- Open access

- Published: 12 March 2019

Factors influencing unmet need for family planning among Ghanaian married/union women: a multinomial mixed effects logistic regression modelling approach

- Chris Guure 1 ,

- Ernest Tei Maya 2 ,

- Samuel Dery 1 ,

- Baaba da-Costa Vrom 1 ,

- Refah M. Alotaibi 3 ,

- Hoda Ragab Rezk 3 , 4 &

- Alfred Yawson 1

Archives of Public Health volume 77 , Article number: 11 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

17k Accesses

25 Citations

8 Altmetric

Metrics details

Unmet need for family planning is high (30%) in Ghana. Reducing unmet need for family planning will reduce the high levels of unintended pregnancies, unsafe abortions, maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality. The purpose of this study was to examine factors that are associated with unmet need for family planning to help scale up the uptake of family planning services in Ghana.

This cross sectional descriptive and inferential study involved secondary data analysis of women in the reproductive age (15–49 years) from the Ghana Demographic and Health Survey 2014 data. The outcome variable was unmet need for family planning which was categorized into three as no unmet need, unmet need for limiting and unmet need for spacing. Chi-squared test statistic and bivariate multilevel multinomial mixed effects logistic regression model were used to determine significant variables which were included for the multivariable multilevel multinomial mixed effects logistic regression model. All significant variables ( p < 0.05) based on the bivariate analysis were included in the multinomial mixed effects logistic regression model via model building approach.

Women who fear contraceptive side effects were about 2.94 (95% CI, 2.28, 3.80) and 2.58 (95% CI, 2.05, 3.24) times more likely to have an unmet need for limiting and spacing respectively compared to those who do not fear side effects. Respondents’ age was a very significant predictor of unmet need for family planning. There was very high predictive probability among 45–49 year group (0.86) compared to the 15–19 year group (0.02) for limiting. The marginal predictive probability for spacing changed significantly from 0.74 to 0.04 as age changed from 15 to 19 to 45–49 years. Infrequent sexual intercourse, opposition from partners, socio-economic (wealth index, respondents educational level, respondents and partner’s occupation) and cultural (religion and ethnicity) were all significant determinants of both unmet need for limiting and spacing.

Conclusions

This study reveals that fear of side effect, infrequent sex, age, ethnicity, partner’s education and region were the most highly significant predictors of both limiting and spacing. These factors must be considered in trying to meet the unmet need for family planning.

Peer Review reports

Beyond the health benefits that accrue to women, children and men from family planning, it is a catalyst for environmental sustainability, [ 1 ] and economic growth of countries [ 2 ]. Thus, Ghana’s strive to improve its economic fortunes and health of the populace will be difficult if efforts are not made to reduce its high unmet need for family planning.

Unmet need for family planning is essentially the percentage of married/union women of reproductive age who are not using any method of family planning but who would like to postpone the next pregnancy (unmet need for spacing) or do not want to have any more children (unmet need for limiting) [ 3 ]. The concept of unmet need defines the gap between women’s reproductive intentions and their contraceptive behaviour. Unintended pregnancies have serious consequences for the health and well-being of women and their families, particularly in developing countries where maternal mortality is high and induced abortions are often unsafe. More than 358,000 women die of pregnancy-related causes every year, according to a report from the World Health Organization [ 4 ]. Couples who use contraception have the ability to control the number and spacing of their children thus preventing unintended pregnancies, abortions and deaths related to pregnancy and childbirth.

The recent Ghana Demographic and Health Survey 2014, estimated that 30 % of currently married women have an unmet need for family planning services, with 17% having an unmet need for spacing and 13% having an unmet need for limiting. Knowledge of contraceptives is universal in the developed world and almost universal in the developing world [ 5 ]. Globally, there is a high saturation of knowledge on contraceptive methods, with knowledge of at least one contraceptive method in sub-Saharan Africa being approximately 85%, [ 6 ].

The 2014 Ghana Demographic and Health Survey found that 99% of women and men knew of at least one contraceptive method [ 7 ]. The survey also showed that modern contraceptive methods were more known than traditional ones among women, with the male condom (96%), injectable (92%), and pills (91%) being the most commonly known methods. However, there is considerable variability in this knowledge across different population demographics such as, age, occupation, religion and ethnicity [ 8 ]. Knowledge however does not directly translate to use.

The United Nations [ 9 ] report on world contraceptive patterns shows that 63% of women of reproductive age who are married or in a union use a contraceptive method. Globally, female sterilization is the most common method of contraception, used by 19% of married/union women of reproductive age (15–49 years) group. The IUD, used by 14% of women of reproductive age who are married or in a union, is the second most widely used contraceptive method in the world, followed by the pill.

Ghana is a signatory to the Family Planning 2020 (FP2020) and has committed to increasing modern contraceptive use among married/in union women from 22% in 2012 to 30% in 2020, (Government of Ghana (GOG), 2016). In Ghana, the prevalence of modern contraceptive use among married/in union women is 22%; that of unmet need among married/in union women is 30% and the demand for modern contraceptive satisfied is 39% [ 7 ]. With just 2 years to 2020, there is the need to increase efforts to satisfy women’s need for contraception. It is therefore imperative to look at the magnitude of the individual determinants and their effects on unmet need for contraception after accounting for unobserved household and/or cluster variations. Unlike contraceptive prevalence which does not consider women’s ability to become pregnant and their wishes for children unmet need for family planning, takes these factors into consideration. We therefore concentrated on unmet need for family planning which gives the vital information about women’s need for family planning.

Study design and data source

This study used a secondary data from the 2014 Ghana Demographic and Health Survey for the analysis. The 2014 Ghana Demographic and Health Survey (GDHS) is a nationally representative household survey that collects very wide range of population, health and other important indicators covering all the ten regions of Ghana. Participants in the survey were asked retrospective questions spanning 5 years prior to the survey.

Sampling approach and study population

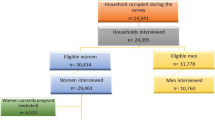

The 2014 GDHS followed a two-stage sample design and was intended to allow estimates of key indicators at the national level as well as for urban and rural areas and each of Ghana’s 10 administrative regions. The first stage involved selecting sample points (clusters) consisting of enumeration areas (EAs) delineated for the 2010 Ghana population and housing census (PHC). A total of 427 clusters were selected; 216 in urban areas and 211 in rural areas.

The second stage involved the systematic sampling of households. A household listing was undertaken in all the selected EAs in January–March 2014. The households included in the survey were randomly selected from the list. About 30 households were selected from each cluster to constitute the total sample size of 12,831 households. Because of the approximately equal sample sizes in each region, the sample is not self-weighting at the national level, and weighting factors have been added to the data file so that the results will be proportional at the national level [ 5 ]. In this current study, a total of 6503 (married/union) out of the 10,357 reproductive age women data were analysed in the 2014 GDHS.

Outcome variable, inclusion and exclusion criteria

The outcome variable of interest is unmet need for family planning. Unmet need for family planning was categorized into three; unmet need for spacing, unmet need for limiting and no unmet need. The categorization also conformed to the recently revised version of unmet need for family planning applied in DHS [ 10 ]. The number of participants who had their classification regarding unmet need for spacing, limiting and no unmet need after data manipulation and with only complete case analysis (respondents with no missing information) were 1708(26.26%), 2918(44.87%) and 1877(28.67%) respectively.

The inclusion criteria involved women in their reproductive ages, that is, 15–49 years and were either currently married or in a union. We included only married/ in union women with the reasonable assumption that they are exposed to regular sexual intercourse.

The exclusion criteria were married/in union women who had incomplete information (missing data).

Statistical analysis

The current analysis used both descriptive and inferential methods. Descriptive statistics used included frequencies and percentages. Both bivariate and multivariable techniques were used to assess statistical associations between the outcome variable and the predictors. The bivariate technique was applied to obtain predictors that had a statistically significant relationship with the outcome of interest (unmet need for family planning). In this approach, factors that were statistically significantly associated with the outcome were obtained via a simple multinomial mixed effects logistic regression model as well as chi-squared test of independence with the help of their confidence intervals (CI) and p -values. P -value less than or equal to 0.10 was used to retain and include variables in the multivariable analysis to obtain the risk ratios as a measure of association.

