34th Annual

Ethnographic & qualitative research conference (eqrc), march 21-22 , 2022.

Proposal Submission extended deadline is FEBRUARY 28, 2022.

Registration extended deadline is Monday, MARCH 1 4 , 2022.

Virtual Conference

Due to the c ontinuing Covid-19 pandemic circumstances, EQRC will be held again as a " virtual conference ," during March 21-2 2, 2022 .

Both pre-recorded lecture sessions as well as poster sessions will be posted on the conference website in an open-view format. These will remain available through the link for registered participants through August 1, 2022.

Call for Papers

W e invite scholars to participate in the conference by presenting research projects among a broad spectrum of topics. Employment of traditional ethnographic and qualitative research projects provides the common thread for conference papers.

Proposals will be peer-reviewed among three strands: Results of qualitative and ethnographic research studies , qualitative research methods , and pedagogical issues in qualitative research.

Formats include lecture and poster presentations. The lectures will be 15-minute video presentations by authors and posters will be posted via PDF documents (see details HERE ) . Authors may request respective formats and all presentations (videos/posters) will be posted on the conference web page.

Submit a proposal that includes a title, an abstract of not more than 150 words, and a summary that does not exceed more than 600 words. If the proposal is accepted for presentation, then the title, abstract and a URL to your lecture or poster will all be included in the conference program.

Registration extended deadline is Monday, MARCH 14, 2022.

The EQRC conference has a long tradition of reputable quality, including previous hosting institutions being University of Massachusetts, Columbia University, Duquesne University, SUNY at Albany, Cedarville University, and University of Nevada at Las Vegas.

Presenters of both lecture and poster session presentations may submit their written papers for journal publication consideration. After a peer-review proc ess (different from conference review) these submitted papers, if selected, will be published in the quarterly issued Journal of Ethnographic & Qualitative Research (JEQR). To learn more about JEQR, please go to the website at www.jeqr.org .

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Practical thematic...

Practical thematic analysis: a guide for multidisciplinary health services research teams engaging in qualitative analysis

- Related content

- Peer review

- Catherine H Saunders , scientist and assistant professor 1 2 ,

- Ailyn Sierpe , research project coordinator 2 ,

- Christian von Plessen , senior physician 3 ,

- Alice M Kennedy , research project manager 2 4 ,

- Laura C Leviton , senior adviser 5 ,

- Steven L Bernstein , chief research officer 1 ,

- Jenaya Goldwag , resident physician 1 ,

- Joel R King , research assistant 2 ,

- Christine M Marx , patient associate 6 ,

- Jacqueline A Pogue , research project manager 2 ,

- Richard K Saunders , staff physician 1 ,

- Aricca Van Citters , senior research scientist 2 ,

- Renata W Yen , doctoral student 2 ,

- Glyn Elwyn , professor 2 ,

- JoAnna K Leyenaar , associate professor 1 2

- on behalf of the Coproduction Laboratory

- 1 Dartmouth Health, Lebanon, NH, USA

- 2 Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth College, Lebanon, NH, USA

- 3 Center for Primary Care and Public Health (Unisanté), Lausanne, Switzerland

- 4 Jönköping Academy for Improvement of Health and Welfare, School of Health and Welfare, Jönköping University, Jönköping, Sweden

- 5 Highland Park, NJ, USA

- 6 Division of Public Health Sciences, Department of Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis, MO, USA

- Correspondence to: C H Saunders catherine.hylas.saunders{at}dartmouth.edu

- Accepted 26 April 2023

Qualitative research methods explore and provide deep contextual understanding of real world issues, including people’s beliefs, perspectives, and experiences. Whether through analysis of interviews, focus groups, structured observation, or multimedia data, qualitative methods offer unique insights in applied health services research that other approaches cannot deliver. However, many clinicians and researchers hesitate to use these methods, or might not use them effectively, which can leave relevant areas of inquiry inadequately explored. Thematic analysis is one of the most common and flexible methods to examine qualitative data collected in health services research. This article offers practical thematic analysis as a step-by-step approach to qualitative analysis for health services researchers, with a focus on accessibility for patients, care partners, clinicians, and others new to thematic analysis. Along with detailed instructions covering three steps of reading, coding, and theming, the article includes additional novel and practical guidance on how to draft effective codes, conduct a thematic analysis session, and develop meaningful themes. This approach aims to improve consistency and rigor in thematic analysis, while also making this method more accessible for multidisciplinary research teams.

Through qualitative methods, researchers can provide deep contextual understanding of real world issues, and generate new knowledge to inform hypotheses, theories, research, and clinical care. Approaches to data collection are varied, including interviews, focus groups, structured observation, and analysis of multimedia data, with qualitative research questions aimed at understanding the how and why of human experience. 1 2 Qualitative methods produce unique insights in applied health services research that other approaches cannot deliver. In particular, researchers acknowledge that thematic analysis is a flexible and powerful method of systematically generating robust qualitative research findings by identifying, analysing, and reporting patterns (themes) within data. 3 4 5 6 Although qualitative methods are increasingly valued for answering clinical research questions, many researchers are unsure how to apply them or consider them too time consuming to be useful in responding to practical challenges 7 or pressing situations such as public health emergencies. 8 Consequently, researchers might hesitate to use them, or use them improperly. 9 10 11

Although much has been written about how to perform thematic analysis, practical guidance for non-specialists is sparse. 3 5 6 12 13 In the multidisciplinary field of health services research, qualitative data analysis can confound experienced researchers and novices alike, which can stoke concerns about rigor, particularly for those more familiar with quantitative approaches. 14 Since qualitative methods are an area of specialisation, support from experts is beneficial. However, because non-specialist perspectives can enhance data interpretation and enrich findings, there is a case for making thematic analysis easier, more rapid, and more efficient, 8 particularly for patients, care partners, clinicians, and other stakeholders. A practical guide to thematic analysis might encourage those on the ground to use these methods in their work, unearthing insights that would otherwise remain undiscovered.

Given the need for more accessible qualitative analysis approaches, we present a simple, rigorous, and efficient three step guide for practical thematic analysis. We include new guidance on the mechanics of thematic analysis, including developing codes, constructing meaningful themes, and hosting a thematic analysis session. We also discuss common pitfalls in thematic analysis and how to avoid them.

Summary points

Qualitative methods are increasingly valued in applied health services research, but multidisciplinary research teams often lack accessible step-by-step guidance and might struggle to use these approaches

A newly developed approach, practical thematic analysis, uses three simple steps: reading, coding, and theming

Based on Braun and Clarke’s reflexive thematic analysis, our streamlined yet rigorous approach is designed for multidisciplinary health services research teams, including patients, care partners, and clinicians

This article also provides companion materials including a slide presentation for teaching practical thematic analysis to research teams, a sample thematic analysis session agenda, a theme coproduction template for use during the session, and guidance on using standardised reporting criteria for qualitative research

In their seminal work, Braun and Clarke developed a six phase approach to reflexive thematic analysis. 4 12 We built on their method to develop practical thematic analysis ( box 1 , fig 1 ), which is a simplified and instructive approach that retains the substantive elements of their six phases. Braun and Clarke’s phase 1 (familiarising yourself with the dataset) is represented in our first step of reading. Phase 2 (coding) remains as our second step of coding. Phases 3 (generating initial themes), 4 (developing and reviewing themes), and 5 (refining, defining, and naming themes) are represented in our third step of theming. Phase 6 (writing up) also occurs during this third step of theming, but after a thematic analysis session. 4 12

Key features and applications of practical thematic analysis

Step 1: reading.

