- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Clothing and Textiles Research Journal

Preview this book.

- Description

- Aims and Scope

- Editorial Board

- Abstracting / Indexing

- Submission Guidelines

Clothing and Textiles Research Journal (CTRJ) aims to be the journal of choice among scholars studying clothing, textiles, and related topics across the discipline. The journal publishes impactful scholarship that shapes the discipline. As the official journal of International Textile and Apparel Association Inc, it is peer-reviewed and is published quarterly. CTRJ publishes articles in the following areas:

- Textile science

- Apparel science and technology

- Consumer behavior

- Social psychology

- History and culture

- Merchandising and retailing

- Textile and apparel industry

- Education and pedagogy

Clothing & Textiles Research Journal is the official publication of the International Textile & Apparel Association, Inc. (ITAA, www.itaaonline.org ). The ITAA is a professional, educational association composed of scholars, educators, and students in the textile, apparel, and merchandising disciplines in higher education. This journal is a member of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) .

CTRJ invites high-quality manuscripts relevant to the CTRJ audience by demonstrating originality, strong theoretical/conceptual foundation, appropriate methods/approaches, significant results/outcomes, and valuable implications. Please refer to the following description for each track.

Clothing and Textiles Research Journal (CTRJ) aims to be the journal of choice among scholars studying clothing, textiles, and related topics across the discipline. The journal publishes impactful scholarship that shapes the discipline. As the official journal of International Textile and Apparel Association Inc (ITAA), it is peer-reviewed and is published quarterly. The CTRJ home page is found at https://journals.sagepub.com/home/ctr

- America: History and Life

- Clarivate Analytics: Current Contents - Physical, Chemical & Earth Sciences

- Elsevier: Engineering Village

- Family Scholar

- Journal Citation Reports/Social Sciences Edition

- Psychological Abstracts

- Social Sciences Citation Index (Web of Science)

- Textile Technology Index

- VINITI Abstracts Journal

- World Textile Abstracts

HOW TO SUBMIT A NEW MANUSCRIPT VIA THE CTRJ PORTAL

Create an account.

Log into the following web address: http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/ctrj . Unless you have an account already, the first step will be to set up an author account for the contact author. Click on "Create Account: New Users Click Here" and follow the directions. Your log-in ID is your e-mail address. If you have accessed the system previously but do not know your password, click on "Forgot password" and the system will send you a temporary password to enter the system. Once in the system, you will be prompted to set up a permanent password of your own choosing.

Please be aware that as you set up your account, certain information is required and you will not be able to proceed with a manuscript submission until the required information is complete. One such requirement is the selection of key words which is intended to identify your areas of expertise; it is not at this point associated with a particular manuscript. Likewise, you are asked as an author to indicate if you have expertise in quantitative, qualitative or both types of research. Again, this is not particular to a given manuscript but to your general expertise. If you become published through CTRJ , this information may be used in considering you as a reviewer of manuscripts.

Prepare Your Manuscript for Online Submission

Before a paper is submitted, please note the information below and adjust your manuscript accordingly. Be sure to complete this process because the following guidelines are used to screen all manuscripts, and these guidelines must be met for the manuscript to be sent out for review.

Manuscript Preparation

Manuscripts should be prepared using the APA style manual (7th Edition, Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association ). All of the manuscript must:

- Be double-spaced (including references, footnotes, endnote, block quotes, tables and figures of the manuscript).

- Use Times New Roman, font size 12 for all of the text in the manuscript, headings, figures, and tables.

- Use left only justification.

- Indent at the beginning of each paragraph by one-half inch.

- Not add extra line spaces between paragraphs.

- Use 1 inch margins on all four sides.

- Not number the pages.

- Use continuous line numbering on the main manuscript pages.

Our review procedures follow the double anonymize practice and thus do not include your name on the abstract, manuscript, or have any self-identifying information within the manuscript. Your manuscript will not be sent out for review if there is any identifying information on the manuscript, abstract, tables, or figures.

The main manuscript document should include two major sections (in this order): Main Body and References. This will be uploaded as the "main document." Other sections such as tables and figures are uploaded separately from the main document.

Sections in a manuscript may include the following (in this order): (1) Title page, (2) Abstract and Keywords, (3) Text, (4) Notes, (5) References, (6) Tables, (7) Figures, (8) Appendices, and (9) Biography.

1. Title page. Upload as title page. Please include the following:

- Full article title

- Acknowledgments and credits

- Each author’s complete name and institutional affiliation(s), address, phone/fax, and email

- Grant numbers and/or funding information

- Corresponding author should be noted

2. Abstract and Keywords. Note: The abstract (150 words) is submitted separately from the main manuscript. Omit author(s)’s names in this process. The abstract will be submitted in the first step of submitting the manuscript; you will type the abstract in the box so labeled in ScholarOneManuscript. Be sure to save before moving to step two. Do not upload the abstract when you are uploading your manuscript.

The keywords are submitted in the second step of submitting the manuscript. You will select from a list of key words or input your own keywords. Be sure to save before moving forward to step three or going back to step one.

3. Text. Begin article text (main manuscript) on a new page headed by the full article title.

a. Headings and subheadings. Subheadings should indicate the organization of the content of the manuscript. Generally, three heading levels are sufficient to organize text. Level Format 1 Centered, Bold, Upper & Lowercase Text begins as a new paragraph. 2 Flush Left, Bold, Upper & Lowercase Text begins as a new paragraph. 3 Flush Left, Bold Italic, Upper & Lowercase Text begins as a new paragraph. 4 Indented, Bold, Upper & Lowercase, Ending with a Period. Text begins one space after the period of the heading. 5 Indented, Bold Italic, Upper & Lowercase, Ending with a Period. Text begins one space after the period of the heading. b. Citations. For each text citation there must be a corresponding reference in the reference list, and for each reference in the reference list there must be a corresponding text citation. Corresponding citations and references must have identical spelling and year. If you have three or more authors, ALL in-text citations are First Author et al. – e.g. (Brown et al., 2020). There is no longer a difference between first and subsequent citations. Each text citation must include at least two pieces of information, author(s) and year of publication. Following are some examples of text citations: (i) Unknown Author : To cite works that do not have an author, cite the source by its title in the signal phrase or use the first word or two in the citation parentheses. Example: The findings are based on the study of students learning to format research papers ("Using XXX," 2001). (ii) Authors with the Same Last Name: use first initials with the last names to prevent confusion. Example: (L. Hughes, 2001; P. Hughes, 1998) (iii) Two or More Works by the Same Author in the Same Year: For two sources by the same author in the same year, use lower-case letters (a, b, c, etc.) with the year to order the entries in the reference list. The lower-case letters should follow the year in the in-text citation. The lower case letters would also be used in the reference list. Example: Research by Freud (1981a) illustrated that… (iv) Personal Communication: For letters, e-mails, interviews, and other person-to-person communication, a personal communication citation should include the communicator's name, the fact that it was personal communication, and the date of the communication. Do not include personal communication in the reference list. Example: (E. Clark, personal communication, January 4, 2009). (v) Unknown Author and Unknown Date: For citations with no author or date, use the title in the signal phrase or the first word or two of the title in the citation parentheses and use the abbreviation "n.d." (for "no date"). Example: The study conducted by the research division discovered that students succeeded with tutoring ("Tutoring and APA," n.d.).

4. Notes. If explanatory notes are required for your manuscript, insert a number formatted in superscript following almost any punctuation mark. Footnote numbers should not follow dashes ( — ), and if they appear in a sentence in parentheses, the footnote number should be inserted within the parentheses. The Footnotes should be added at the end of the manuscript after the references. The word “Footnotes” should be centered at the top of the page.

5. References. Basic rules for the reference list:-

- The reference list should be arranged in alphabetical order according to the authors’ last names.

- If there is more than one work by the same author, order them according to their publication date – oldest to newest (therefore a 2008 publication would appear before a 2009 publication).

- When listing multiple authors of a source use “&” instead of “and.”

- Capitalize only the first word of the title and of the subtitle, if there is one, and any proper names (i.e. only those words that are normally capitalized).

- Italicize the title of the book, the title of the journal/serial, the volume number of the journal/serial, and the title of the web document.

