- 3 . 01 . 20

- Leaving Academia

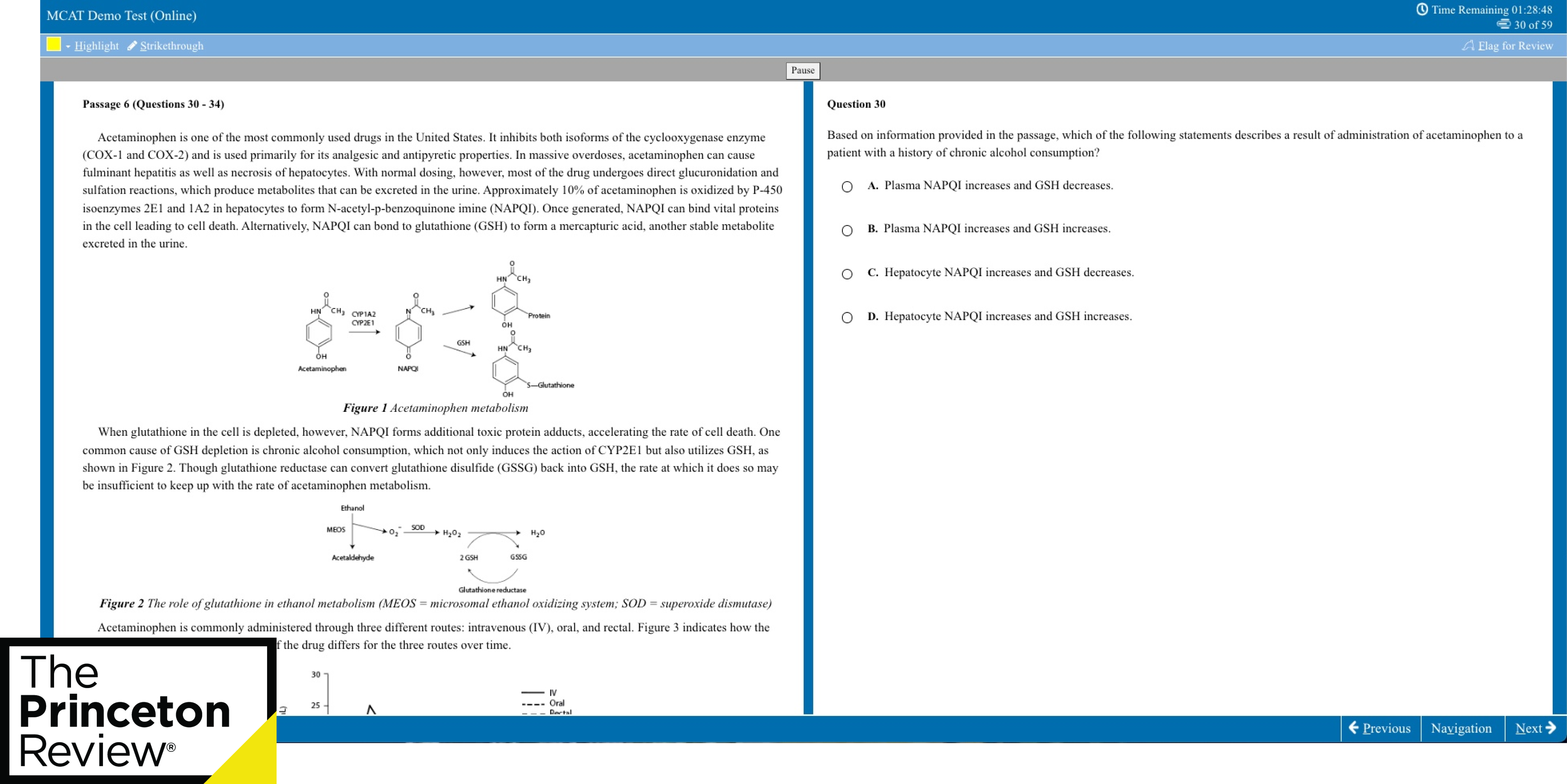

Is a PhD Worth It? I Wish I’d Asked These 6 Questions First.

- Posted by: Chris

Updated Nov. 19, 2022

Is a PhD worth it?

Should I get a PhD?

A few people admit to regretting their PhD. Most—myself included — said that they don’t ( I wrote about why in this post ).

But we often say we don’t regret stupid things we’ve done or bad things that happen to us. This means we learned from them, not that we wanted them to happen.

So just because PhDs don’t regret it, doesn’t mean it was worth it.

But if you were to ask, Is a PhD worth it, it’s a different and more complicated question.

When potential PhD students ask me for advice, I hate giving it. I can’t possibly say whether it will be worth it for them. I only know from experience that for some PhDs the answer is no.

In this post, I’ll look at this question from five different directions, five different ways that a PhD could be worth it. Then I give my opinion on each one. You can tell me if I got the right ones of if I’m way off base. So here we go.

This is post contains affiliate links. Thanks for supporting Roostervane!

tl;dr It’s up to you to make it worth it. A PhD can hurt your finances, sink you in debt, and leave you with no clear path to success in some fields. But PhDs statistically earn more than their and have lower unemployment rates. A PhD also gives you a world-class mind, a global network, and a skill set that can go just about anywhere.

Should I Get a PhD?

tl;dr Don’t get a PhD by default. Think it through. Be clear about whether it’s going to help you reach career goals, and don’t expect to be a professor. A few rules of thumb- make sure you know where you want to go and whether a PhD is the ONLY way to get there, make sure it’s FUNDED (trust me), and make sure your program has strong ties into industry and a record of helping its students get there.

1. Is a PhD worth it for your finances?

My guess: Not usually

People waste a lot of their best years living on a grad stipend. To be honest, my money situation was pretty good in grad school. I won a large national grant, I got a ton of extra money in travel grants, and my Canadian province gave me grants for students with dependents. But even with a decent income, I was still in financial limbo–not really building wealth of any sort.

And many students scrape by on very small stipends while they study.

When it comes to entering the marketplace, research from Canada and the United States shows that PhD students eventually out-earn their counterparts with Master’s degrees. It takes PhDs a few years to find their stride, but most of us eventually do fine for earnings if we leave academia. Which is great, and perhaps surprising to many PhDs who think that a barista counter is the only non-academic future they have .

The challenge is not income–it’s time. If you as a PhD grad make marginally more than a Master’s graduate, but they entered the workforce a decade earlier, it takes a long time for even an extra $10,000 a year to catch up. The Master’s grad has had the time to build their net worth and network, perhaps buy a house, pay down debt, invest, and just generally get financially healthy.

While PhDs do fine in earnings in the long run, the opportunity cost of getting the PhD is significant.

The only real way to remedy this—if you’ve done a PhD and accumulating wealth is important to you, is to strategically maximize your earnings and your value in the marketplace to close the wealth gap. This takes education, self-discipline, and creativity, but it is possible.

I tried to calculate the opportunity cost of prolonging entry into the workforce in this post .

2. Is a PhD worth it for your career?

My guess: Impossible to tell

Most of my jobs have given me the perfect opportunity to see exactly where I could be if I’d stopped at a Master’s degree, often working alongside or for those who did and are further ahead. In terms of nuts and bolts of building career experience section on a resume, which is often the most important part, a PhD is rarely worth it. (Some STEM careers do require a PhD.)

However, at the start of my post-graduate educational journey, I was working part-time running teen programs and full time as a landscaper. I had an undergraduate degree. Despite my job and a half, I was still poor. My life had no direction, and had I not begun my Master’s to PhD journey I probably would have stayed there.

The PhD transformed me personally. It did this by developing my skills, or course. But even more so, it taught me that anything is possible. It took a poor kid from a mining town in northern Canada and gave me access to the world. It made my dreams of living abroad come true. I learned that anything is possible. And that will never go away.

It’s changed the course of my life and, subsequently, my career.

It’s impossible for you to know if it’s worth it for your career. But you can build a hell of a career with it.

So it wouldn’t be fair for me to say, “don’t get a PhD.” Because it worked out for me, and for some it does.

But there are a heck of a lot of people who haven’t figured out how to build a career with this thing. Which is one of the reasons Roostervane exists in the first place.

Psst! If you’re looking at doing a PhD because you don’t know where to go next with your career–I see you. Been there. Check out my free PDF guide– How to Build a Great Career with Any Degree.

3. Is a PhD worth it for your personal brand?

My guess: Probably

There’s some debate over whether to put a Dr. or PhD before or after your name. People argue over whether it helps in the non-academic marketplace. Some feel that it just doesn’t translate to whatever their new reality is. Some have been told by some manager somewhere that they’re overqualified and pulled themselves back, sometimes wiping the PhD off their resume altogether.

