The State of Critical Race Theory in Education

- Posted February 23, 2022

- By Jill Anderson

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

- Moral, Civic, and Ethical Education

When Gloria Ladson-Billings set out in the 1990s to adapt critical race theory from law to education, she couldn’t have predicted that it would become the focus of heated school debates today.

Over the past couple years, the scrutiny of critical race theory — a theory she pioneered to help explain racial inequities in education — has become heavily politicized in school communities and by legislators. Along the way, it has also been grossly misunderstood and used as a lump term about many things that are not actually critical race theory, Ladson-Billings says.

“It's like if I hate it, it must be critical race theory,” Ladson-Billings says. “You know, that could be anything from any discussions about diversity or equity. And now it's spread into LGBTQA things. Talk about gender, then that's critical race theory. Social-emotional learning has now gotten lumped into it. And so it is fascinating to me how the term has been literally sucked of all of its meaning and has now become 'anything I don't like.'”

In this week’s Harvard EdCast, Ladson-Billings discusses how she pioneered critical race theory, the current politicization and tension around teaching about race in the classroom, and offers a path forward for educators eager to engage in work that deals with the truth about America’s history.

TRANSCRIPT:

Jill Anderson: I'm Jill Anderson. This is the Harvard EdCast.

Gloria Ladson-Billings never imagined a day when the words critical race theory would make the daily news, be argued over at school board meetings, or targeted by legislators. She pioneered an adaptation of critical race theory from law to education back in the 1990s. She's an educational researcher focused on theory and pedagogy who at the time was looking for a better way to explain racial disparities in education.

Today the theory is widely misunderstood and being used as an umbrella term for anything tied to race and education. I wondered what Gloria sees as a path forward from here. First, I wanted to know what she was thinking in this moment of increased tension and politicization around critical race theory and education.

Well, if I go back and look at the strategy that's been employed to attack critical race theory, it actually is pretty brilliant from a strategic point of view. The first time that I think that general public really hears this is in September of '20 when then president and candidate Donald Trump, who incidentally is behind in the polls, says that we're not going to have it because it's going to destroy democracy. It's going to tear the country apart. I'm not going to fund any training that even mentions critical race theory.

And what's interesting, he says, "And anti-racism." Now he's now paired two things together that were not really paired together in the literature and in practice. But if you dig a little deeper, you will find on the Twitter feed of Christopher Rufo, who is from the Manhattan Institute, two really I think powerful tweets. One in which he says, "We're going to render this brand toxic." Essentially what we're going to do is make you think, whenever you hear anything negative, you will think critical race theory. And it will destroy all of the, quote, cultural insanities. I think that's his term that Americans despise. There's a lot to be unpacked there, which Americans? Who is he talking about? What are these cultural insanities? And then there's another tweet in which he says, "We have effectively frozen the brand." So anytime you think of anything crazy, you think critical race theory. So he's done this very effective job of rendering the term, in some ways without meaning. It's like if I hate it, it must be critical race theory.

You know, that could be anything from any discussions about diversity or equity. And now it's spread into LGBTQA things. Talk about gender, then that's critical race theory. Social emotional learning has now got lumped into it. And so it is fascinating to me how the term has been literally sucked of all of its meaning and has now become anything I don't like.

Jill Anderson: Can you break it down? What is critical race theory? What isn't it?

Gloria Ladson-Billings: Let me be pretty elemental here. Critical race theory is a theoretical tool that began in legal studies, in law schools, in an attempt to explain racial inequity. It serves the same function in education. How do you explain the inequity of achievement, the racial inequity of achievement in our schools?

Now let's be clear. The nation has always had an explanation for inequity. Since 1619, it's always had a explanation. And indeed from 1619 to the mid 20th century, that explanation was biogenetic. Those people are just not smart enough. Those people are just not worthy enough. Those people are not moral enough.

In fact across the country, we had on college and university campuses, programs and departments in eugenics. If you went to the World's Fair or the World Expositions back in the turn of the 20th century, you could see exhibits with, quote, groups of people from the best group who was always white and typically blonde and blue eyed, to the worst group, which is typically a group of Africans, generally pygmies. So the idea is you can rank people. So we've always had an explanation for why we thought inequity exists.

Somewhere around the mid 20th century, 1950s, you'll get a switch that says, well, no, it's really not genetic it's that some groups haven't had an equal opportunity. That was a powerful explanation. So one of the things that you begin to see around mid 1950s is legislation and court decisions, Brown versus Board of Education. You start to see the Voters Rights Act. You see the Civil Rights Act. You see affirmative action going into the 1960s. And yeah, I think that's a pretty good, powerful explanatory model.

Except they all get rolled back. 1954, Brown v. Board of Education . How many of our kids are still in segregated schools in 2022? So that didn't hold. Affirmative action. The court's about to hear that, right? Because of actually the case that's coming out of Harvard. Voters rights. How many of our states have rolled back voters rights? You can't give a person a bottle of water who was waiting in line in Georgia. We're shrinking the window for when people can vote.

So all of the things that were a part of the equality of opportunity explanation have rolled away. Critical race theory's explanation for racial inequality is that it is baked into the way we have organized the society. It is not aberrant. It's not one of those things that we all clutch our pearls and say, "Oh my God, I can't believe that happened." It happens on a regular basis all the time. And so that's really one of the tenets that people are uncomfortable hearing. That it's not abnormal behavior in our society for people to react in racist ways.

Jill Anderson: My understanding is that critical race theory is not something that is taught in schools. This is an older, like graduate school level, understanding and learning in education, not something for K–12 kids, not something my kid's going to learn in elementary school.

Gloria Ladson-Billings: You're exactly right. It is not. First of all, kids in K12 don't need theory. They need some very practical hands-on experiences. So no, it's not taught in K12 schools. I never even taught it as a professor at the University of Wisconsin. I didn't even teach it to my undergraduates. They had no use for it. My undergraduates were going to be teachers. So what would they do with it? I only taught it in graduate courses. And I have students who will tell you, "I talked with Professor Ladson-billings about using critical race theory for my research," and she looked at what I was doing and said, "It doesn't apply. Don't use it."

So I haven't been this sort of proselytizer. I've said to students, if what you're looking at needs an explanation for the inequality, you have a lot of theories that you can choose from. You can choose from feminist theory. That often looks at inequality across gender. You could look at Marx's theory. That looks at inequality across class. There are lots of theories to explain inequality. Critical race theory is trying to explain it across race and its intersections.

Jill Anderson: We're seeing this lump definition falling under critical race theory, where it could be anything. It could be anti-racism, diversity and equity, multicultural education, anti-racism, cultural [inaudible 00:09:15]. All of it's being lumped together. It's not all the same thing.

Gloria Ladson-Billings: Well, and in some ways it's proving the point of the critical race theorists, right? That it's kind normal. It's going to keep coming up because that's the way you see the world. I mean, here's an interesting lumping together that I think people have just bought whole cloth. That somehow Nikole Hannah-Jones' 1619 is critical race theory. No, it's not.

No. It. Is. Not. It is a journalist's attempt to pull together strands of a date that we tend to gloss over and say, here are all the things were happening and how the things that happened at this time influenced who we became. It's really interesting that people have jumped on that. And there is another book that came out, and it also came out of a newspaper special from the Hartford Courant years ago called Complicity. That book is set in New England and it talks about how the North essentially kept slavery going.

