- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research Research Tools and Apps

Action Research: What it is, Stages & Examples

The best way to get things accomplished is to do it yourself. This statement is utilized in corporations, community projects, and national governments. These organizations are relying on action research to cope with their continuously changing and unstable environments as they function in a more interdependent world.

In practical educational contexts, this involves using systematic inquiry and reflective practice to address real-world challenges, improve teaching and learning, enhance student engagement, and drive positive changes within the educational system.

This post outlines the definition of action research, its stages, and some examples.

Content Index

What is action research?

Stages of action research, the steps to conducting action research, examples of action research, advantages and disadvantages of action research.

Action research is a strategy that tries to find realistic solutions to organizations’ difficulties and issues. It is similar to applied research.

Action research refers basically learning by doing. First, a problem is identified, then some actions are taken to address it, then how well the efforts worked are measured, and if the results are not satisfactory, the steps are applied again.

It can be put into three different groups:

- Positivist: This type of research is also called “classical action research.” It considers research a social experiment. This research is used to test theories in the actual world.

- Interpretive: This kind of research is called “contemporary action research.” It thinks that business reality is socially made, and when doing this research, it focuses on the details of local and organizational factors.

- Critical: This action research cycle takes a critical reflection approach to corporate systems and tries to enhance them.

All research is about learning new things. Collaborative action research contributes knowledge based on investigations in particular and frequently useful circumstances. It starts with identifying a problem. After that, the research process is followed by the below stages:

Stage 1: Plan

For an action research project to go well, the researcher needs to plan it well. After coming up with an educational research topic or question after a research study, the first step is to develop an action plan to guide the research process. The research design aims to address the study’s question. The research strategy outlines what to undertake, when, and how.

Stage 2: Act

The next step is implementing the plan and gathering data. At this point, the researcher must select how to collect and organize research data . The researcher also needs to examine all tools and equipment before collecting data to ensure they are relevant, valid, and comprehensive.

Stage 3: Observe

Data observation is vital to any investigation. The action researcher needs to review the project’s goals and expectations before data observation. This is the final step before drawing conclusions and taking action.

Different kinds of graphs, charts, and networks can be used to represent the data. It assists in making judgments or progressing to the next stage of observing.

Stage 4: Reflect

This step involves applying a prospective solution and observing the results. It’s essential to see if the possible solution found through research can really solve the problem being studied.

The researcher must explore alternative ideas when the action research project’s solutions fail to solve the problem.

Action research is a systematic approach researchers, educators, and practitioners use to identify and address problems or challenges within a specific context. It involves a cyclical process of planning, implementing, reflecting, and adjusting actions based on the data collected. Here are the general steps involved in conducting an action research process:

Identify the action research question or problem

Clearly define the issue or problem you want to address through your research. It should be specific, actionable, and relevant to your working context.

Review existing knowledge

Conduct a literature review to understand what research has already been done on the topic. This will help you gain insights, identify gaps, and inform your research design.

Plan the research

Develop a research plan outlining your study’s objectives, methods, data collection tools, and timeline. Determine the scope of your research and the participants or stakeholders involved.

Collect data

Implement your research plan by collecting relevant data. This can involve various methods such as surveys, interviews, observations, document analysis, or focus groups. Ensure that your data collection methods align with your research objectives and allow you to gather the necessary information.

Analyze the data

Once you have collected the data, analyze it using appropriate qualitative or quantitative techniques. Look for patterns, themes, or trends in the data that can help you understand the problem better.

Reflect on the findings

Reflect on the analyzed data and interpret the results in the context of your research question. Consider the implications and possible solutions that emerge from the data analysis. This reflection phase is crucial for generating insights and understanding the underlying factors contributing to the problem.

Develop an action plan

Based on your analysis and reflection, develop an action plan that outlines the steps you will take to address the identified problem. The plan should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART goals). Consider involving relevant stakeholders in planning to ensure their buy-in and support.

Implement the action plan

Put your action plan into practice by implementing the identified strategies or interventions. This may involve making changes to existing practices, introducing new approaches, or testing alternative solutions. Document the implementation process and any modifications made along the way.

Evaluate and monitor progress

Continuously monitor and evaluate the impact of your actions. Collect additional data, assess the effectiveness of the interventions, and measure progress towards your goals. This evaluation will help you determine if your actions have the desired effects and inform any necessary adjustments.

Reflect and iterate

Reflect on the outcomes of your actions and the evaluation results. Consider what worked well, what did not, and why. Use this information to refine your approach, make necessary adjustments, and plan for the next cycle of action research if needed.

Remember that participatory action research is an iterative process, and multiple cycles may be required to achieve significant improvements or solutions to the identified problem. Each cycle builds on the insights gained from the previous one, fostering continuous learning and improvement.

Explore Insightfully Contextual Inquiry in Qualitative Research

Here are two real-life examples of action research.

Action research initiatives are frequently situation-specific. Still, other researchers can adapt the techniques. The example is from a researcher’s (Franklin, 1994) report about a project encouraging nature tourism in the Caribbean.

In 1991, this was launched to study how nature tourism may be implemented on the four Windward Islands in the Caribbean: St. Lucia, Grenada, Dominica, and St. Vincent.

For environmental protection, a government-led action study determined that the consultation process needs to involve numerous stakeholders, including commercial enterprises.

First, two researchers undertook the study and held search conferences on each island. The search conferences resulted in suggestions and action plans for local community nature tourism sub-projects.

Several islands formed advisory groups and launched national awareness and community projects. Regional project meetings were held to discuss experiences, self-evaluations, and strategies. Creating a documentary about a local initiative helped build community. And the study was a success, leading to a number of changes in the area.

Lau and Hayward (1997) employed action research to analyze Internet-based collaborative work groups.

Over two years, the researchers facilitated three action research problem -solving cycles with 15 teachers, project personnel, and 25 health practitioners from diverse areas. The goal was to see how Internet-based communications might affect their virtual workgroup.

First, expectations were defined, technology was provided, and a bespoke workgroup system was developed. Participants suggested shorter, more dispersed training sessions with project-specific instructions.

The second phase saw the system’s complete deployment. The final cycle witnessed system stability and virtual group formation. The key lesson was that the learning curve was poorly misjudged, with frustrations only marginally met by phone-based technical help. According to the researchers, the absence of high-quality online material about community healthcare was harmful.

Role clarity, connection building, knowledge sharing, resource assistance, and experiential learning are vital for virtual group growth. More study is required on how group support systems might assist groups in engaging with their external environment and boost group members’ learning.

Action research has both good and bad points.

- It is very flexible, so researchers can change their analyses to fit their needs and make individual changes.

- It offers a quick and easy way to solve problems that have been going on for a long time instead of complicated, long-term solutions based on complex facts.

- If It is done right, it can be very powerful because it can lead to social change and give people the tools to make that change in ways that are important to their communities.

Disadvantages

- These studies have a hard time being generalized and are hard to repeat because they are so flexible. Because the researcher has the power to draw conclusions, they are often not thought to be theoretically sound.

- Setting up an action study in an ethical way can be hard. People may feel like they have to take part or take part in a certain way.

- It is prone to research errors like selection bias , social desirability bias, and other cognitive biases.

