ReviseSociology

A level sociology revision – education, families, research methods, crime and deviance and more!

Structured Interviews in Social Research

Structured interviews are a standardised way of collecting data typically using closed, pre-coded surveys.

Table of Contents

Last Updated on September 26, 2023 by Karl Thompson

A structured interview is where interviewers ask pre-written questions to candidates in a standardised way, following an interview schedule. As far as possible the interviewer asks the same questions in the same order and the same way to all candidates.

(An exception to this is filter questions in which case the interviewer may skip sub-questions if a negative response is provided).

Answers to structured interviews are usually closed, or pre-coded, and the interviewer ticks the appropriate box according to the respondents’ answers. However some structured interviews may be open ended in which case the interviewer writes in the answers for the respondent.

Social surveys are the main context in which researchers will conduct structured interviews.

This post covers:

- the advantages of structured interviews

- the different contexts in which they take place (phone and computer assisted).

- the stages of conducting them: from knowing the schedule to leaving!

- their limitations.

Advantages of Structured Interviews

The main advantage of structured interviews is that they promote standardisation in both the processes of asking questions and recording answers.

This reduces bias and error in the asking of questions and makes it easier to process respondents’ answers.

The two main advantages of structured interviews are thus:

- Reducing error due to interviewer variability.

- Increasing the accuracy and ease of data processing.

Reducing error due to interviewer variability

Structured interviews help to reduce the amount of error in data collection because they are standardised.

Variability and thus error can occur in two ways:

- Intra-interviewer variability : occurs when an interviewer is not consistent with the way they ask the questions or record the answers.

- Inter-interviewer variability : when there are more than two interviewers who are not consistent with each other in the way they ask questions or record answers.

These two sources of variability can occur together and compound the the problem of reduced validity.

The common sources of error in survey research include:

- A poorly worded question.

- The way the question is asked by the interviewer.

- Misunderstanding on the part of the respondent being interviewed.

- Memory problems on the part of the respondent.

- The way the information is recorded by the interviewer.

- The way the information is processed: coding of answers or data entry.

Because the asking of questions and recording of answers are standardised, this means any variation in answers from respondents should be due to true or real variation in the respondents answers, rather than variation arising because of differences in the interview context.

Accuracy and Ease of Data Processing

Structured interviews consist of mainly closed, pre-coded questions or fixed choice questions.

With closed-questions the respondent is given a limited choice of possible answers and is asked to select which response or responses apply to them.

The interviewer then simply ticks the appropriate box.

This limit box ticking procedure limits the scope for interviewer bias to introduce error. There is no scope for the interviewer to omit or modify anything the respondent says because they are not writing down their answer.

Another advantage with pre-coded data gained from the structured interview is that it allows for ‘automatic’ data processing.

If answers had been written down or transcribed from a recording, a researcher would have to examine this qualitative data, sort and assign the various answers to categories.

For example if a survey had produced qualitative data on what respondents thought about Brexit, the researcher might categories the range of answers into ‘for Brexit’, ‘neutral’, and ‘against Brexit’.

This process of reducing more complex and varied data into fewer and simpler ‘higher level’ categories is known as coding data , or establishing a coding frame and is necessary for quantitive analysis to take place.

Coding (whether done before or after a structured interview takes place) introduces another source or potential error. Answers may be categorised incorrectly by the researchers. The researchers may categorise answers differently to how the respondents themselves would have categorised their answers.

There are two sources of error in recording data:

- Intra-rater-variability : where the person applying the coding is inconsistent in the way they apply the rules of assigning answers to categories.

- Inter-rater-variability : where two different raters apply the rules of assigning answers to categories differently.

If either or both of the above occur then variability in responses will be due to error rather than true variability in the responses.

The closed question survey/ interview avoids the above problem because respondents assign themselves to categories, simply by picking an option and the interviewer ticking a box.

There is very little opportunity with pre-coded interviews for interviewers or analysers to misinterpret or miss-assign respondents’ answers to the wrong categories.

Structured Interview Contexts

Structured interviews tend to be done when there is only one respondent. Group interviews are usually more qualitative because they dynamics of having two ore more respondents present mean answers tend to be more complex, and so tick-box answers are not usually sufficient to get valid data.

Besides the face to face interview, there are two particular contexts which are common with structured interviewing: telephone interviewing and computer assisted interviewing. (These are not mutually exclusive).

Telephone interviewing

Telephone interviews are very common with market research companies, and opinion polling companies such as YouGov. They are used less often by academic researchers but an exception to this was during the Covid-19 Pandemic when many studies which would usually rely on in-person interviews had to be carried out over the phone.

The advantages of telephone interviews

The advantages of telephone interviews compared to face to face interviews the advantages of telephone interviews are:

- Telephone interviews are cheaper and quicker to administer because there is no travel time or costs involved in accessing the respondents. The more dispersed the research sample is geographically the larger the advantage.

- Telephone interviews are easier to supervise than face to face interviews. You can have one supervisor in a room with several phone interviewers. Interviewers can be recorded and monitored, although care has to be taken with GDPR.

- Telephone interviews reduce bias due to the personal characteristics of the interviewers. It is much more difficult to tell what the class background or ethnicity or the interviewer is over the phone, for example.

The limitations of phone interviews

- People without phones cannot be part of the sample.

- Call screening with mobile phones has greatly reduced the response rate of phone surveys.

- Respondents with hearing impediments will find phone interviews more difficult.

- The length of a phone interview generally can’t be sustained over 20-25 minutes.

- There is a general belief that telephone interviews achieve lower response rates than face to face interviews.

- There is some evidence that phone interviews are less useful when dealing with sensitive topics but the data is not clear cut.

- There may. be validity problems because telephone interviews do not allow for observation. For example an interviewer cannot observe if a respondent is confused by a question.

- In cases where researchers need specific types of people, telephone interviews do not allow us to check if the correct types of people are actually those being interviewed.

Computer assisted Interviewing

With computer assisted interviewing interviews questions are pre-written and appear on the computer screen. Interviewers follow the instructions and read out questions in order and key in the respondents’ answers, either as open or closed responses.

There are two main types of Computer Assisted Interviewing:

- CAPI – Computer Assisted Personal Interviewing.

- CATI – Computer Assisted Telephone Interviewing.

Most telephone interviews today are Computer Assisted. There are several survey software packages that allow for the construction of effective surveys with analytics tools for data analysis.

They are less popular for personal interviews but have been growing in popularity.

CATI and CAPI are more common among commercial survey organisations such as IPSOS but are used less in academic research conducted by universities.

The advantages of computer assisted interviewing

CAPI are very useful for filter questions as the software can skip to the next question if the previous one isn’t relevant. This reduces the likelihood of the interviewer asking irrelevant questions or missing out questions.

They are also useful for prompt-questions as flash cards can be generated on the screen and shown to the respondents as required. This should mean respondents are more likely to see the flash-cards in the same way as there is no possibility for the researcher to arrange them in a different order for different respondents, as might be the case with physical flashcards.

Another advantage of computer assisted interviewing is automatic storage on the computer or cloud upload which means there is no need to scan paper interview sheets or enter the data manually at a later date.