And when it was published by the Hartford Courant, Connecticut, and particularly Hartford said, we want a copy of this in every one of our middle and high schools to look out at what our role has been. Because the way we typically tell you our history is to say, the noble and good North and then the backward and racist South. Well, no, the entire country was engaged in the slave trade. And it benefited folks across the nation.

That particular special issue, which got turned into a book hasn't raised an eyebrow. But here comes Nikole Hannah-Jones. And initially, of course, she won a Pulitzer for it and people were celebrating her. But it's gotten lumped into this discussion that essentially says you cannot have a conversation about race.

What I find the most egregious about this situation is we are taking books out of classrooms, which is very anti-democratic. It is not, quote, the American way. And so you're saying that kids can't read the story of Ruby Bridges. It's okay for Ruby Bridges at six years old to have to have been escorted by federal marshals and have racial epithets spewed at her. It's just not okay for a six year old today to know that happened to her. I mean, one of the rationales for not talking about race, I don't even say critical race theory, but not talking about race in the classroom is we don't want white children to feel bad.

My response is, well great, but what were you guys in the 1950s and sixties when I was in school. Because I had to sit there in a mostly white classroom in Philadelphia and read Huckleberry Finn , with Mark Twain with a very liberal use of the n-word. And most of my classmates just snickering. I'd take it. I'd read it. It didn't make me feel good. I had to read Robinson Crusoe . I had to read Margaret Mitchell's Gone With The Wind . I had to read Heart Of Darkness .

All of these books which we have canonized, are books of their time. And they often make us feel a particular kind way about who we are in this society. But all of a sudden one group is protected. We can't let white children feel bad about what they read.

Jill Anderson: I was reading your most recent book, Critical Race Theory in Education, a Scholars Journey , and I was struck by when you started to do this work and this research, and adapt it from law back in the early 1990s. You talked about presenting this for the first time, or one of the first times. And there was obviously a group excited by it, a group annoyed by it. I look at what's happening now and I see parents and educators. Some are excited by a movement to teach children more openly and honestly about race. And then there's going to be those who are annoyed by it. You've been navigating these two sides your whole life, your whole career. So what do you tell educators who are eager, and open, and want to do this work, but they're afraid of the opposition?

Gloria Ladson-Billings: Well, I think there's a difference between essentially forcing one's ideas and agenda on students, and having kids develop the criticality that they will need to participate in democracy. And whenever we have pitched battles, we've been talking about race, but we've had the same kind of conversation around the environment, right? That you cannot be in coal country telling people that coal is bad, because people are making their living off of that coal. So we've been down this road before.

What I suggest to teachers is, number one, they have to have good relationships with the parents and community that they are serving, and they need to be transparent. I've taught US History for eighth graders and 11th graders before going into academe, and we've had to deal with hard questions. But there's a degree to which the community has always trusted that I had their students' best interests at heart, that I want them to be successful, that I want them to be able to make good decisions as citizens.

That's the bigger mission, I think, of education. That we are not just preparing people to go into the workplace. We are preparing people to go into voting booths, and to participate in healthy debate. The problem I'm having with critical race theory is I'm having a debate with people who don't know what we're debating. You know, I told one interview, I said, "It's like debating a toddler over bedtime. That's not a good debate." You can't win that debate. The toddler doesn't understand the concept. It's just that I don't want to do it.

I will say following the news coverage that I don't believe that all of these people out there are parents. I believe that there is a large number of operatives whose job it is to gin up sentiment against any forward movement and progress around racial equality, and equity, and diversity.

You know, to me, what should be incensing people was what they saw in Charlottesville, with those people, with those Tiki torches. What should be incensing people is what they saw January 6th. People lost their lives in both of those incidents. Nobody's lost their lives in a critical race theory discussion. You know?

I'm someone who believes that debate is healthy. And in fact debate is the only thing that you can have in a true democracy. The minute you start shutting off debate, the minute you say that's not even discussable, then you're moving towards totalitarianism. You know? That's what happened in the former Soviet Union and probably now in Russia. That's what has happened in regimes that say, no other idea is permitted, is discussable. And that's not a road that I think we should be walking here.

Jill Anderson: I feel like we're getting lost in the terminology, which we've talked about. And for school leaders, I wonder if the conversation needs to start with local districts in their communities debunking, or demystifying, or telling the truth about what critical race theory is, that kids aren't learning it in the schools. That that's not what it's about. Does it not even matter at this point because people are always going to be resistant to the things that you just even mentioned?

Gloria Ladson-Billings: I'm a bit of a sports junkie, so I'll use a sports metaphor here. I'm just someone who would rather play offense than defense. I think if you get into this debate, you are on the defensive from the start. For me, I want to be on the offense. I want to say, as a school district, here are our core values. Here's what we stand for. Many, many years ago when I began my academic career, I started it at Santa Clara University, which is a private Catholic Jesuit university. And students would sometimes bristle at the discussions we would have about race and ethnicity, and diversity and equality.

And I'd always pull out the university's mission statement. And I'd say, "You see these words right here around social justice? That's where I am with this work. I don't know what they're doing at the business school on social justice, but I can tell you that the university has essentially made a commitment it to this particular issue. Now we can debate whether or not you agree with me, but I haven't pulled this out of thin air."

So if I'm a school superintendent, I want to say, "Here are core values that we have." I'm reminded of many years ago. I was supervising a student teacher. It was a second grade. And she had a little boy in a classroom and they were doing something for Martin Luther King. It might have been just coloring in a picture of him with some iconic statement. And this one little boy put a big X on it. And she said, "Why did you do that?" And his response was, "We don't believe in Martin Luther King in my house." So she said, "Wow, okay, well, why not?" And he really couldn't articulate. She says, "Well, tell me, who's your friend in this classroom?" And one of the first names out of his mouth was a little Black boy.

And she said, "Do you know that he's a lot like Martin Luther King? You know, he's a little boy. He's Black." She was worried about where this was headed and didn't know what to do as a student teacher, because she's not officially licensed to teach at this point. And I shared with her our strategy. I said, "Why don't you talk with your cooperating teacher about what happens and see what she says. If she doesn't seem to want to do anything, casually mention, don't go marching to the principal's office. But when you have a chance to interact with the principal, you might say something I had the strangest encounter the other day and then share it." Well, she did that.

The principal called the parents in and said, "Your child is not in trouble, but here's what you need to know about who we are and what we stand for."

Jill Anderson: Wow.

Gloria Ladson-Billings: You know? And so again, it wasn't like let's have a big school board meeting. Let's string up somebody for saying something. It wasn't tearing this child down. But it was reiterating, here are our core values. I think schools can stand on this. They can say, "This is what we stand for. This is who we are." They don't ever have to mention the word critical race theory.

The retrenchment we are seeing in some states, I think it was a textbook that they were going to use in Texas that essentially described enslaved people as workers. That's just wrong. That's absolutely wrong. And I can tell you that if we don't teach our children the truth, what happens when they show up in classes at the college level and they are exposed to the truth, they are incensed. They are angry and they cannot understand, why are we telling these lies?

We don't have to make up lies about the American story. It is a story of both triumph and defeat. It is a story of both valor and, some cases, shame. Slavery actually happened. We trafficked with human beings, and there's a consequence to that. But it doesn't mean we didn't get past it. It doesn't mean we didn't fight a war over it, and decide that's not who we want to be.

Jill Anderson: What's the path forward? What can we do to make sure that students are supported and learning about their own history so that they are prepared to go out into a diverse global society?

