Unilever Change Management Case Study

In today’s fast-paced business environment, change is inevitable.

Companies need to evolve and adapt to remain competitive, but managing change is not an easy task. Effective change management is crucial to the success of any organizational transformation, as it ensures that the changes are implemented smoothly and effectively.

In this blog post, we will examine a case study of change management at Unilever, one of the world’s largest consumer goods companies.

We will explore the challenges faced by Unilever, the change management approach it took, and the results of its initiatives.

Brief History and Growth of Unilever

Unilever is a British-Dutch multinational consumer goods company that was founded in 1929 through a merger between Dutch margarine producer Margarine Unie and British soap maker Lever Brothers.

Unilever has a long history of growth through mergers and acquisitions, with notable acquisitions including Bestfoods, Ben & Jerry’s, and Dollar Shave Club.

The company operates in over 190 countries and has a diverse portfolio of products, including food and beverages, cleaning agents, beauty and personal care products.

Unilever has also been committed to sustainability and social responsibility, and in 2010, it launched the Unilever Sustainable Living Plan, which aims to reduce the company’s environmental impact and improve the health and well-being of its customers.

Today, Unilever is one of the world’s largest consumer goods companies, with a revenue of over €50 billion in 2020.

External factors that led to organizational changes at Unilever

Unilever is a multinational consumer goods company that has undergone several organizational changes over the years. Here are three external factors that led to organizational changes at Unilever:

- Changing Consumer Preferences: The changing preferences and behaviors of consumers can have a significant impact on a company’s strategy and operations. For example, as more consumers started to prioritize eco-friendliness and sustainability, Unilever had to shift its focus towards more sustainable products and packaging. This led to the introduction of products like the “Dove Refillable Deodorant” and “Omo EcoActive” laundry detergent, as well as a commitment to reduce its plastic packaging by half by 2025.

- Competitive Pressure: Competition is another external factor that can force companies to make organizational changes. For example, when Unilever faced increasing competition from other consumer goods companies in emerging markets like India and China, it had to restructure its operations to be more efficient and cost-effective. This led to the consolidation of its global supply chain, as well as a greater emphasis on localizing its products and marketing strategies to better appeal to these markets.

- Technological Advancements: Advances in technology can also lead to organizational changes, as companies need to adapt to new ways of doing business. For example, as more consumers started to shop online, Unilever had to develop a strong e-commerce presence and optimize its digital marketing efforts. This led to the creation of Unilever Digital, a team dedicated to digital marketing and e-commerce, as well as a partnership with Alibaba to expand its online distribution in China.

Internal factors that led to organizational changes at Unilever

In addition to external factors, internal factors can also lead to organizational changes at Unilever. Here are three examples of internal factors that have led to organizational changes at the company:

- Management Changes: Changes in top management can often lead to organizational changes. For example, when Paul Polman became CEO of Unilever in 2009, he initiated a major restructuring of the company that aimed to streamline operations and focus on sustainable growth. This led to the consolidation of Unilever’s foods and personal care divisions, as well as a greater focus on emerging markets and sustainability.

- Financial Performance: Poor financial performance can also prompt organizational changes. For example, in 2017, Unilever reported slower-than-expected sales growth, leading the company to undertake a strategic review of its operations. This resulted in a decision to sell or spin off Unilever’s spreads business and focus on higher-growth areas like beauty and personal care.

- Organizational Culture: Organizational culture can also drive organizational change. For example, when Unilever identified a need to become more agile and innovative, it undertook a major cultural transformation initiative called “Connected 4 Growth.” This involved restructuring the company into smaller, more autonomous business units and giving employees greater freedom to experiment and take risks. The initiative aimed to foster a more entrepreneurial culture within the company and enable faster decision-making and innovation.

05 biggest steps taken by Unilever to implement changes

Unilever is a multinational consumer goods company that has undergone several organizational changes over the years. Here are the five biggest steps taken by Unilever to implement changes:

1. Sustainable Living Plan

In 2010, Unilever launched its Sustainable Living Plan, a comprehensive sustainability strategy that aimed to reduce the company’s environmental footprint, improve social impact, and drive profitable growth. The plan set ambitious targets for Unilever to achieve by 2020, such as reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 50% and improving the livelihoods of millions of people in its supply chain. The Sustainable Living Plan has been a driving force behind many of Unilever’s organizational changes, such as the introduction of sustainable products and packaging and a greater emphasis on transparency and accountability.

2. Organizational Restructuring

Unilever has undertaken several major organizational restructuring initiatives over the years to streamline its operations and focus on high-growth areas. For example, in 2016, Unilever announced a plan to consolidate its foods and personal care businesses into a single division, with the goal of achieving greater efficiency and cost savings. Similarly, in 2017, Unilever announced a strategic review of its operations in response to slower-than-expected sales growth, resulting in a decision to sell or spin off its spreads business and focus on higher-growth areas like beauty and personal care.

3. Digital Transformation

As more consumers started to shop online, Unilever recognized the need to invest in its digital capabilities to stay competitive. In 2017, the company launched Unilever Digital, a team dedicated to digital marketing and e-commerce, and entered into a partnership with Alibaba to expand its online distribution in China. Unilever also invested in technology startups and acquired several digital companies to enhance its digital capabilities and drive innovation.

4. Cultural Transformation

Unilever recognized that its organizational culture needed to change to foster greater agility and innovation. In 2016, the company launched its “Connected 4 Growth” initiative, which involved restructuring the company into smaller, more autonomous business units and empowering employees to take more risks and experiment. The initiative aimed to create a more entrepreneurial culture within the company and enable faster decision-making and innovation.

5. Portfolio Transformation

Unilever has undergone several portfolio transformations over the years to focus on its core brands and divest non-core businesses. For example, in 2018, Unilever acquired the personal care and home care brands of Quala, a Latin American consumer goods company, to strengthen its presence in emerging markets. At the same time, the company divested its spreads business and announced plans to exit its tea business to focus on higher-growth areas. These portfolio transformations have helped Unilever to stay agile and adapt to changing market conditions.

05 Results of change management implemented at Unilever

The change management initiatives implemented at Unilever have had several positive outcomes and impacts. Here are some of the key examples:

- Increased Sustainability: The Sustainable Living Plan has been a key driver of Unilever’s sustainability efforts, and the company has made significant progress in reducing its environmental footprint and improving social impact. For example, by 2020, Unilever had achieved its target of sending zero non-hazardous waste to landfill from its factories, and had also reduced its greenhouse gas emissions by 46% per tonne of production.

- Improved Financial Performance: Unilever’s focus on portfolio transformation and strategic acquisitions has helped the company to improve its financial performance. For example, in 2020, the company reported a 1.9% increase in underlying sales growth and a 2.4% increase in operating profit margin.

- Enhanced Digital Capabilities: Unilever’s investments in digital transformation have enabled the company to stay competitive in a rapidly evolving digital landscape. For example, Unilever’s partnership with Alibaba has helped the company to expand its online distribution in China, while its investments in technology startups have helped to drive innovation and enhance its digital capabilities.

- Improved Organizational Agility: Unilever’s organizational restructuring and cultural transformation initiatives have helped to create a more agile and entrepreneurial company culture. This has enabled Unilever to make faster decisions and respond more quickly to changing market conditions.

- Increased Customer Satisfaction: Unilever’s focus on innovation and product development has resulted in the launch of several successful new products and brands, such as the plant-based meat alternative brand, The Vegetarian Butcher. These products have helped to increase customer satisfaction and drive growth for the company.

Final Words

Unilever’s successful implementation of change management is a testament to the company’s commitment to innovation, sustainability, and organizational excellence. By undertaking a variety of initiatives, such as the Sustainable Living Plan, organizational restructuring, digital transformation, cultural transformation, and portfolio transformation, Unilever has been able to adapt to changing market conditions and position itself for long-term success.

