- Open access

- Published: 13 November 2021

Risk and protective factors of drug abuse among adolescents: a systematic review

- Azmawati Mohammed Nawi 1 ,

- Rozmi Ismail 2 ,

- Fauziah Ibrahim 2 ,

- Mohd Rohaizat Hassan 1 ,

- Mohd Rizal Abdul Manaf 1 ,

- Noh Amit 3 ,

- Norhayati Ibrahim 3 &

- Nurul Shafini Shafurdin 2

BMC Public Health volume 21 , Article number: 2088 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

133k Accesses

97 Citations

20 Altmetric

Metrics details

Drug abuse is detrimental, and excessive drug usage is a worldwide problem. Drug usage typically begins during adolescence. Factors for drug abuse include a variety of protective and risk factors. Hence, this systematic review aimed to determine the risk and protective factors of drug abuse among adolescents worldwide.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) was adopted for the review which utilized three main journal databases, namely PubMed, EBSCOhost, and Web of Science. Tobacco addiction and alcohol abuse were excluded in this review. Retrieved citations were screened, and the data were extracted based on strict inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria include the article being full text, published from the year 2016 until 2020 and provided via open access resource or subscribed to by the institution. Quality assessment was done using Mixed Methods Appraisal Tools (MMAT) version 2018 to assess the methodological quality of the included studies. Given the heterogeneity of the included studies, a descriptive synthesis of the included studies was undertaken.

Out of 425 articles identified, 22 quantitative articles and one qualitative article were included in the final review. Both the risk and protective factors obtained were categorized into three main domains: individual, family, and community factors. The individual risk factors identified were traits of high impulsivity; rebelliousness; emotional regulation impairment, low religious, pain catastrophic, homework completeness, total screen time and alexithymia; the experience of maltreatment or a negative upbringing; having psychiatric disorders such as conduct problems and major depressive disorder; previous e-cigarette exposure; behavioral addiction; low-perceived risk; high-perceived drug accessibility; and high-attitude to use synthetic drugs. The familial risk factors were prenatal maternal smoking; poor maternal psychological control; low parental education; negligence; poor supervision; uncontrolled pocket money; and the presence of substance-using family members. One community risk factor reported was having peers who abuse drugs. The protective factors determined were individual traits of optimism; a high level of mindfulness; having social phobia; having strong beliefs against substance abuse; the desire to maintain one’s health; high paternal awareness of drug abuse; school connectedness; structured activity and having strong religious beliefs.

The outcomes of this review suggest a complex interaction between a multitude of factors influencing adolescent drug abuse. Therefore, successful adolescent drug abuse prevention programs will require extensive work at all levels of domains.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Drug abuse is a global problem; 5.6% of the global population aged 15–64 years used drugs at least once during 2016 [ 1 ]. The usage of drugs among younger people has been shown to be higher than that among older people for most drugs. Drug abuse is also on the rise in many ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) countries, especially among young males between 15 and 30 years of age. The increased burden due to drug abuse among adolescents and young adults was shown by the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study in 2013 [ 2 ]. About 14% of the total health burden in young men is caused by alcohol and drug abuse. Younger people are also more likely to die from substance use disorders [ 3 ], and cannabis is the drug of choice among such users [ 4 ].

Adolescents are the group of people most prone to addiction [ 5 ]. The critical age of initiation of drug use begins during the adolescent period, and the maximum usage of drugs occurs among young people aged 18–25 years old [ 1 ]. During this period, adolescents have a strong inclination toward experimentation, curiosity, susceptibility to peer pressure, rebellion against authority, and poor self-worth, which makes such individuals vulnerable to drug abuse [ 2 ]. During adolescence, the basic development process generally involves changing relations between the individual and the multiple levels of the context within which the young person is accustomed. Variation in the substance and timing of these relations promotes diversity in adolescence and represents sources of risk or protective factors across this life period [ 6 ]. All these factors are crucial to helping young people develop their full potential and attain the best health in the transition to adulthood. Abusing drugs impairs the successful transition to adulthood by impairing the development of critical thinking and the learning of crucial cognitive skills [ 7 ]. Adolescents who abuse drugs are also reported to have higher rates of physical and mental illness and reduced overall health and well-being [ 8 ].

The absence of protective factors and the presence of risk factors predispose adolescents to drug abuse. Some of the risk factors are the presence of early mental and behavioral health problems, peer pressure, poorly equipped schools, poverty, poor parental supervision and relationships, a poor family structure, a lack of opportunities, isolation, gender, and accessibility to drugs [ 9 ]. The protective factors include high self-esteem, religiosity, grit, peer factors, self-control, parental monitoring, academic competence, anti-drug use policies, and strong neighborhood attachment [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ].

The majority of previous systematic reviews done worldwide on drug usage focused on the mental, psychological, or social consequences of substance abuse [ 16 , 17 , 18 ], while some focused only on risk and protective factors for the non-medical use of prescription drugs among youths [ 19 ]. A few studies focused only on the risk factors of single drug usage among adolescents [ 20 ]. Therefore, the development of the current systematic review is based on the main research question: What is the current risk and protective factors among adolescent on the involvement with drug abuse? To the best of our knowledge, there is limited evidence from systematic reviews that explores the risk and protective factors among the adolescent population involved in drug abuse. Especially among developing countries, such as those in South East Asia, such research on the risk and protective factors for drug abuse is scarce. Furthermore, this review will shed light on the recent trends of risk and protective factors and provide insight into the main focus factors for prevention and control activities program. Additionally, this review will provide information on how these risk and protective factors change throughout various developmental stages. Therefore, the objective of this systematic review was to determine the risk and protective factors of drug abuse among adolescents worldwide. This paper thus fills in the gaps of previous studies and adds to the existing body of knowledge. In addition, this review may benefit certain parties in developing countries like Malaysia, where the national response to drugs is developing in terms of harm reduction, prison sentences, drug treatments, law enforcement responses, and civil society participation.

This systematic review was conducted using three databases, PubMed, EBSCOhost, and Web of Science, considering the easy access and wide coverage of reliable journals, focusing on the risk and protective factors of drug abuse among adolescents from 2016 until December 2020. The search was limited to the last 5 years to focus only on the most recent findings related to risk and protective factors. The search strategy employed was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) checklist.

A preliminary search was conducted to identify appropriate keywords and determine whether this review was feasible. Subsequently, the related keywords were searched using online thesauruses, online dictionaries, and online encyclopedias. These keywords were verified and validated by an academic professor at the National University of Malaysia. The keywords used as shown in Table 1 .

Selection criteria

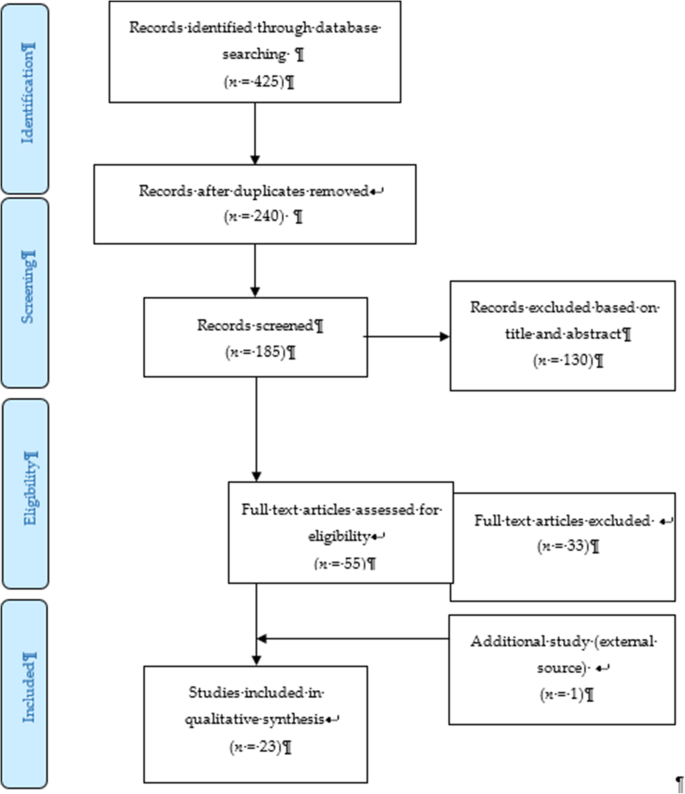

The systematic review process for searching the articles was carried out via the steps shown in Fig. 1 . Firstly, screening was done to remove duplicate articles from the selected search engines. A total of 240 articles were removed in this stage. Titles and abstracts were screened based on the relevancy of the titles to the inclusion and exclusion criteria and the objectives. The inclusion criteria were full text original articles, open access articles or articles subscribed to by the institution, observation and intervention study design and English language articles. The exclusion criteria in this search were (a) case study articles, (b) systematic and narrative review paper articles, (c) non-adolescent-based analyses, (d) non-English articles, and (e) articles focusing on smoking (nicotine) and alcohol-related issues only. A total of 130 articles were excluded after title and abstract screening, leaving 55 articles to be assessed for eligibility. The full text of each article was obtained, and each full article was checked thoroughly to determine if it would fulfil the inclusion criteria and objectives of this study. Each of the authors compared their list of potentially relevant articles and discussed their selections until a final agreement was obtained. A total of 22 articles were accepted to be included in this review. Most of the excluded articles were excluded because the population was not of the target age range—i.e., featuring subjects with an age > 18 years, a cohort born in 1965–1975, or undergraduate college students; the subject matter was not related to the study objective—i.e., assessing the effects on premature mortality, violent behavior, psychiatric illness, individual traits, and personality; type of article such as narrative review and neuropsychiatry review; and because of our inability to obtain the full article—e.g., forthcoming work in 2021. One qualitative article was added to explain the domain related to risk and the protective factors among the adolescents.

