Breastfeeding

Explore the latest in breastfeeding, including advances in understanding ways to encourage it and its long-term effects on child health.

Publication

Article type.

This systematic review and meta-analysis investigates the association between provision of a relaxation intervention and lactation outcomes.

This randomized clinical trial examines whether breast milk enemas can shorten the time to complete meconium evacuation and achievement of full enteral feeding for infants born preterm in China.

This cross-sectional study examines the prevalence of zero-food children (children who do not consume any food other than breast milk) aged 6 to 23 months across 92 low- and middle-income countries.

- Delivering on the Promise of Human Milk for Extremely Preterm Infants in the NICU JAMA Opinion January 30, 2024 Child Development Neonatology Nutrition Pediatrics Critical Care Medicine Full Text | pdf link PDF

This randomized clinical trial compares the effect of donor human milk on neurodevelopmental outcomes at 22 to 26 months’ corrected age compared with preterm infant formula among extremely preterm infants who received minimal maternal milk.

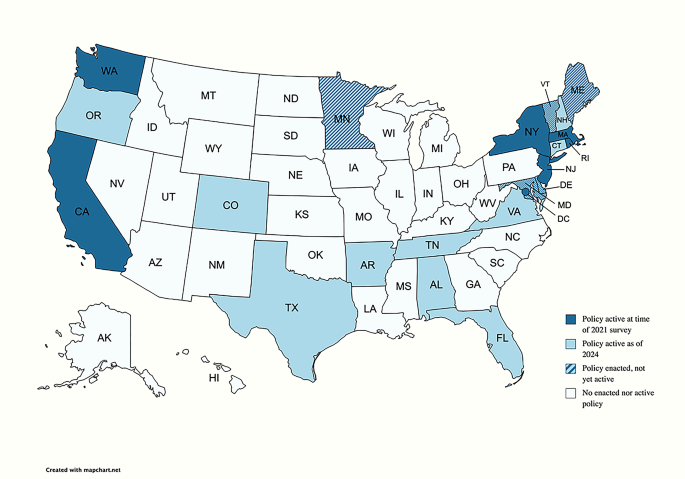

This study investigates whether ACA policies to increase access to breast pumps and lactation care were associated with innovation in the market for breast pumps.

This cross-sectional study analyzes lactation support policies at the top 50 US schools of medicine.

- Enhancing Lactation Accommodations for Physicians—An Opportunity for Tangible Investments in Our Workforce JAMA Network Open Opinion August 8, 2023 Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion Pregnancy Obstetrics Women's Health Obstetrics and Gynecology Full Text | pdf link PDF open access

This cohort study examines the association between improved lactation accommodation support and physician satisfaction at a large, urban academic health system.

This randomized clinical trial examines the development of egg allergy and sensitization in breastfed infants whose mothers ate eggs in the first 5 days after delivery.

This Viewpoint discusses 2 new programs of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development’s Pediatric Growth and Nutrition Branch that apply an ecological approach to understanding nutrition and public health.

This Patient Page describes the challenges of returning to work while breastfeeding, tips on how to transition back to work, and the advantages of breast milk.

- Maternal Opioid Treatment After Delivery Poses Low Risk to Infants JAMA News March 29, 2023 Neonatology Substance Use and Addiction Medicine Opioids Pediatrics Full Text | pdf link PDF free

This Viewpoint examines the current state of telelactation and its role in digital equity.

- Majority of Infant Formula Health Claims Are Poorly Supported JAMA News March 1, 2023 Child Development Neonatology Nutrition Pediatrics Full Text | pdf link PDF

This randomized clinical trial examines whether an exclusive human milk diet has an effect on gut bacterial richness, diversity, and proportions of specific taxa in preterm infants from enrollment to 34 weeks’ postmenstrual age.

This JAMA Insights Clinical Update reviews the risk factors for and symptoms of lactational mastitis and provides a potential treatment algorithm.

This cohort study investigates the presence of COVID-19 vaccine mRNA in the expressed breast milk of lactating individuals who received the vaccination within 6 months after delivery.

This review highlights recent literature regarding lactation in otolaryngology patients, including medication, radiologic imaging, perioperative considerations, and subspecialty-specific considerations for lactating patients.

This study aims to compare the antibody response in human milk after vaccination with mRNA-based and vector-based vaccines.

Select Your Interests

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

Disclaimer » Advertising

- HealthyChildren.org

- Previous Article

- Next Article

Milk Production and Transfer

Neonatal weight and output assessment, glucose stabilization, hyperbilirubinemia, immune development and the microbiome, supplementation, health system interventions: the baby-friendly hospital initiative, limitations and implications for future research, conclusions, acknowledgment, evidence-based updates on the first week of exclusive breastfeeding among infants ≥35 weeks.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- CME Quiz Close Quiz

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Get Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Lori Feldman-Winter , Ann Kellams , Sigal Peter-Wohl , Julie Scott Taylor , Kimberly G. Lee , Mary J. Terrell , Lawrence Noble , Angela R. Maynor , Joan Younger Meek , Alison M. Stuebe; Evidence-Based Updates on the First Week of Exclusive Breastfeeding Among Infants ≥35 Weeks. Pediatrics April 2020; 145 (4): e20183696. 10.1542/peds.2018-3696

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

The nutritional and immunologic properties of human milk, along with clear evidence of dose-dependent optimal health outcomes for both mothers and infants, provide a compelling rationale to support exclusive breastfeeding. US women increasingly intend to breastfeed exclusively for 6 months. Because establishing lactation can be challenging, exclusivity is often compromised in hopes of preventing feeding-related neonatal complications, potentially affecting the continuation and duration of breastfeeding. Risk factors for impaired lactogenesis are identifiable and common. Clinicians must be able to recognize normative patterns of exclusive breastfeeding in the first week while proactively identifying potential challenges. In this review, we provide new evidence from the past 10 years on the following topics relevant to exclusive breastfeeding: milk production and transfer, neonatal weight and output assessment, management of glucose and bilirubin, immune development and the microbiome, supplementation, and health system factors. We focus on the early days of exclusive breastfeeding in healthy newborns ≥35 weeks’ gestation managed in the routine postpartum unit. With this evidence-based clinical review, we provide detailed guidance in identifying medical indications for early supplementation and can inform best practices for both birthing facilities and providers.

Exclusive breastfeeding significantly improves maternal and child health. Although US pediatricians’ recommendations are increasingly aligned with American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) policies, their optimism about the potential for breastfeeding success has declined. 1 To maintain familiarity with the benefits of breastfeeding and the skills necessary to promote this positive health intervention, providers caring for neonates and/or new mothers need updated evidence-based information and tools to assess and manage breastfeeding.

In this review, we provide new evidence from the past 10 years on the following topics relevant to exclusive breastfeeding: milk production and transfer, neonatal weight and output assessment, glucose stabilization, hyperbilirubinemia, immune development and the microbiome, supplementation, and health system interventions. We focus on the early days of exclusive breastfeeding in healthy newborns ≥35 weeks’ gestation managed in the routine postpartum unit. 2 – 6 Tables 1 through 3 and Fig 1 provide summaries based on evidence and authors’ recommendations to provide concise and clear bullets on optimal management. The search strategy and tables of evidence for milk production and transfer, neonatal weight and output assessment, management of glucose, and hyperbilirubinemia are summarized in the Supplemental Information .

Breastfeeding Assessment During the First Postnatal Week

—, not applicable.

Mother, Infant, and Systems-Level Risk Factors for Breastfeeding Difficulties

Adapted from Evans A, Marinelli KA, Taylor JS; Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine. ABM clinical protocol #2: guidelines for hospital discharge of the breastfeeding term newborn and mother: “The going home protocol,” revised 2014. Breastfeed Med . 2014;9(1):4.