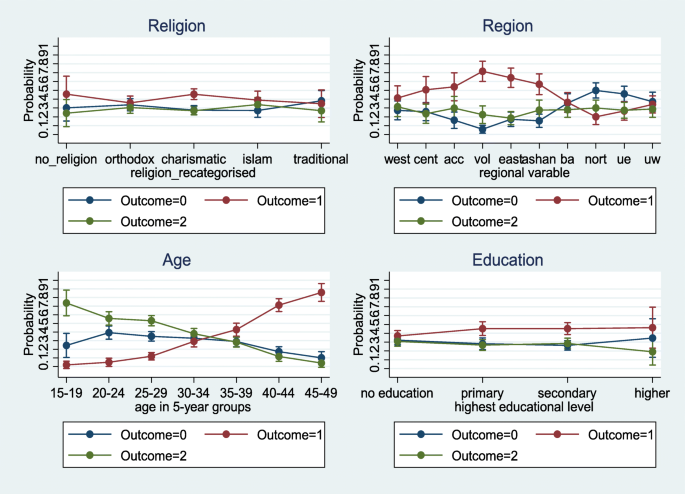

Further analysis were carried out with four selected variables (religion, region, education and age) to obtain predictive probabilities which enabled us observe the association between these predictor variables and the outcome. These were randomly picked for the purpose exploration. Although the simple multinomial mixed effects logistic regression model is complex, we used it because of the need to adjust and obtain parameter estimates through a fixed effects (multivariable) model, outcome variable categorized into three levels (referred to as multinomial), nesting nature of the GDHS data (multilevel) and the need to account for the cluster effects (via a random effects approach) which is not included in the data set.

The Ghana DHS 2014, is structured in such a way that women were nested within households and households were further nested within clusters. Due to the hierarchical nature of this survey, it is very important that a multilevel regression model be used in order to obtain a more accurate and reliable estimates of the model parameters. This modelling approach ensures that between household and cluster variations are properly accounted for in order to avoid parameter over-estimation. In accounting for these variations, enumeration areas referred to as clusters were considered as a level-2 variable while that of respondents or individual-level variables were assigned level-1. This statistical approach was implemented in STATA via a Generalized Structural Equation Modelling (with the logit link function and robust variance estimator for the standard error) approach in the STATA (Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP) software. We used Stata default number of iterations with convergence tolerances log likelihood of 1e^ (− 7). Four different models via nesting were specified and the final interpretation of coefficients were based on the best model among them. The best model was arrived at through the use of the log-likelihood ratio test and the Akaike information criteria. The predictive probabilities that were calculated and presented graphically were obtained using the robust approach to estimate the standard errors with vce (unconditional) option for the margins.

Model building with potential risk factors

The specifications of the models were based on variables that showed significant associations at the bivariate analysis with the Pearson’s chi-squared test statistic. Groupings of these variables were done according to socio-demographic, socio-economic, socio-cultural and psychosocial and other factors. Model-1 constituted our first model containing socio-demographic variables (region, age category and place of residence). Model-2 was formulated using Model-1 in addition to socio-economic factors (respondent’s educational level, wealth index of respondent’s household, respondent’s occupation and partner’s occupation). Model-3 involved Model-2 and socio-cultural factors (respondent’s religious beliefs and ethnicity). Model-3 was nested in Model-4 in addition to psychosocial and other factors (infrequent sex, partner’s opposition to contraceptive use, and fear of side effect). All these models were implemented via the multilevel modelling approach.

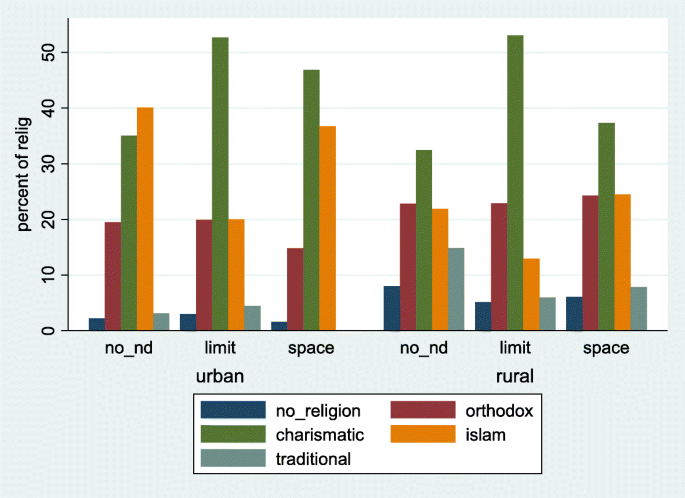

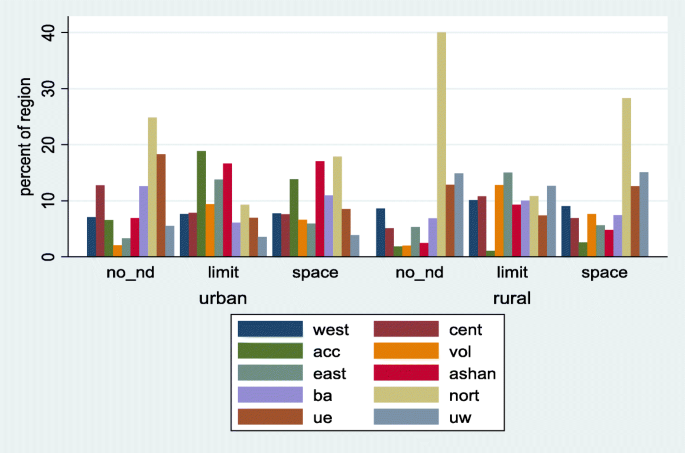

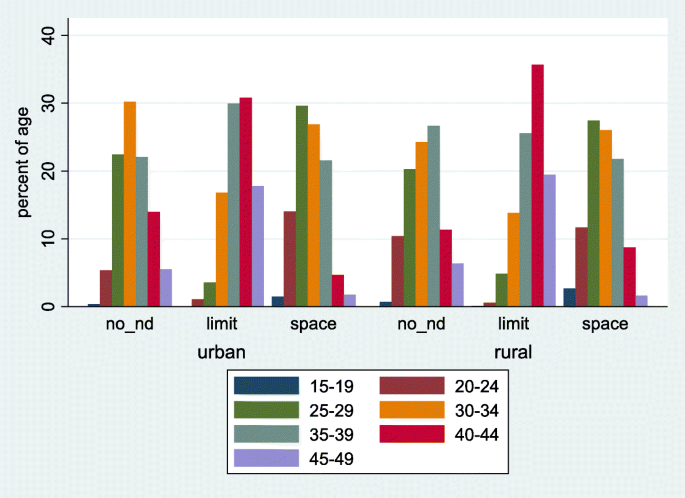

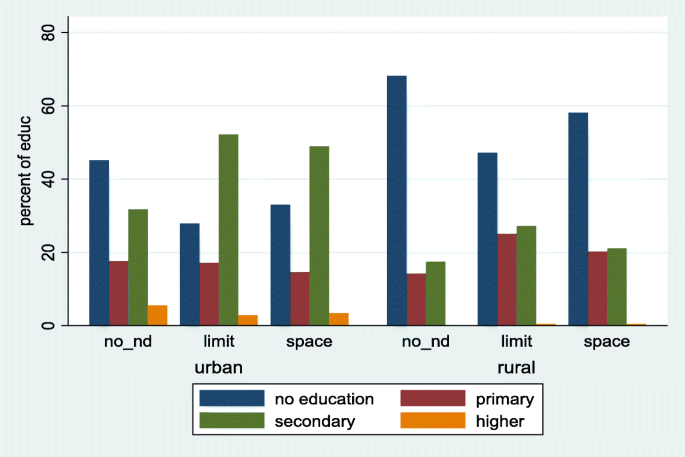

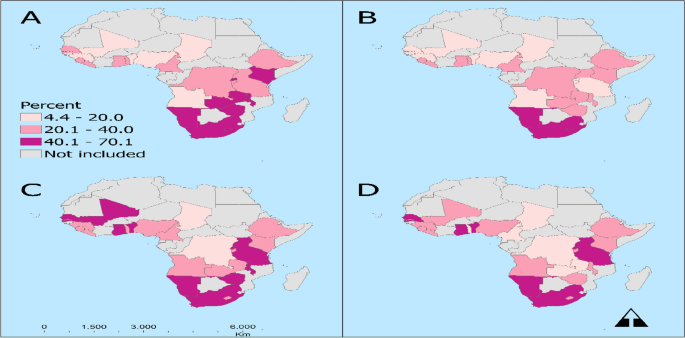

A total of 6503 married/union women met the inclusion criteria for this study. The mean (standard deviation (SD) age in years of the women was 35.27(7.1). Out of the 6503, 1877(28.9%) had no unmet need for family planning, 2918(44.9%) had unmet need for limiting while 1708(26.3%) had unmet need for spacing. The mean (SD) age in years of the respondents with no unmet need was 33.13(6.7) while that for those with unmet need for limiting and spacing were 39.19(5.7) and 30.94(6.1) respectively. Figures 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , depict percentages of the four main variables (religion, region, age category and educational level) that were of primary interest in this study and grouped according to the outcome variable (unmet need for family planning) and further grouped according to place of residence (urban and rural). Majority (40.1%) of the respondents who had no unmet need were of the Islamic religion for urban setting. Those with unmet need for limiting and spacing were of the Charismatic religious belief for both the urban and rural residence. Respondents without any religious background had the least type of unmet need across both residential types.

