Page One Economics ®

Making sense of the national debt.

"Blessed are the young for they shall inherit the national debt."

—Herbert Hoover

We live in a world of scarcity —which means that our wants exceed the resources required to fulfill them. For many of us, a household budget constrains how many goods and services we can buy. But, what if we want to consume more goods and services than our budget allows? We can borrow against future income to fulfill our wants now. 1 This type of spending—when your spending exceeds your income—is called deficit spending. The downside of borrowing money, of course, is that you must repay it with interest, so you will have less money to buy goods and services in the future.

2018 U.S. Federal Deficit

In 2018 the federal deficit was $779 billion, which means that the U.S. federal government spent $779 billion more than it collected.

SOURCE: https://datalab.usaspending.gov/americas-finance-guide/ . Data are provided by the U.S. Department of the Treasury and refer to fiscal year 2018.

Governments face the same dilemma. They too can run a deficit, or borrow against future income, to fulfill more of their citizens' wants now (Figure 1). For a variety of reasons, governments may borrow rather than fund spending with current taxes. Deficit spending can be used to invest in infrastructure, education, research and development, and other programs intended to boost future productivity. Because this type of investment can increase productive capacity , it can also increase national income over time. And deficit spending can be used to create demand for goods and services during recessions.

For the U.S. government, deficit spending has become the norm. In the past 90 years, it has run 76 annual deficits and only 14 annual surpluses. In the past 50 years, it has run only 4 annual surpluses. 2 The accumulation of past deficits and surpluses is the current national debt : Deficits add to the debt, while surpluses subtract from the debt. At the end of the first quarter of 2019, the total national debt, also called total U.S. federal public debt, was $22 trillion and growing. This circumstance raises important questions: How much debt can an economy sustain? What are the long-term risks of high debt levels?

Who "Owns" the National Debt?

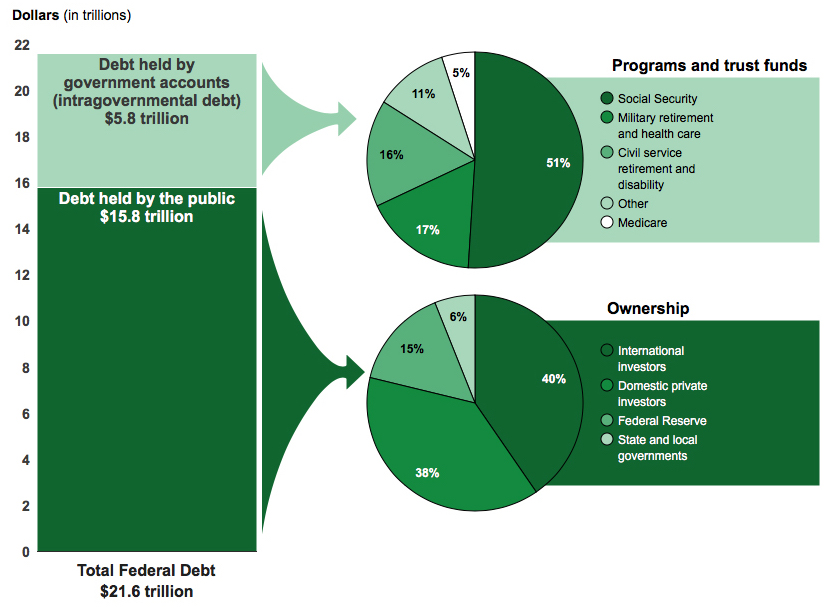

While individuals borrow money from financial institutions, the U.S. federal government borrows by selling U.S. Treasury securities (bills, notes, and bonds) to "the public." For example, when investors purchase newly issued U.S. Treasury securities, they are lending their money to the U.S. government. The purchaser may receive periodic payments and/or a final payment, known as the "face value," at the end of the term. You or someone close to you likely holds U.S. Treasury securities either directly in an investment portfolio or indirectly through a mutual fund or pension account. As such, you, or they, own U.S. government debt. But, as a taxpayer, you are also beholden to pay part of that debt. A majority of the national debt is held by "the public," which includes individuals, corporations, state or local governments, Federal Reserve Banks, and foreign governments. 3 In other words, debt held by the public includes U.S. government debt held by any entity except the U.S. federal government itself (Figure 2). The largest public holders of U.S. government debt are international investors (40 percent), domestic private investors (38 percent), Federal Reserve Banks (15 percent), and state and local governments (6 percent). 4

Fiscal Year 2018 Debt Held by the Public and Intragovernmental Debt

SOURCE: https://www.gao.gov/americas_fiscal_future?t=federal_debt , accessed September 5, 2019.

In addition to owing money to "the public," the U.S. government also owes money to departments within the U.S. government. For example, the Social Security system has run surpluses for many years (the amount collected through the Social Security tax was greater than the benefits paid out) and placed the money in a trust fund. 5 These surpluses were used to purchase U.S. Treasury securities. Forecasts suggest that as the population ages and demographics change, the amount paid in Social Security benefits will exceed the revenues collected through the Social Security tax and the money saved in the trust fund will be needed to fill the gap. In short, some of the $22 trillion in total debt is intragovernmental holdings—money the government owes itself. Of the total national debt, $5.8 trillion is intragovernmental holdings and the remaining $16.2 trillion is debt held by the public. 6 Because debt held by the public represents debt payments external to the government, many economists feel it is a better measure of the debt burden.

Household and Government Financing Over the Life Cycle

The life cycle theory of consumption and saving holds that households seek to smooth their consumption of goods and services over the life cycle by borrowing early in life (for college or to buy a home), then saving and paying down debt during their working careers, and finally living on their savings during retirement. Financial advisors often suggest that people try to be debt free before they retire. As such, people are often motivated in their prime working years to pay down their debts and then pay them off entirely before they quit working. Given this mindset, people often assume that government debt must be paid in full at some point. But there are important differences between government debt and household debt.

While people tend to prefer to pay off their debts before they retire (and stop earning income) or die, governments endure indefinitely. In general, governments expect that their economies will continue to grow and that they will continue to collect tax revenue. If governments need to refinance past debts or cover new deficits, they can simply borrow. In effect, governments never need to pay off their debts entirely because the governments will exist indefinitely.

However, this does not mean that debt is without cost. It is important to understand that debt has an opportuni ty cost . For the 2018 fiscal year, interest payments on the U.S. national debt were $523 billion. 7 This money could have financed other projects if the debt did not exist. And, of course, that $523 billion was simply the interest on the existing debt and did not pay down that debt.

How Much Debt Is Too Much Debt?

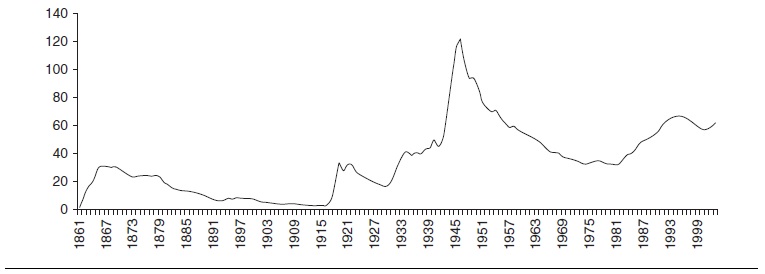

Although governments may endure indefinitely, that does not mean they can accumulate unlimited debt. Governments must have the necessary income to finance their debt. Economists use gross domestic product (GDP), the total market value, expressed in dollars, of all final goods and services produced in an economy in a given year, as a measure of national income. Because GDP indicates national income, it also indicates the potential income that can be taxed, and taxes are a primary source of government revenues. In this way, a nation's GDP determines how much debt can be supported, which is similar to how a person's income determines how much debt that person can reasonably take on. Just as individuals can sustain higher debt as their incomes increase, economies can sustain higher debt when the economy grows over time. However, if debt grows at a faster rate than income, eventually the debt might become unsustainable. Economists use the debt-to GDP ratio to measure how sustainable the debt is (Figure 3). Some economists, referred to as "owls," suggest that people's worries about U.S. government debt are overblown (see the boxed insert, "Deficit Hawks, Doves, and…Owls?").

Federal Debt Held by the Public as Percent of Gross Domestic Product

Federal debt held by the public has grown faster than GDP, lead ing to a rising debt-to-GDP ratio.

NOTE: Gray bars indicate recessions as determined by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

SOURCE: U.S. Office of Management and Budget. FRED ® , Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=lKfK, accessed September 5, 2019.

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) suggests that the U.S government debt is currently on an unsustainable path: The federal debt is projected to grow at a faster rate than GDP for the foreseeable future. A significant portion of the growth in projected debt is to fund social programs such as Medicare and Social Security. Using debt held by the public (instead of total public debt), the debt-to-GDP ratio averaged 46 percent from 1946 to 2018 but reached 77 percent by the end of 2018 (see Figure 3). It is projected to exceed 100 percent within 20 years. 8

Credit risk is the risk to the lender that the borrower will not repay the loan. It is one component of the interest rate that borrowers pay. Like for all loans, interest rates on Treasury securities reflect risk of default . The higher the risk of default, the higher the interest rate investors will expect: A country perceived as a higher credit risk must pay bond holders higher interest rates than a country perceived as a lower credit risk, all else equal. Thus, when bond yields spike, it might reflect rising risk.

Economist Herb Stein once said, "If something cannot go on forever, it will stop." In other words, trends that are unsustainable will not continue because the economy will adjust, sometimes in abrupt and jarring ways. While governments never have to entirely pay off debt, there are debt levels that investors might perceive as unsustainable. A solution some countries with high levels of unsustainable debt have tried is printing money. In this scenario, the government borrows money by issuing bonds and then orders the central bank to buy those bonds by creating (printing) money. History has taught us, however, that this type of policy leads to extremely high rates of inflation ( hyperinflation ) and often ends in economic ruin. Some of the better-known examples of such polices are Germany in 1921-23, Zimbabwe in 2007-09, and Venezuela currently. An important protection against this type of policy is to create an independent central bank that is insulated from the political process and has clear objectives (such as a specific target for the inflation rate) so that it can make policy decisions to sustain economic health over the long run rather than respond to political pressures. 9

Conclusion

The national debt is high by historical standards—and rising. People often assume that governments must pay off their debts in the same way that individuals do. However, there are important differences: Governments (and their economies) do not retire, and governments do not die (or don't intend to). As long as their debt payments remain sustainable, governments can finance their debt indefinitely. And if a government prints money to solve its debt problem, history warns that hyperinflation and financial ruin will likely result. While debt in itself is not a bad thing, it can become dangerous if it becomes unsustainable.

1 Households could alternately spend out of past savings.

2 U.S. Office of Management and Budget, "Federal Surplus or Deficit." FRED®, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=otZF , accessed September 5, 2019.

3 U.S Department of the Treasury, Bureau of the Fiscal Service. "Frequently Asked Questions about the Public Debt." https://www.treasurydirect.gov/govt/resources/faq/faq_publicdebt.htm#DebtOwner , accessed September 5, 2019.

