Find anything you save across the site in your account

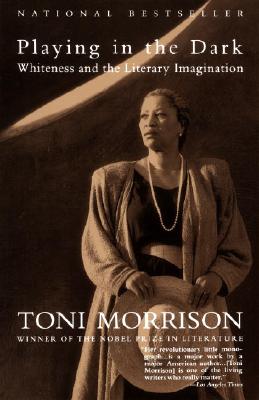

The Work You Do, the Person You Are

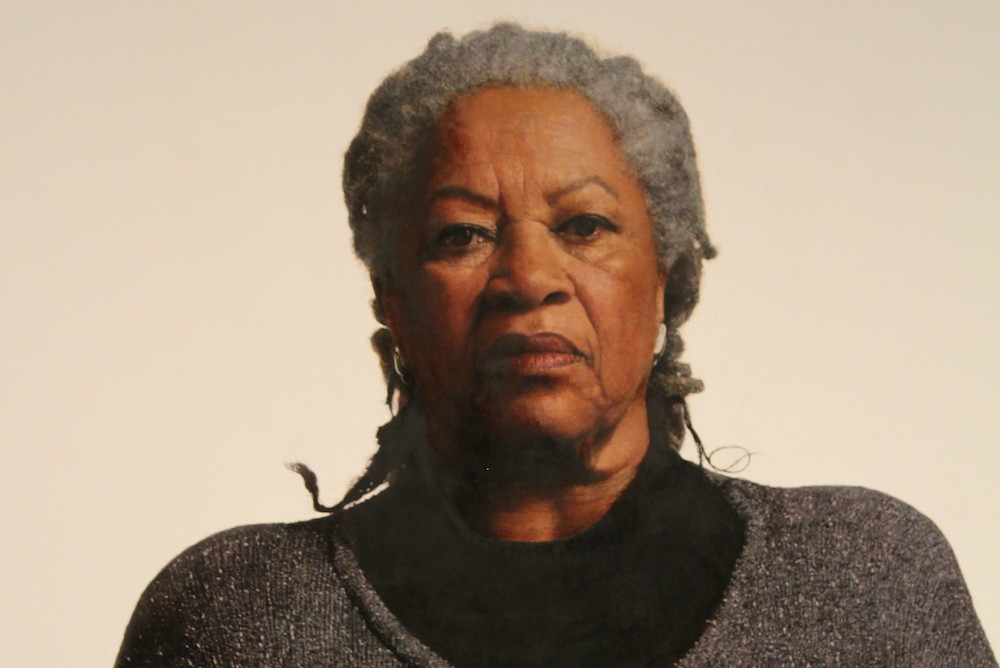

By Toni Morrison

All I had to do for the two dollars was clean Her house for a few hours after school. It was a beautiful house, too, with a plastic-covered sofa and chairs, wall-to-wall blue-and-white carpeting, a white enamel stove, a washing machine and a dryer—things that were common in Her neighborhood, absent in mine. In the middle of the war, She had butter, sugar, steaks, and seam-up-the-back stockings.

I knew how to scrub floors on my knees and how to wash clothes in our zinc tub, but I had never seen a Hoover vacuum cleaner or an iron that wasn’t heated by fire.

Part of my pride in working for Her was earning money I could squander: on movies, candy, paddleballs, jacks, ice-cream cones. But a larger part of my pride was based on the fact that I gave half my wages to my mother, which meant that some of my earnings were used for real things—an insurance-policy payment or what was owed to the milkman or the iceman. The pleasure of being necessary to my parents was profound. I was not like the children in folktales: burdensome mouths to feed, nuisances to be corrected, problems so severe that they were abandoned to the forest. I had a status that doing routine chores in my house did not provide—and it earned me a slow smile, an approving nod from an adult. Confirmations that I was adultlike, not childlike.

In those days, the forties, children were not just loved or liked; they were needed. They could earn money; they could care for children younger than themselves; they could work the farm, take care of the herd, run errands, and much more. I suspect that children aren’t needed in that way now. They are loved, doted on, protected, and helped. Fine, and yet . . .

Little by little, I got better at cleaning Her house—good enough to be given more to do, much more. I was ordered to carry bookcases upstairs and, once, to move a piano from one side of a room to the other. I fell carrying the bookcases. And after pushing the piano my arms and legs hurt so badly. I wanted to refuse, or at least to complain, but I was afraid She would fire me, and I would lose the freedom the dollar gave me, as well as the standing I had at home—although both were slowly being eroded. She began to offer me her clothes, for a price. Impressed by these worn things, which looked simply gorgeous to a little girl who had only two dresses to wear to school, I bought a few. Until my mother asked me if I really wanted to work for castoffs. So I learned to say “No, thank you” to a faded sweater offered for a quarter of a week’s pay.

Still, I had trouble summoning the courage to discuss or object to the increasing demands She made. And I knew that if I told my mother how unhappy I was she would tell me to quit. Then one day, alone in the kitchen with my father, I let drop a few whines about the job. I gave him details, examples of what troubled me, yet although he listened intently, I saw no sympathy in his eyes. No “Oh, you poor little thing.” Perhaps he understood that what I wanted was a solution to the job, not an escape from it. In any case, he put down his cup of coffee and said, “Listen. You don’t live there. You live here. With your people. Go to work. Get your money. And come on home.”

That was what he said. This was what I heard:

1. Whatever the work is, do it well—not for the boss but for yourself.

2. You make the job; it doesn’t make you.

3. Your real life is with us, your family.

4. You are not the work you do; you are the person you are.

I have worked for all sorts of people since then, geniuses and morons, quick-witted and dull, bighearted and narrow. I’ve had many kinds of jobs, but since that conversation with my father I have never considered the level of labor to be the measure of myself, and I have never placed the security of a job above the value of home. ♦

More in this series

New Yorker Favorites

The day the dinosaurs died .

What if you started itching— and couldn’t stop ?

How a notorious gangster was exposed by his own sister .

Woodstock was overrated .

Diana Nyad’s hundred-and-eleven-mile swim .

Photo Booth: Deana Lawson’s hyper-staged portraits of Black love .

Fiction by Roald Dahl: “The Landlady”

Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Norman Rush

By Gillian Flynn

By Catherine Barnett

By Jack Handey

Toni Morrison Let Us Know We Are More Than the Work We Do

Books & Culture

Considering some of the legendary novelist's lessons on the anniversary of her death.

Adapted from remarks given at the Toni Morrison Festival in February 2020.

About three years ago, Toni Morrison wrote a short and, as is her style, superlative essay in The New Yorker titled “ The Work You Do, The Person You Are .” At a young age, Morrison delineated an understanding of the fear of losing the power of a dollar while also recognizing the burdens of employment even with the financial reward. Morrison didn’t reveal the race of the person she worked for, but the power dynamics beyond employee and employer were clear; the status was clear. The piece concludes with her translation of a quick response from her father when she bemoaned how she was treated as an employee. Morrison condensed her father’s response to the following tenets:

1. Whatever the work is, do it well—not for the boss but for yourself. 2. You make the job; it doesn’t make you. 3. Your real life is with us, your family. 4. You are not the work you do; you are the person you are. I have worked for all sorts of people since then, geniuses and morons, quick-witted and dull, bighearted and narrow. I’ve had many kinds of jobs, but since that conversation with my father I have never considered the level of labor to be the measure of myself, and I have never placed the security of a job above the value of home.

When we think about Morrison, we most prominently, and for good reason, dissect the writing she’s gifted us, material we can turn to weeks, months, years after her sunset. The New Yorker essay also bestows an understanding of her work ethic—though it’s an ethic we could have intuited from how methodical and responsible she was with the written word. When I read Morrison I don’t only take in the work of a magnanimous writer; I also consider how clearly her editorial framework comes through the control and distinction she pays to text, in pieces and as a whole. The impact she had as an editor further curated her love of books and at the same time distilled how she lived her life, how she represented herself, who she represented. (See Contemporary African Literature, Corregidora, The Black Book, to name a few.)

In the first chapter of P laying in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination , Morrison conveys her early way of reading, when she presumed that Black people were of no consequence in the white American literary imagination. She digs into how Black people were erased in the white-dominated “canon,” and investigates white Americans’ willful refusal to read books about or by African Americans. And if white Americans weren’t reading those books, how could the white literary establishment publish them? “But then,” Morrison writes, “I stopped reading as a reader and began to read as a writer.” By altering her viewpoint, Morrison better informed her reading and empowered herself to acquire more books by Black writers. From the start of her time in publishing, this perspective allowed her to magnify the gaps in contemporary literature celebrated by white audiences, and to elevate books deserving the same shelf space. (See Tenet 2: “You make the job; it doesn’t make you.”)