One key factor in Unilever’s success has been its ability to align its change management initiatives with its overall business strategy. By focusing on high-growth areas, investing in sustainability, and enhancing its digital capabilities, Unilever has been able to drive growth and improve profitability while also achieving its sustainability goals.

Another key factor has been Unilever’s emphasis on collaboration and stakeholder engagement. By working closely with suppliers, customers, and other stakeholders, Unilever has been able to create a shared sense of purpose and drive greater alignment around its sustainability and innovation goals.

About The Author

Tahir Abbas

Related posts.

5 Types of Organizational Change

Advantages and Disadvantages of Crowdsourcing

The Promising Potential of Nudge Theory in Healthcare

Unilever—A Case Study

This article considers key issues relating to the organization and performance of large multinational firms in the post-Second World War period. Although foreign direct investment is defined by ownership and control, in practice the nature of that "control" is far from straightforward. The issue of control is examined, as is the related question of the "stickiness" of knowledge within large international firms. The discussion draws on a case study of the Anglo-Dutch consumer goods manufacturer Unilever, which has been one of the largest direct investors in the United States in the twentieth century. After 1945 Unilever's once successful business in the United States began to decline, yet the parent company maintained an arms-length relationship with its U.S. affiliates, refusing to intervene in their management. Although Unilever "owned" large U.S. businesses, the question of whether it "controlled" them was more debatable.

Some of the central issues related to the organization and performance of multinationals after the Second World War can be illustrated by studying the case of Unilever in the United States. Since Unilever's creation in 1929 by a merger of British and Dutch soap and margarine companies, 1 it has ranked as one of Europe's, and the world's, largest consumer-goods companies. Its sales of $45,679 million in 2000 ranked it fifty-fourth by revenues in the Fortune 500 list of largest companies for that year.

A Complex Organization

Unilever was an organizational curiosity in that, since 1929, it has been headed by two separate British and Dutch companies—Unilever Ltd. (PLC after 1981), and Unilever N.V.—with different sets of shareholders but identical boards of directors. An "Equalization Agreement" provided that the two companies should at all times pay dividends of equivalent value in sterling and guilders. There were two head offices—in London and Rotterdam—and two chairmen. Until 1996 the "chief executive" role was performed by a three-person Special Committee consisting of the two chairmen and one other director.

Beneath the two parent companies a large number of operating companies were active in individual countries. They had many names, often reflecting predecessor firms or companies that had been acquired. Among them were Lever; Van den Bergh & Jurgens; Gibbs; Batchelors; Langnese; and Sunlicht. The name "Unilever" was not used in operating companies or in brand names. Lever Brothers and T. J. Lipton were the two postwar U.S. affiliates. These national operating companies were allocated to either Ltd./PLC or N.V. for historical or other reasons. Lever Brothers was transferred to N.V. in 1937, and until 1987 (when PLC was given a 25 percent shareholding) Unilever's business in the United States was wholly owned by N.V. Unilever's business, and, as a result, counted as part of Dutch foreign direct investment (FDI) in the country. Unilever and its Anglo-Dutch twin Royal Dutch Shell formed major elements in the historically large Dutch FDI in the United States. 2 However, the fact that all dividends were remitted to N.V. in the Netherlands did not mean that the head office in Rotterdam exclusively managed the U.S. affiliates. The Special Committee had both Dutch and British members, and directors and functional departments were based in both countries and had managerial responsibilities without regard for the formality of N.V. or Ltd./PLC ownership. Thus, while ownership lay in the Netherlands, managerial control was Anglo-Dutch.

The organizational complexity was compounded by Unilever's wide portfolio of products and by the changes in these products over time. Edible fats, such as margarine, and soap and detergents were the historical origins of Unilever's business, but decades of diversification resulted in other activities. By the 1950s, Unilever manufactured convenience foods, such as frozen foods and soup, ice cream, meat products, and tea and other drinks. It manufactured personal care products, including toothpaste, shampoo, hairsprays, and deodorants. The oils and fats business also led Unilever into specialty chemicals and animal feeds. In Europe, its food business spanned all stages of the industry, from fishing fleets to retail shops. Among its range of ancillary services were shipping, paper, packaging, plastics, and advertising and market research. Unilever also owned a trading company, called the United Africa Company, which began by importing and exporting into West Africa but, beginning in the 1950s, turned to investing heavily in local manufacturing, especially brewing and textiles. The United Africa Company employed around 70,000 people in the 1970s and was the largest modern business enterprise in West Africa. 3 Unilever's total employment was over 350,000 in the mid-1970s, or around seven times larger than that of Procter & Gamble (hereafter P&G), its main rival in the U.S. detergent and toothpaste markets.

A World-wide Investor

An early multinational investor, by the postwar decades Unilever possessed extensive manufacturing and trading businesses throughout Europe, North and South America, Africa, Asia, and Australia. Unilever was one of the oldest and largest foreign multinationals in the United States. William Lever, founder of the British predecessor of Unilever, first visited the United States in 1888 and by the turn of the century had three manufacturing plants in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Philadelphia, and Vicksburg, Mississippi. 4 The subsequent growth of the business, which was by no means linear, will be reviewed below, but it was always one of the largest foreign investors in the United States. In 1981, a ranking by sales revenues in Forbes put it in twelfth place. 5

Unilever's longevity as an inward investor provides an opportunity to explore in depth a puzzle about inward FDI in the United States. For a number of reasons, including its size, resources, free-market economy, and proclivity toward trade protectionism, the United States has always been a major host economy for foreign firms. It has certainly been the world's largest host since the 1970s, and probably was before 1914 also. 6 Given that most theories of the multinational enterprise suggest that foreign firms possess an "advantage" when they invest in a foreign market, it might be expected that they would earn higher returns than their domestic competitors. 7 This seems to be the general case, but perhaps not for the United States. Considerable anecdotal evidence exists that many foreign firms have experienced significant and sustained problems in the United States, though it is also possible to counter such reports with case studies of sustained success. 8

During the 1990s a series of aggregate studies using tax and other data pointed toward foreign firms earning lower financial returns than their domestic equivalents in the United States. 9 One explanation for this phenomenon might be transfer pricing, but this has proved hard to verify empirically. The industry mix is another possibility, but recent studies have suggested this is not a major factor. More significant influences appear to be market share position—in general, as a foreign owned firm's market share rose, the gap between its return on assets and those for United States—owned companies decreased—and age of the affiliate, with the return on assets of foreign firms rising with their degree of newness. 10 Related to the age effect, there is also the strong, but difficult to quantify, possibility that foreign firms experienced management problems because of idiosyncratic features of the U.S. economy, including not only its size but also the regulatory system and "business culture." The case of Unilever is instructive in investigating these matters, including the issue of whether managing in the United States was particularly hard, even for a company with experience in managing large-scale businesses in some of the world's more challenging political, economic, and financial locations, like Brazil, India, Nigeria, and Turkey.

The story of Unilever in the United States provides rich new empirical evidence on critical issues relating to the functioning of multinationals and their impact. — Geoffrey Jones

Finally, the story of Unilever in the United States provides rich new empirical evidence on critical issues relating to the functioning of multinationals and their impact. It raises the issue of what is meant by "control" within multinationals. Management and control are at the heart of definitions of multinationals and foreign direct investment (as opposed to portfolio investment), yet these are by no means straightforward concepts. A great deal of the theory of multinationals relates to the benefits—or otherwise—of controlling transactions within a firm rather than using market arrangements. In turn, transaction-cost theory postulates that intangibles like knowledge and information can often be transferred more efficiently and effectively within a firm than between independent firms. There are several reasons for this, including the fact that much knowledge is tacit. Indeed, it is well established that sharing technology and communicating knowledge within a firm are neither easy nor costless, though there have not been many empirical studies of such intrafirm transfers. 11 Orjan Sövell and Udo Zander have recently gone so far as to claim that multinationals are "not particularly well equipped to continuously transfer technological knowledge across national borders" and that their "contribution to the international diffusion of knowledge transfers has been overestimated. 12 This study of Unilever in the United States provides compelling new evidence on this issue.