PRISMA flow diagram showing the selection of studies on risk and protective factors for drug abuse among adolescents.2.2. Operational Definition

Drug-related substances in this context refer to narcotics, opioids, psychoactive substances, amphetamines, cannabis, ecstasy, heroin, cocaine, hallucinogens, depressants, and stimulants. Drugs of abuse can be either off-label drugs or drugs that are medically prescribed. The two most commonly abused substances not included in this review are nicotine (tobacco) and alcohol. Accordingly, e-cigarettes and nicotine vape were also not included. Further, “adolescence” in this study refers to members of the population aged between 10 to 18 years [ 21 ].

Data extraction tool

All researchers independently extracted information for each article into an Excel spreadsheet. The data were then customized based on their (a) number; (b) year; (c) author and country; (d) titles; (e) study design; (f) type of substance abuse; (g) results—risks and protective factors; and (h) conclusions. A second reviewer crossed-checked the articles assigned to them and provided comments in the table.

Quality assessment tool

By using the Mixed Method Assessment Tool (MMAT version 2018), all articles were critically appraised for their quality by two independent reviewers. This tool has been shown to be useful in systematic reviews encompassing different study designs [ 22 ]. Articles were only selected if both reviewers agreed upon the articles’ quality. Any disagreement between the assigned reviewers was managed by employing a third independent reviewer. All included studies received a rating of “yes” for the questions in the respective domains of the MMAT checklists. Therefore, none of the articles were removed from this review due to poor quality. The Cohen’s kappa (agreement) between the two reviewers was 0.77, indicating moderate agreement [ 23 ].

The initial search found 425 studies for review, but after removing duplicates and applying the criteria listed above, we narrowed the pool to 22 articles, all of which are quantitative in their study design. The studies include three prospective cohort studies [ 24 , 25 , 26 ], one community trial [ 27 ], one case-control study [ 28 ], and nine cross-sectional studies [ 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 ]. After careful discussion, all reviewer panels agreed to add one qualitative study [ 46 ] to help provide reasoning for the quantitative results. The selected qualitative paper was chosen because it discussed almost all domains on the risk and protective factors found in this review.

A summary of all 23 articles is listed in Table 2 . A majority of the studies (13 articles) were from the United States of America (USA) [ 25 , 26 , 27 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 34 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 ], three studies were from the Asia region [ 32 , 33 , 38 ], four studies were from Europe [ 24 , 28 , 40 , 44 ], and one study was from Latin America [ 35 ], Africa [ 43 ] and Mediterranean [ 45 ]. The number of sample participants varied widely between the studies, ranging from 70 samples (minimum) to 700,178 samples (maximum), while the qualitative paper utilized a total of 100 interviewees. There were a wide range of drugs assessed in the quantitative articles, with marijuana being mentioned in 11 studies, cannabis in five studies, and opioid (six studies). There was also large heterogeneity in terms of the study design, type of drug abused, measurements of outcomes, and analysis techniques used. Therefore, the data were presented descriptively.

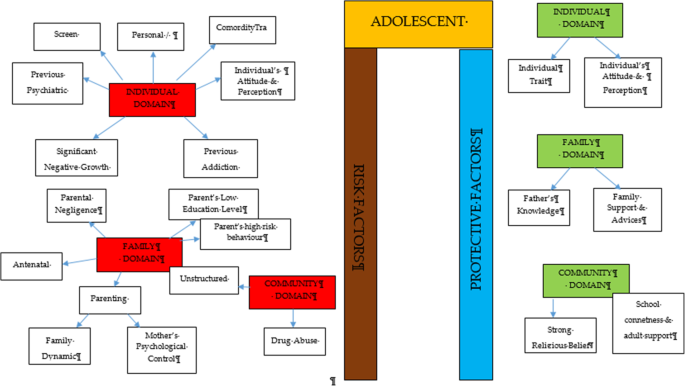

After thorough discussion and evaluation, all the findings (both risk and protective factors) from the review were categorized into three main domains: individual factors, family factors, and community factors. The conceptual framework is summarized in Fig. 2 .

Conceptual framework of risk and protective factors related to adolescent drug abuse

DOMAIN: individual factor

Risk factors.

Almost all the articles highlighted significant findings of individual risk factors for adolescent drug abuse. Therefore, our findings for this domain were further broken down into five more sub-domains consisting of personal/individual traits, significant negative growth exposure, personal psychiatric diagnosis, previous substance history, comorbidity and an individual’s attitude and perception.

Personal/individual traits

Chuang et al. [ 29 ] found that adolescents with high impulsivity traits had a significant positive association with drug addiction. This study also showed that the impulsivity trait alone was an independent risk factor that increased the odds between two to four times for using any drug compared to the non-impulsive group. Another longitudinal study by Guttmannova et al. showed that rebellious traits are positively associated with marijuana drug abuse [ 27 ]. The authors argued that measures of rebelliousness are a good proxy for a youth’s propensity to engage in risky behavior. Nevertheless, Wilson et al. [ 37 ], in a study involving 112 youths undergoing detoxification treatment for opioid abuse, found that a majority of the affected respondents had difficulty in regulating their emotions. The authors found that those with emotional regulation impairment traits became opioid dependent at an earlier age. Apart from that, a case-control study among outpatient youths found that adolescents involved in cannabis abuse had significant alexithymia traits compared to the control population [ 28 ]. Those adolescents scored high in the dimension of Difficulty in Identifying Emotion (DIF), which is one of the key definitions of diagnosing alexithymia. Overall, the adjusted Odds Ratio for DIF in cannabis abuse was 1.11 (95% CI, 1.03–1.20).

Significant negative growth exposure

A history of maltreatment in the past was also shown to have a positive association with adolescent drug abuse. A study found that a history of physical abuse in the past is associated with adolescent drug abuse through a Path Analysis, despite evidence being limited to the female gender [ 25 ]. However, evidence from another study focusing at foster care concluded that any type of maltreatment might result in a prevalence as high as 85.7% for the lifetime use of cannabis and as high as 31.7% for the prevalence of cannabis use within the last 3-months [ 30 ]. The study also found significant latent variables that accounted for drug abuse outcomes, which were chronic physical maltreatment (factor loading of 0.858) and chronic psychological maltreatment (factor loading of 0.825), with an r 2 of 73.6 and 68.1%, respectively. Another study shed light on those living in child welfare service (CWS) [ 35 ]. It was observed through longitudinal measurements that proportions of marijuana usage increased from 9 to 18% after 36 months in CWS. Hence, there is evidence of the possibility of a negative upbringing at such shelters.

Personal psychiatric diagnosis

The robust studies conducted in the USA have deduced that adolescents diagnosed with a conduct problem (CP) have a positive association with marijuana abuse (OR = 1.75 [1.56, 1.96], p < 0.0001). Furthermore, those with a diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) showed a significant positive association with marijuana abuse.

Previous substance and addiction history

Another study found that exposure to e-cigarettes within the past 30 days is related to an increase in the prevalence of marijuana use and prescription drug use by at least four times in the 8th and 10th grades and by at least three times in the 12th grade [ 34 ]. An association between other behavioral addictions and the development of drug abuse was also studied [ 29 ]. Using a 12-item index to assess potential addictive behaviors [ 39 ], significant associations between drug abuse and the groups with two behavioral addictions (OR = 3.19, 95% CI 1.25,9.77) and three behavioral addictions (OR = 3.46, 95% CI 1.25,9.58) were reported.

Comorbidity

The paper by Dash et al. (2020) highlight adolescent with a disease who needs routine medical pain treatment have higher risk of opioid misuse [ 38 ]. The adolescents who have disorder symptoms may have a risk for opioid misuse despite for the pain intensity.

