Home > RHETDRAGONSSTUDENTWRITING > RHETDRAGONSRESEARCHINQUIRY

Research Inquiry

Through the research inquiry assignment, students will:.

- Use composing and reading for inquiry, learning, critical thinking, and communicating in various rhetorical contexts

- Use strategies – such as interpretation, synthesis, response, critique, and design/redesign – to compose texts that integrate their ideas with those from appropriate sources

- Locate and evaluate (for credibility, sufficiency, accuracy, timeliness, bias and so on) primary and secondary research materials, including journal articles and essays, books, scholarly and professionally established and maintained databases or archives, and informal electronic networks and internet sources

Things to keep in mind about research inquiry:

How Much Longer will African Americans be Disenfranchised? (2023-2024)

Pierce Burm

In this research inquiry, Burm synthesizes many legal and legislative sources to demonstrate the disenfranchisement and systemic racism against African Americans attempting to exercise their right to vote. In particular, Burm presents specific examples from Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee. However, Burm concludes the essay with the reminder that unless we are vigilant and strict bills are passed to counteract voter suppression, this is an issue that will continue and become even more prevalent. The outcome is that African American voters will have the impact of their votes even further diminished.

Camp in the Rocky Horror Picture Show (2023-2024)

Anthony Cawley

In this research inquiry, Cawley examines the film, Rocky Horror Picture Show , as an example of a “perfect camp film.” He arrives at this conclusion based on his interpretation of the film itself as the main source and by synthesizing other sources on film theory, film analysis, and theories of camp, such as Susan Sontag’s Notes on Camp .

Rocky IV as a Groundbreaking Film (2023-2024)

Matthew Croote

In this research inquiry example, Croote analyzes a later film in the Rocky franchise in order to argue for its understanding as a groundbreaking film. His argument takes up three major points—that Rocky IV is an effective reflection of Cold War events of the time, that Rocky IV deftly uses sport as a vehicle for its narrative, and that Rocky IV maintains its main message and cohesion within the franchise by entertaining audiences. Within the research and sources cited in this piece, Croote unpacks visual representations of characters, stereotypes and possible propaganda, and the metaphors of training to explore Cold War tensions. Ultimately, Croote also acknowledges but argues against the idea of the film as purely propaganda, but instead a popular film exerting its influence in delivering a slightly different message ahead of Cold War de-escalation.

Examining Conspiracy Theories: Reevaluating the Assumption that Their Supporters are Paranoid (2023-2024)

Soren C. Jung

In this research inquiry, Jung examines the definition and history of conspiracy theories in order to explore new reasons why they may remain so popular, while so commonly being denounced. In his essay, Jung reviews past histories of corporations acting only in favor of maximizing profits, such as the notorious Big Tobacco companies’ “Operation Berkshire.” Jung then juxtaposes knowledge of that history with various contemporary conspiracy theories related to the dangers, risk, or surveillance-related intent of Covid-19 vaccines. Jung concludes his piece with a reminder about the very real consequences of immediate infection and long-term health consequences of Covid-19, and that these are not speculative. However, he cautions that it does a disservice to dismiss believers in vaccine conspiracy theories as “simply paranoid” or uneducated when this belief most likely stems from anxiety of the unknown and fear of past corporate corruption.

Sanctioned Violence (2021-2022)

Jordanne Greenidge

In this research inquiry Greenidge uses Claudia Rankine’s work and a reading of the Rodney King video to question and argue against the sharing of viral videos (such as that of George Floyd or Eric Garner) that depict suffering, brutality, and the murder of Black people. Greenidge’s claim is that while some may share these images in the hopes of supporting movements, such as Black Lives Matter, or creating justice through awareness, the actual sharing of these videos creates desensitization and normalizes acts of violence toward Black victims. Instead of focusing on Black suffering, Greenidge calls for media and the public to focus more on countering white supremacy and the perpetrators of these violent acts.

Tragic Hero (2021-2022)

Nicholas Lardaro

In this research inquiry essay Lardaro uses the literary trope of the tragic hero to make a case for why Revenge of the Sith is an especially compelling film. Lardaro presents sources that help him to analyze how the downfall of Anakin Skywalker becomes an example of a tragic hero. His argument maintains that the treatment of Anakin Skywalker as a tragic hero is what allows the Star Wars prequels to offer emotional complexity and the potential for misinterpretation to the audience. This is in turn what makes these films compelling.

The Effects of Misrepresentation (2020-2021)

Miranda R. Cobo

This example of a research inquiry investigates issues of representation in the comic, Black Panther. Cobo writes: “In the 1960s, Stan Lee and Jack Kirby introduced T’Challa, famously known as the Black Panther. He was the first black superhero to be introduced in the Marvel Universe and into popular American comics. The world that Black Panther lived in is very advanced and breaks the stereotype of the view that many Americans have on Africa. However, that is only one stereotype that it has worked against. There have been many other stereotypes that writers use in T’Challa’s storyline that can be detrimental to making progress against racism. When creating black characters, many times they were not able to amount to the status that white characters have because of the lack of representation. Many authors have written about this topic trying to analyze why misrepresentation keeps happening and how it can be fixed. Through analysis and research, it is clear that there is still a long way to go in order for minorities to be properly portrayed in the media.”

Illegitimate Control: An Acknowledgement of False White Supremacy (2020-2021)

Whitman Ives

This research inquiry introduces a timely conversation on racism, cultural appropriation, and white supremacy. Ives’ argument is that the root cause of cultural appropriation and racism can be traced to a negative and false history of white supremacy. In other words, white culture has been founded and perpetuated based on power-seeking behavior, of which racism is more a symptom. Ives asserts that it is important to acknowledge that white culture is based on false assumptions of supremacy and to address that more systematically rather than addressing only individual events or instances of racism.

Child Protection Services: The Developmental Consequences of Arbitrary Removal (2020-2021)

John Jackson

This research inquiry example details the developmental consequences for children removed from their biological homes by Children’s Services. Jackson uses sources to discuss physical, mental, and emotional implications for removing children from their homes or parents in their future development as both children and adults. Not only does Jackson present an alternative perspective thinking about negative consequences and how the process of removal puts parents at odds with regaining custody, but he also proposes an alternative solution in the conclusion.

The Doppelganger Effect (2020-2021)

Jessica Jean-Baptiste

In this example of a research inquiry, Jean-Baptiste focuses on the use of cameras and mirrors to create doubles, or “doppelgangers” for the character of Nina in the film, Black Swan. In thinking about the “doppelganger effect,” Jean-Baptiste moves through an argument for how doubling fulfills not only one purpose or message within the film, but three. Her claim in synthesizing multiple sources of film analysis is that the doppelganger allows Aronofsky to comment on mental disorders, sexism within the community of ballet, and the overall mood for the film as a thriller as opposed to only a drama.

The Medical Ethics of HeLa Cells (2020-2021)

Elizabeth Pratt

Pratt’s research inquiry essay focuses on the medical ethics issues involved in the case of Henrietta Lacks and her cancer cells (known as HeLa,) which have been used and reused in medical research without hers or her family’s consent. Throughout this essay, Pratt moves between several areas for concern including medical agency and patients’ rights to their own bodies, financial implications, legal definitions, and issues for privacy. Pratt concludes with a call for future regulations and focus on medical ethics.

Guilty Until Proven Innocent (2019-2020)

Jacob Anderson

In this student example, Robinson addresses wrongful convictions, falsified evidence, and other major problems in the American justice system. Relying heavily on source material, Robinson confronts systemic problems by detailing the work of a particular nonprofit organization and highlighting the evidence for the necessity of that organization.

No One to Blame but Ourselves (2019-2020)

Shelby Soule

This example of a research inquiry involves moving through various historical developments and statistics related to climate change (such as rising global temperatures, sea levels, ice sheets, and carbon dioxide emissions) in order to then contextualize global efforts to reduce climate change damage, such as the Paris Agreement. Throughout the research inquiry Soule uses an objective stance in presenting findings and developments ranging from the 1700s to present times, and supporting a conclusion that global devastation may be as close as 2100.