Risk Factors for Hypoglycemia

Adapted from Thornton PS, Stanley CA, De Leon DD, et al; Pediatric Endocrine Society. Recommendations from the Pediatric Endocrine Society for evaluation and management of persistent hypoglycemia in neonates, infants, and children. J Pediatr . 2015;167(2):241 and Adamkin DH; Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Postnatal glucose homeostasis in late-preterm and term infants. Pediatrics . 2011;127(3):576.

Supplementation decision algorithm.

Three stages of milk production, lactogenesis I to III, are defined on the basis of volume and composition of milk. For volume, Fig 2 shows estimated daily milk production. 16 In relation to composition, human milk changes dramatically over the first week of lactation. Colostrum, which is produced during the initial stage of lactation (lactogenesis I) in the first days after birth, contains more protein than mature milk. This highly dense early milk has a high concentration of immunoglobulins, activated macrophages, lymphocytes, neutrophils, and growth factors with essential roles in development of gut-associated lymphoid tissue. 17 As milk volume increases (lactogenesis II), sodium concentration and the sodium/potassium ratio decline rapidly with increased secretory activity of the lactocytes and closure of tight cellular junctions. 18 Production of fat-rich, higher-calorie mature milk typically occurs by ∼10 days post partum (lactogenesis III).

Milk volume estimated by breast milk transfer over the first 6 days in vaginal and cesarean births. *Adjusted difference P < .05. Adapted from Evans KC, Evans RG, Royal R, Esterman AJ, James SL. Effect of caesarean section on breast milk transfer to the normal term newborn over the first week of life. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed . 2003;88(5):F382.

Most, but not all, women experience lactogenesis II, referred to as “milk coming in,” by 72 hours post partum. In the Infant Feeding Practices Survey II, 19% of multiparous women and 35% of primiparous women reported milk coming in on day 4 or later. 19 Reasons for delayed lactogenesis II include primiparity, cesarean delivery, and BMI > 27. 20 – 22 Conditions associated with obesity, such as advanced maternal age (possibly related to reduced fertility associated with obesity-variant polycystic ovarian syndrome) and excessive gestational weight gain, may also lead to a delay. 23 , 24 Delayed lactogenesis II is associated with neonatal weight loss >10%. 20

Occasionally, a woman does not experience lactogenesis II and only produces small volumes of milk (prevalence 5%–8%). 19 , 25 The differential diagnosis includes breast pathology, previous breast surgery (with damage to ducts or augmentation for hypoglandular breasts), developmental anomalies of the breast tissue, hormonal disruptions (such as retained placental fragments and pituitary insufficiency, including Sheehan’s syndrome, hypothyroidism, polycystic ovarian syndrome, or theca-lutein ovarian cysts), and toxins (such as excessive tobacco exposure). 26 Occasionally, strategies described here to improve milk production and transfer are not effective, and long-term supplementation with either donor milk or infant formula is medically necessary.

Milk expression is safely and effectively achieved by both manual and mechanical methods and can be used to maintain milk supply in the event of separation from the infant. 27 Hand expression also facilitates milk transfer for the infant learning to breastfeed; both latch and an effective suckling pattern are key. Among mothers of term infants who were feeding poorly, those randomly assigned to hand expression versus electric pumps were more likely to still be breastfeeding at 2 months (96.1% vs 72.7%; P = .02). 28 Infrequent or inadequate signaling due to ineffective or infrequent breastfeeding or milk expression may trigger the autocrine-paracrine mechanisms of halting milk production and dismantling the mammary gland architecture. 29 Milk removal, either via direct breastfeeding or expression, is essential for continuation of milk production.

Some women experience engorgement with lactogenesis II. There is limited evidence regarding the optimal management of engorgement. However, because severe engorgement can impede infant removal of milk, breastfeeding mothers should learn hand expression and reverse pressure softening, which is positive pressure to the central subareolar region, 30 before discharge from maternity care. 31 , 32 If a mother is unable to hand express or her infant is unable to latch, she may require a breast massage 33 and/or use of an electric breast pump.

The components of a comprehensive breastfeeding assessment are described in Table 1 . 12 , 34 It is important to note that a mother’s pumped milk volume may be an inaccurate estimate of milk transfer because transfer also depends on the infant’s capabilities. Associated risk factors for suboptimal milk transfer are listed in Table 2 .

Painful latching deserves special attention as a contributor to low supply, impaired milk transfer, and early cessation of breastfeeding. 35 In an ultrasound study in which breastfeeding mothers with nipple pain were compared with those without, nipple pain was associated with abnormal infant tongue movement, restricted nipple expansion, and lower rates of milk transfer. 36 In a retrospective audit of an Australian breastfeeding center, 36% of visits were for nipple pain. 37 A US study revealed that nipple pain and trauma were among the most frequently cited reasons for early weaning. In a study of >1600 women with singleton births, ∼10% had nipple pain that persisted at postpartum day 7; 72% was attributed to inappropriate positioning and latching, 23% to tongue-tie in the infant, and 4% to oversupply. Women who received treatment recovered within 1 to 2 weeks, and 6-week exclusive breastfeeding rates were no different from those of mothers without nipple pain. 38 Although high-quality randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are needed, frenotomy has been shown to reduce maternal nipple pain in infants with congenital ankyloglossia. 39 There is no evidence that any one topical treatment is superior 40 ; the mainstay of management for nipple pain and fissuring is assistance with positioning and latching. 41

Healthy newborns experience physiologic weight loss after birth, 42 , 43 which, in the exclusively breastfed infant, typically plateaus as the mother’s milk transitions from lactogenesis I to lactogenesis II. The addition of infant formula, either as a supplement or in the form of exclusive formula feeding, is associated with rapid weight gain. This nonphysiologic weight trajectory is associated with childhood obesity. 44 Exclusive direct breastfeeding is inversely associated with the velocity of weight gain throughout the first year of life. 45 In one prospective cohort study of >300 newborns, weight gain >100 g during the first week after birth was independently associated with overweight status at age 2 (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 2.3; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.1 to 4.8). 44

Early infant weight loss should be evaluated in the context of the clinical status of the infant and the mother. Nomograms for newborn weight have been developed by using data from >100 000 healthy, exclusively breastfed infants in California. 46 Individual infant weights can be plotted against these nomograms by using the Newborn Early Weight Tool (NEWT) ( https://www.newbornweight.org ). Weight loss trajectory over time, combined with clinical information, provides a robust context for evidence-based decision-making. 47 Weight loss in the >75th percentile on NEWT nomograms for mode of delivery and infant age should prompt a thorough evaluation.

A term newborn’s weight is 75% water, compared with 60% for an adult. Urine output is usually low in the first 1 to 2 days after birth, after which a physiologic diuresis and loss of up to 7% to 10% of birth weight occurs. 48 , 49 Insufficient milk production and/or transfer in the exclusively breastfed newborn can contribute to excessive weight loss in the first few days of life. Low milk supply, often exacerbated by poor feeding or difficulty in suckling, correlates with elevated milk sodium levels. 50 Exclusively breastfed infants, especially those born via cesarean delivery, are at increased risk for greater weight loss, dehydration, and hypernatremia. 51 , 52 In a systematic review of hypernatremia among breastfed infants, significant risk factors included weight loss >10%, cesarean delivery, primiparity, breast anomalies, reported breastfeeding problems, excessive prepregnancy maternal weight, delayed first breastfeeding, lack of previous breastfeeding experience, and low maternal education. 53 Prevention strategies included daily weights coupled with lactation support during the first 4 to 5 days after birth.

