Educator Resources

Brown v. Board of Education

The Supreme Court's opinion in the Brown v. Board of Education case of 1954 legally ended decades of racial segregation in America's public schools. Chief Justice Earl Warren delivered the unanimous ruling in the landmark civil rights case. State-sanctioned segregation of public schools was a violation of the 14th Amendment and was therefore unconstitutional. This historic decision marked the end of the "separate but equal" precedent set by the Supreme Court nearly 60 years earlier and served as a catalyst for the expanding civil rights movement. Read more...

Primary Sources

Links go to DocsTeach , the online tool for teaching with documents from the National Archives.

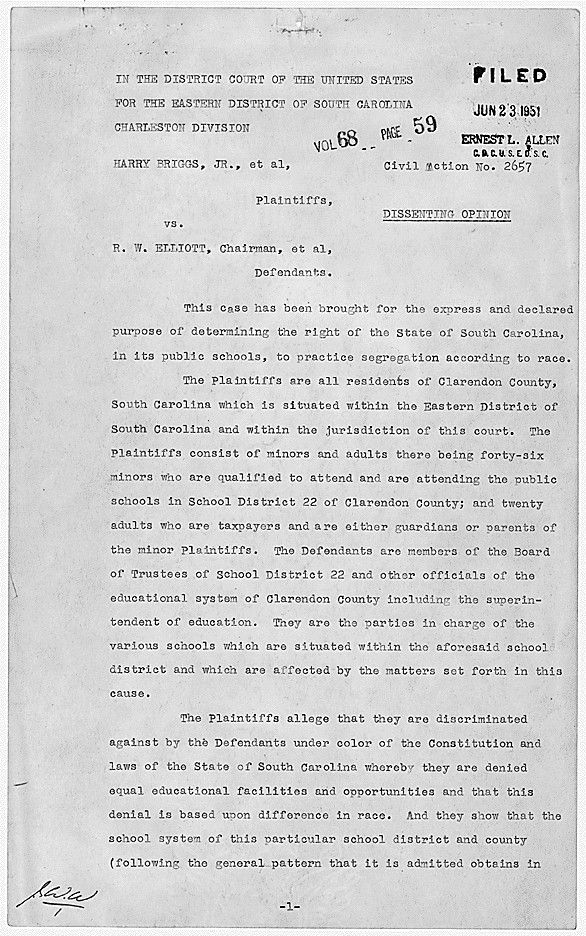

Dissenting opinion in Briggs v. Elliott in which Judge Waties Waring opposed the District Court ruling that "separate but equal" schools were not in violation of the 14th amendment – he presented arguments that would later be used by the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas , 6/21/1951

View in National Archives Catalog

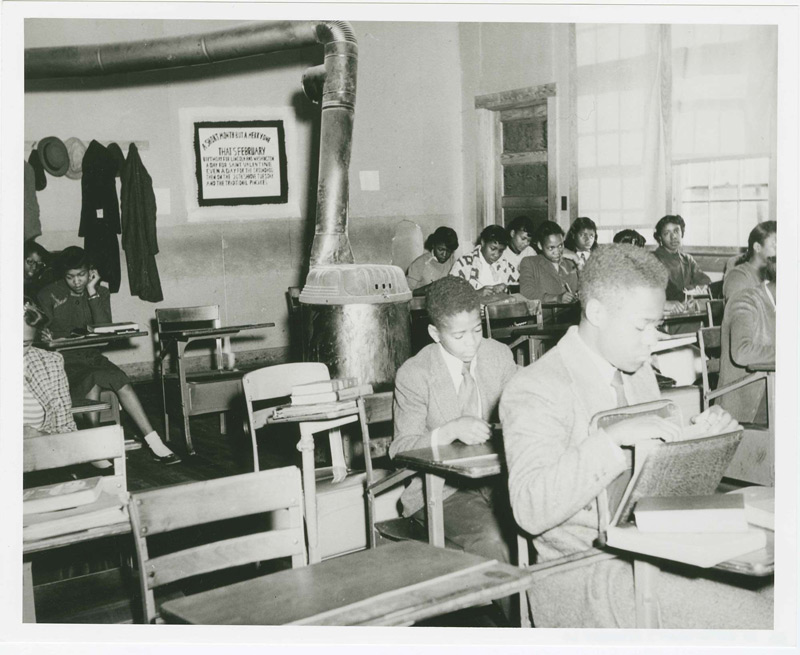

English class at Moton High School , a school for Black students, one of several photographs entered as evidence in the case Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia , which was one of five cases that the Supreme Court consolidated under Brown v. Board of Education , ca. 1951

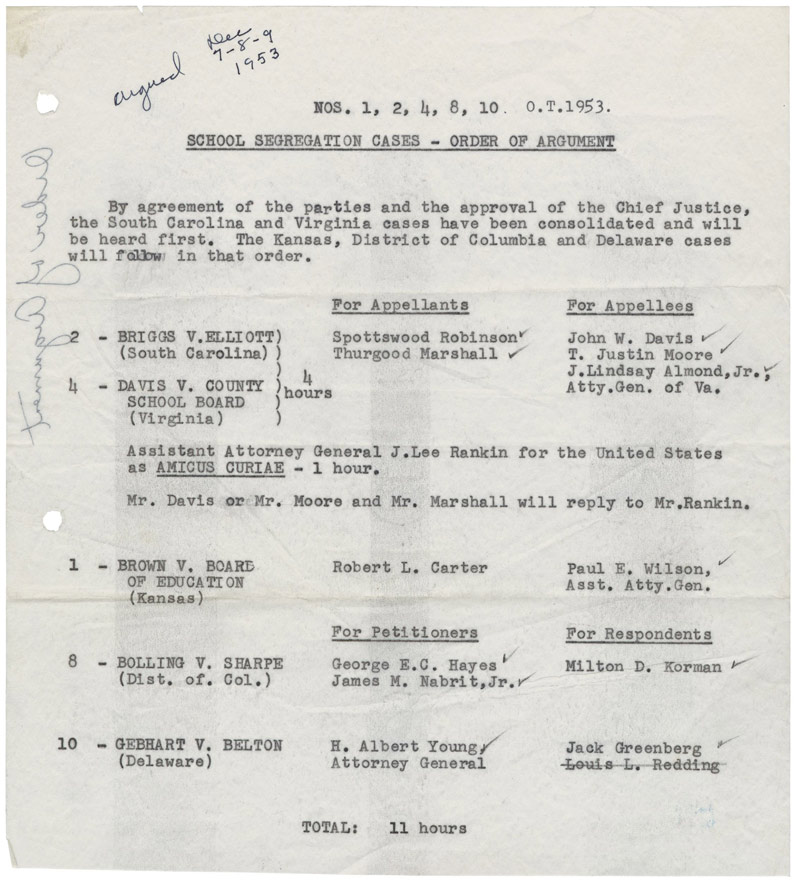

Order of Argument in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka during which attorneys reargued the five cases that the Supreme Court heard collectively and consolidated under the name Brown v. Board of Education , 12/1953

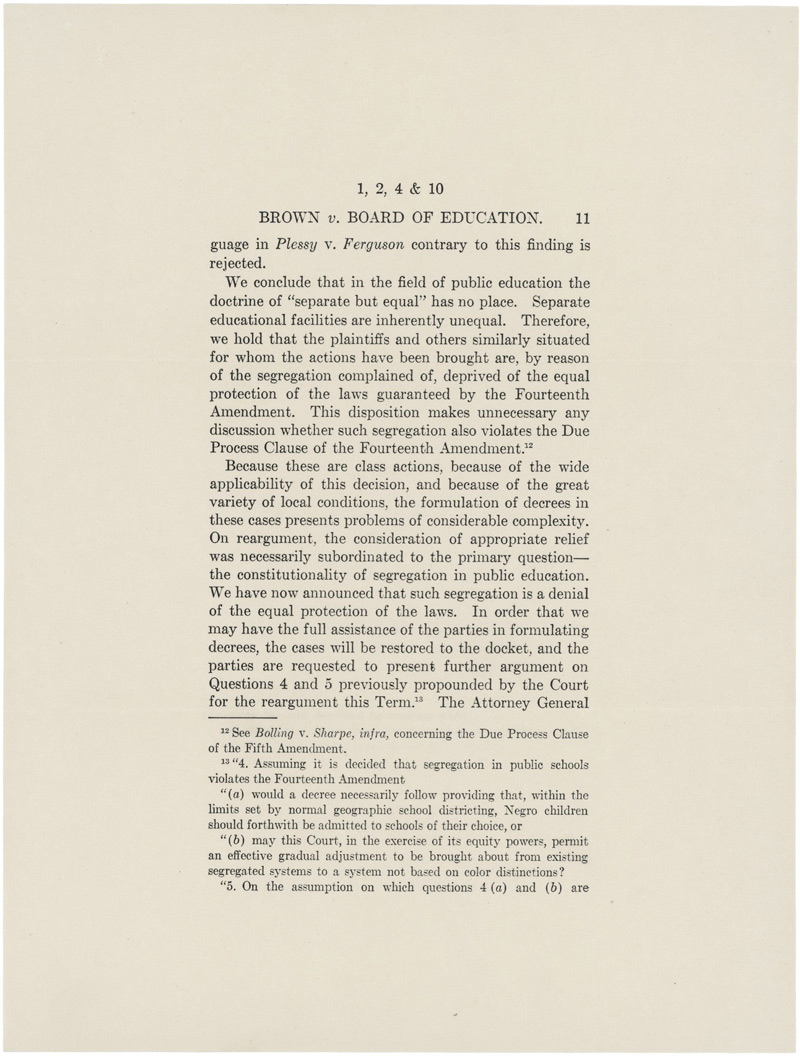

Page 11 of the unanimous Supreme Court ruling of 5/17/1954 in Brown v. Board of Education that state-sanctioned segregation of public schools violated the 14th Amendment, marking the end of the "separate but equal" precedent

