Andrew Carnegie: Pioneer. Visionary. Innovator.

Meet the father of modern philanthropy.

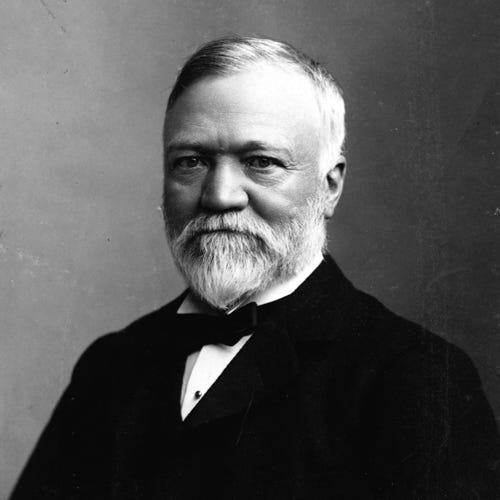

Andrew Carnegie (1835–1919) was among the wealthiest and most famous industrialists of his day. Through Carnegie Corporation of New York, the innovative philanthropic foundation he established in 1911, his fortune has since supported everything from the discovery of insulin and the dismantling of nuclear weapons, to the creation of Pell Grants and Sesame Street. The work of the Corporation and its grantees has helped shape public discourse and policy for more than one hundred years. Millions of people have benefited from Carnegie’s foresighted generosity — a legacy of real and permanent good. We invite you to learn more about this remarkable man’s life through an interactive timeline, historical documents, photographs, audio, and more.

• Humble Beginnings

• keen eye for opportunity, • wealthiest man in the world, • giving and legacy, • further reading, • historical documents, • gospel of wealth, “to try to make the world in some way better than you found it is to have a noble motive in life.”, andrew carnegie, the empire of business, andrew carnegie birthplace, the andrew carnegie birthplace museum adjoins the cottage in dunfermline, scotland where andrew carnegie, the son of a handloom weaver, was born on november 25, 1835. mr. carnegie’s first public gift was for the town of dunfermline. in 1874 he donated £5,000 for the carnegie baths recreation and health club, which was followed in 1880 by his gift for a public library., humble beginnings.

Andrew Carnegie’s birthplace, Dunfermline, was Scotland’s historic medieval capital. Later famous for producing fine linen, the town fell on hard times when industrialism made home-based weaving obsolete, leaving workers such as Carnegie’s father, Will, hard pressed to support their families. Will and his father-in-law Thomas Morrison, a shoemaker and political reformer, joined the popular Chartist movement, which believed conditions for workers would improve if the masses were to take over the government from the landed gentry. When the movement failed in 1848, Will Carnegie and his wife, Margaret, sold their belongings to book passage to America for themselves and their sons, 13-year-old Andrew and 5-year-old Tom.

“We sailed from the Broomielaw of Glasgow in the 800-ton sailing ship Wiscasset…”

Andrew carnegie (right) at age 16, photographed in 1851 with his younger brother, thomas, shorty after their arrival in america, an immigrant’s journey.

Andrew Carnegie’s family decided to settle in Allegheny, Pennsylvania, a suburb of Pittsburgh where they had friends and relatives. Their ship landed in New York City, which he found bewildering: “New York was the first great hive of human industry among the inhabitants of which I had mingled, and the bustle and excitement of it overwhelmed me,” Carnegie wrote in his autobiography. Next the family traveled west by canal and steamboat, arriving in Allegheny three weeks later (a 370-mile, six-hour trip by car today). They moved into two rooms above a relative’s weaving shop, which his father took over, but the business ultimately failed, putting the family once again in need of money.

“The emigrant is the capable, energetic, ambitious, discontented man.”

The carnegie steel company plant in youngstown, ohio, 1910, industrious youth.

At the age of 13, Carnegie worked from dawn until dark as a bobbin boy in a cotton mill, carrying bobbins to the workers at the looms and earning $1.20 per week. A year later, he was hired as a messenger for a local telegraph company, where he taught himself how to use the equipment and was promoted to telegraph operator. With this skill he landed a job with the Pennsylvania Railroad, where he was promoted to superintendent at age 24. Not just ambitious, young Carnegie was a voracious reader, and he took advantage of the generosity of an Allegheny citizen, Colonel James Anderson, who opened his library to local working boys — a rare opportunity in those days. Through the years books provided most of Andrew Carnegie’s education, remaining invaluable as he rapidly progressed through his career.

“It was from my own early experience that I decided there was no use to which money could be applied so productive… as the founding of a public library.”

The first carnegie library in the u.s. in braddock, pennsylvania, site of his steel mills, keen eye for opportunity.

Thomas A. Scott, superintendent of the western division of the Pennsylvania Railroad and Andrew Carnegie’s boss, initiated the future millionaire’s first investment when he alerted Carnegie to the impending sale of ten shares in the Adams Express Company. By mortgaging their house, Margaret Carnegie obtained $500 to buy the shares, and soon the first stream of dividends began rolling in.

While associated with the railroad, Carnegie developed a wide variety of other business interests. Theodore Woodruff approached him with the idea of sleeping cars on railways, offering him a share in the Woodruff Sleeping Car Company. Carnegie secured a bank loan to accept Woodruff’s proposal — a decision he would not regret. He ultimately bought the company that introduced the first successful sleeping car on a U.S. railroad.

By age 30, Carnegie had amassed business interests in iron works, steamers on the Great Lakes, railroads, and oil wells. He was subsequently involved in steel production, and built the Carnegie Steel Corporation into the largest steel manufacturing company in the world.

“Labor, capital, and ability are a three-legged stool… They are equal members of the great triple alliance which moves the industrial world.”

Map of pittsburgh area, showing locations of the carnegie steel mills, the city of pittsburgh witnessed andy carnegie’s meteoric rise from bobbin boy in a cotton mill, to telegraph operator, to railroad manager, and finally to steel industry titan. he moved to new york city in 1867, but the pittsburgh area, the site of his steel factories, was the recipient of many carnegie benefactions., birth of a philanthropist.

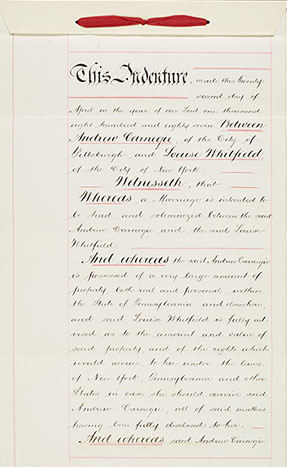

Andrew Carnegie’s philanthropic career began around 1870. Although he supported myriad projects and causes, he is best known for his gifts of free public library buildings, beginning in his native Dunfermline and ultimately extending throughout the English-speaking world, including the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand. In 1887, Carnegie married Louise Whitfield of New York City. She supported his philanthropy, and signed a prenuptial marriage agreement stating Carnegie’s intention of giving away virtually his entire fortune during his lifetime. Two years later he wrote The Gospel of Wealth, which boldly articulated his view of the rich as trustees of their wealth who should live without extravagance, provide moderately for their families, and use their riches to promote the welfare and happiness of others. This statement of his philosophy was read all over the world, and Carnegie’s intentions were widely praised.

“The man who dies thus rich dies disgraced.”

The gospel of wealth, board of trustees at the first carnegie corporation meeting, top row: left to right: henry s. pritchett, james bertram, charles l. taylor (president of the carnegie hero commission), robert franks. bottom row: william n. frew (the carnegie institute of pittsburg chairman of the board), robert s. woodward (president of the carnegie institution of washington), elihu root, andrew carnegie, his daughter margaret, his wife louise. the meeting took place in the drawing room of the carnegie home., wealthiest man in the world.

Andrew Carnegie sold his steel company to J.P. Morgan for $480 million in 1901. Retiring from business, Carnegie set about in earnest to distribute his fortune. In addition to funding libraries, he paid for thousands of church organs in the United States and around the world. Carnegie’s wealth helped to establish numerous colleges, schools, nonprofit organizations and associations in his adopted country and many others. His most significant contribution, both in money and enduring influence, was the establishment of several trusts or institutions bearing his name, including: Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh, the Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland, Carnegie Institution for Science, Carnegie Foundation (supporting the Peace Palace), Carnegie Dunfermline Trust, Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, and the Carnegie UK Trust.

