Introduction to the Spanish Viceroyalties in the Americas

Juan Baptista Cuiris, image of Christ made with feathers, c. 1590-1600, 25.4 x 18.2 cm (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

“In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue.” These opening lines to a poem are frequently sung by schoolchildren across the United States to celebrate Columbus’s accidental landing on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola as he searched for passage to India. His voyage marked an important moment for both Europe and the Americas—expanding the known world on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean and ushering in an era of major transformations in the cultures and lives of people across the globe.

When the Spanish Crown learned of the promise of wealth offered by vast continents that had been previously unknown to Europeans, they sent forces to colonize the land, convert the Indigenous populations, and extract resources from their newly claimed territory. These new Spanish territories officially became known as viceroyalties, or lands ruled by viceroys who were second to—and a stand-in for—the Spanish king.

Girolamo Ruscelli, “Nveva Hispania tabvla nova,” engraved map of New Spain, 1599, 19 x 25 cm ( David Rumsey Historical Map Collection ). Note that at its height, the Viceroyalty of New Spain also included Central America, parts of the West Indies, the southwestern and central United States, Florida, and the Philippines.

Folding Screen with the Siege of Belgrade (front) and Hunting Scene (reverse), c. 1697-1701, Mexico, oil on wood, inlaid with mother-of-pearl, 229.9 x 275.8 cm (Brooklyn Museum)

The Viceroyalty of New Spain

Less than a decade after the Spanish conquistador (conqueror) Hernan Cortés and his men and Indigenous allies defeated the Mexica (Aztecs) at their capital city of Tenochtitlan in 1521, the first viceroyalty, New Spain, was officially created. Tenochtitlan was razed and then rebuilt as Mexico City, the capital of the viceroyalty. At its height, the viceroyalty of New Spain consisted of Mexico, much of Central America, parts of the West Indies, the southwestern and central United States, Florida, and the Philippines. The Manila Galleon trade connected the Philippines with Mexico, bringing goods such as folding screens, textiles, raw materials, and ceramics from around Asia to the American continent. Goods also flowed between the viceroyalty and Spain. Colonial Mexico’s cosmopolitanism was directly related to its central position within this network of goods and resources, as well as its multiethnic population. A biombo , or folding screen, in the Brooklyn Museum attests to this global network, with influences from Japanese screens, Mesoamerican shell-working traditions, and European prints and tapestries. Mexican independence from Spain was won in 1821.

The Viceroyalty of Peru

Lands governed by the Viceroyalty of Peru, c. 1650

The Viceroyalty of Peru was founded after Francisco Pizarro’s defeat of the Inka in 1534. Inspired by Cortés’s journey and conquest of Mexico, Pizarro had made his way south and inland, spurred on by the possibility of finding gold and other riches. Internal conflicts were destabilizing the Inka empire at the time, and these political rifts aided Pizarro in his overthrow. While the viceroyalty encompassed modern-day Peru, it also included much of the rest of South America (though the Portuguese gained control of what is today Brazil). Rather than build atop the Inka capital city of Cusco, the Spaniards decided to create a new capital city for Peru: Lima, which still serves as the country’s capital today.

In the eighteenth century, a burgeoning population, among other factors, led the Spanish to split the viceroyalty of Peru apart so that it could be governed more effectively. This move resulted in two new viceroyalties: New Granada and Río de la Plata. As in New Spain, independence movements here began in the early nineteenth century, with Peru achieving sovereignty in 1820.

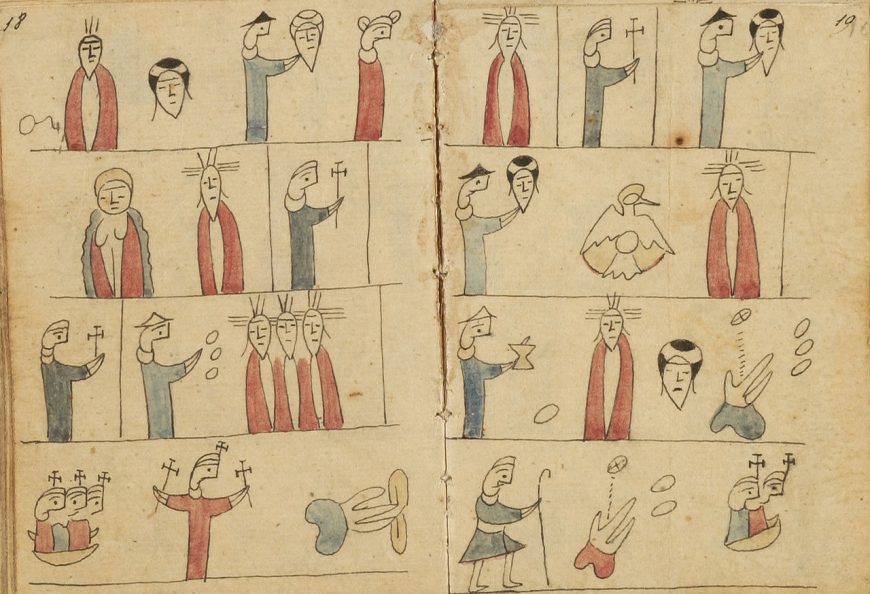

Pictorial Otomí catechism (pictorial prayer book), 1775-1825, Mexico, watercolor on paper, 8 x 6 cm ( Princeton University Library )

Evangelization in the Spanish Americas

Soon after the military and political conquests of the Mexica (Aztecs) and Inka, European missionaries began arriving in the Americas to begin the spiritual conquests of Indigenous peoples. In New Spain, the order of the Franciscans landed first (in 1523 and 1524), establishing centers for conversion and schools for Indigenous youths in the areas surrounding Mexico City. They were followed by the Dominicans and Augustinians , and by the Jesuits later in the sixteenth century. In Peru, the Dominicans and Jesuits arrived early on during evangelization.

