- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Frederick Douglass

By: History.com Editors

Updated: March 8, 2024 | Original: October 27, 2009

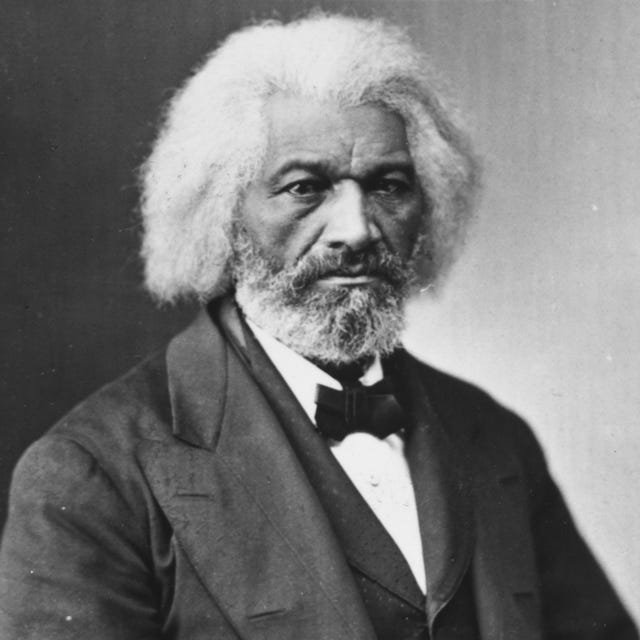

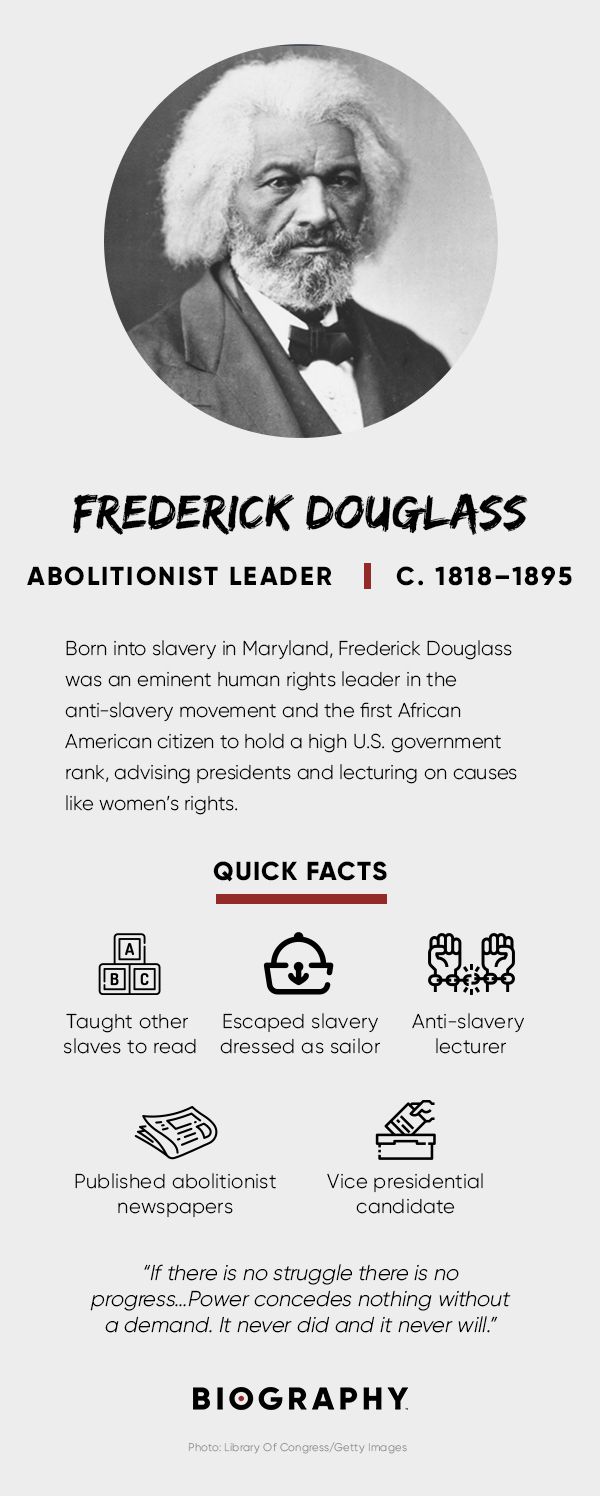

Frederick Douglass was a formerly enslaved man who became a prominent activist, author and public speaker. He became a leader in the abolitionist movement , which sought to end the practice of slavery, before and during the Civil War . After that conflict and the Emancipation Proclamation of 1862, he continued to push for equality and human rights until his death in 1895.

Douglass’ 1845 autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave , described his time as an enslaved worker in Maryland . It was one of three autobiographies he penned, along with dozens of noteworthy speeches, despite receiving minimal formal education.

An advocate for women’s rights, and specifically the right of women to vote , Douglass’ legacy as an author and leader lives on. His work served as an inspiration to the civil rights movement of the 1960s and beyond.

Who Was Frederick Douglass?

Frederick Douglass was born into slavery in or around 1818 in Talbot County, Maryland. Douglass himself was never sure of his exact birth date.

His mother was an enslaved Black women and his father was white and of European descent. He was actually born Frederick Bailey (his mother’s name), and took the name Douglass only after he escaped. His full name at birth was “Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey.”

After he was separated from his mother as an infant, Douglass lived for a time with his maternal grandmother, Betty Bailey. However, at the age of six, he was moved away from her to live and work on the Wye House plantation in Maryland.

From there, Douglass was “given” to Lucretia Auld, whose husband, Thomas, sent him to work with his brother Hugh in Baltimore. Douglass credits Hugh’s wife Sophia with first teaching him the alphabet. With that foundation, Douglass then taught himself to read and write. By the time he was hired out to work under William Freeland, he was teaching other enslaved people to read using the Bible .

As word spread of his efforts to educate fellow enslaved people, Thomas Auld took him back and transferred him to Edward Covey, a farmer who was known for his brutal treatment of the enslaved people in his charge. Roughly 16 at this time, Douglass was regularly whipped by Covey.

Frederick Douglass Escapes from Slavery

After several failed attempts at escape, Douglass finally left Covey’s farm in 1838, first boarding a train to Havre de Grace, Maryland. From there he traveled through Delaware , another slave state, before arriving in New York and the safe house of abolitionist David Ruggles.

Once settled in New York, he sent for Anna Murray, a free Black woman from Baltimore he met while in captivity with the Aulds. She joined him, and the two were married in September 1838. They had five children together.

From Slavery to Abolitionist Leader

After their marriage, the young couple moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts , where they met Nathan and Mary Johnson, a married couple who were born “free persons of color.” It was the Johnsons who inspired the couple to take the surname Douglass, after the character in the Sir Walter Scott poem, “The Lady of the Lake.”