Early weight loss nomograms for exclusively breastfed newborns can help identify those infants at risk for hypernatremic dehydration (HD), 54 , 55 a rare condition characterized by lethargy, restlessness, hyperreflexia, spasticity, hyperthermia, and seizures, with an estimated incidence of 20 to 70 per 100 000 births and up to 223 per 100 000 births among primiparous mothers. 56 Use of charts for weight loss with SD scores specifically to detect HD, combined with a policy of weight checks on days 2, 4, and 7 of life, had high sensitivity (97%) and specificity (98.5%) to detect HD. 47 However, given the low incidence of HD, the positive predictive value (PPV) of repeated weight checks alone was only 4.4%. 56

Importantly, elimination patterns during the first 2 days of life are neither sensitive nor specific as measures of infant intake. 49 Infants may be voiding and stooling despite insufficient intake or, more commonly, have decreased voiding and stooling compared with exclusively formula-fed infants despite adequate intake. In a cohort study of 313 infants, the frequency of urination and stooling was significantly decreased among exclusively breastfed infants compared with exclusively formula-fed infants during the first 3 days of life then rose and significantly surpassed that of exclusively formula-fed infants by day 6 of life. 49 Another prospective cohort study of 280 mother-infant pairs examined elimination patterns in relation to excessive weight loss (>10%) between 72 and 96 hours after birth. 48 The strongest association with weight loss >10% was with <4 stools after 72 hours or maternal perception of delayed lactogenesis II. Although term and late-preterm infants generally pass meconium within 48 hours (76%–83% in a study of 198 infants), delayed passage of meconium can be a marker for insufficient milk intake. 57 Correlations between infants’ intake and elimination are more reliable after the first 3 days (lactogenesis II).

To prepare for transitional energy needs, the third-trimester fetus stores glycogen, manufactures catecholamines, and deposits brown fat. Healthy newborns use these stores to maintain thermoregulation and meet their energy needs through metabolism of brown fat and the release of counterregulatory hormones such as glucagon, epinephrine, cortisol, and growth hormone. Combined with declining insulin secretion, these hormones mobilize glucose and alternative fuels, such as lactate and ketone bodies, to support organ functions. 58 , 59

Because oral intake is not the main energy source for healthy term neonates in the first days after birth, physiologic volumes of colostrum (16 kcal/oz) are sufficient to meet metabolic demands. As glycogen stores are depleted, coinciding with the transition from colostrum to mature milk, newborns transition from a catabolic state to reliance on enteral feeds, with approximately half of the caloric content derived from fat. 60

After placental detachment, neonatal glucose levels reach a physiologic nadir in the first hours after birth and then typically rise to adult levels a few days later. The threshold for neonatal glucose that is associated with neurotoxicity is unclear; a 2008 National Institutes of Health workshop concluded that “there is no evidence-based study to identify any specific plasma glucose concentration (or range of glucose values) to define pathologic hypoglycemia.” 61 In one cohort study, treatment of asymptomatic newborn hypoglycemia to maintain blood glucose levels >47 mg/dL had no effect on cognitive performance at 2 years; however, at 4.5 years, there were dose-dependent concerns regarding visual motor and executive function, with the highest risk in children exposed to severe (<36 mg/dL),and recurrent (≥3 episodes) hypoglycemia. 62 , 63

In the first hours after birth, healthy term neonates compensate for relatively low glucose levels by decreasing insulin production and increasing glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, and ketone production. Among at-risk newborns, early skin-to-skin care plus early feeding and blood glucose assessment at 90 minutes supports glucose homeostasis and is associated with decreased risk of hypoglycemia and NICU admission. 64 In a Cochrane review, early skin-to-skin contact increased glucose levels by 10.49 (95% CI 8.39 to 12.59) mg/dL or 0.6 (0.5 to 0.7) mmol/L. 65 Conversely, practices that separate the mother and infant and delay the first feeding increase hypoglycemia risk.

Glucose monitoring is recommended for infants with risk factors ( Table 3 ) and for any infant who exhibits symptoms of hypoglycemia. 66 Because operational thresholds for treating hypoglycemia and target glucose levels are not defined, clinical recommendations vary. Infants who require early or more frequent feedings should be supported to breastfeed and/or receive expressed milk. Authors of multiple studies confirm the benefits of using glucose gel rather than formula as an initial treatment of low glucose levels, and this practice has become increasingly commonplace. 67 – 73 Some institutions use pasteurized donor human milk (PDHM) as a treatment of hypoglycemia; however, there are, as yet, no published studies describing outcomes of this practice. The option of antenatal milk expression for lower-risk women with preexisting or gestational diabetes may also be considered because this technique may preserve exclusive breastfeeding without adversely affecting perinatal outcomes. 74 Infants requiring intravenous glucose should breastfeed, when able, during the therapy.

Persistent or late-onset hypoglycemia (>48 hours after birth) can occur in the setting of congenital endocrine disorders or, more commonly, perinatal stress due to birth asphyxia, intrauterine growth restriction, maternal preeclampsia, 75 or persistent problems establishing breastfeeding. 76 Infants with these risk factors may be more vulnerable to insufficient feeding, so skilled assessment is essential.

Management of hyperbilirubinemia in the exclusively breastfed newborn depends on whether the excess in bilirubin is pathologic or physiologic. Neonatal bilirubin levels rise after birth because of physiologic immaturity of glucuronyl transferase, which is exaggerated with each decreasing week of gestational age. Exclusively breastfed infants have higher serum bilirubin levels than formula-fed infants, possibly because of differences in fluid intake and bilirubin excretion and increased enterohepatic resorption of bilirubin. 77 Some individuals may also have a genetic predisposition to higher bilirubin levels. 78 , 79 Bilirubin is an antioxidant, and it has been hypothesized that moderate increases in bilirubin levels may be protective for the transition to extrauterine life. 77 , 80

In contrast, pathologic hyperbilirubinemia resulting from insufficient breastfeeding, sometimes referred to as breastfeeding jaundice, is better defined as suboptimal intake jaundice. 77 In the United States and Canada, it is recommended that all neonates undergo bilirubin risk screening at least once before hospital discharge. 81 The Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine and the AAP advise the use of Bhutani curves to assess risk and need for treatment of hyperbilirubinemia; clinical tools are available on mobile device applications. 77 , 81 , 82 This approach has led to a decrease in severe pathologic hyperbilirubinemia 83 ; however, concerns for overtreatment and the potential harm of phototherapy have arisen recently. 84 Using subthreshold bilirubin levels to initiate phototherapy as a mechanism to prevent readmission is not recommended because this approach increases length of stay and results in many infants receiving unnecessary treatment to reduce each case of readmission. 85

Breastfed infants with hyperbilirubinemia require assessment of milk production and transfer, feeding frequency, and neonatal weight loss. 86 – 91 If there is pathologic hyperbilirubinemia, and infant intake at the breast is sufficient, exclusive breastfeeding should be continued while the infant receives phototherapy. Although supplementation with infant formula may decrease the bilirubin level and risk of readmission for phototherapy, 85 it will also interfere with the establishment and continuation of breastfeeding. 92 If intake at the breast is insufficient and supplementation is medically necessary, expressed maternal milk is preferred. Despite the current lack of data on its benefits in reducing hyperbilirubinemia in term infants, the use of PDHM to preserve exclusive human-milk feeding is increasing. 93

Phototherapy for neonatal jaundice and concerns about insufficient milk can be anxiety provoking for parents, even in a supportive environment, and can be disruptive to successful breastfeeding. 94 Practices to minimize mother-infant separation, including providing phototherapy in the same room and maintaining safe skin-to-skin care with the infant’s mother, also promote exclusive breastfeeding. 95

Early colostrum and exclusive breastfeeding establish an optimal and intact immune system. Unlike infant formula, human milk has a dynamic composition of both macro- and micronutrients that varies within a feed, diurnally, and over the course of lactation. Protective proteins abound in human milk, including lactoferrin, secretory immunoglobulin A, transforming growth factor-β, and α-lactalbumin. These factors promote development of the infant’s immune system. 96 Additionally, lactoferrin has unique antibacterial properties important in the prevention of sepsis. Unique nonnutritive oligosaccharides that are specific to the mother-infant pair’s shared environment and exposures prevent binding of pathogenic bacteria and promote a healthy microbiome in the gut. 97 Differences in immune cell distributions based on neonatal diet can be detected through 6 months of age, with natural killer cells most significantly affected. 98

During vaginal birth, the newborn’s intestine and mucosal surfaces are colonized with maternal microbes that act synergistically with bioactive factors in mother’s milk to establish a robust lymphoid follicle replete with a healthy balance of T helper cells. 99 , 100 Surgical delivery is associated with aberrant colonization, which may lead to differences in the mother’s milk microbiome 101 only partially restored by vaginal secretions. 102 Formula supplementation may effect the most change in the newborn’s microbiome 103 , 104 and immune development. These basic science findings are supported by clinical studies.