Distribution of unmet need for family planning among women (married or union) by religion and stratified by place of residence. Ghana Demographic and Health Survey, 2014. Legend: no_nd: no unmet need; limit: unmet need for limiting; space: unmet need for spacing

Distribution of unmet need for family planning among women (married or union) by region and stratified by place of residence. Ghana Demographic and Health Survey, 2014. Legend: no_nd: no unmet need; limit: unmet need for limiting; space: unmet need for spacing

Distribution of unmet need for family planning among women (married or union) by age and stratified by place of residence. Ghana Demographic and Health Survey, 2014. Legend: no_nd: no unmet need; limit: unmet need for limiting; space: unmet need for spacing

Distribution of unmet need for family planning among women (married or union) by education and stratified by place of residence. Ghana Demographic and Health Survey, 2014. Legend: no_nd: no unmet need; limit: unmet need for limiting; space: unmet need for spacing

With respect to regional distribution, majority of those with no unmet need for family planning were from the Northern region of Ghana for both urban (24.9%) and rural (40.1%) areas. Similarly, women in the Northern region had the highest unmet need for spacing for both urban (17.9%) and rural (28.3%) areas. Concerning unmet need for limiting, the Greater Accra region reported the highest (18.8%) for the rural areas while the Eastern region had the highest (15.0%) for the urban areas.

There was a high cluster effect at the multivariable analyses level. There were 8.88 and 3.95 for limiting and spacing respectively, Table 1 . The adjusted relative risk ratio results presented in Table 1 , constitute one out of the four Models specified in the model building subsection, though it contains all the variables in the other sub-models. The final Model was arrived at after calculating the goodness of fit of all the Models using the likelihood ratio test statistic and the Akaike information criteria, as presented in Table S1 (Additional file 1 ). The best model was selected on the basis that it had the lowest value of the Akaike information criteria (AIC). As stipulated in (Additional file 1 : Table S1, the more the significant variables were added to a Model, the better its fit. The Akaike information criteria was 8783.67 for Model-4 with its closest value being 8936.00 for Model-3, indicating that Model-4 is a better fit compared to Model-3, The difference between the two Models was 129.33. The likelihood ratio test for Model 4 compared to Model-3 was 164.33 with a p -value < 0.001, reinforcing the point that Model-4 is a better fit Model. Model-4 was therefore used for the final analysis. The calculated unobserved effect for the best fit Model (Model 4) was 8.88 implying a standard deviation of 2.98 for limiting. That for spacing was 3.95 implying a standard deviation of 1.99. The covariance between limiting and spacing was 2.73, an indication of a weak correlation (0.46) between them. Thus a 1-standard deviation of the random effects amounts to an exp. (2.98) = 19.69 and exp.(1.99) = 7.32 significant change in the relative risk ratio for limiting and spacing. Due to the type of model specified for these analyses, results are reported as relative risk ratios instead of odds ratios as expected if binary logistic regression is used for the analysis.

Demographic determinants of unmet need for family planning

Table 1 , shows both the bivariate and multivariable multinomial mixed effects logistic regression analyses results. Under the socio-demographic grouping approach with the adjusted relative risk ratio, there was a reduced risk of unmet need for limiting against no unmet need. A reduced risk of 99.9% (RR of 0.01 (95% CI, 0.00, 0.03, p -value < 0.001) was observed for people from the Upper West region compared to that of the Volta region. Also, a reduced risk of 88.8% (RR of 0.12 (95% CI, 0.22, 0.60, p -value = 0.01) for respondents from the Eastern region was observed against respondents from the Volta region. Similar observations for unmet need for spacing were made except that the highest relative risk among the ten regions was the Ashanti and Eastern regions for limiting as compared to no unmet need. Though the relative risk for the Upper West region was 0.20(95% CI, 0.05, 0.84, p -value = 0.028) and that of the Eastern region and Ashanti regions were 0.25 (95% CI, 0.07, 0.94, p -value = 0.040) and 0.80 (95% CI, 0.21, 3.12, p -value = 0.750) respectively, only Upper West was significant. This implies that the risk for unmet need for women from the Volta region in relation to those from the Upper West and Eastern regions for limiting were 205 and 9 times higher. That of spacing were 5 and 4 times higher. In terms of the age category, those within 15–19 were used as the reference group. The observations made were that a change in age from lower to higher corresponds to an increase risk of an unmet need for limiting compared to no unmet need. For instance, the risk of women aged 20–24 years had a risk ratio of 1.73 (95% CI, 0.22, 13.34, p -value = 0.600). The risk ratio for age group 35–39 years was 133 (95% CI, 18.12, 977.18, p -value < 0.001). The opposite was the case for all the year groups compared to the 15–19 years respondents for spacing. The risk of respondents aged 20–24 compared to 15–19 when evaluated under unmet need for spacing gave an RR of 0.29 (95% CI, 0.12, 0.71, p -value < 0.007) and that of 35–39 had an RR of 0.17 (95% CI, 0.07, 0.40, p -value < 0.001) times the risk for no unmet need. This shows that respondents within 15–19 years group were 3 and 6 times more likely to develop the need for spacing as against the 20–24 and 35–39 age groups. All the other age groupings were similarly related.

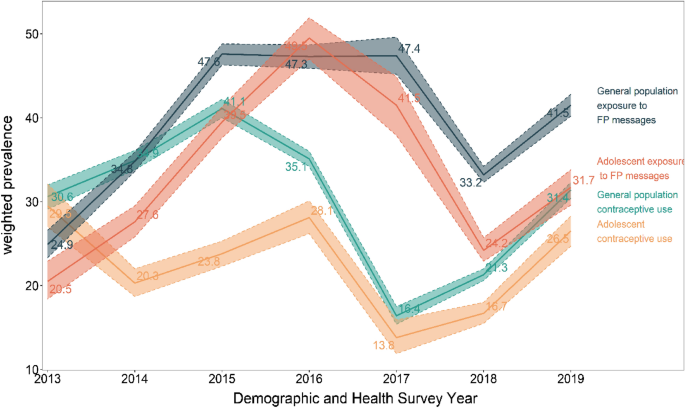

Figure 5 , contains the adjusted predictive probabilities of the types of unmet need for family planning according to regions and age categories of respondents. The marginal predictive probabilities for the unmet need for limiting is highest among respondents from the Volta region (0.80) followed by the Eastern region (0.66) with the smallest being the three regions of the Northern part of the country. For the age category, the marginal probabilities for limiting increased upwardly with a higher age. The predictive probability for wanting to limit was 0.86 for the 45–49 year group and as low as 0.02 among the 15–19 year group.

Adjusted probability of unmet need for family planning (no unmet need: outcome = 0); unmet need for limiting (outcome = 1); unmet need for spacing (outcome = 2)) among women (married or union). Results from a multinomial mixed effect logistic regression model. Ghana Demographic and Health Survey, 2014

Socio-economic determinants of unmet need for family planning

Four socio-economic factors were identified to be statistically significantly associated with unmet need for family planning. These were respondent’s educational level, wealth index of household, respondent’s occupation and partner’s occupation. With respect to wealth index, only the richest and poorer respondents showed a significant difference. The middle and the richer were insignificant statistically when compared to the poorest with regards to unmet need for limiting. Respondents who were poorest have 2 times (95% CI, 1.36, 2.97, p -value < 0.001) the risk of having an unmet need for limiting compared to the poorer respondents. Under spacing, the richest had approximately 32% more risk. The poorer had 89%more risk than the poorest respondents. Educational level did not demonstrate any statistical significant difference for spacing. For limiting, respondents with primary and secondary education had about 2 times the risk with a p -value < 0.001. With regards to respondent’s occupation, those in the services and professionals had an RR of 16.92 times (95% CI, 4.78, 59.97, p -value < 0.001) and 6.06 times (95% CI, 2.05, 17.92, p -value = 0.001) risk of having unmet need for limiting compared with those without any work. The marginal probabilities for educational levels, presented in Fig. 5 , shows that, the predictive probability for respondents classified under primary was the highest (0.47), followed by secondary (0.44) for limiting.