In New Bedford, Douglass began attending meetings of the abolitionist movement . During these meetings, he was exposed to the writings of abolitionist and journalist William Lloyd Garrison.

The two men eventually met when both were asked to speak at an abolitionist meeting, during which Douglass shared his story of slavery and escape. It was Garrison who encouraged Douglass to become a speaker and leader in the abolitionist movement.

By 1843, Douglass had become part of the American Anti-Slavery Society’s “Hundred Conventions” project, a six-month tour through the United States. Douglass was physically assaulted several times during the tour by those opposed to the abolitionist movement.

In one particularly brutal attack, in Pendleton, Indiana , Douglass’ hand was broken. The injuries never fully healed, and he never regained full use of his hand.

In 1858, radical abolitionist John Brown stayed with Frederick Douglass in Rochester, New York, as he planned his raid on the U.S. military arsenal at Harper’s Ferry , part of his attempt to establish a stronghold of formerly enslaved people in the mountains of Maryland and Virginia. Brown was caught and hanged for masterminding the attack, offering the following prophetic words as his final statement: “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood.”

'Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass'

Two years later, Douglass published the first and most famous of his autobiographies, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave . (He also authored My Bondage and My Freedom and Life and Times of Frederick Douglass).

In it Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass , he wrote: “From my earliest recollection, I date the entertainment of a deep conviction that slavery would not always be able to hold me within its foul embrace; and in the darkest hours of my career in slavery, this living word of faith and spirit of hope departed not from me, but remained like ministering angels to cheer me through the gloom.”

He also noted, “Thus is slavery the enemy of both the slave and the slaveholder.”

Frederick Douglass in Ireland and Great Britain

Later that same year, Douglass would travel to Ireland and Great Britain. At the time, the former country was just entering the early stages of the Irish Potato Famine , or the Great Hunger.

While overseas, he was impressed by the relative freedom he had as a man of color, compared to what he had experienced in the United States. During his time in Ireland, he met the Irish nationalist Daniel O’Connell , who became an inspiration for his later work.

In England, Douglass also delivered what would later be viewed as one of his most famous speeches, the so-called “London Reception Speech.”

In the speech, he said, “What is to be thought of a nation boasting of its liberty, boasting of its humanity, boasting of its Christianity , boasting of its love of justice and purity, and yet having within its own borders three millions of persons denied by law the right of marriage?… I need not lift up the veil by giving you any experience of my own. Every one that can put two ideas together, must see the most fearful results from such a state of things…”

Frederick Douglass’ Abolitionist Paper

When he returned to the United States in 1847, Douglass began publishing his own abolitionist newsletter, the North Star . He also became involved in the movement for women’s rights .

He was the only African American to attend the Seneca Falls Convention , a gathering of women’s rights activists in New York, in 1848.

He spoke forcefully during the meeting and said, “In this denial of the right to participate in government, not merely the degradation of woman and the perpetuation of a great injustice happens, but the maiming and repudiation of one-half of the moral and intellectual power of the government of the world.”

He later included coverage of women’s rights issues in the pages of the North Star . The newsletter’s name was changed to Frederick Douglass’ Paper in 1851, and was published until 1860, just before the start of the Civil War .

Frederick Douglass Quotes

In 1852, he delivered another of his more famous speeches, one that later came to be called “What to a slave is the 4th of July?”

In one section of the speech, Douglass noted, “What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer: a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciations of tyrants, brass fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade, and solemnity, are, to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy—a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages.”

For the 24th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation , in 1886, Douglass delivered a rousing address in Washington, D.C., during which he said, “where justice is denied, where poverty is enforced, where ignorance prevails, and where any one class is made to feel that society is an organized conspiracy to oppress, rob and degrade them, neither persons nor property will be safe.”

Frederick Douglass During the Civil War

During the brutal conflict that divided the still-young United States, Douglass continued to speak and worked tirelessly for the end of slavery and the right of newly freed Black Americans to vote.

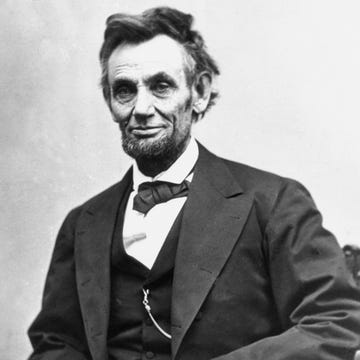

Although he supported President Abraham Lincoln in the early years of the Civil War, Douglass fell into disagreement with the politician after the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, which effectively ended the practice of slavery. Douglass was disappointed that Lincoln didn’t use the proclamation to grant formerly enslaved people the right to vote, particularly after they had fought bravely alongside soldiers for the Union army.

It is said, though, that Douglass and Lincoln later reconciled and, following Lincoln’s assassination in 1865, and the passage of the 13th amendment , 14th amendment , and 15th amendment to the U.S. Constitution (which, respectively, outlawed slavery, granted formerly enslaved people citizenship and equal protection under the law, and protected all citizens from racial discrimination in voting), Douglass was asked to speak at the dedication of the Emancipation Memorial in Washington, D.C.’s Lincoln Park in 1876.

Historians, in fact, suggest that Lincoln’s widow, Mary Todd Lincoln , bequeathed the late-president’s favorite walking stick to Douglass after that speech.

In the post-war Reconstruction era, Douglass served in many official positions in government, including as an ambassador to the Dominican Republic, thereby becoming the first Black man to hold high office. He also continued speaking and advocating for African American and women’s rights.

In the 1868 presidential election, he supported the candidacy of former Union general Ulysses S. Grant , who promised to take a hard line against white supremacist-led insurgencies in the post-war South. Grant notably also oversaw passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1871 , which was designed to suppress the growing Ku Klux Klan movement.

Frederick Douglass: Later Life and Death

In 1877, Douglass met with Thomas Auld , the man who once “owned” him, and the two reportedly reconciled.

Douglass’ wife Anna died in 1882, and he married white activist Helen Pitts in 1884.

In 1888, he became the first African American to receive a vote for President of the United States, during the Republican National Convention. Ultimately, though, Benjamin Harrison received the party nomination.

Douglass remained an active speaker, writer and activist until his death in 1895. He died after suffering a heart attack at home after arriving back from a meeting of the National Council of Women , a women’s rights group still in its infancy at the time, in Washington, D.C.

His life’s work still serves as an inspiration to those who seek equality and a more just society.

HISTORY Vault: Black History

Watch acclaimed Black History documentaries on HISTORY Vault.

