There’s no shame in being materialistic – it could benefit society

Lecturer in Marketing, Lancaster University

Contributors

Professor of International Management and Marketing, Vienna University of Economics and Business

Senior Lecturer, University of Manchester

Disclosure statement

Charles Cui does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Bodo B. Schlegelmilch and Sandra Awanis do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Lancaster University provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

Materialism gets a bad press. There is an assumption that people who prioritise “things” are inherently selfish. The stereotype is that of highly materialistic people, living in a different world, where their priority is cash, possessions and status. But is the stereotype true? Our research reveals there are two sides to this story.

Highly materialistic people believe that owning and buying things are necessary means to achieve important life goals, such as happiness, success and desirability. However, in their quest to own more, they often sideline other important goals. Research shows that highly materialistic people tend to care less about the environment and other people than “non-materialists” do. These findings lead to the assumption that highly materialistic people are largely selfish and prefer to build meaningful relationships with “stuff”, as opposed to people.

But other research shows that materialism is a natural part of being human and that people develop materialistic tendencies as an adaptive response to cope with situations that make them feel anxious and insecure, such as a difficult family relationship or even our natural fear of death .

Underlying desires

Materialism is not only found in particularly materialistic people. Even referring to people as “consumers” , as opposed to using other generic terms such as citizens, can temporarily activate a materialistic mindset. As materialism researchers James Burroughs and Aric Rindfleisch said:

Telling people to be less materialistic is like telling people that they shouldn’t enjoy sex or eat fatty foods. People can learn to control their impulses, but this does not remove the underlying desires.

As such, efforts directed towards eliminating materialism (taxing or banning advertising activities ) are unlikely to be effective. These anti-materialism views also limit business activities and places considerable tension between business and policy.

The caring materialists

Our research examined how materialism is perceived across cultures and it revealed that there is more to materialism than just self-gratification. In Asia, materialism is an important part of the “collectivistic” culture (where the emphasis is on relationships with others, in particular the groups a person belongs to).

Buying aspirational brands of goods and services is a common approach in the gift-giving traditions in East Asia. Across collectivistic communities, purchasing things that mirror the identity and style of people you regard as important can also help you to conform to social expectations that in turn blanket you with a sense of belonging. These behaviours are not unique to Asian societies. It’s just that the idea of materialism in the West is more often seen in sharp contrast to community values, rather than a part of it.

We also found that materialists in general are “meaning-seekers” rather than status seekers. They believe in the symbolic and signalling powers of products, brands and price tags. Materialists who also believe in community values use these cues to shed positive light onto themselves and others they care about, to meet social expectations, demonstrate belonging and even to fulfil their perceived social responsibilities. For example, people often flaunt their green and eco-friendly purchases of Tom’s shoes and Tesla cars in public to signal desirable qualities of altruism and social concern.

Reconciling material and collective interests

So how do we get an increasingly materialistic society to care more about the greater good (such as buying more ethically-sourced products or making more charity donations) and be less conspicuous and wasteful in its consumption? The answer is to look to our culture and what sort of collectivistic values it tries to teach us.

We found that a simple reminder of the community value that resonates with who we are as a society can help reduce materialistic tendencies. That said, the Asian and Western cultures tend to teach slightly different ideals of community value. Asian communities tend to pass on values that centre around interpersonal relationships (such as family duties). Western societies tend to pass on values that are abstract and spiritual (such as kindness, equality and social justice).

Unsurprisingly, many businesses have been quick to jump onto this bandwagon. Tear-jerking commercials from Thailand reminding people to buy insurance to protect loved ones, Christmas adverts reminding viewers to be kind to one another are just two examples. But nice commercials alone won’t be enough to do the job.

Social marketers and public policymakers should tap into society’s materialistic tendencies to promote well-meaning social programmes, such as refugee settlement, financial literacy programmes and food bank donations. The key is to promote these programmes in ways that materialists can engage with – through a public display of consumption that communicates social identity.

A perfect example is the Choose Love charity pop-up store in central London, where people get to purchase real products (blankets, children’s clothing, sleeping bags, sanitary pads) in a beautifully designed retail space akin to the Apple store, which are then distributed to refugees in Greece, Iraq and Syria.

Materialism undoubtedly has an ugly face but it is here to stay. Rather than focusing efforts to diminish it, individual consumers, businesses and policymakers should focus on using it for promoting collective interests that benefit wider society.

- Consumerism

- materialism

- Black Friday

Case Management Specialist

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

- Newsletters

Site search

- Israel-Hamas war

- Home Planet

- 2024 election

- Supreme Court

- All explainers

- Future Perfect

Filed under:

- Neuroscience

- Science of Everyday Life

A psychologist explains why materialism is making you unhappy

Share this story.

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: A psychologist explains why materialism is making you unhappy

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/60141173/shutterstock_188334554.0.0.0.0.jpg)

Materialists lead unhappier lives — and are worse to the people around them. And it seems that social media might be fueling materialistic attitudes, too. This is all according to a fascinating interview the American Psychological Association posted in 2014 with Knox College psychologist Tim Kasser , whose research focuses on materialism and well-being.

Here are the best bits.

Materialists are sad, terrible people:

We know from research that materialism tends to be associated with treating others in more competitive, manipulative and selfish ways, as well as with being less empathetic ... [M]aterialism is associated with lower levels of well-being, less pro-social interpersonal behavior, more ecologically destructive behavior, and worse academic outcomes. It also is associated with more spending problems and debt ... We found that the more highly people endorsed materialistic values, the more they experienced unpleasant emotions, depression and anxiety, the more they reported physical health problems, such as stomachaches and headaches, and the less they experienced pleasant emotions and felt satisfied with their lives.

People become more materialistic when they feel insecure:

Research shows two sets of factors that lead people to have materialistic values. First, people are more materialistic when they are exposed to messages that suggest such pursuits are important ... Second, and somewhat less obvious — people are more materialistic when they feel insecure or threatened, whether because of rejection, economic fears or thoughts of their own death.

Materialism is linked to media exposure and national-advertising expenditures:

The research shows that the more that people watch television, the more materialistic their values are ... A study I recently published with psychologist Jean Twenge ... found that the extent to which a given year’s class of high school seniors cared about materialistic pursuits was predictable on the basis of how much of the U.S. economy came from advertising and marketing expenditures — the more that advertising dominated the economy, the more materialistic youth were.

Materialism is linked to social media use, too:

One study of American and Arab youth found that materialism is higher as social media use increases ... That makes sense, since most social media messages also contain advertising, which is how the social media companies make a profit.

Many psychologists think that materialists are unhappy because these people neglect their real psychological needs:

[M]aterialistic values are associated with living one’s life in ways that do a relatively poor job of satisfying psychological needs to feel free, competent and connected to other people. When people do not have their needs well-satisfied, they report lower levels of well-being and happiness, as well as more distress.

Check out the whole interview at the APA's website.

Will you support Vox today?

We believe that everyone deserves to understand the world that they live in. That kind of knowledge helps create better citizens, neighbors, friends, parents, and stewards of this planet. Producing deeply researched, explanatory journalism takes resources. You can support this mission by making a financial gift to Vox today. Will you join us?

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

Next Up In Life

Sign up for the newsletter today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

Thanks for signing up!

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

“I lost trust”: Why the OpenAI team in charge of safeguarding humanity imploded

ChatGPT can talk, but OpenAI employees sure can’t

Why are Americans spending so much?