Given the multiple mechanisms through which exclusive human milk impacts gut development, formula supplementation should always be avoided when the mother’s own milk is available. Although an exploratory study of early limited supplementation with extensively hydrolyzed formula followed by a return to exclusive breastfeeding did not reveal differences in the developing microbiome ( N = 15), 105 a longitudinal study among infants exclusively breastfeeding at 3 months ( N = 579) revealed alterations in the microbiome among infants exposed to formula as neonates ( n = 179). 106 Just as antimicrobial stewardship requires appropriate use of antibiotics, 107 supplementation stewardship requires judicious use of formula when medically indicated.

A systematic review of healthy, term, breastfed newborns revealed no benefit from routine supplementation with foods or fluids in the early postpartum period. 108 These findings are consistent with consensus recommendations for exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months, followed by continued breastfeeding with the addition of complementary foods until at least 12 months of age. 2 , 109 – 111 Early introduction of supplemental formula is associated with a greater than twofold increase in risk of early cessation of breastfeeding even when controlling for confounding variables. 112 – 114 Among almost 1500 women in the Infant Feeding Practices Study II, only early exclusive breastfeeding remained significant for achieving intended breastfeeding duration (aOR 2.3; 95% CI 1.8 to 3.1) after adjustment for relevant hospital practices. 113 This finding may be due in part to the supply and demand nature of milk production and the role of suckling, oxytocin release, and milk removal in establishing lactation.

If supplemental feeds are medically indicated, they should be accompanied by manual or mechanical milk expression, recognizing that direct breastfeeding usually provides more complete milk removal. 115 In a pilot RCT ( N = 40), early limited formula supplementation for infants with ≥5% weight loss increased exclusive breastfeeding at 3 months post partum. 116 In a subsequent larger study ( N = 164), early limited supplementation did not affect overall breastfeeding at 1 or 6 months but slightly increased rates of formula use at 1 month (36.7% vs 22.4%; P = .08), 105 decreased breastfeeding at 12 months (30% vs 48%; risk difference −18% [CI −34% to −3%]), and shortened the time to breastfeeding cessation (hazard ratio 0.65; 95% CI 0.43 to 0.97). 117

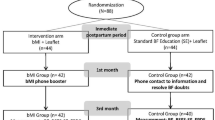

Because evidence continues to accrue that supplementation in the first days after birth has major health risks, 103 , 106 judicious use of supplementation is a critical goal, with a return to exclusivity whenever possible. If supplementation is indicated ( Fig 1 ), options in order of preference are (1) expressed milk from the infant’s own mother, 4 (2) PDHM, and (3) commercial infant formulas. The potential risks and benefits of these options should be considered in the context of the infant’s age, the volume required, and the impact on the establishment of breastfeeding. 4

Methods of supplemental feeding include spoon or cup feeds, supplemental nursing systems, syringe feeds, and paced bottle feeds. Methods should be tailored to staff training and family preferences. 7 Among late-preterm newborns, there is evidence that some may be more susceptible to feeding problems when supplemented via a bottle; in an RCT in which the 2 methods were compared, cup feeding was associated with a longer duration of exclusive breastfeeding compared with bottle-feeding. 118 Among term newborns, the manner in which supplementation is delivered, whether a bottle or alternative devices, has no apparent impact on continuation of breastfeeding. 119 If the supplement is the mother’s own expressed milk, avoidance of bottles and nipples may preserve a longer duration of breastfeeding, especially among late-preterm newborns. 120

To ensure milk removal, which is key to establishing a milk supply, a mother should be assisted to express milk each time her infant is supplemented, even if the infant is also “practicing” at the breast. 4 “Hands on” pumping, combining breast massage with pumping, has been shown to increase milk production in mothers of preterm infants who are hospitalized. 121

Physiologic early infant feeding is facilitated by keeping mothers close to their infants, beginning with skin-to-skin care immediately after birth and continuing with 24-hour rooming-in and feeding on cue. These are core practices of the recently updated World Health Organization’s Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding of the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI). 7 Feeding on cue or “responsive feeding” is associated with more frequent breastfeeding throughout the day, more exclusive breastfeeding up to 6 months and beyond, 122 – 124 and decreased likelihood of abnormal rapid weight gain in infancy. 125

Several major health organizations, including the US Preventive Services Task Force and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, have generated systematic reviews and quality improvement (QI) reports that demonstrate the positive impact of the BFHI on breastfeeding outcomes. 10 , 13 , 14 Implementation of maternity care practices aligned with any component of the BFHI is associated with improved in-hospital and postdischarge breastfeeding rates. 11 , 13 , 126 Best Fed Beginnings increased exclusive breastfeeding initiation from 39% to 61% ( t = 9.72; P < .001) at 89 hospitals over 2 years. 127 The Community and Hospitals Advancing Maternity Care Practices initiative reported that the BFHI helped to reduce racial disparities in breastfeeding in southern US states. 128

Since the initial implementation of the BFHI, safety concerns have emerged, including case reports of inadvertent bed-sharing, suffocation, falls, and increased risk of neonatal jaundice. 3 , 129 In this context, the World Health Organization conducted an extensive evidence-based review. 7 , 130 Key differences in the revised Ten Steps include highlighting the Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes, the need to collect ongoing data, a focus on safety and surveillance (especially as it relates to skin-to-skin care and rooming-in), and acknowledgment that there is insufficient evidence to limit pacifiers and other artificial nipples.

Step 10 of the BFHI requires a direct connection between the delivery hospital and the community for ongoing support. Referral for outpatient support as well as provision of contact information for those who can manage breastfeeding problems is paramount.

Given the importance of exclusive breastfeeding for maternal and child health, both intent and initiation are increasing. However, maternal conditions linked with delayed lactogenesis, such as advanced maternal age, obesity, and fertility treatment, are increasingly common. Priority research areas to help families meet their breastfeeding goals include accurate identification of women with risk factors for delay or absence of lactogenesis, more sensitive methods of identifying at-risk newborns, and exploration of the implications of early limited formula supplementation on infant outcomes such as ontogeny of the immune system and the microbiome, maternal self-efficacy, and continued breastfeeding.

Health care professionals’ support is critical for families to meet their infant feeding goals and achieve optimal health outcomes. All physicians who care for new mothers and infants need skills to evaluate early breastfeeding, perform maternal and infant risk stratification, understand the range of potential interventions in the context of the risk/benefit ratio of supplementation, and ensure appropriate follow-up.

Most mothers can produce adequate colostrum and mature milk, and most newborns are able to breastfeed exclusively. Nevertheless, conditions that require medical supplementation are common and important to recognize. The decision to supplement with infant formula requires thoughtful analysis of the risks and benefits, with consideration of the family’s informed choice. Early-term and late-preterm newborns are at a higher risk of complications. Therefore, more careful monitoring, detailed assessments, and case-based interventions are warranted. Further research is needed to identify the best methods to support exclusive breastfeeding in high-risk populations.

We thank Delali Lougou for organizing the articles used in this article to provide the original framework for the authors’ review.

