Sorin Adam Matei

Professor of Communication, Associate Dean of Research, Brian Lamb School of Communication, College of Liberal Arts, Purdue University

Knowledge Gap Hypothesis and Digital Divides – A review of the literature and impact on social media research

This is a learning module for the class Contemporary Social / Mass Media Theory taught at Purdue University by Sorin Adam Matei

Knowledge gap hypothesis proposes that more information does not always mean a better informed public, or at least that not all members of the public will be be better informed to the same degree. To the contrary, as some members of the public might become better informed, some might in fact lag farther behind in terms of knowledge about important issues of the day. In other words, the slopes of the curves of information gain are more abrupt for some and flatter for other. The angle of the slope seems to be determined by socio-economic status. The final outcome of this process is that as we add more educational and information resources, the ones that have better chances to absorb them will get much more out of them than those that have lesser socio-economic resources. Or, in more vernacular terms, the richer (materially) become even richer (intellectually), while the poor will, although getting something out of this intellectual evolution, do not get nearly as much of it. Thus, the difference is not defined in terms of “some get, while some lose,” but in terms of “some get, while some get even more”… The knowledge gap as been recast more recently as a “digital divide” gap. With the Internet and social media many things can be done faster and better. So much faster and better that those that do not have access to them are literally left out of the game. Two readings highlight the issues involved in the digital divide debate.

Knowledge Gap Assumptions

Mass Media Flow and Differential Growth in Knowledge P. J. Tichenor, G. A. Donohue and C. N. Olien The Public Opinion Quarterly Vol. 34, No. 2 (Summer, 1970), pp. 159-170 Published by: Oxford University Press on behalf of the American Association for Public Opinion Research

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2747414 (please search library database for full citation if the links do not work)

Data from four types of research-news diffusion studies, time trends, a newspaper strike, and a field experiment-are consistent with the general hypothesis that increasing the flow of news on a topic leads to greater acquisition of knowledge about that topic among the more highly educated segments of society. Whether the resulting knowledge gap closes may depend partly on whether the stimulus intensity of mass media publicity is maintained at a high level, or is reduced or eliminated at a point when only the more active persons have gained that knowledge. There are several contributory reasons why the predicted knowledge gap should appear and widen with increasing levels of media input. One factor is communication skills . Persons with more formal education would be expected to have the higher reading and comprehension abilities necessary to acquire public affairs or science knowledge. A second factor is amount of stored information , or existing knowledge resulting from prior exposure to the topic through mass media or from formal education itself. Persons who are already better informed are more likely to be aware of a topic when it appears in the mass media and are better prepared to understand it. A third factor is relevant social contact . Education generally indicates a broader sphere of everyday activity, a greater number of reference groups, and more interpersonal contacts, which increase the likelihood of discussing public affairs topics with others. Studies of diffusion among such groups as doctors and farmers tend to show steeper, more accelerated acceptance rates for more active, socially integrated individuals. A fourth factor includes selective exposure, acceptance, and retention of informatio n. As Sears and Freedman have pointed out, voluntary exposure is often more closely related to education than to any other set of variables. They contend that what appears to be selective exposure according to attitudes might often more appropriately be called “de facto” selectivity resulting from educational differences.’ Selective acceptance and retention, however, might be a joint result of attitude and educational differences. A persistent theme in mass media research is the apparent tendency to interpret and recall information in ways congruent with existing beliefs and values.’ A final factor is the nature of the mass media system that delivers information. Thus far, most science and public affairs news (with the possible recent exceptions of crisis events and space spectaculars) is carried in print media which, traditionally, have been more heavily used by higher-status persons. Print media are geared to the interests and tastes of this higher-status segment and may taper off on reporting many topics when they begin to lose the novel characteristic of “news.” Unlike a great deal of contemporary advertising, science and public affairs news ordinarily lacks the constant repetition which facilitates learning and familiarity among lower-status persons. The knowledge gap hypothesis might be expressed, operationally, in at least two different ways: 1. Over time, acquisition of knowledge of a heavily publicized topic will proceed at a faster rate among better educated persons than among those with less education; and 2. At a given point in time, there should be a higher correlation between acquisition of knowledge and education for topics highly publicized in the media than for topics less highly publicized. One would expect the knowledge gap to be especially prominent when one or more of the contributory factors is operative. Thus, to the extent that communication skills, prior knowledge, social contact, or attitudinal selectivity is engaged, the gap should widen as heavy mass media flow continues.

Mass Media and the Knowledge Gap A Hypothesis Reconsidered G.A. Donohue, P.J. Tichenor, C.N. Olien, University of Minnesota, doi: 10.1177/009365027500200101 Communication Research January 1975 vol. 2 no. 1 3-23 – Try this link while on campus or GET FROM LIBRARY STACKS (Blame the library…)

A principal consequence of mass media coverage about national public affairs issues, particularly from print media, appears to be an increasing “knowledge gap” between various social strata. Previous data presented by the authors were concerned with issues largely external to the local community. More recent work raises the question whether social conflict about a community issue will tend to open the gap further, or close it. Survey data from fifteen Minnesota communities experiencing conflicts of varying magnitude indicate that as level of conflict about local issues increases, the knowledge gap actually tends to decline. Level of interpersonal communication about the issue appears to be a major intervening variable. Thus, it appears that the knowledge gap hypothesis needs to be modified according to the type of issue involved and the conflict dimensions of the issue within the community.

Citizens, Knowledge, and the Information Environment, Jennifer Jerit1, Jason Barabas2, Toby Bolsen3 Article first published online: 29 MAR 2006, DOI: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00183.x, American Journal of Political Science Volume 50, Issue 2, pages 266–282, April 2006

In a democracy, knowledge is power. Research explaining the determinants of knowledge focuses on unchanging demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. This study combines data on the public’s knowledge of nearly 50 political issues with media coverage of those topics. In a two-part analysis, we demonstrate how education, the strongest and most consistent predictor of political knowledge, has a more nuanced connection to learning than is commonly recognized. Sometimes education is positively related to knowledge. In other instances its effect is negligible. A substantial part of the variation in the education-knowledge relationship is due to the amount of information available in the mass media. This study is among the first to distinguish the short-term, aggregate-level influences on political knowledge from the largely static individual-level predictors and to empirically demonstrate the importance of the information environment.

REVISITING THE KNOWLEDGE GAP HYPOTHESIS: A META-ANALYSIS OF THIRTY-FIVE YEARS OF RESEARCH Hwang, Yoori; Jeong, Se-Hoon. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly86. 3(Autumn 2009): 513-532.

This present study, a meta-analysis providing a systematic summary of previous research on the knowledge gap hypothesis, has three specific goals: (a) to obtain an average size for the knowledge gap, (b) to examine the impact of media publicity on the knowledge gap, and (c) to identify conditions (e.g., topic, knowledge measurement, country, and publication status) under which the gap increases or decreases. Consistent with previous reviews,43 the results show that knowledge disparities exist across social strata. The average effect size of the relationship between education and knowledge acquisition was moderate (r = .28). However, according to this meta-analytic review, the gap in knowledge did not change either over time or with varying levels of media publicity.

Does the Digital Divide Matter More? Comparing the Effects of New Media and Old Media Use on the Education-Based Knowledge Gap DOI:10.1080/15205431003642707 Lu Weia & Douglas Blanks Hindmanb, pages 216-235

As the Internet has become increasingly widespread in the world, some researchers suggested a conceptual shift of the digital divide from material access to actual use. Although this shift has been incorporated into the more broad social inclusion agenda, the social consequences of the digital divide have not yet received adequate attention. Recognizing that political knowledge is a critical social resource associated with power and inclusion, this study empirically examines the relationship between the digital divide and the knowledge gap. Based on the 2008–2009 American National Election Studies panel data, this research found that, supporting the shift of the academic agenda, socioeconomic status is more closely associated with the informational use of the Internet than with access to the Internet. In addition, socioeconomic status is more strongly related to the informational use of the Internet than with that of the traditional media, particularly newspapers and television. More importantly, the differential use of the Internet is associated with a greater knowledge gap than that of the traditional media. These findings suggest that the digital divide, which can be better defined as inequalities in the meaningful use of information and communication technologies, matters more than its traditional counterpart.