LEARN ABOUT: Self-Selection Bias

This post discusses how action research generates knowledge, its steps, and real-life examples. It is very applicable to the field of research and has a high level of relevance. We can only state that the purpose of this research is to comprehend an issue and find a solution to it.

At QuestionPro, we give researchers tools for collecting data, like our survey software, and a library of insights for any long-term study. Go to the Insight Hub if you want to see a demo or learn more about it.

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

Frequently Asked Questions(FAQ’s)

Action research is a systematic approach to inquiry that involves identifying a problem or challenge in a practical context, implementing interventions or changes, collecting and analyzing data, and using the findings to inform decision-making and drive positive change.

Action research can be conducted by various individuals or groups, including teachers, administrators, researchers, and educational practitioners. It is often carried out by those directly involved in the educational setting where the research takes place.

The steps of action research typically include identifying a problem, reviewing relevant literature, designing interventions or changes, collecting and analyzing data, reflecting on findings, and implementing improvements based on the results.

MORE LIKE THIS

Why Multilingual 360 Feedback Surveys Provide Better Insights

Jun 3, 2024

Raked Weighting: A Key Tool for Accurate Survey Results

May 31, 2024

Top 8 Data Trends to Understand the Future of Data

May 30, 2024

Top 12 Interactive Presentation Software to Engage Your User

May 29, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

- Our Mission

How Teachers Can Learn Through Action Research

A look at one school’s action research project provides a blueprint for using this model of collaborative teacher learning.

When teachers redesign learning experiences to make school more relevant to students’ lives, they can’t ignore assessment. For many teachers, the most vexing question about real-world learning experiences such as project-based learning is: How will we know what students know and can do by the end of this project?

Teachers at the Siena School in Silver Spring, Maryland, decided to figure out the assessment question by investigating their classroom practices. As a result of their action research, they now have a much deeper understanding of authentic assessment and a renewed appreciation for the power of learning together.

Their research process offers a replicable model for other schools interested in designing their own immersive professional learning. The process began with a real-world challenge and an open-ended question, involved a deep dive into research, and ended with a public showcase of findings.

Start With an Authentic Need to Know

Siena School serves about 130 students in grades 4–12 who have mild to moderate language-based learning differences, including dyslexia. Most students are one to three grade levels behind in reading.

Teachers have introduced a variety of instructional strategies, including project-based learning, to better meet students’ learning needs and also help them develop skills like collaboration and creativity. Instead of taking tests and quizzes, students demonstrate what they know in a PBL unit by making products or generating solutions.

“We were already teaching this way,” explained Simon Kanter, Siena’s director of technology. “We needed a way to measure, was authentic assessment actually effective? Does it provide meaningful feedback? Can teachers grade it fairly?”

Focus the Research Question

Across grade levels and departments, teachers considered what they wanted to learn about authentic assessment, which the late Grant Wiggins described as engaging, multisensory, feedback-oriented, and grounded in real-world tasks. That’s a contrast to traditional tests and quizzes, which tend to focus on recall rather than application and have little in common with how experts go about their work in disciplines like math or history.

The teachers generated a big research question: Is using authentic assessment an effective and engaging way to provide meaningful feedback for teachers and students about growth and proficiency in a variety of learning objectives, including 21st-century skills?

Take Time to Plan

Next, teachers planned authentic assessments that would generate data for their study. For example, middle school science students created prototypes of genetically modified seeds and pitched their designs to a panel of potential investors. They had to not only understand the science of germination but also apply their knowledge and defend their thinking.

In other classes, teachers planned everything from mock trials to environmental stewardship projects to assess student learning and skill development. A shared rubric helped the teachers plan high-quality assessments.

Make Sense of Data

During the data-gathering phase, students were surveyed after each project about the value of authentic assessments versus more traditional tools like tests and quizzes. Teachers also reflected after each assessment.

“We collated the data, looked for trends, and presented them back to the faculty,” Kanter said.

Among the takeaways:

- Authentic assessment generates more meaningful feedback and more opportunities for students to apply it.

- Students consider authentic assessment more engaging, with increased opportunities to be creative, make choices, and collaborate.

- Teachers are thinking more critically about creating assessments that allow for differentiation and that are applicable to students’ everyday lives.

To make their learning public, Siena hosted a colloquium on authentic assessment for other schools in the region. The school also submitted its research as part of an accreditation process with the Middle States Association.

Strategies to Share

For other schools interested in conducting action research, Kanter highlighted three key strategies.

- Focus on areas of growth, not deficiency: “This would have been less successful if we had said, ‘Our math scores are down. We need a new program to get scores up,’ Kanter said. “That puts the onus on teachers. Data collection could seem punitive. Instead, we focused on the way we already teach and thought about, how can we get more accurate feedback about how students are doing?”

- Foster a culture of inquiry: Encourage teachers to ask questions, conduct individual research, and share what they learn with colleagues. “Sometimes, one person attends a summer workshop and then shares the highlights in a short presentation. That might just be a conversation, or it might be the start of a school-wide initiative,” Kanter explained. In fact, that’s exactly how the focus on authentic assessment began.

- Build structures for teacher collaboration: Using staff meetings for shared planning and problem-solving fosters a collaborative culture. That was already in place when Siena embarked on its action research, along with informal brainstorming to support students.

For both students and staff, the deep dive into authentic assessment yielded “dramatic impact on the classroom,” Kanter added. “That’s the great part of this.”

In the past, he said, most teachers gave traditional final exams. To alleviate students’ test anxiety, teachers would support them with time for content review and strategies for study skills and test-taking.

“This year looks and feels different,” Kanter said. A week before the end of fall term, students were working hard on final products, but they weren’t cramming for exams. Teachers had time to give individual feedback to help students improve their work. “The whole climate feels way better.”

Action Research

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 01 January 2023

- Cite this reference work entry

- David Coghlan 2

415 Accesses

Action research is an approach to research which aims at both taking action and creating knowledge or theory about that action as the action unfolds. It starts with everyday experience and is concerned with the development of living knowledge. Its characteristics are that it generates practical knowledge in the pursuit of worthwhile purposes; it is participative and democratic as its participants work together in the present tense in defining the questions they wish to explore, the methodology for that exploration, and its application through cycles of action and reflection. In this vein they are agents of change and coresearchers in knowledge generation and not merely passive subjects as in traditional research. In this vein, action research can be understood as a social science of the possible as the collective action is focused on creating a desired future in whatever context the action research is located.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Banks, S., & Brydon-Miller, M. (2018). Ethics in participatory research for health and social well-being . Abingdon: Routledge.

Book Google Scholar

Bradbury, H. (2015). The Sage handbook of action research (3rd ed.). Sage: London.

Bradbury, H., Mirvis, P., Neilsen, E., & Pasmore, W. (2008). Action research at work: Creating the future following the path from Lewin. In P. Reason & H. Bradbury (Eds.), The Sage handbook of action research (2nd ed., pp. 77–92). London: Sage.

Chapter Google Scholar

Bradbury, H., Roth, J., & Gearty, M. (2015). The practice of learning history: Local and open approaches. In H. Bradbury (Ed.), The Sage handbook of action research (3rd ed., pp. 17–30). London: Sage.

Brydon-Miller, M., Greenwood, D., & Maguire, P. (2003). Why action research? Action Research, 1 (1), 9–28.034201[1476–7503(200307)1:1].