Earlier this year I became an employee within a division of the publishing house where Toni Morrison once worked. Her name is inextricably linked with this press, due to her publications and the impact she had as an editor in the scholarly and trade divisions. There are many, though trust me not enough , hard-working and dedicated Black women in publishing. Recently, new names are being added to the roster, which we can hope is a lead-in for many more to come. Pre-quarantine we walked the halls and sat in conference rooms. Nowadays we enter virtual rooms where we are still one of a few if not the only. We speak our truths or hold our tongues, all in the name of a larger strategy to see and make a difference. We stay because we love the work and because we want to showcase the intrinsic dedication and brilliance of those of our ilk. We do the work because the work needs to get done. The navigation of being “the only” or “one of the few” requires a singular focus and a clear strategy to keep going. This is not just about the industry, it’s about our belief and love for what we bring to it.

Morrison more than likely fought in ways subdued, calculated, and blatant when she entered the office environment.

It may not be a surprise that Toni Morrison was one of the first Black women editors at Random House during her 19-year tenure. It may not be a surprise that she was one of the first Black women in this space with acquisitions power. It may not surprise you that she was one of the first Black women in this space to enter a “boys club,” a club I guarantee didn’t know how to recognize her as an equal, even when they shared the same title—though not the same salary. (To this day her adamance of “head of household” in the documentary The Pieces I Am rings true of the battle cry to make a proper and equitable wage to men.) What we can ascertain from this is that Morrison more than likely fought in ways subdued, calculated, and blatant when she entered the office environment as editor and then again outside of it, or adjacently as author when discussing her work again and again and again. Imagine the strength of mind and character it takes to be on both sides of the coin, to uplift Black people in your work each and every day when people don’t always see them the way you do, most notably as equals and most derogatorily as people. Imagine the love for the people one has to pursue this work as adamantly and precisely as she did and bring it in all ways to a deep admiration and honesty day in and day out. (See Tenet 1: “Whatever the work is do it well—not for the boss but for yourself.”)

Black publishing professionals continue to navigate working within the system while also trying to combat an industry that continues to provide roadblocks to access let alone retention, even when it purports to value Black lives. There’s no easy or singular answer to maintaining your own values in a space that does not value you as a person, let alone the work you’re producing or helping to produce. Like Morrison did in these same spaces, we may assert or negotiate or magnify the larger importance of the content and creators we support, not just for the company but for the nation. These may be seen as negotiations and yet they’re also part of the fight. At some point we all come to terms with the fact that negotiation can no longer be about what we will tolerate, but what we will not accept.

We know how much Morrison achieved—it is worth repeating and the right way to speak of someone who achieved so much. But alongside the achievements we know of, there are many that we do not know about. Ones that may seem small but are monumental in getting through each day. Ones in which we defend and deflect, be it ourselves or whatever opposes us. The ways of navigating what may not, outwardly, appear to be a hostile environment, but one that will not acknowledge that you deserve more. Having experienced this in ways both aggressive and passive-aggressive, I continually think of those who are the sole (or rare) entity carving out a way to be seen and, unintentionally and often unwillingly, representing so many others. As Hilton Als noted in his New Yorker profile on Morrison, she “preferred to publish writers who had something to say about Black American life that reflected its rich experience.” This is the way she published, wrote, and read. This is who Morrison was and how she exemplified an eternal love for Black people. This is who she prioritized in the roles she held and I can only imagine the ways she fought for them in these same halls/rooms/spaces.

This is who Morrison was and how she exemplified an eternal love for Black people.

This year, at the height of the George Floyd protests, many businesses designated June 2nd as Blackout Tuesday, a day of (optional or enforced) mourning. My company gave me the option to take that day off. I performed my job functions anyway because my grief didn’t start or end on that Tuesday. In the afternoon, I sat at a desk in the corner of my living room. I spoke calmly into a headset for a video conference in recognition of this moment. I spoke into what has felt like a void in quarantine, even more so due to the intense quiet and periodical appearance of teary-eyed/somber faces on my screen. I had no video, so my Blackness was not on display in the way it would be if we all still shared office space. Pledges to be conscious, to be more aware, to make more efforts in the content published and the people present on the line were made. My headphones pulsed with the repetition of how valued Black people were especially as we kept producing. I talked to other Black writers and publishing professionals and we spoke honestly and with uncertainty. At the end of the day several people said to me, “All we have is us” and “Keep doing what you’re doing because it’s important” and “We see you.” The power of those words from those you know beyond a moment makes us take a breath, and a break, before we resume. (See Tenet 4: “You are not the work you do; you are the person you are.”)

I began with a quote from Morrison, so it makes sense to end with one: “Being a Black woman writer is not a shallow, but a rich place to write from. It doesn’t limit my imagination, it expands it. It’s richer than being a white male writer because I know more and I’ve experienced more.” To be a Black women editor in a large publishing world, who you are has to be as distinct as how you read and discuss what you read. Morrison has written extensively of that awareness in her reading, and how it led her to prioritize who she was always trying to reach, and allowed her to broker past the issues of “what could sell” to land on what is needed and desired. It may come as no surprise her contextual awareness of being, not just as writer but as a Black woman, also allowed Morrison as editor, as teacher, as speaker, as observer to conquer the world at large and recognize, as well as continually illustrate, that we could too. (See Tenet 3: Your real life is with us, your family.)

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven't read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.

ARTICLE CONTINUES AFTER ADVERTISEMENT

Langston Hughes Knows You’re Tired—But He’s Not Letting You Off the Hook

The internet has fallen in love with a poem that reflects our fatigue, but there's a second half that demands our action

Aug 4 - Jasmine Harris Read

More like this.

Ralph Ellison’s Unfinished Magnum Opus “Juneteenth” Was 40 Years in the Making

After an early draft was lost to arson in 1967, the manuscript ballooned to more than 2,000 pages by Ellison’s death in 1994

Jun 19 - Kristopher Jansma

“Barracoon” Went Unpublished for 87 Years Because Zora Neale Hurston Wouldn’t Compromise

Hurston cared about authenticity more than fame — and finally, the world is catching up to her

May 15 - Dianca London

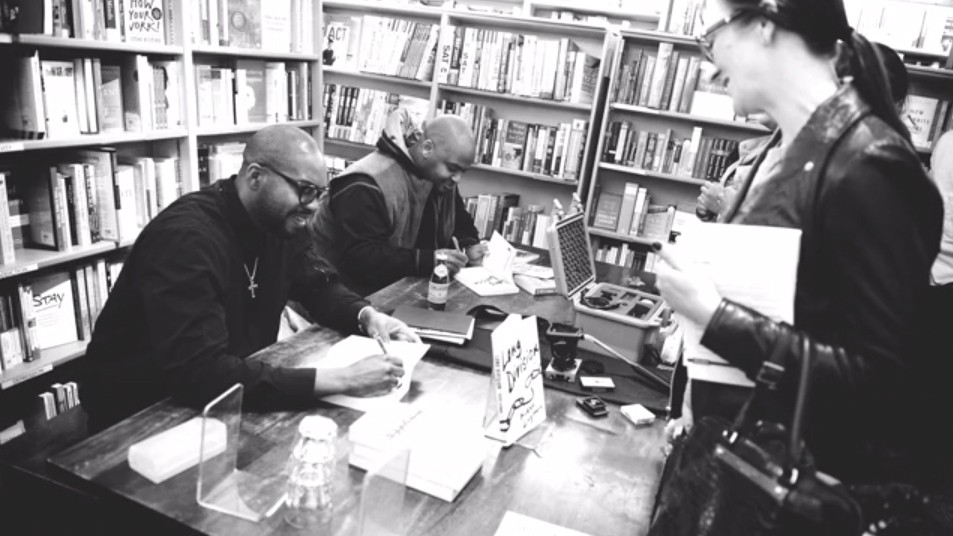

Mitchell S. Jackson and Kiese Laymon Discuss Literature, Race, and Publishing Their First Books

Jun 20 - lincoln michel.

DON’T MISS OUT

Sign up for our newsletter to get submission announcements and stay on top of our best work.

- United Kingdom

Advice From Toni Morrison: You Are Not Your Work

Advice from toni morrison: "you are not your work", more from work & money, r29 original series.

Join Now to View Premium Content

GradeSaver provides access to 2360 study guide PDFs and quizzes, 11007 literature essays, 2767 sample college application essays, 926 lesson plans, and ad-free surfing in this premium content, “Members Only” section of the site! Membership includes a 10% discount on all editing orders.