Digital divide research, achievements and shortcomings Original Research Article, Poetics, Volume 34, Issues 4–5, August–October 2006, Pages 221-235 Jan A.G.M. van Dijk

From the end of the 1990s onwards the digitaldivide, commonly defined as the gap between those who have and do not have access to computers and the Internet, has been a central issue on the scholarly and political agenda of new media development. This article makes an inventory of 5 years of digitaldivide research (2000–2005). The article focuses on three questions. (1) To what type of inequality does the digitaldivide concept refer? (2) What is new about the inequality of access to and use of ICTs as compared to other scarce material and immaterial resources? (3) Do new types of inequality exist or rise in the information society? The results of digitaldivide research are classified under four successive types of access: motivational, physical, skills and usage. A shift of attention from physical access to skills and usage is observed. In terms of physical access the divide seems to be closing in the most developed countries; concerning digital skills and the use of applications the divide persists or widens. Among the shortcomings of digitaldivide research are its lack of theory, conceptual definition, interdisciplinary approach, qualitative research and longitudinal research.

- ← In Search of the Ur-Wikipedia: Universality, Similarity, and Translation in the Wikipedia Inter-language Link Network

- Hurricane Sandy Probable Landfall, Path, and Impact Cone (kmz from NOAA) →

Associate Dean of Research and Professor of Communication at Purdue University, Director of the FORCES initiative leads research teams that study the relationship between technological and social systems using big data, simulation, and mapping approaches. He published papers and articles in Journal of Communication, Communication Research, Information Society, National Interest, and Foreign Policy . He is the author or co-editor of several books. The most recent is Structural differentation in social media . He also co-edited Ethical Reasoning in Big Data , Transparency in social media and Roles, Trust, and Reputation in Social Media Knowledge Markets: Theory and Methods (Computational Social Sciences) , all three the product of the NSF funded KredibleNet project . Dr. Matei's teaching portfolio includes technology and strategy, online interaction, and digital media analytics classes. A former BBC World Service journalist, his contributions have been published in Esquire and several leading Romanian newspapers. In Romania, he is known for his books Boierii Mintii (The Mind Boyars) , Idolii forului (Idols of the forum) , and Idei de schimb (Spare ideas) .

You May Also Like

Digital Scholarship in Humanities and Social Sciences Course – 63200 Graduate Seminar at Purdue University Taught by Sorin Adam Matei

Post 02/20/2009.

#Snowden #Prism revelations goads Google to reveal number of judicial requests by country

23 thoughts on “ knowledge gap hypothesis and digital divides – a review of the literature and impact on social media research ”.

I find the readings are very interesting because the knowledge gap hypothesis (KGH) takes a rather pessimistic view on the difference between the knowledge acquisitions of higher and lower social strata. The KGH explains how a knowledge gap exists between people with high and low social strata. This is not to say that lower social strata does not obtain knowledge but that they obtain knowledge in a lower degree then those with a higher social strata (Tichenor, Donohue & Olien, 1970). How wide the knowledge gap is between social strata can be said to depend on the medium used, as mediums like television and radio actually affords nearly the same acquisition of knowledge to all social strata (Jerit, Barabas & Bolsen, 2006; Wei & Hindman, 2011). This is also the argument put forth by Jerit et. al (2006) when they describe the KGH literature as being too pessimistic. I argue that the pessimistic nature in the body of literature of KGH is not to be discarded when it comes to the concern for democracy and emancipation of the different strata. If we are to believe that we live in an converge culture where content is converging thru the Internet and hardware is becoming more and more situational (Jenkins, n.d.) the findings of Wei and Hindman (2011) does indeed suggest that we are to be pessimistic about the future and the knowledge gap between different strata. Wei and Hindman’s findings suggest that there is a significant difference and gap between the knowledge obtained by higher and lower social strata when the Internet is the medium of knowledge gathering. This can be a problem because more and more content is converging to the Internet and as such “the Internet may function to reinforce inequalities of power and knowledge, producing deeper gaps between the information rich and poor, and between the activists and the disengaged” (Wei & Hindman, 2011: p. 230).

This raises some very serious concerns in regards to democracy and the emancipation of strata not only because more and more content is converging on the Internet but also because the habits of Internet users are used to determining the content that are delivered (Praiser, 2011). As online-algorisms or ‘ the filter bobble’ becomes more and more advanced in determining the preference of Internet users (Paiser, 2011) lower social strata’s use of the Internet to seek non-informational content can become a self-reinforcing element in the knowledge gap between the different strata. Therefore the Internet can be seen as affording a wider knowledge gap between strata, which might be widened further by the ongoing development of targeted content and online-algorisms. This could potentially be a major challenge to democracy as it requires an informed citizenry and as such begs for further investigation by scholars.

Works Cited Jenkins, H. (n.d.). Receiver#12. Retrieved Oct. 4, 2012, from Welcome to convergence culture: http://karactar.tistory.com/attachment/gk050000000003.pdf

Jerit, J., Barabas, J., & Bolsen, T. (2006). Citizens, Knowledge, and the Information Environment. American Journal of Political Science , 50 (2), 266-282.

Pariser, E. (2011). The Filter Bobble. New York: The Penguin Press.

Tiehenor, P. J., Donohue, G., & Olien, C. (1970). Mass Media Flow and Differential Growth in Knowledge. The Public Opinion Quarterly , 34 (2), 169-170.

Wei, L., & Hindman, D. B. (2011). Does the Digital Divide Matter More? Comparing the Effects of New Media and Old Media Use on the Education-Based Knowledge Gap. Mass Communication and Society , 14 (2), 216-235.

As presented and discussed in the readings for this week, the concept of the knowledge gap is concerning. The knowledge gap hypothesis (KGH) states that as information disseminates in a society, individuals possessing higher socioeconomic status acquire new knowledge and information at a faster rate than those with lower socioeconomic status. While everyone benefits from new knowledge, individuals with higher socioeconomic status benefit more overall. This different results in a widening gap between those with high and low socioeconomic status, where high socioeconomic status individuals experience more relative benefits with every new piece of information (Tichenor, Donohue, & Olien, 1970; Wei & Hindman, 2011). In relation to technology, this idea has been examined as the digital divide. Originally, the digital divide addressed access to technology, drawing a line between those individuals who had access to computers or other new media technology, and those that did not (Wei & Hindman, 2011). Recently, research on the digital divide and knowledge gap has switched from focusing on access to technology to how the technology is used (Tichenor, Donohue, & Olien, 1970). Overall, these studies have found patterns similar to research addressing traditional media; individuals of higher socioeconomic status experience more benefits from their Internet use. With new media technology, this benefit seems to stem from the use of technology for information-gathering purposes. Some research has not only found that the traditional knowledge gap exists when considering new media, but that the gap widens at a faster rate (Wei & Hindman, 2011). This discovery is partially attributed to the sheer amount of diverse information available on the Internet; higher socioeconomic status individuals are more likely to seek out new information, and new media technology provide a portal to a vast amount of knowledge. The Internet is not restricted in the same ways that newspapers or TV media are – stories do not fight for page placement or time-slot length, so more information is available for discovery overall (Wei & Hindman, 2011).

