The Essays of Montaigne

First published in 1686; from the edition revised and edited in 1877 by William Carew Hazlitt

Table of Contents

- The Letters of Montaigne

- Chapter XXXIV. Means to carry on a war according to Julius Caesar.

- Chapter I. Of Profit and Honesty.

- Chapter II. Of Repentance.

- Chapter III. Of Three Commerces.

- Chapter IV. Of Diversion.

- Chapter V. Upon Some verses of Virgil.

- Chapter VI. Of Coaches.

- Chapter VII. Of the Inconvenience of Greatness.

- Chapter VIII. Of the Art of Conference.

- Chapter IX. Of Vanity.

- Chapter X. Of Managing the Will.

- Chapter XI. Of Cripples.

- Chapter XII. Of Physiognomy.

- Chapter XIII. Of Experience.

- ↑ Translator John Florio

- French essays

- Works originally in French

- Headers applying DefaultSort key

Navigation menu

- Project Gutenberg

- 73,657 free eBooks

- 33 by Michel de Montaigne

Essays of Michel de Montaigne — Complete by Michel de Montaigne

Read now or download (free!)

Similar books, about this ebook.

- Privacy policy

- About Project Gutenberg

- Terms of Use

- Contact Information

Click Here for the Full Text Search Form

Click Here to search for and view high-resolution images through the mirador viewing platform

Click Here to view paratextual page images from the Essais

Montaigne's Essays

Michel eyquem de montaigne (1533-1592), translation by john florio (1553-1625).

Note on the e-text: this Renascence Editions text was provided by Professor Emeritus Ben R. Schneider, Lawrence University, Wisconsin. It is in the public domain. "Florio's Translation of Montaigne's Essays was first published in 1603. In 'The World's Classics' the first volume was published in 1904, and reprinted in 1910 and 1924." Additional material was supplied by Risa S. Bear from the Everyman's Library edition of 1910. Content unique to this presentation is copyright © 1999 The University of Oregon. For nonprofit and educational uses only. Send comments and corrections to the Publisher, rbear[at]uoregon.edu.

THE FIRST BOOKE

THE SECOND BOOKE

THE THIRD BOOKE

trange it may seeme to some, whose seeming is mis-seeming, in one worthlesse patronage to joyne two so severallie all-worthy Ladies. But to any in the right, it would be judged wrong, to disjoyne them in ought, who were neerer in kinde, then ever in kindnesse. None dearer (dearest Ladies) I have seene, and all may say, to your Honorable husbands then you, to you then your Honorable husbands; and then to other, then eyther is to th' other. So as were I to name but the one, I should surely intend the other: but intending this Dedication to two,I could not but name both. To my last Birth, which I held masculine, (as are all mens conceipts that are thier owne, though but by their collecting; and this was to Montaigne like Bacchus, closed in, or loosed from his great Iupiters thigh) I the indulgent father invited two right Honorable Godfathers, with the One of your Noble Ladyshippes to witnesse. So to this defective edition (since all translations are reputed femalls, delivered at second hand; and I in this serve but as Vulcan, to hatchet this Minerva from that Iupiters bigge braine) I yet at least a fondling foster-father, having transported it from France to England ; put it in English clothes; taught it to talke our tongue (though many-times with a jerke of the French Iargon ) wouldset it forth to the best service I might; and to better I might not, then You that deserve the best. Yet hath it this above your other servants: it may not onely serve you two, to repeate in true English what you reade in fine French, but many thousands more, to tell them in their owne, what they would be taught in an other language. How nobly it is descended, let the father in the ninth Chapter of his third booke by letters testimoniall of the Romane Senate and Citty beare record: How rightly it is his, and his beloved, let him by his discourse in the eigh'th of his second, written to the Lady of Estissac (as if it were to you concerning your sweete heire, most motherly- affected Lady Harrington ) and by his acknowledgement in this first to all Readers give evidence, first that ir is de bonne foy, then more than that, c'est moy: how worthily qualified, embellished, furnished it is, let his faire-spoken, and fine-witted Daughter by alliance passe her verdict, which shee need not recant. Heere-hence to offer it into your service, let me for him but do and say, as he did for his other-selfe, his peerlesse paire Steven de Boetie, in the 28. of the first, and thinke hee speakes to praise-surmounting Countesse of Bedford , what hee there speakes to the Lady of Grammont, Countesse of Guissen: Since as his Maister-Poet saide,

-----mutato nomine, de te Fabula narratur: -- Hor. ser. lib. i. Sat. i. 69. Do you but change the name, Of you is saide the same:

The further that she goeth, The more in strength she groweth:

Ingrediturque solo, & caput inter nubila condit: --- 177.

She (great and good) on earth doth move, Yet veiles hir head in heaven above:

In questo stato son Donna ver vui, --- Petr. p. 1, son. 107. By you, or for you, Madame, thus am I.

Quod spiro, & placeo, si placeo, tuum est.

That I doe breath and please, if please I doe, It is your grace, such grace proceed's from you.

IOHN FLORIO.

To the Right Ho-

Norable, lucie countesse of bedford..

Relucent lustre of our English Dames, In one comprising all most priz'de of all, Whom Vertue hirs, and bounty hirs do call, Whose vertue honor, beauty love enflames, Whose value wonder writes, silence proclaimes, Though, as your owne, you know th'originall Of this, whose grace must by translation fall; Yet since this, as your owne, your Honor claimes, Yours be the honour; and if any good Be done by it, we give all thanks and praise For it to you, but who enough can give? Aye-honor'd be your Honorable Blood; Rise may your Honor, which your merites raise: Live may you long, your Honor you out-live. To the noble-minded Ladie, Anne Harrington If Mothers love exceeding others love, If Honours heart excelling all mens hearts, If bounties hand with all her beauteous parts, Poets, or Painters would to pourtray prove, Should they seeke earth below, or heav'n above, Home, Court or Countrie, forraine moulds or marts, For Maister point, or modell of their artes, For life, then here, they neede no further move: For Honour, Bountie, Love, when all is done, (Detract they not) what should they adde, or faine, But onely write, Lady A N N E H A R R I N G T O N. Her picture lost, would Nature second her, She could not, or she must make her againe. So vowes he, that himselfe doth hers averre. Il Candido. To the curteous Reader.

Al mio amato Istruttore Mr. Giovanni Florio.