Are Vaccines the Key to Alzheimer’s Treatment? (2019-2020)

In this research inquiry, Tyler uses a metacognitive style of reflection walking the reader through her personal connections to topic selection and research process before presenting what she discovered in medical journal articles on the topic of using vaccines for Alzheimer’s treatment and prevention. In closely reviewing journal articles and their findings, Tyler is able to make comments about the challenges of developing a vaccine appropriate to humans (as opposed to the mice trials she reads about,) and the complexity of high failure rates in the past. Finally, Tyler comments on the financial issues involved in this treatment plan and her own growth as a researcher.

- Collections

- Disciplines

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

Author Corner

- SUNY Cortland

- Memorial Library

- Digital Commons Policy

- Request a New Collection

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

4 Research Essay

Jeffrey Kessler

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to do the following:

- Construct a thesis based upon your research

- Use critical reading strategies to analyze your research

- Defend a position in relation to the range of ideas surrounding a topic

- Organize your research essay in order to logically support your thesis

I. Introduction

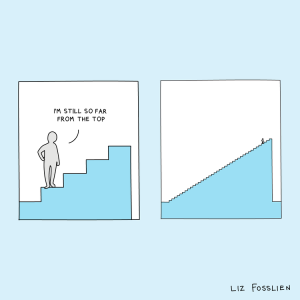

The goal of this book has been to help demystify research and inquiry through a series of genres that are part of the research process. Each of these writing projects—the annotated bibliography, proposal, literature review, and research essay—builds on each other. Research is an ongoing and evolving process, and each of these projects help you build towards the next.

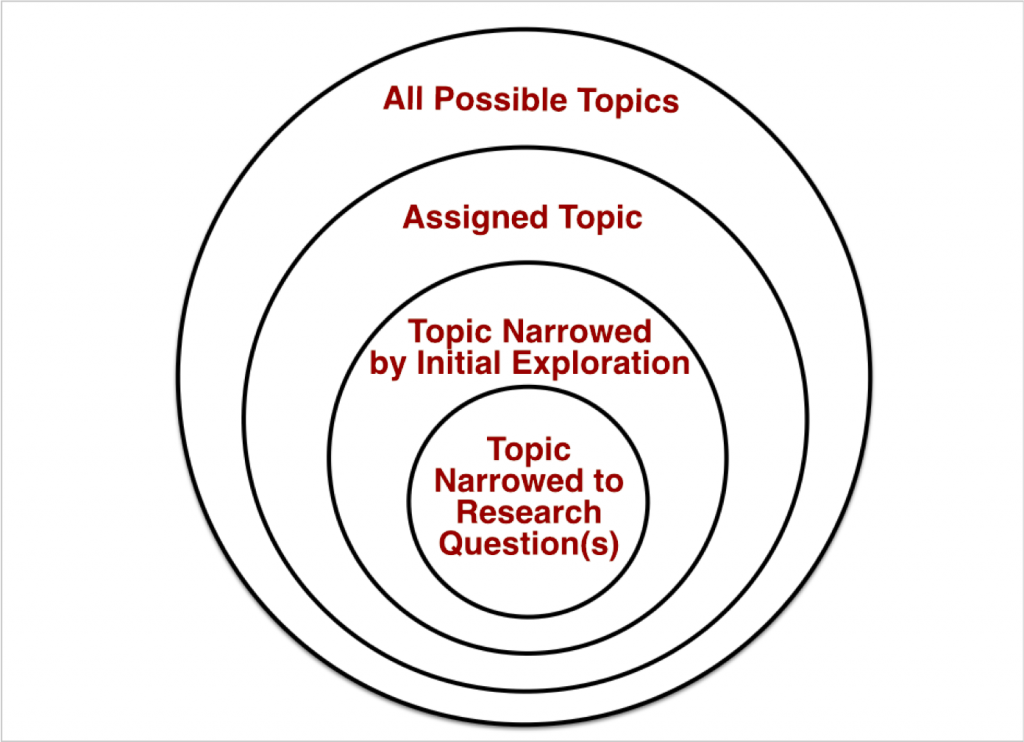

In your annotated bibliography, you started your inquiry into a topic, reading widely to define the breadth of your inquiry. You recorded this by summarizing and/or evaluating the first sources you examined. In your proposal, you organized a plan and developed pointed questions to pursue and ideas to research. This provided a good sense of where you might continue to explore. In your literature review, you developed a sense of the larger conversations around your topic and assessed the state of existing research. During each of these writing projects, your knowledge of your topic grew, and you became much more informed about its key issues.

You’ve established a topic and assembled sources in conversation with one another. It’s now time to contribute to that conversation with your own voice. With so much of your research complete, you can now turn your focus to crafting a strong research essay with a clear thesis. Having the extensive knowledge that you have developed across the first three writing projects will allow you to think more about putting the pieces of your research together, rather than trying to do research at the same time that you are writing.

This doesn’t mean that you won’t need to do a little more research. Instead, you might need to focus strategically on one or two key pieces of information to advance your argument, rather than trying to learn about the basics of your topic.

But what about a thesis or argument? You may have developed a clear idea early in the process, or you might have slowly come across an important claim you want to defend or a critique you want to make as you read more into your topic. You might still not be sure what you want to argue. No matter where you are, this chapter will help you navigate the genre of the research essay. We’ll examine the basics of a good thesis and argument, different ways to use sources, and strategies to organize your essay.

While this chapter will focus on the kind of research essay you would write in the college classroom, the skills are broadly applicable. Research takes many different forms in the academic, professional, and public worlds. Depending on the course or discipline, research can mean a semester-long project for a class or a few years’ worth of research for an advanced degree. As you’ll see in the examples below, research can consist of a brief, two-page conclusion or a government report that spans hundreds of pages with an overwhelming amount of original data.

Above all else, good research is engaged with its audience to bring new ideas to light based on existing conversations. A good research essay uses the research of others to advance the conversation around the topic based on relevant facts, analysis, and ideas.

II. Rhetorical Considerations: Contributing to the Conversation

The word “essay” comes from the French word essayer , or “attempt.” In other words, an essay is an attempt—to prove or know or illustrate something. Through writing an essay, your ideas will evolve as you attempt to explore and think through complicated ideas. Some essays are more exploratory or creative, while some are straightforward reports about the kind of original research that happens in laboratories.

Most research essays attempt to argue a point about the material, information, and data that you have collected. That research can come from fieldwork, laboratories, archives, interviews, data mining, or just a lot of reading. No matter the sources you use, the thesis of a research essay is grounded in evidence that is compelling to the reader.

Where you described the conversation in your literature review, in your research essay you are contributing to that conversation with your own argument. Your argument doesn’t have to be an argument in the cable-news-social-media-shouting sense of the word. It doesn’t have to be something that immediately polarizes individuals or divides an issue into black or white. Instead, an argument for a research essay should be a claim, or, more specifically, a claim that requires evidence and analysis to support. This can take many different forms.

Example 4.1: Here are some different types of arguments you might see in a research essay:

- Critiquing a specific idea within a field

- Interrogating an assumption many people hold about an issue

- Examining the cause of an existing problem

- Identifying the effects of a proposed program, law, or concept

- Assessing a historical event in a new way

- Using a new method to evaluate a text or phenomenon

- Proposing a new solution to an existing problem

- Evaluating an existing solution and suggesting improvements

These are only a few examples of the kinds of approaches your argument might take. As you look at the research you have gathered throughout your projects, your ideas will have evolved. This is a natural part of the research process. If you had a fully formed argument before you did any research, then you probably didn’t have an argument based on strong evidence. Your research now informs your position and understanding, allowing you to form a stronger evidence-based argument.

