Regionalization vs globalization: what is the future direction of trade?

Analysts and commentators predict a wave of deglobalization in the wake of disasters like the pandemic and the Suez Canal blockage. Image: REUTERS.

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Stefan Legge

Piotr lukaszuk.

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Trade and Investment is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:.

Listen to the article

- Destabilizing world events, including COVID-19 and the Suez Canal blockage, have exposed international trade's vulnerabilities.

- Several prominent analysts and commentators are predicting trade will become less globalized and more regional.

- We examined merchandise trade data between 1815-2021 to test this hypothesis.

International trade is a key source of economic prosperity. That is why policymakers, economists and business leaders alike are concerned by recent developments. The COVID-19 crisis, as well as the Suez Canal blockage, add to a series of troubling events: rising protectionism and the China-US trade war to name just two. These developments have contributed to new discussions about the shortening of supply chains and building up resilience.

Some analysts and commentators see a wave of deglobalization forging ahead. The Economist predicted on 24 January 2019: “The new world will work differently. Slowbalisation will lead to deeper links within regional blocs. Supply chains in North America, Europe and Asia are sourcing more from closer to home. In Asia and Europe most trade is already intra-regional, and the share has risen since 2011.” And in the Financial Times, Martin Wolf wrote on 10 December 2020: “The plausible future is not that international exchange is going to die. But it is likely to become more regional and more virtual.”

Are regionalization predictions backed up by the data?

Based on a careful analysis of merchandise trade data, we examined the extent to which data supports such projections. To do so, we established three indicators that reveal regionalization: the share of global trade between nations on the same continent; the share of global trade between nations featuring a common border; and the average trade-weighted geographic distance of global trade. All three signal a trend towards regionalization if they increased recently.

1. Trade data 1815-2014

First, we considered historical trade data provided by Michel Fouquin and Jules Hugot, which spans back to the year 1825 (Figure 1: Tests for Regionalization in Historical Trade Data, 1815-2014). We observed that about a fifth of global trade occurs between neighbouring countries, roughly 60% among countries on the same continent. And the trade-weighted average geographic distance in global trade is about 5,000km but fluctuates over time – with declines during major disruptions. For all three indicators, there is no evidence of regionalization in the years prior to 2014.

2. Trade data 1950-2019

These numbers provide a historical benchmark. But what does more recent data show? For this, we utilized the latest data provided by Keith Head and Thierry Mayer (Figure 2: Tests for Regionalization in Contemporary Trade Data, 1950-2019). Notice that the historical data covers a somewhat different set of countries compared to the contemporary data-set, which makes cross-data-set comparisons difficult and emphasizes within-data-set analyses.

Nevertheless, the contemporary trade data also provides no support for the regionalization hypothesis. The shares of global trade among neighbouring countries and those on the same continent is remarkably stable. And the average geographic distance that goods travel has increased in the past 20 years, especially because of China’s integration into the global economy. This rise compensated for the decrease in the 1990s that largely reflects the opening up of Eastern European countries.

3. Trade data 2016-2021

Why then do many commentators argue regionalization is happening? Thus far, we might conclude that you could see regionalization everywhere, except in the data. However, the latest data that captures the year 2020 is concerning. While this data is not yet available for all nations, we can consider import statistics from the EU. Patterns in Figure 3 (Tests for Regionalization in Latest EU-28 Trade Data, 2016-2021) were remarkably stable until the COVID-19 crisis hit in February of 2020. Notably, the share of imports from countries on the same continent increased and the average geographic distance of imports fell significantly (this is not a Brexit effect as we look at the EU-28). Pandemic-related disruptions have clearly hit international supply chains.

What does the data reveal?

One may argue that any emerging patterns in regionalization statistics are suppressed by long-run existing trade flows. We thus repeat the analysis focusing on “new trade”, i.e. product level flows between countries that never traded such goods beforehand on a commercial level (we define it as minimum $1 million). Here, we find that the average trade-weighted distance has continuously fallen over the past five years and in 2019 reached its lowest level since the financial crisis of 2008. Also, the share of new trade between bordering countries saw a significant uptick in 2019 to 18% from the 9-10% seen over the past two decades. The jury is still out on whether these recent indications of regionalization are the first signs of a systematic shift.

The COVID-19 economic crisis has put further strain on globalization. It remains to be seen if companies and policymakers permanently change their behaviour after the recovery. Growth in merchandise trade had slowed down to a crawl prior to the pandemic, according to data from the CPB World Trade Monitor. This slowdown in global trade growth appears to conflict with a contemporaneous trend: the number of trade agreements has surged in recent years.

The Global Alliance for Trade Facilitation is a collaboration of international organisations, governments and businesses led by the Center for International Private Enterprise , the International Chamber of Commerce and the World Economic Forum , in cooperation with Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit .

It aims to help governments in developing and least developed countries implement the World Trade Organization’s Trade Facilitation Agreement by bringing together governments and businesses to identify opportunities to address delays and unnecessary red-tape at borders.

For example, in Colombia, the Alliance worked with the National Food and Drug Surveillance Institute and business to introduce a risk management system that can facilitate trade while protecting public health, cutting the average rate of physical inspections of food and beverages by 30% and delivering $8.8 million in savings for importers in the first 18 months of operation.

According to the World Trade Organization, the cumulative number of regional trade agreements in force increased from less than 100 in the year 2000 to almost 500 today. Most of world trade now takes place between country pairs that have established a reciprocal trade agreement. Recently enacted trade agreements by the EU as well as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership suggest this number to increase further. Such agreements often facilitate trade between nations located in different geographic regions. Yet, the average geographic distance of free trade agreement partners has been remarkably stable at around 4,800km since the year 2000.

While the global financial crisis permanently reduced the speed of globalization, the world economy went into the COVID-19 crisis already with largely stagnant global trade volumes. The pattern of regionalization which now appears in the latest trade statistics enriches the debate and offers researchers new metrics to quantify the scope of regionalization.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Trade and Investment .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

Global trade could more than double in 2024. Here’s why

Andrea Willige

May 14, 2024

Geopolitical rivalries are costly for global businesses. Here’s why – and what's at stake

Spencer Feingold

May 13, 2024

4 key trends driving private market impact funds: One CEO explains

Michael Eisenberg and Zlatan Plakalo

May 6, 2024

Why we must balance cooperation and competitiveness in cleantech

Nils Aldag and Christopher Frey

May 1, 2024

Policy tools for better labour outcomes

Maria Mexi and Mekhla Jha

April 30, 2024

A new economic partnership is emerging between Africa and the Gulf states

Chido Munyati

April 28, 2024

Does Regionalism Challenge Globalization or Build Upon It?