Article Google Scholar

Chevalier, J. M., & Buckles, D. J. (2019). Participatory action research. Theory and methods for engaged inquiry (2nd ed.). Abingdon: Routledge.

Coghlan, D. (2010). Seeking common ground in the diversity and diffusion of action research and collaborative management research action modalities: Toward a general empirical method. In W.A. Pasmore, A.B.. (Rami) Shani and R.W. Woodman (Eds.), Research in organizational change and development (vol 18, pp. 149–181). Bingley: Emerald.

Google Scholar

Coghlan, D. (2016). Retrieving the philosophy of practical knowing for action research. International Journal of Action Research, 12 , 84–107. https://doi.org/10.1688/IJAR-2016-01 .

Coghlan, D. (2019). Doing action research in your own organization (5th ed.). London: Sage.

Coghlan, D., & Brydon-Miller, M. (2014). The Sage encyclopedia of action research . London: Sage.

Coghlan, D., & Shani, A.B.. (Rami). (2017). Inquiring in the present tense: The dynamic mechanism of action research. Journal of Change Management , 17, 121–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2017.1301045 .

Coghlan, D., Shani, A.B.. (Rami), & Hay, G.W. (2019). Toward a social science philosophy of organization development and change. In D.A. Noumair & A.B.. (Rami) Shani (eds.). Research in organizational change and development (Vol. 27, pp. 1–29). Bingley: Emerald.

Gearty, M., & Coghlan, D. (2018). The first-, second- and third-person dynamics of learning history. Systemic Practice & Action Research., 31 , 463–478. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11213-017-9436-5 .

Greenwood, D., & Levin, M. (2007). Introduction to action research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Heron, J., & Reason, P. (1997). A participatory inquiry paradigm. Qualitative Inquiry, 3 , 274–294.

Heron, J., & Reason, P. (2008). Extending epistemology within a cooperative inquiry. In P. Reason & H. Bradbury (Eds.), The Sage handbook of action research (2nd ed., pp. 366–380). London: Sage.

Huxham, C. (2003). Actionresearch as a methodology for theory development. Policy and Politics, 31 (2), 239–248. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557303765371726 .

Koshy, E., Koshy, V., & Waterman, H. (2011). Action research in healthcare . London: Sage.

Lonergan, B. J. (2005). Dimensions of meaning. In B. J. Lonergan (Ed.), The collected work of Bernard Lonergan (Vol. 4, pp. 232–244). Toronto: Toronto University Press.

Marshall, J. (2016). First person action research: Living life as inquiry . London: Sage.

Owen, R., Bessant, J., & Heintz, M. (2013). Responsible innovation: Managing the responsible emergence of science and innovation in society . London: Wiley.

Pasmore, W. A. (2001). Action research in the workplace: The socio-technical perspective. In P. Reason & H. Bradbury (Eds.), The handbook of action research (pp. 38–47). London: Sage.

Revans, R. W. (1971). Developing effective managers . London: Longmans.

Revans, R. (1998). ABC of action learning . London: Lemos& Crane.

Schein, E. H. (2013). Humble inquiry: The gentle art of asking instead of telling . Oakland: Berrett-Kohler.

Shani, A.B.. (Rami), & Coghlan, D. (2019). Action research in business and management: A reflective review. Action Research . https://doi.org/10.1177/1476750319852147 .

Susman, G. I., & Evered, R. D. (1978). An assessment of the scientific merits of action research. Administrative Science Quarterly, 23 , 582–601. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392581 .

Torbert, W. R., & Associates. (2004). Action inquiry . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Whitney, D., & Trosten-Bloom, A. (2010). The power of appreciative inquiry: A practical guide to positive change . Oakland: Berrett-Kohler.

Williamson, G., & Bellman, L. (2012). Action research in nursing and healthcare . London: Sage.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Trinity Business School, University of Dublin Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland

David Coghlan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to David Coghlan .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Dublin City University, Dublin, Ireland

Vlad Petre Glăveanu

Section Editor information

Webster University Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland

Richard Randell

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Coghlan, D. (2022). Action Research. In: Glăveanu, V.P. (eds) The Palgrave Encyclopedia of the Possible. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-90913-0_180

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-90913-0_180

Published : 26 January 2023

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-90912-3

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-90913-0

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Original Language Spotlight

- Alternative and Non-formal Education

- Cognition, Emotion, and Learning

- Curriculum and Pedagogy

- Education and Society

- Education, Change, and Development

- Education, Cultures, and Ethnicities

- Education, Gender, and Sexualities

- Education, Health, and Social Services

- Educational Administration and Leadership

- Educational History

- Educational Politics and Policy

- Educational Purposes and Ideals

- Educational Systems

- Educational Theories and Philosophies

- Globalization, Economics, and Education

- Languages and Literacies

- Professional Learning and Development

- Research and Assessment Methods

- Technology and Education

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Action research.

- Eileen S. Johnson Eileen S. Johnson Oakland University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.696

- Published online: 29 May 2020

Action research has become a common practice among educational administrators. The term “action research” was first coined by Kurt Lewin in the 1930s, although teachers and school administrators have long engaged in the process described by and formally named by Lewin. Alternatively known as practitioner research, self-study, action science, site-based inquiry, emancipatory praxis, etc., action research is essentially a collaborative, democratic, and participatory approach to systematic inquiry into a problem of practice within a local context. Action research has become prevalent in many fields and disciplines, including education, health sciences, nursing, social work, and anthropology. This prevalence can be understood in the way action research lends itself to action-based inquiry, participation, collaboration, and the development of solutions to problems of everyday practice in local contexts. In particular, action research has become commonplace in educational administration preparation programs due to its alignment and natural fit with the nature of education and the decision making and action planning necessary within local school contexts. Although there is not one prescribed way to engage in action research, and there are multiple approaches to action research, it generally follows a systematic and cyclical pattern of reflection, planning, action, observation, and data collection, evaluation that then repeats in an iterative and ongoing manner. The goal of action research is not to add to a general body of knowledge but, rather, to inform local practice, engage in professional learning, build a community practice, solve a problem or understand a process or phenomenon within a particular context, or empower participants to generate self-knowledge.

- action research cycle

- educational practice

- historical trends

- philosophical assumptions

- variations of action research

You do not currently have access to this article

Please login to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Education. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 05 June 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|91.193.111.216]

- 91.193.111.216

Character limit 500 /500

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1 What is Action Research for Classroom Teachers?

ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS

- What is the nature of action research?

- How does action research develop in the classroom?

- What models of action research work best for your classroom?

- What are the epistemological, ontological, theoretical underpinnings of action research?

Educational research provides a vast landscape of knowledge on topics related to teaching and learning, curriculum and assessment, students’ cognitive and affective needs, cultural and socio-economic factors of schools, and many other factors considered viable to improving schools. Educational stakeholders rely on research to make informed decisions that ultimately affect the quality of schooling for their students. Accordingly, the purpose of educational research is to engage in disciplined inquiry to generate knowledge on topics significant to the students, teachers, administrators, schools, and other educational stakeholders. Just as the topics of educational research vary, so do the approaches to conducting educational research in the classroom. Your approach to research will be shaped by your context, your professional identity, and paradigm (set of beliefs and assumptions that guide your inquiry). These will all be key factors in how you generate knowledge related to your work as an educator.

