1997.07.19, Medea: Essays on Medea in Myth, Literature, Philosophy and Art

Joachim vogeler , louisana state university, [email protected].

As James Clauss reminds us in the preface, this excellent collection of twelve essays on Medea grew out of a panel organized by Sarah Johnston for the 1991 meeting of the American Philological Association in Chicago. An excellent introduction by Sarah Johnston outlines the scope of this collection and provides a superb and concise summary of the twelve essays on Medea. According to Johnston, “Medea was represented by the Greeks as a complex figure, fraught with conflicting desires and exhibiting an extraordinary range of behavior” (6). After sketching Medea’s mythic history from antiquity to the twentieth century and her reception in literary and art history, Johnston explores how Medea’s complexity continues to challenge our imaginations, confront our deepest feelings, and make us realize “that behind the delicate order we have sought to impose upon our world lurks chaos” (17). Without specifying to which theories in the field of psychology she is referring, Johnston elaborates on the dichotomy of self and other which she identifies as a common element in many of the essays. A complex Medea figure unites “the opposing concepts of self and other, as she veers between desirable and undesirable behavior, between Greek and foreigner; it also allows [authors and artists] to raise the disturbing possibility of otherness lurking within self —the possibility that the ‘normal’ carry within themselves the potential for abnormal behavior, that the boundaries expected to keep our world safe are not impermeable” (8). The juxtaposition of self and other serves as the theoretical background against which Johnston contrasts the twelve essays of this collection.

In part one, entitled “Mythic Representations,” the first four essays trace the possible origins and developments of Medea as mythological figure. In part two, entitled “Literary Portraits,” the next four essays focus on the Medea figure in Pindar, Euripides, Apollonius, and Ovid. Part three, “Under Philosophical Investigation,” examines the influence Medea had on ancient philosophers who dealt with the effects of passion on the human psyche. The fourth and final part, “Beyond the Euripidean Stage,” features the influence of Euripides’ Medea on ancient vase painting and the modern stage. The editors should also be commended for compiling a very useful and extensive bibliography of almost all works cited in the papers, an index locorum, and a general index. This collection of essays on Medea displays an amazing coherence for an endeavor of this kind, and paints a very coherent and complex picture of an influential mythological figure. Most authors in this collection also make illuminating cross-references to the essays of their fellow contributors. As with any well researched project on a literary theme, scholars as well as students ought to be very pleased with a most up-to-date publication such as this 1997 work. My only point of criticism would be to note that a project taking such a comprehensive approach should be familiar with the work of Jacques Lacan, and that it would have been helpful if the editors had included a psychoanalytic investigation of Medea’s passion. Nonetheless, I expect the present volume to become a standard textbook and an obvious starting point for any students of the Medea figure. A brief survey of the twelve essays will demonstrate the scope and the quality of this project.

Fritz Graf, known for his introduction to Greek Mythology (1993), opens part one of this collection on “Mythic Representations” with an essay entitled “Medea, the Enchantress from Afar: Remarks on a Well-Known Myth.” Distinguishing between “vertical tradition” (different versions of the same mythic episode, developed over the course of centuries) and “horizontal tradition” (different versions of the same mythic episode within the same time frame), Graf furnishes an overview of Medea’s episodes in Colchis, Iolcus, Corinth, Athens, and Persia. After analyzing the themes and variations within both of these traditions and noting the consistencies and tensions between them, Graf identifies two unifying elements that tie together all the stories about Medea: her foreigness and her initiatory role. “[S]he is a foreigner, who lives outside of the known world or comes to a city from outside; each time she enters a city where she dwells, she comes from a distant place, and when she leaves the city, she again goes to a distant place” (38). Medea’s representation as the other corresponds with Johnston’s introductory remarks that, as “a geographical and cultural stranger … repeatedly exiled within Greece,” Medea implicitly demonstrates how the outsider, the other, is a threat to the inside, to the self” (14). In Graf’s second unifying theme, he identifies Medea as being “connected with a whole line of narratives that clearly are associated with initiation rites” (42). We can understand Medea as “initiatrix” when she helps Jason to overcome the dangers he must undergo in his “initiation ritual” to acquire the fleece and claim the throne back home.