Socio-cultural determinants of unmet need for family planning

Respondents, religion and ethnicity were the only socio-cultural variables statistically significantly associated with unmet need for family planning. Religion was re-categorized into no religion, Orthodox, Charismatic, Islamic and Traditional for further analysis. The results showed that respondents without any religious affiliation had more than twice (with a p -value = 0.002) and 22% (with a p -value = 0.430) the risk of experiencing unmet need for limiting and spacing respectively compared to those with in traditional religion. Unmet need for family planning for the Charismatic group was approximately 3 with a p -value < 0.001 and 1.65 with a p -value < 0.011 times the risk for limiting and spacing than it was for traditional religion. From Fig. 2 , a higher predictive probability (0.46) was observed for respondents without any religious affiliation and those with the Charismatic faith (0.46) for limiting.

Psychosocial and other determinants of unmet need for family planning

All the variables identified under this category were insignificant except those who reported infrequent sex, partner’s opposition to use of contraceptives and respondents fear of side effects. Respondents who fear contraceptive side effects were 3 times (95% CI, 2.28, 3.80 p -value < 0.001) at risk of having unmet need for limiting and 2.58 times (95% CI, 2.05, 3.24, p -value < 0.001) more likely to experience an unmet need for spacing when compared to respondents who do not fear contraceptive side effects. Respondents who had infrequent sex were 4.6 times more likely to want to limit and 2.4 times more likely to space their children than those who had frequent sex.

Making use of the data for women in the reproductive age in the 2014 GDHS, this study used the most appropriate statistical model that has the power to control for unobserved effect estimates in the data set to determine the significant factors associated with unmet need for family planning in Ghana. This knowledge is important for policy makers and service providers to enable them put pragmatic measures in place to satisfy the unmet need for family planning.

Our study showed that a number of socio-demographic (age, religion and administrative region of residence), socio-economic (wealth index, respondents educational level, respondent’s and partner’s occupation), cultural (religion and ethnicity) as well as fear of contraceptive side effects, infrequent sex and opposition from partners were are all significant determinants of both unmet need for limiting and spacing.

Our analysis showed an upward trend of limiting for higher age groups. As women’s age changed from 15 to 19 group to 20–24 group, the likelihood of having an unmet need for FP only doubled but when 15–19 group was compared to 45–49 group, unmet need increased more than a thousand fold. For spacing, the likelihood of an unmet need decreased with an increasing age group. A similar conclusion was arrived at in a study by Wafula et al., in Kenya [ 11 ]. These findings are likely to be due to the fact that young women had not attained their desired family size and therefore their need is to space their children. On the other hand, older women might have attained their desired family size and would therefore not like to have any more children.

Religion was also observed to be a factor leading to having a higher unmet need for family planning as was found in other studies in India and Ethiopia [ 12 , 13 , 14 ]. Compared to those who professed traditional religion, women with no religious affiliation and those with the charismatic faith were twice more likely to have an unmet need for limiting. Women practicing Islamic religion were less likely to space birth compared with those practicing traditional religion. The different religious beliefs have varied perceptions and self-beliefs that could impact either negatively or positively in contraceptive use [ 11 ]. Members of Islamic religion and some Orthodox religions such as Catholics exhibit a strong opposition to contraceptive use. Overall, women who belonged to other religious beliefs other than traditional religion appeared to have a higher unmet need for limiting and spacing as compared to respondents who belonged to the traditional religion [ 11 ].

With regards to education, this study revealed a higher unmet need for both limiting and spacing among respondents who had completed either primary or secondary education compared to those without any formal education; similar conclusions were drawn from other studies [ 15 , 16 ]. A non-significant effect between higher and no educated respondents were observed and this is contrary to findings from Kenya [ 11 ]. They observed a higher unmet need for women with low educational background. The high unmet need for family planning in educated Ghanaian women may explain why induced abortion tends to be higher in them as compared to women with no education [ 17 , 18 ]. It has been suggested that induced abortion may be an integral factor in the control of fertility among educated Ghanaian women [ 17 ]. It is also possible that highly educated women may have knowledge about potential contraceptives side effects which may translate into low use among this demographic group. It was further observed that place of residence was a statistically insignificant contributor to unmet need for family planning, though rural residents were less likely to have an unmet need. This finding is again contrary to findings of Genet et al., in Ethiopia [ 19 ], which stipulated that rural respondents were twice more likely to have unmet need. There are a number of possibilities that could have influenced our findings. Family planning services have also been an integral part of health services provided in rural areas in Ghana and this high level of awareness created in these areas may have had positive impact on FP.

Our study has also shown that, the fear of side effects, infrequent sexual intercourse and opposition from partners are all significant factors contributing to the high unmet need for family planning in Ghana. Similarly, demographic and health surveys from 52 countries spanning the period from 2005 to 2014 have shown that about 7 out of 10 married women with unmet need for family planning cite either fear of side effects or health risks, infrequent or no sex and opposition to contraception (either by they themselves or from significant others) as their reason for not using modern contraception [ 20 ]. This is an indication that satisfying the needs of women with unmet need for family planning will get a big boost if these factors are tackled with the seriousness they deserve.

In many countries contraceptive prevalence have stalled and this has been attributed partly to the poor quality of counselling and hence the call for new approaches to counselling [ 21 ]. Good counselling should pay attention to dealing with misconceptions, how to prepare new clients to handle common side effects and also how continuing clients can cope with side effects [ 22 ].

A recent study from five urban family planning centres in Ghana revealed that even though over two thirds of women adopting a family planning methods were counselled to expect side effects, over a third of these same women were not counselled on common side effects of their chosen methods [ 23 ]. In the same study, about 7 out of 10 family planning acceptors chose methods whose side effects they had stated earlier will cause them to stop the said method. This shows that much importance was not attached to side effects of clients before they were given their chosen methods. In addition, women wary of side effects could also be educated on natural FP methods which they may not be familiar with. Studies have shown that mobile application for contraception based on a woman’s natural cycle is effective in preventing pregnancies [ 24 ]. Such tools on fertility-awareness may be the solution for women for whom side effects are positive predictors of unmet needs on limiting and spacing [ 23 , 24 ]. Quality of family planning services which includes, good counselling is associated with clients selecting family planning methods that best suits their individual needs. This will enable them navigate through side effects effectively and to continue to use their choice of methods [ 25 ].

Respondents who had infrequent sexual intercourse were about four and two times more likely to have an unmet need for limiting and spacing respectively. It is possible that women who had infrequent sexual intercourse may not want to be to be using a method continuously when they do not know when they next will have sexual intercourse. They are however at risk of unintended pregnancies and need to be abreast with emergency contraception and barrier methods in order to avoid unintended pregnancies.

For those whose partners oppose their contraceptive use, there will be the need to get them involved in order for them to appreciate the benefits of family planning. Some men have the wrong impression that their spouses may become promiscuous once they are using contraceptives [ 26 ].

While acknowledging that factors such as level of education, wealth index and religion will require multi-sectoral approach to handle, dealing with side effects, getting women with infrequent sex to use emergency contraception or barrier methods, and educating partners on the benefits of family planning lies mostly in the domain of service providers. There is the need to start dealing with the high unmet need for family planning by tackling these three factors first.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study derives its strengths from the fact that, the use of a nationally representative sample allows for the generalizability of study findings to the whole country. In addition, demographic and health surveys are well planned and executed surveys and therefore the data is usually of high quality. Furthermore, the number of observations with complete dataset that met the inclusion criteria was large. The use of the multilevel mixed effects logistic model addresses the issues of cluster variations by appropriately accounting for those unobserved effects that are not usually measured by the dataset. The coefficient estimates obtained in this study are more accurate and generalizable due to our modelling approach.

This study also had some limitations. To begin with, the data was obtained through a cross-sectional study and so causations could not be established. Secondly, there were delays in model convergence due to the complex nature of the model proposed and applied to the dataset but that did not have an effect on the parameters estimates. The survey obtained retrospective information which was self-reported from participants spanning a 5-year period prior to the survey and so the likelihood of recall bias was high. Recall bias has some consequences on coefficient estimates and overall significant testing and so interpretations/use of the results should be done cautiously.

This study reveals that socio-demographic factors such as respondents region, age and not place of residence contribute to predicting unmet need for family planning. Also, socio-economic (partner’s occupation) and cultural (religion and ethnicity) as well as side effects are all significant determinants of both unmet need for limiting and spacing. Variables such as, educational level, wealth index and respondents occupation overall were significant in predicting only unmet need for limiting but insignificant for predicting unmet need for spacing. The fear of side effect on the use of contraceptives as well as infrequent sex among respondents are both high predictors of unmet need for family planning. Overall, fear of side effect, infrequent sex, age, ethnicity, partner’s education and region were the most highly significant predictors of both limiting and spacing. The Ministry of Health need to work more closely with the Ghana Health Service to train its service providers to ensure that prospective family planning acceptors are counselled adequately on common side effects of their methods of choice and to also address misconceptions. All stakeholders in family planning must do their best to extol the virtues of family planning to men and help involve them in family planning.