I am curious about the role of social media, particularly Facebook, in this context. Facebook primarily functions as a location to establish a personal network among friends, family, and acquaintances by sharing information, pictures, status updates, and other information ( http://facebook.com/facebook ). Users can create their own content or share the content of others, including images, videos, and links to third party websites. Facebook use is not restricted by socioeconomic status or education level (as long as users have access to a computer). Visiting Facebook is not necessarily the result of active political or education information-seeking behavior; generally, users visit to create content, catch up with friends and family, or out of habit. The interesting consideration here is the actual content displayed on a given user’s newsfeed. On a given day, my newsfeed presents the usual pictures and status updates, along with comics, updates on my favorite actors, TV shows, or movies, links to entertaining or enlightening articles posted on third-party websites, or political commentary in a variety of forms. What I select to take a closer look at depends on my mood at the time of log-in, how much time I have available, my relationship with the poster, and my particular interest in a given idea. A given user can only be exposed to the information posted by members of their established Facebook network; arguably, given that Facebook connections are usually based on real-life relationships, users surround themselves with-like minded individuals. Network members may not hold the same viewpoints or opinions, but are connected in some way – affiliation through school or work, family, etc; the resulting information presented on a newsfeed will most likely be a mix of familiar or relatable and novel information. In this particular case, the information is neither as heterogeneous as the content of the Internet as a whole, nor as homogenous as a newscast displayed in multiple neighborhoods. While I find this idea interesting, it raises more questions in my mind than answers:

– How does this network-generated source of information contribute to the digital divide? I would assume that the effects become increasingly individualized, depending on the specific members of an individual’s network, the content posted by those members, and the content engaged with by the user herself.

– What happens to the general effect of increased knowledge for all when Facebook is used as a knowledge source? We can assume that a news broadcast does indeed reach a certain number of people, and we can make educated guesses about the levels of diversity in the audience. On Facebook, different stories and information will disseminate through different networks at varying rates. Perhaps there are demographic factors that relate to the networks through which the information spreads, but I would think that personal interest of users would be a more influential factor here.

Facebook. (2013). http://facebook.com/facebook

Tichenor, P. J., Donohue, G. A., & Olien, C. N. (1970). Mass media flow and differential growth in knowledge. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 34(2), 159-170.

Wei, L. & Hindman, D. B. (2011). Does the digital divide matter more? Comparing the effects of new media and old media use on the education-based knowledge gap. Mass Communication and Society, 14(2), 216-235.

The “digital divide” is a term used by scholars to encompass the various inequalities in Internet access and use. The driving force behind this area of research is an argument that differences in access and use mean that some benefit more than others from new technologies like the Internet, with such benefits including gains in knowledge and social capital (Wei & Hindman, 2011). Those who benefit are often seen to be those already privileged within the global and local power systems based on existing demographic variables (i.e. issues of income, education, status, sex, nationality, ethnicity, etc.) (van Dijk, 2006). While such a “divide” is problematic and worth examining, the use of the term and the related concepts of “access” and “use” seems to be vague, making it challenging to study.

First, the “digital divide” has become a very broad concept. It has evolved from referring only to a simplistic gap between those who have or do not have physical access to new information and communication technologies to also speak to various gaps in motivation, skills, and usage (van Dijk, 2006). The term itself then is “deeply ambiguous,” as it seemingly implies a singular divide between clearly distinguishable and fixed groups (van Dijk, 2006, p. 222). Research has documented the existence of multiple divides, and some scholars like van Dijk (2006) have argued for seeing them as dynamic in light of the ways technology is constantly changing. The “digital divide” is perhaps better thought of as a number of different divides (van Dijk, 2006) or instead as “digital inequality” (Wei & Hindman, 2011, p. 231).

Second, how to account for issues of “access” and “use” can pose problems for researchers. Wei and Hindman’s (2011) study provides an example of this. This study measured “access” to the Internet based on the yes/no question “Do you have Internet access at home?” (Wei & Hindman, 2011, p. 223). However, the home may not be the place, let alone the only place, people access the Internet. Some may only access the Internet at work, at friends’ or family’s houses, at cyber cafes and other public access points, or some combination of these. Should those individuals not count as having access? This raises questions of what qualifies as having access in terms of location, frequency, and quality of the connection and use. Also, as van Dijk (2006) points out, having access does not necessarily mean people are using it. In the context of access at home, it might be commandeered by particular individuals within the household, seen as inappropriate for others to use (for example, women in certain cultural contexts), or avoided by some based on their perceived lack of technological competence.

These issues present a variety of challenges for scholars interested in the so-called “digital divide.” They speak to the importance of avoiding simplistic measures or definitions of these terms, of not making assumptions about what constitutes meaningful access or use, and of asking people about their varied levels of access and use in ways that speak to their lived experiences with these new technologies.

References Van Dijk, J. a. G. M. (2006). Digital divide research, achievements and shortcomings. Poetics, 34(4-5), 221–235. doi:10.1016/j.poetic.2006.05.004

Wei, L., & Hindman, D. B. (2011). Does the digital divide matter more? Comparing the effects of new media and old media use on the education-based knowledge gap. Mass Communication and Society, 14(2), 216–235. doi:10.1080/15205431003642707

With several of the mass media theories that we have discussed in past weeks, it has seemed that the Internet and social media serve to flatten hierarchies and eliminate the middleman. For example, these new technologies may change or eliminate the two-step flow model and allow information to flow straight from the media to the general public, they may weaken the agenda-setting function of traditional mass media, and they may lessen the inherent power distance between the media and the public discussed in media systems dependency theory. However, when it comes to the knowledge gap hypothesis and the digital divide, the opposite seems to be true. Rather than equalizing and eliminating hierarchy, the Internet seems to only reinforce and strengthen disparities among different segments of the population.

The original knowledge gap hypothesis (Tichenor, Donohue, & Olien, 1970) states that as media coverage on an issue increases, the gap in knowledge increases between those with high and low socioeconomic status. Suggested reasons for this gap include the greater likelihood of those with high SES to attend to mass media, understand it in relationship to previously stored knowledge, and discuss it with similarly educated social contacts.

This hypothesis has been supported and refined by a number of subsequent studies. For example, Donohue, Tichenor, and Olien (1975) found that the knowledge gap is wider for national issues and smaller for issues of local importance, especially those that generate conflict within an entire community. In addition, Jerit, Barabas, and Bolsen (2006) found that the knowledge gap widens with increased publicity in newspapers (a medium catered toward more educated segments of the population), but does not significantly increase with increased publicity on television. This focus on different types of media is further complicated by the introduction of the Internet, which leads to what has been called the digital divide. While one might expect the Internet to decrease the knowledge gap by allowing for information to be easily and widely accessed, this has not been the case. In fact, Wei and Hindman (2011) found that the gap is actually wider for consumers of Internet media than for consumers of traditional media. Furthermore, this divide is not necessarily due to access to technology, but rather the different ways that different segments of the population use the Internet.

This is a rather interesting finding that casts doubt on many of the optimistic claims that have been made about the Internet, and suggests that the issue is far more complicated than was once thought. Clearly, the solution to the digital divide is not simply to increase access to technology. Instead, it seems important to educate potential Internet users to use the technology in effective ways, and to learn more about how people of lower socioeconomic status currently use the Internet. This might be an interesting new arena for uses and gratifications research. If we can understand more clearly what resources people are actually using on the Internet and why they are using them, it may be possible to improve these education processes, suggest more beneficial uses, and decrease the digital divide. However, there is no denying that this is a difficult issue with no clear solution.

Donohue, G. A., Tichenor, P. J., & Olien, C. N. (1975). Mass media and the knowledge gap: A hypothesis reconsidered. Communication Research, 2(1), 3-23.

Jerit, J., Barabas, J., & Bolsen, T. (2006). Citizens, knowledge, and the information environment. American Journal of Political Science, 50(2), 266-282.

The knowledge gap theory suggests that one’s socioeconomic status plays a significant role in determining one’s ability to acquire information and knowledge from the mass media. According to this theory, those who are better off in terms of their socio-economic standing in society are at a better position to acquire information and knowledge when information is disseminated by the mass media, than those of lesser socioeconomic standing thus, creating a knowledge gap between the different social strata in society.