Thus Computer Assisted Interviews should increase the level of standardisation and reduce the amount of variability error introduced by the interviewer.

The disadvantages of Computer Assisted Interviewing:

- They may create a sense of distance and disconnect between the interviewer and respondents.

- Miskeying may result in the interviewer entering incorrect data, and they are less likely to realise this than with paper interviews.

- Interviewers need to be comfortable with the technology.

Conducting Structured Interviews

The procedures involved with conducting an effective structure interview include:

- Knowing the interview schedule

- Gaining access

Introducing the research

- Establishing rapport

- Asking questions and recording answers

- Leaving the interview.

The processes above are specifically in relation to structured interviews, but will also apply to semi-structure interviews.

The interview schedule

An interview schedule is the list of questions in order, with relevant instructions about how the questions are to be asked. Before conducting an interview, the interviewer should know the interview schedule inside out.

Interviews can be stressful and pressure can cause interviewers to not follow standardised procedures. For example, interviewers may ask questions in the wrong order or miss questions out.

When several interviewers are involved in the research process it is especially important that all of them know the interview schedule to ensure questions are asked in a standardised way.

Gaining access

Interviews are the interface between the research and the respondents and are thus a crucial link in ensuring a good response rate. In order to gain access interviews need to:

- Be prepared to keep calling back with telephone interviews. Keep in mind the most likely times to get a response.

- Be self-assured and confident.

- Reassure people that you are not a salesperson, but doing research for a deeper purpose.

- Dress appropriately.

- Be prepared to be flexible with time: finding a time that fits the respondent if first contact isn’t convenient.

Respondents need to be provided with a rationale explaining the purposes of the research and why they are giving up their time to take part.

The introductory rationale may be written down or spoken. A written rationale may be sent out to prospective respondents in advance of the research taking place, as is the case with those selected to take part in the British Social Attitudes survey. A verbal rationale is employed with street-based market research, cold-calling telephone surveys and may also be reiterated during house to house surveys.

An effective introductory statement can be crucial in getting respondents to take part.

What should an introductory statement for social research include?

- Make clear the identity of the interviewer.

- Identify the agency which is conducting the research: for example a university or business.

- Include details of how the research is being funded.

- Indicate the broader purpose of the research in broad terms: what are the overall aims?

- Give an indication of the kind of data that will be collected.

- Make it clear that participation is voluntary.

- Make it clear that data will be anonymised and that the respondent will not be identified in any way, by data being analysed at an aggregate level.

- Provide reassurance about the confidentiality of information.

- Provide a respondent with the opportunity to ask questions.

Establishing rapport with structured interviews

Rapport is what makes the respondent feel as if they want to cooperate with the researcher and take part in the research. Without rapport being established respondents may either not agree to take part or terminate the interview half way through!

Rapport can be established through visual cues of friendliness such as positive body language, listening and good eye contact.

However with structured interviews, establishing rapport is a delicate balancing act as it is crucial for the interviewers be as objective as possible and not get too close to the respondents.

Rapport can be achieved by being friendly with the interviewee, although interviewers shouldn’t take this too far. Too much friendliness can result in the interview taking too long and the interviewee getting bored.

Too much rapport can also result in the respondent providing socially desirable answers.

Asking Questions and Recording Answers

With structured interviews it is important that researchers strive to ask the same questions in the same way to all respondents. They should ask questions as written in order to minimise error.

Experiments in question-wording suggest that even minor variations in wording can influence replies.

Interviewers may be tempted to deviate from the schedule because they feel awkward asking some questions to particular people, but training can help with this and make it more likely that standardisation is kept in place.

Where recording answers is concerned, bias is far less likely with pre-coded answers.

PROVIDING Clear instructions

Interviews need to follow clear instructions through the progress of the interview. This is important if an interview schedule includes filter questions.

Filter questions require the interviewer to ask questions of some respondents but not to others. Filler questions are usually indented on an interview schedule.

For example:

- Did you vote in the last general election…? YES / NO

1a (to be asked if respondent answered yes to Q1)

Which of the following political parties did you vote for? Conservatives/ Labour/ Lib Dems/ The Green Party/ Other.

The risk of not following instructions is that the respondent may be asked questions that are irrelevant to them, which may be irritating.

Question order

Researchers should stick to the question order on the survey.

Leapfrogging questions may result in questions skipped not being asked because the researcher could forget to go back to them.

Changing the question order may also lead to variability in replies because questions previously asked may affect how respondents answer questions later on in the survey.

Three specific examples demonstrate why question order matters:

People are less likely to respond that taxes should be lowered if they are asked questions about government spending beforehand.

In victim surveys if people are asked about their attitudes to crime first they are more likely to report that they have been a victim of crime in later questions.

One question in the 1988 British Crime Survey asked the following question:

‘Taking everything into account, would you say the police in this area do a good job or a poor job?

For all respondents this question appeared early on, but due to an admin error the question appeared twice in some surveys, and for those who answered the question twice:

- 66% gave the same response

- 22% gave a more positive response

- 12% gave a less positive response.

The fact that only two thirds of respondents gave the same response twice clearly indicates that the effect of question order can be huge.

One theory for the change is that the survey was about crime and as respondents thought more in-depth about crime as the interview progressed, 22% felt more favourable to the police and 13% less favourable, this would have varied with their own experiences.

Rules for ordering questions in social surveys

- Early questions should be clearly related to the topic of the research about which the respondent has already been informed. This is so the respondent immediately feels like the questions are relevant.

- Questions about age/ ethnicity/ gender etc. should not be asked at the beginning of the interview

- Sensitive questions should be left for later.

- With a longer questionnaire, questions should be grouped into sections to break up the interview.

- Within each subgroup general questions should precede specific ones.

- Opinions and attitudes questions should precede questions about behaviour and knowledge. Questions about the later are less likely to be influenced by question order.

- If a respondent has already answered a later question in the course of answering a previous one, that later question should still be asked.

Probing questions in structured interviews

Probing may be required in structured interviews when

- respondents do not understand the question and either ask for or it is clear that they need more information to provide an answer.

- The respondent does not provide a sufficient answer and needs to be probed for more information.

The problem with the interviewer asking additional probing questions is that they introduce researcher-led variability into the interview context.

Tactics for effective probing in structured interviews:

- Employ standardised probes . These work well when open ended answers are required. Examples of standardised probes include: ‘Could you say a little more about that?’ or ‘are there any other reasons why you think that?’.

- If a response does not allow for a pre-existing box to be ticked In a closed ended survey the interviewer could r epeat the available options .

- If the response requires a number rather than something like ‘often’ the researcher should just persist with asking the question . They shouldn’t try and second guess a number!

Prompting occurs when the interviewer suggests a possible answer to a question to the respondent. This is effectively what happens with a closed question survey or interview: the options are the prompts. The important thing is that the prompts are the same for all the respondents and asked in the same way.

During face to face interviews there may be times when it is better for researchers to use show cards (or flash cards) to display the answers rather than say them.

Three contexts in which flashcards are better:

- When there is a long list of possible answers. For example if asking respondents about which newspapers they read, it would be easier to show them a list rather than reading them out!

