Educational Inequality*

This chapter provides new evidence on educational inequality and reviews the literature on the causes and consequences of unequal education. We document large achievement gaps between children from different socio-economic backgrounds, show how patterns of educational inequality vary across countries, time, and generations, and establish a link between educational inequality and social mobility. We interpret this evidence from the perspective of economic models of skill acquisition and investment in human capital. The models account for different channels underlying unequal education and highlight how endogenous responses in parents' and children's educational investments generate a close link between economic inequality and educational inequality. Given concerns over the extended school closures during the Covid-19 pandemic, we also summarize early evidence on the impact of the pandemic on children's education and on possible long-run repercussions for educational inequality.

This chapter has been prepared for the Handbook of the Economics of Education Volume 6. The asterisk has been added to the title of this paper to distinguish it from NBER working paper 8206 which has the same title. We thank Kwok Yan Chiu, Ricard Grebol, and Ashton Welch for excellent research assistance and the editors, John Jerrim, Sandra McNally, Anders Björklund, Jonas Radl, Martin Hällsten, and Christopher Rauh for helpful comments. Financial support from the National Science Foundation (grant SES-1949228), the Comunidad de Madrid and the MICIU (CAM-EPUC3M11, H2019/HUM-589, ECO2017-87908-R) is gratefully acknowledged. This paper uses data from the National Educational Panel Study (NEPS): Starting Cohort 4–9th Grade, doi:10.5157/NEPS:SC4:1.0.0, Next Steps: Sweeps 1-8, 2004-2016. 16th Edition. UK Data Service SN: 5545 http://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-5545-8, Longitinal Studies of Australian Youth (LSAY): 15 Year-Olds in 2003, doi:10.4225/87/5IOBPG, Education Longitudinal Study (ELS), 2002: Base Year. https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR04275.v1. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research.

MARC RIS BibTeΧ

Download Citation Data

More from NBER

In addition to working papers , the NBER disseminates affiliates’ latest findings through a range of free periodicals — the NBER Reporter , the NBER Digest , the Bulletin on Retirement and Disability , the Bulletin on Health , and the Bulletin on Entrepreneurship — as well as online conference reports , video lectures , and interviews .

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Does COVID-19 persistently affect educational inequality after school reopening? evidence from Internet search data in China

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation School of Economics and Management, University of Science and Technology Beijing, Beijing, China

- Xuejing Hao

- Published: October 30, 2023

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0293168

- Reader Comments

The literature has extensively documented how Covid-19 affects educational inequality, but it remains unclear whether such an effect persists after school reopening. This paper attempts to explore this issue by investigating the search gap for learning resources in China. I categorized learning resources into four types: “school-centered resources”, “parent-centered resources”, “online tutoring agencies resources” and “in-person tutoring agencies resources”. Using Internet search data, I found that nationwide search intensity for learning resources surged when schools were closed, and such search behaviors remained after schools reopened. I also found that high socioeconomic status households had better access to school- and parent-centered resources, and online tutoring resources, even after schools reopened. Given its persistent impact on learning, the pandemic will likely widen educational inequality over extended periods.

Citation: Hao X (2023) Does COVID-19 persistently affect educational inequality after school reopening? evidence from Internet search data in China. PLoS ONE 18(10): e0293168. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0293168

Editor: Changjian Wang, Guangzhou Institute of Geography, Guangdong Academy of Sciences, CHINA

Received: March 31, 2023; Accepted: October 6, 2023; Published: October 30, 2023

Copyright: © 2023 Xuejing Hao. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the manuscript. The socio-economic data of cities were publicly obtained from the National Bureau of Statistics of China. Data were retrieved from the China City Statistical Yearbook ( https://data.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=E0105 ) and the China 2010 census ( http://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/pcsj/rkpc/6rp/indexch.htm ). Anyone would be able to access or request these data in the same manner as the authors. The authors did not have any special access or request privileges that others would not have.

Funding: The author received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

1 Introduction

The global outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic has led to school lockdowns, affecting nearly 1.6 billion school children worldwide at its peak [ 1 ]. School interruption may decrease students’ academic performance, especially for students from low socioeconomic status (Low-SES) households [ 2 – 5 ]. Unequal access to learning resources may be one of the main channels to widen such educational inequality [ 6 , 7 ]. As schools have gradually returned to normal, educators and policymakers are racing to get students back on track. For example, the U.S. government has allocated $122 billion in relief funds to support academic recovery [ 8 ]. To help such remedial interventions better target students in need in the post-Covid period, it is crucial to understand the persistent effects of Covid-19 on students’ unequal access to learning resources after school reopening.

China’s unique features offer a well-suited setting to explore this issue due to its unique following features. First, China took strict measures to control the spread of the pandemic in 2020 and 2021, and students largely resumed in-person schooling after late May 2020. This provides a larger time window to explore the persistent impact of the pandemic on learning. By contrast, schools returned to normal only in 2022 in many other countries. Second, China has the largest education system in the world, with a compulsory education system covering 158 million students in 2022. However, there are large regional education inequalities in China, and students in underdeveloped regions have limited access to learning resources [ 9 , 10 ]. This provides a unique setting for understanding the pandemic-induced educational inequality.

This paper used weekly Baidu Index (similar to Google Trends) data of China’s 361 prefecture-level cities to explore this issue. I used the difference-in-differences approach and event-study analysis to study the inequality in access to different learning resources during school closures, as well as whether the possible inequality persists after school reopening. I found that students living in high socioeconomic status areas (High-SES households) had an advantage over those living in low SES areas (Low-SES households) in access to school- and parent-centered resources, as well as online tutoring resources, even after schools reopened. By contrast, the inequality in access to in-person tutoring agencies resources decreased during school closures, but increased after schools reopened.

My main contributions are as follows. First, this study is among the first to examine whether Covid-19 has a lasting impact on educational inequality after school reopening [ 8 , 11 , 12 ]. While the literature [ 7 , 13 – 16 ] has extensively studied the impact of the pandemic on educational inequality, little has been known about whether such an effect persists after school reopening. China is a well-suited setting to explore the persistent impact of the pandemic on educational inequality because China resumed in-person schooling only several months after the outbreak in 2020. By contrast, many other countries closed schools for more than three semesters. While my estimates may be a lower bound due to the short period of school closures in China, my findings can help understand possible long-term educational consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic in other settings.

The closest to my study is Bacher-Hicks et al. [ 7 ]. This paper differs in the following two ways. First, this paper focused on the school reopening period to explore the persistent effect of COVID-19, while Bacher-Hicks et al. focused on the short-term effect during the school lockdown period and found increased inequality in access to online learning resources. Second, this paper provided a broader pattern of how the pandemic affects educational inequality by exploring inequality in access to other resources such as tutoring resources, while Bacher-Hicks et al. only divided learning resources into “school- and parent-centered resources”. It is important to understand the role of tutoring in alleviating or exacerbating educational inequality, especially for countries with prevailing tutoring cultures like China [ 17 – 21 ].

Second, this paper contributes to the literature on the impact of external shocks on child education. The literature has documented how pandemic-related or natural disaster-related school closures affect students’ learning. For example, the 1918 flu pandemic, the 2003 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) epidemic, or earthquakes [ 22 – 26 ]. But we have not witnessed educational disruption on such a large scale, affecting 1.6 billion students in more than 190 countries for at least several months. This study contributes to the literature by studying the possible lasting consequences of such an external shock (the Covid-19 pandemic) on educational inequality.

The remainder of this paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 provides a literature review on pandemic-induced educational inequality. Section 3 provides information on the development of Covid-19 in China, how students access learning resources during the pandemic, and the tutoring culture in China. Section 4 describes data, which come from the Baidu Index (similar to Google Trend), and empirical strategy. Section 5 presents results on unequal access to learning resources. Section 6 discusses. Section 7 concludes.