Having a good idea about your thesis and your approach is an important step, but getting the general idea into specific words can be a challenge on its own. This is one of the most common challenges in writing: “I know what I want to say; I just don’t know how to say it.”

Example 4.2: Here are some sample thesis statements. Examine them and think about their arguments.

Whether you agree, disagree, or are just plain unsure about them, you can imagine that these statements require their authors to present evidence, offer context, and explain key details in order to argue their point.

- Artificial intelligence (AI) has the ability to greatly expand the methods and content of higher education, and though there are some transient shortcomings, faculty in STEM should embrace AI as a positive change to the system of student learning. In particular, AI can prove to close the achievement gap often found in larger lecture settings by providing more custom student support.

- I argue that while the current situation for undocumented college students remains tumultuous, there are multiple routes—through financial and social support programs like the Fearless Undocumented Alliance—that both universities and colleges can utilize to support students affected by the reality of DACA’s shortcomings.

While it can be argued that massive reform of the NCAA’s bylaws is needed in the long run, one possible immediate improvement exists in the form of student-athlete name, image, and likeness rights. The NCAA should amend their long-standing definition of amateurism and allow student athletes to pursue financial gains from the use of their names, images, and likenesses, as is the case with amateur Olympic athletes.

Each of these thesis statements identifies a critical conversation around a topic and establishes a position that needs evidence for further support. They each offer a lot to consider, and, as sentences, are constructed in different ways.

Some writing textbooks, like They Say, I Say (2017), offer convenient templates in which to fit your thesis. For example, it suggests a list of sentence constructions like “Although some critics argue X, I will argue Y” and “If we are right to assume X, then we must consider the consequences of Y.”

More Resources 4.1: Templates

Templates can be a productive start for your ideas, but depending on the writing situation (and depending on your audience), you may want to expand your thesis beyond a single sentence (like the examples above) or template. According to Amy Guptill in her book Writing in Col lege (2016) , a good thesis has four main elements (pp. 21-22). A good thesis:

- Makes a non-obvious claim

- Poses something arguable

- Provides well-specified details

- Includes broader implications

Consider the sample thesis statements above. Each one provides a claim that is both non-obvious and arguable. In other words, they present something that needs further evidence to support—that’s where all your research is going to come in. In addition, each thesis identifies specifics, whether these are teaching methods, support programs, or policies. As you will see, when you include those specifics in a thesis statement, they help project a starting point towards organizing your essay.

Finally, according to Guptill, a good thesis includes broader implications. A good thesis not only engages the specific details of its argument, but also leaves room for further consideration. As we have discussed before, research takes place in an ongoing conversation. Your well-developed essay and hard work won’t be the final word on this topic, but one of many contributions among other scholars and writers. It would be impossible to solve every single issue surrounding your topic, but a strong thesis helps us think about the larger picture. Here’s Guptill:

Putting your claims in their broader context makes them more interesting to your reader and more impressive to your professors who, after all, assign topics that they think have enduring significance. Finding that significance for yourself makes the most of both your paper and your learning. (p. 23)

Thinking about the broader implications will also help you write a conclusion that is better than just repeating your thesis (we’ll discuss this more below).

Example 4.3: Let’s look at an example from above:

This thesis makes a key claim about the rights of student athletes (in fact, shortly after this paper was written, NCAA athletes became eligible to profit from their own name, image, and likeness). It provides specific details, rather than just suggesting that student athletes should be able to make money. Furthermore, it provides broader context, even giving a possible model—Olympic athletes—to build an arguable case.

Remember, that just like your entire research project, your thesis will evolve as you write. Don’t be afraid to change some key terms or move some phrases and clauses around to play with the emphasis in your thesis. In fact, doing so implies that you have allowed the research to inform your position.

Example 4.4: Consider these examples about the same topic and general idea. How does playing around with organization shade the argument differently?

- Although William Dowling’s amateur college sports model reminds us that the real stakeholders are the student athletes themselves, he highlights that the true power over student athletes comes from the athletic directors, TV networks, and coaches who care more about profits than people.

- While William Dowling’s amateur college sports model reminds us that the real stakeholders in college athletics are not the athletic directors, TV networks, and coaches, but the students themselves, his plan does not seem feasible because it eliminates the reason many people care about student athletes in the first place: highly lucrative bowl games and March Madness.

- Although William Dowling’s amateur college sports model has student athletes’ best interests in mind, his proposal remains unfeasible because financial stakeholders in college athletics, like athletic directors, TV networks, and coaches, refuse to let go of their power.

When you look at the different versions of the thesis statements above, the general ideas remain the same, but you can imagine how they might unfold differently in a paper, and even how those papers might be structured differently. Even after you have a good version of your thesis, consider how it might evolve by moving ideas around or changing emphasis as you outline and draft your paper.

More Resources 4.2: Thesis Statements

Looking for some additional help on thesis statements? Try these resources:

- How to Write a Thesis Statement

- Writing Effective Thesis Statements.

Library Referral: Your Voice Matters!

(by Annie R. Armstrong)

If you’re embarking on your first major college research paper, you might be concerned about “getting it right.” How can you possibly jump into a conversation with the authors of books, articles, and more, who are seasoned experts in their topics and disciplines? The way they write might seem advanced, confusing, academic, irritating, and even alienating. Try not to get discouraged. There are techniques for working with scholarly sources to break them down and make them easier to work with (see How to Read a Scholarly Article ). A librarian can work with you to help you find a variety of source types that address your topic in a meaningful way, or that one specific source you may still be trying to track down.

Furthermore, scholarly experts are not the only voices welcome at the research table! This research paper and others to come are an invitation to you to join the conversation; your voice and lived experience give you one-of-a-kind expertise equipping you to make new inquiries and insights into your topic. Sure, you’ll need to wrestle how to interpret difficult academic texts and how to piece them together. That said, your voice is an integral and essential part of the puzzle. All of those scholarly experts started closer to where you are than you might think.

III. The Research Essay Across the Disciplines

Example 4.5: Academic and Professional Examples

These examples are meant to show you how this genre looks in other disciplines and professions. Make sure to follow the requirements for your own class or to seek out specific examples from your instructor in order to address the needs of your own assignment.

As you will see, different disciplines use language very differently, including citation practices, use of footnotes and endnotes, and in-text references. (Review Chapter 3 for citation practices as disciplinary conventions.) You may find some STEM research to be almost unreadable, unless you are already an expert in that field and have a highly developed knowledge of the key terms and ideas in that field. STEM fields often rely on highly technical language and assume a high level of knowledge in the field. Similarly, humanities research can be hard to navigate if you don’t have a significant background in the topic or material.

As we’ve discussed, highly specialized research assumes its readers are other highly specialized researchers. Unless you read something like The Journ al of American Medicine on a regular basis, you usually learn about scientific or medical breakthroughs when they are reported by another news outlet, where a reporter makes the highly technical language of a scientific discovery more accessible for non-specialists.

Even if you are not an expert in multiple disciplines of study, you will find that research essays contain a lot of similarities in their structure and organization. Most research essays have an abstract that summarizes the entire article at the beginning. Introductions provide the necessary setup for the article. Body sections can vary. Some essays include a literature review section that describes the state of research about the topic. Others might provide background or a brief history. Many essays in the sciences will have a methodology section that explains how the research was conducted, including details such as lab procedures, sample sizes, control populations, conditions, and survey questions. Others include long analyses of primary sources, sets of data, or archival documents. Most essays end with conclusions about what further research needs to be completed or what their research further implies.

As you examine some of the different examples, look at the variations in arguments and structures. Just as in reading research about your own topic, you don’t need to read each essay from start to finish. Browse through different sections and see the different uses of language and organization that are possible.

IV. Research Strategies: When is Enough?

At this point, you know a lot about your topic. You’ve done a lot of research to complete your first three writing projects, but when do you have enough sources and information to start writing? Really, it depends.