The truth is, if you have a PhD, the world often won’t know what to do with it. And that’s okay. Well-meaning people won’t understand how you fit into the landscape, and you may have to fight tooth and nail for your place in it. People may tell you they can’t use you, or they might go with what they know—which is someone less qualified and less-educated.

It happens.

But someone with a PhD at the end of their name represents an indomitable leader. So grow your possibilities bigger and keep fighting. And make your personal brand match those three little letters after your name. Do this so that the world around can’t help but see you as a leader. More importantly, do it so that you don’t forget you are.

Should I put “PhD” after my name on LinkedIn?

5 reasons you need to brand yourself

4. Is a PhD worth it for your sense of purpose?

Is getting a PhD worth it? For many people the answer is no.

PhDs are hurting.

If you’ve done one, you know. Remember the sense of meaning and purpose that drew you towards a PhD program? Was it still there at the end? If yours was, you’re lucky. I directed my purpose into getting hired in a tenure-track job, and got very hurt when it didn’t happen.

And people have vastly different experiences within programs.

Some people go through crap. But for them their research is everything and putting up with crap is worth it to feel like they have a sense of purpose. Many PhDs who are drawn into programs chasing a sense of purpose leave deeply wounded and disenchanted, ironically having less purpose when they started.

While new PhDs often talk about the PhD as a path do doing “something meaningful,” those of us who have been through entire programs have often seen too much. We’ve either seen or experienced tremendous loss of self. Some have friends who didn’t make it out the other end of the PhD program.

But there are some PhDs who have a great experience in their programs and feel tremendously fulfilled.

As I reflect on it, I don’t think a sense of purpose is inherently fulfilled or disappointed by a PhD program. There are too many variables.

However, if you’re counting on a PhD program to give you a sense of purpose, I’d be very careful. I’d be even more cautious if purpose for you means “tenure-track professor.” Think broadly about what success means to you and keep an open mind .

5. Is my discipline in demand?

Okay, so you need to know that different disciplines have different experiences. Silicon Valley has fallen in love with some PhDs, and we’re seeing “PhD required” or “PhD preferred” on more and more job postings. So if your PhD is in certain, in-demand subjects… It can be a good decision.

My humanities PhD, on the other hand, was a mistake. I’m 5 years out now, and I’ve learned how to use it and make money with it. That’s the great news. But I’d never recommend that anyone get a PhD in the humanities. Sorry. I really wish I could. It’s usually a waste of years of your life, and you’ll need to figure out how to get a totally unrelated job after anyway.

TBH, most of the skills I make money with these days I taught myself on Skillshare .

6. Is a PhD worth it for your potential?

My guess: Absolutely

Every human being has unlimited potential, of course. But here’s the thing that really can make your PhD worth it. The PhD can amplify your potential. It gives you a global reach, it gives you a recognizable brand, and it gives you a mind like no other.

One of my heroes is Brené Brown. She’s taken research and transformed the world with it, speaking to everyone from Wall-Street leaders to blue-collar workers about vulnerability, shame, and purpose. She took her PhD and did amazing things with it.

Your potential at the end of your PhD is greater than it has ever been.

The question is, what will you do with that potential?

Many PhD students are held back, not by their potential, but by the fact that they’ve learned to believe that they’re worthless. Your potential is unlimited, but when you are beaten and exhausted, dragging out of a PhD program with barely any self-worth left, it’s very hard to reach your potential. You first need to repair your confidence.

But if you can do that, if you can nurture your confidence and your greatness every day until you begin to believe in yourself again, you can take your potential and do anything you want with it.

So why get a PhD?

Because it symbolizes your limitless potential. If you think strategically about how to put it to work.

PhD Graduates Don’t Need Resumes. They Need a Freaking Vision

By the way… Did you know I wrote a book about building a career with a PhD? You can read the first chapter for free on Amazon.

So if you’re asking me, “should I do a PhD,” I hope this post helps you. Try your best to check your emotion, and weigh the pros and cons.

And at the end of the day, I don’t think that whether a PhD is worth it or not is some fixed-in-stone thing. In fact, it depends on what you do with it.

So why not make it worth it? Work hard on yourself to transform into a leader worthy of the letters after your name, and don’t be afraid to learn how to leverage every asset the PhD gave you.

One of the reasons I took my PhD and launched my own company is that I saw how much more impact I could have and money I could be making as a consultant (perhaps eventually with a few employees). As long as I worked for someone else, I could see that my income would likely be capped. Working for myself was a good way to maximize my output and take control of my income.

It’s up to you to make it worth it. Pick what’s important to you and how the degree helps you get there, and chase it. Keep an open mind about where life will take you, but always be asking yourself how you can make more of it.

Check out the related post- 15 Good, Bad, and Awful Reasons People Go to Grad School. — I Answer the Question, “Should I Go to Grad School?” )

Consulting Secrets 3 – Landing Clients

Photo by Christian Sterk on Unsplash There’s a new type of post buzzing around LinkedIn. I confess, I’ve even made a few. The post is

You’re Not Good Enough… Yet

Last year, I spent $7k on a business coach. She was fantastic. She helped me through sessions of crafting my ideas to become a “thought

$200/hr Expert? Here’s the Secret!

Photo by David Monje on Unsplash I was listening to Tony Robbins this week. He was talking about being the best. Tony asks the audience,

SHARE THIS:

EMAIL UPDATES

Weekly articles, tips, and career advice

Roostervane exists to help you launch a career, find your purpose, and grow your influence

- Write for Us

Terms of Use | Privacy | Affiliate Disclaimer

©2022 All rights reserved

The Savvy Scientist

Experiences of a London PhD student and beyond

Is a PhD Worth It? Should I Do a PhD?

It’s been almost a year since I was officially awarded my PhD. How time flies! I figure now is a good time to reflect on the PhD and answer some of life’s big questions. Is a PhD worth it? Does having a PhD help your future job prospects? Am I pleased that I did a PhD and would I recommend that you do a PhD?

In this post I’ll walk through some of the main points to consider. We’ll touch on some pros and cons, explore the influence it could have on your career and finally attempt to answer the ultimate question. Is a PhD worth it?

Before we get into the details, if you’re considering applying for a PhD you may also want to check out a few other posts I’ve written:

- How Hard is a PhD?

- How Much Work is a PhD?

- How Much Does a PhD Student Earn? Comparing a PhD Stipend to Grad Salaries

- Characteristics of a Researcher

Are you seated comfortably? Great! Then we’ll begin.

The Pros and Cons of PhDs

When I have a difficult decision to make I like to write a pros and cons list. So let’s start by breaking down the good and bad sides of getting a PhD. Although I’ve tried to stay objective, do take into account that I have completed a PhD and enjoyed my project a lot!

These lists certainly aren’t exhaustive, so be sure to let me know if you can think of any other points to add!

The Good Parts: Reasons to Do a PhD

Life as a phd student.

- You get to work on something really interesting . Very few people outside of academia get to dive so deep into topics they enjoy. Plus, by conducting cutting edge research you’re contributing knowledge to a field.

- It can be fun! For example: solving challenges, building things, setting up collaborations and going to conferences.

- Being a PhD student can be a fantastic opportunity for personal growth : from giving presentations and thinking critically through to making the most of being a student such as trying new sports.

- You are getting paid to be a student : I mean come on, that’s pretty good! Flexible hours, socialising and getting paid to learn can all be perks. Do make sure you consciously make the most of it!

Life As A PhD Graduate

- The main one: Having a PhD may open doors . For certain fields, such as academia itself, a PhD may be a necesity. Whilst in others having a PhD can help demonstrate expertise or competency, opening doors or helping you to leapfrog to higher positions. Your mileage may vary!

- You survived a PhD: this accomplishment can be a big confidence booster .

- You’ve got a doctorate and you can use the title Dr. Certainly not enough justification on it’s own to do a PhD, but for some people it helps!

The Bad Parts: Potential Reasons Not to Do a PhD

- It can be tough to complete a PhD! There are lots of challenges . Unless you’re careful and take good care of yourself it can take a mental and physical toll on your well being.

- A PhD can be lonely ( though doesn’t have to be ), and PhD supervisors aren’t always as supportive as you’d like them to be.

- Additionally, in particular now during the pandemic, you might not be able to get as much support from your supervisor, see your peers or even access the equipment and technical support as easily as in normal times.

- You might find that having a PhD may not bring the riches you were expecting . Have a certain career you’re looking to pursue? Consider trying to find out whether or not having a PhD actually helps.

- Getting a job with a PhD can still be tough . Let’s say you want to go for a career where having a PhD is required, even once you’ve got a PhD it might not be easy to find employment. Case in point are academic positions.

- Even though you’ve put in the work you may want to use your Dr title sparingly , it certain industries a PhD may be seen as pretencious. Also, use your title sparingly to avoid getting mistaken for a medic (unless of course you’re one of them too!)

Is a PhD Good For Your Career?