Toni Morrison: Essays

Toni morrison's work ethic in "the work you do, the person you are" ayelén victoria rodríguez 12th grade.

Maintaining her style, Toni Morrison goes over the struggles of class differences in her essay, "The Work You Do, the Person You Are." She produces a reflective piece that puts in evidence the strong mentality and craving she had for mattering, of achieving important things, since she was a child. Having been the first black woman writer to win the Nobel Prize of literature, Morrison goes back to her beginnings to show the readers what work ethics had led her to such success, stating, as the title implies, that the work one does never defines the person one is.

The text begins with the child being grateful for being paid two dollars for doing what she considered as very few chores in the house. This can be understood when she says “all I had to do for two dollars...”. We can see the clear difference between this beginning at the house and the end at it, which seems to be as if she is being exploited by the amount of work she is given, which in the end turns out to be even harmful physically “after pushing the piano my arms and legs hurt so badly”.

Toni Morrison is also able to make an impact on the reader, and realize the social differences by the way the child describes the house where she works and how her patroness is...

GradeSaver provides access to 2312 study guide PDFs and quizzes, 10989 literature essays, 2751 sample college application essays, 911 lesson plans, and ad-free surfing in this premium content, “Members Only” section of the site! Membership includes a 10% discount on all editing orders.

Already a member? Log in

[from the archives] the work you do, the person you are

From august 2020. on work and identity and where the two (/don't) meet, feat. toni morrison, hilma af klint, zadie smith and liz gilbert.

** this archived issue of T H E | L I M I N A L was originally sent in August 2020. you can read other past issues here (password: theliminal2020) **

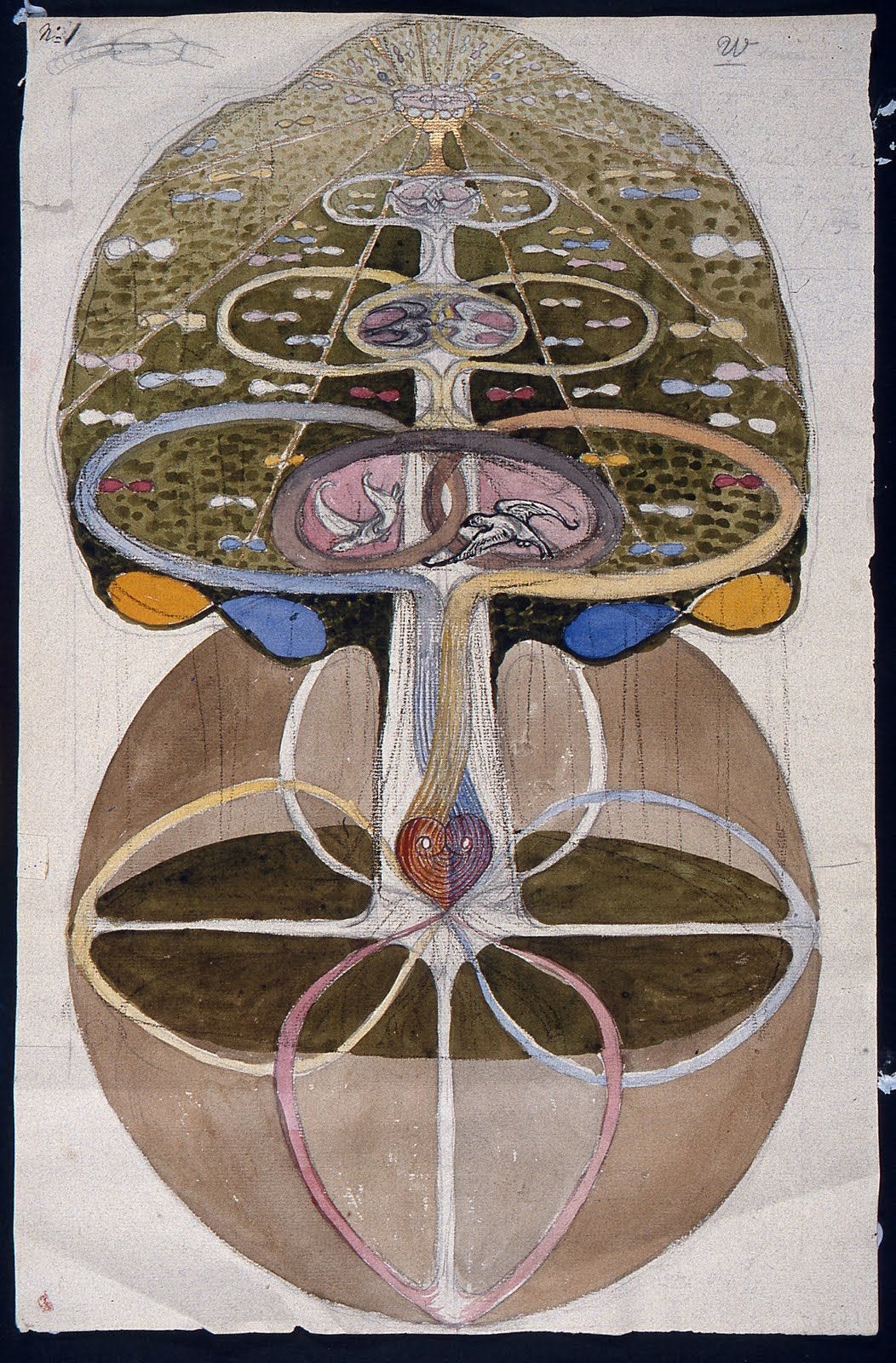

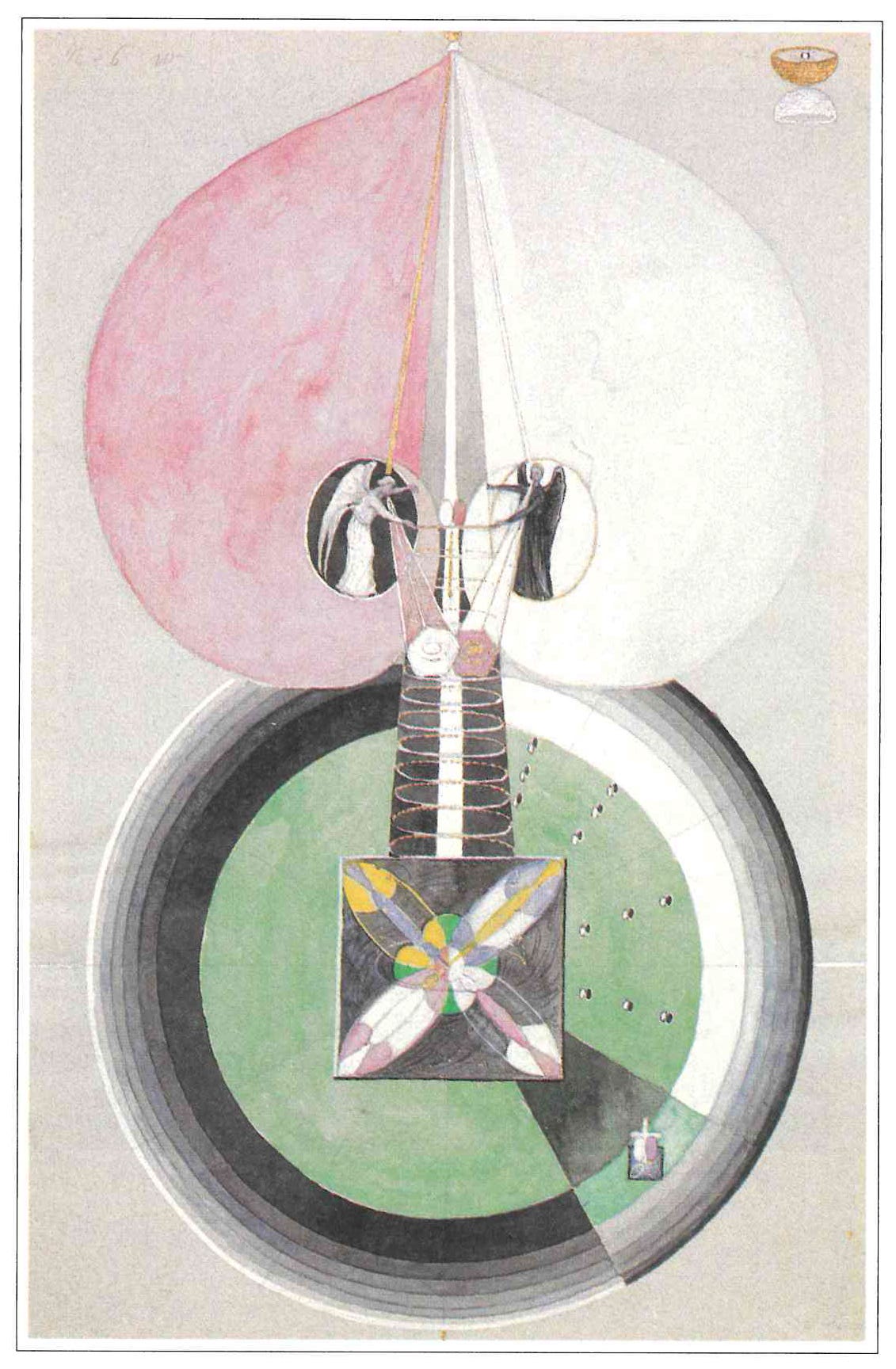

This issue features the inimitable, avant-garde work of Swedish artist and mystic, Hilma af Klint (b. 1862 - d. 1944). Her art is considered by (revisionist) art historians to be the very first work of Western abstract art, predating the so-called pioneer of abstract art Wassily Kandinsky. Kunskapens träd nr. 1, Hilma af Klint

The work you do; the person you are. What’s the difference? What’s the same?