Convento, San Agustín de Acolman, mid-16th century (photo: Steven Zucker , CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The spread of Christianity stimulated a massive religious building campaign across the Spanish Americas. One important type of religious structure was the convento . Conventos were large complexes that typically included living quarters for friars, a large open-air atrium where mass conversions took place, and a single-nave church. In this early period, the lack of a shared language often hindered communication between the clergy and the people, so artworks played a crucial role in getting the message out to potential converts. Certain images and objects (including portable altars, atrial crosses , frescoes, illustrated catechisms or religious instruction books, prayer books, and processional sculpture) were crafted specifically to teach new, Indigenous Christians about Biblical narratives.

Aztec deities, Bernardino de Sahagún and collaborators, General History of the Things of New Spain , also called the Florentine Codex , vol. 1, 1575-1577, watercolor, paper, contemporary vellum Spanish binding, open (approx.): 32 x 43 cm, closed (approx.): 32 x 22 x 5 cm (Medicea Laurenziana Library, Florence, Italy)

This explosion of visual material created a need for artists. In the sixteenth century, the vast majority of artists and laborers were Indigenous, though we often do not have the specific names of those who created these works. At some of the conventos , missionaries established schools to train Indigenous boys in European artistic conventions. One of the most famous schools was at the convento of Santa Cruz in Tlatelolco in Mexico City, where the Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún, in collaboration with Indigenous artists, created the encyclopedic text known today as the Florentine Codex .

Church of Santo Domingo and Qorikancha, Cusco, Peru (photo: Håkan Svensson , CC BY-SA 3.0)

Strategies of Dominance in the Early Colonial Period

Spanish churches were often built on top of Indigenous temples and shrines, sometimes re-using stones for the new structure. A well-known example is the Church of Santo Domingo in Cusco, built atop the Inka Qorikancha (or Golden Enclosure). You can still see walls of the Qorikancha below the church.

Great Mosque of Córdoba, Córdoba, Spain, begun 786, cathedral added 16th century (photo: Toni Castillo Quero , CC BY-SA 2.0)

This practice of building on previous structures and reusing materials signaled Spanish dominance and power. It had already been a strategy used by Spaniards during the so-called “Reconquest,” or reconquista , of the Iberian (Spanish) Peninsula from its previous Muslim rulers. In southern Spain, for instance, a church was built directly inside the Great Mosque of Córdoba during this period. The reconquista ended the same year Columbus landed in the Americas, and so it was on the minds of Spaniards as they lay claim to the lands, resources, and peoples there. Some sixteenth-century authors even referred to Mesoamerican religious structures as mosques, revealing the pervasiveness of the Eurocentric conquest attitude they brought with them.

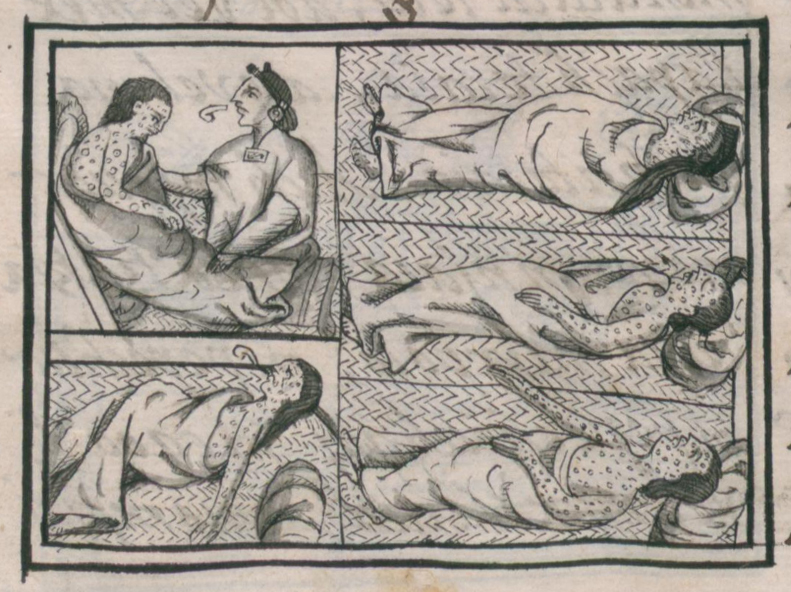

Throughout the sixteenth century, terrible epidemics and the cruel labor practices of the encomienda (Spanish forced labor) system resulted in mass casualties that devastated Indigenous populations throughout the Americas. Encomiendas established throughout these territories placed Indigenous peoples under the authority of Spaniards. While the goal of the system was to have Spanish lords educate and protect those entrusted to them, in reality it was closer to a form of enslavement. Millions of people died, and with these losses certain traditions were eradicated or significantly altered.

Title page from Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, The First New Chronicle and Good Government, c. 1615 (The Royal Danish Library, Copenhagen)

Nevertheless, this chaotic time period also witnessed an incredible flourishing of artistic and architectural production that demonstrates the seismic shifts and cultural negotiations that were underway in the Americas. Despite being reduced in number, many Indigenous peoples adapted and transformed European visual vocabularies to suit their own needs and to help them navigate the new social order. In New Spain and the Andes, we have many surviving documents, lienzos , and other illustrations that reveal how Indigenous groups attempted to reclaim lands taken from them or to record historical genealogies to demonstrate their own elite heritage. One famous example is a 1200-page letter to the king of Spain written by Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala , an Indigenous Andean whose goal was to record the abuses the Indigenous population suffered at the hands of Spanish colonial administration. Guaman Poma also used the opportunity to highlight his own genealogy and claims to nobility.