If you’re wondering “Should I do a PhD?”, part of your motivation for considering gaining a PhD may be your career prospects. Therefore I want to now dive deeper into whether or not a PhD could help with future employment.

It is difficult to give definitive answers because whether or not a PhD helps will ultimately depend a lot upon what kind of career you’re hoping to have. Anyway, let’s discuss a few specific questions.

Does a PhD Help You Get a Job?

For certain industries having a PhD may either be a requirement or a strong positive.

Some professions may require a PhD such as academia or research in certain industries like pharma. Others will see your qualification as evidence that you’re competent which could give you an edge. Of course if you’re aiming to go into a career using similar skills to your PhD then you’ll stand a better chance of your future employer appreciating the PhD.

In contrast, for other roles your PhD may not be much help in securing a job. Having a PhD may not be valued and instead your time may be better spent getting experience in a job. Even so, a PhD likely won’t have been completely useless.

When I worked at an engineering consultancy the recruitment team suggested that four years of a PhD would be considered comparable to two or three years of experience in industry. In those instances, the employer may actively prefer candidates who spent those years gaining experience on the job but still appreciates the value of a PhD.

Conclusion: Sometimes a PhD will help you get a job, othertimes it wont. Not all employers may appreciate your PhD though few employers will actively mark you down for having a PhD.

Does a PhD Increase Salary? Will it Allow You to Start at a Higher Level?

This question is very much relates to the previous one so my answer will sound slightly similar.

It’ll ultimately depend upon whether or not the industry and company value the skills or knowledge you’ve gained throughout your PhD.

I want to say from the start that none of us PhD-holders should feel entitled and above certain types of position in every profession just for having a PhD. Not all fields will appreciate your PhD and it may offer no advantage. It is better to realise this now.

Some professions will appreciate that with a PhD you’ll have developed a certain detail-orientated mindset, specialised knowledge or skills that are worth paying more for. Even if the position doesn’t really demand a PhD, it is sometimes the case that having someone with a PhD in that position is a useful badge for the company to wave at customers or competitors. Under these circumstances PhD-holders may by default be offered slightly higher starting positions than other new-starters will lower degree qualifications.

To play devil’s advocate, you could be spending those 3-4 (or more) years progressing in the job. Let’s look at a few concrete examples.

PhD Graduate Salaries in Academia

Let’s cut to the chase: currently as a postdoc at a decent university my salary is £33,787, which isn’t great. With a PhD there is potential to possibly climb the academic ladder but it’s certainly not easy. If I were still working in London I’d be earning more, and if I were speficially still working at Imperial in London I’d be earning a lot more. Browse Imperial’s pay scales here . But how much is it possible to earn with a PhD compared to not having one?

For comparison to research staff with and without PhDs:

As of 2023 research assistants (so a member of staff conducting research but with no PhD) at Imperial earn £38,194 – £ 4 1,388 and postdoctoral research associates earn £43,093 – £50,834 . Not only do you earn £5000 or more a year higher with a PhD, but without a PhD you simply can’t progress up the ladder to research fellow or tenure track positions.

Therefore in academia it pays to have a PhD, not just for the extra cash but for the potential to progress your career.

PhD Graduate Salaries in Industry

For jobs in industry, it is difficult to give a definitive answer since the variety of jobs are so wide ranging.

Certain industries will greatly reward PhD-holders with higher salaries than those without PhDs. Again it ultimately depends on how valuable your skills are. I’ve known PhD holders to do very well going into banking, science consultancy, technology and such forth.

You might not necessarily earn more money with a PhD in industry, but it might open more doors to switch industries or try new things. This doesn’t necessarily mean gaining a higher salary: I have known PhD-holders to go for graduate schemes which are open to grads with bachelors or masters degrees. Perhaps there is an argument that you’re more employable and therefore it encourages you to make more risky career moves which someone with fewer qualifications may make?

You can of course also use your PhD skills to start your own company. Compensation at a start-up varies wildly, especially if you’re a founder so it is hardly worth discussing. One example I can’t resist though is Magic Pony. The company was co-founded by a Imperial PhD graduate who applied expertise from his PhD to another domain. He sold the company two years later to Twitter for $150 million . Yes, including this example is of course taking cherry-picking to the extreme! The point stands though that you can potentially pick up some very lucrative skills during your PhD.

Conclusion: Like the previous question, not all industries will reward your PhD. Depending on what you want to go and do afterward your PhD, it isn’t always worth doing a PhD just for career progression. For professions that don’t specifically value a PhD (which is likely the majority of them!) don’t expect for your PhD to necessarily be your ticket to a higher position in the organisation.

Is a PhD Worth it?

What is “it”.

When we’re asking the question “is a PhD worth it?” it is a good idea to touch on what “it” actually is. What exactly are PhD students sacrificing in gaining a PhD? Here is my take:

- Time . 3-5 (more more) years of your life. For more see my post: how long a PhD takes .

- Energy. There is no doubt that a PhD can be mentally and physically draining, often more so than typical grad jobs. Not many of us PhD students often stick to normal office hours, though I do encourage you to !

- Money. Thankfully most of us, at least in STEM, are on funded PhD projects with tax free stipends. You can also earn some money on the side quite easily and without paying tax for a while. Even so, over the course of a PhD you are realistically likely to earn more in a grad job. For more details on how PhD stipends compare to grad salaries read my full analysis .

- Potential loss of opportunities . If you weren’t doing a PhD, what else could you be doing? As a side note, if you do go on to do a PhD, do make sure you to take advantage of the opportunities as a PhD student !

When a PhD Could Be Worth It

1. passion for a topic and sheer joy of research.

The contribution you make to progressing research is valuable in it’s own right. If you enjoy research, can get funding and are passionate about a subject by all means go and do the PhD and I doubt you’ll regret it.

2. Learning skills

If there is something really specific you want to spend three year or more years learning then a PhD can be a great opportunity. They’re also great for building soft skills such as independence, team work, presenting and making decisions.

Do be aware though that PhD projects can and do evolve so you can’t always guarantee your project will pan out as expected.

If there is the option to go into a career without a PhD I’d bet that in a lot of cases you’d learn more, faster, and with better support in industry. The speed of academic research can be painstakingly slow. There are upsides to learning skills in academia though, such as freedom and the low amount of responsibility for things outside your project and of course if you’re interested in something which hasn’t yet reached industry.

3. Helping with your career

See the section further up the page, this only applies for certain jobs. It is rare though that having a PhD would actively look bad on your CV.

When a PhD May Not Be Worth It

1. just because you can’t find another job.

Doing a PhD simply because you can’t find a job isn’t a great reason for starting one. In these circumstances having a PhD likely isn’t worth it.

2. Badge collecting

Tempted by a PhD simply to have a doctorate, or to out-do someone? Not only may you struggle with motivation but you likely won’t find the experience particularly satisfying. Sure, it can be the icing on the cake but I reckon you could lose interest pretty quickly if it is your only motivation for gaining a PhD.

Do I Feel That My Own PhD Was Worth It?

When I finished my undergrad I’d been tempted by a PhD but I wasn’t exactly sure about it. Largely I was worried about picking the wrong topic.

I spent a bit of time apprehensively applying, never being sure how I’d find the experience. Now that I’ve finished it I’m very pleased to have got my PhD!

Here are my main reasons:

- I enjoyed the research and felt relatively well fulfilled with the outcomes

- Having the opportunity to learn lots of some new things was great, and felt like time well spent

- I made new friends and generally enjoyed my time at the university

- Since I’d been interested in research and doing a PhD for so long, I feel like if I’d not done it I’d be left wondering about it and potentially end up regretting it.

In Summary, Is a PhD Worth It?

I’ve interviewed many PhD students and graduates and asked each one of them whether the PhD was worth it . The resounding answer is yes! Now of course there is some selection bias but even an interviewee who had dropped out of their PhD said that the experience had been valueable.

If you’ve got this far in the post and are still a little on the fence about whether or not a PhD is worth it, my advice is to look at the bigger picture. In comparison to your lifetime as a whole, a PhD doesn’t really take long:

People graduating now likely won’t retire until they’re in their 70s: what is 3-4 years out of a half century long career?

So Should I Do a PhD?

Whether a PhD is worth all the time and energy ultimately comes down to why you’re doing one in the first place.

There are many great reasons for wanting to do a PhD, from the sheer enjoyment of a subject through to wanting to open up new career opportunities.

Nevertheless, it is worth pointing out that practically every PhD student encounters difficult periods. Unsurprisingly, completing a PhD can be challenging and mentally draining. You’ll want to ensure you’re able to remind yourself of all the reasons why it is worth it to provide motivation to continue.

If you’re interested, here were my own reasons for wanting a PhD.