2 Literature review

Students from Low-SES households experienced more learning loss than others due to Covid-19. A wide range of studies examined the association between school closure and increased education inequality [ 13 – 16 , 27 – 29 ]. For example, Engzell, Frey and Verhagen were among the first to examine the impact of Covid-19 school closures on academic achievement [ 13 ]. Using a natural experiment in the Netherlands, they found that an eight-week school closure could translate into the loss of as much as one-fifth of the school year. This loss was most pronounced among students from disadvantaged homes. Agostinelli and his colleagues [ 14 ] examined the effects of pandemic school closures on children’s education in the USA and found that high school students from low-income communities suffered 0.4 standard deviation learning losses after a one-year school closure. By contrast, children from high-income communities initially remained unscathed.

Only a few studies, however, had examined whether this equality persisted after school reopening [ 8 , 11 , 12 ]. Singh, Romero and Muralidharanuse explored the learning loss after school closures and the pace of recovery after schools reopened using primary children data in rural Tamil Nadu [ 11 ]. They found that students tested in December 2021 (18 months after school closure) showed significant learning deficits in math and language compared to their peers in the same villages in 2019. Two-thirds of this deficit was made up within 6 months after school reopening. Using a triple-differences strategy, Lichand and Alberto Doria estimated the causal medium-run impacts of keeping schools closed for longer during the pandemic in Brazil [ 12 ]. They contrasted changes in educational outcomes across municipalities and grades that resumed in-person classes earlier in Q4/2020 or only in 2021 and found that relative learning losses from longer exposure to remote learning did not fade out over time. In addition, studies demonstrated the long-term effects of external shocks on learning. For example, Andrabi, Daniels and Dasfour found that 4 years after an earthquake in Pakistan, household and adult outcomes had recovered but learning losses endured. Their learning losses were equivalent to 1.5 fewer years of schooling [ 30 ].

To sum up, previous studies have almost focused on what happens during school closures and found increased education inequality due to the pandemic. Several recent studies have indicated the possible long-term educational effects of the pandemic. Based on this, this study hypothesizes that school closures will increase education inequality in access to learning resources and this inequality will persist after school reopening.

3 Background

The pandemic outbreak in China led to school lockdowns. Online classes were implemented immediately, resulting in a substantial increase in demand for learning resources. This section first provides background information on school closures and reopening in China. It then describes various resources available during the pandemic, with a particular focus on tutoring agencies resources. Finally, this section provides an overview of the tutoring culture in China, shedding light on its potential impact on increased educational inequality during the pandemic.

3.1. The Covid-19 pandemic in China

The Covid-19 pandemic broke out in Wuhan, the capital city of Hubei province, in December 2019 [ 31 ]. Wuhan was locked down on January 23, 2020. Mobility restrictions were subsequently imposed on 14 other cities in Hubei and throughout China [ 32 ]. By the end of April 2020, China had preliminarily contained the spread of Covid-19 on the mainland. Since then, the Chinese government has adopted a zero-COVID policy to contain the pandemic until December 2022, when China roll back lockdowns and gradually fully reopen [ 33 ].

As Fig 1 shows, the pandemic in China has primarily gone through the following five stages (this study focus on the first three stages of the pandemic):

(1) The first stage is the early response period (December 27, 2019—January 19, 2020). During this period, cases of unexplained pneumonia were identified in Wuhan City, Hubei Province. China reported the pandemic and conducted epidemiological investigations to halt its spread. Although some studies suggest that the pandemic in Wuhan could start as early as early December 2019 [ 34 ], the pandemic timelines I show are intended to provide context for school closures and reopenings in China and should be interpreted with caution.

(2) The second stage is the lockdown period (January 20, 2020—April 28, 2020). The Chinese government adopted a lockdown strategy to contain the virus. Schools were closed during this period. The timing of school closures varies slightly by region, but is primarily concentrated in mid-February 2020.

(3) The third stage is the reopening period under the zero-COVID policy (April 29, 2020—March 2022). The pandemic situation was stable during this period, and the government conducted regular pandemic prevention and controls. Schools in most regions fully reopened by mid-May 2020.

(4) The fourth stage is the partial lockdown period (March 2022—December 2022). The outbreak of Omicron caused a Covid case surge in some regions, where partial lockdowns were implemented [ 35 , 36 ].

(5) The fifth stage is the fully reopening period (since December 2022). On December 7, the Chinese government adjust its prevention and control strategy and roll back lockdowns.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

Notes: This chart shows the four stages of China’s against the pandemic since December 2019. Timelines for the first two stages of the pandemic are from the white paper: Fighting Covid-19 : China in Action . http://www.scio.gov.cn/zfbps/32832/Document/1681801/1681801.htm .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0293168.g001

3.2. Learning resources during the pandemic

All Chinese schools were closed in February 2020 due to the Covid-19 outbreak and K-12 students turned to online learning to start their new spring semester. Governments and schools organized online classes promptly to mitigate possible negative consequences due to school closures. Online classes in most cities began in mid-February 2020 (see Table A1 in S1 File ), the scheduled school start date, and continued until the end of May. After May 2020, almost all K-12 students resumed normal in-person classes. The average daily attendance of students and faculty was comparable to pre-pandemic levels.

Learning resources fall into four types during school lockdowns:

(1) “School-centered resources.” They represent education platforms that are necessary for students to take online courses during the pandemic [ 37 ]. These resources use video, communication, cloud storage, and other technologies to enable teachers to conduct online real-time teaching, upload resources, assign homework and interact with students, such as “Tencent Classroom” or “DingTalk”. DingTalk is an intelligent working platform created by Alibaba Group. Although originally designed for business purposes, it has been widely used by primary and secondary schools during school lockdowns in China.

(2) “Parent-centered resources.” They represent generic search terms indicating parents or students are seeking supplemental learning resources (such as “online learning” or “online education”). Parents or students are eager to make up for the school closures losses by searching online learning-related terms.

(3) “Online tutoring agencies resources.” They represent tutoring resources provided by agencies that focus on online learning, such as “Xueersi Online School” or “Yuanfudao”, which are Chinese top online tutoring agencies that provide a wide range of online tutoring services for K-12 students, covering subjects such as mathematics, English, and Science. In particular, many online tutoring organizations provided free online courses across the country during school lockdowns.

(4) “In-person tutoring agencies resources.” They represent tutoring resources provided by agencies that focus on offline learning, such as “Xueda Education” or “Jingrui Education”, which are Chinese top in-person tutoring agencies that offer in-person tutoring services for K-12 students. The government suspended offline business to slow the spread of the pandemic. Though some of them switched to online teaching temporarily, their businesses have been hit hard by the pandemic.

3.3. Tutoring culture in China

Tutoring culture prevails in East Asian societies like China, which are highly competitive and deeply rooted in the Confucian culture that promotes socioeconomic success through education attainment [ 17 – 21 ]. Many parents perceive supplementary tutoring as an effective way to improve students’ academic performance. For example, Zhang shows that private tutoring has a positive effect on urban students with lower achievement based on a survey of 6,043 12th graders in China [ 38 ].

The 2022 Global Education Monitoring Report released by UNESCO shows that more than 75% of Chinese primary and secondary school students participate in after-school tutoring [ 39 ]. The market size of Chinese K-12 tutoring is estimated to exceed 80 billion RMB (about 11.6 billion U.S. dollars) in 2017, involving more than 137 million students and 7 million teachers ( http://www.cse.edu.cn/ ). However, there is a large inequality in access to tutoring resources in China, with students from high socioeconomic status (SES) households having an advantage over those from Low-SES households [ 40 ].