Individual’s attitudes and perceptions

In a study conducted in three Latin America countries (Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay), it was shown that adolescents with low or no perceived risk of taking marijuana had a higher risk of abuse (OR = 8.22 times, 95% CI 7.56, 10.30) [ 35 ]. This finding is in line with another study that investigated 2002 adolescents and concluded that perceiving the drug as harmless was an independent risk factor that could prospectively predict future marijuana abuse [ 27 ]. Moreover, some youth interviewed perceived that they gained benefits from substance use [ 38 ]. The focus group discussion summarized that the youth felt positive personal motivation and could escape from a negative state by taking drugs. Apart from that, adolescents who had high-perceived availability of drugs in their neighborhoods were more likely to increase their usage of marijuana over time (OR = 11.00, 95% CI 9.11, 13.27) [ 35 ]. A cheap price of the substance and the availability of drug dealers around schools were factors for youth accessibility [ 38 ]. Perceived drug accessibility has also been linked with the authorities’ enforcement programs. The youth perception of a lax community enforcement of laws regarding drug use at all-time points predicted an increase in marijuana use in the subsequent assessment period [ 27 ]. Besides perception, a study examining the attitudes towards synthetic drugs based on 8076 probabilistic samples of Macau students found that the odds of the lifetime use of marijuana was almost three times higher among those with a strong attitude towards the use of synthetic drugs [ 32 ]. In addition, total screen time among the adolescent increase the likelihood of frequent cannabis use. Those who reported daily cannabis use have a mean of 12.56 h of total screen time, compared to a mean of 6.93 h among those who reported no cannabis use. Adolescent with more time on internet use, messaging, playing video games and watching TV/movies were significantly associated with more frequent cannabis use [ 44 ].

Protective factors

Individual traits.

Some individual traits have been determined to protect adolescents from developing drug abuse habits. A study by Marin et al. found that youth with an optimistic trait were less likely to become drug dependent [ 33 ]. In this study involving 1104 Iranian students, it was concluded that a higher optimism score (measured using the Children Attributional Style Questionnaire, CASQ) was a protective factor against illicit drug use (OR = 0.90, 95% CI: 0.85–0.95). Another study found that high levels of mindfulness, measured using the 25-item Child Acceptance and Mindfulness Measure, CAMM, lead to a slower progression toward injectable drug abuse among youth with opioid addiction (1.67 years, p = .041) [ 37 ]. In addition, the social phobia trait was found to have a negative association with marijuana use (OR = 0.87, 95% CI 0.77–0.97), as suggested [ 31 ].

According to El Kazdouh et al., individuals with a strong belief against substance use and those with a strong desire to maintain their health were more likely to be protected from involvement in drug abuse [ 46 ].

DOMAIN: family factors

The biological factors underlying drug abuse in adolescents have been reported in several studies. Epigenetic studies are considered important, as they can provide a good outline of the potential pre-natal factors that can be targeted at an earlier stage. Expecting mothers who smoke tobacco and alcohol have an indirect link with adolescent substance abuse in later life [ 24 , 39 ]. Moreover, the dynamic relationship between parents and their children may have some profound effects on the child’s growth. Luk et al. examined the mediator effects between parenting style and substance abuse and found the maternal psychological control dimension to be a significant variable [ 26 ]. The mother’s psychological control was two times higher in influencing her children to be involved in substance abuse compared to the other dimension. Conversely, an indirect risk factor towards youth drug abuse was elaborated in a study in which low parental educational level predicted a greater risk of future drug abuse by reducing the youth’s perception of harm [ 27 , 43 ]. Negligence from a parental perspective could also contribute to this problem. According to El Kazdouh et al. [ 46 ], a lack of parental supervision, uncontrolled pocket money spending among children, and the presence of substance-using family members were the most common negligence factors.

While the maternal factors above were shown to be risk factors, the opposite effect was seen when the paternal figure equipped himself with sufficient knowledge. A study found that fathers with good information and awareness were more likely to protect their adolescent children from drug abuse [ 26 ]. El Kazdouh et al. noted that support and advice could be some of the protective factors in this area [ 46 ].

DOMAIN: community factors

- Risk factor

A study in 2017 showed a positive association between adolescent drug abuse and peers who abuse drugs [ 32 , 39 ]. It was estimated that the odds of becoming a lifetime marijuana user was significantly increased by a factor of 2.5 ( p < 0.001) among peer groups who were taking synthetic drugs. This factor served as peer pressure for youth, who subconsciously had desire to be like the others [ 38 ]. The impact of availability and engagement in structured and unstructured activities also play a role in marijuana use. The findings from Spillane (2000) found that the availability of unstructured activities was associated with increased likelihood of marijuana use [ 42 ].

- Protective factor

Strong religious beliefs integrated into society serve as a crucial protective factor that can prevent adolescents from engaging in drug abuse [ 38 , 45 ]. In addition, the school connectedness and adult support also play a major contribution in the drug use [ 40 ].

The goal of this review was to identify and classify the risks and protective factors that lead adolescents to drug abuse across the three important domains of the individual, family, and community. No findings conflicted with each other, as each of them had their own arguments and justifications. The findings from our review showed that individual factors were the most commonly highlighted. These factors include individual traits, significant negative growth exposure, personal psychiatric diagnosis, previous substance and addiction history, and an individual’s attitude and perception as risk factors.

Within the individual factor domain, nine articles were found to contribute to the subdomain of personal/ individual traits [ 27 , 28 , 29 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 43 , 44 ]. Despite the heterogeneity of the study designs and the substances under investigation, all of the papers found statistically significant results for the possible risk factors of adolescent drug abuse. The traits of high impulsivity, rebelliousness, difficulty in regulating emotions, and alexithymia can be considered negative characteristic traits. These adolescents suffer from the inability to self-regulate their emotions, so they tend to externalize their behaviors as a way to avoid or suppress the negative feelings that they are experiencing [ 41 , 47 , 48 ]. On the other hand, engaging in such behaviors could plausibly provide a greater sense of positive emotions and make them feel good [ 49 ]. Apart from that, evidence from a neurophysiological point of view also suggests that the compulsive drive toward drug use is complemented by deficits in impulse control and decision making (impulsive trait) [ 50 ]. A person’s ability in self-control will seriously impaired with continuous drug use and will lead to the hallmark of addiction [ 51 ].

On the other hand, there are articles that reported some individual traits to be protective for adolescents from engaging in drug abuse. Youth with the optimistic trait, a high level of mindfulness, and social phobia were less likely to become drug dependent [ 31 , 33 , 37 ]. All of these articles used different psychometric instruments to classify each individual trait and were mutually exclusive. Therefore, each trait measured the chance of engaging in drug abuse on its own and did not reflect the chance at the end of the spectrum. These findings show that individual traits can be either protective or risk factors for the drugs used among adolescents. Therefore, any adolescent with negative personality traits should be monitored closely by providing health education, motivation, counselling, and emotional support since it can be concluded that negative personality traits are correlated with high risk behaviours such as drug abuse [ 52 ].

Our study also found that a history of maltreatment has a positive association with adolescent drug abuse. Those adolescents with episodes of maltreatment were considered to have negative growth exposure, as their childhoods were negatively affected by traumatic events. Some significant associations were found between maltreatment and adolescent drug abuse, although the former factor was limited to the female gender [ 25 , 30 , 36 ]. One possible reason for the contrasting results between genders is the different sample populations, which only covered child welfare centers [ 36 ] and foster care [ 30 ]. Regardless of the place, maltreatment can happen anywhere depending on the presence of the perpetrators. To date, evidence that concretely links maltreatment and substance abuse remains limited. However, a plausible explanation for this link could be the indirect effects of posttraumatic stress (i.e., a history of maltreatment) leading to substance use [ 53 , 54 ]. These findings highlight the importance of continuous monitoring and follow-ups with adolescents who have a history of maltreatment and who have ever attended a welfare center.

Addiction sometimes leads to another addiction, as described by the findings of several studies [ 29 , 34 ]. An initial study focused on the effects of e-cigarettes in the development of other substance abuse disorders, particularly those related to marijuana, alcohol, and commonly prescribed medications [ 34 ]. The authors found that the use of e-cigarettes can lead to more severe substance addiction [ 55 ], possibly through normalization of the behavior. On the other hand, Chuang et al.’s extensive study in 2017 analyzed the combined effects of either multiple addictions alone or a combination of multiple addictions together with the impulsivity trait [ 29 ]. The outcomes reported were intriguing and provide the opportunity for targeted intervention. The synergistic effects of impulsiveness and three other substance addictions (marijuana, tobacco, and alcohol) substantially increased the likelihood for drug abuse from 3.46 (95%CI 1.25, 9.58) to 10.13 (95% CI 3.95, 25.95). Therefore, proper rehabilitation is an important strategy to ensure that one addiction will not lead to another addiction.

The likelihood for drug abuse increases as the population perceives little or no harmful risks associated with the drugs. On the opposite side of the coin, a greater perceived risk remains a protective factor for marijuana abuse [ 56 ]. However, another study noted that a stronger determinant for adolescent drug abuse was the perceived availability of the drug [ 35 , 57 ]. Looking at the bigger picture, both perceptions corroborate each other and may inform drug use. Another study, on the other hand, reported that there was a decreasing trend of perceived drug risk in conjunction with the increasing usage of drugs [ 58 ]. As more people do drugs, youth may inevitably perceive those drugs as an acceptable norm without any harmful consequences [ 59 ].