As the world witnesses the globe shrinking with the advancement of technology and the increasing interdependence states have upon one another, it is hard not to detect the numerous weaknesses and unaddressed atrocities that lay within the system of ‘globalized’ international relations. This paper will aim to explain that in response to the many faults the system of ‘globalization’ contains, a new form of regionalism has arisen in the world to address what global multilateralism can not. Before even expanding on such a topic, the modern term ‘globalization’ and its post-World War II origins must be defined and looked at to see why such a liberal-based system was flawed from its ‘birth.’ Then, ‘regionalism’ will briefly be defined in context so as to give an idea of the contrasting ideals each term embodies. Later, through the use of pragmatic examples such as continental governing bodies, regional trade agreements, and cultural movements, it will be proven that as a result of globalization, regionalism is rising in political, economic, and cultural spheres. To offer perspective, a counterargument will be made surrounding how regionalism might be taking a step backward in achieving global cohesiveness. However, it will be concluded that regionalism is in fact a building block of achieving a successful ‘globalized world’ and thus, must be embraced rather than avoided.

When speaking of ‘globalization,’ it is rare two people will mean the same thing as there exists a consistent disagreement regarding its sources, consequences, and whether the term even exists. [1] The ‘globalization’ that will be discussed is the version that had arisen following the Second World War as a result of the American world order imposed by the United States. The creation of the International Monetary Fund, the World Trade Organization, and the United Nations all represented the vision of a someday borderless world or rather a ‘globalized’ world. [2] Today, globalization implies the consistent growth of a world market, allows the increasing penetration of national economies, and essentially intensively ‘transnationalizes’ economic, financial, environmental, and political problems whether a state likes it or not. [3]

Political scientist Toshiro Tanaka criticizes that the basic problem of globalization is its selectiveness. “Exclusion is inherent in the process [of globalization], and the benefits are evenly balanced by misery, conflict, and violence.” [4] When it comes to the sources of globalization, they are detected in the capitalist mode of production, technological development, and/or the deregulation of financial markets. [5] To summarize, the United States in the post-war era catalyzed the version of globalization which countries recognize today as a weakly-regulated world system that favors the few and tortures the majority with transnational problems.

Regionalism, like globalization, can also be seen as somewhat vague in its meaning. First off, a region is defined not just as a geographical unit but also a social system, organized cooperation in a certain field (security, economy, cultural), and/or an acting subject with a distinct identity. It should be explained that there is a sharp contrast between “old regionalism” which existed during the Cold War period and “new regionalism” which is seen arising in modern day. [6] Old regionalism revolved around countries siding with hegemonic powers, implementing protectionist policies, acting inward oriented and specific intentions, and holding the structural realist approach of concerning itself with the actions of states. [7] NATO and the Warsaw Pact are both excellent examples of old regionalism as they were forced regional agreements as a result of the bipolar system their creators resided in.

New regionalism on the other hand, has taken shape out of the multi-polar world order and is a more spontaneous process from within the regions, where constituent states now experience the need for cooperation in order to tackle new global challenges. [8] New regionalism is a more comprehensive and multidimensional process which not only includes trade and economic development but also environmental, social, and security issues. Not to mention, it forms part of a structural transformation in which non-state actors are also active and operating at several levels of the global system. Modern regionalism goes far beyond free trade and addresses multiple concerns as the world struggles to adapt the transforming and globalizing world. [9]

In the economic sphere, regionalism has proven to be extremely effective in helping to secure markets and providing economic strength through the creation of Regional Trade Agreements (RTAs). In globalizing institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Trade Organization, agreements binding governments to liberalization of markets restrict their ability to pursue macroeconomic policies. [10] However, under RTAs, economic policies remain more stable and consistent since they cannot be violated by a participant country with provoking some kind of sanctions from other members. [11] An excellent example of this is the North American Free Trade Agreement’s (NAFTA) stabilization and increase of Mexico’s political and economic policies. [12]

In the globalizing market system, huge amounts of capital can be disinvested and reinvested in a relatively short amount of time. Thus, states lose control over exchanges and economic development and as a result holds a reduced its role in its own economy. Regional Trade Agreements help nations gradually work towards global free trade through allowing countries to increase the level of competition slowly and give domestic industries time to adjust. [13] The increasing membership of less economically developed countries within the European Union, Southern Common Market (MERCOSUR), and Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) is testament to the economic stability offered by regional economic organizations. [14] ASEAN countries have already begun vying for RTAs with China in hopes of rebuilding economic stability and renewing growth that was shaken by the economic crisis of 1997. [15] In the end, entering regional pacts with hegemonic powers can be easily seen to be more beneficial for smaller countries than subjecting themselves to the hegemonic-controlled free market.

A major weakness globalization embodies, is its inability to effectively address transnational security and political issues. [16] As previously stated, globalization is selective and while some gain profit from the implementation of neo-liberalist principles, others are found to suffer at their hands. Hence regional organizations have been created to address more local problems and to prevent foreign intervention. [17] For example, Organization of African Unity was formed to prevent external manipulation which globalization so freely allows and reacted to eleven conflicts on the continent. Not to mention the fact that the African Union was formed out of the necessity to address what multilateral, globalizing efforts could not after the Rwandan Genocide and the crisis in Somalia. The African Union’s regional success is testified by the reduced number of interstate wars and its quick response to peace negotiations concerning the genocide in Darfur, Sudan. [18]

Besides security, globalization has failed in ensuring that multilateral political legislation be implemented throughout the world. For example, the Kyoto Protocol as well as the Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen implemented very few binding regulations in a world where globalization has made pollution transnational. The failure for a state to have control over its citizens’ health holds a dangerous effect for its legitimacy as government and thus must effectively collaborate with other actors in the world to ensure that safety. This is seen in the European Union’s carbon trade market where, despite failures seen at the Copenhagen Conference and the Kyoto Protocol, pollution regulations have been put in place. The fact that these regional management programs exist and persist, in spite of rivalries, shows the seen imperative need by states for cooperation. [19]

As a result of this high rise in globalization, states have lost control over the external relations of their societies when they are exposed to mutual cultural influences. Political Scientist Niels Lange argues that cultural influences now appear in a co-modified way. ‘Patterns of consumption are converging throughout the world, languages become “anglicized,” and the youth consumes similar styles of music and pop culture.’ [20] This spread of ‘imagined communities’ where standardization exists through language, education, and even values has faced opposition due to the culturally diminishing effect it has. Both interstate and sub-state regionalism has occurred in response to the spread of such ‘cultural globalization’ in order to preserve distinct cultural attributes.

Regionalism has responded to cultural globalization through an increase in cultural identity and the rise of regionalist parties. A perfect example is the rise of Parti Quebecois Bloc and the general cultural identity the region of Quebec holds. Being the sole French speaking region in all of mainland North America, Quebec has retained a stronghold on ensuring its Francophone tradition does not end. It remains the leader in the entire Western Hemisphere for culturally-related imports since it belongs to a country with a strong anglicized tradition and increasingly ‘globalized’ community. [21] On a much larger scale, it can be observed that cultural regionalization is occurring in European-based North America, Europe, Northeast Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Latin America. Hence it can be observed that cultural regionalism has resulted from a resistance to a global identity.