To shed light on how tutoring resources are used across households, I used survey data from the Present Situation of Extracurricular Training for K12 Students to show the tutoring use in China. This survey was conducted in 2017, with a large sample including 41,232 rural and 14,217 urban students [ 41 ]. As shown by Fig A1 in S1 File , I found that urban students were 17.64% more likely to participate in extracurricular tutoring than their rural counterparts. While the survey provided no direct information on in-person and online tutoring, I found that rural students were slightly more likely than urban students to prefer in-person tutoring. For example, 42% of students in rural areas preferred in-person tutoring, 4% higher than students in urban areas.

4 Methodology

Data used in this study are free and publicly available online and do not involve human subjects; it is therefore not subject to institutional review board review requirements.

The main data were scraped from Baidu Index ( https://index.baidu.com ) using the Python. All search data were scraped based on a weekly basis and city level for the study period. Baidu Index is a data sharing platform based on Baidu’s (the largest Chinese search engine, similar to Google) massive netizen behavior data. I used the Baidu Index to query the weekly search intensity of keywords in 361 Chinese prefecture-level cities from January 2011 to January 2021. According to the official explanation, the Baidu Index value is not the actual search volume of a keyword, but a weighted sum of the number of searches. The weighting for calculating the Baidu index is a trade secret, so I don’t know what it is. However, the search index is likely to be linearly correlated with the number of searches for a keyword, as suggested by Qin and Zhu [ 42 ]. Therefore, the Baidu Index value may represent people’s online behavior without significantly distorting.

I used weekly search data of 40 keywords from January 2011 to January 2021. Table A2 in S1 File shows the list of these keywords (I first obtained 67 potential keywords and then selected the most popular 10 keywords respectively based on their rankings in nationwide search intensity [ 7 ], please see Tables A3-A6 in S1 File for detail). I divided them into four categories: (1) “school-centered resources”, which contains ten keywords indicating the top ten online education platforms (such as “Tencent Classroom” or “DingTalk”). (2) “Parent-centered resources”, which contains ten keywords indicating the top ten online learning-related general search terms (such as “online learning” or “online classes”). (3) “Online tutoring agencies resources”, which contains ten keywords indicating the top ten online tutoring agencies (such as “Yuanfudao” or “Xueersi Online School”). (4) “In-person tutoring agencies resources”, which contains ten keywords indicating the top ten in-person tutoring agencies (such as “Jingrui Education” or “Xueda Education”).

I used GDP per capita to measure city-level socioeconomic status (SES). City-level GDP and fixed broadband Internet access data come from the 2019 China Urban Statistics Yearbook ( https://data.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=E0105 ), while the population data come from the Chinese 2010 census data ( http://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/pcsj/rkpc/6rp/indexch.htm ). Cities with GDP per capita above the median were classified as high SES regions. Table 1 compares the search intensity of all learning resources between high and low SES areas of the country.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0293168.t001

As the first row of Table 1 shows, after school closures due to the pandemic outbreak, the overall search intensity for learning resources increased dramatically. When schools reopened, the overall search intensity for learning resources decreased but still more than tripled compared to the pre-Covid level.

As rows (2)-(4) indicate, search intensity for “school-centered resources”, “parent-centered resources”, and “online tutoring agencies resources” increased significantly during the school closures period. When schools reopened, search intensity for these learning resources decreased but remained much higher than the pre-Covid level. By contrast, as shown in the final row, search intensity for “in-person tutoring agencies resources” decreased during school closures. When schools reopened, search intensity increased slightly but remained lower than the pre-Covid level.

4.2 Empirical model

I first used an event study specification to estimate the inequality in access to learning resources due to the Covid-19 pandemic. An event study is a statistical method used to examine the impact of a particular event on an outcome of interest over a defined event window. This method estimates the event effect by comparing the outcome when the event is in place to the outcome when it’s not [ 44 ]. It has been widely used in business and economics research [ 45 ]. In this study, an event study approach enables me to observe the dynamic effects of school closures and reopening on unequal access to learning resources over a given time period.

Weekly indicators covers 72 weeks except January 20, 2020, including pre-Covid 2019 fall semester and post-Covid 2020 spring and fall semesters. My main coefficient of interest is η T , the difference in weekly search intensity between High- and Low-SES households during school closures and reopening periods. PriorYears t represents the prior eight years of data, which is used to identify the week of year effects. μ w(t) (i.e., 1–52) are week fixed effects to control for potential seasonal trends, λ y(t) (i.e., 2011–2021) are year fixed effects to remove variation from year trends. I used clustered standard errors at the city level.

In this section, I will present the results about the changes in the nationwide search intensity for learning resources and about the inequality in access to learning resources between households living in high and low SES areas.

5.1 Nationwide search intensity

In Fig 2 I show the results with nationwide search intensity for learning resources. Panel A shows that the pandemic caused a significant increase in overall search intensity for learning resources. When schools reopened, overall search intensity for learning resources decreased but still doubled compared to the pre-Covid level, suggesting that the pandemic may have a lasting impact on children’s education development.

Notes: The figure above shows raw weekly nationwide search intensity relative to intensity on January 20, 2020. The week of January 20, 2020 is the beginning of Wuhan lockdown, and the week of May 18, 2020 is the beginning of school reopening. Panel A shows search intensity for “overall learning resources”. Panel B for “school-centered resources”, panel C for “parent-centered resources”, panel D for “online tutoring agencies resources”, panel E for “in-person tutoring agencies resources”.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0293168.g002

As indicated in Panels B–D, search intensity for “school-centered resources”, “parent-centered resources”, and “online tutoring agencies resources” peaked in February 2020, more than tripling during school closures compared to the pre-Covid level. This indicates that school lockdowns induced people to use online learning resources to mitigate learning losses. When schools reopened in May, search intensity for these learning resources showed a downward trend but remained higher than the pre-Covid level. By contrast, as shown in Panel E, search intensity for “in-person tutoring agencies resources” decreased during school closures. When schools reopened, search intensity increased slightly but remained lower than the pre-Covid level.

5.2 Inequality in access to learning resources

In this subsection, I show the results for how Covid-19 affects the inequality in access to learning resources for households living in high and low SES areas.

5.2.1 Event-study analysis results.

This study shows the difference in access to learning resources between households living in high and low SES areas in Fig 3 . Panel A shows that, in their access to the overall learning resources, High-SES households had an advantage over Low-SES households during school closures. The gap peaked in February 2020, narrowed afterwards but remained significant after schools reopened. This indicates that the pandemic may have long-term effects on educational inequality.

Notes: This figure shows event study coefficients and corresponding confidence intervals estimating the difference in the weekly value of search intensity between high and low SES areas. The regressions include fixed effects for week of year (1–52) and school year (2011–2021), excluding the week of the Spring Festival. T = 17 represents the week when school reopening began. Panel A shows the search intensity for “overall learning resources”, panel B for “school-centered resources”, panel C for “parent-centered resources”, panel D for “online tutoring agencies resources”, panel E for “in-person tutoring agencies resources”.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0293168.g003

As indicated in Panels B–D, High-SES households had an advantage over Low-SES households in access to school- and parent-centered resources, as well as online tutoring resources during school closures. After schools reopened, these gaps remained significant. One possible explanation is that the shock due to the pandemic permanently changes students’ (parents’, or teachers’) behaviors and thus they still use these online resources even after school reopening [ 46 ]. The gap for online tutoring resources increased dramatically during summer vacations following school reopening. In China, many parents perceive supplementary tutoring as an effective way to improve students’ academic performance [ 38 ]. This leads to students extensively using tutoring resources during the summer to alleviate the learning loss due to the pandemic, potentially exacerbating the inequality in searching for such resources.

By contrast, Panel E shows that the inequality in access to “in-person tutoring agencies resources” decreased during school closures. This suggests that the suspension of in-person agencies played an important role in alleviating educational inequality during this period. Students from Low-SES households who typically have limited access to such tutoring agencies were temporarily no longer at a disadvantage compared to their peers from High-SES households. But after schools reopened, especially during the summer vacation, this inequality increased.