Lever Brothers In The United States: Building And Losing Competitive Advantage

Lever Brothers, Unilever's first and major affiliate, was remarkably successful in interwar America. After a slow start, especially because of "the obstinate refusal of the American housewife to appreciate Sunlight Soap," Lever's main soap brand in the United Kingdom, the Lever Brothers business in the United States began to grow rapidly under a new president, Francis A. Countway, an American appointed in 1912. 13 Sales rose from $843,466 in 1913, to $12.5 million in 1920, to $18.9 million in 1925. Lever was the first to alert American consumers to the menace of "BO," "Undie Odor," and "Dishpan Hands," and to market the cures in the form of Lifebuoy and Lux Flakes. By the end of the 1930s sales exceeded $90 million, and in 1946 they reached $150 million.

By the interwar years soap had a firmly oligopolistic market structure in the United States. It formed part of the consumer chemicals industry, which sold branded and packaged goods supported by heavy advertising expenditure. In soap, there were also substantial throughput economies, which encouraged concentration. P&G was, to apply Alfred D. Chandler's terminology, "the first mover"; among the main followers were Colgate and Palmolive-Peet, which merged in 1928. Neither P&G nor Colgate Palmolive diversified greatly beyond soap, though P&G's research took it into cooking oils before 1914 and into shampoos in the 1930s. Lever made up the third member of the oligopoly. The three firms together controlled about 80 percent of the U.S. soap market in the 1930s. 14 By the interwar years, this oligopolistic rivalry was extended overseas. Colgate was an active foreign investor, while in 1930 P&G—previously confined to the United States and Canada—acquired a British soap business, which it proceeded to expand, seriously eroding Unilever's market share. 15

The soap and related markets in the United States had a number of characteristics. Although P&G had established a preponderant market share, shares were strongly contested. Entry, other than by acquisition, was already not really an option by the interwar years, so competition took the form of fierce rivalry between incumbent firms with a long experience of one another. During the 1920s and the first half of the 1930s, Lever made substantial progress against P&G. Lever's sales in the United States as a percentage of P&G's sales rose from 14.8 percent between 1924 and 1926 to reach almost 50 percent in 1933. In 1930 P&G suggested purchasing Lever in the United States as part of a world division of markets, but the offer was declined. 16 Lever's success peaked in the early 1930s. Using published figures, Lever estimated its profit as a percentage of capital employed at 26 percent between 1930 and 1932, compared with P&G's 12 percent.

Countway's greatest contribution was in marketing. During the war, Countway put Lever's resources behind Lux soapflakes, promoted as a fine soap that would not damage delicate fabrics just at a time when women's wear was shifting from cotton and lisle to silk and fine fabrics. The campaign featured a variety of tactics, including washing demonstrations at department stores. In 1919 Countway launched Rinso soap powder, coinciding with the advent of the washing machine. In the same year, Lever's agreement with a New York agent to sell its soap everywhere beyond New England was abandoned and a new sales organization was established. Finally, in the mid-1920s, Countway launched, against the advice of the British parent company, a white soap, called "Lux Toilet Soap." J. Walter Thompson was hired to develop a marketing and advertising campaign stressing the glamour of the new product, with very successful results. 17 Lever's share of the U.S. soap market rose from around 2 percent in the early 1920s to 8.5 percent in 1932. 18 Brands were built up by spending heavily on advertising. As a percentage of sales, advertising averaged 25 percent between 1921 and 1933, thereby funding a series of noteworthy campaigns conceived by J. Walter Thompson. This rate of spending was made possible by the low price of oils and fats in the decade and by plowing back profits rather than remitting great dividends. By 1929 Unilever had received $12.2 million from its U.S. business since the time of its start, but thereafter the company reaped benefits, for between 1930 and 1950 cumulative dividends were $50 million. 19

Many foreign firms have experienced significant and sustained problems in the United States. — Geoffrey Jones

After 1933 Lever encountered tougher competition in soap from P&G, though Lever's share of the total U.S. soap market grew to 11 percent in 1938. P&G launched a line of synthetic detergents, including Dreft, in 1933, and came out with Drene, a liquid shampoo, in 1934 both were more effective than solid soap in areas of hard water. However, such products had "teething problems," and their impact on the U.S. market was limited until the war. Countway challenged P&G in another area by entering branded shortening in 1936 with Spry. This also was launched with a massive marketing campaign to attack P&G's Crisco shortening, which had been on sale since 1912. 20 The attack began with a nationwide giveaway of one-pound cans, and the result was "impressive." 21 By 1939 Spry's sales had reached 75 percent of Crisco's, but the resulting price war meant that Lever made no profit on the product until 1941. Lever's sales in general reached as high as 43 percent of P&G's during the early 1940s, and the company further diversified with the purchase of the toothpaste company Pepsodent in 1944. Expansion into margarine followed with the purchase of a Chicago firm in 1948.

The postwar years proved very disappointing for Lever Brothers, for a number of partly related reasons. Countway, on his retirement in 1946, was replaced by the president of Pepsodent, the thirty-four-year-old Charles Luckman, who was credited with the "discovery" of Bob Hope in 1937 when the comedian was used for an advertisement. Countway was a classic "one man band," whose skills in marketing were not matched by much interest in organization building. He never gave much thought to succession, but he liked Luckman. 22 This proved a misjudgment. With his appointment by President Truman to head a food program in Europe at the same time, Luckman became preoccupied with matters outside Lever for a significant portion of his term, though perhaps not to a sufficient degree. Convinced that Lever's management was too old and inbred, he dismissed about 15 percent of the work force soon after taking office, and he completed the transformation by moving the head office from Boston to New York, taking only around one-tenth of the existing executives with him. 23 The head office, constructed in Cambridge by Lever in 1938, was subsequently acquired by MIT and became the Sloan Building.

Luckman's move, which was supported by a firm of management consultants, the Fry Organization of Business Management Experts, was justified on the grounds that the building in Cambridge was not large enough, that it would be easier to find the right personnel in New York, and that Lever would benefit by being closer to the large advertising agencies in the city. 24 There were also rumors that Luckman, who was Jewish, was uncomfortable with what he perceived as widespread anti-Semitism in Boston at that time. The cost of building the New York Park Avenue headquarters, which became established as a "classic" of the new postwar skyscraper, rose steadily from $3.5 million to $6 million. Luckman had trained as an architect at the University of Illinois, and he was very involved in the design of the pioneering New York office.

- 09 May 2024

- Research & Ideas

Called Back to the Office? How You Benefit from Ideas You Didn't Know You Were Missing

- 06 May 2024

The Critical Minutes After a Virtual Meeting That Can Build Up or Tear Down Teams

- 01 May 2024

- What Do You Think?

Have You Had Enough?

- 13 May 2024

Picture This: Why Online Image Searches Drive Purchases

- 24 Jan 2024

Why Boeing’s Problems with the 737 MAX Began More Than 25 Years Ago

- Globalization

- Consumer Products

- Entertainment and Recreation

- Food and Beverage

- Manufacturing

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Our use of cookies

We use necessary cookies to make our site work. We’d also like to set optional analytics cookies to help us improve it. We won’t set optional cookies unless you enable them. Using this tool will set a cookie on your device to remember your preferences.

For more detailed information about the cookies we use, see our Cookie policy

Necessary cookies

Necessary cookies enable core functionality such as security, network management, compliance and accessibility. You may disable these by changing your browser settings, but this may affect how the website functions.