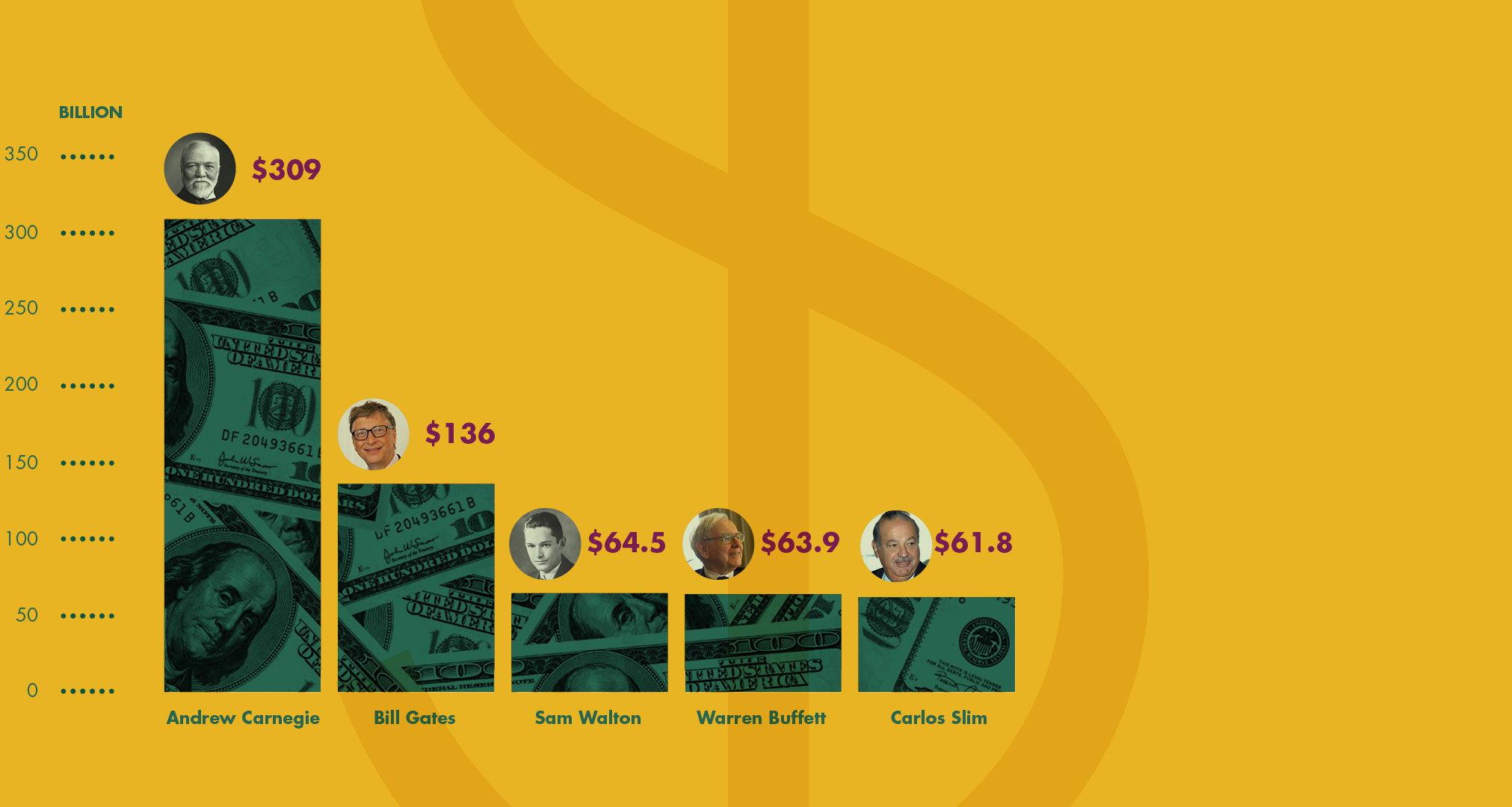

Andrew Carnegie’s Peak Wealth in Comparison to Modern-Day Billionaires

Reading Ahead

One of the most tangible examples of Andrew Carnegie’s philanthropy was the founding of 2,509 libraries in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Of these libraries, 1,679 were built in the United States. Carnegie spent over $55 million of his wealth on libraries alone, and he is often referred to as the “Patron Saint of Libraries.”

It is said that Carnegie had two main reasons for supporting libraries. First, he believed that in America, anyone with access to books and the desire to learn could educate him- or herself and be successful, as he had been. Second, Carnegie, an immigrant, felt America’s newcomers needed to acquire cultural knowledge of the country, which a library would help make possible.

Carnegie indicated it was the first reason that mattered most to him. Growing up working long hours in Pittsburgh, he had no access to formal education. However, a retired merchant, Colonel Anderson, loaned books from his small library to local boys, including Carnegie. As he later wrote in praise of Anderson, “This is but a slight tribute and gives only a faint idea of the depth of gratitude which I feel for what he did for me and my companions. It was from my own early experience that I decided there was no use to which money could be applied so productive of good to boys and girls who have good within them and ability and ambition to develop it, as the founding of a public library in a community.

“Whatever agencies for good may rise or fall in the future, it seems certain that the Free Library is destined to stand and become a never-ceasing foundation of good to all the inhabitants.”

An american four-in-hand in britain, reconstructing the reims library, the carnegie endowment for international peace, with financial assistance from the carnegie corporation of new york, sponsored reconstruction of various cultural landmarks in europe, destroyed in world war i. the architect max sainsaulieu used the library building in the united states as insiration for a new state-of-the-art building., giving and legacy.

In 1911 Andrew Carnegie established Carnegie Corporation of New York, which he dedicated to the “advancement and diffusion of knowledge and understanding.” It was the last philanthropic institution founded by Carnegie and was dedicated to the principles of “scientific philanthropy,” investing in the long-term progress of our society. Carnegie himself was the first president of the Corporation, which he endowed in perpetuity with his remaining fortune — $135 million — to be used principally to promote education and international peace. While his primary aim was to benefit the people of the United States, Carnegie later determined to use a portion of the funds for members of the British Overseas Commonwealth. For the Trustees of the Corporation, he chose his longtime friends and associates, giving them permission to adapt its programs to the times. “Conditions upon the earth inevitably change,” he wrote in the Deed of Gift, “hence no wise man will bind Trustees forever to certain paths, causes or institutions…. They shall best conform to my wishes by using their own judgment.”

Carnegie Organizations

Carnegie mellon university.

5000 Forbes Avenue Pittsburgh, PA 15213 Tel: (412) 268-2000 cmu.edu

Carnegie Institution for Science

1530 P Street NW Washington, DC 20005 Tel: (202) 387-6400 carnegiescience.edu

The Carnegie UK Trust

Andrew Carnegie House Pittencrieff Street Dunfermline Fife KY12 8AW carnegieuktrust.org.uk

Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh

4615 Forbes Avenue Pittsburgh, PA 15213 Tel: (412) 622-3333 carnegiemuseums.org

Carnegie Dunfermline Trust

Pittencrieff Street, Dunfermline Fife Scotland, UK KY12 8AW Tel: (+44) 01 38 74 97 89 andrewcarnegie.co.uk

The Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland

Pittencrieff Street, Dunfermline Fife Scotland, UK KY12 8AW Tel: (+44) 01 38 72 49 90 carnegie-trust.org

Carnegie Hero Fund Commission

436 7th Avenue, Suite 1101 Pittsburgh, PA 15219-1841 Telephone: 412-281-1302 carnegiehero.org

Carnegie Corporation of New York

437 Madison Avenue New York, NY 10022 Tel: (212) 371-3200 carnegie.org

Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh

4400 Forbes Avenue Pittsburgh, PA 15213 Tel: (412) 622-3114 clpgh.org

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

1779 Massachusetts Avenue NW Washington, DC 20036 Tel: (202) 483-7600 carnegieendowment.org

The Carnegie Hero Fund Trust

Pittencrieff Street, Dunfermline Fife Scotland, UK KY12 8AW Tel: (+44) 01 38 37 23 638 carnegiehero.org.uk