Frederick Douglas, PBS.org . Frederick Douglas, National Parks Service, nps.gov . Frederick Douglas, 1818-1895, Documenting the South, University of North Carolina , docsouth.unc.edu . Frederick Douglass Quotes, brainyquote.com . “Reception Speech. At Finsbury Chapel, Moorfields, England, May 12, 1846.” USF.edu . “What to the slave is the 4th of July?” TeachingAmericanHistory.org . Graham, D.A. (2017). “Donald Trump’s Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass.” The Atlantic .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass

By frederick douglass.

- Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass Summary

The Narrative begins with Douglass explaining that he was born in Talbot County, Maryland, but did not know his birthday because such information was often kept from slaves, which was lamentable and bothersome to him throughout his life. He rarely saw his mother and the identity of his father was unknown, although it was commonly assumed to be his first master, Captain Anthony . Anthony was a moderately wealthy slaveholder and was not particularly kind or conscientiousness. He rarely interfered when his overseers treated his slaves brutally.

Anthony was the clerk and superintendent for Colonel Lloyd , one of Maryland's wealthiest slaveholders. His plantation home was known as the Great House Farm, where Douglass resided when he was very young. Slaves received scanty allowances and had little time of their own; many were also cruelly beaten by the overseers. However, slaves on the outlying farm spoke highly of Great House Farm and considered it an honor to be sent there on errands.

Douglass detailed the sumptuous gardens of Colonel Lloyd's plantation and provided further information about the realities of slavery. He explained why slaves often praised their masters: they were afraid that the whites to whom they were speaking would report their insolence and they would be punished. Douglass also wrote of the wild and mournful beauty of the slave songs and how they suggested the horrors of slavery.

Douglass did not have many tasks on Colonel Lloyd's plantation. He was often cold and hungry. Thankfully, it was announced one day that he amongst several slave children was chosen to live with Anthony's son-in-law's brother, Hugh Auld , in Baltimore. Douglass attributed this fortuitous event to divine intervention; he knew God meant for him to one day escape the bonds of servitude.

Douglass's new mistress, Mrs. Auld , was sweet and untouched by the destructive effects of slavery. She refused to treat him ill and even decided she would teach him how to read. Her husband, however, knowing the effects of teaching a slave to read – intractability, unmanageability, disillusionment – forbade her from doing so. Douglass decided he would teach himself how to read and write; this he did by learning from the Baltimore street boys and using the Aulds' son's copybooks to practice writing. Douglass attained a copy of the Columbian Orator , which provided him with writings on emancipation and a denunciation of slavery.

After Captain Anthony died his assets, including all of the salves, were divided amongst two of his children. Thankfully Douglass was able to remain with Master Hugh, but this was short-lived: a quarrel between Hugh and his brother, Thomas, resulted in Douglass being sent to live with Thomas instead. He was not sad to go, as drink and the realities of slavery had ruined Mr. and Mrs. Hugh Auld, respectively, but living with Master Thomas was not pleasant either. Thomas was ignoble, cowardly, cruel, and virulently hypocritical in his faith. He and Douglass did not have a good relationship, and the latter was sent to work on the farm of Edward Covey , the famed "slave-breaker" known for "taming" slaves.

Living with Covey was the low point of Douglass's life. He was beaten frequently in the most unjust manner conceivable, he lost his desire to read and improve his intellect, and his spirits were broken. Covey was a most abominable man; he was duplicitous, merciless, fickle, and capable of savage brutality.

One day Douglass was very ill and could not complete his labor. This drew the attention of Covey, who beat Douglass until he was nearly senseless. Douglass resolved to journey to Master Thomas and beg him to protect him against Covey. Thomas was not amenable to this decision and Douglass had to travel back to the farm. On his way he stopped at the house of a wife of a fellow slave, Sandy. Sandy gave Douglass a special root and promised him that if he kept this root at his side he would never be touched again by a slaveholder. Douglass was skeptical but took the root.

When he arrived back at the farm Covey once again came upon him and began beating him. Douglass resolved that he would resist this time, and for over two hours the men were locked in combat. Douglass did not actually fight Covey but physically resisted the man's attacks. Finally Covey backed down and Douglass was free. For the duration of his stay on the farm Covey did not touch him, and Douglass believed it was his desire to keep his reputation that prevented him from turning Douglass in. This episode was the chief moment in Douglass's life; he viewed it as the time when he moved from being a slave to being a man.

After a year with Covey Douglass left and went to live on the farm of William Freeland . Freeland was the best master Douglass had; he was fair, honest, gave his slaves enough food and tools, and had no pretensions to piety. Douglass started a Sunday school for nearly forty slaves, teaching them how to read and write. As time passed Douglass became increasingly aware that he was getting older and he was still a slave. He resolved to devise a plan to escape. Several of his friends decided to join in the escape attempt, even though they were all aware of the possible dangers that awaited them.

However, the plot was discovered and the escape attempt foiled. Douglass and his friends were put into jail and Douglass's spirits were profoundly depressed. Finally he was released back into the custody of Hugh Auld in Baltimore. When he returned to the city he was allowed to be hired out to learn calking (waterproofing a ship). His first experience resulted in his being beaten by several white men, afraid they might lose their jobs to free blacks. Douglass went to another shipyard and worked diligently. Soon he was commanding high wages but was bitter that he had to turn nearly all of them over to Master Hugh. It was his taste of freedom and autonomy that revived within him the desire to escape, and he began to formulate a plan.

In order not to rouse the suspicions of his master, he worked assiduously at his calking. He was loath to leave his friends in Baltimore but knew that the time was come for him to try and go to the North. Finally, he achieved this escape; however, he did not publish any details in the Narrative as to not provoke danger to those who helped him or those who were still in slavery.

He arrived in New York and was exultant at his independence. Almost immediately, though, he felt lonely and lost in the city. If not for David Ruggles , a man who was most helpful to slaves and free blacks, he would have had a much more difficult time. In New York he was able to marry his love, Anna, and the two decided to move to New Bedford where it was safer. There Douglass found work and reveled in the ability to keep all of his wages and take on the responsibilities of an independent man. He even changed his name from Frederick Bailey to Frederick Douglass ; "Douglass" was suggested by a friend who had just read "Lady of the Lake".

Douglass experienced some prejudice working in New Bedford. He also began reading the prominent abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator , and was in awe of its impassioned denunciations of slavery. One day he attended an anti-slavery convention in Nantucket and was asked to speak. He took the stage, and although he was slightly nervous, he was able to tell his story. The Narrative concludes with his explanation that he has been doing this very thing ever since that fateful day.

The Appendix to the autobiography sets out Douglass's criticisms against the Christianity of slaveholders and explains to readers that Douglass is only critical of that very hypocritical type of religion, not religion in general. He locates authentic Christianity in the black community.

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass Questions and Answers

The Question and Answer section for Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass is a great resource to ask questions, find answers, and discuss the novel.

In paragraph 3, Mr. Auld says that if you give a slave "an inch, he will take an ell." What does he mean by this statement?