Saint John the Evangelist , 16th century, featherwork (Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico City)

Talking about Viceregal Art

How do we talk about viceregal art more specifically? What terms do we use to describe this complex time period and geographic region? Scholars have used a variety of labels to describe the art and architecture of the Spanish viceroyalties, some of which are problematic because they position European art as being superior or better and viceregal art as derivative and inferior.

Some common terms that you might see are “colonial,” “viceregal,” “hybrid,” or “ tequitqui .” “Colonial” refers to the Spanish colonies, and is often used interchangeably with “viceregal.” However, some scholars prefer the term “colonial” because it highlights the process of colonization and occupation of the parts of the Americas by a foreign power. “Hybrid” and “ tequitqui” are two of many terms that are used to describe artworks that display the mixing or juxtaposition of Indigenous and European styles, subjects, or motifs. Yet these terms are also inadequate to a degree because they assume that hybridity is always visible and that European and Indigenous styles are always “pure.”

Applying terms used to characterize early modern European art (Renaissance, Baroque, or Neoclassical, for instance) can be similarly problematic. A colonial Latin American church or a painting might display several styles, with the result looking different from anything we might see in Spain, Italy, or France. A Mexican featherwork , for example, might borrow its subject from a Flemish print and display shading and modeling consistent with classicizing Renaissance painting, but it is made entirely of feathers—how do we categorize such an artwork?

It is important that we not view Spanish colonial art as completely breaking with the traditions of the pre-Hispanic past, as unoriginal, or as lacking great artists. The essays and videos found here reveal the innovation, adaptation, and negotiation of traditions from around the globe, and speak to the dynamic nature of the Americas in the early modern period.

Bibliography

Arts of the Spanish Americas, 1550–1850 on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Vistas: Visual Culture in Spanish America, 1520-1820

Spanish Colonial and 19th century art at LACMA

The Garrett Mesoamerican Manuscript Collection at Princeton University Library

Girolamo Ruscelli’s “Nveva Hispania tabvla nova” map in the David Rumsey Historical Map Collection

The Florentine Codex at the World Digital Library

Juan Baptista Cuiris’s featherwork at the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Learn more about the legacy of the Reconquest in Latin America and Columbus’ Landing and Erasing Native Resistance from Unsettling Journeys

Cite this page

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

6 Central America under Spanish Colonial Rule

Stephen Webre, Professor Emeritus of History, Louisiana Tech University

- Published: 08 September 2021

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The Central American isthmus was under Spanish colonial rule for approximately three centuries ( ca. 1502–1821). Known interchangeably as the kingdom, audiencia, or captaincy-general of Guatemala, the region occupied territory that would later become the republics of Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica, plus the state of Chiapas, Mexico. Unlike New Spain and Peru, Central America did not possess great mineral wealth, but its location between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans made it an important strategic asset. As did other parts of Spain’s overseas empire, Central America presented challenges of governance and defense. During the Habsburg era (to 1700), the colonial state took shape organically, drawing upon existing peninsular models within a framework of collaboration between the monarchy and local allies, including colonial and indigenous elites and the Roman Catholic Church. This system was not elegant, but it worked as long as authorities in Spain were willing to accept a degree of corruption and inefficiency in public administration. Under the Bourbons (1700–1821), Spain’s new rulers undertook an ambitious program of reforms meant to correct the weaknesses of the old system, while promoting economic growth, strengthening defenses, and enhancing revenues. Judged by their own standards, the Bourbon Reforms registered some successes, but they also bred disaffection. The eventual cost became apparent when the traditional allegiances forged in the Habsburg era dissolved under the pressure of constant warfare, and especially the 1808 Napoleonic invasion of Spain, which precipitated the empire-wide independence crisis.

On a scale without precedent in its day, the Spanish Empire sought to unify under its rule a widely scattered assortment of Iberian settlements and native communities. Separated by forbidding terrain and vast expanses of ocean, these outposts of colonial rule were held together by a precarious web of legal traditions, ideological assumptions, and primitive technologies of communication and transportation. Reliance upon sailing vessels and handwritten correspondence made it difficult for colonial authorities to maintain effective supervision over their new possessions. 1 Over time an administrative structure emerged that adjusted adequately, if not brilliantly, to the demands of a worldwide empire. This institutional construct exhibited many characteristics of the modern nation-state then taking form in contemporary Europe. Like its metropolitan counterpart, its ability to acquire and defend territorial control, extract revenue, and secure monopolies over the administration of justice and exercise of violence was limited. It may not be far-fetched to apply the term “state” to the improvised collection of institutions and practices by which Spain sought to exercise domination in its global holdings, but, given the distance that separated its agents from the ultimate center of authority and the exploitative nature of the enterprise as a whole, “colonial state” may be more appropriate.

Early studies of Spanish colonial administration tended to focus on legal precepts and formal institutions. 2 In what might be called the “sociological” approach, more recent efforts have sought to examine actual human behavior in specific historical contexts. Considering the merits of both traditional and innovative approaches, historian John Lynch has suggested that the gap between the two may not be as great as it seems, arguing that “it may be that the term ‘colonial state’ sounds more impressive than ‘colonial institutions’, and we are simply studying the same thing under a different name.” 3 This chapter acknowledges the pertinence of Lynch’s suggestion. Although it opts to employ the more current terminology, it is heavily indebted to the work of scholars laboring in both traditions. 4

The traditional chronological frame of reference for discussions of the colonial era in Central America is the period between 1502 and 1821, that is, between the initial contact of European and Native American and the date conventionally cited to mark national independence from Spain. In geographical terms, colonial Central America typically refers to the area occupied by the modern republics of Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica, plus the Mexican state of Chiapas. Despite proximity and some similarity in historical experience, it is not generally understood to include Panama, which in the colonial era was more closely tied to Peru than to its northern neighbors. In studies of colonial Central America, Panama typically enters only when directly relevant to a larger issue, as does Belize, a former British colony sometimes thought of as Central American and sometimes as West Indian. 5