Florio che fai? Vai cosi ardito di Monte? Al monte piu scoscese che Parnasso, Ardente piu che Mingibello? Plino qui muore prima, che qui monte. Se'l Pegaso non hai, che cavi'l fonte, Ritirati dal preiglioso passo. L'hai fatto pur', andand' hor' alt' hor baffo: Ti so ben dir', tu sei Bellerophonte. Tre corpi di Chimera di Montagna Hai trapassato, scosso, rinversato. Del' honorat' impres' anch' io mi glorio. Premiar' to potess' io d'or' di Spagna, Di piu che Bianco-fior' saresti ornato. Ma del' hono' ti basti, che sei Florio. Il Candido. A reply upon Maister Florio's answere to the Lady of Bedfords Invitation to this worke, in a Sonnet of like terminations. Anno. 1599. Thee to excite from Epileptic fits, Whose lethargie like frost benumming bindes Obstupefying sence with sencelesse kindes, Attend the vertue of Minervas wittes; Colde sides are spurrd, hot muthes held-in with bittes; Say No, and grow more rude, then rudest hindes; Say No, and blow more rough, then roughest windes. Who never shootes, the marke he never hitt's. To take such taske, a pleasure is no paine; Vertue and Honor (which immortalize) Not stepdame Iuno (who would wish thee slaine) Calls thee to this thrice-honorable prize; Montaigne, no cragg'd Mountaine, but faire plaine. And who would resty rest, when SHEE bids rise? Il Candido To my deere friend M. Iohn Florio, concerning his translation of Montaigne. Bookes the amasse of humors, swolne with ease, The Griefe of peace, the maladie of rest, So stuffe the world, falne into this disease, As it receives more than it can digest: And doe so evercharge, as they confound The apetite of skill with idle store: There being no end of words, nor any bound Set to conceipt, the Ocean without shore. As if man labor'd with himself to be As infinite in words, as in intents, And draws his manifold incertaintie In ev'ry figure, passion represents; That these innumerable visages, And strange shapes of opinions and discourse Shadowed in leaves, may be the witnesses Rather of our defects, then of our force. And this proud frame of our presumption, This Babel of our skill, this Towre of wit, Seemes onely chekt with the confusion Of our mistakings, that dissolveth it. And well may make us of our knowledge doubt, Seeing what uncertainties we build upon, To be as weake within booke or without; Or els that truth hath other shapes then one. But yet although we labor with this store And with the presse of writings seeme opprest, And have too many bookes, yet want we more, Feeling great dearth and scarsenesse of the best; Which cast in choiser shapes have bin produc'd, To give the best proportions to the minde To our confusion, and have introduc'd The likeliest images frailtie can finde. And wherein most the skill-desiring soule Takes her delight, the best of all delight, And where her motions evenest come to rowle About this doubtful center of the right. Which to discover this great Potentate, This Prince Montaigne (if he be not more) Hath more adventur'd of his owne estate Than ever man did of himselfe before: And hath made such bolde sallies out upon Custome, the mightie tyrant of the earth, In whose Seraglio of subjection We all seeme bred-up, from our tender birth; As I admire his powres, and out of love, Here at his gate do stand, and glad I stand So neere to him whom I do so much love, T'applaude his happie setling in our land: And safe transpassage by his studious care Who both of him and us doth merit much, Having as sumptuously, as he is rare plac'd him in the best lodging of our speach. And made him now as free, as if borne here, And as well ours as theirs, who may be proud That he is theirs, though he he be every where To have the franchise of his worth allow'd. It being the portion of a happie Pen, Not to b'invassal'd to one Monarchie, But dwells with all the better world of men Whose spirits are all of one communitie. Whom neither Ocean, Desarts, Rockes nor Sands Can keepe from th'intertraffique of the minde, But that it vents her treasure in all lands, And doth a most secure commercement finde. Wrap Excellencie up never so much, In Hierogliphicques, Ciphers, Caracters, And let her speake nver so strange a speach, Her Genius yet finds apt decipherers: And never was she borne to dye obscure, But guided by the Starres of her owne grace, Makes her owne fortune, and is aever sure In mans best hold, to hold the strongest place. And let the Critic say the worst he can, He cannot say but that Montaige yet, Yeeldes most rich pieces and extracts of man; Though in a troubled frame confus'dly set. Which yet h'is blest that he hath ever seene, And therefore as a guest in gratefulnesse, For the great good the house yeelds him within Might spare to taxe th'unapt convayances. But this breath hurts not, for both worke and frame, Whilst England English speakes, is of that store And that choyse stuffe, as that without the same The richest librarie can be but poore. And they unblest who letters do professe And have him not: whose owne fate beates their want With more sound blowes, then Alcibiades Did his pedante that did Homer want.

Give me leave

THE AUTHOR TO THE READER

EADER, loe here a well-meaning Booke. It doth at the first entrance forewarne thee, that in contriving the same I have proposed unto my selfe no other than a familiar and private end: I have no respect or consideration at all, either to thy service, or to my glory: my forces are not capable of any such desseigne. I have vowed the same to the particular commodity of my kinsfolk and friends: to the end, that losing me (which they are likely to do ere long), they may therein find some lineaments of my conditions and humours, and by that meanes reserve more whole, and more lively foster the knowledge and acquaintance they have had of me. Had my intention beene to forestal and purchase the world's opinion and favour, I would surely have adorned myselfe more quaintly, or kept a more grave and solemne march. I desire thereun to be delineated in mine own genuine, simple and ordinarie fashion, without contention, art or study; for it is myselfe I pourtray. My imperfections shall thus be read to the life, and my naturall forme discerned, so farre-forth as publike reverence hath permitted me. For if my fortune had beene to have lived among those nations which yet are said to live under the sweet liberty of Nature's first and uncorrupted lawes, I assure thee, I would most willingly have pourtrayed myselfe fully and naked. Thus, gentle Reader, myselfe am the groundworke of my booke: it is then no reason thou shouldest employ thy time about so frivolous and vaine a subject. Therefore farewell, From MONTAIGNE, The First of March, 1580.

Full Text Archive

Click it, Read it, Love it!

Essays of Montaigne, in 10 vols.

- Michel de Montaigne (author)

- Charles Cotton (translator)

This is a 10 volume collection of Montaigne’s famous essays in the 17th century English translation by Charles Cotton.

Volumes in this Set:

- Essays of Montaigne, Vol. 1

- Essays of Montaigne, Vol. 2

- Essays of Montaigne, vol. 3

- Essays of Montaigne, vol. 4

- Essays of Montaigne, vol. 5

- Essays of Montaigne, vol. 6

- Essays of Montaigne, vol. 7

- Essays of Montaigne, vol. 8

- Essays of Montaigne, vol. 9

- Life and Letters of Montaigne with Notes and Index, vol. 10

Essays of Montaigne, trans. Charles Cotton, revised by William Carew Hazlett (New York: Edwin C. Hill, 1910). In 10 vols.

The text is in the public domain.

- French literature

Related Collections:

- Banned Books

- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

The Complete Essays of Montaigne

- Michel Eyquem Montaigne

- Translated by: Donald M. Frame

- X / Twitter

Please login or register with De Gruyter to order this product.

- Language: English

- Publisher: Stanford University Press

- Copyright year: 1958

- Audience: Professional and scholarly;

- Main content: 908

- Published: June 1, 1958

- ISBN: 9780804780773

- Collections

- Support PDR

Search The Public Domain Review

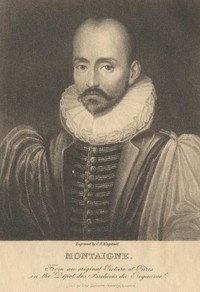

First English Edition of Michel de Montaigne’s Essays (1603)

The essayes, or, Morall, politike and millitarie discourses of Lo. Michaell de Montaigne, Knight of the noble Order of St. Michaell, and one of the gentlemen in ordinary of the French King, Henry the Third his chamber : the first booke, by Michel de Montaigne, translated by John Florio; 1603; London, Edward Blount.

In the late sixteenth century the philosopher Michel de Montaigne (1533–1592) felt drawn to express himself in energetic, playful meditations which he called “essais” — meaning “trials” or “attempts”. Thus a new literary genre was born. Though work-shy school children might have reason to hate the father of the essay, others have savoured the artistry of his creations. “This talking of oneself,” wrote Virginia Woolf, “following one’s own vagaries, giving the whole map, weight, colour, and circumference of the soul in its confusion, its variety, its imperfection — this art belonged to one man only: to Montaigne.”

At the age of thirty-eight, Montaigne retreated from the public sphere in Bordeaux to the family chateaux thirty miles inland. He carved quotes by his favourite authors into the wooden beams of his library, and poured much of the remaining twenty years of his life into his meditations. The resulting Essais (1580–88) interrogate a dizzying array of subjects: grief, friendship, coaches, drunkenness, impotence, smells, theology, education, war, animal intelligence, music, the New World, idleness, death, thumbs. Montaigne called his Essais :

A register of varied and changing occurrences, of ideas which are unresolved and, when needs be, contradictory, either because I myself have become different or because I grasp hold of different attributes or aspects of my subjects. So I may happen to contradict myself but, as Demades said, I never contradict truth.