- Every citation in the text must have the detailed reference in the Reference section.

- Every reference listed in the Reference section must be cited in text.

- Do not use “et al.” in the Reference list at the end; names of all authors of a publication should be listed there. However, for works with more than seven authors list the first six authors' names and then have three ellipses followed by the last author's name. Example: Zed, N., Alright, L., Volks, B., Clark, N., Times, R., Eagle, T., . . . Max, G. (2014).

Here are a few examples of commonly found references. For more examples please check the APA style manual (7 th Ed). Note: Format the references with a hanging indent, the first line of each reference is flush left and the subsequent lines are indented one-half inch.

Book with publisher

Airey, D. (2010). Logo design love: A guide to creating iconic brand identities . New Riders.

Book with editors & edition

Collins, C., & Jackson, S. (Eds.). (2007). Sport in Aotearoa/New Zealand society. Thomson.

English, B. (2013). A cultural history of fashion in the 20th and 21st centuries: From catwalk to sidewalk (2nd ed.). Bloomsbury.

Book having author & publisher the same

MidCentral District Health Board. (2008). District annual plan 2008/09 . Author.

Chapter in an edited book

Dear, J., & Underwood, M. (2007). What is the role of exercise in the prevention of back pain? In D. MacAuley & T. Best (Eds.), Evidence-based sports medicine (2nd ed., pp. 257-280). Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470988732.ch2

- Periodicals:

Journal article with more than one author (print)

Gabbett, T., Jenkins, D., & Abernethy, B. (2010). Physical collisions and injury during professional rugby league skills training. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 13 (6), 578-583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2010.03.007

Journal article – 7 or more authors

Crooks, C., Ameratunga, R., Brewerton, M., Torok, M., Buetow, S., Brothers, S., … Jorgensen, P. (2010). Adverse reactions to food in New Zealand children aged 0-5 years. New Zealand Medical Journal, 123 (1327). http://www.nzma.org.nz/journal/123-1327/4469/

- Internet Sources:

Internet – no author, no date

What is ecommerce? Launch and grow an online sales channel . (n.d.). https://sell.amazon.com/learn/what-is-ecommerce

Internet – Organization / Corporate author

National Council of Textile Organizations. (2022, May 11). State of the U.S. Textile Industry Address [Press release]. http://www.textilesinthenews.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/2022-State-of-the-Industry-Press-Release-FINAL-5.9.2022.pdf

- Examples of various types of information sources:

Act (statute/legislation)

Anti-Smuggling Act, 19 U.S.C. § 1701 (1935). https://www.loc.gov/item/uscode1958-004019005/

Liz and Ellory. (2011, January 19). The day of dread(s) [Web log post]. https://www.travelblog.org/Oceania/Australia/Victoria/Melbourne/St-Kilda/blog-669396.html

Brochure / pamphlet (no author)

Ageing well: How to be the best you can be [Brochure]. (2009). Ministry of Health.

Conference Paper

Williams, J., & Seary, K. (2010). Bridging the divide: Scaffolding the learning experiences of the mature age student. In J. Terrell (Ed.), Making the links: Learning, teaching and high quality student outcomes. Proceedings of the 9th Conference of the New Zealand Association of Bridging Educators , 104-116.

DVD / Video / Motion Picture (including Clickview & Youtube)

Gardiner, A., Curtis, C., & Michael, E. (Producers), & Waititi, T. (Director). (2010). Boy: Welcome to my interesting world [DVD]. Transmission.

Ng, A. (2011). Brush with history. Habitus , 13 , 83-87.

Newspaper article (no author)

Little blue penguins homeward bound. (2011, November 23). Manawatu Standard , p. 5

Podcast (audio or video)

April, C., & Cassidy, Z. (Hosts). (2018–present). Dressed: The History of Fashion [Audio podcast]. Dressed Media. https://www.iheart.com/podcast/105-dressed-the-history-of-fas-29000690/

Software (including apps)

ZOZO, INC. (2014). WEAR – Fashion Lookbook (Version 6.32.0) [Mobile application software]. https://apps.apple.com/us/app/wear-fashion-lookbook/id725208930

Television programme

Flanagan, A., & Philipson, A. (Series producers & directors). (2011). 24 hours in A & E [TV series]. Channel 4.

Thesis (print)

Smith, T. L. (2008). Change, choice and difference: The case of RN to BN degree programmes for registered nurses [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Victoria University of Wellington.

Thesis (online)

Mann, D. L. (2010). Vision and expertise for interceptive actions in sport (Doctoral dissertation, The University of New South Wales). http://handle.unsw.edu.au/1959.4/44704

Non-English reference book, title translated in English

Real Academia Espanola. (2001). Diccionario de la lenguaespanola [Dictionary of the Spanish Language] (22nd ed.). Author.

IMPORTANT NOTE: To encourage a faster production process of your article, you are requested to closely adhere to the points above for references. Otherwise, it will entail a long process of solving copyeditor’s queries and may directly affect the publication time of your article.

6. Tables. They should be structured properly and numbered consecutively in the order in which they appear in the text. Also, each table should be placed on a separate page. Each table must have a clear and concise title. When appropriate, use the title to explain an abbreviation parenthetically. Example: Comparison of Median Income of Adopted Children (AC) v. Foster Children (FC). Headings should be clear and brief. Follow APA style manual (7th edition) guidelines; do not include vertical lines in your table. For each table include a callout within the manuscript indicating the approximate location of the table (e.g., Place Table X about here."). Each table should be uploaded separately from the main manuscript.

7. Figures. They should be numbered consecutively in the order in which they appear in the text and must include figure captions. Also, each figure should be placed on a separate page. Figures will appear in the published article in the order in which they are numbered initially. The figure resolution should be 300dpi at the time of submission. For each figure include a callout within the manuscript indicating the approximate location of the figure (e.g., Place Figure X about here."). Each figure should be uploaded separately from the main manuscript.

IMPORTANT: PERMISSION - The author(s) are responsible for securing permission to reproduce all copyrighted figures or materials before they are published in CTRJ. A copy of the written permission must be included with the manuscript submission.

8. Appendices. They should be lettered to distinguish from numbered tables and figures. Include a descriptive title for each appendix (e.g., “Appendix A. Variable Names and Definitions”). Cross-check text for accuracy against appendices. If you include an appendix/appendices it/they will be counted as part of the 30 page maximum manuscript length.

9. Biography. A biographical sketch(es) (maximum 60 words) should be uploaded for the author(s) during step five, the "File Upload" process. Be sure to identify the biography document/file as "Author bio."

Uploaded manuscript length. Sage has allowed CTRJ a certain number of pages for each volume (year) so uploaded manuscripts must be no longer than 30 pages (main document with reference list, all tables and figures, and appendix/appendices if appropriate). When the submission is uploaded, each page in the main manuscript document will be counted as one page. Each table and each figure will be counted as one page. For example, a 26-page manuscript, plus two tables, plus two figures, equals a 30-page uploaded manuscript. If your manuscript exceeds this length it will not be reviewed.

Using AI in Manuscript Preparation

Sage has provided the guidance regarding the use of AI in authoring manuscripts submitted to the journal articles ( https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/chatgpt-and-generative-ai-0 ).

Authors are required to:

- Clearly indicate the use of language models in the manuscript, including which model was used and for what purpose. Please use the methods or acknowledgments sections, as appropriate.

- Verify the accuracy, validity, and appropriateness of the content and any citations generated by language models and correct any errors or inconsistencies.

- Provide a list of sources used to generate content and citations, including those generated by language models. Double-check citations to ensure they are accurate and are properly referenced.

- Be conscious of the potential for plagiarism where the large language models (LLM) may have reproduced substantial text from other sources. Check the original sources to be sure you are not plagiarizing someone else’s work.

- Acknowledge the limitations of language models in the manuscript, including the potential for bias, errors, and gaps in knowledge.

- Please note that AI bots such as ChatGPT should not be listed as authors on your submission.

Uploading Your Manuscript

Once the manuscript is prepared as described above, you can upload it and submit it through your Author Center in the Manuscript Central CTRJ portal. You should be taken to a screen that gives the link to your Author Center when you log into your account or when you complete the set up of your account.

