effects of the intervention outside these centres may be indirect), comparators used (e.g. if the comparator groups received an intervention that is less effective than standard treatment in most settings) and outcomes assessed (e.g. indirectness due to surrogate outcomes when data on patient-important outcomes are not available, or when investigators seek data on quality of life but only symptoms are reported). Review authors should make judgements transparent when they believe downgrading is justified, based on differences in anticipated effects in the group of primary interest. Review authors may be aided and increase transparency of their judgements about indirectness if they use Table 14.2.b available in the GRADEpro GDT software (Schünemann et al 2013).

(4) Imprecision of results

When studies include few participants or few events, and thus have wide confidence intervals, review authors can lower their rating of the certainty of the evidence. The confidence intervals included in the ‘Summary of findings’ table will provide readers with information that allows them to make, to some extent, their own rating of precision. Review authors can use a calculation of the optimal information size (OIS) or review information size (RIS), similar to sample size calculations, to make judgements about imprecision (Guyatt et al 2011b, Schünemann 2016). The OIS or RIS is calculated on the basis of the number of participants required for an adequately powered individual study. If the 95% confidence interval excludes a risk ratio (RR) of 1.0, and the total number of events or patients exceeds the OIS criterion, precision is adequate. If the 95% CI includes appreciable benefit or harm (an RR of under 0.75 or over 1.25 is often suggested as a very rough guide) downgrading for imprecision may be appropriate even if OIS criteria are met (Guyatt et al 2011b, Schünemann 2016).

(5) High probability of publication bias

The certainty of evidence level may be downgraded if investigators fail to report studies on the basis of results (typically those that show no effect: publication bias) or outcomes (typically those that may be harmful or for which no effect was observed: selective outcome non-reporting bias). Selective reporting of outcomes from among multiple outcomes measured is assessed at the study level as part of the assessment of risk of bias (see Chapter 8, Section 8.7 ), so for the studies contributing to the outcome in the ‘Summary of findings’ table this is addressed by domain 1 above (limitations in the design and implementation). If a large number of studies included in the review do not contribute to an outcome, or if there is evidence of publication bias, the certainty of the evidence may be downgraded. Chapter 13 provides a detailed discussion of reporting biases, including publication bias, and how it may be tackled in a Cochrane Review. A prototypical situation that may elicit suspicion of publication bias is when published evidence includes a number of small studies, all of which are industry-funded (Bhandari et al 2004). For example, 14 studies of flavanoids in patients with haemorrhoids have shown apparent large benefits, but enrolled a total of only 1432 patients (i.e. each study enrolled relatively few patients) (Alonso-Coello et al 2006). The heavy involvement of sponsors in most of these studies raises questions of whether unpublished studies that suggest no benefit exist (publication bias).

A particular body of evidence can suffer from problems associated with more than one of the five factors listed here, and the greater the problems, the lower the certainty of evidence rating that should result. One could imagine a situation in which randomized trials were available, but all or virtually all of these limitations would be present, and in serious form. A very low certainty of evidence rating would result.

Table 14.2.a Further guidelines for domain 1 (of 5) in a GRADE assessment: going from assessments of risk of bias in studies to judgements about study limitations for main outcomes across studies

Table 14.2.b Judgements about indirectness by outcome (available in GRADEpro GDT)

Intervention:

Comparator:

Direct comparison:

Final judgement about indirectness across domains:

14.2.3 Domains that may lead to increasing the certainty level of a body of evidence

Although NRSI and downgraded randomized trials will generally yield a low rating for certainty of evidence, there will be unusual circumstances in which review authors could ‘upgrade’ such evidence to moderate or even high certainty ( Table 14.3.a ).