If you’re writing a dissertation, you may have spent months or years doing research and still feel like you need to do more or to wait a few months until that next new study is published. If you’re writing a research essay for a class, you probably have a schedule of due dates for drafts and workshops. Either way, it’s better to start drafting sooner rather than later. Part of doing research is trying on ideas and discovering things throughout the drafting process.

That’s why you’ve written the other projects along the way instead of just starting with a research essay. You’ve built a foundation of strong research to read about your topic in the annotated bibliography, planned your research in the proposal, and understood the conversations around your topic in the literature review. Now that you are working on your research essay, you are far enough along in the research process where you might need a few more sources, but you will most likely discover this as you are drafting your essay. In other words, get writing and trust that you’ll discover what you need along the way.

V. Reading Strategies: Forwarding and Countering

Using sources is necessary to a research essay, and it is essential to think about how you use them. At this point in your research, you have read, summarized, analyzed, and made connections across many sources. Think back to the literature review. In that genre, you used your sources to illustrate the major issues, topics, and/or concerns among your research. You used those sources to describe and make connections between them.

For your research essay, you are putting those sources to work in a different way: using them in service of supporting your own contribution to the conversation. According to Joseph Harris in his book Rewriting (2017), we read texts in order to respond to them: “drawing from, commenting on, adding to […] the works of others” (p. 2). The act of writing, according to Harris, takes place among the different texts we read and the ways we use them for our own projects. Whether a source provides factual information or complicated concepts, we use sources in different ways. Two key ways to do so for Harris are forwarding and countering .

Forwarding a text means taking the original concept or idea and applying it to a new context. Harris writes: “In forwarding a text you test the strength of its insights and the range and flexibility of its phrasings. You rewrite it through reusing some of its key concepts and phrasings” (pp. 38-39). This is common in a lot of research essays. In fact, Harris identifies different types of forwarding:

- Illustrating: using a source to explain a larger point

- Authorizing: appealing to another source for credibility

- Borrowing: taking a term or concept from one context or discipline and using it in a new one

- Extending: expanding upon a source or its implications

It’s not enough in a research essay to include just sources with which you agree. Countering a text means more than just disagreeing with it, but it allows you to do more with a text that might not initially support your argument. This can include for Harris:

- Arguing the other side: oftentimes called “including a naysayer” or addressing objections

- Uncovering values: examining assumptions within the text that might prove problematic or reveal interesting insights

- Dissenting: finding the problems in or the limits of an argument (p. 58)

While the categories above are merely suggestions, it is worth taking a moment to think a little more about sources with which you might disagree. The whole point of an argument is to offer a claim that needs to be proved and/or defended. Essential to this is addressing possible objections. What might be some of the doubts your reader may have? What questions might a reasonable person have about your argument? You will never convince every single person, but by addressing and acknowledging possible objections, you help build the credibility of your argument by showing how your own voice fits into the larger conversation—if other members of that conversation may disagree.

VI. Writing Strategies: Organizing and Outlining

At this point you likely have a draft of a thesis (or the beginnings of one) and a lot of research, notes, and three writing projects about your topic. How do you get from all of this material to a coherent research essay? The following section will offer a few different ideas about organizing your essay. Depending on your topic, discipline, or assignment, you might need to make some necessary adjustments along the way, depending on your audience. Consider these more as suggestions and prompts to help in the writing and drafting of your research essay.

Sometimes, we tend to turn our research essay into an enthusiastic book report: “Here are all the cool things I read about my topic this semester!” When you’ve spent a long time reading and thinking about a topic, you may feel compelled to include every piece of information you’ve found. This can quickly overwhelm your audience. Other times, we as writers may feel so overwhelmed with all of the things we want to say that we don’t know where to start.

Writers don’t all follow the same processes or strategies. What works for one person may not always work for another, and what worked in one writing situation (or class) may not be as successful in another. Regardless, it’s important to have a plan and to follow a few strategies to get writing. The suggestions below can help get you organized and writing quickly. If you’ve never tried some of these strategies before, it’s worth seeing how they will work for you.

Think in Sections, Not Paragraphs

For smaller papers, you might think about what you want to say in each of the five to seven paragraphs that paper might require. Sometimes writing instructors even tell students what each paragraph should include. For longer essays, it’s much easier to think about a research essay in sections, or as a few connected short papers. In a short essay, you might need a paragraph to provide background information about your topic, but in longer essays—like the ones you have read for your project—you will likely find that you need more than a single paragraph, sometimes a few pages.

You might think about the different types of sections you have encountered in the research you have already gathered. Those types of sections might include: introduction, background, the history of an issue, literature review, causes, effects, solutions, analysis, limits, etc. When you consider possible sections for your paper, ask yourself, “What is the purpose of this section?” Then you can start to think about the best way to organize that information into paragraphs for each section.

Build an Outline

After you have developed what you want to argue with your thesis (or at least a general sense of it), consider how you want to argue it. You know that you need to begin with an introduction (more on that momentarily). Then you’ll likely need a few sections that help lead your reader through your argument.

Your outline can start simple. In what order are you going to divide up your main points? You can slowly build a larger outline to include where you will discuss key sources, as well as what are the main claims or ideas you want to present in each section. It’s much easier to move ideas and sources around when you have a larger structure in place.

Example 4.6: A Sample Outline for a Research Paper

- College athletics is a central part of American culture

- Few of its viewers fully understand the extent to which players are mistreated

- Thesis: While William Dowling’s amateur col lege sports model does not seem feasible to implement in the twenty-first century, his proposal reminds us that the real stakeholders in college athletics are not the athletic directors, TV networks, and coaches, but the students themselves, who deserve th e chance to earn a quality education even more than the chance to play ball.

- While many student athletes are strong students, many D-1 sports programs focus more on elite sports recruits than academic achievement

- Quotes from coaches and athletic directors about revenue and building fan bases (ESPN)

- Lowered admissions standards and fake classes (Sperber)

- Scandals in academic dishonesty (Sperber and Dowling)

- Some elite D-1 athletes are left in a worse place than where they began

- Study about athletes who go pro (Knight Commission, Dowling, Cantral)

- Few studies on after-effects (Knight Commission)

- Dowling imagines an amateur sports program without recruitment, athletic scholarships, or TV contracts

- Without the presence of big money contracts and recruitment, athletics programs would have less temptation to cheat in regards to academic dishonesty

- Knight Commission Report

- Is there any incentive for large-scale reform?

- Is paying student athletes a real possibility?

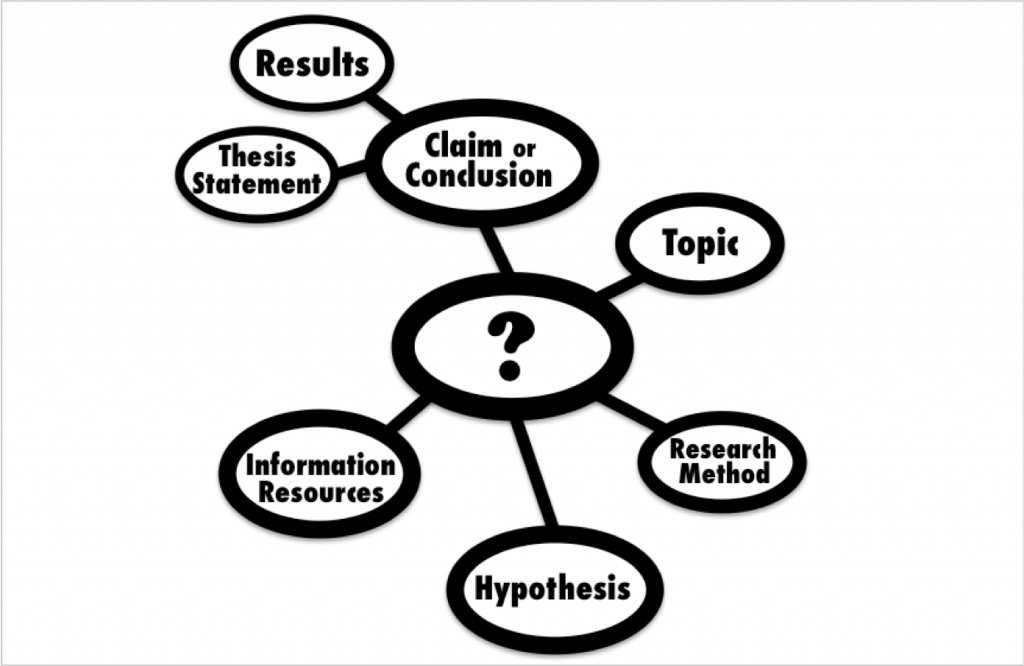

Some writers don’t think in as linear a fashion as others, and starting with an outline might not be the first strategy to employ. Other writers rely on different organizational strategies, like mind mapping, word clouds, or a reverse outline.