Abbreviations

Confidence Interval

Exponential

Family Planning

Ghana Demographic Health Survey

Intrauterine Device

Campbell M, Cleland J, Ezeh A, Prata N. Return of the population growth factor. Science. 2007;315(5818):1501.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Sinding SW. Population, poverty and economic development. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Ser B Biol Sci. 2009;364(1532):3023–30.

Google Scholar

Westoff CF. The potential demand for family planning: a new measure of unmet need and estimates for five Latin American countries. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 1988;14(2):45–53.

Der E, Moyer C, Gyasi R, Akosa A, Tettey Y, Akakpo P, Blankson A, Anim J. Pregnancy related causes of deaths in Ghana: a 5-year retrospective study. Ghana Med J. 2013;47(4):158.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Longwe A, Huisman J, Smits J. Effects of knowledge, acceptance and use of contraceptives on household wealth in 26 African countries, Nijmegen Center for Economics working paper; 2013. p. 12–109.

Sedgh G, Hussain R, Bankole A, Singh S. Women with an unmet need for contraception in developing countries and their reasons for not using a method, Occasional report, vol. 37; 2007. p. 5–40.

Ghana Statistical Service (GSS), Ghana Health Service (GHS), and ICF Macro. Accra: Ghana Demographic and Health Survey 2008, 2009.

Apanga PA, Adam MA. Factors influencing the uptake of family planning services in the Talensi District, Ghana. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;20:10. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2015.20.10.5301 .

Bongaarts J. United nations department of economic and social affairs, population division world mortality report 2005. Popul Dev Rev. 2006;32(3):594–6.

Bradley SE, Croft TN, Fishel JD, Westoff CF. Revising unmet need for family planning; 2012.

Wafula SW. Regional differences in unmet need for contraception in Kenya: insights from survey data. BMC Womens Health. 2015;15(1):86.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Barman S. Socio-economic and demographic determinants of unmet need for family planning in India and its consequences. J Res Humanit Soc Sci. 2013;3(3):62–75.

Gebre G, Birhan N, Gebreslasie K. Prevalence and factors associated with unmet need for family planning among the currently married reproductive age women in Shire-Enda-Slassie, northern west of Tigray, Ethiopia 2015: a community based cross-sectional study. Pan Afr Med J. 2016;23:195. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2016.23.195.8386 .

Westoff CF, Bankole A. Unmet need: 1990–1994; 1995.

Kumar A, Bhardwaj P, Srivastava J, Gupta P. A study on family planning practices and methods among women of urban slums of Lucknow city. Indian J Community Health. 2011;23(2):75–7.

Mekonnen W, Worku A. Determinants of low family planning use and high unmet need in Butajira District, South Central Ethiopia. Reprod Health. 2011;8(1):37.

Geelhoed DW, Nayembil D, Asare K, Van Leeuwen J, Van Roosmalen J. Contraception and induced abortion in rural Ghana. Tropical Med Int Health. 2002;7(8):708–16.

CAS Google Scholar

Ahiadeke C. Incidence of induced abortion in southern Ghana. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2001:27(2):96–101 & 108.

Genet E, Abeje G, Ejigu T. Determinants of unmet need for family planning among currently married women in Dangila town administration, Awi zone, Amhara regional state; a cross sectional study. Reprod Health. 2015;12(1):42.

Sedgh G, Ashoford LS, Hussain R. Unmet need for contraception in developing countries: examining women’s reasons for not using a method, New york: Guttmacher Institute; 2016. http://www.guttmacher.org/report/unmet-need-for-contraception-in-developing-countries .

Berglund Scherwitzl E, Lindén Hirschberg A, Scherwitzl R. Identification and prediction of the fertile window using NaturalCycles. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2015;20(5):403–8.

PubMed Google Scholar

Alam M-E, Bradley J, Shabnam F. IUD use and discontinuation in Bangladesh. E&R study# 8. New York: Engender Health/The ACQUIRE Project; 2007.

Rominski SD, Morhe ES, Maya E, Manu A, Dalton VK. Comparing Women's contraceptive preferences with their choices in 5 urban family planning clinics in Ghana. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2017;5(1):65–74.

Berglund Scherwitzl E, Gemzell Danielsson K, Sellberg JA, Scherwitzl R. Fertility awareness-based mobile application for contraception. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2016;21(3):234–41.

Heerey M, Merritt AP, Kols AJ. Improving the quality of care. Quality improvement projects from the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health Center for Communication Programs; 2003.

Kabagenyi A, Jennings L, Reid A, Nalwadda G, Ntozi J, Atuyambe L. Barriers to male involvement in contraceptive uptake and reproductive health services: a qualitative study of men and women’s perceptions in two rural districts in Uganda. Reprod Health. 2014;11(1):21.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

The authors did not obtain any funding for this research.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the Ghana demographic and health repository, http://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm .

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Biostatistics, School of Public Health, University of Ghana, Legon, Accra, Ghana

Chris Guure, Samuel Dery, Baaba da-Costa Vrom & Alfred Yawson

Department of Population, Family and Reproductive Health, School of Public Health, University of Ghana, Legon, Accra, Ghana

Ernest Tei Maya

Department of Mathematical Sciences, Faculty of Science, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Refah M. Alotaibi & Hoda Ragab Rezk

Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Hoda Ragab Rezk

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

CG and SD conceptualized the present study. CG led the data extraction and analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. ETM contributed in the write-up of the different sections of the manuscript. CG, ETM, SD, BDV, RMA, HRR and AY reviewed the draft manuscript and contributed to the final version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript before submission.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ernest Tei Maya .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The Ghana Health Service Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the study protocol, survey instruments and materials prior to the commencement of the surveys. Individual consent was also obtained during the data collection process. An application requesting for the use of the 2014 Ghana Demographic and Health Survey data was sent to the Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) representative. Data was then used after approval was obtained.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:.

Table S1. Model building strategy: unmet need for family planning among women (married or union), Ghana Demographic and Health Survey, 2014. (DOCX 27 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Guure, C., Maya, E.T., Dery, S. et al. Factors influencing unmet need for family planning among Ghanaian married/union women: a multinomial mixed effects logistic regression modelling approach. Arch Public Health 77 , 11 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-019-0340-6

Download citation

Received : 28 June 2018

Accepted : 20 February 2019

Published : 12 March 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-019-0340-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Family planning

- Estimating unobserved effects

- Multilevel modelling

Archives of Public Health

ISSN: 2049-3258

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Factors influencing the uptake of family planning services in the Talensi District, Ghana

Affiliation.

- 1 Ghana Health Service, Talensi district, Upper East Region, Ghana.

- PMID: 25995807

- PMCID: PMC4430143

- DOI: 10.11604/pamj.2015.20.10.5301

Introduction: Usage of family planning services in developing countries have been found to avert unintended pregnancies, reduce maternal and child mortality, however, it's usage still remains low. Hence, the objective of this study was to investigate the factors that influence the decision of women in fertility age to go for family planning services.

Methods: This was a descriptive cross-sectional study conducted in Talensi district in the Upper East Region of Ghana. Systematic random sampling was used to recruit 280 residents aged 15-49 years and data was analysed using SPSS version 21.0.

Results: The study revealed that 89% (249/280), of respondents were aware of family planning services, 18% (50/280) of respondents had used family planning services in the past. Parity and educational level of respondents were positively associated with usage of family planning services (P<0.05). Major motivating factors to the usage of family planning service were to space children, 94% (47/50) and to prevent pregnancy and sexual transmitted infections 84% (42/50). Major reasons for not accessing family planning services were opposition from husbands, 90% (207/230) and misconceptions about family planning, 83% (191/230).

Conclusion: Although most women were aware of family planning services in the Talensi district, the uptake of the service was low. Thus, there is the need for the office of the district health directorate to intensify health education on the benefits of family planning with male involvement. The government should also scale up family planning services in the district to make it more accessible.

Keywords: Family planning; Ghana; Talensi district; contraceptives; uptake.