Blood, flames, and horror movies: The evocative imagery of King Charles’s portrait

Why the US built a pier to get aid into Gaza

The controversy over Gaza’s death toll, explained

Materialism and Well-Being Revisited: The Impact of Personality

- Research Paper

- Open access

- Published: 12 February 2019

- Volume 21 , pages 305–326, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Małgorzata E. Górnik-Durose ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3395-5324 1

39k Accesses

32 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Although the negative link between materialism and well-being has been confirmed by results from many empirical studies, mechanisms underlying this association still remain partially unexplained. The issue is addressed in this article in two ways. Firstly, the nature of the components of materialism is examined, and secondly—the article demonstrates that personality (particularly neuroticism and narcissism) is one of the important factors linking materialism and well-being. The article presents the results of three empirical studies, in which three main assumptions were verified—that the components of materialism, i.e. acquisition centrality, acquisition as a pursuit of happiness and possession-defined success, have dissimilar impacts on well-being, that materialists with high and low levels of neuroticism and narcissism differ with regard to well-being, and that neuroticism and narcissism mediate the relationship between materialism and well-being. The studies were based on self-reports and utilized well-known, established questionnaire measures of materialism, personality and well-being. The results showed that each component of materialism was associated with well-being in a slightly different way. Of the three possession-defined happiness was the strongest predictor of all aspects of well-being examined and the centrality component was not associated with any of them. Materialists with a high level of neuroticism and low level of grandiose narcissism experienced diminished well-being in comparison to materialism with a low level of neuroticism and high level of grandiose narcissism. Neuroticism and grandiose narcissism were both significant mediators, acting contrary to each other—neuroticism lowered well-being, whereas grandiose narcissism elevated it.

Similar content being viewed by others

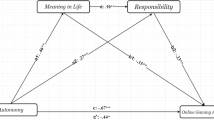

Online Gaming Addiction and Basic Psychological Needs Among Adolescents: The Mediating Roles of Meaning in Life and Responsibility

The Efficient Assessment of Self-Esteem: Proposing the Brief Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale

The tracks of my years: personal significance contributes to the reminiscence bump.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The negative association between materialism and well-being is currently almost an axiom in psychology and consumer research. In their extensive meta-analysis Dittmar et al. ( 2014 ) showed that the results of empirical studies concerning this association are consistent and indicate modest negative correlations between various measures of materialism and various aspects of well-being (the average effect is − .19). Some moderating factors (i.e. age, gender, a nation’s rate of economic growth, level of inequality, cultural and value orientations) weaken the connection somewhat, although do not eliminate it. None of them reverses the association and causes it to be positive.

Although the link between materialism and well-being seems to be evident, mechanisms underlying this association still remain partially unexplained, despite many attempts to shed light on it. In this article I would like to address the issue in two ways. Firstly, I intend to examine more closely the domains of materialism. Secondly, I aim to demonstrate that one of the major factors that bring materialism and well-being together is personality, particularly neuroticism and narcissism. Such an approach is relatively novel. Although the domains of materialism were incidentally examined in relation to well-being, there is no systematic study addressing this issue. Despite the abundance of separate empirical findings that show simple connections between materialism and well-being, materialism and personality, and personality and well-being, the connection between the three is a field of empirical investigation which has been neglected thus far. I am convinced that both matters mentioned above deserve more attention from scholars.

1.1 Materialism and Its Domains in Relation to Well-Being

The term “materialism” in psychology relates to people’s desire to acquire and possess material assets. Materialism is understood as the importance people attach to worldly possessions which take a central place in their lives and are expected to be the greatest source of satisfaction or dissatisfaction (Belk 1985 ), or as a high valuation of material goods, that are perceived as a measure of a successful and happy life (Richins and Dawson 1992 ) and a warrant of high status, power, and popularity (Kasser 2002 ).

The conceptualization of materialism, which has been most widely used in psychological studies, was proposed by Richins and Dawson ( 1992 ). They defined materialism in terms of values that direct people’s choices and behaviours in various situations and influence the way people structure their lives and relate to the external world. According to them, overall materialism incorporates three components: acquisition centrality, i.e. placing possessions and their acquisition in the center of one’s life, acquisition as a pursuit of happiness, i.e. believing that possessions and their acquisition are essential to one’s happiness, and possession-defined success, i.e. considering possession as a criterion for judging one’s own and other people’s success.

These three domains are usually combined and the overall materialism index is commonly used in various studies, including those related to materialism and well-being. Very few researchers made an effort to look at the three components of materialism separately. The exception was Ahuvia and Wong ( 1995 ), who showed that of the three the belief that possession can bring happiness was most strongly associated with life dissatisfaction; possession-defined success was also related to life dissatisfaction, but only in some areas, whereas the connection between possession centrality and life (dis)satisfaction was fairly weak and not significant. The same authors demonstrated later that the negative relationship between materialism and needs satisfaction was driven exclusively by the belief related to happiness (Ahuvia and Wong 2002 ). The similar effect of the happiness component was also revealed by Swinyard et al. ( 2001 ) and Roberts and Clement ( 2007 ). Furthermore Pieters ( 2013 ) showed that the vicious cycle of materialism and loneliness was mostly vested in the belief that possession brings happiness and in possession-defined success. Acquisition centrality played a positive role in the cycle decreasing loneliness over time. Also Segev et al. ( 2015 ) found a weak positive correlation between acquisition centrality and life satisfaction alongside a strong negative association between life satisfaction and the happiness component. Such results suggest that it is worth exploring separately the three domains of materialism in relation to well-being.

Over the years researchers were proposing various explanation of the negative relationship between overall materialism and well-being. For example, Burroughs and Rindfleisch ( 2002 ) showed that materialists experience less happiness and more negative affect than others because of the inherent conflict between material and collective values. Solberg et al. ( 2003 ) pointed to materialists’ poor social life as a source of lower well-being. They also claimed that striving for material goals provides less emotional gratification than striving for others and that people are more distant from their material goals than from others and least satisfied with what they achieve in the material realm. Shrum et al. ( 2013 ) suggested that materialism is centered on constructing identity through symbolic consumption, and because the process requires reliance on others to validate the results, it causes vulnerability and psychological instability. Dittmar et al. ( 2014 ) tested two explanations of the negative effect of overall materialism on psychological well-being. In relation to the first explanation—that materialists develop unrealistic expectations in the financial realm, which set the stage for disappointment that negatively influences other domains of well-being—the results were not conclusive. The second assumption—that materialism is connected with low needs satisfaction—was verified positively. Recently Donnelly et al. ( 2016 ) suggested that the possible processes that cause unsuccessful pursuits of happiness and satisfaction through the possession of tangible objects are driven by the urge to escape from aversive self-awareness.

Solberg et al. ( 2003 ) referred also to a different explanation of the association between materialism and low well-being—a potential link between materialism and neuroticism, i.e. the personality factor which is highly responsible for negative emotions and low well-being. They finally rejected this hypothesis, but in a later study by Górnik-Durose and Boroń ( 2018 ) the hypothesis was supported. In the current article the way of thinking, which connects materialism with well-being through personality, is continued.

1.2 Materialism and Personality

Investigating relationships between materialism and various personality traits is not a novelty in psychological research. In studies based on the Five–Factor Model of personality (cf. Costa and McCrae 1992 ) positive correlations have been found between materialism and neuroticism and negative between materialism and agreeableness. Data concerning the connections between materialism and extraversion, openness to experience and conscientiousness were not consistent across studies (see Ashton and Lee 2008 ; Otero-López and Villardefrancos 2013 ; Watson 2015 ).

Many malevolent personality traits were also examined in connection with materialism (see Hong et al. 2012 ; Pilch and Górnik-Durose 2016 ), but the personality feature which has received most attention was narcissism. Researchers point out that there are two separate forms of narcissism: grandiose and vulnerable, which share some similarities, but also differ in many ways (Wink 1991 ; Miller et al. 2011 ).They overlap in relation to a sense of personal entitlement, egocentrism, self-absorption, grandiose self-relevant fantasies, callousness, manipulativeness, willingness to exploit others and arrogance. But only grandiose narcissism embraces traits related to magnificence, dominance and aggression, whereas vulnerable narcissism is allied with defensiveness, and its illusory grandiosity disguises feelings of insecurity, inadequacy, incompetence, and negative affect (Miller et al. 2011 ). Data from various studies showed that they are both associated positively with materialism (Bergman et al. 2013 ; Rose 2007 ; Pilch and Górnik-Durose 2017 ).