Enter your Author Center and click on "Submit a Manuscript." The system will ask you for information regarding the manuscript and its authors. The contact author will enter the co-author names e-mail address(es) and that will send a prompt e-mail to the co-author asking him/her to complete the account information. You will be prompted to indicate the manuscript type (this is used to assign the AE) and other details of the manuscript. As you complete the information for the manuscript, you will have a field that allows you to type your cover letter directly into the system or browse and attach one. The cover page with author information is automatically generated as you complete the information about the manuscript, so a separate cover page with author identification is no longer necessary.

After you have uploaded the various files for your manuscript, you will need to “View Proof” before the system will allow you to submit. The system will then compile the various files into a single pdf file for you to review. If there are any problems with the compiled file, you may remove it, make corrections to the component files, and “View Proof” again. When you are satisfied with the compiled pdf, you are ready to submit the manuscript.

You may work on your submission in multiple stages by saving but not submitting your work prior to logging out. When you return to work on a manuscript submission that is not complete, you will access the manuscript through the Author Center by clicking on “Unsubmitted Manuscripts.” Once the manuscript submission is complete, you will receive a system-generated e-mail letting you know that the manuscript submission was successful.

Submitting a Revision

To submit your revised manuscript, log into http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/ctrj and enter your Author Center, where you will find your manuscript title listed under "Manuscripts with Decisions." Under "Actions," click on "Create a Revision." Your manuscript number will be appended to denote a revision.

When submitting your revised manuscript, we prefer that your response document be copied and pasted into the appropriate dialogue box. In your response to editors and reviewers DO NOT use bolding, different fonts, or different colored fonts to highlight your revised information. DO NOT use tables to indicate comments and responses in table format. All of these types of formatting are not preserved in Manuscript Central when you copy and paste them in the dialogue box. CAPS are preserved. In order to expedite the processing of the revised manuscript, please be as specific as possible in your response to the reviewer(s).

IMPORTANT: Your original files are available to you when you upload your revised manuscript. Please delete all files that are being replaced with revised files.

- Permissions

Authors are responsible for determining whether any material submitted is subject to copyright or ownership rights (e.g., quotations, illustrations, trade literature, data), and authors are responsible for obtaining permission to use such material when permission is required. Authors are also responsible for obtaining Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval prior to the initiation of the research if human subjects are to be used.

Review Process

Each manuscript is reviewed by at least four people: the editor, as associate editor, and two reviewers. The final recommendation is sent to the author(s). Outcomes about each of the decision categories is available here . Reviewers’ comments provide information and suggestions to authors that may be helpful in completing revisions. Authors are given a deadline for returning manuscripts at every stage in the publication process. Following manuscript acceptance and prior to publication, authors will receive galleys to check for errors.

Authors who would like to refine the use of English in their manuscripts might consider using the services of a professional English-language editing company. We highlight some of these companies at http://www.sagepub.com/journalgateway/engLang.htm . Please be aware that Sage has no affiliation with these companies and makes no endorsement of them. An author's use of these services in no way guarantees that his or her submission will ultimately be accepted. Any arrangement an author enters into will be exclusively between the author and the particular company, and any costs incurred are the sole responsibility of the author.

Note: CTRJ uses American-English language conventions.

If you or your funder wish your article to be freely available online to nonsubscribers immediately upon publication (gold open access), you can opt for it to be included in Sage Choice, subject to the payment of a publication fee. The manuscript submission and peer review procedure is unchanged. On acceptance of your article, you will be asked to let Sage know directly if you are choosing Sage Choice. To check journal eligibility and the publication fee, please visit Sage Choice . For more information on open access options and compliance at Sage, including self/author archiving deposits (green open access) visit Sage Publishing Policies on our Journal Author Gateway.

Supplemental Material

This journal is able to host additional materials online (e.g. datasets, podcasts, videos, images etc) alongside the full-text of the article. For more information please refer to our guidelines on submitting supplementary files .

Two-parts Research Manuscripts

If authors wish to submit two-part research manuscripts, they must submit both manuscripts at the same time with a clear distinction between the objectives of part one and part two. The two manuscripts may have the same goal but should have independent research objectives, and therefore, independent methods, results and contributions must be stated. It will be at the editors’ discretion if the manuscripts will be processed as two parts, need to be made into a single manuscript, or be rejected prior to double anonymized reviews. Two-part papers, if approved for further review, can both be assigned to the same reviewers throughout the double anonymized review processes.”

- Read Online

- Sample Issues

- Current Issue

- Email Alert

- Foreign rights

- Reprints and sponsorship

- Advertising

Individual Subscription, Print Only

Institutional Subscription, E-access

Institutional Subscription & Backfile Lease, E-access Plus Backfile (All Online Content)

Institutional Subscription, Print Only

Institutional Subscription, Combined (Print & E-access)

Institutional Subscription & Backfile Lease, Combined Plus Backfile (Current Volume Print & All Online Content)

Institutional Backfile Purchase, E-access (Content through 1998)

Individual, Single Print Issue

Institutional, Single Print Issue

To order single issues of this journal, please contact SAGE Customer Services at 1-800-818-7243 / 1-805-583-9774 with details of the volume and issue you would like to purchase.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Making Fashion Sustainable: Waste and Collective Responsibility

Debbie moorhouse.

1 Department of Fashion & Textiles, University of Huddersfield, Huddersfield, West Yorkshire, UK

Fashion is a growing industry, but the demand for cheap, fast fashion has a high environmental footprint. Some brands lead the way by innovating to reduce waste, improve recycling, and encourage upcycling. But if we are to make fashion more sustainable, consumers and industry must work together.

As the demand for apparel and shoes has increased worldwide, the fashion industry has experienced substantial growth. In the last 15 years, clothing production has doubled, accounting for 60% of all textile production. 1 One particular trend driving this increase is the emergence of fast fashion. The newest trends in celebrity culture and bespoke fashion shows rapidly become available from affordable retailers. In recent years, a designer’s fashion calendar can consist of up to five collections per year, and in the mass-produced market, new stock is being produced every 2 weeks. As with many commodities today, mass production and consumption are often accompanied by mass wastage, and fashion is no different.

In fashion, trends rapidly change, and a drive to buy the latest style can leave many items with a short lifespan and consigned to the waste bin. Given that 73% of clothing ends up in landfills and less than 1% is recycled into new clothing, there are significant costs with regard to not only irreplaceable resources but also the economy via landfilling clothing. At present, it is estimated that £140 million worth of clothing is sent to landfills in the UK each year. 2 Although a significant proportion of recycled fibers are downgraded into insulation materials, industrial wipes, and stuffing, they still constitute only 12% of total discarded material.

The world is increasingly worried about the environmental and social costs of fashion, particularly items that have short lifespans. Mass-produced fashion is often manufactured where labor is cheap, but working conditions can be poor. Sweatshops can even be found in countries with stricter regulations. The transport of products from places of manufacture to points of sale contributes to the textile industry’s rising carbon footprint; 1.2 billion metric tons of CO 2 were reportedly emitted in 2015. 1 Textile dyeing and finishing are thought to contribute to 20% of the world’s water pollution, 3 and microfiber emission during washing amounts to half a million metric tons of plastic pollution annually. 4 Fashion’s water footprint is particularly problematic. Water is used throughout clothing production, including in the growth of crops such as cotton and in the weaving, manufacturing, washing, and dyeing processes. The production of denim apparel alone uses over 5,000 L of water 5 for a single pair of jeans. When you add this to consumer overuse of water, chemicals, and energy in the laundry process and the ultimate discard to landfills or incineration, the environmental impact becomes extremely high.

As demand for fast fashion continues to grow, so too does the industry’s environmental footprint. Negative impacts are starkly evidenced throughout the entire supply chain—from the growth of raw materials to the disposal of scarcely used garments. As awareness of the darker side of fashion grows, so too does demand for change—not just from regulatory bodies and global action groups but also from individual consumers. People want ethical garments. Sustainability and style. But achieving this is complicated.