- With Likert Scales, ranked for 1-5 for example, it would be easier to have a showcard with 1-5 and the respondent can point to it, rather than reading out ‘1,2,3,4,5’.

- With some sensitive details such as income, respondents might feel more comfortable if they are shown income bands with letters attached, then they can say the letter. This allows the respondent to not state what their income is out loud.

Leaving the Interview

On leaving the interview thank the respondent for taking part.

Researchers should not engage in further communication about the purpose of the research at this point beyond the standard introductory statement. To do so means this respondent may divulge further information to other respondents yet to take part, possibly biassing their responses.

Problems with structured interviews

Four problems with structured interviews include:

- the characteristics of the interviewer interfering with the results.

- Response sets resulting in reduced validity (acquiescence and social desirability).

- The problem of lack of shared meaning.

- The feminist critique of the unequal power relationship between interviewer and respondent.

Interviewer characteristics

The characteristics of the interviewer such as their gender or ethnicity may affect the responses a respondent gives. For example, a respondent may be less likely to open up on sensitive issues with someone who is a different gender to them.

Response Sets

This is where respondents reply to a series of questions in a consistent way but one that is irrelevant to the concept being measured.

This is a particular problem when respondents are answering several Likert Scale questions in a row.

Two of the most prominent types of response set are ‘acquiescence’ and ‘social desirability bias’

Acquiescence

Acquiescence refers to a tendency of some respondents to consistently agree or disagree with a set of questions. They may do this because it is quicker for them to get through the interview. This is known as satisficing.

Satisficing is where respondents reduce the amount of effort required to answer a question. They settle for an answer that is satisfactory rather than making the effort to generate the most accurate answer.

Examples of satisficing include:

- Agreeing with yes statements or ‘yeasaying’.

- Opting for middle point answers on scales.

- Not considering the full-range of answers in a range of closed questions, for example picking the first or last answers.

The opposite of satisficing is optimising. Optimising is where respondents expend effort to arrive at the best and most appropriate answer to a question.

It is possible to weed out respondents who do this by ensuring there is a mix of positive and negative sentiment in a batch of Likert questions.

For example you may have a batch of three questions designed to measure attitudes towards Rishi Sunak’s performance as Primeminister.

If you have two scales where ‘5’ is positive and one where 5 is Negative, for example:

- Rishi Sunak is an effective leader 1.2.3.4.5

- Rishi Sunak has managed the economy well 1.2.3.4.5

- Rishi Sunak is NOT to be trusted 1.2.3.4.5

If someone is acquiescing without thinking about their answers, they are likely to circle all 5s, which wouldn’t make sense. Hence we could disregard this response and maybe even the entire survey from this individual.

Social desirability bias

Socially desirable behaviours and attitudes tend to be over-reported. This can especially be the case for sensitive questions.

Strategies for reducing social interviews bias

- Use self-completion forms rather than interviewers.

- Soften the question for example ‘even the calmest of car drivers sometimes lose their temper when driving, has this ever happened to you?

The problem of meaning

Structured surveys and interviews assume that respondents share the same meanings for terms as the interviewers.

However, from an interpretivist perspective interviewer and respondent may not share the same meanings. Respondents may be ticking boxes but mean different things to what the interviewer thinks they mean.

The issue of meaning is side-stepped in structured interviews.

The feminist critique of structured interviews

The structure of the interview epitomises the asymmetrical relationship between researcher and respondent. This is a critique made of all quantitative research.

The researcher extracts information from the respondent and gives little or nothing in return.

Interviewers are even advised not to get too familiar with respondents as giving away too much information may bias the results.

Interviewers should refrain from expressing their opinions, presenting any personal information and engaging in off-topic chatter. All of this is very impersonal.

This means that structured interviews are probably not appropriate for very sensitive topics that involve a more personal touch. For example with domestic violence, unstructured interviews which aim to explore the nature of violence have revealed higher levels of violence than structured interviews such as the Crime Survey of England and Wales.

Sources and signposting

Structured interviews are relevant to the social research methods module within A-level sociology.

This post was adapted from Bryman, A (2016) Social Research Methods.

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Discover more from ReviseSociology

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 15 September 2022

Interviews in the social sciences

- Eleanor Knott ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9131-3939 1 ,

- Aliya Hamid Rao ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0674-4206 1 ,

- Kate Summers ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9964-0259 1 &

- Chana Teeger ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5046-8280 1

Nature Reviews Methods Primers volume 2 , Article number: 73 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

708k Accesses

49 Citations

42 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Interdisciplinary studies

In-depth interviews are a versatile form of qualitative data collection used by researchers across the social sciences. They allow individuals to explain, in their own words, how they understand and interpret the world around them. Interviews represent a deceptively familiar social encounter in which people interact by asking and answering questions. They are, however, a very particular type of conversation, guided by the researcher and used for specific ends. This dynamic introduces a range of methodological, analytical and ethical challenges, for novice researchers in particular. In this Primer, we focus on the stages and challenges of designing and conducting an interview project and analysing data from it, as well as strategies to overcome such challenges.

Similar content being viewed by others

The fundamental importance of method to theory

How ‘going online’ mediates the challenges of policy elite interviews

Participatory action research

Introduction.

In-depth interviews are a qualitative research method that follow a deceptively familiar logic of human interaction: they are conversations where people talk with each other, interact and pose and answer questions 1 . An interview is a specific type of interaction in which — usually and predominantly — a researcher asks questions about someone’s life experience, opinions, dreams, fears and hopes and the interview participant answers the questions 1 .

Interviews will often be used as a standalone method or combined with other qualitative methods, such as focus groups or ethnography, or quantitative methods, such as surveys or experiments. Although interviewing is a frequently used method, it should not be viewed as an easy default for qualitative researchers 2 . Interviews are also not suited to answering all qualitative research questions, but instead have specific strengths that should guide whether or not they are deployed in a research project. Whereas ethnography might be better suited to trying to observe what people do, interviews provide a space for extended conversations that allow the researcher insights into how people think and what they believe. Quantitative surveys also give these kinds of insights, but they use pre-determined questions and scales, privileging breadth over depth and often overlooking harder-to-reach participants.

In-depth interviews can take many different shapes and forms, often with more than one participant or researcher. For example, interviews might be highly structured (using an almost survey-like interview guide), entirely unstructured (taking a narrative and free-flowing approach) or semi-structured (using a topic guide ). Researchers might combine these approaches within a single project depending on the purpose of the interview and the characteristics of the participant. Whatever form the interview takes, researchers should be mindful of the dynamics between interviewer and participant and factor these in at all stages of the project.

In this Primer, we focus on the most common type of interview: one researcher taking a semi-structured approach to interviewing one participant using a topic guide. Focusing on how to plan research using interviews, we discuss the necessary stages of data collection. We also discuss the stages and thought-process behind analysing interview material to ensure that the richness and interpretability of interview material is maintained and communicated to readers. The Primer also tracks innovations in interview methods and discusses the developments we expect over the next 5–10 years.

We wrote this Primer as researchers from sociology, social policy and political science. We note our disciplinary background because we acknowledge that there are disciplinary differences in how interviews are approached and understood as a method.