The configuration of personality features related to materialism, although explicable at first sight, is de facto internally incoherent, incorporating features that are not likely to coexist. The associations between narcissism and low agreeableness and other malevolent features are understandable and supported by results of many empirical studies (e.g. Watson 2012 ; Houlcroft et al. 2012 ), but it is rather difficult to incorporate high neuroticism and high grandiose narcissism into one personality structure. The empirical data show clearly that high grandiose narcissism is accompanied by low neuroticism, or they are not connected at all (see Houlcroft et al. 2012 ; Lee et al. 2013 ; Miller et al. 2011 ). On the other hand vulnerable narcissism correlates positively and quite strongly with neuroticism (Miller et al. 2011 , Houlcroft et al. 2012 ). It is unlikely then that materialists would be both neurotic and narcissistic in a grandiose way; although it could happen in the case of vulnerable narcissism.

Such contradictions in the personality depiction of materialists inspired Górnik-Durose and Pilch ( 2016 ) to look more closely at the associations between materialism and personality traits (within the HEXACO framework). They separated two types of materialists. They both displayed relatively low levels of honesty–humility and agreeableness, but in one case the emotionality level was significantly lower and the extraversion level significantly higher than in the other. The first materialistic type was named the Peacocks, the second, the Mice. The Peacocks were also significantly more narcissistic than the Mice, but only in the grandiose way; no difference was found in vulnerable narcissism. Moreover the Peacocks and Mice had different attitudes towards money and different spending preferences. The Peacocks were prone to seek immediate financial gain, whereas the Mice were anxious and insecure in their money attitudes. Their declared spending was directed toward self-protection, whereas the Peacocks were oriented toward self-aggrandizing. The Peacocks were also more prone to ostentatious consumption than the Mice.

This short description of the Mice and Peacocks suggests that for each type being materialistic fulfills different functions. The Mice, who are rather emotionally unstable and vulnerable, with a tendency to feel anxious, fearful, insecure, use material possessions as reassurance—a “security blanket”, a means to create relatively sheltered life conditions that may protects against deprivation, hostile environmental and social threats (cf. Kasser 2002 ). Their inherent difficulties in gaining support and safe attachment to people results in turning toward more tangible resources that are easily controlled and manipulated (cf. Richins 2017 ). The Peacocks on the other hand possess highly inflated, positive views of the self, accompanied by strong self–focus, feelings of entitlement, seeking admiration and lack of regard for others. To maintain their disproportionately positive self–beliefs, narcissistic Peacocks engage in grandiose self–displays, using appropriate material possessions (Campbell and Foster 2007 ). Displaying the proper material possessions is a self–presentation tactic, which is plainly effective in consumption–oriented societies. In a culture which uses material goods extensively as a communication code, material things of proper brands and varieties—scarce, unique, exclusive, often customizable– are able to deliver appropriate messages, showing desirable personal and societal characteristics of their owner (Lee et al. 2013 ). Thus, proper material goods sustain, validate, and nurture the narcissistic self.

These two strategies—both utilizing material goods—not only serve different purpose, but also may have different consequences in relation to well-being. I assume then that the deceptively simple associations between materialism and well-being may be altered by their connections with personality.

1.3 Neuroticism, Narcissism and Well-Being

The empirical evidence that personality accurately predicts well-being was summarized by DeNeve and Cooper ( 1998 ) and Steel et al. ( 2008 ) in their meta-analyses. They also showed that among personality traits neuroticism is the most prominent factor influencing various aspects of well-being. The same was revealed by Anglim and Grant ( 2016 ). The association is indisputably negative, i.e. rising neuroticism is followed by diminishing well-being. This effect is strong and fundamental and—as Steel et al. ( 2008 ) suggest—involves common biological mechanisms or neural substrates. Neuroticism also influences behaviors and predisposes people to have more negative life experiences that have an impact on their well-being.

In the case of narcissism the empirical evidence is also quite plain—narcissism in its grandiose version elevates well-being, whereas vulnerable narcissism lowers it significantly. It was also demonstrated that narcissism is associated with well-being due to its overlap with self-esteem (Rose 2002 ; Sedikides et al. 2004 ; Zuckerman and O’Loughlin 2009 ).

The impact of personality on well-being means that any relationship between phenomena, which are connected with personality, and well-being may be shaped and transformed by personality, because personality relates to basic regulatory mechanisms and represents fundamental and relatively stable characteristics of a person that underlie individual behavior, beliefs and attitudes and are to some extent biologically determined. Haslam et al. ( 2009 ) showed that associations between values and well-being are due to the variance they both share with personality traits. This may be also the case for materialism. This is why I assumed that neuroticism and narcissism may be powerful factors mediating the relationship between materialism and well-being.

2 Current Investigation

Until now the results of empirical studies related to materialism, personality and well- being showed that:

Materialism is connected with poorer well-being and the effect seems to be mainly due to the belief that acquiring and possessing material goods is essential for happiness and that possessed assets are the best indication of achieving success in life.

Materialism is also associated with certain personality traits—particularly neuroticism and narcissism (positively). These traits distinguish types of materialists. One materialistic type—the Peacocks—is marked by low neuroticism and high grandiose narcissism, the second—the Mice—by high neuroticism and low grandiose narcissism.

Both neuroticism and narcissism correlate significantly with well-being, hence, it would be expected that they may shape well-being also in materialists. Thus far the evidence was found for a mediating role of neuroticism in the relationship between materialism and attitudes towards money and well-being (Górnik-Durose and Boron 2018 ).

The current research is embedded in the findings listed above, but its aim is to extend the investigation and clarify the associations further. It encompasses three separate studies. The objectives of Study I are to verify the assumption that materialists with different levels of neuroticism (i.e. the Mice and Peacocks) would differ in relation to well-being, and to examine further the mediating effect of neuroticism on the relationship between materialism and well-being revealed in previous research. Study II concentrates on the impact of grandiose and vulnerable narcissism on the relationship between materialism and well-being. Its first aim is to examine differences in well-being between the Mice and Peacocks that are due to the level of grandiose narcissism, the second—to test for a mediating effect of narcissism on the relationship between materialism and well-being. Study III consolidates the two aspects of personality connected with materialism analyzed in the two previous studies, i.e. neuroticism and both types of narcissism. The objective is to check how strong these traits are alongside materialism in relation to well-being. In all three studies materialism is deconstructed and the associations of its three dimensions, i.e. possession centrality, possession-defined happiness and possession-defined success, with life satisfaction and well-being is examined. In the concurrent studies different measures of well-being are utilized.

The main hypotheses tested in the three studies were as follows:

Three domains of materialism relate differently to well-being. The possession-defined happiness (MAT/Hap) and possession-defined success (MAT/Suc) are relatively strongly and negatively associated with various aspects of well-being, whereas the centrality component (MAT/Cent) correlates with well-being modestly or not at all

The Mice and Peacocks, identified on the basis of the level of neuroticism (NE) or grandiose narcissism (GN), differ in regard to various aspects of well-being. The low neurotic and high narcissistic Peacocks experience a higher level of well-being than high neurotic and low narcissistic Mice

Personality traits—neuroticism (NE), as well as grandiose (GN) and vulnerable narcissism (VN), mediate the relationship between materialism (MAT) and its two domains, i.e. possession-defined happiness (MAT/Hap) and possession-defined success (MAT/Suc) and various aspects of well-being

2.1 Study I

2.1.1 participants.