All manuscript authors read the data

All manuscript authors write summary memos

Step 2: Coding

Coders perform both data management and early data analysis

Codes are complete thoughts or sentences, not categories

Step 3: Theming

Researchers host a thematic analysis session and share different perspectives

Themes are complete thoughts or sentences, not categories

Applications

For use by practicing clinicians, patients and care partners, students, interdisciplinary teams, and those new to qualitative research

When important insights from healthcare professionals are inaccessible because they do not have qualitative methods training

When time and resources are limited

Steps in practical thematic analysis

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

We present linear steps, but as qualitative research is usually iterative, so too is thematic analysis. 15 Qualitative researchers circle back to earlier work to check whether their interpretations still make sense in the light of additional insights, adapting as necessary. While we focus here on the practical application of thematic analysis in health services research, we recognise our approach exists in the context of the broader literature on thematic analysis and the theoretical underpinnings of qualitative methods as a whole. For a more detailed discussion of these theoretical points, as well as other methods widely used in health services research, we recommend reviewing the sources outlined in supplemental material 1. A strong and nuanced understanding of the context and underlying principles of thematic analysis will allow for higher quality research. 16

Practical thematic analysis is a highly flexible approach that can draw out valuable findings and generate new hypotheses, including in cases with a lack of previous research to build on. The approach can also be used with a variety of data, such as transcripts from interviews or focus groups, patient encounter transcripts, professional publications, observational field notes, and online activity logs. Importantly, successful practical thematic analysis is predicated on having high quality data collected with rigorous methods. We do not describe qualitative research design or data collection here. 11 17

In supplemental material 1, we summarise the foundational methods, concepts, and terminology in qualitative research. Along with our guide below, we include a companion slide presentation for teaching practical thematic analysis to research teams in supplemental material 2. We provide a theme coproduction template for teams to use during thematic analysis sessions in supplemental material 3. Our method aligns with the major qualitative reporting frameworks, including the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ). 18 We indicate the corresponding step in practical thematic analysis for each COREQ item in supplemental material 4.

Familiarisation and memoing

We encourage all manuscript authors to review the full dataset (eg, interview transcripts) to familiarise themselves with it. This task is most critical for those who will later be engaged in the coding and theming steps. Although time consuming, it is the best way to involve team members in the intellectual work of data interpretation, so that they can contribute to the analysis and contextualise the results. If this task is not feasible given time limitations or large quantities of data, the data can be divided across team members. In this case, each piece of data should be read by at least two individuals who ideally represent different professional roles or perspectives.

We recommend that researchers reflect on the data and independently write memos, defined as brief notes on thoughts and questions that arise during reading, and a summary of their impressions of the dataset. 2 19 Memoing is an opportunity to gain insights from varying perspectives, particularly from patients, care partners, clinicians, and others. It also gives researchers the opportunity to begin to scope which elements of and concepts in the dataset are relevant to the research question.

Data saturation

The concept of data saturation ( box 2 ) is a foundation of qualitative research. It is defined as the point in analysis at which new data tend to be redundant of data already collected. 21 Qualitative researchers are expected to report their approach to data saturation. 18 Because thematic analysis is iterative, the team should discuss saturation throughout the entire process, beginning with data collection and continuing through all steps of the analysis. 22 During step 1 (reading), team members might discuss data saturation in the context of summary memos. Conversations about saturation continue during step 2 (coding), with confirmation that saturation has been achieved during step 3 (theming). As a rule of thumb, researchers can often achieve saturation in 9-17 interviews or 4-8 focus groups, but this will vary depending on the specific characteristics of the study. 23

Data saturation in context

Braun and Clarke discourage the use of data saturation to determine sample size (eg, number of interviews), because it assumes that there is an objective truth to be captured in the data (sometimes known as a positivist perspective). 20 Qualitative researchers often try to avoid positivist approaches, arguing that there is no one true way of seeing the world, and will instead aim to gather multiple perspectives. 5 Although this theoretical debate with qualitative methods is important, we recognise that a priori estimates of saturation are often needed, particularly for investigators newer to qualitative research who might want a more pragmatic and applied approach. In addition, saturation based, sample size estimation can be particularly helpful in grant proposals. However, researchers should still follow a priori sample size estimation with a discussion to confirm saturation has been achieved.

Definition of coding

We describe codes as labels for concepts in the data that are directly relevant to the study objective. Historically, the purpose of coding was to distil the large amount of data collected into conceptually similar buckets so that researchers could review it in aggregate and identify key themes. 5 24 We advocate for a more analytical approach than is typical with thematic analysis. With our method, coding is both the foundation for and the beginning of thematic analysis—that is, early data analysis, management, and reduction occur simultaneously rather than as different steps. This approach moves the team more efficiently towards being able to describe themes.

Building the coding team

Coders are the research team members who directly assign codes to the data, reading all material and systematically labelling relevant data with appropriate codes. Ideally, at least two researchers would code every discrete data document, such as one interview transcript. 25 If this task is not possible, individual coders can each code a subset of the data that is carefully selected for key characteristics (sometimes known as purposive selection). 26 When using this approach, we recommend that at least 10% of data be coded by two or more coders to ensure consistency in codebook application. We also recommend coding teams of no more than four to five people, for practical reasons concerning maintaining consistency.

Clinicians, patients, and care partners bring unique perspectives to coding and enrich the analytical process. 27 Therefore, we recommend choosing coders with a mix of relevant experiences so that they can challenge and contextualise each other’s interpretations based on their own perspectives and opinions ( box 3 ). We recommend including both coders who collected the data and those who are naive to it, if possible, given their different perspectives. We also recommend all coders review the summary memos from the reading step so that key concepts identified by those not involved in coding can be integrated into the analytical process. In practice, this review means coding the memos themselves and discussing them during the code development process. This approach ensures that the team considers a diversity of perspectives.

Coding teams in context

The recommendation to use multiple coders is a departure from Braun and Clarke. 28 29 When the views, experiences, and training of each coder (sometimes known as positionality) 30 are carefully considered, having multiple coders can enhance interpretation and enrich findings. When these perspectives are combined in a team setting, researchers can create shared meaning from the data. Along with the practical consideration of distributing the workload, 31 inclusion of these multiple perspectives increases the overall quality of the analysis by mitigating the impact of any one coder’s perspective. 30

Coding tools

Qualitative analysis software facilitates coding and managing large datasets but does not perform the analytical work. The researchers must perform the analysis themselves. Most programs support queries and collaborative coding by multiple users. 32 Important factors to consider when choosing software can include accessibility, cost, interoperability, the look and feel of code reports, and the ease of colour coding and merging codes. Coders can also use low tech solutions, including highlighters, word processors, or spreadsheets.

Drafting effective codes

To draft effective codes, we recommend that the coders review each document line by line. 33 As they progress, they can assign codes to segments of data representing passages of interest. 34 Coders can also assign multiple codes to the same passage. Consensus among coders on what constitutes a minimum or maximum amount of text for assigning a code is helpful. As a general rule, meaningful segments of text for coding are shorter than one paragraph, but longer than a few words. Coders should keep the study objective in mind when determining which data are relevant ( box 4 ).

Code types in context

Similar to Braun and Clarke’s approach, practical thematic analysis does not specify whether codes are based on what is evident from the data (sometimes known as semantic) or whether they are based on what can be inferred at a deeper level from the data (sometimes known as latent). 4 12 35 It also does not specify whether they are derived from the data (sometimes known as inductive) or determined ahead of time (sometimes known as deductive). 11 35 Instead, it should be noted that health services researchers conducting qualitative studies often adopt all these approaches to coding (sometimes known as hybrid analysis). 3

In practical thematic analysis, codes should be more descriptive than general categorical labels that simply group data with shared characteristics. At a minimum, codes should form a complete (or full) thought. An easy way to conceptualise full thought codes is as complete sentences with subjects and verbs ( table 1 ), although full sentence coding is not always necessary. With full thought codes, researchers think about the data more deeply and capture this insight in the codes. This coding facilitates the entire analytical process and is especially valuable when moving from codes to broader themes. Experienced qualitative researchers often intuitively use full thought or sentence codes, but this practice has not been explicitly articulated as a path to higher quality coding elsewhere in the literature. 6

Example transcript with codes used in practical thematic analysis 36

- View inline

Depending on the nature of the data, codes might either fall into flat categories or be arranged hierarchically. Flat categories are most common when the data deal with topics on the same conceptual level. In other words, one topic is not a subset of another topic. By contrast, hierarchical codes are more appropriate for concepts that naturally fall above or below each other. Hierarchical coding can also be a useful form of data management and might be necessary when working with a large or complex dataset. 5 Codes grouped into these categories can also make it easier to naturally transition into generating themes from the initial codes. 5 These decisions between flat versus hierarchical coding are part of the work of the coding team. In both cases, coders should ensure that their code structures are guided by their research questions.