5.2.2 Difference-in-difference analysis results.

I show the difference-in-difference analysis results in Table 2 , which were similar to my event study analysis results. In access to the overall learning resources, search intensity increased by 5.005 for Low-SES households but 7.793 for High-SES households during the school closure period, resulting in a 2.788 search gap. After schools reopened, the gap narrowed but remained at 2.152, suggesting that the Covid-19 pandemic may have a lasting impact on inequality in access to learning resources.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0293168.t002

In access to school-centered resources, parent-centered resources, and online tutoring resources, search intensity increased more for High-SES households than Low-SES households during the school closures period. After schools reopened, the gap in access to school- and parents-centered resources narrowed but remained significant. The gap in access to “online tutoring agencies resources” remained almost unchanged compared to the school closures period level. These results suggest that special attention should be given to students from Low-SES households even after school reopening.

By contrast, in access to “in-person tutoring agencies resources”, search intensity increased for Low-SES households but decreased for High-SES households, resulting in a decreased gap during school closures (-0.052), but this inequality increased after schools reopened.

5.3. Robustness

A series of robustness checks show the stability of my results. First, because Hubei province, where the first Covid-19 cases were reported, has been hardest hit by the pandemic, students’ learning behaviors may change dramatically compared with other provinces. I re-estimated my results by excluding Hubei province. As seen in Table 3 , results were consistent with my previous DID analysis in Table 2 , suggesting that my estimation results were not mainly driven by Hubei province.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0293168.t003

Second, I excluded China’s four municipalities (Beijing, Shanghai, Chongqing, and Tianjin) in my analysis to account for the possibility that the increased inequality in access to learning resources may be driven by some big cities with a much higher level of economic and social development. Table 4 shows that the results remained almost unchanged, suggesting that the regional search gap was not caused by individual highly developed cities.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0293168.t004

Third, even though nearly two-thirds of regions close schools in mid-February, people may still be concerned that different school closure time may have an impact on my results. So, I re-estimated my results by limiting the sample to the regions where schools closed on February 10. As shown in Table 5 , the results were consistent with my previous DID analysis in Table 2 . This suggests that the staggered school closure time concern may be minor.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0293168.t005

Fourth, the school reopening date may vary across China according to local pandemic situations. While schools in most regions reopened by May 18, 2020, schools in several regions reopened later due to small-scale cases of new infections. I excluded regions where schools reopened after May 18 in my analysis, including Beijing, Jilin, Heilongjiang, Hubei, and Ningxia. Table 6 shows that the results remained almost unchanged.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0293168.t006

Fifth, people may be concerned that GDP per capita is not a good measure of socioeconomic status (SES) when studying the pandemic impact on educational inequality. Here I used instead the fixed broadband Internet access per capita to measure city-level SES. Table 7 shows that the results were similar to my previous DID analysis in Table 2 , where SES was measured by GDP per capita.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0293168.t007

Finally, people may be concerned that my results are sensitive to the choice of keywords to construct the four types of learning resources. To show the robustness of my results, I reconstructed my measures of these learning resources. Specifically, I excluded keywords in the following situations: (1) keywords also searched by companies and employees for telework during the pandemic (“Zoom” and “DingTalk” in “school-centered resources”); (2) keywords also searched by companies and employees for vocational education or corporate training (“Ambow” in “in-person tutoring agencies resources”); (3) keywords with a large absolute advantage in search intensity (“Xueersi Online School” and “Yuanfudao” in “online tutoring agencies resources”, as seen in Table A5 in S1 File ); (4) keywords that only have search data after the pandemic in the Baidu Index (“online course” in “parent-centered resources”). As seen in Table 8 , the results were similar to my previous findings in Table 2 , suggesting that the keyword choice concern may be minor.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0293168.t008

6 Discussion

The literature has well-documented the substantial increase in educational inequality during school closures. However, we know little about whether such an effect persists after school reopening. Several recent studies have indicated that learning loss during school closures did not mechanically disappear as in-person classes resumed [ 12 ]. The unequal access to learning resources may be one of the main channels to persistence in widened gaps between students from High- and Low-SES households.

This study explores the persistence of inequality in students’ access to learning resources caused by Covid-19 in China. The results show that the pandemic increased educational inequality among students. High-SES households had better access to school- and parent-centered resources, as well as online tutoring resources, and these gaps persisted after schools reopened. This indicates that disadvantaged students suffer the most from the pandemic, and this inequality may persist over time.

My study has important policy implications. Because school closures may exacerbate educational inequality and such an effect may persist after school reopening, I recommend that countries prioritize policies to compensate for education losses for vulnerable children. Given that countries have almost returned to normal by the end of 2022, governments should pay special attention to disadvantaged students to help them progress better in the post-Covid period.

For instance, given the finding of disparities in access to school-centered resources, the government should invest more in school facilities to equalize learning opportunities. This involvement can take the form of providing resources, infrastructure, and technical support. The findings on tutoring resources highlight the impact of online tutoring agencies resources on increasing educational inequality. This provides insights for developing remedial policies especially in countries that value a tutoring culture. Offering free but high-quality tutoring resources to students living in low-SES areas may effectively enhance their accessibility to such resources. These initiatives have the potential to mitigate educational inequality and contribute to the long-term academic development of students living in Low-SES areas.

It should be noted that this paper used a single source of Baidu index real-time data. While search data has been widely used to predict citizen behavior and decision-making, such as emigration interest [ 42 ], environmental protection [ 47 ] and changes in well-being [ 48 , 49 ], future research endeavors could combine real-time data with survey data to enhance the robustness of our findings.

7 Conclusions

This study explores whether Covid-19 has a lasting impact on educational inequality after school reopening using Baidu Index data from China. I divided learning resources into four categories, covering “school-centered resources”, “parent-centered resources”, “online tutoring agencies resources” and “in-person tutoring agencies resources”. I found that nationwide search intensity for learning resources had more than tripled during school closures compared to the pre-Covid period. When schools reopened, search intensity for learning resources showed a downward trend but remained higher than the pre-Covid level. I also found that the pandemic increased educational inequality among students. High-SES households had better access to school- and parent-centered resources, and online tutoring resources, even after schools reopened. These findings suggest that the Covid-19 pandemic may have a long-term impact on educational inequality.

Supporting information

S1 file. appendix..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0293168.s001

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- PubMed/NCBI

- 8. Halloran C, Hug CE, Jack R, Oster E. Post COVID-19 Test Score Recovery: Initial Evidence from State Testing Data. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2023 April 10.

- 11. Singh A, Romero M, Muralidharan K. COVID-19 Learning loss and recovery: Panel data evidence from India. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2022 Oct 17.

- 25. Liang W, Xue S. Pandemics and Intergenerational Mobility of Education: Evidence from the 2003 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) Epidemic in China. GLO Discussion Paper Series. 2021.

- 27. Bayrakdar S, Guveli A. Inequalities in home learning and schools’ provision of distance teaching during school closure of COVID-19 lockdown in the UK. ISER Working Paper Series; 2020.

- 28. Dorn E, Hancock B, Sarakatsannis J, Viruleg E. COVID-19 and student learning in the United States: The hurt could last a lifetime. McKinsey & Company. 2020; 1:1–9.

- 33. Chen J, Chen W, Liu E, Luo J, Song ZM. The economic cost of locking down like china: Evidence from city-to-city truck flows. OpenScholar@ Princeton. 2022:1–43.

- 41. Lu J. Investigation on the Present Situation of Extracurricular Training for K12 Students in China. Peking University Open Research Data Platform. 2018.

- 44. Huntington-Klein N. The effect: An introduction to research design and causality. CRC Press. 2021.

- 46. Barrero JM, Bloom N, Davis SJ. Why working from home will stick. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2021 May 3.

- 47. Barwick PJ, Li S, Lin L, Zou E. From fog to smog: The value of pollution information. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2019 Dec 9.