The participants were 286 adults from Upper Silesia in Poland (72.4% women) aged 17–59 (M = 25.48; SD = 7.15); 70% of the sample were younger than 26, merely students. The remaining 30% were educated on the higher (54.1%) and secondary (30.6%) levels. The information about the material situation of the participants was gathered by asking them to assess on a scale from 1 (low) to 7 (very high) their monthly income in relation to the subjectively perceived national average. In the younger group the mean score was 2.52 (SD = 1.65), whereas in the older group 3.6 (SD = 1.72).

The participants were recruited by cooperating students via their private social networks on Facebook. No incentives were given for the participation.

2.1.2 Measures

Materialism The 9-item Material Values Scale—as recommended by Richins ( 2004 ), in the Polish version by Górnik-Durose ( 2016 ) was used to measure materialism. Items were rated from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The three subscale scores (i.e. centrality, e.g. “I like a lot of luxury in my life” ; happiness, e.g. “My life would be better if I owned certain things I don’t have” ; success, e.g. “I like to own things that impress people” ) as well as the overall materialism score were computed.

Neuroticism The neuroticism scale (EPQ-N) from the revised Eysenck Personality Questionnaire EPQ-R(S) in Polish adaptation (Jaworska 2012 ) was used to measure neuroticism. It consists of 12 items with a response scale of 1 (yes) and 0 (no). Positive responses were summed to yield a total score.

Well - being Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF; Keyes 2002 ) in Polish adaptation by Karaś et al. ( 2014 ) was applied to assess well-being. MHC-SF consists of 14 items that represent hedonic (emotional—e.g. ‘‘How often did you feel happy?’’ ) and eudaimonic (psychological—e.g. ‘‘How often did you feel good at managing the responsibilities of your daily life?’’ and social—e.g. ‘‘How often did you feel that you belonged to a community?’’ ) facets of well-being. The 6-point answering scale (ranging from 1—“never” to 6—“everyday”) relates to the frequency of experiencing various symptoms of well-being during the past month. The overall (general) score of well-being (GWB) was computed and used in the analyses.

2.1.3 Results

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations between study variables are displayed in Table 1 .

2.1.3.1 Well-Being in Groups Differentiated by Materialism and Neuroticism

In the first step participants were divided into subgroups according to MAT and NE scores. The scores below average placed participants to the low MAT or low NE subgroups, the scores equal and above average placed them to the high MAT or high NE subgroups. Finally four subgroups were separated: high_MAT/high_NE (i.e. the Mice), high_MAT/low_NE (i.e. the Peacocks), low_MAT/low_NE and low_MAT/high_NE. The mean scores of well-being (GWB) were compared in those subgroups in one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey’s tests (see Table 2 ).

The tests revealed statistically significant differences between the subgroups. First of all the two highly materialistic subgroups—the Mice and Peacocks—differed significantly, with the Mice having the lowest level of GWB among participants and the Peacocks having GWB comparable to the highest well-being of the low_MAT/low_NE subgroup. The Mice on the other hand did not differ significantly from the low_MAT/high_NE subgroup.

2.1.3.2 The Mediating Effect of Neuroticism on the Relationship Between Materialism and Well-Being

In the next step the assumption about the mediating role of neuroticism in the relationship between materialism and its domains and well-being was tested. The mediation analyses were run using the bootstrapping method with bias-corrected confidence estimates. The PROCESS macro model 4 for SPSS developed by Hayes ( 2013 ) was utilized. The 95% confidence intervals (CI) of the indirect effects were obtained with 5000 bootstrap resamples. The intervals that do not contain zero indicate a significant indirect effect. Only those components of MAT that were initially significantly correlated with NE and GWB were taken into consideration (see Table 1 ). Accordingly, two separate mediation analyses were conducted: for MAT and for MAT/Hap as predictors of well-being. The results are presented in Table 3 .

Both total effects of MAT and MAT/Hap on GWB were significant. After controlling for NE the direct effects of MAT became insignificant (full mediation) and the direct effect of MAT/Hap became considerably lower, but still significant (partial mediation). Both indirect effects via NE were significant.

2.1.3.3 Summary of the Results

The results obtained in Study I were consistent with previous findings related to a simple association between MAT, NE and well-being (see Sect. 1 of this article). The differences in NE among materialists were reflected in their GWB. A salient detrimental effect of MAT and NE on GWB was revealed, with NE playing the leading role. MAT not accompanied by NE did not appear to affect GWB very much. The mediation analyses confirmed that the relationship between MAT and GWB was fully mediated by NE, whereas in the case of MAT/Hap the mediation was partial—the belief that material possessions bring happiness hold its unique negative impact on GWB alongside NE. The remaining two components of materialism did not have any significant impact on GWB.

2.2 Study II

2.2.1 participants.

A Polish sample of 123 adults (73.2% women), aged 22–70 ( M = 35.07; SD = 10.37) was used in Study II. 88.6% of the participants were educated on the higher level, 11.4%—on the secondary level. As in Study I they were asked to assess their income in relation to the national average. On the scale from 1 to 7 the mean score was 4.22 (SD = 1.49), whereas the mean of the declared monthly income was 2951 PLN (SD = 849), which was slightly above the median of income in Poland at the time of data collection, i.e. in 2016).

The participants were recruited by a cooperating student via Facebook using his social network. No incentives were given for the participation.

2.2.2 Measures

Materialism As in Study I the Polish version of the 9-item Material Values Scale was used to assess materialism.

Narcissism The Polish version of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI; Raskin and Hall 1979 ; Bazińska and Drat-Ruszczak 2000 ) was applied to measure grandiose narcissism. It consists of 34 items (e.g. “I really like to be the center of attention”, “I think I am a special person”) with the answers on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (it’s not me) to 5 (it’s me). Scores were summed to create an overall index. As a measure of vulnerable narcissism the Polish version of Hypersensitive Narcissism Scale (HSNS; Hendin and Cheek 1997 ; Czarna et al. 2014 ) was used. It consists of 10 items (e.g. “My feelings are easily hurt by ridicule or the slighting remarks of others”, “When I enter a room I often become self - conscious and feel that the eyes of others are upon me” ) answered on a 5-point scale from 1 (“very uncharacteristic or untrue/strongly disagree”) to 5 (“very characteristic or true/strongly agree”). Scores were summed to create an overall index.

Subjective Well - being In study II two aspects of subjective well-being (SWB) were assessed as suggested by Pavot and Diener ( 1993 )—satisfaction with life (SWL) and positive (PA) and negative (NA) affects. The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) developed by Diener et al. ( 1985 ) in Polish adaptation by Juczyński ( 2001 ) was used to measure the first aspect. The scale is composed of five items (e.g. “ In most ways my life is close to my ideal“ ) measuring global life satisfaction on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The total score is a sum of the participants’ responses.

The affective component of SWB was measured with the Polish version of Brief Measures of Positive and Negative Affect Scales (PANAS; Watson et al. 1988 ) in Polish adaptation (Brzozowski 2010 ). It consists of 20 adjectives, 10 denoting positive affect (e.g. “excited” ) and 10 denoting negative affect (e.g. “upset” ). Respondents indicated the extent to which each adjective described them in general, using a 1 (hardly at all) to 5 (extremely) range. Separate scores (sums) were computed for positive and negative affect.

2.2.3 Results

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations between variables are displayed in Table 4 .