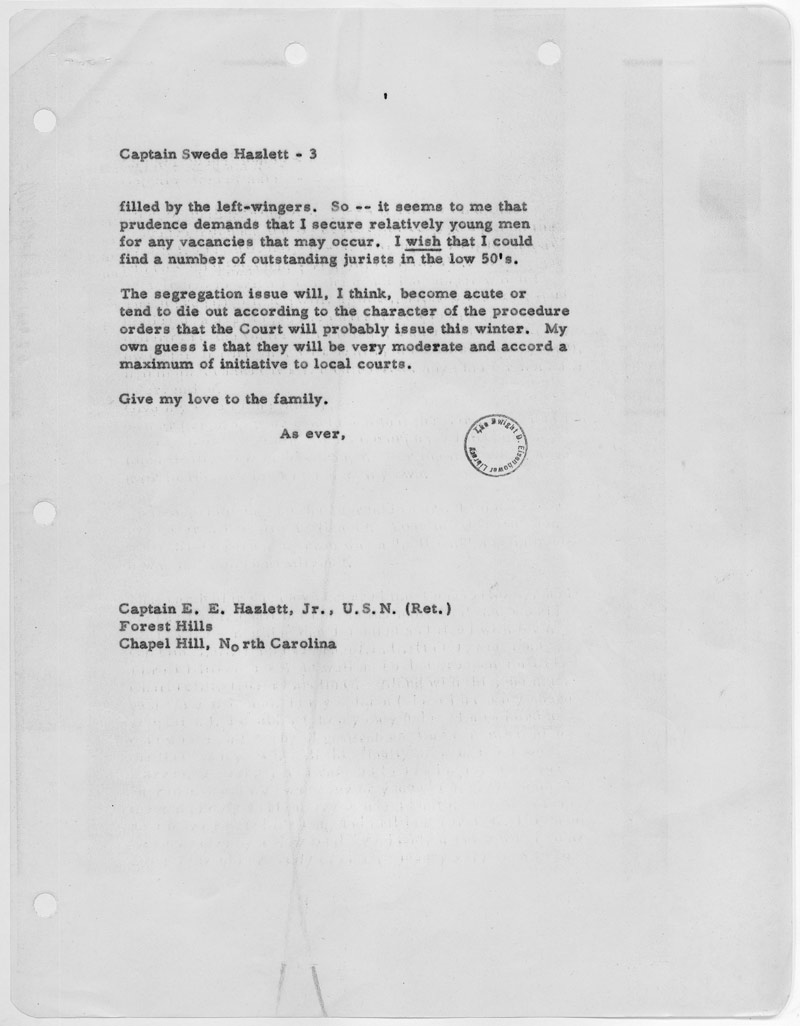

Page 3 of a letter from President Eisenhower to E. E. "Swede" Hazlett in which the President expressed his belief that the new Warren court would be very moderate on the issue of segregation, 10/23/1954

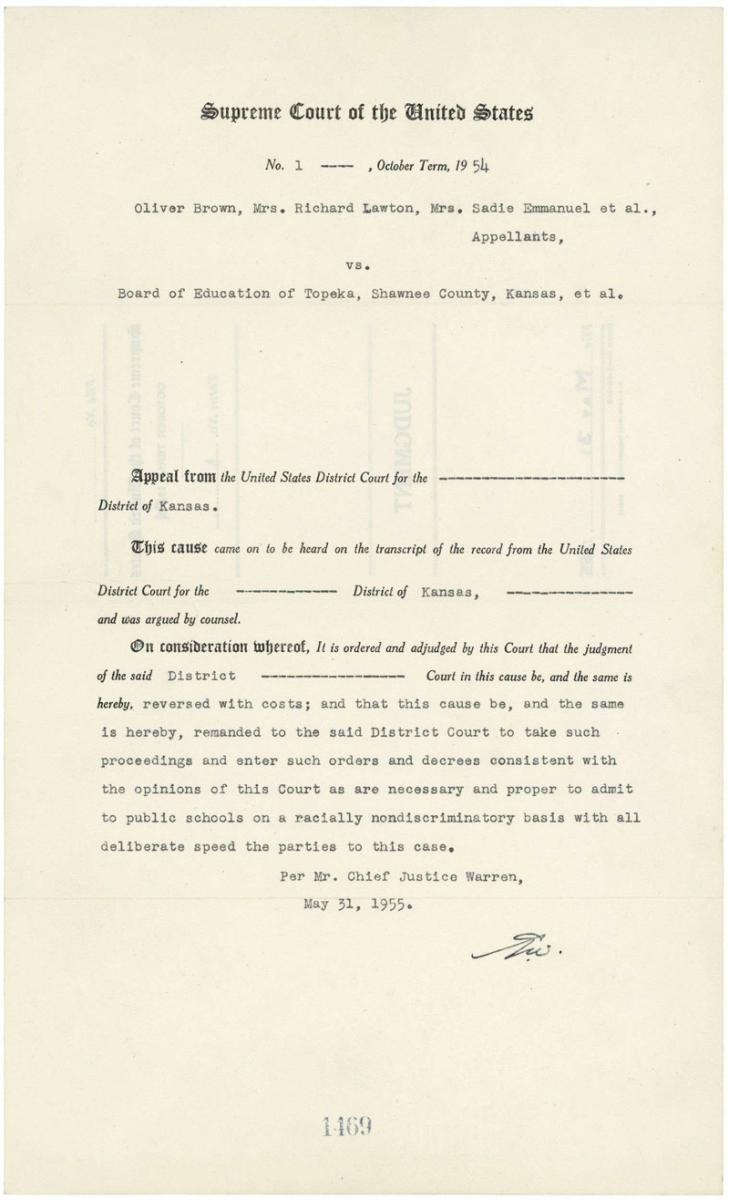

Judgment of May 31, 1955, in Brown v. Board of Education (Brown II) – a year after the ruling that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional – directing that schools be desegregated "with all deliberate speed"

- Brown v. Board of Education Timeline

- Biographies of Key Figures

- Related Primary Sources: Photographs from the Dorothy Davis Case

Teaching Activities

The "Rights in America" page on DocsTeach includes primary sources and document-based teaching activities related to how individuals and groups have asserted their rights as Americans. It includes topics such as segregation, racism, citizenship, women's independence, immigration, and more.

Additional Background Information

While the 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution outlawed slavery, it wasn't until three years later, in 1868, that the 14th Amendment guaranteed the rights of citizenship to all persons born or naturalized in the United States, including due process and equal protection of the laws. These two amendments, as well as the 15th Amendment protecting voting rights, were intended to eliminate the last remnants of slavery and to protect the citizenship of Black Americans.

In 1875, Congress also passed the first Civil Rights Act, which held the "equality of all men before the law" and called for fines and penalties for anyone found denying patronage of public places, such as theaters and inns, on the basis of race. However, a reactionary Supreme Court reasoned that this act was beyond the scope of the 13th and 14th Amendments, as these amendments only concerned the actions of the government, not those of private citizens. With this ruling, the Supreme Court narrowed the field of legislation that could be supported by the Constitution and at the same time turned the tide against the civil rights movement.

By the late 1800s, segregation laws became almost universal in the South where previous legislation and amendments were, for all practical purposes, ignored. The races were separated in schools, in restaurants, in restrooms, on public transportation, and even in voting and holding office.

Plessy v. Ferguson

In 1896, the Supreme Court upheld the lower courts' decision in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson . Homer Plessy, a Black man from Louisiana, challenged the constitutionality of segregated railroad coaches, first in the state courts and then in the U. S. Supreme Court.

The high court upheld the lower courts, noting that since the separate cars provided equal services, the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment was not violated. Thus, the "separate but equal" doctrine became the constitutional basis for segregation. One dissenter on the Court, Justice John Marshall Harlan, declared the Constitution "color blind" and accurately predicted that this decision would become as baneful as the infamous Dred Scott decision of 1857.

In 1909 the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was officially formed to champion the modern Civil Rights Movement. In its early years its primary goals were to eliminate lynching and to obtain fair trials for Black Americans. By the 1930s, however, the activities of the NAACP began focusing on the complete integration of American society. One of their strategies was to force admission of Black Americans into universities at the graduate level where establishing separate but equal facilities would be difficult and expensive for the states.