With the increasing sense of regionalism growing in the world to essentially make up for the weaknesses modern globalization has failed to address, the question remains if the world is moving away from global unity. Tanaka states that new regionalism should be defined as a world order concept. ‘Since one regionalization of the world holds repercussions over other regions of the world, it is thus shaping the way in which new world order is being organized.’ [22] Not to mention, that regionalism centers on the creation of regional identity as opposed to a more global identity. After all, one of the main focuses of the European Union at the moment is its focus in creating a European identity. Thus it could be argued that ‘Huntington’s clash of civilizations’ hypothesis could be plausible under these conditions of region versus region. In the end, regionalism can be seen as simply building up states and conflict up on a larger scale. [23]

However, the build up of regionalism is made only possible by the sheer width of the world that globalization encompasses and thus could not replace the system in which it exists. With multiple multilateral institutions holding regulations over regional bodies, it is very hard for globalization and international multilateral systems to be overturned. In addition, with the rise of interregionalism, or the pursuit of formalized intergovernmental relations with respect to relationships across distinct regions, the world is able to act cohesively on a larger scale. For example, the European Union has initiate formal interregional talks with East Asia countries, developed interregional accord with MERCOSUR, and has held Asia-Europe Meetings (ASEM). Henceforth, with the political and economic stability offered to countries by regionalism, future interregional relations can be presumed to be peaceful. [24]

In the face of weakly tamed globalizing world, it has been argued that states have responded through regionalizing in order to preserve economic, political, and cultural stability. It should be concluded that regionalist blocs have resulted mostly out of the current system’s inability to address ad hoc situations occurring in various fields throughout the world; not to mention, they have also resulted from the unpredictable future the globalizing world offers with its varying economics, political motivations, and cultural migrations. Although it could be argued that regionalism is simply placing the international system on a larger scale, the amount of stability and regulation that comes with regionalism is incomparable. Therefore, it has been properly argued that regionalism is in fact a building bloc of achieving global peace and cohesiveness through its more specified and regulative approach.

[1] Niels Lange, “Fragmentation vs. Integration? Regionalism in the Age of Globalization,” European Consortium for Political Research,

[2] Carlos J. Moreiro-Ganzalez, “Governing Globalisation: The answer of Regionalism,” European Commission,

[3] Toshiro Tanaka and Takashi Inoguchi, “Globalism and Regionalism,” United Nations University Press

[4] Toshiro Tanaka and Takashi Inoguchi, “Globalism and Regionalism,” United Nations University Press

[5] Niels Lange, “Fragmentation vs. Integration? Regionalism in the Age of Globalization,” European Consortium for Political Research,

[6] Toshiro Tanaka and Takashi Inoguchi, “Globalism and Regionalism,” United Nations University Press

[7] Toshiro Tanaka and Takashi Inoguchi, “Globalism and Regionalism,” United Nations University Press

[8] Toshiro Tanaka and Takashi Inoguchi, “Globalism and Regionalism,” United Nations University Press

[9] Toshiro Tanaka and Takashi Inoguchi, “Globalism and Regionalism,” United Nations University Press

[10] “Regionalism,” Center for International Development at Harvard University,

[11] “Regionalism,” Center for International Development at Harvard University,

[12] John S. Odell, ed. Negotiating Trade (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006),

[13] “Regionalism,” Center for International Development at Harvard University,

[14] Vinod K. Aggarwal and Edward A. Fogarty, “Between Regionalism and Globalization: European Union Interregional Trade Strategies,”

[15] “Regionalism,” Center for International Development at Harvard University,

[16] Carlos J. Moreiro-Ganzalez, “Governing Globalisation: The answer of Regionalism,” European Commission,

[17] Samuel M. Makinda and F. Wafula Okumu, The African Union (Abingdon: Routledge, 2008),

[18] Samuel M. Makinda and F. Wafula Okumu, The African Union (Abingdon: Routledge, 2008),

[19] Niels Lange, “Fragmentation vs. Integration? Regionalism in the Age of Globalization,” European Consortium for Political Research,

[20] Niels Lange, “Fragmentation vs. Integration? Regionalism in the Age of Globalization,” European Consortium for Political Research,

[21] Niels Lange, “Fragmentation vs. Integration? Regionalism in the Age of Globalization,” European Consortium for Political Research,

[22] Toshiro Tanaka and Takashi Inoguchi, “Globalism and Regionalism,” United Nations University Press

[23] Mark Webber and Michael Smith, Foreign Policy in a Transformed World (Harlow: Pearson Education, 2002),

[24] Vinod K. Aggarwal and Edward A. Fogarty, “Between Regionalism and Globalization: European Union Interregional Trade Strategies,”

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The Origins of Regionalism in the EU and ASEAN

- Is China Using the AIIB to Reinvent Asian Regionalism?

- ‘Keeping it Real’ or Keeping it Realist? Hip Hop in International Relations

- When It Comes to Global Governance, Should NGOs Be Inside or Outside the Tent?

- International Relations Theory Will Be Intersectional or It Will Be… Better

- “Fake It Till You Make It?” Post-Coloniality and Consumer Culture in Africa

Please Consider Donating

Before you download your free e-book, please consider donating to support open access publishing.

E-IR is an independent non-profit publisher run by an all volunteer team. Your donations allow us to invest in new open access titles and pay our bandwidth bills to ensure we keep our existing titles free to view. Any amount, in any currency, is appreciated. Many thanks!

Donations are voluntary and not required to download the e-book - your link to download is below.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Architecture

- History of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- History of Art

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- Political History

- Regional and National History

- Social and Cultural History

- Urban History

- Language Teaching and Learning

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- Language Evolution

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Browse content in Literature

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musicology and Music History

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cultural Studies

- Technology and Society

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Biochemistry

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Programming Languages

- Browse content in Computing

- Computer Games

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Maps and Map-making

- Environmental Science

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- Probability and Statistics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- History of Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Developmental Psychology

- Health Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Corporate Governance

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Browse content in Environment

- Climate Change

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Environmental Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- International Relations

- Latin American Politics

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Public Policy

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- US Politics

- Browse content in Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Sport and Leisure

- Reviews and Awards

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

5 Regionalization versus Globalization

- Published: November 2013

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Both global and regional economic linkages have strengthened substantially over the past quarter century. This chapter employs a dynamic factor model to analyze the implications of these linkages for the evolution of global and regional business cycles. The model allows us to assess the roles played by the global, regional, and country specific factors in explaining business cycles in a large sample of countries and regions over the period 1960-2010. The findings show that, since the mid-1980s, the importance of regional factors has increased markedly in explaining business cycles especially in regions that experienced a sharp growth in intra-regional trade and financial flows. By contrast, the relative importance of the global factor has declined over the same period. In short, the recent era of globalization has witnessed the emergence of regional business cycles.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- Google Scholar Indexing

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Globalization and Regionalization: Conceptual Issues and Reflections