Gloria Ladson-Billings: I'm perhaps an unrepentant optimist, because I think that these young people are not fooled by this. You know, when they started, quote, passing bans and saying, "We can't have this and we won't have this," I said, "Nobody who's doing this understands anything about child and adolescent development." Because how do you get kids to do something? You tell them they can't do.

So I have had more outreach from young people asking me, tell me about this. What is this? These young people are burning up Google looking for what is this they're trying to keep from us? So I have a lot of faith in our youth that they are not going to allow us to censor that. Everything you tell them, they can't read, those are the books they go look for. You know, I have not seen a spate in reading like this in a very long time.

So I think it's interesting that people don't even understand something as basic as child development and adolescent development. But I do think that the engagement of young people, which we literally saw in the midst of the pandemic and the post George Floyd, the incredible access to information that young people have will save us. You know, it's almost like people feel like this is their last bastion and they're not going to let people take whatever privilege they see themselves having away from them. It's not sustainable. Young people will not stand for it.

Jill Anderson: Well, I love that. And it's such a great note to end on because it feels good to think that there is a path forward, because right now things are looking very scary. Thank you so much.

Gloria Ladson-Billings: Well, you're quite welcome. And I will tell you, again sports metaphor, I'm an, again, unrepentant 76ers fan. I realize you're in Massachusetts with those Celtics. But trust me, the 76ers. Okay? One of my favorite former 76ers is Allen Iverson and he has a wonderful line, I believe when he was inducted into the Hall of Fame. He said, "My haters have made me great."

Well, I will tell you that I had conceived of that book on critical race theory well before Donald Trump made his statement in September of 2020. And I thought, "Okay, here's another book which will sell a modest number of copies to academics." The book is flying off the shelves. Y'all keep talking about it. You're just making me great.

Jill Anderson: Maybe it will start the revolution that we need.

Gloria Ladson-Billings: Well, thank you so much.

Jill Anderson: Thank you. Gloria Ladson-billings is a professor emerita at the University of Wisconsin at Madison. She is the author of many books, including the recent Critical Race Theory in Education, a Scholar's Journey . I'm Jill Anderson. This is the Harvard EdCast produced by the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Thanks for listening.

An education podcast that keeps the focus simple: what makes a difference for learners, educators, parents, and communities

Related Articles

Disrupting Whiteness in the Classroom

Exploring Equity: Race and Ethnicity

The role that racial and ethnic identity play with respect to equity and opportunity in education

The Need for Asian American History in Schools

Advertisement

Artificial intelligence in K-12 education

- Original Paper

- Published: 14 July 2022

- Volume 2 , article number 113 , ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Helen Crompton ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1775-8219 1 &

- Diane Burke ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8214-0386 2

911 Accesses

4 Citations

Explore all metrics

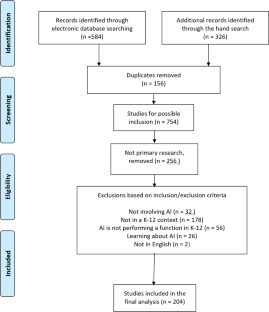

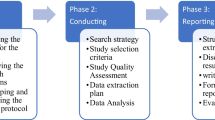

Artificial intelligence (AI) is heralded as a technology holding many unique affordances to K-12 teaching and learning. The purpose of this study was to examine how AI has been used to support teaching and learning in the K-12 context. Specifically examining the affordances for K-12 educators and students. A thematic systematic review methodology was used with PRISMA principles to examine peer review journal articles from 2010 to 2020. This thematic systematic review revealed four themes of how AI was being used by educators to support student learning: Student Monitoring, Group Management, Automated Grading, and Data-Driven Decisions. The Group Management theme included three sub-themes as AI specifically supported educators with group formation, group moderation, and group facilitation. In the examination of affordances for students, three overarching themes emerged. AI was used for AI tutors, to extend student thinking and Just-for-You-Learning which provided a bespoke learning experience built on students’ strengths and weaknesses, preferences, and interests.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Artificial Intelligence in K-12 Education: eliciting and reflecting on Swedish teachers' understanding of AI and its implications for teaching & learning

A systematic review of teaching and learning machine learning in K-12 education

Designing for Complementarity: Teacher and Student Needs for Orchestration Support in AI-Enhanced Classrooms

Data availability.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Adamson D, Dyke G, Jang H, Rose CP (2014) Towards an agile approach to adapting dynamic collaboration support to students’ needs. Int J Artif Intell Educ 24:92–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2016.02.010

Article Google Scholar

Alberola JM, del Val E, Sanchez-Anguix V, Palomares A, Teruel DM (2016) An artificial intelligence tool for heterogeneous team formation in the classroom. In: Leondes C (ed) Knowledge-based systems, vol 101. Elsevier, London, pp 1–14

Google Scholar

Baek C, Doleck T (2020) A bibliometric analysis of the papers published in the journal of artificial intelligence in education from 2015–2019. Int J Learn Anal Artif Intell Educ 2(1):67–84. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijai.v2i1.14481

Baker T, Smith L, Anissa N (2019) Educ-AI-tion rebooted? Exploring the future of artificial intelligence in schools and colleges. Nesta Foundation. https://www.nesta.org.uk/report/education-rebooted/ . Accessed 9 Feb 2021

Barshay J (2017) What kids can learn when blocks get a tech boost. KQED News. https://www.norilla.com/press/ . Accessed 9 Feb 2021

Bernacki ML, Crompton H, Greene JA (2020) Towards convergence of mobile and psychological theories of learning. Contemp Educ Psy 60:101828. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2019.101827

Blanchard EG (2015) Socio-cultural imbalances in AIED research: investigations, implications, and opportunities. Int J Artif Intell Educ 25:204–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-014-00

Britten N, Campbell R, Pope C, Donovan J, Morgan M, Pill R (2002) Using meta ethnography to synthesize qualitative research: a worked example. J Health Serv Res Policy 7(4):209–215

Brown M (2012) Learning analytics: Moving from concept to practice. EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative. http://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/ELIB1203.pdf . Accessed 9 Feb 2021

Byrd G (2016) IEEE/IBM Watson student showcase. IEEE Computer Society. https://www.computer.org/csdl/mags/co/2016/01/mco2016010102.pdf . Accessed 9 Feb 2021

Chakroun B, Miao F, Mendes V, Domiter A, Fan H, Kharkova I, Holmes W, Orr D, Jermol M, Issroff K, Park J, Holmes K, Crompton H, Portales P, Orlic D, Rodriguez S (2019) Artificial intelligence for sustainable development: synthesis report, mobile learning week 2019. UNESCO, Paris

Chassignol M, Khoroshavin A, Klimova A, Bilyatdinova A (2018) Artificial intelligence trends in education: a narrative view. Procedia Comput Sci 136:16–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2018.08.233

Chen L, Chen P, Lin Z (2020) Artificial intelligence in education: a review. IEEE Access 8:75264–75278. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2988510

COSN (2018) Artificial intelligence in the classroom: Privacy considerations for new technologies. COSN. https://cosn.org/about/news/cosn-issues-guidance-ai-classroom . Accessed 15 March 2021

Crompton H (2015) A theory of mobile learning. In: Khan BH, Ali M (eds) International handbook of e-learning, vol 2. Routledge, New York, pp 309–319

Crompton H, Song D (2021) The potential of artificial intelligence in higher education. Revista Virtual Universidad Católica del Norte 62:1–4. https://doi.org/10.35575/rvucn.n62a1

Crompton H, Bernacki M, Greene J (2020) Psychological foundations of emerging technologies for teaching and learning in higher education. Curr Opin Psych 36:101–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.04.011