2.2.3.1 Well-Being in Groups Differentiated by Materialism and Narcissism

As in Study I the participants were divided into subgroups according to MAT and—this time—GN, because—as Górnik-Durose and Pilch ( 2016 ) demonstrated—the Peacocks differ from the Mice only in relation to GN; no differences were found in VN. The scores below average placed participants in the low MAT or low GN subgroups, the scores equal and above average placed them in the high MAT or high GN subgroups. Four groups were created: high_MAT/high_GN, high_MAT/low_GN, low_MAT/low_GN and low_MAT/high_GN. The members of the high_MAT/high_GN subgroup were the equivalent of the Peacocks, and high_MAT/low_GN were the Mice. The mean scores of well-being (SWL, PA and NA) were compared in those subgroups in one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey’s test. The tests revealed statistically significant differences between the subgroups in relation to SWL and both PA and NA (see Table 2 ).

The two high MAT subgroups distinguished by the level of GN did not differ significantly in relation to any aspect of SWB. Yet the high_MAT/low_GN subgroup (the Mice) reported the lowest levels of SWL and PA in the sample. The highest level of SWL and PA was identified in the low_MAT/high_GN subgroup, which experienced also the lowest level of NA. High materialism in highly narcissistic individuals (high_MAT/high_GN subgroup) resulted in the highest level of NA, significantly higher than in the case of narcissists with low materialism.

2.2.3.2 The Mediating Effect of Narcissism on the Relationship Between Materialism and Well-Being

Finally the assumption about the mediating role of both types of narcissism in the relationship between materialism and SWB was tested. As in the previous study the PROCESS macro model 4 was utilized. The macro estimated bootstrapped bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals (CI) for indirect effects in 5000 bootstrap resamples. This time the parallel multiple mediator model was applied. The estimation of indirect effects in such a model allows for a simultaneous test of each mediator while accounting for the shared associations between them (cf. Preacher and Hayes 2008 ). As in Study I only those domains of materialism that were initially significantly correlated with at least one type of narcissism and relevant aspects of well-being were taken into consideration (see Table 4 ). Three separate mediation analyses were conducted for MAT, MAT/Hap and MAT/Suc as predictors of SWL and NA, and one for MAT/Hap as a predictor of PA. In all cases GN and VN were included in the models as parallel mediators. The results are presented in Table 3 .

The results show that total effects of materialism and its two domains on SWL and PA were significant, in the case of NA—marginally. After controlling for GN and VN the associations between MAT and SWB changed. In the case of SWL direct effects remained significant, but the coefficients were altered. For MAT and MAT/Hap the coefficients become lower due to the indirect effect of VN only (the indirect effect of GN was not significant). It suggests a partial mediation. For HAP/Suc both indirect effects were significant, but contrary to each other—the indirect effect of GN was positive, whereas the indirect effect of VN was negative. The GN effect was significantly stronger. In addition the direct effect coefficient for MAT/Suc was higher than the total effect coefficient. It indicates that the impact of MAT/Suc was suppressed by the impact of GN and VN.

In the case of both PA and NA after controlling for GN and VN all direct effects became insignificant (full mediation) mainly due to the indirect effect of VN. The indirect effect of GN was significant, but weaker than the effect of VN only in the case of MAT/Suc and NA.

2.2.3.3 Summary of the Results

The simple associations between MAT, GN, VN and SWB were more or less as expected (see Sects. 1.2 and 1.3 of this article), although the associations between materialism and its domains and affective aspects of SWB were weaker than in other studies. The MAT/Cent correlated significantly neither with GN and VN nor with SWB. The group comparison showed that SWB in materialistic groups differentiated by the level of narcissism was similar. The best combination for high SWL and PA was low MAT accompanied by high GN, the worst—high MAT associated with low GN. Generally GN elevated SWB despite MAT, except for NA, which paradoxically was the highest among materialists with a high level of GN.

The results of the mediation analyses indicate that mainly VN mediated significantly the relationship between all aspects of materialism and SWB. The indirect effect of GN appeared only incidentally. VN and all aspects of materialism were detrimental to SWB, acting synergistically. In the case of GN, MAT and MAT/Suc lowered SWL and elevated NA, whereas GN—acting antagonistically—pushed SWL up and lowered NA. GN and VN slightly suppressed the effect of MAT/Suc on SWL.

2.3 Study III

2.3.1 participants.

The participants were 360 adults (67.5% women), aged 18–76 (M = 35.68; SD = 14.94) from Upper Silesia in Poland. The participants were educated mainly on the secondary (52.5%) and higher (44.4%) level. They were asked to assess their financial situation on a 5-point scale from 1—very poor (not enough to satisfy basic needs) to 5—very good (able to afford a comfortable life). The average score was 3.45 (SD = 0.66) with 54.4% claiming that their material standard of living is mediocre (they have enough to fulfill their needs, but they have to save to cover bigger expenses), and 36.1% claiming that their standard of living is good (they are able to cover most expenses without saving).

The participants were recruited via cooperating students using their social network. Once recruited the participants distributed the set of questionnaires further. No incentives were given for participation.

2.3.2 Measures

Materialism As in in the study I and II the Polish version of the 9-item Material Values Scale was used to measure materialism.

Neuroticism Neuroticism was assessed using the appropriate scale from the Polish version of NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI; Costa and McCrae 1992 ; Zawadzki et al. 1998 ). The NEO-FFI provides a measure of the five basic personality factors, with 12 items for each factor. Each of the items was assessed on a Likert-based scale ranging from 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). The total score was computed as a sum of the 12 items.

Narcissism As in study II the Polish version of the NPI was used to assess grandiose narcissism and the Polish version of HSNS to assess vulnerable narcissism.

Well - being Two aspects of well-being were assessed—general well-being with MHC-SH as in Study I and Satisfaction with Life with the Polish version of SWLS as in Study II.

2.3.3 Results

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations between variables are displayed in Table 5 .

2.3.3.1 Well-Being in Groups Differentiated by Materialism, Neuroticism and Narcissism

As in Study I and II the participants were divided into subgroups according to materialism and either neuroticism or grandiose narcissism scores. The mean scores of well-being (SWL and GWB) were compared in those subgroups in one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey’s test. The tests revealed statistically significant differences between the subgroups in relation to both measures of well-being (see Table 2 ). The Mice and Peacocks when distinguished on the base of NE level differed significantly with respect to both SWL and GWB; the Mice displayed diminished well-being, but not different from the non-materialistic subgroup with high NE, whereas the Peacock who displayed elevated well-being did not differ from non-materialists with low NE. A similar pattern was observed in the case of the Mice and Peacocks when distinguished on the base of GN—the Mice had the lowest SWL and GWB in the sample (in the case of GWB not different from non-materialistic group with low GN), whereas the Peacocks had significantly higher SWL and GWB.

2.3.3.2 The Mediating Effect of Neuroticism and Narcissism on the Relationship of Materialism with Life Satisfaction and Well-Being

Mediation analyses were conducted in order to reveal relationships between predictors of SWL and GWB. As in the previous studies the PROCESS macro model 4 (Hayes 2013 ) was utilized to test for parallel multiple mediator models. As before the bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals (CI) for indirect effects were estimated in 5000 bootstrap resamples. Neuroticism and both types of narcissism were assumed to be parallel mediators for the relationships between MAT/Hap and MAT/Suc and SWL as well as for the relationships between MAT/Hap and GWB. The results are presented in the bottom part of Table 3 . As in previous studies, all total effects of materialism dimensions on both SWL and GWB were initially significant. After controlling for all three mediators—NE, GN and VN—the coefficients became lower or not significant. The indirect effects of NE and GN were significant and contrary to each other—NE lowered SWL and GWB, whereas GN elevated them. In all cases NE was the stronger mediator than GN. The effect of VN was not significant. In the case of MAT/Hap and SWL the mediation was partial. In the case of MAT/Suc NE and GN fully mediated its relationship with SWL. The same was true for MAT/Hap and GWB.