Related Papers

Jeffrey Hart

Irah Kučerová

The end of the 20 th century has brought a number of both qualitative and quantitative changes in the functioning of the world economy. A new phenomenon is the process of the economic globalization implementing itself fully which has become the impulse for other developmental changes. The process of the economic globalization limiting the autonomy of national subjects completed the disintegration of the Westphalian system, when a state was not capable to control fully the activities of the economic subjects within its territory. But, the national states, especially in Europe, are responsible for the protection of public interests and for the supply of public goods. This dichotomy between the state power and the economic effectiveness leads to the current crisis of states, let us say crisis of the welfare states, when the strengthening competitive pressure of the liberalized world economy reduces social benefits , which the postwar generations were accustomed to. In Europe, this is especially reflected in a high degree of the institutional protection of the labour market and the pension systems that are entirely inconvenient nowadays. The process of globalization has been enabled by the institutional and political changes of the world economy in the 80's. These changes have led to the transformation of economic relationships , intensified thanks to the technological discoveries and their practical application. The gradual institutional standardization within the Uruguay Round of the GATT 1 increased the mobility of capital, and, in the same round of the negotiations, the liberalization of the international trade led to the growth of the international exchange. The fall of the Iron Curtain unified the bipolar, divided world into one economic area. Globalization has various definitions, yet, thanks to its multi-level character, it is necessary to render its most important aspects, at least. In any case, it is a process, in which the importance of the transnational and international companies within the economy of particular states is growing, and the shares of the direct foreign investments and import are going up. However, it is also a manifestation of an accelerated economic dependence of nations within the world system, which is mediated and amplified by the mass media and transport (Kottak: 1996). A logical consequence of this are changes in many aspects of the social existence of nations, states. Then, the economic globalization is a process, in which law, market and politics limit the autonomy of national subjects, because the development of economy and legislature also involves changes in politics. The economic globalization has thus contributed to the disintegration of the Westpha-lian system of international relations. For nearly 350 years, this system regulated the position of the state in foreign relations, when the state was controlling fully the activities of all

Michel Fouquin

EDITORIAL BOARD

Ramona Frunza

Rosana Pinotti

Economic Geography

Jonathan V Beaverstock

Dr. Hari Prasad Mishra

Globalization has become a familiar enough word, the meaning of which has been discussed by others before me during this conference. Let me nonetheless outline briefly what I understand by the term. I shall then go on to consider what has caused it. The bulk of my paper is devoted to discussing what we know, and what we do not know, about its consequences. I will conclude by considering what policy reactions seem to be called for.

Revocatus kashaga

Vincent Dietrich

Globalisation is what we make of it; why economic globalisation is optional and how post 2008 we are seeing a potential shift away from the hegemonic rhetoric and the beginnings of a post globalised world. Nation states have been the centre of political authority since the signing of the treaty of Westphalia in 1648 (Bowen, 2018; 2). Yet over the past 35 years the common discourse has become one of globalisation and the demise of the nation state, and its authority, especially in terms of the economy (Creveld, 2000; 5). For this reason and due to the relatively short length, this essay will focus on economic state authority, looking in particular at the power of Western states. During the late 1980s and early 1990s hyper-globalists such as Ohmae (1989) and Reich (1991) began to suggest that improvements in technology, especially in communication and transportation, were having damming effects on the power and the role nation states play in international politics (Hay, Lister, and Marsh, 2006;172-173). They further argued that labour, goods, and capital move across state boarders with ease, co-operations being able to move where it suits them best which makes the world seem borderless (Ohmae, 1996). However, this view soon came under fire from more sceptical voices, the likes of Hirst and Thompson (1999) suggesting that state power had not hugely changed; this view has since been repeated by several other theorists (see Hay, Lister, and Marsh, 2006; 174). This essay will position itself somewhere between these two arguments, suggesting that there has been an erosion of state authority-especially to large co-operations-but that this is not down to the material reality of technological advancements, faster transportation and better communication, but is instead down to its rhetorical construction. This essay will start by looking at the inaccuracies of the classic business school theory of globalisation; it will then move on to look at how globalisation theory has been constructed and how this has led to a transfer of state power to non-state actors.

Sapida Barmaki

RELATED PAPERS

Teknik Dergi

Çağlayan HIZAL

Cell Reports

Dae-Hyuk Kwon

amirmaziar niaei

Dr.Sanjeev Gour

Multimedia Tools and Applications

Ramesh Jain

Göttinger Miszellen. Beiträge zur ägyptologisch 185en Diskussion

Zeinab Mahros

Revue d'Épidémiologie et de Santé Publique

K. Meguenni

Phenomenon : Jurnal Pendidikan MIPA

Nur Khasanah

Katalin Szili

Clinical Infectious Diseases

Muhammad Haruna Ahmad

Sergio D Bergese

Calidad en la Educación

Jorge Baeza

Acta Horticulturae

Bénédicte Quilot-Turion

research memorandum

Henk Elffers

hjhjgf frgtg

Chizzy Rok0465

Journal of Mathematical Chemistry

Jaume Casademunt

"Pamiętnik Literacki"

Roman Krzywy

Computers & Graphics

Ergun Akleman

Social Science Research Network

maurizio del conte

Antifasciste e antifascisti. Storie, culture politiche e memorie dal fascismo alla Repubblica

Giovanni Brunetti

Parasitology Research

Damdinsuren Boldbaatar

2016 15th International Conference on Frontiers in Handwriting Recognition (ICFHR)

Daniel Prusa

Journal of British Studies

Cecilia Morgan

加急办理skku学位证书 韩国成均馆大学毕业证硕士文凭证书在读证明原版一模一样

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

From Globalization to Regionalization: The United States, China, and the Post-Covid-19 World Economic Order

- Research Article

- Published: 28 October 2020

- Volume 26 , pages 69–87, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Zhaohui Wang 1 &

- Zhiqiang Sun 2

30k Accesses

58 Citations

30 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The Covid-19 pandemic has intensified the debate among optimists, pessimists, and centrists about whether the world economic order is undergoing a fundamental change. While optimists foresee the continuation of economic globalization after the pandemic, pessimists expect localization instead of globalization, given the pandemic’s structural negative consequence on the world economy. By contrast, the centrists anticipate a “U-shaped” recovery, where Covid-19 will not kill globalization but slow it down. The three existing perspectives on Covid-19’s impact on the economic globalization are not without merit, but they do not take sufficient temporal distance from the ongoing issue. This article suggests employing the historical perspective to expand the time frame by examining the rise and fall of economic globalization before and after the 2008 global financial crisis. The authors argue that economic globalization has been in transition since the 2008 financial crisis, and one important but not exclusive factor to explain this change is the evolving US–China economic relationship, from symbiotic towards increasingly competitive. The economic restructuring in US and China has begun after both countries weathered the 2008 crisis and gained momentum since the outbreak of trade war and Covid-19. The article investigates this trend by distinguishing different types of production activities, and the empirical results confirm that localization and regionalization have been filling the vacuum of economic globalization in retreat in the last decade.