Developing the codebook

A codebook is a shared document that lists code labels and comprehensive descriptions for each code, as well as examples observed within the data. Good code descriptions are precise and specific so that coders can consistently assign the same codes to relevant data or articulate why another coder would do so. Codebook development is iterative and involves input from the entire coding team. However, as those closest to the data, coders must resist undue influence, real or perceived, from other team members with conflicting opinions—it is important to mitigate the risk that more senior researchers, like principal investigators, exert undue influence on the coders’ perspectives.

In practical thematic analysis, coders begin codebook development by independently coding a small portion of the data, such as two to three transcripts or other units of analysis. Coders then individually produce their initial codebooks. This task will require them to reflect on, organise, and clarify codes. The coders then meet to reconcile the draft codebooks, which can often be difficult, as some coders tend to lump several concepts together while others will split them into more specific codes. Discussing disagreements and negotiating consensus are necessary parts of early data analysis. Once the codebook is relatively stable, we recommend soliciting input on the codes from all manuscript authors. Yet, coders must ultimately be empowered to finalise the details so that they are comfortable working with the codebook across a large quantity of data.

Assigning codes to the data

After developing the codebook, coders will use it to assign codes to the remaining data. While the codebook’s overall structure should remain constant, coders might continue to add codes corresponding to any new concepts observed in the data. If new codes are added, coders should review the data they have already coded and determine whether the new codes apply. Qualitative data analysis software can be useful for editing or merging codes.

We recommend that coders periodically compare their code occurrences ( box 5 ), with more frequent check-ins if substantial disagreements occur. In the event of large discrepancies in the codes assigned, coders should revise the codebook to ensure that code descriptions are sufficiently clear and comprehensive to support coding alignment going forward. Because coding is an iterative process, the team can adjust the codebook as needed. 5 28 29

Quantitative coding in context

Researchers should generally avoid reporting code counts in thematic analysis. However, counts can be a useful proxy in maintaining alignment between coders on key concepts. 26 In practice, therefore, researchers should make sure that all coders working on the same piece of data assign the same codes with a similar pattern and that their memoing and overall assessment of the data are aligned. 37 However, the frequency of a code alone is not an indicator of its importance. It is more important that coders agree on the most salient points in the data; reviewing and discussing summary memos can be helpful here. 5

Researchers might disagree on whether or not to calculate and report inter-rater reliability. We note that quantitative tests for agreement, such as kappa statistics or intraclass correlation coefficients, can be distracting and might not provide meaningful results in qualitative analyses. Similarly, Braun and Clarke argue that expecting perfect alignment on coding is inconsistent with the goal of co-constructing meaning. 28 29 Overall consensus on codes’ salience and contributions to themes is the most important factor.

Definition of themes

Themes are meta-constructs that rise above codes and unite the dataset ( box 6 , fig 2 ). They should be clearly evident, repeated throughout the dataset, and relevant to the research questions. 38 While codes are often explicit descriptions of the content in the dataset, themes are usually more conceptual and knit the codes together. 39 Some researchers hypothesise that theme development is loosely described in the literature because qualitative researchers simply intuit themes during the analytical process. 39 In practical thematic analysis, we offer a concrete process that should make developing meaningful themes straightforward.

Themes in context

According to Braun and Clarke, a theme “captures something important about the data in relation to the research question and represents some level of patterned response or meaning within the data set.” 4 Similarly, Braun and Clarke advise against themes as domain summaries. While different approaches can draw out themes from codes, the process begins by identifying patterns. 28 35 Like Braun and Clarke and others, we recommend that researchers consider the salience of certain themes, their prevalence in the dataset, and their keyness (ie, how relevant the themes are to the overarching research questions). 4 12 34

Use of themes in practical thematic analysis

Constructing meaningful themes

After coding all the data, each coder should independently reflect on the team’s summary memos (step 1), the codebook (step 2), and the coded data itself to develop draft themes (step 3). It can be illuminating for coders to review all excerpts associated with each code, so that they derive themes directly from the data. Researchers should remain focused on the research question during this step, so that themes have a clear relation with the overall project aim. Use of qualitative analysis software will make it easy to view each segment of data tagged with each code. Themes might neatly correspond to groups of codes. Or—more likely—they will unite codes and data in unexpected ways. A whiteboard or presentation slides might be helpful to organise, craft, and revise themes. We also provide a template for coproducing themes (supplemental material 3). As with codebook justification, team members will ideally produce individual drafts of the themes that they have identified in the data. They can then discuss these with the group and reach alignment or consensus on the final themes.

The team should ensure that all themes are salient, meaning that they are: supported by the data, relevant to the study objectives, and important. Similar to codes, themes are framed as complete thoughts or sentences, not categories. While codes and themes might appear to be similar to each other, the key distinction is that the themes represent a broader concept. Table 2 shows examples of codes and their corresponding themes from a previously published project that used practical thematic analysis. 36 Identifying three to four key themes that comprise a broader overarching theme is a useful approach. Themes can also have subthemes, if appropriate. 40 41 42 43 44

Example codes with themes in practical thematic analysis 36

Thematic analysis session

After each coder has independently produced draft themes, a carefully selected subset of the manuscript team meets for a thematic analysis session ( table 3 ). The purpose of this session is to discuss and reach alignment or consensus on the final themes. We recommend a session of three to five hours, either in-person or virtually.

Example agenda of thematic analysis session

The composition of the thematic analysis session team is important, as each person’s perspectives will shape the results. This group is usually a small subset of the broader research team, with three to seven individuals. We recommend that primary and senior authors work together to include people with diverse experiences related to the research topic. They should aim for a range of personalities and professional identities, particularly those of clinicians, trainees, patients, and care partners. At a minimum, all coders and primary and senior authors should participate in the thematic analysis session.

The session begins with each coder presenting their draft themes with supporting quotes from the data. 5 Through respectful and collaborative deliberation, the group will develop a shared set of final themes.

One team member facilitates the session. A firm, confident, and consistent facilitation style with good listening skills is critical. For practical reasons, this person is not usually one of the primary coders. Hierarchies in teams cannot be entirely flattened, but acknowledging them and appointing an external facilitator can reduce their impact. The facilitator can ensure that all voices are heard. For example, they might ask for perspectives from patient partners or more junior researchers, and follow up on comments from senior researchers to say, “We have heard your perspective and it is important; we want to make sure all perspectives in the room are equally considered.” Or, “I hear [senior person] is offering [x] idea, I’d like to hear other perspectives in the room.” The role of the facilitator is critical in the thematic analysis session. The facilitator might also privately discuss with more senior researchers, such as principal investigators and senior authors, the importance of being aware of their influence over others and respecting and eliciting the perspectives of more junior researchers, such as patients, care partners, and students.

To our knowledge, this discrete thematic analysis session is a novel contribution of practical thematic analysis. It helps efficiently incorporate diverse perspectives using the session agenda and theme coproduction template (supplemental material 3) and makes the process of constructing themes transparent to the entire research team.