Furthermore, it proposes that contrary to popular belief, as more information becomes readily available in society, through the proliferation of information by the mass media, the knowledge gap between higher and lesser socioeconomic groups does not decrease but in fact, increases significantly. Even more, those of higher socioeconomic standing absorb the higher level of distributed information by the mass media at a faster rate than those of a lesser status hence, further increasing the knowledge gap between the two different groups by ensuring that the less educated always benefit relatively less than the higher educated in society.

Therefore, the wider distribution of information by the mass media does not level the playing field for everyone in society but rather, serves to perpetuate the established socioeconomic differences between the different strata within a society. That is especially true, given that those with greater access to information, the higher strata, also possess a greater ability to absorb, understand and put that information to use for their own benefit such as, where to invest their money, or where to move for better job opportunities for example, than the lower strata in society, who apparently will always remain comparatively less informed and thus, always at a comparative disadvantage.

With the emergence of new information technologies like the Internet, smart phones, computers and digital television, a new form of gap emerged, a digital gap or a digital divide. According to Dijk (2006), the digital divide concept was initially used to refer to the gap between those who have access to new digital information technologies and those who do not. Again, under this digital gap theory, the socioeconomic standing acts as a contributing factor to the inequality of access between different groups within a society, or even between different countries, based largely on this factor’s ability to establish who can afford these new technologies and who cannot.

However, Dijk (2006) as well as Wei and Hindman (2011), suggest that the digital divide no longer denotes one’s ability to merely access the new forms of information technology, especially in terms of acquiring physical access to them, but it is now one that is associated with the gap that exists between those who possess the skills and the know-how to utilize this new information technology versus those who do not. Moreover, the socioeconomic status is still a major factor in that it shapes one’s ability possess the necessary skills to adequately use this new technology.

Additionally, Wei and Hindman (2011) suggest that the social economic status affects the type of content acquired on the Internet by different groups, with the higher status group typically gravitating towards information content that might benefit their lives or socioeconomic situation, and or adds to their existing knowledge base. Accordingly, the type of information each socioeconomic group is exposed to on the Internet differs, and is largely under the control of each group. Whereas, under traditional media both socioeconomic groups in general do not have control over the information disseminated by the media to them. As a result, the probability of equal exposure to the same information is higher for both groups under traditional media, than under new information technology yet, this probability of equal exposure to information by traditional media still results in a knowledge gap between the two different groups. As a consequence, Wei and Hindman (2011) propose that the Internet has the ability to increase the knowledge gap between the two different groups within society at a larger scale than traditional media does, specifically because each group is in control of what information to access through the Internet and how to utilize it.

So do these theories have any bearing on social media? Given that social media use is largely a personal choice, and given that different social media platforms allow users, with varying degrees, to largely determine the type of information they have access to through them, as well as, the type of networks they can establish within them, one could suggest that social media will only extend the differences in patterns of selective use between the different socio-economic groups, which according to Wei and Hindman (2011) above, has been exhibited by Internet use in general. As a result, one could presume that those of a higher education and status will also seek more informational content on social media than those of a lower status and education. Consequently, one could suggest that social media will only serve to compound the increase in the knowledge gap that arises between the different types of users based on their socioeconomic status. Also one could presume that much like the digital divide that arises form the different uses of new information technology or the physical access to new information technology, social media can create a digital divide between users and non-users of social media as well as, between different types of users of any one social media.

Moreover, according to Donahue and Olien (1970), there are a number of factors that help predict the emergence of a knowledge gap between different socioeconomic groups, and predict the increase of that gap as more information is distributed by the media these include, social contacts, previous information people are exposed to, their communication skills, their ability to self select and retain information and the type media that delivers the information to them. If applied to social media in terms of previously acquired information for example, one could suggest that, depending on the type of information being circulated, the proliferation of information within social media platforms might benefit those who are better educated and those who possess previous knowledge regarding a topic much more than those who are less educated and less familiar with the same topic. For example, if the topic being circulated within the social media platform is time sensitive and was related to a specific new policy, political event or even an economic development, those who are better educated and more knowledgeable are at a greater advantage than those who are less educated in terms of understanding, retaining and using the relevant information being circulated on social media to better their socioeconomic position or their lives.

Of course, depending on the type of social media in question, the type of information received through it will differ and the purpose behind using it will differ by the different socioeconomic groups. Therefore, the contribution of social media to the knowledge gap might increase or decrease depending on the purpose behind using it and the type of social media in question, and the ability of this social media to perpetuate socioeconomic differences will also depend on the type of use and information circulated within it.

To conclude, the knowledge gap theory proposes that there exists a knowledge gap between the socioeconomic groups within society, with those of a higher status and education benefitting more from the greater availability of information in the media than those of a lower status and lower education. This theory is highly pessimistic and even though it suggests, that under some exceptional circumstances the knowledge gap might diminish or even close such as when the media covers an issue that is of importance to a more homogenous community and a source of major conflict within it, it still proposes that generally, the knowledge gap will only keep expanding between the socioeconomic groups in society as more information becomes available through mass media. It also implies that with the emergence of new digital information technologies, that a digital gap between users has emerged and that the accompanying knowledge gap that arises from it will only keep expanding presumably at a faster rate than before with the acceleration of development of the digital information technology.

Very complete answer…

Knowledge gap theory claims there is a “gap” or break in how different sets of people benefit from the information available through various media. The theory generally postulates that people of a higher socioeconomic status (SES) accrue significantly more knowledge/benefits from the information they consume via media—and increase that knowledge at a faster rate—than those from a lower SES.

Tichenor, Donohue and Olien (1970) originally hypothesized that “over time, acquisition of knowledge of a heavily publicized topic will proceed at a faster rate among better educated persons than among those with less education.” In a later study, the same researchers found new contributing factors should be considered to understand the increase or decrease of a knowledge gap (Donohue, Tichenor, & Olien, 1975). The knowledge gap hypothesis should consider more than how the SES of media consumers contributes to a knowledge gap; the type of issue in question and the amount of conflict surrounding the issue can affect the knowledge gap, as well. For example, these researchers found that when an issue is of direct import to a community and there is conflict surrounding the issue, the knowledge gap is likely to decrease.

With the advent of new media, knowledge gap theory has evolved to accommodate the increasing importance of digital media. Now, research has begun to focus on the knowledge gap as a “digital divide.” Wei and Hindman (2011) contributed important findings to adapt knowledge gap theory to new media usage, examining the “digital divide” as observed in access to and use of the Internet. They tested the appropriateness of the conceptual shift from studying new media versus old media and use of media versus access to media. Wei and Hindman found that differing uses of new media create a greater knowledge gap than differing uses of traditional media, confirming the importance of knowledge gap research for new media. Their findings also supported the idea that a digital divide is more evident in the use of digital media, rather than the access to digital media. They found that SES has a stronger positive correlation with informational use of the Internet than with access to the Internet. These findings led Wei and Hindman to define the digital divide as “inequalities in the meaningful use of information and communication technologies” (p. 230).

The definition of digital divide given by Wei and Hindman (2011) provides an interesting twist on knowledge gap research, focusing on the use of the technology rather than the nature and relevance of the message or differing access to the information. This could be further explored in research examining the use of social media. Does an individual’s SES correlate with how he or she uses social media? Are people of a higher SES more likely to use social sites like Facebook and Twitter for informational purposes? Do differing uses of social media contribute to a knowledge gap increase, and do the newsfeed algorithms on social media sites enforce this gap?

Donohue, G. A., Tichenor, P. J., & Olien, C. N. (1975). Mass Media and the knowledge gap: A hypothesis reconsidered. Communication Research, 2(1), 3-23.