At the forefront of this movement was Thurgood Marshall, a young Black lawyer who, in 1938, became general counsel for the NAACP's Legal Defense and Education Fund. Significant victories at this level included Gaines v. University of Missouri in 1938, Sipuel v. Board of Regents of University of Oklahoma in 1948, and Sweatt v. Painter in 1950. In each of these cases, the goal of the NAACP defense team was to attack the "equal" standard so that the "separate" standard would in turn become susceptible.

Five Cases Consolidated under Brown v. Board of Education

By the 1950s, the NAACP was beginning to support challenges to segregation at the elementary school level. Five separate cases were filed in Kansas, South Carolina, Virginia, the District of Columbia, and Delaware:

- Oliver Brown et al. v. Board of Education of Topeka, Shawnee County, Kansas, et al.

- Harry Briggs, Jr., et al. v. R.W. Elliott, et al.

- Dorothy E. Davis et al. v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia, et al.

- Spottswood Thomas Bolling et al. v. C. Melvin Sharpe et al.

- Francis B. Gebhart et al. v. Ethel Louise Belton et al.

While each case had its unique elements, all were brought on the behalf of elementary school children, and all involved Black schools that were inferior to white schools. Most importantly, rather than just challenging the inferiority of the separate schools, each case claimed that the "separate but equal" ruling violated the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment.

The lower courts ruled against the plaintiffs in each case, noting the Plessy v. Ferguson ruling of the United States Supreme Court as precedent. In the case of Brown v. Board of Education , the Federal district court even cited the injurious effects of segregation on Black children, but held that "separate but equal" was still not a violation of the Constitution. It was clear to those involved that the only effective route to terminating segregation in public schools was going to be through the United States Supreme Court.

In 1952 the Supreme Court agreed to hear all five cases collectively. This grouping was significant because it represented school segregation as a national issue, not just a southern one. Thurgood Marshall, one of the lead attorneys for the plaintiffs (he argued the Briggs case), and his fellow lawyers provided testimony from more than 30 social scientists affirming the deleterious effects of segregation on Black and white children. These arguments were similar to those alluded to in the Dissenting Opinion of Judge Waites Waring in Harry Briggs, Jr., et al. v. R. W. Elliott, Chairman, et al . (shown above).

These [social scientists] testified as to their study and researches and their actual tests with children of varying ages and they showed that the humiliation and disgrace of being set aside and segregated as unfit to associate with others of different color had an evil and ineradicable effect upon the mental processes of our young which would remain with them and deform their view on life until and throughout their maturity....They showed beyond a doubt that the evils of segregation and color prejudice come from early training...it is difficult and nearly impossible to change and eradicate these early prejudices however strong may be the appeal to reason…if segregation is wrong then the place to stop it is in the first grade and not in graduate colleges.

The lawyers for the school boards based their defense primarily on precedent, such as the Plessy v. Ferguson ruling, as well as on the importance of states' rights in matters relating to education.

Realizing the significance of their decision and being divided among themselves, the Supreme Court took until June 1953 to decide they would rehear arguments for all five cases.

The arguments were scheduled for the following term. The Court wanted briefs from both sides that would answer five questions, all having to do with the attorneys' opinions on whether or not Congress had segregation in public schools in mind when the 14th amendment was ratified.

The Order of Argument (shown above) offers a window into the three days in December of 1953 during which the attorneys reargued the cases. The document lists the names of each case, the states from which they came, the order in which the Court heard them, the names of the attorneys for the appellants and appellees, the total time allotted for arguments, and the dates over which the arguments took place.

Briggs v. Elliott

The first case listed, Briggs v. Elliott , originated in Clarendon County, South Carolina, in the fall of 1950. Harry Briggs was one of 20 plaintiffs who were charging that R.W. Elliott, as president of the Clarendon County School Board, violated their right to equal protection under the fourteenth amendment by upholding the county's segregated education law. Briggs featured social science testimony on behalf of the plaintiffs from some of the nation's leading child psychologists, such as Dr. Kenneth Clark, whose famous doll study concluded that segregation negatively affected the self-esteem and psyche of African-American children. Such testimony was groundbreaking because on only one other occasion in U.S. history had a plaintiff attempted to present such evidence before the Court.

Thurgood Marshall, the noted NAACP attorney and future Supreme Court Justice, argued the Briggs case at the District and Federal Court levels. The U.S. District Court's three-judge panel ruled against the plaintiffs, with one judge dissenting, stating that "separate but equal" schools were not in violation of the 14th amendment. In his dissenting opinion (shown above), Judge Waties Waring presented some of the arguments that would later be used by the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas . The case was appealed to the Supreme Court.

Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia

Marshall also argued the Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia, case at the Federal level. Originally filed in May of 1951 by plaintiff's attorneys Spottswood Robinson and Oliver Hill, the Davis case, like the others, argued that Virginia's segregated schools were unconstitutional because they violated the equal protection clause of the fourteenth amendment. And like the Briggs case, Virginia's three-judge panel ruled against the 117 students who were identified as plaintiffs in the case. (For more on this case, see Photographs from the Dorothy Davis Case .)

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka

Listed third in the order of arguments, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka was initially filed in February of 1951 by three Topeka area lawyers, assisted by the NAACP's Robert Carter and Jack Greenberg. As in the Briggs case, this case featured social science testimony on behalf of the plaintiffs that segregation had a harmful effect on the psychology of African-American children. While that testimony did not prevent the Topeka judges from ruling against the plaintiffs, the evidence from this case eventually found its way into the wording of the Supreme Court's May 17, 1954 opinion. The Court concluded that:

To separate them [children in grade and high schools] from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely to ever be undone.

Bolling v. Sharpe

Because Washington, D.C., is a Federal territory governed by Congress and not a state, the Bolling v. Sharpe case was argued as a fifth amendment violation of "due process." The fourteenth amendment only mentions states, so this case could not be argued as a violation of "equal protection," as were the other cases. When a District of Columbia parent, Gardner Bishop, unsuccessfully attempted to get 11 African-American students admitted into a newly constructed white junior high school, he and the Consolidated Parents Group filed suit against C. Melvin Sharpe, president of the Board of Education of the District of Columbia. Charles Hamilton Houston, the NAACP's special counsel, former dean of the Howard University School of Law, and mentor to Thurgood Marshall, took up the Bolling case.

With Houston's health already failing in 1950 when he filed suit, James Nabrit, Jr. replaced Houston as the original attorney. By the time the case reached the Supreme Court on appeal, George E.C. Hayes had been added as an attorney for the petitioners, beside James Nabrit, Jr. According to the Court, due to the decision in Plessy , "the plaintiffs and others similarly situated" had been "deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment," therefore, segregation of America's public schools was unconstitutional.

Belton v. Gebhart

The last case listed in the order of arguments, Belton v. Gebhart , was actually two nearly identical cases (the other being Bulah v. Gebhart ), both originating in the state of Delaware in 1952. Ethel Belton was one of the parents listed as plaintiffs in the case brought in Claymont, while Sarah Bulah brought suit in the town of Hockessin, Delaware. While both of these plaintiffs brought suit because their African-American children had to attend inferior schools, Sarah Bulah's situation was unique in that she was a white woman with an adopted Black child, who was still subject to the segregation laws of the state. Local attorney Louis Redding, Delaware's only African-American attorney at the time, originally argued both cases in Delaware's Court of Chancery. NAACP attorney Jack Greenberg assisted Redding. Belton/Bulah v. Gebhart was argued at the Federal level by Delaware's attorney general, H. Albert Young.

Supreme Court Rehears Arguments

Reargument of the Brown v. Board of Education cases at the Federal level took place December 7-9, 1953. Throngs of spectators lined up outside the Supreme Court by sunrise on the morning of December 7, although arguments did not actually commence until one o'clock that afternoon. Spottswood Robinson began the argument for the appellants, and Thurgood Marshall followed him. Virginia's Assistant Attorney General, T. Justin Moore, followed Marshall, and then the court recessed for the evening.

On the morning of December 8, Moore resumed his argument, followed by his colleague, J. Lindsay Almond, Virginia's Attorney General. Following this argument, Assistant United States Attorney General J. Lee Rankin, presented the U.S. government's amicus curiae brief on behalf of the appellants, which showed its support for desegregation in public education. In the afternoon, Robert Carter began arguments in the Kansas case, and Paul Wilson, Attorney General for the state of Kansas, followed him in rebuttal.

On December 9, after James Nabrit and Milton Korman debated Bolling , and Louis Redding, Jack Greenberg, and Delaware's Attorney General, H. Albert Young argued Gebhart , the Court recessed. The attorneys, the plaintiffs, the defendants, and the nation waited five months and eight days to receive the unanimous opinion of Chief Justice Earl Warren's court, which declared, "in the field of public education, the doctrine of 'separate but equal' has no place."

The Warren Court

In September 1953, President Eisenhower had appointed Earl Warren, governor of California, as the new Supreme Court chief justice. Eisenhower believed Warren would follow a moderate course of action toward desegregation. His feelings regarding the appointment are detailed in the closing paragraphs of a letter he wrote to E. E. "Swede" Hazlett, a childhood friend (shown above). On the issue of segregation, Eisenhower believed that the new Warren court would "be very moderate and accord a maximum initiative to local courts."