Experimentation

Here we address research design considerations and data collection issues focusing on topic guide construction and other pragmatics of the interview. We also explore issues of ethics and reflexivity that are crucial throughout the research project.

Research design

Participant selection.

Participants can be selected and recruited in various ways for in-depth interview studies. The researcher must first decide what defines the people or social groups being studied. Often, this means moving from an abstract theoretical research question to a more precise empirical one. For example, the researcher might be interested in how people talk about race in contexts of diversity. Empirical settings in which this issue could be studied could include schools, workplaces or adoption agencies. The best research designs should clearly explain why the particular setting was chosen. Often there are both intrinsic and extrinsic reasons for choosing to study a particular group of people at a specific time and place 3 . Intrinsic motivations relate to the fact that the research is focused on an important specific social phenomenon that has been understudied. Extrinsic motivations speak to the broader theoretical research questions and explain why the case at hand is a good one through which to address them empirically.

Next, the researcher needs to decide which types of people they would like to interview. This decision amounts to delineating the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study. The criteria might be based on demographic variables, like race or gender, but they may also be context-specific, for example, years of experience in an organization. These should be decided based on the research goals. Researchers should be clear about what characteristics would make an individual a candidate for inclusion in the study (and what would exclude them).

The next step is to identify and recruit the study’s sample . Usually, many more people fit the inclusion criteria than can be interviewed. In cases where lists of potential participants are available, the researcher might want to employ stratified sampling , dividing the list by characteristics of interest before sampling.

When there are no lists, researchers will often employ purposive sampling . Many researchers consider purposive sampling the most useful mode for interview-based research since the number of interviews to be conducted is too small to aim to be statistically representative 4 . Instead, the aim is not breadth, via representativeness, but depth via rich insights about a set of participants. In addition to purposive sampling, researchers often use snowball sampling . Both purposive and snowball sampling can be combined with quota sampling . All three types of sampling aim to ensure a variety of perspectives within the confines of a research project. A goal for in-depth interview studies can be to sample for range, being mindful of recruiting a diversity of participants fitting the inclusion criteria.

Study design

The total number of interviews depends on many factors, including the population studied, whether comparisons are to be made and the duration of interviews. Studies that rely on quota sampling where explicit comparisons are made between groups will require a larger number of interviews than studies focused on one group only. Studies where participants are interviewed over several hours, days or even repeatedly across years will tend to have fewer participants than those that entail a one-off engagement.

Researchers often stop interviewing when new interviews confirm findings from earlier interviews with no new or surprising insights (saturation) 4 , 5 , 6 . As a criterion for research design, saturation assumes that data collection and analysis are happening in tandem and that researchers will stop collecting new data once there is no new information emerging from the interviews. This is not always possible. Researchers rarely have time for systematic data analysis during data collection and they often need to specify their sample in funding proposals prior to data collection. As a result, researchers often draw on existing reports of saturation to estimate a sample size prior to data collection. These suggest between 12 and 20 interviews per category of participant (although researchers have reported saturation with samples that are both smaller and larger than this) 7 , 8 , 9 . The idea of saturation has been critiqued by many qualitative researchers because it assumes that meaning inheres in the data, waiting to be discovered — and confirmed — once saturation has been reached 7 . In-depth interview data are often multivalent and can give rise to different interpretations. The important consideration is, therefore, not merely how many participants are interviewed, but whether one’s research design allows for collecting rich and textured data that provide insight into participants’ understandings, accounts, perceptions and interpretations.

Sometimes, researchers will conduct interviews with more than one participant at a time. Researchers should consider the benefits and shortcomings of such an approach. Joint interviews may, for example, give researchers insight into how caregivers agree or debate childrearing decisions. At the same time, they may be less adaptive to exploring aspects of caregiving that participants may not wish to disclose to each other. In other cases, there may be more than one person interviewing each participant, such as when an interpreter is used, and so it is important to consider during the research design phase how this might shape the dynamics of the interview.

Data collection

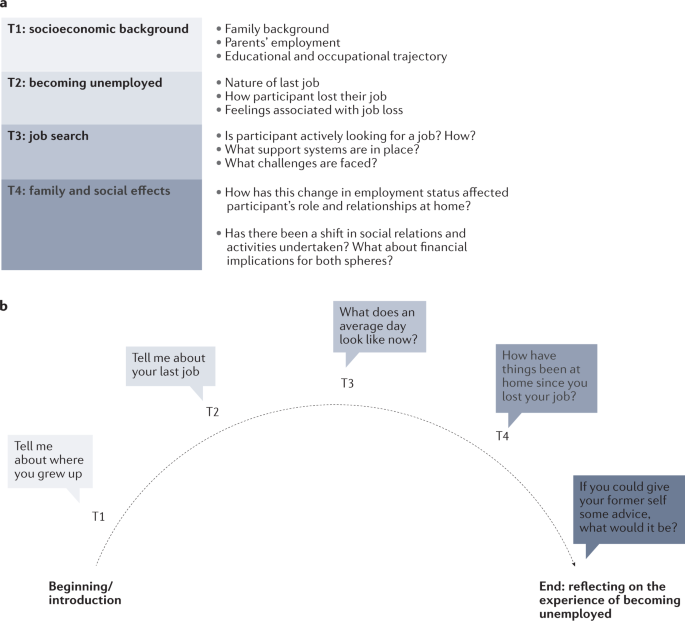

Semi-structured interviews are typically organized around a topic guide comprised of an ordered set of broad topics (usually 3–5). Each topic includes a set of questions that form the basis of the discussion between the researcher and participant (Fig. 1 ). These topics are organized around key concepts that the researcher has identified (for example, through a close study of prior research, or perhaps through piloting a small, exploratory study) 5 .

a | Elaborated topics the researcher wants to cover in the interview and example questions. b | An example topic arc. Using such an arc, one can think flexibly about the order of topics. Considering the main question for each topic will help to determine the best order for the topics. After conducting some interviews, the researcher can move topics around if a different order seems to make sense.

Topic guide

One common way to structure a topic guide is to start with relatively easy, open-ended questions (Table 1 ). Opening questions should be related to the research topic but broad and easy to answer, so that they help to ease the participant into conversation.

After these broad, opening questions, the topic guide may move into topics that speak more directly to the overarching research question. The interview questions will be accompanied by probes designed to elicit concrete details and examples from the participant (see Table 1 ).

Abstract questions are often easier for participants to answer once they have been asked more concrete questions. In our experience, for example, questions about feelings can be difficult for some participants to answer, but when following probes concerning factual experiences these questions can become less challenging. After the main themes of the topic guide have been covered, the topic guide can move onto closing questions. At this stage, participants often repeat something they have said before, although they may sometimes introduce a new topic.

Interviews are especially well suited to gaining a deeper insight into people’s experiences. Getting these insights largely depends on the participants’ willingness to talk to the researcher. We recommend designing open-ended questions that are more likely to elicit an elaborated response and extended reflection from participants rather than questions that can be answered with yes or no.