It’s a question Toni Morrison poses in her 2017 New Yorker article by the same name, and one I’ve been asking myself a lot lately.

Perhaps a side effect of being a student/academic for the past 21 of your 28 years is that August will always feel like back-to-school/work (despite the irony of being a PhD student who is simultaneously always-and-never “at work”). It is muscle memory. Carved into the synapses.

This August, the “back-to-” feeling is stirring but falling flat. It doesn’t know where to go; it doesn’t recognise this world despite the tempo of the lunar calendar. The idea of back-to-anything seems an off-tune joke in a world where the familiar, rote, and routine is turned on its head. I reckon I’m not the only one feeling this.

2020-isms aside—over here, in our little family, there’s been a lot of existentialism about work and careers going on. Entering the sixth (+ final!) year of my PhD, I’m facing the consequences of “hiding out” in the relative coziness and secure funding of the past five years—the question of “ what next? ” always (until now) out-there in the distance. August has been a month of postdoc applications and personal statements, going through the motions to enter an academic job market which is threatened at its worst to go near-extinct, and at its best to be forever changed (this is not necessarily a bad thing). Sometimes, these applications feel like a charade. The surface-question— How do you write about future plans when the world keeps reminding you it’s futile to have them?— belies a more brooding question I struggle to admit— Do I even want to go where this path is leading? Can I trust it? Can I trust me?

I watch the people I love grapple with versions of these questions. Tobias is bravely navigating a long-brewing career change in a new city, having quit his job two weeks before the pandemic hit. I’ve watched my parents, in early retirement facing long days of social distancing and quarantine ahead, crave the structure and meaning of working life. My mother has returned to practicing therapy, offering pro-bono sessions for US immigrants on Zoom; my father has returned to his first academic love, writing, penning a science-fiction novel that has been brewing on the peripheries of his imagination for the past 40 years. I’ve watched many of you claim your art and creative passions and talents as your main work ( have I ever told you how much you inspire me? ). I’d argue we’ve never needed your art more, even as I imagine that some days it feels impossible (please keep creating and let us know how we can support you).

In many ways, this current landscape of work is dire and foreboding. But I think there’s something to recuperate here too. We’re finally starting to question the machinery , the rhythms of our work, its sustainability, its purpose, and our internalizations of a capitalism which puts profit and productivity before human and ecological well-being ( which, I might add, is nothing new, even though some of us are now seeing it for the first time ).

Issue 08 of T H E | L I M I N A L explores the changing nature of work and how we bring our work into resolution with who we understand ourselves to be. I draw from the musings and words of women whose work I deeply admire — Zadie Smith, Elizabeth Gilbert, Toni Morrison, Hilma af Klint.

As is often the case, I have more ruminations and questions than solid answers. And I wouldn’t be surprised if this is the first of several newsletter issues grappling with these tensions. I acknowledge that even posing these questions about work belies a certain privilege—and that at the end of the day most of us are trying to make ends meet. I hope this is a space where you can feel safe to explore these questions with me. They are powerful and uncomfortable—if I’ve learned anything in the past few years: that’s where the magic happens.

Kunskapens träd nr. 6, Hilma af Klint

MUSING OF THE MOMENT

On work and identity, and where the two (do/don’t) meet

Today, the mic goes to four women whose writings and musings have recently been framing, dismantling, and re-sculpting my own reflections on work, meaning, and identity:

The first is Swedish artist Hilma af Klint , whose illustrations and paintings, inspired by otherworldly séances and that which cannot be seen, are featured in this issue. You may have noticed in the first caption I said “ revisionist” art history recognizes Klint as the first Western abstract artist (a title typically bestowed to Kandinsky). This is because Klint, a mystic, did not share her unprecedented work [1,200 paintings, 100 texts, 26,000 pages of notes] during her lifetime. In fact, she left special instructions for it not to be shared until at least 20 years after her death. Her reasoning? The world, as she left it, was not yet ready to receive its meaning . How is that for egoless-ness and clairvoyance? Even as her (male) contemporaries were being hailed for ushering a new era of art, Klint quietly trusted in the timing of her work. Klint’s detachment of her own ego and recognition from the work itself, at least in her own lifetime—a belief inherent in the work and its afterlife—is admirable if not also puzzling. Perhaps by relinquishing the imperative to be seen as an artist, she freed herself to create work that was daring and deeply spiritual, inward- as opposed to outward- facing. It is as if Hilma’s legacy poses these questions to us all: What is our attachment to the visibility of our work? Can we source in it a value, belief, and trust even if it is never shown? What would you do, if you relinquished the gaze of others? Would it set you free?

From the otherworldly clairvoyance and future-oriented work of Klint, we move to the deeply grounded and humanizing words of Toni Morrison in her article “The Work You Do, The Person You Are.” Morrison reminds us that our value far exceeds that which we do or produce, but from a different lens. In the article, Morrison reflects on early advice from her father on her very first employment at a young age—a housecleaning job (“what I wanted was a solution to the job, not an escape from it”). Her father’s words, and her interpretation, assert boundaries of over-identifying with one’s work and affirm the very practical realities of earning money to support one’s family. Indeed, much of Morrison’s writing career was carved in the margins and pauses from other very real demands and responsibilities—Morrison famously would wake before dawn (before her children said “Mama”) to write in the early hours. Much of her art was born from this contrast and carving of space-apart. Toni Morrison is also a beautiful reminder that it is never too late to redefine your work: she was first published at the age of 39.

According to Elizabeth Gilbert , we regularly confuse and interchange four words that are actually quite distinct: hobby , job , career and vocation ( notice nowhere does the word “work” appear ). Disentangling these four words’ meanings can yield a new way to frame why you do what you do, where you direct your energy , and how you envision it unfolding (it certainly has for me). I appreciate how Gilbert puts these terms in relationship to one another, and to the practical realities of making a living. For instance, guided by a commitment to her vocation (writing) Gilbert decided to forego a career in favor of several, often simultaneous, jobs that paid the bills. One arena I think deserves more attention is whether and how what we call hobbies can actually be generative and supportive of our vocation… but not that they need be (for instance, this newsletter, which is most definitely a hobby—and one which brings me great joy, at that—sometimes feels closer to what I imagine as my core vocation than the applications I’m making for my “job”). Food for thought: how do you recognize yourself with relation to these concepts? ( scroll down to journal about it below) .

Finally, 2020 in all its tumult ( a global pandemic, the anti-racism movement, fascist uprisings, senseless killings, fires, hurricanes, social distancing…you know, I need not regale here ) reveals that sometimes, the meaning we attach to most everything (especially work) falls away and leaves us raw. Beloved novelist and nonfiction writer Zadie Smith , in her flash-nonfiction book of essays Intimations just released one month ago (and book of the month for us), impressively bears witness to the pandemic and lockdown of Spring 2020, in-vivo, as-unfolding. While the thought of authoring an entire (albeit slim 100-page) book during the dawn of the pandemic might seem entirely untenable to many of us, Smith is reflexive, accessible, and writes from her pure lively necessity of doing so ( “Talking to yourself can be useful. And writing means being overheard.” ) What I enjoyed most about Intimations , and relevant to our conversation here, is Smith’s depiction of writing as vocation in the pandemic era, in her essay “Something to Do.” In it, she admits “ in the first week (of lockdown) I found out how much of my old life was about hiding from life.” She recounts being “exposed” in the itinerancy and un-structure of her daily writing routines, witnessed by her family at home with her during workdays for the first time (I’ve never felt so seen, hi Tobias).