- Contraception Behavior / statistics & numerical data

- Cross-Sectional Studies

- Family Planning Services / statistics & numerical data*

- Ghana / epidemiology

- Health Knowledge, Attitudes, Practice

- Middle Aged

- Socioeconomic Factors

- Surveys and Questionnaires

- Young Adult

- Open access

- Published: 23 January 2021

Towards achieving the family planning targets in the African region: a rapid review of task sharing policies

- Leopold Ouedraogo ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5842-1842 1 ,

- Desire Habonimana ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0832-5558 2 ,

- Triphonie Nkurunziza 1 ,

- Asmani Chilanga 3 ,

- Elamin Hayfa 4 ,

- Tall Fatim 3 ,

- Nancy Kidula 4 ,

- Ghislaine Conombo 5 ,

- Assumpta Muriithi 1 &

- Pamela Onyiah 1

Reproductive Health volume 18 , Article number: 22 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

6925 Accesses

14 Citations

Metrics details

Expanding access and use of effective contraception is important in achieving universal access to reproductive healthcare services, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), such as those in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Shortage of trained healthcare providers is an important contributor to increased unmet need for contraception in SSA. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends task sharing as an important strategy to improve access to sexual and reproductive healthcare services by addressing shortage of healthcare providers. This study explores the status, successes, challenges and impacts of the implementation of task sharing for family planning in five SSA countries. This evidence is aimed at promoting the implementation and scale-up of task sharing programmes in SSA countries by WHO.

Methodology and findings

We employed a rapid programme review (RPR) methodology to generate evidence on task sharing for family planning programmes from five SSA countries namely, Burkina Faso, Cote d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Ghana, and Nigeria. This involved a desk review of country task sharing policy documents, implementation plans and guidelines, annual sexual and reproductive health programme reports, WHO regional meeting reports on task sharing for family planning; and information from key informants on country background, intervention packages, impact, enablers, challenges and ways forward on task sharing for family planning. The findings indicate mainly the involvement of community health workers, midwives and nurses in the task sharing programmes with training in provision of contraceptive pills and long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARC). Results indicate an increase in family planning indicators during the task shifting implementation period. For instance, injectable contraceptive use increased more than threefold within six months in Burkina Faso; contraceptive prevalence rate doubled with declines in total fertility and unmet need for contraception in Ethiopia; and uptake of LARC increased in Ghana and Nigeria. Some barriers to successful implementation include poor retention of lower cadre providers, inadequate documentation, and poor data systems.

Conclusions

Task sharing plays a role in increasing contraceptive uptake and holds promise in promoting universal access to family planning in the SSA region. Evidence from this RPR is helpful in elaborating country policies and scale-up of task sharing for family planning programmes.

Introduction

L'élargissement de l'accès et de l'utilisation d’une contraception efficace est important pour parvenir à l'accès universel aux services de santé reproductive, en particulier dans les pays à revenu faible et intermédiaire, comme ceux de l'Afrique subsaharienne. L’insuffisance de prestataires de soins de santé qualifiés est un facteur important de l'augmentation des besoins non satisfaits en matière de contraception en Afrique subsaharienne. L'Organisation mondiale de la Santé (OMS) recommande le partage des tâches comme stratégie importante pour améliorer l'accès aux services de santé sexuelle et reproductive en s’attaquant à la pénurie des prestataires de soins de santé. Cette étude explore l'état des lieux, les réussites, les défis et les impacts de la mise en œuvre du partage des tâches pour la planification familiale dans cinq pays d'Afrique subsaharienne. Ces données factuelles visent à promouvoir la mise en œuvre et l'extension des programmes de partage des tâches dans les pays d'Afrique sub-saharienne par l'OMS.

Méthodologie et résultats

Nous avons utilisé la méthodologie de la revue rapide des programmes (RPR) pour générer des données sur le partage des tâches pour les programmes de planification familiale de cinq pays d'Afrique subsaharienne, à savoir le Burkina Faso, la Côte d'Ivoire, l'Éthiopie, le Ghana et le Nigéria. Cela impliquait la revue documentaire des documents de politique nationale de partage des tâches, des plans de mise en œuvre et des directives, des rapports annuels sur les programmes de santé sexuelle et reproductive, des rapports des réunions régionales de l'OMS sur le partage des tâches pour la planification familiale; et des informations provenant des informateurs clés sur le contexte du pays, les programmes d'intervention, l'impact, les catalyseurs, les défis et les voies à suivre pour le partage des tâches pour la planification familiale. Les résultats indiquent principalement l'implication des agents de santé communautaires, des sages-femmes et des infirmières dans les programmes de partage des tâches avec une formation liée à l’approvisionnement de pilules contraceptives et de contraceptifs réversibles à longue durée d’action (LARC). Les résultats indiquent une augmentation des indicateurs de planification familiale pendant la période de mise en œuvre du partage des tâches. Par exemple, l'utilisation des contraceptifs injectables a plus que triplé en six mois au Burkina Faso; le taux de prévalence de la contraception a doublé avec une baisse de la fécondité totale et des besoins non satisfaits en matière de contraception en Éthiopie; et l'adoption du LARC a augmenté au Ghana et au Nigéria. Certains obstacles à la réussite de la mise en œuvre comprennent une faible rétention des prestataires de niveau inférieur, une documentation inadéquate et des systèmes peu performants de gestion des données.

Le partage des tâches joue un rôle important dans l'augmentation de l'utilisation de la contraception et dans la promotion de l'accès universel à la planification familiale dans la région Afrique subsaharienne. Les données de ce RPR sont utiles pour l'élaboration des politiques nationales et l'intensification du partage des tâches pour les programmes de planification familiale.

Plain English summary

Correct and consistent use of contraceptives has been shown to reduce pregnancy and childbirth related maternal deaths and generally improve reproductive health. However, statistics show that many women of reproductive age in SSA who ought to be using contraceptives are not using them. As a result, high rates of maternal deaths from pregnancy or childbirth-related complications have been recorded in the region. One of the key barriers to accessing family planning in SSA is the shortage of healthcare providers. To address this problem, WHO recommends task sharing as an intervention to improve access and use of sexual and reproductive health services including family planning. While task sharing guidelines have been developed and disseminated in many SSA countries, limited evidence exists on their adoption, implementation and outcomes to promote scale-up. This study undertook a rapid programme review of evidence from policy documents, implementation plans and guidelines, annual sexual and reproductive health programme reports, regional meeting reports and key stakeholder reports on task sharing to explore the status, successes, challenges and impacts of the implementation of task sharing for family planning in five SSA countries: Burkina Faso, Cote d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Ghana, and Nigeria. We found that task sharing programmes mainly involved community health workers, midwives and nurses. The intervention led to increased modern contraception access and use and general improvement in family planning indicators during the implementation periods. Some barriers to successful implementation of task sharing include poor retention of lower cadre providers, inadequate documentation, and poor data systems.

Peer Review reports

The World Bank projects a ten-fold increase in the population of sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) between 1960 and 2050, reaching 9.7 billion people in 2050 [ 1 ]. This escalation indicates Africa’s growing fertility rate [ 2 ]. Notably, while the global fertility rate between 1990 and 2019 fell from 3.2 to 2.5 births per woman, this indicator only dropped from 6.3 to 4.6 births per woman for SSA [ 2 ]. Evidently, other regions have recorded much higher declines compared to SSA (from 4.5 to 3.4 in Oceania, from 4.4 to 2.9 in Northern Africa and Western Asia, from 3.3 to 2.0 in Latin America and the Caribbean, and from 2.5 to 1.8 in Eastern and South-Eastern Asia) [ 2 ]. This decline in fertility rate continues to occur at a much slower pace in SSA as compared to the rest of the world. In other words, while it took 19 years for fertility rates in Northern Africa and Western Asia to drop from 6 to 4 births per woman (1974 to 1993), a similar decline is expected to materialise after 34 years (1995 to 2029) in SSA [ 2 ]. With weak health systems present in fragile economies, the higher fertility rates present greater risks of unpropitious pregnancy outcomes in SSA countries [ 3 , 4 , 5 ].

In the light of the evidence above, a wealth of literature has established a correlation between higher fertility rates, poverty and pregnancy-related deaths/complications. For instance, of some 830 women who die daily from pregnancy or childbirth-related complications around the world, 99% of such deaths occur in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) [ 6 ]. It is also estimated that of the 2.6 million stillbirths that occurred globally in 2015, 98% were in LMICs [ 7 ]. Furthermore, the risk of a woman in a LMIC dying from a maternal-related cause during her lifetime is about 33 times higher compared to her counterpart in a high-income country [ 8 ]. Fortunately, interventions such as modern contraception which space and limit pregnancies significantly improve the overall health of women of reproductive age [ 9 ]. Although this remains true, SSA continues to register higher proportions of unmet contraception expectations to date [ 10 , 11 ].