Tichenor, P. J., Donohue, G. A., & Olien, C. N. (1970). Mass media flow and differential growth in knowledge. Public opinion quarterly, 34(2), 159-170.

Wei, L., & Hindman, D. B. (2011). Does the digital divide matter more? Comparing the effects of new media and old media use on the education-based knowledge gap. Mass Communication and Society, 14(2), 216-235.

The Informational Underclass

I really enjoyed this week’s readings. Without being overtly political, they got to the heart of an issue that I felt existed since the beginning of the course, one that I didn’t quite know how to articulate. Primarily, this feeling had to do with power, politics, and other intangibles surrounding discussions of media, intangibles that can be said to exist before we even get to questions of “media” in the first place. The two main theories – the “digital divide” and “knowledge gap” – are useful for not only thinking through the way that media is disseminated unevenly but also for understanding the previously existing factors and conditions that can contribute to this uneven distribution in media and information. In this sense, I find that this unit speaks to some of the previous units in this course, particularly the one on social capital.

The knowledge gap hypothesis is interesting in that it posits that the mere presence of information or an increase in information does not automatically imply an understanding of what those information convey or entail. The theory posits that “because certain subsystems within any total social system have patterns of behavior and values conducive to change, gaps tend to appear between subgroups already experiencing change and those that are stagnant or slower in initiating change” (Tichenor et al, p. 159). In Tichenor, Donohue, and Olien’s classic 1970 study, the knowledge gap hypothesis was meant to “suggest itself as a fundamental explanation for the apparent failure of mass publicity to inform the public at large” (Tichenor et al, p. 160). While this acknowledged and explained the problem but did not yet produce an answer that was fully formed (in my opinion), their later study from 1975 posited inequality in education as the most salient factor contributing to knowledge gap and the “differential acquisition of information” (Donohue et al, p. 4). Along with education, media characteristics and interpersonal contact also played key roles, however education seemed to be the most important variable. The ties here to social capital theory are clear to me, and this is something I’d like to work on more in the future.

One line that really struck me was the first sentence from Jerit et al (2006): “Is there a permanent information underclass?” (266). Their conclusion was in line with the notion that “higher levels of political knowledge have been associated with an impressive range of outcomes,” including tolerance, participation, and assimilation (p. 278). Dijk (2006) supports the notion that more attention needs to be paid on “skills” and “usage” rather than on mere “access” (p. 229), and it is interesting to read this against Jerit et al (2006) in terms of what an “informed” citizen can do once they have acquired knowledge from the informational environment.

In terms of testing the digital divide and knowledge gap theories in an empirical setting, Wei and Hindman (2011) find that “socioeconomic status is more closely associated with the informational use of the Internet than with access to the Internet” (p. 216-217). These findings suggest that policies such as the “One Laptop per Child” project by Nicholas Negroponte are in a way misguided and not really answering the question of the digital divide. If the digital divide is in some ways predicated on a knowledge gap, simply providing access to computers will not help if there is not an attendant increase in education and instruction. In short, “mass media seem to have a function similar to that of other social institutions: that of reinforcing or increasing existing inequalities” (Tichenor et al, p. 170). In order to combat this, more attention to education and poverty might be a first priority.

Van Dijk, J. a. G. M. (2006). Digital divide research, achievements and shortcomings. Poetics, 34(4-5), 221–235. doi:10.1016/j.poetic.2006.05.004

Tichenor, Donohue, and Olien (1970) hypothesized that there is a knowledge gap between certain social subgroups, and “that growth of knowledge is relatively greater among the higher status segments” (p. 160). That is to say that they did not believe that any social subgroup was “completely uninformed” (p. 160), but that on general topics discussed and diffused by mass media were not being consumed by lower socioeconomic (or less educated) subgroups at the same rate as subgroups with higher socioeconomic (or more educated) levels.

While this particular article was published in the 1970s, some of their findings are still pertinent to information diffusion today. People belonging to lower socioeconomic groups by and large have less access to information produced mass communication materials such as newspapers, TV, Internet, and social media – or they choose to spend their time on other activities instead of looking for and consuming news and information (Van Dijk, 2006). I also have witnessed this phenomenon in my current research project with food pantry clients. While the project’s main focus is on their perception of meat, I included a section of questions in the interview aimed at discovering their media usages and information-seeking behaviors. One question is simply, “What media do you use?” I haven’t heard the same answer twice in the 35 interviews I’ve conducted thus far; but on the whole, only 8 subjects have answered that they use the Internet, and half of those have said they do not have Internet at home – they go to the library to access it.

The research I’ve done in this project seems to agree with Wei and Hindman’s (2011) description of the digital divide (modern-day knowledge gap) in its first-level, but contradicts their second-level gap that classifies the gap as one between access and use. My collected data is preliminary and I have not had time to fully analyze it yet; and, the sample subjects who I’m working with may be a part of a lower SES/educational subgroup than the general subgroups they refer to. However, I think the digital divide is still a question of access and use for lower socioeconomic, less educated, or even more rural subgroups in America, as well as countries all over the world.

Nevertheless, I would agree that in our developed country, no subgroup is completely in the dark about societal, environmental or political issues. But, the ways in which different subgroups gather information about these issues does matter and can contribute to a knowledge gap/digital divide. That’s why Van Dijk’s (2006) article particularly resonated with me this week, especially her Figure 1 on p. 224 that divides access into several parts, including motivational, material, skills and usage access. I concur with her that more research is needed, especially that of a qualitative nature, and that is focused on motivations for accessing and using digital and social media to help explore and explain the digital divide.

References Tichenor, P. J., Donohue, G. A., & Olien, C. N. (1970). Mass media flow and differential growth in knowledge. Public opinion quarterly, 34(2), 159-170.

Van Dijk, J. A. (2006). Digital divide research, achievements and shortcomings. Poetics, 34(4), 221-235.

Amanda, is this the comment you were talking about?

Yes…I think it was a problem with the browser on my laptop that wasn’t showing it as posted, just awaiting moderation. I’m glad you saw it & graded it – thanks!

The miracles and the wonders of the Internet do need to be called to stop and the Knowledge Gap hypothesis and the Digital Divide can perfectly answer the question concerning the Internet being a good thing or not. While enjoying the benefits and convenience enabled by the Internet, we need to pause for a second and reflect more upon how our own life is made different and how our life is made different from each other due to the use of the Internet.

In Tichenor, Donohue and Olien (1970), researchers have discussed the knowledge gap hypothesis based on the evidences from four different types of researches, the results of which all lends support to this hypothesis that the increasing flow of information on mass media leads to a widening knowledge gap among the social segments characterized by different educational levels. In the study, researchers conclude with the finding that mass media has the function “of reinforcing or increasing existing inequalities” (p. 170). The following study of Donohue, Tichenor and Olien (1975) takes a step further and expands the theory by involving the types of issue and the conflict dimensions of the issue within the community in the discussion loop. Both the two studies focus on the knowledge gap resulting from the information flow in traditional mass media.

To test the knowledge gap hypothesis in the new media environment, the inequalities and disparities between different social segments are even more obvious. The life cycle of information flowing on the Internet is so quick that it can either pass on or fade away very quickly, which in turn creates the information gap very quickly. One other prominent feature of the Internet can also add propelling force to the widening knowledge gap, which is the more diversified and customized information platform. To appeal to the specific needs of the users, the developing trend of the technology has attached great importance to the customized feature which is designed to meet the “unique” needs of the users. The more customized the technology is, the larger the knowledge gap is. With customization, people who have adequate information will keep being better informed while people who lack the information will keep being kept away from the information cycle. Coming from this concern, it is interesting to consider some other factors, apart from educational levels, which can also be closely associated with the Knowledge Gap.