I leave you with Zadie Smith’s words, which capture more eloquently than I can the existential conundrum of doing-work in this moment:

“ I can’t rid myself of the need to do ‘something,’ to make ‘something,’ to feel that this new expanse of time hasn’t been ‘wasted.’ … Watching this manic desire to make or grow or do ‘something,’ that now seems to be consuming everybody, I do feel comforted to discover I’m not the only person on this earth who has no idea what life is for, nor what is to be done with all this time aside from filling it.” — Zadie Smith ( Intimations, 2020)

WRITING PROMPT

Writing prompt priming: watch this talk by Liz Gilbert…

Right now, in this very moment, what is/are your…

…hobby(/ies)?

How are these in alignment with who you know yourself to be? How are they not? Where is there space for soft adjustment? Realignment? (or a good old burn-it-down-and-begin-again?)

Ready for more?

danoshinsky.com

I’m Dan Oshinsky, and I run Inbox Collective, an email consultancy. I'm here to share what I've learned about doing great work and building amazing teams.

Here, Read This: “The Work You Do, the Person You Are.”

This essay by Toni Morrison is fantastic, and you should read the whole thing, but I’ll quote one section here — Toni’s four rules for work:

1. Whatever the work is, do it well—not for the boss but for yourself.

2. You make the job; it doesn’t make you.

3. Your real life is with us, your family.

4. You are not the work you do; you are the person you are.

Read the whole piece here.

Thesis Statements

What this handout is about.

This handout describes what a thesis statement is, how thesis statements work in your writing, and how you can craft or refine one for your draft.

Introduction

Writing in college often takes the form of persuasion—convincing others that you have an interesting, logical point of view on the subject you are studying. Persuasion is a skill you practice regularly in your daily life. You persuade your roommate to clean up, your parents to let you borrow the car, your friend to vote for your favorite candidate or policy. In college, course assignments often ask you to make a persuasive case in writing. You are asked to convince your reader of your point of view. This form of persuasion, often called academic argument, follows a predictable pattern in writing. After a brief introduction of your topic, you state your point of view on the topic directly and often in one sentence. This sentence is the thesis statement, and it serves as a summary of the argument you’ll make in the rest of your paper.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement:

- tells the reader how you will interpret the significance of the subject matter under discussion.

- is a road map for the paper; in other words, it tells the reader what to expect from the rest of the paper.

- directly answers the question asked of you. A thesis is an interpretation of a question or subject, not the subject itself. The subject, or topic, of an essay might be World War II or Moby Dick; a thesis must then offer a way to understand the war or the novel.

- makes a claim that others might dispute.

- is usually a single sentence near the beginning of your paper (most often, at the end of the first paragraph) that presents your argument to the reader. The rest of the paper, the body of the essay, gathers and organizes evidence that will persuade the reader of the logic of your interpretation.

If your assignment asks you to take a position or develop a claim about a subject, you may need to convey that position or claim in a thesis statement near the beginning of your draft. The assignment may not explicitly state that you need a thesis statement because your instructor may assume you will include one. When in doubt, ask your instructor if the assignment requires a thesis statement. When an assignment asks you to analyze, to interpret, to compare and contrast, to demonstrate cause and effect, or to take a stand on an issue, it is likely that you are being asked to develop a thesis and to support it persuasively. (Check out our handout on understanding assignments for more information.)

How do I create a thesis?

A thesis is the result of a lengthy thinking process. Formulating a thesis is not the first thing you do after reading an essay assignment. Before you develop an argument on any topic, you have to collect and organize evidence, look for possible relationships between known facts (such as surprising contrasts or similarities), and think about the significance of these relationships. Once you do this thinking, you will probably have a “working thesis” that presents a basic or main idea and an argument that you think you can support with evidence. Both the argument and your thesis are likely to need adjustment along the way.

Writers use all kinds of techniques to stimulate their thinking and to help them clarify relationships or comprehend the broader significance of a topic and arrive at a thesis statement. For more ideas on how to get started, see our handout on brainstorming .

How do I know if my thesis is strong?

If there’s time, run it by your instructor or make an appointment at the Writing Center to get some feedback. Even if you do not have time to get advice elsewhere, you can do some thesis evaluation of your own. When reviewing your first draft and its working thesis, ask yourself the following :

- Do I answer the question? Re-reading the question prompt after constructing a working thesis can help you fix an argument that misses the focus of the question. If the prompt isn’t phrased as a question, try to rephrase it. For example, “Discuss the effect of X on Y” can be rephrased as “What is the effect of X on Y?”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? If your thesis simply states facts that no one would, or even could, disagree with, it’s possible that you are simply providing a summary, rather than making an argument.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? Thesis statements that are too vague often do not have a strong argument. If your thesis contains words like “good” or “successful,” see if you could be more specific: why is something “good”; what specifically makes something “successful”?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? If a reader’s first response is likely to be “So what?” then you need to clarify, to forge a relationship, or to connect to a larger issue.

- Does my essay support my thesis specifically and without wandering? If your thesis and the body of your essay do not seem to go together, one of them has to change. It’s okay to change your working thesis to reflect things you have figured out in the course of writing your paper. Remember, always reassess and revise your writing as necessary.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? If a reader’s first response is “how?” or “why?” your thesis may be too open-ended and lack guidance for the reader. See what you can add to give the reader a better take on your position right from the beginning.

Suppose you are taking a course on contemporary communication, and the instructor hands out the following essay assignment: “Discuss the impact of social media on public awareness.” Looking back at your notes, you might start with this working thesis:

Social media impacts public awareness in both positive and negative ways.

You can use the questions above to help you revise this general statement into a stronger thesis.

- Do I answer the question? You can analyze this if you rephrase “discuss the impact” as “what is the impact?” This way, you can see that you’ve answered the question only very generally with the vague “positive and negative ways.”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not likely. Only people who maintain that social media has a solely positive or solely negative impact could disagree.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? No. What are the positive effects? What are the negative effects?

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? No. Why are they positive? How are they positive? What are their causes? Why are they negative? How are they negative? What are their causes?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? No. Why should anyone care about the positive and/or negative impact of social media?

After thinking about your answers to these questions, you decide to focus on the one impact you feel strongly about and have strong evidence for:

Because not every voice on social media is reliable, people have become much more critical consumers of information, and thus, more informed voters.

This version is a much stronger thesis! It answers the question, takes a specific position that others can challenge, and it gives a sense of why it matters.

Let’s try another. Suppose your literature professor hands out the following assignment in a class on the American novel: Write an analysis of some aspect of Mark Twain’s novel Huckleberry Finn. “This will be easy,” you think. “I loved Huckleberry Finn!” You grab a pad of paper and write:

Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn is a great American novel.

You begin to analyze your thesis:

- Do I answer the question? No. The prompt asks you to analyze some aspect of the novel. Your working thesis is a statement of general appreciation for the entire novel.

Think about aspects of the novel that are important to its structure or meaning—for example, the role of storytelling, the contrasting scenes between the shore and the river, or the relationships between adults and children. Now you write:

In Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain develops a contrast between life on the river and life on the shore.

- Do I answer the question? Yes!

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not really. This contrast is well-known and accepted.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? It’s getting there–you have highlighted an important aspect of the novel for investigation. However, it’s still not clear what your analysis will reveal.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? Not yet. Compare scenes from the book and see what you discover. Free write, make lists, jot down Huck’s actions and reactions and anything else that seems interesting.

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? What’s the point of this contrast? What does it signify?”

After examining the evidence and considering your own insights, you write:

Through its contrasting river and shore scenes, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn suggests that to find the true expression of American democratic ideals, one must leave “civilized” society and go back to nature.

This final thesis statement presents an interpretation of a literary work based on an analysis of its content. Of course, for the essay itself to be successful, you must now present evidence from the novel that will convince the reader of your interpretation.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Lunsford, Andrea A. 2015. The St. Martin’s Handbook , 8th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Ramage, John D., John C. Bean, and June Johnson. 2018. The Allyn & Bacon Guide to Writing , 8th ed. New York: Pearson.

Ruszkiewicz, John J., Christy Friend, Daniel Seward, and Maxine Hairston. 2010. The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers , 9th ed. Boston: Pearson Education.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Developing a Thesis Statement

Many papers you write require developing a thesis statement. In this section you’ll learn what a thesis statement is and how to write one.

Keep in mind that not all papers require thesis statements . If in doubt, please consult your instructor for assistance.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement . . .

- Makes an argumentative assertion about a topic; it states the conclusions that you have reached about your topic.