Questions should avoid foreclosing the possibility that the participant might disagree with the premise of the question. Take for example the question: “Do you support the new family-friendly policies?” This question minimizes the possibility of the participant disagreeing with the premise of this question, which assumes that the policies are ‘family-friendly’ and asks for a yes or no answer. Instead, asking more broadly how a participant feels about the specific policy being described as ‘family-friendly’ (for example, a work-from-home policy) allows them to express agreement, disagreement or impartiality and, crucially, to explain their reasoning 10 .

For an uninterrupted interview that will last between 90 and 120 minutes, the topic guide should be one to two single-spaced pages with questions and probes. Ideally, the researcher will memorize the topic guide before embarking on the first interview. It is fine to carry a printed-out copy of the topic guide but memorizing the topic guide ahead of the interviews can often make the interviewer feel well prepared in guiding the participant through the interview process.

Although the topic guide helps the researcher stay on track with the broad areas they want to cover, there is no need for the researcher to feel tied down by the topic guide. For instance, if a participant brings up a theme that the researcher intended to discuss later or a point the researcher had not anticipated, the researcher may well decide to follow the lead of the participant. The researcher’s role extends beyond simply stating the questions; it entails listening and responding, making split-second decisions about what line of inquiry to pursue and allowing the interview to proceed in unexpected directions.

Optimizing the interview

The ideal place for an interview will depend on the study and what is feasible for participants. Generally, a place where the participant and researcher can both feel relaxed, where the interview can be uninterrupted and where noise or other distractions are limited is ideal. But this may not always be possible and so the researcher needs to be prepared to adapt their plans within what is feasible (and desirable for participants).

Another key tool for the interview is a recording device (assuming that permission for recording has been given). Recording can be important to capture what the participant says verbatim. Additionally, it can allow the researcher to focus on determining what probes and follow-up questions they want to pursue rather than focusing on taking notes. Sometimes, however, a participant may not allow the researcher to record, or the recording may fail. If the interview is not recorded we suggest that the researcher takes brief notes during the interview, if feasible, and then thoroughly make notes immediately after the interview and try to remember the participant’s facial expressions, gestures and tone of voice. Not having a recording of an interview need not limit the researcher from getting analytical value from it.

As soon as possible after each interview, we recommend that the researcher write a one-page interview memo comprising three key sections. The first section should identify two to three important moments from the interview. What constitutes important is up to the researcher’s discretion 9 . The researcher should note down what happened in these moments, including the participant’s facial expressions, gestures, tone of voice and maybe even the sensory details of their surroundings. This exercise is about capturing ethnographic detail from the interview. The second part of the interview memo is the analytical section with notes on how the interview fits in with previous interviews, for example, where the participant’s responses concur or diverge from other responses. The third part consists of a methodological section where the researcher notes their perception of their relationship with the participant. The interview memo allows the researcher to think critically about their positionality and practice reflexivity — key concepts for an ethical and transparent research practice in qualitative methodology 11 , 12 .

Ethics and reflexivity

All elements of an in-depth interview can raise ethical challenges and concerns. Good ethical practice in interview studies often means going beyond the ethical procedures mandated by institutions 13 . While discussions and requirements of ethics can differ across disciplines, here we focus on the most pertinent considerations for interviews across the research process for an interdisciplinary audience.

Ethical considerations prior to interview

Before conducting interviews, researchers should consider harm minimization, informed consent, anonymity and confidentiality, and reflexivity and positionality. It is important for the researcher to develop their own ethical sensitivities and sensibilities by gaining training in interview and qualitative methods, reading methodological and field-specific texts on interviews and ethics and discussing their research plans with colleagues.

Researchers should map the potential harm to consider how this can be minimized. Primarily, researchers should consider harm from the participants’ perspective (Box 1 ). But, it is also important to consider and plan for potential harm to the researcher, research assistants, gatekeepers, future researchers and members of the wider community 14 . Even the most banal of research topics can potentially pose some form of harm to the participant, researcher and others — and the level of harm is often highly context-dependent. For example, a research project on religion in society might have very different ethical considerations in a democratic versus authoritarian research context because of how openly or not such topics can be discussed and debated 15 .

The researcher should consider how they will obtain and record informed consent (for example, written or oral), based on what makes the most sense for their research project and context 16 . Some institutions might specify how informed consent should be gained. Regardless of how consent is obtained, the participant must be made aware of the form of consent, the intentions and procedures of the interview and potential forms of harm and benefit to the participant or community before the interview commences. Moreover, the participant must agree to be interviewed before the interview commences. If, in addition to interviews, the study contains an ethnographic component, it is worth reading around this topic (see, for example, Murphy and Dingwall 17 ). Informed consent must also be gained for how the interview will be recorded before the interview commences. These practices are important to ensure the participant is contributing on a voluntary basis. It is also important to remind participants that they can withdraw their consent at any time during the interview and for a specified period after the interview (to be decided with the participant). The researcher should indicate that participants can ask for anything shared to be off the record and/or not disseminated.

In terms of anonymity and confidentiality, it is standard practice when conducting interviews to agree not to use (or even collect) participants’ names and personal details that are not pertinent to the study. Anonymizing can often be the safer option for minimizing harm to participants as it is hard to foresee all the consequences of de-anonymizing, even if participants agree. Regardless of what a researcher decides, decisions around anonymity must be agreed with participants during the process of gaining informed consent and respected following the interview.

Although not all ethical challenges can be foreseen or planned for 18 , researchers should think carefully — before the interview — about power dynamics, participant vulnerability, emotional state and interactional dynamics between interviewer and participant, even when discussing low-risk topics. Researchers may then wish to plan for potential ethical issues, for example by preparing a list of relevant organizations to which participants can be signposted. A researcher interviewing a participant about debt, for instance, might prepare in advance a list of debt advice charities, organizations and helplines that could provide further support and advice. It is important to remember that the role of an interviewer is as a researcher rather than as a social worker or counsellor because researchers may not have relevant and requisite training in these other domains.

Box 1 Mapping potential forms of harm

Social: researchers should avoid causing any relational detriment to anyone in the course of interviews, for example, by sharing information with other participants or causing interview participants to be shunned or mistreated by their community as a result of participating.

Economic: researchers should avoid causing financial detriment to anyone, for example, by expecting them to pay for transport to be interviewed or to potentially lose their job as a result of participating.

Physical: researchers should minimize the risk of anyone being exposed to violence as a result of the research both from other individuals or from authorities, including police.

Psychological: researchers should minimize the risk of causing anyone trauma (or re-traumatization) or psychological anguish as a result of the research; this includes not only the participant but importantly the researcher themselves and anyone that might read or analyse the transcripts, should they contain triggering information.

Political: researchers should minimize the risk of anyone being exposed to political detriment as a result of the research, such as retribution.

Professional/reputational: researchers should minimize the potential for reputational damage to anyone connected to the research (this includes ensuring good research practices so that any researchers involved are not harmed reputationally by being involved with the research project).

The task here is not to map exhaustively the potential forms of harm that might pertain to a particular research project (that is the researcher’s job and they should have the expertise most suited to mapping such potential harms relative to the specific project) but to demonstrate the breadth of potential forms of harm.