In context, he is saying that if you make a concession, you will be taken advantage of. This saying or quote first appeared in 1546 in a collection by John Heywood,

What event did Douglass indicate "made him a man"?

Although those are not the words he used, Douglass sae his employment in New Bedford... the day he began working for himself and his wife, the day that he truly became a man.

I found employment, the third day after my arrival, in stowing a sloop...

Why is freedom tormenting Douglass?

Douglass sees freedom everywhere and roused his "soul to eternal wakefulness". He still, however, remained enslaved.

Study Guide for Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave: Written by Himself study guide contains a biography of Frederick Douglass, literature essays, a complete e-text, quiz questions, major themes, characters, and a full summary and analysis.

- About Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass

- Character List

Essays for Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave: Written by Himself essays are academic essays for citation. These papers were written primarily by students and provide critical analysis of the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave: Written by Himself.

- Embracing the In-between: The Double Mental Life of Frederick Douglass

- An Analysis of the Different Forms of Freedom and Bondage Presented in the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave

- Humanization of a Murdered Girl in Douglass's Narrative

- The Political Station in Douglass’s “Narrative of the Life” and Emerson’s “Self-Reliance”

- Bound by Knowledge: Writing, Knowledge, and Freedom in Ishmael Reed's Flight to Canada and Frederick Douglass's The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass

Lesson Plan for Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass

- About the Author

- Study Objectives

- Common Core Standards

- Introduction to Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass

- Relationship to Other Books

- Bringing in Technology

- Notes to the Teacher

- Related Links

- Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass Bibliography

E-Text of Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave: Written by Himself e-text contains the full text of Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass.

Wikipedia Entries for Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass

- Introduction

- Publication history

- Reactions to the text

- Influence on contemporary black studies

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass was a leader in the abolitionist movement, an early champion of women’s rights and author of ‘Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass.’

(1818-1895)

Who Was Frederick Douglass?

Among Douglass’ writings are several autobiographies eloquently describing his experiences in slavery and his life after the Civil War , including the well-known work Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave .

Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey was born around 1818 into slavery in Talbot County, Maryland. As was often the case with slaves, the exact year and date of Douglass' birth are unknown, though later in life he chose to celebrate it on February 14.

Douglass initially lived with his maternal grandmother, Betty Bailey. At a young age, Douglass was selected to live in the home of the plantation owners, one of whom may have been his father.

His mother, who was an intermittent presence in his life, died when he was around 10.

Learning to Read and Write

Defying a ban on teaching slaves to read and write, Baltimore slaveholder Hugh Auld’s wife Sophia taught Douglass the alphabet when he was around 12. When Auld forbade his wife to offer more lessons, Douglass continued to learn from white children and others in the neighborhood.

It was through reading that Douglass’ ideological opposition to slavery began to take shape. He read newspapers avidly and sought out political writing and literature as much as possible. In later years, Douglass credited The Columbian Orator with clarifying and defining his views on human rights.

Douglass shared his newfound knowledge with other enslaved people. Hired out to William Freeland, he taught other slaves on the plantation to read the New Testament at a weekly church service.

Interest was so great that in any week, more than 40 slaves would attend lessons. Although Freeland did not interfere with the lessons, other local slave owners were less understanding. Armed with clubs and stones, they dispersed the congregation permanently.

With Douglass moving between the Aulds, he was later made to work for Edward Covey, who had a reputation as a "slave-breaker.” Covey’s constant abuse nearly broke the 16-year-old Douglass psychologically. Eventually, however, Douglass fought back, in a scene rendered powerfully in his first autobiography.

After losing a physical confrontation with Douglass, Covey never beat him again. Douglass tried to escape from slavery twice before he finally succeeded.

Wife and Children

Douglass married Anna Murray, a free Black woman, on September 15, 1838. Douglass had fallen in love with Murray, who assisted him in his final attempt to escape slavery in Baltimore.

On September 3, 1838, Douglass boarded a train to Havre de Grace, Maryland. Murray had provided him with some of her savings and a sailor's uniform. He carried identification papers obtained from a free Black seaman. Douglass made his way to the safe house of abolitionist David Ruggles in New York in less than 24 hours.

Once he had arrived, Douglass sent for Murray to meet him in New York, where they married and adopted the name of Johnson to disguise Douglass’ identity. Anna and Frederick then settled in New Bedford, Massachusetts, which had a thriving free Black community. There they adopted Douglass as their married name.

Douglass and Anna had five children together: Rosetta, Lewis Henry, Frederick Jr., Charles Redmond and Annie, who died at the age of 10. Charles and Rosetta assisted their father in the production of his newspaper The North Star . Anna remained a loyal supporter of Douglass' public work, despite marital strife caused by his relationships with several other women.

After Anna’s death, Douglass married Helen Pitts, a feminist from Honeoye, New York. Pitts was the daughter of Gideon Pitts Jr., an abolitionist colleague. A graduate of Mount Holyoke College , Pitts worked on a radical feminist publication and shared many of Douglass’ moral principles.

Their marriage caused considerable controversy, since Pitts was white and nearly 20 years younger than Douglass. Douglass’ children were especially displeased with the relationship. Nonetheless, Douglass and Pitts remained married until his death 11 years later.

Abolitionist

After settling as a free man with his wife Anna in New Bedford in 1838, Douglass was eventually asked to tell his story at abolitionist meetings, and he became a regular anti-slavery lecturer.

The founder of the weekly journal The Liberator , William Lloyd Garrison , was impressed with Douglass’ strength and rhetorical skill and wrote of him in his newspaper. Several days after the story ran, Douglass delivered his first speech at the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society's annual convention in Nantucket.

Crowds were not always hospitable to Douglass. While participating in an 1843 lecture tour through the Midwest, Douglass was chased and beaten by an angry mob before being rescued by a local Quaker family.

Following the publication of his first autobiography in 1845, Douglass traveled overseas to evade recapture. He set sail for Liverpool on August 16, 1845, and eventually arrived in Ireland as the Potato Famine was beginning. He remained in Ireland and Britain for two years, speaking to large crowds on the evils of slavery.

During this time, Douglass’ British supporters gathered funds to purchase his legal freedom. In 1847, the famed writer and orator returned to the United States a free man.

'The North Star'

Upon his return, Douglass produced some abolitionist newspapers: The North Star , Frederick Douglass Weekly , Frederick Douglass' Paper , Douglass' Monthly and New National Era .

The motto of The North Star was "Right is of no Sex – Truth is of no Color – God is the Father of us all, and we are all brethren."

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S FREDERICK DOUGLASS FACT CARD

'Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass'

In New Bedford, Massachusetts, Douglass joined a Black church and regularly attended abolitionist meetings. He also subscribed to Garrison's The Liberator .

At the urging of Garrison, Douglass wrote and published his first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave , in 1845. The book was a bestseller in the United States and was translated into several European languages.