Douglas T, James A, Earwaker L, Mather C, Murray S (2020) Online discussion boards: improving practice and student engagement by harnessing facilitator perceptions. J Univ Teach Learn Pract 17(3):86–100

de Laat M, Chamrada M, Wegerif R (2008) Facilitate the facilitator: Awareness tools to support the moderation to facilitate online discussions for networked learning. In: Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Networked Learning 2008:80–86

Edwards BI, Cheok AD (2018) Why not robot teachers: artificial intelligence for addressing teacher shortage. App Artif Intell 32(4):345–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/08839514.2018.1464286

Feng HH, Saricaogle A, Chekharev-Hudilainen E (2016) Automated error detection for developing grammar proficiency of ESL learners. Comput Assist Lang Instr Consort J 33(1):49–70. https://doi.org/10.1558/cj.v33i1.26507

Foltz PW, Streeter LA, Lochbaum KE, Landauer TK (2013) Implementation and applications of intelligent essay assessor. In: Schermis M, Burstein J (eds) Handbook of automated essay evaluation. Routledge, New York, pp 66–88

Górriz JM, Ramírez J, Ortíz A, Martínez-Murcia FJ, Segovia F, Suckling J, Leming M, Zhang YD, Álvarez-Sánchez JR, Bologna G, Bonomini P, Casado FE, Charte D, Charte F, Contreras R, Cuesta-Infante A, Duro RJ, Fernández-Caballero A, Fernández-Jover E et al (2020) Artificial intelligence within the interplay between natural and artificial computation: advances in data science, trends and applications. Neurocomputing 410:237–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2020.05.078

Hegelheimer V, Dursun A, Li Z (2016) Automated writing evaluation in language teaching: theory, development, and application. Comput Assist Lang Instr Consort J 33(1):2056–9017

Hemingway P, Brereton N (2009) What is a systematic review? In: Hayward Medical Group (ed). http://www.medicine.ox.ac.uk/bandolier/painres/download/whatis/syst-review.pdf . Accessed 15 March 2021

Holstein K, McLaren BM, Aleven V (2018) Student learning benefits of a mixed-reality teacher awareness tool in AI-enhanced classrooms. In: Rosé C, Martínez-Maldonado R et al (eds) Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education (AIED 2018). LNAI 10947 Springer, New York, pp 154–168

Hrastinski S, Olofsson AD, Arkenback C, Ekström S, Ericsson E, Fransson G, Jaldemark J, Ryberg T, Oberg LM, Fuentes A, Gustafsson U, Humble N, Mozelius P, Sundgren M, Utterberg M (2019) Critical imaginaries and reflections on artificial intelligence and robots in postdigital K-12 education. Postdigital Sci Educ 1(2):427–445. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-019-00046-x

Hwang GJ, Xie H, Wah BW, Gašević D (2020) Vision, challenges, roles and research issues of artificial intelligence in education. Comput Educ: Artif Intell 1:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2020.100001

Joshi N (2017) 4 ways big data is transforming the educational sector. https://www.allerin.com/blog/4-ways-big-data-is-transforming-the-education-sector . Accessed 15 March 2021

Kabudi T, Pappas I, Olsen DH (2021) AI-enabled adaptive learning systems: a systematic mapping of the literature. Comput Educ: Artif Intell 2:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2021.100017

Luckin R, Holmes W, Forcier LB, Griffiths M (2016) Intelligence unleashed: an argument for AI in education. https://www.pearson.com/content/dam/corporate/global/pearson-dot-com/files/innovation/Intelligence-Unleashed-Publication.pdf . Accessed 9 Feb 2021

McKeachie WJ, Pintrich PR, Lin Y, Smith DA (1986) Teaching and learning in the college classroom: a review of the research literature (1986) and November 1987 supplement. National Center for Research to Improve Postsecondary Teaching and Learning (ED 314 999)

McLaren BM, Scheuer O, Miksatko J (2010) Supporting collaborative learning and e-discussions using artificial intelligence techniques. Int J Artif Intell Educ 20(1):1–46. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAI-2010-0001

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart L (2015) Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 4(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

Muehlenbrock M (2006) Learning group formation based on learner profile and context. International Journal on eLearning 5(1):19–24. Chesapeake, VA: association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE). https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/21767/ . Accessed 9 Feb 2021

Nouri J, Ebner M, Ifenthaler D, Saqr M, Malmberg J, Khalil M, Brunn J, Viberg O, Conde Gonzalez MA, Papamitsiou Z, Berthelsen UD (2019) Efforts in Europe for data-driven improvement of education—A review of learning analytics research in seven countries. Int J Learn Anal Artif Intell Educ 1(1):8–27. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijai.v1i1.11053

Nye BD (2015) Intelligent tutoring systems by and for the developing world: a review of trends and approaches for educational technology in a global context. Int J Artif Intell Educ 25(2):177–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-014-0028-6

O’Shea T, Self J (1986) Learning and teaching with computers: the artificial intelligence revolution. Prentice Hall Prof Tech Ref. https://doi.org/10.5555/576781

Oakley A (2012) Foreword. In: Gough D, Oliver S, Thomas J (eds) An introduction to systematic reviews. Sage, London, pp vii–x

Park IW, Han J (2016) Teachers’ views on the use of robots and cloud services in education for sustainable development. Clust Comput 19(2):987–999. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10586-016-0558-9

Picciano AG (2014) Big data and learning analytics in blended learning environments: benefits and concerns. Int J Artif Intell Interact Multimed 2(7):35–43. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAI-2010-0001

Plakans L, Gebril A (2013) Using multiple texts in an integrated writing assessment: source text use as a predictor of score. J Second Lang Writ 22(3):217–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2013.02.003

Pokrivcakova S (2019) Preparing teachers for the application of AI-powered technologies in foreign language education. J Lang Cult Educ 7(3):135–153. https://doi.org/10.2478/jolace-2019-0025

Popenici SAD, Kerr S (2017) Exploring the impact of artificial intelligence on teaching and learning in higher education. Res Pract Tech Enhanc Learn. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41039-017-0062-8

Rodríguez-Triana MJ, Prieto LP, Vozniuk A, Boroujeni MS, Schwendimann BA, Holzer A, Gillet D (2017) Monitoring, awareness, and reflection in blended technology enhanced learning: a systematic review. Int J Tech Educ 9(2–3):126–150

Saldana J (2015) The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage, Washington DC

Samani T, Porayska-Pomsta K, Luckin R (2017) Bridging the gap between high and low performing students through performance learning online analysis and curricula. In: André E, Baker R, Hu X et al (eds) Artificial intelligence in education AIED 2017. Lecture notes in computer science, vol 10331. Springer, London. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-61425-0_82

Chapter Google Scholar

Sandelowski M, Voils CI, Leeman J, Crandell JL (2012) Mapping the mixed methods-mixed research synthesis terrain. J Mix Methods Res 6(4):317–331. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689811427913

Schleicher A (2015) Schools for 21st-century learners: strong leaders, confident teachers, innovative approaches. International Summit on the Teaching Profession. OECD Publishing, Paris, pp 650–655. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264231191-en

Book Google Scholar

Sharma RC, Kawachi P, Bozkurt A (2019) The landscape of artificial intelligence in open, online, and distance education: promises and concerns. Asian J Dist Educ 14(2):1–2

Strauss A, Corbin J (1995) Grounded theory methodology: an overview. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS (eds) Handbook of qualitative research. Sage, Los Angeles, pp 273–285