During the Spanish regime the area now called Central America was known as Guatemala and might be referred to as the “audiencia of Guatemala,” the “captaincy-general of Guatemala,” or the “kingdom of Guatemala.” Whatever the formal meaning of these terms may have been in the colonial era, writers since then have treated them as synonymous and interchangeable. The term “Guatemala” applied as well to the smaller territory that corresponded roughly to the modern republics of Guatemala and El Salvador combined. Guatemala was also the name applied to the largest and most important city in the region. The most populous and most culturally complex of the Central American provinces, Guatemala was also the richest in surviving historical documentation. 6 For that reason, it has been the most frequently studied by historians, anthropologists, geographers, and other specialists and it figures more prominently than its isthmian neighbors in the narrative and analysis that follow.

To begin, one might ask who the subjects of the colonial state in Central America were. In 1502, when his fourth voyage carried him along the isthmus’s sparsely settled Caribbean coast, the land that Christopher Columbus touched upon was already a cultural frontier. To the west and north, its Mesoamerican inhabitants were largely Mayas, but they included some Nahua-speakers as well. To the east and south were peoples of South American heritage. Whatever its origin, at the time of contact most of the region’s population dwelt in the interior highlands and along the ample Pacific coastal plain, a pattern that continued for much time to come. Estimates of the number of native inhabitants living in Central America at the moment of initial contact with Europeans are numerous and wide-ranging. Counts collected and analyzed by W. George Lovell and Christopher H. Lutz range from a high of perhaps 13,500,000, to a low of approximately 800,000. For their part Lovell and Lutz prefer a number in the vicinity of 5,000,000. 7 Such figures remain controversial, as seen, for example, in Juan Carlos Solórzano Fonseca’s defense of century-old estimates for Costa Rica in preference to more recent and higher numbers. 8

In terms of human resources (from the colonial state’s point of view, i.e., tax base and labor supply) the size of the region’s population is important to know, but also important are the rate and direction of demographic change and the social realities that lie behind the numbers. As in other Spanish American overseas possessions, the initial encounter was followed closely by a massive population decline with notable impact on the formation of colonial societies. Once again, precise data are difficult to come by. Lovell and Lutz propose a native population loss between contact and the mid-seventeenth century of as much as 80 to 90 percent, a figure consistent with estimates reported for other Spanish overseas possessions. 9 Most authorities attribute this hecatomb to the introduction of previously unknown Old World diseases, but frequently mentioned as contributing factors also are losses due to warfare, forced migration, and the impact of coerced labor. Some scholars report that as many as 500,000 Indians may have perished from Nicaragua alone as a result of capture and shipment to slave markets in Panama and Peru. This figure is widely contested, among others by Patrick S. Werner and Frederick W. Lange, who demonstrate convincingly that such a total would far exceed the transport capacity of the ships available in Pacific ports to carry human cargos of the size suggested. 10

The rapid decline of the native population during the first century of Spanish rule had economic and social effects. For one thing, it caused the abandonment of large expanses of previously productive agricultural land, which became available for grants to Spanish settlers. It also reduced the labor supply, prompting colonial authorities to promote measures for stricter control of remaining Indigenous communities. Meanwhile, Spanish landowners dedicated their new properties to labor-extensive activities, such as stock-raising and large-scale production of marketable commodities. These shifts accompanied what might be called a “biological revolution,” which among other things brought the introduction of new crops, such as wheat and sugar cane, and new domesticated animals, such as cattle, sheep, horses, mules, and chickens. 11 They also involved a complex scrambling of human bloodlines.

As the native population of Central America shrank, the nonnative population expanded, due to both natural increase and immigration by Spaniards and enslaved Africans. Mostly young unaccompanied males, Spanish newcomers sought companionship among Indigenous and Afro-descendant women. Children born of unions between Spaniards and Indians were known as mestizos, and the offspring of Spaniards and Africans were called mulatos . Spanish colonial authorities saw racially discriminatory policies as both appropriate and desirable, but, in a world in which miscegenation was normalized and widely practiced, the task of identifying individuals by race became more complicated with each passing generation. At one point imperial policymakers recognized and documented as many as sixty-four specific degrees of race mixture, but for practical purposes colonial speakers collapsed all these categories into a few general labels, such as casta and pardo . An ethnic label with a history peculiar to Central America is ladino . Like casta and pardo, ladino was and remains more a cultural designation than a biological one. In the early colonial era it meant simply an Indian who spoke Spanish, but over time it came to apply to any Westernized person—that is, to any person not unambiguously identifiable as either Spanish or Indigenous. 12

It is generally thought that native population reached its nadir and began to recover in the early seventeenth century, at which time demographic patterns familiar to later observers of Central America began to take definitive shape. Allowing for reporting errors remarked by Lovell and Lutz, a count dating from 1778 may offer a general glimpse of the isthmian population as it stood near the close of the colonial period. Of a total population for Central America of possibly 892,652, persons classified as Indians numbered 479,273, or about 54 percent. Although by far the largest component of the colonial population, the monarchy’s Indigenous subjects had evidently recovered only a fraction of the losses they had experienced in the more than two centuries since the conquest. The next most numerous category in the report was ladinos, who numbered 297,400, or about 31 percent, followed by Spaniards, whose numbers totaled 133,979, or 15 percent. 13