In his brief to the Warren Court that December, Thurgood Marshall described the separate but equal ruling as erroneous and called for an immediate reversal under the 14th Amendment. He argued that it allowed the government to prohibit any state action based on race, including segregation in public schools. The defense countered this interpretation pointing to several states that were practicing segregation at the time they ratified the 14th Amendment. Surely they would not have done so if they had believed the 14th Amendment applied to segregation laws. The U.S. Department of Justice also filed a brief; it was in favor of desegregation but asked for a gradual changeover.

Over the next few months, the new chief justice worked to bring the splintered Court together. He knew that clear guidelines and gradual implementation were going to be important considerations, as the largest concern remaining among the justices was the racial unrest that would doubtless follow their ruling.

The Supreme Court Ruling

Finally, on May 17, 1954, Chief Justice Earl Warren read the unanimous opinion: school segregation by law was unconstitutional (shown above). Arguments were to be heard during the next term to determine exactly how the ruling would be imposed.

Just over one year later, on May 31, 1955, Warren read the Court's unanimous decision, now referred to as Brown II (also shown above). It instructed states to begin desegregation plans "with all deliberate speed." Warren employed careful wording in order to ensure backing of the full Court in his official judgment.

The Brown decision was a watershed in American legal and civil rights history because it overturned the "separate but equal" doctrine first articulated in the Plessy v. Ferguson decision of 1896. By overturning Plessy , the Court ended America's 58-year-long practice of legal racial segregation and paved the way for the integration of America's public school systems.

Despite two unanimous decisions and careful, if not vague, wording, there was considerable resistance to the Supreme Court's ruling in Brown v. Board of Education . In addition to the obvious disapproving segregationists were some constitutional scholars who felt that the decision went against legal tradition by relying heavily on data supplied by social scientists rather than precedent or established law. Supporters of judicial restraint believed the Court had overstepped its constitutional powers by essentially writing new law.

However, minority groups and members of the Civil Rights Movement were buoyed by the Brown decision even without specific directions for implementation. Proponents of judicial activism believed the Supreme Court had appropriately used its position to adapt the basis of the Constitution to address new problems in new times. The Warren Court stayed this course for the next 15 years, deciding cases that significantly affected not only race relations, but also the administration of criminal justice, the operation of the political process, and the separation of church and state.

Parts of this text were adapted from an article written by Mary Frances Greene, a teacher at Marie Murphy School in Wilmette, IL.

- Find a Lawyer

- Ask a Lawyer

- Research the Law

- Law Schools

- Laws & Regs

- Newsletters

- Justia Connect

- Pro Membership

- Basic Membership

- Justia Lawyer Directory

- Platinum Placements

- Gold Placements

- Justia Elevate

- Justia Amplify

- PPC Management

- Google Business Profile

- Social Media

- Justia Onward Blog

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)

The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits states from segregating public school students on the basis of race. This marked a reversal of the "separate but equal" doctrine from Plessy v. Ferguson that had permitted separate schools for white and colored children provided that the facilities were equal.

Based on an 1879 law, the Board of Education in Topeka, Kansas operated separate elementary schools for white and African-American students in communities with more than 15,000 residents. The NAACP in Topeka sought to challenge this policy of segregation and recruited 13 Topeka parents to challenge the law on behalf of 20 children. In 1951, each of the families attempted to enroll the children in the school closest to them, which were schools designated for whites. Each child was refused admission and directed to the African-American schools, which were much further from where they lived. For example, Linda Brown, the daughter of the named plaintiff, could have attended a white school several blocks from her house but instead was required to walk some distance to a bus stop and then take the bus for a mile to an African-American school. Once the children had been refused admission to the schools designated for whites, the NAACP brought the lawsuit. They were unsuccessful at the trial court level, where the 1896 Supreme Court precedent in Plessy v. Ferguson was found to be decisive. Even though the trial court agreed that educational segregation had a negative effect on African-American children, it applied the standard of Plessy in finding that the white and African-American schools offered sufficiently equal quality of teachers, curricula, facilities, and transportation. Since the NAACP did not challenge the details of those findings, it essentially cast the appeal as a direct challenge to the system imposed by Plessy. When the Supreme Court heard the appeal, it combined Brown with four other cases addressing parallel issues in South Carolina, Virginia, Delaware, and Washington, D.C. The NAACP was responsible for bringing each of these lawsuits, and it had lost on each of them at the trial court level except the Delaware case of Gebhart v. Belton. Brown stood apart from the others in the group as the only case that challenged the separate but equal doctrine on its face. The others were based on assertions of gross inequality, which would have violated the standard in Plessy as well.

- Earl Warren (Author)

- Hugo Lafayette Black

- Stanley Forman Reed

- Felix Frankfurter

- William Orville Douglas

- Robert Houghwout Jackson

- Harold Hitz Burton

- Tom C. Clark

- Sherman Minton

Supreme Court opinions are rarely unanimous, and it appears that Justice Frankfurter deliberately argued for a re-hearing to stall the case while the Court built a consensus behind its decision. This was designed to prevent proponents of segregation from using dissents to build future challenges to Brown. Despite the eventual unanimity, the judges had a wide range of views. Reed and Clark were not opposed to segregation per se, while Frankfurter and Jackson were hesitant to issue a bold decision that might be difficult to enforce. (Jackson and Reed initially planned to write a dissent together.) Douglas, Black, Burton, and Minton were relatively ready to overturn Plessy from the outset, however, as was Chief Justice Warren. President Dwight D. Eisenhower's appointment of Warren to replace former Chief Justice Frederick Moore Vinson, who died in September 1953, thus may have played a crucial role in how events unfolded. Warren had supported the integration of Mexican-American children into California schools. Warren based much of his opinion on information from social science studies rather than court precedent. This was understandable because few decisions existed on which the Court could rely, yet it would draw criticism for its non-traditional approach. The decision also used language that was relatively accessible to non-lawyers because Warren felt that it was necessary for all Americans to understand its logic.

This decision ranks among the most dramatic issued by the Supreme Court, in part due to Warren's insistence that the Fourteenth Amendment gave the Court the power to end segregation even without Congressional authority. Like the use of non-legal sources to justify his reasoning, Warren's "activist" view of the Court's role remains controversial to the current day. The illegality of segregation does not, however, and a series of later decisions were implemented to try to force states to comply with Brown. Unfortunately, the reality is that this decision's vision of complete desegregation has not been achieved in many areas of the U.S., and the problems of enforcement that Jackson identified have proven difficult to solve.

U.S. Supreme Court

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka

Argued December 9, 1952

Reargued December 8, 1953

Decided May 17, 1954*

Segregation of white and Negro children in the public schools of a State solely on the basis of race, pursuant to state laws permitting or requiring such segregation, denies to Negro children the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment -- even though the physical facilities and other "tangible" factors of white and Negro schools may be equal. Pp. 486-496.

(a) The history of the Fourteenth Amendment is inconclusive as to its intended effect on public education. Pp. 489-490.

(b) The question presented in these cases must be determined not on the basis of conditions existing when the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted, but in the light of the full development of public education and its present place in American life throughout the Nation. Pp. 492-493.

(c) Where a State has undertaken to provide an opportunity for an education in its public schools, such an opportunity is a right which must be made available to all on equal terms. P. 493.

(d) Segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race deprives children of the minority group of equal educational opportunities, even though the physical facilities and other "tangible" factors may be equal. Pp. 493-494.

(e) The "separate but equal" doctrine adopted in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 , has no place in the field of public education. P. 495.

(f) The cases are restored to the docket for further argument on specified questions relating to the forms of the decrees. Pp. 495-496.

- Opinions & Dissents

- Copy Citation

Get free summaries of new US Supreme Court opinions delivered to your inbox!

- Bankruptcy Lawyers

- Business Lawyers

- Criminal Lawyers

- Employment Lawyers

- Estate Planning Lawyers

- Family Lawyers

- Personal Injury Lawyers

- Estate Planning

- Personal Injury

- Business Formation

- Business Operations

- Intellectual Property

- International Trade

- Real Estate

- Financial Aid

- Course Outlines

- Law Journals

- US Constitution

- Regulations

- Supreme Court

- Circuit Courts

- District Courts

- Dockets & Filings

- State Constitutions

- State Codes

- State Case Law

- Legal Blogs

- Business Forms

- Product Recalls

- Justia Connect Membership

- Justia Premium Placements

- Justia Elevate (SEO, Websites)

- Justia Amplify (PPC, GBP)

- Testimonials

Some case metadata and case summaries were written with the help of AI, which can produce inaccuracies. You should read the full case before relying on it for legal research purposes.

Brown v. Board of Education: 70 Years of Progress and Challenges

- Share article

After 70 years, what is left to say about Brown v. Board of Education ?

A lot, it turns out. As the anniversary nears this week for the U.S. Supreme Court’s historic May 17, 1954, decision that outlawed racial segregation in public schools, there are new books, reports, and academic conferences analyzing its impact and legacy.

Just last year, members of the current Supreme Court debated divergent interpretations of Brown as they weighed the use of race in higher education admissions, with numerous references to the landmark ruling in their deeply divided opinions in the case that ended college affirmative action as it had been practiced for half a century.