Writing the report

We recommend beginning the results narrative with a summary of all relevant themes emerging from the analysis, followed by a subheading for each theme. Each subsection begins with a brief description of the theme and is illustrated with relevant quotes, which are contextualised and explained. The write-up should not simply be a list, but should contain meaningful analysis and insight from the researchers, including descriptions of how different stakeholders might have experienced a particular situation differently or unexpectedly.

In addition to weaving quotes into the results narrative, quotes can be presented in a table. This strategy is a particularly helpful when submitting to clinical journals with tight word count limitations. Quote tables might also be effective in illustrating areas of agreement and disagreement across stakeholder groups, with columns representing different groups and rows representing each theme or subtheme. Quotes should include an anonymous label for each participant and any relevant characteristics, such as role or gender. The aim is to produce rich descriptions. 5 We recommend against repeating quotations across multiple themes in the report, so as to avoid confusion. The template for coproducing themes (supplemental material 3) allows documentation of quotes supporting each theme, which might also be useful during report writing.

Visual illustrations such as a thematic map or figure of the findings can help communicate themes efficiently. 4 36 42 44 If a figure is not possible, a simple list can suffice. 36 Both must clearly present the main themes with subthemes. Thematic figures can facilitate confirmation that the researchers’ interpretations reflect the study populations’ perspectives (sometimes known as member checking), because authors can invite discussions about the figure and descriptions of findings and supporting quotes. 46 This process can enhance the validity of the results. 46

In supplemental material 4, we provide additional guidance on reporting thematic analysis consistent with COREQ. 18 Commonly used in health services research, COREQ outlines a standardised list of items to be included in qualitative research reports ( box 7 ).

Reporting in context

We note that use of COREQ or any other reporting guidelines does not in itself produce high quality work and should not be used as a substitute for general methodological rigor. Rather, researchers must consider rigor throughout the entire research process. As the issue of how to conceptualise and achieve rigorous qualitative research continues to be debated, 47 48 we encourage researchers to explicitly discuss how they have looked at methodological rigor in their reports. Specifically, we point researchers to Braun and Clarke’s 2021 tool for evaluating thematic analysis manuscripts for publication (“Twenty questions to guide assessment of TA [thematic analysis] research quality”). 16

Avoiding common pitfalls

Awareness of common mistakes can help researchers avoid improper use of qualitative methods. Improper use can, for example, prevent researchers from developing meaningful themes and can risk drawing inappropriate conclusions from the data. Braun and Clarke also warn of poor quality in qualitative research, noting that “coherence and integrity of published research does not always hold.” 16

Weak themes

An important distinction between high and low quality themes is that high quality themes are descriptive and complete thoughts. As such, they often contain subjects and verbs, and can be expressed as full sentences ( table 2 ). Themes that are simply descriptive categories or topics could fail to impart meaningful knowledge beyond categorisation. 16 49 50

Researchers will often move from coding directly to writing up themes, without performing the work of theming or hosting a thematic analysis session. Skipping concerted theming often results in themes that look more like categories than unifying threads across the data.

Unfocused analysis

Because data collection for qualitative research is often semi-structured (eg, interviews, focus groups), not all data will be directly relevant to the research question at hand. To avoid unfocused analysis and a correspondingly unfocused manuscript, we recommend that all team members keep the research objective in front of them at every stage, from reading to coding to theming. During the thematic analysis session, we recommend that the research question be written on a whiteboard so that all team members can refer back to it, and so that the facilitator can ensure that conversations about themes occur in the context of this question. Consistently focusing on the research question can help to ensure that the final report directly answers it, as opposed to the many other interesting insights that might emerge during the qualitative research process. Such insights can be picked up in a secondary analysis if desired.

Inappropriate quantification

Presenting findings quantitatively (eg, “We found 18 instances of participants mentioning safety concerns about the vaccines”) is generally undesirable in practical thematic analysis reporting. 51 Descriptive terms are more appropriate (eg, “participants had substantial concerns about the vaccines,” or “several participants were concerned about this”). This descriptive presentation is critical because qualitative data might not be consistently elicited across participants, meaning that some individuals might share certain information while others do not, simply based on how conversations evolve. Additionally, qualitative research does not aim to draw inferences outside its specific sample. Emphasising numbers in thematic analysis can lead to readers incorrectly generalising the findings. Although peer reviewers unfamiliar with thematic analysis often request this type of quantification, practitioners of practical thematic analysis can confidently defend their decision to avoid it. If quantification is methodologically important, we recommend simultaneously conducting a survey or incorporating standardised interview techniques into the interview guide. 11

Neglecting group dynamics

Researchers should concertedly consider group dynamics in the research team. Particular attention should be paid to power relations and the personality of team members, which can include aspects such as who most often speaks, who defines concepts, and who resolves disagreements that might arise within the group. 52

The perspectives of patient and care partners are particularly important to cultivate. Ideally, patient partners are meaningfully embedded in studies from start to finish, not just for practical thematic analysis. 53 Meaningful engagement can build trust, which makes it easier for patient partners to ask questions, request clarification, and share their perspectives. Professional team members should actively encourage patient partners by emphasising that their expertise is critically important and valued. Noting when a patient partner might be best positioned to offer their perspective can be particularly powerful.

Insufficient time allocation

Researchers must allocate enough time to complete thematic analysis. Working with qualitative data takes time, especially because it is often not a linear process. As the strength of thematic analysis lies in its ability to make use of the rich details and complexities of the data, we recommend careful planning for the time required to read and code each document.

Estimating the necessary time can be challenging. For step 1 (reading), researchers can roughly calculate the time required based on the time needed to read and reflect on one piece of data. For step 2 (coding), the total amount of time needed can be extrapolated from the time needed to code one document during codebook development. We also recommend three to five hours for the thematic analysis session itself, although coders will need to independently develop their draft themes beforehand. Although the time required for practical thematic analysis is variable, teams should be able to estimate their own required effort with these guidelines.

Practical thematic analysis builds on the foundational work of Braun and Clarke. 4 16 We have reframed their six phase process into three condensed steps of reading, coding, and theming. While we have maintained important elements of Braun and Clarke’s reflexive thematic analysis, we believe that practical thematic analysis is conceptually simpler and easier to teach to less experienced researchers and non-researcher stakeholders. For teams with different levels of familiarity with qualitative methods, this approach presents a clear roadmap to the reading, coding, and theming of qualitative data. Our practical thematic analysis approach promotes efficient learning by doing—experiential learning. 12 29 Practical thematic analysis avoids the risk of relying on complex descriptions of methods and theory and places more emphasis on obtaining meaningful insights from those close to real world clinical environments. Although practical thematic analysis can be used to perform intensive theory based analyses, it lends itself more readily to accelerated, pragmatic approaches.

Strengths and limitations

Our approach is designed to smooth the qualitative analysis process and yield high quality themes. Yet, researchers should note that poorly performed analyses will still produce low quality results. Practical thematic analysis is a qualitative analytical approach; it does not look at study design, data collection, or other important elements of qualitative research. It also might not be the right choice for every qualitative research project. We recommend it for applied health services research questions, where diverse perspectives and simplicity might be valuable.

We also urge researchers to improve internal validity through triangulation methods, such as member checking (supplemental material 1). 46 Member checking could include soliciting input on high level themes, theme definitions, and quotations from participants. This approach might increase rigor.

Implications

We hope that by providing clear and simple instructions for practical thematic analysis, a broader range of researchers will be more inclined to use these methods. Increased transparency and familiarity with qualitative approaches can enhance researchers’ ability to both interpret qualitative studies and offer up new findings themselves. In addition, it can have usefulness in training and reporting. A major strength of this approach is to facilitate meaningful inclusion of patient and care partner perspectives, because their lived experiences can be particularly valuable in data interpretation and the resulting findings. 11 30 As clinicians are especially pressed for time, they might also appreciate a practical set of instructions that can be immediately used to leverage their insights and access to patients and clinical settings, and increase the impact of qualitative research through timely results. 8

Practical thematic analysis is a simplified approach to performing thematic analysis in health services research, a field where the experiences of patients, care partners, and clinicians are of inherent interest. We hope that it will be accessible to those individuals new to qualitative methods, including patients, care partners, clinicians, and other health services researchers. We intend to empower multidisciplinary research teams to explore unanswered questions and make new, important, and rigorous contributions to our understanding of important clinical and health systems research.