- Makes a promise to the reader about the scope, purpose, and direction of your paper.

- Is focused and specific enough to be “proven” within the boundaries of your paper.

- Is generally located near the end of the introduction ; sometimes, in a long paper, the thesis will be expressed in several sentences or in an entire paragraph.

- Identifies the relationships between the pieces of evidence that you are using to support your argument.

Not all papers require thesis statements! Ask your instructor if you’re in doubt whether you need one.

Identify a topic

Your topic is the subject about which you will write. Your assignment may suggest several ways of looking at a topic; or it may name a fairly general concept that you will explore or analyze in your paper.

Consider what your assignment asks you to do

Inform yourself about your topic, focus on one aspect of your topic, ask yourself whether your topic is worthy of your efforts, generate a topic from an assignment.

Below are some possible topics based on sample assignments.

Sample assignment 1

Analyze Spain’s neutrality in World War II.

Identified topic

Franco’s role in the diplomatic relationships between the Allies and the Axis

This topic avoids generalities such as “Spain” and “World War II,” addressing instead on Franco’s role (a specific aspect of “Spain”) and the diplomatic relations between the Allies and Axis (a specific aspect of World War II).

Sample assignment 2

Analyze one of Homer’s epic similes in the Iliad.

The relationship between the portrayal of warfare and the epic simile about Simoisius at 4.547-64.

This topic focuses on a single simile and relates it to a single aspect of the Iliad ( warfare being a major theme in that work).

Developing a Thesis Statement–Additional information

Your assignment may suggest several ways of looking at a topic, or it may name a fairly general concept that you will explore or analyze in your paper. You’ll want to read your assignment carefully, looking for key terms that you can use to focus your topic.

Sample assignment: Analyze Spain’s neutrality in World War II Key terms: analyze, Spain’s neutrality, World War II

After you’ve identified the key words in your topic, the next step is to read about them in several sources, or generate as much information as possible through an analysis of your topic. Obviously, the more material or knowledge you have, the more possibilities will be available for a strong argument. For the sample assignment above, you’ll want to look at books and articles on World War II in general, and Spain’s neutrality in particular.

As you consider your options, you must decide to focus on one aspect of your topic. This means that you cannot include everything you’ve learned about your topic, nor should you go off in several directions. If you end up covering too many different aspects of a topic, your paper will sprawl and be unconvincing in its argument, and it most likely will not fulfull the assignment requirements.

For the sample assignment above, both Spain’s neutrality and World War II are topics far too broad to explore in a paper. You may instead decide to focus on Franco’s role in the diplomatic relationships between the Allies and the Axis , which narrows down what aspects of Spain’s neutrality and World War II you want to discuss, as well as establishes a specific link between those two aspects.

Before you go too far, however, ask yourself whether your topic is worthy of your efforts. Try to avoid topics that already have too much written about them (i.e., “eating disorders and body image among adolescent women”) or that simply are not important (i.e. “why I like ice cream”). These topics may lead to a thesis that is either dry fact or a weird claim that cannot be supported. A good thesis falls somewhere between the two extremes. To arrive at this point, ask yourself what is new, interesting, contestable, or controversial about your topic.

As you work on your thesis, remember to keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times . Sometimes your thesis needs to evolve as you develop new insights, find new evidence, or take a different approach to your topic.

Derive a main point from topic

Once you have a topic, you will have to decide what the main point of your paper will be. This point, the “controlling idea,” becomes the core of your argument (thesis statement) and it is the unifying idea to which you will relate all your sub-theses. You can then turn this “controlling idea” into a purpose statement about what you intend to do in your paper.

Look for patterns in your evidence

Compose a purpose statement.

Consult the examples below for suggestions on how to look for patterns in your evidence and construct a purpose statement.

- Franco first tried to negotiate with the Axis

- Franco turned to the Allies when he couldn’t get some concessions that he wanted from the Axis

Possible conclusion:

Spain’s neutrality in WWII occurred for an entirely personal reason: Franco’s desire to preserve his own (and Spain’s) power.

Purpose statement

This paper will analyze Franco’s diplomacy during World War II to see how it contributed to Spain’s neutrality.

- The simile compares Simoisius to a tree, which is a peaceful, natural image.

- The tree in the simile is chopped down to make wheels for a chariot, which is an object used in warfare.

At first, the simile seems to take the reader away from the world of warfare, but we end up back in that world by the end.

This paper will analyze the way the simile about Simoisius at 4.547-64 moves in and out of the world of warfare.

Derive purpose statement from topic

To find out what your “controlling idea” is, you have to examine and evaluate your evidence . As you consider your evidence, you may notice patterns emerging, data repeated in more than one source, or facts that favor one view more than another. These patterns or data may then lead you to some conclusions about your topic and suggest that you can successfully argue for one idea better than another.

For instance, you might find out that Franco first tried to negotiate with the Axis, but when he couldn’t get some concessions that he wanted from them, he turned to the Allies. As you read more about Franco’s decisions, you may conclude that Spain’s neutrality in WWII occurred for an entirely personal reason: his desire to preserve his own (and Spain’s) power. Based on this conclusion, you can then write a trial thesis statement to help you decide what material belongs in your paper.

Sometimes you won’t be able to find a focus or identify your “spin” or specific argument immediately. Like some writers, you might begin with a purpose statement just to get yourself going. A purpose statement is one or more sentences that announce your topic and indicate the structure of the paper but do not state the conclusions you have drawn . Thus, you might begin with something like this:

- This paper will look at modern language to see if it reflects male dominance or female oppression.

- I plan to analyze anger and derision in offensive language to see if they represent a challenge of society’s authority.

At some point, you can turn a purpose statement into a thesis statement. As you think and write about your topic, you can restrict, clarify, and refine your argument, crafting your thesis statement to reflect your thinking.

As you work on your thesis, remember to keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times. Sometimes your thesis needs to evolve as you develop new insights, find new evidence, or take a different approach to your topic.

Compose a draft thesis statement

If you are writing a paper that will have an argumentative thesis and are having trouble getting started, the techniques in the table below may help you develop a temporary or “working” thesis statement.

Begin with a purpose statement that you will later turn into a thesis statement.

Assignment: Discuss the history of the Reform Party and explain its influence on the 1990 presidential and Congressional election.

Purpose Statement: This paper briefly sketches the history of the grassroots, conservative, Perot-led Reform Party and analyzes how it influenced the economic and social ideologies of the two mainstream parties.

Question-to-Assertion

If your assignment asks a specific question(s), turn the question(s) into an assertion and give reasons why it is true or reasons for your opinion.

Assignment : What do Aylmer and Rappaccini have to be proud of? Why aren’t they satisfied with these things? How does pride, as demonstrated in “The Birthmark” and “Rappaccini’s Daughter,” lead to unexpected problems?

Beginning thesis statement: Alymer and Rappaccinni are proud of their great knowledge; however, they are also very greedy and are driven to use their knowledge to alter some aspect of nature as a test of their ability. Evil results when they try to “play God.”

Write a sentence that summarizes the main idea of the essay you plan to write.

Main idea: The reason some toys succeed in the market is that they appeal to the consumers’ sense of the ridiculous and their basic desire to laugh at themselves.

Make a list of the ideas that you want to include; consider the ideas and try to group them.

- nature = peaceful

- war matériel = violent (competes with 1?)

- need for time and space to mourn the dead

- war is inescapable (competes with 3?)

Use a formula to arrive at a working thesis statement (you will revise this later).

- although most readers of _______ have argued that _______, closer examination shows that _______.

- _______ uses _______ and _____ to prove that ________.

- phenomenon x is a result of the combination of __________, __________, and _________.

What to keep in mind as you draft an initial thesis statement

Beginning statements obtained through the methods illustrated above can serve as a framework for planning or drafting your paper, but remember they’re not yet the specific, argumentative thesis you want for the final version of your paper. In fact, in its first stages, a thesis statement usually is ill-formed or rough and serves only as a planning tool.

As you write, you may discover evidence that does not fit your temporary or “working” thesis. Or you may reach deeper insights about your topic as you do more research, and you will find that your thesis statement has to be more complicated to match the evidence that you want to use.

You must be willing to reject or omit some evidence in order to keep your paper cohesive and your reader focused. Or you may have to revise your thesis to match the evidence and insights that you want to discuss. Read your draft carefully, noting the conclusions you have drawn and the major ideas which support or prove those conclusions. These will be the elements of your final thesis statement.

Sometimes you will not be able to identify these elements in your early drafts, but as you consider how your argument is developing and how your evidence supports your main idea, ask yourself, “ What is the main point that I want to prove/discuss? ” and “ How will I convince the reader that this is true? ” When you can answer these questions, then you can begin to refine the thesis statement.