Assessing educational inequality in high participation systems: the role of educational expansion and skills diffusion in comparative perspective

- Open access

- Published: 14 May 2024

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Satoshi Araki ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0302-959X 1

26 Accesses

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

A vast literature shows parental education significantly affects children’s chance of attaining higher education even in high participation systems (HPS). Comparative studies further argue that the strength of this intergenerational transmission of education varies across countries. However, the mechanisms behind this cross-national heterogeneity remain elusive. Extending recent arguments on the “EE-SD model” and using the OECD data for over 32,000 individuals in 26 countries, this study examines how the degree of educational inequality varies depending on the levels of educational expansion and skills diffusion. Country-specific analyses initially confirm the substantial link between parental and children’s educational attainment in all HPS. Nevertheless, multilevel regressions reveal that this unequal structure becomes weak in highly skilled societies net of quantity of higher education opportunities. Although further examination is necessary to establish causality, these results suggest that the accumulation of high skills in a society plays a role in mitigating intergenerational transmission of education. Potential mechanisms include (1) skills-based rewards allocation is fostered and (2) the comparative advantage of having educated parents in the human capital formation process diminishes due to the diffusion of high skills among the population across social strata. These findings also indicate that contradictory evidence on the persistence of educational inequality in relation to educational expansion may partially reflect the extent to which each study incorporates the skills dimension. Examining the roles of societal-level skills diffusion alongside higher education proliferation is essential to better understand social inequality and stratification mechanisms in HPS.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Relation Between Family Socioeconomic Status and Academic Achievement in China: A Meta-analysis

Education and Parenting in the Philippines

The Public Purposes of Private Education: a Civic Outcomes Meta-Analysis

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Access to higher education has markedly increased over the past decades, leading to the establishment of high participation systems (HPS) worldwide (Cantwell et al., 2018 ). Despite such an expansion of higher education opportunities, evidence shows that one’s educational attainment is unequally distributed based on socio-economic status (SES) (Marginson, 2016a , 2016b ; Pfeffer, 2008 ; Voss et al., 2022 ). This persistent association between SES and education is often explained through the lens of stratification theories, such as maximally maintained inequality (Raftery & Hout, 1993 ) and effectively maintained inequality (Lucas, 2001 ). Comparative studies also highlight the influence of societal conditions, suggesting that highly tracked education systems are likely to exacerbate educational inequalities despite facilitating smoother transitions from education to work (Bol et al., 2019 ; Burger, 2016 ; Österman, 2018 ; Reichelt et al., 2019 ; Traini, 2022 ).

Although researchers have extensively investigated the unequal structure of educational attainment from longitudinal and cross-national perspectives, the mechanisms behind the heterogeneous degrees of inequality across societies remain elusive. As mentioned, educational tracking has been seen as a key societal determinant. However, OECD ( 2018 ) reveals that the magnitude of SES significantly varies even among HPS with similar levels of tracking and higher education expansion. This suggests there are missing societal traits, not yet explored in prior studies, that explain cross-national variation in the extent of educational inequality. Identifying this “hidden” structure would also be valuable from a policy perspective in addressing unequal educational attainment in HPS.

In this regard, recent research has detected a unique social structure: (1) the expansion of higher education (i.e., educational expansion) is not identical to the accumulation of high skills (i.e., skills diffusion) and (2) these two societal dimensions play distinct roles in social stratification by influencing the amount and allocation of human capital and socio-economic rewards (Araki, 2020 ; Araki & Kariya, 2022 ; Hanushek & Woessmann, 2015 ). 1 Drawing on these findings, Araki ( 2023b ) proposed the “EE-SD model” to uncover the characteristics of higher education systems and relevant social problems. This framework, with close attention to skills alongside education per se, potentially offers a useful viewpoint to better understand educational stratification in HPS for two reasons.

First, given that high-SES families tend to transmit their high educational attainment via human capital development of offsprings in terms of high skills and aspirations (Davies et al., 2014 ), this relative advantage may weaken due to skills diffusion insofar as this societal shift occurs in a way that promotes the share of the population possessing high skills across social strata including the disadvantaged. This also means, so long as skills diffusion is realized exclusively among the advantaged without involving their low-SES counterparts, the degree of educational inequality may even intensify due to the exacerbated advantage of the high-SES group in human capital formation.

Second, in case skills diffusion promotes a more meritocratic rewards allocation process based on increased visibility of skills (Araki, 2020 ), it is plausible that the relative impact of family background on educational attainment diminishes while the importance of skills as such increases. Put differently, if HPS are formed merely as a consequence of expanding educational opportunities without skills diffusion, the advantaged may retain their prestigious positions on the education ladder regardless of their skills level. Furthermore, considering a possibility that the accumulation of high skills in a society does not make skills more visible, skills diffusion may not affect the structure of educational inequality due to the absence of skills-based meritocratic system. In either case, the association between intergenerational transmission of higher education and societal-level skills diffusion represents an essential knowledge gap in this vein.

From a comparative perspective, this paper thus examines how the linkage between SES and college completion varies across societies depending on the degree of skills diffusion, as well as higher education expansion and tracking. In what follows, the relevant literature is reviewed, followed by data/methods, analysis results, and discussion.

Inequality in educational attainment

In analyzing the association between individuals’ SES and educational attainment, scholars have long paid attention to how it shifts in tandem with educational expansion (Breen, 2010 ; Shavit et al., 1993 ). This agenda is particularly relevant in the contemporary world, many parts of which have achieved HPS with tertiary enrolment ratios exceeding 50% (Cantwell et al., 2018 ; Marginson, 2016a ).

One oft-cited concept in this line of research is maximally maintained inequality (MMI) proposed by Raftery and Hout ( 1993 ), although their primary focus was on secondary rather than tertiary education. Uncovering that the contribution of social origin to children’s education persisted despite increased educational opportunities in Ireland, they argued intergenerational inequality would only begin to decline once the advantaged reached a saturation point (e.g., 100% of enrolment). Subsequent studies have widely confirmed this MMI structure at the tertiary education level (Bar Haim & Shavit, 2013 ; Chesters & Watson, 2013 ; Czarnecki, 2018 ; Konstantinovskiy, 2017 ; Wakeling & Laurison, 2017 ).

Extending MMI, Lucas ( 2001 ) found that inequality had been effectively maintained, as advantaged individuals would secure valuable educational assets (e.g., prestigious institutions and fields of study) even when the disadvantaged caught up in terms of the level of educational qualifications. A vast literature has empirically supported the idea of effectively maintained inequality (EMI) in the higher education sector across the globe (Ayalon & Yogev, 2005 ; Boliver, 2011 ; Dias Lopes, 2020 ; Ding et al., 2021 ; Gerber & Cheung, 2008 ; Hällsten & Thaning, 2018 ; Kopycka, 2021 ; Reimer & Pollak, 2010 ; Seehuus, 2019 ; Torche, 2011 ; Triventi, 2013 ).

Meanwhile, introducing a standardized analytical model, Breen et al. ( 2009 ) argued that the link between origins and educational attainment weakened along with educational expansion in multiple countries. Much research reports a similar structure of nonpersistent inequality (Barone & Ruggera, 2018 ; Breen, 2010 ; Breen et al., 2010 ; Duru-Bellat & Kieffer, 2000 ; Pfeffer & Hertel, 2015 ). In line with these longitudinal findings, comparative work also detected the smaller social gap in education in societies with a larger share of highly educated populations, despite the observed MMI structure in each country (Liu et al., 2016 ).