4 U.S. Government Accountability Office. "America's Fiscal Future: Federal Debt." https://www.gao.gov/americas_fiscal_future?t=federal_debt , accessed September 5, 2019.

5 Social Security Administration. "Trust Fund Data." https://www.ssa.gov/oact/STATS/table4a3.html , accessed September 5, 2019.

6 U.S. Department of the Treasury, Bureau of the Fiscal Service. "Federal Debt Held by the Public." FRED ® , Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=mAfK , accessed September 5, 2019.

7 U.S Department of the Treasury, Bureau of the Fiscal Service. "Interest Expense on the Debt Outstanding." https://www.treasurydirect.gov/govt/reports/ir/ir_expense.htm , accessed September 5, 2019.

8 U.S. Government Accountability Office. "America's Fiscal Future." https://www.gao.gov/americas_fiscal_future?t=fiscal_forecast#projecting_the_future , accessed September 5, 2019.

9 Waller, Christopher. "Independence + Accountability: Why the Fed Is a Well-Designed Central Bank." Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review , September/October 2011, 93 (5), pp. 293-301; https://files.stlouisfed.org/files/htdocs/publications/review/11/09/293-302Waller.pdf .

© 2019, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or the Federal Reserve System.

Default: The failure to promptly pay interest or principal when due.

Fiat money: A substance or device used as money, having no intrinsic value (no value of its own), or representational value (not representing anything of value, such as gold).

Hyperinflation: A very rapid rise in the overall price level; an extremely high rate of inflation.

Inflation: A general, sustained upward movement of prices for goods and services in an economy.

National debt: The accumulation of budget deficits. Also known as government debt.

Opportunity cost: The value of the next-best alternative when a decision is made; it's what is given up.

Productive capacity: The maximum output an economy can produce with the current level of available resources.

Scarcity: The condition that exists because there are not enough resources to produce everyone's wants.

U.S. Treasury securities: Bonds, notes, bills, and other debt instruments sold by the U.S. government to finance its expenditures.

Cite this article

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Stay current with brief essays, scholarly articles, data news, and other information about the economy from the Research Division of the St. Louis Fed.

SUBSCRIBE TO THE RESEARCH DIVISION NEWSLETTER

Research division.

- Legal and Privacy

One Federal Reserve Bank Plaza St. Louis, MO 63102

Information for Visitors

Advertisement

The Political Economy of Budget Deficits

- Published: 01 March 1995

- Volume 42 , pages 1–31, ( 1995 )

Cite this article

- Alberto Alesina &

- Roberto Perotti

71 Accesses

300 Citations

27 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This paper provides a critical survey of the literature on politico-institutional determinants of the government budget. We organize our discussion around two questions: Why did certain OECD countries, but not others, accumulate large public debts? Why did these fiscal imbalances appear in the last twenty years rather than sooner? We begin by discussing the “tax smoothing” model and conclude that this approach alone cannot provide complete answers to these questions. We then proceed to a discussion of political economy models, which we organize into six groups: (1) models based upon opportunistic policy makers and naive voters with "fiscal illusion"; (2) models of intergenerational redistributions; (3) models of debt as a strategic variable, linking the current government with the next one; (4) models of coalition governments; (5) models of geographically dispersed interests; and (6) models emphasizing the effects of budgetary institutions. We conclude by briefly discussing policy implications.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Local Government Budget Stabilization: An Introduction

The determinants of fiscal deficits: a survey of literature

Budgetary Policy

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Alesina, A., Perotti, R. The Political Economy of Budget Deficits. IMF Econ Rev 42 , 1–31 (1995). https://doi.org/10.2307/3867338

Download citation

Published : 01 March 1995

Issue Date : 01 March 1995

DOI : https://doi.org/10.2307/3867338

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

JEL Classifications

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

How to Rein in the National Debt

Key findings.

- The federal government’s debt is $33 trillion and rising; budget deficits are projected to grow substantially over the next decade, reaching $2.7 trillion in 2033, or 6.4 percent of gross domestic product (GDP).

- Debt held by the public will rise steadily from 97 percent of GDP in 2022 to 115 percent in 2033—the highest level on record.

- Now is the time for lawmakers to focus on long-term fiscal sustainability, as further delay will only make an eventual fiscal reckoning that much harder and more painful. Congressional leaders should follow through on convening a fiscal commission to deal with the long-term budgetary challenges facing the country.

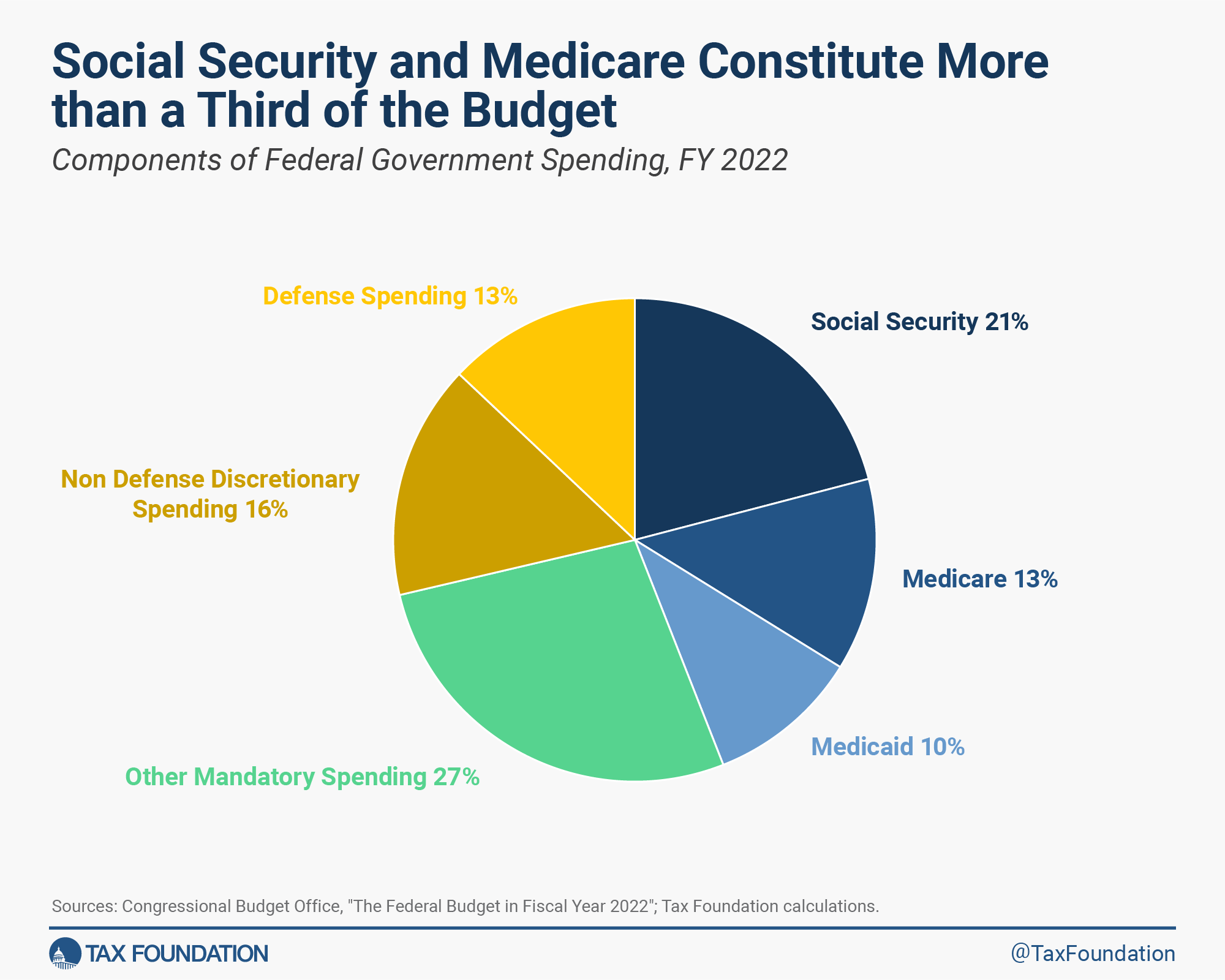

- International experiences of successful debt reductions suggest gradual, spending-focused policies. Any serious debt reduction effort must acknowledge the need to rein in the largest mandatory spending programs, Social Security and Medicare, which constitute a growing share of the budget and are the primary drivers of long-run deficits.

- If lawmakers consider tax A tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. increases in a debt reduction effort, they should focus on less distortionary taxes, such as consumption taxes, or tax reforms that rationalize tax expenditures and broaden the tax base The tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. .

Table of Contents

Introduction, u.s. federal debt in context, how other countries successfully reduced debt and deficits, how the debt ceiling deal affects the u.s. budget, options for reform.

At the time of this writing, the federal government’s debt is $33 trillion and rising. [1] Earlier this year, after a protracted negotiation and just days before the federal government was expected to become unable to pay its obligations, President Biden and House Speaker McCarthy reached a deal to suspend the debt ceiling until January 1, 2025, as part of the Fiscal Responsibility Act (FRA) of 2023. [2] The deal imposes temporary caps on certain types of government spending, reducing projected budget deficits by about $1.5 trillion over the next decade. [3]