In SSA, 16% of women of reproductive age who desire to either terminate or postpone childbearing do not currently use a contraceptive method [ 12 ]. Most importantly, in this region, the rate of unmet needs for family planning is about 21% among married women or those living in union [ 12 ]. Such trends represent barriers to the achievement of universal access to sexual and reproductive healthcare services including for family planning by 2030 in SSA, as stipulated in the third and fifth Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) targets: 3.1, 3.7, 3.8, and 5.6 [ 13 , 14 ]. One of the key barriers to the availability and accessibility of family planning services in sub-Saharan Africa is the critical dearth of qualified health care providers. On the one hand, while reaffirming that human resources is at the core of each health care system around the world, the health workforce remains inequitably distributed in most sub-Saharan African countries, with rural areas suffering chronic and severe shortages of competent health care providers [ 15 , 16 ]. On the other hand, lack of motivation and absenteeism of health care providers in impoverished countries widens the gap in quality family planning services [ 17 ]. In the bid to assuage human resource shortages, many countries have started to train less experienced health workers perform tasks that should otherwise be performed by qualified doctors or other highly-trained healthcare workers [ 18 ].

The World Health Organization (WHO), like many other stakeholders, recognise task sharing as a promising strategy to address the serious lack of health care workers to provide reproductive, maternal and new-born care in less wealthy countries [ 19 , 20 , 21 ]. By definition, task sharing involves the safe expansion of tasks and procedures that are usually performed by higher-level staff (i.e. physicians) to lay- and mid-level healthcare professionals (i.e. midwives, nurses, and auxiliaries) [ 22 ]. In the same perspective, WHO recommends that midwives be empowered to provide all family planning services except tubal ligation and vasectomy (Box 1 ). Also, initiation and maintenance of injectable contraceptives (standard syringe) can be performed by auxiliary nurses. Following WHO recommendations on “Optimizing the roles of health personnel through the delegation of tasks to improve access to maternal and new-born health interventions” (2012), regions including the Regional Office for Africa have started to mobilise local efforts with an aim to initiate and expand task sharing policies for family planning across respective member countries.

For the above reason, WHO Regional Office for Africa, in partnership with member countries and other key players such as the Ouagadougou Partnership for Family Planning Coordination Unit (UCPO), the West Africa Health Organisation (WAHO), and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), organized a regional consultation meeting on task sharing in September 2016 with the aim of aiding nine pilot countries in developing action plans for the implementation of task sharing recommendations. Moreover, WHO Regional Office for Africa conducted an intensive advocacy which yielded a special resolution relating to task sharing for family planning endorsed by governments of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) region. In December 2019, a second regional advocacy meeting was held to expand the task sharing policies to an additional 11 English-speaking countries.

Four years after the first advocacy meeting, this paper explores the lessons learnt in relation to task sharing for family planning in five countries in the WHO African region. Specifically, the paper documents the status of task sharing for family planning policy implementation, its effect in coverage and use of family planning services, gauges key achievements, enablers and challenges to form a basis for the implementation monitoring and planning of task sharing initiatives for family planning in the region.

Box 1 Table of guideline recommendations for task sharing of contraception

The study applied the Rapid Programme Review (RPR) methodology to generate evidence on what WHO Regional Office for Africa and member countries can do to build on successes and tackle challenges with an aim to scale-up task sharing programmes for family planning region-wide. A rapid review is a knowledge synthesis method in which components of the systematic review process are simplified or omitted to produce information in a short period of time [ 23 ]. A RPR focuses on synthesizing information regarding a programme (task sharing programme for family planning in this case) through desk-review of programme documents, reports and key stakeholder information. The RPR methodology generates strong evidence and saves both time and costs, rather than conducting full programme reviews which are time-consuming and effort-intensive [ 24 ]. The method allows a rapid and progressive learning with conscious exploration and flexible use of methods without following a blueprint programme [ 25 ]. The review triangulated data from secondary sources with information from key informants in four countries which have already piloted the task sharing programmes for family planning. A trend analysis was done alongside an overview of system-level implementation enablers and barriers to successful implementation of task sharing programmes in the African context.

Data collection

Data was collected in two steps. In the first instance, data for the RPR were obtained through a desk review of country task sharing for family planning policy documents, relevant implementation plans and guidelines, and annual sexual and reproductive health programme reports. In addition, data presented during the second Africa regional meeting on task sharing for family planning organised by WHO Regional Office for Africa was exploited to supplement document reviews. During this meeting, five countries which are piloting or implementing programmes on task sharing for family planning (Burkina Faso, Cote d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Ghana, and Nigeria) presented success stories as well as challenges, lessons learnt and ways forward. A full list of countries that participated in the meeting is provided in Box 2 .

In the second instance, WHO country offices were contacted to identify and obtain key informants on task sharing for family planning programmes in the five aforementioned countries. Through written communication (electronic mails), National Focal Points (NFPs) on sexual and reproductive health provided information on the country background, intervention packages, intervention impact, system-level enablers and challenges, and information on ways forward.

The country background helped to understand the baseline picture. Specifically, we collected information on the date when the first task sharing programme was piloted, the rollout process and, most importantly, the significant baseline family planning indicators. A list of full family planning indicators for Burkina Faso before (2010) and after (2019) implementation of the task sharing for family planning programme is shown in Table 1 . Secondly, data on the type of task sharing intervention packages were collected. In addition, geographical reach and the type of tasks and healthcare professionals involved were documented. If available and applicable, an illustrative picture was also shared to demonstrate lay- and auxiliary-level cadres performing family planning tasks previously performed by higher healthcare professionals. Thirdly, we used Table 1 and collected data on key family planning indicators during the period of implementation of task sharing for family planning. Given the availability of enough data-points, baseline and midterm data were used to trace an indicator trend line. We also documented system-level levers and challenges that played an important role in the successful/unsuccessful implementation of task sharing programmes. This information is necessary for policymakers amid the aim by WHO Regional Office for Africa and member states of rolling-out and expanding task sharing for family planning programmes region-wide. Lastly, each country provided information on the next steps with concrete actions to be undertaken in the near future with regards to task sharing for family planning.

Box 2. List of countries that participated to the WHO regional meeting on task sharing for family planning, 16–19 December 2019

Burkina Faso*

Cote d’Ivoire*

South Africa

* Countries piloting or implementing programmes on task sharing for family planning

Data analysis

Data was analysed in two steps. Step one consisted of compiling information from the country background, the task sharing intervention packages, the system-level enablers and challenges, and the ways forward. All data sources were verified to ensure reliability of reported information. In the event of missing data, a request was resent to the respective NFP who was asked to provide feedback within two weeks. Beyond a period of two weeks, the data was confirmed as “missing information”. For example, Cote d’Ivoire was excluded from analysis due to substantial missing data. Step Two consisted of a trend analysis of key family planning indicators. Owing to the limited number of data-points (often only two data-points), a trend line was only possible for Ghana and Nigeria. For Burkina Faso and Ethiopia, we compared proportions before and during task sharing interventions.

Results are mainly presented as text boxes of country overviews. In each box, we summarised findings on the country background, described existing task sharing intervention packages, quantified midterm programme impact, analysed system-level enablers and barriers, and suggested ways forward.

Box 3. Burkina Faso

Burkina Faso is a West African country struggling with severe health workforce shortages [ 26 ]. On average there is less than one physician per 10,000 people and 2.39 midwives per 10,000 people [ 27 ]. This is way lesser than the WHO doctor-population ratio of 1:1000. Burkina Faso piloted the first task sharing programme between 2015 and 2016 across 17,688 villages in the Hauts Bassin region, Boucle de Mouhoun region, Central West region, and Central region. Each participating village received two community health workers (CHWs) trained to provide injectable contraception (Sayana press) in addition to contraceptive pills. Task sharing was also piloted at health facility level where midwives were trained to perform long acting reversible contraception (LARC) procedures—the intrauterine contraceptive device (IUCD) and implants. Evaluation of the pilot programme yielded promising results, leading to the validation and nationwide rollout of the task sharing programme in November 2017.

Task sharing intervention packages

CHWs and midwives received comprehensive specific training needed for performing new family planning tasks. The training was provided by the Ministry of Health. There were also adequate post-training follow-up and monitoring of the health workers. Furthermore, in addition to an effective supply chain of services, mechanisms for quality control were put in place. Additionally, advocacy meetings and community mass mobilisation campaigns were regularly conducted. Joint-field monitoring and evaluation missions were conducted to enable an early detection of potential enabling factors and challenges that affect the successful programme implementation. Results were disseminated through regional and sub-regional meetings in Burkina Faso, Ghana, Kenya, and Cote d’Ivoire.

Partial results showed an increase in new users. For instance, within a period of six months (February to September 2017) during the implementation of task sharing for family planning by trained CHWs and midwives, a total 1225 implants—of which 857 were new users—were administered. A total of 384 IUCDs, of which 238 were new users, were provided by newly trained midwives. In the same period, CHWs provided 3541 injectable contraceptives (Medroxyprogesterone acetate)—of which 1013 were new users— and 1257 contraceptive pills, of which 241 were new users. Other family planning indicators are presented in Table 1 .