As informative as these numbers may appear, the reader should be aware that there are significant reporting gaps. For example, it would be good to know how many of the “Spaniards” appearing on the roll were peninsulars (Spaniards born in Spain), and how many were creoles (Spaniards born in the Americas). More interesting yet would be to know how many creoles were, in fact, not pure-blooded Europeans at all, but rather ladinos, who exploited possession of certain outward markers of elite status, such as light skin, education, or material wealth, to mask their humbler origins. 14 The absence of a separate count for enslaved persons, or for persons of African descent in general, may be evidence of the effectiveness of similar “whitening” strategies employed by those particular subaltern groups. Long marginalized, denied, or simply ignored in national historiographies, colonial Central America’s significant Afro-descendant population began to receive serious scholarly attention only in the late twentieth century. Since what might be called the “discovery” of African influence, important work has been done on all the Central American countries. 15 Even for Costa Rica, a country with a strong reputation for historical scholarship but also a deeply rooted national myth of “Whiteness,” scholars such as genealogist Mauricio Meléndez Obando and historian K. Russell Lohse have documented the extent to which even the most prominent of elite families numbered enslaved Africans among their ancestors. 16 Considering the 1778 census data in light of increased knowledge and understanding of the African experience in colonial Central America, it seems reasonable to imagine that by the final decades of the colonial period the isthmus’s Black and mulato population had been largely absorbed into the ladino category, or possibly even that of creole Spaniards. As to the Afro-descendant inhabitants of the Caribbean coast, it is unlikely that imperial authorities took them into account at all.

Colonial Cities

Among other things, instituting Spanish rule in Central America meant founding cities, which if successful became platforms for defense, administration, production, exchange, and distribution, activities essential to the formation and maintenance of the colonial state. Among the earliest cities to be founded were Panama City (1519); Granada and León, Nicaragua (both 1524); San Salvador and San Miguel, El Salvador (1525 and 1530); San Pedro Sula and Comayagua, Honduras (1536 and 1537); and Ciudad Real, Chiapas (1538), later known as San Cristóbal de Las Casas. Due to warfare, earthquakes, and other hazards, many of these newly established cities did not remain in their original locations. This was conspicuously the case of Santiago de Guatemala, which, despite repeated misfortunes, over time became Central America’s largest and most important urban center.

The conqueror Pedro de Alvarado established Santiago in 1524, choosing for a site Iximché, the principal city of his Kaqchikel Maya allies. The first Spanish inhabitants promptly abandoned the site, however, when their disillusioned hosts rose up against them. 17 In 1527, after roaming for three years throughout the central and western highlands, Alvarado’s followers finally resettled in the valley of Almolonga, located on the lower slopes of Agua Volcano near the Indigenous settlement later known as Ciudad Vieja. Disaster soon struck again, however. In 1541, torrential rains loosened rocks and earth on the volcano’s slopes, producing a massive landslide that destroyed Santiago de Guatemala, left many of its inhabitants dead or homeless, and induced the survivors to relocate themselves once again. This time the move was to a valley called Panchoy, where the new Santiago was constructed and where it remained, grew, and prospered until 1773, when a series of earthquakes left it so badly damaged that royal authorities ordered yet another removal, this time to the valley of La Ermita, approximately 45 kilometers from the remains of Santiago. 18 Named Nueva Guatemala de la Asunción, the new establishment eventually became the national capital known as Guatemala City. Many of Santiago’s inhabitants joined the exodus to the new city, but others sought opportunity elsewhere, especially in Quetzaltenango, a K’iche’ Maya town located in the western highlands. 19 Those who chose not to move stayed in place among the ruins of once-impressive baroque structures and worked to rebuild their lives and properties. 20 By the mid-twentieth century the old city gained new importance as the tourism center called Antigua Guatemala, formally recognized by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) as a World Heritage Site. 21

When it came to building a city, Renaissance-era Spaniards had a clear mental image of what one should look like. 22 Except in ports and mining centers, which tended to grow organically, streets in Spanish American cities were laid out perpendicularly, creating rectangular spaces to be distributed to settlers as solares (house sites) for residential use and the tending of household gardens and domestic animals. At the center of the grid was the plaza mayor (main square), an ample public arena for ceremonies, celebrations, markets, and recreational activities. 23 Encircling the plaza were the parish church, the casas reales (government house), and the cabildo (town hall), facilities whose presence emphasized the central space’s importance to colonial life. Nonetheless, studies of colonial Santiago residential patterns by David L. Jickling challenge the common assertion that elite householders gathered purposely around the plaza and its immediate vicinity. 24

If there was an accepted model for laying out a city, there was also a recognized scheme for governing one, and, as Helen Nader points out, any adult Castilian male would have been familiar with it. 25 With historic roots running back to the Middle Ages and perhaps even to the Roman era, the Spanish municipal council was known variously as the concejo or the ayuntamiento, but perhaps most often as the cabildo, a term that might refer to the body itself, to the building in which it met, or to any formal assembly of its members. As traditionally organized, a cabildo had two components, the justicia and the regimiento . Depending upon the size and importance of the municipality, the justicia consisted of either one or two alcaldes ordinarios (municipal magistrates) and was a court of first instance for civil and criminal matters arising within its jurisdiction. Once again varying with the size and importance of the municipality, the regimiento was made up of from four to twenty or more aldermen known as regidores, who were responsible for routine matters of municipal governance, such as public order; street maintenance; water supply; and oversight of prices, weights, and measures in local markets. 26

Alcaldes ordinarios were elected by the regimiento for one-year terms, but the process for choosing regidores varied by time and place. In smaller places, they might be elected, also for one-year terms, either by the outgoing aldermen or by the body of Spanish settlers. In some cities that over time grew in population, wealth, and importance, methods of filling vacant positions might change. In Santiago de Guatemala, for example, a major urban center for which archival records survive in abundance, by the middle of the sixteenth century the Spanish monarchy began to grant petitions for direct appointments for life. By the 1590s, municipal offices were being sold at public auction, again for the life of the purchaser. These innovations had the effect of consolidating a powerful and influential municipal aristocracy, but, as studies by Stephen Webre and José Manuel Santos Pérez have revealed, the closed, hereditary, creole landowning oligarchies described in established historiography did not exist, at least not everywhere. In Santiago throughout the city’s history, the municipal council was dominated by peninsula-born Spaniards, whose fortunes originated not in landholding but in trade, finance, transport, and similar activities. 27