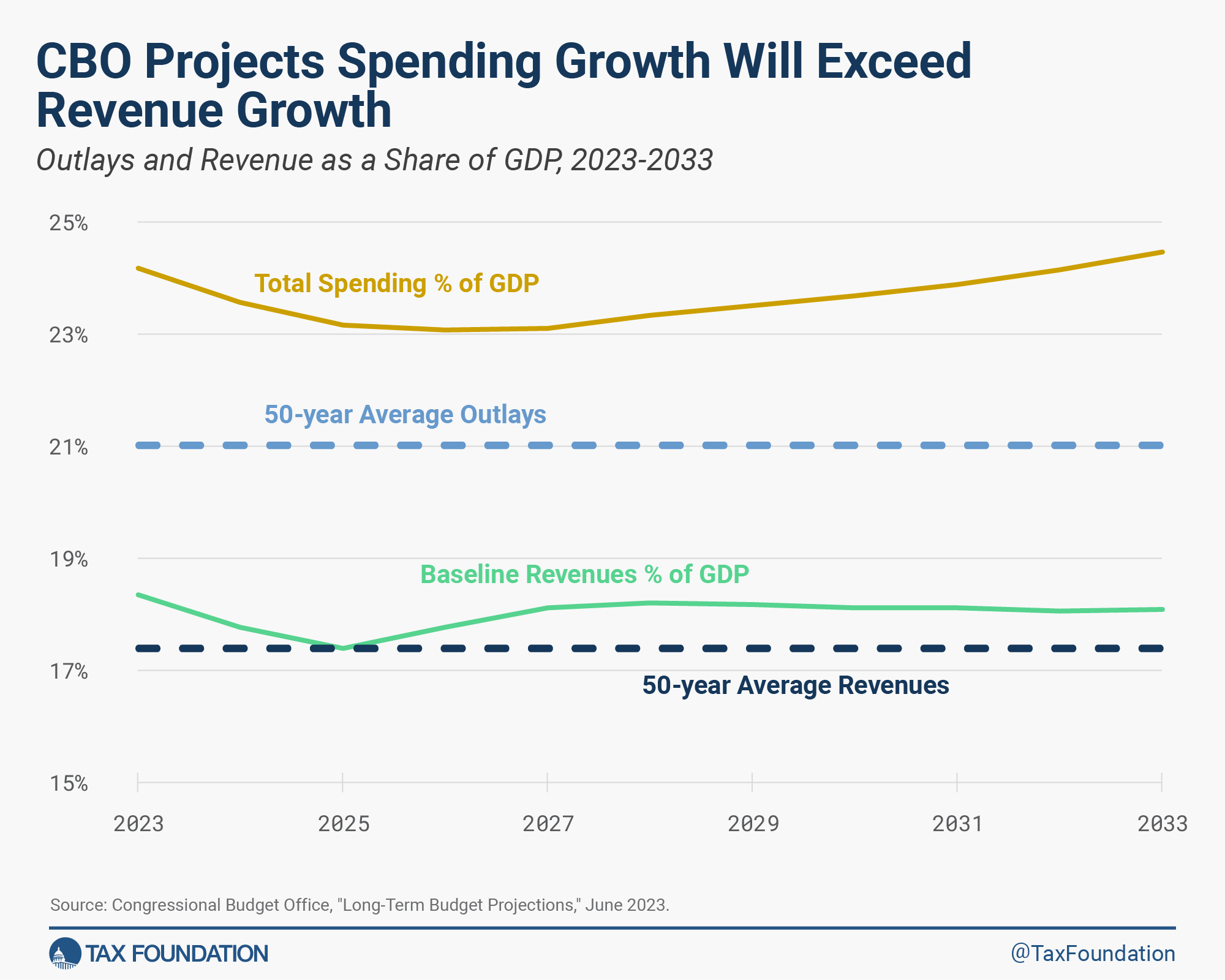

Even after the FRA, the latest forecast from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) indicates that federal budget deficits will grow substantially over the next decade and with it the national debt. Through 2033, deficits will total $18.8 trillion, reaching an annual budget deficit of $2.7 trillion in 2033, or 6.4 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), as spending growth outpaces revenue growth. [4] Debt held by the public will rise steadily from 97 percent of GDP in 2022 to 115 percent in 2033—the highest level on record.

These forecasts and other concerns about the sustainability of the federal debt led Fitch Ratings to downgrade U.S. debt from AAA to AA+ on August 1, noting “expected fiscal deterioration over the next three years, a high and growing general government debt burden, and the erosion of governance relative to ‘AA’ and ‘AAA’ rated peers over the last two decades that has manifested in repeated debt limit standoffs and last-minute resolutions.” [5] Fitch expects the deficit to reach 6.3 percent of GDP this year and rise from there due to weak economic growth and an interest burden that will grow to 10 percent of revenue by 2025.

According to the latest monthly budget review from the CBO, the deficit in the first 10 months of FY 2023 is $1.6 trillion, more than twice the deficit over the same period last year. [6] Spending is up 10 percent, driven in part by the rising costs of Social Security, Medicare, interest on the debt, and Pres. Biden’s new income-driven repayment plan for student loans. At the same time, tax collections are down 10 percent, due in part to lower capital gains tax A capital gains tax is levied on the profit made from selling an asset and is often in addition to corporate income taxes, frequently resulting in double taxation. These taxes create a bias against saving, leading to a lower level of national income by encouraging present consumption over investment. collections as the stock and housing markets have deflated.

Excluding the effects of President Biden’s student loan cancellation policy (which the Supreme Court struck down in June and is distinct from the administration’s income-driven repayment plan), budget experts are forecasting a doubling of the deficit this year, from $1 trillion (or 4 percent of GDP) last year to $2 trillion (or about 8 percent of GDP) this year. Economist Jason Furman and other experts note such a growing deficit pattern is essentially unprecedented in U.S. history outside of major crises and economic downturns. [7]

The current track of ever-increasing budget deficits, interest costs, and debt is not sustainable. In this paper, we discuss how the U.S. debt burden compares to the burdens in other countries and how other countries have successfully reduced their debt in the past. We then analyze the FRA and discuss how lawmakers could build on FRA’s reforms to stabilize the U.S. fiscal trajectory.

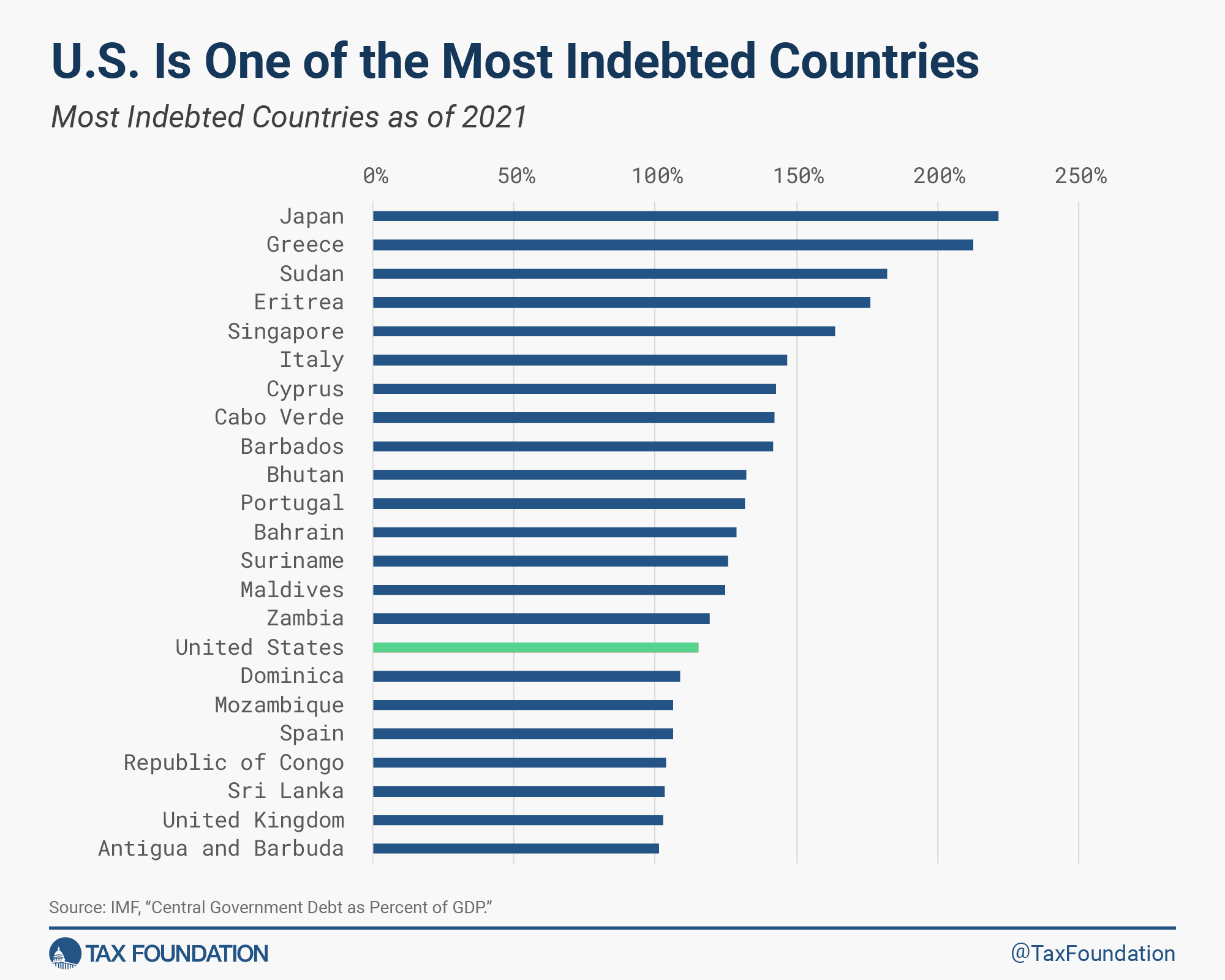

According to the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) measure of central government debt, the U.S. federal government is among the most indebted governments in the world. [8] As of 2021 (the latest available data), federal debt reached 115 percent of GDP, ranking 16 th highest out of 164 countries for which the IMF has data. Japan tops the ranking with central government debt of 221 percent of GDP, followed by Greece , Sudan, Eritrea, and Singapore. Not long ago, the U.S. was among the least indebted countries. In 2001, U.S. federal debt was 42 percent of GDP, lower than debt levels found in 100 other countries.