It stood out that the strong commitment and stewardship of health authorities from the top to the bottom levels, the expansion of contraceptive options, the community involvement, and the improved financial and geographic accessibility of family planning services played an important facilitating role.

Notable challenges included data reporting, as routine paper-based reporting system was solely used, and financial constraints. Also, the programme was fraught with insufficient funding causing great irregularities in the payment of CHWs incentives. Evidence has confirmed that such a financial challenge has potential for reducing provider motivation [ 28 , 29 ].

Ways forward

A commitment maker since 2012 and a member of both the Ouagadougou Partnership and SWEDD (Sahel Women’s Empowerment and Demographic Dividend project), Burkina Faso has taken its FP2020 commitment seriously through its 2017–2020 RH/FP strategy, which incorporates task sharing for family planning [ 30 ]. Burkina Faso vowed to build on successes to strengthen task sharing programmes through the recruitment and training of lay- and auxiliary-level healthcare providers by the Ministry of Health. Furthermore, there is a robust financial pledge and advocacy from political and administrative authorities, technical and financial partners and non-governmental associations working in the field of family planning.

On the one hand, time comparison shows an increase in the number of women of reproductive age and that of expected and real pregnancies. On the other hand, there has been a decrease in fertility rate and maternal mortality ratio. Overall, Burkina Faso showed promising results for family planning services. Key improvement features of family planning include an increase in contraceptive prevalence which more than doubled (105% increase), the increase in numbers of couples using a contraceptive method which nearly tripled (183% increase), and an increase in family planning expenditures. Moreover, in 2019, family planning averted 11.56% of expected pregnancies (comparison of expected and real pregnancies in 2019).

Box 4. Ethiopia

Ethiopia has a total population of 100 million people of whom 83.6% live in rural areas [ 31 ]. Majority of Ethiopia’s population is made up of young people, with 45% representing those under 15 years old and 71% under 30 years old [ 32 ]. Women of reproductive age account for 24% of Ethiopia’s population [ 31 ]. Each year, Ethiopia expects a total number of 3 million pregnancies. The country’s population growth rate is 2.6% per year and the total fertility rate is 2.3 births per woman in urban settings and 5.2 births in rural areas [ 31 ].

In Ethiopia, the task sharing programme was piloted in three different phases. Phase one involved the Implanon programme which was first piloted in 8 districts in 2009. Provision of Implanon was shifted from healthcare facility level to community level. Phase Two, which started in 2011, was the IUCD task sharing programme which was piloted in one region where the device was inserted and removed by midwives and nurses rather than physicians. Phase Three was where the IUCD provision was further lowered to auxiliary nurses in 2016 across 66 selected health posts.

Within a period of 12 months (from July 2018 to June 2019), 1.43 million clients received a LARC method (1,362,149 women received Implanon and 64,073 women received IUCD). Moreover, contraceptive prevalence rate has doubled every five years from 2000 (CPR = 6.1%) to 2019 (CPR = 41%). Another supporting point is the decline in total fertility rate which fell from 6.0 to 4.6 in the same period. Similarly, unmet contraceptive needs were higher in 2011 (25.3% of unmet contraceptive needs) as compared to 2019 (22% of unmet contraceptive needs). Equally important, IUCD utilization rate increased from less than 2% in 2011 to more than 11% in 2019.

The successful implementation of Ethiopia’s task sharing pilot programme was a result of political commitment. There has been a visible political will and support by the Government of Ethiopia. Specifically, the Government signed international family planning policies, elaborated national policies and strategies in support of the implementation of family planning standards, promoted and stimulated demand for family planning services, and continuously increased the overall health budget over the past decade.

Key challenges included lack of awareness and misconceptions regarding some contraception methods such as long-acting family planning (LAFP) methods among the target population, shortages of medical equipment and logistics, poor infrastructure (electricity, water, and roads), and poor mentorship and supporting supervision.

Looking ahead, Ethiopia aims to accelerate strategies to increase the demand for family planning services until the very remote communities, to enhance service availability and accessibility, to improve provider competency and performance, and to strengthen mentorship and supportive supervision. Ethiopia has committed to the FP2020 call to action that urges global health and development partners to adopt task sharing as a key solution for increasing access to contraception [ 33 ].

Box 5. Ghana

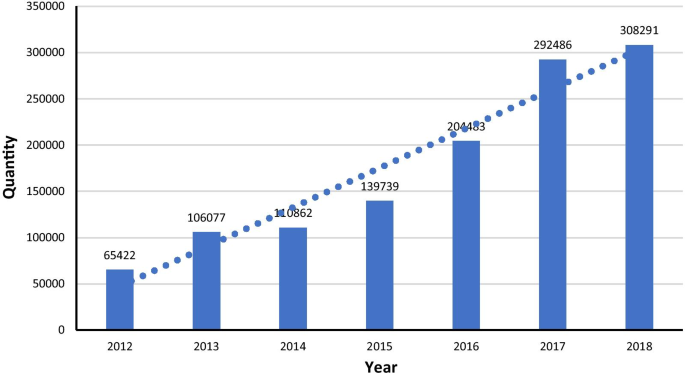

Despite Ghana having halved the maternal mortality ratio in the past 20 years (760 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 1990s versus 310 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 2019), the country still has one of the lowest contraceptive prevalence rates in the region (22.2% in 2014) [ 34 ]. In this country, task sharing programmes for family planning started in 2008 when 33 Community Health Nurses (CHNs) from 6 regions received training in Jadelle insertion and removal. After the Jadelle programme, nurses and midwives from across Ghana started receiving tailored training on Implant provision nationally in 2013.

From 2013, Implants were inserted and removed by CHNs, nurses, and midwives.

Implant users increased from 11 users per provider in 2013 to 18 users per provider as of 2018 (DHIMS2). Contraception prevalence rate among married women increased from 18.6% in 2008 to 19.8% in 2014 among rural residents and from 15.1% in 2008 to 24.6% in 2014 among urban women. The trend in Implants (Jadelle and Implanon) utilisation is depicted in Fig. 1 below. As can be seen, the number of Implant users tripled from the onset of countrywide task sharing programme (2013) to 2018.

(Source: Ghana Maternal Health Survey 2017. 2018)

Trend in implant utilisation in Ghana

Like for other countries, levers of success included the political will and commitment of Ghanaian Leaders, concerted advocacy programmes, stakeholder involvement, quality monitoring and supervision, and support by regional resource teams.

A couple of notable challenges concerned funding gaps and the uneven distribution of CHNs in task sharing.

Ghana’s main next step in task sharing for family planning is to initiate a Midwifery Assistant programme. This programme will enable the training of CHNs as “Midwifery Assistants” who will be sent across the country. Following the training, Ghana projects to further select and train 72 Midwifery Assistants on IUCD in a one-year pilot programme followed by an evaluation and countrywide rollout. Furthermore, as part of its commitment to the FP2020 targets to increase the number of women and girls using modern contraception from 1.5 million to 1.9 million by improved access to and availability of quality family planning services, Ghana aims to support capacity building of Community Health Nurses through task sharing of LARC provision to strengthen the provision of FP services nationally [ 35 ].

Box 6. Nigeria

Nigeria has an estimated population of 200 million with 45 million women of reproductive age [ 36 ]. The total fertility rate is 5.3 with current contraceptive prevalence rate of 12%. While unmet need for contraception was 19% in 2018, the country aims to attain 27% of contraceptive coverage by 2020 [ 36 ]. The Federal Government of Nigeria passed the task sharing policy in 2014 through which Community Health Extension Workers (CHEWs) received training on LARC and a subsequent authorisation to provide and remove Implants and IUCD.

From 2014, nurses, midwives, and CHEWs became responsible for the provision of the entire family planning arsenal except tubal ligation and vasectomy (Box 1 ). They provided family planning counselling and education, promoted dual protection for HIV positive women, inserted and removed Implants and IUCD, and provided injectable contraception.

Implementation of the task sharing policy for family planning increased the uptake of LARC. Figure 2 illustrates the uptake in implants increased by 80% within a period of four years (2015 to 2019).

(Source: Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2018)

Trend in implants uptake in Nigeria

In Nigeria, there was collaboration with professional bodies which enhanced acceptance and ownership of task sharing programmes. Another lever was the ability of majority of CHEWs to fast-learn and absorb training materials.

Adverse circumstances were limited to a small number of poor-performing family planning providers. Also, the programme required intense follow-ups and mentoring which meant that it became costly despite benefits outweighing the costs.