Tansomboon C, Gerard L, Vitale J, Linn M (2017) Designing automated guidance to promote productive revision of science explanations. Int J Artif Intell Educ 27(4):729–757. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-017-0145-0

Tissenbaum M, Matuk C, Berland M, Lyons L, Cocco F, Linn M, Plass JL, Hajny N, Olsen A, Schwendimann B, Boroujeni MS, Slotta JD, Vitale J, Gerard L, Dillenourg P (2016) Real-time visualization of student activities to support classroom orchestration. Symposium conducted at the 12th Int Conf Learning Sciences, Singapore, pp 1043–1044

Tissenbaum M, Slotta JD (2019) Developing a smart classroom infrastructure to support real-time student collaboration and inquiry: a 4-year design study. Instr Sci 47:423–462. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-019-09486-1

Wiley J, Hastings P, Blaum D, Jaeger A, Hughes S, Wallace P, Griffen T, Britt M (2017) Different approaches to assessing the quality of explanations following a multiple-document inquiry activity in science. Int J Artif Intell Educ 27(4):758–790. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-017-0138-z

Zawacki-Richter O, Marín VI, Bond M, Gouverneur F (2019) Systematic review of research on artificial intelligence applications in higher education—where are the educators? Int J Educ Tech Higher Educ 16(1):1–27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-019-0171-0

Download references

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Teaching and Learning, Old Dominion University, 145 Education Building, Norfolk, VA, 23529, USA

Helen Crompton

Education Division, Keuka College, Keuka Park, NY, 14478, USA

Diane Burke

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Helen Crompton .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Research involving human rights

This study did not involve human subjects.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Crompton, H., Burke, D. Artificial intelligence in K-12 education. SN Soc Sci 2 , 113 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-022-00425-5

Download citation

Received : 02 February 2021

Accepted : 05 July 2022

Published : 14 July 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-022-00425-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Artificial Intelligence

- AI in Education

- Smart technologies

- Educational technology

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

New evidence of the benefits of arts education

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, brian kisida and bk brian kisida assistant professor, truman school of public affairs - university of missouri @briankisida daniel h. bowen dhb daniel h. bowen assistant professor, college of education and human development - texas a&m university @_dhbowen.

February 12, 2019

Engaging with art is essential to the human experience. Almost as soon as motor skills are developed, children communicate through artistic expression. The arts challenge us with different points of view, compel us to empathize with “others,” and give us the opportunity to reflect on the human condition. Empirical evidence supports these claims: Among adults, arts participation is related to behaviors that contribute to the health of civil society , such as increased civic engagement, greater social tolerance, and reductions in other-regarding behavior. Yet, while we recognize art’s transformative impacts, its place in K-12 education has become increasingly tenuous.

A critical challenge for arts education has been a lack of empirical evidence that demonstrates its educational value. Though few would deny that the arts confer intrinsic benefits, advocating “art for art’s sake” has been insufficient for preserving the arts in schools—despite national surveys showing an overwhelming majority of the public agrees that the arts are a necessary part of a well-rounded education.

Over the last few decades, the proportion of students receiving arts education has shrunk drastically . This trend is primarily attributable to the expansion of standardized-test-based accountability, which has pressured schools to focus resources on tested subjects. As the saying goes, what gets measured gets done. These pressures have disproportionately affected access to the arts in a negative way for students from historically underserved communities. For example, a federal government report found that schools designated under No Child Left Behind as needing improvement and schools with higher percentages of minority students were more likely to experience decreases in time spent on arts education.

We recently conducted the first ever large-scale, randomized controlled trial study of a city’s collective efforts to restore arts education through community partnerships and investments. Building on our previous investigations of the impacts of enriching arts field trip experiences, this study examines the effects of a sustained reinvigoration of schoolwide arts education. Specifically, our study focuses on the initial two years of Houston’s Arts Access Initiative and includes 42 elementary and middle schools with over 10,000 third- through eighth-grade students. Our study was made possible by generous support of the Houston Endowment , the National Endowment for the Arts , and the Spencer Foundation .

Due to the program’s gradual rollout and oversubscription, we implemented a lottery to randomly assign which schools initially participated. Half of these schools received substantial influxes of funding earmarked to provide students with a vast array of arts educational experiences throughout the school year. Participating schools were required to commit a monetary match to provide arts experiences. Including matched funds from the Houston Endowment, schools in the treatment group had an average of $14.67 annually per student to facilitate and enhance partnerships with arts organizations and institutions. In addition to arts education professional development for school leaders and teachers, students at the 21 treatment schools received, on average, 10 enriching arts educational experiences across dance, music, theater, and visual arts disciplines. Schools partnered with cultural organizations and institutions that provided these arts learning opportunities through before- and after-school programs, field trips, in-school performances from professional artists, and teaching-artist residencies. Principals worked with the Arts Access Initiative director and staff to help guide arts program selections that aligned with their schools’ goals.

Our research efforts were part of a multisector collaboration that united district administrators, cultural organizations and institutions, philanthropists, government officials, and researchers. Collective efforts similar to Houston’s Arts Access Initiative have become increasingly common means for supplementing arts education opportunities through school-community partnerships. Other examples include Boston’s Arts Expansion Initiative , Chicago’s Creative Schools Initiative , and Seattle’s Creative Advantage .

Through our partnership with the Houston Education Research Consortium, we obtained access to student-level demographics, attendance and disciplinary records, and test score achievement, as well as the ability to collect original survey data from all 42 schools on students’ school engagement and social and emotional-related outcomes.

We find that a substantial increase in arts educational experiences has remarkable impacts on students’ academic, social, and emotional outcomes. Relative to students assigned to the control group, treatment school students experienced a 3.6 percentage point reduction in disciplinary infractions, an improvement of 13 percent of a standard deviation in standardized writing scores, and an increase of 8 percent of a standard deviation in their compassion for others. In terms of our measure of compassion for others, students who received more arts education experiences are more interested in how other people feel and more likely to want to help people who are treated badly.

When we restrict our analysis to elementary schools, which comprised 86 percent of the sample and were the primary target of the program, we also find that increases in arts learning positively and significantly affect students’ school engagement, college aspirations, and their inclinations to draw upon works of art as a means for empathizing with others. In terms of school engagement, students in the treatment group were more likely to agree that school work is enjoyable, makes them think about things in new ways, and that their school offers programs, classes, and activities that keep them interested in school. We generally did not find evidence to suggest significant impacts on students’ math, reading, or science achievement, attendance, or our other survey outcomes, which we discuss in our full report .

As education policymakers increasingly rely on empirical evidence to guide and justify decisions, advocates struggle to make the case for the preservation and restoration of K-12 arts education. To date, there is a remarkable lack of large-scale experimental studies that investigate the educational impacts of the arts. One problem is that U.S. school systems rarely collect and report basic data that researchers could use to assess students’ access and participation in arts educational programs. Moreover, the most promising outcomes associated with arts education learning objectives extend beyond commonly reported outcomes such as math and reading test scores. There are strong reasons to suspect that engagement in arts education can improve school climate, empower students with a sense of purpose and ownership, and enhance mutual respect for their teachers and peers. Yet, as educators and policymakers have come to recognize the importance of expanding the measures we use to assess educational effectiveness, data measuring social and emotional benefits are not widely collected. Future efforts should continue to expand on the types of measures used to assess educational program and policy effectiveness.