In discussing the Digital Divide, Wei and Hindman (2011) focus more on the so called second-level of Digital Divide which is the actual usage of the Internet, rather than the material access to the Internet. While this second level is undoubtedly becoming a more visible phenomenon, the problem rooted in the first level—the physical access to the digital technologies still cannot be neglected. Part of the whole world is still facing the problems of lacking basic Information and Communication Technologies infrastructures. With this perspective focusing on the global world, the digital divide is incredibly speeding up the disparities between the people from different countries. As Donohue, Tichenor and Olien (1975) have pointed out, “the deprivation of knowledge may lead to relative deprivation of power” (p. 4). What actions can we take to empower the people and nations struggling at the bottom of the digital capabilities and bridging the knowledge gap between them and us?

References Donohue, G.A., Tichenor, P.J., & Olien, C. N. (1975). Mass Media and the Knowledge Gap: A Hypothesis Reconsidered. Communication Research, 2 (3), 3-23

Tichenor, P. J., Donohue, G. A., & Olien, C. N. (1970). Mass Media Flow and Differential Growth in Knowledge. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 34 (2), 159-179

Wei, L., & Hindman, D. B. (2011). Does the Digital Divide Matter More? Comparing the Effects of New Media and Old Media Use on the Education-Based Knowledge Gap. Mass Communication and Society, 14(2), 216-235

Tichenor, Donohue & Olien (1970) claim that “The knowledge gap hypothesis seems to suggest it self as a fundamental explanation for the apparent failure of mass publicity to inform the public at large” (Tichenor et al, 1970, 161). However, I would argue that the only thing the knowledge gap hypothesis suggests, is how certain classic perspectives, theories and frameworks has been rendered rather irrelevant by rapid changes in the communicative environment.

Central to their argument is five factors that drive the widening of knowledge gaps in correlation with increasing levels of media input. The general level of media input has increased dramatically since 1970, so there should be no doubt, that the knowledge gaps of today are bigger than ever. Except, they are not. In my opinion, this is because most of the five factors are not relevant as arguments in the Internet era.

The first factor is “communication skills”, which implies that people with more formal education have higher reading and comprehension abilities. Although this may be true, I would argue that the Internet lowers the communication skills required by the individual to obtain knowledge. CGP Grey ( https://www.youtube.com/user/CGPGrey ) makes educational videos that explain complex sociological, political and economic concepts in simple layman’s terms. Duolingo ( https://www.duolingo.com/ ) has made it easier than ever to learn foreign languages and Times for Kids ( http://www.timeforkids.com/news ) makes world news accessible for kids. Thus, by making information comprehensible for a wider audience, the Internet narrows the knowledge gap rather than widening it. Granted, Tichenor, Donohue & Olien focuses on public affairs and science knowledge, but even for these subject the above should be true (Tichenor et al, 1970).

Furthermore, I do not buy in on the argument that “stored information” renders people better prepared to understand a given topic. In our modern world, everything is but a Google search away. Therefore, the individual requires less stored information in order to understand a given subject. Context is effortlessly available, which makes it easy for the less educated to understand any topic. Neither “relevant social contact” is a factor that drives a widening of information gaps in the Internet era. Present day social media has made an infinite number of reference groups available for just about anyone. No matter the educational level, individuals have access to an abundance of interpersonal contacts on the Internet, which should make the likelihood of discussing public affairs likely for anyone that has that desire.

Also, “the nature of the mass media that delivers the information” could be questioned. If “science and public affairs news ordinarily lacks the constant repetition which facilitates learning and familiarity among lower status persons” (Tichenor et al, 1970) it would seem that the less educated are in luck in present day. Information is now being pushed through an abundance of different media that an individual might be exposed to throughout the day. Information does no longer come from just interpersonal contacts, radio, newspapers or TV. Newsletters, tweets, podcasts, RSS feeds, push notifications, text messages and social networks provide endless potential for repetition of important information.

However, all might not be lost for Tichenor, Donohue & Oliens hypothesis. The last factor, “selective exposure, acceptance, and retention of information” does seem to hold some relevance. This is because it connects with the findings of Wei & Hindmann (2011) who argue that in the Internet age it is not lack of accessibility, but quantity and quality of Internet use that drives information inequality. Further they conclude that the higher the socioeconomic status of an individual is, the higher is the informational use of the Internet for that person. The underlying argument is, that the more educated the person is, the better they harness the possibilities of the Internet (Wei & Hindmann, 2011).

Nonetheless, I refuse to abandon the idea of a narrowing knowledge gap in the era of the Internet. Yes, more well educated people might “use the internet better”, and there might very well be a knowledge gap, but the overall barriers to information have been, and continue to be, lowered. While there might be a widening gap between the very most and very least informed individuals, the general level of information in society has been heightened. Thus, we are better off in general, and the pessimistic tone of both Tichenor et al. (1970) and Wei & Hindmann (2011) has no right.

References Tiehenor, P. J., Donohue, G., & Olien, C. (1970). Mass Media Flow and Differential Growth in Knowledge. The Public Opinion Quarterly , 34 (2), 169-170.

Is two-step flow theory applicable to aid in understanding the knowledge gap hypothesis? Katz (2000) touches on this issue multiple times, especially in his “Media Multiplication and Social Segmentation” piece. He states that as media have evolved, they become more individualized and simultaneously globalized. Television started out with just a few channels nationwide, and now is considered a waning media with more cable channels than one can count. The internet has only magnified this individualization putting the focus on consumerism instead of on interpersonal and political frameworks. This poses a bit of an issue, considering social influence can be thought of in terms of diffusion among mass media and personal interactions (Katz, 2006)

The knowledge gap hypothesis describes the acquisition rate and breadth of knowledge will be greater for those with higher socioeconomic status than with lower (Tichenor et al., 1970). Indeed, one of the factors contributing to this difference is relevant social contact. Findings show that increased social integration of public issues shows an increased rate of diffusion of information. Similar to Katz, digital divide theory has found that the difference in knowledge is greater among the internet than with other traditional media (Wei & Hindman, 2011). This is in part a result in differences of Internet use, whether informational or accessible. Katz describes the cause of this divide as a disintegration of institutions (such as unions, political parties, and organizations) and replacement with individualism (Katz, 2000). Could it be possible that education could be thought of as an institution that has not dissolved as of yet? Could this be a possible answer for the growing divide of knowledge in socioeconomic groups?

Katz, E. (2000). Media multiplication and social segmentation. Departmental Papers (ASC), 161.

Katz, E. (2006). Rediscovering Gabriel Tarde∗. Political Communication, 23(3), 263-270.

Much like Andrew in the previous post, I have often pondered how the dissemination of information through media can affect the way that a user forms opinions about a specific topic or issue. This week’s readings for me were a peek into the world of social media distribution inequality and the knowledge gap that can often arise within differing social groups based on how that information is utilized to make informed decisions. Digital Divide theory is defined as an economic and social inequality that is rooted in the social categories of persons specific to populations, taking into account the access to, use of, and prior knowledge of information technologies (Weia & Hindman, 2011; Norris, 2001). The digital divide can be broken into two categories, the digital divide and the global digital divide.

In Global digital divide the theory states that while parts of the western world has developed the infrastructure to support the internet, much of the under developed world has not been able to put the amount of capital required into an infrastructure network to enable it to keep up in areas of technology, democracy, and labor markets. This is a problem that continues to grow as the economies of under developed nations continue to suffer from the global recession. In digital divide, it is stated that the divide may not be that a social group or individual does not have access to technology, but may have access to a lesser, or antiquated, technology. The focus here is on the ability to gain access to good computers, smart phones, and reliable internet connections. This is a problem that is faced in countries like the US, where the underprivileged and rural populations have a harder time gaining access to reliable internet and cannot afford good computers or technologically advanced mobile devices (Kim, 2003).

We have seen an increase in the use of social media in countries like Egypt and Libya, during the Arab Spring uprisings of 2011. Much of the information that was available to outsiders came through the use of personal digital devices by citizens of those countries. Up until that time, all of the media inside those countries borders was state sponsored and outsiders were only able to get the information that was afforded to them by sponsoring governments.