Meanwhile, some school district desegregation cases remain active after more than 50 years, while the Supreme Court has largely gotten out of the business of taking up the issue. There are fresh reports that the nation’s K-12 schools, which are much more racially and ethnically diverse than they were in the 1950s, are nonetheless experiencing resegregation .

At an April 4 conference at Columbia University, speakers captured the mood about a historic decision that slowly but steadily led to the desegregation of schools in much of the country but faced roadblocks and new conditions that have left its promise unfulfilled.

“I think Brown permeates nearly every aspect of our current modern society,” said Janai Nelson, the president and director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, the organization led by Thurgood Marshall, who would later become a Supreme Court justice, during the Brown era.

“I hope that we see clearly now that there is an effort to roll back [the] gains” brought by the decision, said Nelson, whose organization was a conference co-sponsor. “There is an effort to recast Brown from what it was originally intended to produce. If we want to keep this multiracial democracy and actually have it fulfill its promise, because the status quo is still not satisfactory, we must look at the original intent of this all-important case and make sure we fulfill its promise.”

Celebrations at the White House, the Justice Department, and a Smithsonian Museum

On May 16, President Joe Biden will welcome to the White House descendants of the original plaintiffs in the cases that were consolidated into Brown , which dealt with cases from Delaware, Kansas, South Carolina, and Virginia. (The companion decision, Bolling v. Sharpe , decided the same day, struck down school segregation in the District of Columbia.) On May 17, the president will deliver remarks on the historic decision at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Attorney General Merrick B. Garland and U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona marked the anniversary at an event at the U.S. Department of Justice on Tuesday.

“ Brown vs. Board and its legacy remind us who we want to be as a nation, a place that upholds values of justice and equity as its highest ideals,” Cardona said. “We normalize a culture of low expectations for some students and give them inadequate resources and support. Today, it’s still become all too normal for some to deny racism and segregation or ban books that teach Black history when we all know that Black history is American history.”

On May 17, 1954, then-Chief Justice Earl Warren announced the decision for a unanimous court that held that “in the field of public education, ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

That opinion was a compromise meant to bring about unanimity, and the court did not even address a desegregation remedy until a year later in Brown II , when it called for lower courts to address local conditions “with all deliberate speed.”

“In short, the standard the court established for evaluating schools’ desegregation efforts was as vague as the schedule for achieving it was amorphous,” R. Shep Melnick, a professor of American politics at Boston College and the co-chair of the Harvard Program on Constitutional Government, says in an assessment of the Brown anniversary published this month by the American Enterprise Institute.

The paper distills a book by Melnick published last year, The Crucible of Desegregation: The Uncertain Search for Educational Equity , which takes a fresh look at the 70-year history of post-Brown desegregation efforts.

Melnick argues that even after 70 years, Brown and later Supreme Court decisions remain full of ambiguities as to even what it means for a school system to be desegregated. He highlights two competing interpretations of Brown embraced by lawyers, judges, and scholars—a “colorblind” approach prohibiting any categorization of students by race, and a perspective based on racial isolation and equal educational opportunity. “Neither was ever fully endorsed or rejected by the Supreme Court,” Melnick writes in the book. “Both could find some support in the court’s ambiguous 1954 opinion.”

The Supreme Court issued some 35 decisions on desegregation after Brown , but hasn’t taken up a case involving a court-ordered desegregation remedy since 1995 and last spoke on the issue of integration and student diversity in the K-12 context in 2007, when the court struck down two voluntary plans to increase diversity by considering race in assigning students to schools.

Citations to Brown pervade last year’s sharply divided opinions over affirmative action

Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr., in his plurality opinion in that voluntary integration case, Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District , laid the groundwork for last year’s affirmative action decision, which fully embraced Brown’s “race-blind” interpretation.

Last term, the high court ruled that race-conscious admissions plans at Harvard and the University of North Carolina violated the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause. (The vote was 6-2 in Students for Fair Admissions v. President and Fellows of Harvard College , with Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson not participating because of her recent membership on a Harvard governing board. The vote was 6-3 in SFFA v. University of North Carolina .)

The Brown decision was a running theme in the arguments in the case, and in the some 230 pages of opinions.

Roberts, in the majority opinion, said a fundamental lesson of Brown in 1954 and Brown II in 1955 was that “The time for making distinctions based on race had passed.”

Brown and a generation of high court decisions on race that followed, in education and other areas, “reflect the core purpose of the Equal Protection Clause: doing away with all governmentally imposed discrimination based on race,” the chief justice wrote.

Justice Clarence Thomas, who succeeded Thurgood Marshall, joined the majority opinion and wrote a lengthy concurrence that touched on views he had long expressed about the 1954 decision. He cited the language of legal briefs filed by the challengers of segregated schools in the Brown cases (led by Marshall) that embraced the view that the 14th Amendment barred all government consideration of race.

Thomas said those challenging segregated schools in Brown “embraced the equality principle.”

Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh also joined the majority and acknowledged in his concurrence that in Brown , the court “authorized race-based student assignments for several decades—but not indefinitely into the future.”

(The other justices in the majority were Samuel A. Alito Jr., Neil M. Gorsuch, and Amy Coney Barrett.)

Writing the main dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor rejected the view that Brown was race-blind.

“ Brown was a race-conscious decision that emphasized the importance of education in our society,” she wrote, joined by justices Elena Kagan and Jackson. “The desegregation cases that followed Brown confirm that the ultimate goal of that seminal decision was to achieve a system of integrated schools that ensured racial equality of opportunity, not to impose a formalistic rule of race-blindness.”

Jackson, in a separate dissent (joined by Sotomayor and Kagan), said, “The majority and concurring opinions rehearse this court’s idealistic vision of racial equality, from Brown forward, with appropriate lament for past indiscretions. But the race-linked gaps that the law (aided by this court) previously founded and fostered—which indisputably define our present reality— are strangely absent and do not seem to matter.”

Amid reports on resegregation, some legal efforts continue

As the Brown anniversary arrives, there are fresh reports about resegregation of the schools. Research released this month by Sean Reardon of Stanford University and Ann Owens of the University of Southern California found that students in the nation’s large school districts have become much more isolated racially and economically in recent years.

The Civil Rights Project at the University of California, Los Angeles, which has been sounding the alarm about resegregation for years, says in a new report that Black and Latino students were the most highly segregated demographic groups in 2021. Though U.S. schools were 45 percent white, Blacks, on average, attended 76 percent nonwhite schools, and Latino students went to 75 percent nonwhite schools.

The CRP says the Brown anniversary is worth celebrating, but “American schools have been moving away from the goal of Brown and creating more ‘inherently unequal’ schools for a third of a century. We need new thought about how inequality and integration work in institutions and communities with changing multiracial populations with very unequal experiences.”

At the Columbia conference, Samuel Spital, the litigation director and general counsel of the Legal Defense Fund, noted that many jurisdictions are still under desegregation orders, some going back decades.

He highlighted one where LDF lawyers have been in federal district court, involving the 7,200-student St. Martin Parish school district in western Louisiana. Black plaintiffs first sued over segregated schools in 1965. In a 2022 decision, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit, in New Orleans, noted that the case had been pending for “five decades,” though largely inactive for long stretches. The court nonetheless affirmed the district court’s continued supervision of a desegregation plan that addressed disparities in graduation tracks and student discipline, though it said the court overstepped in ordering the closure of an elementary school in a mostly white community.

As recently as this month, the LDF and the Department of Justice’s civil rights division joined with the St. Martin Parish school board in a proposed consent order for revised attendance zones for the district’s schools. The proposed order suggests that court supervision of student assignments could end sometime after June 2027.

“We try to make sure that with the vast docket of segregation cases we have, that we have not lost sight of what Brown’s ultimate intent was,” said LDF’s Nelson, which was not just “to make sure that Black and white children learn together” but also to foster principles of equity and citizenship.

With a hostile federal court climate, advocates more recently have turned to state constitutions and state courts to pursue desegregation. Last year, a state judge in New Jersey allowed key claims to proceed in a lawsuit that seeks to hold the state responsible for remedying racial segregation in its many “racially isolated” public schools. In December, the Minnesota Supreme Court allowed a suit under the state constitution to move forward, ruling that there was no need for plaintiffs to prove that the state itself had caused segregation in its schools.

“We see a path forward through state courts with the very specific goal of trying to challenge state practices, which really boil down to segregative school district lines,” Saba Bireda, the chief legal counsel of Brown’s Promise , said at the Columbia conference. Bireda, a former civil rights lawyer in the Education Department under President Barack Obama’s administration, co-founded the Washington-based organization last year to help address diversity and underfunding in public schools.

A Supreme Court exhibit offers the idealized take on Brown

At the Supreme Court, there has been no formal recognition of the 70th anniversary of Brown . But the court did open an exhibit on its ground floor late last year that tells the story of some of the first desegregation cases, including Brown .