Action research is an approach to educational research that is commonly used by educational practitioners and professionals to examine, and ultimately improve, their pedagogy and practice. In this way, action research represents an extension of the reflection and critical self-reflection that an educator employs on a daily basis in their classroom. When students are actively engaged in learning, the classroom can be dynamic and uncertain, demanding the constant attention of the educator. Considering these demands, educators are often only able to engage in reflection that is fleeting, and for the purpose of accommodation, modification, or formative assessment. Action research offers one path to more deliberate, substantial, and critical reflection that can be documented and analyzed to improve an educator’s practice.

Purpose of Action Research

As one of many approaches to educational research, it is important to distinguish the potential purposes of action research in the classroom. This book focuses on action research as a method to enable and support educators in pursuing effective pedagogical practices by transforming the quality of teaching decisions and actions, to subsequently enhance student engagement and learning. Being mindful of this purpose, the following aspects of action research are important to consider as you contemplate and engage with action research methodology in your classroom:

- Action research is a process for improving educational practice. Its methods involve action, evaluation, and reflection. It is a process to gather evidence to implement change in practices.

- Action research is participative and collaborative. It is undertaken by individuals with a common purpose.

- Action research is situation and context-based.

- Action research develops reflection practices based on the interpretations made by participants.

- Knowledge is created through action and application.

- Action research can be based in problem-solving, if the solution to the problem results in the improvement of practice.

- Action research is iterative; plans are created, implemented, revised, then implemented, lending itself to an ongoing process of reflection and revision.

- In action research, findings emerge as action develops and takes place; however, they are not conclusive or absolute, but ongoing (Koshy, 2010, pgs. 1-2).

In thinking about the purpose of action research, it is helpful to situate action research as a distinct paradigm of educational research. I like to think about action research as part of the larger concept of living knowledge. Living knowledge has been characterized as “a quest for life, to understand life and to create… knowledge which is valid for the people with whom I work and for myself” (Swantz, in Reason & Bradbury, 2001, pg. 1). Why should educators care about living knowledge as part of educational research? As mentioned above, action research is meant “to produce practical knowledge that is useful to people in the everyday conduct of their lives and to see that action research is about working towards practical outcomes” (Koshy, 2010, pg. 2). However, it is also about:

creating new forms of understanding, since action without reflection and understanding is blind, just as theory without action is meaningless. The participatory nature of action research makes it only possible with, for and by persons and communities, ideally involving all stakeholders both in the questioning and sense making that informs the research, and in the action, which is its focus. (Reason & Bradbury, 2001, pg. 2)

In an effort to further situate action research as living knowledge, Jean McNiff reminds us that “there is no such ‘thing’ as ‘action research’” (2013, pg. 24). In other words, action research is not static or finished, it defines itself as it proceeds. McNiff’s reminder characterizes action research as action-oriented, and a process that individuals go through to make their learning public to explain how it informs their practice. Action research does not derive its meaning from an abstract idea, or a self-contained discovery – action research’s meaning stems from the way educators negotiate the problems and successes of living and working in the classroom, school, and community.

While we can debate the idea of action research, there are people who are action researchers, and they use the idea of action research to develop principles and theories to guide their practice. Action research, then, refers to an organization of principles that guide action researchers as they act on shared beliefs, commitments, and expectations in their inquiry.

Reflection and the Process of Action Research

When an individual engages in reflection on their actions or experiences, it is typically for the purpose of better understanding those experiences, or the consequences of those actions to improve related action and experiences in the future. Reflection in this way develops knowledge around these actions and experiences to help us better regulate those actions in the future. The reflective process generates new knowledge regularly for classroom teachers and informs their classroom actions.

Unfortunately, the knowledge generated by educators through the reflective process is not always prioritized among the other sources of knowledge educators are expected to utilize in the classroom. Educators are expected to draw upon formal types of knowledge, such as textbooks, content standards, teaching standards, district curriculum and behavioral programs, etc., to gain new knowledge and make decisions in the classroom. While these forms of knowledge are important, the reflective knowledge that educators generate through their pedagogy is the amalgamation of these types of knowledge enacted in the classroom. Therefore, reflective knowledge is uniquely developed based on the action and implementation of an educator’s pedagogy in the classroom. Action research offers a way to formalize the knowledge generated by educators so that it can be utilized and disseminated throughout the teaching profession.

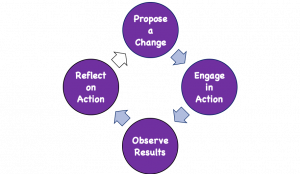

Research is concerned with the generation of knowledge, and typically creating knowledge related to a concept, idea, phenomenon, or topic. Action research generates knowledge around inquiry in practical educational contexts. Action research allows educators to learn through their actions with the purpose of developing personally or professionally. Due to its participatory nature, the process of action research is also distinct in educational research. There are many models for how the action research process takes shape. I will share a few of those here. Each model utilizes the following processes to some extent:

- Plan a change;

- Take action to enact the change;

- Observe the process and consequences of the change;

- Reflect on the process and consequences;

- Act, observe, & reflect again and so on.

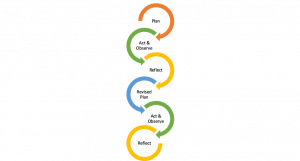

Figure 1.1 Basic action research cycle

There are many other models that supplement the basic process of action research with other aspects of the research process to consider. For example, figure 1.2 illustrates a spiral model of action research proposed by Kemmis and McTaggart (2004). The spiral model emphasizes the cyclical process that moves beyond the initial plan for change. The spiral model also emphasizes revisiting the initial plan and revising based on the initial cycle of research:

Figure 1.2 Interpretation of action research spiral, Kemmis and McTaggart (2004, p. 595)

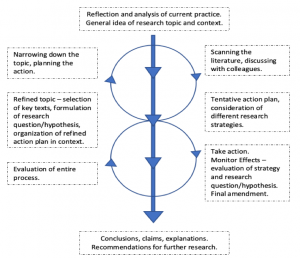

Other models of action research reorganize the process to emphasize the distinct ways knowledge takes shape in the reflection process. O’Leary’s (2004, p. 141) model, for example, recognizes that the research may take shape in the classroom as knowledge emerges from the teacher’s observations. O’Leary highlights the need for action research to be focused on situational understanding and implementation of action, initiated organically from real-time issues:

Figure 1.3 Interpretation of O’Leary’s cycles of research, O’Leary (2000, p. 141)

Lastly, Macintyre’s (2000, p. 1) model, offers a different characterization of the action research process. Macintyre emphasizes a messier process of research with the initial reflections and conclusions as the benchmarks for guiding the research process. Macintyre emphasizes the flexibility in planning, acting, and observing stages to allow the process to be naturalistic. Our interpretation of Macintyre process is below:

Figure 1.4 Interpretation of the action research cycle, Macintyre (2000, p. 1)

We believe it is important to prioritize the flexibility of the process, and encourage you to only use these models as basic guides for your process. Your process may look similar, or you may diverge from these models as you better understand your students, context, and data.