Drs Feldman-Winter, Kellams, and Stuebe conceptualized and designed the review of the literature, conducted the literature review and analysis, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr Peter-Wohl made substantial contributions to the acquisition of data and to the analysis and interpretation of data, drafted the article, and revised it critically for important intellectual content; Dr Taylor made substantial contributions to conception and design and made critical revisions; Drs Lee and Terrell made substantial contributions to the design and to the acquisition of data and made critical revisions for important intellectual content; Drs Meek and Noble and Ms Maynor made substantial contributions to the conception, design, and analysis and interpretation of data and revised the article critically for important intellectual content; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FUNDING: No external funding.

American Academy of Pediatrics

adjusted odds ratio

Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative

confidence interval

hypernatremic dehydration

Newborn Early Weight Tool

pasteurized donor human milk

positive predictive value

quality improvement

randomized controlled trial

Competing Interests

Supplementary data.

Advertising Disclaimer »

Citing articles via

Email alerts.

Affiliations

- Editorial Board

- Editorial Policies

- Journal Blogs

- Pediatrics On Call

- Online ISSN 1098-4275

- Print ISSN 0031-4005

- Pediatrics Open Science

- Hospital Pediatrics

- Pediatrics in Review

- AAP Grand Rounds

- Latest News

- Pediatric Care Online

- Red Book Online

- Pediatric Patient Education

- AAP Toolkits

- AAP Pediatric Coding Newsletter

First 1,000 Days Knowledge Center

Institutions/librarians, group practices, licensing/permissions, integrations, advertising.

- Privacy Statement | Accessibility Statement | Terms of Use | Support Center | Contact Us

- © Copyright American Academy of Pediatrics

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

The Benefits of Breast Feeding

Affiliation.

- 1 Institute for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Nutrition and Liver Diseases, Schneider Children's Medical Center, Petach Tivka, and Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel.

- PMID: 27336781

- DOI: 10.1159/000442724

Human milk is considered as the gold standard for infant feeding. Breastfeeding advantages extend beyond the properties of human milk itself. A complex of nutritional, environmental, socioeconomic, psychological as well as genetic interactions establish a massive list of benefits of breastfeeding to the health outcomes of the breastfed infant and to the breastfeeding mother. For this reason, exclusive breastfeeding is recommended for about 6 months and should be continued as long as mutually desired by mother and child. The evidence in the literature on the effect of breastfeeding on health outcomes is based on observational studies due to the fact that it is unethical and practically impossible to randomize children to be breastfed or not. As such, multiple confounders cloud the evidence and one must base conclusions on the accumulating evidence when not contradictory and on the only intervention study, PROBIT (Promotion of Breastfeeding Intervention Trial). This review highlights some of the health outcomes related to breastfeeding such as the prevention of infections, the effect of breastfeeding on neurodevelopmental outcome, obesity, allergy and celiac disease. Available evidence as well as some of the contradictory results is discussed.

© 2016 Nestec Ltd., Vevey/S. Karger AG, Basel.

Publication types

- Breast Feeding*

- Celiac Disease / prevention & control

- Communicable Diseases / diet therapy

- Health Promotion

- Hypersensitivity / prevention & control

- Infant Nutritional Physiological Phenomena

- Meta-Analysis as Topic

- Milk, Human / chemistry*

- Neurodevelopmental Disorders / prevention & control

- Obesity / prevention & control

- Observational Studies as Topic

- Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 19 May 2024

The role of breastfeeding and formula feeding regarding depressive symptoms and an impaired mother child bonding

- Clara Carvalho Hilje 1 , 2 ,

- Nicola H. Bauer 3 ,

- Daniela Reis 1 , 2 ,

- Claudia Kapp 4 ,

- Thomas Ostermann 4 ,

- Franziska Vöhler 5 &

- Alfred Längler 1 , 2

Scientific Reports volume 14 , Article number: 11417 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

407 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Paediatrics

Associations between depressive symptoms and breastfeeding are well documented. However, evidence is lacking for subdivisions of feeding styles, namely exclusive breastfeeding, exclusive formula feeding and a mixed feeding style (breastfeeding and formula feeding). In addition, studies examining associations between mother-child-bonding and breastfeeding have yielded mixed results. The aim of this study is to provide a more profound understanding of the different feeding styles and their associations with maternal mental health and mother-child-bonding. Data from 307 women were collected longitudinally in person (prenatally) and by telephone (3 months postnatally) using validated self-report measures, and analyzed using correlational analyses, unpaired group comparisons and regression analyses. Our results from a multinomial regression analysis revealed that impaired mother-child-bonding was positively associated with mixed feeding style ( p = .003) and depressive symptoms prenatal were positively associated with exclusive formula feeding ( p = .013). Further studies could investigate whether information about the underlying reasons we found for mixed feeding, such as insufficient weight gain of the child or the feeling that the child is unsatiated, could help prevent impaired mother-child-bonding. Overall, the results of this study have promising new implications for research and practice, regarding at-risk populations and implications for preventive measures regarding postpartum depression and an impaired mother-child-bonding.

Similar content being viewed by others

Exclusive breastfeeding promotion policies: whose oxygen mask are we prioritizing?

Association between maternal postpartum depressive symptoms, socioeconomic factors, and birth outcomes with infant growth in South Africa

A randomised controlled trial evaluating the effect of a brief motivational intervention to promote breastfeeding in postpartum depression

Introduction.

Pregnancy and the birth of a child is an extraordinary and overwhelming event for many women. It is accompanied by intense positive emotions 1 , 2 . However, the birth of a child is associated with several changes and can cause intense stress 2 , 3 . Peri- and postpartum depression is defined as an episode of major depression that is associated with childbirth 4 . With a prevalence ranging from 10 to 15%—or even higher in lower- and middle-income countries—postpartum depression (PPD) is a widespread illness 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 . Its effects on maternal and the infant’s health, is a well-recognized issue 9 . Several studies have examined developmental disturbances in children of (severely) depressed mothers 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , such as behavioral problems, lower math scores, or a sevenfold risk of depression during adolescence 16 . PPD is furthermore associated with an impaired mother-child-bonding 14 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , which poses an increased risk of impaired emotional, social and cognitive development in the child 25 , 26 . Mother-child-bonding is described as a general tendency in the first weeks and months after birth to engage in social interaction with each other 27 . It is conceived as the maternal bond towards the child and the child's attachment towards the mother 28 . Disruption of this process has a long history in research 29 and has been described as a disorder of mother-child - bonding 19 , 30 . The mother’s emotional response to the child is considered an essential symptom of bonding disorder and may reach the level of hatred and rage 29 . Mother-child-bonding disorders include a lack of maternal emotion to the extent that it can cause distress, irritability, hostile and aggressive impulses, pathological ideas, and outright rejection of the child 19 . Numerous further studies provide evidence for an association between PPD and mother–child bonding disorders 14 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 24 , 31 .

A possibility to prevent adverse outcomes such as PPD and an impaired mother-child-bonding might be breastfeeding . Previous studies found supportive evidence that (exclusive) breastfeeding prevents PPD and a poor mother-child-bonding 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 and vice versa, as PPD is associated with early cessation of breastfeeding 42 , 43 , 44 . Numerous other studies provide evidence of an association between weaning and maternal depression 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 . In addition, 60% to 90% of women indicate breastfeeding difficulties, which may be an additional source of stress 51 , 52 . This can lead to a vicious cycle, as breastfeeding difficulties are an additional stressor for the mother and may promote depression 53 , 54 , 55 .