In addition, the total spent for screen time also contribute to drug abuse among adolescent [ 43 ]. This scenario has been proven by many researchers on the effect of screen time on the mental health [ 60 ] that leads to the substance use among the adolescent due to the ubiquity of pro-substance use content on the internet. Adolescent with comorbidity who needs medical pain management by opioids also tend to misuse in future. A qualitative exploration on the perspectives among general practitioners concerning the risk of opioid misuse in people with pain, showed pain management by opioids is a default treatment and misuse is not a main problem for the them [ 61 ]. A careful decision on the use of opioids as a pain management should be consider among the adolescents and their understanding is needed.

Within the family factor domain, family structures were found to have both positive and negative associations with drug abuse among adolescents. As described in one study, paternal knowledge was consistently found to be a protective factor against substance abuse [ 26 ]. With sufficient knowledge, the father can serve as the guardian of his family to monitor and protect his children from negative influences [ 62 ]. The work by Luk et al. also reported a positive association of maternal psychological association towards drug abuse (IRR 2.41, p < 0.05) [ 26 ]. The authors also observed the same effect of paternal psychological control, although it was statistically insignificant. This construct relates to parenting style, and the authors argued that parenting style might have a profound effect on the outcomes under study. While an earlier literature review [ 63 ] also reported such a relationship, a recent study showed a lesser impact [ 64 ] with regards to neglectful parenting styles leading to poorer substance abuse outcomes. Nevertheless, it was highlighted in another study that the adolescents’ perception of a neglectful parenting style increased their odds (OR 2.14, p = 0.012) of developing alcohol abuse, not the parenting style itself [ 65 ]. Altogether, families play vital roles in adolescents’ risk for engaging in substance abuse [ 66 ]. Therefore, any intervention to impede the initiation of substance use or curb existing substance use among adolescents needs to include parents—especially improving parent–child communication and ensuring that parents monitor their children’s activities.

Finally, the community also contributes to drug abuse among adolescents. As shown by Li et al. [ 32 ] and El Kazdouh et al. [ 46 ], peers exert a certain influence on other teenagers by making them subconsciously want to fit into the group. Peer selection and peer socialization processes might explain why peer pressure serves as a risk factor for drug-abuse among adolescents [ 67 ]. Another study reported that strong religious beliefs integrated into society play a crucial role in preventing adolescents from engaging in drug abuse [ 46 ]. Most religions devalue any actions that can cause harmful health effects, such as substance abuse [ 68 ]. Hence, spiritual beliefs may help protect adolescents. This theme has been well established in many studies [ 60 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 ] and, therefore, could be implemented by religious societies as part of interventions to curb the issue of adolescent drug abuse. The connection with school and structured activity did reduce the risk as a study in USA found exposure to media anti-drug messages had an indirect negative effect on substances abuse through school-related activity and social activity [ 73 ]. The school activity should highlight on the importance of developmental perspective when designing and offering school-based prevention programs [75].

Limitations

We adopted a review approach that synthesized existing evidence on the risk and protective factors of adolescents engaging in drug abuse. Although this systematic review builds on the conclusion of a rigorous review of studies in different settings, there are some potential limitations to this work. We may have missed some other important factors, as we only included English articles, and article extraction was only done from the three search engines mentioned. Nonetheless, this review focused on worldwide drug abuse studies, rather than the broader context of substance abuse including alcohol and cigarettes, thereby making this paper more focused.

Conclusions

This review has addressed some recent knowledge related to the individual, familial, and community risk and preventive factors for adolescent drug use. We suggest that more attention should be given to individual factors since most findings were discussed in relation to such factors. With the increasing trend of drug abuse, it will be critical to focus research specifically on this area. Localized studies, especially those related to demographic factors, may be more effective in generating results that are specific to particular areas and thus may be more useful in generating and assessing local control and prevention efforts. Interventions using different theory-based psychotherapies and a recognition of the unique developmental milestones specific to adolescents are among examples that can be used. Relevant holistic approaches should be strengthened not only by relevant government agencies but also by the private sector and non-governmental organizations by promoting protective factors while reducing risk factors in programs involving adolescents from primary school up to adulthood to prevent and control drug abuse. Finally, legal legislation and enforcement against drug abuse should be engaged with regularly as part of our commitment to combat this public health burden.

Data availability and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Nation, U. World Drug Report 2018 (United Nations publication, Sales No. E.18X.XI.9. United Nation publication). 2018. Retrieved from https://www.unodc.org/wdr2018

Google Scholar

Degenhardt L, Stockings E, Patton G, Hall WD, Lynskey M. The increasing global health priority of substance use in young people. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(3):251–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00508-8 Elsevier Ltd.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Ritchie H, Roser M. Drug Use - Our World in Data: Global Change Data Lab; 2019. https://ourworldindata.org/drug-use [10 June 2020]

Holm S, Sandberg S, Kolind T, Hesse M. The importance of cannabis culture in young adult cannabis use. J Subst Abus. 2014;19(3):251–6.

Luikinga SJ, Kim JH, Perry CJ. Developmental perspectives on methamphetamine abuse: exploring adolescent vulnerabilities on brain and behavior. Progress Neuro Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;87(Pt A):78–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.11.010 Elsevier Inc.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Ismail R, Ghazalli MN, Ibrahim N. Not all developmental assets can predict negative mental health outcomes of disadvantaged youth: a case of suburban Kuala Lumpur. Mediterr J Soc Sci. 2015;6(1):452–9. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2015.v6n5s1p452 .

Article Google Scholar

Crews F, He J, Hodge C. Adolescent cortical development: a critical period of vulnerability for addiction. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;86(2):189–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbb.2006.12.001 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Schulte MT, Hser YI. Substance use and associated health conditions throughout the lifespan. Public Health Rev. 2013;35(2). https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03391702 Technosdar Ltd.

Somani, S.; Meghani S. Substance Abuse among Youth: A Harsh Reality 2016. doi: https://doi.org/10.4172/2165-7548.1000330 , 6, 4.

Book Google Scholar

Drabble L, Trocki KF, Klinger JL. Religiosity as a protective factor for hazardous drinking and drug use among sexual minority and heterosexual women: findings from the National Alcohol Survey. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;161:127–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.01.022 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Goliath V, Pretorius B. Peer risk and protective factors in adolescence: Implications for drug use prevention. Soc Work. 2016;52(1):113–29. https://doi.org/10.15270/52-1-482 .

Guerrero LR, Dudovitz R, Chung PJ, Dosanjh KK, Wong MD. Grit: a potential protective factor against substance use and other risk behaviors among Latino adolescents. Acad Pediatr. 2016;16(3):275–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2015.12.016 .

National Institutes on Drug Abuse. What are risk factors and protective factors? National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA); 2003. Retrieved from https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/preventing-drug-use-among-children-adolescents/chapter-1-risk-factors-protective-factors/what-are-risk-factors

Nguyen NN, Newhill CE. The role of religiosity as a protective factor against marijuana use among African American, White, Asian, and Hispanic adolescents. J Subst Abus. 2016;21(5):547–52. https://doi.org/10.3109/14659891.2015.1093558 .

Schinke S, Schwinn T, Hopkins J, Wahlstrom L. Drug abuse risk and protective factors among Hispanic adolescents. Prev Med Rep. 2016;3:185–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.01.012 .

Macleod J, Oakes R, Copello A, Crome PI, Egger PM, Hickman M, et al. Psychological and social sequelae of cannabis and other illicit drug use by young people: a systematic review of longitudinal, general population studies. Lancet. 2004;363(9421):1579–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16200-4 .

Moore TH, Zammit S, Lingford-Hughes A, Barnes TR, Jones PB, Burke M, et al. Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet. 2007;370(9584):319–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61162-3 .

Semple DM, McIntosh AM, Lawrie SM. Cannabis as a risk factor for psychosis: systematic review. J Psychopharmacol. 2005;19(2):187–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881105049040 .

Nargiso JE, Ballard EL, Skeer MR. A systematic review of risk and protective factors associated with nonmedical use of prescription drugs among youth in the united states: A social ecological perspective. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2015;76(1):5–20. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2015.76.5 .

Guxensa M, Nebot M, Ariza C, Ochoa D. Factors associated with the onset of cannabis use: a systematic review of cohort studies. Gac Sanit. 2007;21(3):252–60. https://doi.org/10.1157/13106811 .

Susan MS, Peter SA, Dakshitha W, George CP. The age of adolescence. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2018;2(Issue 3):223–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30022-1 .

Hong QN, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, Dagenais P, et al. The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ Inf. 2018;34(4):285–91. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-180221 .

McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochem Med. 2012;22(3):276–82. https://doi.org/10.11613/bm.2012.031 .

Cecil CAM, Walton E, Smith RG, Viding E, McCrory EJ, Relton CL, et al. DNA methylation and substance-use risk: a prospective, genome-wide study spanning gestation to adolescence. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6(12):e976. https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2016.247 Nature Publishing Group.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kobulsky JM. Gender differences in pathways from physical and sexual abuse to early substance use. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2017;83:25–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.10.027 .

Luk JW, King KM, McCarty CA, McCauley E, Stoep A. Prospective effects of parenting on substance use and problems across Asian/Pacific islander and European American youth: Tests of moderated mediation. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2017;78(4):521–30. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2017.78.521 .