Demand for Sustainable Fashion

Historically, sustainable brands were sought by a smaller consumer base and were typically part of the stereotype “hippy” style. But in recent years, sustainable fashion has become more mainstream among both designers and consumers, and the aesthetic appeal has evolved to become more desirable to a wider audience. As a result, the consumer need not only buy into the ethics of the brand but also purchase a desirable, contemporary garment.

But the difficulty for the fashion industry lies in addressing all sustainability and ethical issues while remaining economically sustainable and future facing. Sustainable and ethical brands must take into account fairer wages, better working conditions, more sustainably produced materials, and a construction quality that is built for longevity, all of which ultimately increase the cost of the final product. The consumer often wrestles with many different considerations when making a purchase; some of these conflict with each other and can lead the consumer to prioritize the monetary cost.

Many buyers who place sustainability over fashion but cannot afford the higher cost of sustainable garments will often forsake the latest styles and trends to buy second hand. However, fashion and second-hand clothing need not be mutually exclusive, as can be seen by the growing trend of acquiring luxury vintage pieces. Vintage clothing is in direct contrast to the whole idea of “fast fashion” and is sought after as a way to express individuality with the added value of saving something precious from landfills. Where vintage might have once been purchased at an exclusive auction, now many online sources trade in vintage pieces. Celebrities, fashion influencers, and designers have all bought into this vintage trend, making it a very desirable pre-owned, pre-loved purchase. 6 In effect, the consumer mindset is changing such that vintage clothing (as a timeless, more considered purchase) is more desirable than new products because of its uniqueness, a virtue that stands against the standardization of mass-market production.

Making Fashion Circular

In an ideal system, the life cycle of a garment would be a series of circles such that the garment would continually move to the next life—redesigned, reinvented, and never discarded—eliminating the concept of waste. Although vintage is growing in popularity, this is only one component of a circular fashion industry, and the reality is that the linear system of “take, make, dispose,” with all its ethical and environmental problems, continues to persist.

Achieving sustainability in the production of garments represents a huge and complex challenge. It is often quoted that “more than 80% of the environmental impact of a product is determined at the design stage,” 7 meaning that designers are now being looked upon to solve the problem. But the responsibility should not solely lie with the designer; it should involve all stakeholders along the supply chain. Designers develop the concept, but the fashion industry also involves pattern cutters and garment technologists, as well as the manufacturers: both producers of textiles and factories where garment construction takes place. And finally, the consumer should not only dispose, reuse, or upcycle garments appropriately but also wash and care for the garment in a way that both is sustainable and ensures longevity of the item. These stakeholders must all work together to achieve a more sustainable supply chain.

The challenge of sustainability is particularly pertinent to denim, which, as already mentioned, is one of the more problematic fashion items. Traditionally an expression of individualism and freedom, denim jeans are produced globally at 1.7 billion pairs per year 8 through mass-market channels and mid-tier and premium designer levels, and this is set to rise. In the face of growing demand, some denim specialists are looking for ways to make their products more sustainable.

Reuse and recycling can play a role here, and designers and brands such as Levi Strauss & Co. and Mud Jeans are taking responsibility for the future life of their garments. They are offering take-back services, mending services, and possibilities for recycling to new fibers at end of life. Many brands have likewise embraced vintage fashion. Levi’s “Authorized Vintage” line, which includes upcycled, pre-worn vintage pieces, not only exemplifies conscious consumption but also makes this vintage trend more sought after by the consumer because of its iconic status. All material is sourced from the company’s own archive, and all redesigns “are a chance to relive our treasured history.” 9

Mud Jeans in particular is working toward a circular business model by taking a more considered, “seasonless” approach to their collections by instead focusing on longevity and pieces that transcend seasons. In addition, they offer a lease service where jeans can be returned for a different style and a return service at end of life for recycling into new fiber. The different elements that make up a garment, such as the base fabrics (denim in the case of Mud jeans) and fastenings, are limited so the company can avoid overstocking and reduce deadstock. 10 This model of keeping base materials to a minimum has been adopted by brands that don’t specialize in denim, such as Adidas’s production of a recyclable trainer made from virgin thermoplastic polyurethane. 11 The challenge with garments, as with footwear, is that they are made up of many different materials that are difficult to separate and sort for recycling. These business models have a long way to go to be truly circular, but some companies are paving the way forward, and their transparency is highly valuable to other companies that wish to follow suit.

Once a product is purchased, its future is in the hands of the consumer, and not all are aware of the recycling options available to them or that how they care for their garments can have environmental impacts. Companies are helping to inform them. In 2009, Levi Strauss & Co. introduced “Care Tag for Our Planet,” which gives straightforward washing instructions to save water and energy and guidance on how to donate the garment when it is no longer needed. Mud Jeans follows a similar process by highlighting the need to break the habit of regular unnecessary washing and even suggesting “air washing.” 10

At the same time, designers are moving away from the traditional seasonal production cycle and into a more seasonless calendar. In light of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, Gucci’s creative director, Alessandro Michele, has announced (May 2020) that the Italian brand will end the traditional five fashion shows per year and will “hold shows just twice a year instead to reduce waste.” 12 This is a brave decision because it goes against the practice whereby designers were pressured for decades to produce more collections per year, but the hope is that it will be quickly followed by more brands and designers.

Transparency

The discussion around sustainable fashion practices has led to a growing demand from consumers for transparency in the supply chain and life cycle of fashion garments. Consumers want to be informed. They are skeptical of media hype and “greenwashing” by fast-fashion companies wanting to make their brand appear responsible. They want to know the origin of the product and its environmental and social impact.

Some companies are responding by seeking a better understanding of the environmental impacts of their products. In 2015, denim specializer Levi Strauss & Co. extensively analyzed the garment life cycle to consider the environmental impact of a core set of products from its range. The areas highlighted for greatest water usage and negative environmental impact were textile production and consumer laundry care; the consumer phase alone consumed 37% of energy, 13 fiber and textile production accounted for 36% of energy usage, and the remaining 27% was spent on garment production, transport, logistics, and packaging. 14 This life-cycle analysis has led to innovation in waterless finishing processes that use 96% less water than traditional fabric finishing. 15 As noted previously, transparency here also inspires the wider industry to do likewise. Other companies have also introduced dyeing processes that need much less water, and much work is focused on improving textile recycling.

But this discussion does not just apply to production. Some high-street brands are using a “take back” scheme whereby customers are invited to bring back unwanted clothing either for a discount on future purchases or as a way to offload unwanted items of clothing. Not only might this encourage consumers to buy more without feeling guilty, but the ultimate destination of these returned garments can also be unclear. Without further transparency, a consumer cannot make fully informed decisions about the end-of-life fate of their garments.

Collective Responsibility

The buck should not be passed when it comes to sustainability; it is about collective responsibility. Professionals in the fashion industry often feel that it is in the hands of the consumer—they have the buying power, and their choices determine how the industry reacts. One train of thought is that the consumer needs to buy less and that the fashion retail industry can’t be asked to sell less. However, if a sustainable life cycle is to be achieved, stakeholders within the cycle must also be accountable, and there are growing demands for the fashion industry to be regulated.

With the global demand for new clothing, there is an urgent need to discover new materials and to find new markets for used clothing. At present, garments that last longer reduce production and processing impacts, and designers and brands can make efforts in the reuse and recycling of clothing. But environmental impact will remain high if large quantities of new clothing continue to be bought.

If we want a future sustainable fashion industry, both consumers and industry professionals must engage. Although greater transparency and sustainability are being pursued and certain brands are leading the way, the overconsumption of clothing is so established in society that it is difficult to say how this can be reversed or slowed. Moreover, millions of livelihoods depend on this constant cycle of fashion production. Methods in the recycling, upcycling, reuse, and remanufacture of apparel and textiles are short-term gains, and the real impact will come from creating new circular business models that account for the life cycle of a garment and design in the initial concept. If we want to maximize the value from each item of clothing, giving them second, third, and fourth lives is essential.

Acknowledgments

Thank you for support, in writing this Commentary, to Dr. Rina Arya, Professor of Visual Culture and Theory at the School of Art, Design, and Architecture of the University of Huddersfield, West Yorkshire, UK.

Declaration of Interests

The author is the co-founder of the International Society for Sustainable Fashion.