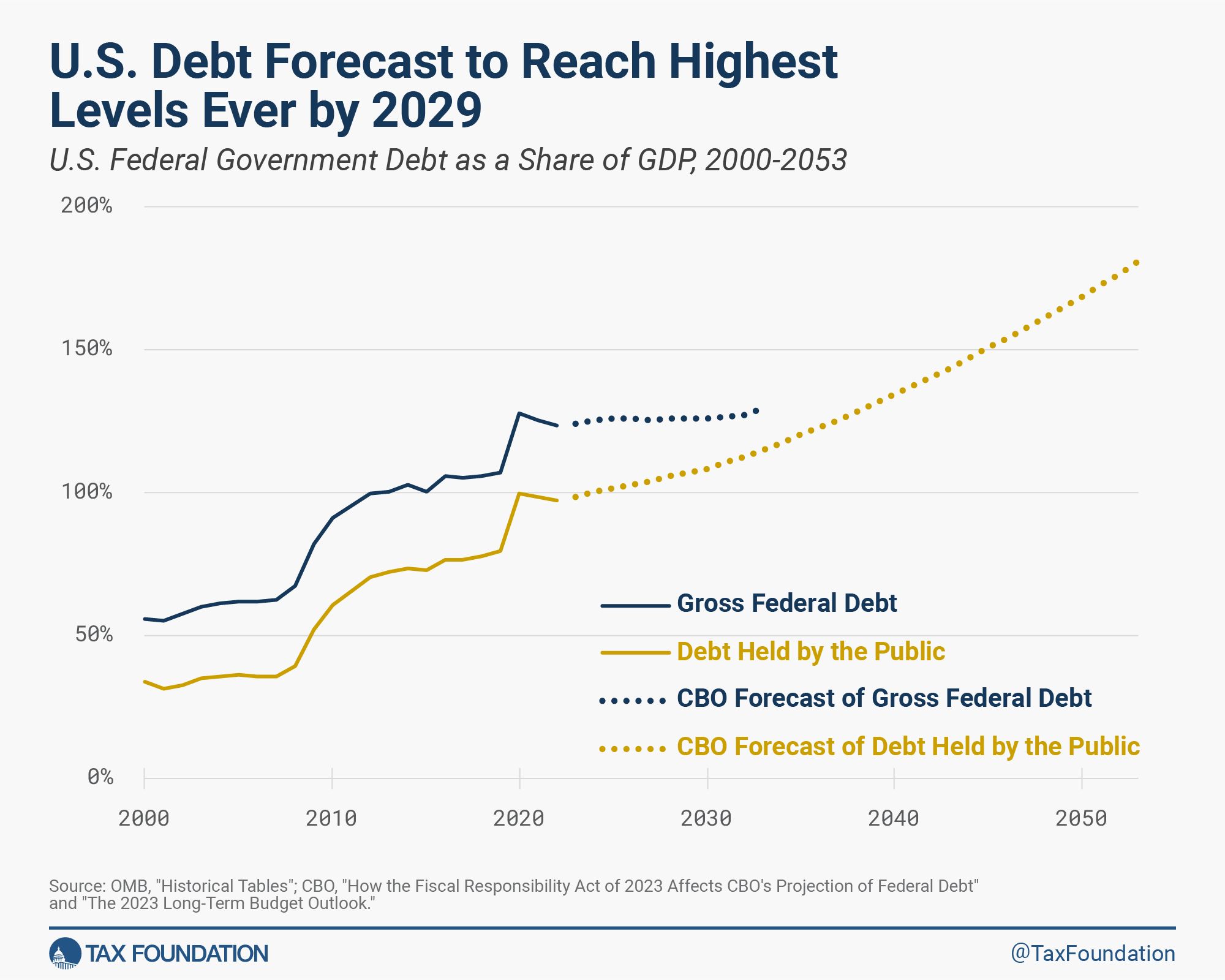

As illustrated in the nearby chart, using historical data from the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB), [9] U.S. debt surged upward in two stages over the last 20 years, first after the financial crisis in 2008 and then after the COVID-19 pandemic [10] that began in 2020. [11] Gross federal debt climbed to a record high of 128 percent of GDP in 2020 before falling to 123 percent in 2022. The recent downtick was primarily due to a surge in inflation Inflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “ hidden tax ,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. as well as real economic growth coming out of the pandemic, factors that temporarily reduced debt burdens in many countries. [12]

Debt is forecasted to reach unprecedented levels in the coming years. The CBO projects debt held by the public as a share of GDP will climb from 97 percent in 2022 to 115 percent in 2033—reaching the highest level on record by 2029—before climbing further to 180.6 percent by 2053. [13] The increase is mainly due to population aging and the rising costs of Social Security and Medicare and assumes no major economic calamities or changes in federal laws will occur. [14]

And yet, the problem may be even worse. Mark Warshawsky and other researchers at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) see rising health-care costs and interest rates contributing to even higher levels of debt. [15] They forecast debt held by the public will grow to 136 percent in 2032 and 264 percent in 2052. Like the CBO forecast, theirs assumes no banking crisis, war, pandemic, or other emergency that might cause a major economic downturn and spike in deficits. As it is, the AEI researchers forecast annual deficits to reach 7 percent of GDP by 2030 and escalate rapidly thereafter in an unprecedented and unsustainable path, around the same time that the Social Security and Medicare trust funds are expected to be depleted.

All of this may seem far off, but the costs of high debt levels are upon us now. They are most clearly visible in the form of high inflation, high interest rates, and slowing economic growth. [16] As John Cochrane, [17] Eric Leeper, [18] Tom Sargent, [19] and other economists [20] have described, the extraordinary surge of federal spending during the pandemic—exceeding $5 trillion through early 2021, or 27 percent of GDP—kicked off a 40-year high in inflation. [21]

That is because the increased spending was not financed by tax increases; it was financed by debt purchased by the Federal Reserve through money creation. [22] To combat high inflation, the Federal Reserve has raised interest rates to the highest levels in more than 20 years. That brute force method of slowing the economy through higher borrowing costs has thus far led to heavy losses for investors, a collapse in home sales, and several bank failures, among other signs of distress, with more pain to come as debt of various types is rolled over at higher interest rates. [23]

High interest rates are also putting pressure on the federal budget, causing interest payments on the debt to crowd out other federal priorities and limiting the federal government’s ability to respond to future crises. According to the CBO, the federal government’s net interest cost will exceed $1 trillion annually by 2029, eclipsing the defense budget.

The financial stress and instability of high interest rates are spreading around the globe, leading the IMF [24] to recommend fiscal restraint as a less economically damaging way to reduce inflation and debt. [25]

As U.S. lawmakers consider options to address the underlying gap between spending and revenue going forward, they should draw on international experiences of fiscal consolidation. [26] International experience cautions against tax-based fiscal consolidations, but modest tax increases may be part of a successful debt reduction package. [27] Overall, a rough guideline that emerges is that deficit reduction efforts should primarily be focused on spending reduction, with 60 percent or more of a plan’s savings coming from spending cuts and 40 percent or less from revenue increases. Further, the types of spending cuts and tax reforms that are part of a fiscal consolidation also matter.

In a recent survey of studies on the experience of countries around the world dealing with fiscal deficits and debt, the IMF outlines factors that contribute to sustained improvements in deficits and debt-to-GDP levels. [28] Reductions in social spending, as opposed to public investment, tend to produce more lasting fiscal improvements, as do less distortionary tax increases—including higher consumption, property, excise, and environmental taxes as well as reductions in tax expenditures.

Other factors important for success include the public’s perception that the government will actually fulfill its commitments and that the adjustment will be gradual, not “front-loaded” with large structural policy changes.

Additional research further supports the idea that fiscal consolidations based on spending cuts have had fewer negative effects on GDP than tax increases. Looking at 16 OECD countries over a 30-year period, Alberto Alesina and his coauthors found that, on average, spending cuts were associated with mild recessions and in some cases no downturns at all, while almost all fiscal reforms based on tax increases were followed by “prolonged and deep recessions.” [29] Fiscal adjustments based on tax increases reduced investment and business confidence. By contrast, business confidence rebounded almost immediately after a fiscal adjustment based on spending reforms.

In a follow-up paper, Alesina and his coauthors showed that cuts in transfer spending had milder negative effects on economic growth, nearing zero, compared to cuts in government consumption and investment, though both have relatively little impact on growth compared to tax increases. [30]

Examining fiscal adjustments from a sample of 26 countries from 1995 to 2018, a Mercatus Center analysis found that successful consolidations, defined as one where the debt-to-GDP ratio declines by at least 5 percentage points in the three years after the plan is implemented, were more spending-focused than tax-focused. [31] More than half (53 percent) of expenditure-based fiscal consolidations, defined as those in which spending cuts represent 60 percent or more of deficit reduction, were successful. In contrast, only 38 percent of tax-based fiscal consolidations (defined as those in which tax increases represent 60 percent or more of deficit reduction) were successful. Balanced fiscal consolidations, however, had the highest success rate at 55 percent. Among the successful fiscal consolidations, on average, 60 percent of the deficit reduction came from spending cuts, whereas among the unsuccessful fiscal consolidations, 74 percent of the deficit reduction came from tax increases.

A European Central Bank analysis arrived at a similar conclusion: EU countries that pursued spending-based consolidations had higher growth rates five years following a fiscal consolidation announcement than those that pursued tax-based ones. [32] While part of the difference in economic performance can be explained by better follow-through for revenue-based plans, the bulk of the difference was due to the composition of consolidations, with revenue having large, negative effects compared to nearly zero for spending.

When it comes to designing tax changes, raising a dollar of revenue through different taxes has different effects on the economy. A more harmful tax increase can shrink the economy, yielding less revenue from other taxes. Harm the economy too much and the solution may prove counterproductive, reducing the likelihood of successful debt stabilization.

In a study of 17 OECD countries over a 30-year period, Norman Gemmell and other academics showed that reducing deficits by raising distortionary taxes, such as income taxes, consistently reduced economic growth, while raising less distortionary taxes, such as consumption taxes, was more growth-enhancing. [33] They found small positive growth effects from deficit-financed “productive” spending, such as infrastructure, implying that cutting such spending could hurt growth. Negative growth effects from cutting productive spending would take longer to materialize, while negative effects of tax increases would be more immediate. Deficit-financed “nonproductive” spending, such as transfers, was shown to have a negative effect on long-run economic growth, suggesting that cutting them would boost growth.

In all, the experience with successful fiscal consolidations suggests adjustments should be gradual and focused on spending, with careful consideration of the growth effects of selected policies. If tax increases are included in a package, [34] it is most effective to focus on less distortionary taxes, such as consumption taxes, or tax reforms that rationalize tax expenditures [35] and broaden the tax base. [36]

Among other changes, the debt ceiling deal enacted in June (FRA) limits discretionary spending over the next two years, expedites permitting for pipelines and other energy infrastructure, and expands work requirements for food and income assistance programs. [37]

Specifically, the deal caps discretionary spending (except for certain funding including emergencies and overseas contingencies) at $1.59 trillion in FY 2024 and $1.61 trillion in FY 2025, roughly flat relative to this year’s $1.63 trillion. It caps defense spending at $886 billion in FY 2024 and $895 billion in FY 2025 and non-defense discretionary spending at $704 billion in FY 2024 and $711 billion in FY 2025.

The deal also contains a mechanism to enforce a better budget process by further reducing the budget caps by 1 percent if Congress fails to enact all 12 appropriations bills by January 2024. Additionally, the deal specifies certain unenforceable spending limits beyond FY 2025.

Outside of the spending caps, the deal makes several other changes with relatively small effects on the budget. The deal rescinds about $11 billion in unspent pandemic relief funds, codifies the already-expected end of the pause in student loan payments, and claws back about a quarter of the $80 billion in additional IRS funding authorized by last year’s Inflation Reduction Act. The deal also tightens work requirements and eligibility rules for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF), speeds the permitting process for energy and infrastructure projects by limiting environmental reviews, and requires cost estimates for administrative actions through 2024.

In total, the CBO estimates the FRA will reduce deficits by $1.5 trillion from 2023 to 2033, including a substantial reduction in interest payments on the debt of $188 billion. [38]

The FRA rightly focuses on reducing spending, which is what most successful fiscal consolidations have done. But while the spending reductions are substantial, they pale in comparison to total federal spending of about $6.4 trillion this year and $79 trillion projected over the next decade, or projected deficits of about $19 trillion over the next decade. [39]

The current CBO forecast indicates spending this year will be about 24.2 percent of GDP and average 23.6 percent of GDP over the next decade, compared to an average of 21 percent over the last 50 years. To bring spending closer into alignment with historic norms would require cuts several times larger than what the FRA enacted. Just to stabilize the debt at its current share of the economy would require about $7.5 trillion in deficit reduction over the next 10 years, inclusive of reduced interest costs.

The problem is that the FRA does not address the largest part of the budget and the source of growing fiscal imbalances, which is mandatory spending, including major entitlement programs such as Social Security and Medicare. [40] Under current law, mandatory spending is set to grow from 14.3 percent of GDP next year to 15.3 percent in 2033, while discretionary spending (the part of the budget addressed by the FRA) will shrink from 6.6 percent to 5.6 percent over the same period. [41] Discretionary spending was already on a downward trajectory before the FRA; in May, the CBO forecasted it would fall from 6.5 percent of GDP in 2024 to 6.0 percent in 2033. [42]

By leaving mandatory spending on autopilot, the FRA fails to address the core driver of long-term deficits and fails to grapple with the weakening finances of the Social Security and Medicare trust funds, which are projected to be insolvent within a decade. [43]

To address the more challenging parts of the budget, especially the unsustainable growth in mandatory spending, lawmakers should follow up on the debt ceiling agreement with a focus on long-term fiscal sustainability.