Guttmannova K, Skinner ML, Oesterle S, White HR, Catalano RF, Hawkins JD. The interplay between marijuana-specific risk factors and marijuana use over the course of adolescence. Prev Sci. 2019;20(2):235–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-018-0882-9 .

Dorard G, Bungener C, Phan O, Edel Y, Corcos M, Berthoz S. Is alexithymia related to cannabis use disorder? Results from a case-control study in outpatient adolescent cannabis abusers. J Psychosom Res. 2017;95:74–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.02.012 .

Chuang CWI, Sussman S, Stone MD, Pang RD, Chou CP, Leventhal AM, et al. Impulsivity and history of behavioral addictions are associated with drug use in adolescents. Addict Behav. 2017;74:41–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.05.021 .

Gabrielli J, Jackson Y, Brown S. Associations between maltreatment history and severity of substance use behavior in youth in Foster Care. Child Maltreat. 2016;21(4):298–307. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559516669443 .

Khoddam R, Jackson NJ, Leventhal AM. Internalizing symptoms and conduct problems: redundant, incremental, or interactive risk factors for adolescent substance use during the first year of high school? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;169:48–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.10.007 .

Li SD, Zhang X, Tang W, Xia Y. Predictors and implications of synthetic drug use among adolescents in the gambling Capital of China. SAGE Open. 2017;7(4):215824401773303. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017733031 .

Marin S, Heshmatian E, Nadrian H, Fakhari A, Mohammadpoorasl A. Associations between optimism, tobacco smoking and substance abuse among Iranian high school students. Health Promot Perspect. 2019;9(4):279–84. https://doi.org/10.15171/hpp.2019.38 .

Miech RA, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, Patrick ME. E-cigarettes and the drug use patterns of adolescents. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;18(5):654–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntv217 .

Schleimer JP, Rivera-Aguirre AE, Castillo-Carniglia A, Laqueur HS, Rudolph KE, Suárez H, et al. Investigating how perceived risk and availability of marijuana relate to marijuana use among adolescents in Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay over time. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;201:115–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.03.029 .

Traube DE, Yarnell LM, Schrager SM. Differences in polysubstance use among youth in the child welfare system: toward a better understanding of the highest-risk teens. Child Abuse Negl. 2016;52:146–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.11.020 .

Wilson JD, Vo H, Matson P, Adger H, Barnett G, Fishman M. Trait mindfulness and progression to injection use in youth with opioid addiction. Subst Use Misuse. 2017;52(11):1486–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2017.1289225 .

Dash GF, Feldstein Ewing SW, Murphy C, Hudson KA, Wilson AC. Contextual risk among adolescents receiving opioid prescriptions for acute pain in pediatric ambulatory care settings. Addict Behav. 2020;104:106314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106314 Epub 2020 Jan 11. PMID: 31962289; PMCID: PMC7024039.

Osborne V, Serdarevic M, Striley CW, Nixon SJ, Winterstein AG, Cottler LB. Age of first use of prescription opioids and prescription opioid non-medical use among older adolescents. Substance Use Misuse. 2020;55(14):2420–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2020.1823420 .

Zuckermann AME, Qian W, Battista K, Jiang Y, de Groh M, Leatherdale ST. Factors influencing the non-medical use of prescription opioids among youth: results from the COMPASS study. J Subst Abus. 2020;25(5):507–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659891.2020.1736669 .

De Pedro KT, Esqueda MC, Gilreath TD. School protective factors and substance use among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adolescents in California public schools. LGBT Health. 2017;4(3):210–6. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2016.0132 .

Spillane NS, Schick MR, Kirk-Provencher KT, Hill DC, Wyatt J, Jackson KM. Structured and unstructured activities and alcohol and marijuana use in middle school: the role of availability and engagement. Substance Use Misuse. 2020;55(11):1765–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2020.1762652 .

Ogunsola OO, Fatusi AO. Risk and protective factors for adolescent substance use: a comparative study of secondary school students in rural and urban areas of Osun state, Nigeria. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2016;29(3). https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2015-0096 .

Doggett A, Qian W, Godin K, De Groh M, Leatherdale ST. Examining the association between exposure to various screen time sedentary behaviours and cannabis use among youth in the COMPASS study. SSM Population Health. 2019;9:100487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100487 .

Afifi RA, El Asmar K, Bteddini D, Assi M, Yassin N, Bitar S, et al. Bullying victimization and use of substances in high school: does religiosity moderate the association? J Relig Health. 2020;59(1):334–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-019-00789-8 .

El Kazdouh H, El-Ammari A, Bouftini S, El Fakir S, El Achhab Y. Adolescents, parents and teachers’ perceptions of risk and protective factors of substance use in Moroccan adolescents: a qualitative study. Substance Abuse Treat Prevent Policy. 2018;13(1):–31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-018-0169-y .

Sussman S, Lisha N, Griffiths M. Prevalence of the addictions: a problem of the majority or the minority? Eval Health Prof. 2011;34(1):3–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163278710380124 .

Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Schweizer S. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(2):217–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004 .

Ricketts T, Macaskill A. Gambling as emotion management: developing a grounded theory of problem gambling. Addict Res Theory. 2003;11(6):383–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/1606635031000062074 .

Williams AD, Grisham JR. Impulsivity, emotion regulation, and mindful attentional focus in compulsive buying. Cogn Ther Res. 2012;36(5):451–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-011-9384-9 .

National Institutes on Drug Abuse. Drugs, brains, and behavior the science of addiction national institute on drug abuse (nida). 2014. Retrieved from https://www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/soa_2014.pdf

Hokm Abadi ME, Bakhti M, Nazemi M, Sedighi S, Mirzadeh Toroghi E. The relationship between personality traits and drug type among substance abuse. J Res Health. 2018;8(6):531–40.

Longman-Mills S, Haye W, Hamilton H, Brands B, Wright MGM, Cumsille F, et al. Psychological maltreatment and its relationship with substance abuse among university students in Kingston, Jamaica, vol. 24. Florianopolis: Texto Contexto Enferm; 2015. p. 63–8.

Rosenkranz SE, Muller RT, Henderson JL. The role of complex PTSD in mediating childhood maltreatment and substance abuse severity among youth seeking substance abuse treatment. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy. 2014;6(1):25–33. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031920 .

Krishnan-Sarin S, Morean M, Kong G, et al. E-Cigarettes and “dripping” among high-school youth. Pediatrics. 2017;139(3). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-3224 .

Adinoff B. Neurobiologic processes in drug reward and addiction. Harvard review of psychiatry. NIH Public Access. 2004;12(6):305–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/10673220490910844 .

Kandel D, Kandel E. The gateway hypothesis of substance abuse: developmental, biological and societal perspectives. Acta Paediatrica. 2014;104(2):130–7.

Dempsey RC, McAlaney J, Helmer SM, Pischke CR, Akvardar Y, Bewick BM, et al. Normative perceptions of Cannabis use among European University students: associations of perceived peer use and peer attitudes with personal use and attitudes. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2016;77(5):740–8.

Cioffredi L, Kamon J, Turner W. Effects of depression, anxiety and screen use on adolescent substance use. Prevent Med Rep. 2021;22:101362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101362 .

Luckett T, NewtonJohn T, Phillips J, et al. Risk of opioid misuse in people with cancer and pain and related clinical considerations:a qualitative study of the perspectives of Australian general practitioners. BMJ Open. 2020;10(2):e034363. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034363 .

Lipari RN. Trends in Adolescent Substance Use and Perception of Risk from Substance Use. The CBHSQ Report. Substance Abuse Mental Health Serv Admin. 2013; Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27656743 .

Muchiri BW, dos Santos MML. Family management risk and protective factors for adolescent substance use in South Africa. Substance Abuse. 2018;13(1):24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-018-0163-4 .

Becoña E, Martínez Ú, Calafat A, Juan M, Fernández-Hermida JR, Secades-Villa R. Parental styles and drug use: a review. In: Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy: Taylor & Francis; 2012. https://doi.org/10.3109/09687637.2011.631060 .

Berge J, Sundel K, Ojehagen A, Hakansson A. Role of parenting styles in adolescent substance use: results from a Swedish longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(1):e008979. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008979 .

Opara I, Lardier DT, Reid RJ, Garcia-Reid P. “It all starts with the parents”: a qualitative study on protective factors for drug-use prevention among black and Hispanic girls. Affilia J Women Soc Work. 2019;34(2):199–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109918822543 .

Martínez-Loredo V, Fernández-Artamendi S, Weidberg S, Pericot I, López-Núñez C, Fernández-Hermida J, et al. Parenting styles and alcohol use among adolescents: a longitudinal study. Eur J Invest Health Psychol Educ. 2016;6(1):27–36. https://doi.org/10.1989/ejihpe.v6i1.146 .

Baharudin MN, Mohamad M, Karim F. Drug-abuse inmates maqasid shariah quality of lifw: a conceotual paper. Hum Soc Sci Rev. 2020;8(3):1285–94. https://doi.org/10.18510/hssr.2020.83131 .