In investigating the mechanisms behind cross-national variation in the SES effect on educational attainment, scholars have shed light on institutional stratification in education (Pfeffer, 2008 ). Evidence shows that (1) highly tracked systems make education-work transitions more effective (i.e., learners gain occupation-specific skills or at least educational credentials signifying those skills, thus obtaining occupations relevant to their fields of study) (Bol et al., 2019 ) but (2) strong tracking also intensifies educational inequality compared to more comprehensive education systems (Bol and van de Werfhorst, 2013 ; Burger, 2016 ; Chmielewski et al., 2013 ; Österman, 2018 ; Reichelt et al., 2019 ; Tieben & Wolbers, 2010 ; Van de Werfhorst, 2018 ; Van de Werfhorst and Mijs, 2010 ).

The link between SES and educational attainment has thus been uncovered in relation to societal-level educational expansion and tracking. Nonetheless, one puzzling fact is that the degree of inequality significantly varies even among HPS with similar social policies and education systems (OECD, 2018 ). It is plausible that some societal traits, which have been inadequately incorporated in prior studies, operate in forming educational inequality.

As argued, one potentially important process here is skills diffusion. Evidence shows (1) the degree of skills diffusion is positively correlated with that of educational expansion, making HPS more likely to advance skills diffusion (Araki, 2023b ) but (2) the effects of educational expansion and skills diffusion on socio-economic outcomes at the individual and societal levels are not identical (Araki, 2020 ; Hanushek & Woessmann, 2015 ). Given these arguments, one may assume that the accumulation of high skills in a society, apart from educational proliferation, plays a unique role in forming educational (in)equality especially via two possible mechanisms.

First, prior research argues that skills diffusion may accelerate the skills-based rewards distribution because of increased discernability of high skills, which allows the labor market to identify highly skilled human resources (Araki, 2020 ). Should this intensified meritocratic mechanism induced by skills diffusion be applicable to the schooling process, the impact of SES on educational attainment may diminish in contrast to the growing importance of high skills. Nonetheless, evidence is elusive concerning the extent to which skills diffusion actually increases skills’ visibility in such a way that educational assets are allocated based on skills instead of SES. Put differently, it is still possible that the structure of educational inequality is not affected, or rather exacerbated, by skills diffusion.

Second, the accumulation of high skills, especially among the disadvantaged, may mitigate the comparative advantage of high-SES groups in human capital formation. Considering that the advantaged are more likely to invest their resources to foster children’s skills, which are favored in the process of climbing the educational ladder, the effects of such interventions could be hindered by skills development among the disadvantaged group. One should note, despite this potential consequence of skills diffusion, SES may still exert its influence on education by exerting symbolic power in that children from advantaged families easily internalize legitimate culture and behaviors leading to better educational outcomes (Jæger & Karlson, 2018 ; Sieben & Lechner, 2019 ). In addition, in response to the catchup by low-SES groups, their high-SES counterparts may invest more to further enhance children’s skills both quantitatively and qualitatively (i.e., the level and type of skills, respectively). This perception is aligned with EMI theory on educational inequality.

Nevertheless, the SES gap incurred by unequal human capital formation could still diminish in association with skills diffusion. For example, Huber, Gunderson, and Stephens ( 2020 ) found that the skills development mechanism played a role in reducing inequalities, although their focus was on educational spending and income inequality. Should this be the case for the distribution of higher education opportunities, it is logical to assume that the cross-national variation in the linkage between SES and educational attainment can be explained partially, if not completely, by the extent of skills diffusion in each society. Indeed, while showing the typological EE-SD framework, Araki ( 2023b ) argued that the structure of educational inequality would be an important agenda to be examined by incorporating both educational expansion and skills diffusion. Therefore, the current study investigates the heterogeneous SES effect on higher education attainment with particular attention to societal-level skills diffusion, educational expansion, and tracking.

Data and methods

Data and strategy.

The degree of skills diffusion has long been unmeasurable in a comparable way. However, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has recently developed an international survey of adult skills (PIAAC), which permits a cross-national examination of cognitive skills. Although using this dataset merely covers OECD and partner countries, future research can use the framework and findings that follow as the foundation to investigate broader geographical areas.

PIAAC is composed of a standardized assessment of cognitive ability and background questionnaires including educational attainment and socio-demographic attributes. Participants are nationally representative individuals aged 16 to 65 and accordingly, one can infer the skills level of the population based on individual-level data (OECD, 2019 ). Because of its wide coverage of variables and high quality skills data, PIAAC has been used by the vast literature on educational inequality and socio-economic returns to education (Araki, 2020 , 2023a ; Hanushek et al., 2015 ; Heisig et al., 2020 ; Huber et al., 2020 ; Jerrim & Macmillan, 2015 ; Pensiero & Barone, 2024 ). One limitation of PIAAC is its scope: while it primarily assesses cognitive ability in terms of literacy and numeracy, 2 other types (e.g., noncognitive and occupation-specific skills) are not directly included. However, given that cognitive skills serve as the basis for other dimensions of skills and socio-economic outcomes (Krishnakumar & Nogales, 2020 ; OECD, 2016 ), it is sensible to use the PIAAC data to quantify the skills level.

Among PIAAC participants aged 16 to 65, this article focuses on respondents aged 25 to 34, considering that the association between SES and education could significantly vary across cohorts. This approach also reduces two risks: (1) as compared to younger groups, respondents are likely to have completed the highest level of education; and (2) unlike older groups, the influence of work experience and relevant attributes on educational attainment is assumed to be small. From the OECD public use database, 3 the current study extracts 32,549 respondents in 26 countries that provide valid data for all predictor and outcome variables as detailed below. See Table 1 for specific countries and the sample size with the gross tertiary enrolment ratio, which indicates that all countries are classifiable as HPS (i.e., over 50%).

One potential analytic approach here is to focus on how the contribution of SES to educational attainment has shifted over time in the process of educational expansion and skills diffusion in a given society. As reviewed, much research in this vein has employed a longitudinal approach to compare multiple cohorts within countries. Although this method gives detailed implications for each society, it does not completely address period effects (Glenn, 1976 ). In addition, because the strength of tracking is relatively stable (Brunello & Checchi, 2007 ), it is difficult to accurately detect the longitudinal change.

Two types of cross-country analyses thus become sound strategies. The first approach is to perform country-specific analyses using the individual-level data and to contrast the relative degree of educational inequality and societal-level degrees of educational expansion, skills diffusion, and tracking across cases. The second strategy is to employ hierarchical modeling with pooled data from all countries with both individual and country-level variables. While the first method provides evidence for each society, the second one shows the general tendency beyond the national boundary. Given the comparative advantage of these two options, both approaches are employed: (1) country-specific analyses using individual-level data in 26 countries and (2) multilevel regressions focused on the link between the strength of educational inequality and societal-level conditions.

The outcome variable is the possession of a bachelor’s degree or above, which is equivalent to the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) 2011 Level 6 and above. Although short-cycle tertiary education (ISCED 2011 Level 5) is sometimes included when assessing individuals’ educational attainment, the nature of this educational stage varies across countries (Di Stasio, 2017 ). To ensure international comparability, the current paper employs ISCED 2011 Level 6 and above as a measure for high educational attainment. Considering also (1) the potential bias incurred by using a categorical measure in hierarchical modeling and (2) the different nature between the possession of tertiary degrees and the length of educational experience, a continuous variable (i.e., years of schooling) is also adopted. Because one country does not provide data on this continuous measure, the nonlinear model (with the dummy for ISCED 2011 Level 6 and above) is primarily shown in the manuscript, while the linear model (with years of schooling as an outcome) is displayed as a robustness check (see the next section for more details).