- Large effects On rare occasions when methodologically well-done observational studies yield large, consistent and precise estimates of the magnitude of an intervention effect, one may be particularly confident in the results. A large estimated effect (e.g. RR >2 or RR <0.5) in the absence of plausible confounders, or a very large effect (e.g. RR >5 or RR <0.2) in studies with no major threats to validity, might qualify for this. In these situations, while the NRSI may possibly have provided an over-estimate of the true effect, the weak study design may not explain all of the apparent observed benefit. Thus, despite reservations based on the observational study design, review authors are confident that the effect exists. The magnitude of the effect in these studies may move the assigned certainty of evidence from low to moderate (if the effect is large in the absence of other methodological limitations). For example, a meta-analysis of observational studies showed that bicycle helmets reduce the risk of head injuries in cyclists by a large margin (odds ratio (OR) 0.31, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.37) (Thompson et al 2000). This large effect, in the absence of obvious bias that could create the association, suggests a rating of moderate-certainty evidence. Note : GRADE guidance suggests the possibility of rating up one level for a large effect if the relative effect is greater than 2.0. However, if the point estimate of the relative effect is greater than 2.0, but the confidence interval is appreciably below 2.0, then some hesitation would be appropriate in the decision to rate up for a large effect. Another situation allows inference of a strong association without a formal comparative study. Consider the question of the impact of routine colonoscopy versus no screening for colon cancer on the rate of perforation associated with colonoscopy. Here, a large series of representative patients undergoing colonoscopy may provide high certainty evidence about the risk of perforation associated with colonoscopy. When the risk of the event among patients receiving the relevant comparator is known to be near 0 (i.e. we are certain that the incidence of spontaneous colon perforation in patients not undergoing colonoscopy is extremely low), case series or cohort studies of representative patients can provide high certainty evidence of adverse effects associated with an intervention, thereby allowing us to infer a strong association from even a limited number of events.

- Dose-response The presence of a dose-response gradient may increase our confidence in the findings of observational studies and thereby enhance the assigned certainty of evidence. For example, our confidence in the result of observational studies that show an increased risk of bleeding in patients who have supratherapeutic anticoagulation levels is increased by the observation that there is a dose-response gradient between the length of time needed for blood to clot (as measured by the international normalized ratio (INR)) and an increased risk of bleeding (Levine et al 2004). A systematic review of NRSI investigating the effect of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors on cardiovascular events found that the summary estimate (RR) with rofecoxib was 1.33 (95% CI 1.00 to 1.79) with doses less than 25mg/d, and 2.19 (95% CI 1.64 to 2.91) with doses more than 25mg/d. Although residual confounding is likely to exist in the NRSI that address this issue, the existence of a dose-response gradient and the large apparent effect of higher doses of rofecoxib markedly increase our strength of inference that the association cannot be explained by residual confounding, and is therefore likely to be both causal and, at high levels of exposure, substantial. Note : GRADE guidance suggests the possibility of rating up one level for a large effect if the relative effect is greater than 2.0. Here, the fact that the point estimate of the relative effect is greater than 2.0, but the confidence interval is appreciably below 2.0 might make some hesitate in the decision to rate up for a large effect

- Plausible confounding On occasion, all plausible biases from randomized or non-randomized studies may be working to under-estimate an apparent intervention effect. For example, if only sicker patients receive an experimental intervention or exposure, yet they still fare better, it is likely that the actual intervention or exposure effect is larger than the data suggest. For instance, a rigorous systematic review of observational studies including a total of 38 million patients demonstrated higher death rates in private for-profit versus private not-for-profit hospitals (Devereaux et al 2002). One possible bias relates to different disease severity in patients in the two hospital types. It is likely, however, that patients in the not-for-profit hospitals were sicker than those in the for-profit hospitals. Thus, to the extent that residual confounding existed, it would bias results against the not-for-profit hospitals. The second likely bias was the possibility that higher numbers of patients with excellent private insurance coverage could lead to a hospital having more resources and a spill-over effect that would benefit those without such coverage. Since for-profit hospitals are likely to admit a larger proportion of such well-insured patients than not-for-profit hospitals, the bias is once again against the not-for-profit hospitals. Since the plausible biases would all diminish the demonstrated intervention effect, one might consider the evidence from these observational studies as moderate rather than low certainty. A parallel situation exists when observational studies have failed to demonstrate an association, but all plausible biases would have increased an intervention effect. This situation will usually arise in the exploration of apparent harmful effects. For example, because the hypoglycaemic drug phenformin causes lactic acidosis, the related agent metformin was under suspicion for the same toxicity. Nevertheless, very large observational studies have failed to demonstrate an association (Salpeter et al 2007). Given the likelihood that clinicians would be more alert to lactic acidosis in the presence of the agent and over-report its occurrence, one might consider this moderate, or even high certainty, evidence refuting a causal relationship between typical therapeutic doses of metformin and lactic acidosis.

14.3 Describing the assessment of the certainty of a body of evidence using the GRADE framework

Review authors should report the grading of the certainty of evidence in the Results section for each outcome for which this has been performed, providing the rationale for downgrading or upgrading the evidence, and referring to the ‘Summary of findings’ table where applicable.