Definitions of Action Research and Examples

At this point, it may be helpful for readers to have a working definition of action research and some examples to illustrate the methodology in the classroom. Bassey (1998, p. 93) offers a very practical definition and describes “action research as an inquiry which is carried out in order to understand, to evaluate and then to change, in order to improve educational practice.” Cohen and Manion (1994, p. 192) situate action research differently, and describe action research as emergent, writing:

essentially an on-the-spot procedure designed to deal with a concrete problem located in an immediate situation. This means that ideally, the step-by-step process is constantly monitored over varying periods of time and by a variety of mechanisms (questionnaires, diaries, interviews and case studies, for example) so that the ensuing feedback may be translated into modifications, adjustment, directional changes, redefinitions, as necessary, so as to bring about lasting benefit to the ongoing process itself rather than to some future occasion.

Lastly, Koshy (2010, p. 9) describes action research as:

a constructive inquiry, during which the researcher constructs his or her knowledge of specific issues through planning, acting, evaluating, refining and learning from the experience. It is a continuous learning process in which the researcher learns and also shares the newly generated knowledge with those who may benefit from it.

These definitions highlight the distinct features of action research and emphasize the purposeful intent of action researchers to improve, refine, reform, and problem-solve issues in their educational context. To better understand the distinctness of action research, these are some examples of action research topics:

Examples of Action Research Topics

- Flexible seating in 4th grade classroom to increase effective collaborative learning.

- Structured homework protocols for increasing student achievement.

- Developing a system of formative feedback for 8th grade writing.

- Using music to stimulate creative writing.

- Weekly brown bag lunch sessions to improve responses to PD from staff.

- Using exercise balls as chairs for better classroom management.

Action Research in Theory

Action research-based inquiry in educational contexts and classrooms involves distinct participants – students, teachers, and other educational stakeholders within the system. All of these participants are engaged in activities to benefit the students, and subsequently society as a whole. Action research contributes to these activities and potentially enhances the participants’ roles in the education system. Participants’ roles are enhanced based on two underlying principles:

- communities, schools, and classrooms are sites of socially mediated actions, and action research provides a greater understanding of self and new knowledge of how to negotiate these socially mediated environments;

- communities, schools, and classrooms are part of social systems in which humans interact with many cultural tools, and action research provides a basis to construct and analyze these interactions.

In our quest for knowledge and understanding, we have consistently analyzed human experience over time and have distinguished between types of reality. Humans have constantly sought “facts” and “truth” about reality that can be empirically demonstrated or observed.

Social systems are based on beliefs, and generally, beliefs about what will benefit the greatest amount of people in that society. Beliefs, and more specifically the rationale or support for beliefs, are not always easy to demonstrate or observe as part of our reality. Take the example of an English Language Arts teacher who prioritizes argumentative writing in her class. She believes that argumentative writing demonstrates the mechanics of writing best among types of writing, while also providing students a skill they will need as citizens and professionals. While we can observe the students writing, and we can assess their ability to develop a written argument, it is difficult to observe the students’ understanding of argumentative writing and its purpose in their future. This relates to the teacher’s beliefs about argumentative writing; we cannot observe the real value of the teaching of argumentative writing. The teacher’s rationale and beliefs about teaching argumentative writing are bound to the social system and the skills their students will need to be active parts of that system. Therefore, our goal through action research is to demonstrate the best ways to teach argumentative writing to help all participants understand its value as part of a social system.

The knowledge that is conveyed in a classroom is bound to, and justified by, a social system. A postmodernist approach to understanding our world seeks knowledge within a social system, which is directly opposed to the empirical or positivist approach which demands evidence based on logic or science as rationale for beliefs. Action research does not rely on a positivist viewpoint to develop evidence and conclusions as part of the research process. Action research offers a postmodernist stance to epistemology (theory of knowledge) and supports developing questions and new inquiries during the research process. In this way action research is an emergent process that allows beliefs and decisions to be negotiated as reality and meaning are being constructed in the socially mediated space of the classroom.

Theorizing Action Research for the Classroom

All research, at its core, is for the purpose of generating new knowledge and contributing to the knowledge base of educational research. Action researchers in the classroom want to explore methods of improving their pedagogy and practice. The starting place of their inquiry stems from their pedagogy and practice, so by nature the knowledge created from their inquiry is often contextually specific to their classroom, school, or community. Therefore, we should examine the theoretical underpinnings of action research for the classroom. It is important to connect action research conceptually to experience; for example, Levin and Greenwood (2001, p. 105) make these connections:

- Action research is context bound and addresses real life problems.

- Action research is inquiry where participants and researchers cogenerate knowledge through collaborative communicative processes in which all participants’ contributions are taken seriously.

- The meanings constructed in the inquiry process lead to social action or these reflections and action lead to the construction of new meanings.

- The credibility/validity of action research knowledge is measured according to whether the actions that arise from it solve problems (workability) and increase participants’ control over their own situation.

Educators who engage in action research will generate new knowledge and beliefs based on their experiences in the classroom. Let us emphasize that these are all important to you and your work, as both an educator and researcher. It is these experiences, beliefs, and theories that are often discounted when more official forms of knowledge (e.g., textbooks, curriculum standards, districts standards) are prioritized. These beliefs and theories based on experiences should be valued and explored further, and this is one of the primary purposes of action research in the classroom. These beliefs and theories should be valued because they were meaningful aspects of knowledge constructed from teachers’ experiences. Developing meaning and knowledge in this way forms the basis of constructivist ideology, just as teachers often try to get their students to construct their own meanings and understandings when experiencing new ideas.

Classroom Teachers Constructing their Own Knowledge

Most of you are probably at least minimally familiar with constructivism, or the process of constructing knowledge. However, what is constructivism precisely, for the purposes of action research? Many scholars have theorized constructivism and have identified two key attributes (Koshy, 2010; von Glasersfeld, 1987):

- Knowledge is not passively received, but actively developed through an individual’s cognition;

- Human cognition is adaptive and finds purpose in organizing the new experiences of the world, instead of settling for absolute or objective truth.

Considering these two attributes, constructivism is distinct from conventional knowledge formation because people can develop a theory of knowledge that orders and organizes the world based on their experiences, instead of an objective or neutral reality. When individuals construct knowledge, there are interactions between an individual and their environment where communication, negotiation and meaning-making are collectively developing knowledge. For most educators, constructivism may be a natural inclination of their pedagogy. Action researchers have a similar relationship to constructivism because they are actively engaged in a process of constructing knowledge. However, their constructions may be more formal and based on the data they collect in the research process. Action researchers also are engaged in the meaning making process, making interpretations from their data. These aspects of the action research process situate them in the constructivist ideology. Just like constructivist educators, action researchers’ constructions of knowledge will be affected by their individual and professional ideas and values, as well as the ecological context in which they work (Biesta & Tedder, 2006). The relations between constructivist inquiry and action research is important, as Lincoln (2001, p. 130) states:

much of the epistemological, ontological, and axiological belief systems are the same or similar, and methodologically, constructivists and action researchers work in similar ways, relying on qualitative methods in face-to-face work, while buttressing information, data and background with quantitative method work when necessary or useful.

While there are many links between action research and educators in the classroom, constructivism offers the most familiar and practical threads to bind the beliefs of educators and action researchers.