Henneberger AK, Mushonga DR, Preston AM. Peer influence and adolescent substance use: a systematic review of dynamic social network research. Adolesc Res Rev. 2020;6(1):57–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-019-00130-0 Springer.

Gomes FC, de Andrade AG, Izbicki R, Almeida AM, de Oliveira LG. Religion as a protective factor against drug use among Brazilian university students: a national survey. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2013;35(1):29–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbp.2012.05.010 .

Kulis S, Hodge DR, Ayers SL, Brown EF, Marsiglia FF. Spirituality and religion: intertwined protective factors for substance use among urban American Indian youth. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38(5):444–9. https://doi.org/10.3109/00952990.2012.670338 .

Miller L, Davies M, Greenwald S. Religiosity and substance use and abuse among adolescents in the national comorbidity survey. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39(9):1190–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200009000-00020 .

Moon SS, Rao U. Social activity, school-related activity, and anti-substance use media messages on adolescent tobacco and alcohol use. J Hum Behav Soc Environ. 2011;21(5):475–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2011.566456 .

Simone A. Onrust, Roy Otten, Jeroen Lammers, Filip smit, school-based programmes to reduce and prevent substance use in different age groups: what works for whom? Systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;44:45–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.11.002 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge The Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia and The Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, (UKM) for funding this study under the Long-Term Research Grant Scheme-(LGRS/1/2019/UKM-UKM/2/1). We also thank the team for their commitment and tireless efforts in ensuring that manuscript was well executed.

Financial support for this study was obtained from the Ministry of Higher Education, Malaysia through the Long-Term Research Grant Scheme-(LGRS/1/2019/UKM-UKM/2/1). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Community Health, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Cheras, 56000, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Azmawati Mohammed Nawi, Mohd Rohaizat Hassan & Mohd Rizal Abdul Manaf

Centre for Research in Psychology and Human Well-Being (PSiTra), Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 43600, Bangi, Selangor, Malaysia

Rozmi Ismail, Fauziah Ibrahim & Nurul Shafini Shafurdin

Clinical Psychology and Behavioural Health Program, Faculty of Health Sciences, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Noh Amit & Norhayati Ibrahim

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Manuscript concept, and drafting AMN and RI; model development, FI, NI and NA.; Editing manuscript MRH, MRAN, NSS,; Critical revision of manuscript for important intellectual content, all authors. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Rozmi Ismail .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Secretariat of Research Ethics, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Faculty of Medicine, Cheras, Kuala Lumpur (Reference no. UKMPPI/111/8/JEP-2020.174(2). Dated 27 Mac 2020.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors AMN, RI, FI, MRM, MRAM, NA, NI NSS declare that they have no conflict of interest relevant to this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Nawi, A.M., Ismail, R., Ibrahim, F. et al. Risk and protective factors of drug abuse among adolescents: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 21 , 2088 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11906-2

Download citation

Received : 10 June 2021

Accepted : 22 September 2021

Published : 13 November 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11906-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Drug abuse, substance, adolescent

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Prevention of Substance Use among the Youth: A Public Health Priority

- First Online: 12 January 2022

Cite this chapter

- Kegomoditswe Manyanda 2 ,

- David Sidney Mangwegape 3 ,

- Wazha Dambe 4 &

- Ketwesepe Hendrick 5

197 Accesses

Excessive substance consumption is a growing public health concern globally as it alters the optimal function of the human brain, leading to severe physiological, psychological, and social problems. Compelling evidence shows that certain groups of people may be more vulnerable to substance use and misuse than members of the general population. These groups, sometimes referred to as “special populations” have unique health concerns that require exceptional attention in the prevention of substance use/misuse. Special populations include among others the poor or homeless, women, young adults or teenagers, the elderly, and trauma survivors. The focus of this chapter is on the prevention of substance use and misuse in young people and teenagers, including those that are homeless. Young people engage in substance use due to peer pressure or as a way of experimentation and, therefore, are more vulnerable. Several factors linked to substance use disorders among teenagers are also discussed. The chapter also utilises both primary and secondary data focusing on substance-related disorders in adolescents, enhancing resilience and methods for reducing risk behaviour. Challenges as well as best practices and recommendations for addressing stigma, treatment needs, the support structures needed for effective prevention of substance use in young people are also discussed.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Babalola, E. O., Ogunwale, A., & Akinhami, A. (2013). Pattern of psychoactive substance use among university students in South-Western Nigeria. Journal of Behavioural Health, 2 (4), 344–342. https://doi.org/10.5455/jbh.20130921013013 .

Article Google Scholar

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1992). Ecological systems theory. In R. Vasta (Ed.), Six theories of child development: Revised formulations and current issues (pp. 187–249). Jessica Kinsley Publishers.

Google Scholar

Cumber, S. N., & Tsoka-Gwegweni, S. N. (2015). The health profile of street children in Africa: A literature review. Journal of Public Health in Africa, 6 (2), 566. https://doi.org/10.4081.jphia.2015.566

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Diraditsile, K., & Mabote, O. (2017). Alcohol and substance abuse in secondary schools in Botswana: The need for social workers in the school system. Journal of Sociology, Psychology and Anthropology in Practice, 8 (2), 90–102.

Fry, C., Nikpay, S., Leslie, E., & Buntin, M. (2018). Evaluating community-based health improvement programs. Health Affairs, 37 (1), 22–29.

Gilinsky, A., Swanson, V., & Power, K. (2011). Interventions delivered during antenatal care to reduce alcohol consumption during pregnancy: A systematic review. Addiction Research & Theory, 19 (3), 235–250. https://doi.org/10.3109/16066359.2010.507894 .

Gotsang, G., Mashalla, Y., & Seloilwe, E. (2017). Perceptions of school going adolescents about substance abuse in Ramotswa, Botswana. Journal of Public Health and Epidemiology, 9 (6), 151–160. https://doi.org/10.5899/JPHE2017.0930

Griffin, K. W., & Botvin, G. J. (2010). Evidence based interventions for preventing substance use disorders in adolescents. Child Adolescent Psychiatry Clinics of North America, 19 (5), 505–526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2010.03.005

Hodgson, K. J., Shelton, K. H., Van den Bree, M. B., & Los, F. J. (2013). Psychopathology in young people experiencing homelessness: A systematic review. American Journal of Public Health, 103 , e24–e37.

Keetile, M. (2020). Patterns and correlates of health risk behaviours among adolescents in Botswana: 2001–2013. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies . https://doi.org/10.1080/17450128.2020.1752961

Kumpfer, K. L. (2014). Family based interventions for the prevention of substance abuse and other impulse control disorders in girls. ISRN Addiction . https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/308789

Lochman, J. E., & van den Steenhoven, A. (2002). Family-based approaches to substance abuse prevention. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 23 , 49–114. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016591216363

Ludick, W. K., & Amone-P’Olak, K. (2016). Temperament and the risk of alcohol, tobacco and cannabis use among university students in Botswana. African Journal of Drug & Alcohol Studies, 15 (1), 21–35.

Mufune, P. (2002). Street youth in Southern Africa. International Social Science Journal . https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2451.002

Nsimba, S. E. D., & Massele, A. Y. (2012). A review on school-based interventions for alcohol, tobacco and other drugs (ATOD) in the United States of America; can developing countries in Africa adopt these preventive programs based on ATOD approaches? Journal of Addiction Research and Therapy . https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-6105.S2-007

O’Dowd, A. (2020). Drug misuse rose 30% in past decade and COVID-19 could worsen situation: UN report warns. British Medical Journal . https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m2631

Olashore, A. A., Ogunwobi, O., Totego, E., & Opondo, P. R. (2018). Psychoactive substance use among first-year students in a Botswana university: Pattern and correlates. BMC Psychiatry, 18 , 270. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1844-2

Olawole-Isaac, A., Ogundipe, O., Amoo, O., & Adeloye, D. (2018). Substance use among adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. South African Journal of Child Health, 1 (12), 79–84. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAJCH.2018.v12i2.1524

Riva, K., Allen-Taylor, L., Schupmann, W. D., Mphele, S., Moshashane, N., & Lowenthal, E. D. (2018). Prevalence and predictors of alcohol and drug use among secondary school students in Botswana: A cross sectional study. BMC Public Health, 18 , 1396. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6263-2

Rose-Clarke, K., Bentley, A., Marston, C., & Prost, A. (2019). Peer-facilitated community-based interventions for adolescent health in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. PLoS One, 14 (1), e0210468. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210468

Selemogwe, M., Mphele, S., & Manyanda, K. (2014). Drug use patterns and socio-demographic profits of substance users: Findings from a substance abuse treatment programme in Gaborone, Botswana. African Journal of Drug & Alcohol Studies, 13 (1) 43–53.