Refine and polish the thesis statement

To get to your final thesis, you’ll need to refine your draft thesis so that it’s specific and arguable.

- Ask if your draft thesis addresses the assignment

- Question each part of your draft thesis

- Clarify vague phrases and assertions

- Investigate alternatives to your draft thesis

Consult the example below for suggestions on how to refine your draft thesis statement.

Sample Assignment

Choose an activity and define it as a symbol of American culture. Your essay should cause the reader to think critically about the society which produces and enjoys that activity.

- Ask The phenomenon of drive-in facilities is an interesting symbol of american culture, and these facilities demonstrate significant characteristics of our society.This statement does not fulfill the assignment because it does not require the reader to think critically about society.

Drive-ins are an interesting symbol of American culture because they represent Americans’ significant creativity and business ingenuity.

Among the types of drive-in facilities familiar during the twentieth century, drive-in movie theaters best represent American creativity, not merely because they were the forerunner of later drive-ins and drive-throughs, but because of their impact on our culture: they changed our relationship to the automobile, changed the way people experienced movies, and changed movie-going into a family activity.

While drive-in facilities such as those at fast-food establishments, banks, pharmacies, and dry cleaners symbolize America’s economic ingenuity, they also have affected our personal standards.

While drive-in facilities such as those at fast- food restaurants, banks, pharmacies, and dry cleaners symbolize (1) Americans’ business ingenuity, they also have contributed (2) to an increasing homogenization of our culture, (3) a willingness to depersonalize relationships with others, and (4) a tendency to sacrifice quality for convenience.

This statement is now specific and fulfills all parts of the assignment. This version, like any good thesis, is not self-evident; its points, 1-4, will have to be proven with evidence in the body of the paper. The numbers in this statement indicate the order in which the points will be presented. Depending on the length of the paper, there could be one paragraph for each numbered item or there could be blocks of paragraph for even pages for each one.

Complete the final thesis statement

The bottom line.

As you move through the process of crafting a thesis, you’ll need to remember four things:

- Context matters! Think about your course materials and lectures. Try to relate your thesis to the ideas your instructor is discussing.

- As you go through the process described in this section, always keep your assignment in mind . You will be more successful when your thesis (and paper) responds to the assignment than if it argues a semi-related idea.

- Your thesis statement should be precise, focused, and contestable ; it should predict the sub-theses or blocks of information that you will use to prove your argument.

- Make sure that you keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times. Change your thesis as your paper evolves, because you do not want your thesis to promise more than your paper actually delivers.

In the beginning, the thesis statement was a tool to help you sharpen your focus, limit material and establish the paper’s purpose. When your paper is finished, however, the thesis statement becomes a tool for your reader. It tells the reader what you have learned about your topic and what evidence led you to your conclusion. It keeps the reader on track–well able to understand and appreciate your argument.

Writing Process and Structure

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Getting Started with Your Paper

Interpreting Writing Assignments from Your Courses

Generating Ideas for

Creating an Argument

Thesis vs. Purpose Statements

Architecture of Arguments

Working with Sources

Quoting and Paraphrasing Sources

Using Literary Quotations

Citing Sources in Your Paper

Drafting Your Paper

Generating Ideas for Your Paper

Introductions

Paragraphing

Developing Strategic Transitions

Conclusions

Revising Your Paper

Peer Reviews

Reverse Outlines

Revising an Argumentative Paper

Revision Strategies for Longer Projects

Finishing Your Paper

Twelve Common Errors: An Editing Checklist

How to Proofread your Paper

Writing Collaboratively

Collaborative and Group Writing

Kalamu ya Salaam's information blog

POV: Toni Morrison—The Work You Do, The Person You Are

JUNE 5 & 12, 2017 ISSUE

THE WORK YOU DO,

The person you are, the pleasure of being necessary to my parents was profound. i was not like the children in folktales: burdensome mouths to feed., by toni morrison.

Illustration by Christoph Niemann

All I had to do for the two dollars was clean Her house for a few hours after school. It was a beautiful house, too, with a plastic-covered sofa and chairs, wall-to-wall blue-and-white carpeting, a white enamel stove, a washing machine and a dryer—things that were common in Her neighborhood, absent in mine. In the middle of the war, She had butter, sugar, steaks, and seam-up-the-back stockings.

I knew how to scrub floors on my knees and how to wash clothes in our zinc tub, but I had never seen a Hoover vacuum cleaner or an iron that wasn’t heated by fire.

Part of my pride in working for Her was earning money I could squander: on movies, candy, paddleballs, jacks, ice-cream cones. But a larger part of my pride was based on the fact that I gave half my wages to my mother, which meant that some of my earnings were used for real things—an insurance-policy payment or what was owed to the milkman or the iceman. The pleasure of being necessary to my parents was profound. I was not like the children in folktales: burdensome mouths to feed, nuisances to be corrected, problems so severe that they were abandoned to the forest. I had a status that doing routine chores in my house did not provide—and it earned me a slow smile, an approving nod from an adult. Confirmations that I was adultlike, not childlike.

In those days, the forties, children were not just loved or liked; they were needed. They could earn money; they could care for children younger than themselves; they could work the farm, take care of the herd, run errands, and much more. I suspect that children aren’t needed in that way now. They are loved, doted on, protected, and helped. Fine, and yet . . .

Little by little, I got better at cleaning Her house—good enough to be given more to do, much more. I was ordered to carry bookcases upstairs and, once, to move a piano from one side of a room to the other. I fell carrying the bookcases. And after pushing the piano my arms and legs hurt so badly. I wanted to refuse, or at least to complain, but I was afraid She would fire me, and I would lose the freedom the dollar gave me, as well as the standing I had at home—although both were slowly being eroded. She began to offer me her clothes, for a price. Impressed by these worn things, which looked simply gorgeous to a little girl who had only two dresses to wear to school, I bought a few. Until my mother asked me if I really wanted to work for castoffs. So I learned to say “No, thank you” to a faded sweater offered for a quarter of a week’s pay.

Still, I had trouble summoning the courage to discuss or object to the increasing demands She made. And I knew that if I told my mother how unhappy I was she would tell me to quit. Then one day, alone in the kitchen with my father, I let drop a few whines about the job. I gave him details, examples of what troubled me, yet although he listened intently, I saw no sympathy in his eyes. No “Oh, you poor little thing.” Perhaps he understood that what I wanted was a solution to the job, not an escape from it. In any case, he put down his cup of coffee and said, “Listen. You don’t live there. You live here. With your people. Go to work. Get your money. And come on home.”

That was what he said. This was what I heard:

1. Whatever the work is, do it well—not for the boss but for yourself.

2. You make the job; it doesn’t make you.

3. Your real life is with us, your family.

4. You are not the work you do; you are the person you are.

I have worked for all sorts of people since then, geniuses and morons, quick-witted and dull, bighearted and narrow. I’ve had many kinds of jobs, but since that conversation with my father I have never considered the level of labor to be the measure of myself, and I have never placed the security of a job above the value of home. ♦

>via: http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/06/05/the-work-you-do-the-person-you-are?utm_source=pocket&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=pockethits

- Featured Activities

- AP Activities

- Pre-AP Activities

- SpringBoard Activities

- ELA Standards

While Sandel argues that pursuing perfection through genetic engineering would decrease our sense of humility, he claims that the sense of solidarity we would lose is also important.

This thesis summarizes several points in Sandel’s argument, but it does not make a claim about how we should understand his argument. A reader who read Sandel’s argument would not also need to read an essay based on this descriptive thesis.

Broad thesis (arguable, but difficult to support with evidence)

Michael Sandel’s arguments about genetic engineering do not take into consideration all the relevant issues.

This is an arguable claim because it would be possible to argue against it by saying that Michael Sandel’s arguments do take all of the relevant issues into consideration. But the claim is too broad. Because the thesis does not specify which “issues” it is focused on—or why it matters if they are considered—readers won’t know what the rest of the essay will argue, and the writer won’t know what to focus on. If there is a particular issue that Sandel does not address, then a more specific version of the thesis would include that issue—hand an explanation of why it is important.

Arguable thesis with analytical claim

While Sandel argues persuasively that our instinct to “remake” (54) ourselves into something ever more perfect is a problem, his belief that we can always draw a line between what is medically necessary and what makes us simply “better than well” (51) is less convincing.

This is an arguable analytical claim. To argue for this claim, the essay writer will need to show how evidence from the article itself points to this interpretation. It’s also a reasonable scope for a thesis because it can be supported with evidence available in the text and is neither too broad nor too narrow.