These findings provide strong evidence that arts educational experiences can produce significant positive impacts on academic and social development. Because schools play a pivotal role in cultivating the next generation of citizens and leaders, it is imperative that we reflect on the fundamental purpose of a well-rounded education. This mission is critical in a time of heightened intolerance and pressing threats to our core democratic values. As policymakers begin to collect and value outcome measures beyond test scores, we are likely to further recognize the value of the arts in the fundamental mission of education.

Related Content

Brian Kisida, Bob Morrison, Lynn Tuttle

May 19, 2017

Joan Wasser Gish, Mary Walsh

December 12, 2016

Anthony Bryk, Jennifer O’Day, Marshall (Mike) Smith

December 21, 2016

Education Policy K-12 Education

Governance Studies

Brown Center on Education Policy

Annelies Goger, Katherine Caves, Hollis Salway

May 16, 2024

Sofoklis Goulas, Isabelle Pula

Melissa Kay Diliberti, Elizabeth D. Steiner, Ashley Woo

- Our Mission

Equity in Schools Begins With Changing Mindsets

A new book explores how school leaders can foster equity by building a culture where teachers and students see their purpose and experience success.

The single variable that best predicts students’ sense of belonging is their relationship with teachers. This is more important than their race, socioeconomic status, academic achievement, and their relationships with peers. Strong teacher-student relationships can mitigate the cumulative effects of misbehavior, apathy, and failure due to poor teacher-student relationships. By improving students’ motivation, engagement, academic self-regulation, and overall achievement, teacher-student relationships offer schools continual opportunities to support students’ learning.

Such support is both interpersonal and instructional. Qualitative interviews reveal students’ preferences for teachers who respect them (i.e., don’t yell, pronounce their names properly), trust them, and don’t police minor behaviors (e.g., head on desk, sitting sideways in a chair). They like it when teachers initiate help so that they don’t have to ask questions and risk embarrassment in front of peers. When they perform well, they expect positive feedback. When they are not doing well, they appreciate teachers who communicate about their progress and offer opportunities to improve.

Teachers who fail to connect with students interpersonally or instructionally may be disengaged from their teacher role. While teachers report leaving schools because of a lack of administrative leadership, they also report job dissatisfaction because of students. Student tardiness, student absenteeism, class cutting, student dropouts, poor student health, and student apathy contribute to teachers’ lack of professional enthusiasm. These factors are compounded by teachers’ complaints about high poverty and low family involvement. Because of the correlation between race and income in the United States, these variables are present in most schools serving minoritized youth where cultural mismatch between teachers and students further complicates the development of strong teacher-student bonds (discussed in Chapter 5). This is not to say that students from underserved communities will never experience a strong sense of belonging. On the contrary, students whose schools are committed to inclusion will naturally feel welcomed and appreciated.

Framing Equity

Cultivating a school climate for equity requires careful attention to the creation of emotional, cognitive, and behavioral spaces throughout the school. It is useful to think of the climate through three lenses (L.S. Shulman, “Signature Pedagogies in the Professions,” 2005):

- Habits of heart—core values; why do you teach?

- Habits of head—ways of thinking and knowing; what do you believe?

- Habits of hand—what you do; how do you practice your values and beliefs?

These habits will be enacted differently through interactions with students versus staff, but for each, the goal is to foster their motivation to perform to the best of their abilities by creating an environment where they want to be, where they see the purpose in being, and where they experience success. An expectancy-value theory of motivation (J. Eccles et al., “Expectancies, Values, and Academic Behaviors,” 1983) offers four suggestions for increasing intrinsic motivation:

1. Create a space where people enjoy themselves and can do things that interest them. For students, this means a variety of course options, multiple extracurricular activities, and innovative, hands-on learning experiences. For teachers this may mean variety in teaching assignments, autonomous decision-making, and opportunities to develop new classes.

2. Keep your revised equity-focused vision and mission at the core of school functioning. Clearly and consistently communicate your vision and explain how every decision contributes to the realization of the vision. The key here is transparency and honesty when explaining the utility of a particular assignment or class to students, and a new policy to staff.

3. Affirm everyone’s contribution to the school community. This could be asking students to facilitate lessons or be peer mentors. You might invite staff to lead an initiative or promote them into a new position.

4. Minimize emotional costs by making sure that role expectations are reasonable (i.e., that the outcome will be worth the effort), that they leave time for other enjoyable tasks, and that they do not engender negative emotions. Students and staff should not be given busywork, be overworked, or be asked to do things which they are not capable of doing.

Each of these contributes to a positive school climate because it recognizes and leverages individuality, acknowledges accomplishments, and encourages continual engagement in the school community. School leaders can mistakenly put the climate on autopilot thinking that it will run on its own once people understand their role and are given their scripts. But a school climate is dynamic, open to influence from a variety of sources, so it must be consistently monitored and adjusted. Most importantly, because it is largely people who both shape and are shaped by the school climate, they too must be nurtured.

School Policies

Conversations about educational equity begin with policies because they determine what is and what is not allowed in schools. Many educators, students, and families interpret policies as if they are laws when, in fact, they are not. Policies are guidelines used to achieve specific goals. They are locally determined and implemented at the discretion of relevant decision-makers. In the United States, education is overseen by individual states that pass most decision-making to local educational agencies (LEAs) or school districts. Most education policies originate from school districts overseen by a school board composed of 4–10 elected or appointed volunteers. School leaders have flexibility about when and how to implement district policies.

The problem with policies is that they are written as one-size-fits-all guidelines, which, while equal, is not equitable. Inequities are exacerbated by school staff’s inconsistent application of policies such that implicit biases and explicit prejudices mean some students are disproportionately subject to school policies whereas others are not. The most frequently cited policy that is inequitably enforced is zero tolerance school discipline policies. Though initially proposed at the national level in response to school shootings, since its inception in 1994, zero tolerance has expanded beyond weapons to minor infractions such as dress-code violations and subjective offenses like disrupting class, offensive language, and disrespectful behavior. In schools designed according to White sociocultural norms, it is BISOC—Black, Indigenous, and students of color—who experience disproportionate rates of detention, suspension, and expulsion.

Consequently, racially minoritized students, especially Black and Latinx students, miss critical learning opportunities. The Civil Rights Project (2020) found that in one academic year, U.S. students lost 11 million days of instruction due to suspensions. When suspension data is disaggregated by race and gender, Black boys lost 132 days per 100 students enrolled and Black girls lost 77 days per 100 students, 7 times higher than White girls.

It is important to emphasize that discipline policies themselves are not automatically inequitable. The biased implementation of them is what creates discipline gaps that sustain opportunity gaps. This is true of most education policies, especially academic ones. For instance, tracking and sorting dictate students’ opportunities to learn (OTLs) by placing them on an educational path that restricts the courses in which they can enroll in the future. The existence of academic courses with varying levels of rigor is not in itself problematic. The issue lies in how students are placed into certain courses.

It is common for individual teachers to use their discretion to decide which students can succeed in which tracks and make recommendations for placements. Teachers’ perceptions are informed by their observations and interpretations of students’ behavior, and their assessment of their academic work compared to other students. Academic sorting methods are exceedingly subjective and worrisome. As with discipline policies, teachers’ biases against BISOC, students with disabilities, and boys means that White and Asian girls are those most often enrolled in gifted programs. Even when school policies require academic testing for course placement, students can be incorrectly sorted because standardized tests are culturally biased, lack predictive validity, and do not account for children’s cognitive variability.