Why I decided to pursue a PhD

Saying that, if you’re interested in doing a PhD I think you should at least apply. I can’t think of any circumstances where having a PhD would be a hindrance.

It can take a while to find the right project (with funding ) so I suggest submitting some applications and see how they go. If you get interesting job offers in the meantime you don’t need to commit to the PhD. Even if you start the PhD and find you don’t enjoy it, there is no shame in leaving and you can often still walk away with a master’s degree.

My advice is that if you’re at all tempted by a PhD: go for it!

I hope this post helped you to understand if a PhD is worth it for you personally. If it is then best of luck with your application!

Considering doing a PhD? I have lots of other posts covering everything about funding , how much PhD students earn , choosing a project and the interview process through to many posts about what the life of a PhD student and graduate is like . Be sure to subscribe below!

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

Related Posts

PhD Salary UK: How Much Do PhD Students Get Paid Compared to Graduates?

5th February 2024 5th February 2024

The Benefits of Having a PhD

7th September 2022 30th January 2024

My top PhD regrets: 10 lessons learned by a PhD grad

21st April 2022 25th September 2023

4 Comments on “Is a PhD Worth It? Should I Do a PhD?”

Hi Thanks for the post . I have been struggling to make a decision regarding doing a PhD or doing a second masters . I’m currently doing an msc civil engineering online (because of covid) so for my research I am not able to conduct lab experiments. Therefore my research is more of a literature review / inductive research. So I feel I’ll be at a disadvantage if I were to apply for a phd program especially at high ranking universities like oxford , imperial etc What are your thoughts?

Hey Esther,

I completely appreciate that it’s not an ideal situation at the moment so thanks for reaching out, it’s a great question. A few thoughts I have:

• If you are already tempted by a PhD and would do a second masters simply to gain lab experience, there is no harm in applying for the PhD now. At the very least I suggest considering reaching out to potential supervisors to discuss the situation with them. The universities realise that current applicants won’t have been able to gain as much research experience as normal over the last year. Practical lab experience has halted for so many people so don’t let it put you off applying!

• If you don’t get in on the first go, I don’t believe it looks bad to apply again with more experience. I applied for PhDs for three years, it doesn’t need to take this long but the point is that there’s not much reason to give it a go this year and stand a chance of getting accepted.

• Although we can be optimistic, even if you were to do a second masters it may not be guaranteed that you can gain as much lab experience as you’d like during it: even more reason to start the ball rolling now.

I hope that helps, let me know if you’d like any other further advice.

Best of luck. 🙂

Funny, every one i have talked to as well as myself when we asked ourselves and others whether the PhD was worth it is a resounding ‘No.’

I guess it comes down to a Blue or Red Pill, LoL.

Hi Joe, thanks for sharing this. I’ve spent enough time on the PhD subreddit to see many other people who haven’t had good experiences either! On the flipside many people do have positive experiences, myself included. There is perhaps an element of luck as to what your research environment turns out to be like which could somewhat dictate the PhD experience, but ultimately I do think that answering whether or not a PhD has been worth it really depends a lot on why someone is pursuing a PhD in the first place. I’m keen to make sure people don’t have unrealistic expectations for what it could bring them. I really welcome hearing about different experiences and if you’d fancy sharing your perspective for the PhD profiles series I’d love to hear from you.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Privacy Overview

Is it a good time to be getting a PhD? We asked those who’ve done it

Researcher, College of Nursing and Health Sciences, Flinders University

Postdoctoral Research Associate, College of Nursing and Health Sciences, Flinders University

Disclosure statement

Career Sessions was sponsored by a grant from Inspiring SA ( https://inspiringsa.org.au/ ).

Flinders University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

The number of Australian PhD graduates reached around 10,000 a year in 2019, twice as many as in 2005. However, the number of PhDs has been exceeding the available academic positions since as early as the mid-1990s. In 2020, universities purged around 10% of their workforce due to the pandemic, and many university careers are still vulnerable .

Given these statistics, you might wonder if doing a PhD is still a good idea. Based on our discussions with PhD holders, there are still plenty of very good reasons, which is good news in 2021.

Read more: 2021 is the year Australia's international student crisis really bites

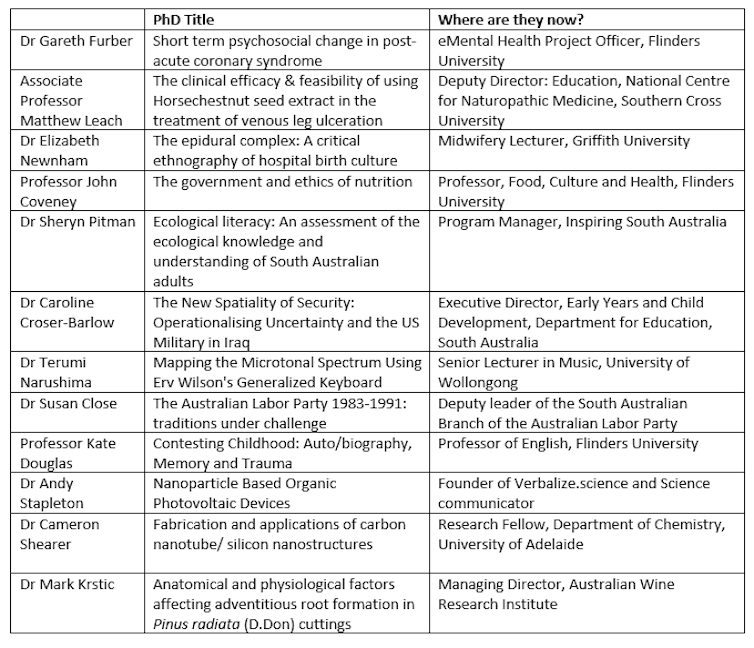

In June 2020 we interviewed 12 PhD holders from multiple disciplines for our podcast Career Sessions to investigate the question: why do a PhD?

Why do a PhD?

The PhD is a mechanism for developing high-level research skills, learning about rigours of science or the development of theory. It sets you up with project management, problem-solving and analytical skills that are meaningful within and beyond academia.

“It just taught me all those transferable skills, project management, and also now starting businesses. I’m amazed at how close starting a business is to doing a science project.” – Dr Andy Stapleton

For our interviewees, the PhD is an opportunity to dive deeply into a topic they are passionate about. They also considered contributing new knowledge to be a privilege. The process taught them to be better thinkers, critical thinkers, and to view the world through new eyes.

“The mental fitness to work at a high level, to be able to think at a high level, to be able to write it […] The topic is less important.” – Dr Gareth Furber

The PhD is a voyage of discovery to a better understanding of how things work. It gives them a credible platform from which their voice can be heard and respected, and they can contribute to change.

“I think it’s definitely like a springboard or something. It launches you into a whole other place and it gives you […] more of a voice. It’s a political act for me. It’s about making change.” – Dr Elizabeth Newnham

The PhD is a tough and sometimes painful journey, but ultimately rewarding. The extraordinary was tempered by frustration, and the experience shaped their lives, increasing self-confidence and leading to new self-awareness.

Read more: PhD completion: an evidence-based guide for students, supervisors and universities

When asked whether they would they do it again, no-one hesitated in saying “yes”.

“You will never stretch your brain in a way that a PhD forces you to.” – Professor Kate Douglas.

The PhD is not necessarily a golden ticket to an academic career, but the experience and skills you develop will be meaningful for your future.

“What I’d done in my PhD gave me a lot broader sense than just my own personal experience. There were a lot of people that have heard me speak and a lot of that’s been informed by the PhD. So it might not be direct, but it’s informed who I am.” – Dr Susan Close

Advice from our guests

Keep both your eyes and your mind open. Pick a topic you are passionate about. Speak to people both within and outside academia to find out where this could lead. Think about whether you actually need a PhD to get to where you want to be.

You’ll have to make some judgement calls about how a PhD can fit into your life.

And find the right supervisor! They are the most important relationship you will have throughout your candidature, and they are a solid reference for what comes next. Finding the right supervisor will always enhance your PhD experience .

Read more: Ten types of PhD supervisor relationships – which is yours?

A PhD isn’t right for everyone. Ask yourself, is it the right time for you and your research interests? Are you resilient? Mental health among PhD students is poor

Our podcast guests have witnessed PhD students’ struggles. The pathway of a PhD candidate is not linear. There are many ups and downs. You will meander in many unplanned directions and often take wrong turns.

When you have completed your PhD, the hard work is really just starting. It is a gateway, but there are a lot of PhDs out there. It is what comes next that really counts.

“It’s a gateway. You’re learning how to do research. But if you really want to be successful afterwards, you need to apply that, and be diligent about that as well, and have a good work ethic.” – Dr Mark Krstic

Read more: 1 in 5 PhD students could drop out. Here are some tips for how to keep going

A PhD in any field is an achievement. Even the most niche topics will contribute knowledge to a field that is important for many people. The reward is intrinsic and only you can identify how doing a PhD will contribute to your life. It gives you a great toolkit to identify the doors that are appropriate for you.