Analytics cookies

We’d like to set Google Analytics cookies to help us to improve our website by collecting and reporting information on how you use it. The cookies collect information in a way that does not directly identify anyone.

Enable analytics cookies :

- Online A4S Summit 2024

- Governance and Advisory

- Where we work

- CFO Leadership Network

- Accounting Bodies Network

- Circles of Practice

- Asset Owners Network

- The A4S Controllers Forum

- Media centre

- Media library

- Why sustainability and finance?

- Who we work with

- CFOs and their finance teams

- The global accounting community

- The global financial community

- Governments and regulators

- Business schools and academia

Current activities

- Essential Guides

- Briefings for finance

- A4S response to ISSB consultation on agenda priorities

- Business and finance community respond to the proposed IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards

- A4S response to the proposed IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards

- Sustainability Reporting Workshop Series (ESRS)

- Net Zero Guidance

- Net Zero Practical Examples

- Transition Planning

- Four actions finance teams can take on nature

- Supporting the TNFD Recommendations

- TCFD Guidance

- TCFD Insight Series

- TCFD Statement of Support

- The ESG toolkit for pension chairs and trustees

- Embracing Sustainability: Actions for SMEs

- A4S International Case Competition

- Finance for the Future Awards

- Knowledge hub

- Canadian Chapter of the CFO Leadership Network

- CFO Leadership Network Europe

- US Chapter of the CFO Leadership Network

- Asia Pacific Chapter of the CFO Leadership Network

- CALL TO ACTION IN RESPONSE TO CLIMATE CHANGE

- IASB Statement of Support

- Transforming the profession – the future of accountancy

- Asset Owners Network current activities

- Asset Owners Network Members

- A Sustainability Principles Charter for the bulk annuity process

- TNFD Top Tips

Unilever: Strategic Planning, Budgeting and Forecasting

Business goals that will enhance long-term stakeholder value.

In 2012 we set our four strategic goals to be:

• Grow the Business: By 2020 our goal is to double sales by the business compared to 2010

• Improve Health and Wellbeing: By 2020 we will help more than a billion people take action to improve their health and wellbeing

• Reduce Environmental Impact: By 2030 our goal is to halve the environmental footprint from making and using of our products as we grow our business

• Enhance Livelihoods: By 2020 we will enhance the livelihoods of millions of people as we grow our business

Defining our purpose and our vision were key to setting our strategic goals. We believe profitable growth should also be responsible growth. That approach lies at the heart of the development of our strategic goals.

In developing our goals there were a number of priorities that were important to us:

• Customer and consumer trust

• A strong business for shareholders

• A better, healthier and more confident future for children

• A better future for the planet

• A better future for farming and farmers

We developed our goals as a path towards achieving our vision, incorporating these priorities through a process of actively engaging with governments, intergovernmental organizations, regulators, customers, suppliers, investors, civil society organizations, academics and our consumers. The detail on how we intend to deliver our goals is captured in the Unilever Sustainable Living Plan. It guides our approach to how we do business and how we meet the growing consumer demand for brands that act responsibly in a world of finite resources. Our Plan is distinctive in three ways:

1. It spans our entire portfolio of brands and all countries in which we sell our products.

2. It has a social and economic dimension: our products make a difference to health and wellbeing and our business supports the livelihoods of many people.

3. When it comes to the environment, we work across the whole value chain, from the sourcing of raw materials, to our factories and the way consumers use our products.

At Unilever, we have a simple but clear purpose – to make sustainable living commonplace. We believe this is the best long term way for our business to grow. Our purpose and operating expertise will help us to realize our vision of accelerating growth, reducing our environmental footprint and increasing our positive social impact. We recognize this is ambitious, but it is consistent with changing consumer attitudes and expectations. Our unswerving commitment to sustainable living is increasingly delivering:

• more trust from customers; and

• a strong business for shareholders, with lower risks and consistent, competitive and profitable long term growth.

DOWNLOAD THE FULL GUIDE

This Unilever case study has been taken from the A4S Essential Guide to Strategic Planning, Budgeting and Forecasting.

Further case study

Yorkshire Water's case study on identifying long term risks and opportunities

ABOUT OUR ESSENTIAL GUIDE SERIES

To find out more about our Essential Guide series and see other guidance follow this link.

Accounting for Sustainability is a Charitable Incorporated Organization, registered charity number 1195467. Accounting for Sustainability is part of the King Charles III Charitable Fund Group of Charities. Registered Office: 9 Appold Street, 8th Floor, London, EC2A 2AP

How Unilever Went From Soap Manufacturer To Multinational Giant

Table of contents, here’s what you’ll learn from unilever’s strategy study:.

- How to make the most out of the opportunities you meet.

- How to be proactive with market changes and thrive by adapting quickly.

- How product innovation becomes the source of competitive advantage.

- How strengths like in-depth knowledge of specific markets become powerful expanding factors.

- How to grow by taking advantage of unparalleled localization.

- How growth opportunities are revealed by empowering your management.

- How sustainability can be used as a brand lever.

With over 2.5 billion people consuming its products on any given day, it’s difficult to find any corner of the world where Unilever has not reached.

What started as one soap brand has now become one of the world’s largest consumer brand conglomerates, spreading into beauty and personal care, home care, and food and refreshments.

Unilever's market share and key statistics:

- Staggering turnover of €52.4 billion in 2021

- Portfolio of 400+ brands, 13 of which feature in Kantar Worldpanel Global Top 50

- 14 brands with a $1 billion turnover

- Over 53,000 supplier partners

- Number of employees worldwide: 148,000

- Owning 280 factories, 270 offices and 450 logistics warehouses globally

- A reach spanning over 190 countries

From innovative strategies and impeccable management to effective marketing and commitment to sustainability, there are several reasons behind the success of this multi-industry giant.

In this study, we analyze them closely to highlight how Unilever has been able to continuously expand its horizons over the years and across countries as well as continents, gaining a competitive edge while growing exponentially.

{{cta('eed3a6a3-0c12-4c96-9964-ac5329a94a27')}}

Humble beginnings: How did Unilever start?

Although it wasn't until 1929 that the company we now instantly recognize as Unilever was formed, its story goes way back to the late 19th Century.

In fact, it is set in two different countries simultaneously, with two major companies operating in seemingly different industries coming together and setting the foundation of Unilever.

In many ways, it can be said that it set the tone for what sort of brand Unilever was going to be in the coming years.

More than just soap

_(14779880014)%20(1).jpg)

William Hesketh Lever began his career in the 1880s as a salesman in his family's grocery business. At the time, The Long Depression was still affecting the global economy, and many companies were struggling to survive.

Amidst the chaos, Lever saw an opportunity to step into the manufacturing of soap, which he believed had great potential for growth.

Thus, in the 1890s, as the founder of Lever Brothers, William Lever penned his ideas for Sunlight Soap: "to make cleanliness commonplace; to lessen work for women; to foster health and contribute to personal attractiveness, that life may be more enjoyable and rewarding for the people who use our products."

Mission and vision statements were hardly a thing during the Victorian era. Yet, Lever was well ahead of his time. They envisioned changing attitudes towards hygiene and personal care in the UK and solve customers’ problems simultaneously.

Soon, the company was not only making waves in the British Isles, but also began expanding its reach in many parts of Europe, North America, Australia, and South Africa.

The first bar of Sunlight Soap was in 1884

Diversifying operations

In the early 1900s, much of Britain's consumption of butter and margarine was sourced from Dutch and Danish companies. However, with the threat of WWI and trade coming to a standstill, the British government asked Lever to produce margarine as well.

Recognizing that the required raw materials, including oils and fats, were quite similar for soaps and margarine, William Lever welcomed the opportunity with open hands.

From there on, Lever became more than a soap company as it took its first step towards forming a multi-brand legacy that would inspire and lead the world of consumer brands for the next century and probably, beyond.