More Resources 4.3: Organizing Strategies

At this point, it’s best to get some writing done, even if writing is just taking more notes and then organizing those notes. Here are a few more links to get your thoughts down in some fun and engaging ways:

- Concept Mapping

- The Mad Lib from Hell: Three Alternatives to Traditional Outlining

- Thinking Outside the Formal Outline

- Mind Mapping in Research

- Reverse Outlining

Start Drafting in the Middle

This may sound odd to some people, but it’s much easier to get started by drafting sections from the middle of your paper instead of starting with the introduction. Sections that provide background or more factual information tend to be more straightforward to write. Sections like these can even be written as you are still finalizing your argument and organizational structure.

If you’ve completed the three previous writing projects, you will likely also funnel some of your work from those projects into the final essay. Don’t just cut and paste entire chunks of those other assignments. That’s called self-plagiarism, and since those assignments serve different purposes in different genres, they won’t fit naturally into your research essay. You’ll want to think about how you are using the sources and ideas from those assignments to serve the needs of your argument. For example, you may have found an interesting source for your literature review paper, but that source may not help advance your final paper.

Draft your Introduction and Conclusion towards the End

Your introduction and conclusion are the bookends of your research essay. They prepare your reader for what’s to come and help your reader process what they have just read. The introduction leads your reader into your paper’s research, and the conclusion helps them look outward towards its implications and significance.

Many students think you should write your introduction at the beginning of the drafting stage because that is where the paper starts. This is not always the best idea. An introduction provides a lot of essential information, including the paper’s method, context, organization, and main argument. You might not have all of these details figured out when you first start drafting your paper. If you wait until much later in the drafting stage, the introduction will be much easier to write. In fact, most academic writers and researchers wait until the rest of their project—a paper, dissertation, or book—is completed before they write the introduction.

A good introduction does not need to be long. In fact, short introductions can impressively communicate a lot of information about a paper when the reader is most receptive to new information. You don’t need to have a long hook or anecdote to catch the reader’s attention, and in many disciplines, big, broad openings are discouraged. Instead, a good introduction to a research essay usually does the following:

- defines the scope of the paper

- indicates its method or approach

- gives some brief context (although more significant background may be saved for a separate section)

- offers a road map

If we think about research as an ongoing conversation, you don’t need to think of your conclusion as the end—or just a repetition of your argument. No matter the topic, you won’t have the final word, and you’re not going to tie up a complicated issue neatly with a bow. As you reach the end of your project, your conclusion can be a good place to reflect about how your research contributes to the larger conversations around your issue.

Think of your conclusion as a place to consider big questions. How does your project address some of the larger issues related to your topic? How might the conversation continue? How might it have changed? You might also address limits to existing research. What else might your readers want to find out? What do we need to research or explore in the future?

You need not answer every question. You’ve contributed to the conversation around your topic, and this is your opportunity to reflect a little about that. Still looking for some additional strategies for introductions and conclusions? Try this additional resource:

More Resources 4.4: Introductions and Conclusions

If you’re a bit stuck on introductions and conclusions, check out these helpful links:

- Introductions & Writing Effective Introductions

- Guide to Writing Introductions and Conclusions

- Conclusions & Writing Effective Conclusions

Putting It All Together

This chapter is meant to help you get all the pieces together. You have a strong foundation with your research and lots of strategies at your disposal. That doesn’t mean you might not still feel overwhelmed. Two useful strategies are making a schedule and writing out a checklist.

You likely have a due date for your final draft, and maybe some additional dates for submitting rough drafts or completing peer review workshops. Consider expanding this schedule for yourself. You might have specific days set aside for writing or for drafting a certain number of words or pages. You can also schedule times to visit office hours, the library, or the writing center (especially if your writing center takes appointments—they fill up quickly at the end of the semester!). The more you fill in specific dates and smaller goals, the more likely you will be to complete them. Even if you miss a day that you set aside to write four hundred words, it’s easier to make that up than saying you’ll write an entire draft over a weekend and not getting much done.

Another useful strategy is assembling a checklist, as you put together all the pieces from your research, citations, key quotes, data, and different sections. This allows you to track what you have done and what you still need to accomplish. You might review your assignment’s requirements and list them out so you know when you’ve hit the things like required sources or minimum length. It also helps remind you towards the end to review things like your works cited and any other key grammar and style issues you might want to revisit.

You’re much closer to completing everything than you think. You have all the research, you have all the pieces, and you have a good foundation. You’ve developed a level of understanding of the many sources you have gathered, along with the writing projects you have written. Time to put it all together and join the conversation.

Key Takeaways

- Your research essay adds to the conversation surrounding your topic.

- Begin drafting your essay and trust that your ideas will continue to develop and evolve.

- As you assemble your essay, rely on what works for you, whether that is outlining, mindmapping, checklists, or anything else.

- You have come far. The end is in sight.

Clemson Libaries. (2016). “Joining the (Scholarly) Conversation.” YouTube . https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=79WmzNQvAZY

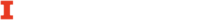

Fosslien, L. Remember how much progress you’ve made [Image].

Graff, G. & Birkenstein, C. (2017). They Say, I Say: The Moves that Matter in Academic Writing . W. W. Norton and Co.

Guptill, A. (2016). Constructing the Thesis and Argument—From the Ground Up : Writing in College . Open SUNY Textbooks.

Harris, Joseph. Rewriting: How to Do Things with Texts . Second Edition. Utah State University Press, 2017.

Writing for Inquiry and Research Copyright © 2023 by Jeffrey Kessler is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Writing for Inquiry and Research

Jeffrey Kessler, University of Illinois Chicago

Mark Bennett, University of Illinois Chicago

Sarah Primeau, University of Illinois Chicago

Charitianne Williams, University of Illinois Chicago

Virginia Costello, University of Illinois Chicago

Annie R. Armstrong, University of Illinois Chicago

Copyright Year: 2023

ISBN 13: 9781946011213

Publisher: University of Illinois Library - Urbana

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Learn more about reviews.

Reviewed by Angelica Rivera, Director, Northeastern Illinois University on 4/16/24

This book consists of a Preface, Introduction, Chapters I thru Chapter IV. and it also has an Appendix I to Appendix III. Chapter I covers the Annotated Bibliography, Chapter II covers the Proposal, Chapter III covers the Literature Review and... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 5 see less

This book consists of a Preface, Introduction, Chapters I thru Chapter IV. and it also has an Appendix I to Appendix III. Chapter I covers the Annotated Bibliography, Chapter II covers the Proposal, Chapter III covers the Literature Review and Chapter IV covers the Research Essay. Each section is broken down into smaller sections to break down each topic. The book is written by 3 different authors who are experts in their field and who write about different writing genres. The authors are interdisciplinary in their approach which means students in various disciplines can use the manual to begin their inquiry process and continue with their research process. This book also has short videos that provide explanations, and references after every chapter to provide additional learning resources. Appendix I covers Reading Strategies, Appendix II covers Writing Strategies and Appendix III covers Research Strategies. Appendix I and Appendix II also have additional resources for reading and writing strategies. This book will help most first year students who are transitioning from high school to college.