“The first paper was the most exciting thing. […] at that time I thought of papers as like a version of immortality. My name is on something that will last forever. I think this is my legacy.” – Dr Cameron Shearer

- Higher education

- PhD supervisors

- PhD students

- PhD research

- PhD candidates

Research Fellow

Senior Research Fellow - Women's Health Services

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

- Skip to main content

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- Apply Apply

- Follow Us

The Pros and Cons of Getting a PhD

Getting a doctorate is a decision that will impact both your personal and professional life for many years to come. In this blog, we explore the benefits and drawbacks of attaining a doctoral degree, aiming to provide you with an unbiased view to help you make an informed decision.

Why Consider A PhD?

The benefits of a phd.

When it comes to enhancing your knowledge and contributing to your chosen field, few pathways can match the depth of a PhD. The benefits of a PhD extend beyond mere academic gains – they permeate each dimension of your professional enhancement.

1. Mastery in Your Field A PhD equips you with comprehensive knowledge about a specific area, amplifying your analytical, critical thinking and research skills to a level far beyond what a bachelor’s or a master’s degree could offer.

2. Opportunity for Ground-breaking Research As a PhD student, your primary role is to create new knowledge. The sense of fulfillment derived from contributing something novel to your field can be incredibly rewarding.

3. Networking Opportunities During your PhD program, you'll attend conferences and seminars, presenting you with opportunities to mingle with like-minded individuals, renowned academics and industry professionals, expanding your professional network substantially.

4. Enhanced Career Prospects With a PhD, a broader horizon of career opportunities opens up. You become a university professor, a leader in research organizations, or even a policy-maker influencing critical decisions in your field.

Practical Reasons to Get a Doctorate Degree

1. Societal Impact PhD holders can influence policy, promoting changes that positively impact society at various levels.

2. Teaching Opportunities For those passionate about educating others and impacting future generations, a Doctorate degree is often a prerequisite for higher-level academic positions.

3. Potential Higher Earnings A direct benefit of a PhD is the possibility of higher earnings over the course of your career, although this can vary considerably depending on the field.

The Flip Side: Challenges of a PhD

Just like any significant endeavor, getting a doctorate comes with its fair share of challenges.

The Cons of a PhD

1. Time and Financial Commitment A typical PhD can take 4-7 years to complete. Not only does this require a substantial investment of your time, it can also strain your finances. While scholarships and stipends may alleviate some costs, there is the foregone income to consider as well.

2. Pressures and Stress Levels The demands of a PhD — meticulous research, endless writing and frequent presentations — are often high. The intense pressure can lead to stress and burnout.

3. Work-Life Balance The long hours often required to complete a PhD can lead to a blurring of lines between work and personal life.

Practical Disadvantages of a Doctorate Degree

1. Over-Qualification Depending on your field, you might find potential employers outside academia who view you as overqualified, thus narrowing your pool of job opportunities.

2. Limited Practical Experience Dependent largely on theoretical work, a PhD sometimes lags in offering industry-specific training, which some employers may seek.

3. Opportunity Costs You should consider alternative achievements you might forego during the years spent on your PhD. This includes work experience, career progression, or even personal life events.

Making an Informed Decision: PhD or Not?

Deciding whether or not a PhD is worth it for you is a deeply personal decision, highly dependent on your long-term career goals and current life situation.

Evaluate your reasons to get a doctorate degree.

- Are you genuinely passionate about research?

- How essential is a PhD for your career aspirations?

- Are you ready for the financial implications?

Have you considered the opportunity cost?

Seeking advice from PhD holders, mentors, and career advisors can offer valuable insights in answering these questions.

The decision to pursue a PhD is undoubtedly complex and multifaceted. It requires careful consideration of both the benefits of a doctorate degree and its potential disadvantages. Ultimately, though, it is a personal decision. What is very clear is this: when used as a stepping stone for specific career goals, a PhD can be an exceptionally powerful tool.

learn more about what it takes to get a PhD

Explore our guide How to Get a PhD: A Guide to Choosing and Applying to PhD Programs.

Request more

Information.

Complete the form to reach out to us for more information

Published On

More articles, recommended articles for you, funding options for phd students.

Pursuing a PhD is a significant commitment of your finances and time. From tuition, living...

How to Choose a PhD Program and Compare Offers

You’ve been patiently waiting for your decision letters to roll in. Now you have the results, and...

Why Study Statistics? Learn from the Director of SMU’s Biostatistics Ph.D.

After earning his PhD in Statistics in 1985 from the University of Chicago, Dr. Daniel Heitjan...

Browse articles by topic

Subscribe to.

To Be or Not To Be a PhD Candidate, That Is the Question

Originally published in the AWIS Magazine.

By Katie Mitzelfelt, PhD Lecturer, University of Washington Tacoma AWIS Member since 2020

Choosing whether or not to work toward a PhD, and then whether or not to finish it, can be very difficult decisions―and there are no right or wrong answers.

Obtaining a PhD is a prestigious accomplishment, and the training allows you to develop your critical-thinking and innovation skills, to conduct research into solving specialized problems, and to learn to troubleshoot when things don’t go as expected. You develop a sense of resilience and a commitment to perseverance, skills which are rewarded when that one experiment finally works and when the answer to your long-sought-after question becomes clear. However, finishing a PhD involves a lot of work, time, and stress. It is mentally, physically, and psychologically exhausting.

There are other ways to hone critical thinking and problem-solving skills and many careers that do not require a PhD such as teaching, science communications, technical writing, quality control, and technician work. Opportunities exist in industries from forensics to food science and everywhere in between.

Countering the Stigma of Perceived Failure

Often we mistakenly view a student’s decision not to pursue a PhD, or to leave a PhD program, as giving up. Many academics view non-PhDs as not smart enough or strong enough to make it. But this is simply not true. In April 2021 Niba Audrey Nirmal produced a vulnerable and inspiring video on the topic of leaving graduate school, titled 10 Stories on Leaving Grad School + Why I Left , on her YouTube channel, NotesByNiba .

In making the video, she hoped to change people’s minds by naming the stigma, shame, and guilty feelings that come with leaving a PhD program. She highlights ten stories from others who either completed their PhD programs or chose to leave, and she goes on to openly share her personal reasons for ending her own doctoral studies in plant genetics at Duke University.

The people showcased in the film share the reasons behind their respective decisions to leave or to stay, as well as heartfelt advice encouraging viewers to make the decision best for them. Participant Sara Whitlock shares, “I decided to leave [my Ph.D. program] . . . but I still had to kind of disentangle myself from that piece of my identity that was all tied up in science research, and that took a long time, but once I did, I was a lot happier.”

Another participant, Dr. Sarah Derouin, states, “Everyone is going to have an opinion about what you do with your life. They’ll have an opinion if you finish your PhD; they’ll have an opinion if you don’t finish your PhD. At the end of the day, you have to realize what is best for you . . . and then make decisions based on that, not on what you think other people will think of you.” In her film, Nirmal recommends the nonprofit organization PhD Balance as a welcoming space for learning about others’ shared experiences.

A Personal Choice

So, do you need a PhD? It depends on what you want to do in your career and in your life. It also depends on your priorities―money, family, free time, fame, advancing science, curiosity, creating cures, saving the planet, etc. (Note that what you value now may shift throughout your life. Your journey will not be a straight line: every step you take will provide an experience that will shape who you are and how you view the world.)

Your decision whether or not to pursue a PhD should be based on your specific goals. Whether or not you obtain a PhD, remember that your journey is unique. The breadth of our experiences as scientists is what yields the diverse perspectives necessary to tackle the world’s difficult problems, now and in the years ahead.

The stories below, based on my own interviews, provide examples of the personal experiences and career choices of some amazing and inspiring scientists. Some of them decided to skip further graduate studies; some chose to go the whole distance on the PhD route; and still others left their doctoral programs behind.

Mai Thao, PhD, Medical Affairs, Medtronic

After completing her undergraduate degree, Dr. Thao worked in a private sector lab. She shared “work was physically exhausting, with little reward. I had no autonomy; instead, I entered a production line similar to the ones that my own parents had endured to provide a living for my family.” While the studies she was working on were important, Dr. Thao felt her contributions to those studies, were minimal. She asserts, “Being naive and a bit arrogant, I thought at that time that I was clearly made for better and greater things, so I quit right in the middle of the Great Recession [2007–2009].” She then pursued a master’s degree in chemistry from California State University, Sacramento, and went on to complete her doctorate in chemistry and biochemistry at Northern Illinois University. Dr. Thao reflects, “In retrospect, I knew that having a PhD would offer me better opportunities and ones with true autonomy.”