A manufacturing company through and through

Not only did Lever plan to manufacture its products, but it also extended its operations to produce its raw materials itself.

From mills to crush seeds for vegetable oil to whole transportation and packaging operations, Lever became a well-established vertically integrated company, taking giant strides to redefine the consumer goods industry.

The Dutch side of things

Before Lever Brothers had set foot in the margarine industry, there was already intense competition in the Dutch market.

To see off new entrants exporting their products at lower prices and to make the most of the global economic situation, two Dutch giants Jurgens and Van den Bergh joined hands in 1908.

A few years later, in 1920, these two companies combined with Schitt and established their operations in the Netherlands as Margarine Unie NV and in England as Margarine Union Limited.

This put them in direct competition with the Lever Brothers and what ensued was a tussle of giants for most of the following decade.

Putting Uni and Lever together

Both the Dutch and English companies knew they would benefit from synergies if they came together rather than going head-to-head in the soap and margarine industries.

Thus, after two years of discussions, they merged in 1929 to form Unilever, which was owned by two holding companies, Unilever Limited and Unilever NV, with setups in both countries.

The structures for the holding companies were identical, and the profit-sharing was on an equal basis.

This merger allowed the company to foray into multiple industries and establish dominance with its hold on manufacturing operations.

Key takeaway 1: cash In on opportunities

With the amalgamation of two companies – Lever Brothers and Margarine Unie – Unilever was formed.

From Lever entering an utterly new soap manufacturing business to competitors Jurgens and Van den Bergh combining, there are countless examples of the founders of Unilever realizing an opportunity and being quick to grab it.

Navigating The Great Depression – Initial Challenges

Unilever was still in its early years when the Great Depression struck, and the company was riddled with challenges on all fronts.

Its products’ prices plummeted 30% to 40% within the first year while at the same time butter came forward as an even cheaper alternative, further lowering the demand for margarine. The company’s agricultural products, such as cattle cake, also took a major hit and its retail grocery and fish shops saw a major decline in revenues.

Things did not look too bright for the company that had already shown so much promise and growth. However, just as William Lever had come out of the Long Depression as a successful business, Unilever responded proactively to this crisis too.

Responding to the challenge

The 1930s saw fresh faces managing the operations at Unilever with Francis D'Arcy Cooper at the helm of affairs.

This new management’s initial response to the Great Depression was to form a special committee that would oversee the firm’s operations in both Netherlands and UK. It also supervised two further committees; one that would handle the company’s business in Europe and one for other regions.

These actions helped the company mitigate the immediate effects of the recession and lay the groundwork for further changes.

Restructuring & redistributing assets

Initially, the Dutch group contributed two-thirds of Unilever's total profits while the British side accounted for the remaining. However, owing to trade conflicts in Europe, similar to those preceding WW1, the equation was reversed, and the British group's contribution increased.

Therefore, in 1937, Cooper convinced the company’s boards that it was time for restructuring, and Unilever needed to align itself with its original goal of equal profit sharing. As part of this dynamic shift, one significant action was selling the Lever Brothers Company in the United States and other Lever Brothers' assets outside Britain to Unilever's Dutch group.

This allowed the two factions to operate with nearly equal profit volumes and assets and overcome the trade challenges.

Key takeaway 2: proactively adapt to the situation

Had Unilever not set up the special committee and undergone the changes it did in the 1930s, it is possible it would not have survived the Great Depression. But with pro-activeness and resilience, it was able to tackle the challenges successfully and come out on the other side stronger than before.

Growth Through Localization & Innovation

Following the years of the Great Depression and WWII, the world’s economic landscape completely transformed. At that point in time, Unilever was establishing itself in various countries and needed a strategy to localize its products, marketing efforts, and management.

It realized that growth in new markets now was not limited to or even dependent on increasing production capacities or lining up products. It needed to have a strong footing in research and development to keep up with changing consumer preferences and increasing competition.

This meant that the company had to make some much-needed changes in its approach and it did just that.

Heading into new markets

Unilever was growing and expanding its operations into many new countries and diverse communities. This meant more local challenges wherever it set up operations. However, much of the management was still under the control of Dutch and English representatives of the parent companies.

Undoubtedly, the people from the parent head offices were capable managers and had contributed to the company's growth, but the challenge here was different. Markets such as India, Brazil, or even the USA did not function in the same way as European Markets.

Customers had different preferences, supply chains were unique, and external influencing factors, such as laws and regulations, were also always specific to the respective regions. Therefore, Unilever's management needed local players who could understand what was required in their region and develop effective strategies to achieve it.

Hence, in the 1940s, Unilever started a localization policy referred to as 'ization.’ The Dutch and English representatives were recalled, and local positions were handed over to local executives.

It began to be implemented as early on as 1942, with the company’s Indian subsidiary going through the process of Indianization. Australianization, Brazilianization, and more followed it. These centers had greater autonomy in decision-making and marketing, which enabled the company to penetrate further into these new markets and localize its products.

Unilever continued with this localized, decentralized management system throughout WWII and several years following. However, they did encourage Unileverization, sharing a common mission across their various subsidiaries during this time, and took it up more rigorously later on.

Embracing research & innovation

The embracing of research did not occur before facing a few setbacks. For instance, the market for soap, Unilever’s main product, revolved around color, scent, and application on fabrics. This changed when in the 1950s, their competitor in the US Market, Proctor & Gamble, introduced Tide. This nonsoap synthetic detergent powder was far superior and solved many plumbing problems caused by insoluble soaps.

For some years, Unilever remained behind its competitors until it found a way to solve the shortcomings of new detergent.

Tide was formed from petrochemicals, and its residues in sewerage systems and rivers were causing major problems. Now, Unilever had the chance to explore chemical technology and retain its position in the market. By 1965, they had launched their very own biodegradable version of the product.

It wasn’t just soap where Unilever invested in research. The company also established 11 research centers, including laboratories, all around the world to come up with innovative solutions for food preservation, health, and animal care. That was going to define the company as one that looked ahead into the future and relied on improving itself to remain at the top.

Another significant example of Unilever's constant innovation can be seen in its margarine. When butter was short in supply, margarine became a convenient alternative – one of the reasons why the Lever Brothers started manufacturing it in the first place. However, butter soon became available widely again, and that too at lower prices. Now, there was not much that made margarine an enticing option to customers.

Unilever's laboratory in Vlaardingen was tasked to find a way to improve the quality of margarine and make it stand out, whether through better nutrition, flavor, or convenience. The solution came in the form of enhanced refining of soybean oil, a key raw material in margarine production.

Benefiting from tariff lift

A major boost to Unilever's operations was the formation of the European Economic Community and its efforts to make Europe a common market in the 1950s and 1960s.

Previously, Unilever has based its factories and production in various European countries to avoid tariff restrictions. It was, however, an inconvenient solution. Not only did they have to bear additional costs of production in expensive locations, but such a spread-out production system posed the challenges of supply, logistics, capacity, and more.

Through the common market, there was no need to restrict themselves anymore. Unilever now took its production to wherever costs could be minimized, and operations could be consolidated. Thus, they were able to produce in greater quantities and accelerate their processes.

Key takeaway 3: innovate & solve

Unilever's growth in 1940 to 1960s had a lot to do with improving their products and their management system to cater to modern problems. This helped them stay ahead of the competition and keep their production up-to-date and cost-effective all the while delighting customers.

Expansion & Acquisitions Till The 1990s

As a well-known multi-industry firm, Unilever was no stranger to acquisitions and takeovers. They expanded in the US Market in 1937 by adding the tea manufacturer Thomas J. Lipton Company to their portfolio. Later on, in 1944, they also entered the toothpaste industry by acquiring Pepsodent.