A Fiscal Commission and Other Reforms to the Budget Process

In the aftermath of the FRA, Speaker McCarthy indicated he would seek to convene a fiscal commission to grapple with long-term budgetary challenges, a meaningful next step to improve the process of budget reform. [44] The 2010 Simpson-Bowles Commission was the last time a fiscal commission was assembled, and it can offer some lessons going forward. [45]

First, perhaps now more than ever, convening a fiscal commission makes eminent sense. A commission comprised of budgetary experts selected on a bipartisan basis would provide a space for tough budget decisions outside of the political pressures that make real discussion of budgetary alternatives and trade-offs impossible. The commission should aim for specific targets, such as stabilizing debt as a share of GDP at or below current levels, and engage and solicit input from citizens and outside experts to form a set of recommendations.

Second, as noted by Dave Walker and others, for a fiscal commission to be successful, it needs to be statutory, so the administration and members of Congress have buy-in to the process. [46] The recommendations of the commission should be put to an up or down vote in Congress. All of this, of course, assumes elected officials first acknowledge the scale of the problem, are willing to engage with solutions, and then follow through with action.

As a longer-term process reform, Dave Walker and others, including the late Nobel laureate economist James Buchanan, have also recommended a constitutional amendment to enforce fiscal sustainability. [47] The amendment could take many forms. Buchanan recommended an amendment that limits estimated spending to estimated tax revenues, with the ability to waive this requirement in extraordinary situations via separate approval by three-fourths of the House of Representatives and the Senate. [48]

Several countries have had success controlling debt through a similar constitutional rule. For instance, since 2003, Switzerland ’s “debt brake,” which limits spending to revenues over the business cycle, has led to the stabilization of gross government debt at just over 40 percent of GDP. [49] As with a fiscal commission, the effectiveness of such an amendment depends on a wide consensus among the public and policymakers. [50] The Swiss debt brake, for example, was approved by 85 percent of its public. While this seems a remote possibility currently in the U.S., an amendment process could gain traction as the growing U.S. debt becomes more problematic.

Spending Reforms

Turning to reforms of particular spending programs, lawmakers should focus on controlling the growth of the largest mandatory spending programs: Social Security and Medicare. Together, the two programs will grow from 8.2 percent of GDP this year to 10.1 percent of GDP in 2033, while the rest of the budget shrinks from 15.9 percent to 14.4 percent, according to the CBO’s latest forecast. [51] Over the long run, essentially all of the deficit is due to Social Security, Medicare, and associated interest costs. [52]

The demographic factors contributing to the growth of these old-age programs are not uniquely American, as populations are aging rapidly in several countries, [53] especially in Japan and across Europe . There too, pressure is rising on programs that promise benefits for an expanding pool of retirees financed by taxes on a shrinking pool of workers. [54] Economist Eric Leeper describes this dynamic as creating a kind of “insidious” inflationary pressure, as the budgetary imbalance and associated risks grow somewhat imperceptibly over time and the looming policy uncertainty creates costly maneuvering. [55]

Social Security and traditional Medicare (Part A) are both funded by payroll taxes on a “pay-as-you-go basis.” That is, current payroll taxes paid by today’s workers fund payments to today’s retirees. Unlike discretionary spending, which must be voted on by Congress every year during the appropriations process, current law mandates Social Security and Medicare spending. Mandatory spending in its entirety represents more than two-thirds of the current U.S. budget. [56]

An aging U.S. population and a declining worker-per-retiree ratio (now only 3 to 1) have contributed to the cost of financing Social Security and Medicare. Under current law, Medicare’s Hospital Insurance Trust Fund will be insolvent by 2031, and Social Security’s

Old Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI) Trust Fund by 2033. [57] Without reforms, Social Security benefits would be automatically reduced across the board by 20 percent, and Medicare hospital insurance payments would be cut by 11 percent. Absent any reforms, the 2023 Trustees Report shows that a significant payroll tax hike of 4.2 percent would be required to close the current funding gap for OASDI and Medicare. [58]

Given the dire outlook, policymakers must reform the programs to ensure their long-run stability. A brief, non-exhaustive review of various proposals over the past decade to reform Social Security and Medicare illustrates the possibility of tackling the issue with a measured and bipartisan approach.

Social Security Reforms

In 2010, President Obama established the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform to develop a plan to reduce the deficit. The bipartisan commission produced what became known as the Simpson-Bowles plan—named after then-Senators Alan Simpson (R-WY) and Erskine Bowles (D-NC)—which proposed significant changes to Social Security to ensure its fiscal sustainability. [59] Although the plan was never enacted, many of its recommendations can be found in other proposals , and for this reason, it is worth reviewing in full.

Simpson-Bowles would have slowed benefit growth for high-income earners, making Social Security more progressive. Currently, benefits are calculated using a three-bracket system, where higher earners receive a lower share of their lifetime earnings than lower earners. The plan would have gradually phased in a four-bracket structure of replacement rates starting in 2017, reducing the share of lifetime benefits for higher earners even further.

Additionally, the plan would have gradually raised the retirement age. Under current law, the normal retirement age is 67, but retirees can begin collecting benefits as early as 62. Simpson-Bowles would have indexed both the normal and early retirement ages to life expectancy, making the normal retirement age 68 by 2050.

Currently, all Social Security benefits are adjusted for inflation using the Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W). The plan would have switched to chained CPI for cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs) instead. The standard CPI typically overstates inflation as it doesn’t account for consumers’ ability to switch to cheaper substitutes for goods, whereas the chained CPI better captures these consumption dynamics. [60] Switching to the chained CPI would slow benefit growth and therefore reduce the overall cost of the program.

On the revenue side, the plan would have gradually raised the payroll tax A payroll tax is a tax paid on the wages and salaries of employees to finance social insurance programs like Social Security, Medicare, and unemployment insurance. Payroll taxes are social insurance taxes that comprise 24.8 percent of combined federal, state, and local government revenue, the second largest source of that combined tax revenue. cap. Currently, wages and salaries above $160,200 do not face the payroll tax for Social Security. [61] As a result, the tax applies to about 83 percent of all wages earned. Simpson-Bowles would have raised the cap to ensure that 90 percent of all wages were covered by 2050.

Another more recent proposal by Senator Bill Cassidy (R-LA) would attempt to shore up Social Security by borrowing $1.5 trillion and placing it in a diversified investment fund that would be used to replenish the Social Security trust fund. [62] Cassidy characterizes the proposal as a bridge between President Bill Clinton’s proposal to invest part of the trust fund in stocks, and President George W. Bush’s proposal to partially privatize Social Security. However, the plan does not include private accounts, a key feature in successful pension reforms implemented in several countries, [63] including Sweden [64] and Australia . [65] Lawmakers should look to their experiences [66] for guidance on this promising direction for reform. [67]

Medicare Reforms

Currently, physicians who serve patients under traditional Medicare are reimbursed under a fee-for-service system, where they are compensated for the quantity of services they provide rather than the quality. This leads to physicians often providing unnecessary treatments or tests that do little to improve health outcomes for their patients, driving up the costs of Medicare. Proposals to reform fee-for-service have included switching to a system of bundled payments, where physicians are reimbursed based on a fixed price for specific medical episodes. [68] The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services began experimenting with such a system [69] for hip and knee replacements in 2016, and announced further expansions for other types of care, but expanding it even more broadly could help keep costs down. [70]

Alternatively, reforms could go even further by switching to a system of capitation, where physicians are paid a set amount per patient, regardless of how much care is provided. Currently, Medicare Advantage (Medicare Part C) functions this way. [71] Under Medicare Advantage, recipients select among a variety of mostly managed care plans and private insurers receive a fixed payment through Medicare to cover the medical expenses. This incentivizes doctors to serve their patients in the most efficient way possible.

Other proposals call for simply increasing premiums. Premiums for Medicare Part B (which covers outpatient care) currently only cover about 25 percent of the program’s outlays. [72] The CBO estimated that increasing the basic premium to cover 35 percent of the outlays would reduce the deficit by $406 billion from 2023 to 2032.

Similarly, reforming cost sharing would reduce health-care overutilization and lower expenditures. Under the current system, Medicare patients face a high deductible when admitted to a hospital, but no cap on out-of-pocket expenses. As a result, 90 percent of patients acquire additional private coverage known as Medigap. [73] These plans are often expensive because the government is picking up the tab, and only a few plans are available, leading patients to consume more health care than necessary. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CFRB) offered a proposal that would implement an out-of-pocket cap and a higher deductible for non-hospital services, reducing the need to purchase additional coverage. [74]

One of the more ambitious plans to reform Medicare is to transition to a “premium support” model. Such a system was proposed by Senators Ron Wyden (D-OR) and Paul Ryan (R-WI) and the Bipartisan Policy Center (BPC) in 2011. [75] The Ryan-Wyden plan would have allowed traditional Medicare plans to compete with private insurance plans in a competitive bidding process, and then the government would have provided vouchers to seniors to purchase coverage. [76] The value of the vouchers would have grown at a rate of GDP plus one percent, and the expectation was that allowing private insurers to compete would help lower costs. To keep costs down even further, the BPC plan would have required Medicare beneficiaries earning above 150 percent of the poverty level to pay higher premiums if spending exceeded the growth limit.

Finally, numerous proposals have been offered to reduce the price of drugs purchased through Medicare. While some of these policies can actually harm innovation in the pharmaceutical sector (e.g., the Inflation Reduction Act’s price controls on specific drugs), [77] more modest reforms could encourage physicians to prescribe cheaper generics. [78] Under Medicare B, doctors purchase drugs for their patients and then get reimbursed based on the average sales price of the drug (net of all rebates and discounts), plus 6 percent of the drug cost. This incentivizes physicians to recommend more expensive, branded drugs since they will receive a larger reimbursement.

One proposed reform from the CFRB would implement “clinically comparable drug pricing,” where physicians would be reimbursed based on a weighted average sales price for clinically similar classes of drugs. [79] This would remove the incentive for physicians to recommend more expensive drugs, as they would incur all the additional costs of purchasing a drug above that weighted average sales price.

Tax Reforms

As discussed above, the experiences of countries around the world caution against raising particularly distortive taxes to reduce debt. However, modest tax increases with minimal harm to the economy can contribute to debt stabilization.