When asked how satisfied she is with her decision to complete the doctoral program, Dr. Thao says, “I go back and forth about being satisfied with my decision . . . I was clueless about financing college and even declined multiple schools that offered me full academic scholarships. Today I slowly chip away at my financial error. On the other side, I do have a PhD and can afford to chip away at my mountain of student loan debt. I am also fortunate to be able to really live in the present, to save for the future, and to give.”

Today, Dr. Thao is a scientific resource consultant for internal partners and external key stakeholders at Medtronic. She says, “My day-to-day can range from providing evidence from the literature to supporting scientific claims for marketing purposes. My favorite part of my job is being able to add scientific value to the projects I support. It’s always so rewarding to see how the ideas of engineers and scientists materialize and then to see how the commercial team takes it to market to make a great impact on patients, and I get to see the entire process.

Tam’ra-Kay Francis, PhD, Department of Chemistry, University of Washington

Dr. Francis currently works as a postdoctoral scholar in the chemistry department at the University of Washington. Her research examines “pedagogies and other interventions in higher education that support underrepresented students in STEM. [My] efforts engage both faculty and students in the development of equity-based environments.” She is currently investigating the impact of active learning interventions in the Chemistry Department.

Dr. Francis acknowledges that deciding to pursue a doctorate is a very personal decision. “There are so many things to consider— time, finances, focus area, committee expertise and support, and next steps,” she says. “Not every job requires a PhD, so it is important to stay informed about the expertise required for a career that you are considering.”

She provides advice to prospective graduate students, telling them to do their due diligence when seeking out programs that are right for them. “When interviewing with potential advisers, don’t be afraid to ask specific questions about things that are important to your success. Ask them about their expectations (for example, their philosophies on mentoring and work-life balance) and about the types of support they provide (for example, help with research funding, mental health, and professional development).”

She also suggests reaching out to graduate students in the groups or departments you are interested in. “Ask them directly about what the culture is like and about how they are being supported.” She wants to remind students that they do have a voice and a say in their graduate career. “Your needs will change throughout graduate school, so it is important that you find advocates, both within and outside of your institution, to champion you to the finish line. It is very important that you build your network of support as early as possible,” says Dr. Francis. She credits her adviser, mentors, committee, and former supervisors as being crucial supports in her journey.

“In the first year of my doctoral program, I found an amazing community of scholars from a research interest group (CADASE) within the National Association of Research in Science Teaching. It was a great space to find mentors and build connections in a large professional organization,” said Dr. Francis. At the institutional level, Dr. Francis served as vice president of the Graduate Student Senate and was a member of the Multicultural Graduate Student Organization. For Dr. Francis, her participation in these groups and organizations contributed to her professional growth, sense of community, and success in graduate school.

Liz Goossen, MS, Senior Marketing Specialist at Adaptive Biotechnologies

Reflecting on her decision not to pursue a doctorate, Goossen acknowledges, “I spent a lot of time in graduate school researching potential career paths one could do with a PhD, [and even organized] a career day featuring a dozen speakers from across the country in a variety of scientific fields. By the end, I felt that none of these career options would be a good fit for me (or at least not a good enough fit to warrant five or more years in my program). I worried about going through all of my twenties without starting a 401(k) or having normal working hours, and [I also worried about] all of the other trade-offs there are between finishing a PhD and joining the workforce. I lived in Salt Lake City at the time, and the job market was flooded with PhDs who were overqualified for many of the available positions. By leaving [school] with a master’s, I had more options.”

When asked if she is satisfied with her decision, Goossen says she is 99% satisfied. “There are times I encounter jobs requiring a PhD that look enticing, and [that’s when] I wonder if it may have been nice to have one, but those moments are rare.”

Maureen Kennedy, PhD, Assistant Professor, University of Washington Tacoma

Dr. Kennedy shares that a major factor in her decision to complete a doctorate was the financial support she received. She says, “I was able to maintain funding through research agreements and occasional teaching opportunities that I loved! This consistent funding allowed me to enjoy the freedom of pursuing my PhD on research I found very fulfilling, while also gaining valuable teaching experience. I always felt at home in an academic setting and was happy to stay there while being supported.”

Dr. Kennedy reports being very satisfied with her decision to pursue a doctorate and attributes this satisfaction to knowing that she is making “an impact, both through teaching new generations of students and through being able to continue to pursue [her] favored research topics.” She reflects on some of the positive and negative impacts of her decision: “As a PhD, I am able to direct my own research agenda with relative independence. One major trade-off is that by pursuing an academic career, my salary is likely less than I could get in the private sector with the same skills. My lifetime cumulative salary will also likely be less, due to the years living off of research and teaching stipends, rather than [benefiting from] full-time employment and salary. Also, my years spent as a research scientist funded by soft money, or periodic research grants, were often uncertain; when one grant was winding down, [I had to pursue] new grants.”

Dr. Kennedy remarks that as a tenure-track professor, she has diverse daily activities, which she finds appealing. She shares, “Some days are focused on teaching (particularly during the academic year), some days on research (particularly during the summer), and some days I am able to do both. Before the pandemic, I would come to campus several days a week, but I was also able to work from home on other days. Days are often filled with lectures and office hours, or meetings with research collaborators. I carve out times to focus on reading and writing when I can and when deadlines are approaching. It is definitely a balancing act of time management and of planning, to ensure I am able to fulfill my teaching and research commitments.”

Dr. Kennedy advises that a doctorate “is a long-term commitment. If your goal (or passion!) is a lifetime of leading independent research (with or without teaching), a PhD will help to broaden your available opportunities and will open doors for you.” She cautions that a PhD can “delay your career trajectory and salary growth,” and so she suggests that you carefully research career opportunities and requirements to see whether a doctorate makes sense for you.

Olivia Shan, BS, Restoration Coordinator at Palouse–Clearwater Environmental Institute

Shan attributes her decision not to pursue a graduate degree to cost, lack of time, and uncertainty about what to focus on. She remarks that at some point, she may decide to continue her education, but only if she receives full funding to pay for it. She says she is very satisfied with her decision to enter the workforce right after finishing her undergraduate studies. “After earning my bachelor’s, I worked as a wildland firefighter [and] did [other] jobs I found fun,” says Shan. “Not having any debt after college gave me the flexibility to do what I desired and to explore options. I am all for taking a break from academia and for actually trying out jobs before [narrowing your] focus too far. It would have been a real bummer to spend years on [graduate work I thought I was interested in pursuing] and then later to realize that [this] was not at all what I wanted to do.”

Shan shares that she “adore[s] the diversity of [her] job, and the feeling that [she] is truly helping the environment [and her] community.” She encourages others: “Follow your heart, because you can make a difference no matter your education level. It all comes down to passion, drive, and work ethic!”

Morgan Heinz, MS, Assistant Teaching Professor, University of Washington Tacoma

After completing his master’s degree, Heinz began applying to PhD programs, using the network and interests he had already developed in his previous graduate studies. He could not yet see any other paths for himself. He also wanted to teach college courses and saw the doctorate as the only way to accomplish this goal.

He called and emailed students in the lab to ask them what the environment is like. He received very candid responses and ruled out some labs as a result.

Once he started the PhD program, Heinz found that his doctoral adviser was much more hands-off than his master’s adviser had been and required an unexpected level of independence. This less-directed environment was difficult for Heinz to thrive in. He acknowledges, “I did not have the skill of looking at where the science is, looking for gaps, and seeing how I could contribute.”

These early stages of the PhD process helped him crystallize his passions. He realized that he loves learning and teaching, but he didn’t like synthesizing the literature and determining the next question to ask.

Heinz ultimately decided to take a short hiatus from the doctoral program and taught classes. This interlude reaffirmed his passion for teaching and helped him decide to leave his graduate studies behind.

When he first decided to leave the program, he felt like he was giving up, was worthless, and was a failure. Through continued reflection, he realized, “the side routes that I have taken have actually made me stronger as an instructor.”

After leaving the PhD program, Heinz participated in a community college faculty training program and was hired before even finishing it. He says that the community college allowed anyone to enroll, which was philosophically satisfying and emotionally fulfilling, enabling him to offer an education to any student who wanted it. Heinz tries to impress upon his students that there are a lot of different paths in life. He states, “I don’t have a PhD, and I am exactly where I want to be.”

If you are considering a PhD or masters program, Heinz suggests looking to see if they offer health insurance and mental health services — because graduate school can be stressful and depressing. Many programs may even pay a stipend for you to attend. Heinz also advises, “Don’t be afraid to change your mind. Draw some boundaries.”

Finally, Heinz adds, “Don’t be apologetic about the things that you’re interested in and are excited about, even when people tell you that that’s not an arena for you, because of how you look or who you are. If you’re interested in it, then that’s yours, and you can own it. You don’t need a PhD to validate that interest. You don’t need a PhD to prove your worth in that field. Life is too short to not pursue the things that excite you.”