In “Corinthian Medea and the Cult of Hera Akraia,” Sarah Johnston argues that no single author invented the image of the murderous mother and that fifth-century authors inherited an infanticidal Medea from the mythical tradition. This mythical figure may have been an earlier goddess of the Corinthians who “evolved out of a paradigm found in the folk beliefs of Greece and many other Mediterranean cultures—the reproductive demon, who persecuted pregnant women and young children” (14). According to Johnston, the paradigm of the reproductive demon “is likely to have been associated with the Corinthian cult of Hera Akraia” (45). As a mother who lost her children because of Hera’s refusal to protect them and help nurture them to maturity, Corinthian Medea originally emblematized the results of Hera’s neglect and/or anger (64). According to Johnston, this loss would have caused Medea to become a reproductive demon that killed other mothers’ children. At the end of Johnston’s stimulating essay, however, she has to admit that the specific reasons why the Colchian and Corinthian Medea were joined together are beyond our secure recovery (67). In an excellent essay on “Medea as Foundation-Heroine,” Nita Krevans explores Medea’s role as founder of cities. With foundations in antiquity centering primarily on male founders, the traditional roles for heroines in myth include “that of the eponymous nymph, who brings to life the metaphor of woman-as-landscape” (72), “that of the dynastic heroine, mother of a founder or of a line of local rulers” (73), and that of “the missing girl … sought by a male kinsman (or kinsmen)” (74). Often foundations are associated with a mother’s heroic child, leaving little more than a footnote for heroines. Although some foundation stories portray Medea in these traditional roles, other appearances “form a striking exception when seen against this backdrop…. [F]or every version in which she seems to follow the normal scheme, there is a variant that portrays her as a defiant anomaly” (75). With the foundation of Tomi, for example, which is associated with Apsyrtus, “we arrive at a complete inversion of the ‘kidnapped heroine’ motif” (78). Medea is the kidnapping sister, not the victim. The inversion of the gender roles sees the female as kidnapper and the male as helpless victim. Likewise, (female) Medea appears as a powerful prophet of divine status who instructs future (male) settlers about the location and destiny of their colony (78-79). The presentation of Medea in powerful, masculine roles is virtually incompatible with female fertility (80). Although Medea’s prophetic powers and divine attributes challenge the traditional boundaries between male and female, most foundation tales focus on Medea’s “extraordinary capacity for destruction” which make her “a heroine not of foundation but of annihilation” (82). Jan Bremmer’s essay asks: “Why Did Medea Kill Her Brother Apsyrtus?” rather than any other family member. After examining the specifics of this “treacherous, sacrilegious, and brutal murder” (88) as it has been described in various ancient sources, Bremmer conducts a detailed comparison of Greek sibling relationships. He concludes that brother-brother relationships and sister-sister relationships were not as close as brother-sister relationships, and it was the opposite-sex relationships on which the Greeks placed the greatest importance. In ancient (and in contemporary) Greece, “brothers [are] supposed to guard the honor, and in particular the sexual honor, of their sisters” (95). Compared with same sex sibling relationships, “brother-sister conflicts are very rare in Greek Myth” (96) and the “close contact between sisters and brothers must have continued even after the sister’s marriage” (95). “[T]he brother was responsible for the sister, and she was dependent upon him” (100). Medea’s murder of her brother Apsyrtus had such a great impact because “Medea not only committed the heinous act of spilling family blood, she also permanently severed all ties to her natal home and the role that it would normally play in her adult life. Through Apsyrtus’ murder, she simultaneously declared her independence from her family and forfeited her right to any protection from it…. There was only one way for Medea to go, then: she had to follow Jason and never look back” (100). Bremmer concludes his convincing analysis with the assumption that Medea’s fratricide elicited great feelings of horror from the Greek audience—because we hardly find any artistic representations of Apsyrtus’ murder on Greek vases (100). In “Medea as Muse: Pindar’s Pythian 4,” Dolores M. O’Higgins suggests that Pindar presents Medea as a muselike figure. In archaic Greece, people distrusted human and divine females (103-104). “For the Greeks all women were no less than a race apart. Medea most fully exemplifies the potential disloyalty present in all wives, living as necessary but suspect aliens in their husbands’ houses” (122). Foreign, female intelligence—both Medea’s and that of the Muse—had to be appropriated before the male hero, Jason, or the male poet, Pindar, could use it to his own advantage (107-108). “Traditionally, the process of song making,” O’Higgins explains, “was a joint effort…. The human bard requires a song of the Muses” (108). Pindar relied on female Muses, to create his song, and at the same time, the Muses had the capacity to dangerously intoxicate or even paralyze the poet or his audience (110). For a fuller understanding of Pythian 4, it is important to realize that Pindar also presents Medea as powerful, prophetic female, “a Muse of sorts” (114). Pindar changes the traditional parameters of the poet “as the passive vessel for information” (117), and he appropriates his Muse by basically telling her what to sing about. Pindar also appropriates Medea, the former Colchian “Muse,” who first immobilized Jason’s opponents, but then has herself fallen victim to the poetic skills of Jason—or Pindar, as O’Higgins suggests (123). “Jason ultimately may have failed in harnessing the supernatural abilities of Medea, but Pindar has not; he tames the dangerous Muse,” O’Higgins concludes (126). In “Becoming Medea: Assimilation in Euripides,” Deborah Boedeker observes that the Medea figure was not yet firmly established when Euripides composed his play. “Besides the deliberate infanticide, alternative Medeas were still possible” (127), and even within a single episode, an author was able to and ultimately had to make choices in motivating and designing the story line. Boedeker suggests that Euripides gives his protagonist her overpowering presence and canonical status by employing poetic mechanisms, namely a series of similes and metaphors, to categorize his heroine initially. During the course of the play, “Medea is gradually dissociated from such apparently obvious definitions of what she is … [and] subtly assimilated to several figures in her own story, such as Aphrodite, Jason, and the princess” (128). Medea’s implicit assimilation to other figures by mutual resemblances in diction and action gives her “an almost unbearably focused power and allows her action a certain claim to reciprocal justice” (148). “She destroys her enemies by becoming more like them, ruins them for being too much like herself. Ultimately Euripides’ Medea expands to the point where she obliterates the other characters in her myth, fully transcending—and eradicating—her own once-limited identity as woman, wife, mother, mortal” (148). Medea’s self has been consumed by the other, Johnston concludes in her introduction (11), the former victim has turned victimizer—a development for which we can both pity and fear Medea. In “Conquest of the Mephistophelian Nausicaa: Medea’s Role in Apollonius’ Redefinition of the Epic Hero,” James J. Clauss argues persuasively that Apollonius assigns Jason to the traditional role of hero, and that Medea usurps the role of “helper-maiden,” contributing to the Argonautic expedition by helping him to complete the contest (149-150). Jason, however, is not an independent hero like Heracles, who completes his contests by himself, but “thoroughly dependent on the assistance of others” (151). Jason’s brand of leadership and heroism finds its expression in “his ability to make deals with foreigners” (155). Comparing Jason and Medea to Odysseus and Nausicaa, Clauss demonstrates that Jason’s contest is not of a military kind; Medea represents his real contest and she is completely charmed by Jason’s beauty and his diplomatic skills: “To conquer Medea is to win the fleece, the opposite of the usual folktale motif, which has the young hero perform the contest to win the bride” (167). The often clueless and all too ordinary Jason ultimately succeeds as he secures the golden fleece but Apollonius’ heroism is of a different kind, with a Jason relying heavily on Medea as a powerful and indispensable “helper-maiden” (175). The implicit comparison with Nausicaa reveals Medea’s otherness who “possesses the ability to create a Heracles or destroy a man of bronze” (176). Carole E. Newlands takes a comparative approach in analyzing the dissonant structure of the full Medea story in her brilliant essay “The Metamorphosis of Ovid’s Medea.” While his Medea is initially portrayed sympathetically as a young girl whose irrational passion drives her to help Jason, in the second part of Ovid’s narrative (7.7-424), Medea appears exclusively as a witch who has lost her human characteristics. After sketching Medea’s story of the young maiden turning murderess, Newlands compares the bipartite structure of Ovid’s narrative with other marriage tales in Metamorphoses 6, 7, and 8. By juxtaposing the myths of Procne, Philomela, and Tereus (6.424-676), Scylla and Minos (8.1-151), Procris and Cephalus (7.694-862), and Boreas and Orthyia (6.677-721) with the myth of Medea, Ovid approaches urgent moral issues and offers us varying studies of the female as victim and criminal without making moral judgments. “By splitting the Medea of the Metamorphoses into two incompatible types, Ovid suggests the difficulties and inconsistencies in the rewriting of the tradition (191). … But Ovid does not explain the reason for Medea’s transformation into a sorceress and semidivine, evil being” (192), he just offers us refracted images. “Ovid adds complexity to the story of Medea by juxtaposing it with stories that are simultaneously similar and different,” Newlands concludes (207). She continues by suggesting that “Ovid’s marriage group of tales illustrates how society both denies a woman power and rejects her when she uses it” (208). By presenting two very different Medeas, Ovid creates an open-ended story that leaves the ultimate judgment to the reader. John M. Dillon’s brief essay “Medea Among Philosophers” raises many questions for the reader—as Johnston acknowledges in her introduction (10)—without providing answers. Focusing on Medea 1078-1080, Dillon shows how Euripides’ text is employed in philosophical circles to buttress the argument of different philosophical schools (215). Galen and Platonist philosophers would view Medea’s subjugation of her reason to her passion as an argument that the human tripartite soul possesses an irrational part, whereas Chrysippus and the Stoics use Medea to argue for the unity of the soul (212). Medea remains “the paradigmatic example of a disordered soul” for ancient philosophers (218), Dillon concludes. Regrettably, none of the contributors to this collection employs a psychoanalytic approach in discussing Medea’s passion and the state of her soul. “Serpents in the Soul: A Reading of Seneca’s Medea ” is an abbreviated version of chapter 12 of Martha C. Nussbaum’s book The Therapy of Desire: Theory and Practice in Hellenistic Ethics (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994). In her fascinating essay, Nussbaum argues that as an author Seneca is “an elusive, complex, and contradictory figure, a figure deeply committed both to Stoicism and to the world, both to purity and to the erotic” (246). While “Seneca’s Medea provides a clear expression of the strongest and least circular of the Stoic arguments against passion” (223), the play—and tragedy in general—are “profoundly committed to the values that Plato and Stoicism wish to reject” (247). Medea’s problem is not her love per se but her inappropriate, immoderate love for Jason. However, as Seneca tells us, there is “no erotic passion that reliably stops short of its own excess” (221). He questions the Aristotelian notion “that we can have passionate love in our lives and still be people of virtue and appropriate action” (220). Seneca argues that passionate love creates “a life of continued gaping openness to violation, a life in which pieces of the self are groping out into the world and pieces of the world are dangerously making their way into the insides of the self” (222). Extrapolating from this argument, Seneca’s Medea claims that love may even include the wish to kill. According to Nussbaum, it is not surprising that love, anger, and grief lie close to one another in the heart; these are all judgments, differing only in the precise content of the proposition, that ascribe so much importance to one unstable external being (228). Echoing Lacanian ideas, Nussbaum writes: “Desire is the beginning of the death of the self” (232). Two minor images, that of the bridle and the wave, and a central image, that of the snake, recur throughout Seneca’s play, exemplifying Medea’s passionate love. While love challenges the virtue of Stoic morality, either way of living, a life of love or a life of morality, seems to be imperfect. In her conclusion, Nussbaum returns to Seneca’s concept of mercy as a possible source of gentleness to both self and other, even when wrongdoing has been found—until rage gives way to understanding (248). Christiane Sourvinou-Inwood takes our heroine beyond the stage and investigates the dramatic and iconographical explorations of the Medea figure. In “Medea at a Shifting Distance: Images and Euripidean Tragedy,” Sourvinou-Inwood demonstrates how Euripides’ Athenian audience would perceive Medea’s character through a series of shifting relationships. Euripides constructed Medea’s character in the course of the tragedy using the three schemata of “normal woman,” “good woman” and bad woman” (254). These schemata were important crystallizations of the ancient assumptions that helped Euripides direct audience response (255). Euripides created the Medea figure by deploying a series of what Sourvinou-Inwood calls “zooming devices” and “distancing devices.” Noticing a difference in representations of Medea in Greek dress and oriental dress, Sourvinou-Inwood suggests that Medea was wearing Greek dress throughout Euripides’ play but oriental dress when she appeared in the chariot after murdering her children (289-290). The oriental dress would have enhanced the effect of distancing Medea from the Greek “good” or “normal” woman. “The change in her costume is marked by Jason’s claim, after Medea has appeared in the chariot of the Sun at [ Medea ] 1339-40, that no Greek woman would have dared to do the dreadful thing she did” (291). The zooming and distancing of Medea, the alteration of Medea in oriental dress and Medea in Greek dress allows the exploration of male fears concerning women and deconstructs the oppositional relationship between the “good Greek male self” and the “bad oriental female other” (294-296). In the end, through a series of shifting relationships, Euripides’ Medea allows the more complex perception that “the barbarian is not so different from the self” (296). The final essay in this fine collection offers a look at “Medea as Politician and Diva: Riding the Dragon into the Future.” And indeed, characterizing Medea as a revolutionary symbol, as the exploited other who may fight back, Marianne McDonald not only summarizes some of the other contributors’ main points in the closing essay but also provides a brief summary of the literary history of the various Medea dramatizations taking the reader into the twentieth century and beyond. This essay, which any scholar in comparative literature will appreciate highly, may also stimulate classicists to draw on the rich reception of the Medea theme in their teaching of the myth. McDonald contrasts the 1988 Medea play by Irish playwright Brendan Kennelly with an unpublished opera by Greek composer Mikis Theodorakis which was performed in Bilbao, Spain in 1991 and in Athens in 1993. Kennelly deals with questions of imperialism, the exploitation of women by men, Ireland by England, and he shows us a victimized Medea who victoriously fights back. Theodorakis, in contrast, emphasizes the emotional element in Medea over the rational, and “evokes Euripides’ interpretative genius through the symbolic associations of the music” (317). McDonald views Theodorakis’ opera “as another splendid example of how a modern work can elucidate this ancient text” (314). If nothing else, McDonald’s presentation raises a certain curiosity to explore these two and other modern works dealing with the Medea theme. “The twentieth century is especially rich in reworkings of this myth” (297), she claims, and the publication of the most recent Medea novel by German writer Christa Wolf, Medea: Stimmen (Munich: Luchterhand Literaturverlag, 1996) serves as another good example to support her argument. “Both Kennelly and Theodorakis,” McDonald concludes this remarkable collection of essays, “bring Euripides into modern times and into modern nations. In their own ways, they are true to Euripides and aim at the heart” (323).