In the post-WWII era, they continued to take over larger firms like Birds Eye, a UK frozen foods company, in 1957. By 1961, they had also taken control of US ice cream producer, Good Humor.

Unilever acquires Birds Eye parent company T. J. Lipton in 1943

However, these were only gradual acquisitions that allowed them to explore new product lines. From the 1980s, Unilever's approach took an aggressive turn, and they set their eyes on bringing many more brands under their banner.

The shopping spree of the 80s

Unilever’s targets changed in the 1980s. They wanted to expand but with a plan to strengthen their hold in industries in which they had resources and expertise and the market had a lucrative potential for growth. This meant they were sticking to foods, detergents, toiletries, etc. but were ready to eliminate the competition.

Thus, they began by selling off their ancillary business and services, such as transporting, packaging, and initiating their acquisitions. In 1984, Unilever oversaw a hostile takeover of the British tea company Brooke Bond for £376 million. The company complemented Unilever’s Lipton in the USA, and now, the road was clear for further growth.

One of Unilever’s biggest acquisitions was of Chesebrough-Pond in 1986. The company owned some very high-potential and popular products in the USA like Vaseline Intensive Care and Pond's Cold Cream. Moreover, with over $3 billion in annual sales, it was the perfect chance to cement itself in the personal product business internationally.

Another major market that the company dominated with its acquisitions in the late 1980s was the perfume and cosmetic industry. It simultaneously became the owner of Shering-Plough's perfume business in Europe, Calvin Klein in the US, and Fabergé Inc. The latter was bought for $1.55 billion and handed Chloe, Lagerfeld, and Fendi perfumes to Unilever.

Now, the company was a force to reckon with, if not the leader in its primary industries and in the markets it predicted would generate the most gains.

The global giant

Unilever clearly showed its aggressive intent in the 1980s, and they were not going to stop in the 1990s.

By 1992, the conglomerate consisted of over 500 businesses in 75 countries. In the mid-1990s, they went on to acquire over 100 more companies. From buying personal care giant Helene Curtis for $770 million to sweeping the US ice cream market by buying Philip Morris's Kraft General Foods’ division for $215 million, there was no shortage of the treasure chest Unilever had.

By 1999, they had grown from 500 businesses to 1600 brands. But this brought them back to where they started the extensive series of acquisitions, with many companies that didn't have the potential to grow or simply didn't fall in with Unilever's strengths.

It was time for a major strategy shift and to go back to the basics. Out of 1600 brands, 400 were generating 90% of the revenue. Unilever decided to let go of the remaining 1200 and put all its efforts into strengthening its already powerful brands.

This has been their path ever since and one that has enabled them to maintain their position as one of the top consumer products companies in the world.

Toppling competitors

Along with buying their competitors, Unilever did not stop introducing new products into the market. In 1984, their product Whisk overtook P & G’s Cheer in the US laundry detergent market.

Two years later, Whisk was introduced in Britain, along with Breeze, a soap powder the company had only seen of in Surf. Unsurprisingly, Unilever recorded a 50% growth in operating profits for detergent products while it also experienced increasing returns in the food industry.

This multi-pronged strategy of introducing new products and acquiring ones with potential did not allow Unilever to capitalize fully on the market's potential for growth and left little room for competitors to adjust.

Standing out from the competition

From Lever Brothers and Margarine Unie taking on their rivals head-on to Unilever PLC establishing its unique identity despite battling against giants P&G and Nestle, the company has always embraced healthy competition.

One of the main reasons Unilever has been so successful in standing out is its expansion in over 190 countries through products they specialize in and dominate in. Moreover, it hands significant decision-making power to local managers to strengthen their position in diverse markets. Both P&G and Nestle have not been able to grow as much in terms of reach.

Another, key aspect that differentiates Unilever is its emphasis on and funding towards Research & Development. They continue to improve their products and adapt to changing consumer needs by providing enhanced solutions.

Last but not least, Unilever’s sustainable plans set them apart from major competitors, whereby they show their commitment to the collective betterment of people and societies.

Key takeaway 4: stick to your strengths

Unilever’s origins lay in soap and margarine – industries they knew very well and had the potential to grow in. They expanded their portfolio but stuck to their strengths and, as a result, grew exponentially.

Changing Product Groups With Evolving Markets

Throughout the nearly 100 years of Unilever, they have acquired and sold brands and expanded their reach into many territories. Naturally, they experiment with product groups and divisions to decide which suits their goals best and when.

At times, their product groups have had a significant influence on their strategies, whereas at other times, they were merely playing advisory roles. But whatever the situation, Unilever has kept an eye on how operations and revenues were affected and carefully reorganized their groups accordingly.

Understanding complex markets

There is no one fixed way to distribute product groups. Sometimes, they require to focus on research and distribution while emphasizing localization from time to time. For instance, the food industry, from which many of Unilever's top brands belong, undergoes changes every few years. It can be categorized into three regional groups.

Firstly, the global fast-food category. Fried chicken, burgers, soft drinks, etc., are famous worldwide, from Asia to Europe and beyond. The core products remain the same, and the tastes do not differ greatly.

The next category is international foods. These are products that belong to one country but are also popular in other countries as well—for example, Chinese, Indian, and Italian foods.

Hence, the third category leads to national foods – those that represent and are popular in their country of origin. For Unilever's base region, the UK, pies, puddings, steaks, etc., are considered national foods.

Now, that is only one way to look at food markets. Another method or problem, as you may call it, is that a product may not even be defined or preferred the same way in different regions.

For example, take something as simple as tea - a globally consumed product. The British like their tea hot and with milk; Americans prefer it iced; Middle Easterners drop the milk and add sugar.

Therefore, Unilever cannot keep its product groups fixed or stringent and must recognize where it can churn out the most profits.

Giving more autonomy to product groups

Until the 1960s, Unilever's localization policy played a major role in its decisions and actions. Product groups served advisory or assisting roles with little power. That was how to company was progressing, and there was no need for change.

Carrying on the example of food products, during and post-WWII, raw material sourcing was a crucial factor in the production of Unilever foods. But then, when the 60s came, and firms, along with Unilever, started to invest in research, the dynamic shifted towards preservation technology and logistics.

Gradually, the power of determining revenues was handed to product groups, and local managers took a backseat. A pivotal change made in the new structure was introducing three separate food units: edible fats, frozen foods and ice cream, and a general food and drinks group.

These groups proved fruitful and helped the company expand in the European and North American markets.

Rising consumer awareness

The 1970s was the time the marketing arena transformed. With every brand wanting to stand out, they popularized concepts, such as healthy eating and natural ingredients.

The surge in demand for low-calorie foods was also a result of effective marketing. The challenge for Unilever was that all three of its food groups contained low-calorie products. It came in the way of their progress and dented their profits.

But how could they form a system that resolved this problem and kept local managers and product groups intact?

Unilever formed a committee called “Food Executive” consisting of three directors. Its role was to control all food products instead of leaving it to specific groups or managers.

Now, there are 5 product groups: edible fats, meals and meal components, beverages, ice cream, and professional markets. They play an essential role as advisors (more valued than in the 1960s) but are not responsible for profits.

Simultaneously, local managers are allowed to oversee the regional needs and preferences of consumers.

Key takeaway 5: balancing decentralization and product groups

Managers and product groups are both vital components of a multinational firm. To ensure their products satisfy consumers’ wants, Unilever continues to come up with ways to combine the two productively.

Unilever Strategy - Management Dynamics Over The Years

One of the key factors that have fueled Unilever's growth ever since 1929 is its evolving management dynamics that have allowed the company to stay true to its roots while adapting to the local areas it operates in.

Think globally. Act locally!

Think globally and act locally has been at the heart of Unilever's operations and enabled it to make a mark in even the most far-flung areas successfully. As a result of trial and error, Unilever's management dynamics over the years showcase the company's drive to excel, innovate, learn, and get the job done.