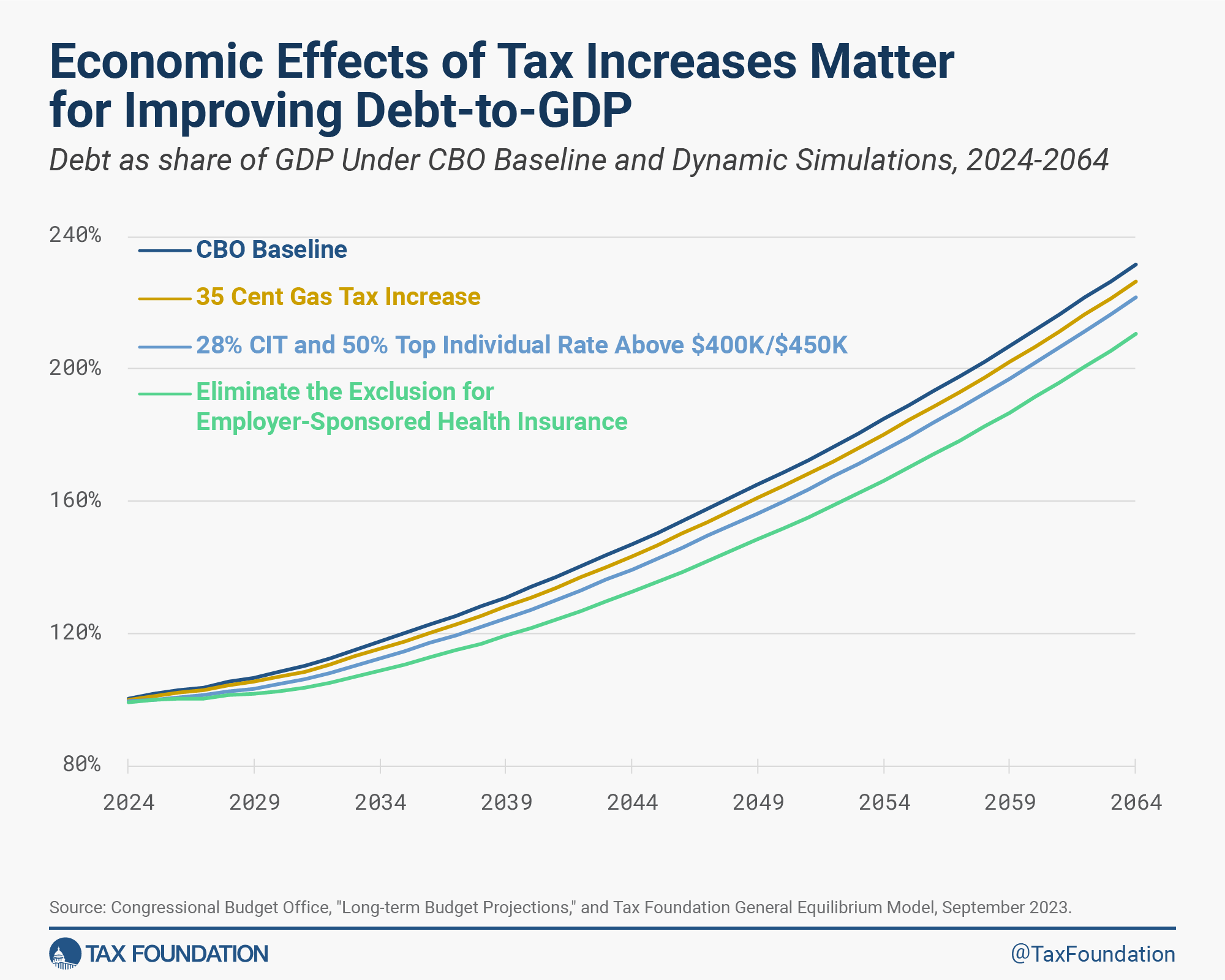

To illustrate, we have simulated the following three potential tax increases that differ considerably in their effects on the U.S. economy and the federal debt burden:

- Increasing the federal gas tax A gas tax is commonly used to describe the variety of taxes levied on gasoline at both the federal and state levels, to provide funds for highway repair and maintenance, as well as for other government infrastructure projects. These taxes are levied in a few ways, including per-gallon excise taxes , excise taxes imposed on wholesalers, and general sales taxes that apply to the purchase of gasoline. by $0.35 and indexing it for inflation

- Broadening the individual income tax base by eliminating the exclusion for employer-sponsored health insurance (ESI)

- Raising the top individual income tax An individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment . Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. rate to 50 percent above $400,000 for single filers and $450,000 for joint filers, and raising the corporate tax rate to 28 percent

As shown in the table and chart below, all three options would raise substantial revenue, in excess of $3 trillion over 10 years in the case of eliminating the ESI exclusion. Both the higher gas tax and the elimination of the ESI exclusion result in relatively minor economic trade-offs for the revenue raised. In contrast, higher marginal income tax rates come at a steep cost: GDP would be reduced by about 1.3 percent over the long run due to decreased incentives to work, save and invest.

As a result, a less economically harmful option like eliminating the ESI exclusion results in a much more powerful reduction in long-run debt as a share of GDP—double the impact on the debt ratio over the long run and less than half the impact on GDP, as compared to raising income tax rates.

However, all three of these revenue options demonstrate that even with substantially higher tax revenues, debt-to-GDP would still continue to grow unsustainably—exceeding 200 percent of GDP by 2064—demonstrating that spending needs to be the primary focus to successfully reduce debt.

That brings us to the options currently on the table. Unfortunately, President Biden’s plan to reduce the deficit, as described in his most recent budget, depends entirely on net revenue increases from raising economically damaging taxes—an approach inconsistent with successful efforts to reduce debt. [80]

The Biden administration’s estimates of nearly $3 trillion in deficit reduction under the budget are highly uncertain, particularly as they depend on a novel set of tax increases. On a conventional basis, Tax Foundation estimates the President’s budget plan would reduce the 10-year deficit by $2.5 trillion. Because the plan would reduce GDP by 1.3 percent, the deficit reduction drops to $1.9 trillion over 10 years on a dynamic basis.

By 2033, publicly held debt as a share of GDP will reach 115 percent under the baseline. [81] Pres. Biden’s budget would reduce it to 108.4 percent conventionally or 110.6 percent dynamically. In the long run (by 2064), the plan would reduce debt-to-GDP from 231.8 percent under the baseline to 207.0 percent conventionally or 214.6 percent dynamically.

The smaller improvement on a dynamic basis highlights the importance of minimizing the economic costs of tax hikes and instead seeking efficient sources of revenue.

For example, in contrast to Biden’s proposals, Tax Foundation’s Tax Reform Plan for Growth and Opportunity proposes replacing the current corporate income tax A corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses , with income reportable under the individual income tax . with a distributed profits tax A distributed profits tax is a business-level tax levied on companies when they distribute profits to shareholders, including through dividends and net share repurchases (stock buybacks). and the current individual income tax with a much broader based flat tax An income tax is referred to as a “flat tax” when all taxable income is subject to the same tax rate, regardless of income level or assets. , and reforming estate and capital gains taxes at death. [82] Base broadeners in the plan help offset the costs of the reforms, including eliminating most tax expenditures: the exclusion for employer-sponsored health insurance, all itemized deductions, and many tax credits.

The plan is approximately revenue neutral in the long run, and it raises about $522 billion over the 10-year budget window. Because it raises revenue more efficiently, it increases long-run GDP by 2.5 percent and reduces long-run debt-to-GDP by 9.2 percentage points on a dynamic basis to 222.6 percent.

In lieu of a fundamental overhaul of the tax system, lawmakers may consider permanence for all or part of the expiring Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) provisions. An across-the-board extension of the individual income tax expirations would be pro-growth but would significantly reduce revenue. Alternatively, lawmakers could build on the TCJA’s reforms to further broaden the base by, for example, using the options outlined in Tax Foundation’s Plan for Growth and Opportunity [83] and curtailing new green energy tax credits. [84]

Other reforms, such as permanent expensing for capital investments and R&D, would also enhance the efficiency of the tax system. [85] On a conventional and dynamic basis, such changes would reduce revenue in the short term, but, over the long run, the fading revenue cost and permanent economic benefit would be enough to slightly reduce deficits and the debt-to-GDP ratio.

Lifting the debt ceiling probably relieved some pressure on U.S. lawmakers to reduce the nation’s growing debt, at least until the debt ceiling returns in early 2025. Until then, other events are likely to remind lawmakers of the seriousness of the problem, including the recent downgrade of U.S. debt and the apparent doubling of the deficit over the last year. Now is the time for lawmakers to focus on long-term fiscal sustainability, as further delay will only make an eventual fiscal reckoning that much harder and more painful.

House Speaker McCarthy should follow through on his idea to convene a fiscal commission to deal with the long-term budgetary challenges facing the country. Any fiscal commission or other serious debt reduction effort must acknowledge the need to rein in the largest mandatory spending programs, Social Security and Medicare, which constitute a growing share of the budget and are the primary drivers of long-run deficits. The programs are unsustainable and are statutorily scheduled for a major reduction in benefits within the decade absent reforms.

Tax increases and tax reform should also be on the table. Lawmakers must not lose sight of the incentive effects of various possible reforms, both because of the demonstrable effects on the larger economy and standards of living, and because the effects in turn affect the sustainability of the debt reduction. Though it may not be politically popular to raise the gas tax or broaden the tax base, to the extent that a comprehensive deficit reduction package includes modest tax increases, such options are the most advisable on economic grounds. Ultimately, a better-designed tax system should be a goal of any fiscal consolidation package, noting that the majority of deficit savings should come from spending reforms.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

[1] Treasury Department, “Fiscal Data: Debt,” https://fiscaldata.treasury.gov/americas-finance-guide/national-debt/ .

[2] The debt limit, the nation’s debt, and the annual federal budget deficits are distinct but related issues. Annual budget deficits are the difference between how much revenue the nation brings in, primarily through taxes, and how much it spends. The nation’s debt reflects the accumulation of past budget deficits—spending promises that have already been made but not yet paid for. Congress limits the amount of debt that the Treasury can issue to pay obligations, and if it hits that limit, it must rely on cash balances and extraordinary measures to manage the debt in the interim until Congress suspends or raises the limit.

[3] Congressional Budget Office, “How the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 Affects CBO’s Projections of Federal Debt,” Jun. 9, 2023, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/59235#:~:text=Summary,affect%20federal%20spending%20and%20revenues .

[5] Fitch Ratings, “Fitch Downgrades the United States ’ Long-Term Ratings to ‘AA+’ from ‘AAA’; Outlook Stable,” Aug. 1, 2023, https://www.fitchratings.com/research/sovereigns/fitch-downgrades-united-states-long-term-ratings-to-aa-from-aaa-outlook-stable-01-08-2023 .

[6] Congressional Budget Office, “Monthly Budget Review: July 2023,” Aug. 8, 2023, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/59377.

[7] Jeff Stein, “U.S. deficit explodes even as economy grows,” The Washington Post , Sep. 3, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2023/09/03/us-debt-deficit-rises-interest-rate/.

[8] International Monetary Fund, “Central Government Debt,” 2021, https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/CG_DEBT_GDP@GDD/USA .

[9] The White House, “Historical Tables,” https://taxfoundation.org/growth-opportunity-us-tax-reform-plan/ .

[10] Alex Muresianu and William McBride, “Taxes, Fiscal Policy, and Inflation,” Tax Foundation, Jan. 24, 2022, https://taxfoundation.org/fiscal-policy-inflation-tax/ .

[11] Alex Durante, “U.S. Fiscal Response to COVID-19 Among Largest of Industrialized Countries,” Tax Foundation, Jan. 4, 2022, https://taxfoundation.org/us-covid19-fiscal-response/ .