- Open access

- Published: 27 December 2018

The global environmental injustice of fast fashion

- Rachel Bick 1 na1 ,

- Erika Halsey 1 na1 &

- Christine C. Ekenga ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6209-4888 1

Environmental Health volume 17 , Article number: 92 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

600k Accesses

164 Citations

483 Altmetric

Metrics details

Fast fashion, inexpensive and widely available of-the-moment garments, has changed the way people buy and dispose of clothing. By selling large quantities of clothing at cheap prices, fast fashion has emerged as a dominant business model, causing garment consumption to skyrocket. While this transition is sometimes heralded as the “democratization” of fashion in which the latest styles are available to all classes of consumers, the human and environmental health risks associated with inexpensive clothing are hidden throughout the lifecycle of each garment. From the growth of water-intensive cotton, to the release of untreated dyes into local water sources, to worker’s low wages and poor working conditions; the environmental and social costs involved in textile manufacturing are widespread.

In this paper, we posit that negative externalities at each step of the fast fashion supply chain have created a global environmental justice dilemma. While fast fashion offers consumers an opportunity to buy more clothes for less, those who work in or live near textile manufacturing facilities bear a disproportionate burden of environmental health hazards. Furthermore, increased consumption patterns have also created millions of tons of textile waste in landfills and unregulated settings. This is particularly applicable to low and middle-income countries (LMICs) as much of this waste ends up in second-hand clothing markets. These LMICs often lack the supports and resources necessary to develop and enforce environmental and occupational safeguards to protect human health. We discuss the role of industry, policymakers, consumers, and scientists in promoting sustainable production and ethical consumption in an equitable manner.

Peer Review reports

Fast fashion is a term used to describe the readily available, inexpensively made fashion of today. The word “fast” describes how quickly retailers can move designs from the catwalk to stores, keeping pace with constant demand for more and different styles. With the rise of globalization and growth of a global economy, supply chains have become international, shifting the growth of fibers, the manufacturing of textiles, and the construction of garments to areas with cheaper labor. Increased consumption drives the production of inexpensive clothing, and prices are kept down by outsourcing production to low and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Globally, 80 billion pieces of new clothing are purchased each year, translating to $1.2 trillion annually for the global fashion industry. The majority of these products are assembled in China and Bangladesh while the United States consumes more clothing and textiles than any other nation in the world [ 1 ]. Approximately 85 % of the clothing Americans consume, nearly 3.8 billion pounds annually, is sent to landfills as solid waste, amounting to nearly 80 pounds per American per year [ 2 , 3 ].

The global health costs associated with the production of cheap clothing are substantial. While industrial disasters such as the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire have led to improved occupational protections and work standards in the United States, the same cannot be said for LMICs. The hazardous working conditions that attracted regulatory attention in the United States and European Union have not been eliminated, but merely shifted overseas. The social costs associated with the global textile and garment industry are significant as well. Defined as “all direct and indirect losses sustained by third persons or the general public as a result of unrestrained economic activities,” the social costs involved in the production of fast fashion include damages to the environment, human health, and human rights at each step along the production chain [ 4 ].

Fast fashion as a global environmental justice issue

Environmental justice is defined by the United States Environmental Protection Agency, as the “fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations and policies” [ 5 ]. In the United States, this concept has primarily been used in the scientific literature and in practice to describe the disproportionate placement of superfund sites (hazardous waste sites) in or near communities of color. However, environmental justice, as it has been defined, is not limited to the United States and need not be constrained by geopolitical boundaries. The textile and garment industries, for example, shift the environmental and occupational burdens associated with mass production and disposal from high income countries to the under-resourced (e.g. low income, low-wage workers, women) communities in LMICs. Extending the environmental justice framework to encompass the disproportionate impact experienced by those who produce and dispose of our clothing is essential to understanding the magnitude of global injustice perpetuated through the consumption of cheap clothing. In the context of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 12 which calls for sustainable consumption and production as part of national and sectoral plans, sustainable business practices, consumer behavior, and the reduction and elimination of fast fashion should all be a target of global environmental justice advocates.

Environmental hazards during production

The first step in the global textile supply chain is textile production, the process by which both natural and synthetic fibers are made. Approximately 90 % of clothing sold in the United States is made with cotton or polyester, both associated with significant health impacts from the manufacturing and production processes [ 6 ]. Polyester, a synthetic textile, is derived from oil, while cotton requires large amounts of water and pesticides to grow. Textile dyeing results in additional hazards as untreated wastewater from dyes are often discharged into local water systems, releasing heavy metals and other toxicants that can adversely impact the health of animals in addition to nearby residents [ 6 ].

Occupational hazards during production

Garment assembly, the next step in the global textile supply chain, employs 40 million workers around the world [ 7 ]. LMICs produce 90% of the world’s clothing. Occupational and safety standards in these LMICs are often not enforced due to poor political infrastructure and organizational management [ 8 ]. The result is a myriad of occupational hazards, including respiratory hazards due to poor ventilation such as cotton dust and synthetic air particulates, and musculoskeletal hazards from repetitive motion tasks. The health hazards that prompted the creation of textile labor unions in the United States and the United Kingdom in the early 1900’s have now shifted to work settings in LMICs. In LMICs, reported health outcomes include debilitating and life-threatening conditions such as lung disease and cancer, damage to endocrine function, adverse reproductive and fetal outcomes, accidental injuries, overuse injuries and death [ 9 , 10 , 11 ]. Periodic reports of international disasters, such as the 2013 Rana Plaza factory collapse which killed 1134 Bangladeshi workers, are stark reminders of the health hazards faced by garment workers. These disasters, however, have not demonstrably changed safety standards for workers in LMICs [ 12 ].

Textile waste

While getting finished garments to consumers in the high-income countries is seen as the end of the line for the fashion industry, environmental injustices continue long after the garment is sold. The fast fashion model encourages consumers to view clothing as disposable. In fact, the average American throws away approximately 80 pounds of clothing and textiles annually, occupying nearly 5% of landfill space [ 3 ]. Clothing not sent directly to the landfill often ends up in the second-hand clothing trade. Approximately 500,000 tons of used clothing are exported abroad from the United States each year, the majority ending up in LMICs [ 8 ]. In 2015, the United States exported more than $700 million worth of used clothing [ 13 ]. Second-hand clothing not sold in the United States market is compressed into 1000-pound bales and exported overseas to be “graded” (sorted, categorized and re-baled) by low-wage workers in LMICs and sold in second-hand markets. Clothing not sold in markets becomes solid waste, clogging rivers, greenways, and parks, and creating the potential for additional environmental health hazards in LMICs lacking robust municipal waste systems.

Solutions, innovation, and social justice

Ensuring environmental justice at each stage in the global supply chain remains a challenge. Global environmental justice will be dependent upon innovations in textile development, corporate sustainability, trade policy, and consumer habits.

Sustainable fibers

The sustainability of a fiber refers to the practices and policies that reduce environmental pollution and minimize the exploitation of people or natural resources in meeting lifestyle needs. Across the board, natural cellulosic and protein fibers are thought to be better for the environment and for human health, but in some cases manufactured fibers are thought to be more sustainable. Fabrics such as Lyocell, made from the cellulose of bamboo, are made in a closed loop production cycle in which 99% of the chemicals used to develop fabric fibers are recycled. The use of sustainable fibers will be key in minimizing the environmental impact of textile production.

Corporate sustainability

Oversight and certification organizations such as Fair Trade America and the National Council of Textiles Organization offer evaluation and auditing tools for fair trade and production standards. While some companies do elect to get certified in one or more of these independent accrediting programs, others are engaged in the process of “greenwashing.” Capitalizing on the emotional appeal of eco-friendly and fair trade goods, companies market their products as “green” without adhering to any criteria [ 14 ]. To combat these practices, industry-wide adoption of internationally recognized certification criteria should be adopted to encourage eco-friendly practices that promote health and safety across the supply chain.