The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching

51 Vista Lane Stanford, CA 94305 Phone: 650-566-5100 Fax: 650-326-0278 carnegiefoundation.org

Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs

170 East 64th Street New York NY 10065 carnegiecouncil.org

Carnegie Foundation

Carnegie-Stichting Carnegieplein 2 2517 KJ Den Haag Tel: 070/3024242 Fax: 070/3024234 Email: [email protected] vredespaleis.nl

Carnegie Hall

881 Seventh Avenue New York, NY 10019 Tel: (212) 903-9600 carnegiehall.org

Champion for Peace

By the time of his death, Andrew Carnegie, despite his best efforts, had not been able to give away his entire fortune. He had distributed $350 million, but had $30 million left, which went into the Corporation’s endowment. Toward the end of his life, Carnegie, a pacifist, had a single goal: achieving world peace. He believed in the power of international laws and trusted that future conflicts could be averted through mediation. He supported the founding of the Peace Palace in The Hague in 1903, gave $10 million to found the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in 1910 to “hasten the abolition of international war,” and worked ceaselessly for the cause until the outbreak of World War I. He died, still brokenhearted about the failure of his efforts, in August 1919, two months after the signing of the Treaty of Versailles.

“Whoso wants to share the heroism of battle, let him join the fight against ignorance and disease and the mad idea that war is necessary.”

Flag of peace, presented to andrew carnegie in 1907 by the national society of the daughters of the american revolution, the flag was a “token of their affectionate appreciation of [his] bountiful labor of love in the holy cause of peace.” the new york peace society was founded in 1906 with andrew carnegie’s substantial financial support. he was elected its president in 1907., further reading, books written by andrew carnegie.

• An American Four-in-hand in Britain • Andrew Carnegie’s own story • Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie • The Empire of Business • The Gospel of Wealth essays and other writings • A League of Peace: A Rectoral address delivered to the students in the University of St. Andrews 17th October, 1905 • Triumphant Democracy or Fifty Years’ March of the Republic

Books Written About Andrew Carnegie

• Andrew Carnegie, David Nasaw, Penguin, 2006 • Andrew Carnegie, Joseph Frazier Wall, University of Pittsburgh Press, 1989 • Andrew Carnegie and The Rise of Big Business, Harold Livesay, Harper Collins, 1975 • The Andrew Carnegie Reader, Joseph Frazier Wall, Ed., University of Pittsburgh Press, 1992 • The Battle for Homestead, 1880–1892: Politics, Culture, and Steel, Paul Krause, University of Pittsburgh Press, 1992 • Homestead: The Glory and Tragedy of an American Steel Town, William Serrin, Vintage Books, 1993 • The Incorporation of America: Culture and Society in The Gilded Age, Alan Trachtenberg, Hill and Wang, 1982 • The Inside History of The Carnegie Steel Company: A Romance of Millions, James Howard Bridge, University of Pittsburgh Press, 1992 • The River Ran Red: Homestead 1892, David P. Demarest, Jr., Ed., University of Pittsburgh Press, 1992

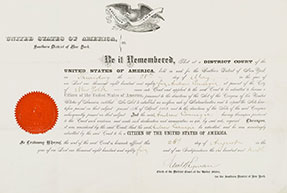

Historical Documents

Certificate of u.s. naturalization.

Download as PDF

Financial Records Journal

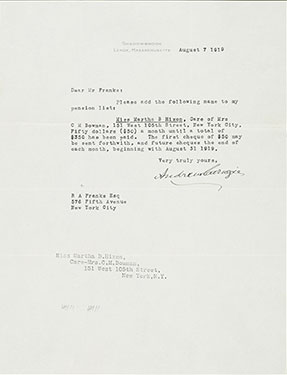

Pension Letter

Marriage Settlement

Stock Certificate

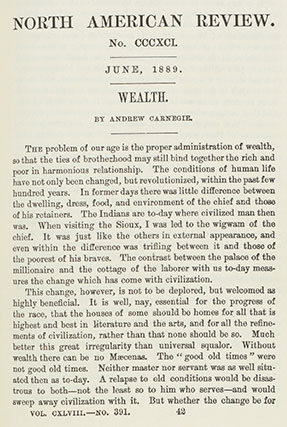

Gospel of Wealth

The Gospel of Wealth , Andrew Carnegie’s most famous essay, was written in 1889 and describes the responsibility of philanthropy by the new upper class of self-made rich. The central thesis of Carnegie’s essay is that the wealthy entrepreneur must assume the responsibility of distributing his fortune in a manner that assures that it will be put to good use, and not wasted on frivolous expenditure. The very existence of poverty in a capitalistic society, Carnegie believed, could be greatly alleviated by wealthy philanthropic businessmen and women. The Gospel of Wealth is an eloquent testament to the importance of charitable giving for the public good.

Citation: Andrew Carnegie. 1889

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

How to Write the Carnegie Mellon University Essays 2023-2024

Tucked away in Steelers country, otherwise known as Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, lies the 153 acre campus of Carnegie Mellon University. CMU is home to just under 7,000 undergraduate students enrolled across its seven schools and colleges.

Priding itself on copious opportunities as a research university, as well as the achievements of its student body and alumni, Carnegie Mellon offers students the opportunity to pursue real-world solutions alongside award-winning faculty across all disciplines. In fact, CMU is consistently ranked in the top 30 universities and is considered one of the very best for computer science.

As part of the application process, prospective students are required to respond to three 300-word prompts, and one optional 150-word prompt. However, students shouldn’t look at the supplements as a chore. As the admission process for CMU becomes more selective, its supplemental essays provide an increasingly vital opportunity for you to differentiate yourself from the pack. Keep reading for our suggestions on how to tackle this year’s supplemental responses.

Read these Carnegie Mellon essay examples to inspire your own writing.

Carnegie Mellon University Supplemental Essay Prompts

Prompt 2 (required): Many students pursue college for a specific degree, career opportunity or personal goal. Whichever it may be, learning will be critical to achieve your ultimate goal. As you think ahead to the process of learning during your college years, how will you define a successful college experience? (300 words)

Prompt 3 (required): Consider your application as a whole. What do you personally want to emphasize about your application for the admission committee’s consideration? Highlight something that’s important to you or something you haven’t had a chance to share. Tell us, don’t show us (no websites please). (300 words)

Prompt 4 (optional): When it comes to deciding whether to submit standardized test scores, occasionally applicants want us to better understand the individual context of their decision. If you’d like to take advantage of this opportunity, please share any information about your decision here. This is an optional question for those who may want to provide additional context for consideration. (150 words)

Prompt 1 (Required)

Most students choose their intended major or area of study based on a passion or inspiration that’s developed over time – what passion or inspiration led you to choose this area of study (300 words).

Many schools require a “ Why This Major? ” prompt to assess your interest in your chosen area of study. This prompt asks this standard question, but with a particular emphasis on how past experiences have influenced your desire to study your prospective major, rather than what you hope to achieve by studying it.

A successful execution of this prompt will:

- Elaborate on the path that led you to choose your major

- Show the admissions committee why you deserve to pursue this major at their school.

The latter doesn’t necessarily need to be explicit. Instead, reflect on your path in a way that demonstrates intellectual curiosity, creativity, and passion for what it is you hope to pursue at the college level.

You can take a few different approaches when answering this prompt. The first is a narrative arc or anecdote. Think back to a salient moment in which you realized the importance of your prospective major to you. Perhaps you were in a robotics competition and after weeks of laboring, your robot finally moved. Maybe that was the moment when you knew for sure that this was the path you needed to pursue. This response could start something like this:

“I couldn’t believe my ears the first time Sparky whirred to life. After weeks of toiling, I watched him wheel across the classroom floor, rhythmically belting out the tell-tale beeps I had coded him to make with each turn.”

Here’s what telling that story does. First, it shows tenacity—even after weeks of failure, you didn’t give up. Second, it shows innovation. And third, CMU just happens to be known for offering a robotics major, so even without being explicit, you just told the admissions committee exactly why you belong at CMU!