Let's delve deep into the management dynamics to better understand the growth of the company.

Given that both the parent companies of Unilever had a tradition of scaling their business through export as well as local production that British and Dutch expatriates mostly ran, it comes as no surprise that Unilever, too, had the same management style initially. British and Dutch executives ran the show, at least for the first decade. However, in the early 1940s, Unilever began changing things by hiring local managers to lead the operations in respective parts of the world, as already highlighted in Chapter 3.

The localization and decentralization began with the subsidiary in India in 1942. Key roles were given to Indian managers, who were also provided with the freedom and flexibility to run operations on their own with little involvement from the head office on a day-to-day basis.

This process of localization of management, in addition to the growing competition as well as the alienation of the subsidiaries during World War 2, led to decentralization, with each subsidiary becoming a self-reliant and self-sufficient unit.

This is where the senior management decided that while decentralization has indeed paid off, it would be in the company's best interest to guard against too much of it. Hence, to ensure that the Unilever culture, vision, and mission were shared among all subsidiaries, Unileverization was promoted.

It has now become a long-standing practice at Unilever to regularly train managers from around the world, be it at a Unilever Four Acres facility or hired facilities in local areas, to ensure that Unilever's values are ingrained and followed everywhere.

The Unilever management matrix, which mainly consists of local talent and initiative with centralized control, is empowered to think transnationally. From nurturing local talent to cross-posting managers worldwide so that they can gain diverse experiences, better understand the Unilever culture, and establish unity, an array of practices are followed.

Break communication barriers

Given the sheer size and scale of Unilever around the globe, effective communication across borders is an essential need for it. It doesn’t come as a surprise that the most relevant and used language for all forms of communication is English.

Hence, Unilever actively looks for employees with fluency in the English language when hiring and regularly invests to develop the English language as well as communication skills in general for its employees through various training programs.

Pick the cream of the crop

Alone you can only go so far; together the sky is the limit with what you can achieve. Unilever takes it a step further by hiring the best as well as the brightest and then unifying them to achieve remarkable results.

While it comes as no surprise that Unilever pays huge emphasis on onboarding the right people, the way how it goes about the process of recruitment offers a lesson to other businesses. Right from the mid-twentieth century, Unilever has continued to pioneer employee section systems.

From getting involved in universities to spot talent early on to sponsoring an extensive range of business courses, Unilever has done it all. Plus, trainees – as part of a group – are offered on-job experiences and courses at training facilities, allowing Unilever to create a holistic network of individuals whose informal experiences act as a glue that drives the company.

In addition to this, the vast system of attachments that allow employees to work on temporary assignments and projects in different parts of the world further grooms them offers them exposure and provides the 'know-how' of how Unilever functions. This empowers them and helps them further the unique Unilever way of working wherever they go next.

The company's formal structure, together with the informal exchanges leads to the transfer of ideas, enhances communication, and fosters collaboration, which in turn, boosts innovation and helps solve problems, allowing Unilever to continue to grow.

Modern workforce and workplace

Being resourceful is the new corporate approach of Unilever, which accounts for a number of organizational changes to prepare for the future, including:

- Tapping the open talent economy to boost the workforce whenever needed

- Harnessing the power of digital to drive business growth

- Being more creative and thinking out of the box to achieve goals

- Creating a better work-life balance and work environment

One example of Unilever’s unique approach to setting itself up for success in the future and unlocking its capacity to grow is its “YourFreelo” program in which internal resources of the company are offered holistic support through freelancers with different perspectives and handy skills.

Iterative improvements thanks to trial & error

From the outside, it may appear that it is Unilever's transnational strategy that has helped pave its way to success. While that wouldn’t be wrong to conclude but if we delve deep, we can find that it’s the messier revolution brought to the fore by continuous trial and error that has driven the company.

Hiring and training managers and leaders carefully, as well as linking decentralized units with a common culture, are the primary reasons behind the company's growth. That being said, the company has cautiously treated the path of an informal transnational network, realizing that it can elevate risks and lead to complacency.

To guard against it, the company continues to shake up the system every now and then, shifts roles, and responsibilities and evolves in the dynamic business world where change is the only certainty. By rethinking, reviewing, and reforming the strategies, the company manages to tackle the tricky waters and win.

Key takeaway 6: Develop bold middle-management

One of the major reasons behind the success and growth of Unilever has been its management, which doesn’t shy away from taking bold steps when needed. In addition to this, Unilever continues to invest in human capital and experiment as well as explore to stay a step ahead in the ever-evolving dynamic age.

Sustainable Living Plan – The Game-Changer For Business Growth

Seldom do businesses as large as Unilever get a chance to re-invent themselves and throw caution to the winds by taking the difficult long-term approach that can even negatively impact their bottom line.

In 2010, Unilever did just that by launching the Unilever Sustainable Living Plan (USLP), pioneering a new business model.

Playing their part in the environment

At the core of the plan lies Unilever's commitment to doing right by people and the planet with its purpose-driven ambition of halving its environmental footprint while doubling its size and making the world a better place for 8 billion people.

Fighting climate change by ending deforestation, ensuring food security by championing sustainable agriculture, and investing in water, safety, and hygiene to uplift people's lives, Unilever set the bar higher than ever before.

Has Unilever been successful in achieving its targets? You bet it has.

By pushing the company in a unique way, further than ever before, in its quest to build a sustainable and equitable future, Unilever has delighted all stakeholders, appealed to the masses, and showed how companies can lead from the front by taking a stand at issues that matter.

Following are some of the highlights of the USLP more than ten years after its launch depicting how Unilever has made an explicit positive contribution to address the key challenges:

- Reached over 1.2 billion worldwide with health and hygiene programs

- Lowered the environmental footprint per customer by one-thirds

- Reduced greenhouse gas emissions by two-thirds

- Achieved 100% renewable grid electricity across all plants

- Achieved zero landfills across all factories

- Cut down on over €1 billion on costs by reducing waste and enhancing energy as well as water efficiency

"Brands with purpose grow; companies with purpose last; and people with purpose thrive."

Embedding sustainability into the business has yielded remarkable results for Unilever.

Unilever's purpose-led brands have contributed immensely to Unilever's growth in a day and age where sustainability has become mainstream as around two-thirds of consumers opt for a particular brand because of its stand on social issues, and more than 90% of millennials prefer brands that strive to elevate humanity.

According to Unilever , its purpose-driven brands contribute to almost 75% of the company's growth and are growing 69% faster than the rest of the business, depicting that the huge bet has indeed paid off.

While Unilever could have easily waited for consumers and governments worldwide to push it to embrace sustainability rather than do it all by itself – that too ahead of the time – it portrayed itself as the leader with the focus on the bigger picture which stands by its values and is not afraid to do the right thing even when the odds are stacked against it.

Key takeaway 7: Make sustainability part of your business strategy

Pioneering sustainability businesses, Unilever started a movement for social change in 2010 that helped it re-invent itself for good. It has paid off for the company, making customers fall head over heels for their brands.

Why is Unilever so successful?

Unilever is always in transition, equipping itself to continue making a difference well into the future. It isn’t perfect given its fair share of products that don’t seem sustainable or advertising campaigns that don’t go hand in hand with its values. However, it is a company on a big mission to transform the world, setting an example for the rest to follow.

Performance beyond expectations In challenging & uncertain circumstances

The year 2020 was volatile and unpredictable in ways more than one for all businesses operating around the globe. From supply chain bottlenecks to change in the way consumers shop and employees work, there were an array of disruptions, leading to an uncertain business environment.

Yet, in the face of such adversity, Unilever has stayed true to the values that have always made it a force to be reckoned with – resilience and agility – and hence, not only survived but also thrived.