Regardless of their specific ethnic origins, the native peoples of Central America had much in common. For example, they were all agriculturalists, dependent for their livelihoods on the production of domesticated plants and animals for both market and subsistence. For this reason, they tended to live not in densely nucleated settlements, as the Spanish did, but spread out through the countryside in proximity to their milpas (cultivated fields). Although rational from the Indigenous point of view, this preference poorly served the needs of imperial agents, whose task was to impose social control, tribute payment, and Christian belief on the monarchy’s newest subjects. Promoted by religious leaders such as Francisco Marroquín and Bartolomé de Las Casas, beginning in the 1540s the solution adopted was to relocate the rural population to permanent towns, known as congregaciones or reducciones . In implementing the new policy, Roman Catholic missionaries were assisted by royal magistrates and native community leaders. 28 Many of the inhabitants of the newly created towns adapted well to their environments, and their towns survived as majority Indigenous communities, while others either disappeared or transformed into centers of ladino population. 29

If urbanization promoted imperial rule by shaping Spanish settlement patterns, the congregation campaign did much the same for the native landscape. Like their Spanish and ladino counterparts, native towns were established as semiautonomous municipalities governed by cabildos composed of alcaldes ordinarios and regidores. Due to a paucity of records, these important bodies are little studied, but Kaqchikel historian Héctor Concohá has obtained valuable insight by probing the internal politics of his native town of San Juan Sacatepéquez. 30

The formation of reductions represented a major alteration in the traditional Indigenous way of life, one that, along with other major changes, native peoples did not always accept easily. Forms of resistance observed throughout the colonial period ranged from violent uprisings to such passive responses as flight to neighboring unsettled areas or clandestine preservation of precontact religious beliefs, rituals, and lines of community authority. Although significant episodes of armed resistance were not as frequent as one might imagine, historian Severo Martínez Peláez has convincingly challenged the commonly held misconception that in general Central American Indians accepted colonial domination peaceably. 31 On the other hand, colonial-era resistance movements cannot generally be described as revolutionary. Rebellions with religious content tended to fuse together elements of both European and native belief systems, and even those uprisings that occurred in the context of the independence movements of the early nineteenth century focused more on the pursuit of localized objectives than on sweeping social or political change. 32

Land and Labor

As in any agrarian society, land and labor were major issues in colonial Central America.

Due in part to native population decline during the sixteenth century, land was a relatively abundant resource throughout Central America, although some provinces offered more ready access to persons of modest means than did others. Easy availability of land in Costa Rica’s central valley, for example, has been advanced in support of that country’s myth of smallholding agrarian democracy, an argument critiqued by such scholars as Elizabeth Fonseca and Lowell Gudmundson. 33

Given the matter’s fundamental importance, the colonial state took an active interest in questions of land distribution. 34 To ensure that the people in the recently established Indigenous towns were able to feed themselves and meet their tribute obligations, new reduction villages, once they were formed, were assigned lands to be held in common. As part of Spanish settlement policy, non-Indian towns were granted lands as well. Some such grants were intended as ejidos, property held in common for use as pasturage and other collective needs. Other holdings served as propios (i.e., as sources of revenue for municipal governments). Both natives and Europeans had traditions of communal property holding, but Spaniards’ interest lay more in entrepreneurial ventures than in mere subsistence, so they sought private property as well. Individual title to land could be acquired by merced , an outright royal concession, or by composición , a transaction that involved payment of a fee to regularize a title that might otherwise be questionable. After the 1590s, as the Spanish monarchy experienced increasing financial difficulties, composition became the favored method of conveying title to significant tracts of land.

Some private ownership of land occurred in Indian pueblos also, but communal possession was by far more common. A good deal of land was held by lay religious brotherhoods known as cofradías, or confraternities, which employed much of it in stock-raising. Confraternity wealth served to finance cult activities associated with the organization’s patron saint and also for relief of members and their families in the event of illness, death, or other mishap. Indigenous patterns of land use seemed irrational to many Spaniards, who reported uncultivated tracts as abandoned in an effort to acquire them through composition. During the seventeenth century when the native population bottomed out, land may have seemed a surplus commodity, but later as Central America’s Indian communities began to experience a demographic revival, pressure on available resources grew as well, leading to frequent litigation over boundaries, titles, and other issues associated with land ownership. Records of such disputes can be valuable documentation for students of social history. 35

Historian Severo Martínez Peláez and other scholars have sought the origins of Central America’s characteristic patterns of unequal land distribution in the colonial period. Although extensive landed estates did exist, especially in the western highlands and along the Pacific coast, the typical pattern appears to have been less reminiscent of the giant haciendas of northern New Spain described by François Chevalier and better represented by the mixture of private and common, small, medium, and large holdings identified by William B. Taylor in colonial Oaxaca. 36 The so-called mestizo agrarian blockade proposed by Severo Martínez Peláez as one of the factors favoring the emergence of latifundia in colonial Central America appears to have little support in the documentary record. 37

In colonial Central America, land was of little use without the hands to work it. Spanish elites sought constantly for ways to access Indian labor at the lowest cost possible. 38 Even before the first European invaders entered the isthmian provinces, the Spanish monarchy had outlawed native slavery. Nonetheless, conquerors and settlers found pretexts to continue the practice, which remained common in the early years. A contemporary institution was the encomienda , under which specific Indigenous communities were assigned to favored Spaniards, who profited from their tribute payments and coerced labor. More than a labor institution, the encomienda was also a means for officials in Spain to reward loyal service and to establish the king’s authority, all at minimal expense to the royal treasury. In return for the material benefits received, encomenderos , as the beneficiaries of encomienda grants were called, were expected to provide military service, administer justice, and promote the Christianization of their charges. Technically, encomienda Indians were not slaves but rather free vassals of the monarch. On a daily basis, however, the difference between these two conditions may have been difficult for their objects to appreciate. Abuses were common and well documented.