Stories are a great method for drawing in your reader and creating pathos. The trick, however, is to not get so caught up in the narration that you fill your 300 words without actually saying anything. If you’re going the anecdote route, ask yourself the following questions:

- Did I answer the prompt?

- Does the story I just told show why I’m passionate about the major I’ve chosen?

- Have I demonstrated that CMU is the right place for me?

Don’t say you want to pursue a major in underwater basket-weaving if CMU doesn’t offer that (just an example, but you get the idea).

Do mention, either briefly or implicitly, how CMU would allow you to continue pursuing and developing your passion.

Let’s move on to the second method of answering this prompt, we’ll refer to it as the chronological method.

You may not be able to fully answer the prompt with just one moment or story. That’s okay! An alternative is to briefly list key moments, progressions, or accomplishments leading up to your decision. Here’s an example:

“From writing short stories as a seven year old to winning my first prose contest in high school, creative writing has been a part of my life for as long as I can remember.”

Unlike the narrative arc method, this example is neither a story nor a specific event. Instead, it shows how creative writing has been pivotal to your life for years. Though arguably less compelling than a story, this method has the bonus of demonstrating growth, long-term commitment, and development. Being that CMU is one of the only universities to offer a BA in creative writing, it also shows why you’d be applying.

This same method will work if you choose to talk about who or what inspired you. However, this comes with a warning. If you choose to talk about a person or work that inspired you, ensure that you don’t only write about said person or work. If the admissions committee learns more about the Pulitzer prize winner whose work inspired you than they do about you and your work, reassess whether this is a beneficial inclusion.

Prompt 2 (Required)

Many students pursue college for a specific degree, career opportunity or personal goal. whichever it may be, learning will be critical to achieve your ultimate goal. as you think ahead to the process of learning during your college years, how will you define a successful college experience (300 words).

This essay provides you with the perfect opportunity to demonstrate your passion for CMU and your understanding of its available opportunities. While the prompt doesn’t explicitly ask you “ Why This School? ,” it does asks you to discuss two things:

- The explicit question: what do you hope to accomplish in your undergraduate degree program?

- The implicit question: how is CMU uniquely equipped to help you realize those goals?

While the explicit question is definitely important to address, tackling the implicit question through the use of specific examples and thoughtful reflection will allow your essay to stand out among other applicants.

Think about your expectations for your college experience. Perhaps it’s really important to you to have substantive research experiences under your belt as an undergraduate student, since you want to pursue an MD-PhD.

What specific projects and topics might you be looking to pursue? How will studying at Carnegie Mellon enable you to pursue these projects and ideas? Briefly reflecting on Carnegie Mellon’s financial investment in undergraduate research as you answer this prompt, for example, can help demonstrate both your familiarity with the university and its resources as well as your alignment with its culture and values.

Perhaps you are hoping to apply your textbook knowledge within a broader context through community engagement. CMU empowers its students to tackle problems and issues that matter in hopes that its students will be leaders in improving the world around them. Consequently, discussing your interest in taking your learning outside of the classroom with the support of the Office of Student Leadership, Involvement, and Civic Engagement would not only speak to your metrics regarding a successful college experience, but also show how you might add to the CMU community as an undergraduate and beyond.

Whatever your goals may be, ensure that your essay has a clear “why.” Rather than simply stating that you want to join the college orchestra, explain that you want to do so because playing the cello in high school has allowed you to form meaningful relationships with other musicians and life mentors. Playing music has taught you the importance of teamwork and dedication, and you want to continue cultivating these relationships and skills in college.

The point here isn’t to draft a college bucket list, but instead to reflect on what elements of the college experience, outside of the day-to-day coursework, you’re looking forward to as a prospective student. Be true to yourself and your goals, and speak honestly about what it is you hope to accomplish as an undergraduate student at CMU.

Prompt 3 (Required)

Consider your application as a whole. what do you personally want to emphasize about your application for the admission committee’s consideration highlight something that’s important to you or something you haven’t had a chance to share. tell us, don’t show us (no websites please). (300 words).

This is your chance to show the admissions committee exactly what makes you special. Within the confines of the word limit, the options are endless. But don’t get bogged down by the possibilities!

So, how do you know what’s worth writing about?

Is there something you mentioned on your Common App that you feel the need to elaborate? The topic of this essay should not be even remotely similar to the subject of your personal statement. Think of your essays as a portfolio; they should be complementary without being redundant. For example, if your passions are science and wildlife, and your personal statement is about wildlife, make this prompt about science.

Is there something you haven’t been able to mention anywhere else that you’re dying to talk about? Let your personality shine through. Whether your passion of choice is volunteering with animals, taking apart computers, or almost anything else, it can have a place in this prompt. However, it shouldn’t be so random that it doesn’t say anything about you as an applicant.

Here’s a good example: “I buy postcards but never send them. My collection is from all over the world, ranging from Tanzania to New Caledonia. Each postcard tied to a travel story. The postcard of the Dolomites? That’s where I went on a 3-day backpacking trip with my family. The postcard with a sketch of takoyaki? I bought it because I wanted to remember the delicious meals my Japanese host family made me.”

See how this paints a picture of a student eager to learn and expand their horizons?

Now here’s a bad example: “I like watching Netflix in my free time.”

Does that tell the admissions officers something that helps them envision a contributing member of the CMU community? Not particularly.

Basically, use this as an opportunity to show your personality and your passion. Narrow in on something pivotal to your identity, and make sure it still shows CMU why you’re a great fit. If you have a story, accomplishment, or passion that shows you possess drive, an entrepreneurial spirit, or a similar embodiment of the values of CMU, here’s the place to show it. However, if you’ve already said it in another CMU essay or in your personal statement, don’t say it again!

So, there you have it for the required prompts! At the end of the day, you want all three essays to answer the prompts in a way that screams ‘you.’ The more of your personality in the essays, the better. Whether you’re reflecting on how your first broken bone led you to pursue medicine or discussing how synchronized swimming deepened your capacity for empathy and collaboration, remember to always be open and honest as you tell your story.

Prompt 4 (optional)

When it comes to deciding whether to submit standardized test scores, occasionally applicants want us to better understand the individual context of their decision. if you’d like to take advantage of this opportunity, please share any information about your decision here. this is an optional question for those who may want to provide additional context for consideration. (150 words).

This prompt applies to those who have either opted out of taking standardized tests, have chosen not to submit their scores, or have other circumstances surrounding their scores. Here, Carnegie Mellon gives applicants a chance to explain the reasons behind these circumstances.

Standardized testing disadvantages many groups of people, especially low-income students. With the pandemic, it’s also likely that students won’t have had as many opportunities to take tests, if at all. Students may also have other extenuating life experiences or circumstances that affected their ability to take or do well on the test.

Whatever your circumstances, Carnegie Mellon gives you 150 words, so avoid including long anecdotes or excess background information. State your reason(s) clearly and concisely, in a matter-of-fact way. This section might be optional, but you should treat it with the same care as your answers to the other prompts. Your writing should carry the same level of poise as your other responses.

There are some cases, however, where you might choose to forego this prompt. If you chose not to submit a score because you underperformed, and there wasn’t necessarily an extenuating circumstance, then you could leave your response blank. If you performed poorly and didn’t submit your score because you were recovering from a concussion, then you might respond to this essay. Otherwise, telling the admissions office that you got a low score defeats the purpose of not submitting your score.

Where to Get Your Carnegie Mellon Essays Edited

Do you want feedback on your CMU essays? After rereading your essays countless times, it can be difficult to evaluate your writing objectively. That’s why we created our free Peer Essay Review tool , where you can get a free review of your essay from another student. You can also improve your own writing skills by reviewing other students’ essays.

If you want a college admissions expert to review your essay, advisors on CollegeVine have helped students refine their writing and submit successful applications to top schools. Find the right advisor for you to improve your chances of getting into your dream school!