(Stanford users can avoid this Captcha by logging in.)

- Send to text email RefWorks EndNote printer

Medea : essays on Medea in myth, literature, philosophy, and art

Available online, at the library.

Green Library

More options.

- Find it at other libraries via WorldCat

- Contributors

Description

Creators/contributors, contents/summary.

- Preface 1Medea, the Enchantress from Afar: Remarks on a Well-Known Myth 2Corinthian Medea and the Cult of Hera Akraia 3Medea as Foundation-Heroine 4Why Did Medea Kill Her Brother Apsyrtus? 5Medea as Muse: Pindar's Pythian 4 6Becoming Medea: Assimilation in Euripides 7Conquest of the Mephistophelian Nausicaa: Medea's Role in Apollonius' Redefinition of the Epic Hero 8The Metamorphosis of Ovid's Medea 9Medea among the Philosophers 10Serpents in the Soul: A Reading of Seneca's Medea 11Medea at a Shifting Distance: Images and Euripidean Tragedy 12Medea as Politician and Diva: Riding the Dragon into the Future Bibliography List of Contributors Index Locorum General Index.

- (source: Nielsen Book Data)

Bibliographic information

Browse related items.

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. Without cookies your experience may not be seamless.

- Medea: Essays on Medea in Myth, Literature, Philosophy, and Art

In this Book

- Edited by James J. Clauss & Sarah Iles Johnston

- Published by: Princeton University Press

From the dawn of European literature, the figure of Medea--best known as the helpmate of Jason and murderer of her own children--has inspired artists in all fields throughout all centuries. Euripides, Seneca, Corneille, Delacroix, Anouilh, Pasolini, Maria Callas, Martha Graham, Samuel Barber, and Diana Rigg are among the many who have given Medea life on stage, film, and canvas, through music and dance, from ancient Greek drama to Broadway. In seeking to understand the powerful hold Medea has had on our imaginations for nearly three millennia, a group of renowned scholars here examines the major representations of Medea in myth, art, and ancient and contemporary literature, as well as the philosophical, psychological, and cultural questions these portrayals raise. The result is a comprehensive and nuanced look at one of the most captivating mythic figures of all time. Unlike most mythic figures, whose attributes remain constant throughout mythology, Medea is continually changing in the wide variety of stories that circulated during antiquity. She appears as enchantress, helper-maiden, infanticide, fratricide, kidnapper, founder of cities, and foreigner. Not only does Medea's checkered career illuminate the opposing concepts of self and other, it also suggests the disturbing possibility of otherness within self. In addition to the editors, the contributors include Fritz Graf, Nita Krevans, Jan Bremmer, Dolores M. O'Higgins, Deborah Boedeker, Carole E. Newlands, John M. Dillon, Martha C. Nussbaum, Christiane Sourvinou-Inwood, and Marianne McDonald.

Table of Contents

- Half-title Page, Title Page

- Copyright Page, Dedication

- pp. vii-viii

- Abbreviations

- pp. xi-xiii

- Introduction

- Part I: Mythic Representations

- 1. Medea, the Enchantress from Afar

- 2. Corinthian Medea and the Cult of Hera Akraia

- 3. Medea as Foundation-Heroine

- 4. Why Did Medea Kill Her Brother Apsyrtus?

- Part II: Literary Portraits

- 5. Medea as Muse

- pp. 101-126

- 6. Becoming Medea

- pp. 127-148

- 7. Conquest of the Mephistophelian Nausicaa

- pp. 149-177

- 8. The Metamorphosis of Ovid's Medea

- pp. 178-208

- Part III: Under Philosophical Investigation

- 9. Medea among the Philosophers

- pp. 209-218

- 10. Serpents in the Soul

- pp. 219-250

- Part IV: Beyond The Euripidean Stage

- 11. Medea at a Shifting Distance

- pp. 251-296

- 12. Medea as Politician and Diva

- pp. 297-324

- Bibliography

- pp. 325-350

- List Of Contributors

- pp. 351-352

- Index Locorum

- pp. 353-368

- General Index

- pp. 369-378

Additional Information

Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Drama Criticism › Analysis of Euripides’ Medea

Analysis of Euripides’ Medea

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on July 13, 2020 • ( 0 )

When Medea, commonly regarded as Euripides’ masterpiece, was first per-formed at Athens’s Great Dionysia, Euripides was awarded the third (and last) prize, behind Sophocles and Euphorion. It is not difficult to understand why. Euripides violates its audience’s most cherished gender and moral illusions, while shocking with the unimaginable. Arguably for the first time in Western drama a woman fully commanded the stage from beginning to end, orchestrating the play’s terrifying actions. Defying accepted gender assumptions that prescribed passive and subordinate roles for women, Medea combines the steely determination and wrath of Achilles with the wiles of Odysseus. The first Athenian audience had never seen Medea’s like before, at least not in the heroic terms Euripides treats her. After Jason has cast off Medea—his wife, the mother of his children, and the woman who helped him to secure the Golden Fleece and eliminate the usurper of Jason’s throne at Iolcus—in order to marry the daughter of King Creon of Corinth, Medea responds to his betrayal by destroying all of Jason’s prospects as a husband, father, and presumptive heir to a powerful throne. She causes a horrible death of Jason’s intended, Glauce, and Creon, who tries in vain to save his daughter. Most shocking of all, and possibly Euripides’ singular innovation to the legend, Medea murders her two sons, allowing her vengeful passion to trump and cancel her maternal affections. Clytemnestra in Aeschylus’s Oresteia conspires to murder her husband as well, but she is in turn executed by her son, Orestes, whose punishment is divinely and civilly sanctioned by the trilogy’s conclusion. Medea, by contrast, adds infanticide to her crimes but still escapes Jason’s vengeance or Corinthian justice on a flying chariot sent by the god Helios to assist her. Medea, triumphant after the carnage she has perpetrated, seemingly evades the moral consequences of her actions and is shown by Euripides apotheosized as a divinely sanctioned, supreme force. The play simultaneously and paradoxically presents Medea’s claim on the audience’s sympathy as a woman betrayed, as a victim of male oppression and her own divided nature, and as a monster and a warning. Medea frightens as a female violator and overreacher who lets her passion overthrow her reason, whose love is so massive and all-consuming that it is transformed into self-destructive and boundless hatred. It is little wonder that Euripides’ defiance of virtually every dramatic and gender assumption of his time caused his tragedy to fail with his first critics. The complexity and contradictions of Medea still resonate with audiences, while the play continues to unsettle and challenge. Medea, with literature’s most titanic female protagonist, remains one of drama’s most daring assaults on an audience’s moral sensibility and conception of the world.

Euripides is ancient Greek drama’s great iconoclast, the shatterer of consoling illusions. With Euripides, the youngest of the three great Athenian tragedians of the fifth century b.c., Attic drama takes on a disturbingly recognizable modern tone. Regarded by Aristotle as “the most tragic of the poets,” Euripides provided deeply spiritual, moral, and psychological explorations of exceptional and domestic life at a time when Athenian confidence and certainty were moving toward breakup. Mirroring this gathering doubt and anxiety, Euripides reflects the various intellectual, cultural, and moral controversies of his day. It is not too far-fetched to suggest that the world after Athens’s golden age in the fifth century became Euripidean, as did the drama that responded to it. In several senses, therefore, it is Euripides whom Western drama can claim as its central progenitor.