Trade policy

While fair trade companies can attempt to compete with fast fashion retailers, markets for fair trade and eco-friendly textile manufacturing remain small, and ethically and environmentally sound supply chains are difficult and expensive to audit. High income countries can promote occupational safety and environmental health through trade policy and regulations. Although occupational and environmental regulations are often only enforceable within a country’s borders, there are several ways in which policymakers can mitigate the global environmental health hazards associated with fast fashion. The United States, for example, could increase import taxes for garments and textiles or place caps on annual weight or quantities imported from LMICs. At the other end of the clothing lifecycle, some LMICs have begun to regulate the import of used clothing. The United Nations Council for African Renewal, for example, recently released a report citing that “Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda are raising taxes on secondhand clothes imports and at the same time offering incentives to local manufacturers” [ 15 ].

The role of the consumer

Trade policies and regulations will be the most effective solutions in bringing about large-scale change to the fast fashion industry. However, consumers in high income countries have a role to play in supporting companies and practices that minimize their negative impact on humans and the environment. While certifications attempt to raise industry standards, consumers must be aware of greenwashing and be critical in assessing which companies actually ensure a high level of standards versus those that make broad, sweeping claims about their social and sustainable practices [ 14 ]. The fast fashion model thrives on the idea of more for less, but the age-old adage “less in more” must be adopted by consumers if environmental justice issues in the fashion industry are to be addressed. The United Nation’s SDG 12, “Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns,” seeks to redress the injustices caused by unfettered materialism. Consumers in high income countries can do their part to promote global environmental justice by buying high-quality clothing that lasts longer, shopping at second-hand stores, repairing clothing they already own, and purchasing from retailers with transparent supply chains.

Conclusions

In the two decades since the fast fashion business model became the norm for big name fashion brands, increased demand for large amounts of inexpensive clothing has resulted in environmental and social degradation along each step of the supply chain. The environmental and human health consequences of fast fashion have largely been missing from the scientific literature, research, and discussions surrounding environmental justice. The breadth and depth of social and environmental abuses in fast fashion warrants its classification as an issue of global environmental justice.

Environmental health scientists play a key role in supporting evidence-based public health. Similar to historical cases of environmental injustice in the United States, the unequal distribution of environmental exposures disproportionally impact communities in LMICs. There is an emerging need for research that examines the adverse health outcomes associated with fast fashion at each stage of the supply chain and post-consumer process, particularly in LMICs. Advancing work in this area will inform the translation of research findings to public health policies and practices that lead to sustainable production and ethical consumption.

Abbreviations

Low and middle-income countries

Sustainable Development Goal

Claudio L. Waste couture: environmental impact of the clothing industry. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115(9):A449.

Article Google Scholar

Hobson, J., To die for? The health and safety of fast fashion. 2013, Oxford University Press UK.

Wicker, A. Fast Fashion Is Creating an Environmental Crisis. Newsweek. September 1, 2016; Available from: https://www.newsweek.com/2016/09/09/old-clothes-fashion-waste-crisis-494824.html . Accessed 13 Aug 2018.

Kapp, K.W., The social costs of business enterprise. 1978: Spokesman Books.

United States Environmental Protection Agency. Environmental Justice. August 13, 2018; Available from: https://www.epa.gov/environmentaljustice .

Khan, S. and A. Malik, Environmental and health effects of textile industry wastewater, in Environmental deterioration and human. health. 2014, Springer. p. 55–71.

Siegle L. To die for: is fashion wearing out the world? UK: HarperCollins; 2011.

Google Scholar

Anguelov N. The dirty side of the garment industry: Fast fashion and its negative impact on environment and Society. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2016.

Sant'Ana MA, Kovalechen F. Evaluation of the health risks to garment workers in the city of Xambrê-PR, Brazil. Work. 2012;41(Supplement 1):5647–9.

Akhter S, Rutherford S, Chu C. What makes pregnant workers sick: why, when, where and how? An exploratory study in the ready-made garment industry in Bangladesh. Reprod Health. 2017;14(1):142.

Gebremichael G, Kumie A. The prevalence and associated factors of occupational injury among workers in Arba Minch textile factory, southern Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. Occupational medicine and health affairs. 2015;3(6):e1000222.

M. Taplin, I., who is to blame? A re-examination of fast fashion after the 2013 factory disaster in Bangladesh critical perspectives on international business, 2014. 10(1/2): p. 72–83.

Elmer, V. Fashion Industry: U.S. Exports of Used Clothing Increase. 2017; Available from: http://businessresearcher.sagepub.com/sbr-1863-101702-2767082/20170116/u.s.-exports-of-used-clothing-increase . Accessed 8 Mar 2018.

Lyon TP, Montgomery AW. The means and end of greenwash. Organization & Environment. 2015;28(2):223–49.

Kuwonu, F. Protectionist ban on imported used clothing. 2017; Available from: https://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/december-2017-march-2018/protectionist-ban-imported-used-clothing . Accessed 8 Mar 2018.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Availability of data and materials

Author information.

Rachel Bick and Erika Halsey contributed equally to this work.

Authors and Affiliations

Brown School, Washington University in St. Louis, Campus Box 1196, One Brookings Drive, St. Louis, MO, 63130, USA

Rachel Bick, Erika Halsey & Christine C. Ekenga

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors were involved the conception of the work. RB and EH drafted the manuscript, and CE revised the manuscript critically and approved the final version for submission. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Christine C. Ekenga .

Ethics declarations

Authors’ information, ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Bick, R., Halsey, E. & Ekenga, C.C. The global environmental injustice of fast fashion. Environ Health 17 , 92 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-018-0433-7

Download citation

Received : 21 August 2018

Accepted : 28 November 2018

Published : 27 December 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-018-0433-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Environmental health

- Occupational health

- Global health

- Environmental justice

- Sustainability

- Fast fashion

Environmental Health

ISSN: 1476-069X

- General enquiries: [email protected]

International Journal of Interdisciplinary Research

- Open access

- Published: 25 December 2022

Evaluation and trend of fashion design research: visualization analysis based on CiteSpace

- Yixin Zou ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1880-6382 1 ,

- Sarawuth Pintong 2 ,

- Tao Shen 3 &

- Ding-Bang Luh 1

Fashion and Textiles volume 9 , Article number: 45 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