Ethical considerations post-interview

Researchers should consider how interview data are stored, analysed and disseminated. If participants have been offered anonymity and confidentiality, data should be stored in a way that does not compromise this. For example, researchers should consider removing names and any other unnecessary personal details from interview transcripts, password-protecting and encrypting files and using pseudonyms to label and store all interview data. It is also important to address where interview data are taken (for example, across borders in particular where interview data might be of interest to local authorities) and how this might affect the storage of interview data.

Examining how the researcher will represent participants is a paramount ethical consideration both in the planning stages of the interview study and after it has been conducted. Dissemination strategies also need to consider questions of anonymity and representation. In small communities, even if participants are given pseudonyms, it might be obvious who is being described. Anonymizing not only the names of those participating but also the research context is therefore a standard practice 19 . With particularly sensitive data or insights about the participant, it is worth considering describing participants in a more abstract way rather than as specific individuals. These practices are important both for protecting participants’ anonymity but can also affect the ability of the researcher and others to return ethically to the research context and similar contexts 20 .

Reflexivity and positionality

Reflexivity and positionality mean considering the researcher’s role and assumptions in knowledge production 13 . A key part of reflexivity is considering the power relations between the researcher and participant within the interview setting, as well as how researchers might be perceived by participants. Further, researchers need to consider how their own identities shape the kind of knowledge and assumptions they bring to the interview, including how they approach and ask questions and their analysis of interviews (Box 2 ). Reflexivity is a necessary part of developing ethical sensibility as a researcher by adapting and reflecting on how one engages with participants. Participants should not feel judged, for example, when they share information that researchers might disagree with or find objectionable. How researchers deal with uncomfortable moments or information shared by participants is at their discretion, but they should consider how they will react both ahead of time and in the moment.

Researchers can develop their reflexivity by considering how they themselves would feel being asked these interview questions or represented in this way, and then adapting their practice accordingly. There might be situations where these questions are not appropriate in that they unduly centre the researchers’ experiences and worldview. Nevertheless, these prompts can provide a useful starting point for those beginning their reflexive journey and developing an ethical sensibility.

Reflexivity and ethical sensitivities require active reflection throughout the research process. For example, researchers should take care in interview memos and their notes to consider their assumptions, potential preconceptions, worldviews and own identities prior to and after interviews (Box 2 ). Checking in with assumptions can be a way of making sure that researchers are paying close attention to their own theoretical and analytical biases and revising them in accordance with what they learn through the interviews. Researchers should return to these notes (especially when analysing interview material), to try to unpack their own effects on the research process as well as how participants positioned and engaged with them.

Box 2 Aspects to reflect on reflexively

For reflexive engagement, and understanding the power relations being co-constructed and (re)produced in interviews, it is necessary to reflect, at a minimum, on the following.

Ethnicity, race and nationality, such as how does privilege stemming from race or nationality operate between the researcher, the participant and research context (for example, a researcher from a majority community may be interviewing a member of a minority community)

Gender and sexuality, see above on ethnicity, race and nationality

Social class, and in particular the issue of middle-class bias among researchers when formulating research and interview questions

Economic security/precarity, see above on social class and thinking about the researcher’s relative privilege and the source of biases that stem from this

Educational experiences and privileges, see above

Disciplinary biases, such as how the researcher’s discipline/subfield usually approaches these questions, possibly normalizing certain assumptions that might be contested by participants and in the research context

Political and social values

Lived experiences and other dimensions of ourselves that affect and construct our identity as researchers

In this section, we discuss the next stage of an interview study, namely, analysing the interview data. Data analysis may begin while more data are being collected. Doing so allows early findings to inform the focus of further data collection, as part of an iterative process across the research project. Here, the researcher is ultimately working towards achieving coherence between the data collected and the findings produced to answer successfully the research question(s) they have set.

The two most common methods used to analyse interview material across the social sciences are thematic analysis 21 and discourse analysis 22 . Thematic analysis is a particularly useful and accessible method for those starting out in analysis of qualitative data and interview material as a method of coding data to develop and interpret themes in the data 21 . Discourse analysis is more specialized and focuses on the role of discourse in society by paying close attention to the explicit, implicit and taken-for-granted dimensions of language and power 22 , 23 . Although thematic and discourse analysis are often discussed as separate techniques, in practice researchers might flexibly combine these approaches depending on the object of analysis. For example, those intending to use discourse analysis might first conduct thematic analysis as a way to organize and systematize the data. The object and intention of analysis might differ (for example, developing themes or interrogating language), but the questions facing the researcher (such as whether to take an inductive or deductive approach to analysis) are similar.

Preparing data

Data preparation is an important step in the data analysis process. The researcher should first determine what comprises the corpus of material and in what form it will it be analysed. The former refers to whether, for example, alongside the interviews themselves, analytic memos or observational notes that may have been taken during data collection will also be directly analysed. The latter refers to decisions about how the verbal/audio interview data will be transformed into a written form, making it suitable for processes of data analysis. Typically, interview audio recordings are transcribed to produce a written transcript. It is important to note that the process of transcription is one of transformation. The verbal interview data are transformed into a written transcript through a series of decisions that the researcher must make. The researcher should consider the effect of mishearing what has been said or how choosing to punctuate a sentence in a particular way will affect the final analysis.

Box 3 shows an example transcript excerpt from an interview with a teacher conducted by Teeger as part of her study of history education in post-apartheid South Africa 24 (Box 3 ). Seeing both the questions and the responses means that the reader can contextualize what the participant (Ms Mokoena) has said. Throughout the transcript the researcher has used square brackets, for example to indicate a pause in speech, when Ms Mokoena says “it’s [pause] it’s a difficult topic”. The transcription choice made here means that we see that Ms Mokoena has taken time to pause, perhaps to search for the right words, or perhaps because she has a slight apprehension. Square brackets are also included as an overt act of communication to the reader. When Ms Mokoena says “ja”, the English translation (“yes”) of the word in Afrikaans is placed in square brackets to ensure that the reader can follow the meaning of the speech.

Decisions about what to include when transcribing will be hugely important for the direction and possibilities of analysis. Researchers should decide what they want to capture in the transcript, based on their analytic focus. From a (post)positivist perspective 25 , the researcher may be interested in the manifest content of the interview (such as what is said, not how it is said). In that case, they may choose to transcribe intelligent verbatim . From a constructivist perspective 25 , researchers may choose to record more aspects of speech (including, for example, pauses, repetitions, false starts, talking over one another) so that these features can be analysed. Those working from this perspective argue that to recognize the interactional nature of the interview setting adequately and to avoid misinterpretations, features of interaction (pauses, overlaps between speakers and so on) should be preserved in transcription and therefore in the analysis 10 . Readers interested in learning more should consult Potter and Hepburn’s summary of how to present interaction through transcription of interview data 26 .

The process of analysing semi-structured interviews might be thought of as a generative rather than an extractive enterprise. Findings do not already exist within the interview data to be discovered. Rather, researchers create something new when analysing the data by applying their analytic lens or approach to the transcripts. At a high level, there are options as to what researchers might want to glean from their interview data. They might be interested in themes, whereby they identify patterns of meaning across the dataset 21 . Alternatively, they may focus on discourse(s), looking to identify how language is used to construct meanings and therefore how language reinforces or produces aspects of the social world 27 . Alternatively, they might look at the data to understand narrative or biographical elements 28 .