[12] M. Ayhan Kose, Franziska Ohnsorge, Kersten Stamm, and Naotaka Sugawara, “Government debt has declined but don’t celebrate yet,” Brookings, Feb. 21, 2023, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2023/02/21/government-debt-has-declined-but-dont-celebrate-yet/ .

[13] Congressional Budget Office, “Budget and Economic Data,” https://www.cbo.gov/data/budget-economic-data#3 .

[14] Alex Durante, “Tackling America’s Debt and Deficit Crisis Requires Social Security and Medicare Reform,” Tax Foundation, May 23, 2023, https://taxfoundation.org/medicare-social-security-reform-us-debt-deficits/ .

[15] Mark J. Warshawsky, John Mantus, and Gaobo Pang, “A Unified Long-Run Macroeconomic Projection of Health Care Spending, the Federal Budget, and Benefit Programs in the US,” American Enterprise Institute, Sep. 1, 2023, https://www.aei.org/research-products/working-paper/a-unified-long-run-macroeconomic-projection-of-health-care-spending-the-federal-budget-and-benefit-programs-in-the-us/ .

[16] Francesco Grigoli and Damiano Sandri, “Public Debt and Household Inflation Expectations,” IMF Working Paper No. 2023/066, Mar. 17, 2023, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2023/03/20/Public-Debt-and-Household-Inflation-Expectations-530644 .

[17] John Cochrane, The Fiscal Theory of the Price Level , (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2023), https://www.johnhcochrane.com/research-all/the-fiscal-theory-of-the-price-level-1 .

[18] Eric Leeper, “Fiscal Dominance: How Worried Should We Be?,” Mercatus Center George Mason University, Apr. 3, 2023, https://www.mercatus.org/research/policy-briefs/fiscal-dominance-how-worried-should-we-be .

[19] George J. Hall and Thomas J. Sargent , “Three world wars: Fiscal–monetary consequences,” PNAS 119:18 (April 2022), https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2200349119 .

[20] Michael R. Strain, “How Do Government Deficits and Debt Drive Inflation?” American Enterprise Institute, Feb. 28, 2023, https://www.aei.org/events/how-do-government-deficits-and-debt-drive-inflation/ .

[21] Alex Durante, “U.S. Fiscal Response to COVID-19 Among Largest of Industrialized Countries,” Tax Foundation, Jan. 4, 2022, https://taxfoundation.org/us-covid19-fiscal-response/ .

[22] William McBride and Alex Durante, “The “Inflation Tax” Is Regressive,” Tax Foundation, Sep. 29, 2022, https://taxfoundation.org/inflation-regressive-effects/ .

[23] Greg Ip, Joe Pinsker, Will Parker, Walden Siew, Jennifer Williams-Alvarez, Veronica Dagher, and Telis Demos, “Rates are Up. We’re Just Starting to Feel the Heat,” The Wall Street Journal , Sep. 1, 2023, https://www.wsj.com/personal-finance/interest-rates-investing-mortgage-banks-real-estate-debt-ca87c251 .

[24] Tobias Adrian and Vitor Gaspar, “How Fiscal Restraint Can Help Fight Inflation,” IMF, Nov. 21, 2022, https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2022/11/21/how-fiscal-restraint-can-help-fight-inflation .

[25] International Monetary Fund (IMF), Fiscal Monitor: On the Path to Policy Normalization , IMF, April 2023, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/FM/Issues/2023/04/03/fiscal-monitor-april-2023 .

[26] Alex Durante and Erica York, “Fast Approaching Debt Limit Deadline and Growing Debt Demand Action,” Tax Foundation, May 4, 2023, https://taxfoundation.org/debt-limit-deadline-federal-budget-deficits/ ; William McBride, “How America’s Debt Problem Compares to Other Countries—and Why It Matters,” Tax Foundation, May 9, 2023, https://taxfoundation.org/us-debt-compares-to-other-countries/ .

[27] Veronique de Rugy and Jack Salmon, “Flattening the Debt Curve: Empirical Lessons for Fiscal Consolidation,” Mercatus Center George Mason University, Jul. 22, 2020, https://www.mercatus.org/research/research-papers/flattening-debt-curve-empirical-lessons-fiscal-consolidation ; Alex Durante, “Tackling America’s Debt and Deficit Crisis Requires Social Security and Medicare Reform,” Tax Foundation, May 23, 2023, https://taxfoundation.org/medicare-social-security-reform-us-debt-deficits/ .

[28] Vybhavi Balasundharam, Olivier Basdevant, Dalmacio Benicio, Andrew Ceber, Yujin Kim, Luca Mazzone, Hoda Selim, and Yongzheng Yang, “Fiscal Consideration: Taking Stock of Success Factors, Impact, and Design,” IMF, Mar. 17, 2023, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2023/03/17/Fiscal-Consolidation-Taking-Stock-of-Success-Factors-Impact-and-Design-530647 .

[29] Alberto Alesina, Carlo Favero, and Francesco Giavazzi, “The Output Effect of Fiscal Consolidations,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 18336, August 2012, https://www.nber.org/papers/w18336 .

[30] Alberto Alesina, Omar Barbiero, Carlo Favero, Francesco Giavazzi, and Matteo Paradisi, “The Effects Of Fiscal Consolidations: Theory And Evidence,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 23385, May 2017, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w23385/w23385.pdf .

[31] Veronique de Rugy and Jack Salmon, “Flattening the Debt Curve: Empirical Lessons for Fiscal Consolidation,” Mercatus Center George Mason University, Jul. 22, 2020, https://www.mercatus.org/research/research-papers/flattening-debt-curve-empirical-lessons-fiscal-consolidation .

[32] Roel M. W. J. Beetsma, Oana Furtuna, and Massimo Giuliodori, “Revenue versus Spending-Based Consolidation Plans: The Role of Follow-Up,” SSRN ECB Working Paper No. 2178, Oct. 10, 2018, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3262446

[33] Norman Gemmell, Richard Kneller, and Ismael Sanz, “The Timing and Persistence of Fiscal Policy Impacts on Growth: Evidence from OECD Countries,” The Economic Journal 121:550 (February 2011): F33–F58, https://academic.oup.com/ej/article-abstract/121/550/F33/5079706 .

[34] Erica York, “Design Matters When Raising Taxes to Reduce the Deficit and Stabilize the Debt,” Tax Foundation, May 16, 2023, https://taxfoundation.org/us-debt-taxes-deficit/ .

[35] Erica York and William McBride, “Lawmakers Could Pay for Reconciliation While Improving the Tax Code,” Tax Foundation, Oct. 25, 2021, https://taxfoundation.org/pay-for-reconciliation-tax/ .

[36] Scott Greenberg, “Options for Broadening the U.S. Tax Base,” Tax Foundation, Nov. 24, 2015, https://taxfoundation.org/options-broadening-us-tax-base/ .

[37] William McBride, “Debt Ceiling Deal Reduces Deficits in the Short Term but Delays a More Comprehensive Budget Reckoning,” Tax Foundation, May 31, 2023, https://taxfoundation.org/blog/debt-ceiling-deal/.

[38] Congressional Budget Office, “How the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 Affects CBO’s Projections of Federal Debt,” Jun. 9, 2023, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/59235#:~:text=Summary,affect%20federal%20spending%20and%20revenues .

[40] Alex Durante, “Tackling America’s Debt and Deficit Crisis Requires Social Security and Medicare Reform,” Tax Foundation, May 23, 2023, https://taxfoundation.org/medicare-social-security-reform-us-debt-deficits/ .

[41] Congressional Budget Office, “The 2023 Long-Term Budget Outlook,” Jun. 28, 2023, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/59014 .

[42] Congressional Budget Office, “An Update to the Budget Outlook: 2023 to 2033,” May 2023, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/59159 .

[43] Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, “Time is Running Out to Save Social Security and Medicare,” Mar. 31, 2023, https://www.crfb.org/press-releases/time-running-out-save-social-security-and-medicare .

[44] Ryan King, “McCarthy will convene a new commission to tackle federal budget,” Washington Examiner , May 31, 2023, https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/news/house/mccarthy-convene-new-commission-tackle-federal-budget .

[45] Alex Durante, “Tackling America’s Debt and Deficit Crisis Requires Social Security and Medicare Reform,” Tax Foundation, May 23, 2023, https://taxfoundation.org/medicare-social-security-reform-us-debt-deficits/ .

[46] David M. Walker, “A Fiscal Way Forward,” Real Clear Politics, Feb. 15, 2023, https://www.realclearpolitics.com/articles/2023/02/15/a_fiscal_way_forward_148858.html .

[47] James Buchanan, “The Balanced Budget Amendment: Clarifying the Arguments,” Constitutional Political Economy in a Public Choice Perspective , 1997, https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-94-011-5728-5_5 .

[48] James Buchanan, “Three Amendments: Responsibility, Generality, and Natural Liberty,” Cato Unbound, Dec. 4, 2005, https://www.cato-unbound.org/2005/12/04/james-m-buchanan/three-amendments-responsibility-generality-natural-liberty/ .

[49] Ryan Bourne, “Swiss Brake Offers Model for Preventing Debt Spiraling out of Control,” Cato Institute, Nov. 10, 2022, https://www.cato.org/commentary/swiss-brake-offers-model-preventing-debt-spiralling-out-control .

[50] Ryan Bourne, “Economists Oppose a Strict Balanced Budget Rule. Could the US Adopt a Sophisticated One?,” Cato Institute, Nov. 13, 2017, https://www.cato.org/blog/economists-oppose-strict-balanced-budget-amendment-could-us-adopt-sophisticated-one .

[51] Congressional Budget Office, “The 2023 Long-Term Budget Outlook,” Jun. 28, 2023, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/59014.

[52] Tax Foundation, “Talking Tax Reform: Debt, Deficits, and Tax Policy,” Jul. 21, 2023, https://taxfoundation.org/event/talking-tax-reform-debt-deficits-tax-policy/.

[53] Economicdataus.com, “Workers Per Retiree,” https://www.econdataus.com/workers.html .

[54] David Amaglobeli, Vitor Gaspar, and Era Dabla-Norris, “Getting Older but Not Poorer,” International Monetary Fund, March 2020, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2020/03/impact-of-aging-on-pensions-and-public-policy-gaspar .

[55] Eric Leeper, “Fiscal Dominance: How Worried Should We Be?,” Mercatus Center George Mason University, Apr. 3, 2023, https://www.mercatus.org/research/policy-briefs/fiscal-dominance-how-worried-should-we-be .

[56] Treasury Department, “Fiscal Data: Spending,” https://fiscaldata.treasury.gov/americas-finance-guide/federal-spending/ .

[57] Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, “Time is Running Out to Save Social Security and Medicare,” Mar. 31, 2023, https://www.crfb.org/press-releases/time-running-out-save-social-security-and-medicare .

[58] Social Security Administration, “A SUMMARY OF THE 2023 ANNUAL REPORTS,” https://www.ssa.gov/oact/TRSUM/ .

[59] The National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform, “The Moment of Truth,” The White House, December 2010, https://www.ssa.gov/history/reports/ObamaFiscal/TheMomentofTruth12_1_2010.pdf .