The exhibit is primarily about the Little Rock integration crisis of 1957, when Arkansas Gov. Orval Faubus defied a federal judge’s order to desegregate Central High School. The exhibit is built around the actual bench used by Judge Ronald N. Davies when he heard a challenge to Faubus’ use of the Arkansas National Guard to prevent the nine Black high school students from entering the all-white high school that year. (Davies withstood threats and intense opposition from desegregation opponents, but he ruled for the Black students. The Supreme Court itself supported desegregation in Little Rock with its 1958 decision in Cooper v. Aaron .)

To tell the Little Rock story, the exhibit starts with Brown (and some of the prior history). A central feature is a 15-minute video featuring all current members of the court.

In the video, the justices set aside their differences over the meaning of Brown and provide a more idealized perspective on the 1954 decision.

“ Brown was a godsend,” Thomas says in the video. “Because it said that what was happening that we thought was wrong, they now know that this court said it was also wrong. It’s wrong not just morally, but under the Constitution of the United States. It was like a ray of hope.”

Kavanaugh says: “ Brown vs. Board of Education is the single greatest moment, single greatest decision in this court’s history. And the reason for that is that it enforced a constitutional principle, equal protection of the laws, equal justice under law. It made that real for all Americans. And it corrected a grave wrong, the separate but equal doctrine that the court had previously allowed.”

Jackson, the court’s third Black justice, who has spoken of her family moving in one generation from “segregation to the Supreme Court,” reflects in the video on Brown ‘s legacy.

“I think I’m most grateful for the fact that my parents have lived to see me in this position, after a history of them and others in our family and people from my background not having the opportunity to live to our fullest potential,” she says.

As the video comes to a close, Roberts speaks with evident pride in his voice.

“The Supreme Court building stands as a symbol of our country’s faith in the rule of law,” the chief justice says. “ Brown v. Board of Education , the great school desegregation case, was decided here.”

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Brown v. Board of Education

By: History.com Editors

Updated: February 27, 2024 | Original: October 27, 2009

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka was a landmark 1954 Supreme Court case in which the justices ruled unanimously that racial segregation of children in public schools was unconstitutional. Brown v. Board of Education was one of the cornerstones of the civil rights movement, and helped establish the precedent that “separate-but-equal” education and other services were not, in fact, equal at all.

Separate But Equal Doctrine

In 1896, the Supreme Court ruled in Plessy v. Ferguson that racially segregated public facilities were legal, so long as the facilities for Black people and whites were equal.

The ruling constitutionally sanctioned laws barring African Americans from sharing the same buses, schools and other public facilities as whites—known as “Jim Crow” laws —and established the “separate but equal” doctrine that would stand for the next six decades.

But by the early 1950s, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People ( NAACP ) was working hard to challenge segregation laws in public schools, and had filed lawsuits on behalf of plaintiffs in states such as South Carolina, Virginia and Delaware.

In the case that would become most famous, a plaintiff named Oliver Brown filed a class-action suit against the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, in 1951, after his daughter, Linda Brown , was denied entrance to Topeka’s all-white elementary schools.

In his lawsuit, Brown claimed that schools for Black children were not equal to the white schools, and that segregation violated the so-called “equal protection clause” of the 14th Amendment , which holds that no state can “deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

The case went before the U.S. District Court in Kansas, which agreed that public school segregation had a “detrimental effect upon the colored children” and contributed to “a sense of inferiority,” but still upheld the “separate but equal” doctrine.

Brown v. Board of Education Verdict

When Brown’s case and four other cases related to school segregation first came before the Supreme Court in 1952, the Court combined them into a single case under the name Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka .

Thurgood Marshall , the head of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, served as chief attorney for the plaintiffs. (Thirteen years later, President Lyndon B. Johnson would appoint Marshall as the first Black Supreme Court justice.)

At first, the justices were divided on how to rule on school segregation, with Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson holding the opinion that the Plessy verdict should stand. But in September 1953, before Brown v. Board of Education was to be heard, Vinson died, and President Dwight D. Eisenhower replaced him with Earl Warren , then governor of California .

Displaying considerable political skill and determination, the new chief justice succeeded in engineering a unanimous verdict against school segregation the following year.

In the decision, issued on May 17, 1954, Warren wrote that “in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place,” as segregated schools are “inherently unequal.” As a result, the Court ruled that the plaintiffs were being “deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the 14th Amendment.”

Little Rock Nine

In its verdict, the Supreme Court did not specify how exactly schools should be integrated, but asked for further arguments about it.

In May 1955, the Court issued a second opinion in the case (known as Brown v. Board of Education II ), which remanded future desegregation cases to lower federal courts and directed district courts and school boards to proceed with desegregation “with all deliberate speed.”

Though well intentioned, the Court’s actions effectively opened the door to local judicial and political evasion of desegregation. While Kansas and some other states acted in accordance with the verdict, many school and local officials in the South defied it.

In one major example, Governor Orval Faubus of Arkansas called out the state National Guard to prevent Black students from attending high school in Little Rock in 1957. After a tense standoff, President Eisenhower deployed federal troops, and nine students—known as the “ Little Rock Nine ”— were able to enter Central High School under armed guard.

Impact of Brown v. Board of Education

Though the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board didn’t achieve school desegregation on its own, the ruling (and the steadfast resistance to it across the South) fueled the nascent civil rights movement in the United States.

In 1955, a year after the Brown v. Board of Education decision, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery, Alabama bus. Her arrest sparked the Montgomery bus boycott and would lead to other boycotts, sit-ins and demonstrations (many of them led by Martin Luther King Jr .), in a movement that would eventually lead to the toppling of Jim Crow laws across the South.

Passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 , backed by enforcement by the Justice Department, began the process of desegregation in earnest. This landmark piece of civil rights legislation was followed by the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Fair Housing Act of 1968 .

Runyon v. McCrary Extends Policy to Private Schools

In 1976, the Supreme Court issued another landmark decision in Runyon v. McCrary , ruling that even private, nonsectarian schools that denied admission to students on the basis of race violated federal civil rights laws.

By overturning the “separate but equal” doctrine, the Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education had set the legal precedent that would be used to overturn laws enforcing segregation in other public facilities. But despite its undoubted impact, the historic verdict fell short of achieving its primary mission of integrating the nation’s public schools.

Today, more than 60 years after Brown v. Board of Education , the debate continues over how to combat racial inequalities in the nation’s school system, largely based on residential patterns and differences in resources between schools in wealthier and economically disadvantaged districts across the country.

HISTORY Vault: Black History

Watch acclaimed Black History documentaries on HISTORY Vault.

History – Brown v. Board of Education Re-enactment, United States Courts . Brown v. Board of Education, The Civil Rights Movement: Volume I (Salem Press). Cass Sunstein, “Did Brown Matter?” The New Yorker , May 3, 2004. Brown v. Board of Education, PBS.org . Richard Rothstein, Brown v. Board at 60, Economic Policy Institute , April 17, 2014.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

You are using an outdated browser no longer supported by Oyez. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Winter 2024

Brown v. Board of Education

Fifty years later, NAACP lawyer Jack Greenberg reflects on Brown v. Board of Education: “Brown went beyond school integration, raising a legal and moral imperative that was influential even when it was not obeyed.”

In summer 2003, I consulted with lawyers and nongovernmental organizations in Budapest, Sofia, and small towns in Bulgaria on integrating Roma (Gypsy) children into the public schools. They taught me more than I taught them. Just as learning another language helps one understand English better, Brown v. Board of Education , took on new meaning for me as I observed integration of Roma into Bulgarian public schools.

Ninety percent of Europe’s Roma population of seven to nine million is settled in Eastern Europe. Once nomadic, they are mainly “sedentary,” as a consequence of fifty years of communist rule that prohibited their traditional traveling. They remain subject to centuries-old discrimination in employment, housing, health care, municipal services, political participation, the criminal justice system, and other aspects of living. Often they are victims of ethnic violence. In the Czech Republic, for example, since 1991 there have been documented killings of nine Roma from among over a thousand racially motivated acts of violence. European Union law now prohibits racial and ethnic discrimination. East European countries as condition of admission to the EU must meet its standards, but the process of coming into compliance has just begun. This article focuses only on the decision to end school segregation and the process being followed in some places in bringing it to an end.

Beginning in 2000, and expanding in scope in 2001-2002, Bulgaria integrated 2,400 Roma schoolchildren into the majority school population, often referred to as “whites,” in six cities. Roma integration, which will cover all of Eastern Europe, was smooth and successful at its beginning and shows no indication of replicating the American South’s response to Brown . In the United States, integration was angry, often violent, and almost nonexistent for more than a decade and a half after 1954, when Brown was decided. A start, even as small as Bulgaria’s, almost anywhere in the South around 1954, would have met vigorous opposition.

What occurred in Bulgaria has been a beginning only, and was the product of private initiative, with indispensable government collaboration and approval. Although in most of Eastern Europe there has been a slow movement, even inertia, with regard to desegregation, there has been nothing like the massive resistance that obstructed desegregation in the United States. The Bulgarian government, committed to complete desegregation, has not yet appropriated funds to carry it out, although it has promised that it will. The European Roma Rights Center reports that only Hungary so far has initiated a governmental program. It offers financial incentives to schools that integrate Roma children. Hungary has appointed an energetic Commissioner for Integration of Roma and Disadvantaged children, Victoria Mohacsi, whom I met in Budapest during my visit. I have no doubt that she is committed to succeed. As of the latest report, four hundred schools have joined its program. But, as late as the beginning of July 2004, Roma leadership claimed that integration is not fast enough on any front (education, social life, economics) and that poor education continues to plague their community. The ultimate accomplishment of the program is yet to be seen.