There Are No Wrong Answers

Whatever decision you make, know that it is the right one for you in the here and now. You may grapple with disappointment or frustration along the way, but regret will not help move you forward. Be grateful for your journey and for how it helps you grow.

Listen to stories and advice, but make the choices that feel right for you. Your story is not the same as anyone else’s. What is right for them, may not be right for you. Be the author of your own life. Your story is beautiful, and you are worthy of living it.

Acknowledgments

A special thank you to Niba Audrey Nirmal, Multimedia Producer & Science Communicator, NotesByNiba, and to Brianna Barbu, Assistant Editor, C&EN, for their thoughtful edits and suggestions on this article.

Dr. Katie Mitzelfelt is currently a biology lecturer at the University of Washington Tacoma. She received her PhD in biochemistry from the University of Utah and researched cardiac regeneration as a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Washington Seattle, prior to transitioning to teaching. She identifies as an educator, content designer, writer, scientist, small business owner, and mom

Join AWIS to access the full issue of AWIS Magazine and more member benefits .

- 1629 K Street, Suite 300, Washington, DC 20006

- (202) 827-9798

Registered 501(c)(3). EIN: 23-7221574

Quick Links

Join AWIS Donate Career Center The Nucleus Advertising

Let's Connect

PRIVACY POLICY – TERMS OF USE

© 2024 Association for Women in Science. All Rights Reserved.

[et_pb_section admin_label=”section”][et_pb_row admin_label=”row”][et_pb_column type=”4_4″][et_pb_contact_form admin_label=”Contact Form” captcha=”off” email=”[email protected]” title=”Download Partner Offerings” use_redirect=”on” redirect_url=”https://awis.org/corporate-packages/” input_border_radius=”0″ use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid” custom_button=”off” button_letter_spacing=”0″ button_use_icon=”default” button_icon_placement=”right” button_on_hover=”on” button_letter_spacing_hover=”0″ success_message=” “]

[et_pb_contact_field field_title=”Name” field_type=”input” field_id=”Name” required_mark=”on” fullwidth_field=”off”]

[/et_pb_contact_field][et_pb_contact_field field_title=”Email Address” field_type=”email” field_id=”Email” required_mark=”on” fullwidth_field=”off”]

[/et_pb_contact_field]

[/et_pb_contact_form][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]

[box type=”download”] Content goes here[/box]

Complimentary membership for all qualified undergraduates/graduates of the institution. Each will receive:

• On-line access to the award-winning AWIS Magazine (published quarterly)

• Receipt of the Washington Wire newsletter which provides career advice and funding opportunities

• Ability to participate in AWIS webinars (both live and on-demand) focused on career and leadership development

• Network of AWIS members and the ability to make valuable connections at both the local and national levels

Up to 7 complimentary memberships for administrators, faculty, and staff. Each will receive:

• A copy of the award-winning AWIS Magazine (published quarterly)

• 24 Issues of the Washington Wire newsletter which provides career advice and funding opportunities

• Access to AWIS webinars (both live and on-demand) focused on career and leadership development

Big PhD questions: Should I do a PhD?

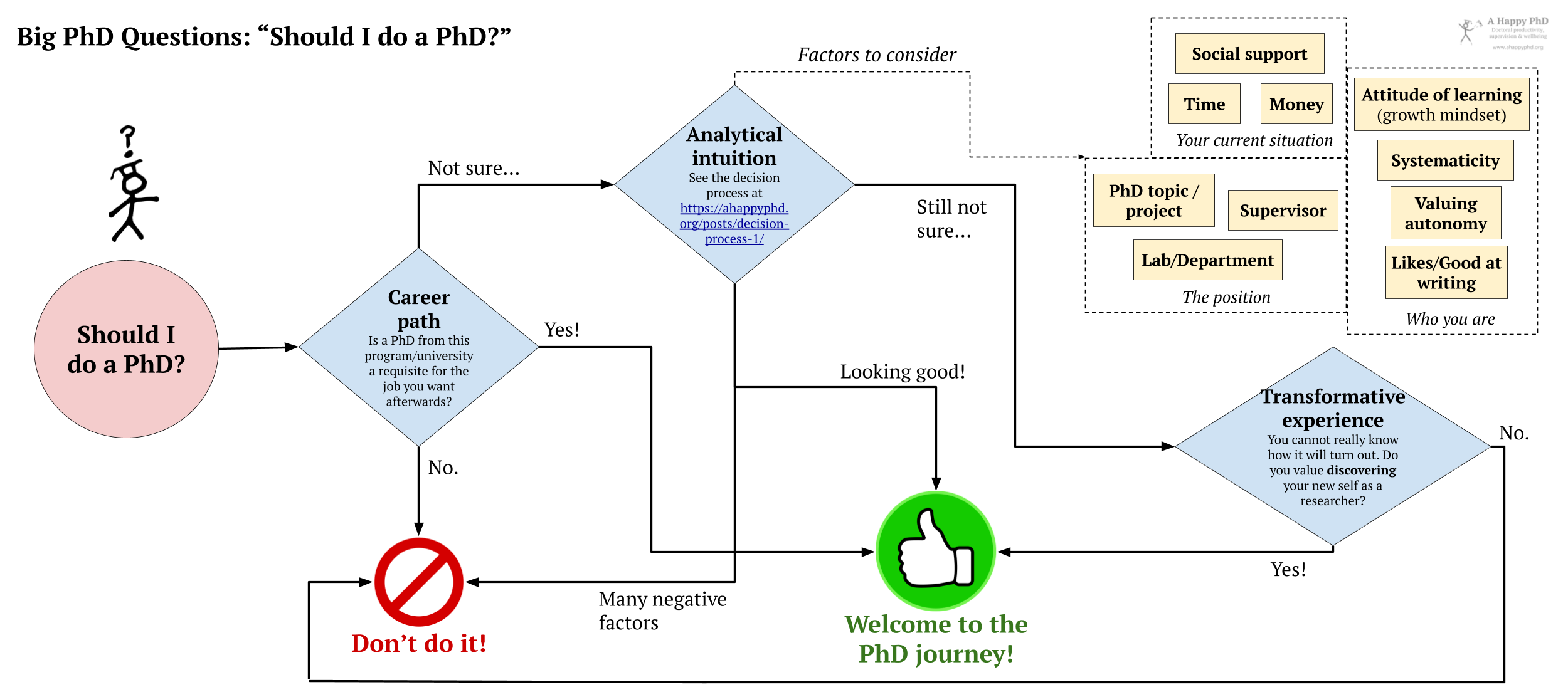

If you are reading this, chances are that you have already decided to do a PhD. Yet, you may know someone who is considering a doctoral degree (or you may be offering such a position as a supervisor to prospective students). This post is for them . In this new type of post, we will look at big questions facing any PhD student. Today, we analyze the question that precedes all the other big PhD questions: “should I do a PhD?”. Below, I offer a couple of quick, simple ways to look at this important life decision, and a list of 10 factors to consider when offered (or seeking) a PhD position.

The other day, some researcher colleagues told me about a brilliant master student of theirs, to whom they were offering the possibility of doing a PhD in their lab. However, the student was doubtful: should she embark on this long and uncertain journey, on a low income, foregoing higher salaries (and maybe more stability) if she entered the job market right away? Her family and friends, not really knowing what a PhD or academia are like, were also giving all sorts of (sometimes contradictory) advice. Should she do a PhD?

This simple question is not asked nearly as much (or as seriously) as it should. Many people (myself included!) have embarked on this challenging, marathon-like experience without a clear idea of why it is the right choice for them, for that particular moment in their lives. Given this lack of clarity, we shouldn’t be surprised by the high rates of people that drop out of doctoral programs , or that develop mental health issues , once they hit the hard parts of the journey.

So, let’s approach this big PhD question from a few different angles…

A first short answer: Thinking about the career path

When I started my PhD back in 2007, coming from a job in the industry, I only had a very nebulous idea that I might like to do research professionally (albeit, to be honest, what I liked most about research was the travelling and the working with foreign, smart people). My employer back then was encouraging us to earn doctoral degrees as a way to pump up the R&D output. Thus I started a PhD, without a clear idea of a topic, of who would be my supervisor, or what I would do with my life once I had the doctoral degree in my hands.

This is exactly what some career advice experts like Cal Newport say you should NOT do . They argue that graduate degrees (also including Master’s) should not be pursued due to a generic idea that having them will improve our “job prospects” or “hirability”, that it will help us “land a job” more easily. Rather, they propose to take a cold, hard look to what we want to do after the doctorate (do I want to be a Professor? if so, where? do I want a job in the industry? in which company? etc.). Then, pursue the PhD only if we have proof that a PhD, from the kind of university program we can get into 1 , is a necessary requisite for that job .