As regards individual-level predictor variables, much research has used parental education, occupation, and economic status, as well as the number of books in the home (NBH). Among these, the PIAAC dataset includes parental education (i.e., father’s and mother’s highest levels of education) and NBH. Although NBH has been widely taken as a representative SES measure (Chmielewski, 2019 ; OECD, 2016 ; Sieben & Lechner, 2019 ), recent research points out its potential endogeneity problem especially when the respondents are children (Engzell, 2021 ). Considering also the meaning/value of NBH substantially varies across countries, the current study uses parental education to represent SES. This strategy focused on parental education is widely employed by the literature in this vein (Brand & Xie, 2010 ; Cheng et al., 2021 ; Oh & Kim, 2020 ; Pensiero & Barone, 2024 ; Torche, 2018 ). Following prior studies, three categories are constructed by combining paternal and maternal education (i.e., both parents, one parent, or neither parents are tertiary educated). Meanwhile, a robustness check is performed by replacing parental education with NBH, and the result is shown in the Appendix (Table 5 ). Note that the result of this supplementary analysis is consistent with the main findings that follow. Alongside parental education, individual-level predictors include gender (men dummy), age (30–34-year-old dummy), 4 and immigrant background (first-generation immigrant dummy) as these attributes are substantially associated with educational attainment (Breen & Jonsson, 2005 ).

Country-level variables cover the levels of educational expansion, skills diffusion, and tracking. To align with the outcome variable, the education measure is the percentage of the population who possess a bachelor’s degree and above. Considering the potential bias caused by using the simple means of individual-level education and skills in the PIAAC dataset for macro-level indicators, the societal-level variables here are not estimated based on PIAAC micro data but extracted from the national statistics in each country (OECD, 2014 ). It is noteworthy that the following results and implications are robust even when replacing this societal trait with the proportion of people with a degree including ISCED 2011 Level 5 (short-cycle tertiary) (see Table 6 in the Appendix).

For the skills indicator, following previous research (Araki, 2020 , 2023c ), the proportion of individuals whose mean score of literacy and numeracy in PIAAC is 326 and above (out of 500 points) is used. This is consistent with the OECD’s definition of high skills (OECD, 2019 ). As discussed, “skills” directly assessed by PIAAC refer to cognitive ability, and therefore, future research must incorporate other dimensions to advance this line of studies. These macro-level education and skills metrics are limited to the population aged 25 to 34 in line with individual-level variables. This way, the marginal distribution of educational opportunities and skills among the target age group is properly incorporated in the following analyses. Note that this measure reflects the skills level among the population ages 25–34, and hence, it is suitable to test one of the said two hypothetical mechanisms: a more meritocratic rewards allocation process is intensified by skills diffusion, leading to less educational inequality. Meanwhile, the percentage of people with high skills among those whose parents are not tertiary educated is also used to examine the second scenario: the larger share of highly skilled people among low-SES groups undermines the comparative advantage of high-SES groups in human capital formation. This skills indicator for the low parental education group is estimated by the OECD using all participants in each country and not limited to those aged 25 to 34. The analysis results of this second approach are thus shown in the Appendix (Table 6 ).

The degree of tracking is derived from Bol and van de Werfhorst ( 2013 ). Admittedly, other conditions could also affect the association between parental education and educational attainment against a background of skills diffusion and educational expansion. In particular, the macroeconomic structure may alter the social function of skills and higher education, while the overall degree of social inequality may influence educational inequality. Although the aforementioned three societal-level traits are primarily used given the potential bias incurred by a larger number of macro-level measures against the relatively small sample size for countries, GDP per capita and the Gini index are therefore added to the main analysis for a robustness check (see the Appendix, Table 6 ). Table 2 summarizes descriptive statistics.

Analytic models

For country-specific analyses, binary logistic regression is performed using individual-level data for 26 countries respectively as follows.

where i = individual, p i = the probability of holding a bachelor’s degree or above for individual i , b n = the coefficient of predictor variables, M i = the men dummy, A i = the age 30–34 dummy, I i = the first-generation immigrant dummy, BT i = the dummy for those whose parents are both tertiary educated, OT i = the dummy for those having one tertiary educated parent, and ε i = the residual for individual i . The primary focus here is on the parameters for parental education ( b 4 and b 5 ). Given that these coefficients do not provide straightforward implications (Breen et al., 2018 ; Mood, 2010 ), the average marginal effects (i.e., predicted probability for each parental education group) are also estimated and compared across countries to confirm the variation in the advantage of having tertiary educated parents (see Fig. 1 ). This serves as the basis for the following multilevel regressions.

In model 1 of hierarchical modeling, only individual-level predictors are employed with particular attention to b 4 , and b 5 in Eq. ( 2 ), where j = level two (i.e., country).

In models 2 to 4, three country-level variables and their interactions with two individual-level parental groups are added to model 1, respectively, to examine how the association between parental education and educational attainment varies in accordance with the societal conditions. Although there is a risk of biased estimation by including more than two level-two variables given the limited number of countries in the current model, model 5 concurrently incorporates the extent of educational expansion, skills diffusion, and tracking to confirm the robustness of models 2 to 4. GDP per capita and the Gini index are further added for robustness checks (see Table 6 in the Appendix). The basic concepts of these models are describable as follows.

where γ 00 = the average intercept, γ 0n = the coefficient of country-level predictor variables X , and u 0 j = the country ( j )-dependent deviation. Substituting Eq. ( 3 ) into Eq. ( 2 ) and denoting b n by γ n 0 while incorporating cross-level interaction terms, γ 4 n and γ 5 n in Eq. ( 4 ) below indicate the heterogeneous magnitudes of two parental education measures associated with three societal traits. Following the recent argument that random slopes on lower-level variables used in cross-level interactions should be incorporated (Heisig & Schaeffer, 2019 ), both random intercepts and slopes are estimated for parental education as follows.

where u nj = the country dependent deviation of the slopes for two parental education groups. Finally, as shown in Eq. ( 5 ) where Y ij is years of schooling for individual i in country j , model 6 employs a multilevel linear regression approach with the same predictors as model 5 for a robustness check.

Note that these cross-sectional models do not completely account for unobserved variables at the individual and societal levels. As the OECD has been administering the second cycle of PIAAC, future research must undertake longitudinal analyses to address this issue.

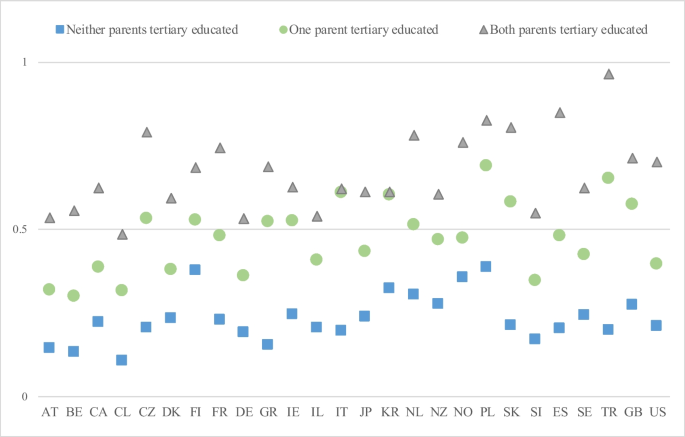

Table 3 shows the results of binary logistic regression of college completion for 26 countries. In all cases, parental education exhibits a positive sign for the chance of attaining tertiary education (i.e., b 4 and b 5 in Eq. 1 are positive and statistically significant). 5 In particular, the magnitude is notably large for the most advantaged group with both parents being tertiary educated (e.g., b 4 = 1.02, 95%CI 0.63 to 1.41; b 5 = 1.92, 95%CI 1.43 to 2.42 in Austria). Figure 1 indeed indicates that the predicted probability of obtaining a first degree substantially varies across three parental education groups, with the most disadvantaged tier (i.e., without tertiary educated parents) suffering from a limited chance of completing tertiary education in every country.