Table 14.3.a provides a framework and examples for how review authors can justify their judgements about the certainty of evidence in each domain. These justifications should also be included in explanatory notes to the ‘Summary of Findings’ table (see Section 14.1.6.10 ).

Chapter 15, Section 15.6 , describes in more detail how the overall GRADE assessment across all domains can be used to draw conclusions about the effects of the intervention, as well as providing implications for future research.

Table 14.3.a Framework for describing the certainty of evidence and justifying downgrading or upgrading

14.4 Chapter information

Authors: Holger J Schünemann, Julian PT Higgins, Gunn E Vist, Paul Glasziou, Elie A Akl, Nicole Skoetz, Gordon H Guyatt; on behalf of the Cochrane GRADEing Methods Group (formerly Applicability and Recommendations Methods Group) and the Cochrane Statistical Methods Group

Acknowledgements: Andrew D Oxman contributed to earlier versions. Professor Penny Hawe contributed to the text on adverse effects in earlier versions. Jon Deeks provided helpful contributions on an earlier version of this chapter. For details of previous authors and editors of the Handbook , please refer to the Preface.

Funding: This work was in part supported by funding from the Michael G DeGroote Cochrane Canada Centre and the Ontario Ministry of Health.

14.5 References

Alonso-Coello P, Zhou Q, Martinez-Zapata MJ, Mills E, Heels-Ansdell D, Johanson JF, Guyatt G. Meta-analysis of flavonoids for the treatment of haemorrhoids. British Journal of Surgery 2006; 93 : 909-920.

Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, Eccles M, Falck-Ytter Y, Flottorp S, Guyatt GH, Harbour RT, Haugh MC, Henry D, Hill S, Jaeschke R, Leng G, Liberati A, Magrini N, Mason J, Middleton P, Mrukowicz J, O'Connell D, Oxman AD, Phillips B, Schünemann HJ, Edejer TT, Varonen H, Vist GE, Williams JW, Jr., Zaza S. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2004; 328 : 1490.

Balshem H, Helfand M, Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Brozek J, Vist GE, Falck-Ytter Y, Meerpohl J, Norris S, Guyatt GH. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2011; 64 : 401-406.

Bhandari M, Busse JW, Jackowski D, Montori VM, Schünemann H, Sprague S, Mears D, Schemitsch EH, Heels-Ansdell D, Devereaux PJ. Association between industry funding and statistically significant pro-industry findings in medical and surgical randomized trials. Canadian Medical Association Journal 2004; 170 : 477-480.

Brophy JM, Joseph L, Rouleau JL. Beta-blockers in congestive heart failure. A Bayesian meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine 2001; 134 : 550-560.

Carrasco-Labra A, Brignardello-Petersen R, Santesso N, Neumann I, Mustafa RA, Mbuagbaw L, Etxeandia Ikobaltzeta I, De Stio C, McCullagh LJ, Alonso-Coello P, Meerpohl JJ, Vandvik PO, Brozek JL, Akl EA, Bossuyt P, Churchill R, Glenton C, Rosenbaum S, Tugwell P, Welch V, Garner P, Guyatt G, Schünemann HJ. Improving GRADE evidence tables part 1: a randomized trial shows improved understanding of content in summary of findings tables with a new format. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2016; 74 : 7-18.

Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Effect measures for meta-analysis of trials with binary outcomes. In: Egger M, Davey Smith G, Altman DG, editors. Systematic Reviews in Health Care: Meta-analysis in Context . 2nd ed. London (UK): BMJ Publication Group; 2001. p. 313-335.

Devereaux PJ, Choi PT, Lacchetti C, Weaver B, Schünemann HJ, Haines T, Lavis JN, Grant BJ, Haslam DR, Bhandari M, Sullivan T, Cook DJ, Walter SD, Meade M, Khan H, Bhatnagar N, Guyatt GH. A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies comparing mortality rates of private for-profit and private not-for-profit hospitals. Canadian Medical Association Journal 2002; 166 : 1399-1406.

Engels EA, Schmid CH, Terrin N, Olkin I, Lau J. Heterogeneity and statistical significance in meta-analysis: an empirical study of 125 meta-analyses. Statistics in Medicine 2000; 19 : 1707-1728.

Furukawa TA, Guyatt GH, Griffith LE. Can we individualize the 'number needed to treat'? An empirical study of summary effect measures in meta-analyses. International Journal of Epidemiology 2002; 31 : 72-76.