If you aspire to be an academic (and maybe get tenure), do not take that aspiration lightly: such positions are becoming increasingly rare and competition for them is fiercer than ever. Take a look at the latest academic positions in your field at your target university, and who filled them. Do you have a (more or less) similar profile? In some highly prestigious institutions, you need to be some kind of “superstar” student, coming from a particular kind of university, if you want to get that kind of job.

In general, I agree with Cal that we should not generically assume that a PhD will be useful or get us a job in a particular area, unless we have hard evidence on that (especially if we want a job in the industry!). Also, I agree that the opportunity cost of a PhD should not be underestimated: if you enroll in a PhD program, you will probably be in for a reduction in salary (compared with most industry jobs), for a period of four or more years!

Yet, for some of us, the plan about what to do after the PhD may not be so clear (as it was my case back in 2007). Also, being too single-minded about what our future career path should look like has its own problems 2 . Indeed, there are plenty of examples of people that started a PhD without a clear endgame in mind, who finished it happily and went on to become successful academics or researchers. Ask any researcher you know!

So, if this first answer to ‘should I do a PhD?' did not give us a clear answer, maybe we need a different approach. Read on.

A longer answer: Factors for a happy (or less sucky) PhD

If we are still unsure of whether doing a PhD is a good idea, we can do worse than to follow the decision-making advice I have proposed in a previous post for big decisions during the PhD. In those posts, I describe a three-step process in which we 1) expand our understanding of the options available (not just to do or not do a PhD, but also what PhD places are available, what are our non-PhD alternative paths, etc.); 2) analyze (and maybe prototype) and visualize the different options; and 3) take the decision and move on with it.

However, one obstacle we may face when applying that process to this particular decision is the “analytic intuition” step , in which we evaluate explicitly different aspects of each of the options, to inform our final, intuitive (i.e., “gut feeling”) decision. If we have never done a PhD or been in academia, we may be baffled about what are the most important aspects to consider when making such an evaluation about a particular PhD position, or whether a PhD is a good path for us at all.

Below, I outline ten factors that I have observed are related to better, happier (but not necessarily stress-free!) PhD processes and outcomes. Contrary to many other posts in this blog (where I focus on the factors that we have control over ), most of the items below are factors outside our direct control as PhD students, or which are hard to change all by ourselves. Things like our current life situation, what kind of person we are, or the particular supervisor/lab/topic where we would do the PhD. Such external or hard-to-change aspects are often the ones that produce most frustration (and probably lead to bad mental health or dropout outcomes) once we are on the PhD journey:

- Time . This is pretty obvious, but often overlooked. Do we have time in our days to actually do a PhD (or can we make enough time by stopping other things we currently do)? PhD programs are calibrated to take 3-4 years to complete, working at least 8 hours a day. And the sheer amount of hours spent working on thesis materials seems to be the most noticeable predictor of everyday progress in the PhD , according to (still unpublished) studies we are doing of doctoral student diaries and self-tracking (and, let’s remember, progress itself is the most important factor in completing a PhD 3 ). And there is also the issue of our mental energy : if we think that we can solve the kind of cognitively demanding tasks that a PhD entails, after 8 hours of an unrelated (and potentially stressful) day job, maybe we should think again. Abandon the idea that you can do a PhD (and actually enjoy it) while juggling two other day jobs and taking care of small kids. Paraphrasing one of my mentors, “a PhD is not a hobby”, it is a full-time job! Ignore this advice at your own risk.

- Money . This is related to the previous one (since time is money, as they say), but deserves independent evaluation. How are we going to support ourselves economically during the 3+ years that a PhD lasts? In many countries, there exist PhD positions that pay a salary (if we can get access to those). Is that salary high enough to support us (and maybe our family, depending on our situation) during those years? If we do not have access to these paid PhD positions (or the salary is too low for our needs), how will we be supported? Do we have enough savings to keep us going for the length of the PhD? can our spouse or our family support us? If we plan on taking/keeping an unrelated job for such economic support, read again point #1. Also, consider the obligations that a particular paid PhD position has: sometimes it requires us to work on a particular research project (which may or may not be related to our PhD topic), sometimes it requires us to teach at the university (which does not help us advance in our dissertation), etc. As stated in the decision process advice , it is important to talk to people currently in that kind of position or situation, to see how they actually spend their time (e.g., are they so stressed by the teaching load that they do not have time to advance in the dissertation?).

- Having social support (especially, outside academia). This one is also quite obvious, but bears mentioning anyways. Having strong social ties is one of the most important correlates of good mental health in the doctorate , and probably also helps us across the rough patches of the PhD journey towards completion. Having a supportive spouse, family, or close friends to whom we can turn when things are bad, or with whom we can go on holidays or simply unwind and disconnect from our PhD work from time to time, will be invaluable. Even having kids is associated with lower risk of mental health symptoms during the doctorate (which is somewhat counter-intuitive, and probably depends on whether you have access to childcare or not). A PhD can be a very lonely job sometimes, and there is plenty of research showing that loneliness is bad for our mental and physical health!

- An attitude of learning . Although this is a somewhat squishy factor, it is probably the first that came to my mind, stemming from my own (anecdotal, non-scientific) observation of PhD students in different labs and universities. Those that were excited to learn new things, to read the latest papers on a topic, to try a new methodology, seem to be more successful at doing the PhD (and look happier to me). People that are strong in curiosity seem a good match for a scientific career, which is in the end about answering questions (even if curiosity also has its downsides ). This personal quality can also be related to Dweck’s growth mindset (the belief that our intelligence and talents are not fixed and can be learned) 4 . If you are curious , this mindset can be measured in a variety of ways .

- A knack for systematicity and concentration. This one is, in a sense, the counterweight to the previous one. Curious people often have shorter attention spans, so sometimes they ( we , I should say) have trouble concentrating or focusing on the same thing for a long period of time. Yet, research is all about following a particular method in a systematic and consistent way, and often requires long periods of focus and concentration. Thus, if we find ourselves having trouble with staying with one task, idea or project for more than a few minutes in a row, we may be in for trouble. The PhD requires to pursue a single idea for years !

- Valuing autonomy . As I mentioned in passing above, a PhD is, by definition, an individual achievement (even if a lot of research today requires teamwork and collaboration). Thus, to be successful (and even enjoy) the process of the PhD, we have to be comfortable being and working alone, at least for some of the time. Spending years developing our own contribution to knowledge that no one else has come up with before, should not feel like a weird notion to us. Even if it occasionally comes with the uncomfortable uncertainty of not knowing whether our ideas will work out. In human values research they call this impulse to define our own direction, autonomy 5 , and many of my researcher friends tell me it is a very common trait in researchers. However, these values are very personal and very cultural. To evaluate this factor, we could simply ask ourselves how much we value this autonomy over other things in life, or use validated instruments to measure relative value importance, like the Portrait Values Questionnaire (PVQ) .

- Liking and/or being good at writing . I have written quite a bit here about the importance (and difficulty) of writing in the PhD . Be it writing journal and conference papers, or the dissertation tome itself, every PhD student spends quite a bit of time writing, as a way of conveying new knowledge in a clear, concise and systematic way. Learning to write effectively is also known to be one of the common difficulties of many PhD processes 6 , due to reasons discussed elsewhere . Hence, if we hate writing, we should think carefully about spending the next 3+ years doing something that necessarily involves quite a bit of writing, other people spotting flaws in your writing, and rewriting your ideas multiple times. Please note that I don’t consider being a good (academic or nonfiction) writer a necessary requisite for a PhD, as it can be learned like any other skill (again, the learning attitude in point #4 will help with that!). But being good at it will certainly make things easier and will let you focus on the content of the research, rather than on learning this new, complex skill.

- Compatibility (or, as they call it in the literature sometimes, the “fit”) of our and their personalities, ways of working (e.g., do they like micro-managing people, but you hate people looking over your shoulder?) and expectations about what a doctoral student and a supervisor should do.

- A concern for you as a person. Since this is difficult to evaluate as we may not know each other yet, we could use their concern about the people that work in their lab (beyond being just a source of cheap labor), as a proxy.

- Enthusiasm for the field of research or topic, its importance in the world, etc. A cynic, jaded researcher may not be the best person to guide us to be a great member of the scientific community.

- A supervisor that is well-known, an expert in the particular topic of the dissertation. Looking at the number of citations, e.g., in Google Scholar is a good initial indicator, but look at the publication titles (are they in similar topics to those they are offering you as your doctoral project? if not, that may mean that this person may also be new to your particular dissertation topic!).

- Related to the previous one, does this researcher have a good network of (international) contacts in other institutions? Do they frequently co-author papers with researchers in other labs/countries? We may be able to benefit from such contact network, and get wind of important opportunities during the dissertation and for our long-term research career.