Studies examining associations between mother-child-bonding and breastfeeding, as well as attachment—which focuses more on how the infant builds up a relationship with its primary caregiver 56 —and breastfeeding, have found mixed results 37 , 38 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 . Keller et al. (2016) found that the Postpartum Bonding Questionnaire (PBQ) factor “anxiety about care” negatively predicted breastfeeding duration beyond six months 62 . Besides the educational level of the mothers, this was found to be the most important influential factor on the duration of breastfeeding in a regression analysis. Systematic reviews of the associations between breastfeeding and mother-child-bonding found that maternal sensitivity and secure attachment were the aspects of mother-child-bonding most often associated with breastfeeding 63 , 64 . Regarding the associations between breastfeeding difficulties and mother-child-bonding, emotional availability was found to be negatively correlated with objective (e.g. cracked nipples) as well as subjective breastfeeding difficulties (e.g. perceived insufficiency of milk supply 65 ). In another study, secure attachment also appears to play an important role in breastfeeding continuation when breastfeeding difficulties occur 66 . In addition, breastfeeding confidence was found to be positively associated with higher levels of maternal attachment 67 . A study by Smith and Ellwood (2011) reported a descending pattern from exclusive to mixed to no breastfeeding and receipt of emotional care from the mother. The authors suggest that the time invested in breastfeeding and the associated close contact between mother and child strengthens the bond between the two. More time may also improve breastfeeding itself 68 . However, to our knowledge, no study so far differentiated exclusive, mixed and no breastfeeding patterns with regard to mother-child-bonding in particular.

Further research on the association of breastfeeding on PPD and mother-child-bonding may contribute in a meaningful way to the prevention of subsequent disorders and the reduction of long-term consequences for mother and child. The aforementioned influence of mother-child-bonding on breastfeeding behavior led us to include bonding as an independent variable in the study. The study design explained below led us to examine the influence of depressive symptoms in pregnant women and the influence of depressive symptoms in postpartum mothers, also as independent variables, in relation to the different feeding practices. The aim of this study is to examine whether PPD and poor mother-child-bonding are associated with different feeding practices (exclusive, mixed and no breastfeeding) in order to gain a better understanding of the associations between feeding practices and adverse psychological outcomes, such as PPD. In addition, to better understand such associations, we investigated the reasons for non-breastfeeding or adding formula in our study. We hypothesized that mothers who breastfed (exclusively) at the time point of three months postpartum would show significantly less symptoms of PPD and would report a better bonding towards their child, than mothers who did not breastfeed at that time.

Study design and procedure

The present work was embedded in a larger research project “Baby-Friendly and Breastfeeding” (in the following BaSti-study ) and is a longitudinal observational cohort design. We recruited women between December 2017 and November 2019 vis-a-a-vis prenatal (participants were at least in their 16th week of pregnancy) as well as postpartum (three months after birth) via phone after the participants gave their informed consent. Recruitment took place before and after midwife consultations and gynecological examinations, delivery room information evenings and, for only postpartum surveys, through the hospital staff at the neonatal wards. Four pilot surveys were conducted prior to actual implementation. The participating hospitals were two university teaching hospitals in Germany. Inclusion criteria were delivery in one of the participating hospitals, a minimum age of 18 years and sufficient German language skills. Stillbirths or early postnatal death led to an exclusion of the study. The final study sample comprised N = 307. Of the total sample, 90 women (29.3%) were surveyed during pregnancy. To ensure that the conditions of the surveys were as comparable as possible, the procedure was always as follows: participants received (1) an information sheet, (2) the consent form, (3) a questionnaire on sociodemographic data and the test battery. Prior to the introduction of the EPDS, the following standardized introduction was presented to the participants by the person conducting the survey: " I would like to move on to topics that may be uncomfortable for you. If you do not wish to answer a question, you are of course free to do so. It is important for me to emphasize at this point that negative thoughts and feelings about yourself and the child can be common during and after pregnancy and are, to a certain extent, quite normal. However, it is possible for these feelings to persist for several days or weeks, leading to what is known as PPD. It is important to us that this topic receives more attention and recognition in the future and is not made taboo, as this leaves those affected alone with it". We filled in the answers given in the postpartum telephone survey in the questionnaire and sent it to the participants upon request.

All research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines. The participants proved written informed consent to participate in the study. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Ethics Committee of the University Witten/Herdecke approved all components of the project 86/2017.

Instruments

Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (epds).

To assess the occurrence of depressive symptoms we used the German version 69 of the 10-item self-report scale EPDS 70 as a screening tool. The EPDS was originally developed as a screening instrument for the postnatal period 71 , but because it has been validated in numerous studies as an applicable tool for both pre- and postpartum assessment 72 , we included it in both settings. Each item is scored on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 to 3—with a higher sum score indicating more depressive symptoms 20 , 69 . Responses are based on the mental state over the past seven days 69 . The data revealed a Cronbach’s α of 0.82 (prepartum) and 0.79 (postpartum) in our sample.

Postpartum Bonding Questionnaire (PBQ)

To investigate mother–infant bonding, we used the German version of the self-report PBQ 19 , 23 , which assesses a mother’s feelings or behaviors toward her infant 73 . In contrast to the original version, which consists of 25 items and proposes a four factor solution, the German version of the screening instrument consists of 16 Items and proposes a solution with only one general factor “impaired bonding” 23 . The Likert scaling of the PBQ ranges from 0 (always) to 5 (never), with a higher sum score indicating impaired bonding 20 . In our sample, the internal consistency was α = 0.80.

Questionnaire “Feeling Comfortable During Pregnancy” (original: Schwanger Wohlfühlen)

To assess possible covariates such as subjective mental and physical well-being, coping during pregnancy and partner relationship/social support, we administered the questionnaire “Feeling Comfortable During Pregnancy” 74 during pregnancy. The questionnaire was originally developed in German and consists of 38 items. They reflect the dimensions “ affective well-being ”, “ physical well-being ” and “ coping during pregnancy ”. Responses are given on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (does not apply at all) to 7 (fully applicable). In our sample, the overall internal consistency reached Cronbach’s α = 0.82 and for the three underlying dimensions affective well-being α = 0.82, physical well-being α = 0.42 and coping during pregnancy α = 0.66.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 27.0 (IBM Corp 2020). Decisions regarding the use of parametric or non-parametric tests are, besides the scale levels of the variables, based on the examination of outliers and the following assumptions: additivity and linearity, homoscedasticity, independence of residual terms and multicollinearity 75 . We tested normality with regard to sample sizes ˂ 30 75 , 76 . To use either parametric or non-parametric tests was decided for each test individually.

Hypothesis testing was conducted in two steps. First, unpaired group comparisons and correlational analyses were performed. All significant interactions with more than two groups were analyzed with post hoc tests. Due to different sample sizes, we chose to use Hochberg’s GT2 as a post hoc test 75 . Second, logistic regression analyses containing the significant results out of step one were performed. Because the regression analyses were hierarchical 75 , we focused primarily on the Akaike information criterion (AIC) to decide on a model. The final model of the regression analyses was bootstrapped ( N = 1000 samples, 95% confidence interval), to ensure its explanatory value.

Potential covariates

Given previous research on the EPDS postpartum, the PBQ and the success of breastfeeding 20 , 23 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 , 81 , we included the following covariates (see Table 1 ) to minimize potential confounding.

Descriptive statistics

Women were aged between 19 and 57 years ( M = 32.93, SD = 4.50) and 87.6% of the women were born in Germany. 10.1% of the women have previously had a psychological illness. 12.7% of the children had to be transferred to the pediatric clinic after birth. See Table 2 for additional demographic characteristics.

Feeding styles and its associations with PPD and mother–child-bonding

A t -test did not reveal significant differences between the breastfeeding (n = 263) and the non-breastfeeding group (n = 43) concerning the postpartum EPDS, t (304) = 1.695, p = 0.09. Due to an outlier we found, we additionally performed a Mann–Whitney U -Test, which confirmed our results, U (43,263) = 4647.00, Z = −1.881, p = 0.060. However, a tendency was evident here. No significant difference could be shown with respect to PBQ scores either, t (304) = −1.320, p = 0.188.