Although the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass garnered Douglass many fans, some critics expressed doubt that a former enslaved person with no formal education could have produced such elegant prose.

Other Books by Frederick Douglass

Douglass published three versions of his autobiography during his lifetime, revising and expanding on his work each time. My Bondage and My Freedom appeared in 1855.

In 1881, Douglass published Life and Times of Frederick Douglass , which he revised in 1892.

Women’s Rights

In addition to abolition, Douglass became an outspoken supporter of women’s rights. In 1848, he was the only African American to attend the Seneca Falls convention on women's rights. Elizabeth Cady Stanton asked the assembly to pass a resolution stating the goal of women's suffrage. Many attendees opposed the idea.

Douglass, however, stood and spoke eloquently in favor, arguing that he could not accept the right to vote as a Black man if women could not also claim that right. The resolution passed.

Yet Douglass would later come into conflict with women’s rights activists for supporting the Fifteenth Amendment , which banned suffrage discrimination based on race while upholding sex-based restrictions.

Civil War and Reconstruction

By the time of the Civil War , Douglass was one of the most famous Black men in the country. He used his status to influence the role of African Americans in the war and their status in the country. In 1863, Douglass conferred with President Abraham Lincoln regarding the treatment of Black soldiers, and later with President Andrew Johnson on the subject of Black suffrage.

President Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation , which took effect on January 1, 1863, declared the freedom of enslaved people in Confederate territory. Despite this victory, Douglass supported John C. Frémont over Lincoln in the 1864 election, citing his disappointment that Lincoln did not publicly endorse suffrage for Black freedmen.

Slavery everywhere in the United States was subsequently outlawed by the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution .

Douglass was appointed to several political positions following the war. He served as president of the Freedman's Savings Bank and as chargé d'affaires for the Dominican Republic.

After two years, he resigned from his ambassadorship over objections to the particulars of U.S. government policy. He was later appointed minister-resident and consul-general to the Republic of Haiti, a post he held between 1889 and 1891.

In 1877, Douglass visited one of his former owners, Thomas Auld. Douglass had met with Auld's daughter, Amanda Auld Sears, years before. The visit held personal significance for Douglass, although some criticized him for the reconciliation.

Vice Presidential Candidate

Douglass became the first African American nominated for vice president of the United States as Victoria Woodhull 's running mate on the Equal Rights Party ticket in 1872.

Nominated without his knowledge or consent, Douglass never campaigned. Nonetheless, his nomination marked the first time that an African American appeared on a presidential ballot.

Douglass died on February 20, 1895, of a massive heart attack or stroke shortly after returning from a meeting of the National Council of Women in Washington, D.C. He was buried in Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester, New York.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Frederick Douglass

- Birth Year: 1818

- Birth State: Maryland

- Birth City: Tuckahoe

- Birth Country: United States

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Frederick Douglass was a leader in the abolitionist movement, an early champion of women’s rights and author of ‘Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass.’

- Interesting Facts

- Frederick Douglass first learned to read and write at the age of 12 from a Baltimore slaveholder's wife.

- To much controversy, Douglass married white abolitionist feminist Helen Pitts.

- Douglass became the first African American nominated for vice president of the United States.

- Death Year: 1895

- Death date: February 20, 1895

- Death City: Washington, D.C.

- Death Country: United States

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Frederick Douglass Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/activists/frederick-douglass

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E Television Networks

- Last Updated: July 15, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 3, 2014

- If there is no struggle there is no progress. . . . Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.

- Find out just what any people will quietly submit to and you have the exact measure of the injustice and wrong which will be imposed on them.

- I prefer to be true to myself, even at the hazard of incurring the ridicule of others, rather than to be false, and to incur my own abhorrence.

- No man can put a chain about the ankle of his fellow man without at last finding the other end fastened about his own neck.

- People might not get all they work for in this world, but they must certainly work for all they get.

- I would unite with anybody to do right and with nobody to do wrong.

- Where justice is denied, where poverty is enforced, where ignorance prevails, and where any one class is made to feel that society is an organized conspiracy to oppress, rob and degrade them, neither persons nor property will be safe.

- The life of the nation is secure only while the nation is honest, truthful, and virtuous.

- [I]n all the relations of life and death, we are met by the color line. We cannot ignore it if we would, and ought not if we could.

- If I ever had any patriotism, or any capacity for the feeling, it was whipt out of me long since by the lash of the American soul-drivers.

- The ground which a colored man occupies in this country is, every inch of it, sternly disputed.

- The lesson of all the ages on this point is, that a wrong done to one man is a wrong done to all men. It may not be felt at the moment, and the evil day may be long delayed, but so sure as there is a moral government of the universe, so sure will the harvest of evil come.

- Believing, as I do firmly believe, that human nature, as a whole, contains more good than evil, I am willing to trust the whole, rather than a part, in the conduct of human affairs.

- To educate a man is to unfit him to be a slave.

- To deny education to any people is one of the greatest crimes against human nature. It is easy to deny them the means of freedom and the rightful pursuit of happiness and to defeat the very end of their being.

- There is no negro problem. The problem is whether the American people have loyalty enough, honor enough, patriotism enough, to live up to their own constitution.

- Let us have no country but a free country, liberty for all and chains for none. Let us have one law, one gospel, equal rights for all, and I am sure God's blessing will be upon us and we shall be a prosperous and glorious nation.

Watch Next .css-smpm16:after{background-color:#323232;color:#fff;margin-left:1.8rem;margin-top:1.25rem;width:1.5rem;height:0.063rem;content:'';display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;}

Abolitionists

Harriet Tubman

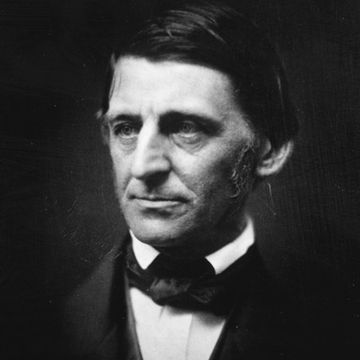

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Abraham Lincoln

Susan B. Anthony

Lucretia Mott

Harriet Beecher Stowe

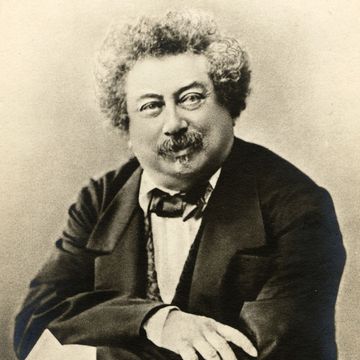

Alexandre Dumas

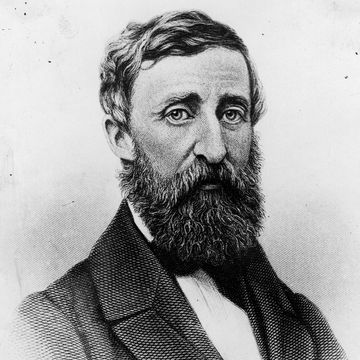

Henry David Thoreau

Mary Ann Shadd Cary

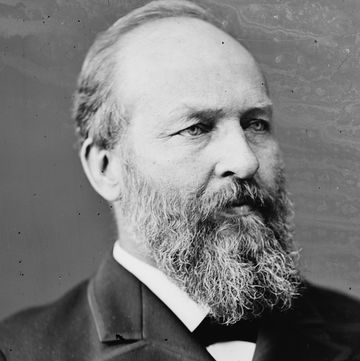

James Garfield

Jean-Jacques Dessalines

Frederick Douglass, 1818-1895 Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. Written by Himself Boston: Anti-Slavery Office, 1845.