2.3.3.3 Summary of the Results

The simple associations between variables were as expected. MAT/Hap was negatively associated with both measures of well-being, MAT/Suc correlated significantly only with SWL. MAT/Cent did not correlate with well-being measures. Materialism in all its aspects was positively associated with NE and both GN and VN, which in turn correlated with SWB—NE and VN negatively, GN positively. There was also an association between NE and VN (positive) and NE and GN (negative). The Mice differed significantly from the Peacocks in relation to both SWL and GWB.

The mediation analyses showed that NE and GN were competing mediators in the relationship between materialism and well-being. The effect of MAT/Suc was fully mediated by NE and GN, whereas MAT/Hap remained its unique impact on SWL after controlling for all three personality features.

3 Discussion

The results of the three reported studies generally confirmed the initial hypotheses. The domains of materialism differed with regard to their connections with well-being. Of the three the possession-defined happiness was the strongest predictor of all aspects of well-being, followed by the possession-defined success, which predicted mainly life satisfaction and negative affect. The centrality dimension was not associated with any of the examined aspects of well-being. These results are consistent with the previous findings reported by Ahuvia and Wong ( 1995 , 2002 ), Swinyard et al. ( 2001 ), Roberts and Clement ( 2007 ), Pieters ( 2013 ) and Segev et al. ( 2015 ). They are also in line with Srivastava et al.’s ( 2001 ) claim that motives for having money, not money per se, are important for well-being, and the findings of Garðarsdóttir et al. ( 2009 ) demonstrating that the belief that money and material possessions are essential in the quest for a happier self is a strong negative predictor of well-being. Though Garðarsdóttir et al. ( 2009 ) showed also that the desire for money and material goods to indicate personal success was a positive predictor of well-being.; the findings from the current studies are not consistent with this result—they showed that possession-defined success was a negative predictor of well-being.

The results obtained also confirmed the previous findings showing that materialism is connected with neuroticism and both types of narcissism—grandiose and vulnerable. Both types of narcissism correlated positively with materialism, but only grandiose narcissism was associated positively with well-being as revealed before (e.g. Miller and Campbell 2008 ; Sedikides et al. 2004 ; Rose 2002 ). Vulnerable narcissism generally had a destructive impact on various aspects of well-being, similar to the effect of neuroticism. This similarity is not surprising, because the two are correlated (r = .49; see also Wink 1991 ; Rose 2002 ) and there are overlapping features of both traits, such as anxiety, insecurity, inferiority, inadequacy, defensiveness, and negative affect (Miller et al. 2011 ; Rose 2002 ).

However the results obtained in the current research go far beyond these simple associations reported in previous studies. The novelty of this research resides in examining relations between all three phenomena. This issue was approached from two angles. First, the well-being of the two types of materialists identified previously by Górnik-Durose and Pilch ( 2016 )—the Mice and Peacocks—was compared. The Mice and Peacocks, when distinguished on the basis of neuroticism, differed significantly with regard to general well-being. As expected, the Peacocks (with the low neuroticism level) experienced a higher level of well-being than the Mice (with the high neuroticism level). The same was true when the Mice and Peacocks were differentiated by the level of grandiose narcissism. The Peacocks (with high grandiose narcissism) displayed higher well-being than the Mice (with low grandiose narcissism), but the differences were statistically significant only in one study.

The second approach involved testing for mediating effects of personality traits on the relationship between materialism and well-being. All the personality traits (i.e. neuroticism and grandiose and vulnerable narcissism) mediated the relationship between materialism and its two domains (i.e. the possession-defined happiness and the possession-defined success) and various aspects of well-being. The strongest mediator was neuroticism, which eliminated vulnerable narcissism from the equation, when they both were entered into the mediation model. Neuroticism and grandiose narcissism acted against each other, the former lowered life satisfaction and well-being, whereas the latter elevated them.

The current research revealed clearly that materialistic well-being is affected by personality-driven needs and goals. The reason for this might be—as suggested in the introductory section of this article—that materialism is merely a functional strategy applied in an attempt to solve various problems encountered by people with different personality traits.

Individuals with a high level of neuroticism (hyper-reactive, anxious, fearful and tense, with negative expectations, perceiving what happens to them in negative terms) have problems with finding effective ways of coping or they use them unsuccessfully (cf. Suls and Martin 2005 ). The concentration on material possessions as a source of comfort and security and the belief that this is the way to achieve happiness is an example of such an ineffective strategy. Unfortunately such a strategy is easily adopted, because the promise of finding happiness and comfort in material assets is wide-spread in the contemporary consumer culture and supported by its norms and standards (Kasser et al. 2003 ; Dittmar 2008 ).

Materialism as a misleading tactic of coping with fears, insecurity and self-doubt was described by Donnelly et al. ( 2016 ). The authors presented a theoretical model of materialism as a consumption-based strategy for escaping aversive self-awareness. The model assumes that materialists tend to fall short of standards, and they blame themselves for the shortfalls. These self-attributions of responsibility for failure create a focus on self which is aversive and induces distress and negative emotions resulting in cognitive deconstruction. Finally the cognitive deconstruction leads to impulsive and disinhibited behavior, e.g. excessive shopping and spending, which in turn lead to many psychological problems, including diminished well-being.

The core elements of this model, i.e. falling short of one’s own standards, self-blame, feeling of inadequacy, low self-esteem, maladaptive self-awareness and being prone to negative emotions, refer to core problems experienced by individuals with high level of neuroticism (cf. Suls and Martin 2005 ). Thus, it would be argued that the model refers mainly to one type of materialists, i.e. the Mice, and depicts how neuroticism incorporated in materialism impairs the ability to experience happiness and life satisfaction.

However, Donnelly et al. ( 2016 ) also describe materialists as people aiming at self-aggrandizement, highly concerned with their public image and viewing consumption as strategic image management, thus buying goods that are highly visible to others and symbolize high status. This brings to mind the narcissistic consumption pattern (Sedikides et al. 2007 ; Lee et al. 2013 ; Górnik-Durose and Pilch 2016 ). Campbell and Foster ( 2007 ) suggest that materialism is inherent in narcissism as one of the self–regulatory strategies to enhance self-worth. At the same time narcissists are not prone to self-blame, feeling of inadequacy, low self-esteem, and consequently aversive self-awareness, even if we accept that high self-esteem, demonstrated by narcissists, may be—as traditionally viewed—a “false mask” hiding their fragile self (e.g., Morf and Rhodewalt 2001 ). As chronic self-enhancers, narcissists need material goods more for self-promotion than self-protection (cf. Campbell and Foster 2007 ). This is a different strategy, used by the second type of materialists—the Peacocks.

The Peacocks’ materialism fits better into a different model, which was proposed by Shrum et al. ( 2013 ). The authors present materialism through its functions in the construction and maintenance of the individual identity. According to this model, materialism is a means for meeting or bolstering particular self-related needs, such as self-esteem, distinctiveness and efficacy. In addition—as the authors suggest—materialism understood in terms of an identity pursuit may result in a more positive self-view and even increase happiness and well-being. Therefore the self-oriented narcissistic materialists promoting themselves through the acquisition and possession of material goods have a chance to achieve a satisfactory level of well-being. Their strategy may be effective, because the “language” of material goods as convenient and easily accessible is socially approved and understandable within the consumer culture (Dittmar 2008 ).

Consequently, materialism in connection with neuroticism and narcissism seems to fulfill different functions. In the first case, materialism is a strategy aiming at protection, defense, safety and comfort. In the second it is a strategy aiming at promotion, assertion, self-presentation and self-affirmation. The first type of materialism is defensive and withdrawn, the second—offensive and ostentatious. The first is not successful, thus leads to disappointment and low well-being. The second uses appropriate—from the cultural point of view—means, thus may bring positive outcomes, also in relation to well-being.