Similar content being viewed by others

Globalization After the Great Contraction: The Emergence of Zones of Exclusion

India and China: “Awakening Giants” Towards a Win–Win Future?

China and Central America

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

After the White House published the Trump administration’s first National Security Strategy (NSS) report in 2017, many analysts anticipated that it represented a significant shift in America’s China policy [ 42 , 44 ]. Indeed, the great power competition between Washington and Beijing has been intensified since then. After Trump announced a series of tariff plans on Chinese goods and US–China trade disputes rapidly escalated to an unprecedented level in 2018, many observers remarked that they were fundamentally driven by the increasingly competitive US–China relationship and that the negative consequences of a trade war could spill over into other domains such as technology, military, and ideology [ 47 , 59 ]. After Trump declared that America must win the race for 5G and the US government decided its ban on Huawei in 2019, commentators regarded it as a technology cold war and the prelude to the US–China new cold war, which would probably give rise to the disintegration of the existing world order [ 28 , 68 ]. As the tension and competition intensified, both sides seemingly reached a stalemate, and neither deviated from their course. The US–China rivalry has led to more serious concerns over the end of economic globalization and its negative impact on both American and Chinese economies as well as the global economy at large.

Worse still, after the outbreak of the Coronavirus disease (Covid-19) in December 2019, people who had expected transnational cooperation in the face of the threat to global health were disappointed to find that the conspiracy theories and blame games further intensified the competition of governance models between Washington and Beijing. Despite China’s prompt and effective response to the Covid-19, the Chinese government’s policies and measures have been, to a great extent, perceived by the American counterpart as an overwhelming state with strong capability of censorship and control in contrast to a penetrated society with limited autonomy. The Trump administration proclaimed that “as demonstrated by the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) response to the pandemic, Americans have more reason than ever to understand the nature of the regime in Beijing and the threats it poses to American economic interests, security, and values” [ 53 ]. Therefore, the White House released the United States Strategic Approach to the People’s Republic of China to detail a whole-of-government strategy to deal with China’s challenge and protect America’s interests [ 52 ]. By contrast, the Chinese leadership not only criticized the American counterpart’s scapegoating China for its own failure in coping with the pandemic but also endeavored to set China a strong example for successfully combating Covid-19 by the lengthy white paper China’s Action to Fight the Covid-19 [ 67 ]. Similar to the situation after the 2008 global financial crisis, China once again seemed to be more confident with its model of governance as an alternative to the Western liberal model in terms of crisis management [ 15 ]. In a nutshell, the Covid-19 pandemic has added more fuel to the fire by further advancing the US–China divergence and competition, thereby giving rise to the accelerated spiral deterioration of the bilateral relationship.

The Covid-19 pandemic is undoubtedly bringing a devastating blow for the global economy, according to World Bank’s report Global Economic Prospects in June 2020 [ 63 ], but how it will influence the trajectory of economic globalization is not without controversy. The article attempts to explore what impacts Covid-19 would have on the world economic order in the context of US–China competition. Will economic globalization recover and proceed soon after the world weathers the Covid-19 crisis? Or will the US–China rivalry and the Covid-19 pandemic lead to more regional or even local (national) production? Though it is difficult to make any precise prediction in the midst of an unfolding event, it is not difficult to find optimists, pessimists and centrists of economic globalization amid the current crisis. While optimists foresee the continuation of globalization after the pandemic, pessimists expect localization instead of globalization, given the pandemic’s structural negative consequence on the world economy. By contrast, the centrists anticipate a “U-shaped” recovery, where Covid-19 will not kill globalization but slow it down. The three existing perspectives are not without merit, but the authors do not take the three scenarios as equally likely.

More importantly, the authors understand the difficulty of dealing with a present and evolving issue like the world economic order under the great power politics and the Covid-19 pandemic. Therefore, the authors suggest employing the historical perspective that enables us to study particular moments, events, and critical junctures in the context of broader movements of historical processes. Specifically, the article expands the time frame by examining the rise and fall of economic globalization before and after the 2008 global financial crisis and considers the particular impact of the Covid-19 pandemic in the historical process.

Our article has two key findings. First, the authors argue that economic globalization has been in transition since the 2008 financial crisis and that one important but not exclusive factor in explaining this change is the evolving US–China economic relationship, from symbiotic towards increasingly competitive. The economic restructuring in US and China has begun after both countries weathered the 2008 crisis and gained momentum since the outbreak of trade war and Covid-19. Second, the authors also find that localization and regionalization have been filling the vacuum of globalization in retreat in the process, which provides us a better understanding, or at least a reasonable conjecture, of the potential long-term impact of the pandemic on the world economic order.

The article begins with a brief review of the contending views on economic globalization and discusses the historical perspective to explore the changing dynamics of world economic order. Then the authors will examine how economic globalization evolves along with the US–China economic relationship in the new millennium. Based on the above analysis, the article further explores the alternative forms of production and trade in more depth and situate the impact of the US–China tariffs and the Covid-19 pandemic on the world economic order in the general trend. Finally, the article summarizes the main points and makes some suggestions for further research.

Contending Views on the Economic Globalization and the Historical Perspective

Pundits and policymakers have described the emerging world order in a variety of ways: “a world without superpowers,” “G-zero world,” “no-one’s world,” “multiplex,” “multipolar,” and so on [ 1 , 5 , 7 , 12 , 31 ]. If the 2008 global financial crisis is the prelude of the changing world order, US–China competition and Covid-19 definitely speed up the tempo. Kissinger even suggests that the Covid-19 pandemic will forever alter the world order [ 30 ]. This article focuses on the economic dimension and discusses what the world economic order would be like.

Economic globalization has sped up to an unprecedented pace since the 1980s and swept almost every corner of the world in the past few decades. While the two major crises—the 1997 Asian financial crisis and the 2008 global financial crisis—have corrected the hyper-globalist view that globalization is an irreversible and formidable project, liberal institutionalists still hold a firm belief that the world economic order based on the liberal, rule-based, and multilateral principle is resilient and durable [ 23 , 24 ]. However, after Trump took office, his attacks on the liberal world order, including but not limited to trade, multilateralism, international law, environmental protection, and human rights, have fundamentally questioned its survival [ 25 ]. With the Covid-19 soaring around the world, three contending views—optimists, pessimists, and centrists—could be identified within the existing literature on economic globalization. This section offers a critical review of the existing views and suggests that the historical perspective could be useful in understanding the trajectory of economic globalization.