Euripides wrote 92 plays, of which 18 have survived, by far the largest number of works by the great Greek playwrights and a testimony both to the accidents of literary survival and of his high regard by following generations. An iconoclast in his life and his art, Euripides set the prototype for the modern alienated artist in opposition. By contrast to Aeschylus and Sophocles, Euripides played no public role in the life of his times. An intellectual and artist who wrote in isolation (tradition says in a cave in his native Salamis), his plays won the first prize at Athens’s annual Great Dionysia only four times, and his critics, particularly Aristophanes, took on Euripides as a frequent tar-get. Aristophanes charged him with persuading his countrymen that the gods did not exist, with debunking the heroic, and with teaching moral degeneration that transformed Athenians into “marketplace loungers, tricksters, and scoundrels.” Euripides’ immense reputation and influence came for the most part only after his death, when the themes and innovations he pioneered were better appreciated and his plays eclipsed in popularity those of all of the other great Athenian playwrights.

Critic Eric Havelock has summarized the Euripidean dramatic revolution as “putting on stage rooms never seen before.” Instead of a palace’s throne room, Euripides takes his audience into the living room and presents the con-fl icts and crises of characters who resemble not the heroic paragons of Aeschylus and Sophocles but the audience themselves—mixed, fallible, contradictory, and vulnerable. As Aristophanes accurately points out, Euripides brought to the stage “familiar affairs” and “household things.” Euripides opened up drama for the exploration of central human and social questions embedded in ordinary life and human nature. The essential component of all Euripides’ plays is a challenging reexamination of orthodoxy and conventional beliefs. If the ways of humans are hard to fathom in Aeschylus and Sophocles, at least the design and purpose of the cosmos are assured, if not always accepted. For Euripides, the ability of the gods and the cosmos to provide certainty and order is as doubtful as an individual’s preference for the good. In Euripides’ cosmogony, the gods resemble those of Homer’s, full of pride, passion, vindictiveness, and irrational characteristics that pattern the world of humans. Divine will and order are most often in Euripides’ dramas replaced by a random fate, and the tragic hero is offered little consolation as the victim of forces that are beyond his or her control. Justice is shown as either illusory or a delusion, and the myths are brought down to the level of the familiar and the recognizable. Euripides has been described as drama’s first great realist, the playwright who relocated tragic action to everyday life and portrayed gods and heroes with recognizable human and psychological traits. Aristotle related in the Poetics that “Sophocles said he drew men as they ought to be, and Euripides as they were.” Because Euripides’ characters offer us so many contrary aspects and are driven by both the rational and the irrational, the playwright earns the distinction of being considered the first great psychological artist in the modern sense, due to his awareness of the complex motives and ambiguities that make up human identity and determine behavior.

Tragedy: An Introduction

Euripides is also one of the first playwrights to feature heroic women at the center of the action. Medea dominates the stage as no woman character had ever done before. The play opens with Medea’s nurse confirming how much Medea is suffering from Jason’s betrayal and the tutor of Medea’s children revealing that Creon plans to banish Medea and her two sons from Corinth. Medea’s first words are an offstage scream and curse as she hears the news of Creon’s judgment. The Nurse’s sympathetic reaction to Medea’s misery sounds the play’s dominant theme of the danger of passion overwhelming reason, judgment, and balance, particularly in a woman like Medea, unschooled in suffering and used to commanding rather than being commanded. Better, says the Nurse, to have no part of greatness or glory: “The middle way, neither high nor low is best. . . . Good never comes from overreaching.” Medea then takes the stage to win the sympathy of the Chorus, made up of Corinthian women. Her opening speech has been described as one of literature’s earliest feminist manifestos, in which she declares, “Of all creatures on earth, we women are the most wretched,” and goes on to attack dowries that purchase husbands in exchange for giving men ownership of women’s bodies and fate, arranged marriages, and the double standard:

When a man grows tired of his wife and home, He is free to look about for someone new. We wives are forced to count on just one man. They say, we live safe at home while men go to battle. I’d rather stand three times in the front line than bear one child!

Medea wins the Chorus’s complicit silence on her intended intrigue to avenge herself on Jason and their initial sympathy as an aggrieved woman. She next confronts Creon to persuade him to postpone his banishment order for one day so she can arrange a destination and some support for her children. Medea’s servility and deference to Creon and the sentimental appeal she mounts on behalf of her children gain his concession. After he departs, Medea reveals her deception of and contempt for Creon, announcing that her vengeance plot now extends beyond Jason to include both Creon and his daughter.

There follows the first of three confrontational scenes between Medea and Jason, the dramatic core of the play. Euripides presents Jason as a selfsatisfied rationalist, smoothly and complacently justifying the violations of his love and obligation to Medea as sensible, accepted expedience. Jason asserts that his self-interest and ambition for wealth and power are superior claims over his affection, loyalty, and duty to the woman who has betrayed her parents, murdered her brother, exiled herself from her home, and conspired for his sake. Medea rages ineffectually in response, while attempting unsuccessfully to reach Jason’s heart and break through an egotism that shows him incapable of understanding or empathy. As critic G. Norwood has observed, “Jason is a superb study—a compound of brilliant manners, stupidity, and cynicism.” In the drama’s debate between Medea and Jason, the play brilliantly sets in conflict essential polarities in the human condition, between male/female, husband/wife, reason/passion, and head/heart.

Before the second round with Jason, Medea encounters Aegeus, king of Athens, who is in search of a cure for his childlessness. Medea agrees to use her powers as a sorceress to help him in exchange for refuge in Athens. Aristotle criticized this scene as extraneous, but a case can be made that Aegeus’s despair over his lack of children gives Medea the idea that Jason’s ultimate destruction would be to leave him similarly childless. The evolving scheme to eliminate Jason’s intended bride and offspring sets the context for Medea’s second meeting with Jason in which she feigns acquiescence to Jason’s decision and proposes that he should keep their children with him. Jason agrees to seek Glauce’s approval for Medea’s apparent selfsacrificing generosity, and the children depart with him, carrying a poisoned wedding gift to Glauce.

First using her children as an instrument of her revenge, Medea will next manage to convince herself in the internal struggle that leads to the play’s climax that her love for her children must give way to her vengeance, that maternal affection and reason are no match for her irrational hatred. After the Tutor returns with the children and a messenger reports the horrible deaths of Glauce and Creon, Medea resolves her conflict between her love for her children and her hatred for Jason in what scholar John Ferguson has called “possibly the finest speech in all Greek tragedy.” Medea concludes her self-assessment by stating, “I know the evil that I do, but my fury is stronger than my will. Passion is the curse of man.” It is the struggle within Medea’s soul, which Euripides so powerfully dramatizes, between her all-consuming vengeance and her reason and better nature that gives her villainy such tragic status. Her children’s offstage screams finally echo Medea’s own opening agony. On stage the Chorus tries to comprehend such an unnatural crime as matricide through precedent and concludes: “What can be strange or terrible after this?” Jason arrives too late to rescue his children from the “vile murderess,” only to find Medea beyond his reach in a chariot drawn by dragons with the lifeless bodies of his sons beside her. The roles of Jason and Medea from their first encounter are here dramatically reversed: Medea is now triumphant, refusing Jason any comfort or concession, and Jason ineffectually rages and curses the gods for his destruction, now feeling the pain of losing everything he most desired, as he had earlier inflicted on Medea. “Call me lioness or Scylla, as you will,” Medea calls down to Jason, “. . . as long as I have reached your vitals.”

Medea’s titanic passions have made her simultaneously subhuman in her pitiless cruelty and superhuman in her willful, limitless strength and determination. The final scene of her escape in her god-sent flying chariot, perhaps the most famous and controversial use of the deus ex machina in drama, ultimately makes a grand theatrical, psychological, and shattering ideological point. Medea has destroyed all in her path, including her human self, to satisfy her passion, becoming at the play’s end, neither a hero nor a villain but a fear-some force of nature: irrational, impersonal, destructive power that sweeps aside human aspirations, affections, and the consoling illusions of mercy and order in the universe.