Acknowledgments

All members of the Coproduction Laboratory provided input that shaped this manuscript during laboratory meetings. We acknowledge advice from Elizabeth Carpenter-Song, an expert in qualitative methods.

Coproduction Laboratory group contributors: Stephanie C Acquilano ( http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1215-5531 ), Julie Doherty ( http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5279-6536 ), Rachel C Forcino ( http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9938-4830 ), Tina Foster ( http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6239-4031 ), Megan Holthoff, Christopher R Jacobs ( http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5324-8657 ), Lisa C Johnson ( http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7448-4931 ), Elaine T Kiriakopoulos, Kathryn Kirkland ( http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9851-926X ), Meredith A MacMartin ( http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6614-6091 ), Emily A Morgan, Eugene Nelson, Elizabeth O’Donnell, Brant Oliver ( http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7399-622X ), Danielle Schubbe ( http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9858-1805 ), Gabrielle Stevens ( http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9001-178X ), Rachael P Thomeer ( http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5974-3840 ).

Contributors: Practical thematic analysis, an approach designed for multidisciplinary health services teams new to qualitative research, was based on CHS’s experiences teaching thematic analysis to clinical teams and students. We have drawn heavily from qualitative methods literature. CHS is the guarantor of the article. CHS, AS, CvP, AMK, JRK, and JAP contributed to drafting the manuscript. AS, JG, CMM, JAP, and RWY provided feedback on their experiences using practical thematic analysis. CvP, LCL, SLB, AVC, GE, and JKL advised on qualitative methods in health services research, given extensive experience. All authors meaningfully edited the manuscript content, including AVC and RKS. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: This manuscript did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at https://www.icmje.org/disclosure-of-interest/ and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- Ziebland S ,

- ↵ A Hybrid Approach to Thematic Analysis in Qualitative Research: Using a Practical Example. 2018. https://methods.sagepub.com/case/hybrid-approach-thematic-analysis-qualitative-research-a-practical-example .

- Maguire M ,

- Vindrola-Padros C ,

- Vindrola-Padros B

- ↵ Vindrola-Padros C. Rapid Ethnographies: A Practical Guide . Cambridge University Press 2021. https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=n80HEAAAQBAJ

- Schroter S ,

- Merino JG ,

- Barbeau A ,

- ↵ Padgett DK. Qualitative and Mixed Methods in Public Health . SAGE Publications 2011. https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=LcYgAQAAQBAJ

- Scharp KM ,

- Korstjens I

- Barnett-Page E ,

- ↵ Guest G, Namey EE, Mitchell ML. Collecting Qualitative Data: A Field Manual for Applied Research . SAGE 2013. https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=-3rmWYKtloC

- Sainsbury P ,

- Emerson RM ,

- Saunders B ,

- Kingstone T ,

- Hennink MM ,

- Kaiser BN ,

- Hennink M ,

- O’Connor C ,

- ↵ Yen RW, Schubbe D, Walling L, et al. Patient engagement in the What Matters Most trial: experiences and future implications for research. Poster presented at International Shared Decision Making conference, Quebec City, Canada. July 2019.

- ↵ Got questions about Thematic Analysis? We have prepared some answers to common ones. https://www.thematicanalysis.net/faqs/ (accessed 9 Nov 2022).

- ↵ Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic Analysis. SAGE Publications. 2022. https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/thematic-analysis/book248481 .

- Kalpokas N ,

- Radivojevic I

- Campbell KA ,

- Durepos P ,

- ↵ Understanding Thematic Analysis. https://www.thematicanalysis.net/understanding-ta/ .

- Saunders CH ,

- Stevens G ,

- CONFIDENT Study Long-Term Care Partners

- MacQueen K ,

- Vaismoradi M ,

- Turunen H ,

- Schott SL ,

- Berkowitz J ,

- Carpenter-Song EA ,

- Goldwag JL ,

- Durand MA ,

- Goldwag J ,

- Saunders C ,

- Mishra MK ,

- Rodriguez HP ,

- Shortell SM ,

- Verdinelli S ,

- Scagnoli NI

- Campbell C ,

- Sparkes AC ,

- McGannon KR

- Sandelowski M ,

- Connelly LM ,

- O’Malley AJ ,

9th World Conference on Qualitative Research

The World Conference on Qualitative Research (WCQR) is an annual event that brings together researchers, world-renowned authors, and research groups from 40+ countries, sharing their experiences with qualitative methods, making the WCQR one of the most relevant platforms for discussing and disseminating the best scientific production in Qualitative Research.

The 9th World Conference on Qualitative Research (WCQR2025) will be held from 4 to 6 February 2025 at Jagiellonian University, in Kraków, Poland, and from 11 to 13 February 2025 Online.

The growing success over the years is an essential indicator of a multidisciplinary, committed, and involved community in the context of qualitative research. The WCQR encourages the submission of scientific works that focus on several fields of application in Qualitative Research, from Education to Health, Social Sciences, Engineering and Technology, among others, as well as a crosswise and holistic view, with the approach of several themes and dimensions of research..

Kraków (Poland)

4 to 6 February 2025

11 to 13 February 2025

Researchers from 40+ countries

The place for networking

Renowned keynote speakers

The best authors and researchers in the field

Diverse programme

Register now and secure your spot

Meet one of the main worldwide events dedicated to qualitative research

Exchange experiences with researchers from different areas of knowledge

INTERNATIONAL EVENT

Participants from all over the world

PUBLICATION OF WORKS

Partnership with journals of high impact factor

EVALUATION CRITERIA

Thorough review process of submitted papers

DEDICATED ORGANIZATION

Close and personalized support before, during and after the event

- Keynotes & Plenary Sessions

- Norman K. Denzin Memorial Session

- SIG in Arts-Based Research

- SIG in Autoethnography

- A Day In Spanish and Portuguese (ADISP)

- Coalition for Critical Qualitative Inquiry

- Indigenous Inquiries

- Day in Mixed Methods SIG

- New Materialisms

- SIG In Critical and Poststructural Qualitative Psychology

- Social Work Day

- Registration

- Lifetime Achievement Award

- Qualitative Book Award

- Qualitative Dissertation Award

- Past Award Winners

- Past Congresses

- Collaborating Sites

- IAQI Newsletters

- Qualitative Event Calendar

Full Panel Submission

Individual paper/poster/roundtable submission.

In order to submit, you have to create a new account every year.

For panel submissions, please have the primary presenter of each paper create a submission through the Panel Submissions site. In order to be scheduled correctly, please ensure that each submission uses the same title in the Panel Title field.

Prepare your abstract submission using the following guidelines. The more closely you follow these guidelines, the more likely your abstract will be published error-free. Click on the links for Panel or Paper/Poster/Roundtable Submission to submit your abstract. We encourage Panel submissions. Fully formed panels will receive priority in the scheduling process. The difference between Panels and Roundtables is that panelists are authors or co-authors presenting a paper, whereas roundtable participants don’t necessarily have a paper, but discuss a proposed topic.

For submission questions please consult the Submission FAQs . If you still have a question, contact us at: [email protected]

Trouble logging in?

- You are logging into the right site using the links above.

- Next, make sure you’ve created an account. Do you have two accounts? Is there a typo in your email address?

- If you need your username and password, there is a link on the homepage of the submission site that will ask the system to send them an email with this info.