[60] Rob McClelland, “Differences Between the Traditional CPI and the Chained CPI,” Congressional Budget Office, Apr. 19, 2013, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/44088 .

[61] Stephen Miller, “2023 Social Security Wage Cap Jumps to $160,200 for Payroll Taxes,” SHRM, Oct. 13, 2022, https://www.shrm.org/ResourcesAndTools/hr-topics/compensation/Pages/2023-wage-cap-rises-for-social-security-payroll-taxes.aspx?linktext=September-CPI-Ticks-Down-as-Social-Security-Wage-Cap-Rises-for-2023&linktext=Inflation-Remains-Elevated-as-Social-Security-Wage-Cap-Rises-for-2023&mktoid=50021921 .

[62] Bill Cassidy, “Refusing to Reform Social Security Is a Plan — and a Bad One,” National Review, May 9, 2023, https://www.nationalreview.com/2023/05/refusing-to-reform-social-security-is-a-plan-and-a-bad-one/ .

[63] Congressional Budget Office, “Social Security Privatization: Experiences Abroad,” January 1999, https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/ftpdocs/10xx/doc1065/ssabroad.pdf .

[64] Johan Norberg, “How Sweden Saved Social Security,” CATO Institute, Feb. 22, 2023, https://www.cato.org/commentary/how-sweden-saved-social-security .

[65] Steven A. Sass, “Reforming the Australian Retirement System: Mandating Individual Accounts,” Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, April 2004, https://crr.bc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2004/04/gib_2.pdf .

[66] David Amaglobeli, Vitor Gaspar, and Era Dabla-Norris, “Getting Older but Not Poorer,” IMF, March 2020, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2020/03/impact-of-aging-on-pensions-and-public-policy-gaspar .

[67] OECD, “OECD Pensions Outlook 2018,” https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/finance-and-investment/oecd-pensions-outlook-2018_pens_outlook-2018-en#page4 .

[68] Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, “How to Reduce Medicare Spending Without Cutting Benefits,” May 17, 2017, https://www.crfb.org/blogs/how-reduce-medicare-spending-without-cutting-benefits .

[69] Rajender Agarwal, Joshua M. Liao, Ashutosh Gupta, and Amol S. Navathe, “The Impact Of Bundled Payment On Health Care Spending, Utilization, And Quality: A Systematic Review,” Health Affairs, January 2020, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00784#:~:text=The%20Centers%20for%20Medicare%20and%20Medicaid%20Services%20%28CMS%29,of%20care%20delivered%20during%20an%20episode%20of%20care .

[70] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “BPCI Advanced,” https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/bpci-advanced .

[71] Medicare.org, “How Does Medicare Advantage Reimbursement Work?” https://www.medicare.org/articles/how-does-medicare-advantage-reimbursement-work/#:~:text=As%20a%20beneficiary%20of%20a%20Medicare%20Advantage%20plan%2C,insurance%20company%20is%20responsible%20for%20covering%20that%20difference ..

[72] Congressional Budget Office, “Increase the Premiums Paid for Medicare Part B,” Dec. 7, 2022, https://www.cbo.gov/budget-options/58625 .

[73] Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, “The Benefits of Medicare Benefit Redesign,” Feb. 25, 2015, https://www.crfb.org/blogs/benefits-medicare-benefit-redesign .

[74] Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, “The Benefits of Medicare Benefit Redesign,” Feb. 25, 2015, https://www.crfb.org/blogs/benefits-medicare-benefit-redesign .

[75] Bipartisan Policy Center, “Domenici-Rivlin Protect Medicare Act,” Nov. 1, 2011, https://bipartisanpolicy.org/download/?file=/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Domenici-Rivlin-Protect-Medicare-Act-Backgrounder_0.pdf .

[76] Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, “Ryan and Wyden Offer Ambitious Health Care Proposal,” Dec. 15, 2011, https://www.crfb.org/blogs/ryan-and-wyden-offer-ambitious-health-care-proposal .

[77] Erica York, “Inflation Reduction Act’s Price Controls Are Deterring New Drug Development,” Tax Foundation, Apr. 26, 2023, https://taxfoundation.org/inflation-reduction-act-medicare-prescription-drug-price-controls/ .

[78] Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, “Two Ways to Reduce Prescription Drug Costs,” Jul. 26, 2021, https://www.crfb.org/blogs/two-ways-reduce-prescription-drug-costs .

[79] Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, “Injecting Price Competition into Medicare Part B Drugs,” Jul. 2, 2021, https://www.crfb.org/sites/default/files/managed/media-documents2022-02/HSI_PartBDrugs.pdf .

[80] Garrett Watson, Erica York, Huaqun Li, Cody Kallen, William McBride, and Alex Muresianu, “Details and Analysis of President Biden’s Fiscal Year 2024 Budget Proposal,” Tax Foundation, Mar. 23, 2023, https://taxfoundation.org/biden-budget-tax-proposals-analysis/ .

[81] Congressional Budget Office, “Long-Term Budget Projections,” https://www.cbo.gov/data/budget-economic-data#1 .

[82] William McBride, Huaqun Li, Garrett Watson, Alex Durante, Erica York, and Alex Muresianu, “Details and Analysis of a Tax Reform Plan for Growth and Opportunity,” Tax Foundation, updated Jun. 29, 2023, https://taxfoundation.org/growth-opportunity-us-tax-reform-plan/ .

[83] William McBride, Huaqun Li, Garrett Watson, Alex Durante, Erica York, and Alex Muresianu, “Details and Analysis of a Tax Reform Plan for Growth and Opportunity,” Tax Foundation, Feb. 14, 2023, https://taxfoundation.org/growth-opportunity-us-tax-reform-plan/ .

[84] William McBride and Daniel Bunn, “Repealing Inflation Reduction Act’s Energy Credits Would Raise $663 Billion, JCT Projects,” Tax Foundation, Jun. 7, 2023, https://taxfoundation.org/inflation-reduction-act-green-energy-tax-credits-analysis/ ; William McBride, Alex Muresianu, Erica York, and Michael Hartt, “Inflation Reduction Act One Year After Enactment,” Tax Foundation, Aug. 16, 2023, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/federal/inflation-reduction-act-taxes/.

[85] Garrett Watson, Erica York, Cody Kallen, and Alex Durante, “Details and Analysis of Canceling the Scheduled Business Tax Increases in Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” Tax Foundation, Nov. 1, 2022, https://taxfoundation.org/tax-cuts-jobs-act-business-tax-increases/ .

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 20 August 2019

Twin deficit hypothesis and reverse causality: a case study of China

- Umer Jeelanie Banday 1 &

- Ranjan Aneja 1

Palgrave Communications volume 5 , Article number: 93 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

13k Accesses

12 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

A Correction to this article was published on 01 October 2019

This article has been updated

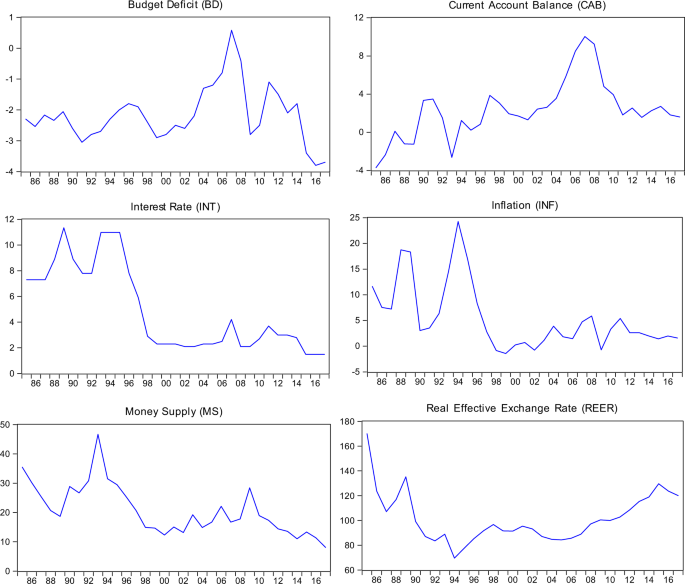

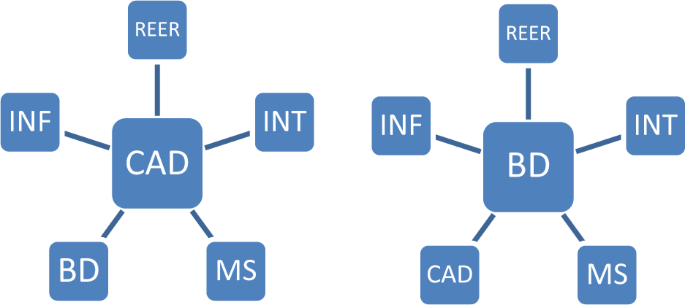

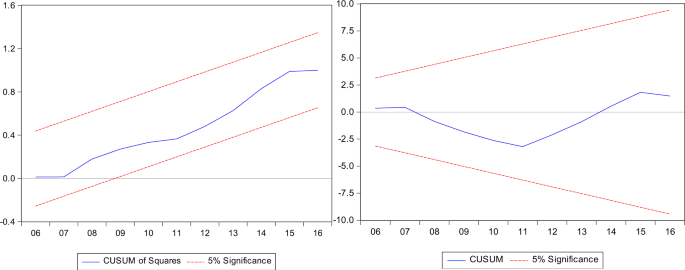

This paper analyses the causal relationship between budget deficit and current account deficit for the Chinese economy using time series data over the period of 1985–2016. We initially analyzed the theoretical framework obtained from the Keynesian spending equation and empirically test the hypothesis using autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) bounds testing and the Zivot and Andrew (ZA) structural break for testing the twin deficits hypothesis. The results of ARDL bound testing approach gives evidence in support of long-run relationship among the variables, validating the Keynesian hypothesis for the Chinese economy. The result of Granger causality test accepts the twin deficit hypothesis. Our results suggest that the negative shock to the budget deficit reduces current account balance and positive shock to the budget deficit increases current account balance. However, higher effect growth shocks and extensive fluctuation in interest rate and exchange rate lead to divergence of the deficits. The interest rate and inflation stability should, therefore, be the target variable for policy makers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Cyclical dynamics and co-movement of business, credit, and investment cycles: empirical evidence from India

Monetary policy models: lessons from the Eurozone crisis

A systematic review of investment indicators and economic growth in Nigeria

Introduction.

Fiscal and monetary strategies, when executed lucidly, assume a conclusive part in general macroeconomic stability. The macroeconomic theory which assumes an ideal connection between budget (or fiscal) deficit and trade balance is known as twin deficit hypothesis. The growing literature on twin deficit hypothesis (TDH) has been theoretically and empirically researched by researchers like Kim and Roubini ( 2008 ), Darrat ( 1998 ), Miller and Russek ( 1989 ), Lau and Tang ( 2009 ), Abbas et al. ( 2011 ), Bernheim and Bagwell ( 1988 ), Lee et al. ( 2008 ), Corestti and Muller ( 2006 ), Altintas and Taban ( 2011 ), and Banday and Aneja ( 2016 ).