Probably the most revolutionary thing about the Essais is their self-awareness. Other writers had interrogated themselves, such as Augustine in his Confessions (AD 397–400), but none with the acuteness or completeness of Montaigne:

If I speak diversely of myself, it is because I look diversely upon myself. . . . Shamefaced, bashful, insolent, chaste, luxurious, peevish, prattling, silent, fond, doting, labourious, nice, delicate, ingenious, slow, dull, froward, humorous, debonaire, wise, ignorant, false in words, true-speaking, both liberal, covetous, and prodigal. All these I perceive in some measure or other to be in mine, according as I stir or turn myself.

In 1603, the Italian linguist John Florio translated the Essais into poetic, wildly inventive, but nonetheless idiomatic Elizabethan prose. Now “done into English” the Essayes made a real splash in the minds of the reading public. William Shakespeare’s attention was caught by a passage in “Of the Cannibals” in which Montaigne describes the people of the New World:

[They] hath no kind of traffic, no knowledge of letters, no intelligence of numbers, no name of magistrate, nor of politic superiority; no use of service, of riches, or of poverty; no contracts, no successions, no dividences, no occupation but idle; no respect of kindred, but common; no apparel, but natural; no manuring of lands, no use of wine, corn, or metal...

Shakespeare fed this utopian description into the mouth of Gonzalo in The Tempest (1611). Daydreaming about what he would do if he were king of the island he and his friends have been shipwrecked on, Gonzalo says:

No kind of traffic Would I admit, no name of magistrate; Letters should not be known; riches, poverty, And use of service, none; contract, succession, Bourn, bound of land, tilth, vineyard, none; No use of metal, corn, or wine, or oil; No occupation, all men idle, all; And women too—but innocent and pure; No sovereignty – (II .i.148–56)

Thousands more early modern English readers were influenced by Florio’s Montaigne. In the marginal notes of their copies of the Essayes you will find agreement and disagreement, offence, and enjoyment — but never boredom. As the clergyman Abiel Borft put it in his copy: “Montaign hath the Art above all men to keep his Reader from sleeping.”

If you’d like to read Montaigne in modern English we recommend The Complete Essays translated by M.A. Screech (Penguin, 1993). As well as providing the clearest access to the more conceptually challenging passages, the edition includes an excellent introduction and footnotes revealing Montaigne’s sources. For a highly enjoyable take on his life, thought, and reception we recommend Sarah Bakewell’s How to Live: Or A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer (2010). Phillipe Desan has written a more academic biography, Montaigne: A Life (2017), which draws attention to the political player behind the solitary philosopher.

- Thought, Reflection & Theory

- Non-fiction

- 16th Century

- 17th Century

Feb 28, 2018

If You Liked This…

Get Our Newsletter

Our latest content, your inbox, every fortnight

Prints for Your Walls

Explore our selection of fine art prints, all custom made to the highest standards, framed or unframed, and shipped to your door.

Start Exploring

{{ $localize("payment.title") }}

{{ $localize('payment.no_payment') }}

Pay by Credit Card

Pay with PayPal

{{ $localize('cart.summary') }}

Click for Delivery Estimates

Sorry, we cannot ship to P.O. Boxes.

- Consulting Editors

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Notes on the Preparation of this Edition

- Buy the Book

- Navigate and Search the Archive

- Comment on a Selection

- Submit a Correction

- Suggest New Material

- Contact the Archive’s Librarian

- A Library/Press Partnership

- NEW ENTRIES

- An Interview with the Author

- For Help Concerning Suicide: Resources for Suicide Prevention

Category Archives: Montaigne, Michel de

Michel de montaigne (1533-1592) from of cannibals from a custom of the isle of cea.

Lord Michel Eyquem Montaigne was born near Bordeaux, the son of the mayor of Bordeaux, a man of unusual tolerance in an age of religious intolerance. Raised speaking only Latin until the age of six, Montaigne received the very best education; he completed a 12-year course of study at the College de Guyenne in only seven years and continued his education in the study of law at the University of Toulouse.

Montaigne served as counselor in the Bordeaux Parliament from 1557 to 1570. During this time, he was a courtier at the court of Charles the IX, from 1561 to 1563, and made the closest friendship of his life with Étienne de La Boétie, a poet who shared Montaigne’s interest in classical antiquity. Montaigne was deeply affected by the way in which La Boétie stoically accepted his death from dysentery in 1563. Montaigne and his wife, Françoise de la Chassaigne, whom he married in 1565, had six daughters, but only one of them survived childhood. Montaigne’s father died in 1568 leaving him the Chateau de Montaigne, the family estate, to which Montaigne retired in 1570 to begin work on his Essays . In 1580, Montaigne came out of seclusion to travel to Germany, Switzerland, Austria, and Italy, returning reluctantly to serve as mayor of Bordeaux for four years. Running from war and the plague, in 1586, Montaigne was forced to flee his estate; he returned shortly to the pillaged castle.

Montaigne’s lasting influence rests in his Essays , which exercised considerable influence on French and English literature; Montaigne is regarded as the inventor of the modern essay. In an unabashed, intimately personal manner previously unknown in the literature of his day, he displayed the humanism of the time, arguing that the only suitable subjects for study were mankind and the human condition, subjects that he approached by describing his own thoughts, habits, and experiences in great detail. He espoused a philosophy of toleration, stoicism in the face of suffering, and skepticism, and although he remained a professing Catholic, he challenged almost all received views of theology, philosophy, religion, science, and morality. He played a major role in the development of Christian sceptical fideism.

In the excerpt “Of Cannibals” from his Essays , Montaigne portrays the death of a Brazilian native, an enemy about to be eaten, in terms of absolute Stoic virtue. While he uses the classical Stoic sources, Montaigne implies that the attitude toward death among the Brazilian cannibals is more philosophically Stoic than that of the Europeans. This essay is supposed to be the original source of the “noble savage” idea later associated with Rousseau.

In the essay “A Custom of the Isle of Cea” (1573–74), Montaigne explores positive justifications for suicide, especially for “unendurable pain” and “fear of a worse death.” Here he juxtaposes, as he often did, many conflicting views on an issue. He mentions Pliny’s [q.v., under Pliny the Elder] belief that only three sorts of diseases license suicide, the most painful of which is bladder stone; Montaigne himself suffered considerably from stone and repeatedly sought a cure. It is noteworthy that Montaigne uses almost exclusively classical material, ignoring the enormous body of Christian theological commentary of the time. He is the first significant modern figure, together with his friend and disciple Pierre Charron (1541–1603), a sceptical Catholic priest, to question the Christian position on suicide, opening the door to a shift in thinking that would occur in the following century even as writers like John Sym [q.v.] were emphasizing the heinousness of suicide. As one contemporary scholar puts it, in arguing for a naturalistic and merely personal basis for suicide, Montaigne and Charron “opened a Pandora’s box.”

SOURCES Essays of Michel de Montaigne , ed. William Carew Hazlitt, tr. Charles Cotton (1686), Kensington 1877, “Of Cannibals,” Book the First, Chapter XXX; “A Custom of the Isle of Cea,” Book the Second, Chapter Three (Latin quotations removed). Both available online from Project Gutenberg text #3600 . Quotation and paraphrase in introductory material from Gary B. Ferngren, “The Ethics of Suicide in the Renaissance and Reformation,” in Baruch A. Brody, ed., Suicide and Euthanasia: Historical and Contemporary Themes , Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1989, pp. 161-162.