While underlying operating profit fell by 5.8% in 2020, the company experienced a boost in underlying sales growth of 1.9%. This can be mainly attributed to the company’s long-term planning, flexibility, and sustainable objectives.

Hence, where other companies focused on driving growth temporarily, Unilever developed their current and future strategies on sustainability and inclusiveness for growth. An example is their stronghold in emerging economies of China, India, and the USA, where they have always looked to include locals and contribute to society’s uplift.

Moreover, Unilever went ahead with a major shift in its legal structure in 2020 to stabilize and unify its operations worldwide. Formerly run by cross-border companies, Unilever NV and Unilever PLC, Unilever has consolidated itself into the single umbrella of Unilever PLC, becoming stronger than ever.

Below is a graph of Unilever's annual revenue in Euro Millions

Growth by the numbers

List of key strategic takeaways.

- Impact-driven Businesses Succeed

Now more than ever, it has become difficult for companies to achieve a competitive advantage. So, what can a business do? Be relevant to society and offer a multi-stakeholder return, benefiting all and crafting real change. It definitely pays off.

- Always Be Proactive and Flexible

Change is the only certainty, so you need to embrace it. Your best bet is to be on the lookout for potential opportunities that present themselves from time to time and grab them with both hands. You can do that if you remain agile and act quickly.

- Prioritize Investing In Human Capital

Your single most important asset is your people. Empower them so that they can help you elevate your brand. Right from hiring the ‘right’ people to nurturing them, you need to continuously invest in human capital in order to achieve lasting success.

- Take Risks To Grow

You can only reach the top with iterative improvements made possible by continuous innovation and risk-taking. Keep experimenting, testing, and exploring: if you achieve the desired result, you win, if you don’t, you learn.

- Encourage Sustainable Living And Make It Effortless

Weave sustainability into your processes and value chains. From the raw material used to the packaging, make sure you use eco-friendly practices to add value to the lives of people. This way you can win consumer goodwill and trust.

- Stay Intune With The DNA Of Your Brand

In the quest to do more and become more, you can easily forget to stay true to your ultimate purpose. Go back to the drawing board whenever needed, regularly communicate your purpose to your target audience, and stand up for what you stand for to separate yourself from the rest.

Unilever’s journey from one soap brand with a handful of sales and customers to the leading multinational consumer goods company with billions of consumers worldwide has been incredible and offers a number of lessons, including:

While we don’t know what the future holds, we are pretty much certain that Unilever is here to stay and dominate, doing right by the people and planet.

Unilever PESTEL Analysis

Before we dive deep into the PESTEL analysis, let’s get the business overview of Unilever. Unilever is one of the world’s leading suppliers of fast-moving consumer goods in food, home care, and personal care.

Founded in 1929 due to a merger between the British soapmaker Lever Brothers and the Dutch margarine producer Margarine Unie, Unilever has become a global powerhouse in the FMCG (Fast Moving Consumer Goods) sector.

Here is an overview of Unilever’s business:

- Products and Brands : Unilever’s portfolio includes a wide range of products across diverse categories. Some of its most recognizable brands include Dove, Axe/Lynx, Ben & Jerry’s, Lipton, Magnum, Hellmann’s, Knorr, Sunsilk, and Surf, among others.

- Global Presence : Unilever operates in over 190 countries, and its products are used by billions of consumers daily. The company’s operations are often divided into regions: Europe, the Americas, Asia, Africa, and the Middle East.

- Beauty & Personal Care : This is the largest segment and includes skincare, haircare, deodorants, and oral care products.

- Home Care : This includes laundry detergents, household cleaning products, and related offerings.

- Foods & Refreshment : This segment comprises a diverse range of food products, including soups, bouillons, sauces, snacks, mayonnaise, salad dressings, spreads, and ice cream.

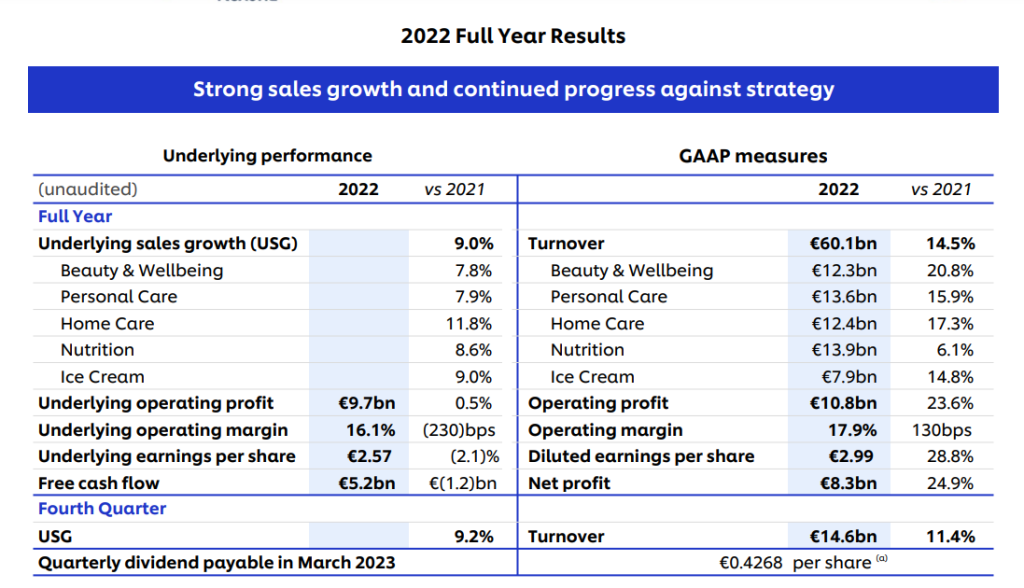

Financial Performance of Unilever

Turnover increased 14.5% to €60.1 billion, and the underlying operating profit was €9.7 billion, up 0.5% versus the prior year.

Business Strategies that set FMCG giant “Unilever” a class apart

Here is the PESTEL analysis of Unilever

A PESTEL analysis is a strategic management framework used to examine the external macro-environmental factors that can impact an organization or industry. The acronym PESTEL stands for:

- Political factors: Relate to government policies, regulations, political stability, and other political forces that may impact the business environment.

- Economic factors: Deal with economic conditions and trends affecting an organization’s operations, profitability, and growth.

- Sociocultural factors: Relate to social and cultural aspects that may influence consumer preferences, lifestyles, demographics, and market trends.

- Technological factors: Deal with developing and applying new technologies, innovations, and trends that can impact an industry or organization.

- Environmental factors: Relate to ecological and environmental concerns that may affect an organization’s operations and decision-making.

- Legal factors: Refer to the laws and regulations that govern businesses and industries.

In this article, we will do a PESTEL Analysis of Unilever.

PESTEL Analysis Framework: Explained with Examples

Political

- Trade Regulations and Tariffs : Unilever operates in over 190 countries, so changes in trade policies, such as the imposition of tariffs or trade barriers, can have significant implications on its supply chain and distribution strategies.

- Political Stability : Countries with political unrest or instability can affect Unilever’s operations. For instance, civil strife, sudden regime changes, or political violence can disrupt the company’s manufacturing, distribution, or sales processes in those regions.

- Government Policies : Governmental policies related to health, safety, and quality standards can impact Unilever’s product formulations. For instance, certain countries may restrict specific ingredients in personal care or food products.

- Taxation Policies : Changes in tax regulations or corporate tax rates in countries where Unilever has significant operations can influence its financial performance.

- Regulation on Advertising and Promotion : Governments may impose regulations on how certain products (like foods with high sugar content or skincare products) are advertised or promoted. This can affect Unilever’s marketing strategies.

- Environmental Regulations : Political decisions related to environmental conservation can affect Unilever, especially given the company’s sustainability objectives. For example, regulations related to plastic packaging or waste management can impact Unilever’s operations.