Gibson JN, Waddell G. Surgical interventions for lumbar disc prolapse: updated Cochrane Review. Spine 2007; 32 : 1735-1747.

Guyatt G, Oxman A, Vist G, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann H. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008; 336 : 3.

Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, Kunz R, Vist G, Brozek J, Norris S, Falck-Ytter Y, Glasziou P, DeBeer H, Jaeschke R, Rind D, Meerpohl J, Dahm P, Schünemann HJ. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2011a; 64 : 383-394.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Brozek J, Alonso-Coello P, Rind D, Devereaux PJ, Montori VM, Freyschuss B, Vist G, Jaeschke R, Williams JW, Jr., Murad MH, Sinclair D, Falck-Ytter Y, Meerpohl J, Whittington C, Thorlund K, Andrews J, Schünemann HJ. GRADE guidelines 6. Rating the quality of evidence--imprecision. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2011b; 64 : 1283-1293.

Iorio A, Spencer FA, Falavigna M, Alba C, Lang E, Burnand B, McGinn T, Hayden J, Williams K, Shea B, Wolff R, Kujpers T, Perel P, Vandvik PO, Glasziou P, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. Use of GRADE for assessment of evidence about prognosis: rating confidence in estimates of event rates in broad categories of patients. BMJ 2015; 350 : h870.

Langendam M, Carrasco-Labra A, Santesso N, Mustafa RA, Brignardello-Petersen R, Ventresca M, Heus P, Lasserson T, Moustgaard R, Brozek J, Schünemann HJ. Improving GRADE evidence tables part 2: a systematic survey of explanatory notes shows more guidance is needed. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2016; 74 : 19-27.

Levine MN, Raskob G, Landefeld S, Kearon C, Schulman S. Hemorrhagic complications of anticoagulant treatment: the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy. Chest 2004; 126 : 287S-310S.

Orrapin S, Rerkasem K. Carotid endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017; 6 : CD001081.

Salpeter S, Greyber E, Pasternak G, Salpeter E. Risk of fatal and nonfatal lactic acidosis with metformin use in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007; 4 : CD002967.

Santesso N, Carrasco-Labra A, Langendam M, Brignardello-Petersen R, Mustafa RA, Heus P, Lasserson T, Opiyo N, Kunnamo I, Sinclair D, Garner P, Treweek S, Tovey D, Akl EA, Tugwell P, Brozek JL, Guyatt G, Schünemann HJ. Improving GRADE evidence tables part 3: detailed guidance for explanatory footnotes supports creating and understanding GRADE certainty in the evidence judgments. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2016; 74 : 28-39.

Schünemann HJ, Best D, Vist G, Oxman AD, Group GW. Letters, numbers, symbols and words: how to communicate grades of evidence and recommendations. Canadian Medical Association Journal 2003; 169 : 677-680.

Schünemann HJ, Jaeschke R, Cook DJ, Bria WF, El-Solh AA, Ernst A, Fahy BF, Gould MK, Horan KL, Krishnan JA, Manthous CA, Maurer JR, McNicholas WT, Oxman AD, Rubenfeld G, Turino GM, Guyatt G. An official ATS statement: grading the quality of evidence and strength of recommendations in ATS guidelines and recommendations. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2006; 174 : 605-614.

Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Brozek J, Glasziou P, Jaeschke R, Vist GE, Williams JW, Jr., Kunz R, Craig J, Montori VM, Bossuyt P, Guyatt GH. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations for diagnostic tests and strategies. BMJ 2008a; 336 : 1106-1110.

Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Brozek J, Glasziou P, Bossuyt P, Chang S, Muti P, Jaeschke R, Guyatt GH. GRADE: assessing the quality of evidence for diagnostic recommendations. ACP Journal Club 2008b; 149 : 2.

Schünemann HJ, Mustafa R, Brozek J. [Diagnostic accuracy and linked evidence--testing the chain]. Zeitschrift für Evidenz, Fortbildung und Qualität im Gesundheitswesen 2012; 106 : 153-160.

Schünemann HJ, Tugwell P, Reeves BC, Akl EA, Santesso N, Spencer FA, Shea B, Wells G, Helfand M. Non-randomized studies as a source of complementary, sequential or replacement evidence for randomized controlled trials in systematic reviews on the effects of interventions. Research Synthesis Methods 2013; 4 : 49-62.

Schünemann HJ. Interpreting GRADE's levels of certainty or quality of the evidence: GRADE for statisticians, considering review information size or less emphasis on imprecision? Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2016; 75 : 6-15.