4 Limitations of the Current Research and Directions for the Future Investigations

The results of the three studies are quite conclusive—personality does matter in the relationship between materialism and well-being. However the current studies have some limitations that should be overcome in future research. For instance, in the present studies only one approach to materialism was applied, according to which materialism is a value influencing the way people behave and make decisions (Richins and Dawson 1992 ; Richins 2004 ). Future research should consider other conceptualizations of this phenomenon. Would the concentration on extrinsic goals as a sign of materialism (cf. Kasser 2002 ) in connection with neuroticism and narcissism have similar effects on well-being? Other researchers also pointed out other mechanisms responsible for diminished well-being among materialists, such as a conflict between values, poor social relationships, perception of the fulfillment of material goals and need satisfaction (see Sect. 1.1 of this article). How strong would the mediating effects of narcissism and neuroticism remain alongside these factors?

There are also some methodological issues of the present studies. First of all the data were obtained via self-report. Personality constructs, values and attitudes are commonly measured in this way, thus the assumption was made that the respondents’ self-reports are an adequate indicator of their internal states and that the respondents are able to report them accurately. However usually self-report measures are overburdened with common method biases. In the present studies some design techniques, suggested by Podsakoff et al. ( 2003 ) were applied to minimize them. For instance, to reduce the potential for social desirability bias the procedure allowed the protection of respondents’ anonymity, to decrease evaluation apprehension the participants were reminded that there are no wrong answers, to reduce statement ambiguity well-established and valid measures were utilized. Also the unwanted measurement context effects, which would produce artefactual covariation, were minimalized by placing the statements relating to dependent, independent and mediating variables in a proper order. Nonetheless all these techniques can only minimalize, but not eliminate, the limitations of the self-report studies. Thus, experimental or longitudinal designs are needed to verify the preliminary findings presented in this article.

The next limitation of the present studies is connected with the nature of the research samples. All three studies were based on convenience samples (relatively small in the case of Study II), drawn from one metropolitan area (Upper Silesia in Poland). The participants were predominantly female, well-educated and relatively wealthy members of the middle-class (with the exception of students in Study I who reported having rather low financial resources). This raises the issue of generalizability. The future research should be conducted in larger, demographically varied, preferably representative, samples. Also the moderating role of the material standard of living of the participants, should be examined more closely, taking into consideration that results of previous research indicated that a poor standard of living has been connected with a higher level of materialism (cf. Ahuvia and Wong 2002 ; Kasser 2002 ) and neurotic materialists reported having a worse material situation than narcissistic materialists (Górnik-Durose and Pilch 2016 ). The cross-cultural approach would be also beneficial to verify the universality of the associations between personality, materialism and well-being.

Ahuvia, A., & Wong, N. Y. (1995). Materialism: Origins and implications for personal well-being. European Advances in Consumer Research, 2, 172–178.

Google Scholar

Ahuvia, A., & Wong, N. Y. (2002). Personality and values based materialism: Their relationship and origins. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 12 (4), 389–402.

Anglim, J., & Grant, S. (2016). Predicting psychological and subjective well-being from personality: Incremental prediction from 30 facets over the Big 5. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17, 59–80.

Ashton, M. C., & Lee, K. (2008). The prediction of honesty–humility-related criteria by the HEXACO and five-factor models of personality. Journal of Research in Personality, 42, 1216–1228.

Bazińska, R., & Drat-Ruszczak, K. (2000). Struktura narcyzmu w polskiej adaptacji kwestionariusza NPI Raskina i Halla. Czasopismo Psychologiczne, 6, 171–188.

Belk, R. W. (1985). Materialism: Trait aspects of living in the material world. Journal of Consumer Research, 12, 265–280.

Bergman, J. Z., Westerman, J. W., Bergman, S. M., & Daly, J. P. (2013). Narcissism, materialism, and environmental ethics in business students. Journal of Management Education, 38, 489–510.

Brzozowski, P. (2010). Skala uczuć pozytywnych i negatywnych (SUPIN): Polska adaptacja skali PANAS Dawida Watsona i Lee Anny Clark . Warszawa: Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych PTP.

Burroughs, J. E., & Rindfleisch, A. (2002). Materialism and well-being: A conflicting values perspective. Journal of Consumer Research, 29, 348–370.

Campbell, W. K., & Foster, J. D. (2007). The narcissistic self: Background, an extended agency model, and ongoing controversies. In C. Sedikides & S. Spencer (Eds.), Frontiers in social psychology: The self (pp. 115–138). Philadelphia, PA: Psychology Press.

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. (1992). Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five Factor Model (NEO-FFI). Professional manual . Odesa, FL: Psychological Assessment Center.

Czarna, A. Z., Dufner, M., & Clifton, A. D. (2014). The effects of vulnerable and grandiose narcissism on liking-based and disliking-based centrality in social networks. Journal of Research in Personality, 50, 42–45.

DeNeve, K. M., & Cooper, H. (1998). The happy personality: A meta-analysis of 137 personality traits and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 124, 197–229.

Diener, E. D., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75.

Dittmar, H. (2008). Understanding the impact of consumer culture. In H. Dittmar, E. Halliwell, R. Banerjee, R. Gardarsdóttir, & J. Janković (Eds.), Consumer culture, identity and well-being. The search for the ‘good life’ and the ‘body perfect’ (pp. 1–24). New York: Psychology Press.

Dittmar, H., Bond, R., Hurst, M., & Kasser, T. (2014). The relationship between materialism and personal well–being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107 (5), 879–924.

Donnelly, G. E., Ksendzova, M., Howell, R. T., Vohs, K. D., & Baumeister, R. F. (2016). Buying to blunt negative feelings: Materialistic escape from the self. Review of General Psychology, 20 (3), 272–316.

Garðarsdóttir, R. B., Dittmar, H., & Aspinall, C. (2009). It’s not the money, it’s the quest for a happier self: The role of happiness and success motives in the link between financial goals and subjective well-being. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 28, 1100–1127.

Górnik-Durose, M. (2016). Polska adaptacja skali wartości materialnych (MVS)—właściwości psychometryczne wersji pełnej i wersji skróconych. Psychologia Ekonomiczna, 9, 5–21.

Górnik-Durose, M. E., & Boroń, K. (2018). Not materialistic, just neurotic. The mediating effect of neuroticism on the relationship between attitudes to material assets and well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 123, 27–33.

Górnik-Durose, M. E., & Pilch, I. (2016). The dual nature of materialism. How personality shapes materialistic value orientation. Journal of Economic Psychology, 57, 102–116.

Haslam, N., Whelan, J., & Bastian, B. (2009). Big Five traits mediate associations between values and subjective well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 46, 40–42.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. A regression-based approach . New York: The Guilford Press.

Hendin, H. M., & Cheek, J. M. (1997). Assessing hypersensitive narcissism: A reexamination of Murray’s Narcissism Scale. Journal of Research in Personality, 31, 588–599.

Hong, R. Y., Koh, S., & Paunonen, S. V. (2012). Supernumerary personality traits beyond the Big Five: Predicting materialism and unethical behavior. Personality and Individual Differences, 53, 710–715.

Houlcroft, L., Bore, M., & Munro, D. (2012). Three faces of narcissism. Personality and Individual Differences, 53, 274–278.

Jaworska, A. (2012). Kwestionariusze Osobowości Eysencka. EPQ-R, EPQ-R w wersji skróconej. Polskie normalizacje . Warszawa: PTP.

Juczyński, Z. (2001). Narzędzia pomiaru w promocji i psychologii zdrowia . Warszawa: Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych PTP.

Karaś, D., Cieciuch, J., & Keyes, C. L. M. (2014). The polish adaptation of the mental health continuum-short form (MHC-SF). Personality and Individual Differences, 69, 104–109.