Content Accuracy rating: 5

This book is accessible for first year students who are in English, Composition or First year experience courses. However, the authors note that there are some limits to the topics addressed as the text does not cover research methods, databases, plagiarism and emerging writing technologies. The authors believe that writing is a human based process regardless of the tools and technologies that one uses when writing.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 5

This book is well researched and will survive the test of time as it is accessible and will serve as a reference tool for a student who is looking to develop their writing question and develop their research approach.

Clarity rating: 5

This book is well researched, well organized and well written.

Consistency rating: 5

There was consistency throughout the text as all of the authors had experience with working with first year students and/or with the writing process.

Modularity rating: 5

The first 3 chapters can be assigned in any order but the fourth chapter should be the 4th step as that part consists of writing the actual research essay. This book is not meant to be used by itself and thus provides additional bibliographic sources and topics to further develop one’s knowledge of the writing process.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 5

This book is written in the logical process of developing a research question and then conducting the research. An instructor can easily assign these chapters in chronological order and it will help the student to brainstorm to create their question and then follow the steps to conduct their research.

Interface rating: 5

There were no issues with the books interface.

Grammatical Errors rating: 5

I found this manuscript to be well written and it contained no visible grammatical errors.

Cultural Relevance rating: 5

I found this book to be neutral and accessible to all students irrespective of their various backgrounds.

I give this book 5 stars because it helps students and instructors break down the research process into smaller steps which can be completed in a semester-long course in research writing.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Annotated Bibliography

- Chapter 2: Proposal

- Chapter 3: Literature Review

- Chapter 4: Research Essay

- Appendix I: Writing Strategies

- Appendix II: Reading Strategies

- Appendix III: Research Strategies

Ancillary Material

About the book.

Writing for Inquiry and Research guides students through the composition process of writing a research paper. The book divides this process into four chapters that each focus on a genre connected to research writing: the annotated bibliography, proposal, literature review, and research essay. Each chapter provides significant guidance with reading, writing, and research strategies, along with significant examples and links to external resources. This book serves to help students and instructors with a writing-project-based approach, transforming the research process into an accessible series of smaller, more attainable steps for a semester-long course in research writing. Additional resources throughout the book, as well as in three appendices, allow for students and instructors to explore the many facets of the writing process together.

About the Contributors

Jeffrey C. Kessler is a Senior Lecturer at the University of Illinois Chicago. His research and teaching interrogate the intersections of writing, fiction, and critical university studies. He has published about the works of Oscar Wilde, Henry James, Vernon Lee, and Walter Pater. He earned his PhD from Indiana University.

Mark Bennett has served as director of the University of Illinois Chicago’s (UIC) First-Year Writing Program since 2012. He earned his PhD in English from UIC in 2013. His primary research interests are in composition studies and rhetoric, with a focus on writing program administration, course placement, outcomes assessment, international student education, and AI writing.

Sarah Primeau serves as the associate director of the First-Year Writing Program and teaches first-year writing classes at University of Illinois Chicago. Sarah has presented her work at the Conference on College Composition and Communication, the Council of Writing Program Administrators Conference, and the Cultural Rhetorics Conference. She holds a PhD in Rhetoric and Composition from Wayne State University, where she focused on composition pedagogy, cultural rhetorics, writing assessment, and writing program administration.

Charitianne Williams is a Senior Lecturer at the University of Illinois Chicago focused on teaching first-year composition and writing center studies. When she’s not teaching or thinking about teaching, she’s thinking about writing.

For more than twenty years, Virginia Costello has been teaching a variety of English composition, literature, and gender studies courses. She received her Ph.D. from Stony Brook University in 2010 and is presently Senior Lecturer in the Department of English at University of Illinois Chicago. Early in her career, she studied anarcho-catholicism through the work of Dorothy Day and The Catholic Worker Movement. She completed research at the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam and has published articles on T.S. Eliot, Emma Goldman, and Bernard Shaw. More recently, she presented her work at the Modern Studies Association conference (Portland, OR, 2022), Conference on College Composition and Communication (Chicago, Il, 2023) and Comparative and Continental Philosophy Circle (Tallinn, Estonia, 2022 and Bogotá, Columbia, 2023). Her research interests include prison reform/abolition, archē in anarchism, and Zen Buddhism.

Annie Armstrong has been a reference and instruction librarian at the Richard J. Daley Library at the University of Illinois Chicago since 2000 and has served as the Coordinator of Teaching & Learning Services since 2007. She serves as the library’s liaison to the College of Education and the Department of Psychology. Her research focuses on enhancing and streamlining the research experience of academic library users through in-person and online information literacy instruction.

Contribute to this Page

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

13.10: Student Inquiry Essay Examples

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 250495

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

COMMUNITY DESTRUCTION IN NORTH DAKOTA OIL BOOMTOWNS Katharine Berry

Jonnie Cassens is a truck driver who hoped that her move to a North Dakota oil boomtown would help her recover from her previous life in California. In the documentary “Running on Fumes in North Dakota,” she explains how the lifestyle emerging from North Dakota’s rapid oil boom isn’t as glamorous as it is often portrayed; in fact, it is a dirty and unpleasant life. Jonnie’s move from California has left her isolated and lonely with no one to turn to for support or companionship. She expresses her longing for a female friend to “gossip with” or someone she can “get a pedicure with,” but the oil boom has created a society dominated by men and a fractured community (Christenson). Jonnie may be physically alone, but she is not alone in her feeling that the oil boom has resulted in isolation and loneliness. Life-long residents and brand new residents of boomtowns fear the crime, prostitution, and influx of drugs that oil has drawn to North Dakota, and workers often face brutal conditions (Stewart). The unreliable and temporary nature of the North Dakota oil boom has disrupted the existing communities in this region and created deep divisions, preventing new communities from forming. Ultimately, the oil boom undermines community in all forms.

The cohesive rural communities that existed near oil reserves in North Dakota have disintegrated and been destroyed by the nature of the oil boom in the region (Brown). The rapid population flood has created problems of supply and demand in many aspects, especially in relation to housing. There is a great need for housing in the oil boomtowns but little availability, which drives up rent to prices approaching those in urban San Francisco (Warren). These extreme rent increases have made it difficult for many long-time residents to continue to afford their homes and many families are forced to find new housing outside of the region (Stewart). In New Town, North Dakota, a large trailer park, Prairie Winds, which has been home to several Native American tribes for decades, epitomizes this problem. The trailer parks’ new owner raised rents and evicted the long-term residents in order to provide housing for oil workers (Mufson). The original residents were left without roofs over their heads, and unfortunately this type of community destruction is not uncommon. As the oil boom drives housing prices up, families and loved ones are split up. Due to the limited availability of housing in the region, many people leave the area completely. These drastic rent increases have not only taken residents’ housing but their sense of home as well. To make matters worse, the history of oil booms in the region—which features promises of great success followed by sudden failures that leave the state in debt—has left many people skeptical, including construction developers. Since the construction industry anticipates that the region’s oil supply will eventually run out, no new housing is being built to ameliorate the housing crisis. Therefore, the high demand for housing will continue and long-term residents will be driven further from their communities.