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

- International Peace and Security

- Higher Education and Research in Africa

- Andrew Carnegie Fellows

- Great Immigrants

- Carnegie Medal of Philanthropy

- Reporting Requirements

- Modification Requests

- Communications FAQs

- Grants Database

- Philanthropic Resources

- Grantee FAQs

- Grantmaking Highlights

- Past Presidents

The Gospel of Wealth

- Other Carnegie Organizations

- Andrew Carnegie’s Story

- Governance and Policies

- Media Center

Newly edited and annotated 1889 | Essay

The Scottish-born industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie (1835–1919) was one of the titans of America’s Gilded Age. He was also a prolific author, writing hundreds of speeches, articles, pamphlets, and letters to the editor, as well as seven books, including an Autobiography (published posthumously in 1920). Proud of his pen, Carnegie is today perhaps most celebrated as the author of a pair of articles first published in the North American Review in 1889, which together have come to be known as The Gospel of Wealth . Here, Carnegie boldly articulated his view of the rich as mere trustees of their wealth who should live unostentatiously, provide moderately for their families, and use their fortunes to promote the “general good.” He goes on to suggest some “best uses” to which the millionaire can devote his wealth (universities, libraries, medical institutions, public parks, and more). The Gospel of Wealth caused quite a stir on both sides of the Atlantic, not least for its now famous declaration that “The man who dies thus rich dies disgraced.”

Andrew Carnegie. The Gospel of Wealth. New York: Carnegie Corporation of New York, 2017 (first published in 1889).

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Andrew Carnegie

By: History.com Editors

Updated: February 9, 2021 | Original: November 9, 2009

Scottish-born Andrew Carnegie (1835-1919) was an American industrialist who amassed a fortune in the steel industry then became a major philanthropist. Carnegie worked in a Pittsburgh cotton factory as a boy before rising to the position of division superintendent of the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1859.

While working for the railroad, he invested in various ventures, including iron and oil companies, and made his first fortune by the time he was in his early 30s. In the early 1870s, he entered the steel business, and over the next two decades became a dominant force in the industry. In 1901, he sold the Carnegie Steel Company to banker John Pierpont Morgan for $480 million. Carnegie then devoted himself to philanthropy, eventually giving away more than $350 million.

Andrew Carnegie: Early Life and Career

Andrew Carnegie, whose life became a rags-to-riches story, was born into modest circumstances on November 25, 1835, in Dunfermline, Scotland, the second of two sons of Will, a handloom weaver, and Margaret, who did sewing work for local shoemakers. In 1848, the Carnegie family (who pronounced their name “carNEgie”) moved to America in search of better economic opportunities and settled in Allegheny City (now part of Pittsburgh), Pennsylvania . Andrew Carnegie, whose formal education ended when he left Scotland, where he had no more than a few years’ schooling, soon found employment as a bobbin boy at a cotton factory, earning $1.20 a week.

Did you know? During the U.S. Civil War, Andrew Carnegie was drafted for the Army; however, rather than serve, he paid another man $850 to report for duty in his place, a common practice at the time.

Ambitious and hard-working, he went on to hold a series of jobs, including messenger in a telegraph office and secretary and telegraph operator for the superintendent of the Pittsburgh division of the Pennsylvania Railroad. In 1859, Carnegie succeeded his boss as railroad division superintendent. While in this position, he made profitable investments in a variety of businesses, including coal, iron and oil companies and a manufacturer of railroad sleeping cars.

After leaving his post with the railroad in 1865, Carnegie continued his ascent in the business world. With the U.S. railroad industry then entering a period of rapid growth, he expanded his railroad-related investments and founded such ventures as an iron bridge building company (Keystone Bridge Company) and a telegraph firm, often using his connections to win insider contracts. By the time he was in his early 30s, Carnegie had become a very wealthy man.

Andrew Carnegie: Steel Magnate

In the early 1870s, Carnegie co-founded his first steel company, near Pittsburgh. Over the next few decades, he created a steel empire, maximizing profits and minimizing inefficiencies through ownership of factories, raw materials and transportation infrastructure involved in steel making. In 1892, his primary holdings were consolidated to form Carnegie Steel Company.

The steel magnate considered himself a champion of the working man; however, his reputation was marred by the violent Homestead Strike in 1892 at his Homestead, Pennsylvania, steel mill. After union workers protested wage cuts, Carnegie Steel general manager Henry Clay Frick (1848-1919), who was determined to break the union, locked the workers out of the plant.

Andrew Carnegie was on vacation in Scotland during the strike, but put his support in Frick, who called in some 300 Pinkerton armed guards to protect the plant. A bloody battle broke out between the striking workers and the Pinkertons, leaving at least 10 men dead. The state militia then was brought in to take control of the town, union leaders were arrested and Frick hired replacement workers for the plant. After five months, the strike ended with the union’s defeat. Additionally, the labor movement at Pittsburgh-area steel mills was crippled for the next four decades.

In 1901, banker John Pierpont Morgan (1837-1913) purchased Carnegie Steel for some $480 million, making Andrew Carnegie one of the world’s richest men. That same year, Morgan merged Carnegie Steel with a group of other steel businesses to form U.S. Steel, the world’s first billion-dollar corporation.

READ MORE: Andrew Carnegie Claimed to Support Unions, But Then Destroyed Them in His Steel Empire

Andrew Carnegie: Philanthropist

After Carnegie sold his steel company, the diminutive titan, who stood 5’3”, retired from business and devoted himself full-time to philanthropy. In 1889, he had penned an essay, “The Gospel of Wealth,” in which he stated that the rich have “a moral obligation to distribute [their money] in ways that promote the welfare and happiness of the common man.” Carnegie also said, “The man who dies thus rich dies disgraced.”

Carnegie eventually gave away some $350 million (the equivalent of billions in today’s dollars), which represented the bulk of his wealth. Among his philanthropic activities, he funded the establishment of more than 2,500 public libraries around the globe, donated more than 7,600 organs to churches worldwide and endowed organizations (many still in existence today) dedicated to research in science, education, world peace and other causes.

Among his gifts was the $1.1 million required for the land and construction costs of Carnegie Hall, the legendary New York City concert venue that opened in 1891. The Carnegie Institution for Science, Carnegie Mellon University and the Carnegie Foundation were all founded thanks to his financial gifts. A lover of books, he was the largest individual investor in public libraries in American history.

Andrew Carnegie: Family and Final Years

Carnegie’s mother, who was a major influence in his life, lived with him until her death in 1886. The following year, the 51-year-old industrial baron married Louise Whitfield (1857-1946), who was two decades his junior and the daughter of a New York City merchant. The couple had one child, Margaret (1897-1990). The Carnegies lived in a Manhattan mansion and spent summers in Scotland, where they owned Skibo Castle, set on some 28,000 acres.

Carnegie died at age 83 on August 11, 1919, at Shadowbrook, his estate in Lenox, Massachusetts . He was buried at Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in North Tarrytown, New York.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Bookreader Item Preview

Share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

1,106 Views

9 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

For users with print-disabilities

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by Carrite on April 23, 2017

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

The Gospel Of Wealth

50 pages • 1 hour read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more. For select classroom titles, we also provide Teaching Guides with discussion and quiz questions to prompt student engagement.

Essay Analysis

Key Figures

Symbols & Motifs

Literary Devices

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Discussion Questions

Summary and Study Guide

Summary: “the gospel of wealth”.

Andrew Carnegie wrote “The Gospel of Wealth” in June 1889. Carnegie begins his treatise by identifying what he sees as the most significant problem of modern-day times: “the proper administration of wealth, so that the ties of brotherhood may still bind together the rich and poor in harmonious relationship” (1).

Carnegie mentions that, in the past, “there was little difference” (1) between the living situations of a leader of a community and those of the members of the community. To prove his point, Carnegie writes about a memory of “visiting the Sioux” (1); during this visit, he noticed that the residence of the chief looked “just like the others in external appearance” (1). Carnegie compares the living situations of the Sioux with the difference between “the palace of the millionaire and the cottage of the laborer with us to-day” (1) to demonstrate the changes in American society that have taken place over the years. These changes are not negative, but “essential for the progress of the [human] race” (2). After all, Carnegie points out, “the ‘good old times’ were not good old times” (2) and besides, “whether the change be for good or ill, it is upon us, beyond our power to alter” (2).