This is especially true for English language learners (ELLs), who, after being assessed in English, are frequently sorted into academic tracks that do not reflect their true capabilities. Some multilingual students are mainstreamed into courses with English-speaking students and are pulled out for intensive English instruction. Others experience full English immersion and receive no English instruction. In both cases, students are given far fewer OTLs because they are not receiving instruction in their heritage language and, in the case of pull-out programs, are missing content area instruction while receiving English language instruction.

Academic policies should enhance educational opportunities, not limit them. Whether students experience reduced OTLs because their school simply does not offer certain courses, they are prevented from enrolling in courses, or because they are absent from class, has long-term implications for their educational achievement. For example, certain courses (e.g., Algebra 1, Biology, Chemistry 1) function as prerequisites for future courses, so without the opportunity to enroll in early courses, students will never be able to advance in that subject area. Even for the same course, content variation can greatly differ across academic tracks, resulting in unequal preparation for future learning.

The cumulative nature of learning means that students’ early school experiences can and do predict future OTLs, but they do not predict students’ future abilities. It is never too late to disrupt the cycle of educational inequity by expanding students’ OTLs through equitable school policies.

Excerpted from Public School Equity: Educational Leadership for Justice , © 2022 by Manya Whitaker. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Editor’s note: Edutopia readers will receive a discount when using the link above in 2022.

- EMU Library

- Research Guides

- Scholarly Journals

- Tips for Finding Full Text

- Search Tutorial

- More Search Tutorials

- Is it a Scholarly Article?

- Education News

- Journal info, calls, rankings

- Finding Dissertations & Theses

- Find Videos

- Education Statistics

- Organizations

- Research Methods

- Citation Tutorials

- Presentation Help

- Research Help

Find Journals by Title

Find Journals & Other Periodicals by Title

Search here for journal, magazine or newspaper titles. If you're looking for articles on a topic, use the databases .

Examples: Newsweek , Journal of Educational Psychology .

Selected Education Journals

These links take you to a source with recent issues of the journal. Additional issues may be available via other sources. Use Find Journals by Title (above) to find alternate sources for a title.

- AERA Open "A peer-reviewed, open access journal published by the American Educational Research Association (AERA)."

- Afterschool Matters An open access peer-reviewed journal from the National Institute on Out-of-School Time.

- American Educational Research Journal AERJ "publishes original empirical and theoretical studies and analyses in education that constitute significant contributions to the understanding and/or improvement of educational processes and outcomes." A blind peer reviewed journal from the American Educational Research Association.

- American Journal of Education Sponsored by the Pennsylvania State College of Education, this peer reviewed journal publishes articles "that present research, theoretical statements, philosophical arguments, critical syntheses of a field of educational inquiry, and integrations of educational scholarship, policy, and practice."

- Australian Journal of Teacher Education This open access peer- reviewed journal publishes research related to teacher education.

- Child Development "As the flagship journal of the Society for Research in Child Development (SRCD), Child Development has published articles, essays, reviews, and tutorials on various topics in the field of child development since 1930." Uses blind peer review.

- Cognition and Instruction This peer reviewed journal publishes articles on the "rigorous study of foundational issues concerning the mental, socio-cultural, and mediational processes and conditions of learning and intellectual competence." Articles are sometimes blind reviewed.

- Comparative and International Education This open access peer-reviewed journal "is published twice a year and is devoted to publishing articles dealing with education in a comparative and international perspective."

- Computers and Education Publishes peer reviewed articles on the use of computing technology in education.

- Contemporary Educational Psychology "publishes articles that involve the application of psychological theory and science to the educational process."

- Current Issues in Emerging eLearning (CIEE) "an open access, peer-reviewed, online journal of research and critical thought on eLearning practice and emerging pedagogical methods."

- Democracy and Education Open access peer-reviewed journal "seeks to support and sustain conversations that take as their focus the conceptual foundations, social policies, institutional structures, and teaching/learning practices associated with democratic education."

- Developmental Review This peer reviewed journal "emphasizes human developmental processes and gives particular attention to issues relevant to child developmental psychology."

- Education 3-13: International Journal of Primary, Elementary and Early Years Education This official publication of the Association for the Study of Primary Education (ASPE) publishes peer reviewed articles related to the education of children between the ages of 3-13.

- Educational Administration Quarterly This peer reviewed journal from the University Council for Educational Administration (UCEA) offers conceptual and theoretical articles, research analyses, and reviews of books in educational administration."

- Educational and Psychological Measurement "scholarly work from all academic disciplines interested in the study of measurement theory, problems, and issues."

- Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis EEPA "publishes scholarly articles of theoretical, methodological, or policy interest to those engaged in educational policy analysis, evaluation, and decision making." Blind peer reviewed journal from the American Educational Research Association.

- Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice Sponsored by the National Council on Measurement in Education, this journal promotes "a better understanding of and reasoned debate on assessment, evaluation, testing, and related issues."

- Educational Policy "focuses on the practical consequences of educational policy decisions and alternatives"

- Educational Researcher "Educational Researcher publishes scholarly articles that are of general significance to the education research community and that come from a wide range of areas of education research and related disciplines." A peer reviewed journal from the American Educational Research Association.

- Educational Research Quarterly ERQ "publishes evaluative, integrative, theoretical and methodological manuscripts reporting the results of research; current issues in education; synthetic review articles which result in new syntheses or research directions; book reviews; theoretical, empirical or applied research in psychometrics, edumetrics, evaluation, research methodology or statistics" and more. Uses blind peer review.

- Educational Research Review Publishes review articles "in education and instruction at any level," including research reviews, theoretical reviews, methodological reviews, thematic reviews, theory papers, and research critiques. From the European Association for Research on Learning and Instruction (EARLI).

- Educational Studies "publishes fully refereed papers which cover applied and theoretical approaches to the study of education"

- Education and Culture This peer reviewed journal from Purdue University Press "takes an integrated view of philosophical, historical, and sociological issues in education" with a special focus on Dewey.

- FIRE: Forum of International Research in Education This open access, peer reviewed journal promotes "interdisciplinary scholarship on the use of internationally comparative data for evidence-based and innovative change in educational systems, schools, and classrooms worldwide."

- Frontline Learning Research An official journal of EARLI, European Association for Research on Learning and Instruction. Open Access.

- Future of Children Articles on policy topics relevant to children and youth. An open access journal from the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University and the Brookings Institution.

- Harvard Educational Review "a scholarly journal of opinion and research in education. It provides an interdisciplinary forum for discussion and debate about the field's most vital issues."

- High School Journal "The High School Journal publishes research, scholarship, essays, and reviews that critically examine the broad and complex field of secondary education."

- IDEA Papers A national forum for the publication of peer-reviewed articles pertaining to the general areas of teaching and learning, faculty evaluation, curriculum design, assessment, and administration in higher education.

- Impact: A Journal of Community and Cultural Inquiry in Education A peer-reviewed, open-access journal devoted to the examination and analysis of education in a variety of local, regional, national, and transnational contexts.

- Instructional Science "Instructional Science promotes a deeper understanding of the nature, theory, and practice of the instructional process and resultant learning. Published papers represent a variety of perspectives from the learning sciences and cover learning by people of all ages, in all areas of the curriculum, and in informal and formal learning contexts." Peer reviewed.

- Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-based Learning - IJPBL This open access, peer reviewed journal "publishes relevant, interesting, and challenging articles of research, analysis, or promising practice related to all aspects of implementing problem-based learning (PBL) in K–12 and post-secondary classrooms."

- International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning An Official Publication of the International Society of the Learning Sciences

- International Journal of Educational Leadership Preparation - IJELP An open access journal from the National Council of Professors of Educational Administration. Articles undergo a double-blind peer review process.