Slade, E. P., Stuart, E. A., Salkever, D. S., Karakus, M., Green, K. M., & Ialongo, N. (2008). Impacts of age of onset of substance use disorders on risk of adult incarceration among disadvantaged urban youth: A propensity score matching approach. Drugs and Alcohol Dependence, 95 (1–2), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.11.019

Stangl, A. L., Eearnshaw, V. A., Logie, C. H., Van Brakel, W., Simbayi, L. C., Barre, I., & Dovidio, J. F. (2019). The health stigma and discrimination framework: A global, cross cutting framework to inform research, intervention development, and policy on health-related stigmas. BMC Medicine, 17 (31). https://doi.org/10.1186/s129-019-1271-3

Souza, R., Porten, K., Nicholas, S. & Grais, R. (2010). Outcomes for street children and youth under multidisciplinary care in a drop in centre in Tegucigalpa, Honduras. International Journal of Social Psychiatry , 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764010382367

Swadi, H. (1999). Individual risk factors for adolescent substance use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 55 (3), 209–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0376-8716(99)00017-4

Swahn, M. H., Bossarte, R. M., Palmier, J. B., & Yao, H. (2013). Co-occurring physical fighting and suicide attempts among U.S. high school students: Examining patterns of early alcohol use initiation and current binge drinking. The Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 14 (4), 341–346. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2013.3.15705

Tremblay, M., Baydala, L., Khan, M., Currie, C., Morley, K., Burkholder, C., … Stillar, A. (2020). Primary substance use prevention programs for children and youth: A systematic review. Paediatrics, 146 (3). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-2747

United Nations. (2008). Definition of youth . United Nations. https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/documents/youth/fact-sheets/youth-definition.pdf

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2009). Guide to implementing family skills training programmes for drug abuse prevention . United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. https://www.unodc.org/documents/prevention/family-guidelines-E.pdf

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2013). International standards on drug use prevention . United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2017). Prevention of drug use and treatment of drug use disorders in rural settings: Revised version . United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2019). Summary table of evidence-based strategies identified in the UNODC/ WHO international standards on drug use prevention . United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2020). World drug report . United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. https://wdr2020.index.html

Valero de Vicente, M., Lluis, B. B., Orte Socias, M. D. M., & Amer Fernandez, J. A. (2017). Meta-analysis of family-based selective prevention programs for drug consumption in adolescence. Psicothema, 29 (3), 299–305. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2016.275

PubMed Google Scholar

World Health Organisation. (2003). Substance use in Southern Africa: Knowledge, attitudes, practices and opportunities for intervention . World Health Organisation.

Zwick, J., Appleseth, H., & Arndt, S. (2020). Stigma: How it affects the substance use disorder patient. Substance Abuse Treatment Prevention Policy, 15 , 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-020-00288-0

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Aspire Health Services Group, Gaborone, Botswana

Kegomoditswe Manyanda

Institute of Health Sciences-Lobatse, Department of Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing, Lobatse, Botswana

David Sidney Mangwegape

BOSASNet, Gaborone, Botswana

Wazha Dambe

Department of Psychology, University of Botswana, Gaborone, Botswana

Ketwesepe Hendrick

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Botswana, Gaborone, Botswana

Magen Mhaka-Mutepfa

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Manyanda, K., Mangwegape, D.S., Dambe, W., Hendrick, K. (2021). Prevention of Substance Use among the Youth: A Public Health Priority. In: Mhaka-Mutepfa, M. (eds) Substance Use and Misuse in sub-Saharan Africa. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-85732-5_10

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-85732-5_10

Published : 12 January 2022

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-85731-8

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-85732-5

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

The prevalence and determinant factors of substance use among the youth in ethiopia: a multilevel analysis of ethiopian demographic and health survey.

- 1 Department of Psychiatry, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Gondar, Gondar, Ethiopia

- 2 Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Institute of Public Health, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Gondar, Gondar, Ethiopia

- 3 Department of Pediatrics, School of Nursing, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Gondar, Gondar, Ethiopia

- 4 Department of Emergency Medicine and Critical Care Nursing, School of Nursing, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Gondar, Gondar, Ethiopia

- 5 Department of Community Health Nursing, School of Nursing, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Gondar, Gondar, Ethiopia

Background: In Ethiopia, the youth are more exposed to substances such as alcohol, Khat, and tobacco than other populations. Despite the seriousness of the situation, low- and middle-income nations, particularly Ethiopia, have intervention gaps. Service providers must be made more aware of relevant evidence to combat these problems. This research focused on finding out how common substance abuse is among teenagers and the factors that influence it.

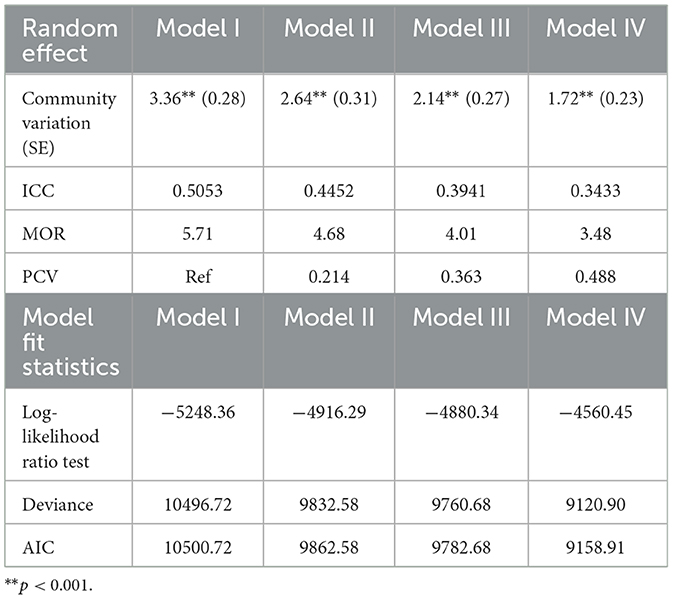

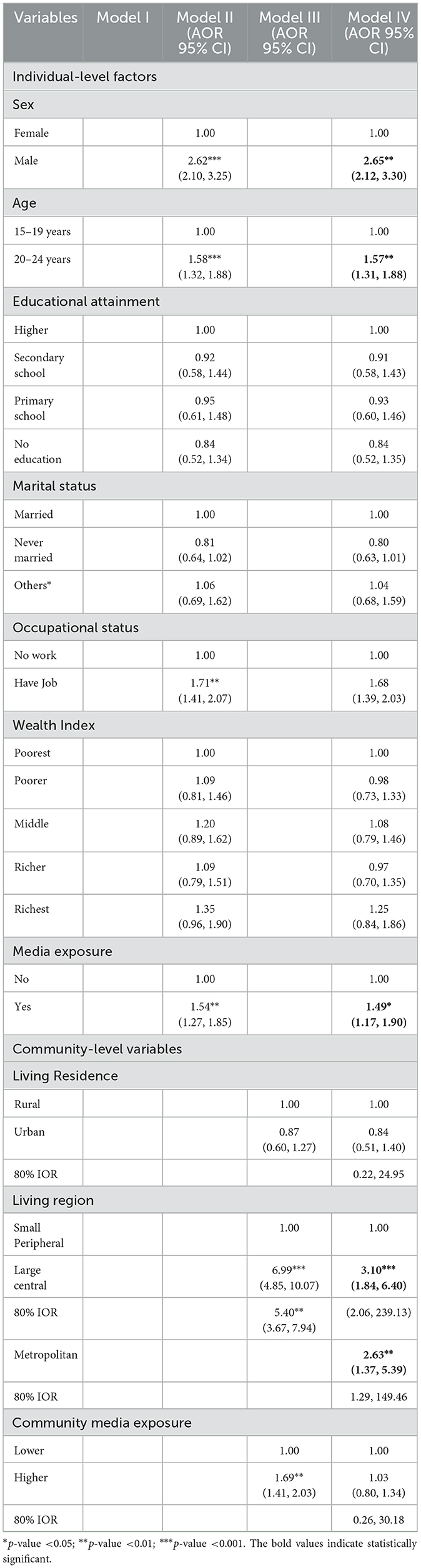

Methods: The 2016 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey data were used for secondary data analysis. This survey includes all young people aged 15 to 24 years. The total sample size was 10,594 people. Due to the hierarchical nature of the survey data, a multilevel logistic regression model was employed to uncover the individual- and community-level characteristics related to substances.