Epistemology, Ontology, and Action Research

It is also important for educators to consider the philosophical stances related to action research to better situate it with their beliefs and reality. When researchers make decisions about the methodology they intend to use, they will consider their ontological and epistemological stances. It is vital that researchers clearly distinguish their philosophical stances and understand the implications of their stance in the research process, especially when collecting and analyzing their data. In what follows, we will discuss ontological and epistemological stances in relation to action research methodology.

Ontology, or the theory of being, is concerned with the claims or assumptions we make about ourselves within our social reality – what do we think exists, what does it look like, what entities are involved and how do these entities interact with each other (Blaikie, 2007). In relation to the discussion of constructivism, generally action researchers would consider their educational reality as socially constructed. Social construction of reality happens when individuals interact in a social system. Meaningful construction of concepts and representations of reality develop through an individual’s interpretations of others’ actions. These interpretations become agreed upon by members of a social system and become part of social fabric, reproduced as knowledge and beliefs to develop assumptions about reality. Researchers develop meaningful constructions based on their experiences and through communication. Educators as action researchers will be examining the socially constructed reality of schools. In the United States, many of our concepts, knowledge, and beliefs about schooling have been socially constructed over the last hundred years. For example, a group of teachers may look at why fewer female students enroll in upper-level science courses at their school. This question deals directly with the social construction of gender and specifically what careers females have been conditioned to pursue. We know this is a social construction in some school social systems because in other parts of the world, or even the United States, there are schools that have more females enrolled in upper level science courses than male students. Therefore, the educators conducting the research have to recognize the socially constructed reality of their school and consider this reality throughout the research process. Action researchers will use methods of data collection that support their ontological stance and clarify their theoretical stance throughout the research process.

Koshy (2010, p. 23-24) offers another example of addressing the ontological challenges in the classroom:

A teacher who was concerned with increasing her pupils’ motivation and enthusiasm for learning decided to introduce learning diaries which the children could take home. They were invited to record their reactions to the day’s lessons and what they had learnt. The teacher reported in her field diary that the learning diaries stimulated the children’s interest in her lessons, increased their capacity to learn, and generally improved their level of participation in lessons. The challenge for the teacher here is in the analysis and interpretation of the multiplicity of factors accompanying the use of diaries. The diaries were taken home so the entries may have been influenced by discussions with parents. Another possibility is that children felt the need to please their teacher. Another possible influence was that their increased motivation was as a result of the difference in style of teaching which included more discussions in the classroom based on the entries in the dairies.

Here you can see the challenge for the action researcher is working in a social context with multiple factors, values, and experiences that were outside of the teacher’s control. The teacher was only responsible for introducing the diaries as a new style of learning. The students’ engagement and interactions with this new style of learning were all based upon their socially constructed notions of learning inside and outside of the classroom. A researcher with a positivist ontological stance would not consider these factors, and instead might simply conclude that the dairies increased motivation and interest in the topic, as a result of introducing the diaries as a learning strategy.

Epistemology, or the theory of knowledge, signifies a philosophical view of what counts as knowledge – it justifies what is possible to be known and what criteria distinguishes knowledge from beliefs (Blaikie, 1993). Positivist researchers, for example, consider knowledge to be certain and discovered through scientific processes. Action researchers collect data that is more subjective and examine personal experience, insights, and beliefs.

Action researchers utilize interpretation as a means for knowledge creation. Action researchers have many epistemologies to choose from as means of situating the types of knowledge they will generate by interpreting the data from their research. For example, Koro-Ljungberg et al., (2009) identified several common epistemologies in their article that examined epistemological awareness in qualitative educational research, such as: objectivism, subjectivism, constructionism, contextualism, social epistemology, feminist epistemology, idealism, naturalized epistemology, externalism, relativism, skepticism, and pluralism. All of these epistemological stances have implications for the research process, especially data collection and analysis. Please see the table on pages 689-90, linked below for a sketch of these potential implications:

Again, Koshy (2010, p. 24) provides an excellent example to illustrate the epistemological challenges within action research:

A teacher of 11-year-old children decided to carry out an action research project which involved a change in style in teaching mathematics. Instead of giving children mathematical tasks displaying the subject as abstract principles, she made links with other subjects which she believed would encourage children to see mathematics as a discipline that could improve their understanding of the environment and historic events. At the conclusion of the project, the teacher reported that applicable mathematics generated greater enthusiasm and understanding of the subject.

The educator/researcher engaged in action research-based inquiry to improve an aspect of her pedagogy. She generated knowledge that indicated she had improved her students’ understanding of mathematics by integrating it with other subjects – specifically in the social and ecological context of her classroom, school, and community. She valued constructivism and students generating their own understanding of mathematics based on related topics in other subjects. Action researchers working in a social context do not generate certain knowledge, but knowledge that emerges and can be observed and researched again, building upon their knowledge each time.

Researcher Positionality in Action Research

In this first chapter, we have discussed a lot about the role of experiences in sparking the research process in the classroom. Your experiences as an educator will shape how you approach action research in your classroom. Your experiences as a person in general will also shape how you create knowledge from your research process. In particular, your experiences will shape how you make meaning from your findings. It is important to be clear about your experiences when developing your methodology too. This is referred to as researcher positionality. Maher and Tetreault (1993, p. 118) define positionality as:

Gender, race, class, and other aspects of our identities are markers of relational positions rather than essential qualities. Knowledge is valid when it includes an acknowledgment of the knower’s specific position in any context, because changing contextual and relational factors are crucial for defining identities and our knowledge in any given situation.

By presenting your positionality in the research process, you are signifying the type of socially constructed, and other types of, knowledge you will be using to make sense of the data. As Maher and Tetreault explain, this increases the trustworthiness of your conclusions about the data. This would not be possible with a positivist ontology. We will discuss positionality more in chapter 6, but we wanted to connect it to the overall theoretical underpinnings of action research.

Advantages of Engaging in Action Research in the Classroom

In the following chapters, we will discuss how action research takes shape in your classroom, and we wanted to briefly summarize the key advantages to action research methodology over other types of research methodology. As Koshy (2010, p. 25) notes, action research provides useful methodology for school and classroom research because:

Advantages of Action Research for the Classroom

- research can be set within a specific context or situation;

- researchers can be participants – they don’t have to be distant and detached from the situation;

- it involves continuous evaluation and modifications can be made easily as the project progresses;

- there are opportunities for theory to emerge from the research rather than always follow a previously formulated theory;

- the study can lead to open-ended outcomes;

- through action research, a researcher can bring a story to life.

Action Research Copyright © by J. Spencer Clark; Suzanne Porath; Julie Thiele; and Morgan Jobe is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

How Action Research Can Improve Your Teaching

Do you ever find yourself looking at a classroom problem with not a clue in the world about how to fix it? No doubt, teaching art is difficult. Sometimes the issues we face don’t have easy solutions.