- If you need further assistance, please contact us at [email protected] .

Submission and participation guidelines

- The official language of the Congress and Congress program is English. Abstracts and panel sessions in other languages, including Spanish, Portuguese, and Turkish are considered and encouraged for the Special Interest Group days.

- There are two categories of submissions: General Congress and Special Interest Groups, previously called pre-congress days (eg. SIG in Spanish and Portuguese, SIG in Social Work, SIG in Indigenous Qualitative Inquiries, etc.). Please choose one category to submit your abstract.

- Panel submissions are comprised of at least four (4) but not more than five (5) papers, each paper with full abstract and author information. Proposals with incomplete abstract/author information will not be considered. Panels are guaranteed an 75-minute slot (individual paper presentations are expected to run 12-15 minutes).

- Abstracts for panels, or individual papers, are limited to 150 words.

- Each panel requires a chair, which can be self-nominated (during the submission process) or assigned by Congress organizers.

- We welcome proposals that broadly cover both traditional and experimental approaches to and practices of qualitative research. Our Congress is committed to helping qualitative researchers from all disciplines and all parts of the world participate in an all-inclusive dialogue about the state of the art in qualitative research.

- All congress sessions take place at venues on the University of Illinois campus.

- Please follow for A Guide to Disability Resources and Services offered at the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign. Learn more.

- If you have a request for ASL interpretation services, please contact us by 15 February. Please make requests to [email protected] with “ASL Interpreter Request” in the subject line.

Instructions for Formatting Your Abstract Titles, the Abstract, and How to Submit

- Prepare your abstract submission using the following guidelines. The more closely you follow these guidelines, the more likely your abstract will be published error-free.

- Click on the links for Panel or Paper, Poster, or Roundtable Submission to submit your abstract, through the links provided above.

- Plain text.

- DO NOT cut and paste text from an e-mail into the text-block field (not following this requirement will mean data corruption).

- 150 words only – this is an absolute limit. The text box space is finite.

- No soft or hard returns.

- No bullets, hyphens, or other non-text characters.

- No footnotes or bibliography.

- Abstract titles should follow the formatting rules found in The Chicago Manual of Style. Here are some general guidelines.

- Capitalize the first, last, and all major words in between (nouns, pronouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, and some conjunctions)

- Lowercase prepositions, regardless of length (in, over, between, on, above, through)

- Lowercase the definite and indefinite articles (a, an, the)

- Lowercase conjunctions (and, or, but, for, nor)

- Hyphenated words-always capitalize the first and second word (Part-Time)

- Faculty Learning Community: Experiences with Qualitative Data Analysis Software Melissa Freeman, University of Georgia

- In Search of Mother: Defining a Mother-Centered Theory for Understanding the Mothering Practices of Poor and Working Class Black Women. Amira Millicent Davis, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

- List authors/contributors with first name, middle initial (optional), and last name (i.e., Norman K. Denzin, Jonathan Wyatt, James Salvo)

- Include affiliation for each author — department, university (i.e., Norman K. Denzin, Institute of Communications Research, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign)

- Please note that your online submission (abstract) will be used as the text for the final program and abstract e-book (Once the program is ready, all abstracts are published online in our page and downloadable).

Please prepare your abstract submission using the above guidelines. YOU MUST REGISTER IN ORDER TO APPEAR IN THE PROGRAM . Click on the links for Panel or Paper/Poster Submission to submit your abstract. We encourage Panel submissions. Fully formed panels will receive priority in the scheduling process.

International Conference on Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise

On behalf of the International Society of Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise , we are delighted to announce that our International Conference (QRSE) returns in 2024 - July 29th (pre-conference workshops), 30th, 31st & August 1st (main conference). The conference is hosted by the Centre for Qualitative Research and the Department of Health, University of Bath, UK.

Monday the 29th of July will host several qualitative workshop sessions. Details of these will be announced at a later date.

All conference announcements will be made via the website and twitter @qrse2024 @qrsesoc

The QRSE 2024 conference organising committee can be contacted at [email protected]

Please be patient regarding a response. All committee members volunteer their time to make the conference happen whilst doing a full time academic job.

CALL FOR PAPERS

Conference committee, key dates & conta ct details, fees & registration, pre-conference w orkshops, qrse edi conference gr ant, accommodati on, travelling to bath, where next.

Would yo u like to host the 2026 conference?

Please contact [email protected] and [email protected] to express an interest.

Proceedings of the 2022 3rd International Conference on Mental Health, Education and Human Development (MHEHD 2022)

Critical Review of Quantitative and Qualitative Research

There are both advantages and disadvantages involved in quantitative and qualitative research which are underpinned by divergent theories and assumptions. It is usually dependent on the nature of research to choose the appropriate research paradigm. In China’s current educational studies, researchers have the tendency to use mixed method design strategy to address research questions more holistically by combining two different data sources in a single study. So critical assessment of quantitative and qualitative research can help researchers better choose the appropriate research method in their studies.

Download article (PDF)

Cite this article

- PROSPECTIVE STUDENTS

- CURRENT STUDENTS

THE 5TH QUALITATIVE RESEARCH CONFERENCE 2022 (QRC 2022)

Qualitative Health Research Network

2024 Qualitative Health Research Network Conference

“Exploring progress: qualitative health research through crisis, disruption and emergence”.

Than you to everyone who presented, attended, sponsored, and organised the 2024 conference that took place on the 28 th and 29 th February 2024 . This was a virtual conference with a pre-conference in-person workshop day held at University College London a few weeks before (16th of February).

Watch recrordings of the conference via the 'on demand' tab (conference attendees only - available for 60 days)

Conference theme

The QHRN organises biennial international conferences to allow emerging and experienced researchers from within and outside the UCL community to present, experiment with, and learn about qualitative theory, methods, and writing.

For our sixth conference, we turned our attention to what we have learned through crisis and continued disruption, and how this has the potential to aid understanding and inform progress in the field of qualitative health research. This conference embraced the learnings that have arisen in response to ongoing significant political, social and societal disruptions and their impact on human relationships, healthcare services, as well as political and ethical based values.

By focusing on emergence as a lens to understand the challenges and uncertainty we are facing in our work, the conference theme was designed to address questions on how we creatively proceed, and how the variety of responses might align on a spectrum between success and failure. In this way we built a platform for critical reflection and discussion on the complexities that impact us as a global research community.

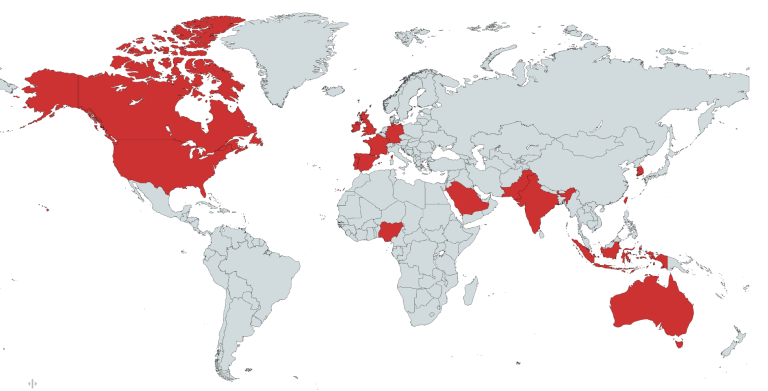

We had just under 200 people register from the conference who came from across 19 countries! See the map below for all the countries where attendees were based.

Conference keynote speakers

We hosted four brilliant keynote speakers including:

- Professor Jennie Popay (Lancaster University) who presented the talk "Critical Qualitative (Public) Health Equity Research: reviewing the present, re-imagining the future".

- Dr Laura Sheard (University of York) who discussed "Telling a story or reporting the facts: Why is descriptive analysis often favoured over interpretative analysis in health research?"