A further overarching decision to make is the extent to which researchers bring predetermined framings or understandings to bear on their data, or instead begin from the data themselves to generate an analysis. One way of articulating this is the extent to which researchers take a deductive approach or an inductive approach to analysis. One example of a truly inductive approach is grounded theory, whereby the aim of the analysis is to build new theory, beginning with one’s data 6 , 29 . In practice, researchers using thematic and discourse analysis often combine deductive and inductive logics and describe their process instead as iterative (referred to also as an abductive approach ) 30 , 31 . For example, researchers may decide that they will apply a given theoretical framing, or begin with an initial analytic framework, but then refine or develop these once they begin the process of analysis.

Box 3 Excerpt of interview transcript (from Teeger 24 )

Interviewer : Maybe you could just start by talking about what it’s like to teach apartheid history.

Ms Mokoena : It’s a bit challenging. You’ve got to accommodate all the kids in the class. You’ve got to be sensitive to all the racial differences. You want to emphasize the wrongs that were done in the past but you also want to, you know, not to make kids feel like it’s their fault. So you want to use the wrongs of the past to try and unite the kids …

Interviewer : So what kind of things do you do?

Ms Mokoena : Well I normally highlight the fact that people that were struggling were not just the blacks, it was all the races. And I give examples of the people … from all walks of life, all races, and highlight how they suffered as well as a result of apartheid, particularly the whites… . What I noticed, particularly my first year of teaching apartheid, I noticed that the black kids made the others feel responsible for what happened… . I had a lot of fights…. A lot of kids started hating each other because, you know, the others are white and the others were black. And they started saying, “My mother is a domestic worker because she was never allowed an opportunity to get good education.” …

Interviewer : I didn’t see any of that now when I was observing.

Ms Mokoena : … Like I was saying I think that because of the re-emphasis of the fact that, look, everybody did suffer one way or the other, they sort of got to see that it was everybody’s struggle … . They should now get to understand that that’s why we’re called a Rainbow Nation. Not everybody agreed with apartheid and not everybody suffered. Even all the blacks, not all blacks got to feel what the others felt . So ja [yes], it’s [pause] it’s a difficult topic, ja . But I think if you get the kids to understand why we’re teaching apartheid in the first place and you show the involvement of all races in all the different sides , then I think you have managed to teach it properly. So I think because of my inexperience then — that was my first year of teaching history — so I think I — maybe I over-emphasized the suffering of the blacks versus the whites [emphasis added].

Reprinted with permission from ref. 24 , Sage Publications.

From data to codes

Coding data is a key building block shared across many approaches to data analysis. Coding is a way of organizing and describing data, but is also ultimately a way of transforming data to produce analytic insights. The basic practice of coding involves highlighting a segment of text (this may be a sentence, a clause or a longer excerpt) and assigning a label to it. The aim of the label is to communicate some sort of summary of what is in the highlighted piece of text. Coding is an iterative process, whereby researchers read and reread their transcripts, applying and refining their codes, until they have a coding frame (a set of codes) that is applied coherently across the dataset and that captures and communicates the key features of what is contained in the data as it relates to the researchers’ analytic focus.

What one codes for is entirely contingent on the focus of the research project and the choices the researcher makes about the approach to analysis. At first, one might apply descriptive codes, summarizing what is contained in the interviews. It is rarely desirable to stop at this point, however, because coding is a tool to move from describing the data to interpreting the data. Suppose the researcher is pursuing some version of thematic analysis. In that case, it might be that the objects of coding are aspects of reported action, emotions, opinions, norms, relationships, routines, agreement/disagreement and change over time. A discourse analysis might instead code for different types of speech acts, tropes, linguistic or rhetorical devices. Multiple types of code might be generated within the same research project. What is important is that researchers are aware of the choices they are making in terms of what they are coding for. Moreover, through the process of refinement, the aim is to produce a set of discrete codes — in which codes are conceptually distinct, as opposed to overlapping. By using the same codes across the dataset, the researcher can capture commonalities across the interviews. This process of refinement involves relabelling codes and reorganizing how and where they are applied in the dataset.

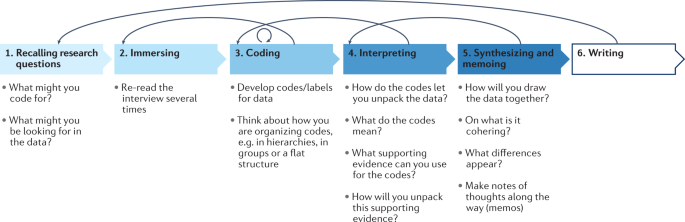

From coding to analysis and writing

Data analysis is also an iterative process in which researchers move closer to and further away from the data. As they move away from the data, they synthesize their findings, thus honing and articulating their analytic insights. As they move closer to the data, they ground these insights in what is contained in the interviews. The link should not be broken between the data themselves and higher-order conceptual insights or claims being made. Researchers must be able to show evidence for their claims in the data. Figure 2 summarizes this iterative process and suggests the sorts of activities involved at each stage more concretely.

As well as going through steps 1 to 6 in order, the researcher will also go backwards and forwards between stages. Some stages will themselves be a forwards and backwards processing of coding and refining when working across different interview transcripts.

At the stage of synthesizing, there are some common quandaries. When dealing with a dataset consisting of multiple interviews, there will be salient and minority statements across different participants, or consensus or dissent on topics of interest to the researcher. A strength of qualitative interviews is that we can build in these nuances and variations across our data as opposed to aggregating them away. When exploring and reporting data, researchers should be asking how different findings are patterned and which interviews contain which codes, themes or tropes. Researchers should think about how these variations fit within the longer flow of individual interviews and what these variations tell them about the nature of their substantive research interests.

A further consideration is how to approach analysis within and across interview data. Researchers may look at one individual code, to examine the forms it takes across different participants and what they might be able to summarize about this code in the round. Alternatively, they might look at how a code or set of codes pattern across the account of one participant, to understand the code(s) in a more contextualized way. Further analysis might be done according to different sampling characteristics, where researchers group together interviews based on certain demographic characteristics and explore these together.

When it comes to writing up and presenting interview data, key considerations tend to rest on what is often termed transparency. When presenting the findings of an interview-based study, the reader should be able to understand and trace what the stated findings are based upon. This process typically involves describing the analytic process, how key decisions were made and presenting direct excerpts from the data. It is important to account for how the interview was set up and to consider the active part that the researcher has played in generating the data 32 . Quotes from interviews should not be thought of as merely embellishing or adding interest to a final research output. Rather, quotes serve the important function of connecting the reader directly to the underlying data. Quotes, therefore, should be chosen because they provide the reader with the most apt insight into what is being discussed. It is good practice to report not just on what participants said, but also on the questions that were asked to elicit the responses.