Predicted probability of completing tertiary education by parental education in 26 countries. The Y axis indicates the predicted probability of attaining tertiary education (ISCED 2011 level 6 or above) for three parental education groups as indicated at the top of the figure across 26 countries ( X axis). See also Table 1 for country abbreviations

Nonetheless, it is worth noting that despite the relative disadvantage within a country, the predicted probability of college completion among the low parental education group in some countries (e.g., 37.6%, 95%CI 33.9 to 41.3 in Finland) is higher than that of the second tier with one tertiary educated parent in others (e.g., 29.8%, 95%CI 22.7 to 36.9, in Belgium). In addition, as far as the extent of educational inequality is concerned, the gap in the chance of college completion between the most advantaged and disadvantaged groups differs across nations, ranging from 28.8 points in South Korea to 76.6 points in Turkey. The key question here is how this cross-national variation in intergenerational transmission of higher education is associated with societal-level conditions.

Table 4 summarizes the results of multilevel regressions. In model 1 with only individual-level variables, all predictors show a significant sign for educational attainment at the 0.1% level. That is, even when accounting for gender, age, and immigrant background, as well as cross-national differences in the intercept and slopes, the strong association between parental education and educational attainment is confirmed. As observed earlier in the country-specific analyses, the magnitude of having two tertiary educated parents is larger than that of only one highly educated parent ( γ 40 = 1.91, 95%CI 1.73 to 2.08; γ 50 = 1.08, 95%CI 0.95 to 1.21). This substantial linkage between parental education, especially having two tertiary educated parents, and the chance of college completion holds regardless of models in the following analyses.

Model 2 adds one country-level variable (i.e., the proportion of tertiary educated people) and its cross-level interactions with two measures for parental education. Apart from the significant coefficients of individual-level predictors, the interaction terms between parental education and the degree of educational expansion shows negative and statistically significant signs ( γ 41 = −0.02, 95%CI −0.04 to 0.00, P = 0.022; γ 51 = −0.02, 95%CI −0.04 to −0.01, P = 0.006). This suggests, as argued by some prior studies, the advantage of having tertiary educated parents is likely to be smaller in societies where the aggregate education level is relatively high. Put differently, although further longitudinal investigations are necessary to establish causality, the accumulation of educational opportunities in a society might operate as an equalizer in mitigating the influence of parental education.

An identical structure is observed in model 3, where the degree of educational expansion is replaced with that of skills diffusion (i.e., the proportion of highly skilled people). In addition to the significant links between individual-level predictors and the probability of obtaining a first degree, the coefficient of the interaction terms between parental education and the societal-level skills indicator is negative ( γ 42 = −0.03, 95%CI −0.05 to −0.01, P = 0.003; γ 52 = −0.03, 95%CI −0.05 to −0.02, P < 0.001). As with the extent of educational expansion, this result indicates a possibility that the role of parental education in children’s educational attainment could decline in societies with a higher degree of skills diffusion. In Model 4, the strength of tracking is included instead of societal-level education and skills measures. As reported by previous research in this vein, the positive signs of interaction terms between tracking and parental education are confirmed ( γ 43 = 0.15, 95%CI −0.02 to 0.31, P = 0.088; γ 53 = 0.15, 95%CI 0.04 to 0.27, P = 0.007). That is, the extent of intergenerational educational inequality is likely to be stronger in more tracked systems.

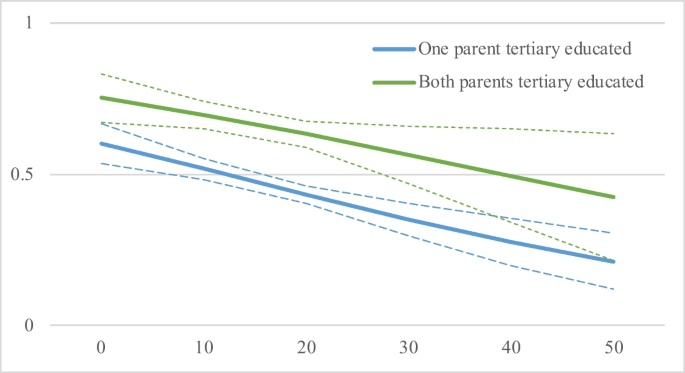

Model 5 incorporates all three country-level predictors and their interaction terms. One important result here is that the interaction between parental education and the degree of educational expansion is almost nullified ( γ 41 = −0.00, 95%CI −0.03 to 0.02, P = 0.773; γ 51 = 0.01, 95%CI −0.01 to 0.02, P = 0.326). In contrast, the one between parental education and the skills diffusion measure holds its negative sign ( γ 42 = −0.03, 95%CI −0.05 to −0.00, P = 0.030; γ 52 = −0.03, 95%CI −0.05 to −0.02, P < 0.001). The same structure is observed when (1) conducting multilevel linear regression with years of schooling as the outcome in Model 6 ( γ 41 = −0.04, P = 0.133; γ 51 = −0.01, P = 0.453; γ 42 = −0.04, P = 0.072; γ 52 = −0.05, P = 0.001), (2) incorporating the proportion of people with short-cycle tertiary education for the educational expansion metric in Model A2 ( γ 42 = −0.02, 95%CI −0.04 to 0.00, P = 0.034; γ 52 = −0.03, 95%CI −0.04 to −0.02, P < 0.001), and (3) adjusting for GDP per capita and the Gini index as additional societal-level conditions in Model A3 ( γ 42 = −0.03, 95%CI −0.06 to 0.00, P = 0.059; γ 52 = −0.03, 95%CI −0.04 to −0.01, P < 0.001). Figure 2 indeed depicts the diminishing effect of parental education in tandem with higher proportions of the population with high skills.

Marginal effects of parental education by the degree of skill diffusion. The Y axis is the marginal effects of parental education (i.e., one parent is tertiary educated; both parents are tertiary educated) across the degree of skills diffusion (i.e., the percentage of population with high skills) ranging from 0 to 50 ( X axis) based on the multilevel binary logistic regression (model 5). The dashed lines indicate the 95% confidence intervals

The sole exception is the final model using the share of highly skilled people among the low parental education group as the societal-level skills measure (Model A4 in the Appendix, Table 6 ). While its interaction with the second tier (i.e., only one tertiary educated parent) shows a substantially negative coefficient ( γ 52 = −0.02, 95%CI −0.04 to −0.01, P = 0.001), the one with the top tier (i.e., both parents are tertiary educated) is not statistically significant despite its negative sign ( γ 42 = −0.02, 95%CI −0.04 to −0.00, P = 0.106). This suggests that the second hypothetical scenario (i.e., the advantage of high-SES groups in human capital formation diminishes along with skills diffusion among the disadvantaged) is partially supported in that the second layer in parental education with one tertiary educated parent encounters their diminishing advantage in educational attainment. However, the most advantaged group seems to retain their relative position even when the disadvantaged advances their cognitive skills. In the next section, after summarizing the key findings, some implications are discussed.

Discussion and conclusion

This study investigates cross-national variation in intergenerational transmission of education among high participation systems (HPS). Drawing on the EE-SD framework (Araki, 2023b ), particular attention is paid to societal-level higher education expansion, tracking, and skills diffusion. Using the OECD PIAAC data for 32,549 adults in 26 countries, individual-level analyses first corroborate the literature in that parental education is significantly associated with the likelihood of college completion. However, multilevel regressions show that educational inequality is not persistent; rather, the advantage of having tertiary educated parents becomes smaller in societies with a higher proportion of tertiary graduates. This result supports prior evidence indicating the equalizing function of educational expansion.

Nevertheless, once incorporating the degrees of skills diffusion and tracking as societal-level predictors, the interaction between the extent of educational expansion and parental education loses its significant sign. Instead, the skills indicator holds a negative interaction effect with parental education. Further research is necessary to claim causation, given that (1) unobserved societal traits may be significantly affecting the link between parental education and the societal-level education/skills indicators and (2) the degree of skills diffusion may mediate the effect of educational expansion as detailed below. Yet, based on these results, it is plausible that the accumulation of high skills in a society plays a role in altering the power of parental education over children’s chance of attaining higher education.