First, the globalists still take a sanguine view of economic globalization in the near future. Optimists argue that, despite a certain degree of disruption to the international economic order during the pandemic, it is expected to return to the pre-crisis trajectory soon after the pandemic is contained. Economic globalization will continue once the market weathers the shock of the virus and the economic recession is ended. The most important reason is that no prior shocks, including epidemics such as the 2002–2004 SARS outbreak, 1968 H3N2 pandemic (Hong Kong flu), 1958 H2N2 pandemic (Asian flu), and 1918 H1N1 pandemic (Spanish flu), have done structural damage to the affected economies and fundamentally changed the nature of international economic order [ 9 , 27 ]. Since statistics show that economic recovery from the prior pandemics was quick (i.e., V-shaped), economic recovery from Covid-19 will be more similar than different this time, as social distancing nowadays is not dramatically different from then [ 37 ]. Furthermore, optimists, especially the liberal internationalists, also strive to argue that Covid-19 will not kill globalization but reveal no one can go it alone. Covid-19 will make political leaders more aware that international cooperation is critical for effective mass testing and treatment for the virus, and then countries are expected to work together to improve production and distribution [ 18 , 26 ].

Second, in contrast to the optimists, pessimists expect localization instead of globalization given the pandemic’s structural negative consequence on globalization. They have little hope of effective international cooperation under the current structure (underlying anarchy) of global governance on the one hand [ 40 ] and believe that Covid-19 will have significant and sustaining structural damage to the world economy on the other [ 63 ]. For instance, according to a recent poll from Reuters, nearly half of the economists expect a U-shaped recovery, more than any other option such as V-shaped or L-shaped [ 46 ]. Paulson [ 41 ] suggests that Covid-19 has triggered the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression and foresees a future that “belongs to the techno-nationalists” owing to “Beijing’s emphasis on indigenisation and Washington’s on relocating supply chains and sequestering technology.” In this scenario, pessimists view the Covid-19 crisis as a systemic and long-lasting crisis that is even more severe than the 2008 global financial crisis and, to a great extent, comparable to the Great Depression. The virus’s structural negative effect, as well as the lack of international coordination and cooperation, will put an end to this round of economic globalization. Given this, we should expect a wave of economic nationalism and localization to replace globalization. While both inter-regional and intra-regional production and trade will decrease, the share of domestic economic activities will rise.

Third, the centrists, as the name suggests, stand somewhere in the middle: The world economy will recover anyway, but not as quickly as optimists anticipate and as hard-hit as pessimists foresee. In this scenario, it is tempting to compare the current Covid-19 crisis to the 2008 global financial crisis: both have produced extraordinary volatility in financial markets and caused far-reaching economic repercussions. It is argued that Covid-19 will not kill globalization, but globalization will slow down after all. Many terms have been coined to describe this picture. For example, Zheng [ 69 ] suggests that economic globalization will not simply ebb but return to “limited globalization,” similar to the one before the 1980s. Bakas coins the term “slowbalisation” to describe the faltering globalization in the last few years [ 48 ]. Regardless of the terms, the new normal of economic globalization essentially has two implications. First, it implies continued integration of the global economy but albeit at a significantly slower pace. Second, “slowbalization will lead to deeper links within regional blocs” [ 49 ]. As Covid-19 has exposed the dangers of relying on any one country for needed inputs or final products, it is important for countries to regionalize their supply chains and companies to diversify their trading partners in the face of a considerable period of slower economic growth. In a nutshell, Covid-19 will not put an end to economic globalization; rather, it will promote other forms of economic integration such as regionalization.

While the three perspectives are not without merit, especially insofar as they propose different scenarios of how we could grasp the potential impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the economic globalization, the three scenarios should not be treated as equally likely. Specifically, it is very unlikely that, as the optimists expect, a quick recovery of the world economy and economic globalization will happen in a few months. It is not difficult to draw this conclusion if we carefully read China as a typical case study. Even if China was the first country to impose stringent lockdown measures, the first to lift them, and the first to get some economic activities back on track, the Chinese economy is unlikely to return to normalcy until the last quarter of 2020 [ 70 ]. More importantly, there are good reasons to be skeptical that other countries will and can follow China’s model of containing the virus. For instance, Normand suggests that “the U.S. and global economy might exhibit more U than V-shaped characteristics as occurred after the global financial crisis, so will likely fail to recoup its 2020 first half output loss even by the end of 2021” [ 27 ]. Under the circumstance, the Covid-19 pandemic is expected to bring sustained disruptions to global trade, supply chains, and investment flows.

Despite the above seemingly plausible analysis, we have to admit that it is currently difficult to draw any firm conclusion and prediction in the midst of an unfolding event, as the future is undeniably influenced by many uncertain factors. In this case, the authors suggest that, if we employ the historical perspective to take a longer-run view, we can get a more comprehensive and clearer picture of how economic globalization gains and loses momentum. It helps us to explore the particular impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the world economic order and find which scenario to be more likely afterward.

However, it is worth clarifying the historical perspective herein before we embark on the historical analysis, as IR scholars have examined history in different ways and deployed history for different purposes [ 8 , 10 , 11 , 20 , 33 , 57 ]. The authors do not intend to add further fuel to the existing debates among the various historical perspectives [ 6 ], but to state clearly that they have referred the aforementioned historical perspective in this article to a research method. This historical method does not simply mean looking back to history, which is of course necessary, but more importantly, it studies particular moments, events, and critical junctures in the context of broader movements of historical processes [ 34 ]. As Ziblatt [ 71 :3] suggests, “temporal distance—moving out from single events and placing them within a longer time frame—can also expose previously undetectable social patterns.” Like archaeologists working too close to the ground, we may fail to see the trajectory of economic globalization if we do not take sufficient temporal distance from the Covid-19 crisis. All three existing perspectives on Covid-19’s impact on the world economy and globalization have such a shortcoming, and this article strives to highlight this crucial issue. Therefore, the authors propose to shift our perspective and examine the trajectory of globalization within a longer time frame. The length of the time frame is of course not fixed and hinges on the object of study. In this research, the authors propose a range of twenty years to examine the continuities and changes in the cycle of globalization and deglobalization in the new millennium. The longer-run view is helpful in discerning not only the important pattern of a historical process but also the particular impact of a historical event such as an economic crisis and a deadly pandemic. We can probably gain a better understanding of the post-pandemic world economic order if we take Covid-19’s impact into account within the historical dynamics of economic globalization.

The Ebb and Flow of Economic Globalization before and after the 2008 Crisis

The section examines the turning points as well as the ebb and flow in the evolution of economic globalization in the new millennium. As America and China are two of the most important economies and their economic relationship is critically important for globalization in the twenty-first century, the authors will read it as a typical case study to examine how economic globalization evolves along with the bilateral economic relationship.