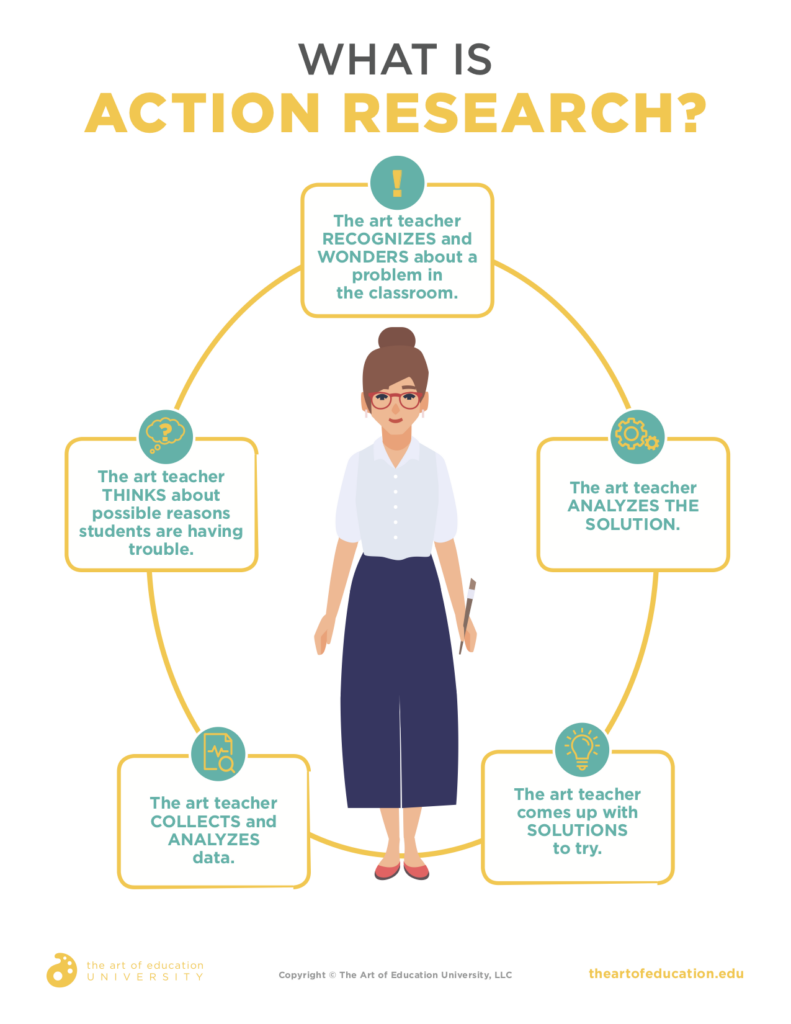

One method that is worth looking into is action research. In action research, a teacher takes the time to analyze a problem and then cycles through specific steps to solve it. If you’re struggling with a problem in your classroom, this might be the perfect strategy to try!

What is action research?

Simply put, action research describes a research methodology used to diagnose and address problems. In a school setting, the teacher plays the role of the researcher, and the students represent the study participants. Action research is a meaningful way for a teacher to find out why students perform the way they do.

The term, “action research,” was coined in 1933 by Kurt Lewin to describe a scenario in which a researcher and participants collaborate to solve a specific problem. Donald Schön developed this idea further with the term, “reflective practitioner,” to describe a researcher who thinks systematically about their practice.

Educators have taken both of these ideas into the classroom to better serve their students.

Here is a look at the basic structure of an action research cycle. You might notice it looks a lot like the Design Thinking Process.

- The teacher recognizes and wonders about a problem in the classroom.

- The teacher thinks about possible reasons students are having trouble.

- The teacher collects and analyzes data.

- The teacher comes up with solutions to try.

- The teacher analyzes the solution.

In this model, if the first solution is not effective, the cycle starts over again. The teacher recognizes what remains of the problem and repeats the steps to collect more evidence and brainstorm new and different solutions.

Download What Is Action Research?

Download Now!

Because the process is cyclical, the teacher can loop through the steps as many times as needed to find a solution. Perhaps the best part of action research is that teachers can see which solutions have made a real impact on their students. If you’re looking for an even more in-depth take on the topic, The Art of Classroom Inquiry: A Handbook for Teacher-Researchers by Hubbard and Powers is a great place to start.

Action research can be as informal or formal as you need it to be. Data is collected through observation, questioning, and discussion with students. Student artwork, photographs of your classroom at work, video interviews, and surveys are all valid forms of data. Students can be involved throughout the whole process, helping to solve the problem within the classroom. With a formal study for a university, there will be requests for permission to use student data through the Institutional Research Board (IRB) process.

How can action research be implemented in your classroom?

I discovered action research while working on my higher degree. Using action research allowed me to find real solutions for real issues in my classroom and gave me my topic of study for my dissertation at the same time!

The problem I chose to address was how to engage students in an analog photography course in the digital age.

I broke my classes into two groups. I taught the district curriculum to one group and an altered curriculum to another. In the altered version, I included big ideas and themes that were important to students such as family, identity, and community.

To gather data, I observed, compared the quality of the photos, and conducted student interviews. I found students were much more engaged when I switched the projects from a technical study (i.e., demonstrating depth of field) to a more personal focus (breaking the teenage stereotype.)

What are the benefits of action research?

Using action research in my classroom allowed me to involve students in the curriculum process. They were actively more engaged within the classroom and felt ownership of their learning.

I was able to show them that teachers can be lifelong learners, and that inquiry is a powerful way to enact change within the classroom. The students cheered me on as I was writing and defended the results of my study. Plus, I was able to connect with them on a personal level, as we were all students. Furthermore, my teaching practice became more confident, and my understanding of art education theory deepened.

Conducting action research also allowed me to become a leader in my community. I was able to present a way to be a reflective practitioner within my classroom and model it for other teachers. I shared my new knowledge with the other art teachers in my district and invited them to try their own informal studies within their classrooms. We were able to shift our focus from one of compliance to one of inquiry and discovery, thus creating a more engaging learning environment for our students.

Action research provides a way to use your new knowledge immediately in your classroom. It allows you to think critically about why and how you run your art classroom. What could be better?

What kinds of issues are you facing in the classroom right now?

What kind of research study might you be interested in conducting?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.

Alexandra Overby

Alexandra Overby, a high school art educator, is one of AOEU’s Adjunct Instructors. She immerses herself in topics of photography practice, visual ethnography, technology in the art room, and secondary curriculum.

Daring Art Crimes for the Art Teacher That You Won’t Be Able to Put Down!

3 Things to Appreciate in Each Phase of an Art Teacher’s Career

2 Incredible Ways to Revive Your Passion for Art Education This Spring

Get the Scoop: AOEU Insider Tips For Your Next Art Education Conference

- Open access

- Published: 03 June 2024

Continue nursing education: an action research study on the implementation of a nursing training program using the Holton Learning Transfer System Inventory

- MingYan Shen 1 , 2 &

- ZhiXian Feng 1 , 2

BMC Medical Education volume 24 , Article number: 610 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

25 Accesses

Metrics details

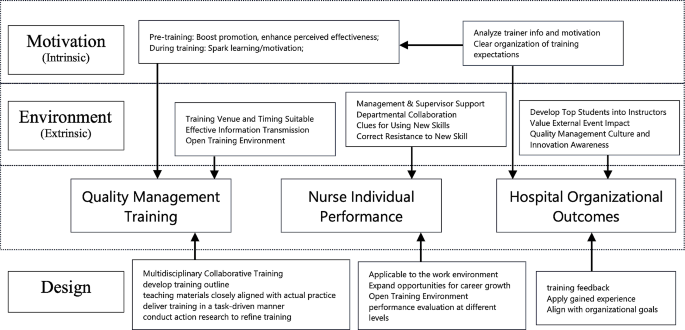

To address the gap in effective nursing training for quality management, this study aims to implement and assess a nursing training program based on the Holton Learning Transfer System Inventory, utilizing action research to enhance the practicality and effectiveness of training outcomes.