Additionally, among residents who try to take advantage of the conditions the boom has created, there is a general consensus that the profit is not worth the trouble (Mufson). Some residents have leased out their land and minerals in exchange for a profit from the oil companies; however, the oil companies have caused physical destruction to residents’ property, leaving them disappointed and angry (Stone). In an interview with a North Dakota native published by The Washington Post , Donnie Nelson reflects on the two oil rigs on his property: “‘I don’t like what it’s done for our communities and lifestyle,’ he said. ‘We had a good life, and now it’s gone forever, or at least for my lifetime’” (Mufsan). He also reports that he would “‘give it all back for the trouble it’s been’” (Mufsan). Bert Hauge, another long-time resident, has large trenches on his property and cows with serious health problems as a result of the boom (Stone). These residents are left disapproving and discontented with the oil boom. North Dakotans remain skeptical that the promises of twenty years of success from this boom will become a reality, and instead believe that this boom will follow the limited course of previous booms (Lindholm). This bitterness has turned existing communities into a group of isolated individuals. No matter what their situation, all long-time North Dakotans share one commonality: they miss the time, before the oil boom, when communities “didn’t lock their doors and knew all their neighbors” (Mufson). While long-term residents in North Dakota have felt their communities disintegrate, employers in the oil industry have simultaneously prevented new communities from forming. This has resulted in deep divisions between employers and employees and further divisions among employees themselves. The “suits” (as the oil industry employers are called) have dehumanized workers and created an animal kingdom of men. They have mistreated men by implementing long hours and challenging and dirty work (Gale). Employees of the oil industry are on a schedule of approximately twelve-hour workdays for two weeks straight followed by two weeks of no work, but there is some degree of scheduling uncertainty, and sudden decisions often change schedules at the last minute (Chaudhry). These conditions create the sense of a temporary and easily replaceable environment, implying that the employees are inferior to the “suits.” With uncaring employers, there is a certain degree of animosity that allows workers to be deindividualized and take on the role of “rough and tumble oil worker” (Gale). Most workers are away from their homes and families and remain free of ties to any community in the region; occasionally workers act without being held accountable. This misbehavior has resulted in rising crime and drug use, problems that continue to grow (Healy).

There might be potential for workers to bond over their dehumanization, loneliness and desire for success, but because of the limited resources in the region, workers must compete, making the formation of community impossible. The housing scarcity has created massive competition between workers over housing (Chaudhry). Temporary man-camps of workers are now abundant, along with RV neighborhoods and thousands of vehicles that have been transformed into homes (Sulzberger). This competition is a free-for-all, and men who cannot find anything substantial have resorted to anything that will be sufficient for a temporary residence. With the harsh winters, some workers are finding it difficult to even stay alive. The inflation in the region also makes eating at restaurants practically impossible (Chaudhry). In a society with so many workers in the same situation, new communities could practically fall into place, but these workers face such a range of harsh conditions and obtaining basic requirements like housing and food take precedence over forming new communities.

The undermining of community caused by the oil industry in North Dakota isn’t the state or nation’s primary concern, and it is obvious that the economic benefits resulting from the boom are overwhelming. This oil boom could bring energy independence to the United States, which some might argue is sufficient reason to overlook community destruction. However, the oil boom has also brought health risks and environmental disturbances. Do the economic benefits outweigh the environmental, health and community drawbacks of oil boomtowns? Workers begin to wonder if leaving their families and homes for an uncertain amount of time, facing hard and lonely conditions, and performing dangerous work is really worth the extra income they will make. Others may wonder if the extreme yet temporary success of the oil industry in the region should be unthinkingly prioritized, especially given the destruction to the family land of native North Dakotans.

Is the temporary success of these modern boomtowns worth the potential long-term consequences they bring? As long as the boom benefits the nation as a whole, it is unlikely that there will be any changes to the industry, which leaves the residents of these North Dakota boomtowns more lonely and isolated than ever with no definite end in sight. This leaves residents like Jonnie Cassens in her trailer, which has no running water or toilet—and instead of confiding and bonding with a friend, the only relationship she has is with her dog.

Works Cited

Brown, Chip. “North Dakota Went Boom.” The New York Times. 31 Jan. 2013. Web. 29 Mar. 2014.

Chaudhry, Mat. Northern Utopia: Rebirth of American Dream: North Dakota Oil Employment. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2013. Kindle.

Christenson, James, Eliot Popko, Jonah Sargent, and Lewis Wilcox. “Running on Fumes in North Dakota.” The New York Times. 13 Jan 2014. Web. 13 Apr 2014. Video.

Cohen, Sharon. “Trying to Combat Growing Drug Trade in Oil Patch.” The Washington Post. 14 Apr 2014. Web. 24 Apr 2014.

Sweet Crude Man Camp. Dir. Gale, Isaac. Prod. Alec Soth. From: Life Inside an Oil Boom. The New York Times. 8 Feb 2013. Web. 13 Apr 2014. Documentary.

Greenwald, Judy. “Rail Risks Expand As Oil Shipments Boom.” Business Insurance 48.5 (2014): 0013. Business Source Complete . Web. 31 Mar. 2014.

Healy, Jack. “As Oil Floods Plains Towns, Crime Pours In.” The New York Times. 30 Nov 2013. Web. 13 Apr 2014.

Lindholm, Meg. “Flock to North Dakota Oil Town Leads to Housing Crisis.” All Things Considered. National Public Radio. 28 May 2010. Web. 6 Apr 2014. Transcript.

Mufson, Steven. “In North Dakota, The Gritty Side of an Oil Boom.”

The Washington Post. 18 July 2012. Web. 24 Apr 2014.

Oldham, Jennifer. “North Dakota Oil Boom Brings Blight With Growth as Cost Soar.” Bloomberg. 24 Jan. 2012. Web. 29 Mar. 2014.

Schultz, E J. “Williston: The Town the Recession Forgot.” Advertising Age, 82.39, 31 Oct. 2011: 1. Web. 5 April 2014.

Stewart, Dan. “North Dakota: Trouble in Boomtown.” The Week. 19 Sept. 2013. Web. 29 Mar 2014.

Stone, Andrea. “Oil Boom Creates Millionaires and Animosity in North Dakota.” USA Today. N.d. Web. 24 Apr 2014.

Sulzberger, A.G. “Oil Rigs Bring Camps of Men to the Prairie”. The New York Times. 25 Nov 2011. Web. 28 Mar 2014.

Warren, Michael. “Highest Rents Found in Oil Boom Towns of North Dakota.” The Weekly Standard. 14 Feb 2014. Web. 28 Mar 2014.

Instructor’s Memo Kate’s essay is a testament to how individual stories can make large-scale geopolitical debates feel real and emotionally relevant. Over the past year, the news cycle has featured stories of the Keystone XL pipeline bill, global warming, and peak oil, but Kate leaves us with the image of a woman living alone in a trailer near the North Dakota oil fields. As Kate notes, this woman is surviving without running water or a toilet, her only significant relationship with her dog. Reading Kate’s paper, I am reminded that arguments—even critical and scholarly ones—are sometimes more effective when conveyed through images as opposed to direct statements. Kate did a tremendous amount of research for this project. Her sources range from newspaper articles to videos to radio transcripts to full-length books. This research allowed her to situate her argument within the larger historical context of boomtowns while also quoting contemporary residents of North Dakota oil communities. Kate’s research also allowed her to consider her argument from multiple perspectives: if existing communities in North Dakota are undermined by the sudden economic influx of an oil boom, then the people who arrive to work in the oil fields also report feeling dislocated and lonely. In this sense, Kate’s writing helps us understand how there are always multiple perspectives on disaster. — Sarah Dimick Writer’s Memo The skills I learned in English 100 have helped me to become a much better writer because I learned the basics of how to compose a good paper, not just how to write to meet the requirements for a specific paper. When told that we would write the last paper of the semester about a contested place, I had no idea what I would write about. In class, we read several pieces from various sources that gave us an idea of what a contested place could look like. I asked my parents for some examples and one of them mentioned hydrolytic fracking in North Dakota. I didn’t know much about the topic but I liked that it was a contested place in the U.S. Determining a topic to write about was one of the hardest parts of the paper for me, but I took the idea and looked at a specific aspect within the place — the communities. I knew very little about what was happening in the oil boomtowns in North Dakota, and even less about the communities within them. In class, we learned how to: gather information and utilize library resources, integrate quotations, write a thesis, and structure an essay and the paragraphs in it; all of which made writing the paper less intimidating. I met with my teacher periodically throughout the writing process, which in turn helped me stay on top of the paper and do the necessary work to write a great paper. I have never enjoyed writing and have instead dreaded it, generally finding it to be intimidating and overwhelming. However, after learning skills to write a good paper, meeting consistently with my teacher, and working at a steady pace, I began to enjoy writing and I eventually produced a paper I am truly proud of. Different from many of the papers I had written before, I also enjoyed researching about the community destruction in North Dakota oil boomtowns. I found the topic fascinating, so much so that I wanted to share what I had learned with others, and get involved in some way to help address the problems in the oil boomtowns. The most challenging part of the paper was identifying what I wanted the paper to be about, and narrowing a broad idea into a specific focus that I could form into a thesis statement. I identified the main points I wanted to use, compared them and looked at what they had in common; then, my teacher helped me narrow down and look at the big picture and I determined the specific focus of the paper. After developing a thesis, the rest of the paper was easy. I realized that sometimes the thesis statement comes later on in the process, and it may change several times before it is right. The process of writing this paper has turned me into a much better writer, and I continue to use the skills I learned in English 100 for all my papers. — Katharine Berry Student Writing Award: Critical/Analytical Essay This essay was previously published in the 9th edition of CCC.