- Dr Sohail Jannesari (Kings College London and Brighton & Sussex Medical School) spoke on "Imaginative Roots: Cultivating Decolonial Methods"

- Dr Alison Thomas (Queen Mary University of London) will discussed "Navigating the tensions of researching patient experience in participatory healthcare design"

Oral presentations

Accepted abstracts were published by BMJ Open. These can be viewed via this link: UCL’s Qualitative Health Research Network Conference Abstracts 2024 .

Conference programme

Click here to view the conference programme

Pre-conference workshops

Our pre-conference workshops was held in-person at University College London on Friday 16th February 2024!

A huge thank you to everyone who organised, hosted, and attended the workshop day! It was a wonderful oppotunity to network, discuss and critically reflect on some of the key elements of qualitative health research, and get involved interactive sessions on innovative approaches.

Clich here to view the QHRN pre-conference workshop programme

Announcements:.

Check out Daniel Turner's (founder and director of Quirkos) blog based on his QHRN pre-conference workshop session!

Titled " NOT Coding Qualitative Data, and Delayed Categorisation"

“ We are proud to announce that our 2024 conference is sponsored by BMJ Open and Quirkos! :

YouTube Widget Placeholder https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7ALimgN8vv0

YouTube Widget Placeholder https://youtu.be/ojnvEC-lCuI

The QHRN are delighted to be offering bursary places to cover the costs of registration for the QHRN 2024 conference .

The deadline for applying for a bursary place (6th December 2023) has passed and all applicants have now been notified of the outcome of their application. Thank you to eveyone who registered an application.

An amazing day at the QHRN Critical Workshop (3rd of November 2023)

A huge thank you to Yasmin Garcia Sterling and Alma Ionescu for organising this year's QHRN critical workshop, and the wonderful keynote speaker Dr Stephen Roberts (UCL Lecturer in Global Health). This event was part of the lead up to our QHRN international conference ( 28th and 29th February 2024) and gave opportunity to delegates from across England to critically discuss the theme of what we have learned through crisis and continued disruption, and how this has the potential to aid understanding and inform progress in the field of qualitative health research.

Follow @UCL_QHRN

40th Qualitative Analysis Conference "Origin Stories:" Tracing the Origin of Ideas, Selves, and Communities

2024 announcements, the 40th annual qualitative analysis conference: "origin stories:" tracing the origin of ideas, selves, and communities june 26-28, 2024.

Our plenary speakers for 2024 are set! We look forward to welcoming Keynote Speaker Scott Grills (Brandon University), and Featured Speakers Dan Henhawk (University of Manitoba) and Jacqueline Low (Univeristy of New Brunswick)!

We are pleased to announce a return to the Wilfrid Laurier University - Brantford Campus - for the 2024 Qualitatives!

Please follow the links above to find the Call for Papers and instructions to submit an abstract for consideration for the conference.

Emotion impact factors and emotion management strategy among quarantined college students as close contacts during COVID-19 epidemic: a qualitative study

- Published: 16 May 2024

Cite this article

- Lin Zhang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4051-0772 2 na1 ,

- Yi Mou ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6836-5933 3 na1 &

- Chen Guo ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4291-5412 1 , 4

42 Accesses

Explore all metrics

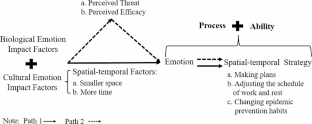

This research aimed to explore the emotion impact factors and emotion management strategies for college students quarantined as close contacts during the COVID-19 outbreak by analyzing data collected in real time (Lee et al. in DARPA information survivability conference and exposition II, DISCEX’01, vol 1, pp 89–100, IEEE, 2001), and built an emotion impact factors—emotion management strategies model. This study was undertaken among colleges in Shanghai Omicron wave in 2022, whose scale exceeded the original outbreak in Wuhan. An exploratory qualitative research design was adopted. From March to April in 2022, in-depth interviews were carried out with 54 Chinese college students with an average age of 19.91 years during the quarantine period, who were identified as close contacts by the local Center for Disease Control and were quarantined at designated quarantine centers away from campus. Data was collected during the quarantine period and was analyzed with grounded theory approach. The results revealed that there were two paths of emotion impact factors and the corresponding emotion management strategies. Participants adopted spatial-temporal, self-care, social support and control strategies to solve emotional issues separately, when they were influenced by different cultural emotion impact factors, including spatial-temporal, personal, interpersonal and informational emotion impact factors. They adopted the same four strategies as well when influenced by the biological emotion impact factors of perceived threat and perceived efficacy (see Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4 in the “Results”). These findings contribute to the framework of Hochschild’s concept of emotion management to understand how college students quarantined as close contacts adapted by combining the cultural and biological emotion impact factors, and combining the process of effort and ability aspects of emotion management during quarantine, and to expand on the concept of emotion management in the context of being in isolation for a period of time, especially in a life-stage vulnerable to emotional issues, and have implications for public health practitioners and policymakers.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Understanding loneliness in the twenty-first century: an update on correlates, risk factors, and potential solutions

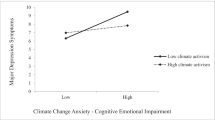

Climate change anxiety and mental health: Environmental activism as buffer

Social Media—The Emotional and Mental Roller-Coaster of Gen Z: An Empirical Study

Data availability.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Aldao, A. (2013). The future of emotion regulation research: Capturing context. Perspectives on Psychological Science , 8 (2), 155–172.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Arnett, J. J., Žukauskienė, R., & Sugimura, K. (2014). The new life stage of emerging adulthood at ages 18–29 years: Implications for mental health. The Lancet Psychiatry , 1 (7), 569–576.

Bartlett, J. D., Griffin, J., & Thomson, D. (2020). Resources for supporting children’s emotional well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Child trends, 12 .

Black, C., Roos, L. L., & Roos, N. P. (2005). From health statistics to health information systems: a new path for the twenty-first century. Health Statistics: Shaping Policy and Practice to Improve the Population’s Health , 443– 61.

Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., et al. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet , 395 (10227), 912–920.

Article Google Scholar

Buzzi, C., Tucci, M., Ciprandi, R., Brambilla, I., Caimmi, S., Ciprandi, G., & Marseglia, G. L. (2020). The psycho-social effects of COVID-19 on Italian adolescents’ attitudes and behaviors. Italian Journal of Pediatrics , 46 (1), 1–7.

Caplan, G. (1981). Mastery of stress: Psychosocial aspects. The American Journal of Psychiatry .

Chae, J. (2015). Online cancer information seeking increases cancer worry[J]. Computers in Human Behavior , 52 , 144–150.

Changeux, J. P. (1985). Neuronal man: The biology of mind . Oxford University Press.

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis . sage.

China Daily (2022). Dynamic Zero remains best option for China . 27th May,2022. Available: http://hk.ocmfa.gov.cn/eng/zydt_1/202206/t20220604_10698607.htm .

Clabaugh, A., Duque, J. F., & Fields, L. J. (2021). Academic stress and emotional well-being in United States college students following onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology , 12 , 628787.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Coan, J. A., & Maresh, E. L. (2014). Social baseline theory and the social regulation of emotion. Handbook of emotion regulation, 2 , 221–236. New York: Guilford Press.

Control, C. C. F. D. (2020). Guidelines for Investigation and Management of Close contacts of COVID-19 cases. China CDC Weekly , 2 (19), 329–331.

Feiz Arefi, M., Babaei-Pouya, A., & Poursadeqiyan, M. (2020). The health effects of quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic. Work (Reading, Mass.) , 67 (3), 523–527.

PubMed Google Scholar

Fogel, A., Nwokah, E., Dedo, J. Y., Messinger, D., Dickson, K. L., Matusov, E., & Holt, S. A. (1992). Social process theory of emotion: A dynamic systems approach. Social Development , 1 (2), 122–142.