Researchers have increasingly used specialist qualitative data analysis software to organize and analyse their interview data, such as NVivo or ATLAS.ti. It is important to remember that such software is a tool for, rather than an approach or technique of, analysis. That said, software also creates a wide range of possibilities in terms of what can be done with the data. As researchers, we should reflect on how the range of possibilities of a given software package might be shaping our analytical choices and whether these are choices that we do indeed want to make.

Applications

This section reviews how and why in-depth interviews have been used by researchers studying gender, education and inequality, nationalism and ethnicity and the welfare state. Although interviews can be employed as a method of data collection in just about any social science topic, the applications below speak directly to the authors’ expertise and cutting-edge areas of research.

When it comes to the broad study of gender, in-depth interviews have been invaluable in shaping our understanding of how gender functions in everyday life. In a study of the US hedge fund industry (an industry dominated by white men), Tobias Neely was interested in understanding the factors that enable white men to prosper in the industry 33 . The study comprised interviews with 45 hedge fund workers and oversampled women of all races and men of colour to capture a range of experiences and beliefs. Tobias Neely found that practices of hiring, grooming and seeding are key to maintaining white men’s dominance in the industry. In terms of hiring, the interviews clarified that white men in charge typically preferred to hire people like themselves, usually from their extended networks. When women were hired, they were usually hired to less lucrative positions. In terms of grooming, Tobias Neely identifies how older and more senior men in the industry who have power and status will select one or several younger men as their protégés, to include in their own elite networks. Finally, in terms of her concept of seeding, Tobias Neely describes how older men who are hedge fund managers provide the seed money (often in the hundreds of millions of dollars) for a hedge fund to men, often their own sons (but not their daughters). These interviews provided an in-depth look into gendered and racialized mechanisms that allow white men to flourish in this industry.

Research by Rao draws on dozens of interviews with men and women who had lost their jobs, some of the participants’ spouses and follow-up interviews with about half the sample approximately 6 months after the initial interview 34 . Rao used interviews to understand the gendered experience and understanding of unemployment. Through these interviews, she found that the very process of losing their jobs meant different things for men and women. Women often saw job loss as being a personal indictment of their professional capabilities. The women interviewed often referenced how years of devaluation in the workplace coloured their interpretation of their job loss. Men, by contrast, were also saddened by their job loss, but they saw it as part and parcel of a weak economy rather than a personal failing. How these varied interpretations occurred was tied to men’s and women’s very different experiences in the workplace. Further, through her analysis of these interviews, Rao also showed how these gendered interpretations had implications for the kinds of jobs men and women sought to pursue after job loss. Whereas men remained tied to participating in full-time paid work, job loss appeared to be a catalyst pushing some of the women to re-evaluate their ties to the labour force.

In a study of workers in the tech industry, Hart used interviews to explain how individuals respond to unwanted and ambiguously sexual interactions 35 . Here, the researcher used interviews to allow participants to describe how these interactions made them feel and act and the logics of how they interpreted, classified and made sense of them 35 . Through her analysis of these interviews, Hart showed that participants engaged in a process she termed “trajectory guarding”, whereby they sought to monitor unwanted and ambiguously sexual interactions to avoid them from escalating. Yet, as Hart’s analysis proficiently demonstrates, these very strategies — which protect these workers sexually — also undermined their workplace advancement.

Drawing on interviews, these studies have helped us to understand better how gendered mechanisms, gendered interpretations and gendered interactions foster gender inequality when it comes to paid work. Methodologically, these studies illuminate the power of interviews to reveal important aspects of social life.

Nationalism and ethnicity

Traditionally, nationalism has been studied from a top-down perspective, through the lens of the state or using historical methods; in other words, in-depth interviews have not been a common way of collecting data to study nationalism. The methodological turn towards everyday nationalism has encouraged more scholars to go to the field and use interviews (and ethnography) to understand nationalism from the bottom up: how people talk about, give meaning, understand, navigate and contest their relation to nation, national identification and nationalism 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 . This turn has also addressed the gap left by those studying national and ethnic identification via quantitative methods, such as surveys.

Surveys can enumerate how individuals ascribe to categorical forms of identification 40 . However, interviews can question the usefulness of such categories and ask whether these categories are reflected, or resisted, by participants in terms of the meanings they give to identification 41 , 42 . Categories often pitch identification as a mutually exclusive choice; but identification might be more complex than such categories allow. For example, some might hybridize these categories or see themselves as moving between and across categories 43 . Hearing how people talk about themselves and their relation to nations, states and ethnicities, therefore, contributes substantially to the study of nationalism and national and ethnic forms of identification.

One particular approach to studying these topics, whether via everyday nationalism or alternatives, is that of using interviews to capture both articulations and narratives of identification, relations to nationalism and the boundaries people construct. For example, interviews can be used to gather self–other narratives by studying how individuals construct I–we–them boundaries 44 , including how participants talk about themselves, who participants include in their various ‘we’ groupings and which and how participants create ‘them’ groupings of others, inserting boundaries between ‘I/we’ and ‘them’. Overall, interviews hold great potential for listening to participants and understanding the nuances of identification and the construction of boundaries from their point of view.

Education and inequality

Scholars of social stratification have long noted that the school system often reproduces existing social inequalities. Carter explains that all schools have both material and sociocultural resources 45 . When children from different backgrounds attend schools with different material resources, their educational and occupational outcomes are likely to vary. Such material resources are relatively easy to measure. They are operationalized as teacher-to-student ratios, access to computers and textbooks and the physical infrastructure of classrooms and playgrounds.

Drawing on Bourdieusian theory 46 , Carter conceptualizes the sociocultural context as the norms, values and dispositions privileged within a social space 45 . Scholars have drawn on interviews with students and teachers (as well as ethnographic observations) to show how schools confer advantages on students from middle-class families, for example, by rewarding their help-seeking behaviours 47 . Focusing on race, researchers have revealed how schools can remain socioculturally white even as they enrol a racially diverse student population. In such contexts, for example, teachers often misrecognize the aesthetic choices made by students of colour, wrongly inferring that these students’ tastes in clothing and music reflect negative orientations to schooling 48 , 49 , 50 . These assessments can result in disparate forms of discipline and may ultimately shape educators’ assessments of students’ academic potential 51 .

Further, teachers and administrators tend to view the appropriate relationship between home and school in ways that resonate with white middle-class parents 52 . These parents are then able to advocate effectively for their children in ways that non-white parents are not 53 . In-depth interviews are particularly good at tapping into these understandings, revealing the mechanisms that confer privilege on certain groups of students and thereby reproduce inequality.

In addition, interviews can shed light on the unequal experiences that young people have within educational institutions, as the views of dominant groups are affirmed while those from disadvantaged backgrounds are delegitimized. For example, Teeger’s interviews with South African high schoolers showed how — because racially charged incidents are often framed as jokes in the broader school culture — Black students often feel compelled to ignore and keep silent about the racism they experience 54 . Interviews revealed that Black students who objected to these supposed jokes were coded by other students as serious or angry. In trying to avoid such labels, these students found themselves unable to challenge the racism they experienced. Interviews give us insight into these dynamics and help us see how young people understand and interpret the messages transmitted in schools — including those that speak to issues of inequality in their local school contexts as well as in society more broadly 24 , 55 .

The welfare state