Promoted by the influential Dominican friar and defender of native rights Bartolomé de Las Casas, the New Laws issued at Barcelona in 1542 intended a major reform of native labor systems in the Spanish American Empire. Indian slavery was definitively forbidden and all remaining enslaved Indigenous persons were ordered freed. Also, the labor obligations of encomienda Indians were terminated. To meet the continued demand for native labor, the colonial state instituted a system known as repartimiento (distribution), under which native communities were each required to provide a certain number of workers on a rotating basis. Public functionaries would then apportion labor to Spanish petitioners, presumably according to need. Repartimiento differed from encomienda in that it took work assignments out of private hands and also ended the ecomenderos’ monopoly claim to the available workforce. Also, the new system contained measures for the good treatment of draft laborers and required payment for work performed. In some colonies, such as New Spain, by the middle of the seventeenth century the repartimiento system gave way to free wage labor at least in agriculture, but in Central America it endured until the end of the colonial period, and in one form or another even beyond that.

Whenever issues concerning Indian labor were debated, Spanish settlers were quick to make the argument that Indians were “lazy,” and that they would not plant crops even for their own subsistence except under coercion. Allegedly to prevent widespread starvation, royal authorities in Guatemala instituted a new office known as the juez de milpas (overseer of planting), whose task it was to conduct inspections of Indigenous communities to ensure that maize production quotas were being met. 39 Apparently unique in Spanish America, the jueces de milpas were the objects of repeated controversy. Citing the burden placed on Indigenous leaders to fulfill quotas while providing hospitality to visiting officials and their entourages, critics denounced the post as abusive. The monarchy outlawed the practice at least ten times between 1581 and 1681. In the end, however, as a source of public employment for needy Spaniards it was too beneficial to be given up. 40

Institutions of Colonial Rule

The encomienda, congregation, and municipal institutions in general promoted the implantation of Spanish rule on a local level, but institutions with more extensive jurisdictions were needed as well. The outlines of the later territorial organization of Central America began to emerge as leaders of the conquest asserted claims to govern provinces that largely prefigured the modern republics. The first governor of Guatemala, for example, was the conqueror Pedro de Alvarado (1527–1541). In Nicaragua, Pedrarias Dávila (1527–1531) held command, and after him his son-in-law Rodrigo de Contreras (1534–1544). Possessed of gold and silver deposits considered significant at the time, Honduras was governed briefly by a royal appointee, Diego López de Salcedo (1525–1530), but soon found itself the object of competing Spanish ambitions. In 1539, Pedro de Alvarado surrendered his claim to Honduras to Francisco de Montejo, conqueror of Yucatan, in exchange for the latter’s interest in Chiapas. Meanwhile, Costa Rica was late to come under Spanish rule. When it finally did so in the 1560s, Juan Vázquez de Coronado asserted his family’s claim to the adelantazgo (hereditary governorship). Although more in form than in substance, the monarchy continued to recognize the Coronados’ right to the title for generations to come. 41

Early governors possessed ample powers, including the authority to make land grants and award encomiendas. The latter were particularly important in the political calculations of the early colony. 42 The provision of certain public services by individual encomenderos at Indigenous rather than royal expense helped to compensate for the colonial state’s inability to maintain an autonomous bureaucracy of adequate size, training, and material resources. Aware of the role their cooperation played in sustaining colonial rule, the conquest veterans, first settlers, and other Spaniards who made up early Central America’s dominant families repeatedly petitioned the monarchy for rewards and favors, including supplementary grants of income, appointments to remunerative public offices, and especially perpetual inheritance of encomiendas, an appeal that royal authorities consistently rejected. Wary of colonial ambition, the Castilian monarchy sought every opportunity to limit the political influence of local elites. During the sixteenth century, the monarchy implemented significant policy changes, but the fact is that the colonial state never possessed the human or material resources needed to establish unquestioned hegemony. Throughout the colonial period, for the state to perform its essential functions it remained dependent upon the voluntary collaboration of elites. 43

A major step in the effort to strengthen the monarchy’s grip on the new territories was the creation of royal tribunals known as audiencias . These bodies possessed executive, legislative, and judicial powers and were the supreme authorities in the districts they governed. Each audiencia consisted of a president and a varying number of oidores (judges). In order to insulate against excessive local elite influence, the monarchy drew audiencia personnel from the ranks of career civil servants, holders of university degrees, and only rarely of colonial birth. Like other officeholders in the Spanish Indies, presidents and oidores were all subject to both regular and extraordinary performance reviews, known, respectively, as residencias and visitas .

The first audiencia to be established in Spain’s overseas possessions was at Santo Domingo in 1511, followed by Mexico in 1528, and Panama in 1538. In 1542, a provision of the New Laws authorized two additional tribunals, one at Lima and one to govern Central America. Originally to be called the audiencia of Los Confines, the new Central American high court initially convened at Gracias a Dios, a mining center in western Honduras. 44 That location proved inconvenient, and in 1549 the audiencia moved its seat to Santiago de Guatemala, after which it became known as the audiencia of Guatemala. The body remained at Santiago until the earthquakes of 1773, when the colonial capital relocated to Guatemala City.