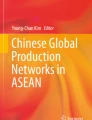

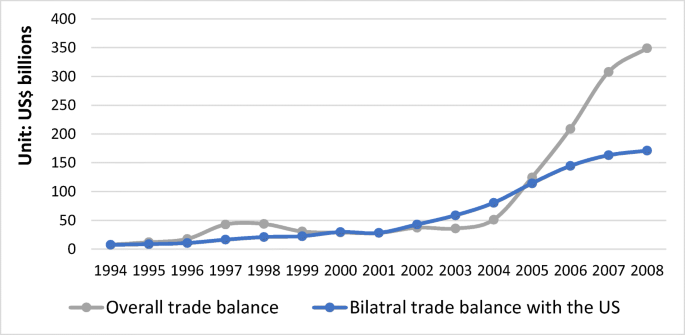

Before the 2008 financial crisis, the US–China economic relationship was more complimentary and cooperative in nature. America and China essentially formed a symbiotic relationship: the US consumed China’s cheap exports, paying China in dollars, and China held US dollars and bonds, in fact, lending money to the US. Essentially, China’s export-driven growth and its accumulation of dollar reserves and US debts were closely intertwined with the dollar hegemony in the international monetary system and America’s increasing over-drafting consumption and trade deficit [ 16 , 21 , 22 ]. Some observers even perceived the two economies as conjoined twins, “ChinAmerica” [ 29 ] or “Chimerica” [ 17 ], which was based on Chinese export-led growth and American overconsumption. The US–China symbiotic economic relationship was demonstrated in Figs. 1 and 2 . Figure 1 shows China’s overall trade surplus and a bilateral trade surplus with the US from 1994 to 2008. After its accession to the WTO membership in 2001, China’s position in global trade and payments substantially changed. Its trade surplus rose sharply from 2003, as did its bilateral trade surplus with the US. Figure 2 reveals the corresponding dramatic increase in China’s holdings of foreign reserves and US securities from 2001 to 2008. It is estimated that about two-thirds of China’s reserves were held in the form of dollar debt [ 58 ].

China’s overall trade surplus and a bilateral trade surplus with the US, 1994–2008. Source: IMF Direction of Trade Statistics (March 2020 Edition), https://stats2.digitalresources.jisc.ac.uk/?Dataset=DOTS&ShowOnWeb=true&Lang=en

China’s foreign reserves and holdings of US securities, 2001–2008. Source: IMF International Financial Statistics (March 2020 Edition), https://stats2.digitalresources.jisc.ac.uk/?Dataset=DOTS&ShowOnWeb=true&Lang=en

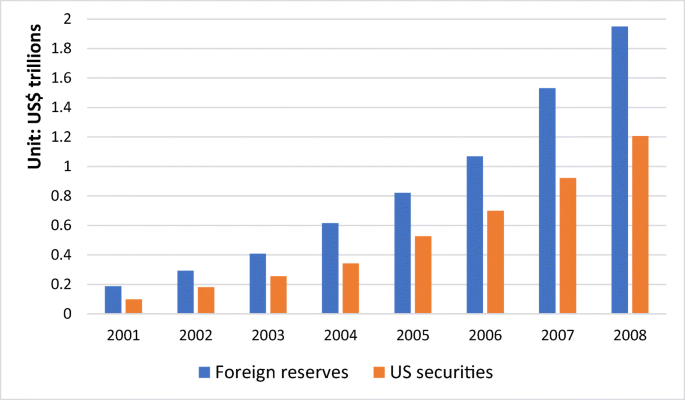

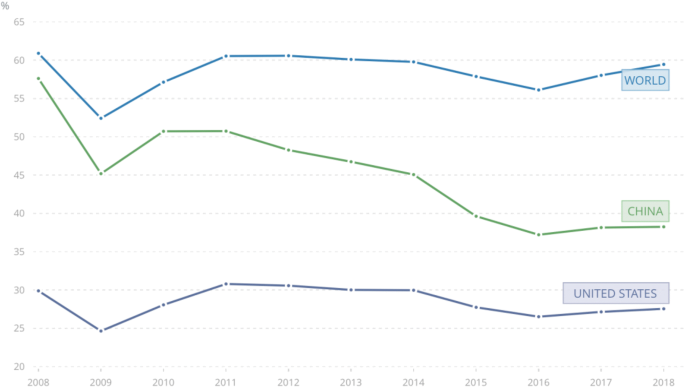

Therefore, after its accession to the WTO membership in 2001, China developed its complementary economic relationship with the US and increasingly integrated into the world economy. The US–China economic relationship was one of the most important engines of economic globalization before 2008. As Fig. 3 demonstrates, the world trade as a percentage of the world GDP was generally on the rise during the golden period of economic globalization; the ratio of China’s international trade to GDP climbed up from around 40% to more than 60% quickly in the process, and the US experienced slow but steady growth as well after the economic downturn in 2001.

Trade as % of GDP: World, the US, and China, 2000–2008. Source: World Bank Data

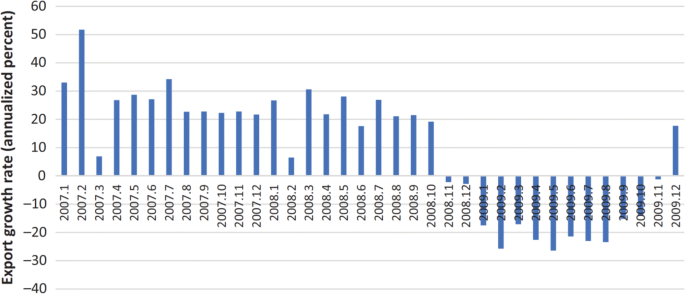

However, with the benefit of hindsight, the 2008 global financial crisis marked an important turning point in the trajectory of economic globalization. The crisis exposed China’s severe vulnerability in the symbiotic economic relationship with the US. Figure 4 shows while China’s exports grew by an average of more than 20% month-by-month for most of 2008, they fell dramatically by 2.2% in November and experienced considerable negative growth in 2009, which made China’s political elites more aware of the disadvantages of over-dependence on the US market and dollar. Under the circumstance, the Chinese government rolled out a series of ad hoc rescue policies, including the mega fiscal stimulus plan and expansionary monetary policy in 2009. Though the Hu-Wen administration recognized the unsustainability of China’s export-driven growth model, the Chinese leadership placed priority on growth and stability and put domestic economic reforms in the secondary place in the face of the crisis.

China’s monthly export growth rate, 2007–2009. Source: National Bureau of Statistics, People’s Republic of China, https://data.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=A01

More importantly, after both countries weathered the crisis, the US–China economic relationship became increasingly competitive. This is a result of a variety of factors, including China’s domestic economic reforms and growing ambition in global economic governance [ 60 ]. It is worth noting that after he consolidated and centralized power within China’s political system, Xi Jinping was more confident and capable in carrying out substantial reforms in both domestic and international domains.

Domestically, Xi clearly aimed to change China’s growth model to one driven by domestic consumption and innovation, instead of inexpensive exports and low-efficiency investments [ 65 ]. Not only did China demonstrate its plan to steer away from labor-intensive industries to high-tech manufacturing, it also showed its ambition to become a global leader in innovation by releasing the national blueprint “Made in China 2025.” The guideline pledges that “China will be an innovative nation by 2020, an international leader in innovation by 2030, and a world powerhouse of scientific and technological innovation by 2050” [ 51 ].