Get access to this full Study Guide and much more!

- 7,650+ In-Depth Study Guides

- 4,850+ Quick-Read Plot Summaries

- Downloadable PDFs

According to Carnegie, the explanation for the change can be found in “the manufacture of product” (3), which requires a very different process now than before, when “[t]he master and apprentice worked side by side, the latter living with the master, and therefore subject to the same conditions” (3). Now that products can be manufactured more quickly and easily thanks to industrialization, “[t]he poor enjoy what the rich could not before afford” (4). The price society pays for this change is steep: because the employee and the employer no longer work together, and, in fact, because “[a]ll intercourse between them is at an end” (5), friction between the two often results.

Similar to the price society pays for cheaper goods is the “price which society pays for the law of competition” (6). Despite the costly nature of competition, “while the law may be sometimes hard for the individual, it is best for the race, because it insures the survival of the fittest in every department” (6). At least, the most talented people “soon create capital” (6), and some of these people “become interested in firms or corporations using millions” (6); they soon accumulate wealth, as it is essential that “successful operation[…]should be thus far profitable” (6).

The SuperSummary difference

- 8x more resources than SparkNotes and CliffsNotes combined

- Study Guides you won ' t find anywhere else

- 100+ new titles every month

Carnegie points out that objectors to this capitalist system, such as “the Socialist or Anarchist who seeks to overturn present conditions” (7), compromise civilization as a whole when they challenge “the right of the laborer to his hundred dollars in the savings bank and equally the legal right of the millionaire to his millions” (7). The individualism that movements like communism seek to destroy is “what is practicable now” (7). More importantly, the “destruction of the highest existing type of man” (7) means the destruction of “the highest results of human experience, the soil in which society so far has produced the best fruit” (7). With this assertion in mind, Carnegie is certain that “the only question with which we have to deal” (8) is this one: “What is the proper mode of administering wealth after the laws upon which civilization is founded have thrown it into the hands of the few?” (8).

Carnegie specifies three ways excess wealth can be put to use. The first concerns the case of inheritance, when the wealth is left to surviving family members, which Carnegie considers to be “the most injudicious” (9). He uses the examples of European traditions of inheritance that fail “to maintain the status of an hereditary class” (9) to support his argument, believing the practice to be a form of “misguided affection” (9) towards one’s children. There is a possibility that “millionaires’ sons unspoiled by wealth” (10) will do good with the money they have not earned, but sadly, such sons “are rare” (10). Besides, if a wealthy man is honest with himself, he will “admit to himself that it is not the welfare of the children, but family pride, which inspires these enormous legacies” (10).

The second way wealth can be spent is by “leaving wealth at death for public uses” (11), which is only useful “provided a man is content to wait until he is dead before it becomes of much good in the world” (11). Carnegie believes that these attempts at performing “posthumous good” (11) can often be thwarted and “become only monuments of his folly” (11). Even worse perhaps, “[m]en who leave vast sums in this way may fairly be thought men who would not have left it at all, had they been able to take it with them” (11).

Carnegie observes that the heavy taxes levied on large inheritances in both the United States and in Britain “is a cheering indication of the growth of a salutory change in public opinion” (12). These taxes are proof of the state’s “condemnation of the selfish millionaire’s unworthy life” (12). In fact, “nations should go much further in this direction” and “such taxes should be graduated” until the “millionaire’s hoard” becomes the property of the state (13). This approach “would work powerfully to induce the rich man to the administration of wealth during his life” (13), which is the most beneficial option for society.

Only one of Carnegie’s identified three ways of using excess wealth is acceptable to him, and “in this we have the true antidote for the temporary unequal distribution of wealth, the reconciliation of rich and poor” (14). Carnegie promises “an ideal state, in which the surplus wealth of the few will become, in the best sense the property of the many” (14). His solution is far superior to the distribution of the money “in small quantities among the people, which would have been wasted in the indulgence of appetite” (15). The solution Carnegie proposes is best exemplified by Mr. Cooper’s personally-funded Cooper Institute and by “Mr. Tilden’s bequest of five millions of dollars for a free library” (16). Though it would have been better had Mr. Tilden “devoted the last years of his own life to the proper administration of this immense sum” (16), in order to avoid interference from other interested parties, the benefit of the library to the people is more than if the “millions been allowed to circulate in small sums through the hands of the masses” (16).

Because rich men are more fortunate than most others, they should be grateful for their opportunities to “organize benefactions from which the masses of their fellows will derive lasting advantage, and thus dignify their own lives” (17). By living by the example of Christ, “laboring for the good of our fellows” (17), such men will fulfill “the duty of the man of Wealth” (18). Living unpretentiously and providing for his dependents are essential, but the rich man must also “consider all surplus revenues which come to him simply as trust funds” (18), revenues that must “produce the most beneficial results for the community” (18). In this way, the man of wealth becomes “agent and trustee for his poorer brethren” (18), serving them with “his superior wisdom […] doing for them better than they would or could do for themselves” (18).

Though the process of deciding on appropriate amounts of money to leave family members is challenging, wealthy men can apply “[t]he rule in regard to good taste in the dress of men or women,” as “[w]hatever makes one conspicuous offends the canon” (19). When putting surplus wealth to use or when determining how much to bequeath to heirs, avoiding the appearance of extravagance is crucial.

Research foundations like the Cooper Institute and the prospect of a public library are both examples of “the best uses to which surplus wealth can be put” (20). After all, Carnegie believes that “one of the serious obstacles to the improvement of our race is indiscriminate charity” (20), which only “encourage[s] the slothful, the drunken, the unworthy” (20). This kind of spending he compares to the act of throwing money into the sea. To reinforce this point, Carnegie describes the selfishness of a writer who gave a man on the street money, though “[the writer] had every reason to suspect that it would be spent improperly” (20). This writer “only gratified his own feelings, [and] saved himself from annoyance” (20) when he gave the man money, a decision that Carnegie describes as “probably one of the most selfish and very worst actions of his life” (20).

When giving money to charity, “the main consideration would be to help those who will help themselves” (21). Carnegie is certain that no one benefits from indiscriminate assistance; in fact, those who are “worthy of assistance, except in rare cases, seldom require assistance” (21). Carnegie goes on to define the true social reformer as someone who is careful “not to aid the unworthy” (21) and thereby rewards vice.

Rich men can follow the example of such tycoons as “Peter Cooper, Enoch Pratt of Baltimore, Mr. Pratt of Brooklyn, Senator Stamford and others” (22), all of whom understand that their most useful contributions to society take the form of “parks, and means of recreation, by which men are helped in body and mind; works of art, certain to give pleasure and improve the public taste, and public institutions of various kinds, which will improve the general condition of the people” (22).

This solution solves “the problem of Rich and Poor” (23), allowing individualism to flourish while the millionaires use their money wisely, “administering it for the community far better than it could or would have done for itself” (23). Carnegie predicts that “the man who dies leaving behind many millions of available wealth, which was his to administer during life, will pass away ‘unwept, unhonored, and unsung’” (23). With this prediction, Carnegie concludes his treatise, calling his piece “the true Gospel concerning Wealth” (24) that will “bring Peace on earth, among men Good-Will” (24).

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie was a self-made steel tycoon and one of the wealthiest businessmen of the 19th century. He later dedicated his life to philanthropic endeavors.

(1835-1919)

Who Was Andrew Carnegie?

After moving to the United States from Scotland, Andrew Carnegie worked a series of railroad jobs. By 1889, he owned Carnegie Steel Corporation, the largest of its kind in the world. In 1901 he sold his business and dedicated his time to expanding his philanthropic work, including the establishment of Carnegie-Mellon University in 1904.

Andrew Carnegie was born on November 25, 1835, in Dunfermline, Fife, Scotland. Although he had little formal education, Carnegie grew up in a family that believed in the importance of books and learning. The son of a handloom weaver, Carnegie grew up to become one of the wealthiest businessmen in America.