BACK TO TOP

LICENSE Community Destruction in North Dakota Oil Boomtowns by Katharine Berry is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted. UNDERSTANDING MASS INCARCERATION OF AFRICAN AMERICAN WOMEN Ruthie Sherman

You open your eyes to concrete walls, three roommates, a couple square feet of space, and a toilet about a foot from your bed. You sit up, only to slam your head on the body of your bunkmate, resulting in a large red mark. You slowly stand up because you really have to go to the bathroom and 3:45 a.m. is the only time the guards are too tired to stare at you while you go. This hypothetical situation might seem terrifying, but it is like the common experience of millions of prisoners every day in the U.S. While most Americans are unaware of and desensitized from the consequences of being in prison, incarcerated Americans have to deal with overcrowding, lack of privacy, and isolation on a daily basis. How did this become the norm? How have so many Americans become so unjustifiably desensitized? How is this situation affecting different groups of people in the United States? To begin with, how did we decide that the punishment for crime should be incarceration?

Today, the concept of incarceration is normal. Most people would not think twice when a person is sentenced to time in jail or prison. However, this was not always the case. In The Historical Origin of the Prison System in America, Harry Elmer Barnes chronicles the evolution of criminal justice in the United States. Starting with the Colonial period, Barnes attributes the origin of the modern penal system to two institutions: jails and prisons, which he considers one institution, and workhouses. During the Colonial period, jails and prisons were locations meant only to hold prisoners until a punishment was decided after their trial, creating the practice of placing criminals in separate spaces from the majority of society. Workhouses were designed to repress people of lower class, especially poor people, and were not meant to punish criminals. However, the practice of forcing labor on lower class citizens originated with workhouses. For a long time, these two institutions existed in isolation from each other, containing the group they were constructed to manage.

American Quakers are credited with combining the practices of each institution. According to Barnes, “they originated both the idea of imprisonment as the typical mode of punishing crime, and the doctrine that this imprisonment should not be in idleness but at hard labor” (36). Without knowing it, Quakers transformed the perception and implementation of prison systems in the United States. They took the premise of prisons, isolation of criminals as punishment, and the premise of workhouses, making active use of unproductive members of society, to produce the modern practices of imprisonment and incarceration (Barnes, 36). However, the Quakers had no means of predicting how these principles and practices would become the platform for a dehumanized perspective on criminals.

When prisons were established on the belief that criminals should be isolated based on deviance, the perception of criminality and punishment shifted. Instead of a societal responsibility, there was an invisible solution. Criminals were put out of sight, barricading issues of criminal justice and punishment from the daily concerns of the majority of Americans. This enabled a dependency on criminal justice policies that absolved the larger society of responsibility or of being conscious of actively pursuing social reform for people who had committed crimes. As this dependency grew and became more institutionalized, criminals became viewed as mere shells strictly defined by crime instead of complex human beings with backgrounds and identities that could contextualize their criminal activity (Meares, 8).

According to Christina Meares, some of the invisible dynamics that could contextualize the experiences of incarcerated individuals include, “homelessness, unemployment, drug addiction, illiteracy and dependency on welfare.” She continues, “These are only a few of the problems that disappear from public view when the human beings contending with them are relegated to cages” (8). When people perceive criminals, not only are such dynamics generally unacknowledged, but the multifaceted ways they impact each person depending on their identities are ignored as well. As a consequence, society’s dependence on prisons to reform members of society has ignored the dynamics that were enabling and reinforcing crime among certain groups of people (Meares, 8). An unfair practice of criminal justice was established. Prisons were expected to change and reform criminals, even while society remained silent about the contexts maintaining and reinforcing criminal behavior. The silence surrounding these dynamics, which allowed individuals to be strictly defined by their crime, along with the concentration of criminals into prisons became the foundation for a dehumanized perception of the incarcerated population. And this perception of criminals fed the rise of mass incarceration, the extreme rates of imprisonment, and the manifestation of a dehumanized and racialized perception of criminals that ignores the contexts of institutional issues of poverty and race (Stevenson, 15).

While the perception of criminals has evolved since the Colonial period, mass incarceration emerged relatively recently. During the 1980s, the dynamics that society surrounded with silence, most noticeably drug use, became the defining factors that would directly lead to the rise in incarceration. Although crime was decreasing at the beginning of that decade, President Reagan started his “War on Drugs” against the use of crack cocaine (Alexander, 3). In the introduction to her book The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, Michelle Alexander describes how this war was not necessarily founded on an actual widespread drug problem. She writes, “[T]here is no truth to the notion that the War on Drugs was launched in response to crack cocaine. President Ronald Reagan officially announced the current drug war in 1982, before crack became an issue in the media or a crisis in poor black neighborhoods” (3).

Subsequently, the Reagan administration even hired staff to produce a media campaign demonizing crack cocaine, which succeeded almost immediately in gaining support from both the public and the government. Unsurprisingly, many of the images used in this campaign displayed men of color wearing stereotypical inner city clothing, implying they were the villains of the crack cocaine story. Since the public had been conditioned for nearly the entire history of the United States to depend on prisons to act as social reformers, Reagan’s so-called War on Drugs could then easily and swiftly mass incarcerate the poor people of color in the United States (Alexander, 3).

The current debate surrounding mass incarceration is dominated by discussions of how this issue impacts men of color or poor white men. But it is important to see that American patriarchal society has empowered another destructive force within the emergence of mass incarceration, namely, ignoring how this phenomenon has affected women. In Bryan Stevenson’s book Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption , the twelfth chapter, entitled “Mother, Mother,” grapples with the mass incarceration of women in the United States. Stevenson writes, “In the United States, the number of women sent to prison increased 646 percent between 1980 and 2010, a rate 1.5 times higher than the rate of men” (235-36). Stevenson credits two key components in the high rate for the mass incarceration of women: the criminalization of infant mortality and the enactment of the “Three Strikes” law, which increased sentences to life in prison for a crime when an offender had committed two or more serious crimes in the past (236). While the attitude towards criminals generally is defined purely by their crime, the attitude toward gender for female prisoners also shows that these prisoners are being subjected to strict and decontextualized definitions using the crime of the prisoner. Rather than just being criminals, drug users, thieves, or murderers, the attitude is that women prisoners are also sluts, horrible mothers, abusive mothers, and undeserving of help from society.