Frederick Douglass is one of the most celebrated writers in the African American literary tradition, and his first autobiography is the one of the most widely read North American slave narratives. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave was published in 1845, less than seven years after Douglass escaped from slavery. The book was an instant success, selling 4,500 copies in the first four months. Throughout his life, Douglass continued to revise and expand his autobiography, publishing a second version in 1855 as My Bondage and My Freedom . The third version of Douglass' autobiography was published in 1881 as Life and Times of Frederick Douglass , and an expanded version of Life and Times was published in 1892. These various retellings of Douglass' story all begin with his birth and childhood, but each new version emphasizes the mutual influence and close correlation of Douglass' life with key events in American history.

Like many slave narratives, Douglass' Narrative is prefaced with endorsements by white abolitionists. In his preface, William Lloyd Garrison pledges that Douglass's Narrative is "essentially true in all its statements; that nothing has been set down in malice, nothing exaggerated" (p. viii ). Likewise, Wendell Phillips pledges "the most entire confidence in [Douglass'] truth, candor, and sincerity" (p. xiv ). Though Douglass counted Garrison and Phillips as friends, scholars such as Beth A. McCoy have argued that their letters serve as subtle reminders of white power over the black author and his text. Indeed, in all of his subsequent autobiographies, Douglass replaced Garrison and Phillips' endorsements with introductions by prominent black abolitionists and legal scholars.

Douglass begins his Narrative with what he knows about his birth in Tuckahoe, Maryland—or more precisely, what he does not know. "I have no accurate knowledge of my age," Douglass states; nor can he positively identify his father (p. 1 ). Douglass notes that it was "whispered that my master was my father . . . [but] the means of knowing was withheld from me" (p. 2). He recalls that he was separated from his mother "before I knew her as my mother," and that he saw her only "four or five times in my life" (p. 2 ). This separation of mothers from children, and lack of knowledge about age and paternity, Douglass explains, was common among slaves: "it is the wish of most masters . . . to keep their slaves thus ignorant" (p. 1 ).

As a child on the plantation of Colonel Edward Lloyd, Douglass witnesses brutal whippings of various slaves—male and female, old and young. But for the most part, he describes his childhood as a typical or representative story, rather than a unique or individual narrative. "[M]y own treatment . . . was very similar to that of the other slave children," he writes (p. 26 ). The early chapters of his Narrative emphasize the status of slaves and the nature of slavery over his individual experience. "I had no bed," he writes. "[I would] sleep on the cold, damp, clay floor, with my head in [a sack for carrying corn] and feet out" (p. 27 ). This description explicitly links Douglass' experience back to that of the other slaves: "old and young, male and female, married and single, drop down side by side, on one common bed,—the cold, damp floor,—each covering himself or herself with their miserable blankets" (p. 10-11 ).

At age seven, Douglass is sent to work for Hugh Auld, a ship carpenter in Baltimore. "A city slave is almost a freeman, compared with a slave on the plantation," he remarks, and the progression of Douglass' Narrative illustrates his increased liberty in the city (p. 34 ). The young Douglass' growing sense of freedom is due in part to his new master's wife, Sophia Auld, who "very kindly commenced to teach me the A, B, C" (p. 33 ). However, Hugh soon puts a stop to these reading lessons, warning his wife that learning to read "would forever unfit him to be a slave" (p. 33 ). Douglass takes this lesson to heart, noting that this incident "only served to inspire me with a desire and determination to learn" (p. 34 ). Over the next seven years, Douglass recalls, "I succeeded in learning to read and write . . . [through] various stratagems," including offering bread to hungry white children in exchange for reading lessons.

At age fifteen, Douglass is sent back to Colonel Lloyd's plantation to work for Hugh's brother, Thomas Auld, a ship captain. Here he is once again "made to feel the painful gnawings of hunger," and he begins to resist the tyranny of slavery more forcefully (p. 56 ). A few months later, Auld hires Douglass out to Edward Covey, a Methodist with a reputation for "breaking" recalcitrant slaves (p. 57 ). After a difficult year in which he is beaten, runs away, is recaptured, and finally battles Covey in a lengthy fistfight, Douglass is hired out to another landowner, William Freeland, to work as a field hand. Surviving his servitude under Mr. Covey seems to steel Douglass' desire for freedom, as his description of their fistfight reveals: "You have seen how a man was made a slave; you shall see how a slave was made a man" (p. 65-66 ).

Douglass does not provide the full details of his escape in his 1845 Narrative , for he fears that this information will prove useful to slave owners seeking to thwart or recapture future runaways. (He later provides an explanation of his escape in both versions of Life and Times of Frederick Douglass .) However, in his first autobiography Douglass does reveal that he is able to plan his escape when Hugh Auld allows him to work for wages at a Baltimore shipyard. Upon reaching the North, Douglass describes his sensations as "a moment of the highest excitement I have ever experienced . . . I felt like one who had escaped a den of hungry lions" (p. 107 ).

By the end of his Narrative , Douglass has resettled in New Bedford, Massachusetts, changed his name (which, until this time, was Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey), and married Anna Murray, a free black woman to whom he became engaged while still enslaved in Baltimore. In New Bedford, he is introduced to the members of William Lloyd Garrison's American Anti-Slavery Society. Douglass ends his narrative with a beginning, as he recalls his first public address before an audience of abolitionists. "From that time until now, I have been engaged in pleading the cause of my brethren," Douglass writes, leaving the future open for hopeful possibilities (p. 117 ).

Works Consulted : Andrews, William, To Tell a Free Story: The First Century of Afro-American Autobiography, 1760-1865 , Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1986; Blassingame, John W., and others, Eds., The Frederick Douglass Papers , Series Two, Vol. 1, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999; Douglass, Frederick, Autobiographies , Henry Louis Gates, Jr., ed., New York: Penguin Books, 1996; McCoy, Beth A, "Race and the (Para)Textual Condition," PMLA 121:1 (Jan 2006): 156-169.