from OF CANNIBALS …I long had a man in my house that lived ten or twelve years in the New World, discovered in these latter days, and in that part of it where Villegaignon landed [Brazil, 1557], which he called Antarctic France. This discovery of so vast a country seems to be of very great consideration. I cannot be sure, that hereafter there may not be another, so many wiser men than we having been deceived in this. I am afraid our eyes are bigger than our bellies, and that we have more curiosity than capacity; for we grasp at all, but catch nothing but wind. …This man that I had was a plain ignorant fellow, and therefore the more likely to tell truth: for your better bred sort of men are much more curious in their observation, ’tis true, and discover a great deal more, but then they gloss upon it, and to give the greater weight to what they deliver and allure your belief, they cannot forbear a little to alter the story; they never represent things to you simply as they are, but rather as they appeared to them, or as they would have them appear to you, and to gain the reputation of men of judgment, and the better to induce your faith, are willing to help out the business with something more than is really true, of their own invention. Now, in this case, we should either have a man of irreproachable veracity, or so simple that he has not wherewithal to contrive, and to give a color of truth to false relations, and who can have no ends in forging an untruth. Such a one was mine; and besides, he has at divers times brought to me several seamen and merchants who at the same time went the same voyage. I shall therefore content myself with his information, without inquiring what the cosmographers say to the business. … Now, to return to my subject, I find that there is nothing barbarous and savage in this nation [Brazil], by anything that I can gather, excepting, that every one gives the title of barbarism to everything that is not in use in his own country. As, indeed, we have no other level of truth and reason, than the example and idea of the opinions and customs of the place wherein we live: there is always the perfect religion, there the perfect government, there the most exact and accomplished usage of all things. They are savages at the same rate that we say fruit are wild, which nature produces of herself and by her own ordinary progress; whereas in truth, we ought rather to call those wild, whose natures we have changed by our artifice, and diverted from the common order. In those, the genuine, most useful and natural virtues and properties are vigorous and sprightly, which we have helped to degenerate in these, by accommodating them to the pleasure of our own corrupted palate. And yet for all this our taste confesses a flavor and delicacy, excellent even to emulation of the best of ours, in several fruits wherein those countries abound without art or culture. *** …These nations then seem to me to be so far barbarous, as having received but very little form and fashion from art and human invention, and consequently to be not much remote from their original simplicity. The laws of nature, however, govern them still, not as yet much vitiated with any mixture of ours: but ’tis in such purity, that I am sometimes troubled we were not sooner acquainted with these people, and that they were not discovered in those better times, when there were men much more able to judge of them than we are. I am sorry that Lycurgus and Plato had no knowledge of them: for to my apprehension, what we now see in those nations, does not only surpass all the pictures with which the poets have adorned the golden age, and all their inventions in feigning a happy state of man, but, moreover, the fancy and even the wish and desire of philosophy itself; so native and so pure a simplicity, as we by experience see to be in them, could never enter into their imagination, nor could they ever believe that human society could have been maintained with so little artifice and human patchwork. I should tell Plato, that it is a nation wherein there is no manner of traffic, no knowledge of letters, no science of numbers, no name of magistrate or political superiority; no use of service, riches or poverty, no contracts, no successions, no dividends, no properties, no employments, but those of leisure, no respect of kindred, but common, no clothing, no agriculture, no metal, no use of corn or wine; the very words that signify lying, treachery, dissimulation, avarice, envy, detraction, pardon, never heard of… …They believe in the immortality of the soul, and that those who have merited well of the gods, are lodged in that part of heaven where the sun rises, and the accursed in the west. They have I know not what kind of priests and prophets, who very rarely present themselves to the people, having their abode in the mountains. At their arrival, there is a great feast, and solemn assembly of many villages: each house, as I have described, makes a village, and they are about a French league distant from one another. This prophet declaims to them in public, exhorting them to virtue and their duty: but all their ethics are comprised in these two articles, resolution in war, and affection to their wives. He also prophesies to them events to come, and the issues they are to expect from their enterprises, and prompts them to or diverts them from war: but let him look to’t; for if he fail in his divination, and anything happen otherwise than he has foretold, he is cut into a thousand pieces, if he be caught, and condemned for a false prophet: for that reason, if any of them has been mistaken, he is no more heard of.… They have continual war with the nations that live further within the mainland, beyond their mountains, to which they go naked, and without other arms than their bows and wooden swords, fashioned at one end like the heads of our javelins. The obstinacy of their battles is wonderful, and they never end without great effusion of blood: for as to running away, they know not what it is. Every one for a trophy brings home the head of an enemy he has killed, which he fixes over the door of his house. After having a long time treated their prisoners very well, and given them all the regales they can think of, he to whom the prisoner belongs, invites a great assembly of his friends. They being come, he ties a rope to one of the arms of the prisoner, of which, at a distance, out of his reach, he holds the one end himself, and gives to the friend he loves best the other arm to hold after the same manner; which being done, they two, in the presence of all the assembly, despatch him with their swords. After that they roast him, eat him among them, and send some chops to their absent friends. They do not do this, as some think, for nourishment, as the Scythians anciently did, but as a representation of an extreme revenge; as will appear by this: that having observed the Portuguese, who were in league with their enemies, to inflict another sort of death upon any of them they took prisoners, which was to set them up to the girdle in the earth, to shoot at the remaining part till it was stuck full of arrows, and then to hang them, they thought those people of the other world (as being men who had sown the knowledge of a great many vices among their neighbors, and who were much greater masters in all sorts of mischief than they) did not exercise this sort of revenge without a meaning, and that it must needs be more painful than theirs, they began to leave their old way, and to follow this. I am not sorry that we should here take notice of the barbarous horror of so cruel an action, but that, seeing so clearly into their faults, we should be so blind to our own. … …We may then call these people barbarous, in respect to the rules of reason: but not in respect to ourselves, who in all sorts of barbarity exceed them. Their wars are throughout noble and generous, and carry as much excuse and fair pretense, as that human malady is capable of; having with them no other foundation than the sole jealousy of valor. Their disputes are not for the conquest of new lands, for these they already possess are so fruitful by nature, as to supply them without labor or concern, with all things necessary, in such abundance that they have no need to enlarge their borders. And they are moreover, happy in this, that they only covet so much as their natural necessities require: all beyond that, is superfluous to them: men of the same age call one another generally brothers, those who are younger, children; and the old men are fathers to all. These leave to their heirs in common the full possession of goods, without any manner of division, or other title than what nature bestows upon her creatures, in bringing them into the world. If their neighbors pass over the mountains to assault them, and obtain a victory, all the victors gain by it is glory only, and the advantage of having proved themselves the better in valor and virtue: for they never meddle with the goods of the conquered, but presently return into their own country, where they have no want of anything necessary, nor of this greatest of all goods, to know happily how to enjoy their condition and to be content. And those in turn do the same; they demand of their prisoners no other ransom, than acknowledgment that they are overcome: but there is not one found in an age, who will not rather choose to die than make such a confession, or either by word or look, recede from the entire grandeur of an invincible courage. There is not a man among them who had not rather be killed and eaten, than so much as to open his mouth to entreat he may not. They use them with all liberality and freedom, to the end their lives may be so much the dearer to them; but frequently entertain them with menaces of their approaching death, of the torments they are to suffer, of the preparations making in order to it, of the mangling their limbs, and of the feast that is to be made, where their carcass is to be the only dish. All which they do, to no other end, but only to extort some gentle or submissive word from them, or to frighten them so as to make them run away, to obtain this advantage that they were terrified, and that their constancy was shaken; and indeed, if rightly taken, it is in this point only that a true victory consists. “No victory is complete, which the conquered do not admit to be so.–” [Claudius , De Sexto Consulatu Honorii] …The estimate and value of a man consist in the heart and in the will: there his true honor lies. Valor is stability, not of legs and arms, but of the courage and the soul; it does not lie in the goodness of our horse or our arms: but in our own. He that falls obstinate in his courage– “If his legs fail him, he fights on his knees.” [Seneca , De Providentia ] –he who, for any danger of imminent death, abates nothing of his assurance; who, dying, yet darts at his enemy a fierce and disdainful look, is overcome not by us, but by fortune; he is killed, not conquered; the most valiant are sometimes the most unfortunate. … But to return to my story: these prisoners are so far from discovering the least weakness, for all the terrors that can be represented to them that, on the contrary, during the two or three months they are kept, they always appear with a cheerful countenance; importune their masters to make haste to bring them to the test, defy, rail at them, and reproach them with cowardice, and the number of battles they have lost against those of their country. I have a song made by one of these prisoners, wherein he bids them “come all, and dine upon him, and welcome, for they shall withal eat their own fathers and grandfathers, whose flesh has served to feed and nourish him. These muscles,” says he, “this flesh and these veins, are your own: poor silly souls as you are, you little think that the substance of your ancestors’ limbs is here yet; notice what you eat, and you will find in it the taste of your own flesh:” in which song there is to be observed an invention that nothing relishes of the barbarian. Those that paint these people dying after this manner, represent the prisoner spitting in the faces of his executioners and making wry mouths at them. And ’tis most certain, that to the very last gasp, they never cease to brave and defy them both in word and gesture. In plain truth, these men are very savage in comparison of us; of necessity, they must either be absolutely so or else we are savages; for there is a vast difference between their manners and ours. …

from A CUSTOM OF THE ISLE OF CEA If to philosophise be, as ’tis defined, to doubt, much more to write at random and play the fool, as I do, ought to be reputed doubting, for it is for novices and freshmen to inquire and to dispute, and for the chairman to moderate and determine. My moderator is the authority of the divine will, that governs us without contradiction, and that is seated above these human and vain contestations. Philip having forcibly entered into Peloponnesus, and some one saying to Damidas that the Lacedaemonians were likely very much to suffer if they did not in time reconcile themselves to his favour: “Why, you pitiful fellow,” replied he, “what can they suffer who do not fear to die?” It being also asked of Agis, which way a man might live free? “Why,” said he, “by despising death.” These, and a thousand other sayings to the same purpose, distinctly sound of something more than the patient attending the stroke of death when it shall come; for there are several accidents in life far worse to suffer than death itself. Witness the Lacedaemonian boy taken by Antigonus, and sold for a slave, who being by his master commanded to some base employment: “Thou shalt see,” says the boy, “whom thou hast bought; it would be a shame for me to serve, being so near the reach of liberty,” and having so said, threw himself from the top of the house. Antipater severely threatening the Lacedaemonians, that he might the better incline them to acquiesce in a certain demand of his: “If thou threatenest us with more than death,” replied they, “we shall the more willingly die”; and to Philip, having written them word that he would frustrate all their enterprises: “What, wilt thou also hinder us from dying?” This is the meaning of the sentence, “That the wise man lives as long as he ought, not so long as he can; and that the most obliging present Nature has made us, and which takes from us all colour of complaint of our condition, is to have delivered into our own custody the keys of life; she has only ordered, one door into life, but a hundred thousand ways out. We may be straitened for earth to live upon, but earth sufficient to die upon can never be wanting, as Boiocalus answered the Romans.”—[Tacitus, Annal., xiii. 56.]—Why dost thou complain of this world? it detains thee not; thy own cowardice is the cause, if thou livest in pain. There needs no more to die but to will to die: “Death is everywhere: heaven has well provided for that. Any one may deprive us of life; no one can deprive us of death. To death there are a thousand avenues.” [Seneca, Theb.] Neither is it a recipe for one disease only; death is the infallible cure of all; ’tis a most assured port that is never to be feared, and very often to be sought. It comes all to one, whether a man give himself his end, or stays to receive it by some other means; whether he pays before his day, or stay till his day of payment come; from whencesoever it comes, it is still his; in what part soever the thread breaks, there’s the end of the clue. The most voluntary death is the finest. Life depends upon the pleasure of others; death upon our own. We ought not to accommodate ourselves to our own humour in anything so much as in this. Reputation is not concerned in such an enterprise; ’tis folly to be concerned by any such apprehension. Living is slavery if the liberty of dying be wanting. The ordinary method of cure is carried on at the expense of life; they torment us with caustics, incisions, and amputations of limbs; they interdict aliment and exhaust our blood; one step farther and we are cured indeed and effectually. Why is not the jugular vein as much at our disposal as the median vein? For a desperate disease a desperate cure. Servius the grammarian, being tormented with the gout, could think of no better remedy than to apply poison to his legs, to deprive them of their sense; let them be gouty at their will, so they were insensible of pain. God gives us leave enough to go when He is pleased to reduce us to such a condition that to live is far worse than to die. ‘Tis weakness to truckle under infirmities, but it’s madness to nourish them. The Stoics say, that it is living according to nature in a wise man to, take his leave of life, even in the height of prosperity, if he do it opportunely; and in a fool to prolong it, though he be miserable, provided he be not indigent of those things which they repute to be according to nature. As I do not offend the law against thieves when I embezzle my own money and cut my own purse; nor that against incendiaries when I burn my own wood; so am I not under the lash of those made against murderers for having deprived myself of my own life. Hegesias said, that as the condition of life did, so the condition of death ought to depend upon our own choice. And Diogenes meeting the philosopher Speusippus, so blown up with an inveterate dropsy that he was fain to be carried in a litter, and by him saluted with the compliment, “I wish you good health.” “No health to thee,” replied the other, “who art content to live in such a condition.” And in fact, not long after, Speusippus, weary of so languishing a state of life, found a means to die. But this does not pass without admitting a dispute: for many are of opinion that we cannot quit this garrison of the world without the express command of Him who has placed us in it; and that it appertains to God who has placed us here, not for ourselves only but for His Glory and the service of others, to dismiss us when it shall best please Him, and not for us to depart without His licence: that we are not born for ourselves only, but for our country also, the laws of which require an account from us upon the score of their own interest, and have an action of manslaughter good against us; and if these fail to take cognisance of the fact, we are punished in the other world as deserters of our duty: Thence the sad ones occupy the next abodes, who, though free from guilt, were by their own hands slain, and, hating light, sought death. [Virgil, Aeneid] There is more constancy in suffering the chain we are tied to than in breaking it, and more pregnant evidence of fortitude in Regulus than in Cato; ’tis indiscretion and impatience that push us on to these precipices: no accidents can make true virtue turn her back; she seeks and requires evils, pains, and grief, as the things by which she is nourished and supported; the menaces of tyrants, racks, and tortures serve only to animate and rouse her: As in Mount Algidus, the sturdy oak even from the axe itself derives new vigour and life. [Horace, Odes] And as another says: Father, ’tis no virtue to fear life, but to withstand great misfortunes, nor turn back from them. [Seneca, Theb.] Or as this: It is easy in adversity to despise death; but he acts more bravely, who can live wretched.” [Martial] ‘Tis cowardice, not virtue, to lie squat in a furrow, under a tomb, to evade the blows of fortune; virtue never stops nor goes out of her path, for the greatest storm that blows: Should the world’s axis crack, the ruins will but crush a fearless head. [Horace, Odes] For the most part, the flying from other inconveniences brings us to this; nay, endeavouring to evade death, we often run into its very mouth: Tell me, is it not madness, that one should die for fear of dying?” [Martial] Like those who, from fear of a precipice, throw themselves headlong into it; The fear of future ills often makes men run into extreme danger; he is truly brave who boldly dares withstand the mischiefs he apprehends, when they confront him and can be deferred. [Lucan] Death to that degree so frightens some men, that causing them to hate both life and light, they kill themselves, miserably forgetting that this same fear is the fountain of their cares.” [Lucretius] Plato, in his Laws, assigns an ignominious sepulture to him who has deprived his nearest and best friend, namely himself, of life and his destined course, being neither compelled so to do by public judgment, by any sad and inevitable accident of fortune, nor by any insupportable disgrace, but merely pushed on by cowardice and the imbecility of a timorous soul. And the opinion that makes so little of life, is ridiculous; for it is our being, ’tis all we have. Things of a nobler and more elevated being may, indeed, reproach ours; but it is against nature for us to contemn and make little account of ourselves; ’tis a disease particular to man, and not discerned in any other creatures, to hate and despise itself. And it is a vanity of the same stamp to desire to be something else than what we are; the effect of such a desire does not at all touch us, forasmuch as it is contradicted and hindered in itself. He that desires of a man to be made an angel, does nothing for himself; he would be never the better for it; for, being no more, who shall rejoice or be sensible of this benefit for him. For he to whom misery and pain are to be in the future, must himself then exist, when these ills befall him.” [Plato, Laws] Security, indolence, impassability, the privation of the evils of this life, which we pretend to purchase at the price of dying, are of no manner of advantage to us: that man evades war to very little purpose who can have no fruition of peace; and as little to the purpose does he avoid trouble who cannot enjoy repose. Amongst those of the first of these two opinions, there has been great debate, what occasions are sufficient to justify the meditation of self-murder, which they call “A reasonable exit.”—[ Diogenes Laertius, Life of Zeno.]— For though they say that men must often die for trivial causes, seeing those that detain us in life are of no very great weight, yet there is to be some limit. There are fantastic and senseless humours that have prompted not only individual men, but whole nations to destroy themselves, of which I have elsewhere given some examples; and we further read of the Milesian virgins, that by a frantic compact they hanged themselves one after another till the magistrate took order in it, enacting that the bodies of such as should be found so hanged should be drawn by the same halter stark naked through the city. When Therykion tried to persuade Cleomenes to despatch himself, by reason of the ill posture of his affairs, and, having missed a death of more honour in the battle he had lost, to accept of this the second in honour to it, and not to give the conquerors leisure to make him undergo either an ignominious death or an infamous life; Cleomenes, with a courage truly Stoic and Lacedaemonian, rejected his counsel as unmanly and mean; “that,” said he, “is a remedy that can never be wanting, but which a man is never to make use of, whilst there is an inch of hope remaining”: telling him, “that it was sometimes constancy and valour to live; that he would that even his death should be of use to his country, and would make of it an act of honour and virtue.” Therykion, notwithstanding, thought himself in the right, and did his own business; and Cleomenes afterwards did the same, but not till he had first tried the utmost malevolence of fortune. All the inconveniences in the world are not considerable enough that a man should die to evade them; and, besides, there being so many, so sudden and unexpected changes in human things, it is hard rightly to judge when we are at the end of our hope: The gladiator conquered in the lists hopes on, though the menacing spectators, turning their thumb, order him to die. [Pentadius, De Spe] All things, says an old adage, are to be hoped for by a man whilst he lives; ay, but, replies Seneca, why should this rather be always running in a man’s head that fortune can do all things for the living man, than this, that fortune has no power over him that knows how to die? Josephus, when engaged in so near and apparent danger, a whole people being violently bent against him, that there was no visible means of escape, nevertheless, being, as he himself says, in this extremity counselled by one of his friends to despatch himself, it was well for him that he yet maintained himself in hope, for fortune diverted the accident beyond all human expectation, so that he saw himself delivered without any manner of inconvenience. Whereas Brutus and Cassius, on the contrary, threw away the remains of the Roman liberty, of which they were the sole protectors, by the precipitation and temerity wherewith they killed themselves before the due time and a just occasion. Monsieur d’Anguien, at the battle of Serisolles, twice attempted to run himself through, despairing of the fortune of the day, which went indeed very untowardly on that side of the field where he was engaged, and by that precipitation was very near depriving himself of the enjoyment of so brave a victory. I have seen a hundred hares escape out of the very teeth of the greyhounds: Some have survived their executioners. [Seneca, Epistles] Length of days, and the various labour of changeful time, have brought things to a better state; fortune turning, shews a reverse face, and again restores men to prosperity. [Aeneid, xi. 425.] Pliny says there are but three sorts of diseases, to escape which a man has good title to destroy himself; the worst of which is the stone in the bladder, when the urine is suppressed. Seneca says those only which for a long time are discomposing the functions of the soul. And some there have been who, to avoid a worse death, have chosen one to their own liking. Democritus, general of the Aetolians, being brought prisoner to Rome, found means to make his escape by night: but close pursued by his keepers, rather than suffer himself to be retaken, he fell upon his own sword and died. Antinous and Theodotus, their city of Epirus being reduced by the Romans to the last extremity, gave the people counsel universally to kill themselves; but, these preferring to give themselves up to the enemy, the two chiefs went to seek the death they desired, rushing furiously upon the enemy, with intention to strike home but not to ward a blow. The Island of Gozzo being taken some years ago by the Turks, a Sicilian, who had two beautiful daughters marriageable, killed them both with his own hand, and their mother, running in to save them, to boot, which having done, sallying out of the house with a cross-bow and harquebus, with two shots he killed two of the Turks nearest to his door, and drawing his sword, charged furiously in amongst the rest, where he was suddenly enclosed and cut to pieces, by that means delivering his family and himself from slavery and dishonour. The Jewish women, after having circumcised their children, threw them and themselves down a precipice to avoid the cruelty of Antigonus. I have been told of a person of condition in one of our prisons, that his friends, being informed that he would certainly be condemned, to avoid the ignominy of such a death suborned a priest to tell him that the only means of his deliverance was to recommend himself to such a saint, under such and such vows, and to fast eight days together without taking any manner of nourishment, what weakness or faintness soever he might find in himself during the time; he followed their advice, and by that means destroyed himself before he was aware, not dreaming of death or any danger in the experiment. Scribonia advising her nephew Libo to kill himself rather than await the stroke of justice, told him that it was to do other people’s business to preserve his life to put it after into the hands of those who within three or four days would fetch him to execution, and that it was to serve his enemies to keep his blood to gratify their malice. We read in the Bible that Nicanor, the persecutor of the law of God, having sent his soldiers to seize upon the good old man Razis, surnamed in honour of his virtue the father of the Jews: the good man, seeing no other remedy, his gates burned down, and the enemies ready to seize him, choosing rather to die nobly than to fall into the hands of his wicked adversaries and suffer himself to be cruelly butchered by them, contrary to the honour of his rank and quality, stabbed himself with his own sword, but the blow, for haste, not having been given home, he ran and threw himself from the top of a wall headlong among them, who separating themselves and making room, he pitched directly upon his head; notwithstanding which, feeling yet in himself some remains of life, he renewed his courage, and starting up upon his feet all bloody and wounded as he was, and making his way through the crowd to a precipitous rock, there, through one of his wounds, drew out his bowels, which, tearing and pulling to pieces with both his hands, he threw amongst his pursuers, all the while attesting and invoking the Divine vengeance upon them for their cruelty and injustice. Of violences offered to the conscience, that against the chastity of woman is, in my opinion, most to be avoided, forasmuch as there is a certain pleasure naturally mixed with it, and for that reason the dissent therein cannot be sufficiently perfect and entire, so that the violence seems to be mixed with a little consent of the forced party. The ecclesiastical history has several examples of devout persons who have embraced death to secure them from the outrages prepared by tyrants against their religion and honour. Pelagia and Sophronia, both canonised, the first of these precipitated herself with her mother and sisters into the river to avoid being forced by some soldiers, and the last also killed herself to avoid being ravished by the Emperor Maxentius. It may, peradventure, be an honour to us in future ages, that a learned author of this present time, and a Parisian, takes a great deal of pains to persuade the ladies of our age rather to take any other course than to enter into the horrid meditation of such a despair. I am sorry he had never heard, that he might have inserted it amongst his other stories, the saying of a woman, which was told me at Toulouse, who had passed through the handling of some soldiers: “God be praised,” said she, “that once at least in my life I have had my fill without sin.” In truth, these cruelties are very unworthy the French good nature, and also, God be thanked, our air is very well purged of them since this good advice: ’tis enough that they say “no” in doing it, according to the rule of the good Marot. Un doulx nenny, avec un doulx sourire Est tant honneste.”—Marot. History is everywhere full of those who by a thousand ways have exchanged a painful and irksome life for death. Lucius Aruntius killed himself, to fly, he said, both the future and the past. Granius Silvanus and Statius Proximus, after having been pardoned by Nero, killed themselves; either disdaining to live by the favour of so wicked a man, or that they might not be troubled, at some other time, to obtain a second pardon, considering the proclivity of his nature to suspect and credit accusations against worthy men. Spargapises, son of Queen Tomyris, being a prisoner of war to Cyrus, made use of the first favour Cyrus shewed him, in commanding him to be unbound, to kill himself, having pretended to no other benefit of liberty, but only to be revenged of himself for the disgrace of being taken. Boges, governor in Eion for King Xerxes, being besieged by the Athenian army under the conduct of Cimon, refused the conditions offered, that he might safe return into Asia with all his wealth, impatient to survive the loss of a place his master had given him to keep; wherefore, having defended the city to the last extremity, nothing being left to eat, he first threw all the gold and whatever else the enemy could make booty of into the river Strymon, and then causing a great pile to be set on fire, and the throats of all the women, children, concubines, and servants to be cut, he threw their bodies into the fire, and at last leaped into it himself. Ninachetuen, an Indian lord, so soon as he heard the first whisper of the Portuguese Viceroy’s determination to dispossess him, without any apparent cause, of his command in Malacca, to transfer it to the King of Campar, he took this resolution with himself: he caused a scaffold, more long than broad, to be erected, supported by columns royally adorned with tapestry and strewed with flowers and abundance of perfumes; all which being prepared, in a robe of cloth of gold, set full of jewels of great value, he came out into the street, and mounted the steps to the scaffold, at one corner of which he had a pile lighted of aromatic wood. Everybody ran to see to what end these unusual preparations were made; when Ninachetuen, with a manly but displeased countenance, set forth how much he had obliged the Portuguese nation, and with how unspotted fidelity he had carried himself in his charge; that having so often, sword in hand, manifested in the behalf of others, that honour was much more dear to him than life, he was not to abandon the concern of it for himself: that fortune denying him all means of opposing the affront designed to be put upon him, his courage at least enjoined him to free himself from the sense of it, and not to serve for a fable to the people, nor for a triumph to men less deserving than himself; which having said he leaped into the fire. Sextilia, wife of Scaurus, and Paxaea, wife of Labeo, to encourage their husbands to avoid the dangers that pressed upon them, wherein they had no other share than conjugal affection, voluntarily sacrificed their own lives to serve them in this extreme necessity for company and example. What they did for their husbands, Cocceius Nerva did for his country, with less utility though with equal affection: this great lawyer, flourishing in health, riches, reputation, and favour with the Emperor, had no other cause to kill himself but the sole compassion of the miserable state of the Roman Republic. Nothing can be added to the beauty of the death of the wife of Fulvius, a familiar favourite of Augustus: Augustus having discovered that he had vented an important secret he had entrusted him withal, one morning that he came to make his court, received him very coldly and looked frowningly upon him. He returned home, full of, despair, where he sorrowfully told his wife that, having fallen into this misfortune, he was resolved to kill himself: to which she roundly replied, “’tis but reason you should, seeing that having so often experienced the incontinence of my tongue, you could not take warning: but let me kill myself first,” and without any more saying ran herself through the body with a sword. Vibius Virrius, despairing of the safety of his city besieged by the Romans and of their mercy, in the last deliberation of his city’s senate, after many arguments conducing to that end, concluded that the most noble means to escape fortune was by their own hands: telling them that the enemy would have them in honour, and Hannibal would be sensible how many faithful friends he had abandoned; inviting those who approved of his advice to come to a good supper he had ready at home, where after they had eaten well, they would drink together of what he had prepared; a beverage, said he, that will deliver our bodies from torments, our souls from insult, and our eyes and ears from the sense of so many hateful mischiefs, as the conquered suffer from cruel and implacable conquerors. I have, said he, taken order for fit persons to throw our bodies into a funeral pile before my door so soon as we are dead. Many enough approved this high resolution, but few imitated it; seven-and-twenty senators followed him, who, after having tried to drown the thought of this fatal determination in wine, ended the feast with the mortal mess; and embracing one another, after they had jointly deplored the misfortune of their country, some retired home to their own houses, others stayed to be burned with Vibius in his funeral pyre; and were all of them so long in dying, the vapour of the wine having prepossessed the veins, and by that means deferred the effect of poison, that some of them were within an hour of seeing the enemy inside the walls of Capua, which was taken the next morning, and of undergoing the miseries they had at so dear a rate endeavoured to avoid. Jubellius Taurea, another citizen of the same country, the Consul Fulvius returning from the shameful butchery he had made of two hundred and twenty-five senators, called him back fiercely by name, and having made him stop: “Give the word,” said he, “that somebody may dispatch me after the massacre of so many others, that thou mayest boast to have killed a much more valiant man than thyself.” Fulvius, disdaining him as a man out of his wits, and also having received letters from Rome censuring the inhumanity of his execution which tied his hands, Jubellius proceeded: “Since my country has been taken, my friends dead, and having with my own hands slain my wife and children to rescue them from the desolation of this ruin, I am denied to die the death of my fellow-citizens, let me borrow from virtue vengeance on this hated life,” and therewithal drawing a short sword he carried concealed about him, he ran it through his own bosom, falling down backward, and expiring at the consul’s feet. Alexander, laying siege to a city of the Indies, those within, finding themselves very hardly set, put on a vigorous resolution to deprive him of the pleasure of his victory, and accordingly burned themselves in general, together with their city, in despite of his humanity: a new kind of war, where the enemies sought to save them, and they to destroy themselves, doing to make themselves sure of death, all that men do to secure life. Astapa, a city of Spain, finding itself weak in walls and defence to withstand the Romans, the inhabitants made a heap of all their riches and furniture in the public place; and, having ranged upon this heap all the women and children, and piled them round with wood and other combustible matter to take sudden fire, and left fifty of their young men for the execution of that whereon they had resolved, they made a desperate sally, where for want of power to overcome, they caused themselves to be every man slain. The fifty, after having massacred every living soul throughout the whole city, and put fire to this pile, threw themselves lastly into it, finishing their generous liberty, rather after an insensible, than after a sorrowful and disgraceful manner, giving the enemy to understand, that if fortune had been so pleased, they had as well the courage to snatch from them victory as they had to frustrate and render it dreadful, and even mortal to those who, allured by the splendour of the gold melting in this flame, having approached it, a great number were there suffocated and burned, being kept from retiring by the crowd that followed after. The Abydeans, being pressed by King Philip, put on the same resolution; but, not having time, they could not put it ‘in effect. The king, who was struck with horror at the rash precipitation of this execution (the treasure and movables that they had condemned to the flames being first seized), drawing off his soldiers, granted them three days’ time to kill themselves in, that they might do it with more order and at greater ease: which time they filled with blood and slaughter beyond the utmost excess of all hostile cruelty, so that not so much as any one soul was left alive that had power to destroy itself. There are infinite examples of like popular resolutions which seem the more fierce and cruel in proportion as the effect is more universal, and yet are really less so than when singly executed; what arguments and persuasion cannot do with individual men, they can do with all, the ardour of society ravishing particular judgments. The condemned who would live to be executed in the reign of Tiberius, forfeited their goods and were denied the rites of sepulture; those who, by killing themselves, anticipated it, were interred, and had liberty to dispose of their estates by will. But men sometimes covet death out of hope of a greater good. “I desire,” says St. Paul, “to be with Christ,” and “who shall rid me of these bands?” Cleombrotus of Ambracia, having read Plato’s Pheedo, entered into so great a desire of the life to come that, without any other occasion, he threw himself into the sea. By which it appears how improperly we call this voluntary dissolution, despair, to which the eagerness of hope often inclines us, and, often, a calm and temperate desire proceeding from a mature and deliberate judgment. Jacques du Chastel, bishop of Soissons, in St. Louis’s foreign expedition, seeing the king and whole army upon the point of returning into France, leaving the affairs of religion imperfect, took a resolution rather to go into Paradise; wherefore, having taken solemn leave of his friends, he charged alone, in the sight of every one, into the enemy’s army, where he was presently cut to pieces. In a certain kingdom of the new discovered world, upon a day of solemn procession, when the idol they adore is drawn about in public upon a chariot of marvellous greatness; besides that many are then seen cutting off pieces of their flesh to offer to him, there are a number of others who prostrate themselves upon the place, causing themselves to be crushed and broken to pieces under the weighty wheels, to obtain the veneration of sanctity after death, which is accordingly paid them. The death of the bishop, sword in hand, has more of magnanimity in it, and less of sentiment, the ardour of combat taking away part of the latter. There are some governments who have taken upon them to regulate the justice and opportunity of voluntary death. In former times there was kept in our city of Marseilles a poison prepared out of hemlock, at the public charge, for those who had a mind to hasten their end, having first, before the six hundred, who were their senate, given account of the reasons and motives of their design, and it was not otherwise lawful, than by leave from the magistrate and upon just occasion to do violence to themselves.—[Valerius Maximus, ii. 6, 7.]—The same law was also in use in other places. Sextus Pompeius, in his expedition into Asia, touched at the isle of Cea in Negropont: it happened whilst he was there, as we have it from one that was with him, that a woman of great quality, having given an account to her citizens why she was resolved to put an end to her life, invited Pompeius to her death, to render it the more honourable, an invitation that he accepted; and having long tried in vain by the power of his eloquence, which was very great, and persuasion, to divert her from that design, he acquiesced in the end in her own will. She had passed the age of four score and ten in a very happy state, both of body and mind; being then laid upon her bed, better dressed than ordinary and leaning upon her elbow, “The gods,” said she, “O Sextus Pompeius, and rather those I leave than those I go to seek, reward thee, for that thou hast not disdained to be both the counsellor of my life and the witness of my death. For my part, having always experienced the smiles of fortune, for fear lest the desire of living too long may make me see a contrary face, I am going, by a happy end, to dismiss the remains of my soul, leaving behind two daughters of my body and a legion of nephews”; which having said, with some exhortations to her family to live in peace, she divided amongst them her goods, and recommending her domestic gods to her eldest daughter, she boldly took the bowl that contained the poison, and having made her vows and prayers to Mercury to conduct her to some happy abode in the other world, she roundly swallowed the mortal poison. This being done, she entertained the company with the progress of its operation, and how the cold by degrees seized the several parts of her body one after another, till having in the end told them it began to seize upon her heart and bowels, she called her daughters to do the last office and close her eyes. Pliny tells us of a certain Hyperborean nation where, by reason of the sweet temperature of the air, lives rarely ended but by the voluntary surrender of the inhabitants, who, being weary of and satiated with living, had the custom, at a very old age, after having made good cheer, to precipitate themselves into the sea from the top of a certain rock, assigned for that service. Pain and the fear of a worse death seem to me the most excusable incitements.

Leave a Comment

Filed under Cowardice, Courage, Bravery, Fear , Europe , Honor and Disgrace , Mental Illness: depression, despair, insanity, delusion , Montaigne, Michel de , Selections , Slavery , Stoicism , The Early Modern Period

Search the Archive

Browse the archive by author, source, era, region, or tradition.

- Abu'l Fazl ibn Mubarak

- Adams, John

- Adler, Alfred

- African Traditional Sub-Saharan Cultures

- al-Ghazali, Abu-Hamid Muhammad

- al-Qirqisani, Ya'qub

- al-Tawhidi, Abu Hayyan

- Angela of Foligno

- Aquinas, Thomas

- Arctic Indigenous Cultures

- Babylonian Talmud

- Barrington, Mary Rose

- Beccaria, Cesare

- Bentham, Jeremy

- Bhagavad-Gita

- Blackstone, William

- Bonhoeffer, Dietrich

- Bracton, Henry de

- Burton, Robert

- Callahan, Daniel

- Calvin, John

- Camus, Albert

- Central and South American Indigenous Cultures

- Chikamatsu Monzaemon

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius

- Clement of Alexandria

- Daidoji Yuzan

- De Quincey, Thomas

- Dharmashastra

- Donne, John

- Dostoevsky, Fyodor

- Durkheim, Emile

- Egyptian Didactic Tale

- Equiano, Olaudah

- Esquirol, Jean-Etienne-Dominique

- Fichte, Johann Gottlieb

- Fleming, Caleb

- Freud, Sigmund

- Gandhi, Mohandas K.

- Genesis Rabbah

- Gildon, Charles

- Gilman, Charlotte Perkins

- Godwin, William

- Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von

- Hanh, Thich Nhat

- Hartmann, Eduard von

- Hebrew Bible

- Hegel, George Wilhelm Friedrich

- Hey, Richard

- Hindu Widow, anonymous

- Hippocrates

- Hobbes, Thomas

- Holbach, Paul-Henri Thiry Baron d'

- Holmes, John Haynes

- Huang Liuhong

- Hume, David

- Ibn Batutta

- Ibn Fadlan, Ahmad

- Ignatius of Antioch

- Ingersoll, Robert

- Jain Tradition

- James, William

- Japanese Naval Special Attack Force

- Jefferson, Thomas

- Jung, Carl Gustav

- Justin Martyr

- Kant, Immanuel

- Landsberg, Paul-Louis

- Leopardi, Giacomo

- Locke, John

- Lotus Sutra

- Luria, Solomon ben Jeheiel

- Luther, Martin

- Margolioth, Ephraim Zalman

- Mather, Cotton

- Mather, Increase

- Maximus, Valerius

- Milarepa, Jetsun

- Milinda, King

- Mill, John Stuart

- Mitford, A. B., Lord Redesdale

- Montaigne, Michel de

- Montesquieu

- More, Thomas

- Mutahhari, Murtaza

- New Testament

- Nietzsche, Friedrich

- Nightingale, Florence

- Norse Sagas

- North American Indigenous Cultures

- Oceania Indigenous Cultures

- Pepys, Samuel

- Pliny the Elder

- Pliny the Younger

- Pufendorf, Samuel von

- Rousseau, Jean-Jacques

- Roy, Rammohun

- Schopenhauer, Arthur

- Spinoza, Baruch

- Stael-Holstein, Anne-Louise-Germain

- Tillich, Paul

- Valerius Maximus

- Vitoria, Francisco de

- Watts, Isaac

- Wesley, John

- Windt, Peter Y.

- Winslow, Forbes

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig

- Woolf, Virginia

- Zygielbojm, Szmul

- Ancient History

- Middle Ages

- The Early Modern Period

- The Modern Era

- Middle East

- Christianity

- Confucianism

- Arctic Cultures

- Central and South American Native Cultures

- North American Native Cultures

- Oceanic Cultures

- Protestantism

- Cowardice, Courage, Bravery, Fear

- Existentialism

- Honor and Disgrace

- Illness and Old Age

- Mass Suicide

- Mental Illness: depression, despair, insanity, delusion

- Military Defeat, Success, Strategy

- Physician Assisted Suicide

- Sexual Issues

- Societal Organizations

- Value of Life

- Search for:

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Bookreader Item Preview

Share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

10 Favorites

Better World Books

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by Lotu Tii on July 24, 2015

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

University Libraries

Need to know, life in the sick room: essays | challenging gender norms for women | book of the month from the john martin rare book room.

MARTINEAU, HARRIETT (1802-1876). Life in the sick-room: Essays . Printed in Boston by L.C. Bowles and W. Crosby, 1844. 20 cm tall.

Martineau was born in 1802 into a progressive Unitarian family in Norwich. Despite the societal expectations that confined her to domestic roles, Harriet’s intellect and determination were undeniable. In 1823, she challenged gender norms by anonymously publishing On female education , advocating for women’s rights to education and intellectual pursuits.