The digital divide was closed within its own borders, when individuals were given smart phones or able to purchase phones due to lower prices. The fall of the regimes that ruled these countries also allowed the throat hold on internet content to end. The ability of individuals to get out the message through social media and mass media outlets caused the global digital divide begin to close (Duffy, 2011).

Unfortunately, this has had a negative effect on the poorer populations of those countries. As Knowledge Gap Theory states, the more infusion of mass media content into a social system where the higher socioeconomic groups have faster and better access to this information, the larger the gap grows between the lower socioeconomic groups and higher socioeconomic groups (Tichenor, Donohue &Olien 1970). This is the bind that ties the two theories together in my mind and they are not mutually exclusive. While the digital divide and global digital divide may be shortened between social groups, differing social economic gaps can grow, because if you are monetarily challenged, unless the device and services are free, the ability to obtain the information that is placed out there is still very limited.

Duffy, M. J. (2011). “Smart phones in the Arab Spring: a revolution in gathering and reporting news”. http://www.academia.edu .

Kim, Y. J. (2003). “A theory of digital divide: Who gains and loses from technological changes?”. Journal of Economic Development 28 (1): 1-19.

Norris, P. (2001). Digital Divide: Civic Engagement, Information Poverty and the Internet Worldwide. Cambridge University Press.

Tichenor, P.A.; Donohue, G.A. & Olien, C.N. (1970). “Mass media flow and differential growth in knowledge”. Public Opinion Quarterly 34 (2): 159–170.

Wei, Lu, Hindman, D.B. (2011). “Does the Digital Divide Matter More? Comparing the Effects of New Media and Old Media Use on the Education-Based Knowledge Gap”. Mass Communication and Society 14 (2): 216-235.

Are knowledge gap and the digital divide theoretical framework the same thing, or are they two different things? If the later, what makes them different?

The knowledge gap hypothesis seems complementary to two-step flow. It helps to explain the formation of opinion leaders and followers and opens up avenues of research into how those formations could change in the future. Tichenor, Donohue, and Olien (1970) define the knowledge gap as the tendency for there to be a greater acquisition of knowledge among the more highly educated compared to the lower educated. They identify five factors that explain why this knowledge gap exists. They say of the third factor, relevant social contact, that “studies of diffusion among such groups as doctors and farmers tend to show steeper, more accelerated acceptance rates for more active, socially integrated individuals” (p.162). This reminded me of the drug study discussed by Katz (1957) where doctors who were more active socially were found to be the opinion leaders on the adoption of the new drug technology. The knowledge gap hypothesis goes further than stating who the opinion leaders are but also shows how they came to be the opinion leaders. They receive the information first thus giving them the opportunity to lead the discussion on a particular item and influence the followers. Jerit, Barabas, and Bolsen (2006) take this idea and see if it can be manipulated. They look specifically at political knowledge saying “political knowledge helps citizens…translate their opinions into meaningful forms of political participation” (p.266). They want to know if the knowledge gap can be reduced thus allowing more non-traditional opinion leaders to come forward. They found that print media increased the knowledge gap but television did not. This opens the way for other researchers to specifically target television as communication medium for the lower educated allowing them to gain more knowledge and thus more power within their political system. The potential is there for a more diverse range of opinion leaders to be heard in mainstream media than just those of high socioeconomic status.

References Jerit, J., Barabas, J., & Bolsen, T. (2006) Citizens, Knowledge, and the Information Environment. American Journal of Political Science, 50 (2), p. 266-282. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.ezproxy.lib.purdue.edu/doi/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00183.x/pdf . Katz, E. (1957) The Two-Step Flow of Communication: An Up-To-Date Report on an Hypothesis. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 21, p.61-78. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.lib.purdue.edu/stable/2746790 . Tichenor, P.J., Donohue, G.A., & Olien, C.N. (1970) Mass Media Flow and Differential Growth in Knowledge. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 34 (2), p. 159-170. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2747414 .

This is the type of “connect the dots” thinking that makes this class worth teaching…

Information inequality from digital divide is generally used to describe the discrepancy between people who have access to the Internet, a new communication tool, and people who do not have the access to the technology. The general concept of information inequality mainly deals with the problem whether people physically access to the information or not. However, the inequality from digital divide has a multi-faceted concept of access. Van Dijk (2006) suggests four types of barriers to access information through digital media; (a) lack of physical access, (b) lack of mental or motivational access, (c) lack of digital skills, and (d) lack of actual usage of digital media. According to Van Dijk (2006), access problems of digital technology gradually flow from the first two kinds of access to the last two kinds. The general concept of digital divide only refers to the first of four kinds of access. As more and more people have gone online, many researchers have reconsidered digital divide from ‘the first-level digital divide’ associated with lack of physical and motivational access to ‘the second level digital divide’ caused by lack of digital skills and actual use. When the problems of physical and motivational approach have been explained, the problems of structurally different skills and uses become more operative.

Next, I would like to talk about new questions of digital divide in the new ear of social media. With emerge of new technology of the Internet, which makes information flow go faster and better to the public, new problems from the second-level of digital divide have been focused. In the same way, with popular use of socially connected communications in social media, a new question about digital divide should be discussed. As mentioned early, digital inequality researchers have expanded from a divide based simply on computer ownership to a range of inequalities in access and actual use of various digital technologies. Researchers of the Internet digital divide has dealt with understanding how digital skills, social networks and other resources mediate use of digital information (Hargittai, 2007; Mossberger et al., 2003). Recently, some studies have dealt with the socioeconomic participation gap (Correa, 2010; Hargittai & Walejko, 2008) for content sharing among youth with social media sites (Hargittai, 2007). However, many studies mainly focused on the ‘consumption’ of digital contents, rather than the ‘creating’ of digital contents. Creating contents is one of most important features in social media use. Schradie (2011) suggests that as the number of user-generated contents increases through social media sites, new empirical questions about digital inequality emerge from different types of consumers of social media such as contents consumers and contents generators. This is possible because social network sites, like Facebook, YouTube and Twitter, enable users to participate in creating online contents, which leads to increasing digital divide between those who are able to interact more fully with the technology and those who are passively consuming the contents. The study found that a digital production gap exists among different socio economic status (SES) groups, resulting that digital inequality happens more importantly for contents production than contents consumption.

Correa, T. (2010). The participation divide among “online experts”. Journal of Computer‐Mediated Communication, 16(1), 71-92. Hargittai, E. (2007). Whose space? Differences among users and non‐users of social network sites. Journal of Computer‐Mediated Communication, 13(1), 276-297. Hargittai, E., & Walejko, G. (2008). The Participation Divide: Content creation and sharing in the digital age 1. Information, Community and Society, 11(2), 239-256. Mossberger, K., Mary, K. M. C. J. T., Tolbert, C. J., & Stansbury, M. (2003). Virtual inequality: Beyond the digital divide. Georgetown University Press. Schradie, J. (2011). The digital production gap: The digital divide and Web 2.0 collide. Poetics, 39(2), 145-168. Van Dijk, J. A. (2006). Digital divide research, achievements and shortcomings. Poetics, 34(4), 221-235.