- Internet and Higher Education Publishes peer reviewed articles "devoted to addressing contemporary issues and future developments related to online learning, teaching, and administration on the Internet in post-secondary settings."

- Journal for Research in Mathematics Education An official journal of the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM), JRME publishes peer reviewed research articles and literature reviews, as well as commentaries and book reviews. Concerned with mathematics education at both the K-12 and college level.

- Journal of Applied Research on Children - JARC Published by the CHILDREN AT RISK Institute, this open access. peer reviewed journal publishes "interdisciplinary research that is linked to practical, evidenced-based policy solutions for children’s issues."

- Journal of Computer Assisted Learning JCAL "is an international peer-reviewed journal which covers the whole range of uses of information and communication technology to support learning and knowledge exchange."

- Journal of Education A scholarly peer-reviewed journal focusing on K-12 education. This long-standing journal is sponsored by the Boston University School of Education.

- Journal of Educational Psychology This blind peer reviewed journal from the American Psychological Association publishes "original, primary psychological research pertaining to education across all ages and educational levels," as well as "exceptionally important theoretical and review articles that are pertinent to educational psychology."

- Journal of Educational Research "publishes manuscripts that describe or synthesize research of direct relevance to educational practice in elementary and secondary schools, pre-K–12."

- Journal of Interactive Media in Education - JIME This long-standing peer reviewed open access journal publishes research on the theories, practices and experiences in the field of educational technology.

- Journal of Research in Science Teaching - JRST This blind peer reviewed journal is the official journal of NARST: A Worldwide Organization for Improving Science Teaching and Learning Through Research, which "publishes reports for science education researchers and practitioners on issues of science teaching and learning and science education policy."

- Journal of Teacher Education The flagship journal of the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education (AACTE) publishes peer reviewed articles on teacher education and continued support for teachers.

- Journal of the Learning Sciences "JLS provides a multidisciplinary forum for research on education and learning as theoretical and design sciences." This official journal of the International Society of the Learning Sciences uses a double blind review process.

- Journal of Vocational Behavior "The Journal of Vocational Behavior publishes empirical and theoretical articles that expand knowledge of vocational behavior and career development across the life span. " Peer reviewed.

- Learning and Instruction This peer reviewed journal from the European Association for Research on Learning and Instruction (EARLI) publishes "advanced scientific research in the areas of learning, development, instruction and teaching."

- Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning - National Council of Professors of Educational Administration (NCPEA) Publishes "papers on all aspects of mentoring, tutoring and partnership in education, other academic disciplines and the professions."

- Merrill-Palmer Quarterly Publishes "empirical and theoretical papers on child development and family-child relationships."

- Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning MJCSL is an open-access journal focusing on research, theory, pedagogy, and other matters related to academic service-learning, campus-community partnerships, and engaged/public scholarship in higher education. Published by the University of Michigan. All articles are free online --don't worry about the "Buy a copy" messages.

- Michigan Reading Journal Open access journal from the Michigan Reading Association.

- NACADA Journal - National Academic Advising Association "The NACADA Journal is the biannual refereed journal of the National Academic Advising Association. It exists to advance scholarly discourse about the research, theory and practice of academic advising in higher education."

- Numeracy Published by the National Numeracy Network, this open access and peer reviewed journal "supports education at all levels that integrates quantitative skills across disciplines."

- Policy and Society A highly ranked open access journal that publishes peer-reviewed research on critical issues in policy theory and practice at the local, national and international levels. Includes articles on Education policy.

- Reading Research Quarterly RRQ publishes peer reviewed scholarship on literacy, including original research, theoretical and methodological essays, review articles, scholarly analysis of trends and issues, as well as reports and viewpoints. Published by the International Literacy Association.

- Review of Educational Research RER "publishes critical, integrative reviews of research literature bearing on education." A blind peer reviewed journal from the American Educational Research Association.

- Review of Higher Education Published by the Association for the Study of Higher Education this journal provides peer-reviewed research studies, scholarly essays, and theoretically-driven reviews on higher education issues.

- Review of Research in Education RRE "provides an annual overview and descriptive analysis of selected topics of relevant research literature through critical and synthesizing essays."

- Science Education "Science Education publishes original articles on the latest issues and trends occurring internationally in science curriculum, instruction, learning, policy and preparation of science teachers with the aim to advance our knowledge of science education theory and practice."

- Scientific Studies of Reading The official Journal of the Society for the Scientific Study of Reading "publishes original empirical investigations dealing with all aspects of reading and its related areas, and occasionally, scholarly reviews of the literature and papers focused on theory development. " Uses blind peer review.

- Sociology of Education "SOE publishes research that examines how social institutions and individuals' experiences within these institutions affect educational processes and social development." A blind peer reviewed journal from the American Sociological Association.

- Studies in Science Education This blind peer reviewed journal publishes review articles that offer "analytical syntheses of research into key topics and issues in science education."

- Teachers College Record "The Teachers College Record is a journal of research, analysis, and commentary in the field of education. It has been published continuously since 1900 by Teachers College, Columbia University."

- Theory into Practice "TIP publishes articles covering all levels and areas of education, including learning and teaching; assessment; educational psychology; teacher education and professional development; classroom management; counseling; administration and supervision; curriculum; policy; and technology." Peer reviewed.

- << Previous: Is it a Scholarly Article?

- Next: Education News >>

Get Research Help

Use 24/7 live chat below or:

In-person Help Summer 2024 Mon-Thur, 11am - 3pm

Email or phone replies

Appointments with librarians

Access Library and Research Help tutorials

Education Librarian

- Last Updated: May 7, 2024 2:53 PM

- URL: https://guides.emich.edu/education

Advanced search

Saved to my library.

Sustaining the Hyphens

From reproducing to restructuring teacher education.

- Puvithira Balasubramaniam University of Ottawa

With Canada’s growing population of multi-ethnic identities, fostering excellence in equity, diversity, and inclusion has become a critical priority in 21 st century education. The lived experiences of immigrant, first- and second-generation students can provide insight into the structural change that is needed to help create, sustain, and support their hyphenated identities within the higher education system. As a first-generation Tamil-Canadian, the researcher uses currere , a life writing research methodology, to analyze and synthesize their lived experience in relation to the K-12 education system and within an Ontario Teacher Education certification program. Additionally, a systematic literature review is conducted on the existing life writing works of Indigenous, Black, and/or racialized and hyphenated first and/or second-generation immigrant educators to identify patterns and trends within those lived experiences. The results yield commonalities within their educational experiences including assimilation into Western norms, misrepresentation, or erasure of non-white historical narratives and/or contributions, and an irrelevancy between academic content and students lived experiences. The research suggests that Teacher Education programs play a pivotal role in cultivating spaces that sustain future educators hyphenated identities that will later inform their teaching practices, thus, impacting healthy identity formations for their students as well.

Currere Exchange is an Open Access publication, meaning the content is free for all to access and download. Authors select a Creative Commons license to attach to their copyrightable work. Readers should identify the license attached to each work in order to determine its reuse rights.

Authors can find a copy of our publication agreement here . Authors will complete a publication agreement form as part of the submission process.

CEJ Publication Agreement: https://goo.gl/forms/k85Fq8icW78CKBO62

Information

- For Readers

- For Authors

- For Librarians

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Arts in Education: A Systematic Review of Competency Outcomes in Quasi-Experimental and Experimental Studies

Associated data.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/ Supplementary Material , further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.