Patrick E. Horn

Document menu

- Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. Written by Himself

Return to Library of Southern Literature Home Page

Return to North American Slave Narratives Home Page

Life and Times of Frederick Douglass

68 pages • 2 hours read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Chapter Summaries & Analyses

Part 1, Chapters 1-4

Part 1, Chapters 5-8

Part 1, Chapters 9-13

Part 1, Chapters 14-17

Part 1, Chapters 18-21

Part 2, Chapters 1-5

Part 2, Chapters 6-8

Part 2, Chapters 9-12

Part 2, Chapters 13-15

Part 2, Chapters 16-19

Part 3, Chapters 1-4

Part 3, Chapters 5-7

Part 3, Chapters 8-9

Part 3, Chapters 10-13

Key Figures

Index of Terms

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Summary and Study Guide

Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1892) is an autobiographical account written by one of the 19th century’s most famous Americans. Born a slave in Talbot County, Maryland, probably in the year 1817, young Frederick, later known as Frederick Douglass , escaped from slavery, joining the abolitionists, traveled abroad, met and counseled some of the era’s greatest statesmen, and fought a lifelong battle against color prejudice and injustice.

Get access to this full Study Guide and much more!

- 7,750+ In-Depth Study Guides

- 4,800+ Quick-Read Plot Summaries

- Downloadable PDFs

Life and Times of Frederick Douglass is essentially a history of Frederick Douglass’s public life—that is, the points at which his life converged with the 19th century’s most momentous events and developments. As such, after the opening chapters, in which Douglass describes his grandparents and the mother he barely knew, readers will find few details about Douglass’s private life apart from very brief references to his two marriages and the death of his young daughter. This is the story of both Douglass’s life and the times in which he lived.

Douglass divides the book into three parts. The first two were published in 1881; 10 years later, Douglass added the third. Douglass died in 1895, so this three-part autobiography, published in 1892, represents his most complete account of his life.

The SuperSummary difference

- 8x more resources than SparkNotes and CliffsNotes combined

- Study Guides you won ' t find anywhere else

- 175 + new titles every month

In the first section, “Life as a Slave,” Douglass establishes one of the book’s key themes: Slavery victimized everyone, from slaves to slaveholders. This point is not simply a magnanimous expression of forgiveness toward an unworthy class of tyrants; it is an insight into human nature. This first section tells the story of how Frederick came to understand the true nature of the slave system. In Baltimore, he learns to read and to pray. Armed with knowledge, and filled with Christ’s peace, he begins to think about the doctrine of natural rights and to question why he or anyone must be a slave for life. In an epic fight with the “negro-breaker” Edward Covey , Frederick learns the value of courage—another of the book’s main themes. Most important, he comes to regard slavery itself as the enemy.

The second part describes Douglass’s life as a free man, from his escape to the North in 1838 to the early months of 1881, when the book was first published. This second section covers the abolitionists’ moral crusade against slavery, the escalating sectional conflict of the 1850s, the Civil War, and the post-war struggle for civil rights. Scattered anecdotes reveal Douglass’s painful experiences with racial segregation and proscription in the North. A visit to Great Britain, where he feels no such ill treatment on account of his skin, convinces Douglass that color prejudice must be a uniquely American phenomenon—another of the book’s major themes. In all, more than 40 years of history appear in this section, which is a confluence of Douglass’s own history with that of the era. From these parallel histories, heroes emerge, including John Brown , Ulysses S. Grant , and Abraham Lincoln .

The third part, written in the early 1890s, picks up the story where Douglass left off in 1881. The events of the 1880s are far less dramatic than those described in earlier sections, but in some ways they are melancholier and more ominous. In 1881, Douglass has reason to look to the future with optimism. Emancipation and enfranchisement of the former slaves, once unthinkable, have been achieved. An unfavorable 1883 Supreme Court decision, however, made federal civil rights for Freedmen virtually unenforceable. Meanwhile, as former slaves struggle to find their way in a hostile world, and as “Lost Cause” mythologists retroactively ennoble the vanquished Confederates, the nation has become more race-obsessed than ever. Instead of justice and equality, Douglass sees Black people increasingly relegated to second-class citizenship.

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Related Titles

By Frederick Douglass

My Bondage and My Freedom

Frederick Douglass

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass

What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?

Featured Collections

American Civil War

View Collection

Black History Month Reads

Books on Justice & Injustice

Books on U.S. History

The Narrative of Frederick Douglass

Frederick douglass, ask litcharts ai: the answer to your questions.

The Fourth of July through the Eyes of Frederick Douglass

This essay is about Frederick Douglass’s speech “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” delivered on July 5, 1852. The speech critiques the hypocrisy of celebrating American freedom while millions of African Americans remained enslaved. Douglass contrasts the nation’s ideals of liberty and justice with the brutal reality of slavery, condemning both religious institutions and the government for their roles in perpetuating this injustice. He calls for a national reckoning and urges his audience to fight for true equality and abolition. The speech remains a powerful reminder of the ongoing struggle for justice and the need to align national values with actions.

How it works

Frederick Douglass, an erstwhile bondman and preeminent abolitionist, delivered one of his most renowned addresses, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” on July 5, 1852, in Rochester, New York. This discourse endures as a potent indictment of the paradoxes within American society, particularly the hypocrisy of extolling freedom and autonomy while perpetuating the blight of enslavement. Through his eloquence and incisive reasoning, Douglass laid bare the profound injustice and ethical lapses of a nation that extolled the virtues of liberty.

In his oration, Douglass commenced by acknowledging the triumphs of the American Revolution and the import of the Fourth of July for Caucasian Americans. He lauded the founding progenitors for their valor and unwavering commitment to the tenets of liberty and impartiality. Nonetheless, he swiftly pivoted to a stark juxtaposition, underscoring that the festivities held no pertinence for the multitudes of enchained African Americans. For them, the day epitomized the utmost irony, a derision of their anguish and debasement.

Douglass utilized the platform to underscore the profound inequity confronted by slaves. He contended that while Caucasian Americans reveled in their emancipation, they concurrently deprived an entire race of rudimentary human prerogatives. The principles of liberty, justice, and parity expounded by the Declaration of Independence were conspicuously absent in the lives of African Americans. He elucidated that the nation’s revelries served as a poignant reminder of the chasm between professed ideals and the harsh realities endured by those in bondage.

A substantial segment of Douglass’s discourse centered on the moral and ethical ramifications of slavery. He censured the ecclesiastical and religious institutions for their complicity in perpetuating the institution. By accentuating the Scriptures and Christian dogma, Douglass unveiled the hypocrisy of religious authorities who either sanctioned or remained silent on the matter of slavery. He impelled his audience to introspect their moral compass, urging them to acknowledge the intrinsic malevolence of slavery and to take a decisive stance against it.

Douglass also addressed the political milieu of the era, castigating the government and the statutes that perpetuated enslavement. He decried the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which mandated the repatriation of absconded slaves to their masters and penalized those who abetted in their escape. This legislation, he contended, was a flagrant affront to justice and humanity, illustrating the lengths to which the government would go to safeguard the interests of slaveholders.