Comparing Cases

Some 70 percent of Roma children are segregated in separate schools, separate classrooms, or, following usually erroneous diagnoses, in separate rooms for the handicapped. Only 5 percent graduate from secondary school; fourth-graders commonly are illiterate; only .3 percent show interest in taking national exams for admission to elite schools after seventh or eighth grade; in Bulgaria, more than half of Roma school windows are covered by cardboard, a situation probably representative of other countries in the region.

The U.S. Constitution, East European domestic constitutions, and the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights embody pretty much the same rights. Notwithstanding constitutions and laws, the United States and Europe, respectively, tolerated subordination of African Americans and Roma. Despite much successful school desegregation in the United States, defiance and evasion accompanied the process from the beginning. In contrast, at the outset, six towns in Bulgaria had desegregated not long before I visited, all uneventfully, some highly successfully. As time goes on, desegregation of Roma may become more difficult, but there will be no “massive resistance,” which was the response of the American South.

In 2000, the European Union adopted the Race Equality Directive, pursuant to which schools must desegregate. The directive had roots in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, international covenants and conventions, and the European Convention on Human Rights. In order to join the EU, East European countries must comply with the directive, which requires that member states achieve racial equality. There were no attacks on its legitimacy in the same way that there were attacks on the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education . Given the geopolitics of EU enlargement, political leaders are too committed to the process to generate opposition to EU standards. Before the Race Equality Directive was promulgated, Bulgaria enacted a “Framework Program” to implement the then forthcoming directive.

There is also a practical consideration: Eastern Europe’s population is falling because of low birth rate and emigration, but Roma population is not. Schools are funded on a per capita basis. Teachers and administrators in the white schools welcome the income new Roma students provide. Indeed, the main source of opposition to desegregation, weak as it is, comes from the non-Roma teachers and administrators in Roma schools, because they will lose funding. The only other reservations I have heard about integration is that some Roma families feared that white schoolchildren would introduce their children to drugs. I have also heard passing mention of a desire to maintain cultural identity.

The integrated Bulgarian public schools suggest what is possible in Eastern Europe. In this case, integration was administered and funded by a private foundation and supported by NGO networks, financier and philanthropist George Soros, and the World Bank, but the schools were public, and the integration was an expression of public policy. I visited two of the desegregated towns, Montana and Vidin. In Vidin, I attended a meeting of three to four hundred parents, pupils, teachers, and administrators, Roma and non-Roma, who were overwhelmingly in favor of desegregation. For perhaps three hours one person after another stood up and spoke about the success of desegregation. I think that only one speaker disapproved. One of my hosts was particularly proud that a Romany boy who was attending a desegregated school had been rated number two in the national mathematics examination. Such a meeting would have been inconceivable anywhere in the South in 1954. Although I thought of Potemkin villages and Soviet demands for conformity, I believe that I heard statements of genuine belief.

Even more striking was the community effort to provide social supports. Social workers visited every Romany family that had school-age children. Tutors were available for children who needed help. Teachers received special training. Families that needed food or clothing received assistance. Roma and non-Roma children shared outings, social events, and cultural experiences. The project has received major political support. The press publicized the advantages of integration.

There probably are additional reasons that contributed to reactions different from those in the United States. Roma children travel to integrated schools by bus, but white children are not bussed to Roma neighborhoods. In the United States, school desegregation was begun in a similar way. Black families soon objected that they had to travel to white schools, while whites did not have to travel to black schools. Black and white children should be treated the same, they argued. Moreover, it was insulting to black teachers and administrators to designate black schools as off-limits to whites, giving rise to two-way busing, uncongenial for many white families. But two-way busing is not in the cards for East Europeans. They believe that the Roma schools, often one- and two-room buildings accommodating many more grades, are so dilapidated that neither Roma nor whites would want to occupy them in the future.

There has, however, been lack of movement, along with some anticipatory efforts to evade the law. The Budapest-based European Roma Rights Center has cases before domestic and international courts challenging school segregation in the Czech Republic; Croatia; and Sofia, Bulgaria. Egregious anti-Roma activity occurs, although it has not been linked to the expected school transition. In the 1990s, there were assaults against Roma in Romania. Vigilantes burned Roma houses in Bulgaria, some with the residents inside. Children were badly burned. In the Czech Republic, one town built a wall around a Roma ghetto. Skinheads have attacked Roma in Hungary and other Central European countries. Nevertheless, I have not seen anything connected to school integration in Eastern Europe resembling commonplace reactions during a comparable period in the American South.

After Hungary committed to phasing out all seven hundred Roma classes in the country within the next five years, Jaszladay, fifty-six miles south of Budapest, established a private school in a city building, subvented by the municipal government, resembling the “seg academies” that sprang up in the southern United States following Brown . Forty percent of the Jaszladay population, but only 17 percent of the private school’s students, were Roma. The Hungarian national ombudsman for minority rights announced that such schools will be closed. In the American South, politics and legal obstacles protected private white schools for years, although in time, lawsuits cut back some subsidies such as free books, and blacks eventually won the theoretical right to attend.

Desegregation in the United States

In April 2001, the president of Bulgaria congratulated the organization that sponsored the desegregation. In contrast, President Dwight D. Eisenhower disagreed with Brown and said only that the law should be obeyed. A South-wide policy of “massive resistance” launched resolutions of interposition and nullification and created well-funded state sovereignty commissions devoted to preventing desegregation. State supreme court judges, state attorneys general, even federal judges, denounced the Supreme Court. States prosecuted civil rights organizations and tried to disbar civil rights lawyers, enacted legislation that would close integrated schools, and created complex administrative procedures to block access to non-segregated education.

Distinguished scholars attacked the Brown opinion, lending credibility to cruder critics. Legal luminaries such as Learned Hand and esteemed scholars such as Herbert Wechsler, who personally opposed segregation, delegitimized the Brown decision

That the South would ignore and even disobey court orders to cease discriminating did not surprise plaintiffs’ lawyers in Brown . No one, however, anticipated the intensity of the opposition. Civil rights litigation had until then produced many paper victories. Courts had ordered universities to admit blacks, interstate buses and railroads to stop segregating, voting officials to cease prohibiting black voting, jury commissioners to cease excluding blacks from pools of jurors, courts to cease enforcing agreements among property owners not to sell to blacks. These decisions produced only slight changes.

Southern officials and institutions typically treated a court decision as if it applied only to the plaintiff and defendant in that case. Bus companies did not act as if a Supreme Court decision about seating on the bus controlled terminals. One bus company did not treat a decision directed at another as relevant to its own situation. Railroad companies did not treat a decision governing sleeping or dining cars as applicable to coaches, or a decision affecting one company as applicable to another. Voting officials outright evaded court orders that invalidated laws or practices that excluded blacks by adopting fresh registration or voting criteria that once again shut them out. One case after another overturned convictions because blacks had been excluded from juries, but exclusion continued. Prosecutors assumed that lawyers in the next case might not know or care to raise the issue.

Decisions that required admitting blacks to higher education prefigured the reaction that would occur at the elementary and high school level. Despite Supreme Court decisions beginning in 1935 it was virtually impossible for more than a small handful of blacks, without first filing a lawsuit, to attend an accredited law, medical, or other professional school or get a Ph.D. in the South until the 1960s. In 1939, the Supreme Court, in Missouri ex rel . Gaines v. Canada ordered the University of Missouri to admit a black applicant to its law school because Missouri had no law school for blacks. A subsequent case had to be filed to secure admission of blacks to the Missouri School of Journalism.

In 1948, the U.S. Supreme Court required that the University of Oklahoma admit a black woman to its law school. Immediately thereafter, the Oklahoma Graduate School of Education rejected an applicant because he was black. The University of Texas Law School rejected a black plaintiff and set up a two-room law school for him. The Supreme Court ordered that the Oklahoma and Texas plaintiffs be admitted in 1950.

In the 1960s, courts ordered the University of Alabama, the University of Georgia, and the University of Mississippi to admit blacks, enforced by troops at the campus. Indeed, before blacks were admitted, suits had to be filed in every single southern state with the exception of Arkansas. I participated in suits against universities in Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, Tennessee, Texas, and other states.

Was there some way that the attack on segregation could have been directed so that American integration would have unfolded as (so far) smoothly as Roma integration in Bulgaria? Might it have been better initially to direct efforts at housing, employment, or public accommodations? Two obstacles discouraged such an alternative approach. First, the state action doctrine; second, whether a legal right to integrate those options could translate into genuine social change.