Share this:

Categories: Drama Criticism , Literature

Tags: Analysis of Euripides’ Medea , Bibliography of Euripides’ Medea , Character Study of Euripides’ Medea , Criticism of Euripides’ Medea , Essays of Euripides’ Medea , Euripides , Euripides’ Medea , Literary Criticism , Medea , Medea Play , Medea Play Analysis , Medea Play as a Tragedy , Medea Play Summary , Medea Play Theme , Notes of Euripides’ Medea , Plot of Euripides’ Medea , Simple Analysis of Euripides’ Medea , Study Guide of Alexander Pope's Imitations of Horace , Study Guides of Euripides’ Medea , Summary of Euripides’ Medea , Synopsis of Euripides’ Medea , Themes of Euripides’ Medea

Related Articles

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

89 Medea Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

🏆 best medea topic ideas & essay examples, 🔎 simple & easy medea essay titles, 🥇 good research topics about medea, ❓ medea essay questions.

- Significance of the Irony That Distinguishes a Tragic Hero Oedipus and Medea Oedipus’s urge to free the citizens of Thebes from the plague leads him to vow to do everything in his power to find the murderer of Laius.’The only way of deliverance from our plague is […]

- Medea’s Justification for Her Crime Medea felt Jason had betrayed her love for him and due to her desperate situation she was depressed and her normal thinking was affected that she started thinking of how she would revenge the man […]

- “Medea” by Euripides: Women Are Not Unfortunate In other words, she is trying to claim that a man’s struggles and duties are not as difficult as a woman’s hardships.

- “Blindness” Present in “Oedipus” and “Medea”: A Comparison Oedipus at the middle of the story had the urge to free the citizens of Thebes from the threat of the Sphinx.

- Conflict of the Sexes in Play “Medea” by Euripides The man cannot understand that things mean nothing to a woman if her family is being destroyed. Thus, Jason’s biggest mistake is that he thinks Medea simply wants to remain his only wife.

- “Medea” by Euripides: Tragedy Outlook There is a certain rationale in this kind of suggestions after all, Medea had gone about expressing her contempt with women’s lot on numerous occasions: “The man who was everything to me, my own husband, […]

- Medea’s Trickery and Treachery The aim of this pretense is that Medea wants Jason to come with the children to spend a night with them.

- Medea in Greek Mythology: Literary Analysis In this case, the position of kingship was the highest in political rankings, equivalent to the presidency in modern-day practices. Most importantly, the element of leadership in Greek mythology was characterized by concessions and plots.

- “The Medea of Euripides” and “Layla & Majnun” Review For instance, Jason makes a decision to divorce Medea and tie the knot with the princess of Corinth. It is important to keep in mind that the cause of all Medea’s rage is love.

- Cullingham’s “Medea” & Hall’s “Choephori”: Comparison of the Plays One of the strong points of the performance is the vocal quality; emotional, expressive and rhythmical pronunciation of the utterances transfers the mood of the actors to the audience.

- Differences in the Context: Seneca, Medea & Euripides, Medea Seneca describes the wedding in details and on this stage Medea already hates Creusa and Jason and starts thinking over her plans to take the revenge whereas in Euripides’s Medea the scene with the wedding […]

- Justice and Injustice in Medea’s and Socrates’ View The purpose of this paper is to compare and contrast how Medea and Socrates respond to injustice or unfair accusations. The following section discusses how Medea and Socrates respond or react to adversity by comparing […]

- Medea and the Epic of Gilgamesh Works Evaluating the murder of the children, the conclusion can be drawn that the females were thought to give the life and take it back.

- Medea and Antigone: Literature Comparison However, in spite of the fact that the motivations of Medea and Antigone are considered to be the same, they choose different actions.

- Greek Mythology – Medea by Euripides While the character shares certain features with some of the female leads in other Ancient Greek plays, Euripides’ Medea stands on her own as a character and represents a new set of qualities, which used […]

- A Play “Medea” by Euripides Not only has there been a gender difference between men and women in life and social environment, but extreme discrimination and external conditions of the world and governmental ruling added to the role division.

- The Driving Force of Plot in Medea by Euripides, Othello by William Shakespeare, and the Epic of Gilgamesh Reading Medea by Euripides, Othello by William Shakespeare, and The Epic of Gilgamesh it becomes obvious that the driving force of plot is heroism, however, the nature of that heroism is different that may be […]

- The Villain Comparison: Creon in Antigone and Medea in Medea From such a position the audience is allowed to examine the position of a woman in the society. What this signifies is that the woman is painted as a social misfit and this resulted in […]

- Analyzing Euripides’ Tragedy “Medea” Through the Lens of Plato and Aristotle

- “Antigone” and “Medea”: Early Feminism Works

- Barbarian Witch and Princess of Colchis: “Medea”

- Changing the Audience’s View Through the Use of Literary Devices in “Medea”

- Character Similarities Between “Medea” and “Lysistrata”

- Clytaemnestra and Medea: Two Women Seeking Justice

- Comparing “Antigone,” “Medea,” and “Nora Helmer”

- Dominance, Passivity, and Gender Roles in “Wide Sargasso Sea” and “Medea”

- Feminism and Its Role in “Medea” by Euripides

- Gender Struggles Throughout the Play “Medea”

- Comparison Between “Medea” and the “Epic of Gilgamesh”

- Honor and Revenge Before Happiness in “Medea” by Euripides

- Identifying the True Heroine in the Story “Medea”

- Jason Brings His Downfall in “Medea” by Euripides

- Attributes Traditionally Associated With Masculinity and Femininity and Their Contrasts in “Medea”

- Love and Hate According to “Medea” by Euripides

- Mask, Strength, and Revenge in “Medea” by Euripides

- Mutual Selfishness and Love Relationships in “Medea”

- Nora and Medea: Unconventional Wives in a Male-Dominated Society

- “Medea” by Euripides and Nietzsche’s Will to Power Concept

- “Oedipus Rex” and “Medea”: Leadership and Kingship

- “Medea”: Acts of Despair in a Man’s World

- Tragedy “Medea” Focused on Love, Sex, and Morality

- Shakespeare’s “Macbeth” and Euripides’ “Medea”: Comparative Analysis

- Passion Gone Too Far in “Medea”

- Race and Gender Discrimination in “Medea” and “Othello”

- “Medea”: Male and Female Perceptions of the World

- Similarities Between Aristophanes’ “Lysistrata” and Euripides’ “Medea”

- “Medea” by Euripides: Passion Versus Responsibility

- Social Change and Government Structure: “Titus Andronicus” and “Medea”

- The Anti-Hero’s Mental State in “Medea” by Euripides

- Medea’s Revenge: The Development of Her Plans

- The Chemistry Between Chorus and Medea in the Play “Medea”

- Medea’s Revenge Ultimately Makes Her Far Guiltier Than Jason

- Revenge Rather Than Justice: Euripides’ “Medea”

- The Crime and Punishment of the Female Protagonist in “Medea”

- “Medea”: The Intellectual Rhetoric and Dialogue

- The Enemy Within: The Heroine’s Downfall in Euripides’ “Medea”

- “Medea” vs. Greek Stereotypes and Gender Roles

- Medea’s Actions and Emotions in “Medea” by Euripides

- What Is Medea Known For?

- What Is Medea’s Reason for Killing Her Own Children?

- Does Medea Love Helio?

- What Is Medea the Goddess Of?

- Why Is “Medea” a Feminist Play?

- What Is the Summary of the “Medea” Story?

- Was Medea Good or Evil?

- Why Did Medea Fall in Love With Jason?

- What Is the Fatal Flaw in “Medea”?

- What Happened to Medea in the End?

- Who Was Medea in Love With?

- What Gender Is Medea?

- What Is Medea a Symbol of?

- Why Did Medea Betray Her Family?

- Who Dies at the End of “Medea”?

- What Is the Main Conflict in “Medea”?

- Is Medea in Love With Jason?

- Does Medea Regret Killing Her Children?

- Is Medea Sane or Insane?

- Did Jason Cheat on Medea?

- Who Married Medea?

- What Did Eros Do to Medea?

- Who Is the Real Tragic Hero in “Medea”?

- What Was Medea’s Mental Illness?

- Who Suffers the Most in “Medea”?

- Does Medea Forgive Jason?

- How Does Medea Get Away With Murder?

- Did Achilles Marry Medea?

- What Does the Name Medea Mean?

- Is Medea a Monster or a Victim?

- Aristotle Titles

- Gender Roles Paper Topics

- Antigone Ideas

- Orientalism Titles

- A Doll’s House Ideas

- Odysseus Ideas

- Gilgamesh Essay Topics

- Achilles Topics

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, December 8). 89 Medea Essay Topic Ideas & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/medea-essay-topics/

"89 Medea Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." IvyPanda , 8 Dec. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/medea-essay-topics/.

IvyPanda . (2023) '89 Medea Essay Topic Ideas & Examples'. 8 December.

IvyPanda . 2023. "89 Medea Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." December 8, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/medea-essay-topics/.

1. IvyPanda . "89 Medea Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." December 8, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/medea-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "89 Medea Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." December 8, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/medea-essay-topics/.