The address was not merely a denunciation but also a clarion call to action. Douglass beseeched his audience to embrace the veritable principles of liberty and justice. He implored them to enlist in the struggle for abolition, to advocate for the cessation of enslavement, and to strive towards a more egalitarian society. His eloquence and fervent entreaty aimed to rouse the collective conscience of the nation and to catalyze support for the abolitionist cause.

Douglass’s discourse endures as a seminal opus in American oratory and literature. It constitutes a profound contemplation on the nation’s values and the inherent contradictions within its celebration of freedom. The address reverberates even today, serving as a poignant reminder of the enduring quests for justice and parity. It challenges us to contemplate the true import of liberty and the attendant responsibilities it entails.

In conclusion, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” by Frederick Douglass represents a potent critique of American society’s failure to uphold its professed ideals of liberty and justice. Delivered on July 5, 1852, the address underscores the profound hypocrisy of commemorating independence while millions remained ensnared in bondage. Douglass’s articulate and impassioned plea calls for a national reckoning with the injustices of enslavement and a steadfast commitment to the principles of genuine freedom and equality. His words persist as a source of inspiration and provocation, urging us to strive for a more equitable and inclusive society.

Cite this page

The Fourth of July Through the Eyes of Frederick Douglass. (2024, Jun 01). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/the-fourth-of-july-through-the-eyes-of-frederick-douglass/

"The Fourth of July Through the Eyes of Frederick Douglass." PapersOwl.com , 1 Jun 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/the-fourth-of-july-through-the-eyes-of-frederick-douglass/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). The Fourth of July Through the Eyes of Frederick Douglass . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-fourth-of-july-through-the-eyes-of-frederick-douglass/ [Accessed: 4 Jun. 2024]

"The Fourth of July Through the Eyes of Frederick Douglass." PapersOwl.com, Jun 01, 2024. Accessed June 4, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/the-fourth-of-july-through-the-eyes-of-frederick-douglass/

"The Fourth of July Through the Eyes of Frederick Douglass," PapersOwl.com , 01-Jun-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-fourth-of-july-through-the-eyes-of-frederick-douglass/. [Accessed: 4-Jun-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). The Fourth of July Through the Eyes of Frederick Douglass . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-fourth-of-july-through-the-eyes-of-frederick-douglass/ [Accessed: 4-Jun-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Frederick Douglass (born February 1818, Talbot county, Maryland, U.S.—died February 20, 1895, Washington, D.C.) was an African American abolitionist, orator, newspaper publisher, and author who is famous for his first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself.

The United States was deeply divided by the slavery issue at the time that the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass was published. While abolitionists like Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, and Wendell Phillips demanded the eradication of slavery, many worked hard to preserve the institution, and official U.S. policy merely postponed the inevitable conflict.

Ignorance as a Tool of Slavery. Douglass's Narrative shows how white slaveholders perpetuate slavery by keeping their slaves ignorant. At the time Douglass was writing, many people believed that slavery was a natural state of being. They believed that blacks were inherently incapable of participating in civil society and thus should be kept as workers for whites.

Frederick Douglass: Later Life and Death In 1877, Douglass met with Thomas Auld , the man who once "owned" him, and the two reportedly reconciled. Douglass' wife Anna died in 1882, and he ...

The Narrative of Frederick Douglass Summary. In approximately 1817, Frederick Douglass is born into slavery in Tuckahoe, Maryland. His mother is a slave named Harriet Bailey, and his father is an unknown white man who may be his master. Douglass encounters slavery's brutality at an early age when he witnesses his first master, Captain Anthony ...

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave is an 1845 memoir and treatise on abolition written by African-American orator and former slave Frederick Douglass during his time in Lynn, Massachusetts. It is the first of Douglass's three autobiographies, the others being My Bondage and My Freedom (1855) and Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1881, revised 1892).

Book Summary. Douglass' Narrative begins with the few facts he knows about his birth and parentage; his father is a slave owner and his mother is a slave named Harriet Bailey. Here and throughout the autobiography, Douglass highlights the common practice of white slave owners raping slave women, both to satisfy their sexual hungers and to ...

Frederick Douglass will forever remain one of the most important figures in America's struggle for civil rights and racial equality. His influence can be seen in the politics and writings of almost all major African-American writers, from Richard Wright to Maya Angelou. Douglass, however, is an inspiration to more than just African Americans.

Study Guide for Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave: Written by Himself study guide contains a biography of Frederick Douglass, literature essays, a complete e-text, quiz questions, major themes, characters, and a full summary and analysis.

Gender: Male. Best Known For: Frederick Douglass was a leader in the abolitionist movement, an early champion of women's rights and author of 'Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass ...

Summary. Frederick Douglass is one of the most celebrated writers in the African American literary tradition, and his first autobiography is the one of the most widely read North American slave narratives. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave was published in 1845, less than seven years after Douglass escaped from slavery.

Analysis. Douglass was born in Tuckahoe, Maryland. Like most slaves, he does not know when he was born, because masters usually try to keep their slaves from knowing their own ages. From the outset of the book, Douglass makes it clear that slaves are deprived of characteristics that humanize them, like birthdays. Douglass 's mother is named ...

Overview. Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1892) is an autobiographical account written by one of the 19th century's most famous Americans. Born a slave in Talbot County, Maryland, probably in the year 1817, young Frederick, later known as Frederick Douglass, escaped from slavery, joining the abolitionists, traveled abroad, met and ...

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, c. February 1817 or February 1818 - February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman.He became the most important leader of the movement for African-American civil rights in the 19th century.. After escaping from slavery in Maryland in 1838, Douglass became a national leader of the ...

Analysis. On January 1st, 1833, Douglass leaves Master Thomas 's to work as a field hand for Mr. Covey. Douglass's city upbringing makes him unfit for this labor. In the first few days, Covey sends Douglass with a team of oxen into the forest to retrieve some wood. Douglass does not know how to manage the oxen, and they startle and upset ...

Analysis. Douglass spends seven years living with Master Hugh 's family. During this time, he manages to teach himself to read and write, despite lacking any formal teacher. Mistress Sophia, having been reprimanded by her husband for teaching Douglass how to read, resolves not only to stop teaching Douglass but also to stand in the way of him ...

Full Book Summary. Frederick Douglass was born into slavery sometime in 1817 or 1818. Like many enslaved people, he is unsure of his exact date of birth. Douglass is separated from his mother, Harriet Bailey, soon after he is born. His father is most likely their white master, Captain Anthony. Captain Anthony is the clerk of a rich man named ...

Essay Example: Frederick Douglass, an erstwhile bondman and preeminent abolitionist, delivered one of his most renowned addresses, "What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?" on July 5, 1852, in Rochester, New York. This discourse endures as a potent indictment of the paradoxes within American