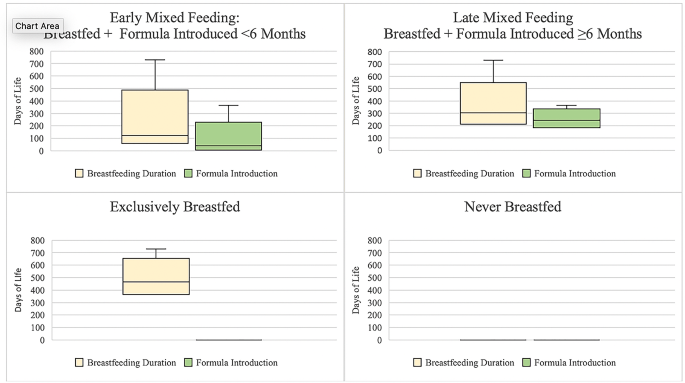

Examining exclusive breastfeeding vs. mixed feeding vs. non-breastfeeding, an ANOVA revealed significant differences in EPDS scores postpartum, F (2, 304) = 3.323, p = 0.037, r = 0.145, with a small effect size 82 , as well as in PBQ scores, F (2, 304) = 4.689, p = 0.010, r = 0.173. For EPDS scores, post hoc tests did not reveal significant differences between the groups. For PBQ scores, post hoc tests showed significant differences between the breastfeeding group and the mixed feeding group, M Diff = −2.801, 95% CI [− 5.24, − 0.37], p = 0.018, with d = 0.551, indicating a medium effect size 82 , as well as between the non-breastfeeding group and the mixed feeding group, M Diff = − 3.610, 95% CI [− 6.57, − 0.65], p = 0.011, with d = 0.677, also indicating a medium effect size 82 .

Based on these findings, we conducted multinomial regression analyses. Table 3 shows all correlations of potential variables relevant to exclusive breastfeeding. Significant correlations were included in the regression analyses. In order to obtain a feasibly parsimonious model, we decided to use a hierarchical method 75 .

Our final regression model (Table 4 ) included the PBQ score and EPDS score prenatal as significant variables relevant to the different breastfeeding states (AIC = 148.514). The Likelihood Ratio test was significant, χ 2 (4, N = 86) = 17.647, p ˂ 0.001, and Nagelkerke’s R 2 = 0.221 (Cox and Snell’s R 2 = 0.184) can be considered as acceptable 83 . Both, Pearson test ( p = 0.554) and deviance ( p = 0.954), indicated that the model was a good fit to the data 75 . Bootstrapped regression weights (Table 5 ) confirm our results.

We furthermore investigated partner relationship/social support for breastfeeding and reasons for non-breastfeeding or adding formula as well as associations with breastfeeding difficulties . Regarding partner relationship/social support, no significant difference was found between the groups, χ 2 (2, N = 200) = 3.293, p = 0.193. Table 6 shows the reasons given by the groups. Mothers who added formula reported more often than mothers who did not breastfeed, that they were unsure whether the infant was satiated/were sure that they were not satiated, and that the infant did not gain enough weight. In terms of any breastfeeding difficulties, correlations with the EPDS postpartum, η = 0.033, p = 0.568, and the PBQ, η = 0.077, p = 0.181, were both not significant. Regarding the quantity of breastfeeding difficulties no significant correlation was found with the EPDS postpartum, r (307) = 0.058, p = 0.311, 95% CI [− 0.054, 0.169], nor with the PBQ, r (307) = 0.080, p = 0.160, 95% CI [− 0.032, 0.191], either.

The aim of this study was to investigate associations between depressive symptoms, mother–child-bonding and different feeding practices (exclusive, mixed, and no breastfeeding). We found that higher EPDS scores prepartum were associated with non-breastfeeding rather than with exclusive breastfeeding three months after birth. The association with the postpartum EPDS score was less clear. Nevertheless, an association between depressive symptoms occurring around pregnancy and birth and non-breastfeeding at three months after delivery was, as hypothesized, definitely reflected in our results and supports previous studies which found similar relations 36 , 40 , 46 , 47 , 48 . Another study that focused on the factor of a "breastfeeding method" found that exclusive or non-exclusive breastfeeding did not significantly affect depression, anxiety, or mother–child-bonding in the early postpartum period nor vice versa 84 . However the authors attributed these results to the short observation period of one month after birth, among other factors.

Considerations that PPD could be triggered by breastfeeding difficulties 54 , 55 as a common source of stress 51 , 52 , are not supported by our results. According to Roth et al. (2021) breastfeeding difficulties are associated with lower bonding while postpartum depression has a negative impact on bonding quality regardless of breastfeeding difficulties: “The effect of breastfeeding difficulties on bonding persists over and above the effect of postnatal depressive symptoms” 85 . The authors concluded that postpartum depression and breastfeeding difficulties provide unique pathways for understanding bonding. A better understanding of bonding is relevant because studies have confirmed its importance, especially the importance of maternal sensitivity, for child development 86 . Furthermore, we found that with a higher PBQ score, mothers were signficantly more likely to report adding formula at the time point of three months than to exclusively breastfeed. To our knowledge, no study so far differentiated exclusive, mixed and formula feeding patterns with regard to mother-child-bonding in particular. Higher oxytocin levels may be of explanatory value for differences between exclusive and mixed breastfeeding. The quality of mother–child interrelations and maternal oxytocin levels appear to be positively correlated 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 . Oxytocin has also been found to be lower in patients with major depression 91 and with higher depression symptoms postpartum 47 , 92 .

However, following the argument of oxytocin levels and breastfeeding, it remains unclear why mothers who had not breastfed also reported a better bonding quality than mothers who practiced mixed feeding, which is different from our hypothesis. Mothers who added formula reported reasons such as insufficient weight gain and non-satiation of the infant for doing so significantly more often than mothers who did not breastfed. Clayton et al. (2013) already found that infant hunger was a predominant reason for mixed feeding, rather than bottle-feeding alone 93 . In addition, no mother who added formula cited self-referred reasons, such as convenience, less dependency, stress or simply “not feeling like it” for their decision, whereas mothers who did not breastfeed did report such reasons. These results indicate that the underlying impulses and prior experiences that lead to the decision whether to add formula or to wean differ. First, women who decide to wean seem to be more likely to make decisions in their own favor, as the postpartum period has negative effects on their quality of life 94 . Second, these women may have more self-confidence to face potential stigmas associated with the role of the mother and (discontinued) breastfeeding. Hence, they may be able to see their bond with their child as unaffected by less successful breastfeeding. The relationship between self-confidence, self-care and bonding has been well investigated 95 , 96 , 97 and may be of important explanatory value for our findings. Third, thinking that the child is not gaining enough weight or might be hungry could lead to feelings of guilt and cause stress. Postpartum stress decreases maternal self-confidence and affects the relationship between mother and child 98 . The decision to wean might be a relief for some women and reduce one source of postpartum stress. Symon et al. (2013) furthermore found the antenatal breastfeeding intention to be an important factor regarding satisfaction 99 . Maternal satisfaction scores were highest, when breastfeeding goals were reached, regardless of whether the goal was to breastfeed or intentionally not to do so 99 . Subsequently, regarding the given reasons to add formula, a possible explanation for higher PBQ scores of mixed feeding mothers in our sample could be, that they did not reach their breastfeeding goal, which subsequently resulted in a poorer rating of the bonding to their infant. However, more research is needed to prove our findings and conclusions, as the breastfeeding patterns, as distributed by us, and their association to mother–child-bonding, are to our knowledge still unexplored.

Our findings can be highly beneficial in terms of designing and disassembling preventive programs. They support for example indications to provide universal screening of previous depressive symptoms during pregnancy. It should be noted that screening in itself does not mean that depression can be definitively identified in an individual. Screening aims to identify as accurately as possible subpopulations with a high prevalence. A full diagnostic evaluation can only be made based on gold-standard clinical criteria 100 . Furthermore, peripartum maternal mental health is complex, as it comprises a variety of possible mental health problems 1 .