Kasser, T. (2002). The high price of materialism . Cambridge: MIT Press.

Kasser, T., Ryan, R. M., Couchman, C. E., & Sheldon, K. M. (2003). Materialistic values: Their causes and consequences. In T. Kasser & A. D. Kanner (Eds.), Psychology and consumer culture. The struggle for a good life in a materialistic world (pp. 11–28). Washington, DC: APA.

Keyes, C. L. M. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Research, 43 , 207–222.

Lee, S. Y., Gregg, A. P., & Park, S. H. (2013). The person in the purchase: Narcissistic consumers prefer products that positively distinguish them. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105, 335–352.

Miller, J. D., & Campbell, W. K. (2008). Comparing clinical and social-personality conceptualizations of narcissism. Journal of Personality, 76, 449–476.

Miller, J., Hoffman, B., Gaughan, E., Gentile, B., Maples, J., & Campbell, W. (2011). Grandiose and vulnerable narcissism: A nomological network analysis. Journal of Personality, 79, 1012–1042.

Morf, C. C., & Rhodewalt, F. (2001). Unraveling the paradoxes of narcissism: A dynamic selfregulatory processing model. Psychological Inquiry, 12, 177–196.

Otero-López, J. M., & Villardefrancos, E. (2013). Five-factor model personality traits, materialism, and excessive buying: A mediational analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 54, 767–772.

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (1993). The affective and cognitive context of self-reported measures of subjective well-being. Social Indicators Research, 28, 1–20.

Pieters, R. (2013). Bidirectional dynamics of materialism and loneliness: Not just a vicious cycle. Journal of Consumer Research, 40 (4), 615–631.

Pilch, I., & Górnik-Durose, M. E. (2016). Do we need “dark” traits to explain materialism? The incremental validity of the Dark Triad over the HEXACO domains in predicting materialistic orientation. Personality and Individual Differences, 102, 102–106.

Pilch, I., & Górnik-Durose, M. E. (2017). Grandiose and vulnerable narcissism, materialism, money attitudes, and consumption preferences. The Journal of Psychology, Interdisciplinary and Applied, 151, 185–206.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879–903.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40 (3), 879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/brm.40.3.879 .

Article Google Scholar

Raskin, R. N., & Hall, C. S. (1979). A narcissistic personality inventory. Psychological Reports, 45, 590.

Richins, M. (2004). The material values scale: Measurement properties and development of a short form. Journal of Consumer Research, 31 (1), 209–219.

Richins, M. (2017). Materialism pathways: The process that create and perpetuate materialism. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 27, 480–499.

Richins, M., & Dawson, S. (1992). A consumer values orientation for materialism and its measurement: Scale development and validation. Journal of Consumer Research, 19, 303–316.

Roberts, J. A., & Clement, A. (2007). Materialism and satisfaction with over-all quality of life and eight life domains. Social Indicators Research, 82 (1), 79–92.

Rose, P. (2002). The happy and unhappy faces of narcissism. Personality and Individual Differences, 33, 379–391.

Rose, P. (2007). Mediators of the association between narcissism and compulsive buying: The roles of materialism and impulse control. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 21, 576–581.

Sedikides, C., Gregg, A. P., Cisek, S., & Hart, C. M. (2007). The I that buys: Narcissists as consumers. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 17, 254–257.

Sedikides, C., Rudich, E. A., Gregg, A. P., Kumashiro, M., & Rusbult, C. (2004). Are normal narcissists psychologically healthy? Self-esteem matters. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87, 400–416.

Segev, S., Gavish, A., & Gavish, Y. (2015). A closer look into the materialism construct: The antecedents and consequences of materialism and its three facets. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 32, 85–98.

Shrum, L. J., Wong, N., Arif, F., Chugani, S. K., Gunz, A., Lowrey, T. M., et al. (2013). Reconceptualizing materialism as identity goal pursuits: Functions, processes, and consequences. Journal of Business Research, 66 (8), 1179–1185.

Solberg, E. G., Diener, E., & Robinson, M. D. (2003). Why are materialists less satisfied? In T. Kasser & A. D. Kanner (Eds.), Psychology and consumer culture. The struggle for a good life in a materialistic world (pp. 29–48). Washington, DC: APA.

Srivastava, A., Locke, E. A., & Bartol, K. M. (2001). Money and subjective well-being: It’s not the money, it’s the motives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 959–971.

Steel, P., Schmidt, J., & Shultz, J. (2008). Refining the relationship between personality and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 138–161.

Suls, J., & Martin, R. (2005). The daily life of the garden-variety neurotic: Reactivity, stressor exposure, mood spillover, and maladaptive coping. Journal of Personality, 73, 1–25.

Swinyard, W. R., Kau, A. K., & Phua, H. Y. (2001). Happiness, materialism, and religious experience in the US and Singapore. Journal of Happiness Studies, 2, 13–32.

Watson, J. M. (2012). Educating the disagreeable extravert: Narcissism, the big five personality traits, and achievement goal orientation. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 24 (1), 76–88.

Watson, D. C. (2015). Materialism and the five-factor model of personality: A facet-level analysis. North American Journal of Psychology, 17, 133–150.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 54 , 1063–1070.

Wink, P. (1991). Two faces of narcissism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 590–597.

Zawadzki, B., Strelau, J., Szczepaniak, P., & Śliwińska, M. (1998). Inwentarz osobowości NEO-FFI Costy i McCrae (Adaptacja polska—podręcznik) . Warszawa: Pracownia Testów PTP.

Zuckerman, M., & O’Loughlin, R. E. (2009). Narcissism and well-being: A longitudinal perspective. European Journal of Social Psychology, 39, 957–972.

Download references

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my colleagues and students for their help in collecting data, especially Teresa Sikora, Agnieszka Pasztak-Opiłka, Ewa Wojtyna and Mikołaj Haczek from the Institute of Psychology, University of Silesia in Katowice, and Steve Durose for compiling the database for my research.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of Psychology, University of Silesia in Katowice, Grażyńskiego 53, 40-126, Katowice, Poland

Małgorzata E. Górnik-Durose

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Małgorzata E. Górnik-Durose .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

OpenAccess This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Górnik-Durose, M.E. Materialism and Well-Being Revisited: The Impact of Personality. J Happiness Stud 21 , 305–326 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00089-8

Download citation

Published : 12 February 2019

Issue Date : January 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00089-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Materialism

- Personality

- Neuroticism

- Grandiose narcissism

- Vulnerable narcissism

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

87 Materialism Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

🏆 best materialism topic ideas & essay examples, 📝 simple & easy materialism essay titles, 👍 good essay topics on materialism, ❓ questions about materialism.

- “On Functionalism and Materialism” by Paul Churchland That being the case, the concept mainly focuses on the relationships between outputs and the targeted inputs. This knowledge explains why the two aspects of materialism will make it easier for individuals to redefine their […]

- Berkeley’s Argument on Materialism Analysis The arguments were mainly based on the idea that the perception for an object was in the perceiver and not the object.

- Marvin Harris’ Cultural Materialism Concept The connotation of Jesus as the king and messiah of the Jews did not mean that he was to overthrow the Roman Empire ruling at that time to establish his kingdom in Jerusalem.

- Materialism Concept and Theorists Views The administrations of the government of the United States and the People’s Republic of China are examples of differing views on materialism.

- Aspects of Materialism and Energy Consumption In my opinion, this led to the formation of the materialism phenomenon and enforced a particular way of thinking centered on meeting one’s demands.”Different economies worldwide use fossil fuels, such as coal, oil, and natural […]

- Materialism: Rorty’s Response to the Antipodean Story This paper examines Rorty’s argument that in accepting the material reality of the universe, we can also accept that the physical universe shapes our beliefs and interpretations, and that our understanding of the universe is […]