Internationally, China gradually became a proactive participant in global economic governance under the Xi administration. China put forward the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and established the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) to fund infrastructural projects in Asia. Though China claimed that both BRI and AIIB had a supplementary nature to the pre-existing institutions such as World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF), many consider them as China’s challenge to the pillars of the US-dominated liberal world order. The stories of how Beijing built an alliance to create AIIB in the face of Washington’s opposition and how Washington forged the Indo-Pacific alliance to contain BRI’s increasing influence demonstrate the contestation between the US and China for leadership in global economic governance [ 14 , 45 ].

With China’s continued economic restructuring and industrial policy, China was upgrading its exports from labor-intensive to more capital and technology-intensive products, which caused more competition with products manufactured in advanced/industrialized countries. China’s attempt to expand its economic and financial influence regionally and internationally further intensified the competition. This growing competitive nature of the US–China economic relationship after the 2008 global financial crisis has also been captured by empirical studies. For instance, Kwan [ 32 ] finds that owing to China’s increasingly sophisticated trade structure in recent years, China’s complementarity with industrialized countries (the United States, Japan, and Germany) has been diminishing, and competition with newly industrializing economies (India and Indonesia) and resource countries (Australia and Russia) has also been decreasing.

While the US–China symbiotic economic relationship added momentum to economic globalization before 2008, the increasingly competitive nature of the bilateral economic relationship slowed it down, if not to say reversing the trend. As Fig. 5 suggests, international trade was severely hit and then recovered from the 2008 global financial crisis, but the world trade as a percentage of world GDP did not continue to grow after 2011. During the period from 2011 to 2018, China’s trade-to-GDP ratio experienced a significant decline, from more than 50% down to less than 40%, compared to America’s slow and slight counterpart, with no more than 5% decrease. This corresponds with the aforementioned cases in which China was more proactive in adjusting its economic relationship with the US and its way to participate in economic globalization after the 2008 global financial crisis.

Trade as % of GDP: World, the US, and China, 2008–2018. Source: World Bank Data

Now we can gain a better understanding that economic globalization has been in transition since the 2008 financial crisis. The world economy experienced a U-shaped recovery after the 2008 crisis, and some fundamental changes in the nature of globalization have taken place since then. Economic globalization reached the turning point in the 2008 crisis, and the aforementioned slowbalization is quite accurate to describe the subsequent development, if not to say reversed globalization. One important but not exclusive factor in explaining this change is the evolving US–China economic relationship, from symbiotic towards increasingly competitive. This is, of course, not to say that the US and China have no or little economic complementarity presently. Economic indicators such as US–China bilateral trade volume and China’s holdings of US Treasury bonds suggest that the two countries are still very important economic partners to each other. It would be a mistake, or at least too early, to say that the nature of the US–China economic relationship has fundamentally changed at this stage. The emphasis of this section is not on the transformed consequence but on the evolutionary process, in which the US experienced intensified anxiety regarding China’s growing competitiveness. In this sense, it would be easier to understand why several key US government agencies expressed such concerns in 2017 and Trump began to fight a trade war against China after 2018 [ 55 , 56 ]. Though there is no official data from World Bank for 2019 and 2020 yet, it is plausible to speculate that the global and bilateral trade would further shrink with the US–China tariffs implemented and the outbreak of Covid-19 [ 4 , 64 ]. While the trade war reveals the risk of manufacturing goods in China for export and highlights the need to deliver the production of some goods elsewhere, the Covid-19 further drives the American government and companies to move US production and supply chain dependency away from China. The following section will further analyze how regional and domestic forms of production and trade developed in the face of slowbalization after the 2008 crisis.

Exploring Globalization, Regionalization, and Localization: Some Empirical Results

The historical perspective has shed light on the ebb and flow of economic globalization along with the evolving US–China economic relationship from symbiotic towards increasingly competitive before and after the 2008 global financial crisis. It suggests that the economic restructuring in US and China has begun after both countries weathered the 2008 crisis and gained momentum since the outbreak of trade war and Covid-19. However, it is worth exploring the economic restructuring in more depth or, put more specifically, to examine the alternative forms of production and trade in the face of globalization in retreat after the 2008 crisis. The authors find that localization and regionalization have been filling the vacuum of globalization in retreat in the slowbalization process.

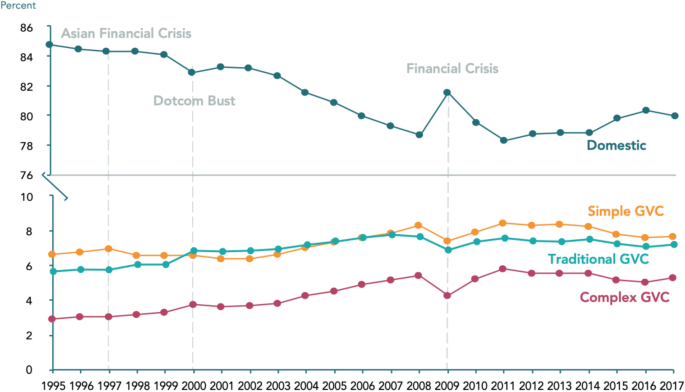

Before we set out on the journey, we need to distinguish different types of production activities. The authors follow the methodology of Wang et al. to decompose production activities into four types [ 61 ]. The first type, purely domestic or localized, is added value produced and the final product consumed at home without involving international trade. The second type, traditional international trade, is an added value produced at home and final product exported for international consumption, such as China’s cloth in exchange for America’s soybeans. The third and fourth types involve intermediate trade and cross-border production. The third is a simple type of global value chain (GVC) when the intermediate product crosses border once for foreign production, such as China’s steel produced for America’s building. The fourth is a complex type of GVC if the intermediate product crosses borders at least twice to produce final export for other countries, such as iPhone’s manufacturing lines [ 62 ].

After the decomposition, Fig. 6 demonstrates how the four types of production activities evolved from 1995 to 2017. A few patterns are noteworthy. First, the relative importance of domestic production activities was decreasing before 2008, while the shares of traditional, simple, and complex GVCs were generally increasing. This corresponds with our aforementioned analysis that economic globalization before the 2008 global financial crisis. Moreover, it further demonstrates that economic globalization was, to a larger extent, driven by the complex GVC activities, whose share experienced a faster increase that those of tradition and simple GVCs. Second, after the shape decline of international trade in 2009, all three GVC activities took two years to return to the pre-crisis level, which resonated with the U-shaped recovery of the world economy. Third, the relative importance of domestic production activities was increasing after 2011, while traditional, simple, and complex GVCs was generally decreasing. The decline was the steepest for complex GVC activities, and this once again corresponds with our aforementioned analysis that the 2008 global financial crisis was a watershed and that globalization slowed down subsequently.

Four types of production activities as a share of global GDP, 1995–2017. Source: Xin Li, Bo Meng, and Zhi Wang, “Recent patterns of global production and GVC participation,” in World Bank and World Trade Organization, Global Value Chain Development Report 2019 , Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group, p. 12