[ Skip to content ] [ Skip to main navigation ] [ Skip to quick links ] [ Go to accessibility information ]

Representing Medea: the tale of a mythical murderess

Posted 27 May 2020, by Lydia Figes

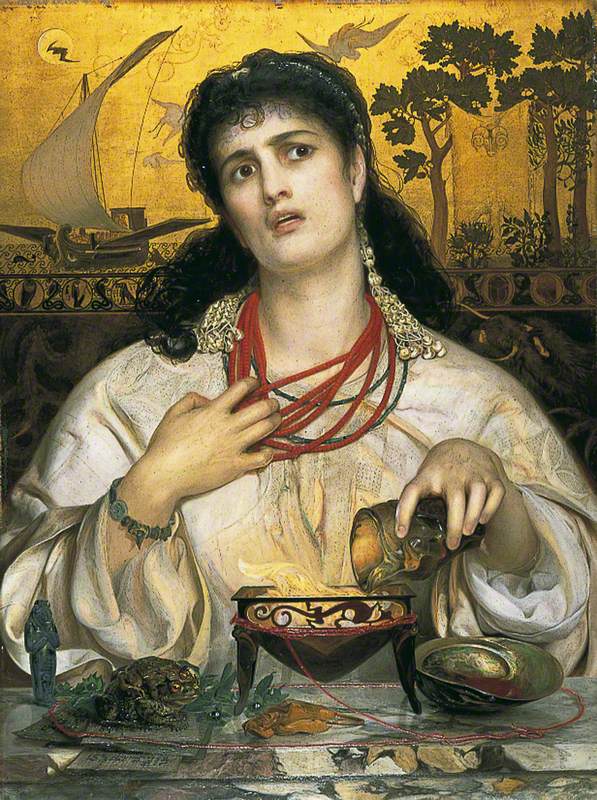

The anguished figure of Medea is the subject of Frederick Sandys ' painting of 1868. The enchantress tears at her beaded necklace while concocting a poisonous potion, with which she will use to commit murder.

Frederick Sandys (1829–1904)

An artist affiliated with the Pre-Raphaelites, Sandys submitted his work to the Royal Academy for display in the Summer Exhibition of the same year. Although agreed to be of quality, the painting was ultimately rejected, sparking controversy.

After its acceptance the following year, one critic writing for Art Journal claimed 'either by its merits or its defects, [it] certainly stands alone...' He predicted that Medea would be 'either vastly admired or supremely detested.'

Ambiguity remains as to whether Sandys' rejection was due to internal politics, or because his subject matter – a sorceress known for killing her own children – was deemed to be deplorable to members of the Academy. However the ambivalent responses to Sandys' painting reflect the historic divisiveness of the character of Medea – a woman so enraged by her deceitful husband that she commits the unthinkable. She is the ultimate embodiment of female vengeance and an archetype of the femme fatale .

Medea's tale has prompted artists to explore the following questions: did she kill her children in an impassioned fit of rage, or did she murder in cold blood? Should we regard her as an evil monstrosity? Or should she be humanised, as a wronged woman driven to madness?

Jason swearing Eternal Affection to Medea 1742-3

Jean-François de Troy (1679–1752)

Following the legend of the Golden Fleece , featuring the characters of Jason and Medea, the play Medea was written by the Greek writer Euripides and first performed in Athens in 431 BC. The Roman philosopher Seneca later adapted the tragedy in AD 50.

Medea was a princess of the barbarian kingdom of Colchis and the wife of Jason, leader of the Argonauts. Because she was a descendant of the Sun god Helios, Medea was not merely mortal, but possessed magical and prophetic powers. When she fell in love with Jason, she helped him to obtain the Golden Fleece from her father King Aeëtes, betraying her own family in the process (she killed her brother).

Jason Taming the Bulls of Aeëtes 1742

Medea lived in exile with Jason and their children in Corinth, until Jason betrayed her by marrying princess Glauce, the daughter of Creon, King of Corinth. He left Medea, who was disgraced by the affair. Medea's unquenchable desire for revenge against her husband led her to create a treacherous plot. She slyly pretended to support Jason's marriage, ingratiating herself to him, before murdering King Creon and his daughter. She also stabbed to death her children by Jason and, according to Seneca's version, tossed the bodies of her sons down the roof palace before fleeing Corinth in a chariot drawn by dragons.

An Episode from the Story of Jason and Medea

John Downman (1749–1824)

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the story of Medea experienced a particular resurgence in literature and the dramatic arts, though as early as 1556, Étienne Jodelle's ballet proper Argonautes presented the character of Medea to the court of Catherine de Médici. The French playwright Pierre Corneille dramatised her tale in 1635, influenced by the texts of Euripides and Seneca. Many musical and operatic productions followed this, including adaptions by Francesco Cavalli (1649), Marc-Antoine Charpentier (1693), Antonio Caldara (1711), and notably, Handel, whose opera Teseo (1713) centred upon the vengeful character of Medea.

Vision of Medea 1828

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851)

During the French revolutionary period, there were at least nine operas based on Medea, including Cherubini's of 1797. It has been suggested that Medea stood as a metaphor for the spirit of the French Revolution itself. In the German-speaking world, the tale inspired countless dramatists including the Austrian Franz Grillparzer who, according to historians, used Medea to launch a 'serious study in the victimisation of both womanhood and the outsider.' Grillparzer's Medea doesn't commit infanticide out of revenge, but to prevent her children from meeting a doomed fate.

Among artists, Medea was a popular mythological subject in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, during which time she was typically presented as an allegorical, feminine seductress, though in many different guises.

Around 1600, Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) created his ink drawing The Flight of Medea (in The Getty), followed by Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–1654) who, in 1620, radically depicted Medea in the moment of killing her son (in a work now in a private collection).

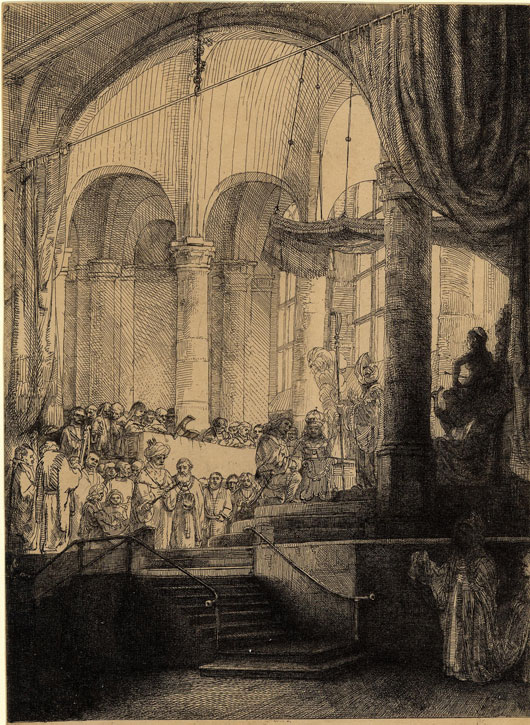

Medea, or The Marriage of Jason and Creusa

1648, etching with touches of drypoint on Japan paper by Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669)

In 1648, Rembrandt (1606–1669) created the etching Medea, or The Marriage of Jason and Creusa .

Medea Casting Spells among Ruined Sculpture c.1673

Henry Ferguson (before 1655–1730)

Not long after, the artists Henry Ferguson (1655–1730), Corrado Giaquinto (1703–1765) and Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini (1675–1741) painted the mythical enchantress too.

Medea c.1750/1752

Corrado Giaquinto (1703–1766)

Jason Rejecting Medea c.1711

Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini (1675–1741)

In 1715, Charles Antoine Coypel created this striking study of Medea's countenance in pastel, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The final painting was submitted to the Académie Royale in 1715, and depicted the climactic moment of Medea's tale, when she kills her children and escapes the wrath of Jason. It is likely that stage adaptions of the story influenced Coypel's version, which clearly has a dramatic flair.

c.1715, pastel drawing on paper by Charles Antoine Coypel (1694–1752)

By the nineteenth century, images of Medea appeared widely across Europe, and representations ambivalently emphasised her as a scorned sorceress, or wronged wife and mother.

Eugene Delacroix 's most famous depiction of 1838, titled Medea About to Murder Her Children , offers a sexualised rendering. Medea appears to hover between the role of mother and murderess – she tentatively holds the dagger close to her sons who try to escape her clutches.

Medea About to Kill her Children (Medée furieuse)

1838, oil on canvas by Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863)

The German painter Anselm Feuerbach (1829–1880) depicted Medea in 1870 (now in Munich's Neue Pinakothek), followed by Valentine Prinsep (1838–1904) in 1888, and Evelyn de Morgan (1855–1919) in 1889.