The Spanish monarchy recognized the growing importance of the audiencia presidency by assigning its occupant additional titles. In 1560, designation as governor-general of Guatemala acknowledged the president’s sweeping executive authority throughout the Central American provinces, and 1609 saw the addition of the military grade of captain-general. Therefore, by the early seventeenth century the chief colonial magistrate of Central America bore three lofty titles simultaneously and might be referred to by any or all of them. Despite the multiple honorifics, it was not possible for the audiencia president to attend personally to every matter that arose in Spanish Central America. To address that need, beginning in the 1540s the monarchy introduced a corps of district magistrates, known variously as governors, alcaldes mayores, or corregidores . 45

According to an administrative handbook compiled in the 1640s, at that time the audiencia of Guatemala was divided into four governorships, eight alcaldías mayores, and sixteen corregimientos. 46 In general, governors and alcaldes mayores received much higher salaries than corregidores, were appointed by the monarch, and were more likely to govern districts with significant resources, substantial non-Indian populations, or other distinguishing characteristics. By contrast, corregidores were usually assigned to heavily Indigenous areas. They were poorly paid, but, because they were named by the audiencia presidents rather than by authorities in Spain, their positions were more accessible to employment-seeking local elites, who pursued them energetically. Differences in pay and modes of appointment suggest a hierarchical relationship more apparent than real. In fact, there was no difference in the authority, responsibilities, or place in the chain of command of governors, alcaldes mayores, or corregidores.

A notable exception to the system described here was the jurisdiction known as the Corregimiento del Valle de Guatemala, which included the region immediately surrounding the city of Santiago. Governed on a rotating basis by the cabildo’s two alcaldes ordinarios, the Valle de Guatemala was in reality a complex of seven smaller districts, all called “valleys” as well. With approximately eighty Indigenous communities, when the city of Santiago itself was included the Valle was home in the late seventeenth century to perhaps as many as 100,000 residents of all social levels. The district was a major source of income and the municipality’s claim to it was frequently contested. On several occasions, colonial officials recommended that the arrangement be terminated, which was ultimately done in 1753. 47

Church and State

Intimately involved in constructing the colonial state was the Roman Catholic Church, whose institutional presence was felt from the beginning. Ecclesiastical authorities maintained their own bureaucracy parallel to, and frequently entangled with, that of civil government. During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Spanish monarchy treated the Church as an ally essential to its imperial project, but by the closing decades of the colonial period royal officials came to see it more as rival than as partner. 48

The basic unit of church administration was the parish, known in missionary areas by the term doctrina . Parishes in turn were organized into dioceses, and each diocese was presided over by a bishop. Under a long-standing traditional arrangement known as the patronato real (royal patronage), bishops and other senior ecclesiastical personnel were nominated by the king and submitted for papal approval, which was rarely withheld. During the colonial period there were four dioceses in Central America. Beginning with León, Nicaragua (1531), these included Trujillo, Honduras (1531, transferred to Comayagua in 1571); Santiago de Guatemala (1534); and Ciudad Real, Chiapas (1538). Similar to what occurred in colonial civil government, these divisions foreshadowed modern national boundaries, although what eventually became the republic of El Salvador did not have its own bishop until 1842 and Costa Rica not until 1850, in both cases well after independence from Spain. Initially, all the Central American dioceses were suffragan to the archbishop of Mexico, a subordinate relationship that lasted until 1743, when the diocese of Guatemala was itself elevated to metropolitan (archdiocesan) status.

Parishes were administered by curas (pastors), who, depending upon circumstances, might be seculares (diocesan clergy) or religiosos (members of religious orders). The latter was more likely to be so in mission doctrinas, where authorities tended to favor the assignment of members of religious orders, whom they perceived to be more learned, better disciplined, and more devout than their secular counterparts. Although a number of religious orders were present in colonial Central America, only three were heavily involved in evangelization efforts. Most numerous were the Franciscans, who maintained mission settlements in the central Guatemalan highlands, Honduras, Nicaragua, and what is now El Salvador. Franciscan friars were the only missionaries active in Costa Rica. For their part, Dominican friars dominated the missions in Chiapas and northern Guatemala, especially in Verapaz, subject of a notable experiment in “peaceful” conquest conceived by Bartolomé de Las Casas. 49 Finally, the Order of Mercy controlled the western highlands of Guatemala and also maintained a significant presence in Honduras and Nicaragua. 50

Pastoral work was a departure for the order clergy, who in Europe were more accustomed to the contemplative routine of monastic life. Royal authorities anticipated that, once active evangelization was completed, the friars would be reassigned and their doctrinas secularized (i.e., transferred to diocesan control). Because order clergy operated under the direction of their own superiors outside episcopal supervision, both civil and ecclesiastical authorities considered successful completion of the secularization process to be vital to strengthening the colonial state. As was to be expected, missionary clergy resisted secularization, but at the same time secular priests had little interest in pastoral service in poor rural communities far from the comforts of city life and for which, in addition, they lacked the needed skills in Indigenous languages. As a consequence, the religious orders remained dominant in many areas until after independence, when they were suppressed by anticlerical Liberal regimes.

Apart from missionary work, the Church fulfilled many other purposes of the colonial state, providing divine reassurance in times of personal misfortune as well as times of epidemics, earthquakes, and other calamities. Clergy also drew upon the Church’s moral authority to urge proper behavior and reinforce ideological conformity. Such tasks may be associated in popular imagination with the Holy Office of the Inquisition, but that body had no tribunal in Central America and local agents typically concerned themselves with such routine matters as complaints of sexual misconduct by clergymen and inspections of arriving vessels for contraband reading material. 51 Prosecutions for witchcraft did occur, and historian Martha Few has made good use of Mexico City tribunal records to study Central American women’s involvement in illicit ritual activities. 52