10k Accesses

4 Citations

Metrics details

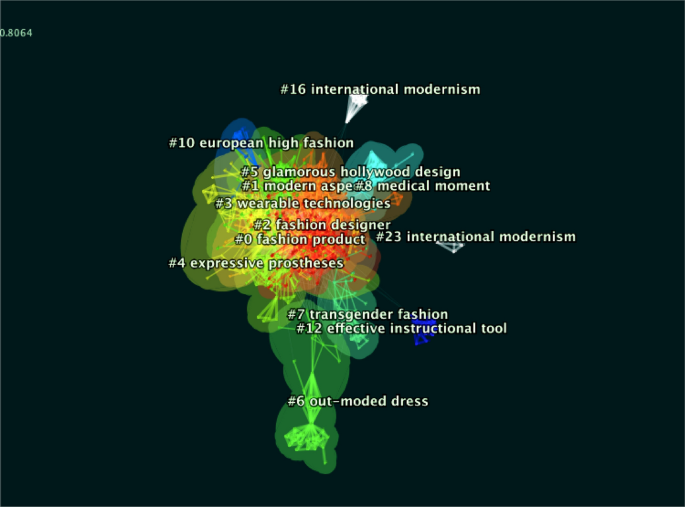

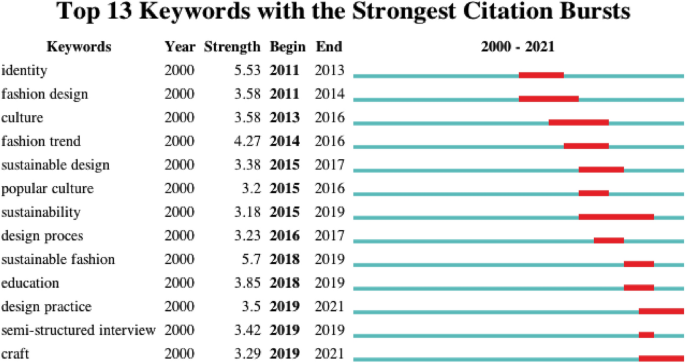

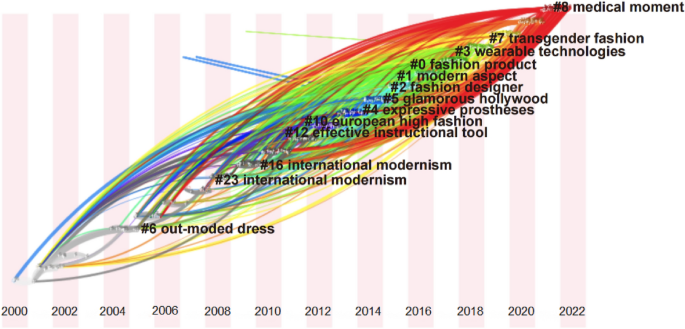

Fashion or apparel refers to a topic discussed publicly as an indispensable discipline on a day-to-day basis, which has aroused rising attention from academic sessions over the past two decades. However, since the topic of fashion design covers knowledge in extensive ranges and considerable information, scholars have not fully grasped the research field of fashion design, and the research lacks directional guidance. To gain more insights into the existing research status and fronts in the fashion design field, this study conducts a quantitative literature analysis. The research of this study is conducted by employing CiteSpace technology to visualize and analyze 1388 articles regarding “fashion design” in the Web of Science (WOS) Core Collection. To be specific, the visualization and the analysis concentrate on the annual number of articles, author collaboration, institutional collaboration, literature citations, keywords clustering, and research trend evolution of the mentioned articles. As highlighted by this study, the effect of the US and the UK on academic research in fashion design is relatively stronger and extensive. Sustainable fashion refers to the research topic having aroused more attention since 2010, while new research topics over the past few years consist of “wearable fashion”, “transgender fashion” and “medical fashion”. The overall research trend of fashion design is developing as interdisciplinary cross research. This study systematically reviews the relevant literature, classifies the existing research status, research hotspots and frontier trends in the academic field of “fashion design”, and presents the knowledge map and information of literature for researchers in relevant fields.

Introduction

In academic research and writing, researchers should constantly search relevant literature to gain systematic insights into the subject area (e.g., the major research questions in the field, the seminal studies, the landmark studies, the most critical theories, methods and techniques, as well as the most serious current challenges). The process to answer the mentioned questions refers to an abstract process, which requires constant analysis, deduction and generalization. Any literature emerging over time may be critical, any research perspective may cause novel inspiration, and any detail can be the beginning of the subsequent research. However, when literature is being sorted and analyzed, if judgment only complies with personal experience, important literature will be inevitably missed, or the research direction will be lost in the research. For the process of conducting literature analysis, Hoover proposed that the quantitative methods of literature represent elements or features of literary texts numerically, applying effective, accurate and widely accepted mathematical methods to measure, classify and analyze literature quantitatively (Hoover, 2013 ). On this basis, literary data and information are more comprehensively processed. Prof. Chaomei Chen developed CiteSpace to collect, analyze, deliver and visualize literature information by creating images, diagrams or animations, thereby helping develop scientific knowledge maps and data mining of scientific literature. Knowledge visualization primarily aims to detect and monitor the existing state of research and research evolution in a knowledge field. Knowledge visualization has been exploited to explore trends in fields (e.g., medical, management science, biomedicine and biotechnology).

However, the international research situation in fashion design has not been analyzed by scholars thus far. Fashion, a category of discourse, has been arousing scholars’ attention since the late nineteenth century (Kim, 1998 ). In such an era, fashion is recognized by individuals of all classes and cultures, and it is publicly perceived. The field of fashion design is significantly correlated with people's lives (Boodro, 1990 ), and numerous nations and universities have long developed courses regarding fashion design or fashion. Besides, the development of fashion acts as a symbol of the soft power of the country. The discussion on fashion trend, fashion designer, fashion brands, artwork and other topics in the society turns out to be the hotspot discussed on a nearly day-to-day basis, and the discussion in the society even exceeds the academic research. However, the academic research of fashion design refers to a topic that cannot be ignored. The accumulation and achievements of academic research are manifested as precipitation of knowledge for developing the existing fashion field, while significantly guiding future generations. Studying the publishing situation and information in fashion design will help fashion practitioners or researchers classify their knowledge and provide them with novel inspiration or research and literature directions.

This study complies with the method of quantitative literature analysis, and CiteSpace software is adopted to analyze the literature in fashion design. Through searching web of science (WOS) Core Collection, 1388 articles regarding “fashion design” are retained. Co-citation, co-authoring and co-occurrence analysis refer to the major functions of CiteSpace. This study analyzes the articles regarding “fashion design”, and the focus is placed on the annual publication volume, author collaboration, institutional collaboration, national collaboration, literature citations, keyword co-occurrence, keyword clustering, and the research evolution, and visualized the literature and research as figures of these articles. The results here are presented as figures. This study provides the fronts knowledge, the current research status research, the hotspots and trends in fashion design research.

In this study, CiteSpace technology is adopted to analyze all collected literature data. CiteSpace, developed by Professor Chaomei Chen, an internationally renowned expert in information visualization at Drexel University, USA (Wang & Lu, 2020 ), refers to a Java application to visually analyze literature and co-citation networks (Chen, 2004 ). CiteSpace is capable of displaying burst detection, mediated centrality and heterogeneous networks regarding literate information. Visual analysis of the literature by using CiteSpace covers three functions, i.e., to identify the nature of specialized research frontiers, to label and cluster specialized research areas, as well as to identify the research trends and abrupt changes based on the data derived from the analysis. CiteSpace provides a valuable, timely, reproducible and flexible method to track the development of research trends and identify vital evidence (Chen et al., 2012 ).

To analyze the existing status of research and publications on the topic of “fashion design” in academia and different nations, the “Web of Science” (WOS) database is adopted as the data collection source here. Web of Science provides seamless access to existing and multidisciplinary information from approximately 8700 of the most extensively researched, prestigious and high-impact research journals worldwide, covering Science Citation Index (SCI) Social Science Citation Index (SSCI), as well as Arts and Humanities Citation Index (A&HCI) (Wouters 2006 ). Its vital feature is that it covers all article types, e.g., author information, institutional addresses, citations and References (Wouters 2006 ). Research trends and publications in specific industry areas can be effectively analyzed.

To be specific, the “Web of Science Core Collection” database is selected in Web of Science and the indexing range includes SCI, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI databases. This step aims to expand the search scope of journals and search a maximal amount of relevant literature. A “subject search” is adopted, covering the search title, the abstract, the author and the keywords. There have been other areas of research on clothing or textiles (e.g., textile engineering and other scientific research areas). However, in this study, to ensure that the topic of analysis is relevant, the subject search is conducted by entering “fashion design” or “Costume design” clothing design”, or “Apparel design”, and only academic research regarding fashion design is analyzed. To ensure the academic nature of the collected data, the search scope here is the “article” type. The time frame was chosen from 2000 to 2021 to analyze the publications on “fashion design” for past 21 years. After this operation, the results of the search were filtered two times. The search was conducted until September 23, 2021, and 1388 articles were retained on the whole.

All bibliographic information on the pages was exported into text format and subsequently analyzed with CiteSpace software. Retrieved publications were filtered and copies were removed in CiteSpace to ensure that the respective article is unique and unduplicated in the database. 1388 articles filtered down from 2000 to 2021 were analyzed in all time slices of 1 year, and most of the cited or TOP 50 of the respective item were selected from each slice.

Results and Discussion

Publications in the last 21 years.