According to knowledge gap assumption, more highly educated people can obtain greater knowledge from news media. Because highly educated people would have higher reading and comprehension abilities as well as existing knowledge. Thus, demographic and socioeconomic status (SES) have been prove as strongest predictor of knowledge gap (Tichenor, Donohue, & Olien, 1970). However, as Internet has become most influential media in the world, researchers proposed the assumption of digital divide should focus on actual use than material access (Wei & Hindman, 2011). And research results indicates SES is more related to Internet use than traditional media (newspaper and television) use as well as Internet access. Moreover, different internet use is correlated with a greater knowledge gap than different traditional media use (Wei & Hindman, 2011). In this sense, the emphasis of digital divide should not only be on how to measure that people access to communication technology, but on how to use information of internet of the digital age. However, in social media area, whether communication technology access or information use can be predictors of knowledge gap? According to The Pew Charitable Trusts, the research results demonstrate that African-Americans and Latinos tend to use their phones to access the internet more than white people. The implication of this result is that it shows that access to the internet, or use information of internet is not enough to measure people’s knowledge gap. Social media and communication technology enable people access internet and search information easily than ever. This change in focus raises several questions for knowledge gap generation. I think in social media area, existing knowledge, relevant social contact and selective exposure would be main predictors of people’s knowledge gap. Because existing knowledge and relevant social contact are associated with people’s SES, which makes people exposed to various information in their social network no matter online or offline. And selective exposure is correlated with how people personalize the internet and social media use, which would influence how people choose and gain knowledge. I think these 3 factors are still very important predictors of knowledge gap in social media age.

Wei, L., & Hindman, D. B. (2011). Does the digital divide matter more? Comparing the effects of new media and old media use on the education-based knowledge gap. Mass Communication and Society, 14(2), 216-235. Tichenor, P. J., Donohue, G. A., & Olien, C. N. (1970). Mass media flow and differential growth in knowledge. Public opinion quarterly, 34(2), 159-170.

Good day sir! I am Violy Romano, a third year student from Mindanao University of Science and Technology in Cagayan de Oro city, Philippines. I am currently taking Bachelor of Science in Technology Communication Management.

In this semester sir, we have a subject theories of communication and each one of us has to report the assigned theory. Moreover, I am assigned to report the Knowledge Gap theory and I searched it through google about the theory but there is a part of it which I did not understand. I want to know more about the knowledge gap theory graph that is being shown in your blog sir. I hope I may get to understand more about this theory sir so that I can discuss it to the class very well and my classmates would understand.

I am hoping for your favorable response.

Sincerely Yours, Violy Romano

The old graph was there for illustration purposes alone. I added a new one, which is more descriptive. See the caption. If you have questions, feel free to post here again…

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Currently you have JavaScript disabled. In order to post comments, please make sure JavaScript and Cookies are enabled, and reload the page. Click here for instructions on how to enable JavaScript in your browser.

- Research Process

What is a Research Gap

- 3 minute read

- 285.7K views

Table of Contents

If you are a young researcher, or even still finishing your studies, you’ll probably notice that your academic environment revolves around certain research topics, probably linked to your department or to the interest of your mentor and direct colleagues. For example, if your department is currently doing research in nanotechnology applied to medicine, it is only natural that you feel compelled to follow this line of research. Hopefully, it’s something you feel familiar with and interested in – although you might take your own twists and turns along your career.

Many scientists end up continuing their academic legacy during their professional careers, writing about their own practical experiences in the field and adapting classic methodologies to a present context. However, each and every researcher dreams about being a pioneer in a subject one day, by discovering a topic that hasn’t been approached before by any other scientist. This is a research gap.

Research gaps are particularly useful for the advance of science, in general. Finding a research gap and having the means to develop a complete and sustained study on it can be very rewarding for the scientist (or team of scientists), not to mention how its new findings can positively impact our whole society.

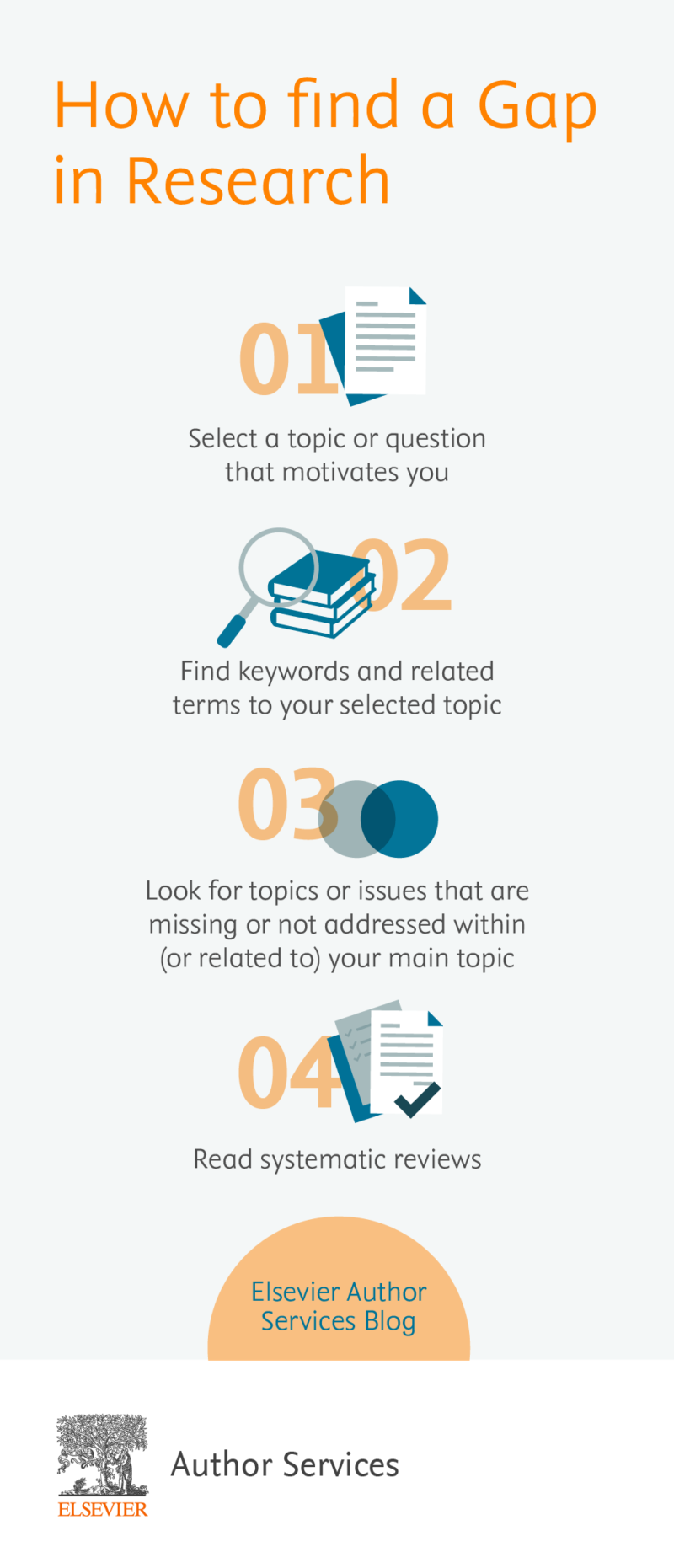

How to Find a Gap in Research

How many times have you felt that you have finally formulated THAT new and exciting question, only to find out later that it had been addressed before? Probably more times than you can count.

There are some steps you can take to help identify research gaps, since it is impossible to go through all the information and research available nowadays:

- Select a topic or question that motivates you: Research can take a long time and surely a large amount of physical, intellectual and emotional effort, therefore choose a topic that can keep you motivated throughout the process.

- Find keywords and related terms to your selected topic: Besides synthesizing the topic to its essential core, this will help you in the next step.

- Use the identified keywords to search literature: From your findings in the above step, identify relevant publications and cited literature in those publications.

- Look for topics or issues that are missing or not addressed within (or related to) your main topic.

- Read systematic reviews: These documents plunge deeply into scholarly literature and identify trends and paradigm shifts in fields of study. Sometimes they reveal areas or topics that need more attention from researchers and scientists.

Keeping track of all the new literature being published every day is an impossible mission. Remember that there is technology to make your daily tasks easier, and reviewing literature can be one of them. Some online databases offer up-to-date publication lists with quite effective search features:

- Elsevier’s Scope

- Google Scholar