At the age of 13, in 1848, Carnegie came to the United States with his family. They settled in Allegheny, Pennsylvania, and Carnegie went to work in a factory, earning $1.20 a week. The next year he found a job as a telegraph messenger. Hoping to advance his career, he moved up to a telegraph operator position in 1851. He then took a job at the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1853. He worked as the assistant and telegrapher to Thomas Scott, one of the railroad's top officials. Through this experience, he learned about the railroad industry and about business in general. Three years later, Carnegie was promoted to superintendent.

Steel Tycoon

While working for the railroad, Carnegie began making investments. He made many wise choices and found that his investments, especially those in oil, brought in substantial returns. He left the railroad in 1865 to focus on his other business interests, including the Keystone Bridge Company.

By the next decade, most of Carnegie's time was dedicated to the steel industry. His business, which became known as the Carnegie Steel Company, revolutionized steel production in the United States. Carnegie built plants around the country, using technology and methods that made manufacturing steel easier, faster and more productive. For every step of the process, he owned exactly what he needed: the raw materials, ships and railroads for transporting the goods, and even coal fields to fuel the steel furnaces.

This start-to-finish strategy helped Carnegie become the dominant force in the industry and an exceedingly wealthy man. It also made him known as one of America's "builders," as his business helped to fuel the economy and shape the nation into what it is today. By 1889, Carnegie Steel Corporation was the largest of its kind in the world.

Some felt that the company's success came at the expense of its workers. The most notable case of this came in 1892. When the company tried to lower wages at a Carnegie Steel plant in Homestead, Pennsylvania, the employees objected. They refused to work, starting what has been called the Homestead Strike of 1892. The conflict between the workers and local managers turned violent after the managers called in guards to break up the union. While Carnegie was away at the time of strike, many still held him accountable for his managers' actions.

Philanthropy

In 1901, Carnegie made a dramatic change in his life. He sold his business to the United States Steel Corporation, started by legendary financier J.P. Morgan. The sale earned him more than $200 million. At the age of 65, Carnegie decided to spend the rest of his days helping others. While he had begun his philanthropic work years earlier by building libraries and making donations, Carnegie expanded his efforts in the early 20th century.

Carnegie, an avid reader for much of his life, donated approximately $5 million to the New York Public Library so that the library could open several branches in 1901. Devoted to learning, he established the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh, which is now known as Carnegie-Mellon University in 1904. The next year, he created the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching in 1905. With his strong interest to peace, he formed the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in 1910. He made numerous other donations, and it is said that more than 2,800 libraries were opened with his support.

Besides his business and charitable interests, Carnegie enjoyed traveling and meeting and entertaining leading figures in many fields. He was friends with Matthew Arnold, Mark Twain, William Gladstone, and Theodore Roosevelt. Carnegie also wrote several books and numerous articles. His 1889 article "Wealth" outlined his view that those with great wealth must be socially responsible and use their assets to help others. This was later published as the 1900 book The Gospel of Wealth .

Carnegie died on August 11, 1919, in Lenox, Massachusetts, at the age of 83.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Andrew Carnegie

- Birth Year: 1835

- Birth date: November 25, 1835

- Birth City: Dunfermline, Scotland

- Birth Country: United Kingdom

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Andrew Carnegie was a self-made steel tycoon and one of the wealthiest businessmen of the 19th century. He later dedicated his life to philanthropic endeavors.

- Business and Industry

- Astrological Sign: Sagittarius

- Death Year: 1919

- Death date: August 11, 1919

- Death State: Massachusetts

- Death City: Lenox

- Death Country: United States

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Andrew Carnegie Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/business-leaders/andrew-carnegie

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: May 26, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 3, 2014

- People who are unable to motivate themselves must be content with mediocrity, no matter how impressive their other talents.

- The man who dies thus rich dies disgraced.

- I cannot tell you how proud I was when I received my first week's own earnings. One dollar and twenty cents made by myself and given to me because I had been of some use in the world!

- I always liked the idea of being my own master, of manufacturing something and giving employment to many men.

- In bestowing charity, the main consideration should be to help those who will help themselves.

- I should as soon leave to my son a curse as the almighty dollar.

- No party is so foolish as to nominate for the presidency a rich man, much less a millionaire. Democracy elects poor men.

- There is always room at the top in every pursuit. Concentrate all your thought and energy upon the performance of your duties. Put all your eggs into one basket and then watch that basket.

- Do not make riches, but usefulness, your first aim.

- I congratulate poor young men upon being born to that ancient and honorable degree which renders it necessary that they should devote themselves to hard work.

- The aim of the millionaire should be, first, to set an example of modest, unostentatious living, shunning display and extravagances.

Philanthropists

Tyler Childers

Prince William

Michelle Obama

Oprah Winfrey

Madam C.J. Walker

Alec Baldwin

Prince Harry

Jimmy Carter

Rosalynn Carter

Dolly Parton

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Guest Essay

The West Doesn’t Understand How Much Russia Has Changed

By Alexander Gabuev

Mr. Gabuev, the director of the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center, wrote from Berlin.

Vladimir Putin’s trip to Beijing this week, where he will meet with Xi Jinping and top Chinese officials, is another clear demonstration of the current closeness between Russia and China.

Yet many in the West still want to believe that their alliance is an aberration, driven by Mr. Putin’s emotional anti-Americanism and his toxic fixation on Ukraine. Once Mr. Putin and his dark obsessions are out of the picture, the thinking goes , Moscow will seek to rebuild ties with the West — not least because the bonds between Russia and China are shallow, while the country has centuries of economic and cultural dependence on Europe.

This wishful view, however appealing, overlooks the transformation of Russia’s economy and society. Never since the fall of the Soviet Union has Russia been so distant from Europe, and never in its entire history has it been so entwined with China. The truth is that after two years of war in Ukraine and painful Western sanctions, it’s not just Mr. Putin who needs China — Russia does, too.

China has emerged as Russia’s single most important partner, providing a lifeline not only for Mr. Putin’s war machine but also for the entire embattled economy. In 2023, Russia’s trade with China hit a record $240.1 billion, up by more than 60 percent from prewar levels, as China accounted for 30 percent of Russia’s exports and nearly 40 percent of its imports.

Before the war, Russia’s trade with the European Union was double that with China; now it’s less than half. The Chinese yuan, not the dollar or the euro, is now the main currency used for trade between the two countries, making it the most traded currency on the Moscow stock exchange and the go-to instrument for savings.

This economic dependence is filtering into everyday life. Chinese products are ubiquitous and over half of the million cars sold in Russia last year were made in China. Tellingly, the top six foreign car brands in Russia are now all Chinese, thanks to the exodus of once dominant Western companies. It’s a similar story in the smartphone market, where China’s Xiaomi and Tecno have eclipsed Apple and Samsung, and with home appliances and many other everyday items.

These shifts are tectonic. Even in czarist times, Russia shipped its commodities to Europe and relied on imports from the West of manufactured goods. Russia’s oligarchs, blacklisted by most Western countries, have had to adapt to the new reality. Last month, the businessman Vladimir Potanin, whose fortune is estimated at $23.7 billion, announced that his copper and nickel empire would reorient toward China, including by moving production facilities into the country. “If we’re more integrated into the Chinese economy,” he said, “we’ll be more protected.”

From the economy, education follows. Members of the Russian elite are scrambling to find Mandarin tutors for their kids, and some of my Russian contacts are thinking about sending their children to universities in Hong Kong or mainland China now that Western universities are much harder to reach. This development is more than anecdotal. Last year, as China opened up after the pandemic, 12,000 Russian students went to study there — nearly four times as many than to the United States.

This reorientation from West to East is also visible among the middle class, most notably in travel. There are now, for example, five flights a day connecting Moscow and Beijing in under eight hours, with a return ticket costing about $500. By contrast, getting to Berlin — one of many frequent European weekend destinations for middle-class Russians before the war — can now take an entire day and cost up to twice as much.

What’s more, European cities are being replaced as Russian tourist destinations by Dubai, Baku in Azerbaijan and Istanbul, while business trips are increasingly to China, Central Asia or the Gulf . Locked out of much of the West, which scrapped direct flights to Russia and significantly reduced the availability of visas for Russians, middle-class Russians are going elsewhere.