Schünemann HJ, Cuello C, Akl EA, Mustafa RA, Meerpohl JJ, Thayer K, Morgan RL, Gartlehner G, Kunz R, Katikireddi SV, Sterne J, Higgins JPT, Guyatt G, Group GW. GRADE guidelines: 18. How ROBINS-I and other tools to assess risk of bias in nonrandomized studies should be used to rate the certainty of a body of evidence. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2018.

Spencer-Bonilla G, Quinones AR, Montori VM, International Minimally Disruptive Medicine W. Assessing the Burden of Treatment. Journal of General Internal Medicine 2017; 32 : 1141-1145.

Spencer FA, Iorio A, You J, Murad MH, Schünemann HJ, Vandvik PO, Crowther MA, Pottie K, Lang ES, Meerpohl JJ, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, Guyatt GH. Uncertainties in baseline risk estimates and confidence in treatment effects. BMJ 2012; 345 : e7401.

Sterne JAC, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, Henry D, Altman DG, Ansari MT, Boutron I, Carpenter JR, Chan AW, Churchill R, Deeks JJ, Hróbjartsson A, Kirkham J, Jüni P, Loke YK, Pigott TD, Ramsay CR, Regidor D, Rothstein HR, Sandhu L, Santaguida PL, Schünemann HJ, Shea B, Shrier I, Tugwell P, Turner L, Valentine JC, Waddington H, Waters E, Wells GA, Whiting PF, Higgins JPT. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016; 355 : i4919.

Thompson DC, Rivara FP, Thompson R. Helmets for preventing head and facial injuries in bicyclists. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2000; 2 : CD001855.

Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, Burdett S, Sydes MR. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials 2007; 8 .

van Dalen EC, Tierney JF, Kremer LCM. Tips and tricks for understanding and using SR results. No. 7: time‐to‐event data. Evidence-Based Child Health 2007; 2 : 1089-1090.

For permission to re-use material from the Handbook (either academic or commercial), please see here for full details.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Summary – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Research Summary – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Summary

Definition:

A research summary is a brief and concise overview of a research project or study that highlights its key findings, main points, and conclusions. It typically includes a description of the research problem, the research methods used, the results obtained, and the implications or significance of the findings. It is often used as a tool to quickly communicate the main findings of a study to other researchers, stakeholders, or decision-makers.

Structure of Research Summary

The Structure of a Research Summary typically include:

- Introduction : This section provides a brief background of the research problem or question, explains the purpose of the study, and outlines the research objectives.

- Methodology : This section explains the research design, methods, and procedures used to conduct the study. It describes the sample size, data collection methods, and data analysis techniques.

- Results : This section presents the main findings of the study, including statistical analysis if applicable. It may include tables, charts, or graphs to visually represent the data.

- Discussion : This section interprets the results and explains their implications. It discusses the significance of the findings, compares them to previous research, and identifies any limitations or future directions for research.

- Conclusion : This section summarizes the main points of the research and provides a conclusion based on the findings. It may also suggest implications for future research or practical applications of the results.

- References : This section lists the sources cited in the research summary, following the appropriate citation style.

How to Write Research Summary

Here are the steps you can follow to write a research summary:

- Read the research article or study thoroughly: To write a summary, you must understand the research article or study you are summarizing. Therefore, read the article or study carefully to understand its purpose, research design, methodology, results, and conclusions.

- Identify the main points : Once you have read the research article or study, identify the main points, key findings, and research question. You can highlight or take notes of the essential points and findings to use as a reference when writing your summary.

- Write the introduction: Start your summary by introducing the research problem, research question, and purpose of the study. Briefly explain why the research is important and its significance.

- Summarize the methodology : In this section, summarize the research design, methods, and procedures used to conduct the study. Explain the sample size, data collection methods, and data analysis techniques.

- Present the results: Summarize the main findings of the study. Use tables, charts, or graphs to visually represent the data if necessary.

- Interpret the results: In this section, interpret the results and explain their implications. Discuss the significance of the findings, compare them to previous research, and identify any limitations or future directions for research.

- Conclude the summary : Summarize the main points of the research and provide a conclusion based on the findings. Suggest implications for future research or practical applications of the results.

- Revise and edit : Once you have written the summary, revise and edit it to ensure that it is clear, concise, and free of errors. Make sure that your summary accurately represents the research article or study.

- Add references: Include a list of references cited in the research summary, following the appropriate citation style.