Screening should also be conducted postpartum, comprehensively, and with a special focus on at-risk populations. Especially reasons and impacts concerning a mixed feeding-style should be addressed in future research, to enable drawing more profound conclusions. Breastfeeding mothers with infants that do not gain enough weight or are not being sufficiently satiated, should especially be supported postpartum, as they tend to characterize their bonding as poorer, respectively. Education over these problems and possible solutions for them should get more attention during hospitalization and antepartum. According to our findings, mother–child-bonding seems to be an important variable in the issue of different feeding practices (exclusive, mixed, and non-breastfeeding). Depressive symptoms prepartum also seem to be an important variable in this context. We have not investigated to what extent the two are related. Although breastfeeding has many benefits for both the mother and the infant, the relationship between maternal mental health and breastfeeding is complex. It should be taken into consideration that breastfeeding may not be the most effective or viable option for all mothers 101 .

Limitations

Several points limiting our findings should be considered. Although we included several possible covariates in our analyses, confounding factors might remain. We also did not impute the missing values (this refers especially to the prepartum data). When recruiting participants for the study, we were aware that this was a sensitive issue and that we did not want to commit to the sample size initially. We did not perform a power analysis prior to recruitment. Besides that, we did not evaluate our data with respect to dropouts. Hence, we cannot completely rule out an attrition bias. Future studies should collect data concerning information over their dropouts, as previous studies already reported for example higher depression rates in groups with missing data 16 . However, inclusion in our study was not very restrictive and data collection took place in different in-hospital environments. This led to a large sample that is representative of the facilities in which they were collected. The reliability of the subscales physical well-being and coping during pregnancy of the Questionnaire "Feeling Comfortable During Pregnancy" was lower than expected and not significant in the correlations (Table 3 ) and thus excluded from the regression analyses, which needs to be addressed here. Even though all screening tools used in our study were established and validated, it should be noted that we exclusively used self-report measures. These can cause biases, for example through answering in a socially desirable manner 102 , 103 , 104 , which could be crucial for our findings regarding associations between poor bonding and high education 23 , 81 . Reck et al. (2006) reported similar findings and hypothesized that higher educated mothers would have a greater tendency to answer in a less socially desirable manner, rather than actually suffering from poorer bonding to their infants 23 . Mixed-measure designs could prevent such biases. Future studies should for example consider including structured diagnostic interviews, video observations of maternal behavior or biochemical analyses. Depressed women furthermore tend to rate themselves as worse parents than they are, due to a low self-esteem and negative thoughts 105 , 106 , which could have affected some of the associations we found.

Our findings provide important implications for future directions. These concern information regarding populations that may be at higher risk of developing PPD or a poor mother-child-bonding, such as antenatal depressive symptoms, or, representing to our knowledge a new finding, a mixed feeding style. However, more research is needed to get a more profound understanding of associations between mother–child-bonding and a mixed feeding style. Especially information about underlying reasons we found for performing mixed feeding, such as insufficient weight gain of the child or the feeling that the child was unsatiated, could contribute in a meaningful way to prevent impaired mother–child-bonding. We suggest implementing more measures supporting aspects such as self-efficacy and postpartum well-being of the mother in preventive programs.

Data availability

Due to the strict European General Data Protection Regulation the dataset generated in this study can not be deposited in a public repository. A request for access to the pseudonymized data for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data must be submitted to the author: Clara Carvalho Hilje, email: [email protected].

Jomeen, J. in Mayes’ Midwifery , edited by S. Macdonald & G. Johnson (Elsevier, 2017), Vol. 15 186–199.

Razurel, C., Bruchon-Schweitzer, M., Dupanloup, A., Irion, O. & Epiney, M. Stressful events, social support and coping strategies of primiparous women during the postpartum period: a qualitative study. Midwifery 27 , 237–242 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Razurel, C., Kaiser, B., Sellenet, C. & Epiney, M. Relation between perceived stress, social support, and coping strategies and maternal well-being: A review of the literature. Women Health 53 , 74–99 (2013).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-5 , 5th ed (American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013).

Dorn, A. & Mautner, C. Postpartale depression. Interdisziplinäre Behandlung. Die Gynäkologie 51 , 94–101 (2018).

Article Google Scholar

Gaynes B. N. et al. in AHRQ Evidence Report Summaries , edited by B. N. Gaynes, et al. (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), 2005).

Howard, L. M. et al. Non-psychotic mental disorders in the perinatal period. Lancet 384 , 1775–1788 (2014).

Munk-Olsen, T., Laursen, T. M., Pedersen, C. B., Mors, O. & Mortensen, P. B. New parents and mental disorders: A population-based register study. JAMA 296 , 2582–2589 (2006).

Grigoriadis, S. et al. The impact of maternal depression during pregnancy on perinatal outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychiatry 74 , e321–e341 (2013).

DiPietro, J. A., Novak, M. F. S. X., Costigan, K. A., Atella, L. D. & Reusing, S. P. Maternal psychological distress during pregnancy in relation to child development at age two. Child Dev. 77 , 573–587 (2006).

Field, T. Prenatal depression risk factors, developmental effects and interventions: A review. J. Pregnancy Child Health 4 , 66 (2017).

Google Scholar

Gelaye, B., Rondon, M. B., Araya, R. & Williams, M. A. Epidemiology of maternal depression, risk factors, and child outcomes in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Psychiatry 3 , 973–982 (2016).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kim-Cohen, J., Caspi, A., Rutter, M., Tomás, M. P. & Moffitt, T. E. The caregiving environments provided to children by depressed mothers with or without an antisocial history. Am. J. Psychiatry 163 , 1009–1018 (2006).

Moehler, E., Brunner, R., Wiebel, A., Reck, C. & Resch, F. Maternal depressive symptoms in the postnatal period are associated with long-term impairment of mother–child bonding. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 9 , 273–278 (2006).

Murray, L., Halligan, S. L., Goodyer, I. & Herbert, J. Disturbances in early parenting of depressed mothers and cortisol secretion in offspring: A preliminary study. J. Aff. Disord. 122 , 218–223 (2010).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Netsi, E. et al. Association of persistent and severe postnatal depression with child outcomes. JAMA Psychiatry 75 , 247–253 (2018).

Öztop, D. & Uslu, R. Behavioral, interactional and developmental symptomatology in toddlers of depressed mothers: A preliminary clinical study within the DC:0–3 framework. Turk. J. Pediatr. 49 , 171–178 (2007).

PubMed Google Scholar

Behrendt, H. F. et al. Postnatal mother-to-infant attachment in subclinically depressed mothers: Dyads at risk?. Psychopathology 49 , 269–276 (2016).

Brockington, I. F. et al. A screening questionnaire for mother–infant bonding disorders. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 3 , 133–140 (2001).

Dubber, S., Reck, C., Müller, M. & Gawlik, S. Postpartum bonding: The role of perinatal depression, anxiety and maternal-fetal bonding during pregnancy. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 18 , 187–195 (2015).

Friedman, S. H. & Resnick, P. J. Postpartum depression: An update. Women’s Health 5 , 287–295 (2009).

Nonnenmacher, N., Noe, D., Ehrenthal, J. C. & Reck, C. Postpartum bonding: The impact of maternal depression and adult attachment style. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 19 , 927–935 (2016).

Reck, C. et al. The German version of the postpartum bonding instrument: Psychometric properties and association with postpartum depression. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 9 , 265–271 (2006).

Song, M. et al. Maternal depression and mother-to-infant bonding: The association of delivery mode, general health and stress markers. OJOG 07 , 155–166 (2017).

Fitzsimons, E. & Vera-Hernández, M. Breastfeeding and child development. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 14 , 329–366 (2022).

Smith-Nielsen, J., Tharner, A., Krogh, M. T. & Vaever, M. S. Effects of maternal postpartum depression in a well-resourced sample: Early concurrent and long-term effects on infant cognitive, language, and motor development. Scand. J. Psychol. 57 , 571–583 (2016).

Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss (Basic Books, 1980).