In Prinsep's depiction, Medea calmly gathers poisoned fungi from a forest floor, which she will later use to poison Glauce (Jason's new bride) and her father. In her right hand, she holds a dagger, pointing to her eventual infanticide.

Medea the Sorceress 1880

Valentine Cameron Prinsep (1838–1904)

In De Morgan's portrayal, Medea wonders the marble halls of Ancient Greece, plotting her revenge against Jason. She holds a vial of purple potion. When De Morgan exhibited this painting for the first time at the New Gallery in 1890, she accompanied the work with a William Morris poem titled The Life of Jason .

'Day by day she saw the happy time fade fast away, And as she fell from out that happiness, Again she grew to be the sorceress, Worker of fearful things, as once she was.'

In contrast to other depictions, De Morgan offers a more sympathetic interpretation of Medea, presenting her as a grieving and wronged woman, responding to her own misfortune.

Evelyn De Morgan (1855–1919)

In 1907, John William Waterhouse (1849–1917) presented Medea concocting a magical potion that will enable Jason to complete the tasks set out for him by her father King Aeëtes. Waterhouse presents Medea in a Pre-Raphaelite style. Artists associated with the Pre-Raphaelite movement shared a preoccupation with Tennysonian figures, often involving empowered female witches and enchantresses, all of whom are dangerously in control of their own sexuality.

Jason and Medea

1907, oil on canvas by John William Waterhouse (1849–1917)

Historians continue to grapple with the resurgence of interest in Medea during the nineteenth century. Some have observed that representations of Medea in culture coincided with public debates about divorce laws and the enfranchisement of women in England. In 1857, the Divorce and Matrimonial Causes Act was passed, which allowed for separation on the grounds of adultery, cruelty, or desertion.

It seems plausible that Medea was appropriated for political and proto-feminist purposes, a vehicle to talk about social and political emancipation for women. For example, in 1856, Ernest Legrouvé opened his theatrical version of Medea to Parisian audiences, a man who would be known for supporting the women's movement and for publishing essays about the status of women in France. In 1868, the female writer and advocate of women's suffrage, Augusta Webster (1837–1894) translated Euripides' Medea in an attempt to promote the tale to British audiences.

Circe resplendens 1913

Margaret Deborah Cookesley (1837–1927)

Medea also challenged preconceived notions about female sexuality. Christine Sutphin argues that mythological figures such as Circe and Medea countered the Victorian notion of female 'asexuality'. Against Coventry Patmore's conception of the ' Angel in the House ' – a submissive and self-sacrificing wife who dutifully fulfils the expectations of her husband – Medea embodied a transgressive and deviant symbol of 'womanhood', which stood in contrast to the Victorian pure ideal.

By the twentieth century, the archetype of Medea expanded beyond being a symbol of female expression, though she continued to represent discourses to do with gender. Notable filmmakers, from Pier Paolo Pasolini to Lars von Trier have adapted her tale for their own cinematic purposes. In Pasolini's 'Marxist' rendering of Medea (1969), the opera singer Maria Callas stars as the powerful enchantress (though she doesn't sing).

An enduring and powerful symbol of female rage, Medea's story has stood the test of time – it has been adapted and weaponised according to each century's defining socio-political characteristics. Consistently, the story serves a warning against betrayal, reminding us of its corrupting nature, aptly worded in Euripides' drama:

'I understand too well the dreadful act I'm going to commit, but my judgement can't check my anger, and that incites the greatest evil human beings do.'

Lydia Figes, Content Editor at Art UK

Further reading

Maria Berbara, '15 Visual Representations of Medea's Anger in the Early Modern Period: Rembrandt and Rubens', Discourses of Anger in the Early Modern Period , 2015

Deborah Boedecker, Medea: Essays on Medea in Myth, Literature, Philosophy, and Art, Princeton University Press. pp.127–148

Edith Hall, Fiona Macintosh and Oliver Taplin, Medea in Performance 1500–2000, University of Oxford, 2000

Madison Skye Lauber, 'The Murdering Mother: The Making and Unmaking of Medea in Ancient Greek Image and Text', Bard College, 2018

Betine van Zyl Smit, 'Medea the Feminist' Acta Classica , Vol. 45, 2002, pp.101–122

- The ancient Greek play Medea was written by Euripedes and first performed in 431 BC

- The Baroque Italian painter Artemisia Gentileschi explored the story of Medea in 1620

- Pre-Raphaelite artist Evelyn de Morgan also created her own version of the sorceress

- The dance pioneer Martha Graham brought the character of Medea to the stage in the twentieth century

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

More stories

by Euripides

Medea study guide.

Medea was first performed in 431 BC. Its companion pieces have been lost, but we know that this set of plays won third prize at the Dionysia, adding another disappointment to Euripides ' career. Although we know nothing of the other pieces, the character of Medea undoubtedly made the Athenian audience uncomfortable; for audiences past and present, the play is something of a shocker, nihilistic and disturbing. Of the eighty-eight or so plays Euripides wrote, only nineteen (or possibly eighteen, as the authorship of Rhesus is in doubt) survive. Medea is one of the earliest surviving plays of Euripides, though it was written well into his career. It is also one of the most popular.

The specific circumstances surrounding the origin of Greek drama were a puzzle even in the fourth century BC. Greek drama seems to have its roots in religious celebrations that incorporated song and dance. By the sixth century BC, Athenians had transformed a rural celebration of Dionysus into an urban festival with dancing choruses that competed for prizes. An anonymous poet came up with the idea of having the chorus interact with a masked actor. Later, Aeschylus transformed the art by using two masked actors, each playing different parts throughout the piece, making possible staged drama as we know it. With two actors and a chorus, complex plots and conflicts could be staged as never before, and the poets who competed in the festival were no longer writing elaborate hymns, but true plays. The playwrights were more than just writers. They also composed the music, choreographed the dances, and directed the actors. Athens was the only Greek city-state where this art form evolved; the comedies, tragedies, and dramas handed down to us from the period, although labeled generically as "Greek," are in fact all Athenian works.

After the defeat of the Persians in a decisive campaign (480-479 BC), Athens emerged as the superpower of the independent Greek city-states, and during this time, the drama festival, or the Dionysia, became a spectacular event. The Dionysia lasted four to five days, and the city took the celebrations seriously. Prisoners were released on bail and most public business was suspended. Roughly ten thousand free male citizens, along with their slaves and dependents, watched plays in an enormous outdoor theater that could seat seventeen thousand spectators. On each of three days, the Athenians were treated to three tragedies and a satyr play (a light comedy on a mythic theme) written by one of three pre-selected tragedians, as well as one comedy by a comedic playwright. The trilogies did not have to be an extended drama dealing with the same story, although often they were. At the end of the festival, the tragedians were awarded first, second, and third prize by the judges of Dionysis.

For modern readers, the Chorus may be the most alien element of the play. Greek drama was not meant to be what we would consider "naturalistic." It was a highly stylized art form: actors wore masks, and the performances incorporated song and dance. The Chorus delivers much of the exposition and expounds poetically on themes, but it is still meant to represent a group of characters. In the case of Medea, the Chorus is constituted by the women of Corinth. The relationship between the Chorus and Medea is one of the most interesting Chorus-protagonist relationships in all of Greek drama. The women are alternately horrified and enthralled by Medea: there is no question that she goes too far and commits the most horrible act possible for a mother, and for that, she earns the Chorus' pity and condemnation. And yet, they do nothing to interfere. The women live vicariously through Medea. In taking her revenge, she avenges the crimes committed against all of womankind. Powerful and fearless, Medea refuses to be wronged by men, and the Chorus cannot help but admire her.

Medea is part of the gallery of Euripides' "bad women." Euripides was often attacked for portraying what Aristotle called "unscrupulously clever" women as his main characters; he depicts his tragic heroines with far less apology than his contemporaries. We are not, as in Aeschylus' Oresteia, allowed to comfort ourselves with the restoration of male-dominated order. In Medea that order is exposed as hypocritical and spineless, and in the character of Medea, we see who a woman whose suffering, instead of ennobling her, has made her monstrous.

Consistent with the norms of Greek drama, Medea is not divided into acts or discrete scenes. However, time passes in non-naturalistic fashion: at certain points, it is clear that a considerable amount of time has passed in the world of the play even though only a few seconds have passed for the audience. In general, as noted by Aristotle, most Greek tragedies have action confined to a twenty-four hour period.

Medea Questions and Answers

The Question and Answer section for Medea is a great resource to ask questions, find answers, and discuss the novel.

How are Jason and Medea both delusional?

In his arrogance, Jason believes himself to be invincible. He believes that his ambition is more important than morality.

Medea is delusional in her belief that she and Jason share a destiny. She is also delusional in her refusal to consider the...