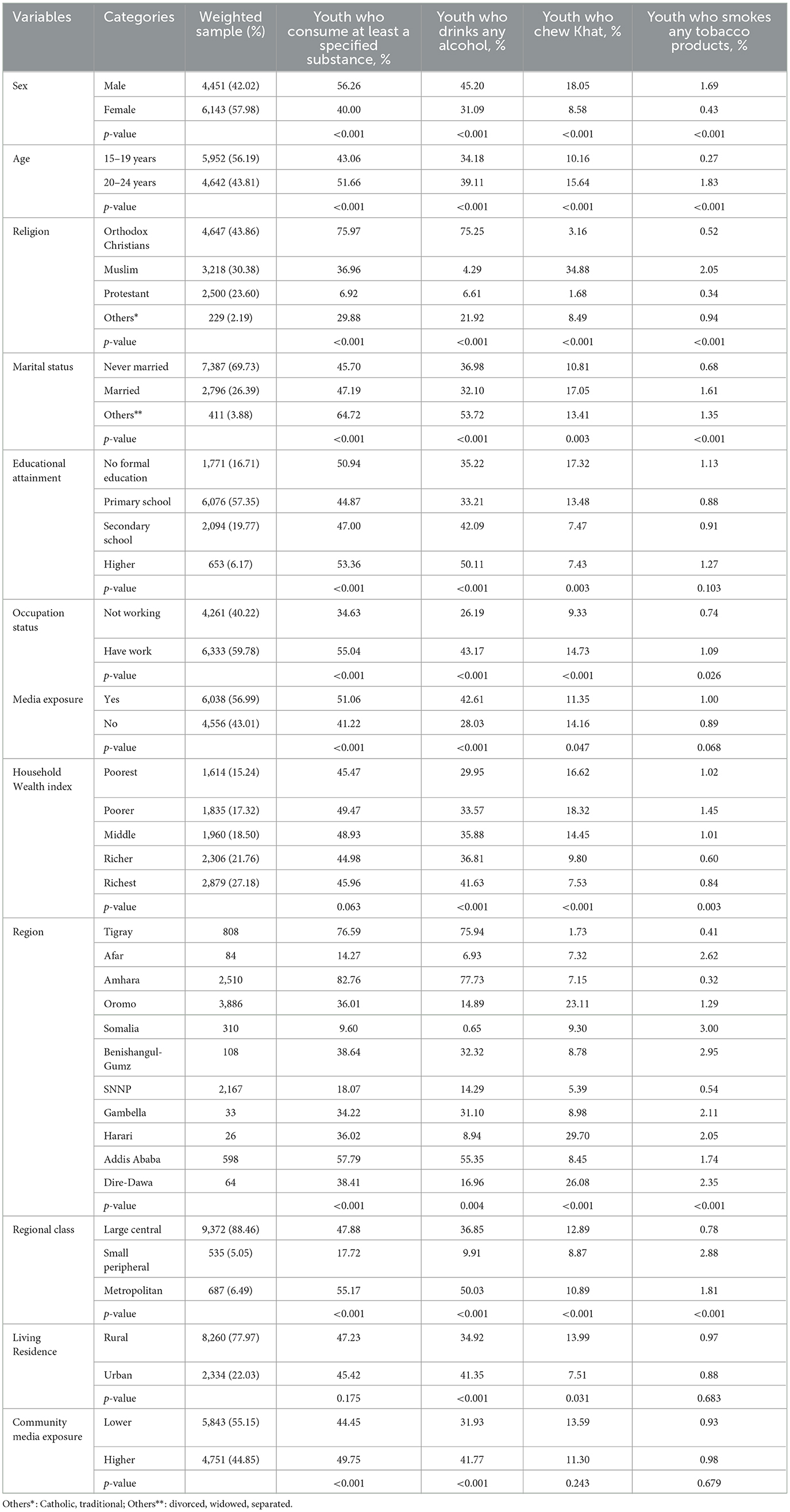

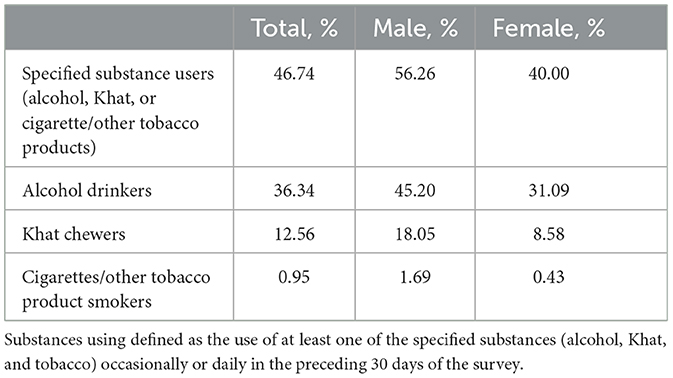

Results: In Ethiopia, the overall current prevalence of occasional or daily substance use 30 days prior to the survey was 46.74%. Of the participants, 36.34, 12.56, and 0.95% were drinking alcohol, chewing Khat, and smoking cigarettes/any tobacco products, respectively. Male sex, 20–24 years of age, exposure to media, having a job, and living in large central and metropolitan regions were the factors associated with the problem.

Conclusion: According to the 2016 EDHS, substance use among young people is widespread in Ethiopia. To lower the prevalence of substance use among youth, policymakers must increase the implementation of official rules, such as restricting alcohol, Khat, and tobacco product marketing to minors, prohibiting smoking in public places, and banning mass-media alcohol advertising. Specific interventions targeting at-risk populations, such as youth, are mainly required in prominent central and metropolitan locations.

Introduction

Substance abuse has become a significant public health issue due to its widespread prevalence across all socioeconomic groups. It has a broad detrimental influence on socioeconomic development and severely endangers public health ( 1 – 3 ). According to a worldwide addiction report in 2017, 1 in 20 to 1 in 5 people aged 15 years and above highly use alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drugs daily ( 4 ). Youth includes late adolescents and young adults aged 15 to 24 years ( 5 , 6 ) who experience substantial changes in numerous facets of life throughout their youthhood, such as rapid physical growth and cognitive, moral, and emotional developments ( 7 , 8 ). If not properly managed, the youth are prone to risk-taking behaviors, including substance use ( 9 , 10 ). In the general population, late adolescence and youth are the vital phases at which substance use starts and reaches a peak ( 11 , 12 ). Alcohol, cigarettes, and cannabis have remained the most regularly consumed substances among youngsters worldwide ( 13 , 14 ). In Ethiopia, adolescents are particularly vulnerable to substances such as alcohol, Khat, and tobacco products ( 15 – 17 ). While alcohol is the most commonly used and abused substance, tobacco has the highest fatality rate ( 4 ). Shisha is another psychoactive substance commonly used in Shashemene town of southern Ethiopia. Shisha is smoking heated, specially prepared tobacco through a pipe. Shisha is also called a water pipe or a Hubble bubble. Like cigarettes, shisha can contain nicotine psychoactive ingredients.

As a result of increased sexual activity, youth who abuse substances are at a higher risk of unintentional injury and death (e.g., automobile accidents and suicide), overdose, and sexually transmitted infections ( 18 – 20 ). The influence of substances alters the mental state of people, increasing the chances of driving accidents and sexually transmitted diseases. Alcoholism and car accidents are well-studied risk factors for injuries and deaths, and substance-induced driving impairment is of increasing concern in many countries around the globe ( 21 ). Approximately 54% of sexually transmitted diseases and their associated consequences on Ethiopian patients with HIV/AIDS have been shown to be related to substance use ( 22 ). Long-term use increases the risk of several medical illnesses, such as lung disease, heart disease, liver disease, cancer, and psychological issues, such as anxiety, depression, bipolar and psychotic disorders, suicide, and violence ( 19 , 23 , 24 ). Substance abuse has a substantial financial impact due to lost production, deaths, and healthcare costs ( 13 ). Furthermore, substance addiction exposes individuals to polysubstance abuse and negatively impacts their quality of life in various ways, including their physical, psychological, social, and environmental activities ( 25 – 27 ).

According to different literature, the prevalence of substance abuse among adolescents varies depending on the substance. For example, people who use substances such as alcohol, Khat, and tobacco ranged from 11.3 to 60%, 9.7 to 74%, and 2 to 56.5%, respectively ( 16 , 17 , 28 ). The combined prevalence of regular or occasional alcohol consumption among youth in eastern Africa was 52 and 15%, respectively ( 29 ). In Ethiopia, a systematic review found that youth had a much greater rate of substance use, including alcohol, Khat, and cigarette products, than the general population ( 19 ). Another study among high school and university students found that 52.5% have used some substance at some point in their lives, with alcohol accounting for 46.2%, Khat for 24.7%, and smoking cigarettes for 14.7% ( 30 ). This demonstrates a disparity across several geographical contexts and time eras. Furthermore, a recent study of university students in Ethiopia found that drinking alcohol, smoking tobacco products, and chewing Khat was attributed to 26.65, 6.83, and 13.13% of youth, respectively ( 31 ).

Although substance abuse is a frequent problem among young people, evidence suggests that various factors contribute to its prevalence. Young adults (18–24 years), male sex, living in a divorced/separated family, urban location, unemployment, drug availability, and being out of school are some of the characteristics that increase the chances of substance use among those population groups in low- and middle-income nations ( 32 – 35 ). The sociodemographic factors linked with high substance use are also marital status, religion, higher educational achievement (college and university education), and high income ( 36 – 38 ). Other risk factors for juvenile substance use were peer pressure, having a family member who uses substances, and residing in large cities and regions ( 16 , 32 , 34 , 35 , 39 ). People also use substances for a variety of reasons, including pleasure, coping with life's challenges, stress and depression relief, staying alert while reading, and improving performance, a lack of alternative forms of recreation in their living environment, high income, and academic dissatisfaction ( 16 , 28 , 40 ). In addition, substance advertising and promotion using mass media are other important factors that engage youth to initiate substance use ( 41 ).