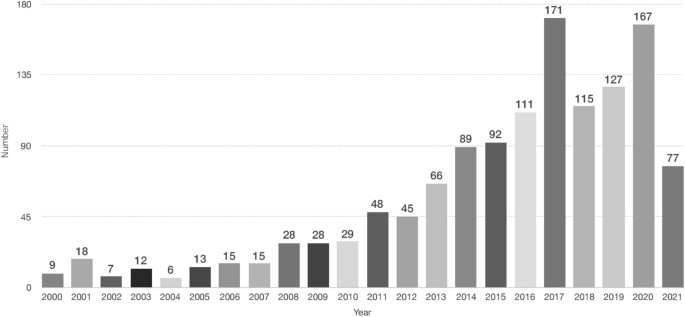

The publication situation of WOS database with “fashion design” as the theme from 2000 to 2021 shown in Fig. 1 . On the whole, the number of articles published on the theme of “fashion design” is rising from 2000 to 2007, the number of articles published each year is almost identical, and the number of articles published in 2008–2009 is slightly increasing. The second wave of growth is in 2011, with an increase about 60% compared with the number of publications in 2010, and it has been rising year by year. 2017 is the peak year with a high volume of 171 publications. 2018 shows another decline, whereas over 100 publications remain. 2018, 2019 and 2020 show continuous growths again. As of September 2021, the number of publications in 2021 is 77. Although the number of articles declines in 2018, the overall number of articles over the past 2 decades is still rising. The reason for the low number of publications around year of 2000 is that fashion as a category of discourse has aroused the attention of scholars from the late nineteenth century (Kim, 1998 ). The year-on-year increase is explained as research on fashion is arousing rising attention from scholars. The significant increase in research papers regarding “fashion design” in 2016 and 2017 is that around 2016, and the fashion industry has been impacted by technological developments. Moreover, the way in which design and clothing made has incorporated considerable technological tools (e.g., 3D printing and wearable technology).

Total publications and sum of times cited from 2000 to 2021 according to the web of science. Data updated to September 2021

Author co-authorship analysis

The knowledge map of cited authors based on publication references can present information regarding influential research groups and potential collaborators (Liang, Li, Zhao, et al., 2017 ). The function of co-authorship analysis is employed in CiteSpace to detect influential research groups and potential collaborators. Citespace can calculate the most productive authors in related fields. Table 1 shows that the most productive authors, which related with fashion design theme.

The author with the maximal number of publications is Olga Gurova from Laurea University of Applied Sciences in Helsinki (Finland). Her research area has focused on consumer nationalism and patriotism, identity politics and fashion, critical approach to sustainability and wearable technology and the future. Sustainable design has been a hotspot over the past decade and continues to be discussed today, and wearable technology has been a research hotpot in recent years. Olga Gurova is in first place, thereby suggesting the attention given to the mentioned topics and studies in society and fashion area. The second ranked author is Marilyn Delong from University of Minnesota (The USA). The research area consists of Aesthetics, Sustainable apparel design, History and Material Culture, Fashion Trends, Cross-cultural Influence on Design, as well as Socio-psychological aspects of Clothing. The author with the identical number of 7 publications is Kirsi Niinimäki from Aalto University (Finland). Her research directions consist of sustainable fashion and textiles, so her focus has been on the connection between design, manufacturing systems, business models and consumption habits.

For Caroline Kipp, her research area includes modern and contemporary textile arts, decorative arts and craft, craftivism, jacquard weaving, French kashmere shawls, as well as color field painting. For Nick Rees-Roberts, his research area includes fashion film, culture and digital media. Veronica Manlow from Brooklyn College in the Koppelman School of Business (USA.) The research field consists of creative process of fashion design, organizational culture and leadership in corporate fashion brands. Kevin Almond has made a contribution to creative Pattern Cutting, Clothing/Fashion Dichotomies, Sculptural Thinking in Fashion, Fashion as Masquerade. Hazel Clark, and his research field covers fashion theory and history, fashion in China, fashion and everyday life, fashion politics and sustainment. As revealed from the organization of the authors' work institutions and nations in the table, most of the nations with the maximal frequency of publications originate from the US, thereby revealing that the US significantly supports fashion design research. In general, the research scope covers fashion design, culture, mass media, craft, marketing, humanities, technology and etc. Based on the statistics of authorship collaboration, this study indicates that scholars from the US and Finland take up the top positions in the authorship publication ranking.

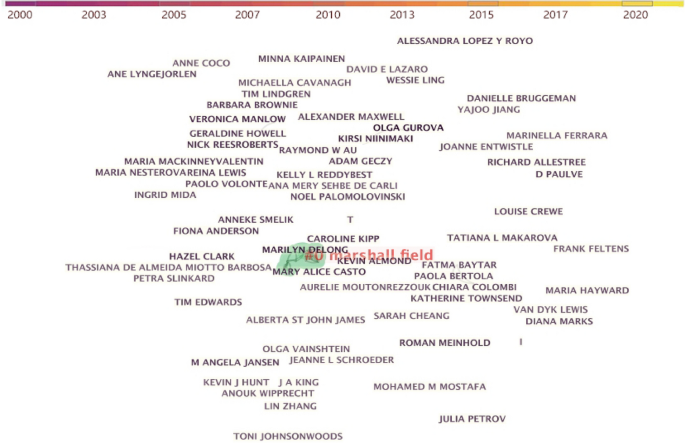

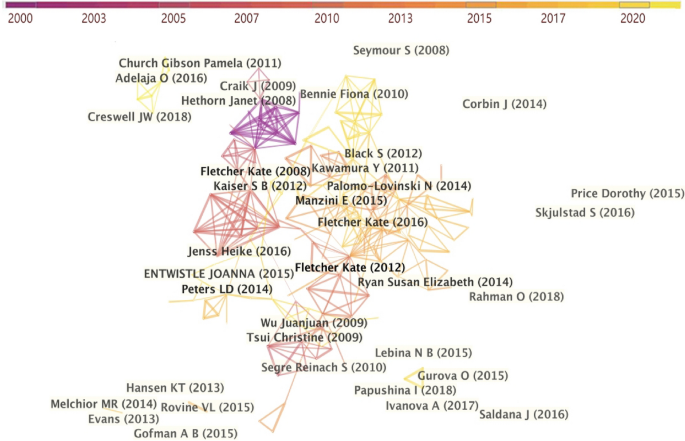

Moreover, Fig. 2 shows the academic collaborations among authors, which are generated by selecting the unit of analysis, setting the appropriate thresholds. The distance between the nodes and the thickness of the links denote the level of cooperation among authors (Chen & Liu, 2020 ). The influential scholars and the most active authors have not yet developed a linear relationship with each other, and collaborative networks have been lacked. It is therefore revealed that the respective researcher forms his or her own establishment in his or her own field, whereas seldom forms collaborative relationships. Thus, this study argues that to improve the breadth and depth of the field of fashion design research, the cooperation and connections between authors should be strengthened (e.g., organizing international collaborative workshops, joint publications and academic conferences) to up-regulate the amount of knowledge output and create more possibilities for fashion research.

Author collaboration network

Institution co-authorship analysis

The number of articles issued by the respective institution and the partnership network are listed in Table 2 .

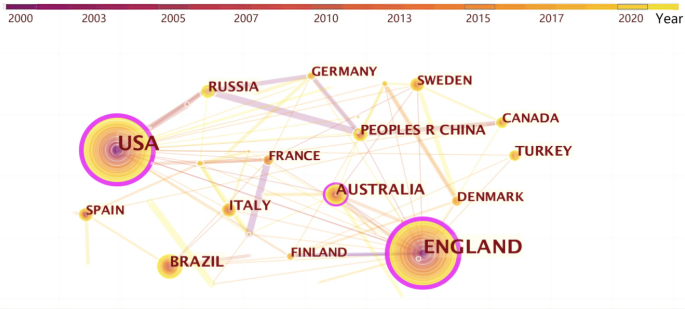

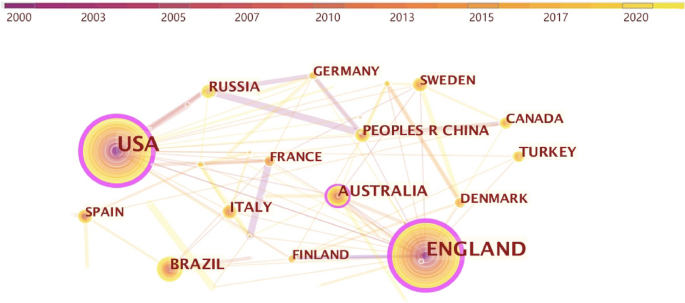

Figure 3 shows the collaborative relationships among research institutions, while the distance between nodes and the thickness of links represents the level of collaborative institutions. The size of the nodes represents the number of papers published by the institutions, while the distance between the nodes and the thickness of the links indicates the level of cooperation between the institutions.

Co-relationships between nations in “fashion design” research