Intellectuals are turning toward China, too. Russian scientists are beginning to work with and for Chinese companies, especially in fields such as space exploration, artificial intelligence and biotech . Chinese cultural influence is also growing inside Russia. With Western writers like Stephen King and Neil Gaiman withdrawing the rights to publish their work in Russia, publishers are expanding their rosters of Chinese works. Supported by lavish grants for translators from the Chinese government, this effort is set to bring about a boom in Chinese books.

Chinese culture will not replace Western culture as Russians’ main reference point any time soon. But a profound change has taken place. From the other side of the Iron Curtain, Europe was seen as a beacon of human rights, prosperity and technological development, a space that many Soviet citizens aspired to be part of.

Now a growing number of educated Russians, on top of feeling bitterness toward Europe for its punitive sanctions, see China as a technologically advanced and economically superior power to which Russia is ever more connected. With no easy way back to normal ties with the West, that’s unlikely to change anytime soon.

In his dystopian novel “ Day of the Oprichnik ,” Vladimir Sorokin describes a deeply anti-Western Russia of 2028 that survives on Chinese technology while cosplaying the medieval brutality of Ivan the Terrible’s era. With every passing day, this unsettling and foresighted novel — published in 2006 as a warning to Russia about the direction of travel under Mr. Putin — reads more and more like the news.

Alexander Gabuev ( @AlexGabuev ) is the director of the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center in Berlin.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips . And here’s our email: [email protected] .

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook , Instagram , TikTok , WhatsApp , X and Threads .

Stephen Wertheim Returns: Restraint and Retrenchment Security Dilemma

On this episode of Security Dilemma, we have our first return guest on the show - Dr. Stephen Wertheim. Patrick Carver Fox and John Allen Gay joined him at his offices at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace to discuss Ukraine, NATO, restraint, "retrenchment" and the foreign policy implications of the 2024 elections. After the release of this episode, Dr. Wertheim released an essay in Foreign Policy on Ukraine, so you can check that out as well! Tune in for a great episode!

- Episode Website

- More Episodes

- The John Quincy Adams Society

Top Podcasts In Government

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The Gospel of Wealth by Andrew Carnegie. Originally titled simply "Wealth" and published in the North American Review in June 1889, Andrew Carnegie's essay "The Gospel of Wealth" is considered a foundational document in the field of philanthropy. Carnegie believed in giving wealth away during one's lifetime, and this essay includes ...

Carnegie portrait (detail) in the National Portrait Gallery "Wealth", more commonly known as "The Gospel of Wealth", is an article written by Andrew Carnegie in June of 1889 that describes the responsibility of philanthropy by the new upper class of self-made rich.The article was published in the North American Review, an opinion magazine for America's establishment.

In his essay "Wealth," published in the North American Review in 1889, industrialist Andrew Carnegie argued that individual capitalists were duty bound to play a broader cultural and social role and thus improve the world. Carnegie's essay later became famous under the title "The Gospel of Wealth," and in 1908, at age seventy-three ...

Carnegie spent the rest of his life giving his vast fortune away. In 1889 he had written an essay entitled "Wealth," in which he argued the duties of a wealthy man were to live modestly and to use ...

The Gospel of Wealth, Andrew Carnegie's most famous essay, was written in 1889 and describes the responsibility of philanthropy by the new upper class of self-made rich. The central thesis of Carnegie's essay is that the wealthy entrepreneur must assume the responsibility of distributing his fortune in a manner that assures that it will be ...

Digital History ID 4031. Date:1889. Annotation: Andrew Carnegie's essay "Wealth." Andrew Carnegie was born to poor Scottish parents that later immigrated to the United States. A true "rags to riches" story, he became a hugely successful business man, creating an American steel conglomerate by providing iron and steel to the railways.

How to Write the Carnegie Mellon University Essays 2023-2024. Tucked away in Steelers country, otherwise known as Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, lies the 153 acre campus of Carnegie Mellon University. CMU is home to just under 7,000 undergraduate students enrolled across its seven schools and colleges. Priding itself on copious opportunities as a ...

The Gospel of Wealth. New York: Carnegie Corporation of New York, 2017 (first published in 1889). Newly edited and annotated 1889 | Essay The Scottish-born industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie (1835-1919) was one of the titans of America's Gilded Age. He was also a prolific author, writing hundreds of speeches, articles ...

In The Gospel of Wealth, Andrew Carnegie presents a visionary essay on wealth distribution and philanthropy. Carnegie challenges the prevailing notions of wealth accumulation, arguing that with great affluence comes great responsibility. He advocates for the wealthy to view their riches as a means to benefit society as a whole, promoting the ...

Andrew Carnegie was a Scottish-born industrialist who became very wealthy via the steel industry before giving away much of his fortune as a philanthropist. ... he had penned an essay, "The ...

Andrew Carnegie was a Scottish-born American industrialist who led the enormous expansion of the American steel industry in the late 19th century. He was also one of the most important philanthropists of his era. ... The Gospel of Wealth, a collection of essays (1900), The Empire of Business (1902), Problems of To-day (1908), and Autobiography ...

How to write each supplemental essay prompt for Carnegie Mellon. Prompt #1: "Why major" essay. Prompt #2: "Why us" essay. Prompt #3: "Additional information" essay. If you combined a robber baron, a classic fruit, and an extra "L," and somehow ended up with a top 25 university with an especially strong engineering program, you'd obviously ...

Wealth. North American Review, vol. 148, no. 381 (June 1889), pp. 653-664. First edition of seminal essay of gilded age intellectual history by the American industrialist Andrew Carnegie. Later reprinted as "The Gospel of Wealth," appearing as the title piece of The Gospel of Wealth and Other Timely Essays. (New York: The Century Co., 1901).

Analysis: "The Gospel of Wealth". Some scholars believe Carnegie's article, "The Gospel of Wealth," to be the original text outlining the responsibility of philanthropy, a responsibility many believe is held by the wealthy. First published in 1889 in The North American Review, "The Gospel of Wealth" insists that the rich have a ...

Thanks for exploring this SuperSummary Study Guide of "The Gospel Of Wealth" by Andrew Carnegie. A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more. For select classroom titles, we also provide Teaching Guides with discussion and quiz questions to prompt student ...

The Scottish-born industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie (1835-1919) was one of the titans of America's Gilded Age. He was also a prolific author, writing hundreds of speeches, articles, pamphlets, and letters to the editor, as well as seven books, including an Autobiography (published posthumously in 1920). Proud of his pen,

A native of Scotland, Andrew Carnegie emigrated to Allegheny, Pennsylvania, in his youth and through voracious reading and personal initiative became one of the richest men in American history. His autobiography" "recounts the real-life, rags-to-riches tale of an immigrant's rise from telegrapher's clerk to captain of industry and steel magnate.

The Gospel According to Andrew: Carnegie's Hymn to Wealth. In his essay "Wealth," published in North American Review in 1889, the industrialist Andrew Carnegie argued that individual capitalists were duty bound to play a broader cultural and social role and thus improve the world. Some labor activists sharply differed with Carnegie's point-of-view and responded with essays of their own ...

Andrew Carnegie was born on November 25, 1835, in Dunfermline, Fife, Scotland. Although he had little formal education, Carnegie grew up in a family that believed in the importance of books and ...

Andrew Carnegie Essay. Better Essays. 1721 Words. 7 Pages. Open Document. The richest man in the world, in his time, was Andrew Carnegie. His story of success was truly one of rags to riches. After coming to the U.S. from Scotland as part of a working-class family, he moved from job to job, eventually becoming more influential and gaining a ...

Guest Essay. The West Doesn't Understand How Much Russia Has Changed. May 15, 2024. ... Alexander Gabuev (@AlexGabuev) is the director of the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center in Berlin.

On this episode of Security Dilemma, we have our first return guest on the show - Dr. Stephen Wertheim. Patrick Carver Fox and John Allen Gay joined him at his offices at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace to discuss Ukraine, NATO, restraint, "retrenchment" and the foreign policy implications of the 2024 elections.