Arguable thesis with normative claim

Given Sandel’s argument against genetic enhancement, we should not allow parents to decide on using Human Growth Hormone for their children.

This thesis tells us what we should do about a particular issue discussed in Sandel’s article, but it does not tell us how we should understand Sandel’s argument.

Questions to ask about your thesis

- Is the thesis truly arguable? Does it speak to a genuine dilemma in the source, or would most readers automatically agree with it?

- Is the thesis too obvious? Again, would most or all readers agree with it without needing to see your argument?

- Is the thesis complex enough to require a whole essay's worth of argument?

- Is the thesis supportable with evidence from the text rather than with generalizations or outside research?

- Would anyone want to read a paper in which this thesis was developed? That is, can you explain what this paper is adding to our understanding of a problem, question, or topic?

- picture_as_pdf Thesis

- TESTIMONIALS

- LOUD & CLEAR BLOG

- SUBSCRIBE TO BLOG

The Work You Do, The Person You Are

It has been well over 6 months since I have been able to share interesting posts with you and I am happy to announce we are back and extremely happy to be here once again. Since last Winter, much has changed and as I welcomed our baby boy to the world, I also welcomed new thoughts on how we work, learn and grow. I am conscious or aware that the seeds I plant now will be so essential for the future of our little one and the example I set as a working adult will be for him to follow as he grows. Therefore, as Spring came and went and we begin to quickly invite Summer I have given thought to who we are when we work, when we learn, age and evolve. I know, a bit deep for coming back suddenly, but hey, why not?

This post is dedicated to making us think about the pleasures of being necessary and ourselves at the same time, making those weekends stretch longer and longer and being productive…

One of my all time favorite writers, Toni Morrison , recently wrote on defining the person you are and the work you do. Two separate entities which we sometimes forget. Especially in today’s age when our work weighs so much on us as well as on our identity and we can inevitably lose the definition of who we really are and as a result, that fine line of leaving work behind when we are done with work becomes blurry (not focused). After speaking with her father as a child about work and being unhappy, her father responded the following:

1. Whatever the work is, do it well—not for the boss but for yourself.

2. You make the job; it doesn’t make you.

3. Your real life is with us, your family.

4. You are not the work you do; you are the person you are.

Morrison ends the article with the following: “I have worked for all sorts of people since then, geniuses and morons, quick-witted and dull, bighearted and narrow. I’ve had many kinds of jobs, but since that conversation with my father I have never considered the level of labor to be the measure of myself, and I have never placed the security of a job above the value of home.”

If you want to read the full article : http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/06/05/the-work-you-do-the-person-you-are

What do you think? Do you feel defined, confined or reassured by your work?

On a sweeter note, did you know you can make your weekend feel longer?? Yep, 48 hours can stretch just a little further…here is how (think new): http://nymag.com/scienceofus/article/how-to-make-the-weekend-last-longer.html

And finally, how to keep your sanity if you work alone…this is for all you freelancers or anyone who feels trapped in front of their computer on a daily basis! http://jkglei.com/freelance-sanity/

What are your thoughts? What do you do to make your working life happier?

Photo Source

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

2. You make the job; it doesn't make you. 3. Your real life is with us, your family. 4. You are not the work you do; you are the person you are. I have worked for all sorts of people since then ...

You are not the work you do; you are the person you are. I have worked f or al l sor ts of people since then, geniuses and morons, quic k-witted and dul l, bighear ted and narrow. I 've had many

The Work You Do, the Person You Are. The pleasure of being necessary to my parents was profound. I was not like the children in folktales: burdensome mouths to feed. By Toni Morrison. Toni Morrison knew how to work. In the course of her singular career, the Ohio-born writer produced eleven novels, nine children's books, and two plays.

Morrison condensed her father's response to the following tenets: 1. Whatever the work is, do it well—not for the boss but for yourself. 2. You make the job; it doesn't make you. 3. Your real life is with us, your family. 4. You are not the work you do; you are the person you are.

Intro Paragraph and Thesis: The stories "The work you do, The person you are" and "Drowning in Dishes, But finding a Home" share many similarities and differences. ... In "The work you do, The person you are" by Toni Morrison, the theme is that while work is important, it does not define you, you have a family at home that is very ...

After she finally lets a few complaints slip to her father, he gives her adult advice instead of the kid-glove treatment. In part: "Go to work. Get your money. And come on home." Morrison's ...

Join Now Log in Home Literature Essays Toni Morrison: Essays Toni Morrison's Work Ethic in "The Work You Do, the Person You Are" Toni Morrison: Essays Toni Morrison's Work Ethic in "The Work You Do, the Person You Are" Ayelén Victoria Rodríguez 12th Grade Maintaining her style, Toni Morrison goes over the struggles of class differences in her essay, "The Work You Do, the Person You Are."

Scribd is the world's largest social reading and publishing site.

From the otherworldly clairvoyance and future-oriented work of Klint, we move to the deeply grounded and humanizing words of Toni Morrison in her article "The Work You Do, The Person You Are.". Morrison reminds us that our value far exceeds that which we do or produce, but from a different lens.

If you have lost yourself in your career, now is the perfect time to rediscover who you are outside of what you do for work. Don't forget to check out more stories at #BOLD . Quotes

1. Whatever the work is, do it well—not for the boss but for yourself. 2. You make the job; it doesn't make you. 3. Your real life is with us, your family. 4. You are not the work you do; you are the person you are. Read the whole piece here.

A thesis statement: tells the reader how you will interpret the significance of the subject matter under discussion. is a road map for the paper; in other words, it tells the reader what to expect from the rest of the paper. directly answers the question asked of you. A thesis is an interpretation of a question or subject, not the subject itself.

A good thesis has two parts. It should tell what you plan to argue, and it should "telegraph" how you plan to argue—that is, what particular support for your claim is going where in your essay. Steps in Constructing a Thesis. First, analyze your primary sources. Look for tension, interest, ambiguity, controversy, and/or complication.

Despite Morrison valuing work, she finds more importance in her personal relationships and the value of home rather than work. Unlike Morrison's positive home life, Adkison's home life was something he wanted to escape from. Adikson emphasizes the idea that people who have an impact on our lives can come from unexpected places.

A thesis statement . . . Makes an argumentative assertion about a topic; it states the conclusions that you have reached about your topic. Makes a promise to the reader about the scope, purpose, and direction of your paper. Is focused and specific enough to be "proven" within the boundaries of your paper. Is generally located near the end ...

Whatever the work is, do it well—not for the boss but for yourself. 2. You make the job; it doesn't make you. 3. Your real life is with us, your family. 4. You are not the work you do; you are the person you are. I have worked for all sorts of people since then, geniuses and morons, quick-witted and dull, bighearted and narrow.

This activity is aligned to "The Work You Do, the Person You Are" by Toni Morrison, a personal essay covered in the Unit 3 Lesson Set of Pre-AP English 1. Each prompt in the activity explores ideas from the text, modeling for students an analysis of key elements such as historical and authorial context, plot, characterization, and author style.

Thesis. Your thesis is the central claim in your essay—your main insight or idea about your source or topic. Your thesis should appear early in an academic essay, followed by a logically constructed argument that supports this central claim. A strong thesis is arguable, which means a thoughtful reader could disagree with it and therefore ...

Step 1: Start with a question. You should come up with an initial thesis, sometimes called a working thesis, early in the writing process. As soon as you've decided on your essay topic, you need to work out what you want to say about it—a clear thesis will give your essay direction and structure.

1. Whatever the work is, do it well—not for the boss but for yourself. 2. You make the job; it doesn't make you. 3. Your real life is with us, your family. 4. You are not the work you do; you are the person you are. Morrison ends the article with the following: "I have worked for all sorts of people since then, geniuses and morons, quick ...

May You Be Proud of the Work You Do, the Person You Are, and the Difference You Make!: Thank You for All You Do! Inche 6x9 120 Page: Author: jou haki: Publisher: Independently Published, 2021: ISBN: 9798725907872: Length: 126 pages: Subjects

May You Be Proud of the Work You Do, the Person You Are, and the Difference You Make- Thank You: Thank You Appreciation Gift for Employees, Employee Gifts (Staff, Office and Work Gifts) - Motivational Quote Lined Notebook Journal, 7X10 Inch: Author: memo mado: Publisher: Independently Published, 2021: ISBN: 9798481787282:

not easily borne or endured; causing hardship. nuisance. anything that disturbs, endangers life, or is offensive. profound. coming from deep within one. dote. shower with love; show excessive affection for. eroded. worn away as by water or ice or wind.