The state action doctrine pronounced in the Civil Rights Cases of 1883 held that the Fourteenth Amendment prohibited discrimination only by the state, not private persons. It used the term “state” in a very narrow sense. Because the overwhelming part of housing, employment, and public accommodations was private in a constitutional sense, the state action doctrine would have been an insurmountable barrier. Second, even suits against state-owned or state-operated employment, housing, and public accommodations would be limited in what they could accomplish. Housing units are discrete. To move into a white neighborhood as the first black is a daunting prospect. Government jobs were virtually impossible to obtain, even with successful litigation. Too much discretion in selection was involved. Jobs are different from one another; wholesale litigation was unlikely to change very much very soon. And, in any event, only a small handful of jobs would be in play. There was an infinitesimally small number of government-owned public theaters, golf courses, and other places of amusement and entertainment. No suit could have the impact that desegregating a school district would produce.

Some considered, and some still urge, enforcing the “equal” part of the “separate-but-equal” formula, rather than seeking integration. But, if a case were won, there was the problem of compelling legislatures to tax and appropriate court-ordered funding; if that succeeded, it would be necessary to sue again as black schools slid back into physical inequality. Out of that recognition, Nathan Margold, who drafted the policy paper that launched the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People’s desegregation campaign, argued for striking at the “heart of the evil,” segregation. Brown historical revisionists who now argue that separate-but-equal is better than integration forget that separate-but-equal was prevailing law between 1896 and 1954 and that there had been much effort to enforce it. Equality never was achieved. Lack of success contributed to launching the attack on segregation. The experience with equal funding attempts has been replicated in about twenty state supreme court opinions of recent years that have required equalizing funds of rich and poor districts, or at least raising funds of poor districts to levels of adequacy. In few instances have such suits achieved equality. In New Jersey there was little enhancement of minority schools for thirty years. Now, that thirty-year-old case has increased funding for a few lower grades. Equal-funding litigation confirms the aphorism that “green follows white.”

Thurgood Marshall, chief counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, said that he thought that, in Georgia, we would have to sue the schools for integration in every county. The rest of the South, with spotty exceptions, would be no easier. But he and we expected hostility, not near insurrection.

Why Politics Couldn’t Work

Although the NAACP was a political organization, it could not even persuade Congress to enact an anti-lynching bill. Franklin Roosevelt did not fight for one because, if he had, Southern senators would not have supported his efforts to overcome the depression or support the Allies before the United States entered World War II. Unless blacks could vote, politics would be hopeless. It should have been easy to gain the vote: legal rules, from the Constitution on down prohibiting voting discrimination abounded. When the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was enacted, only about 8 percent of blacks in the one hundred counties with the most black population could vote. In the deep South, blacks voted at the rate of about 2 percent. Without the vote, the political route was illusory.

Courtroom action seemed to be the only viable option. But, why go to court after having experienced such resistance to judicial decrees and recognizing the limits on what they had achieved? There was no place else to go. It was like seeking the way out of a maze: when one path turned out to be unpromising, try another. Attacking school segregation in court was the only effort that appeared to be worth the trouble.

The School Desegregation Decisions

We won Brown . But almost nothing happened with schools. The South threw up a wall of massive resistance described above. Finally, in 1969, after a decade and a half of marginally effective lawsuits, in Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education , the Supreme Court struck down all of the school board defendants’ tactical ploys that had amounted to “litigation forever.” School desegregation began in earnest. Southern schools changed from almost no black students in majority southern white schools in 1954, with the proportion of black students jumping to 33.1 percent in 1970 and to 43.5 percent by 1988. Then a retreat set in, which continues to this day. The rate was 32.7 percent in 1998. This article is not the place to account for the decline. Suffice to say that maintaining desegregation was difficult in the face of newly fashioned legal doctrines prohibiting court orders for city-to-suburb desegregation and demographic changes that packed urban centers with minorities.

But something else happened. Opponents of Brown were right in claiming that victory for plaintiffs would spell doom for segregation in all its manifestations. First, Brown went beyond school integration, raising a legal and moral imperative that was influential even when it was not generally obeyed. It set a standard of right conduct. Some laws are widely disobeyed or in disrepute or subject to conflicting views. But Brown was not merely a pronouncement by the Court. As the brief for the United States on implementation stated, “The right of children not to be segregated because of race or color is not a technical legal right of little significance or value. It is a fundamental human right, supported by considerations of morality as well as law.” Or, as the United States argued in another brief: “It is in the context of the present world struggle between freedom and tyranny that the problem of racial discrimination must be viewed. The United States is trying to prove to the people of the world, of every nationality, race, and color, that a free democracy is the most civilized and most secure form of government yet devised by man.”

The arguments of those who wanted to maintain segregation did not involve claims about right and wrong. They were couched in terms of federalism, local control, original intent of the Constitution, the sanctity of precedent, the role of the judiciary in a democracy, the difficulty of compliance, or the academic inadequacy of blacks. In briefs on the question of implementing desegregation decrees, states argued “unfavorable community attitude,” “health and morals” of the black population, that local school boards were “unalterably opposed,” and the like. North Carolina argued that integration would create the “likelihood of violence,” and that “[p]ublic schools may be abolished.” Oklahoma urged that desegregation would create “financial problems.” Florida argued that almost 2 percent of white births in Florida and 24 percent of Negro births were “illegitimate.” Florida reported over eleven thousand cases of gonorrhea, of which ten thousand were among the Negro population. There were some claims that the Bible intended the races to be separate. I have scoured the briefs of defendants and have reviewed the public debates. There were no claims that segregation was right and moral.

Second, enforcing Brown established national, not regional, standards as the measure of equality. Efforts at school desegregation were opposed by a steady drumbeat of physical resistance that, in turn, was almost always overcome by superior police and military force. In border states-Milford, Delaware; Clay and Sturgis, Kentucky; Clinton, Tennessee; and Greenbrier County, West Virginia-violent public demonstrations against desegregation were suppressed or contained by police, troops, and the National Guard. In 1957, in Little Rock, Arkansas, the president summoned the armed forces to assure black children’s entry to Little Rock High School. Another president summoned troops to secure admission of James Meredith to the University of Mississippi and Vivian Malone and James Hood to the University of Alabama in the early 1960s. Ultimately, national rule established its superiority by physical force over physical resistance.

Third, a people’s movement embraced Brown . It was as if there were an immune reaction to massive resistance. Leaders of the first sit-ins in 1960 had been inspired by Brown . Freedom Rides began in 1961, partly in homage to Brown , with the first ride scheduled to arrive in New Orleans on May 17, 1961, its anniversary. Martin Luther King, Jr., annually held prayer pilgrimages on May 17 and often invoked the Supreme Court. Rosa Parks, whose act of defiance launched the Montgomery bus boycott, was an NAACP administrator steeped in Brown . The boycott was resolved by Gayle v. Browder, in which the Supreme Court, citing Brown , held unconstitutional the segregation law that was the subject of the boycott.

Symbolic defiance of segregation was not new. The black press had run stories about sit-ins and sitting in prohibited sections of buses and so forth as far back as the 1930s. But, for the first time network television inspired emulation everywhere.

Together, the moral imperative of Brown , the physical suppression of resistance, the civil rights movement, and the defeat of massive resistance culminated in the civil rights acts of the 1960s. Those acts marked the beginning of a political transformation of the United States. It has been manifested in numerous ways, but epitomized in the election of forty black congressional representatives and of black mayors at one time or another in every major American city and most smaller ones. When Lyndon Johnson signed the 1964 civil rights bill he observed that it meant the end of the Democratic Party in the South. He was right. But it meant the end, also, of southern racist hegemony and associated political programs.

We may conceive of the political situation in the United States in the mid-twentieth century as frozen until 1954. Southern white racists kept blacks in subordinate caste-like status. The school integration decision, if a metaphor may be permitted, acted like a powerful icebreaker. It made America accept racial change. Brown was not merely a school case. Supreme Court Justice Robert H. Jackson used this image in describing the path-breaking role of the Nuremberg trials. He told his staff that they had to produce “an ice pick to break up the frozen sea within us.” Kafka scholar Stanley Corngold has suggested that Jackson may have found the metaphor in Kafka, who wrote that “a book must be the axe for the frozen sea within us.”

Like my metaphorical icebreaker or Kafka’s metaphorical axe, Brown created pathways over which America could arrive at racial change. Brown was not merely a school case.

So, when I saw smooth, easy, agreeable, successful school desegregation in Bulgaria and wondered why Brown had not gone so smoothly in the United States, the answer is that Brown , while a school case, was doing more in different circumstances. Schools could not desegregate in the racially hostile atmosphere of the South in the 1950s and even later than that. There was no way to effect change in the face of opposition with vested interests in the status quo. Brown was a first step in cracking open that frozen sea by changing and energizing minds, creating a social movement that became political, enlisting parts of the country and the world, and enacting basic laws that affected power relationships between black and white, North and South.

Then South Carolina or Mississippi could receive our version of the Race Equality Directive and respond like Vidin.

Jack Greenberg has been professor of law at Columbia University since 1984. He served as assistant counsel, NAACP Legal Defense Fund, from 1949-1961, as director-counsel from 1961-1984, and was among the lawyers who argued Brown v. Board of Education . He is the author of Crusaders in the Courts: Legal Battles of the Civil Rights Movement . This article is adapted from another piece on the same subject that appeared in the Spring 2004 Saint Louis University Law Journal.

Download the full article as a PDF