How are life and death shown as extensions of exile from Corinth in Medea?

One important example of life and death as an extension from exile can be found in Medea's belief that by killing her children she will save them from sharing in her fate.

How does Euripides position the audience to sympathise with Medea?

Euripides positions the audience to sympathize with Medea by presenting her as a wronged woman, who has benn cruelly and callously cast aside by the man she loves.

Study Guide for Medea

Medea study guide contains a biography of Euripides, literature essays, quiz questions, major themes, characters, and a full summary and analysis.

- About Medea

- Medea Summary

- Character List

- Lines 1-356 Summary and Analysis

Essays for Medea

Medea literature essays are academic essays for citation. These papers were written primarily by students and provide critical analysis of Medea.

- Analysis of Medea as a Tragic Character

- Medea's Identity

- Witchy Women: Female Magic and Otherness in Western Literature

- Medea: Feminism in a Man's World

- Medea and Divinity

Lesson Plan for Medea

- About the Author

- Study Objectives

- Common Core Standards

- Introduction to Medea

- Relationship to Other Books

- Bringing in Technology

- Notes to the Teacher

- Related Links

- Medea Bibliography

Wikipedia Entries for Medea

- Introduction

- Form and themes

- Modern productions and adaptations

Ask LitCharts AI: The answer to your questions

The tragedy of Medea begins in medias res (in the middle of things). Medea 's Nurse bemoans Medea's fate—she has been abandoned with her two young children by her husband, Jason, who has married the Princess , daughter of Creon , king of Corinth. In the midst of her lamentations, the Nurse recounts how Jason left his homeland, Iolocus, in a ship called the Argo to find a treasure called the Golden Fleece. The Golden Fleece was guarded by a dragon in Medea's homeland, the Island of Clochis. Aphrodite, goddess of love, made Medea fall in love with Jason and then help him to steal the Golden Fleece. While she and Jason were fleeing Clochis by boat, Medea killed her brother so that those pursuing them would have to stop and bury his body. In Iolocus, she and Jason hatched a plot to steal rulership from the king, Pelias. Medea managed to trick Pelias' daughters into killing him by promising that, if they did, she could restore him to his youth. She did not restore him, and Jason and Medea were chased from Iolocus to Corinth, where they lived as exiles.

Medea is infuriated by Jason's abandoning her and their children, and makes threats to kill Creon and the Princess. These threats reach Creon at the palace where the children's Tutor overhears that Creon intends to exile Medea from Corinth. He tells the Nurse what he heard outside Medea's house. The two promise not to tell Medea. The Nurse says she fears for the children and doesn't like the way Medea has been looking at them. She sends the children inside where, from offstage, Medea addresses them, saying she wishes they were dead and cries aloud in her grief. The Nurse and Tutor leave and the Chorus of Corinthian women assemble outside Medea's house, saying that it heard Medea cry. Medea comes out to speak to the Chorus of her troubles. Soon, the king, Creon, arrives to give Medea her sentence of banishment. He tells her he fears she will cause him and his daughter harm. She tries to convince him she is harmless, but he will not relent. Eventually she manages to get him to agree to give her a single day in which to plan where she and the children will go in their exile. When Creon is gone, Medea laughs at him and calls him a fool for allowing her to stay. She intends to punish Creon, the Princess, and Jason for the way they have mistreated her.

Next Jason comes to offer Medea money and letters of recommendation to ease the burdens of her exile. The two of them argue about Jason's behavior, and Jason contends, somewhat ridiculously, that he is acting in Medea and the children's best interest. Medea calls him a coward and refuses any help. Jason leaves. When he is gone Medea reveals her plot to kill the princess with a poisoned dress and crown , and then, in order to hurt Jason most, to also kill her own (and Jason's) children. But first she must find a place of refuge for after she leaves Corinth. Her friend, Aegeus, the king of Athens, soon arrives on his way from the oracle of Phoebus whom he has consulted concerning his inability to have children. Medea promises him that she will help him to have children if he promises to shelter her from her enemies. He agrees and exits.

Medea sends a member of the Chorus to fetch Jason back. When he comes, she tells him he was right and she is only a foolish woman and begs him to find some way to let the children stay. She sends the children with Jason to the palace to give the Princess the dress and crown as gifts. They go.

The Tutor soon comes from the palace with the children and with the good news that the children are allowed to stay. Medea grieves because, for her, it means the Princess is dead or dying and she must complete her plan by killing the children. A Messenger arrives from the palace and recounts the Princess and Creon's death in vivid detail. The Princess died putting on the gifts, and Creon died by becoming entangled in the poisoned dress after embracing his daughter's corpse. Medea relishes the news and steels herself to murder her children. She takes them offstage (inside) and we hear them struggle. Jason comes to the house and commands his men to undo the bolts of the door . Before he can manage, Medea appears over the stage in a chariot drawn by chimeras sent by the sun god, Helios, her grandfather. She has with her the dead bodies of her children. She and Jason exchange cutting remarks about the tragic events, and the Chorus concludes the play by saying that sometimes, rather than expected events, the gods bring unexpected things to pass.

58 pages • 1 hour read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more. For select classroom titles, we also provide Teaching Guides with discussion and quiz questions to prompt student engagement.

Section Summaries & Analyses

Lines 1-287

Lines 288-749

Lines 750-1397

Character Analysis

Symbols & Motifs

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Discussion Questions

You are an up-and-coming divorce lawyer in ancient Corinth. Choose to represent either Jason or Medea and argue why your client is least to blame in their separation and its aftermath. Use textual examples and be sure to frame your argument in ancient—not modern—terms.

Select one of the Chorus’s poetic monologues to the audience . How does what the Chorus says embody what we feel about the action on stage? Do you agree with the Chorus’s assessment of the situation in the passage you chose? Why or why not?

There are two king characters in Medea : Creon , the king of Corinth, and Aegeus , the king of Athens. Creon attempts to banish Medea; Aegeus extends her the promise of safety in Athens. Which man is a better king to his people? In the world of Medea , what virtues constitute a good ruler? Are they different from our own?

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Related Titles

By Euripides

Ed. John C. Gilbert, Euripides

Iphigenia in Aulis

The Bacchae

Trojan Women

Featured Collections

Ancient Greece

View Collection

Challenging Authority

Tragic Plays

Medea - Free Essay Samples And Topic Ideas

Medea is an ancient Greek tragedy by Euripides, centered on the character of Medea, who seeks revenge against her unfaithful husband Jason. Essays on “Medea” could explore the themes of passion, revenge, and the roles of gender and social status within the play. Discussions might delve into the character analysis of Medea and Jason, the play’s critique of ancient Greek society, and Euripides’ use of dramatic techniques. Moreover, analyzing the enduring relevance of “Medea,” its various adaptations, and its influence on the tragedy genre can provide a thorough examination of this classic narrative and its impact on literature and drama. We have collected a large number of free essay examples about Medea you can find at Papersowl. You can use our samples for inspiration to write your own essay, research paper, or just to explore a new topic for yourself.

Is Medea a Tragic Hero?

The story of Medea has is often debated by modern scholars, to which they are trying to assign who is the true tragic hero in the story. Greek audiences used to conclude that Jason was the tragic hero. However, now it is argued that Madea better demonstrates the real tragic hero in the story. Is Medea a Tragedy? The term hero is obtained from a Greek word that means a person who faces misfortune, or displays courage in the face […]

Euripides’ Medea as a Sympathetic Character

While no one condones Medea's actions, one can sympathize with her unappreciated sacrifices and investments in Jason's ascension, her suffering at the hands of Jason's pride and hubris, and future of a scorned and divorced woman in Greek Society. The action follows as Medea argues her position with the chorus, Creon and Jason. Medea's magic enabled Jason to defeat the impossible task to reclaim his birthright. Yet, when the opportunity arose with a new marriage, Jason's pride enables him to […]

Three Traits of the Golden Age of Athens in Literature

The beginning of the Golden Age of Greece or Athens started with the Persian war, when the Persian army was defeated by Greeks. One of the main defining features of the Golden Age of Athens are that Law comes from men not the gods as we can see in the book of Antigone, another one is explaining history through the actions of people not the gods, as we can see in the book Odyssey, and the last one is focusing […]

We will write an essay sample crafted to your needs.

Relationship of Jason, Creon and Medea

During romance, men promise more fancy things to women to win their affection. Sometimes these men can even take an oath to earn the women's confidence and trust. However, some of these promises are not fulfilled and thus mark the beginning of mistrust and heartbreak. The tragic story of Medea provides the consequences of broken vows. The tragedy reveals the essence of staying faithful to matrimonial vows made. The tragedy befalls on Jason because he was unable to keep the […]

The Sanctity of Oaths in Medea