The study involved the formation of a dedicated training team, with program development informed by an extensive situation analysis and literature review. Key focus areas included motivation to transfer, learning environment, and transfer design. The program was implemented in a structured four-step process: plan, action, observation, reflection.

Over a 11-month period, 22 nurses completed 14 h of theoretical training and 18 h of practical training with a 100% attendance rate and 97.75% satisfaction rate. The nursing team successfully led and completed 22 quality improvement projects, attaining a practical level of application. Quality management implementation difficulties, literature review, current situation analysis, cause analysis, formulation of plans, implementation plans, and report writing showed significant improvement and statistical significance after training.

The study confirms the efficacy of action research guided by Holton’s model in significantly enhancing the capabilities of nursing staff in executing quality improvement projects, thereby improving the overall quality of nursing training. Future research should focus on refining the training program through long-term observation, developing a multidimensional evaluation index system, exploring training experiences qualitatively, and investigating the personality characteristics of nurses to enhance training transfer effects.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

The “Medical Quality Management Measures“ [ 1 ] and “Accreditation Standards for Tertiary Hospitals (2020 Edition)” [ 2 ] both emphasize the importance of using quality management tools in medical institutions to carry out effective quality management [ 3 ]. However, there is a notable gap in translating theoretical training into effective, practical application in clinical settings [ 4 ]. This gap is further highlighted in the context of healthcare quality management, as evidenced in studies [ 5 ] which demonstrate the universality of these challenges across healthcare systems worldwide.

Addressing this issue, contemporary literature calls for innovative and effective training methods that transition from passive knowledge acquisition to active skill application [ 6 ]. The Holton Learning Transfer System Inventory [ 7 ] provides a framework focusing on key factors such as motivation, learning environment, and transfer design [ 7 , 8 , 9 ]. This study aims to implement a nursing training program based on the Holton model, using an action research methodology to bridge the theoretical-practical gap in nursing education.

Quality management training for clinical nurses has predominantly been characterized by short-term theoretical lectures, a format that often fails to foster deep engagement and lasting awareness among nursing personnel [ 10 ]. The Quality Indicator Project in Taiwan’s nursing sector, operational for over a decade, demonstrates the effective use of collective intelligence and scientific methodologies to address these challenges [ 11 ]. The proposed study responds to the need for training programs that not only impart knowledge but also ensure the practical application of skills in real-world nursing settings, thereby contributing to transformative changes within the healthcare system [ 12 ].

In April 2021, the Nursing Education Department of our hospital launched a quality improvement project training program for nurses. The initiation of this study is underpinned by the evident disconnect between theoretical training and the practical challenges nurses face in implementing quality management initiatives, a gap also identified in the work [ 13 ]. By exploring the efficacy of the Holton Learning Transfer System Inventory, this study seeks to enhance the practical application of training and significantly contribute to the field of nursing education and quality management in healthcare.

Developing a nursing training program with the Holton Learning Transfer System Inventory

Establishing a research team and assigning roles.

There are 10 members in the group who serve as both researchers and participants, aiming to investigate training process issues and solutions. The roles within the group are as follows: the deputy dean in charge of nursing is responsible for program review and organizational support, integrating learning transfer principles in different settings [ 14 ]; the deputy director of the Nursing Education Department handles the design and implementation of the training program, utilizing double-loop learning for training transfer [ 15 ]; the deputy director of the Nursing Department oversees quality control and project evaluation, ensuring integration of evidence-based practices and technology [ 16 ] and the deputy director of the Quality Management Office provides methodological guidance. The remaining members consist of 4 faculty members possessing significant university teaching experience and practical expertise in quality control projects, and 2 additional members who are jointly responsible for educational affairs, data collection, and analysis. Additionally, to ensure comprehensive pedagogical guidance in this training, professors specializing in nursing pedagogy have been specifically invited to provide expertise on educational methodology.

Current situation survey

Based on the Holton Learning Transfer System Inventory (refer to Fig. 1 ), the appropriate levels of Motivation to Improve Work Through Learning (MTIWL), learning environment, and transfer design are crucial in facilitating changes in individual performance, thereby influencing organizational outcomes [ 17 , 18 ]. Motivation to Improve Work Through Learning (MTIWL) is closely linked to expectation theory, fairness theory, and goal-setting theory, significantly impacting the positive transfer of training [ 19 ]. Learning environment encompasses environmental factors that either hinder or promote the application of learned knowledge in actual work settings [ 20 ]. Transfer design, as a pivotal component, includes training program design and organizational planning.

To conduct the survey, the research team retrieved 26 quality improvement reports from the nursing quality information management system, which were generated by nursing units in 2020. A checklist was formulated, and a retrospective evaluation was conducted across eight aspects, namely, team participation, topic selection feasibility, method accuracy, indicator scientificity, program implementation rate, effect maintenance, and promotion and application. Methods employed in the evaluation process included report analysis, on-site tracking, personnel interviews, and data review within the quality information management system [ 21 ]. From the perspective of motivation [ 22 ], learning environment [ 23 ], and transfer design, a total of 14 influencing factors were identified. These factors serve as a reference for designing the training plan and encompass the following aspects: lack of awareness regarding importance, low willingness to participate in training, unclear understanding of individual career development, absence of incentive mechanisms, absence of a scientific training organization model, lack of a training quality management model, inadequate literature retrieval skills and support, insufficient availability of practical training materials and resources, incomplete mastery of post-training methods, lack of cultural construction plans, suboptimal communication methods and venues, weak internal organizational atmosphere, inadequate leadership support, and absence of platforms and mechanisms for promoting and applying learned knowledge.

Learning Transfer System Inventory

Development of the training program using the 4W1H approach

Drawing upon Holton’s Learning Transfer System Inventory and the hospital training transfer model diagram, a comprehensive training outline was formulated for the training program [ 24 , 25 ]. The following components were considered:

(1) Training Participants (Who): The training is open for voluntary registration to individuals with an undergraduate degree or above, specifically targeting head nurses, responsible team leaders, and core members of the hospital-level nursing quality control team. Former members who have participated in quality improvement projects such as Plan-Do-Check-Act Circle (PDCA) or Quality control circle (QCC) are also eligible.

(2) Training Objectives (Why): At the individual level, the objectives include enhancing the understanding of quality management concepts, improving the cognitive level and application abilities of project improvement methods, and acquiring the necessary skills for nursing quality improvement project. At the team level, the aim is to enhance effective communication among team members and elevate the overall quality of communication. Moreover, the training seeks to facilitate collaborative efforts in improving the existing nursing quality management system and processes. At the operational level, participants are expected to gain the competence to design, implement, and manage nursing quality improvement project initiatives. Following the training, participants will lead and successfully complete a nursing quality improvement project, which will undergo a rigorous audit.

(3) Training Duration (When): The training program spans a duration of 11 months.

(4) Training Content (What): The program consists of 14 h of theoretical courses and 18 h of practical training sessions, as detailed in Table 1 .