Example of Research Summary

Here is an example of a research summary:

Title: The Effects of Yoga on Mental Health: A Meta-Analysis

Introduction: This meta-analysis examines the effects of yoga on mental health. The study aimed to investigate whether yoga practice can improve mental health outcomes such as anxiety, depression, stress, and quality of life.

Methodology : The study analyzed data from 14 randomized controlled trials that investigated the effects of yoga on mental health outcomes. The sample included a total of 862 participants. The yoga interventions varied in length and frequency, ranging from four to twelve weeks, with sessions lasting from 45 to 90 minutes.

Results : The meta-analysis found that yoga practice significantly improved mental health outcomes. Participants who practiced yoga showed a significant reduction in anxiety and depression symptoms, as well as stress levels. Quality of life also improved in those who practiced yoga.

Discussion : The findings of this study suggest that yoga can be an effective intervention for improving mental health outcomes. The study supports the growing body of evidence that suggests that yoga can have a positive impact on mental health. Limitations of the study include the variability of the yoga interventions, which may affect the generalizability of the findings.

Conclusion : Overall, the findings of this meta-analysis support the use of yoga as an effective intervention for improving mental health outcomes. Further research is needed to determine the optimal length and frequency of yoga interventions for different populations.

References :

- Cramer, H., Lauche, R., Langhorst, J., Dobos, G., & Berger, B. (2013). Yoga for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Depression and anxiety, 30(11), 1068-1083.

- Khalsa, S. B. (2004). Yoga as a therapeutic intervention: a bibliometric analysis of published research studies. Indian journal of physiology and pharmacology, 48(3), 269-285.

- Ross, A., & Thomas, S. (2010). The health benefits of yoga and exercise: a review of comparison studies. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 16(1), 3-12.

Purpose of Research Summary

The purpose of a research summary is to provide a brief overview of a research project or study, including its main points, findings, and conclusions. The summary allows readers to quickly understand the essential aspects of the research without having to read the entire article or study.

Research summaries serve several purposes, including:

- Facilitating comprehension: A research summary allows readers to quickly understand the main points and findings of a research project or study without having to read the entire article or study. This makes it easier for readers to comprehend the research and its significance.

- Communicating research findings: Research summaries are often used to communicate research findings to a wider audience, such as policymakers, practitioners, or the general public. The summary presents the essential aspects of the research in a clear and concise manner, making it easier for non-experts to understand.

- Supporting decision-making: Research summaries can be used to support decision-making processes by providing a summary of the research evidence on a particular topic. This information can be used by policymakers or practitioners to make informed decisions about interventions, programs, or policies.

- Saving time: Research summaries save time for researchers, practitioners, policymakers, and other stakeholders who need to review multiple research studies. Rather than having to read the entire article or study, they can quickly review the summary to determine whether the research is relevant to their needs.

Characteristics of Research Summary

The following are some of the key characteristics of a research summary:

- Concise : A research summary should be brief and to the point, providing a clear and concise overview of the main points of the research.

- Objective : A research summary should be written in an objective tone, presenting the research findings without bias or personal opinion.

- Comprehensive : A research summary should cover all the essential aspects of the research, including the research question, methodology, results, and conclusions.

- Accurate : A research summary should accurately reflect the key findings and conclusions of the research.

- Clear and well-organized: A research summary should be easy to read and understand, with a clear structure and logical flow.

- Relevant : A research summary should focus on the most important and relevant aspects of the research, highlighting the key findings and their implications.

- Audience-specific: A research summary should be tailored to the intended audience, using language and terminology that is appropriate and accessible to the reader.

- Citations : A research summary should include citations to the original research articles or studies, allowing readers to access the full text of the research if desired.

When to write Research Summary

Here are some situations when it may be appropriate to write a research summary:

- Proposal stage: A research summary can be included in a research proposal to provide a brief overview of the research aims, objectives, methodology, and expected outcomes.

- Conference presentation: A research summary can be prepared for a conference presentation to summarize the main findings of a study or research project.

- Journal submission: Many academic journals require authors to submit a research summary along with their research article or study. The summary provides a brief overview of the study’s main points, findings, and conclusions and helps readers quickly understand the research.

- Funding application: A research summary can be included in a funding application to provide a brief summary of the research aims, objectives, and expected outcomes.

- Policy brief: A research summary can be prepared as a policy brief to communicate research findings to policymakers or stakeholders in a concise and accessible manner.

Advantages of Research Summary

Research summaries offer several advantages, including: