Berkley Center

Patrick Fagan

This individual is not a direct affiliate of the Berkley Center. They have contributed to one or more of our events, publications, or projects. Please contact the individual at their home institution.

{{ item.media_date }}

{{ item.name }}

Sorry, we could not find any results with the search parameter provided.

- Allan C. Carlson

- Brian S. Brown

- Nicole M. King

- Bryce J. Christensen

- Patrick R. Fagan

- William C. Duncan

- Anatoly Antonov

- Maria Sophia Aguirre

- Edmund Adamus

- Rafael Hurtado

- Phillip J. Longman

- Jennifer Roback Morse

- Federico A. Nazar

- Giovanna Rossi

- Donald Paul Sullins

- David van Gend

- Lynn D. Wardle

- Avtandil Sulaberidze

- Lazslo Mark

- Current Issue

- #1 Winter 2021

- #1 Spring-Summer 2020

- #2 Fall-Winter 2020

- #1 Spring-Summer 2019

- #1 Spring-Summer 2018

- #3 Fall-Winter 2018

- #1 Winter 2017

- #2 Spring 2017

- #3 Fall-Winter 2017

- #1 Winter 2016

- #2 Spring 2016

- #3 Fall 2016

- #4 Winter 2016

- #1 Winter 2015

- #2 Spring 2015

- #3 Summer 2015

- #4 Fall 2015

- #1 Winter 2014

- #1 Winter 2013

- #2 Spring 2013

- #3 Summer 2013

- #4 Fall 2013

- #1 Spring 2012

- #2 Summer 2012

- #3 Fall 2012

- #1 Winter 2011

- #2 Spring 2011

- #3 Summer 2011

- #1 Winter 2010

- #2 Spring 2010

- #3 Summer 2010

- #4 Fall 2010

- #1 Fall 2009

- Monthly IOF Membership

- Annual IOF Membership

Patrick F. Fagan

Editorial Board of Advisors

Patrick F. Fagan, PhD, is Senior Fellow and Director of the Marriage and Religion Research Institute (MARRI), which examines the relationships among family, marriage, religion, community, and America’s social problems, as illustrated in the social science data. A native of Ireland, Dr. Fagan earned his Bachelor of Social Science degree with a double major in sociology and social administration, and a professional graduate degree in psychology (Dip. Psych.) as well as a PhD from University College Dublin.

In 1984, Dr. Fagan moved from the clinical world into the public policy arena, to work on family issues at the Free Congress Foundation. After that, he worked for Senator Dan Coats of Indiana, then was appointed Deputy Assistant Secretary for Family and Community Policy at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services by President George H.W. Bush, before spending the next 13 years at the Heritage Foundation, where he was a senior fellow.

View all articles by this author

The Gift That Christian Marriage is to Western Civilization

Dr. Pat Fagan, the Director of the Marriage And Religion Research Institute, explained how, from a sociological viewpoint, the married intact heterosexual family that worships God weekly has the most positive effect on children and society.

He encouraged the students to live chaste, virtuous, and loving lives. Like the early Christians who lived amongst dark pagan times, the witness of strong loving families will save our culture, he told them.

At the Family Research Council (FRC), Dr. Pat Fagan directs the work of the Marriage And Religion Research Institute (MARRI), a branch of the Council that focuses on studying the effects of the relationship between marriage and religion on society. Fagan has worked for the Free Congress Foundation, assisted Indiana Senator Dan Coats, served as Deputy Assistant Secretary for Family and Community Policy at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services under George H. W. Bush, and was a senior fellow at The Heritage Foundation for thirteen years before joining the FRC.

Recently Added

- Tolkien’s Faith and the Foundations of Middle-earth

- St. Thomas Aquinas: Angelic Teacher

- St. Thomas on Why Freedom and Truth Go Together

- St. Thomas and the Perennial Importance of Virtue

Stand For The Family Conference

The family is the answer, patrick f. fagan, phd.

Patrick F. Fagan, PhD, is Senior Fellow and Director of the Marriage and Religion Research Institute (MARRI), which examines the relationships among family, marriage, religion, community, and America’s social problems, as illustrated in the social science data. A native of Ireland, Dr. Fagan earned his Bachelor of Social Science degree with a double major in sociology and social administration, and a professional graduate degree in psychology (Dip. Psych.) as well as a PhD from University College Dublin.

In 1984, Dr. Fagan moved from the clinical world into the public policy arena, to work on family issues at the Free Congress Foundation. After that, he worked for Senator Dan Coats of Indiana, then was appointed Deputy Assistant Secretary for Family and Community Policy at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services by President George H.W. Bush, before spending the next 13 years at the Heritage Foundation, where he was a senior fellow.

Marriage and Religion Research Institute

Directed by Patrick Fagan, MARRIpedia is a joint project of MARRI ( Marriage and Religion Research Institute ) and IOF, and offers a powerful online encyclopedia on matters related to family, religion, education, government, and economy. It is available online here or by topic via the links below.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

The Benefits from Marriage and Religion in the United States: A Comparative Analysis

America is a religious nation. The vast majority of Americans, when asked, profess a belief in God and affirm that religion is at least “fairly important” in their lives ( Myers 2000 : 285); about 60 percent of the population report membership in a religious organization and 45 percent state that they attend religious services at least monthly ( Sherkat and Ellison 1999 ). Most American adults are currently married and almost all will marry at some time in their lives. About two-thirds of children live with their married (biological or adoptive) parents ( U.S. Census Bureau 2001 ). And marriage and a happy family life are almost universal goals for young adults.

This commentary presents a socioeconomic and demographic view of the research literature on the benefits of marriage and religious participation in the United States. We compare religion and marriage as social institutions, both clearly on everyone’s short list of “most important institutions.” Marriage is an either–or status. But marital unions differ in a multitude of ways, including the characteristics, such as education, earnings, religion, and cultural background, of each of the partners, and the homogamy of their match on these characteristics. Similarly, religion has multiple aspects. These include religious affiliation, a particular set of theological beliefs and practices, and religiosity. Religiosity may be manifested in various levels and forms of religious participation (attendance at religious services within a congregation, family observance, individual devotion) and in terms of the salience of religion, that is, the importance of religious beliefs as a guide for one’s life. Our focus here is on broad comparisons between marriage (being married versus not) and religiosity (having some involvement in religious activities versus not). We argue that both marriage and religiosity generally have far-reaching, positive effects; that they influence similar domains of life; and that there are important parallels in the pathways through which each achieves these outcomes. Where applicable, we refer to other dimensions of marriage and religion, including the quality of the marital relationship and the type of religious affiliation.

We begin with a comparison of the effects associated with marriage and involvement in religious activities, based on a literature review, followed by a comparison of the major channels through which each operates. We then discuss qualifications and important exceptions to the general conclusion that marriage and religious involvement have beneficial effects. We conclude with a consideration of the intersection between marriage and religion and suggestions for future research.

The effects of marriage and religious involvement

Marriage and religion influence various dimensions of life, including physical health and longevity, mental health and happiness, economic well-being, and the raising of children. Recent research has also examined connections to sex and domestic violence.

Physical health and longevity

One of the strongest, most consistent benefits of marriage is better physical health and its consequence, longer life. Married people are less likely than unmarried people to suffer from long-term illness or disability ( Murphy et al. 1997 ), and they have better survival rates for some illnesses ( Goodwin et al. 1987 ). They have fewer physical problems and a lower risk of death from various causes, especially those with a behavioral component; the health benefits are generally larger for men ( Ross et al. 1990 ). A longitudinal analysis based on data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, a large national sample, documents a significantly lower mortality rate for married individuals ( Lillard and Waite 1995 ). For example, simulations based on this research show that, other factors held constant, nine out of ten married women alive at age 48 would still be alive at age 65; by contrast, eight out of ten never-married women would survive to age 65. The corresponding comparison for men reveals a more pronounced difference: nine out of ten for the married group versus only six out of ten for those who were never married ( Waite and Gallagher 2000 ).

Similarly, although there are exceptions and the matter remains controversial ( Sloan et al. 1999 ), a growing body of research documents an association between religious involvement and better outcomes on a variety of physical health measures, including problems related to heart disease, stroke, hypertension, cancer, gastrointestinal disease, as well as overall health status and life expectancy. This research also points to differences by religious affiliation, with members of stricter denominations displaying an advantage ( Levin 1994 ). Many of the early studies in this literature suffer from methodological shortcomings, including small, unrepresentative samples, lack of adequate statistical controls, and a cross-sectional design that confounds the direction of causality. Yet the conclusion of a generally positive effect of religious involvement on physical health and longevity also emerges from a new generation of studies that have addressed many of these methodological problems ( Ellison and Levin 1998 ). In one of the most rigorous analyses to date, Hummer et al. (1999) use longitudinal data from a nationwide survey, the 1987 Cancer Risk Factor Supplement–Epidemiology Study, linked to the Multiple Cause of Death file. Their results show that the gap in life expectancy at age 20 between those who attend religious services more than once a week and those who never attend is more than seven years—comparable to the male–female and white–black differentials in the United States. Additional multivariate analyses of these data reveal a strong association between religious participation and the risk of death, holding constant socioeconomic and demographic variables, as well as initial health status. Other recent longitudinal studies also report a protective effect of religious involvement against disability among the elderly ( Idler and Kasl 1992 ), as well as a positive influence on self-rated health ( Musick 1996 ) and longevity ( Strawbridge et al. 1997 ).

To the extent that marriage and religious involvement are selective of people with unobserved characteristics that are conducive to better health, their causal effects on health and longevity would be smaller than suggested by some of the estimates in this literature.

Mental health and happiness

Recent studies based on longitudinal data have found that getting married (and staying married to the same person) is associated with better mental health outcomes. Horwitz et al. (1996) , Marks and Lambert (1998) , and Simon (2002) present evidence of improvements in emotional well-being following marriage, and declines following the end of a union. Marks and Lambert (1998) report that marital gain affects men and women in the same way, but marital loss is generally more depressing for women. Analyses that control for the selection of the psychologically healthy into marriage, and also include a wider range of measures of mental well-being, find that although there are differences by sex in the types of emotional responses to marital transitions, the psychological benefits associated with marriage apply equally to men and women ( Horwitz et al. 1996 ; Simon 2002 ).

Marriage is also associated with greater overall happiness. Analysis of data from the General Social Surveys of 1972–96 shows that, other factors held constant, the likelihood that a respondent would report being happy with life in general is substantially higher among those who are currently married than among those who have never been married or have been previously married; the magnitude of the gap has remained fairly stable over the past 35 years and is similar for men and women ( Waite 2000 ).

The connection between religion and mental health has been the subject of much controversy over the years, and many psychologists and psychiatrists remain skeptical, in part because most of the research has been based on cross-sectional analyses of small samples. The studies to date are suggestive of an association between religious involvement and better mental health outcomes, including greater self-esteem, better adaptation to bereavement, a lower incidence of depression and anxiety, a lower likelihood of alcohol and drug abuse, and greater life satisfaction and happiness in general ( Koenig et al. 2001 ). Recent longitudinal analyses of subgroups of the population provide additional evidence in support of this relationship ( Zuckerman et al. 1984 ; Levin et al. 1996 ).

Economic well-being

A large body of literature documents that married men earn higher wages than their single counterparts. This differential, known as the “marriage premium,” is sizable. A rigorous and thorough statistical analysis by Korenman and Neumark (1991) reports that married white men in America earn 11 percent more than their never-married counterparts, controlling for all the standard human capital variables. Between 50 and 80 percent of the effect remains, depending on the specification, after correcting for selectivity into marriage based on fixed unobservable characteristics. Other research shows that married people have higher family income than the nonmarried, with the gap between the family income of married and single women being wider than that between married and single men ( Hahn 1993 ). In addition, married people on average have higher levels of wealth and assets ( Lupton and Smith 2003 ). The magnitude of the difference depends on the precise measure used, but in all cases is far more than twice that of other household types, suggesting that this result is not merely due to the aggregation of two persons’ wealth.

To the best of our knowledge, the effects of religious involvement on earnings and wealth have not been systematically analyzed. However, as we discuss below, an emerging literature shows a positive effect of religiosity on educational attainment, a key determinant of success in the labor market. These studies suggest a potentially important link between religious involvement during childhood and adolescence and subsequent economic well-being as an adult. Preliminary results from a new line of inquiry at the macro level are consistent with this hypothesis. Using a cross-country panel that includes information on religious and economic variables, Barro and McLeary (2002) find that enhanced religious beliefs affect economic growth positively, although growth responds negatively to increased church attendance. The authors interpret their findings as reflecting a positive association between “productivity” in the religion sector and macroeconomic performance. 1

Children raised by their own married parents do better, on average, across a range of outcomes than children who grow up in other living arrangements. There is evidence that the former are less likely to die as infants ( Bennett et al. 1994 ) and have better health during childhood ( Angel and Worobey 1988 ) and even in old age ( Tucker et al. 1997 ). They are less likely to drop out of high school, they complete more years of schooling, they are less likely to be idle as young adults, and they are less likely to have a child as an unmarried teenager ( McLanahan and Sandefur 1994 ).

Children who grow up in intact two-parent families also tend to have better mental health than their counterparts who have experienced a parental divorce. Using 17-year longitudinal data from two generations, Amato and Sobolewski (2001) find that the weaker parent–child bonds that result from marital discord mediate most of the association between divorce and the subsequent mental health outcomes of children. Cherlin et al. (1998) find that children whose parents would later divorce already showed evidence of more emotional problems prior to the divorce, suggesting that marriage dissolution tends to occur in families that are troubled to begin with. However, the authors also find that the gap continues to widen following the divorce, suggestive of a causal effect of family breakup on mental health. Summing up his assessment of the studies in this field, Cherlin (1999) concludes that growing up in a nonintact family can be associated with short- and long-term problems, partly attributable to the effects of family structure on the child’s mental health, and partly attributable to inherited characteristics and their interaction with the environment.

Several studies have documented an association between religion and children’s well-being. Recent research on differences in parenting styles by religious affiliation reveals that conservative Protestants display distinctive patterns: they place a greater emphasis on obedience and tend to view corporal punishment as an acceptable form of child discipline; at the same time, they are more likely to avoid yelling at children and are more prone to frequent praising and warm displays of affection ( Bartowski et al. 2000 ). As to other dimensions of religion, Pearce and Axinn (1998) find that family religious involvement promotes stronger ties among family members and has a positive impact on mothers’ and children’s reports of the quality of their relationship.

A number of studies document the effects of children’s own religious participation, showing that young people who grow up having some religious involvement tend to display better outcomes in a range of areas. Such involvement has been linked to a lower probability of substance abuse and juvenile delinquency ( Donahue and Benson 1995 ), a lower incidence of depression among some groups ( Harker 2001 ), delayed sexual debut ( Bearman and Bruckner 2001 ), more positive attitudes toward marriage and having children, and more negative attitudes toward unmarried sex and premarital childbearing ( Marchena and Waite 2001 ).

Religious participation has also been associated with better educational outcomes. Freeman (1986) finds a positive effect of churchgoing on school attendance in a sample of inner-city black youth. Regnerus (2000) reports that participation in religious activities is related to better test scores and heightened educational expectations among tenth-grade public school students. In the most comprehensive study to date, using data on adolescents from the National Education Longitudinal Study of 1988, Muller and Ellison (2001) find positive effects of various measures of religious involvement on the students’ locus of control (a measure of self-concept), educational expectations, time spent on homework, advanced mathematics credits earned, and the probability of obtaining a high school diploma. Other research documents differences in educational attainment by religious affiliation ( Chiswick, B. 1988 ; Darnell and Sherkat 1997 ; Lehrer 1999 ; Sherkat and Darnell 1999 ) and suggests that the effects of religious participation on secular achievements may vary across denominations ( Chiswick, C. 1999 ; Lehrer 2003a ).

Studies of the influence of religiosity on schooling have raised the possibility that the estimated coefficients may overstate the positive causal effect of religious involvement on educational outcomes. This would be the case if religiosity is correlated with unobserved factors that encourage good behaviors in general: for example, the religiously more observant parents, who encourage their children to attend services as well, are also supportive of activities that are conducive to success in the secular arena. Freeman (1986) has emphasized this type of bias.

Biases operating in the opposite direction have also been identified ( Lehrer 2003a ). Although this issue has not been studied systematically, there is some evidence that religious participation is especially beneficial for those who are more vulnerable, for reasons that might include poor health, unfavorable family circumstances, and adverse economic conditions ( Hummer et al. 2002 ). To the extent that those who are vulnerable respond by embracing religion as a coping mechanism, the more religious homes would disproportionately have unobserved characteristics that affect educational outcomes adversely. If so, the estimated coefficients would understate the true effect of religiosity on educational attainment. 2

Little attention has been given to the question of how marriage is related to the chances that people will have active, satisfying sex lives. Cross-tabulations based on data from the 1992 National Health and Social Life Survey show that levels of emotional and physical satisfaction with sex are highest for married people and lowest for noncohabiting singles, with cohabitors falling in between ( Laumann et al. 1994 ). Additional evidence for the importance of commitment as a determinant of sexual satisfaction is provided by more recent multivariate analyses of these data ( Waite and Joyner 2001 ). To date, these relationships have not been quantified using longitudinal data.

Our knowledge about the relationship between religion and sex is also limited. Cross-tabulations by religious denomination show that those with no affiliation (i.e., no involvement in religious activities) are least likely to report being extremely satisfied with sex either physically or emotionally ( Laumann et al. 1994 ). Waite and Joyner (2001) find that emotional satisfaction and physical pleasure related to sex are higher for frequent attenders of religious services, holding other characteristics of the individual constant. Along similar lines, Greeley (1991) reports that couples who pray together say they have more “ecstasy” in their sex lives; he also finds that religious imagery and devotion is positively associated with sexual satisfaction. The small amount of evidence available is only suggestive of a connection between religious participation and the quality of people’s sex lives.

Domestic violence

Using data from the 1987–88 National Surveys of Families and Households, Stets (1991) finds a large difference between married people and cohabitors in the prevalence of domestic violence: 14 percent of people who have cohabiting arrangements say that they or their spouse hit, shoved, or threw things at their partner during the past year, compared to 5 percent of those who are formally married. The difference declines when age, education, and race are held constant. Additional analyses of these data show that engaged cohabiting couples display lower levels of physical violence than uncommitted cohabitors ( Waite 2000 ).

Ellison et al. (1999) explore the relationship between religion and domestic violence in America, comparing reports of abuse for men and women by religious denomination, religious participation, and religious homogamy. They find that the likelihood of violence by males increases when the male is substantially more conservative (in beliefs about the inerrancy and authority of the Bible) than his female partner. Their results also show that the likelihood of reporting violence is lower for those who attend religious services more frequently. Additional confirmation for the hypothesis that religious participation is inversely associated with the perpetration of domestic violence is provided by a more recent analysis that uses information not only on self-reported domestic violence but also on abuse reported by the partner ( Ellison and Anderson 2001 ).

As Ellison et al. (1999) note, it seems likely that part of the measured relationship between religiosity and domestic violence is due to selectivity: the more religious may well be disproportionately less prone to act violently; the same argument applies to the relationship between marriage and domestic violence.

Pathways of causality

Developing themes proposed by Durkheim ([1897]1951) , we argue that both marriage and religion lead to positive outcomes by providing social support and integration and by encouraging healthy behaviors and lifestyles. In addition, there is a mechanism that is unique to marriage, namely, the economic gains that result when two people make a commitment to become lifetime partners. There is also a pathway that is unique to religion: the positive emotions and spiritual richness that can come from personal faith and religious observance. In each case, although the various channels we discuss are conceptually distinct, they are not mutually exclusive.

Social integration and support

The argument for benefits from marriage stemming from its integrative influence runs as follows. Marriage implies love, intimacy, and friendship. The social integration and support it thus provides is a key channel through which it leads to improved mental and physical health. Being married means having someone who can provide emotional support on a regular basis, thereby decreasing depression, anxiety, and other psychological problems, and improving overall mental health. In turn, better emotional well-being contributes to enhanced physical wellness. Support from the spouse can also improve physical health directly, by aiding early detection and treatment and by promoting speedier recovery from illness ( Ross et al. 1990 ). From the perspective of children, the mutual help that parents give to each other is part of the setting that provides advantages to youths who grow up in married-couple households. In addition to close support from the spouse, marriage connects people to other individuals, other social groups (e.g., in-laws), and other social institutions ( Stolzenberg et al. 1995 ; Waite 1995 ), and this integration into a wider social network has additional positive effects on both spouses and on their children ( McLanahan and Sandefur 1994 ).

The long-term commitment implied by marriage (as opposed to cohabitation) encourages the partners to invest in the relationship. Married couples indeed report higher levels of relationship quality than uncommitted cohabitors ( Brown and Booth 1996 ) and better emotional well-being ( Brown 2000 ). This pathway most likely explains the higher emotional satisfaction with sex generally reported by married individuals ( Waite and Joyner 2001 ). Evidence of the impact of marriage on relationship quality comes also from studies on domestic violence: the stronger commitment implied by marriage (or even the promise of marriage in the form of engagement) inhibits aggression ( Stets 1991 ; Waite 2000 ).

Like marriage, the institution of religion is an integrative force. Religious congregations offer regular opportunities to socialize and interact with friends who share similar values; they offer assistance to members in need; they foster a sense of community through which participants help one another. Ellison and George (1994) find that people who frequently attend religious services not only have larger social networks, but also hold more positive perceptions of the quality of their social relationships. The positive association between religious involvement and longevity is accounted for in part by this channel ( Strawbridge et al. 1997 ; Hummer et al. 1999 ).

Recent research has emphasized that religion can play a pivotal role in the socialization of youth by contributing to the development of social capital. Religious congregations often sponsor family activities, stimulating the cultivation of closer parent–child relations; they also bring children together with grandparents and other supportive adults (parents of peers, Sunday-school teachers) in an environment of trust. This broad base of social ties can be a rich source of positive role models, confidants, useful information, and reinforcement of values that promote educational achievement. The positive impact of religious involvement on various measures of educational outcomes has been attributed largely to this pathway ( Regnerus 2000 ; Muller and Ellison 2001 ; Lehrer 2003a ).

At the other end of the age spectrum, the social ties provided by religious institutions are of special value to the elderly, helping them deal with the many difficult challenges that tend to accompany old age: illness, dependency, loss, and loneliness ( Levin 1994 ).

Healthy behaviors and lifestyles

Beyond its integrative function, emphasized above, marriage also has a regulative function. Married individuals, especially men, are more likely than their single counterparts to have someone who closely monitors their health-related conduct; marriage also contributes to self-regulation and the internalization of norms for healthful behavior ( Umberson 1987 ). Positive and negative externalities within marriage also play a role: when an individual behaves in a way that is conducive to good health, the benefits spill over to the spouse; similarly, unhealthy behaviors inflict damage not only on the individual but also on the partner. In this way, marriage promotes healthy conduct. In addition, the enhanced sense of meaning and purpose provided by marriage inhibits self-destructive activities ( Gove 1973 ). Consistent with this channel of causality, married individuals have lower rates of mortality for virtually all causes of death in which the person’s psychological condition and behavior play a major role, including suicide and cirrhosis of the liver ( Gove 1973 ). Lillard and Waite (1995) find that for men (but not for women) there is a substantial decline in the risk of death immediately after marriage, which suggests that the regulation of health behaviors is a key mechanism linking marriage to physical health benefits in the case of men.

Religion also serves a regulative function. Most faiths have teachings that encourage healthy behaviors and discourage conduct that is self-destructive; they also provide moral guidance about sexuality. Some religions have specific regulations limiting or prohibiting the consumption of alcohol, tobacco, caffeine, and potentially harmful foods. Several studies show that religious involvement is generally associated with health-promoting behaviors ( Koenig et al. 2001 ) and that such behaviors explain in part the connection between religion and longevity ( Strawbridge et al. 1997 ; Hummer et al. 1999 ).

Economic benefits from marriage

Marriage leads to increases in economic well-being for several reasons, including the pooling of risks (e.g., one spouse may increase the level of work in the labor force if the other becomes unemployed), economies of scale (e.g., renting a large apartment costs less than renting two small apartments), and public goods (e.g., a husband and wife can both enjoy all of the beauty of the pictures hanging on the wall). Division of labor and specialization are particularly important sources of gains from marriage, permitting the partners to produce and consume substantially more than twice the amount each could produce individually ( Becker 1991 ). The long-term horizon implied by marriage gives each of the spouses the ability to neglect some skills and focus on the development of others. Gains from such specialization are responsible, in part, for the “marriage premium.” Married men can specialize in labor market activities more than single men, thereby gaining a productivity advantage. Specialization also encourages women to make human capital investments that advance their husbands’ careers ( Grossbard-Shechtman 1993 ).

For all of these reasons, marriage promotes higher levels of economic well-being. This factor accounts to a large extent for the advantages that accrue to children raised by two parents ( McLanahan and Sandefur 1994 ). From an economic perspective, a two-parent household is also the optimal institutional arrangement for raising children for another reason: there is a tendency for the level of expenditures on children to be inefficiently low when the father is not present. Inadequate provision of the couple’s collective good—child expenditures—occurs because of the father’s lack of control over the allocation of resources by the mother ( Weiss and Willis 1985 ).

The very substantial increase in economic resources that marriage implies for women may lead to better health directly, by improving general standards of living and access to medical resources, as well as indirectly by reducing levels of stress ( Hahn 1993 ). Consistent with this research, Lillard and Waite (1995) find that the greater financial resources available in married-couple households account for most of the positive effect of marriage on longevity for women, but not for men.

Spiritual benefits from religion

Some facets of religion lead to spiritual benefits that are unique to religious experiences. Idler and Kasl (1992) underscore the importance of religious rituals, such as the annual observance of religious holidays, noting that the periodicity of these celebrations reminds members of their shared past and their connection to preceding generations. Religious belief can also serve as a coping mechanism that helps individuals deal with conflict and difficult life-cycle stages, such as the assertion of independence by adolescent children ( Pearce and Axinn 1998 ), as well as bereavement and major health problems ( Pargament et al. 1990 ). In addition, personal faith can provide a sense of meaning that tends to reduce helplessness and heighten optimism. As Koenig (1994) notes, the religious prescription to love and forgive others can also have positive consequences for emotional well-being. The intangible nature of these effects defies easy quantification.

Overall, there is evidence of a strong association between stable marriages and a wide range of positive outcomes for children and adults, and the same is true in the case of religious involvement. However, the benefits are by no means uniform for all individuals, and significant exceptions may be cited. In addition, issues of selection bias deserve special attention.

Variations across individuals and exceptions

The benefits of religious involvement vary across individuals, as do the costs. The costs are higher for those with a more secular orientation, and to the extent that religious involvement is a time-intensive activity, costs are also higher for those with a higher wage rate and opportunity cost of time. As to the benefits, the spiritual gains associated with religious activity increase with the stock of religious capital: those who have made greater investments in religion stand to benefit more from religious participation ( Iannaccone 1990 ). Regnerus and Elder (2001) find support for the hypothesis that by providing functional communities amidst dysfunction, religious institutions are especially valuable in enhancing social capital for disadvantaged youths. The elderly and those with serious physical health problems also appear to derive substantial benefits from religious involvement ( Koenig 1994 ; Musick 1996 ).

Membership in some religious groups may reduce rather than enhance economic well-being. For example, the religious beliefs of conservative Protestants can discourage intellectual inquiry and have been linked with lower educational attainment ( Darnell and Sherkat 1997 ; Sherkat and Darnell 1999 ; Lehrer 1999 , 2003a ), implying negative consequences for earnings. There is also evidence that certain forms of religious beliefs and practices may not be beneficial for mental and physical health. Pargament et al. (1998) examine the role of religion as a coping tool, making a distinction between positive and negative religious coping. The former includes methods that reflect a secure relationship with God and a sense of spiritual connectedness with others. The latter is based on a pessimistic world view, a tenuous relationship with God, and a perception that God can inflict punishment. While the positive religious coping methods are associated with higher levels of mental well-being, the opposite is true of the negative methods—an indication that religion has the capacity to cause distress and make things worse. Some religious teachings also promote the avoidance of medical services and can lead to serious adverse consequences for health (e.g., see Asser and Swan 1998 ).

The benefits of marriage are also far from uniform. While the economic gains stemming from the joint consumption of public goods and from economies of scale are likely to vary only weakly with the quality of the union, most of the benefits from marriage vary closely with marital quality. For example, Gray and Vanderhart (2000) find that the marriage premium increases with marital stability: when the marriage is perceived to be solid, a woman is much more likely to make investments that enhance her husband’s career. The mental and physical health benefits of marriage have also been found to vary with the quality of the relationship ( Horwitz et al. 1996 ; Wickrama et al. 1997 ). In the extreme case of very poor marital quality, the consequences for health and well-being are clearly negative. For instance, Kiecolt-Glaser et al. (1993) show that serious conflict within a marriage can lead to adverse immunological changes, increasing the risk of illness. When marital quality becomes very low, so that one or both partners conclude that the benefits from remaining married have come to be smaller than the costs, the result may well be divorce. Lehrer (2003b) reviews the characteristics and behaviors of individuals and couples that make this scenario most likely.

An understanding of the circumstances under which marriage is or is not beneficial can shed some light on the current policy debate in the United States regarding the promotion of marriage. One of the goals of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 was to reduce out-of-wedlock childbearing and to encourage the formation and maintenance of two-parent families. 3 More recently, the Bush administration has proposed spending more than $1 billion over five years on programs to promote “healthy marriages” ( Carlson et al. 2001 ; McLanahan et al. 2001 ). Under the proposed plan, states may be eligible for federal funds if they develop programs to promote marriage. Such programs might include premarital counseling, marriage workshops, programs to enhance mental well-being, and additional welfare benefits for couples who enter formal marriage. Our review of the literature suggests that initiatives that enhance relationship skills may be helpful, as such skills are important to a stable marriage and young adults who grew up in non-intact homes may well be weak in this area ( Amato 1996 ). Complementary programs to address problems of depression and drug use may also help, on this as well as other fronts ( Lehrer et al. 2002a , 2002b ). On the other hand, financial incentives or negative economic pressures to enter formal marriage are likely to do more harm than good, by encouraging unions of poor marital quality. 4

Issues of selection bias

As we indicated earlier in this commentary, problems of selection bias affect many of the studies in both bodies of literature. The better outcomes observed for individuals in stable marriages may result in part from the greater likelihood that healthy, happy, and wealthy people marry and stay married. Results from analyses of marriage that have addressed the issue of selection biases suggest that they are indeed sizable in magnitude (e.g., Korenman and Neumark 1991 ; Lillard and Panis 1996 ; Horwitz et al. 1996 ; Simon 2002 ). The biases, however, do not always operate in the direction suggested by conventional wisdom. 5 An important item in the agenda for future research is to do more along the lines of the studies cited above, in an effort to better sort out the associational and causal relationships between marriage and well-being. Of particular value would be studies that specifically model the processes through which some individuals select or are selected into stable marriages and others are not. The corresponding gaps in our knowledge are even more pronounced in the case of the literature on religion.

The intersection of religion and marriage

In thinking about the role of religion in the lives of married people, a good point of departure is the concept that religion is a complementary trait within marriage. Religion affects many activities that husband and wife engage in as a couple beyond the purely religious sphere ( Becker 1991 ). Religion influences the education and upbringing of children, the allocation of time and money, the cultivation of social relationships, and often even the place of residence. Thus there is a greater efficiency and less conflict in a household if the spouses share the same religious beliefs. Furthermore, as Pearce and Axinn (1998) emphasize, just as religion is an integrative force in society, so it can have this effect also within the family: shared religious experiences can increase cohesion among family members.

The other side of this argument is that a difference in religion between partners may be a destabilizing force within a marriage. Empirical analyses have found that religious heterogamy increases the risk of marital conflict and instability ( Michael 1979 ; Lehrer 1996 ). A more detailed analysis that examines different types of interfaith unions shows that intermarriage comes in various forms and shades. Some interfaith marriages, such as those involving members of different ecumenical Protestant denominations, are quite stable. In contrast, the probability of divorce is high among unions in which the partners have very different religious beliefs or are members of religious groups that have sharply defined boundaries. Additional analyses for Catholics and Protestants reveal that unions that achieve homogamy through conversion are at least as stable as those involving partners who were raised in the same faith ( Lehrer and Chiswick 1993 ).

The hypothesis that religious involvement may enhance marital happiness and stability has also received considerable attention in the literature. A large number of studies report a positive relationship between measures of religiosity and indicators of marital satisfaction and stability (e.g., Glenn and Supancic 1984 ; Heaton and Pratt 1990 ). However, the cross-sectional design of these analyses, with both key variables measured at the same point in time, implies that the estimates confound the direction of causality. Two recent studies have addressed this shortcoming. Using data from waves 1 and 2 of the National Surveys of Families and Households, Call and Heaton (1997) find that higher levels of husband’s and wife’s church attendance as found at the initial interview reduce the likelihood that the union will have been dissolved by the second wave, about five years later; differences between the spouses in attendance levels are found to be destabilizing. In contrast, in their analysis of a 12-year longitudinal sample, Booth et al. (1995) find that although an increase in religious activity over time reduces the chance of considering divorce, it does not increase marital happiness or decrease marital conflict.

The studies in this literature, however, are subject to a critical limitation: none of them has modeled the effects of religious participation on marital satisfaction or stability in a way that allows the relationship to vary depending on the religious composition of the union. Theoretically, if a marriage is homogamous, more religious involvement by one of the spouses, and especially by both spouses, should be a positive force within the union. The opposite would be expected if the marriage is heterogamous, involving two faiths that are quite different. Thus a clear understanding of how religious participation influences marital harmony must await analyses that are conducted separately for these two very different groups. Improving our knowledge about these relationships, especially as they pertain to children growing up in inter-faith homes, should have high priority in the agenda for future research.

Our comparative analysis of religion and marriage in the United States reveals remarkable similarities in the benefits that are associated with these two social institutions, and also in the pathways through which they operate. Being married and being involved in religious activities are generally associated with positive effects in several areas, including physical and mental health, economic outcomes, and the process of raising children. For some of these influences, such as the effect of religion and marriage on longevity, substantial evidence has been accumulated. For other relationships, such as the effect of religious involvement on mental health, the evidence is not as strong. A large body of research points to social integration and the regulation of health behaviors as key pathways through which both institutions exert an influence. In addition, there is evidence of substantial economic gains from marriage, while religious experiences can significantly improve and enrich people’s spiritual lives.

Marriage and religion work independently as integrative forces. They also seem to work together as integrative forces. At present, married adults and the children living with them may be greater beneficiaries of the integration and social support from religious organizations; having children of school age seems to move married couples toward stronger ties with their church, synagogue, or mosque. But adults and children in other types of families seem to move away from religious participation ( Stolzenberg et al. 1995 ). In a recent article, Wilcox (2000) points out that although mainline Protestant denominations talk a great deal about acceptance of single-parent or other alternative family forms, and about the needs of single adults, almost all of their formal activities are aimed at married-couple families. Lacking the social ties provided by marriage, single individuals, especially those who are raising children, could potentially derive important benefits from the support that religious institutions can provide.

There is much that we do not know about the intersection between religion and marriage, and about inter-faith couples in particular. Such couples often face a choice between raising their children in a home without religion and raising them in the faith of one of the parents. The research to date suggests that some religious involvement is generally beneficial for young people. At the same time, religious heterogamy is known to be a destabilizing force in a marriage, and it seems likely that active participation in religious activities by only one parent and the children would accentuate the differences. Estimates of the magnitudes of these effects would be of value in guiding the choices of interfaith couples.

Religiosity has many dimensions, including attendance at religious services, private devotion, and the salience of religion in the individual’s life. The literature contains conflicting findings regarding which of these aspects is most important, and the effects associated with the various dimensions are not always consistent. Research seeking to clarify these differences and to identify patterns among the discrepant results would be desirable.

With regard to marriage, most of the studies to date have focused on comparing outcomes for those who are currently married with those who have never married or are widowed or divorced. We know much less about the implications of formal marriage versus informal cohabiting arrangements, especially from the perspective of the children growing up in these two types of households. A substantial amount of research in progress seeks to fill this gap (e.g., Duncan et al. 2003 ; Kiernan 2003 ; Lerman 2003 ; Manning and Brown 2003 ).

As we continue to advance our knowledge in each of these fields, it will be helpful to integrate them to a much larger extent than has been done to date. At a minimum, it would be useful if researchers who are focusing on issues pertaining to marriage would include a richer set of controls for religion, and vice versa. Additional research seeking to improve our understanding of the complex relationships between religion and marriage would be especially valuable.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute on Aging through Grant No. P-01 AG18911 and through the Alfred P. Sloan Center for Parents, Children and Work at the University of Chicago. A previous version was presented at a workshop on Ties That Bind: Religion and Family in Contemporary America, 17–18 May 2001, Princeton University. We are indebted to Barry Chiswick and participants in the Microeconomics and Human Resources Workshop at the University of Illinois at Chicago for many helpful comments on earlier drafts. Sarinda Taengnoi provided skillful research assistance.

1 The “religion sector” encompasses all aspects of religion in a given country, including denominational composition and the nature and extent of religiousness.

2 Another way of stating this argument is to note that inputs that may improve health and well-being, such as religion, are most likely to be “purchased” by those individuals who need their protection the most; see Lillard and Panis (1996) for a parallel argument in the marriage literature.

3 See Gennetian and Knox (2003) for a preliminary examination of the effects of the Act in the area of union formation and dissolution.

4 A firestorm of public debate surrounds these various efforts by the current US administration to strengthen marriage. Proponents argue that marriage is good (for all the reasons outlined here) and therefore should be encouraged by the government. Opponents argue that government intervention in this area is inappropriate. Many view these initiatives as inconsistent with equality for women ( Stacey 1993 ) and as a waste of money that could be used for job training or programs to prevent domestic violence. Support for marriage (as opposed to families) seems to some to discriminate against single mothers, those who choose to remain single or want to marry but have been unable to do so, gay and lesbian individuals and couples, cohabitors, the poor, and minorities. (See “Young feminists take on the family,” part of a special issue of The Scholar & Feminist Online , www.barnard.edu/sfonline ). For additional discussion of this issue, see Carlson et al. 2001 ; Seiler 2002 ; and Amato 2003 . Similarly, the faith-based initiatives advanced by President Bush early in his presidency were highly controversial.

5 For example, in their simultaneous-equations model of marital transitions, health, and mortality, Lillard and Panis (1996) find empirical support for the argument that unhealthy men have a particularly strong incentive to seek out the health protection offered by marriage. Their results show adverse selection into marriage based on self-perceived general health. At the same time, they also find evidence of positive selection into marriage based on unobserved characteristics, such as preferences for risk and adventure and for social contact.

- Amato Paul R. Explaining the intergenerational transmission of divorce. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1996; 58 :628–40. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Amato Paul R. Relationship skills training and marriage among low-income couples. presented at the annual meetings of the Population Association of America; Minneapolis. 2003. [ Google Scholar ]

- Amato Paul R, Juliana Sobolewski. The effects of divorce and marital discord on adult children’s psychological well-being. American Sociological Review. 2001 December; 66 :900–921. [ Google Scholar ]

- Angel Ronald, Jacqueline Lowe Worobey. Single motherhood and children’s health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1988 March; 29 :38–52. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Asser Seth M, Rita Swan. Child fatalities from religion-motivated medical neglect. Pediatrics. 1998; 101 (4):625–629. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Barro Robert J, McCleary Rachel M. Religion and political economy in an international panel, unpublished manuscript. Harvard University; 2002. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bartowski John P, Wilcox Bradford, Ellison Christopher G. Charting the paradoxes of evangelical family life: Gender and parenting in conservative Protestant households. Family Ministry. 2000; 14 (4):9–21. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bearman Peter S, Hannah Bruckner. Promising the future: Virginity pledges and first intercourse. American Journal of Sociology. 2001; 106 (4):859–912. [ Google Scholar ]

- Becker Gary. A Treatise on the Family. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1991. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bennett Trude, Braveman Paula, Egerter Susan, Kiely John L. Maternal marital status as a risk factor for infant mortality. Family Planning Perspectives. 1994; 26 :252–256. 271. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Booth Alan, Johnson David R, Branaman Ann, Alan Sica. Belief and behavior: Does religion matter in today’s marriage? Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995; 57 (3):661–671. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brown Susan. The effects of union type on psychological well-being: Depression among cohabitors versus marrieds. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000; 41 :241–255. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brown Susan, Alan Booth. Cohabitation versus marriage: A comparison of relationship quality. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1996; 58 (3):668–678. [ Google Scholar ]

- Call Vaughn R, Heaton Tim B. Religious influence on marital stability. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1997; 36 (3):382–392. [ Google Scholar ]

- Carlson Marcia, McLanahan Sara, England Paula. Center for Research on Child Wellbeing. Princeton University: Working Paper # 01-06-FF; 2001. Union formation and dissolution in fragile families. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cherlin Andrew J. Going to extremes: Family structure, children’s well-being, and social science. Demography. 1999; 36 (4):421–428. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cherlin Andrew J, Chase-Lansdale Lindsay, McRae C. Effects of parental divorce on mental health throughout the life course. American Sociological Review. 1998; 63 :239–249. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chiswick Barry R. Differences in education and earnings across racial and ethnic groups: Tastes, discrimination, and investments in child quality. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1988; 103 (3):571–597. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chiswick Carmel U. An economic model of Jewish continuity. Contemporary Jewry. 1999; 20 :30–56. [ Google Scholar ]

- Coontz Stephanie, Franklin Donna. When the marriage penalty is marriage. The New York Times. 1997 28 October;:A23. [ Google Scholar ]

- Darnell Alfred, Sherkat Darren E. The impact of Protestant fundamentalism on educational attainment. American Sociological Review. 1997 April; 62 :306–315. [ Google Scholar ]

- Donahue Michael J, Benson Peter L. Religion and the well-being of adolescents. Journal of Social Issues. 1995; 51 (2):145–160. [ Google Scholar ]

- Duncan Greg, England Paula, Wilkerson Bessie. Cleaning up their act: The impacts of marriage, cohabitation, and fertility on licit and illicit drug use. presented at the annual meetings of the Population Association of America; Minneapolis. 2003. [ Google Scholar ]

- Durkheim Emile. Suicide. Glencoe, IL: The Free Press; 18971951. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ellison Christopher G, Anderson Kristin L. Religious involvement and domestic violence among U.S couples. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2001; 40 (2):269–286. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ellison Christopher G, Bartkowski John P, Anderson Kristin L. Are there religious variations in domestic violence? Journal of Family Issues. 1999; 20 (1):87–113. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ellison Christopher G, George Linda K. Religious involvement, social ties, and social support in a southeastern community. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1994; 33 (1):46–61. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ellison Christopher G, Levin Jeffrey S. The religion–health connection: Evidence, theory, and future directions. Health Education and Behavior. 1998; 25 (6):700–720. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Freeman Richard B. Who escapes? The relationship of churchgoing and other background factors to the socioeconomic performance of black male youths from inner-city tracts. In: Freeman Richard B, Holzer Harry J., editors. The Black Youth Employment Crisis. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 1986. pp. 353–376. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gennetian Lisa A, Knox Virginia. Can social welfare policy increase marriage or decrease divorce?. presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America; Minneapolis. 2003. [ Google Scholar ]

- Glenn Norval D, Supancic Michael. The social and demographic correlates of divorce and separation in the United States: An update and reconsideration. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1984 August;:563–575. [ Google Scholar ]

- Goodwin James S, Hunt William C, Key Charles R, Samet Jonathan M. The effect of marital status on stage, treatment, and survival of cancer patients. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1987; 258 (21):3125–3130. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gove Walter R. Sex, marital status, and mortality. American Journal of Sociology. 1973; 79 :45–67. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gray Jeffrey S, Vanderhart Michel J. On the determination of wages: Does marriage matter? In: Waite Linda J, Bachrach Christine, Hindin Michelle, Thomson Elizabeth, Thornton Arland., editors. The Ties that Bind: Perspectives on Marriage and Cohabitation. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 2000. pp. 356–367. [ Google Scholar ]

- Greeley Andrew M. Faithful Attraction: Discovering Intimacy, Love, and Fidelity in American Marriage. New York: Tom Doherty Associates; 1991. [ Google Scholar ]

- Grossbard-Shechtman Shoshana. On the Economics of Marriage: A Theory of Marriage, Labor, and Divorce. Boulder: Westview Press; 1993. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hahn Beth A. Marital status and women’s health: The effect of economic marital acquisitions. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1993 May; 55 :495–504. [ Google Scholar ]

- Harker Kathryn. Immigrant generation, assimilation, and adolescent psychological well-being. Social Forces. 2001; 79 (3):969–1004. [ Google Scholar ]

- Heaton Tim B, Pratt Edith L. The effects of religious homogamy on marital satisfaction and stability. Journal of Family Issues. 1990; 11 (2):191–207. [ Google Scholar ]

- Horwitz Allan V, White Helene Raskin, Howell-White Sandra. Becoming married and mental health: A longitudinal analysis of a cohort of young adults. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1996 November; 58 :895–907. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hummer Robert A, Padilla YC, Echevarria S, Kim E. Does parental religious involvement affect the birth outcomes and health status of young children?. presented at the annual meetings of the Population Association of America; Atlanta. 2002. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hummer Robert A, Rogers Richard G, Nam Charles B, Ellison Christopher G. Religious involvement and U.S. adult mortality. Demography. 1999; 36 (2):273–285. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Iannaccone Laurence R. Religious practice: A human capital approach. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1990; 29 :297–314. [ Google Scholar ]

- Idler Ellen, Kasl Stanislav V. Religion, disability, depression, and the timing of death. American Journal of Sociology. 1992; 97 (4):1052–1079. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kiecolt-Glaser Janice, Malarkey William B, Chee MaryAnn, Newton Tamara, Cacioppo John T, Mao Hsiao-Yin, Glaser Ronald. Negative behavior during marital conflict is associated with immunological down-regulation. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1993; 55 :395–409. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kiernan Kathleen. Unmarried parenthood: Does it matter?. presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America; Minneapolis. 2003. [ Google Scholar ]

- Koenig Harold G. Religion and hope for the disabled elder. In: Levin Jeffrey S., editor. Religion in Aging and Health: Theoretical Foundations and Methodological Frontiers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1994. pp. 18–51. [ Google Scholar ]

- Koenig Harold G, McCullough Michael E, Larson David B. Handbook of Religion and Health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [ Google Scholar ]

- Korenman Sanders, David Neumark. Does marriage really make men more productive? Journal of Human Resources. 1991; 26 (2):282–307. [ Google Scholar ]

- Laumann Edward O, Gagnon John H, Michael Robert T, Michaels Stuart. The Social Organization of Sexuality: Sexual Practices in the United States. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1994. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lehrer Evelyn L. The determinants of marital stability: A comparative analysis of first and higher order marriages. In: Schultz T Paul., editor. Research in Population Economics. Vol. 8. Greenwich: JAI Press; 1996. pp. 91–121. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lehrer Evelyn L. Religion as a determinant of educational attainment: An economic perspective. Social Science Research. 1999; 28 :358–379. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lehrer Evelyn L. Religiosity as a determinant of educational attainment: The case of conservative Protestants in the United States,unpublished manuscript. University of Illinois; Chicago: 2003a. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lehrer Evelyn L. The economics of divorce. In: Grossbard-Shechtman Shoshana., editor. Marriage and the Economy: Theory and Evidence from Industrialized Societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2003b. pp. 55–74. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lehrer Evelyn, Chiswick Carmel U. Religion as a determinant of marital stability. Demography. 1993; 30 (3):385–404. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lehrer Evelyn, Crittenden Kathleen, Norr Kathleen. Depression and welfare dependency among inner-city minority mothers. Social Science Research. 2002a; 31 :285–309. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lehrer Evelyn, Crittenden Kathleen, Norr Kathleen. Illicit drug use and reliance on welfare. Journal of Drug Issues. 2002b; 32 (1):179–207. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lerman Robert. How do marriage, cohabitation, and single parenthood affect the material hardships of families with children?. presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America; Minneapolis. 2003. [ Google Scholar ]

- Levin Jeffrey S. Religion and health: Is there an association, is it valid, and is it causal? Social Science and Medicine. 1994; 38 (11):1475–1482. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Levin Jeffrey S, Markides Kyriakos S, Ray Laura A. Religious attendance and psychological well-being in Mexican-Americans: A panel analysis of three-generations data. The Gerontologist. 1996; 36 (4):454–463. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lillard Lee A, Constantijn Panis. Marital status and mortality: The role of health. Demography. 1996; 33 (3):313–327. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lillard Lee A, Waite Linda J. ‘Til death do us part’: Marital disruption and mortality. American Journal of Sociology. 1995; 100 (5):1131–1156. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lupton Joseph, Smith James P. Marriage, assets, and savings. In: Grossbard-Shechtman Shoshana., editor. Marriage and the Economy: Theory and Evidence from Industrialized Societies. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 2003. pp. 129–152. [ Google Scholar ]

- Manning Wendy D, Brown Susan L. Children’s economic well-being in cohabiting parent families: An update and extension. presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America; Minneapolis. 2003. [ Google Scholar ]

- Marchena Elaine, Waite Linda J. Marriage and childbearing attitudes in late adolescence: Gender, race and ethnic differences. paper presented at the meeting of the Population Association of America; March 2000; Los Angeles. 2001. [ Google Scholar ]

- Marks Nadine F, Lambert James D. Marital status continuity and change among young and midlife adults: Longitudinal effects on psychological well-being. Journal of Family Issues. 1998; 19 :652–686. [ Google Scholar ]

- McLanahan Sara, Sandefur Gary. Growing Up with a Single Parent: What Hurts, What Helps. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1994. [ Google Scholar ]

- McLanahan Sara, Garfinkel Irwin, Mincy Ronald. Policy Brief No. 10. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution; 2001. Fragile families, welfare reform, and marriage. [ Google Scholar ]

- Michael Robert T. Determinants of divorce. In: Levy-Garboua Louis., editor. Sociological Economics. London: Sage; 1979. pp. 223–269. [ Google Scholar ]

- Muller Chandra, Ellison Christopher G. Religious involvement, social capital, and adolescents’ academic progress: Evidence from the National Education Longitudinal Study of 1988. Sociological Focus. 2001; 34 (2):155–183. [ Google Scholar ]

- Murphy Mike, Glaser Karen, Grundy Emily. Marital status and long-term illness in Great Britain. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1997; 59 (1):156–164. [ Google Scholar ]

- Musick Mark A. Religion and subjective health among black and white elders. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1996 September; 37 :221–237. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Myers David G. The American Paradox: Spiritual Hunger in an Age of Plenty. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 2000. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pargament Kenneth I, Ensig David S, Falgout Kathryn, Olsen Hannah, Reilly Barbara, Van Haitsma Kimberly, Warren Richard. God help me: Religious coping efforts as predictors of the outcomes to significant negative life events. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1990; 18 (6):793–824. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pargament Kenneth I, Smith Bruce W, Koenig Harold G, Lisa Perez. Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1998; 37 (4):710–724. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pearce Lisa D, Axinn William G. The impact of family religious life on the quality of mother–child relations. American Sociological Review. 1998 December; 63 :810–828. [ Google Scholar ]

- Regnerus Mark D. Shaping schooling success: Religious socialization and educational outcomes in metropolitan public schools. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2000; 39 :363–370. [ Google Scholar ]

- Regnerus Mark D, Elder Glenn. Staying on track: Religious influences in high and low-risk settings. presented at the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association; Anaheim. 2001. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ross Catherine E, Mirowsky John, Goldsteen Karen. The impact of the family on health: A decade in review. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1990 November; 52 :1059–1078. [ Google Scholar ]

- Seiler Naomi. Is teen marriage a solution?, unpublished manuscript. Center for Law and Social Policy; 2002. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sherkat Darren E, Alfred Darnell. The effects of parents’ fundamentalism on children’s educational attainment: Examining differences by gender and children’s fundamentalism. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1999; 38 :23–35. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sherkat Darren E, Ellison Christopher G. Recent developments and current controversies in the sociology of religion. Annual Review of Sociology. 1999; 25 :363–394. [ Google Scholar ]

- Simon Robin W. Revisiting the relationship among gender, marital status, and mental health. American Journal of Sociology. 2002; 107 :1065–1096. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sloan Richard, Bagiella Emilia, Powell Tia. Religion, spirituality, and medicine. Lancet. 1999 February; 353 :664–667. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stacey Judith. Good riddance to ‘The family’: A response to David Popenoe. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1993; 55 :545–547. [ Google Scholar ]

- Stets Jan E. Cohabiting and marital aggression: The role of social isolation. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1991 August; 53 :669–680. [ Google Scholar ]

- Stolzenberg Ross M, Blair-Loy Mary, Waite Linda J. Religious participation over the life course: Age and family life cycle effects on church membership. American Sociological Review. 1995 February; 60 :84–103. [ Google Scholar ]

- Strawbridge William J, Cohen Richard D, Shema Sarah J, Kaplan George A. Frequent attendance at religious services and mortality over 28 years. American Journal of Public Health. 1997; 87 (6):957–961. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tucker Joan S, Friedman Howard S, Schwartz Joseph E, Criqui Michael H, Tomlinson-Keasey Carol, Wingard Deborah L, Martin Leslie R. Parental divorce: Effects on individual behavior and longevity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997; 73 (2):381–391. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Umberson Deborah. Family status and health behaviors: Social control as a dimension of social integration. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1987 September; 28 :306–319. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Living Arrangements of Children Under 18 Years Old: 1960 to Present U.S. Census Bureau. 2001. Online. Available: http://www.census.gov/population/socdemo/hh-fam/tabCH-1.xls .

- Waite Linda J. Does marriage matter? Demography. 1995; 32 (4):483–507. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Waite Linda J. Trends in men’s and women’s well-being in marriage. In: Waite Linda J, Bachrach Christine, Hindin Michelle, Thomson Elizabeth, Thornton Arland., editors. The Ties that Bind: Perspectives on Marriage and Cohabitation. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 2000. pp. 368–392. [ Google Scholar ]

- Waite Linda J, Gallagher Maggie. The Case for Marriage: Why Married People Are Happier, Healthier, and Better Off Financially. New York: Doubleday; 2000. [ Google Scholar ]

- Waite Linda J, Kara Joyner. Emotional satisfaction and physical pleasure in sexual unions: Time horizon, sexual behavior and sexual exclusivity. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2001 February; 63 :247–264. [ Google Scholar ]

- Weiss Yoram, Willis Robert J. Children as collective goods. Journal of Labor Economics. 1985; 3 :268–92. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wickrama KAS, Lorenz Frederick O, Conger Rand D, Elder Glen H. Marital quality and physical illness: A latent growth curve analysis. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1997 February; 59 :143–155. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bradford Wilcox W. For the sake of the children? Family-related discourse and practice in the mainline. Public Role of Mainline Protestantism Project; Princeton University. 2000. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zuckerman Diana M, Kasl Stanislav V, Ostfeld Adrian M. Psychosocial predictors of mortality among the elderly poor: The role of religion, well-being, and social contacts. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1984; 119 (3):410–423. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- End of Life

- Human Dignity

- Domestic Religious Freedom

- Freedom of Conscience

- International Religious Freedom

- Marriage and Family Formation

- Biblical Worldview

- Founding Ideals

- Health Care

- Legislation

- Broadcast Archives

- Email the Show

- Radio Stations

- Press Releases

- The Washington Stand

- Outstanding Podcast

- Vision & Mission

- State Groups

- Internships

- Subscriptions

- Other FRC Sites The Washington Stand Planned Giving PrayVoteStand.org FRCAction.org StandCourageous.com CommunityImpact.frc.org WatchmenPastors.org Center for Biblical Worldview

Advanced Search

Not able to find what you're looking for? Use the search bar for specific content or feel free to contact us for further assistance.

- Civil Society

- Life and Human Dignity

- Marriage, Family and Sexuality

- Religious Liberty and Conscience

- Men's Events

- Pastor Events

- Previous Events

- Speaker Series

- Upcoming Events

©2024 Family Research Council

800-225-4008

801 G Street NW Washington, D.C. 20001

Privacy Policy

TinyURL: https://tinyurl.com/yxzyqddz

Table of Contents

1.1 shaping citizens, 1.2 contributions of married couples, 1.3 retreat from marriage, 2. chastity impacts marriage, 3. religion impacts chastity, 4. marriage, religion, and chastity impact sexual enjoyment, marriage and religious faithfulness.

The well-being of the United States is strongly related to marriage , 1) which is a choice about how individuals channel their sexuality . The implications of sexual choices are apparent when comparing family structures across societal measures, such as education and employment , as well as personal measures, like sexual satisfaction . Frequency of religious worship is pivotal in shaping these sexual choices. 2) In all cases, federal government data show that the intact married family that worships God weekly produces the most profitable and sexually satisfied citizens.

Simply put:

- Marriage impacts the economy , 3)

- Chastity impacts marriage,

- And worship impacts chastity . 4)

Decisions about sexual conduct—and how this plays out in marriage and family life—shape or misshape the ability of American society to function in its major tasks.

1. Marriage Impacts the Economy

One significant way by which marriage impacts the economy is its influence on the future workforce—its children .

According to the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, 5) American children raised in intact, married families have higher GPA’s 6) than those born into non-intact families . These children are more likely to get further in their education, 7) and to perform more diligently in school. 8)

When religion is factored in, children perform even better. This is especially true for children raised in low-income communities . According to Dr. Mark Regnerus of the University of Texas at Austin, weekly religious worship delivers educational benefits that are equivalent to moving the poorer children into middle class neighborhoods. 9) Nothing in public policy yields returns like these in education.

Therefore, it is no surprise that children raised in intact married families that attend religious services weekly are most likely to receive A’s in school. 10)

Common sense and myriad social science studies indicate that the better an individual does in school, the more that individual will earn later when he/ she joins the workforce . 11)

In addition to forming productive workforce participants, married couples also play an important role in sustaining the economy . Controlling for all relevant factors, men’s productivity increases about 26 percent when they marry. 12) Similarly, the most productive segment of the workforce is married men 13) with three or more children.

Marriage is especially necessary to fund the government . 14) The below chart of preliminary, unpublished data by Dr. Henry Potrykus should catch the eye of every politician: Married couples contribute at least 20 percent more to the tax pool than do their non-married male and female counterparts, controlling for related factors.

Despite the inherent value in marriage, adults have steadily retreated from marriage over the last several decades (see red trendline in graph below). 15) This decline in marriages, combined with the impact of marriage on tax contributions, means that the government has lost significant revenues from marriageable adults that remain single.

The role of marriage in shaping personal and societal outcomes clarifies the plight of the Black Family. 16) Black males who forego marriage are less likely to hold a steady job , are more likely to engage in risky behavior , and are less likely to contribute society than Black males who do marry. The retreat from marriage across all four different levels of education (high school dropout; high school graduation; college education; and even professional graduate education) among black men has undermined many of the gains made by the civil rights movement under Dr. Martin Luther King.

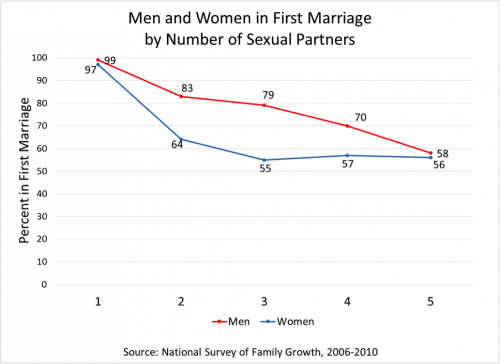

Marriage trends are driven by sexual decisions —chastity and monogamy, or their opposite, polyamory. The below chart, perhaps one of the most important in the social sciences, informs all other data in research related to marriage and the family.

This chart shows the status of American marriages five years into the marriage. Among both men and women who have never had any sexual partner other than their spouse (ie. they were totally monogamous), 97 percent of women and 99 percent of men were still married. For women who had one extra sexual partner (for most, before marriage) only 64 percent were still married—a drop of 33 percent, which is twice the rate of men. For those women who had two sexual partners outside of marriage, only 55 percent were still married five years down the road.