Forte, A., Orri, M., Brandizzi, M., Iannaco, C., Venturini, P., Liberato, D., & Monducci, E. (2021). My life during the Lockdown: Emotional experiences of European adolescents during the COVID-19 Crisis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health , 18 (14), 7638.

Fu, Q., Zhang, X. Y., & Li, S. W. (2020). Strategies for risk management of medical staff’s occupational exposure to COVID-19. Chinese Journal of Nosocomiology , 30 (6), 801–805.

Google Scholar

Gaeta, M. L., Gaeta, L., & Rodriguez, M. A. D. S. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 home confinement on Mexican college students: Emotions, coping strategies, and self-regulated learning. Frontiers in Psychology , 12 , 1323.

Gheorghe, V., & Bouroș, M. (2020). Perceived social support mediates the relationship between emotional intelligence and anxiety levels among adolescents, during the pandemic. Paths of Communication in Postmodernity , 182.

Glaser Barney, G., & Strauss Anselm, L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. New York Adline De Gruyter , 17 (4), 364.

Gross, J. J. (1998). The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology , 2 (3), 271–299.

Gross, J. J. (2014). Emotion regulation: Conceptual and empirical foundations. Handbook of Emotion Regulation , 2 , 3–20.

Han, T., Ma, W. D., Gong, H., et al. (2021). Investigation and analysis of negative emotion among college students during home quarantine of COVID-19. Journal of Xi’an Jiaotong University (Medical Sciences) , 42 (1), 132–136.

Hochschild, A. R. (1979). Emotion work, feeling rules, and social structure. American Journal of Sociology , 85 (3), 551–575.

Jones, K., Mallon, S., & Schnitzler, K. (2021). A scoping review of the psychological and emotional impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and young people. Illness Crisis & Loss , 10541373211047191.

Lee, W., Stolfo, S. J., Chan, P. K., Eskin, E., Fan, W., Miller, M., & Zhang, J. (2001, June). Real time data mining-based intrusion detection. In Proceedings DARPA Information Survivability Conference and Exposition II. DISCEX’01 (Vol. 1, pp. 89–100). IEEE.

Levenson, R. W. (1999). The intrapersonal functions of emotion. Cognition & Emotion , 13 (5), 481–504.

Levenson, R. W., Soto, J., & Pole, N. (2007). Emotion, biology, and culture (pp. 780–796). Handbook of cultural psychology.

Levin, L. S., & Idler, E. L. (1983). Self-care in health. Annual Review of Public Health , 4 (1), 181–201.

Levine, L., Kay, A., & Shapiro, E. (2022). The anxiety of not knowing: Diagnosis uncertainty about COVID-19. Current Psychology , 1–8.

Li, R. (2022). Fear of COVID-19: What causes fear and how individuals cope with it. Health Communication , 37 (13), 1563–1572.

Li, Y., & Peng, J. (2020). Coping strategies as predictors of anxiety: Exploring positive experience of Chinese university in health education in COVID-19 pandemic. Creative Education , 11 (5), 735–750.

Liu, X. F. (2013). Study on the connotation and the status of emotion management. Journal of Jiangsu Normal University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition) , 39 (6), 141–146.

Liu, S., Lithopoulos, A., Zhang, C. Q., Garcia-Barrera, M. A., & Rhodes, R. E. (2021). Personality and perceived stress during COVID-19 pandemic: Testing the mediating role of perceived threat and efficacy. Personality and Individual Differences , 168 , 110351.

Ma, Z. H., Liu, Z. X., & Xia, Y. W. (2021). Research on the impacts of campus control measures on college students’ mentality and behaviors. Global Journal of Media Studies , 8 (6), 45–68.

Martinelli, N., Gil, S., Belletier, C., Chevalère, J., Dezecache, G., Huguet, P., & Droit-Volet, S. (2021). Time and emotion during lockdown and the COVID-19 epidemic: Determinants of our experience of time? Frontiers in Psychology , 11 , 616169.

Mocan, A. S., Iancu, S. S., & Baban, A. S. (2018). Association of cognitive emotional regulation strategies to depressive symptoms in type 2 diabetes patients. Romanian Journal of Internal Medicine , 56 (1), 34–40. https://doi.org/10.1515/rjim-2017-0037 .

Opitz, P. C., Gross, J. J., & Urry, H. L. (2012). Selection, optimization, and compensation in the domain of emotion regulation: Applications to adolescence, older age, and major depressive disorder. Social and Personality Psychology Compass , 6 (2), 142–155.

Ren, H., He, X., Bian, X., Shang, X., & Liu, J. (2021). The protective roles of exercise and maintenance of daily living routines for Chinese adolescents during the COVID-19 quarantine period. Journal of Adolescent Health , 68 (1), 35–42.

Roberto, A. J., Zhou, X., & Lu, A. H. (2021). The effects of perceived threat and efficacy on college students’ social distancing behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Health Communication , 26 (4), 264–271.

Rogers, A. A., Ha, T., & Ockey, S. (2021). Adolescents’ perceived socio-emotional impact of COVID-19 and implications for mental health: Results from a US-based mixed-methods study. Journal of Adolescent Health , 68 (1), 43–52.

Saarni, C. (1993). Socialization of emotion. In M. Lewis, & J. M. Haviland (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (pp. 435–446). Guilford Press.

Sakakibara, R., & Kitahara, M. (2016). The relationship between cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire (CERQ) and depression, anxiety: Meta-analysis. Shinrigaku Kenkyu: The Japanese Journal of Psychology , 87 (2), 179–185. https://doi.org/10.4992/jjpsy.87.15302 .

Samson, A. C., & Gross, J. J. (2012). Humour as emotion regulation: The differential consequences of negative versus positive humour. Cognition & Emotion , 26 (2), 375–384.

Scherer, K. R. (1994). Emotion serves to decouple stimulus and response. In P. Ekman, & R. J. Davidson (Eds.), The nature of emotion: Fundamental questions (pp. 127–130). Oxford University Press.

Segre, G., Campi, R., Scarpellini, F., Clavenna, A., Zanetti, M., Cartabia, M., & Bonati, M. (2021). Interviewing children: The impact of the COVID-19 quarantine on children’s perceived psychological distress and changes in routine. BMC Pediatrics , 21 (1), 1–11.

Shanahan, L., Steinhoff, A., Bechtiger, L., Murray, A. L., Nivette, A., Hepp, U., & Eisner, M. (2022). Emotional distress in young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence of risk and resilience from a longitudinal cohort study. Psychological Medicine , 52 (5), 824–833.

Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (2022). 26th June, 2022. Available: https://wsjkw.sh.gov.cn/xwfb/20220626/3c4144b4ac94405e9a9ceef6987eda61.html .

Southern Weekly (2022, April 2). Expert: The scale of the epidemic in Shanghai is even larger than that in Wuhan, but the severity is lower . Retrieved July 28, 2023, from http://www.infzm.com/contents/225983?source=131 .

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research . Sage.

Suls, J. E., & Wills, T. A. E. (1991). Social comparison: Contemporary theory and research . Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Thiruchselvam, R., Hajcak, G., & Gross, J. J. (2012). Looking inward: Shifting attention within working memory representations alters emotional responses. Psychological Science , 23 (12), 1461–1466.

Tian, H., Liu, Y., Li, Y., Wu, C. H., Chen, B., Kraemer, M. U., & Dye, C. (2020). An investigation of transmission control measures during the first 50 days of the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Science , 368 (6491), 638–642.

Van Maanen, J. (1979). The fact of fiction in organizational ethnography. Administrative Science Quarterly , 24 (4), 539–550.

von Moeller, J., Spengler, K. L., M., et al. (2022). Risk and protective factors of college students’ psychological well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: Emotional stability, mental health, and household resources. AERA Open , 8 (1), 1–26.